Diderot composed Le Fils naturel and the Entretiens in the late summer of 1756. The serious comedy of Le Fils naturel is embedded in the fiction and commentary of Entretiens, a promenade during which the melancholy Dorval answers Diderot's questions.

The cabal ignited by Choiseul and relayed by Fréron and Palissot made the play's performance impossible: the text therefore appears before the play was performed 1.

The stage as a space of invisibility

In a way Le Fils naturel anticipates its unrepresentability through the fictional framework in which it is inscribed. Indeed, Diderot introduces the text printed in 1757 with an account of his visit to Dorval, presented as both the protagonist and author of the play, performed not on a theater stage but in his own salon, to commemorate a family history actually experienced. Dorval invites Diderot to attend, surreptitiously, the annual performance scheduled to take place for the first time the following Sunday:

Next Sunday we perform for the first time something they all agree is a duty.

Ah, Dorval, I said to him, if I dared!... I hear you, he replied; but do you think this is a proposal to make to Constance, to Clairville, and to Rosalie ? The subject of the play is well known to you; and you'll have no trouble believing that there are a few scenes where the presence of a stranger would get in the way a lot. However, I'm the one who's tidying up the living room. I make no promises. I won't refuse you. I'll see.

Dorval and I parted. It was Monday. He didn't say a word to me all week. But on Sunday morning, he wrote to me..... Today, at three o'clock sharp, at the garden gate.... I went there. I entered the salon through the window; and Dorval, who had pushed everyone aside, placed me in a corner, from where, without being seen, I saw and heard what is about to be read, except for the last scene. (P. 1083; DPV X 16-17.)

What follows is not a performance, but a commemoration, and a most intimate one. That's why, according to Dorval, the other members of the family-Constance his wife, Clairville his friend and brother-in-law, Rosalie his sister-couldn't accept the slightest spectator: "the presence of a stranger would be very troublesome". The word spectator is carefully avoided. The impossibility of attending the show is clearly signified, but not explicitly formulated, as if there were here, at stake, a prohibition too strong to be verbalized. The essential statement, that attending the performance is impossible, is missing from the text and, on several occasions, must be mentally substituted.

First is Diderot's veiled request, whose aim rests entirely on the suspension points: "Ah! Dorval," I say to him, "if I dared!... [= attend this performance]" Dorval's reply, "do you think this is a proposal to be made", evokes a proposal she doesn't name and doesn't justify a refusal whose motive she only hints at. Diderot, whom Dorval "hears" half-heartedly, is sent back to his belief ("croyez-vous...", "vous n'aurez pas de peine à croire..."). As for the final overture, it could not be more laconic: "I do not promise you. I will not refuse you. Promise what? Refuse what? It remains unsaid. Same ellipsis in the invitation: "Today, at three o'clock sharp, at the garden gate...". Today what? What's to be done, what's going to happen "at precisely three o'clock at the garden gate"?

The fact of the performance, the verbal action of attending, of watching what is going to be played, are elided. A taboo sets in, a reticence, at the very threshold of the performance. The performance is based on, and opens up to, the impossibility of being represented, the verbalization of the events that have built and, in a way, founded Dorval's family, and this verbalization is itself inverbalizable! Here we see the establishment of an originary signifier, the signifier of the absence of signifier 2, a signifier that is situated only at the negative limit of the order of signs and can find only in space, in the configuration of the scene, in its articulation with the gaze that circumscribes it, the means, nonetheless, to signify.

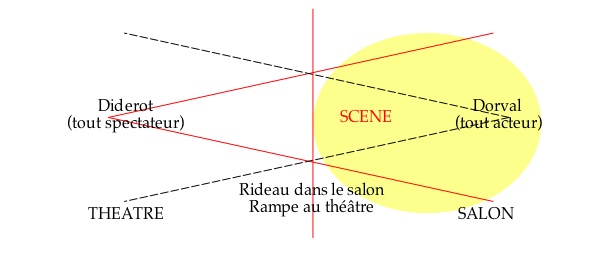

The scenic device, with its constitutive ambiguity: salon from theater, theater stage in salon.

