Genesis of art criticism

The institution of Salons dates back to the seventeenth century. In the statutes of the Royal Academy of Painting, drawn up in 1663, the King ordered each academician to exhibit a painting at the Academy's annual general meeting in July. The first exhibition took place in 1665, but it was a private one, for the internal use of the Académie. The first public exhibition opened in 1667. Colbert visited it and decided that from then on it would be held every two years. But the periodicity of the first exhibitions, until the middle of the eighteenth century, remains irregular.

From 1725, the exhibition was held in the Salon carré of the Louvre, thus in a single room, which had the advantage of being not far from the Academy's premises. Because of its location, the Salon carré, the exhibition gradually took on the name Salon. From 1751, the Salon was held every two years, in odd-numbered years. It always begins at the end of summer, from August 25, St. Louis Day, and lasts a few weeks.

The exhibition is free of charge and attracts an ever-growing audience, which can be gauged from the sales figures of the Booklet printed by the Académie, a kind of catalog without pictures that gives the " explanation of the paintings " : on the walls where they are hung there is in fact no other indication than a number referring to the Booklet.

Between 1759 and 1781, the Académie sold first just over 7,000 and finally over 17,000 livrets. In the 1770s, the number of visitors would be over 20,000, which is enormous when you consider that Paris then had only 600,000 inhabitants.

The institution of the Salon gradually established itself in France it was unique in Europe. Provincial exhibitions were held in Toulouse, Marseille, Bordeaux, Lille and Montpellier. The former brotherhood of painters and sculptors in Paris, the Académie de Saint-Luc, tried to rival the Salons of the Royal Academy. But none of these exhibitions had the scope or impact of the biennial Salons of the Académie royale de peinture.

What is the purpose of the Salons ? Firstly, in the tradition of the princes' munificence, to work for the glory of France by publicly displaying the artistic and therefore political power of the kingdom. Secondly, through the works it exhibited, the Salon constituted the identity of a French School, supervised and endorsed by the Académie. This is why, within the Salon, the exhibition of works by newly-approved painters is of particular importance. Lastly, the Salon created a kind of public art market : admittedly, fashionable painters sometimes exhibited pre-paid commissions ; but many works were in search of buyers and thus benefited from exceptional publicity, relayed and amplified by the Salons' reports that flourished, either in the nascent press, or in the form of more or less anonymous fascicles or libelles.

Unique in Europe, this institution is part of what is known as the French cultural exception, an ambitious and voluntary policy initiated by Louis XIV, initially primarily to counter the cultural hegemony of Italy. The institution of the Royal Academies is an essential part of this mixed system, in which the State plays an essential role, but in which the private economic market is also involved. The Académie, on the other hand, retained a certain independence from the powers that be thanks to its recruitment method, the competitive examination, another French specialty, which aimed to foster the independence of artists and the emulation of creators.

What does the competition involve? In principle, it takes place in two stages. First, the artist submits a "morceau d'agrément" which, if accepted by the Académie, makes him or her an Academician, but a kind of outside member, with no right to take part in the voting or decision-making process. Two years later, he is expected to present a second painting, known as the reception painting, by which he becomes a full academician. These paintings are exhibited twice, first privately on the premises of the Académie, then to the public at the Salon that follows, i.e. sometimes one or two years after the painter's approval or reception.

In this way, the Salon plays a fundamental role in the Académie's artistic policy and, hence, in the aesthetic directions taken by the French school of painting : even if it does so only after the fact, and without any direct impact on its choices, the public comments on the Académie's decisions and exercises a kind of quality control.

The institution nevertheless experienced its first crisis in the mid-1770s, with painters accusing the jury that accepted or rejected paintings of tyranny. The official hierarchy of genres instituted by the Académie since the end of the seventeenth century placed historical, aristocratic and religious painting at the top, gave only second place at best to bourgeois genre painting, and placed decorative painting (landscapes, still lifes) and portraits at the very bottom of the scale. However, the economic reality of the art market was quite different: while princely commissions were becoming rare, and even the Church was slowing down its programs, demand from the wealthy bourgeoisie was exploding, to decorate private, intimate spaces, without ostentation or pomp. Light pastorals, genre paintings, landscapes and portraits soon occupied the bulk of the market. The shift from pageantry to decoration was widespread, regardless of the patron's social status. There was a growing divorce between the aesthetic demands of the Académie and the actual production of painters, as well as the taste and consumption of patrons and art lovers. Diderot, in this aesthetic revolution, adopts a middle position, not without ambiguities :

" It seems to me that the division of painting into genre painting and history painting makes sense, but I would like us to have consulted a little more about the nature of things in this division. We call genre painters indiscriminately those who deal only with flowers, fruit, animals, woods, forests, mountains, and those who borrow their scenes from common and domestic life; Tesniere, Wowermans, Greuze, Chardin, Loutherbourg, even Vernet are genre painters. However, I protest that Le Père qui fait la lecture à sa famille, Le Fils ingrat and Les Fiançailles by Greuze, that Vernet's Marines, which offer me all sorts of scenes of common and domestic life , are as much history paintings for me as Les Sept Sacrements by Poussin, La Famille de Darius by Le Brun, or the Susanne by Vanloo. " (Essais sur la peinture, " Paragraphe sur la composition " ; VERS 506 ; DPV XIV 398-399.) [1]

Diderot doesn't fundamentally question the hierarchy of genres and will castigate painters who trade, quite lucratively in fact, in decorative and light painting far removed from the classical demands for grandeur and the sublime. Instead, the philosopher argues for an adjustment of this hierarchy, for the extension of history painting to the peasant scenes of a Greuze, or the teeming seashores of a Vernet. For Diderot, the discriminating criterion for speaking of history painting becomes not the painting's external reference to a text, to a consecrated " history ", but the painting's internal composition as a " scene " : " scenes of common and domestic life ", " incidents and scenes " of a landscape constitute history paintings. /// of history because they are constituted as scenes and theatrically modeled.

But already it was no longer time for accommodations and compromises : a first revolt by painters resulted in the presentation of a brief to the secretary of the Académie in 1771 ; in 1775, Restout returned to the charge in 1789, contestation resumed in 1793, the Académie was suppressed.

Material aspect of a Salon

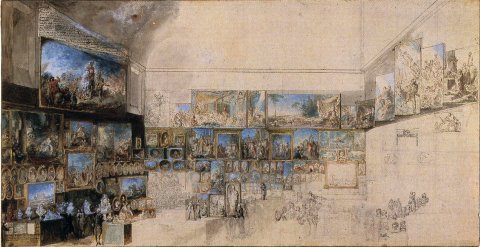

What does a Salon look like ? In the Louvre's square Salon, which is cramped to house an entire exhibition and hold so many visitors, paintings are hung from floor to ceiling. Prints are placed in the window embrasures. Sculptures are placed on tables in the center of the room. The hanging of paintings could give rise to diplomatic incidents, as each painter wanted the best place for his work. From 1761 to 1773, Chardin took on this role, known as the "upholsterer of the Salon". Diderot returns several times to the meaning Chardin gives to the paintings by arranging them in a certain order rather than another. This arrangement, which is neither chronological, logical nor hierarchical, constitutes the real, historical basis of the Salons device.

This is a far cry from contemporary museography. The idea is not to isolate a work on a large, brightly lit white wall, to focus the viewer's gaze and attention on an object, and within that object on a single point to which a commentary might point. The wall of the Salon carré is a multiple space from which it is up to the public to extract what will cause a sensation and hold the general attention. After all, the exhibition is a noisy one: people comment out loud, exclaim, get moved and get excited. The show is as much in the room as it is on the walls.

Diderot art critic

In the autumn of 1759, Diderot was commissioned by Baron Frédéric-Melchior Grimm, lover of Mme d'Épinay and familiar with the Philosophes, to report on the Salon.

