[p.393]

GREUZE.

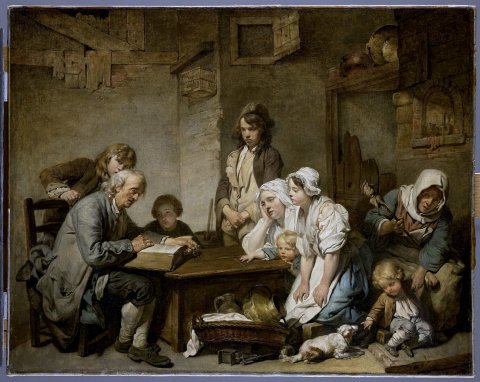

That Greuze really is my man. Forgetting for a moment his little compositions, which will provide me with pleasant things [p.394] to say to him, I come straight to his painting of Piété filiale, which might better be entitled: De la récompense de la bonne éducation donnée.

First of all, the genre appeals to me. It's moral painting. What, then, has not the brush been devoted enough and too long to debauchery and vice? Shouldn't we be pleased to see it finally contributing, along with dramatic poetry, to touching us, instructing us, correcting us and inviting us to virtue? Courage, my friend Greuze! Make morality in painting, and always do so. When you leave this life, there won't be a single one of your compositions that you won't remember with pleasure. Why weren't you next to that young girl who looked at the head of your Paralytic, and cried out with charming vivacity: Ah! my God, how he touches me; but if I look at him again, I think I'll cry; and why wasn't that young girl mine1! I would have recognized her by that movement. When I saw this eloquent and pathetic old man, I felt, like her, my soul soften and tears ready to fall from my eyes.

The painting of the Piété filiale is four feet six inches wide, by three feet high.

The main character, the one who occupies the middle of the scene, and who fixes the attention, is a paralytic old man, lying in his armchair, his head resting on a bolster, and his feet on a stool. He is dressed. His ailing legs are wrapped in a blanket. He is surrounded by his children and grandchildren, most of them eager to serve him. His beautiful head is of such a touching character; he seems so sensitive to the services rendered to him; he has so much difficulty in speaking, his voice is so weak, his looks so tender, [p.395] his complexion so pale, that one must be without bowels not to feel them stir.

To her right, one of her daughters is busy raising her head and bolster.

In front of him, on the same side, his son-in-law comes to present him with food. This son-in-law listens to what his father-in-law is saying, and looks quite touched.

To the left on the other side, a young boy brings him a drink. You have to see the pain and the whole face of this one. His pain isn't just on his face; it's in his legs, it's everywhere.

From behind the old man's armchair emerges a small child's head. He steps forward; he'd also like to hear his grandpa, see him and serve him; children are unofficial2. You can see his little fingers on the top of the chair.

An older one is at his feet, arranging the blanket.

In front of him, a quite young one has slipped between him and his son-in-law, and presents him with a goldfinch. How he holds the bird! How he offers it! He thinks it will cure grandpa.

Farther on, to the old man's right, is his married daughter. She happily listens to what her father is saying to her husband. She is sitting on a stool; her head rests on her hand. She has the Scriptures on her lap. She has suspended the reading she was doing to the gentleman.

Beside the girl is her mother and the paralytic's wife. She is also seated, on a straw chair. She was sewing up a shirt. I'm sure she's hard of hearing. She has stopped her work, she moves her head sideways to hear.

On the same side, at the very end of the painting, a servant who was at her duties, is also lending an ear.

Everything is reported to the main character, and what we're doing in the present moment and what we were doing in the previous moment.

[p.396] There isn't a single thing in the background that doesn't recall the care we take of the old man. It's a large sheet hanging on a rope, drying. This sheet is very well imagined both for the subject of the painting, and for the effect of the art. One suspects that the painter did not fail to paint it broadly.

Everyone here has precisely the degree of interest appropriate to age and character. The number of characters gathered in a rather small space is quite large; yet they are there without confusion, for this master excels above all in ordering his scene. The color of the flesh is true. Fabrics are well cared for. There is no hindrance to movement. Everyone is at their best. The youngest children are cheerful, because they're not yet at the age where you feel3. Commiseration announces itself strongly in the largest. The son-in-law seems the most touched, because it's to him that the patient addresses his speeches and looks. The married daughter seems to listen with pleasure rather than pain. Interest is, if not extinguished, at least almost insensible in the old mother; and this is quite in keeping with nature. Jam proximus ardet Ucalegon4. She can no longer promise herself any consolation other than the same tenderness from her children, for a time that is not far5. And then, the age that hardens the fibers, dries up the soul.

There are those who say that the paralytic is too inverted, and that it is impossible to eat in this position. He doesn't eat, he talks, and we're ready to lift his head.