The scenic space is a space stricken with invisibility 3, which cannot be seen without crossing, transgressing a grave and solemn interdict. The reticence of Diderot and Dorval's dialogue foreshadows this prohibition. Diderot's path, entering not through the door but through the salon window ("J'entrai dans le salon par la fenêtre") topographically signifies this interdict: hidden Diderot sees without being seen; with Dorval's complicity, he installs himself in the position of voyeur, exploiting a perverse impulse and enjoying it. Fiction thus creates for Le Fils naturel a wholly exceptional situation. But at the same time it symptomatizes every classic performance situation. In the auditorium, the brilliantly lit stage contrasts with the darkened parterre. Everything is done so that the audience can see the stage, but also, in reverse, so that the actors ignore the audience. The performance establishes an asymmetrical relationship between two gazes: the blinding gaze of the audience, enveloping and drowning the stage in light; the blinded gaze of the actor, walled into the darkness of the auditorium, cut off, entrenched, isolated. On the one hand, a seeing for want of saying: the audience witnesses everything but must remain mute; on the other, a saying for want of seeing: the actor holds the floor but is supposed to ignore the space outside the stage and, more generally, the conditions of illusion, the processes of the theatrical factory that allows his word to come through.

The unrepresentability of the performance space is no mere coquetry of an author seeking to spice up his fiction. There's a real issue at stake here, which the fiction underlines a second time at the end of the play:

I promised to say why I didn't hear the last scene; and here it is. Lysimond was no more. A friend of his, who was about his age, and had his height, voice, and white hair, had been engaged to replace him in the play.

This old man entered the salon, just as Lysimond had entered it the first time, held under his arms by Clairville and André, and covered in the clothes his friend had brought from prison. But scarcely had he appeared than, this moment of action putting back before the eyes of the whole family, a man they had just lost, and who had been so respectable and so dear to them, no one could hold back their tears. Dorval wept, Constance and Clairville wept. Rosalie stifled her sobs and looked away. The old man representing Lysimond became confused and began to cry too. The grief passed from masters to servants, became general, and the play never ended. (P. 1126; DPV X 83.)

The entrance of Lysimond, the father of the family, into the salon is not just a pathetic episode that revives overly moving memories. It also introduces a level shift in the performance: while all the actors are really the characters they play, the father of the family is played by a stranger. Yet Dorval made it clear in the opening pages that such a performance could not be shared with a "stranger".

The entrance of the false Lysimond introduces between the protagonists of the salon the difference between the real people and the played character. In so doing, it projects the real family, now spectators of the actor Lysimond, from the present and visible non-scene to the unrepresentable grief that is to be commemorated: it puts before the eyes("this moment of action putting back before the eyes of the whole family a man they had just lost..."). Paradoxically, the friend hired as an actor acts as a tableau, revealing through the effect he produces the fundamentally blinded nature of the scenic space: tears offend the view; Rosalie "averted her gaze". The interruption of the show thus signifies its fulfillment. It realizes the scenic space as a space of invisibility, i.e. based on the shift from a panoptic status (from the outside, it's totally visible) to a blinded status (inside, the protagonists can no longer see anything at all).

The screen of representation

In theater, the stage is an unstable space, whose precarious existence depends on the establishment of a screen of representation that delimits and designates it. This screen is concretely manifested by the curtain and the light rail that separate the audience from the actors. We must always be on the verge of forgetting if the illusion, the adherence to theatrical fiction, is to function, but only on the verge, failing which the illusion unravels and the performance is interrupted:

.

The representation had been so true, that forgetting in several places that I was a spectator, and an ignored spectator, I had been on the point of stepping out of my place, and adding a real character to the scene. (P. 1126; DPV X 84.)

In De la poésie dramatique (1758), Diderot would use this same formula of the spectateur ignoré to characterize not the singular adventure of the Fils naturel, but the general dramaturgical rule:

The spectators are but ignored witnesses to the thing. (Chap. XI, p. 1306; DPV X 368.)

Thus we understand the hermeneutical importance of the fiction of the Fils naturel, arranged and summoned throughout the Entretiens to think generally about representation. The opposition of salon and stage is in fact the fundamental framework. Indeed, we should speak of superposition rather than opposition: there is not a salon in one place and a stage in another, but a single space of representation, in Dorval's case, which is considered sometimes as salon, sometimes as stage.

In the first interview, Dorval begins by recalling how "society" is opposed to "theater", to very classically justify the three-unit rule:

In society, affairs last only by small incidents that would give truth to a novel, but take all the interest out of a dramatic work. There, our attention is divided over an infinite number of different objects; but in the theater, where only particular moments of real life are represented, we must be all at the same thing. (P. 1132; DPV X 86.)

