A purported arbitrariness of narrative

One of the distinctive features of a certain Enlightenment novel is the interplay the narrator introduces between the conduct of the narrative and the narrative itself. He takes a malicious pleasure in denouncing the illusion that fiction usually entertains of its own reality, and recalls without restraint his prerogatives, which seem to allow him arbitrarily to elicit in the narrative one event rather than another, to prolong a situation or bring it to an end, to summon or dismiss a character.

In this respect, Jacques le fataliste is a model of the genre. Right at the start of the novel, when Jacques and his master have been joined on the road by a surgeon traveling on horseback with his companion in rump, and in the heat of a conversation about knee pain, the man has knocked the cotillion woman over the head with a grand gesture, the narrator takes the floor and thus taunts the reader

"What would this adventure become in my hands, if it took me in fancy to despair you! I'd give this woman importance; I'd make her the niece of a priest in the neighboring village; I'd stir up the peasants of that village; I'd prepare myself for fights and love affairs; for at last this peasant girl was beautiful under the linen. Jacques and his master had noticed; love didn't always wait for such a seductive opportunity. Why shouldn't Jacques fall in love a second time?" (P. 715 1.)

This passage is often cited as a proclamation of the arbitrariness of narrative. It highlights what might be called a narrative self-reflexivity: narration would here reveal, as it were, the mechanism of its production, would reveal the poetic mechanics of all narrative.

An imaginary disturbance: the absent scene

The exact content of this intervention by the narrator, however, merits examination. We would first like to show that it does not in fact reflect the narrative's narratological structure, but rather blurs it, or rather reveals its inanity. First, let's note that Diderot doesn't speak of the arbitrariness of narrative, but of fantaisie2 : fantasy here is not simply, in the modern sense of the word, the arbitrary, capricious, immotivated desire to upset the reader. Fantasy is first and foremost fantasiva, the idea, the image that appears, that offers itself to the mind, i.e. the very opposite of narrative mechanics : not an arrangement of words, not a combinatorial of technical solutions to textual amplificatio 3, but an absolutely non-verbal phenomenon, a virtual scene that shows itself, a scene that is not the actual continuation of the narrative, but its imaginary and at the same time foundational disruption, what I'll therefore call the absent scene 4.

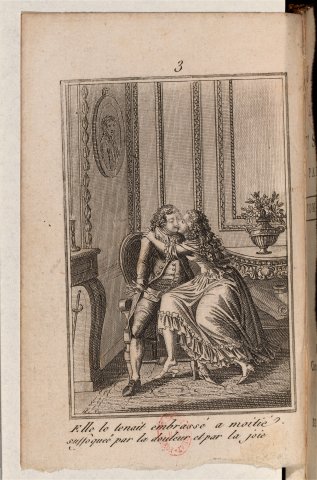

There is indeed a figurative dimension in the device that the narrator scaffolds at pleasure, virtually, before our eyes. But this figure is not rhetorical; it belongs to pictorial composition, with which the Diderot of the Salons had dabbled for a good ten years before composing Jacques. To give consistency to the absent scene, Diderot characterizes the figure of the upside-down woman: "I would give importance to this woman; I would make her the niece of a priest from the neighboring village; [...] for at last this peasant girl was beautiful under the linen."

The absent scene reverses the present situation of the narrative, this "fallen woman", "and the cotillions spilled on her head", so that, says Jacques, "you'd see your ass", and gives to see what comically disappeared in the embarrassment of linen where the surgeon's companion had disappeared 5. In place of the linen and the ass of a totally indeterminate sort of peasant 6, the absent scene characterizes a figure, "the niece of a parish priest from the neighboring village," and gives her to be seen: "for at last this peasant was beautiful under the linen."

This figure takes shape from the encounter in which it is inscribed. Firstly, a meeting with the peasants who have come to the aid of the fallen beauty: "I would rouse the peasants of this village; I would prepare myself for battles and love affairs"; then, a romantic encounter of the highest order: "Why shouldn't Jacques fall in love a second time?" This double encounter refers back to the classic organization of the pictorial scene, with its vague space that inscribes it in a reality, the village in the distance and the rushing peasants, and its restricted space that circumscribes and designates the theatrical site of the performance, on the trestles of this improvised scene, the meeting of Jacques and the surgeon's companion.

Narrative, fiction, structure

There is indeed a figurative organization of fiction here, but this figurability is not rhetorical: it's pictorial, which doesn't prevent it from insolently exhibiting its outrageously conventional and stereotyped character 7. No invention here, but the complacent repetition of storytelling codes: "je me prépareais des combats et des amours" refers to the two encounters in the absent scene, the fight with the rioted peasants and Jacques's second loves, but refers above all to the topical framework of epic narrative since the Renaissance, no longer the Virgilian arma virumque cano, I sing of arms and the hero, but Ariosto's Le donne, i cavallier, l'arme, gli amori, the ladies, the knights, the battles, the loves.

