Diderot wasn't a writer who was also an art critic. These two terms, and the sociological fields they cover, "writer" on the one hand, "art critic" on the other, do not belong to his vocabulary. Diderot always defines himself in the Salons as a "poet", and the commentaries he offers, as "descriptions".

This means that, in the absence of the literary field whose genesis Pierre Bourdieu described in Les Règles de l'art1, the penman's ability to speak to the work of art is not self-evident. It is conditioned by the old Renaissance adage, ut pictura poesis erit, borrowed from Horace and, as it were, turned upside down from its original meaning: the poet, i.e. the man of the pen in general, can speak about painting, because painting is also the work of a poet; painting and poetry implement, in different media, the same creative process, the same ideal, the same idea. The painter's idea or the poet's idea, it's all one.

The poet is therefore fully competent to discuss the painter's idea, to render it textually, to evaluate and correct it. On the other hand, everything in painting that concerns execution on the support, what we call, in the masculine, the technique, eludes the poet. Technique is a trade skill, without genius, below that noble, ideal region where all the arts communicate.

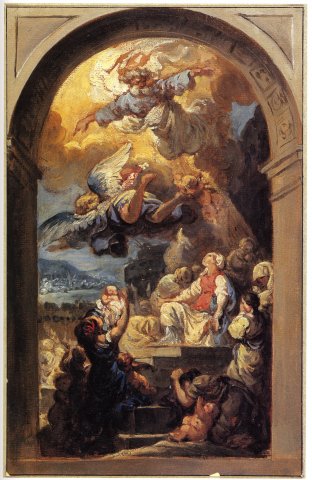

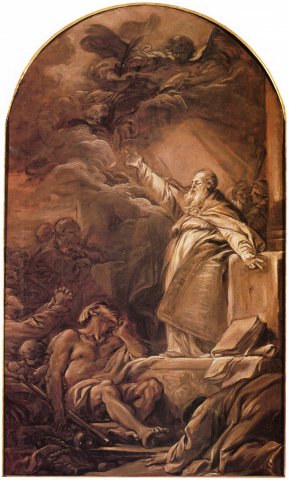

The opposition of the technical and the ideal asserts itself more and more strongly as we progress in our reading of Diderot's Salons, until it constitutes the structural foundation of the Salon of 1767. It is then embodied in the competition between the two most monumental paintings in the exhibition, Vien's Saint-Denis, which would be a work of pure technique, without ideal, and Doyen's Ardents, a work of pure ideal, without technique.

However, at the very moment when this structural polarity was being masterfully embodied, in the very visible space of the Salon, Diderot began to have doubts: might there not be a genius of technique, a genius that is properly pictorial? And is Doyen's ideal really a poetic, Homeric ideal? Neither the meta-level of the model, nor the infrastructure of the field, the eye then opens up the possibility of another relationship to the image, an aesthetic relationship.

I. The space of comparison at the Salon

This is the story of a duel.

When, in the autumn of 1767, we entered the square salon of the Louvre to visit the exhibition organized by the Royal Academy of Painting, we were struck right from the staircase, this immense staircase that occupied a quarter of the single exhibition room, by two immense paintings, identical in size and format, all high and arched, hung on the left wall. Diderot warns us right away: in the noisy throng of the Salon, where commentary was going strong, these two paintings were the big deal that divided the public:

"The public was divided between this painting by Vien, and the one by Doyen on the epidemic of the Ardents, and it's certain that they are two beautiful paintings; two great machines. I'll describe the first. The description of the other will be found at its rank." (DPV XVI 93; Ver 538.)

From the outset, the problem is posed: on the one hand, the hanging at the Salon and, as we shall see, the aesthetic bias taken by each of the two painters, for paintings destined to face each other at the church of Saint-Roch, demands comparison. On the other hand, the order of the paintings in the booklet, which is the order followed by Diderot in his comments, introduces a strong asymmetry: the Saint Denis by 51-year-old Professor Vien is numbered 15, i.e. among the paintings by the most prominent members of the Académie, just after the official paintings by Vanloo, former rector, and Hallé's royal commissions; the Ardents by 41-year-old Académie member Doyen is numbered 67, amid landscapes and genre scenes. Doyen is no stranger; he was admitted to the Académie in 1759 (when Vien was already a professor there), and has since been entrusted with important commissions, such as in 1765 the completion of the decoration of the chapelle Saint-Grégoire at Les Invalides on the death of his master Carle Vanloo. But this has nothing to do with the honors-filled career of Vien, who set out to rival Jouvenet by exhibiting La Piscine miraculeuse and three other large religious compositions at the Salon of 1759, who presented at the Salon of 1765 a Marc Aurèle destined for the Galerie de Choisy, and obtains for 1767, with the commission of Saint-Roch, two of the four large history compositions commissioned by Stanislas-Auguste2 for his Warsaw château through Mme Geoffrin, the great aesthetic-mundane affair of the moment.

Diderot marks the dissymmetry from the outset: "I will describe the first. The description of the other will be found at his rank." Personal commitment and full of reverence for the first ("je vais décrire"); casual deferral to later for the second ("on trouvera la description"). But Diderot is not a man to let honors and hierarchies impose him: this marked difference should make us alert; if Diderot poses it, it is to then play with it, possibly turning it around, but in a perhaps unexpected way.

At the Salon, in any case, the rivalry between the two painters rages on. Under the very fire of public criticism, in the heat of the debate that pits the Academician against the Professor, Doyen the colorist, the emulator of Rubens and his colorful tumults, has erected his scaffolding in the middle of the exhibition to resume his Ardents under the gaze of the Saint-Denis of his neo-classical adversary, supporter of the Greeks and accomplice of the Comte de Caylus.

"Doyen's and Vien's paintings are on display. Vien's has the most beautiful effect. Doyen's seems a little black; and I see a scaffold set up opposite, which tells me that he is retouching it." (DPV XVI 102.; Ver 543)

Doyen is in Vien's school and seeks to rival him. Moreover, although the two canvases were painted separately, in the respective studios of the two painters, it was on site at Saint-Roch, concurrently therefore, that they underwent the final retouching:

"Vien and Doyen retouched their paintings in place. I haven't seen them; but go to St Roch [...].

