The torn portrait

In Hong Kong, an international press and media magnate has established his quarters in a gigantic tower on which is displayed, as a symbol of his power over the world, a portrait of himself printed on an immense canvas. James Bond and his Chinese partner, imprisoned on the top floor of the tower, escape by jumping out of the window. They cling to the portrait, which slowly tears through the middle, cushioning their fall. The couple falls and the portrait tears. Without this tear, the portrait, an image among images in a world teeming with them, would go unnoticed despite its gigantic size. In the jungle of the sprawling city, it would never surface. The tearing of the portrait triggers its "faire-surface", i.e. another modality of meaning than the rhetorical one, which refers the gigantic signifier of the portrait to the phallic signifier of its omnipotence. The portrait now signifies, and how much more effectively, insofar as meaning revolts in it, subverts itself in it: it is no longer the image of the powerful man, but the material surface of the canvas that makes sense; it is no longer the manipulative power of misleading information, but the principial force of the truth of the real that makes its appearance here.

.

The scene is constituted by this double game: it tears at the rhetorical surface of the constitution of meaning as a game between a codified signifier and a consensual signified, ideologically accepted and permitted. But in tearing up this surface, it reveals it as the materiality of a surface, and from this very materiality is born another meaning, directly articulated to the real. Is it by chance that this leap into the void consecrates and crystallizes the unexpected pairing of the two spies? The torn surface of the portrait, at the gates of China, no longer refers to the phallic economy of power, which the couple puts in check, but to a symbolic economy of the hymen, marked by the initiative and independence of the woman who refuses to let herself be reduced to the role of James Bond girl: the hymen is the sensitive surface offered to tearing, a tearing that is no longer deconstructive (offered), but foundational (assumed). The photographic surface of the portrait is transmuted into the sensitive surface of the female sex; the phallic economy of the signified becomes the economy of female jouissance.

This scene of the torn portrait could be the emblem of any literary scene. In effect, it images what we might call its fundamental metonymic ambiguity, the fact that it combines a container and a content, the surface of a spatial device (the tower, the portrait) and the feature of an action that short-circuits language (the fall, the tear).

The scene of the torn portrait could be the emblem of every literary scene.

Action and place: a founding metonymy

This metonymic ambiguity is historically explained by the word's theatrical origin and the work (if not scientific, at least cultural) of its etymology. Indeed, when we read the definitions in classic dictionaries, we are struck by what they don't say.

For us, a scene first designates a paroxysm of action: in La Religieuse, Suzanne refuses to take her vows; in Le Père Goriot, the soldiers come to arrest Vautrin; in Les Confessions, the slave catechumen from Turin nearly rapes Rousseau.

For the dictionary, stage is theater stage and designates above all a place:

"Scène. s. f. Theater, or rather place where the first Dramatic Plays were represented. Scena. This word comes from the Greek σκηνὴ, tente, pavillon, cabane, where the first plays were represented." (Dictionnaire de Trévoux, 1771, tome septième, p. 582.)

But the word theater is ambiguous, lending itself to metaphor. The stage is the theater of action, i.e. what, of the action, in a space it delimits, is given to be seen (θεᾶσθαι). On the one hand, then, the scene is arranged, focused towards the concentration of the θέατρον; on the other, the scene unfolds, expands into a row of trees, into a tent (σκηνὴ) and, from there, implicitly, into the Tent par excellence, this Tent of Assignment where Moses surrounded by his people communicated with the absent Father : this exchange between Moses and God in the shadow of the Tent would constitute one of the possible archetypes of the scene, the origin of what makes the scene the moment of the assumption of the law. The assumption of the law is constituted by its defection: it is after Christ has cried out doubting the Father ("My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?") that, in the darkness of the eclipse, he expires and the curtain hanging in the temple, the surface of the Tabernacle, "was torn in two from top to bottom" (Matthew, 27, 51; Mark, 15, 38). The new law surfaces as the old law tears at its perimeter.

A tension, even a contradiction, then emerges between the stage as a focal point, as an exposed place of blinding monstration and, on the other side, the stage as a sheltered perimeter, as the protective shadow of the tent or intertwined branches referring to an unspeakable, searing elsewhere:

"C'étaitoit," says M. Rollin, "une suite d'arbres plantés les uns près des autres, sur deux lignes parallèles, qui donnoient de l'ombre, σκιὰ, à ceux qui étoient placés dessous pour voir les pièces qu'on représentoit y, avant qu'on avait imaginé les théâtres: d'autres disent une ramée, un assemblage de branches entrelacées sous lesquels les Bergers représentoient leurs jeux." (Ibid.)

Σκηνὴ, the scene, the tent, would come from σκιὰ, the shadow. The stage is a heart that is exhibited and an envelope that occludes, it hits and screens.