The intervention of the narrator of Jacques the Fatalist at the moment of the fall of the surgeon's companion thus reveals, through the play of self-reflexivity, three dimensions of the narrative: the narrative dimension is the one we're generally emphasizing here. The narrative links events together, and the narrator is free to summon them at will. But in addition to this narrative dimension, we've shown that there's also a fictional dimension: the story can only unfold on the basis of pre-existing figures, which the event, or the chance encounter, merely unveils. For there to be a narrative, the interesting figure of the neighboring village priest's niece must form a tableau upstream of the narrative: she alone can crystallize the double encounter that constitutes this virtual scene sketched out before us, and set in motion, for the narrative, the unfolding of a narrative. Finally, in contrast to the apparent arbitrariness of the narrative, the absent scene reveals the ultra-conventional structure of "combat and love", which places the narrative not in the indefinite unfolding of a free narrative, but in the extremely constrained framework of ritualized repetition. The structural dimension (constrained and repetitive 8) and the narrative dimension (arbitrary and digressive) are thus radically opposed to each other, and are only articulated to constitute the narrative device thanks to the intermediary dimension of fiction, which makes these opposites imaginatively coexist. These three constituent dimensions of any narrative device correspond to two types of self-reflexivity that can be distinguished a priori in the novel: narrative self-reflexivity, on the one hand, textual and referring to the polarity between narration and structure, between randomness and repetition; fictional self-reflexivity on the other, non-textual and opening onto the world that envelops the text and pre-exists it.

The lure of narrative self-reference

To hold to, to hold oneself: narrative and scenic constraints

Let's take up these distinctions by extending the investigation to the whole novel of Jacques le fataliste. The narrator's interruptions repeatedly underline the omnipotence of the one who produces the narrative, and sovereignly decides the nature and sequence of events. It is the verb tenir that most recurrently designates this sovereignty:

"You see, reader, that I am on a fine path, and that it would only be up to me to..." (p. 714)

"et il ne tiendrait qu'à moi que tout cela n'arriverait" (p. 721)

"You see, reader, how obliging I am; it would only be up to me to give a lash..." (p. 756)

"What does it matter if I raise a violent quarrel between these three characters?" (P. 786.)

"For myself I hold to nothing." (P. 794.)

"Reader, are you not afraid of seeing a renewal here of the scene at the inn where one shouted: Thou shalt go down; the other: I will not go down? What does it matter if I don't let you hear: I'll interrupt; you won't interrupt? It's certain that, for as little as I annoy Jacques or his master, there goes the quarrel; and if I engage it once, who knows how it will end?"(P. 888.)

He holds to me, what holds he, I hold to nothing: hold is said here in the sense of depending, and asserts the narrator's absolute sovereignty over the unfolding of the narrative 9. But tenir figures this dependency, this logical hierarchy, and through the figure reverses the meaning it appears to state. Tenir figures the link, from narrator to narration, a reversible link by which the narrator in turn finds himself subjugated: "and God knows the good and bad adventures brought on by that shot. Elle se tiennent ni plus ni moins que les chaînons d'une gourmette." (P. 713.) No arbitrariness possible to this narrative, whose necessity in the book written up there turns the apparent arbitrariness of the story, illusorily improvised before us 10.

So, when Jacques has camped out with the surgeons waiting at his hostess's house while he lies weighed down by his knee injury:

"What advantage would another not have drawn from these three surgeons, from their fourth-bottle conversation, from the multitude of their cures, marvelous ones, from Jacques's impatience, from the host's bad temper, from the talk of our country Esculapes around Jacques's knee, of their different opinions, one claiming that Jacques was dead if we didn't hurry up and cut off his leg, the other that we should extract the bullet and the portion of clothing that had followed it, and preserve the poor devil's leg. However, Jacques would have been seen sitting on his bed, looking at his leg in pity, and bidding it a final farewell, as one of our generals was seen between Dufouart and Louis. The third surgeon would have gobbled until a quarrel arose between them and invective was replaced by gestures.

I'll spare you all these things. I'll spare you all these things, which you'll find in novels, in old comedy and in society." (P. 723.)

The flow of the story is actually constrained by circumstances and characters. The hustle and bustle of the wine-swilling surgeons and the painting of Jacques contemplating his leg, which is threatening to be amputated, provide the ingredients for a conventional scene, be it novel, comedy or society: against the discursive logic of the conversation in the background, where amputation is the subject of unreal controversy, the leg in the foreground iconically and subversively opposes the concrete, painful evidence of its presence. The vague space of the table in the background is contrasted with the restricted space of the bed where Jacques sits.