On the surface, it's not the space that's in question, but the dramatic action, i.e. the content. Yet Diderot describes a double concentration: from the outside, the focus exerted on the scenic space; from the inside, the absorption into which the characters are plunged. The characters, themselves represented as concentrated and absorbed, represent this concentration of scenic space 4. Absorption thematizes focalization, placing in abyme on the stage that which conditions it, from the outside, as a geometrically ordered field of gaze, with a perspective and vanishing point. Narrative concentration and scopic concentration proceed from the same scenographic movement.

In contrast to this concentration, this absorption specific to the theater, is the dispersion, the scattering of "affairs" "in society": dead time and shared time are the lot of the real and presuppose an entirely different space, that, for example, of the promenade in which the Entretiens (but also the Paradox on the actor) are set. The focus on the object of the scene is then opposed by reverie and indeterminate thought.

But we mustn't forget that it's precisely the whole point of the Fils naturel and the Entretiens to subvert this opposition of society and theater, by having theater play out in the manner of a real social space: the scenic space deconstructed by the serious genre will therefore necessarily be worked by dissemination.

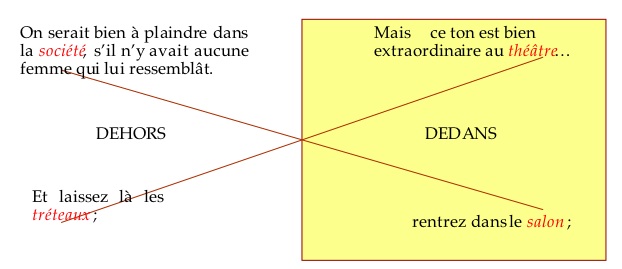

In the first interview, Moi criticizes Constance's declaration of love to Dorval as indecent. Dorval retorts:

"This is not Constance; and one would be much to be pitied in society, if there were no woman who resembled her.

"But this tone is quite extraordinary in the theater!..."

And leave the trestles there. Return to the salon, and agree that Constance's speech did not offend you when you heard it there 5." (P. 1135; DPV X 89-90.)

The chiasmus of inside and outside, a constitutive paradox of the scenic device

The opening opposition in the first interview, enunciated by Dorval himself, between society and theater, serves here as a starting point. What can happen in real life is forbidden in the theater by propriety. Reversing his own opposition, Dorval instructs Moi to leave the stage, to abandon the traditional rules of representation, and to take as his rule the exception constructed by the fiction of what he has experienced, hidden behind the salon curtain. A complex interplay of outside and inside takes place. To the vague exteriority of society, Moi initially opposed the circumscribed, focused space of the theater, with its rules. But Dorval asks him to abandon this standardized, artificial space, which becomes the general, vague external rule, and "enter the living room" - the real world, identified with the intimate, confined space in which this exceptional performance has taken place. In a veritable chiasmatic game, outside and inside have been inverted.

The aim is nothing less than to install a social outside in a scenic inside and, in so doing, to make a public, panoptic space of representation coincide with an intimate space of interrelation, stricken with invisibility.

The reversal is profoundly unstable and derives its authenticity value precisely from this instability. Thus, when Moi objects to Dorval's "le thé de la même scène" as an incongruous representation on the French stage, where this custom is not received, Moi cries out:

.

"But in the theater!"

It's not there. It is in the salon that my work must be judged... However, do not pass any of the places where you will believe that it sins against the custom of the theater... (P. 1135; DPV X 90.)

The reversal of outside and inside, public and intimate, stage and salon, is claimed by Dorval as an exception for this play, which is not one. At the same time, however, it's a question of establishing the modern conditions of performance, even beyond the serious genre: moi's "theatrical" point of view is thus both challenged and called upon, as the exception he has experienced is set to become the rule in terms of spectacle; the salon is to be the new stage. There is at least a paradox here, at most a logical impossibility that overlaps with that of representation itself, ideally thought of as unrepresentable.

Negative foundation of scenic space

The project to refound the scenic space is more clearly stated in the second interview. Dorval again protests:

And then, I bet you still see me on the French stage, in the theater.

"So you think your work wouldn't succeed in the theater?"

Hardly. You'd either have to prune the dialogue in a few places, or change the theatrical action and the stage.

"What do you call changing the scene?"

Remove anything that constricts an already cramped space. Having decorations 6. Pouvoir exécuter d'autres tableaux que ceux qu'on voit depuis cent ans; en un mot, transporter au théâtre le salon de Clairville, comme il est. (P. 1151; DPV X 110.)

