Casanova's autobiographical project began in the autumn of 1785, when he was hired by the Count of Waldstein as librarian at his castle in Dux (Duchcov in Czech), some one hundred kilometers northeast of Prague. Casanova was 60 years old. He had indeed published Le Duel in 1780, but he was still writing in Italian at the time1. In 1786, he published the Soliloquy of a Thinker2 ; in 1787, the Histoire de ma fuite is printed3 : she makes the escape from the Plombs prison in Venice, in 1756, the primitive core of the project ; in the summer of 1789, i.e. just as the Revolution breaks out in France, Casanova begins writing the Histoire de ma vie.

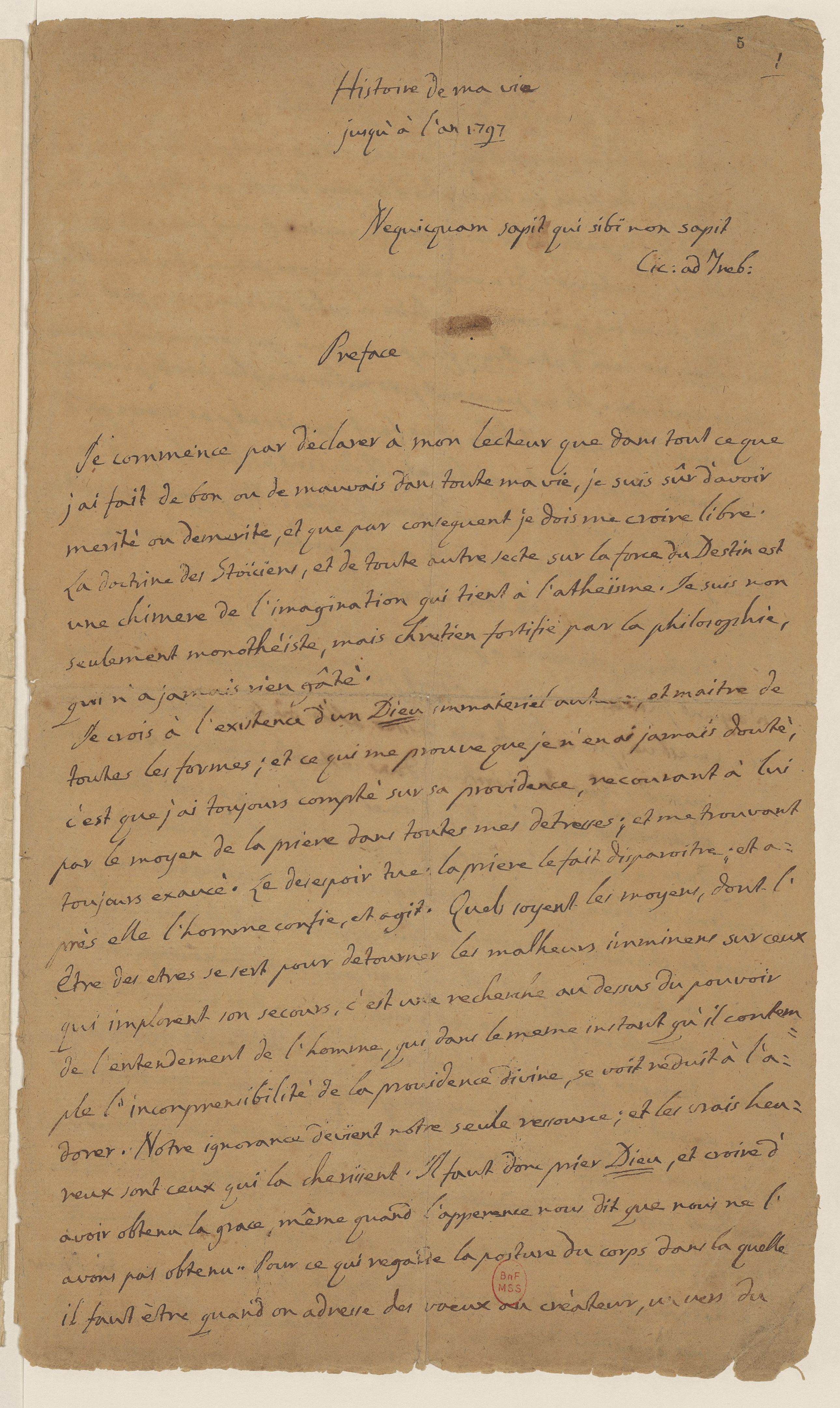

The immense 3700-page manuscript4 would be written in three successive waves, as evidenced by the three prefaces : that of 17915 marks the end of the 1st wave ; that of June 17946 constitutes the starting point for the revision of the manuscript, and for example for the rewriting of the episode of the first stay in Paris, the departure for Vienna and the return to Venice, which constitutes the first major part of volume II ; the 1797 preface7 finally announces a History that would run until 1797, a project that Casanova would not have time to complete.

The aim of this course is to try to understand this project : for it is a project rather than a book. It's not just for lack of time that Casanova didn't publish his Histoire : it's also because his project departs radically from what twentieth-century narratology has theorized as the genre of autobiography, with its reading contract (Ph. Lejeune8) and its overwhelming model, Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Confessions. Casanova doesn't accuse or justify himself in it : he writes life and, through this bio-graphy, he restores its possibilities. In other words, he doesn't give an exact account of his life, but rather from his life of what in life makes life possible. He continues to live in the proxy that writing gives him of life. Through writing, he once again makes life possible.

We won't therefore propose here to reconstruct a career as a writer9, even if it's true that Casanova wrote a lot : he had no success as a writer, he who as a storyteller in society, as a living orator, had conquered fame throughout Europe. Casanova not only made a career of his bon mots, his faconde and his stories he felt alive in the moments he held his listeners suspended to his lips and, as he grew older, it was this logic of living in storytelling that he undertook to restore, to mimic in writing.