The absent scene: a decoy

Precisely this scene, entirely constrained by the codes of representation, is present in Jacques le Fataliste only by default or in hollow, as an absent scene, as the scene we would have found there, at this moment in the text, if this text had been a novel. To establish the fictional contract, and the illusion on which this contract rests (the reader pretends to take the story he's reading as true), the narrator must posit what he's saying as not being fiction, and to do so deny the fictional nature of the fiction. The fictional contract rests entirely on this negation of fiction, that is, on its own negation 11. As a result, what the narrative presents as fiction, this scene that we would find in a novel but which it only gives in order to disassociate itself from it, this absent scene is not the novel's fiction, but its caricature, its conventional anticipation, a simple game of code, the mechanics of a narrative that involves no real stakes 12. Such a scene, purely fabricated, does not imply upstream of itself the presence of any world endowed with an autonomous existence of its own, of any fantasy capable of imposing, against the codes of narration, its own logic.

Narrative self-reference thus appears as a lure: the narrative mechanics it exposes are not the mechanics of the fiction on which the novel is built. What the novel designates as the novel, the code, the framework, is merely a mechanical modeling of the novel, designed to muddy the waters, to veil the devices that constitute the true basis of the fiction of Jacques le Fataliste. The arbitrariness of the narrative, like the conventions of the stage, are the red handkerchiefs of the narrative corrida, brandished with all the more conspicuous ostentation that the fictional reach, that the banderillas of the narrative are felt elsewhere.

The lure of narrative self-reference reveals at least one thing: narrative is not the end of storytelling. At most, it holds its visible elements, while the essential, the fiction, is woven elsewhere, in an enigmatic knowledge that pre-exists it.

The narrative impasse reveals fiction as world

This second narrative spring comes into its own when the narrative falls into an impasse, as when Jacques, a victim of his generosity, finds himself penniless to pay his doctor and buries himself in bed, refusing to eat:

"- Eat, eat, you'll pay no more and no less.

- I don't want to eat. - Good, it will be for my children and for me.

And having said that, she closes my curtains, calls her children and there they are, hurrying off with my sugar toast.

Reader, if I were to take a break here, and go back to the story of the one-shirted man, because he only had one body at a time, I'd like to know what you'd think? That I've got myself into a impasse à la Voltaire or vulgarly into a cul-de-sac, from which I don't know how to get out, and that I'm throwing myself into a tale made at pleasure, to save time and look for some way out of the one I've started. Well, reader, you are mistaken in every respect. I know how Jacques will get out of his distress, and what I'm about to tell you about Gousse, the man with only one shirt at a time, because he had only one body at a time, is not a tale at all." (P. 772.)

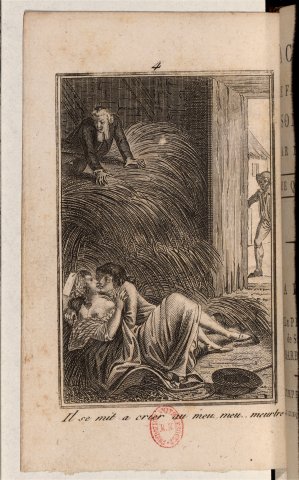

The narrative impasse ("si je faisais une pause"), is anticipated in Jacques' story by the closing of the bed curtains, which absents Jacques from the scene. The screen of curtains closed by the doctor plunges the performance space into invisibility: geometrically, from the scene of the narrative, Jacques behind his curtains becomes invisible; symbolically, because he is penniless, he ceases to count and disappears from the discursive game; imaginatively, the tasting of the sugar toast by the doctor's children is seen from an impossible vantage point, or in other words from a neantized eye, since the narrator, Jacques, entrenched behind the curtains of his bed, cannot see what he is describing.

The narrator then seems to assert the sovereign power of the narrative's arbitrariness, by starting an alternative narrative, Gousse's story. The narrator's intervention, and the self-reflexive game it introduces, do little to explode his demiurgic power, but rather, in a disquieting way, the reader's doubt and skepticism: the narrative is a decoy, not only the first, Jacques' story, which ends in a dead end, but the second, Gousse's story, which is there only to give the change. Just as the surgeon's companion's fall from her horse at the start of the novel led only to her ass being seen, so the curtains drawn over Jacques by the doctor lead to a dead end. "And then, reader, always tales of love" (p. 841): the ass is the end of all narration, i.e. the opposite of all figures, the blurring of all visibility.

Countering this narrative lure, Diderot nevertheless asserts his mastery, but on another level: "I know how Jacques will be pulled out of his distress, and what I'm going to tell you about Gousse, the man with only one shirt at a time, because he had only one body at a time, is not a tale at all." A knowledge of the story precedes its narrative form, and Gousse belongs to a reality that predates the tale before our eyes, a reality that has nothing to do with its conventions and artifacts. In both cases, a fictional (or real, for that matter) world pre-exists the narrative, which is no longer presented as a free improvisation or a combinatory of randomly linked events created on the fly, but as a possible, partial figuration of this pre-existing fiction. From the vague immensity of what "I know" to the restriction of the "tale" delivered to the reader, a remnant is lost, enigmatic and unfigured: this remnant of fiction that escapes the narrative is the absent scene, which this time is no longer the exhibited lure of narration, but the invisible matrix of narrative.