Diderot's report will not, strictly speaking, be published. It was intended for a hand-copied review, La Correspondance littéraire, for which Grimm was the project manager. Not being printed, La Correspondance littéraire escaped censorship and thus dared to adopt an extremely free tone, style and ideas. In 1759, La Correspondance littéraire was still in its infancy, with just fifteen subscribers, crowned heads and wealthy, cultured aristocrats living outside France. Among them were Catherine II, Empress of Russia ; the Duke of Saxe-Gotha ; Louise-Ulrike, sister of Frederick of Prussia ; Louise-Ulrike's son, the future Gustave III of Sweden.

Since 1753, Grimm had been in charge of art criticism for the magazine. In 1757, Grimm devoted an article to Carle Vanloo's Sacrifice d'Iphigénie in which he dramatized his discussion with Diderot. In September 1759, Diderot promised Grimm that he would go to the Salon : " if he inspires me with something that can be of use to you, you will have it. Doesn't this enter into the plan of your leaves ? " Diderot will thus take over from Grimm, but always in the form of a collaboration, a dialogue with his friend : Diderot's Salons each time take the form of a letter addressed to Grimm, and Grimm inserts numerous comments for his readers.

La Correspondance littéraire henceforth became the protected space where Diderot could develop his work, sheltered from the storms of the Encyclopédie and the persecution he had received ten years earlier for publishing La Lettre sur les aveugles and Bijoux indiscrets. He writes a host of book reviews. But the Salons constitute his most consistent texts : from 1759 to 1767, they grow in scope each time, to the point that the one from 1767 has to be delivered separately, as a /// supplement. From 1769 onwards, and especially beyond, the Salons lose their importance. Diderot provides the Correspondance littéraire with something else: his novelistic texts and his first philosophical dialogues.

The writing of the Salons thus served as a relay between Diderot's first production, public and militant, and the mature work, in which Diderot immortalizes himself through an absolutely singular form of expression, a mode of reasoning : the Diderotian dialogue relies on a device that was constituted in the Salons. The writing of the Salons is the occasion for Diderot to have an intimate experience of the image : he doesn't just describe, in ever greater detail, the paintings. He reconstructs the very idea of composition, and manipulates, reforms and judges this idea upstream of the representation to which it has given rise: independently of its title, what is the real subject of the painting? has the painter represented it well? has he chosen and conceived it well? Judging a painting is therefore not only, not primarily, a technical judgment, an evaluation of the " faire " (quality and arrangement of colors, proportions of bodies, finishes of feet and hands, rendering of fabrics). The painter is first and foremost an intellectual, a philosopher who manipulates ideas. What counts, beyond " faire ", is " l'idéal ", i.e. everything in the representation that relates to the idea : the invention of the subject ; in the subject, therefore in the story it tells, the selection of a moment to paint ; and to represent this moment, the arrangement of characters, the choice of accessories, the overall tone of the scene.

What in painting is truly created is not the doing, the practical realization of the canvas, but the ideal, the invention of the scene. While Diderot, despite his increasingly advanced technical knowledge of Salon en Salon, remains necessarily alien to the faire, which refers exclusively to the pictorial support and the painter's craft, the ideal is the concern of all artists, all creators, whatever the field of application of representation : theater stage or printed book, painting or sculpture, dramatic or epic poetry...

Fundamentally, the idea in question here is the Platonic idea, whose reference is omnipresent in the Diderotian text : one thinks of the commentary on Fragonard's Corésus et Callirhoé in the Salon of 1765, a commentary entitled " L'Antre de Platon " ; or the preface to the Salon of 1767, with its long meditation on the φαντάσμα φαντάσματος Platonic [2]. And Diderot would repeat it over and over : from philosopher to literary artist, from literary artist to painter, poetic activity is the same, the manipulation of ideas, the making, the transformation of images proceeding from the same fundamentally iconic thought process.

The legacy of ekphrasis

The text/image pair : a decoy

Such an approach to painting baffles us today. The description of a painting often gives the impression of referring only to one referent : the actual canvas that the text describes. In recent years, Diderotian critics have made a major effort to elucidate the Salons from this perspective. Else-Marie Bukdahl /// In particular, we set out to identify the paintings to which Diderot refers and to locate them in current museums and collections [3]. This work has been accompanied by seemingly very different research, but in reality based on the same textual image / pictorial image pair: when the researcher focuses on Diderot's aesthetic ideas [4], on the influence of eighteenth-century schools and artistic currents on the writing of the Salons, he at least implicitly considers painting (albeit, more generally and subtly, the world of painters [5] and no longer any particular painting) as the sole referent of the text. As for semiotic analyses, which question the capacity of writing to account for painting, to translate an iconic space into a system of linguistic signs, while echoing the structuralist revolution in the field of Diderotian research, they do not fundamentally call into question the initial presupposition : it is in relation to the image that text is constructed [6].

Diderot's entire poetic effort would thus be oriented and informed by the textual translation of a pictorial space, perceived no longer as a collection of concrete paintings, nor even of aesthetic schools and ideas, but as a model of semiotic coherence heterogeneous to the scriptural model.

For lack of images, giving an account of the Salons

The point here, of course, is not to deny the existence in the Salons and for Diderot of this constitutive relationship. We do, however, hypothesize that this relationship is not primary. The Salons reviews that existed before Diderot's and then concurrently with his were peddled sheets or newspaper articles intended to be read in the absence of any drawings or engravings to illustrate them. The text was conceived as an autonomous object, independent and separate from the actual paintings, for which it served as a kind of substitute. From the point of view of text reception, then, the description of a painting does not immediately refer to a canvas that remains unknown to the reader. In the case of Diderot's Salons, this fact is even clearer and more indisputable: subscribers to the Correspondance littéraire resided abroad, and the reading of Diderot's text took the place for them of a visit to the Salon, substituted for this visit, constituted its supplement. The logic of the supplement, which Diderot deploys with extraordinary virtuosity in pieces like L'Antre de Platon or Promenade Vernet, derives its origin and even its necessity from this principial occultation of images, which is a constitutive reality of the Salons. Moreover, the absence of images will be a recurrent source of play, converting material lack into pleasure gain.

As the institution of the Salons is a specific feature of eighteenth-century France, as the rise of the press from which the reviews benefit is also a new historical fact at the time, as Diderot is atypical and innovative in everything he writes, everything points to cutting the Salons off from any pre-existing literary tradition, and to locating Diderot's borrowings only in the content of the aesthetic theories he incidentally manifests or develops, assuming readings he may or may not have made.

A rhetorical exercise

Yet this practice of describing absent paintings, the oratorical performance coming to substitute for the failing image, is an ancient one, inherited from the second ancient sophistry where, under the name of ἔκφρασις, it played a fundamental role. The ekphrasis is still, in classical culture and teaching, a familiar school exercise, /// associated with literary anthologies. There is thus a second referent to the description of painting, a referent that we'll call rhetorical, provided we consider rhetoric here not as an abstract grammar of language, but as a socially and historically integrated exercise of speech.

In other words, the description of a painting is not necessarily read to be confronted with the painting it describes, but rather, initially at least, to be integrated, subsumed into a general model of ekphrasis, a rhetorical model whose anthropological and semiological implications should be measured. The first gap, the first detour, that the reader encounters is therefore not that from image to text, as we might expect, but from the rhetorical model he knows to Diderot's very particular use of it. This détournement is not semiotic, but poetic, the problem not being to move from one semiotic system and medium to another (from image to text), but to transpose an ancient rhetorical model of the ἔκφρασις into a modern reality, where this practice is anachronistic [7].

The translation of the Greek word ekphrasis as " description " has led to many misunderstandings, as what we mean today by description has nothing to do with the ancient ekphrasis, which is not the textual imitation of an image.