In the scene, then, there is a concentration of action, a kind of passage to the edge of discourse that, condensing, transmutes syntagmatic linearity into paradigmatic crystallization of the visible, synthesizing the message into a single image that is delivered en bloc: the actors are silent, exclaim, stammer, confronted off-discourse with "something at stake". But this crystallization can only take place through the mediation of a place that constitutes itself for the scene, to delimit its image, and if necessary to screen the unbearable revelation it represents. In this sense, the scene that appears to us always refers back to another scene, to that epiphany of the symbolic that New Testament mythography images in the Resurrection of Christ (it's the central scene of the Gospels, and it's at the same time the missing scene), or in his appearance to Paul on the road to Damascus, a dazzling apparition that grounds recognition on blindness.

The stage is always the site of this ignition that blocks speech and manifests the presence of the symbolic, and at the same time it misses this ignition, or more exactly obscures it because the process of discursive condensation, the movement of enunciative synthesis that brings the stage into play confronts it with a kind of imbalance between the overflow of the signified and the failure of the signifier. The scenic device can only cover up the horror or dazzle of this unrepresentable. Indeed, discursive condensation and image crystallization function simultaneously as a passage to the device, as the construction of a scenic site and, in reverse, as a symbolic purification, as the exposure of its principle below the meandering, intertwined institution of language. This denudation, this ignition, combined with the material highlighting of the σκηνὴ (the set, the background, the perimeter, the shading), constitute the very mechanism of representation. The scene is thus always programmed to fail: neither Mary Magdalene in the garden nor Paul on the road recognize Christ; the revelation they receive is based on an essential, necessary failure of the encounter.

More to the point, if the scene doesn't fail, it plunges into shadow what it brings to light, in the double gesture of the Tabernacle half-opening and closing, which from the status of the place of encounter passes to that of the material object of canvas, the very surface of the representation, its décor.

"Scene, is taken more particularly for decoration, all that serves the theater. Scenalis species, decor scenicus. Thus the scene is said to change, to express the change in decoration. The scene represents a palace, a forest, a mountain, &c. There were, according to Vitruvius, three kinds of scenes or theater decorations among the ancients." (Ibid.)

Classical tragedy always rejects offstage, in the wings, the horror it nevertheless places at the heart of the performance. The dramaturgy it promotes runs to the crime it cannot yet stage. All the speeches are there only to prepare for what cannot happen, as if representation were only woven from that which tears it apart, from this relationship to the symbolic Thing whose dazzling blindness it promotes, and at the same time delimits, at the back, the sanctuary that a set, a scene, comes to cover. Behind "the stage represents a palace", then, we read the invisible presence of the bowels of this palace, the real non-place of the other stage, whose actors' speeches come before us to open the breach and close the set.

.

From the theatrical to the novelistic stage

The novelistic scene comes to structure itself metaphorically in relation to this theatrical mechanism of representation. To speak of a scene in a novel is to speak by borrowing from a properly theatrical phenomenon, inscribed in the space and play of theater, for a text and genre in which, strictly speaking, there is neither space nor play, where everything is covered by language. The novelistic scene thus functions as a supplement, not that supplement of speech that Derrida's writing would constitute, but, speech and writing taken together, the supplement by and in language of that which is irreducible to language and yet founds it, that fundamental metonymy of the stage that combines the θέατρον with the σκηνὴ, the focal given-to-see where the gestus is played out and the sheltered place, the shadow-providing periphery of this game. The dialectic of the supplement is not played out within language between living speech and the absenteeism of writing, but between the interiority and exteriority of language, between discursive logic and the logic of the device.

.

The something and its transport: the Turin catechumen

It is in this respect that the enterprise of the Confessions constitutes something of a pure paradigm of the stage. To bare oneself in a book for an audience is to unite the heart and envelope of language, the "me" as enunciative instance and the "me" as object of the utterance. The "me" constitutes both the "given to be seen" and the device of the Confessions, which are thus constructed as a gigantic stage. This dynamic of the scene in Rousseau, generically programmed to fail, fails, unravels in the epistolary exchange1 from book nine onwards, when, with the retreat to the Hermitage, the very attempt at an encounter with the Other becomes impossible.

Because it refers to this exteriority of language, because it comes there as a supplement to this irreducible lack of the θέατρον and the σκηνὴ, the novelistic scene is worked by metaphor. It is the effort of narrative writing to break out of its fictional and rhetorical framework; it is the revolt of narrative against the tyranny of language, the passage to the pragmatic beyond of the cut, the reunion with the gestus, with the principial demand of the Real in its primordial point of conjunction with ethical questioning: "something" is happening, "something" is at stake. "Something" is not language.