Fiction as world

This anteriority of fiction over narration is pleasantly figured in the following dialogue between Jacques and his master recounting the story of his love affairs. Jacques speaks:

"Aren't you in Miss Agathe's arms? - Yes. - Won't you find it comfortable there? - Very well. - Stay there. - Let me stay there, it pleases you to say. - At least until I know the story of Desglands' plaster." (P. 896.)

It's not simply a matter of recalling that, admittedly, the master is supposed to have actually been in Mlle Agathe's arms long before he tells Jacques about it. What Jacques jokingly reminds us through his interruption is that the narrator imagines what he's recounting before he utters the narration, and that he doesn't imagine it as an arrangement of words, but as a situation, a sensation, a scene. If there's an enjoyment of fiction, which Jacques is playing with here, it's that it's not simply paid for with words 13.

It's not customary to approach fiction in this way. A cautious, positive approach invites us to consider the text we have before us as the starting point for the narrative. The sublime process of artistic creation, upstream of the text, remains an unfathomable enigma, and analysis can only begin from the tangible documentary material constituted by the text. Fiction, i.e. the imaginary dimension of the narrative, will be understood as a product of the text, downstream from it, as what the reader, possibly staged in the text, elaborates as a hypothesis, after the fact 14. To give an account of fiction, the analyst will adopt the modest point of view, acceptable to all, of the reader who imagines the fiction from the text he or she is given to read. There can be no question of usurping the presumptuous position of the writer, who imagines the story before writing it, forging a world from which he extracts his narrative. This is because psychoanalysis, in treating the text as a symptom, claims not only to decipher the process of its creation, but also to restore the infigurable part of the fiction that motivated this narrative. This is more than just a lapse in taste; it is a sacrilege in which the very foundations of rhetorical knowledge are threatened.

Or this sacrilege is precisely that which the novel itself commits when it attempts self-reflexivity: exhibiting the process of its creation, the text claims to be a symptom; playing with deception and revelation, it intuitively implements that hermeneutic whose operation psychoanalysis has explicated, a hermeneutic for which the text ceases to be an assemblage of words and figures and functions as an interface opening onto a world situated upstream of it. The interruption of the narrative and the change of level in the diegesis 15 not only blur the boundaries between the real and the represented; through this blurring, they open up this new hermeneutic regime where signs become symptoms and discourse becomes tableau 16.

So it's not a question of choosing between two conceptions of fiction, creative fiction upstream of the text, before or during its composition, versus interpretive fiction downstream, during reading: when the novelist interpellates the reader, it's from this upstream that he claims his omnipotence, and we have to admit that the arrangement of words to which he miserably refers the reader is then nothing but empty fodder.

The dream as a symptom of metalepsis

At Diderot, the self-reflexive break is significantly represented by the dream. Thus, when Jacques returns from the pitchforks, at the sight of which his new horse has taken the bit:

"Jacques let his horse catch his breath, which of its own accord rode back down the mountain, up the pothole and placed Jacques back beside his master, who said to him: Ah! my friend, what a fright you've caused me! I thought you were dead... but you're dreaming; what are you dreaming 17?" (P. 743.)

Although, in narratological terminology, we must distinguish between the intradiegetic narrator that is Jacques and the extradiegetic narrator whose addresses to the reader we have so far studied, we are indeed dealing with the same phenomenon of metalepsis, i.e. the fusion of levels of representation: Jacques leaves his narrative to dream, beneath him in reality, about the meaning of this face-to-face encounter with the gallows, just as Diderot, the narrator, left his narrative to meditate, above him in metafiction, on the making of the narrative. The dream figures, symptomatizes this change of level, which is also a change of hermeneutic regime 18 :

"The Master. Devil, this is an unfortunate omen; but remember your doctrine. If it's written up there, you'll be hung, dear friend; and if it's not written up there, the horse will have lied about it. If this animal isn't inspired, he's prone to whims; you have to be careful..." (Ibid.)

As a figure in the narrative, the gallows should function as a sign; as an irruption of reality that randomly interrupts the narrative, the gallows makes no sense: but this nonsense is not insignificant, since it manifests, against fiction, the power of reality, a terrifying power since it evades all regulation by meaning and code. Through metalepsis, the gallows is placed at the intersection of narrative, as a system of signs, and reality, with its disquieting irruptions. Neither sign nor insignificant, the gibbet functions as a symptom, referring back for decoding to what "is written up there", that pre-existing knowledge of fiction, from which it may retrospectively make a sign or subsist as mere randomness 19.