The ekphrasis is an epidictic genre: it's about praising painting, celebrating through it the painter's excellence. The painter's "doing " doesn't come into play here, other than to extol its perfection without nuance. The painting being described and the text the painting represents - Homeric gesture, tragic episode, myth reported by Apollodorus - are transparent to each other describing the canvas and paraphrasing the literary text are one and the same.

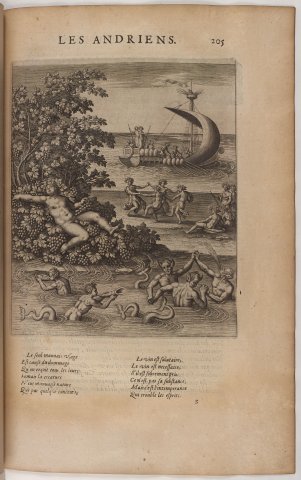

Andrian bacchanal

Let's take an example, in The Gallery of Paintings [8] by Flavius Philostratus [9], the ekphrasis of the Andrians. We know nothing of the ancient painting, even if it ever existed ; but the text is famous : it has given rise since the Renaissance to several Bacchanales des Andriens, by Titian and by Rubens, but also by Badalocchio, or Bertoja, whose only model was this ekphrasis. The ancient image, itself supported by a passage from Pausanias [10], thus gave rise to a text, which itself serves as a model for new images. This circulation is based on a transparency, an equivalence of representational media. The ekphrasis is not a commentary, a text alongside the image : it is a full-fledged image.

The value of the subject

Philostratus begins by establishing the subject :

" The Andrians intoxicated by the river of wine that flows through their island, such is the subject of this painting. It was Dionysus who for the Andrians brought forth from the bosom of the earth this veritable river, small in comparison to our rivers, divine and considerable, if you think it rolls streams of wine. He who draws from it may despise the Nile and the Ister, and say that they would be better, if, less important than they are, they were similar to this one. " [11]

The idea is this river of wine. But we don't know how the painting represents it, how this idea is technically implemented : color, position, layout, all that is ignored. What preoccupies Philostratus is the value of this river we must disregard its size, i.e. what is visible, and focus our minds on the quality of what flows in it, the wine, i.e. what is less accessible to the eye. Small, but precious : the ekphrasis substitutes for the reader, for the listener, the geometrality of things for their price : βελτίους ἂν ἐδόκουν, they would be better.

The speech, the song, the dream

This price, we'll now have to justify it, establish it in the order of discourse :

" And this, no doubt, is what the Andrians are singing, with their wives and children, all crowned with ivy and smilax [12], some dancing, others reclining on either bank. I can imagine hearing them: the Achélôos, they say, produces reeds the Pénée waters verdant valleys, flowers grow on the banks of the Pactole, but this river enriches men, makes them powerful in the public square, rich and obliging towards their friends, gives them beauty, and even if they are dwarfs, a height of four cubits for all these advantages, he who has drunk here can gather them together, adorn himself with them in imagination. They also sing, no doubt, that this river alone is not crossed by herds or horses, that, poured from the very hands of Dionysus, it is drunk in all its purity, flowing only for men. Imagine hearing this hymn, and also the stammering of a few drunken singers. "

Here again Philostratus does not describe painting in the modern sense of the word, but restores what must be the discourse of its protagonists : between the word of the painting and the word on the painting, the image is transparent. The performance of ekphrasis consists in identifying the image with a discourse, and in doing so within the image itself. The content of the painting is not visual, but a virtual speech : ᾄδουσιν οἶμαι ταῦτα, " this is undoubtedly what the Andrians sing " ; ϵἰκὸϛ δέ που κἀκεῖνα εἶναι τῆς ᾠδῆς, " I imagine hearing them " ; ᾄδουσι δέ που, " They sing too no doubt " ; ταυτὶ μὲν ἀκούειν ἡγοῦ, " Imagine yourself hearing ".

The Andrians' song, which thus substitutes for painting, qualifies the river ; it qualifies it first differentially, as a sign therefore, and then imaginatively : the river gives to imagine to the one who drinks it, as gives to imagine the ekphrasis itself. Philostratus' speech, the Andrians' song, is now superimposed on the dream of intoxicated men.

" what shows "

There's something like a discursive framing of the image, a leafing through of words that prepares its advent :

" Now this is what can be seen : the river, lying on a bed of grapes, spits out its flow ; its face is the color of pure wine, congested thyrses [13] have grown near it, like reeds in ordinary rivers. As he leaves the land and the banquets he witnesses, towards the mouth, the Tritons [14] come to meet him, and drawing wine from their /// conches, drink it or blow it into the air; some of them even get drunk and start dancing. Dionysus travels by sea to Andros and its feasts already the ship has entered the harbor, bringing the confused troop of satyrs, bacchantes, silenes ; it carries also and Laughter and Cômos [15], the gayest gods, the best companions of drunkenness, the most worthy to assist the god, in the mood of vintage. "

Τὰ μέντοι ὀρώμενα τῆς γραφῆς, what can be seen from the painting [16] is narrated here : the river cracks its flow, τὴν πηγὴν ἐκδιδοὺς the Tritons come to meet it, περὶ τὰς ἐκβολὰς ἀπαντῶντες ; Dionysus goes by sea to Andros, πλεῖ καὶ Διόνυσος ; so many action verbs in a text where the disposition and state of characters and things are sorely lacking. This is no elegant make-up, no roundabout way of describing : the geometrality of space is not the object of ekphrasis, is not an operative category in this world and for this performance.

Symbolic plenitude of the image

What counts here, what is given to see, is the meeting of the personified river-wine, the Tritons and Dionysus arriving on his ship. It doesn't matter how, in the space of the painting, this meeting is arranged both the ekphrasis and the painting celebrate this convergence, this meeting that closes a world without hollows or faults, where the saturation of wine is at the same time a symbolic repletion. " What is seen " is this replenishment, this conjunction, this saturation. The ekphrasis occupies the terrain of the visible, but occupies it in the order of language and on the exclusively symbolic plane.

There are, of course, all kinds of ekphraseis, organizing themselves according to the most diverse canvases. Some punctually mention an arrangement, a color, an expression : but it's always fugitive, adjacent. The Andrians' ekphrasis, composed in three stages (the value of the subject, the speeches it contains, the story it tells) constitutes a textbook case, a purification, which perhaps explains its pictorial fortune in the Renaissance : to paint an ekphrasis, i.e. an image from which the visual dimension has been removed, is a challenge and promises glory to whoever rises to the challenge.

The journalistic model

The first descriptions of paintings in the modern era are largely dependent on the ekphrasis model. Although he introduces a few technical notations, Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives of the Best Painters, still essentially describes paintings first in the form of praise, then as a narrative of the subject. Philostratus was also rediscovered in France, translated by Blaise de Vigenère, and illustrated from the second edition in 1614 [17], which is both an indication of success with the public, and proof that, for Renaissance humanists, the written medium of ekphrasis and the visual medium of engraving are transparent to each other, since one can without scruple restore the lost, or purely imagined, picture from Philostratus' text alone. Finally, Félibien, in his Entretiens sur les vies et sur les ouvrages des plus excellents peintres (1ère edition in 1666) [18], remains very much in the tradition of Vasari : since the aim of the work is to select " the most excellent painters ", it is the best of their work that will justify the selection ; it can only be reported in the form of praise, and the /// his words are full of laudatory adjectives.

The discriminating function of the review

However, compared to his Italian model, the form of Félibien's text has changed : dialogue, even in the polished, elegant and cautious form of an interview with attenuated dialogism, presupposes the plurality of points of view, hence the beginning of a critique. And it is necessarily on the painters' technique, i.e. on the " faire ", that this criticism can first be based. However, this is only a timid development, in a very anecdotal text where the description of paintings occupies a marginal place.

The institution of the Salons radically changes the situation. It is no longer a question of constituting a pantheon of painters, a virtual space of excellence whose legitimacy is only symbolic, but of reporting on a real exhibition, in which not only is there everything, sublime works and crusts, but where the reader, the eventual buyer, expects to be guided in his choice : the selection of works no longer pre-exists the text ; it now constitutes its aim.