[p.397] That6 it was for his daughter to present him with food, and for his son-in-law to raise his head and bolster, because the one requires skill, and the other strength. This observation is not as well-founded as it first appears. The painter wanted his paralytic to receive marked help from the person from whom he had the least right to expect it. This justifies the good choice he made for his daughter; it's the real cause of the tenderness in her face, in her gaze and in the speech he gives her. To move this character would have been to change the subject of the painting. To put the daughter in the son-in-law's place would have been to overturn the entire composition: there would have been four female heads in a row, and the enfilade of all these heads would have been unbearable.

They also say that this attention of all the characters is unnatural; that some should have been occupied with the good man, and the others left to their particular functions; that the scene would have been simpler and truer, and that this is how the thing happened, that they are sure of it.... These people faciunt ut nimis intelligendo nihil intelligant7. The moment they ask for is a common, uninteresting moment; the one the painter has chosen, is particular. By chance it happened that day that it was his son-in-law who brought him food, and the good man touched showed him his gratitude in a manner so lively, so penetrating that it suspended the occupations and fixed the attention of the whole family.

The old man is still said to be moribund and to have the face of an agonized man... Doctor Gatti says that these critics have never seen sick people, and that this one has well over three years to live.

That his married daughter, who suspends reading, lacks expression or doesn't have the expression she should have... I kind of agree.

[p.398]That the arms of this otherwise charming figure are stiff, dry, badly painted and lacking in detail... Oh! for that, nothing could be truer.

That the bolster is brand new, and that it would be more natural if it had already been used... That may be.

That this artist is without fertility; and that all the heads in this scene are the same as those in his Engagement painting, and those in his Engagement the same as those in his Farmer reading to his children... Agreed; but what if the painter intended it that way... what if he followed the same family history?

That... And may a thousand devils take away the critics and me all first! This painting is beautiful and very-beautiful, and woe betide anyone who can consider it for a moment in cold blood! the character of the old man is unique; the character of the son-in-law, unique; the child who brings a drink, unique. The old woman, unique. Whichever way you look at it, you'll be enchanted. The background, the blankets, the clothes are of the finest finish; and then, this man draws like an angel. His color is beautiful and strong, though not yet Chardin's. Once again, this painting is beautiful, or it never was. So it draws spectators in droves; you can't get near it. One sees it with transport, and when one sees it again, one finds that one was right to be transported by it.

It would be quite surprising if this artist didn't excel. He has wit and sensitivity; he is enthusiastic about his art; he studies endlessly. He spares neither care nor expense to find the models he needs. If he meets a head that strikes him, he'll gladly get down on the knees of the head's wearer to lure him into his studio. He is ceaselessly observant, in the streets, in churches, in markets, in shows, [p.399] in walks, in public assemblies. If he meditates on a subject, he is obsessed with it, followed everywhere. His very character is affected. He takes on that of his painting; he is brusque, gentle, insinuating, caustic, gallant, sad, cheerful, cold, hot, serious or mad, depending on the thing he is projecting.

Besides the genius of his art, which we won't deny him, we can still see that he is witty in the choice and appropriateness of accessories. In the painting of the Paysan qui lit l'Écriture sainte à sa famille, he had placed in a corner on the ground a small child who, to relieve his boredom, was making the horns of a dog. In his Engagement, he had brought a hen with her entire brood. In this one, he has placed next to the boy bringing his crippled father a drink, a large dog standing with her nose up in the air, and her pups suckling straight up; not to mention the sheet he has stretched out on a rope and which forms the background of his painting.

He was criticized for painting a little gray; he has corrected himself well for this defect. Whatever people say, Greuze is my painter.

Greuze is my painter.

I don't like his portrait of the Duc de Chartres. It's cold and graceless.

I don't like his portrait of the Duc de Chartres.

I don't like his portrait of Mademoiselle. It's gray, and this child is suffering. Yet there are some charming details in this one, like the little dog, etc.

Mr. de Lupé's is harsh.

Mademoiselle de Pange's is much praised, and indeed better; but her hair is metallic. This is also the defect of the head [p.400] of a Petit paysan whose dull, yellow hair is copper. For the rest, in terms of dress, character and color, it's the work of a skilled man.

But I'll leave all these portraits there to run to the one of his wife8.

I swear this portrait is a masterpiece that one day in the future will be priceless. How her hair is done! How real that chestnut hair is! How well that ribbon cinches her head! How beautiful that long braid, which she pulls over her shoulders with one hand and twists several times around her arm! Now that's hair! You should see the care and truth with which the inside of this hand and the folds of these fingers are painted. What finesse and variety of hues on this forehead! We reproach this face for its seriousness and gravity: but isn't this the character of a fat woman who feels the dignity, the peril and the importance of her state? Why don't we also reproach her for those reddish features at the corners of her eyes? What's wrong with her yellowish complexion at the temples and towards the forehead, that throat that's getting heavier, those limbs that are sagging and that belly that's starting to rise? This portrait kills all those around it. The delicacy with which the lower part of this face is touched and the shadow of the chin cast on the collar is inconceivable. One would be tempted to run one's hand over that chin, if the austerity of the person didn't stop both the praise and the hand. The fit is simple. It's that of a woman in the morning in her bedroom; a little black taffeta apron over a white satin dress. Put the staircase between you and this portrait, look at it through a telescope, and you'll see nature itself. I defy you to deny me that this figure looks at you, and lives.