The need that Doyen and Vien felt to retouch their paintings in place should teach artists to provide themselves in the studio with the same exposure, the same lights, the same room they must occupy.

Vien lost less at St Roch than Doyen." (DPV XVI 275-276; Ver 660-661.)

Diderot didn't see the paintings at Saint-Roch before they were moved a few hundred yards from the church, to the Salon carré in the Louvre. But there, facing each other, on either side of the transept where they still stand today, they underwent the final adjustments, and above all Doyen, of whom we possess a whole series of modelli for Le Miracle des Ardents, was able to measure himself against Vien, who varied very little, as evidenced by the preparatory sketch from Montpellier, virtually identical to the final version.

In this regard, Diderot reports a dismissive remark by Pierre, a very official history painter of the same generation as Vien:

"You may say what you please, Mr. Chevalier Pierre. If this piece is only by a schoolboy, strong to the truth; what are you? Do you think we've forgotten the platitude of this Mercure and Aglaure that you kept redoing and that always had to be redone; and this mediocre Crucifixion3, still mediocre, though copied from one of Carracci's most sublime compositions. There are men of a very impudent and low jealousy. Mr Chevalier, acquire the right to be disdainful, and don't be.

But do you know, my friend, the reason for Greuze's rage, for Pierre's outburst against poor Doyen? It's because Michel, who runs the School, will soon vacate a position to which they all aspire. Doyen has been sufficiently avenged of his critics by public suffrage and the honorable testimony of his Academy, which on its roll named him assistant to professor." (DPV XVI 272-273; Ver 658.)

Diderot thus gradually unravels the web of intrigue at the Académie. Carle Vanloo having died in 1765, Louis-Michel Vanloo his nephew succeeded him as the lucrative and prestigious director of the École royale des élèves protégés. In 1767, he was sixty years old and there was already speculation about his succession: in fact, it was Vien who obtained the post on his death in 1771; Pierre, who hardly painted after 1763, nonetheless continued a brilliant official career: in 1770, he succeeded Boucher as first painter to the king and ended up as director of the Académie in 1778. As for Greuze, who criticized Doyen for plagiarizing Rubens (DPV XVI 275; Ver 660), in 1767 he was still only an approved painter, and the scandal of his reception by the Académie in 1769 as a painter of manners for a history painting would distance him from official institutions for good. Doyen did not become a professor until 1779.

There was no direct competition between Vien and Doyen: the former aimed for and obtained the top positions, while the latter was at most a nuisance. But this is where the very special institution of the Salon comes into play, where the cursus honorum of painters, if not directly submitted to the public's vote, at least confronts and exposes itself to the public during the exhibition period. In the space of the Salon carré, facing the test of public judgment, Vien and Doyen stand side by side, working solely for "the glory of the nation". It's no longer career and advancement that count, but "the progress and duration of art", "public instruction and amusement": value alone counts, and it doesn't wait for the number of years.

"How many paintings would have remained for years in the shadow of the studio, had they not been exhibited4? A particular individual goes to the Salon, strolling through his idleness and his boredom, where he acquires or recognizes a taste for painting. Another who has a taste for it, and had only gone there to find a quarter of an hour of amusement, leaves a sum of two thousand écus. A mediocre artist announces himself in an instant to the whole town as a skilled man." (DPV XVI 59.; Ver 519.)

Diderot finds the Roman accent in these lines of the preamble: the mediocritas of the artist ("such a mediocre artist") is not a mediocrity of value, but of condition. The obscure artist, whom no one recommends or protects, reveals himself to the whole City, that is, Paris or Rome, to the whole world.

This competition of value, Vien and Doyen's duel provides a dazzling example, and first and foremost by the space of representation it brings into play. We're not simply dealing here with two numbers from the libretto, but with two paintings placed side by side for comparison, halfway along a journey that began in the studios, then face to face at Saint-Roch, and will end in this face to face encounter. In front of these moving tableaux, the audience too circulates: it promotes its idleness, it finds amusement. Finally, daylight operates, on the canvas this time, a third circulation, which Diderot underlines in his commentary on Saint Denis :

"My friend, when you have paintings to judge, go and see them at daybreak. It's a very critical moment. If there are holes, the fading will make them felt. If there is flickering, it will become all the stronger. If the harmony is complete, it will remain." (DPV XVI 102; Ver 543.)

The address to the friend Grimm ("Mon ami, lorsque vous aurez...") betrays personal experience: Diderot didn't just pass in front of the canvas. He especially returned in the late afternoon, when the refraction of light on the canvas, as it weakens, reveals holes. At the end of the commentary on the Ardents, it's no longer just a question of a privileged hour; it's a whole timetable that falls into place:

"Go and see Doyen's painting, in the evening, in summer; and see it from a distance. Go and see Vien's, in the morning in the same season, and see it from near or far, as you please. Stay there until nightfall, and you will see the degradation of all the parts follow exactly the degradation of natural light, and its whole scene fade like the scene of the universe, when the star that lit it has disappeared. Twilight is born in his composition, as it is in nature." (DPV XVI 277; Ver 661.)

Did Diderot really follow the play of light on Vien's Saint Denis all day into the night? It's doubtful. Rather, the image allows him to superimpose two gradations, one, of composition, which regulates the color transitions between "all the parts" of the canvas, the other, "of natural light", which measures the passage of time. The painting's internal composition emerges from the double circulation of the walking spectator in front of it and the light that declines on it.

The purpose of this superimposition is to identify two scenes, the story scene composed by Vien ("his whole scene"), and "the scene of the universe": the theatricality of the canvas is the theatricality of the world itself, while the fickle eye of the viewer alights on the painting like the light, and understands its "degradation" as it produces it.

II. Scenography of the Saint-Roch church

This oceanic identification of the viewer with the dying light, of the canvas he is looking at with the world around him, is part of a new aesthetic of the sublime that will find numerous philosophical developments, from Kant to Derrida. The sublime undoes the frame: it is no longer the space of the canvas that delimits a composition whose meaning is produced by the arrangement of its parts. On the contrary, the measure of the canvas opens up to the immoderation of the world, the arrangement of the figures in the scene - to the dissemination of the infigurable in the world.