There are therefore two competing models for accounting for paintings : the old model, inherited from the ekphrasis of antiquity, conceives the description of paintings as a performance : the text excellently expresses the excellence of the painting, an excellence that is not so much technical, as symbolic. The painting itself perfectly expresses the fullness of the epic, tragic, heroic values carried by its subject : the text celebrating the work therefore celebrates through it the values it has represented. The performance of ekphrasis establishes, as it were, a circulation of excellence.

The new model, imposed by the Salons, conceives the description of paintings as a discrimination : it sorts between the works exhibited. Only a judgment of taste can legitimize this sorting : while the gallery of paintings that are the subject of the ekphrasis presents itself as an objectively magnificent gallery, the discrimination operated by the review, even based on the technical evaluation of the painter's work, is a necessarily subjective discrimination. It thus unexpectedly opens up writing to the sphere of the intimate.

The public and the intimate

The journalistic model of the review is thus constituted from this founding contradiction : it is motivated by the emergence of a new public space, the Salon exhibition ; but it is implemented from an intimate sphere, where the judgment of taste is decided. The polarity of the public and the intimate is fundamental to the new relationship that the diary establishes between the subject and painting: it is in the singular, subjective experience of scopic crystallization - that is, of what intimately links the canvas to the viewer - that the collective, national destiny of painting is played out. Through this crystallization, which may or may not take place, and which it is now the journalist's duty to report on, it is neither God, nor the king, nor even the hagiographic writer, but the public set up as judge who will henceforth consecrate the painter's glory and define the features and directions of a French school of contemporary painting.

.

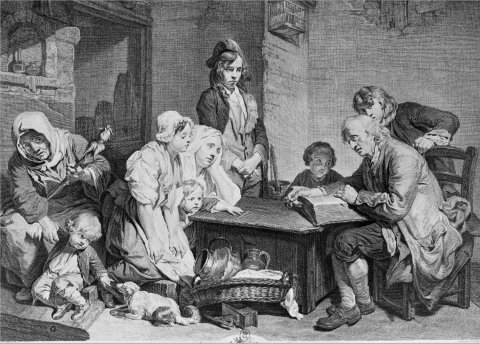

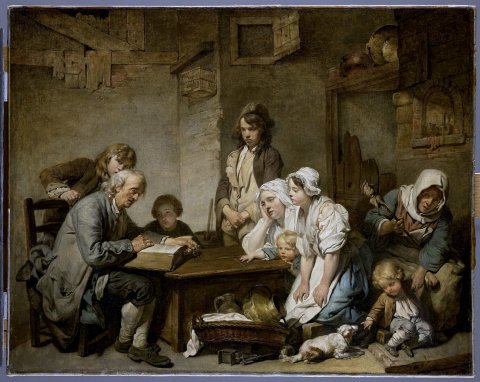

La Lecture de la Bible par l'abbé de La Porte

Early articles in the Mercure de France, libels by an Abbé de La Porte, a Mathon de la Cour or an Abbé Leblanc [19], however, still bear the mark of the rhetorical model of ekphrasis, by which all the pens of the time were trained. Take /// abbé de La Porte's commentary on a painting by Greuze that caused a sensation at the Salon of 1755. It is La Lecture de la Bible :

" A father reads the Bible to his children touched by what he has just seen there, he is himself penetrated by the moral he gives them : his eyes are almost wet with tears his wife, quite a beautiful woman, whose beauty is not ideal, but such as we can find in people of her kind, listens to him with that air of tranquility enjoyed by an honest woman in the midst of a large family which is all her occupation, her pleasures her glory. Her daughter beside her is stunned and distraught at what she hears; the older brother's expression is as singular as it is true. The little fellow who makes an effort to catch a stick on the table [20], & who has no attention for things he can't understand, is quite in the nature ; do you see he doesn't distract anyone, we're too seriously busy ? What nobility ! & what feeling in this good mother [21] who, without leaving the attention she has for what she hears, mechanically holds back the little spiegele that makes the dog growl : can't you hear how he annoys, showing him the horns ? What a painter! What a Composer ! " [22]

At first glance, and at the end of the review in particular, the rhetoric of praise remains the dominant model of enunciation, where the excellence of the painting (" Quelle noblesse ! & quel sentiment... ") consecrates the excellence of the painter (" Quel Peintre Quel Compositeur ! ").

From the ideal to the truth of nature

But this is only one outcome, and the starting point is quite another. Note immediately how Abbé de La Porte characterizes the beauty of the mother of the family, " quite a beautiful woman & whose beauty is not ideal, but such as we may encounter in people of her kind ". The competition between the ideal and the real cannot be expressed more clearly here the painting does not refer to the idealized world of symbolic performance, but to " people of her kind ", to those well-to-do, pious peasants whom, in the making of the work, it constitutes as a new category, endowed with an ideal of its own : in the text, the categories from which the judgment is elaborated are in the process of becoming rather than pre-existing.

The mother is " Assez belle " : availing herself of the singularities of the real world, the painting not only presents another ideal, another canon of beauty by the yardstick of this alternative ideal, she represents an average, almost ordinary beauty. The ideal of excellence falls.

What counts now is the truth of nature. This is first suggested by the " expression as singular as it is true " of the older brother standing behind the table, to the right of the seated mother and facing the reading father. (The detail of this arrangement is not given by Abbé de La Porte, who, in the tradition of ekphrasis, ignores the geometrical nature of the scene.) This singularity is ambiguous : does it refer to the ideal excellence of representation in general, or rather to the singular truth of peasant piety whose image Greuze constructs and constitutes the new ideal ? " Singulière " oscillates between excellence and strangeness : the left adolescent, hands folded, face closed, is not strictly speaking handsome, nor even excellent in his kind.

What makes it interesting is the average truth of its expression, which Abbé de La Porte's commentary calls us to judge not from the models of excellence bequeathed by culture, but from our average experience of the /// life.

With the description of the younger brother, this orientation of the text is confirmed : " Le petit bonhomme [...] est tout-à-fait dans la nature ". The truth of nature legitimizes a comical and unnoble gesture, which is not even justified by the general subject of the scene. The child wedged between the seated mother and the table, straining to grab a pencil in front of him, thus manifests his exteriority to the subject : but it's precisely because he has nothing to do with reading the Bible that he makes it true, that he looks as if he hadn't been composed [23]. The child leaves the subject, he " has no attention for things he cannot understand " : the incomprehensibility he points out inscribes the representation in reality, but indirectly leads back, through the profane way, to the deep religious content of the scene, to the incomprehensible sublimity of the divine Word. His distraction reveals the attention of the other family members, his divergence underlines the convergence of the other figures towards the Book.

Feeling and seeing the Word

Or precisely what is the subject of the scene ? La Lecture de la Bible does indeed place the text, and even the text par excellence that is the Bible, at the heart of pictorial representation. We saw in the ekphrasis of the Andrians how the commentary took advantage of this central discursive articulation to crush the image between the song in the painting and the discourse on the painting, thus evacuating the dimension of the visible.

But Abbé de La Porte adopts an entirely different strategy. Instead of reducing the scene to the enunciation it implements, he translates the text read, whose content is ignored, into sensible, visible effects. In the first proposition, " A father reads the Bible to his children " in the second, he is " touched by what he has just seen ". The father figures the content of what he reads, transforming the legible into the visible : his " penetrated " air, " his eyes wet with tears " give to see and understand a text that is not only incomprehensible, but, materially invisible to the viewer of the painting.

From this transfusion, which marks that the iconic support has ceased to be transparent, the composition is ordered as a gradation in the characters' attention to what is given to see, to this father who, eyes raised from over his Bible, makes by his tears tableau in the scene. Gradation, not communion; differentiation, not celebration.