This stripping away of language towards a "something" that is of the order of the θέατρον, the given to be seen of the scene, is particularly sensitive in the scene of sexual provocation that Rousseau undergoes at the hospice for catechumens in Turin:

"The next morning quite early we were both alone without the assembly room. He resumed his caresses, but with such violent movements that it was frightening. At last he wanted to go by degrees to the most improper privacies2 and force me by disposing of my hand to do the same. I shrieked and jumped back, and without showing any indignation or anger, for I had not the slightest idea of what it was all about, I expressed my surprise and disgust so energetically that he left me there: but as he finished struggling3, I saw something gooey and whitish fall down the chimney and onto the floor, which made my heart skip a beat. I rushed out onto the balcony more moved, more troubled, more frightened even than I had ever been in my life, and ready to find myself hurt." (II, 104-105/674.)

All discourse suspended, the very brief scene is constituted by this repugnant trajectory, the unspeakable horror of the "slimy je ne sais quoi" where jouissance is played out, to which Rousseau's inverse trajectory responds, from the room to the balcony, i.e. spatially, once again from an inside to an outside. The material, geometrical path that delimits the stage is matched by a symbolic path, what Rousseau calls "transport". The "something" of the stage has to do with this transport of jouissance, insofar as what is given to see there is immediately blinded, fascinated by it, so that it can take place. Rousseau concludes:

"I have never seen another man in such a state; but if we are thus in our transports near women, they must have their eyes quite fascinated not to take us in horror."

The "something" at play in the scene is the blinding horror projected by the principial reality of the Thing, both the reality of jouissance and the originary force of the moral law, this energy of disgust that will come to cover, the Jesuit administrator's speech ("imagining that the cause of my resistance was the fear of pain, he assured me that this fear was vain, and that there was nothing to be alarmed about"). The Rousseauist scene fails here as it always does, through an excess of visibility, through that clear-sighted disgust which forbids fascination5.

And yet this "something" outside language only manifests itself because language revolves around it and, outside it, by default, circumscribes it. For Rousseau, the scene of the catechumen bandit6 metaphorizes every scene of jouissance and, from there, returns the very image, by definition doubly unrepresentable, of the jouissant "me": a "me" made Other of the scene, a petrifying, fascinating "me" transmuted into that "something", or rather that horrifying "I don't know what" of the scene. Through the stage, writing pretends to emerge not only from itself, but from the very game of language. Something else is at stake, the Thing itself, we might say, i.e. the real. This feigned fall back into the real takes place in the scene through the temporary cancellation of the "as if" of metaphor, through the momentary elision of the metaphorical cut. We think we're really dealing with the pederast catechumen, a unique case whose uniqueness sets the scene: "I've never seen another man in such a state". But this "other" that Rousseau cannot see is revealed immediately afterwards, indirectly, in the "we" ("if we are like this in our transports"): it is Rousseau himself, seized in the specular horror of jouissance. The essential metaphor is then revealed, which does not operate the displacement of one literary genre into another, but, whatever the literary or artistic form of the scene, effects the shift, the conjunction, the passage of the real itself into representation (here of the "I" in the catechumen): the scene unfolds as if it were theater (scenographed by the cry and by the double trajectory) and, from there, much more fundamentally, as if it were real: here, the very reality of masculine jouissance.

Something turns around: Zulietta's one-eyed nipple

The device is recurrent in The Confessions. We find it again when, in Venice, as payment for services rendered to a merchant, Rousseau is offered the charms of a courtesan, the beautiful Zulietta:

"I entered the chamber of a Courtesan as into the sanctuary of love and beauty; I thought I saw divinity in her person." (VII, 60/320.)

The scene is built from the penetration of an enclosed place, a σκηνὴ which, for the duration of the theatrical illusion, will function as a sanctuary, i.e. as the enclosed enclosure from which the law radiates. The dynamics of the scene lead to its failure, that is, both to the reduction of the metaphor (the sanctuary reverts to a courtesan's bedroom) and to the blocking of the transport, the reversal of the ignition:

"Suddenly instead of the flames devouring me, I feel a deadly cold running through my veins; my legs go limp, and ready to find myself in pain, I sit down, and weep like a child."

The sexual breakdown turns the flames of transport into "a deadly cold" which, inhibiting action, paradoxically marks the fall back into reality and, through this fall back, the passage from the imaginary to the symbolic, from the dream of embracing a goddess to questioning the setting and the social implications of the scene. The object of our gaze, "this object at my disposal", is reduced to something around which everything revolves. Why does such a goddess offer herself to Rousseau?

"There's something inconceivable here. Either my heart deceives me, fascinates my senses and makes me the dupe of an unworthy slut, or some secret flaw I'm unaware of must destroy the effect of her charms and make her odious to those who should be vying for her. I began to search for this defect with singular restraint of mind [...].

These reflections, so well placed, agitated me to the point of tears. Zulietta, for whom this was surely a brand-new spectacle in the circumstances, was for a moment forbidden. But having taken a turn around the room and passed in front of her mirror, she understood, and my eyes confirmed to her that disgust had no part in this rat. It wasn't hard for her to cure me of this little shame. But just as I was about to swoon over a throat that seemed for the first time to suffer a man's mouth and hand, I realized that she had a one-eyed nipple."