Fiction as an interrogation of man's final ends

This self-reflexivity of narrative is not narrative, as it is not aimed at the unfolding of the narrative, but fictional, as it questions the knowledge and world that envelop the narrative and pre-exist it. We find the same reverie on meaning after the passage of Jacques' captain's funeral convoy, when he has resumed the story of his loves.

."Jacques. When you don't listen to the one who's speaking, it's because you're not thinking about anything, or you're thinking about something other than what he's saying: which of the two were you doing?

The Master. The latter. I was daydreaming about what one of the black servants following the funeral float was telling you, that your captain had been deprived, by the death of his friend, of the pleasure of fighting at least once a week. Did you understand anything about that? Jacques. Certainly.

The Master. It's a riddle to me that you'd force me to explain." (P. 749.)

This is not simply a narrative bifurcation, from the story of Jacques' knee injury, whose narrative is interrupted here, to the story of Jacques' captain and his friend, whose narrative will begin a few lines further on. Between two narrations, the master's reverie shifts the economy of the narrative from the linear unfolding of the story to a face-to-face encounter with the hearse, just as we were previously confronted with a face-to-face encounter with the pitchforks: as M. Bakhtin has shown, the economy of the narrative shifts from the linear unfolding of the story to the face-to-face encounter with the hearse. Bakhtin, the fundamentally dialogical economy of the novel, heir to Socratic dialogue and menippean satire, always ultimately boils down to a questioning of man's final ends 20. Jacques' knowledge, summoned here by his master, will certainly be translated, a few lines later, into the telling of the story of the captain and his friend. But, solicited by reverie, interrogated as an enigma in the face-to-face encounter with death, for an instant, in the fleeting duration of this stall between two stories, it far exceeds this narration. The time of reverie is the time of fictional self-reflexivity, in which the novel reflects on its creative process, i.e., the work of fiction upstream of the text that will ultimately preserve a trace, a glimpse of it. This process, this work, has to do with reverie and enigma, that is, with what resists and escapes figuration 21 : maintained as a space of invisibility underlying the narrative, visible only by default, as a blank in the representation, as a pause in the discursive flow, the knowledge of fiction, unlike the decoy scenes triggered by narrative self-reflexivity, is not a mechanical trompe-l'oeil.

Fiction and subversion

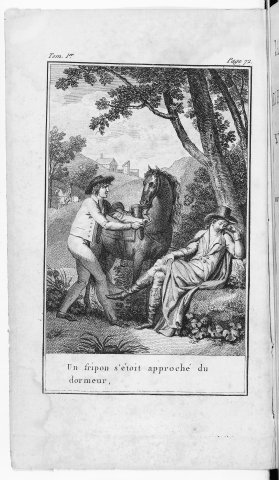

This knowledge is not a pure abstraction devoid of content, as evidenced by Jacques' reverie in front of his master's rediscovered horse:

"Jacques, then, lifting his huge hat and wandering his gaze into the distance, caught sight of a ploughman uselessly beating one of the two horses he had hitched to his plough. The horse, young and vigorous, had lain down in the furrow, and no matter how much the ploughman shook it by the bridle, begged it, caressed it, threatened it, swore at it, struck it, the animal remained motionless and stubbornly refused to get up.

Jacques, after dreaming for some time, came to the conclusion that the ploughman's horse was the only one of his kind. Jacques, after dreaming about this scene for some time, said to his master, whose attention it had also caught: Do you know, sir, what's going on here?

Master. And what do you want that is happening other than what I see?

Jacques. Can't you guess?

The Master. No. And what can you guess?

Jacques. I'm guessing that this silly, proud, lazy animal is a city dweller, who's proud of his first state as a saddle horse, despises the plough ; and to tell you everything, in a word, that this is your horse, the symbol of Jacques, and of so many other cowardly rascals like him, who have left the countryside to come and wear livery in the capital, and who would rather beg their bread in the streets, or die of hunger, than return to agriculture, the most useful and honorable of trades. " (P. 904.)

Jacques's reverie comes just as the master has finished Desglands's story and before he takes up that of his loves. From a narratological point of view, then, it once again marks a drop-out from the second to the first degree of the narrative, and even, we should say, from the third to the first, before the second is resumed, since Desglands' story is itself a digression in the story of the master's loves. In reality, all that counts for the reader is the metaleptic scrambling, i.e., the level dropout in representation, a dropout that disconnects the narrative routine for a time and lets us glimpse its beyond.

.This beyond manifests itself, once again, as a scene ("Jacques, after dreaming for some time of this scene"), but this time not as a hyper-coded scene such as one might contemplate in the genre painting of the time, but as a real scene, at once stubborn and brutal and, at first at least, totally enigmatic. This scene is seen only because Jacques has just raised "his enormous hat", defined a few lines earlier as "the dark shrine under which one of the best brains that ever existed consulted fate on great occasions". Jacques' meditation will reveal that the beaten horse is a "symbol of Jacques": the scene is therefore self-reflexive, reflecting back to Jacques the image of his condition. The beaten horse becomes a tableau for Jacques because he himself, discovering his hat, suddenly becomes a tableau in the reality with which he is confronted.