The hesitation over the title given to his text betrays his status, his /// supplement function, which supplements, prolongs life rather than representing it. The 1791 preface bears Histoire de mon existence ; that of 1794 is presented as Mémoires de ma vie écrits par moi-même à Dux en Bohême ; and it is only in the 1797 version that the text takes as its title Histoire de ma vie jus jusqu'à l'an 1797. These titles do not designate a finished work, but a writing project.

De-moralizing history

" When I announce myself as the historian of my existence... ", he begins in 1791 (p. 1318). The historian here is not the scholar who deals with history, but the one who tells one or more stories. He does not do so in the spirit of a confession:

.

" I must warn the reader that in writing my life I claim neither to praise myself, nor to give myself as a model : on the contrary, it is a true satire that I am making of myself, despite the fact that he will not find in it the character of confession. He will see that I have never done good except out of vanity, or interest, and evil out of inclination, that I have never committed a crime out of ignorance that prohibitions instead of diminishing my courage, have increased it : that happy enough to find permission in my strength, I let myself go10, often willing to pay the fine. " (Preface to 1791, p. 1324)

Eloge, satire, confession : Casanova reviews the possible genres, and challenges them one by one. First of all, he takes the autobiographical project out of the moral framework of praise : this story of my life is not a self-justification, this life does not construct a model of the " me11 ". To underscore his indifference to and autonomy from moral judgment, Casanova argues for satire over praise, and paints a portrait of the Enlightenment libertine, driven to crime with full knowledge of the facts (" I have never committed a crime out of ignorance "), enjoying defying the forbidden (" prohibitions, instead of diminishing my courage, have increased it "), respecting as law only the cynical balance of power (" happy enough to find permission in my strength "). We recognize here one of those characters whose fiction and system Sade, in those same 1790s, is implementing.