.But this deconstruction operated by the sublime at the same time returns to the structure it undoes. The theatricality of the stage, at the moment when it decays, appears as the henceforth universal measure from which to experience dissemination, the light that leaves, the canvas that dissolves into the world it was supposed, at a distance, to represent.

The vast renovation project at Saint-Roch church, carried out since the arrival of Abbé Jean-Baptiste Marduel as parish priest in 1749, dramatically reflects this evolution and contradiction.

Saint-Roch was the parish church of a fashionable district, where writers, artists, wealthy financiers and a few aristocrats from illustrious families rubbed shoulders with the common people. Madame Lalive de Jully, who died of smallpox, was buried in Saint-Roch church in 1752; she was the wife of the financier painted by Greuze with a harp, and exhibited at the Salon of 1759; President Hénault, Mme du Deffand's lover and Voltaire's friend before sinking into devotion, was buried in Saint-Roch in 1770; Helvétius, fermier général, contributor to the Encyclopédie, philosopher whom Diderot read with pen in hand and whose Réfutation he undertook, is also buried at Saint-Roch in 17715 ; Madame Geoffrin, who held a Salon a stone's throw from the church on rue Saint-Honoré, and mediated between the Polish king Stanislas-Auguste and the Académie royale de peinture for a major commission for the Warsaw palace, exhibited at the 1767 Salon6, was buried at Saint-Roch in 1777. Finally, Diderot lived on rue Taranne and belonged to the parish of Saint-Sulpice. But when he was close to death, the Nouvelles ecclésiastiques recall that he was moved across the Seine so that, at the time of his death, he was in the parish of Saint-Roch7 : this is where he was buried, in the chapelle de la Vierge, at the back of the church, on August 1er, 1784.

Everything opposes the parish of Saint-Roch to the very devout parish of Saint-Sulpice, on the other side of the Seine. Not only is it not easy here, near the Louvre of painters and the French Theatre, to attract flocks more sensitive to the glamour of secular performance than to the oratorical rigors of preaching, but Marduel's predecessor, a Jansenist, was at loggerheads with the ecclesiastical authorities. The Abbot therefore had to fight on both fronts, and set about doing so with an ambitious church reconstruction program. The unglamorous perimeter of the Saint-Roch church, all in length with a very narrow facade on the rue Saint-Honoré, hardly lent itself to architectural emphasis.

Advised by the Comte de Caylus, Abbé Marduel first turned to the decorator and architect Jean Nicolas Servandoni (1695-1766), whose two overdoors and two small paintings of ancient ruins Diderot comments on in the Salon de 1765, with this preamble:

"Great machinist, great architect, good painter, sublime decorator, there is none of these talents that has not earned him immense sums, yet he has nothing and will never have anything. The king, the nation and the public have given up the idea of saving him from misery; they love him as much for the debts he has as for those he would make." (DPV XIV 124; Ver 349.)

The prodigal Servandoni lives from, for and in show business. He began his career in Rome, the world capital of ephemeral architecture. Theatrical decoration was his specialty. However, from 1729 onwards, he worked for Saint-Sulpice: first the chapelle de la Vierge, then the front mass of the building, the façade, and even worked on a project for a square in front of the church.

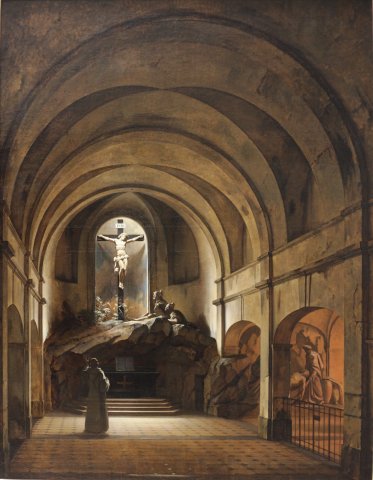

But Servandoni was too expensive. A competition was launched in 1753, which the sculptor Falconet, a friend of Diderot, won. Gradually, the painter Pierre, the architects Coustou and above all Boullée, the sculptors Slodtz and Challe, and the painter Demachy joined the project. The creative team assembled by Abbé Marduel designed a theological and dramatic itinerary for this long church: from the chapelle de la Vierge, where Falconet casts a stucco glory symbolizing the operation of the Holy Spirit at the Annunciation, we move on to the chapelle de la Communion, where Slodtz redecorates the altar with a tabernacle and two angels, then to the chapelle du Calvaire, added to the rear of the building, and conceived by Boullée as a chaos of rocks from which emerged the Christ on the Cross legated in 1685 by sculptor Michel Anguier. Falconet scripted this crucifix: beneath it, he installed a penitent Magdalene, to its right, two downtrodden Roman soldiers, in front, the satanic serpent writhing in the rocks. In the background, Demachy paints an Apocalyptic sky. Through this series of three interlocking circular chapels, the three great mysteries of the Christian religion follow one another: that of the Incarnation, that of Communion and that of the Resurrection.

.This first phase of work ordered by Marduel was completed in 1760, when the church was solemnly inaugurated. On this occasion, Diderot wrote a rather mixed review for the Correspondance littéraire. But beyond his criticisms and counter-proposals, Diderot perfectly grasps what the director of the Saint-Roch parish's ambition is:

"If I had had the idea of executing a calvary, I would have embraced a large space, and I would have wanted to show a large scene, like Rubens' Elevation of the Cross, or Volaterra's Crucifying8 [...]

. An edifice such as I imagine it, with all the pathos that could be introduced, would make more conversions than all the sermons of a Lenten season." (DPV XIII 176.)

The church is no longer a temple of the word, but a conversion device that aims to channel, capture and exploit idle wandering, turning idle strolling into aesthetic circulation, then into an initiatory journey. This capture of the stroll proceeds on exactly the same principle as that described by Diderot about the Salon in the preamble to the Salon de 1767 : the stage ensnares erratic, random circulation and, just as the church converts the onlooker to the sublime of mystical contemplation, so the Salon, from Sunday strollers, manufactures a public, and with this public the taste, then the glory of the nation.