Ah, Monsieur Greuze, how different you are from yourself when it's tenderness or interest that guides your brush. Paint your wife, your mistress, your father, your mother, your children, your friends, but I'd advise you to send the others back to Roslin or Michel Vanloo.

The little Salon booklet promised us a few more pieces by this master, such as Une petite fille lisant la Croix de Jésus; Une jeune fille qui a cassé son miroir9 ; the small painting he calls Tendre ressouvenir10; but these paintings have not been exhibited, because those to whom they belong did not see fit to consent. You have to be a very unsociable animal to deny the public the pleasure of enjoying a pretty painting for a few weeks; you have to have very little justice and very little friendship for the artist to thus deprive him of the most flattering reward for his work, the public's suffrage; to even harm his fortune, by preventing the public from knowing his merit through the variety of his productions. I've heard it said that La Fille qui a cassé son miroir is a masterpiece. I cannot conceive of people who believe they are adding to their enjoyment by preventing others from sharing it. M. le marquis de Marigny paid Greuze a thousand écus for the painting of the Fiançailles at the last Salon11, which will one day be priceless. We flattered ourselves at least to see it multiplied by engraving; it would have been a profit for the painter, and a great pleasure for the public; but the possessor did not see fit to grant it to us. M. de Lalive, who first made Greuze's talent known, heartily consented to the engraving of his painting of Le Paysan qui fait la lecture à ses enfants12, and there is no man of taste who does not own this print. It would have been nice to have the rest of these paintings: the Piété filiale had not yet been sold at the close of the Salon. I was assured that the author had refused two thousand ecus. All Greuze has to do is continue, and he will soon be, along with Vernet perhaps, the only man to envy the Académie. After all, what are Vanloo and Deshays compared to Raphaël, Correggio, Guide and the Carracci? Instead, once you've seen the most sublime paintings, Greuze still touches and interests. How much genius, wit and delicacy this man has! There are a thousand precious things in his painting. This bitch being suckled by her pups transports me13. The old mother's head and the character of her affliction are an astonishing thing, but when there was in the whole picture only the son-in-law's head, one would have to kneel before the artist. This head is more eloquent than Racine's most beautiful scene. Oh, how touching is this son's piety! The painter knew exactly why he called his painting Filial Piety. He had imagined placing in the corner next to the maid a table set and the meal ready for the family, to make it clear that all the policing of the house was subordinated to care for the infirm father; but this idea had to be sacrificed to the general harmony, which seemed to suffer from this white tablecloth. Envy and jealousy will have their way; I have seen with my own eyes a woman approach Greuze's painting, contemplate it, and burst into tears. I've been told that this happened more than once during the Salon; there is no criticism that these tears don't erase.

Notes

Diderot's daughter Angelique, born in 1753, was therefore 10 years old when Diderot wrote these lines.

They like to be of service.

"To feel, speaking of the movements of the soul, means to be sensitive, to be touched, to be moved." (Trévoux Dictionary)

"Déjà, tout près, brûle la maison d'Ucalégon" (Virgil, Énéide, II, 311-312, the burning of Troy).

The time of one's own death.

There are some who say that...

Diderot paraphrases a line from the prologue of Terence's Andrian, where the poet responds to his detractors who accuse him of transposing a play by Menander: Faciuntne intellegendo ut nihil intellegant? (v. 17), Don't they prove, to make connoisseurs, that they know nothing about it?

See the Hermitage sanguine, #002317, which may be a preparatory study for this painting.

See #000742.

See #006230.

Grimm means The Agreementvillage name, see #001073.

See #002864.

Front right in Le Paralytique.

Les Salons de Diderot (édition)

Archive mise à jour depuis 2023

Les Salons de Diderot (édition)

Salon de 1763

Préambule du Salon de 1763

Louis-Michel Vanloo (Salon de 1763)

Deshays (Salon de 1763)

Greuze (Salon de 1763)

Sculptures et gravures (Falconet, Salon de 1763)

Salon de 1765

La Chaste Suzanne (Carle Vanloo, Salon de 1765)

Boucher (Salon de 1765)

La Justice de Trajan (Hallé, Salon de 1765)

Chardin (Salon de 1765)

La jeune fille qui pleure son oiseau mort (Greuze, Salon de 1765)

La Descente de Guillaume le Conquérant en Angleterre (Lépicié, Salon de 1765)

L'antre de Platon (Fragonard, Salon de 1765)

Sculpture (Salon de 1765)