The emergence of a visual dimension to the painting involves taking into account the geometricity of space : the extreme attention of the mother and elders to the father's reading contrasts with the distraction of the two little ones, one monopolized by his pencil, the other by his dog. This polarity forms a group around the mother. The Abbé, on the other hand, says nothing about the other two children flanking the father, even though Greuze has played the same differential game with them: the devout attention of the seated child is contrasted with the raised head of the older child standing behind his father's chair, turning away from the scene to meet our gaze as spectators. The father and mother facing him are arranged group against group, while the grandmother on the right, standing back, raising her head in the manner of the boy placed behind the father, on the opposite side of the canvas, designates offstage the vague exteriority of reality.

The range of attitudes doesn't fan out, then, as Abbé de La Porte's commentary suggests it is skilfully arranged in space it orders a geometrical layout, based in particular on the interplay between the scene /// (the father and mother face each other) and off-stage (the divergent gazes of the child in the chair and the child with the dog, the grandmother's mechanical activity). This arrangement echoes in the canvas the interplay of the public and the intimate: the stage is private, absorbed, woven of singular expressions and separate experiences, made up of a coalition of interior fors but the stage is visible only because it is bordered by an off-stage that opens it up to the public : the Bible reading thus interweaves the public and the intimate; it is a scene offered to the public as an example because it is a silent scene where, the father's word having been suspended, each person gives free rein to an inner emotion that he or she does not communicate. Although common, religious emotion is disseminated ; although exemplary, it is individual.

Features of the new model

At first glance, then, nothing has changed : the abbé describes very little ; he narrates the scene and praises the painter. We don't know who's on the right or left, standing or sitting no distinction of planes no colors. In the rhetorical tradition of ekphrasis, the account is both narrative and epidictic. The constitution of a judgment of taste, the presence of an audience summoned to judge and discriminate between works, the passage from an absolute, glorious value of painting to a relative, marketable value, subject to evaluation and criticism, seem to have left no trace in the well-oiled mechanics of this performance.

It is in fact in depth, at the level of the very composition of the canvas, that the transformations take place. Abbé de La Porte concludes his commentary with a double exclamation : " What a Painter ! Quel Compositeur ! ". The composition of the canvas tends to become the central object of the review. Composition the word is ambiguous, still designating the narrative detail of the subject, but already introducing an attention to the arrangement of figures in space, to the geometry of the device. It was from this new, or at least heightened, attention to composition that the journalistic revolution was to begin. Moreover, reporting is not simply a new way, different from ekphrasis, of describing the same painting. Artistic production cannot be dissociated from reporting techniques they evolve in the same movement, and attention to canvas composition goes hand in hand with a profound transformation in the way artists order their compositions. It is therefore in painting itself, in the content of what is painted, that we must first look for traces of this new relationship of the public to the work, of the critic to the paintings.

The demand for discrimination, demanded by the public, the readers, manifests itself in painting through the discrimination of the attitudes of the characters : the spectators represented in the canvas put into abyme the relationship of the real spectators facing the canvas the range of intimate feelings there thematizes and figures the range of the public's judgments.

This judgment is based on an assessment of the canvas's geometric organization, i.e. its ability to manage this new relationship between the public and the work. Formally, the terms " composition " and " disposition " are appearing more and more frequently in the review, but above all these terms refer to a very specific device for the audience, it's a question of entering the stage or not, of penetrating an intimate space or not. While the practical layout of the canvas remains vague and imprecise in the report, a polarity emerges between attention and distraction, between the enclosure of intimacy and openness to exteriority. This polarity is constitutive of what J. Habermas calls the new public space.

Fourth part : the scenic compromise

The concept is ungrateful : in the intellectual realm, /// the greatest inventions are often the simplest. Their obviousness, when it asserts itself, makes them go unnoticed. Diderot radically revolutionized the way we see painting, and hence, even more essentially, the way we conceive of the development of thought, whose iconic foundations he unraveled. Diderot makes us see images, not only in the sensitive dimension of their visibility, but in the metaphysical dimension of the intellectual process they reveal, a process that is none other than the very march of the mind.

This revolution first manifests itself in the Salons through words to which one would a priori be far removed from granting philosophical dignity : " à gauche ", " à droite ", " devant ", " derrière ", " debout ", " assis ". Diderot is more precise than his follicular comrades, longer too, which a priori is not necessarily a quality.

Hasard and encounter : the paradox of geometrality

Let's take as an example the review of Greuze's Accordée de village, a painting very close in composition to La Lecture de la Bible, to which, incidentally, Diderot explicitly compares it. L'Accordée de village, hung late at the Salon of 1761 to better spare expectation and effect, caused a sensation [24]. Diderot set about the account while his Salon de 1761 was finished : The Accordée de village therefore comes at the end of the text, and not in the Livret order that Diderot generally follows.

" At last I've seen it, this painting by our friend Greuze ; but it wasn't without difficulty ; it continues to draw a crowd. It's of a father who has just paid his daughter's dowry. The subject is pathetic, and one is won over by a gentle emotion as one watches it. The composition seems to me very beautiful it's the thing as it must have happened. There are twelve figures each is in its place, doing what it should. How they all fit together! How they undulate and pyramid ! I don't care about these conditions however, when they meet in a piece of painting by chance, without the painter having had the thought of introducing them, without him having sacrificed anything to them, they please me. " (VERS 232 ; DPV XIII 266-267.)

Every sentence here bears the stamp of the semiological revolution that installs geometrality at the heart of new representational devices, both visual and textual.

" It continues to draw a crowd " : the painting is introduced neither by the painter's presentation, nor by the assertion of an intrinsic excellence, but by the crowd it has aroused. It's a painting of the real exposed in the real.

The painting does not arouse admiration, but " a gentle emotion in looking at it ". Diderot describes a sensitive contagion, something that is communicated from close to close, that is, a community in progress, which is not instituted in advance. Not only does the break fall from the canvas to the Salon, from the emotion of the family members in the engagement scene to the emotion of the spectators in the Salon carré, but the Salon audience is won over only gradually, by the magnetism of the gaze alone : it's " by looking at it ", in other words by dint of looking at it, that Greuze's painting ensnares the spectators it has by chance encountered in its device (its " composition ").

The painting is therefore not objectively excellent, but subjectively pleasing : " la composition m'en en a paru belle " ; " the composition struck me as beautiful ". Systematically, the arrangement of figures in space and the affirmation of the singularity of the viewing subject are associated. There's a paradox here what's more objective than order ? what's more subjective than the judgment of taste ? The new model is built on this paradoxical encounter, this reversal that makes geometrality and subjectivity communicate, the deployment of space and critical appreciation.

This encounter, this paradox, the painting must anticipate them, prepare for them : it's not just a matter of giving the illusion of naturalness to a skilfully concerted composition ; the device must be conceived fundamentally as τύχη, i.e. as the reversion of chance and encounter, singularity and communion this very reversion forms the basis of the representation's device, what we've designated as geometrality. The figures " all link up " in the manner of a signifying chain : geometrality is not just the arrangement of objects in space ; it guarantees their discursive integration, it reduces visible space to a logical structure. Undulating and pyramidal, geometrical space is not a topographical survey, but the realization of an ideal form, reducing the real to the purity of a figure, a geometric formula. The real is thus reduced by geometrality, but reduced to be immediately redeployed : " it's the thing as it must have happened ", meeting " by chance ", without the intention, without the " thought " even of the painter.

The trap of the gaze, constitutive of the device, lies entirely in what, geometrically, folds back (from the engagement scene to the triangle of the visual pyramid) and then redeploys (from the triangle to the real). Through this trap, the crude is the stylized, the pleasure of recognizing instituted forms is manifested by a casualness towards these forms : " I don't care about these conditions " the laws of geometry are there and not there, summoned and revoked, valued purveyors of pleasure and abhorred figures of constraint.