The one-eyed nipple defeats the whole enterprise. Jean-Jacques gets dressed and will never see the lovely Zulietta he had so longed for again. The progression of the scene here is skilful, from the "something inconceivable" that, abstractly, works on Rousseau's incredulity in the face of such beautiful lures, to "some secret flaw" towards which he turns, then to the "rat", i.e. the oddity that forbids the young woman, until, finally, the one-eyed nipple that completes the materialization of the Thing and crystallizes the θέατρον of the scene (the detail given to be seen) in the form of a tear in the flesh, a lack metaphorically designated as blindness, i.e. as castration. As in the Turin episode, the abjection of the other is here an image of the sexual impotence that bars the "I". The charming figure of the goddess in her sanctuary has turned into a defect, a rat (another metaphor for the female sex), a one-eyed nipple, a punctured eye and torn flesh, an irrepressible horror of the real and the advent, through castration, of the law.

Scene doubling and memory work: Maman's periwinkle

The "something" of the scene, which is not an object but the signifying articulation of what is played out there, does not always manifest itself there as soiling, dejection or tearing. We need only compare the scene of the Turin catechumen or that of Zulietta with the one that opens book six, when Rousseau arrives at Les Charmettes:

"The first day we went to sleep at Les Charmettes, Maman was in a sedan chair, and I followed her on foot. As the road climbed, she was quite heavy, and fearing to tire her porters too much, she wanted to get off about halfway to do the rest on foot. As she walked, she saw something blue in the hedge and said to me: "Here's some periwinkle still in flower. I'd never seen periwinkle before, so I didn't stoop to examine it, and my eyesight is too short to distinguish plants of my height on the ground. I only glanced at this one in passing, and nearly thirty years have gone by without my ever seeing periwinkle again, or paying any attention to it. In 1764 being in Cressier with my friend M. du Peyrou, we were climbing a small mountain at the top of which he has a pretty salon7 which he rightly calls Belle-Vue. I began to forage a little. As I climbed up and peered among the bushes, I let out a cheerful cry: ah voila de la pervenche ; and indeed it was. Du Peyrou noticed the transport, but he did not know the cause; he will learn it, I hope, when one day he reads this." (VI, 289-290/226.)

On the surface, there's no connection between the refinement of sensitive delicacy with which this bucolic anecdote is told and the ignominy of the episodes in Venice and Turin. Yet we can't help comparing the "whitish je ne sais quoi" of the first scene, the "some secret flaw" of the second and the "something blue" found here, the abomination of sexual transport and Rousseau's enlightened transport in front of his periwinkle, behind which looms the beloved shadow of Mme de Warens (σκιὰ of the σκηνὴ, given to see and obscured). In front of the periwinkle, as in front of the catechumen, the encounter is at first missed. Rousseau, myopic, cannot see the object, which remains "something blue". It is the botanist's taxonomic knowledge and the work of reminiscence that enable the walker, thirty years later, to recognize the initially unrecognized flower, to enjoy the missed object of jouissance after the fact. The periwinkle then exceeds the recognized object: it surfaces as a memory surfaces, but also as a signification is established, outside botanical taxonomy, a singular signification of "transport" where the other knowledge, the knowledge of jouissance, is summoned. The periwinkle was at first less than a flower, and then much more: such is the "something" of the scene that disappoints only to overcomplicate, that undoes recognition in the field of language ("Voilà de la pervenche") to rebuild this recognition elsewhere, at the end of the transport: transport in time (after thirty years), in space (after the climb) and in metaphor, "Ah! voilà de la pervenche !" written in italics takes on meaning only as a quotation from the absent beloved, the one Rousseau never knew how to meet definitively.

We can analyze the writing of the periwinkle scene in Derrida's way, in terms of supplementation by the writing of the living word: Rousseau's word supplements Mme de Warens' word, comes to make sense of it for Rousseau; the writing of this word in the Confessions in turn supplements Rousseau's word, whose transport had remained enigmatic for his companion at Peyrou. But is this really the essential dynamic at play? Isn't the heart of the scene, rather than Mme de Warens' phrase, that "something blue" which, for the space of a moment, abolishes the mediations of language to bring Rousseau into direct contact with nature grasped beyond the object, as a maternal Thing joining, in the back-and-forth of a glance of connivance at first misunderstood, Maman's heavy body to the delicate spot of color of the periwinkle?

The novelistic scene thus manifests itself as the moment, in writing, of the lifting of a certain metaphorical cut, which is the very cut on which the distance, the gap constitutive of representation is founded. This presence-absence of the metaphorical cut in the novelistic scene is fraught with symbolic implications: it is the cut of castration; it is the cut of revolt; it is tearing; it is "surfacing". It is from this symbolic splitting, in which the castrating assumption of the Father's law is played out and radically challenged in the name of the principial instance of feminine revolt, that the novelistic scene is constituted. In a way, we could say that the function of the novelistic scene is to exhaust this symbolic splitting, to play it out to the final wear and tear of its springs.