The alternative in which Dorval places himself (either transform his play to adapt it to the theatrical stage as it is, or transform the stage to be able to perform his play on it) is a purely negative one: "eliminate the dialogue" on the one hand; "remove everything that constricts an already narrow space" on the other. The scenic space is founded, as it were, negatively, by the hollowing out of the performance space, a hollowing out that itself supplants a textual pruning 7.

Not only does the stage emerge as an autonomous space, distinct from the vague space of reality, only through the negative operation of emptying it, but its "decoration" is still a negative decoration: to "transport Clairville's salon, as it is, to the theater" is to deny the difference between sign and referent, the heterogeneity of representation and reality. This humanly empty space will be a visually ordinary space. Moi gives another example further on, borrowed from Landois's Sylvie 8, a dark tale of marital jealousy:

"The scene opens with a charming tableau. It is the interior of a room of which we see only the walls." (P. 1155; DPV X 115.)

Charming indeed! The scenic space organizes a veritable depression of the gaze, the antithesis of the dazzling prestiges of opera machinery 9. The scene says there's nothing to see. Through its banality, its neutrality, its very bareness (Diderot repeatedly cites as a model for the stage the bare cavern of Sophocles' Philoctète 10), the scenic space represents its profound nature and what's at stake, invisibility, the blinded interaction that must be made to be seen anyway, by transgressing a ban on the gaze that constitutes representation. Dorval describes the typical scene as follows:

I would only ask to change the face of the dramatic genre, a very extensive theater, where one showed, when the subject of a play required it, a large square with adjacent buildings, such as the peristile of a palace, the entrance to a temple, different places distributed in such a way that the spectator saw all the action, and that there was a part of it hidden for the actors. (P. 1152; DPV X 111.)

Dorval's description revives the antiquated model of the Serlian tragic scene, with its central town square and adjacent factories likely to host or signify concomitant actions 11. It's no longer just a question of the spectator seeing the scene without being seen by the actors. Between them, within the scenic space, the actors don't have to see everything. The scenic space organizes invisibility and materially figures the constitutive blindness of every character.

This invisibility, this blindness are the principles, the ferments of dissemination at work in the theatrical stage. For example, when Moi objects to the excessive length of the explanation scene between Constance and Dorval in Act IV 12, Dorval retorts:

Dorval's explanation scene in Act IV 12 is too long.

Ah, there you go again. It's been a long time since this happened to you. You see Constance and me on the edge of a plank, upright, looking at each other in profile, and alternately reciting the request and the response. But is this how it was in the living room? Sometimes we sat, sometimes upright. Sometimes we walked. Often we stood still, in no hurry to get to the end of a conversation in which we were both equally interested. What didn't she tell me? what didn't I answer her? (P. 1159; DPV X 121.)

Between what Moi sees and what actually happened in the salon, Dorval contrasts two dramaturgical conceptions. Purely discursive, the first is placeless: only "the request and the answer" count. The second, on the other hand, is based on place, on the salon where bodies move and take up positions. We move from a dramaturgy of speech to a dramaturgy of space. Speech ceases to be understood as discourse, as the unfolding of content, and becomes a shared interest, a "conversation". It tightens the intimacy of the space and, far from communicating a message to the spectator, becomes a sign that something intimate and publicly incommunicable is being communicated between the characters. "What didn't she tell me? What didn't I answer her? Forgetful of itself, this loose, scattered, wandering speech envelops the protagonists as they become, through its bath, lovers.

In this fusional exchange, Dorval and Constance don't look at each other. Each is absorbed in himself, blind to what surrounds him. The verbal bath is what unites them, in invisibility. Isn't the theme of the scene Dorval's melancholy - her solitude, her self-absorption - which Constance sets out to ward off by proposing a gentle, thoughtful liaison? There's no tragedy in this self-absorption, but rather the exposure of the most intimate aspect of the subject, that which cannot be seen. This decisive scene in the play is entirely organized in the beat between Constance's proposal and Dorval's melancholy withdrawal, between sensitive bonding and absorbed unbonding 13. A new bond is invented, a contagious relationship with others that Constance explicitly inscribes in the picture of a new society founded on "general benevolence" and the "feeling of universal beneficence" (pp. 1114-5; DPV X 65). The social bond establishes a new scenic space, where the confrontation of the other's gaze is replaced by the contact of bodies: "Dorval (takes Constance's hand, presses it between his own two, smiles at her with a touched air, and tells her)" (p. 1113; DPV X 64). Dorval's smile implies that the actors are looking at each other at this moment, but the didascalia says nothing about it: "takes", "presses", "touched", what counts here is sensitive contagion, a contagion that is no longer essentially visual.