But Casanova is no Sade. This vitriolic anti-portrait of satire unshackles the Histoire de ma vie from the model of eulogy, de-moralizes the autobiographical project : " vous communiquanrt mes actions, mon cher lecteur, je les donne pas comme des exemples à suivre " (p. 1326). For all that, there's no complacency here in abjection :

" In spite of this, complacent as I am, I would not write my life, if I thought to make myself thereby contemptible. I am sure that my equals will not despise me, and that is enough for me, for their suffrage is the only one to which I aspire. If, in order to obtain forgiveness for the evil I have done, I must confess myself ignorant, I have less reluctance to be seen as more guilty than foolish. I am dismayed, however, when I find that I have only become good because I can no longer be bad; but this dismay does not engender contempt. I love myself, I regret my youth, and I am angry to see myself on the edge of the ditch. " (1791 Preface, p. 1324-1325, continued from previous)

Self-satire was therefore merely an antidote to praise : self-esteem is at the root of the project. It's a question of communicating this esteem, this time no longer to the vast, abstract group of readers invoked in the previous paragraph, but to the more intimate group of " my equals " who are these equals ? Those who think like me ?; who lead the life I've led ?; who share my freedom of spirit ?

" Mes égaux " refers to a community with no real or concrete existence. Anyone, any reader can choose not to despise me, anyone can participate in the project.

The system of the imaginary community of equals is radically opposed to that of the confession, which takes an audience as witness before God, beats its breast and humiliates itself, puts its salvation at stake in the trial made of its existence. Casanova absolutely rejects this Rousseauist scene of judgment: he even overturns it (admittedly, by caricaturing it). Instead of looking foolish in front of his public, he shows himself to be witty in front of his equals, and too bad if this flattering portrait makes him look guilty. Confession is a self-abasement before its judges the autobiographical project of the Histoire de ma vie is an elevation of the reader to self-esteem.

You have to follow the balancing act of reasoning : I don't praise myself, but I satirize myself ; but I don't satirize myself to the point of making myself contemptible : the principle is that I'd rather come across as guilty than foolish. It's around this " rather than " that everything shifts (" to pass for more guilty than for sot "). Guilty here becomes pleasant, becomes flattering. This guilty portrait of me to which I elevate my readers, who have become my equals, is a flattering portrait that does well for me, ultimately my praise.

Casanova thus continues the destruction of the moral framework12 of the confession : not only does the guilty portrait of himself eulogize him, but without a qualm, the storyteller declares himself to have become " good ". He doesn't take any credit for this, but on the contrary, he's very sad old, he's become impotent and can no longer indulge in the erotic frolics of his youth. Virtue here only means decrepitude and the approach of death.

.

Not to write oneself, but to write life

This is where the reason for the autobiographical project comes in: writing restores youth to the old man, it prolongs self-esteem (" je m'aime "), it tells through adventure a love of self that is love of life : " je suis fâché de me voir sur le bord du fossé " ; writing conjures death by making, through storytelling, life possible once again.

This writing of conjuration speaks the love of life :

" I am far from despising life. What merit is there in despising a good we cannot keep ? What is contempt for something that is cherished, and that I must invincibly lose ? It's an expedient that one employs only out of cowardice. I know, and I feel, that I will die but I want it to happen in spite of myself : my consent would smell of suicide. " (p. 1325, continued from previous)

New move here. We saw above how Casanova slipped from " the reader " to " my equals " ; here, he moves from conjuring up self-contempt (" if I thought I was making myself despicable ", " mes égaux ne me mépriseront pas ", " cette consternation n'engendre pas le mépris ") to the conjuration of contempt for life. The shift is in fact the same: it's not the " me ", it's life that constitutes the center of the autobiographical project. The relationship between a self and an audience, with all that this implies in terms of constituting a literary genre, establishing a reading contract and structuring an argument, here becomes the constitution of a community of equals participating in the project of making life possible. The precious good is no longer the " me ", the judgment of the " me ", the salvation conditioned by this judgment, but life, the " cherished thing ", a good precarious by the death that borders it. The story conjures up the end of life. Through storytelling, " I want this to happen in spite of myself ". The story is /// a refused consent to death.