However, the long church of Saint-Roch suffers from the virtual absence of a transept. To remedy this, curé Marduel launched a trompe l'oeil project at the end of each of the short wings of the transept. On August 5, 1763, he sent a placet to the Dauphin to replace the side doors with two altars dedicated respectively to Saint Denis, who introduced Christianity to Gaul, and Saint Geneviève, patron saint of Paris. Boullée was entrusted with the architectural project. The choice of saints is significant: in 1765, de Belloy had triumphantly played his Siège de Calais9. He did it again in 1770 with Gaston et Bayard10. National tragedy is fashionable and gives rise to grand public scenographies, where the people fraternize with the aristocracy in the stirring memory of the glorious pages of French history. Both the Predication of Saint Denis and the celebration of Saint Genevieve's miracles to save Paris are part of this vein, and intend to recapture its emotional effectiveness ad majorem Dei gloriam.

We don't know how or by whom the painters were chosen. But it seems that Doyen began work early on the project, first on Sainte Geneviève interceding with God to stop the'invasion of the Huns11. Although the subject has nothing to do with the one that will ultimately be chosen, Doyen has already set up the essential setup: Geneviève is very much alive here, we're in 451; Doyen sets her up on a terrace very similar to what will become in Le Miracle des Ardents the plague hospital forecourt. But in the final scene, set in 1129, Geneviève appears in the sky, in place of God in the early version, while the earthly Geneviève of 1760 is replaced by a Parisian woman. While the identity of the characters changes, the architectural fabric, the cloud, the gestures and the arrangement of the figures remain the same, right down to the child brandished in the face of Heaven. Around 1765-1766, the final subject seems to have been decided, as evidenced by the drawing preserved in the Musée Bonnat in Bayonne, where the staircase is revealed, which will later disappear, obscuring, according to Diderot, the intelligence of the factory. Several modelli then follow, culminating in the grisaille in the Carnavalet museum, where the dying mother appears for the first time in her definitive position, treated in foreshortened form, with her head towards the back and no longer forwards: but as early as the 1760 sketch, a mother and her toppled child were in the lower right, opposed in shadow to the brandished child, raised towards the light. The feet emerging from the sewer, bottom right, would constitute the final transformation of this painting with its eventful genesis.

For the Saint Denis, it seems that it was first entrusted to Doyen, then rather quickly to Deshays: witness the ochre cameo sketch preserved in Nîmes. Deshays belonged to the same neo-baroque aesthetic movement as Doyen, so it's clear today that the interplay or emulation between the two schools of painting was not at all intended by the project's initiators. It was the premature death of the young Deshays in 1765 that forced Abbé Marduel's team, pressed for time, to turn to an experienced painter likely to complete the work quickly: the very official Vien was far removed in every respect from an atheistic Falconet, an ebullient Doyen and a visionary Boullée, all three younger than himself.

It is therefore a chain of largely unforeseeable circumstances (Doyen's inability to carry out the double commission, followed by Deshays's untimely death) that will trigger this duel between the two painters and the two paintings, from which Diderot draws a decisive articulation in his aesthetic thinking, the articulation between what he designates as the faire, or the technical, in which Vien is a master, and the ideal, the poetic idea, which the young and awkward Doyen was able to demonstrate. Circumstances, the contingency of places, the circulation of paintings, of men, of light, gave us a glimpse of this articulation: the visual device became an intellectual device.

III. Descriptive dissemination and linear modeling: the Saint Denis

device.This is what the text is all about. Diderot describes what he sees: "I will describe the first. One will find the description of the other at its rank." (DPV XVI 93; Ver 538.) But it's important to understand what the notion of description implies for an Enlightenment philosopher, torn between the Jansenist tradition of Port-Royal and the empiricist explorations coming out of England12. The Description article in the Encyclopédie echoes this tug-of-war. In it, Abbé Mallet first recalls the epistemological framework laid down by Arnaud and Nicole: description is opposed to definition; unlike definition, which synthetically defines its object, description enumerates its attributes, necessarily incomplete, circumstantial, approximate. These attributes, these superficial images, these fragmentary appearances that it accumulates, failing to reach the substantial core of its object, arouse distrust and disapproval. But Abbé Mallet's article is followed by an addition by Chevalier de Jaucourt who, referring to Addison, evokes on the contrary the pleasure of description, and the fullness of aesthetic enjoyment it brings.

It is necessary to get rid of both the ekphrasis antique and the narratological conception of description in order to understand what is at play in Diderotian description: first, Diderot allows himself to be invaded by this incompleteness of attributes, of figures, which disseminates the object instead of restoring it, which accumulates fragments for want of being able to produce a totality.

Then it's a matter of reversing this descriptive dissemination, of re-establishing, from these fragments, the unity of a definition: vision is reversed into intellection; from the arrangement of figures, we move on to a critique of composition. In this movement of reversal, which I have called aesthetic relationship, "the path of composition" (p. 95/539), "a path, a line that passes through the summits of masses or groups" (p. 269/656), the "connecting line" (ibid.), "true line, ideal model of beauty" (p. 70/525) constitutes a rather difficult interface to grasp, for this line begins by being a physical line that links together the figures in the painting; then, gathering together what the description has disseminated, it proposes a modeling of it, and it thus ends up constituting an ideal model, i.e., an abstract definition of what is represented. The line is apprehended, revealed first in its technical dimension, as the clarity of an arrangement, the evidence of a disposition; but this disposition cannot ultimately be reduced to the artist's doing; it is also and above all ideal, revealing the guiding idea, the poetic invention of the painter.

Or the whole beginning of the development devoted to St Denis preaching the faith in France aims, under the pretext of clearing up the painting's composition, to establish this line. The starting point, however, is rather a tangled web13. The description only apparently enumerates a succession of distinct elements that could be spotted, discriminated on the canvas: the temple, the apostle, his close disciples, his more distant audience.