Notes

In 1757, only one private theater performed Le Fils naturel for a very limited audience: it was the Duke of Ayen's theater in Saint-Germain. The Comédie Française wouldn't perform the play until 1771, and even then with very few performances. With a few exceptions, therefore, the play was not performed.

Faced with painting, this figure of infigurability materializes for the critic in the discordant detail of the body that the eye disarticulates. See chapter 2.

On this subject, see J. L. Haquette, "Le public et l'intime : réflexions sur le statut du visible dans Le Fils naturel et les Entretiens", Diderot, l'invention du drame, dir. M. Buffat, Klincksieck, 2000, pp. 65-69.

On this fundamental notion of absorption (absorption), see Michael Fried, La Place du spectateur, chap. I, "La primauté de l'absorbement", esp. pp. 62-63.

In the original edition of Fils naturel, which DPV reproduces, the names of the interlocutors, Dorval and Moi, are not mentioned at the lines. Moi's lines are enclosed in quotation marks.

"ornemens d'un théatre, qui servent à représenter le lieu où l'on suppose que se passe que l'action dramatique" (Enc., art. Décoration), decorations essentially consist of sets on sliding panels. In 1753, Marmontel was already lamenting their paucity in the theater: "The theater of Tragedy, where decencies must be much more rigorously observed than in that of opera, has neglected them too much in the decorations part. No matter how much the poet wants to transport the spectators to the scene of the action, what the eyes see becomes at every moment what the imagination paints. Cinna reports to Emilie on his conspiracy, in the same sallon where Augustus is about to deliberate; & in the first act of Brutus, two theatrical valets come to remove the altar of Mars to clear the stage. The lack of decorations leads to the impossibility of changes, & this limits the authors to the most rigorous unity of place; a troublesome rule which forbids them a great number of beautiful subjects, or obliges them to mutilate them." (Enc., supplement to art. Decoration).

Diderot here anticipates the reform of the Comte de Lauragais, who in April 1759 offered the Comédie française the sum of thirty thousand livres in exchange for the disappearance of spectators from the stage itself: "We have finally succeeded in banishing all spectators from the theater at the Comédie-Française, and relegating them to the room where they belong. This change was made during the closing of the show, and was paid for by M. le comte de Lauraguais. This operation will not only oblige the actors to decorate their theater more appropriately, but will also bring about a revolution in theatrical play. When actors are no longer constricted by spectators, they will no longer dare to line up in circles like puppets." (Correspondance littéraire, May 15, 1759, ed. Tourneux, t. IV, p. 111.) Until then, comedians had been selling seats in the performance space itself, at a very high price: there was no stage space as such, with actors and spectators literally intermingled on the trestles. The frank separation of stage and parterre, theater and society, thus follows very closely the publication of Fils naturel.

"Silvie, Tragédie Bourgeoise, en un Acte, en prose, avec un Prologue, par Landois, au Théâtre François, 1741." (Anecdotes dramatiques, II, 180.) The play was the first of its kind in France after Le Marchand de Londres by Lillo, performed in England in 1731. It was published by Prault fils in 1742, in-8°, 44 p. Critical edition as Sylvie ou le jaloux by Henry Carrington Lancaster, John Hopkins studies, vol. 48, Baltimore, 1954.

This depression of a theatrical space worked by negativity has a more distant historical origin: when the classical stage unified into a single performance space, unified by the linear perspective of the Italians, it had to do away with, or at least relegate to the background, the compartments of the Baroque stage, which enabled several scenes and several locations, interior and exterior, to be represented simultaneously. This relegation is very well described by Corneille in the Discourse of the Three Unities (1660): "Our jurisconsults admit fictions of law, and I would like, following their example, to establish fictions of theater to establish a theatrical place, which would be neither Cleopatra's apartment, nor Rodogune's in the play of that title, nor Phocas's, Léontine's, or Pulchérie's in Héraclius, but a room on which these various apartments open. " (GF, pp. 150-151. See also E. Henin, op. cit., pp. 302-307.) This notion of theatrical fiction is fundamental: in a way, the fiction of the Fils naturel, which frames the play proper, is a salon fiction symmetrical with the theatrical fiction promoted by Corneille, since it substitutes the reality of Clairville's salon for the unreality of the classical stage. Seemingly opposed to theatrical fiction, salon fiction completes the latter, collapsing the last spatial difference, of salon and stage.