.

The fiction of off-language

Analyzing a scene in a novel therefore means starting from the founding metonymy, from the interplay between the constitution, the delimitation of a place, an area, a surface and the deconstruction, or more precisely, the stripping bare of a symbolic stake: the mesh of discourses is torn apart and "something" appears. The "faire-surface" of the stage thus designates and combines two things: the passage from a logic of narrative to a logic of device on the one hand opens up and delimits a space of representation (a σκηνὴ), and on the other transmutes language into a sensitive surface, into "something" that in the stage surfaces, i.e. is given to be seen, to be experienced (a θέατρον). As for the tear, it is the affective point of the "faire-surface", marked by silence or interjection, by ellipsis or line; it is the defection of language and the inaugural revolt of the scene.

But this "faire-surface" of the stage, like its inaugural tear, only takes place metaphorically: the scenic device, like the ignition process that makes something appear, exists for us only through language, only as facts of language. Flaubert insists on this when Madame Arnoux enters the stage on the boat: "It was like an apparition". The as indicates that something other than the apparition is represented here, something else that tends towards it as towards an inaccessible ideal, the very ideal of the encounter with the Thing, Moses in his tent, Paul on the road to Damascus, Rousseau in the unnameable journey of the other ejaculation. During the time of the stage, this gap in the "as" fades and is obscured, slipping into the shadows: the stage is the moment when writing tends to abolish itself in the feigned emergence of the real, when appearance tends to replace representation.

This erasure of language during the time of the stage is dearly paid for by writing. The constitution of σκηνὴ prompts the thickening, the return of σκιὰ, the shadow of discourse that encircles the scene: the symbolic work of the discursive shadow weighs heavily on the stage. Another game is then set in motion: the tear, which undid language to reveal "something", then manifests itself, by a return effect, as the founding tear of the phallic function in language, as a manifestation of the castrating power of paternal law. In the opposite direction, the device of the stage, its "faire-surface", triggers all the resistances of the screen, initiates a dynamic of reversal, revolt, volte-face: in the place, in the gestus of the stage, something refuses to let itself be reduced, to return to language.

The chiasmus of the visible

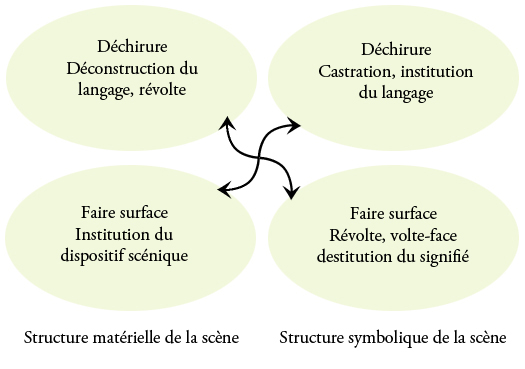

The structure of the novelistic scene thus appears as a chiasmatic structure, the tear and the "faire-surface" interchanging their constructive and deconstructive functions through the play of metaphor:

Or this fundamental chiasmus could well be the chiasmus inherent in the phenomenological constitution of the gaze, in that finger-in-the-glove reversal of outside and inside analyzed by Maurice Merleau-Ponty in Le Visible et l'invisible. In the novel, scenic crystallization marks both the passage from a logic of discourse to a logic of the image and, like a crossing of the mirror of representation, the exchange of the symbolic functions of tearing and "making-surface".

.

From the failed scene to the moral image: "a little sign with the finger"

This crystallization and the chiasmus proper to the passage to the image are particularly sensitive in the scene of the "little sign of the finger8". After his conversion to Catholicism, Rousseau worked in Turin as an engraver for Madame Basile, with whom he fell in love:

"One day, bored by the clerk's silly colloquies, she went up to her room, so I hurried into the back store where I was to finish my little task, and followed her. Her room was ajar; I entered unnoticed. She was embroidering near a window facing the side of the room opposite the door. She couldn't see me enter, nor hear me, because of the noise of the carriages in the street. She always dressed well: on this particular day, her finery bordered on the coquettish. Her attitude was graceful, her head a little lowered, revealing the whiteness of her neck; her hair, elegantly lifted, was adorned with flowers. There reigned in her whole figure a charm that I had time to consider9, and which put me out of my mind." (II, 114/75.)