"On the right, it's an architectural fabrication, the facade of an ancient temple, with its platform at the front. Above a few steps leading up to this platform, towards the temple entrance, we see the Apostle of the Gauls preaching. Standing behind him are some of his disciples or proselytes. At his feet, turning from the apostle's right, to the left of the picture, a little in the background, kneeling, sitting, crouching, four women, one weeping, the second listening, the third meditating, the fourth looking on with joy." (DPV XVI 94; Ver 538.)

The elements of the description first manifest themselves as a constellation around Saint Denis. There is no succession, declination or variation. The façade of the temple is not, as we might expect, the starting point at the top right of a line that, crossing the painting, would allow us to read it like a text. Diderot's starting point is not the façade, but the entire factory, that is to say, he specifies, the façade and its platform at the front. The factory serves as a showcase for the preacher, enveloping him and setting up the overall infrastructure of a stage around him, with a backdrop, the façade, and trestles, the platform. With the stage infrastructure in place, the Diderotian eye enters, not in the direction of the description (from right to left and top to bottom, it seems), but as one enters the temple, as St. Denis's listeners, on the canvas, access the spectacle he is giving them: "Above some steps that lead to this platform, we see the apostle of the Gauls preaching": the eye ascends here, starting from the opposite point on the canvas, bottom left. We don't see Denis preaching, the overall subject of the canvas, but Denis preaching, i.e. a figure in act, the fragment of an action which, at this stage of the description, is not yet ordered.

From this figure, then, the constellation is ordered, through a series of circumstantial complements that do not yet federate any real main proposition: "behind him", "at his feet"; then "behind these women". The complements don't complete any verb, but an adverb in place of a main proposition, "Standing" twice ("Standing behind him, some of his disciples"; "standing, right at the back, three old men"), then a series of state participles ("kneeling, sitting, crouching"). This syntagmatic disarticulation is characteristic of descriptive dissemination. Here, the preacher's action is reflected in a first, close circle of listeners, who react in different ways. Vien implements, in pure academic orthodoxy, the logic of the figure theorized by Le Brun, which echoes the verbal, discursive content of the history scene (here, the content of the preaching) in the range of reactions it elicits on the faces of its spectators14. Supplanting a discourse by nature impossible to represent by image, the expressions of the figures, in their very variety, roughly encircle its content: the taxonomy of the figures provides the description of what cannot be defined; the range, the dissemination of the figures takes the place of the discourse that the image cannot directly represent.

We can see from this that description is not the transposition of an image into a text: Vien works in description in the same way as Diderot. On the contrary, description consists in passing through the image to achieve representation, whether on canvas or in a text. This passage through the image begins with an experience of dissemination, which is not only a spatial dispersion of figures, but also a syntactic deconstruction, where the verb, in its function of organization, of syntagmatic federation, is reached.

From this descriptive taxonomy of reactions, however, a line will gradually emerge. First, it's a movement that the eye implements, not as an a priori discipline of the gaze, but, in the erratic circulation on the canvas, as a spawning that recurs more often, as a moment that gradually takes shape: "turning from the apostle's right to the left of the painting", then "continuing to turn in the same direction", "passing the same expression". These participles have no clearly assigned subject: strictly speaking, grammatically speaking, it's the characters in the painting, the verbless subjects of a nominal principal, who continue to turn, then pass on the expression of their reaction. But in terms of meaning, we understand that this is the journey that Diderot's eye makes, that it is this eye, and perhaps ours with it, that turns and turns, that operates on the canvas this spawning by which expression decomposes and recomposes, the figure unravels and remakes itself.

Descriptive dissemination confuses the external (Diderot's, the reader's) and internal (Saint Denis's listeners, the painter painting these listeners) spectator eye in the same spawning.

The scale is the primary form of the line:

"Continuing to turn in the same direction, a crowd of listeners men, women, children, seated, standing, prostrate, crouching, kneeling, passing the same expression through all its different shades, from uncertainty that hesitates, to persuasion that admires; from attention that weighs, to astonishment that is troubled; from compunction that is tenderized, to repentance that grieves" (DPV XVI 94; Ver 539).

Diderot will return again and again to this anamorphic game, whose different figures are merely the diffraction, the decomposition of a single mobility, which is not only that of a face taking on different expressions, but, even more essentially, of a soul going through all the trials of sensibility. Thus, in the Paradox on the actor,

"Garrick passes his head between the two leaves of a door, and, in the interval of four to five seconds his face passes successively from mad joy to moderate joy; from this joy to tranquillity; from tranquillity to surprise ; from surprise to astonishment; from astonishment to sadness; from sadness to despondency; from despondency to fright; from fright to horror; from horror to despair, and from the latter to the former. Could his soul have experienced all these sensations and performed, in concert with his face, this kind of scale?"(DPV XX 73; Ver 1394.)

Garrick's scale is a passage, a spawning, a sensitive circulation: to the circulation of spectators in front of the canvas responds this internal circulation in which the spectator's eye and the figure's expression jointly participate. This conjunction of circulations overflows the framework of representation, prepares the new aesthetic economy of the sublime, manifests, against discourse and its definitions, the positivity of descriptive energy, the logic of the device.

.Diderot then moves on to describe the characters in the foreground, i.e. the listeners in the second circle, who don't touch Saint Denis, who aren't part of his close guard. Then it's the turn of the third circle, the furthest away, with its allegorical celestial figures: Religion at the top left, and the angel it dispatches to bring the apostle the crown of martyrdom that awaits him. In the end, Diderot's reading was eccentric, starting from the core of the scene, from the protagonist figure of Saint Denis preaching, and successively traversing the ever-widening circles on which the preaching reverberates. The description does not follow the line of the composition, but on the contrary lays the groundwork for a construction, a retrospective composition, of which the last group of figures stated, Religion with its angel, will in fact constitute the starting point of the path, of the line:

"Here, then, is the path of this composition, Religion, the angel, the saint, the women at his feet, the listeners in the background, those on the left also in the background, the two large female figures standing, the old man reclining at their feet, and the two figures, one male and one female seen from the back and placed quite to the front, this path descending gently and winding broadly from Religion to the back of the composition on the left, where it folds back to form a kind of enclosure around the saint, at a distance, which stops at the woman placed in front, with her arms pointing towards the saint, and uncovers the entire interior expanse of the scene" (DPV XVI 95 ; Ver 539).