P. 1137, DPV X 93; p. 1155, DPV X 116; p. 1180, DPV X 148. Philoctète was in vogue, as evidenced by the long article in the Correspondance littéraire, issue of March 1er, 1755. The article was prompted by the first performance of M. de Châteaubrun's Philoctète: "Be that as it may, this play has had the greatest success, and the most inconceivable for me. [...] To make Philoctète worthy of a theater that has had Corneilles and Racines, it would be necessary to translate Sophocles' play in all its simplicity, in all its sublime and majestic naiveté, and in prose, because our verses are too mannered not to kill a subject as serious as that; an undertaking of enormous difficulty, which would presuppose a prodigious head like that of the author of Clarisse" (Corr. litt., II, 503). New praise for Sophocles' Philoctète in the issue of 1er June 1757, in reference to Voltaire: "Is there a nation that has a play to put next to Philoctète? " (Corr. litt., III, 377.) Lessing will make Philoctète the central theatrical model for Laocoon, echoing Grimm's criticism of Châteaubrun (Laocoon, IV, 61).

On the genesis of classical scenic space from Vitruvian treatises and early Italian recreations of the ancient stage, see E. Hénin, op. cit., pp. 228-248. E. Hénin shows there the decisive importance of Sebastiano Serlio's treatise on perspective and his engravings (French trans., Paris, Barbé, 1545), which set a model for the theatrical stage halfway between the Vitruvian frons scenae, tripartite and without depth, and the bare, unified perspective stage that would later establish itself as the Italian stage (p. 232). See also the development on "renfondrements", which open up a secondary scene in French Baroque décor (p. 294-301).

Act IV, scene 3, p. 1111; DPV X 60.

"Abandoned almost at birth between the wilderness and society; when I opened my eyes, in order to recognize the ties that could bind me to men, scarcely did I find any remnants of them." (p. 1112; DPV X 61.)

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « La scène au salon : Le Fils naturel », L’Œil révolté, J. Chambon, 2007, chap. III, p. 241-255.

Diderot

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Diderot

Les Salons

L'institution des Salons

Peindre la scène : Diderot au Salon (année 2022)

Les Salons de Diderot, de l’ekphrasis au journal

Décrire l’image : Genèse de la critique d’art dans les Salons de Diderot

Le problème de la description dans les Salons de Diderot

La Russie de Leprince vue par Diderot

La jambe d’Hersé

De la figure à l’image

Les Essais sur la peinture

Atteinte et révolte : l'Antre de Platon

Les Salons de Diderot, ou la rhétorique détournée

Le technique contre l’idéal

Le prédicateur et le cadavre

Le commerce de la peinture dans les Salons de Diderot

Le modèle contre l'allégorie

Diderot, le goût de l’art

Peindre en philosophe

« Dans le moment qui précède l'explosion… »

Le goût de Diderot : une expérience du seuil

L'Œil révolté - La relation esthétique

S'agit-il d'une scène ? La Chaste Suzanne de Vanloo

Quand Diderot fait l'histoire d'une scène de genre

Diderot philosophe

Diderot, les premières années

Diderot, une pensée par l’image

Beauté aveugle et monstruosité sensible

La Lettre sur les sourds aux origines de la pensée

L’Encyclopédie, édition et subversion

Le décentrement matérialiste du champ des connaissances dans l’Encyclopédie

Le matérialisme biologique du Rêve de D'Alembert

Matérialisme et modélisation scientifique dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Incompréhensible et brutalité dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Discours du maître, image du bouffon, dispositif du dialogue

Du détachement à la révolte

Imagination chimique et poétique de l’après-texte

« Et l'auteur anonyme n'est pas un lâche… »

Histoire, procédure, vicissitude

Le temps comme refus de la refiguration

Sauver l'événement : Diderot, Ricœur, Derrida

Théâtre, roman, contes

La scène au salon : Le Fils naturel

Dispositif du Paradoxe

Dépréciation de la décoration : De la Poésie dramatique (1758)

Le Fils naturel, de la tragédie de l’inceste à l’imaginaire du continu

Parole, jouissance, révolte

La scène absente

Suzanne refuse de prononcer ses vœux

Gessner avec Diderot : les trois similitudes