The setting of the scene's device is well ordered around the metonymic ambiguity of an irradiating θέατρον and a σκηνὴ that blocks the gaze, forbids its response, its return: "j'y entrai sans être aperçu"; "Elle ne pouvait me voir". The scene is delivered to the young Rousseau's devouring eye, but delivered by breaking and entering, by opening the σκηνὴ: "Her room was ajar". The eye, moreover, does not see Mme Basile, but in her, the something to which the transport of desire clings: "her head a little lowered let us see the whiteness of her neck". Here again, something white is at play, a radiance that depersonalizes the beloved woman whose lowered head slips out of view, whose flower-adorned hair becomes a bouquet. Madame Basile becomes vegetalized. As for Rousseau, his transport also depersonalizes and paralyzes him. The scene then becomes suspense, crystallization, petrification of the "I" in its impossible relation to the Other: it blocks speech and institutes the device.

"I threw myself on my knees at the entrance to the room, stretching out my arms towards her with a passionate movement, of course she couldn't hear me, and not thinking she could see me: but there was a mirror at the fireplace that betrayed me. I don't know what effect this transport had on her; she didn't look at me, didn't speak to me: but half-turning her head, with a simple movement of her finger10 she showed me the mat at her feet. To flinch, to cry out, to rush to the place she had marked for me was all the same to me: but what would be hard to believe is that in this state I didn't dare undertake anything beyond that, nor say a single word, nor raise my eyes to her, nor touch her even in such a constrained attitude, to lean on her knees for a moment. I was mute, motionless, but certainly not tranquil: everything in me marked agitation, joy, gratitude, ardent desires uncertain in their object, and contained by the fear of displeasing on which my young heart could not reassure itself."

Rousseau acts as if in the theater. The metaphor is all the more sensitive here since, as Mme Basile is not supposed to surprise his play, the awkward suitor takes advantage of this situation of blocked gaze to perform to its conclusion, rather comically it must be said, the pantomime of "as if".

That the abolition of the metaphorical gap proceeds from a specular reversal, this scene shows enough, which betrays Rousseau via a fireplace mirror. The gaze is unblocked, the process of encounter triggered, only by the accident of the mirror, which tears open the foreclosure of the σκηνὴ but at the same time surfaces, i.e. closes what it opens by allowing the promised encounter, as if the glances exchanged through the mirror did not have to be assumed, as if the glass surface isolated, protected and disempowered the protagonists: "She didn't look at me". The same device is used in the scene with the one-eyed nipple, in which Zulietta, very professionally, discreetly catches Rousseau's sexual breakdown in the mirror: while the suitor's eyes speak to her of love, it's a little lower down that the real or its flaw is exposed, the "rat" of the erection that doesn't come. In both cases, Rousseau places a feminine other before him, to show him his own neantization and, at the same time, to envelop this defection, to make it slip into the shadows. Both Mme Basile and Zulietta have seen and not seen "something". The mirror's indirection enables this contradictory gesture of monstration and occultation, of constituting a "given to be seen" and enveloping the object, of θέατρον and σκηνὴ. Through this matrix ambivalence in The Confessions, with the "self" exposing its impotence so as to avoid it from the gaze of the other, Rousseau's perversion marries the structure of the scene, models itself on its device.

The mirror triggers the scene and causes it to fail: Rousseau does not declare himself to Madame Basile. His agitated state crystallizes on no desire for an object: "everything marked in me [...] ardent desires uncertain in their object". The tear constitutive of the encounter ultimately prohibits it; what, for the duration of the scene, had defeated language and established the logic of the visible and the apparition now blocks the encounter in the gaze, inhibits the passage to the act, in the same way that Rousseau missed what was at stake with the bandit of Turin or with Mme de Warens' periwinkle.

This "lively, mute scene" (p. 115) is finally interrupted by the arrival of the servant, Rosina, in the purest logic of the theatrical sequence. The missed opportunity, which will never come again, the failure of the scene, then, is made up for, as in the scene with the periwinkle, by the work of memory:

"Perhaps it's for this very reason that the image of this amiable woman has remained imprinted in the depths of my heart in such charming strokes. She even grew more beautiful there as I got to know the world and women better. [...] Nothing that the possession of women has made me feel is worth the two minutes I spent at her feet without even daring to touch her dress. No, there are no pleasures like those that can be given by an honest woman you love: everything is a favor with her. A little sign with my finger, a hand lightly pressed against my mouth are the only favors I received from Made Basile, and the memory of such light favors still transports me when I think of them." (II, 115-116/76.)

What surfaces in memory is no longer the primer of desire constituted by the depersonalized glow of a white neck, but "the image of this amiable woman", a virtuous image indeed, but desexualized. Sexual enjoyment has been transmuted into moral enjoyment, while the finger sign no longer signifies acceptance and invitation, but ritualizes and channels a trade that is satisfied with, and even glorifies itself for, "undertaking nothing beyond". The moral pleasure derived from "the image [...] imprinted in the depths of my heart11" is a painting from La Nouvelle Héloïse that comes to screen the scene from the Confessions; it falls within the device of the epistolary exchange, when Rousseau definitively renounces the stage encounter and assumes his renunciation.