The line gathers the figures, arranges the space, gives meaning to the geometrical organization of the scene. The line reverses descriptive dissemination into a global perspective; the line is still succession and already device. Diderot borrows this line from Hogarth, whose The Analysis of Beauty he read for the Salon of 1765. It is from Hogarth that Diderot borrows the anamorphoses of Hercules and Antinous, in the digression to the Servandoni article (DPV XIV125-9; Ver 350-2). But Hogarth's distinction between the line of beauty and the line of grace is based on stylistic reasoning, an essentially technical differentiation. By identifying this line with the Platonic idea, in the preamble to the Salon de 1767, Diderot has completely changed the data and stakes of the problem. There aren't different kinds of line: the line is made or not made, and when it is made, in retrospect, the line crystallizes the device.

What's essential here in Diderot's description is "a kind of enclosure" that the line sets up, virtually, all around the preaching apostle and the stage, the platform from which he performs his speech. This enclosure is the fourth wall, the theory of which Diderot has just given in Discourse on Dramatic Poetry (1758) :

"Spectators are but ignorant witnesses to the thing. [...]

So whether you're composing or performing, don't think of the spectator either as if he didn't exist. Imagine a large wall on the edge of the theater, separating you from the audience. Play as if the canvas never rose. (Chap. XI, "De l'intérêt", DPV X 368 and 373; Ver 1306 and 1310.)

Painting abymes on the surface of the canvas this essential spring, in theater, of the scenic device. The initial indistinction between Diderot's eye and the eye of Saint Denis's listeners is only possible thanks to this mise en abyme, which differentiates, in the space of the painting, on the one hand the scene itself, formed by the apostle and his immediate entourage, evolving on the clearly delineated surface of a "platform", on the other hand, around this platform, a vague space that is still a space of representation and already designates the off-stage from which this representation is observed, is delineated in the real as spectacle.

The line then no longer connects the various figures of the composition, but delimits this fundamental boundary from which the game, the scenic device, is established, between the vague space, the real from which the scene is viewed, and the restricted space, where it is played out, at the limit of the unrepresentable: what is played out here on stage is the discourse of Saint Denis, a discourse that the image, mute by nature, can only indirectly give voice to.

However, despite the categorical injunction of the Discourse on Dramatic Poetry, this boundary in painting is always interrupted: it is through its interruption that our eye gains access to the scene proper, painting thus signifying to us on the one hand the interdict with which the image is struck, and on the other the necessity of transgressing this interdict. Diderot uses the verb "to interrupt" twice in the same paragraph:

."around the saint, a kind of enclosure that interrupts at the woman placed on the front"

"the indiscreet old men interrupting the saint, conversing among themselves and disputing apart" (DPV XVI 95; Ver 539.)

The spatial interruption figures and anticipates the discursive interruption. Placed too far forward in front of the temple steps, projected towards the saint in the expansive opening of her arms, the "woman placed at the front" emerges from her spectatorial reserve; she echoes the action of the discourse, turning it back towards the preacher who looks at her. Their eyes meet, and the scene crystallizes from this intersection. We enter the scene via this path, this woman standing in the axis of the steps through which Diderot leads us. Through her, the mimetic gap abolishes itself for a moment; she is the visual clutch of the scene, the metaphor of our eye on the canvas.

"It is said that the woman with outstretched arms has her right arm too short, that she belutes and that we do not feel the shortcut." (DPV XVI 97; Ver 540.)

Beluter15 is an old Rabelaisian verb that designates, metaphorically, sexual enjoyment. Our eye, placed there at the bottom of the composition, at the point where the invisible enclosure of the scene is interrupted so that we can penetrate it, our eye therefore, through this penetration, belutes. And it does so in the expansive gesture of arms open, outstretched, spread, and in the threat of a disquieting foreshortening, a "right arm too short", whose "foreshortening you can't feel". The transgression of the scenic fourth wall thus manifests itself as the dual, contradictory experience of jouissance and castration16.

This self-reflexive arrangement of the scene on canvas, with its implied division of space into a vague and a restricted space, is a general feature of the classical painted scene, which Diderot doesn't always point to explicitly, but on which his descriptive strategy always relies, at least implicitly. Sometimes, he makes spectacular use of it, as when confronted with Hubert Robert's Cuisine italienne17:

"Let's enter this Kitchen: [...] From this doorstep, I see that this place is square and that to show its interior, the wall on the left has been knocked down. I walk on the debris of this wall and advance." (DPV XVI 354; Ver 712.)

The eye doesn't just cross a threshold; it makes a geometrically impossible journey, mentally turning an interior into an exterior. Aesthetic pleasure arises from this reversal, from this virtual exercise of the border. At the center of the canvas, the stage itself is not delimited by any material separation, barrier, curtain or glass pane. Hubert Robert establishes the line, the limit to be crossed for the eye by the mere differentiation of light and shadow:

"This pyramid of light18 which is so well discerned in all places that are lit only by it and which seems to be included between darkness below and beyond it, is superiorly imitated. We are in shadow, we see all shadow around us; then the eye, meeting the luminous pyramid where it discerns an infinity of corpuscles agitated in vortices, crosses it, re-enters shadow, and finds shadowed bodies. How does this happen? Because light is not suspended between me and the canvas. (DPV XVI 356; Ver 713.)

There's a back-and-forth from shadow to light, an exchange and knotting in this virtual circulation.

IV. Triviality and revolt: the political horizon of art

In the Cuisine italienne, this circulation seems purely formal, and the enjoyment that the eye derives from it experiences dissemination ("an infinity of corpuscles agitated into whirlpools") only on a physical, optical level, which engages a priori no ideological reflection, no social discourse, no symbolic stakes: the revolt of the eye caught in the aesthetic relationship is a formal revolt devoid of content. Diderot, however, immediately puts it in abyme in a dialogue from Horace's Satires where Dave's admiration for the daubed street signs is contrasted with that of his master in front of a painting by the famous Pausias:

"When a painting by Pausias holds you motionless and stupid with admiration, are you less foolish than Dave arrested with surprise before a sign smeared with sanguine or charcoal, the struggle and outstretched hock of Fulvius, Rutuba or Placidejanus." (DPV XVI 357; Ver 714.)