Line, figure, discourse : the ancient symbolic articulation

However : from now on, everything will be a matter of " place " and " prescription " :

To the right of the one viewing the piece is a tabellion [25] seated in front of a small table, his back to the viewer. On the table, the marriage contract, and other papers. Between the tabellion's legs, the youngest child of the house. Then, continuing to follow the composition from right to left, an eldest daughter stands, leaning on the back of her father's armchair. The father seated in the armchair. In front of him, his son-in-law stands, holding the bag containing the dowry in his left hand. The granted one, also standing, one arm passed limply under that of her fiancé; the other arm grasped by the mother, who is seated below. Between the mother and the bride, a younger sister stands, leaning over the bride, and an arm thrown around her shoulders. Behind this group, a young child rises on tiptoe to see what's going on. Below the mother, on the front, a seated girl with small pieces of cut bread in her apron. Far left, in the background and away from the scene, two maids stand and watch. On the right, a tidy pantry, with its customary contents, forms part of the background. In the middle, an old harquebus hanging from its hook; then a wooden staircase leading to the floor above. In front, on the ground, in the empty space left by the figures, close to the mother's feet, a hen leads her chicks to whom the little girl throws bread; a bowl full of water, and on the edge of the bowl a chick, beak in the air, to let the water it has drunk down into its crop. That's the general order, now let's get down to the details". (Continued from previous.)

Here, modern description bursts into the text, breaking syntax, abolishing verbs. Everything is relative position, disposition. Parataxis is the verbal expression of geometrality it restores as juxtaposition in space the discursive line unrolled, in the old system inherited from ekphrasis, by the subject's narrative.

Through this juxtaposition, the viewer of the canvas becomes part of the composition ; he is one more figure juxtaposed to the painted figures. Diderot writes " A droite de celui qui voit le morceau " (and not face à celui) as he further writes " Devant lui ", " Derrière ce groupe " or " Au-dessous de la mère " : the external spectator is, but is only the first signifier. Ultimately, then, space is still reduced to a line, on the model of an inverted reading that takes place " continuing to follow the composition from right to left ".

The second part of the account is an even more detailed description. However, it is no longer about the order, but about the figures : " The fiancé is of a figure quite pleasant " ; " The painter has given the fiancée a figure charming " ; " For this younger sister [..], it's a character quite interesting ". So we're back to a rhetorical model, to this taxonomy of characters and passions of the soul that unfolds out of space, in the range of possibilities.

Figures are discourse-types. From his " air de bonhommie qui plaît ", Diderot deduces the father's discourse : " Le père est le seul qui parle. The rest listen and remain silent " In the same way as in La Lecture de la Bible, the painting is symbolically ordered around and from the speech uttered by the Father this speech is the performance that the figures translate iconically. The model of oratorical eloquence is underscored by the father's gesture :

" With arms outstretched toward his son-in-law, he speaks to him with a heartfelt effusion that enchants he seems to be saying : Jeannette is gentle and wise she will make you happy think of making her happy... or something else about the importance of the duties of marriage.... What he says is surely touching and honest. "

Through this oratorical posture, which Diderot takes full advantage of, Greuze updates the value-celebrating function to which the ekphrasis identifies painting, whose iconicity must fade before the word it carries. And yet, in this very word, something new emerges, symptomatic of the new semiology : " she'll make you happy ; think of making her happy " ; there's the interweaving, the reversion of a chiasmus by which the discourse mimics as closely as possible what's at play in the geometrical order, this coming and going of the eye and the gaze, this entanglement of the outside and the inside, the public and the intimate. The father's solemn discourse is matched by the mother's interior discourse, reported in free indirect style, as well as that of the jealous sister, and the maids who are also impatient to get married : a polyphony sets in, a verbal dissemination that corresponds to the visual discrimination established by geometrality.

So geometrality doesn't replace the old symbolic organization we'd already seen at work in Philostratus rather, it superimposes itself on it, adding an extra dimension to the image device. The conjunction of these two dimensions constitutes the scenic device, an ancient device, invented by the Renaissance, but which only becomes textually aware of itself with the critical revolution of journalistic reporting.

Scopic crystallization

Diderot spoke from the start of an improbable /// rencontre the rules of art, the snaking line formed by the figures, the pyramidal composition of the whole, meet as if by chance in this scene that seems to have been taken from life. As we have emphasized, this meeting is not just another artifice, but the foundation of the device, the fundamental reversion. This is what is at stake in this encounter, the superimposition of the geometrical and symbolic dimensions of the device. This superimposition reveals a third dimension, the purely and exclusively visual dimension of the device. Beyond the methodical reading of the layout, the deciphering of the figures, the deep spring of the gaze-trap constituted by the device is illogic, i.e. strictly speaking irreducible to discourse. Something attracts the eye, holds attention outside the subject, precisely because it stains, because it is outside the subject.

" And this hen who has led her chicks to the middle of the stage, and who has five or six young, just as the mother at whose feet she seeks her life has six or seven children ; and this little girl who throws bread at them, and who feeds them. It has to be said that all this is charmingly appropriate to the scene, the place and the characters. It's an ingenious little stroke of poetry" (VERS 233  DPV XIII 270.)

The line is the short-circuit of the encounter that achieves the " charming convenience ", in other words the constitutive superposition of the device. The hen leading her chicks in the left foreground plays the same role in the composition of L'Accordée de village as the dog in the right foreground of La Lecture de la Bible. The little boy held back by the grandmother while he makes horns with his fingers to annoy the dog, in the 1755 painting, corresponds to the little girl distributing her grain to the hen and chicks in the 1761 painting.

Diderot would later note that " The head of the father who pays the dowry is that of the father who reads Scripture to his children " : the homology of the two paintings was therefore not lost on him. Yet his analysis is not at all the same as that of Abbé de La Porte. Whereas the abbé suggested the boy's distraction and the heterogeneity of the two actions, Diderot insists on the parallelism between the hen's posture and the mother's posture. Diderot, on the other hand, highlights a dispositif, i.e. different levels for a single action or meaning. The device recovers otherness, the exteriority of reality, and brings it back into the subject. More flexible than rhetorical structure, it integrates what escapes discourse.

No doubt Greuze has evolved and progressed in his art nothing connects the dog to the mother in La Lecture de la Bible, whereas the hen can metaphorize the mother in L'Accordée de village. But this integration of differences into the stage device is above all symptomatic of the semiological revolution taking place: the hors(off-stage, off-game, off-subject) is no longer appropriate. At the back of L'Accordée, smooth wall and closed door establish no perspective depth, no opening towards a vague space.

In this closed system, it's not the difference, it's the line, the semiotic short-circuit of meaninglessness that makes sense : the incongruity of the hen, brought back to the relevance of the subject, reveals the scene. She " has led her chicks to the middle of the stage " ; she is " of charming propriety with the scene ". The stage is the fundamental medium of representation it appears here as a compromise between the rhetorical logic of subject, of performance and the visual logic of composition, of order. The stage is a place, a milieu, and the stage is a word, an oratorical performance. Scopic crystallization introduces a detour for the eye via the hen, only to bring it back to the scene. /// to the father and, behind the words he delivers, to the hierarchy he institutes:

The father's role in the life of the family

" It is the father who principally attaches the eyes then the husband or fiancé then the granted, the mother, the younger or elder sister, according to the character of the one looking at the picture then the tabellion, the other children, the maids and the background ; sure proof of a good order. " (Continued from previous.)

It is no longer the father's word, but the visual effect of his figure that becomes the principle of representation. The path of the eye restores the hierarchy of figures; the scopic play makes geometrical order and symbolic hierarchy coincide. In this sense, the scenic device constitutes a compromise: it maintains the frameworks and structures of the old symbolic institution, while replacing the traditional verbal spring with a new visual spring: the stage is what makes these two springs, these two logics, coexist.