The reality of the story - in this case, the resistance of the striking horse, the obstinacy of the peasant seeking to plow an animal that is not draught animal and refuses this lowering of condition - is the fiction that envelops the narratives that intersect with it. The narration will knot the threads, making the horse the master's stolen horse, thus linking, making se tense, the scene of reality and the path of narration, of which the journey of Jacques and his master is the figure. But that's not the point: this scene, absent in fiction because it doesn't enter into any of the stories, except, and by a long shot, into that of the framework narrative, contains the knowledge of which all these stories are the reflection and constitute partial figurations: a horse is beaten as a child is beaten, Jacques in this case, who identifies with it as soon as he lowers his arms by taking off his hat. An atrocious scene, echoing the accents of Rameau's Neveu, of a social injustice that not only hurts men, but makes them pay for their intelligence with the price of their debasement.

I have distinguished two types of self-reflexivity in narrative. Narrative self-reflexivity is the most conspicuous. It's the one that calls out to the reader and exhibits the novelist's powers: Reader, it's only'up to me to... But the narrative mechanics that are then designated and demonstrated are nothing but a decoy: this caricature of textual mechanics has nothing to do with the reality of the narrative, which is not the product of arbitrary fantasy, but the constrained representation of a fictional world.

This world of fiction, which pre-exists and envelops the narrative, is reflected in the novel by a second type of self-reflexivity, fictional self-reflexivity. The reader is not necessarily challenged, but the levels of representation are blurred by the irruption of a reality that raises the question of meaning. The character then begins to dream, that is, to meditate, marking a suspense, a gap in the order of language. The questioning of the meaning symptomatic of encounters with reality (the pitchforks, the mysterious words of a black servant, the beaten horse) reveals the fiction of the story, which is not a collection of words, but a world marked by injury, a wounded world where the questioning of man's final ends is played out.

These two types of self-reflexivity, narrative and fictional, produce scenes whose distinctive feature is that they remain external to the narrative. Here's the scene I could sketch here, says narrative self-reflexivity; here's the scene that met and interrupted the narrative, says fictional self-reflexivity. I've named these scenes, scènes absentes. The first, ultra-coded, speaks of the mechanical laws of representation. Worrying or brutal, the second sweeps them away to reveal the sensitive origin of writing, the revolting pain of existing.

Notes

As for the term fantasy, which is the proper Diderotian term, it recurs several times. Jacques uses it to contrast it with the deterministic rationality of what is written up there: "It is that, for want of knowing what is written up there, [...] one follows one's fantasy which one calls reason, or one's reason which is often nothing but a dangerous fantasy which sometimes turns out well, sometimes badly." (P. 720.) Similarly, at the end of the novel: "And I'll stop, because I've told you all I know about these two characters. [...] I see, reader, that I'm making you angry; well, take up his tale where he left off, and continue it at your fantasy" (p. 916). Similarly, in Le Neveu de Rameau: "if you persist in the fantaisie of going to tell him the story of your amusements" (p. 636); "here's the text of my frequent soliloquies that you can paraphrase to your fantaisie" (p. 637). But fantaisie also refers to the very march of the world, in this formula that paraphrases Rabelais: "do your duty so quellement, always speak well of monsieur le prieur, and let the world go at your fantaisie" (p. 627).

References are given in Diderot, Œuvres, ed. L. Versini, tome II, Laffont, Bouquins.

Instead of absent scene, Maxime Abolgassemi uses, from a narratological perspective, the term "counterfiction", which he borrows from Robert Martin, Pour une logique du sens, Paris, PUF, 1983. See Maxime Abolgassemi, "La contrefiction dans Jacques le Fataliste", Poétique, n° 134, April 2003, pp. 223-237.

Sometimes the text gives the illusion that it's all about combinatorics: "choose the one that best suits the present circumstance" (p. 730). But the illusion is almost always immediately denounced: "and that in all combinations" (ibid.). "If you're not satisfied with what I'm revealing about Jacques' love affairs, reader, do better, I agree. Any way you slice it, I'm sure you'll end up like me." (P. 918.)

From a narratological perspective, the scene is a modality - particular, admittedly, but quite expected and listed - of narration. Narrative self-reflexivity will therefore reflect indifferently a succession of events, or the amplification of an event, making a scene.

Compare with Rameau's formula, "Un visage qu'on prendrait pour son antagoniste" (Le Neveu de Rameau, p. 626).

"A sort of peasant who followed them with a girl he carried in his rump."