The master's stupor is worth the valet's, Dave suggests, revolted. On the level of discourse, Diderot takes the master's side against the slave: "This Dave is the image of the multitude." In terms of device, the slave's revolt is what the eye's revolt triggered: a trivial reversal of perspective, a volte-face of reality, a transgressive, unseemly irruption. The aesthetic relationship passes through this experience of triviality, which overturns the relationship between the viewer and the viewed, between the spectator and the canvas.

But beyond the formal structure that emerges in this face-to-face encounter with Hubert Robert's Cuisine italienne, it is the very content of the representation that is played out as revolting representation. From the very first comparison of Vien's Saint Denis and Doyen's Ardents, Diderot highlighted the carnivalesque triviality of their competition:

"All the qualities that one of these artists lacks, the other has; there reigns here the most beautiful harmony of color, a peace, a silence, that charms. It's all the secret magic of art, unadorned, unsearched, effortless. It's a praise we can't refuse Vien; but when we turn our eyes on Doyen, whom we see dark, vigorous, ebullient and hot, we have to admit that in St Denis's Preaching, everything is highlighted only by a superiorly understood weakness; a weakness that Doyen's strength brings out; but a harmonious weakness that in turn brings out all the discordance of its antagonist. They are two great athletes who pull off a coup fourré." (DPV XVI 97; Ver 540.)

The polarity that Diderot establishes from Doyen's ebullient vigor to Vien's "harmonious weakness" is in fact the same polarity that confronts Dave admiring his daubed sign to his master mute with ecstasy before Pausias's sublime painting. It is not, therefore, simply a matter of coincidence, linked to the mere chance of commissions and the situation that polarizes the Salon space around these two stylistically violently contrasting paintings, even though they are identical in size and purpose. What Diderot is highlighting here is the very pulsation of the gaze, which structures itself from the spawning of vigor to harmony, from weakness to ebullition, in a Salon space that holds at once the arena where "two great athletes" measure themselves and the fair where dirty tricks are played.

This polarity isn't purely stylistic either: the respective efficiencies are directly linked to the subjects represented. The weakness of Saint Denis is the weakness of a predication, i.e. a composition entirely structured by language. Its order, its technical harmony, are commanded by the old classical logic of the figure, which from the figures of the speech delivered by the saint, the irrepresentable heart of the representation, is reflected in the figures of the spectators variously touched by him. On the contrary, the disordered vigor of the Ardents is identified with the convulsion of sick bodies projected in the face of Heaven. No language here: with her arms open, outstretched like Vien's "belute" spectator, the Parisienne doesn't deploy the eloquence of articulate speech, but carries this convulsion, which St. Genevieve herself doesn't strictly speaking receive, but transmits. The Ardents are innervated by a convulsion that communicates itself, that makes a tableau visually, outside language: the emotional charge of corpses replaces the exhausted fire of preaching. From the Saint Denis to the Ardents, painting has shifted paradigm: in the former, the logic of the figure is exhausted; in the latter, the convulsive horror of the body rises.

This extenuation of figures constitutes Diderot's main criticism of Vien:

"Notice, through the greatest intelligence of art, that it is without ideal, without verve, without poetry, without movement, without incident, without interest. This is not a popular assembly; it's a family, the same family. This is not a nation to which a new religion has been brought; it's a converted nation. What, then, is it that there were no magistrates, priests or educated citizens in this region? what do I see of women and children? and what else of women and children? It's like St Roch on a Sunday." (DPV XVI 99; Ver 541.)

No preaching without a popular assembly, no aesthetics of the figure without the politics of discourse. To implement the springs of theatrical effectiveness, the preacher's discourse must confront its contradiction, dialogize itself, arouse the popular convulsion of a revolt:

"Serious magistrates, had they been there, would have listened and weighed what the new doctrine had in line with or contrary to public tranquility. I see them standing attentively, eyebrows lowered, their heads and chins resting on their hands. Priests, whose gods would have been threatened, if there had been any, I would have seen them furious, biting their lips in rage. Educated citizens, such as you and I, had there been any, would have shaken their heads in disdain, and said to each other from one side of the stage to the other, other platitudes no better than ours." (Continued from previous.)

Here we see Diderot's true critical work. Diderot's description of the paintings does more than simply inscribe them in an aesthetic relationship. The spawning of the eye, the to-and-fro it institutes from viewer to canvas, constitutes a political scene: the invention of the modern gaze, the gaze of the revolted eye, is inseparable from this pre-revolutionary rediscovery of public space.

Notes

Pierre Bourdieu, Les Règles de l'art. Genèse et structure du champ littéraire, Seuil, 1992.

Stanislas II Augustus has been King of Poland since 1764.

Lapsus for the Descente de croix by Pierre de la cathédrale Saint-Louis de Versailles, exhibited at the Salon of 1761, of which Diderot had then written: "your Christ, with his livid, rotten head, is a drowning man who has been in St Clou's nets for two weeks at least. [...] Isn't your Descent from the Cross an imitation of Carracci's, which is in the Palais-Royal, and which you know well? [...] Know, my friend Pierre, that one must not copy or copy better, and in whatever way one does, one must not disparage one's models." (DPV XIII 224, Ver 206.)

The question obviously doesn't arise for the Saint-Denis and the Ardents, which are commissions, but for artists' spontaneous creations: the Salon undeniably played a role in stimulating the art market.

See the Correspondance générale d'Helvétius, Voltaire foundation, 2000, tome 3, letter 678, January 1772, p. 393.

This order included the following paintings: La Continence de Scipion and César face à la statue d'Alexandre, by Vien; La Tête de Pompée présentée à César, by Lagrenée; Scilurus roi des Scythes, by Hallé

On this subject, see Jean Sgard, "Diderot vu par les Nouvelles ecclésiastiques", Recherches sur Diderot et sur l'Encyclopédie, n°25, 1998.

Volaterra: read Daniele da Volterra. Diderot is more likely thinking of his fresco of the Deposition of the Cross, at the Trinité-des-Monts, one of Rome's French churches.