Audience discrimination versus figure discrimination : shifting the differential game

The stage thus pacifies the semiological conflict in a way, a deep and enduring conflict, of which the modalities of the painting account are, we understand, only a peripheral avatar. It's undeniable that the scenic device has a unifying and integrating function: but the forces of discrimination and dissemination that motivated its generalization are echoed at another level. The scene dialogizes. We've already seen how the father's discourse is contaminated by the interweaving of the gaze, the chiasmus of the visible, before being disseminated into the inner discourse of the mother, the sister and the maids. But the dissemination doesn't stop there. The scene only calls for comment from its internal spectators, painted on the canvas, in anticipation of a more fundamental call: the call for public judgment, for dialogue with the public. Criticism fulfills the scene and re-establishes the fundamental heterogeneity of representation :

" Greuze can be criticized for repeating the same head in three different paintings. The head of the father who pays the dowry is that of the father who reads Scripture to his children, and I believe also that of the paralytic [26], or at least they are three brothers with a great family air.

Another flaw. This elder sister, is she a sister, or a servant ? If she's a servant, she's wrong to be leaning on the back of her master's chair, and I don't know why she envies her mistress's fate so violently. If she's a child of the house, why this ignoble air, why this neglect? Happy or unhappy, she had to be dressed as she should be at her sister's engagement party. I can see that people are mistaken; that most of those who look at the picture take her for a servant, and that the others are perplexed. I don't know if this sister's head isn't also that of the Laundress [27].

. A woman of great wit recalled that this painting was composed of two natures. She claims that the father, the fiancé and the tabellion are indeed peasants, country people ; but that the mother, the fiancée and all the other figures are from the Paris market. The mother is a fat fruit or fish merchant the daughter is a pretty bouquetière. This observation is, at least, fine ; see, my friend, if it's right. "

Greuze's scene provokes debate in the audience crowded in front of it. Diderot begins timidly with a " on " that might refer only to him ; but he soon mentions " most of those who look at the painting " and " others " ; then he reports the remark of " a woman of much wit " ; finally he solicits Grimm's opinion : " see, my friend, if she is right ". /// The scenic device abolishes traditional boundaries, between the real and the performance (" c'est la chose comme elle a dû se passer), between the performance and the Salon audience (" A droite de celui qui regarde le morceau est un tabellion... "), between the real audience crowded in front of the canvas and the virtual audience reading Diderot's leaves and breaking into his conversation with Grimm (" voyez, mon ami ").

Or precisely what is being debated is the discrimination of the figures : the father of L'Accordée de village is not a singular figure, he has already been used elsewhere is the jealous sister a sister or a servant : here again it's the singular characterization of the figure that is missed more generally are the figures from the countryside or the underbelly of Paris, real peasants or S.D.F. that Greuze picked up as cheap models downstairs ?

The dialogism instituted by the scene attacks what in the scene belongs to the old semiological system, the taxonomy of figures, the logical characterization of characters and the differential system it produces. The scene is thus a compromise ; but at the same time it reflects and perhaps even aggravates the semiological crisis.

The money of the stage

All the same, the journalistic model emerges with force here the public is the ultimate judge it compares works with each other, but also with their real model it therefore evaluates a market value, an excellence that ceases to be absolute.

It's perhaps no coincidence that Diderot began his description of the painting's order with the tabellion, i.e. the man charged, in the scene, with establishing the commercial transaction covered by the father's fine moral discourse and the virtuous emotion of the engaged couple and the rest of the family. Seated in the foreground, with his back to the viewer of the canvas, the tabellion is the visual clutch of the scene : from every point of view, then, he provides the interface between the real and the symbolic.

The remark about the Halle models refers a second time, but still indirectly, to economic reality : we're getting closer to the canvas, though. The money at stake is no longer the virtual money involved in the subject represented, but the real money required to manufacture the painting-object. Diderot does, however, reserve explicit reference for the last paragraph :

" A rich man who would like to have a fine piece in enamel, should have this painting by Greuze executed by Durand who is skilled with the colors that M. de Montami has discovered. A good copy in enamel is almost regarded as an original ; and this kind of painting is particularly destined to copy. " (VERS235 ; DPV XIII 272.)

Didier-François d'Arclais de Montamy had been a friend of Diderot's since at least 1755. In 1765, it was Diderot who published his Traité de couleurs pour la peinture en émail et sur la porcelaine : the review here turns unabashedly into an advertisement, while Diderot points out the economic dimension of the aesthetic revolution initiated by Greuze. Greuze's painting is not a painting of aristocratic rarity and excellence it is a painting of consumption and distribution, a painting " to be copied ", already preparing the leap from representation to mechanized reproduction. Like the Protestant Reformation, which relied on the printing press, the aesthetic and moral reform of which L'Accordée de village is a manifesto will rely on engraving and copying. This reform can therefore be reduced neither to a question of form (Greuze's style), nor to a matter of content (bourgeois painting) the representational device it institutes, placing the object of representation in an unprecedented network in which the public plays a major role, articulates stage and value in an unprecedented way.

Notes

[20] A pencil, rather ? It's true that in the eighteenth century, pencils were pure paste or lead, without wooden sheaths.

///

Les Essais sur la peinture sont une annexe du Salon de 1765. Most of it was inserted by Grimm in the issues of the Correspondance littéraire from August to December 1766.

TO 522. For Plato, painting is a " representation of representation ", φαντάσμα φαντάσματος, because the object it imitates is itself the representative, the representation of an idea, of a more general abstract category. The hierarchy is thus as follows : the general idea of bed the particular, real, concrete bed that represents this idea the painting that represents this particular bed, i.e. that represents a representation of the idea of bed. For Plato, each additional level of representation constitutes a further degradation of the idea.

Else-Marie BUKDAHL, Diderot critique d'art, translated from the Danish by J. P. Faucher, Copenhagen, Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1980, 2 volumes. See also the extensive critical apparatus, in the Hermann edition of the Salons of 1765, 1767 and 1769 (DPV).

Jacques CHOUILLET, La Formation des idées esthétiques de Diderot, Paris, A. Colin, 1973, second part, chapter IV, pp. 553-594.

Jean STAROBINSKI, Diderot dans l'espace des peintres, Cahiers du musée national d'art moderne, n°24, Summer 1988, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Paris, 1991.

Bernard VOUILLOUX, " La description du tableau dans les Salons de Diderot ; la figure et le nom ", Poétique, tome 19, February 1988, n°73, pp. 27-50.

What follows for the critical analysis of the Salons is a shift in perspective that may seem paradoxical, even unjustified : it is not, in our view, in relation to the writings on painting that have proliferated since Alberti up to the reflections conducted in France around the Royal Academy by Lebrun, Coypel, Roger de Piles, Félibien and others, that this ritual at work in the Salons is constituted and subverted, but it is to a much older, Greek and Roman tradition of descriptive practice that it refers. The destination of these writings is not the same : the first are addressed, in a technical aim of production, to painters and those who want, by breaking in, to enter their space ; the second, which interest us here, concern, in an ideological aim of consumption, virtual spectators and, among them, the enlightened, or likely to be enlightened, public of amateurs (Diderot always distinguishes in his Salons between the painter's gaze, led astray by technical interest, that of the amateur for whom he destines his writing, and that of the people, uneducated, nevertheless valid as degree zero of the cultural referent). Let's add to this that while ancient ekphraseis are part of the common classical culture in the eighteenth century, the knowledge and dissemination of Italian and French writings on painting, even the most recent, is necessarily more superficial and limited to a much more restricted audience. Diderot mentions in the Salons the Histoire naturelle by Pliny the Elder for what is written there on painting (Salon de 1765, PLINE XXXV, 10, 92 in VERS 336 ; XXXIV, 5, 10 in VERS 504 ; Salon of 1767, PLINE XXXV, 10 in VERS 655, Timante's Agamemnon, reprinted in Pensées détachées sur la peinture, VERS1047 ; Salon de 1769, VERS 879, Diderot defines the current Dalon critic as a " Pline moderne "), never Alberti (absent from the Encyclopédie even in the PERSPECTIVE article), nor his French epigones. The /// Pausanias's ekphraseis are the subject of several letters to Falconet on Polygnote (Le pour et le contre, starting with letter VII). By contrast, Coypel appears four times, as a painter only, a detestable model of rococo mannerism (CFL V 89, VI 109, VI 235, VII 298). Le Brun is also mentioned only as a painter, an exemplary model of classicism (CFL II 506, VI 51, VII 280, 313, 367, 388, VIII 444). No trace of Félibien, Piles or even Abbé du Bos. If Diderot borrows from them, he does not claim to be their author.