Similarly, in the conduct of the narrative, the appearance of characters often gives rise to the pictorial decoding of their figure: "He was received with a visage where indignation was painted in all its force" (Mme de la Pommeraye receives the Marquis des Arcis after his marriage to a whore, p. 822); "At the approach of her husband, she read on his visage the fury that possessed him" (fury of the Marquis des Arcis facing his wife, whose identity he has just discovered, ibid.); "One showed the figure of despair, the other the figure of hardening" (mother and daughter facing the raging Marquis, p. 823); "At this singular allure Jacques deciphered it; and approaching his master's ear, he said to him: 'I wager this young man has worn a monk's habit'" (Jacques devant Richard, the Marquis des Arcis' secretary, p. 837). This decoding constitutes the zero degree of self-reflexivity: the narrator exhibits the code of representation as he performs it, so distancing is minimal in appearance. What is fundamental, however, is that it maintains the iconicity of the narrative, treated as a tableau, and irreducible by this means to an assemblage of words. Witness this more conspicuous self-reflexive play, but of the same nature: "Lecteur, j'avais oublié de vous peindre le site des trois personnages dont il s'agit ici" (description of the hostess-narratress and her listeners, Jacques and his master, at the moment of the narrative of the meeting of the Marquis des Arcis and Mlle d'Aisnon in the King's Garden, p. 806).

The narrative repeatedly insists on this repetition, this automaton mechanics: "What does it matter, as long as you speak and I listen? aren't those the two important points?" (p. 741); "Then, to continue, he took up his last sentence, as if he'd had the hiccups" (p. 754); "Reader, you're treating me like an automaton, that's not polite" (p. 760); "And then, reader, always tales of love; one, two, three, four tales of love that I've given you; three or four other tales of love that come back to you again: those are a lot of tales of love. It is true, on the other hand, that since we write for you, we must either do without your applause, or serve you to your taste, and that you have decided this for the love stories" (p. 841); "Pardon, mon maître, la machine était monté, et il fallait qu'elle goât jusqu'à la fin" (p. 899).

Similarly, in other words, "Reader, who would'prevent me from throwing the coachman, horses, carriage, masters and valets into a pothole here? If the pothole frightens you, who would'prevent me from bringing them safely into the city, where I would hook their carriage to another, in which I would enclose other drunken people?"(P. 895.)

Maxime Abolgassemi notes the illusory nature of this apparent "casualness" on the part of the narrator, but deduces from this that there is no longer any figure or metalepsis in what he calls counterfiction (art. cit., p. 229). We don't believe him: hold/se tenir, fantaisie-arbitraire/fantaisie-monstration, are metaleptic figures, but figures that contain their own disfiguration, dialectic figures. This fundamental phenomenon, which characterizes the conception and use of the word figure outside rhetoric, for example in painting and in Diderot's Salons, is never taken into account by narratology.

G. Genette, Métalepse, Seuil, 2004, p. 23.

Strangely, Maxime Abolgassemi denies this "passage" the quality of a "counterfictional approach", preferring to call it a "metanarrative commentary" (art. cit., p. 227). The logical difference he draws is undeniable, but isn't the powerful effect of the scene, in each case, the major effect of the text? Through it, commentary here becomes fiction, just as, through self-reflexive play, all counterfiction constitutes commentary.

Similarly, on the arrival of Jacques and his master at the Grand Cerf inn: "It was late; the city gate was closed, and they had been forced to stop in the suburb. There, I hear a commotion... - You hear! You weren't there; it's not about you. Yes, it is. Well, well, well! Jacques... his master... There's a terrible commotion. I see two men... - You don't see anything; it's not about you, you weren't there. - Yes, I was. There were two men at the table..." (p. 774).

It is on this point that our approach stands in radical opposition to the narratological approach, as developed, for example, by Maxime Abolgassemi in the article we cited earlier (art. cit., p. 225). If he defines "counterfiction" as "a sequence" that leads to "an absence of actualization", it is not to detect in it the trace of a world pre-existing the text, but to identify, from a given event in the text, a series of possible "causalities", a system of "inferences", a set of fictitious "hypotheses": counterfiction is an abstract logical game, of which the visual scene, or sight, is always at best only the outcome, which is not taken into account. This scene is never treated as a primary fiction, from which a narrative can unfold. Significantly, for M. Abolgassemi, counterfiction is not a scene, but a hypothesis.

This change of level is what narratology, after rhetoric, designates as metalepse. "The Metalepsis [...] consists in substituting the'indirect expression for the'direct expression, that is, in making one thing heard by another, which precedes, follows or accompanies it, is an adjunct to it, a circumstance of some kind, or finally is attached to it or relates to it in such a way as to recall it at once to the mind. [...] We can relate to the Metalepsis the trick by which a poet, a writer, is represented or represents himself as producing himself what he is, in essence, only narrating or describing. [...] We must also undoubtedly relate to the Métalepse [...] that turn [...] by which, in the heat of enthusiasm or sentiment, one suddenly abandons the role of narrator for that of master or sovereign arbiter, so that, instead of simply narrating a thing that is done or that is done, one commands, one orders that it be done" (Fontanier, Les Figures du discours, Flammarion, Champs, pp. 127-8.)