The "faire surface" that prepares the stage, that institutes the stage device by setting up the enveloping space of her room around Mme Basile, as if in a jewel case, is thus here opposed by the "faire surface" of the after-scene, the moralized image that becomes imprinted in the memory. This image is deconstructive: it undoes the "something" around which the scene was organized, destroying the banal articulation of the signifier of sexual jouissance (the whiteness of Mme Basile's neck, the transport of Rousseau at her feet). This signifier of jouissance, which opened up the initial dynamics of the scene and through which it had failed, becomes the envelope of the space of philosophical commerce with women. From something white, signifying phallic desire, we move on to "a little finger sign", to a sign that signifies precisely nothing, to a gestus: there is no longer a signified, but the invitation is now present. Here another world opens up.

For the scene always brings another world, not only the beyond of the σκηνὴ it tears apart, and the conjunction played out there of the real and the symbolic, but, from this conjunction, a principial refoundation of the world, from which Rousseau will build his system. Just read the pithy sentence that sums up the illumination of Vincennes in Les Confessions:

.

"At the instant of this reading, I saw another universe, and I became another man." (VIII, 94/351.)

The scene triggers the vision (it is summed up here as the instant of "I live") and at the same time institutes the new symbolic order, both the proposal for a political revolution of the world and the decision for moral reform of the "I".

From the novelistic to the political stage

The failure of the novelistic scene programs not only the scenes of the Confessions, but the very journey of the text and the moral path involved. Rousseau's self-imposed moral reform, culminating in his retirement to the Hermitage and his uncompromising refusal to compromise in the bonds of literary and worldly sociability, serves as the structural foundation for the dynamic of the scene that drives the writing of the Confessions: the scene is the staging of the principial failure of the encounter, a failure in which the social bond surfaces and in the process is torn apart. Rousseau fails to establish the link, in an ambivalent gestus, a posture of double entente, between shame and refusal, between disgust and impotence.

Or this repeated failure, this evasion of jouissance, is in a second stage recovered in the assumed decision to retire: the novelistic scene disappears from the Confessions from book nine onwards, and the encounter is replaced by the epistolary exchange, which produces this curious ballet of letters and replies inserted into the body of the text.

However, if formally the novelistic scene disappears, the economy of failure and the text's tension towards the scenic crystallization of another world seem to endure, and even systematize. Rousseau's narrative arrives at the moment of gestation of La Nouvelle Héloïse, where fiction enables the old device of the encounter programmed for failure to be perpetuated in the new structure of epistolary exchange. Another scene is then set up:

"6. Unable to taste in its fullness this intimate society I felt the need for, I sought in it supplemens which did not fill the emptiness, but which let me feel it less [...].

7. My beginning led me by a new route into another intellectual world whose simple and proud economy I could not without enthusiasm envision. Soon, by dint of dealing with it, I saw nothing but error and folly in the doctrine of our sages, and oppression and misery in our social order. In the delusion of my foolish pride I thought I was made to dispel all these prestiges; and judging that, in order to be listened to, it was necessary to bring my conduct into line with my principles I took the singular course that I was not allowed to follow, whose example my so-called friends could not forgive me for, which at first made me ridiculous, and which would finally have made me respectable, if it had been possible for me to persist in it.

[...] This is where my sudden eloquence was born; this is where the truly celestial fire that engulfed me spread in my first books" (IX, 168/416).

Writing supplements the failure of the social bond, "that intimate society I felt I needed". But this supplement does not essentially re-establish a presence or semblance of presence that would compensate for the matrix tear in this intimacy. What is at stake is the transformation, the "revolution" of a "me" who, through the visual crystallization of the scene, through the image of this other world he sees before him, takes the side of subversion: "I no longer see anything but error and folly in the doctrine of our wise men, oppression and misery in our social order". The image triggers subversion. The new medium of the stage becomes philosophical eloquence, understood not as the writing that brings back presence, but as the support for the representation of the "other world", as the surface on which to materialize the tear in the world. Eloquence is defined neither as rhetoric, nor as writing, but as ignition ("that truly celestial fire that set me ablaze"), that is, as a properly scenic means of transmuting discursive demonstration into the theater of the world.

Then the failure of the stage triggered by the fire of Rousseau's eloquence takes on an entirely different meaning from the all-too-trivial one of the defection of the "me": it becomes a revolt against the agreed-upon doctrines of our sages, a revolt against oppression and misery, no longer a failure of the encounter, but a haughty protest against the encounter. The scene's tear is no longer deceptive, left to the infinite recollections of the "self", but a tear of revolt, through which the new symbolic order is posited.

Conclusion

I have summarily attempted to define the scenic tear as defection, deconstruction, the stripping away of the symbolic principle beneath the interlacing of language: the crying and jumping in front of the Turin catechumen, the weeping in front of Zulietta, the barely-there glance at something blue, the mute gesticulation at Mrs. Basile's feet are all reductions of the narrative to a gestus supposed to deliver the "I" out of language, in the vulnerable authenticity of its constitutive tear.