See the article in the Correspondance littéraire of March 15, 1765 recounting the performance on the 12th: "Le mardi 12 mars, on a représenté la tragédie du Siège de Calais, gratis, pour le peuple. Mmes les poissardes de la Halle occupied the first boxes. [...] During the intermissions, Mlle Clairon presented drinks to this illustrious company, who applauded all the actors and all the tirades of the tragedy. [...] M. le duc de Duras, M. le duc de Fronsac, M. le maréchal duc de Biron attended this performance."

See the venomous article of March 15, 1770 on M. de Belloy's "antechamber patriotism": "He also believes himself, in the best faith in the world, the inventor of the national tragedy. And why shouldn't he? He's been told so many times!"

Of this first stage of his work, predating Boullée's project, we have two traces, a drawing whose current location is unknown and a sketch preserved in the Louvre, which we can relate to an article in L'Année littéraire dated October 28, 1759.

S. Lojkine, L'Œil révolté, J. Chambon, 2007, pp. 89-98, and "Le problème de la description dans les Salons de Diderot", Diderot studies, XXX, 2008, pp. 53-72.

The bric-a-brac of Saint Denis is therefore not clearly differentiated, at least initially, from the effect of general dislocation that characterizes Le Miracle des ardents.

Charles Le Brun, "Sur l'expression des passions", 1668. The commentary on Poussin's Paysage avec l'homme tué par un serpent, also known as Les Effets de la terreur, played an important role in the theorization of the figure, not only as an alteration by passion of a neutral ideal figure (Le Brun), but also as a mobile inscription in a range of reactions to a given event. Following in Le Brun's footsteps, Félibien analyzes the figure in terms of expression ("when the fear of evil joins the aversion one has for an unpleasant subject, it is certain that the expression is much stronger", VIe entretien, t. III, 1679, p. 215). Diderot adds the meta-level of device: "All the incidents of Poussin's landscape are linked by a common idea, though isolated, distributed on different planes and separated by great intervals." (DPV XVI 400; Ver 743.)

Diderot's autograph manuscript carries "belute", according to Rabelais' spelling, which Grimm and later copies correct to "blute". Trévoux's dictionary gives only the technical definition of the word: "Bluter. v. a. Séparer la farine d'avec le son, en la passant par le bluteau." In concrete terms, this means using a sort of weeder to forage through flour placed on a sieve (or bluteau) to remove any remaining bran. The manipulation is described in the 69th short story of the Heptameron, with an obvious saucy connotation. In Rabelais, beluter is sometimes taken to mean copulating. In the Tiers Livre, Panurge exclaims to Pantagruel: "Je me donne à travers tous les Diables, comme un coup de boulle à travers un jeu de quilles ou comme un coup de canon à travers un bataillon de gens d'epied: guare Diables qui vouldra, en cas que autant de foys je ne belute ma femme future la première nuyct de mes nopces." (Chap. XI, Pochothèque, p. 615.) As for the position of the woman Diderot describes, it's certainly not that of a woman busy sifting flour!

In Marguerite de Navarre, the husband is caught by his wife bluter dressed as a woman: the maid he thought he was seducing has persuaded him to put her sarreau on his head (Livre de poche, p. 655).

The painting is kept at the National Museum in Warsaw.

The pyramid of light refers to Alberti's visual pyramid (pyramis visiva, see De pictura, I, 12). The pyramid of light puts the visual pyramid in a kind of abyss, since here the tip of the pyramid (cuspis pyramidis) does not merge with the viewer's point of view, "from which painters understand that everything can be seen more accurately" (unde omnia rectius concerni intelligunt). Instead, the eye intersects a pyramid controlled by a transverse light source: the pyramid of light represents the visual pyramid, i.e. the conditions of representation within representation itself.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Le prédicateur et le cadavre : Vien et Doyen côte à côte au Salon de 1767 », Cahiers de l’Association internationale des études françaises, mai 2010, n°62, p. 151-172

Diderot

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Diderot

Les Salons

L'institution des Salons

Peindre la scène : Diderot au Salon (année 2022)

Les Salons de Diderot, de l’ekphrasis au journal

Décrire l’image : Genèse de la critique d’art dans les Salons de Diderot

Le problème de la description dans les Salons de Diderot

La Russie de Leprince vue par Diderot

La jambe d’Hersé

De la figure à l’image

Les Essais sur la peinture

Atteinte et révolte : l'Antre de Platon

Les Salons de Diderot, ou la rhétorique détournée

Le technique contre l’idéal

Le prédicateur et le cadavre

Le commerce de la peinture dans les Salons de Diderot

Le modèle contre l'allégorie

Diderot, le goût de l’art

Peindre en philosophe

« Dans le moment qui précède l'explosion… »

Le goût de Diderot : une expérience du seuil

L'Œil révolté - La relation esthétique

S'agit-il d'une scène ? La Chaste Suzanne de Vanloo

Quand Diderot fait l'histoire d'une scène de genre

Diderot philosophe

Diderot, les premières années

Diderot, une pensée par l’image

Beauté aveugle et monstruosité sensible

La Lettre sur les sourds aux origines de la pensée

L’Encyclopédie, édition et subversion

Le décentrement matérialiste du champ des connaissances dans l’Encyclopédie

Le matérialisme biologique du Rêve de D'Alembert

Matérialisme et modélisation scientifique dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Incompréhensible et brutalité dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Discours du maître, image du bouffon, dispositif du dialogue

Du détachement à la révolte

Imagination chimique et poétique de l’après-texte

« Et l'auteur anonyme n'est pas un lâche… »

Histoire, procédure, vicissitude

Le temps comme refus de la refiguration

Sauver l'événement : Diderot, Ricœur, Derrida

Théâtre, roman, contes

La scène au salon : Le Fils naturel

Dispositif du Paradoxe

Dépréciation de la décoration : De la Poésie dramatique (1758)

Le Fils naturel, de la tragédie de l’inceste à l’imaginaire du continu

Parole, jouissance, révolte

La scène absente

Suzanne refuse de prononcer ses vœux

Gessner avec Diderot : les trois similitudes