In other rhetorical terms, hypotyposis is the quintessential manifestation of metalepsis. "It's when, in descriptions, we paint the facts we're talking about as if what we're saying were actually before our eyes; we show, so to speak, what we're only recounting; we give, as it were, the original for the copy, the objects for the paintings." (Dumarsais, Des Tropes, art. Hypotypose, Flammarion, p. 133; Genette, Métalepse, pp. 10-11).

Compare with Le Neveu de Rameau: "What have you Rameau? you're dreaming. And what are you dreaming about?" (Rameau's soliloquy lamenting his lack of genius, p. 688.) And more distant in turn of phrase, but closer in meaning: "But you don't listen to me, what are you dreaming about?". Me. I dream of the inequality of your tone..." (p. 670; similarly, p. 643).

The dream is always associated, in Jacques, with an unhooking from the narrative: "When Jacques's master had taken a mood, Jacques would fall silent, start dreaming, and often only break the silence with a remark, linked in his mind, but as disjointed in conversation as the reading of a book from which a few leaves had been skipped" (p. 753).

Same ambiguity in the anecdote of the ring cut in two, where the ring has the same status as the gallows here. See p. 766.

Mikhail Bakhtin, La Poétique de Dostoievski, 1963, French trans., Seuil, 1976, pp. 154-186.

Thus, when Jacques, supposedly a virgin, finds himself in the grass alongside the buxom Dame Marguerite, the whole scene hinges on the impossibility of directly verbalizing the physical arousal of the sexual organs. The dream then serves as a verbal substitute for the infigurable sex: "Dame Marguerite, what's the matter? You're dreaming. Marguerite. Yes, I'm dreaming... I'm dreaming... I'm dreaming... As she uttered these I'm dreaming, her chest rose, her voice weakened, her limbs trembled, her eyes had closed, her mouth was ajar; she heaved a deep sigh; she fainted, and I pretended to believe she was dead" (p. 866).

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « La scène absente : autoréflexivité narrative et autoréflexivité fictionnelle dans Jacques de Fataliste », L’Assiette des fictions. Enquêtes sur l’autoréflexicité romanesque, dir. J. Herman, A. Paschoud, P. Pelckmans et F. Rosset, Louvain, Paris et Walpole, Peeters, 2010, p. 337-351.

Diderot

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Diderot

Les Salons

L'institution des Salons

Peindre la scène : Diderot au Salon (année 2022)

Les Salons de Diderot, de l’ekphrasis au journal

Décrire l’image : Genèse de la critique d’art dans les Salons de Diderot

Le problème de la description dans les Salons de Diderot

La Russie de Leprince vue par Diderot

La jambe d’Hersé

De la figure à l’image

Les Essais sur la peinture

Atteinte et révolte : l'Antre de Platon

Les Salons de Diderot, ou la rhétorique détournée

Le technique contre l’idéal

Le prédicateur et le cadavre

Le commerce de la peinture dans les Salons de Diderot

Le modèle contre l'allégorie

Diderot, le goût de l’art

Peindre en philosophe

« Dans le moment qui précède l'explosion… »

Le goût de Diderot : une expérience du seuil

L'Œil révolté - La relation esthétique

S'agit-il d'une scène ? La Chaste Suzanne de Vanloo

Quand Diderot fait l'histoire d'une scène de genre

Diderot philosophe

Diderot, les premières années

Diderot, une pensée par l’image

Beauté aveugle et monstruosité sensible

La Lettre sur les sourds aux origines de la pensée

L’Encyclopédie, édition et subversion

Le décentrement matérialiste du champ des connaissances dans l’Encyclopédie

Le matérialisme biologique du Rêve de D'Alembert

Matérialisme et modélisation scientifique dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Incompréhensible et brutalité dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Discours du maître, image du bouffon, dispositif du dialogue

Du détachement à la révolte

Imagination chimique et poétique de l’après-texte

« Et l'auteur anonyme n'est pas un lâche… »

Histoire, procédure, vicissitude

Le temps comme refus de la refiguration

Sauver l'événement : Diderot, Ricœur, Derrida

Théâtre, roman, contes

La scène au salon : Le Fils naturel

Dispositif du Paradoxe

Dépréciation de la décoration : De la Poésie dramatique (1758)

Le Fils naturel, de la tragédie de l’inceste à l’imaginaire du continu

Parole, jouissance, révolte

La scène absente

Suzanne refuse de prononcer ses vœux

Gessner avec Diderot : les trois similitudes