The Greek title is Eikones, the images.

There would have been at least two Philostrates. The one we're interested in here would have been born around 165 and originally from Lemnos, before moving to Athens and then Rome as a teacher of rhetoric. He would have frequented the court of Septimius Severus.

The mention is laconic : " Those of Andros also claim that among them during the festivals of Bacchus the wine flows of its own accord in his temple. But if on the faith of the Greeks we believe these marvels, it will only remain to believe that the Ethiopians who are above Siené debit about the table of the sun. " (Description de la Grèce, VI, " Voyage de l'Élide " chap. 26, §2, in Abbé Gédoyn's translation, 1731.) See also PLINO THE ANCIENT, Natural History, II, 106, quoted in note to the Greco-Latin edition of Philostratus by Gottfridus Olearius, Leipzig, Thomas Fritsch, 1709, p. 799 : In Andro insula, templo Liberi Patris, fontem Nonis Ianuariis semper vini sapore fluere Mucianus ter Cos. Credit. (He also refers to l. XXXI, f. 13.) Both Pliny and Pausanias, however, speak of a wine fountain in the temple, not of a river flowing into the sea.

We quote Philostratus in Auguste Bougot's translation revised by François Lissarague, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 1991.

Smilax, or sarsaparilla, a kind of thorny bindweed, and ivy are emblems of Dionysus. Euripides' Bacchae " crown themselves with ivy, oak leaves and flowering smilax ".

The thyrse is a staff surrounded by ivy or vine leaves and topped with a pinecone. An attribute of Dionysus, it is carried by the bacchantes.

Fish-tailed men, the Tritons are always equipped with a conch shell, which they usually sound like a trunk.

Cômos is the god of laughter and comedy, which is etymologically the song of Cômos.

Painting is Greek for graphè, i.e. writing, line : language reinforces identity, categorical indifferentiation, of discourse and image.

LES/ IMAGES OU TABLEAUX / DE PLATTE PEINTURE / DES DE DEUX / PHILOSTRATES SOPHISTES GRECS / et les Statues de Callistrate / Mis en Français par BLAISE DE / VIGENERE Bourbonnois Enrichis / d'Arguments et Annotations / Reueus et corrigez sur Loriginal / par un docte personnage de ce / temps en la langue grecque / ET / REPRESENTEZ EN TAILLE DOUCE / en cette nouvelle edition / Avec des epigrammes sur / chacun diceux par / ARTVS THOMAS SIEVR D'EMBRY / Avec Privilege du Roy. Jaspar Isac Incidit / A PARIS / Chez Sebastien Cramoisy /Imprimeur ordinaire du Roy / rue Sainct Iacques aux / Cicognes M DC XIIII.

See the edition by René Démoris, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 1987.

Most of the texts reporting on the Salons, apart from Diderot's Salons, were collected by Mariette, Cochin and Deloynes in the Cabinet des estampes of the Bibliothèque nationale. On these texts, see Michael FRIED, La Place du spectateur, Chicago, 1980, French trans. Gallimard, 1990.

Understand : this grandmother.

Sentimens sur plusieurs des tableaux exposés cette année au grand sallon du Louvre, 1755, p. 15. This opuscule is signed D-p-te PDM, which Deloynes suggests reading D[e La]p[or]te P[rofesseur] D[e] M[athématiques].

In his commentary on Abbé de La Porte's text, Michael Fried insists on this point and highlights, as a new characteristic of painting at the time, " the primacy of absorption " (Michael FRIED, op. cit., p. 25).

Grimm in fact specifies, in the Correspondance littéraire, in the introduction to Diderot's comment : " During the last ten days of the Salon, M. Greuze exhibited his painting of The Marriage, or the moment when the father of the granted delivers the dowry to his son-in-law. This painting is, in my opinion, the most pleasant and interesting of the whole Salon; it had a prodigious success it was almost impossible to get near it. I hope that engraving will soon multiply it to satisfy all the curious. "

The tabellion is a kind of notary, summoned here to draw up the marriage contract.

The Filial Piety, also known as The Paralytic, is considered the narrative sequel to The Village Accordion. In its definitive version, this painting did not yet exist in 1761, but Diderot was able to see a preparatory version at the Salon (VERS 227 ; DPV XIII 259-260). At least two of these exist today, one in the Musée des Beaux Arts in Le Havre, thought to date from 1760; the other is a brush and wash drawing on bistre paper in the Louvre (RF 36504, Recto), thought to date from 1761. The final painting was exhibited at the Salon of 1763 (VERS 275 ; DPV XIII 394) and purchased by Catherine II : it is still preserved at the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, inv. 1168.

La Blanchisseuse, oil on canvas, 40.6x32.9 cm, Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum, 83.PA.387. The painting was also exhibited at the Salon of 1761 (see Diderot, VERS 227 ; DPV XIII 258).

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Les Salons de Diderot, de l’ekphrasis au journal », Vérité, poésie, magie de l’art : les Salons de Diderot, cours donné à l'université de Provence, Aix-en-Provence, automne 2011.

Diderot

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Diderot

Les Salons

L'institution des Salons

Peindre la scène : Diderot au Salon (année 2022)

Les Salons de Diderot, de l’ekphrasis au journal

Décrire l’image : Genèse de la critique d’art dans les Salons de Diderot

Le problème de la description dans les Salons de Diderot

La Russie de Leprince vue par Diderot

La jambe d’Hersé

De la figure à l’image

Les Essais sur la peinture

Atteinte et révolte : l'Antre de Platon

Les Salons de Diderot, ou la rhétorique détournée

Le technique contre l’idéal

Le prédicateur et le cadavre

Le commerce de la peinture dans les Salons de Diderot

Le modèle contre l'allégorie

Diderot, le goût de l’art

Peindre en philosophe

« Dans le moment qui précède l'explosion… »

Le goût de Diderot : une expérience du seuil

L'Œil révolté - La relation esthétique

S'agit-il d'une scène ? La Chaste Suzanne de Vanloo

Quand Diderot fait l'histoire d'une scène de genre

Diderot philosophe

Diderot, les premières années

Diderot, une pensée par l’image

Beauté aveugle et monstruosité sensible

La Lettre sur les sourds aux origines de la pensée

L’Encyclopédie, édition et subversion

Le décentrement matérialiste du champ des connaissances dans l’Encyclopédie

Le matérialisme biologique du Rêve de D'Alembert

Matérialisme et modélisation scientifique dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Incompréhensible et brutalité dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Discours du maître, image du bouffon, dispositif du dialogue

Du détachement à la révolte

Imagination chimique et poétique de l’après-texte

« Et l'auteur anonyme n'est pas un lâche… »

Histoire, procédure, vicissitude

Le temps comme refus de la refiguration

Sauver l'événement : Diderot, Ricœur, Derrida

Théâtre, roman, contes

La scène au salon : Le Fils naturel

Dispositif du Paradoxe

Dépréciation de la décoration : De la Poésie dramatique (1758)

Le Fils naturel, de la tragédie de l’inceste à l’imaginaire du continu

Parole, jouissance, révolte

La scène absente

Suzanne refuse de prononcer ses vœux

Gessner avec Diderot : les trois similitudes