The "faire-surface", meanwhile, manifests itself in the transmutation of narrative into scenic device, of narrative unfolding into the space of suspended action. This effect of the stage is more difficult to characterize. The trajectory of the "slimy je ne sais quoi", the sanctuary of the Venetian courtesan, the path leading up to Les Charmettes, Mme Basile's half-open room, do not so much deliver the place of the scene as what might be described as its sensitive envelope, what crystallizes and obscures it, what concentrates and shelters it. Rousseau most often uses the term "transport": the linearity of the journey can still be read in the word "transport", at the very moment when we tip over into affect, when all distance, all mimetic deviation are abolished in the pathic overbidding of what, there, comes to the surface. Faire surface" is a place and an emergence, a device and a process.

Between the tear and the "faire-surface" of the scene, a strange dialectic is initiated which, initially deconstructive (the scene fails, language is undone, the law is transgressed), turns into symbolic refoundation, once an image effect, the crystallization of a gaze, is set in motion.

For Rousseau, this refoundation is moral and political: the destroyed scene opens up writing to another scene, what he himself calls "another universe" or "another world". The failure of the scene, which constitutes the dynamic program of the Confessions, is made up for by the intellectual construction of the state of nature as the constitutive scene of the social contract, the education system and the love game.

At the end of this paper, I would like to express my indebtedness to the work on Rousseau by Jean-Christophe Sampieri, of Grenoble's Stendhal University.

Communication given at the colloquium La Scène, université de Toulouse-Le Mirail, Centre universitaire d'Albi, May 6, 1998

Notes

Cf. X, 312, "le recueil de lettres qui m'a servi de guide dans ces deux livres". In the next two books, Rousseau continues to insert letters that make up for the face-to-face meetings and explanations that no longer take place.

the most shocking, in the Paris manuscript.

of struggling, without respect of the'altar and of the crucifix which were before him, I saw...., in the Neuchâtel manuscript.

The first reference refers to the folio edition, the second to the Pléiade.

The floating between the scene in L'Émile and that in theConfessions invites us to ask whether this is not a screen scene, covering up a fascination that was later censored. Rousseau asserts elsewhere, with regard to Thérèse, that for him the ideal of love is the love of the Same. But above all, the moral conclusion of the episode was much more ambiguous in the Neuchâtel manuscript, which was censored: "This precaution shielded me for the future from the undertakings of the Knights of the Cuff, and the sight of people who passed for them reminding me of the look and gestures of my frightful Moor has always inspired such horror that I could hardly hide it. On the contrary, women gained a lot in my mind from this comparison. Les idées qu'elle me fit be changing in desir and in charm the disgust that I'see eu until'then for their joy. " (106/69.)

His name was Abraham Ruben. Rousseau proposes a second version of this episode in Book IV of L'>Emile: he would have escaped from the hospice just after his conversion to escape the outrages of one of the hospice's leaders.

"il a" (Pléiade) and not "il y a" (Folio). The salon is a garden salon.

See J. Starobinski, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, la transparence et l'>obstacle, "Le pouvoir des signes", 1957, Gallimard, 1971, Tel, pp. 184sq. J. Starobinski contrasts the scene in the Confessions with the substantially different account given by Bernardin de Saint-Pierre in his Vie de Rousseau: "Un seul signe a été la source de mille lettres passionnées". The sign in Les Confessions, which makes no mention of any letters, leaves behind the logic of the written word, of the inscription of reality in language, to enter a logic of the stage, of crystallization through the gaze. What is at stake in the scene is not the meaning or interpretation of the sign, but its iconic power of condensation.

sentir instead of considérer in the Paris manuscript.

of a simple finger sign in the Paris manuscript. It is the latter expression that is repeated below.

Compare with the conclusion of the catechumen's scene: "The image of what had happened to me, but especially of what I had seen, remained so strongly imprinted in my memory, that when I thought of it, my heart still lifted." (II, 106.)

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « La déchirure et le “faire-surface” : dynamique de la scène dans Les Confessions de Jean-Jacques Rousseau », La Scène. Littérature et arts visuels, dir. Marie-Thérèse Mathet, L’Harmattan, 2001, p. 223-239.

Rousseau

Archive mise à jour depuis 2001

Rousseau

Les Confessions

Julie, le modèle et l'interdit (La Nouvelle Héloïse)

Le charme désuet de Julie

Julie, le savoir du maître

Passion, morale et politique : généalogie du discours de La Nouvelle Héloïse

L'économie politique de Clarens

Saint-Preux dans la montagne

La mort de Julie

La confiance des belles âmes, de Paméla à Julie

Politique de Rousseau

La nature comme espace d'invisibilité

Entre prison et retraite : Rousseau juge de Jean-Jacques

L'article Economie politique