Life desubjectifies the narrative. In it, the reciting self communicates itself to the equals who listen and extend it. In the narrative, it is the labile nature of life (" a good that cannot be kept "), it is its evanescent flight (" a cherished thing... that invincibly I must lose ") that is precious. The narrative communicates this rhythm, this movement, which supplements for the old man the lost range of possibilities for enjoyment.

" My motto " : situation and flow

Since there is no book, there is strictly speaking no title. Casanova, on the other hand, was keen to place his project under the sign of a motto. In 1791 and 1794, this motto was borrowed from Seneca, volentem ducit, nolentem trahit, which can be glossed as : he who is docile, volentem, fate accompanies him, ducit, he who is rebellious, nolentem, it drags him along by force, trahit13.

In Seneca's formula, fata, fate, is the subject of both verbs. In Casanova,fata disappears, and by design. Casanova explains this very clearly in the 1797 preface : " The doctrine of the Stoics, and of any other sect on the force of Destiny is a chimera of the imagination, which holds to atheism. I am not only a monotheist, but a Christian fortified by philosophy, which has never spoiled anything" (p. 3) It's important to understand the implications of this profession of Christian faith, which the libertine Casanova reiterates several times in the Histoire de ma vie : for him, it's not a question of morality (" fortified by philosophy " means liberated from Christian morality), nor of the practice of piety (no confession, and the mass is a social practice put at the service of seduction), but precisely this elision of destiny in favor of trust in Providence (" I have always counted on His providence ", p. 4) : after prayer (which we hardly see at work in the narrative thread...), " man entrusts, and acts " (ibid.), he launches confidently into the flow of action.

Ducit, trahit refers to this flow of life in which I am caught volentem, nolentem, willingly or in spite of myself. Casanova describes himself, a few pages later, as " a man who let himself go, and whose great system was that of having none " (p. 1326) : if the " laisser aller ", the flow of life is not a system, neither is the subject's relationship to flow. So there is this flow, which the narrative mimics, and within this flow, a non-systematic series of choices, guided by a kind of magnetization of the living, by the call of pleasure, by the impulse of the moment : what presents itself, I choose it or I undergo it without any guiding principle, I accompany it or I resist it outside any overall structure of enchainment.

.

Once the structure of advocacy and the perspective of judgment disappear, another device comes into play, based on the tension between the situation the story brings and, in a given situation, the immersion volentem, nolentem in the flow or the resistance to the flow, the entrainment of the ducit or the disruption of the trahit. Making life possible through narrative presupposes the reduction of the nolentem to the volentem, the implementation of the acceptance of flow.

Casanova, in the wake of Leibniz, formulates this tension as the exercise of freedom on the one hand and insertion into a Providence on the other :

" By this motto Volentem ducit, nolentem trahit, I wish the reader to hear that willingly or unwillingly I can never have done anything other than what God willed. Since God is present in everything, always acting and never indifferent, is it possible for man to do anything contrary to his divine will? I don't think so, but /// in spite of this, I have always believed myself to be free in action [...]. If I hadn't found myself free a million times, I would never have convinced myself that I was a soul trapped in a body. When after action and examination I did not find myself free, I recognized that I was ill. [...] If I exist, then I have always existed, and I always will and as I do not know what I did before I was in the body in which I now find myself, I do not flatter myself that I will succeed in recognizing myself, when because of the dissolution of the body I animate I find myself enveloped in another matter, unless my naked spirit finds itself absorbed in God. " (p. 1319-1320)

We are struck by the paradoxically materialistic way in which Casanova represents Providence's action upon him, much less as God's will than as a Lucretian system of nature, acting upon a body. On this body, God manifests himself as a flow " always acting and never indifferent " : there is a metaphysical situation, which is that of " a soul enclosed in a body ", and there is an action of Providence, which frees this body and carries it into the flow of nature. The situation of the enclosed body is a disease, which even when it is a disease of the soul ultimately comes down to the corporeality of the suffering body. The situation is one of confinement in a body, the action is one of liberation from the body, by the body : such is the tension of the story and the condition of possibility of a poetics of the project in the History of my life.

.

The autobiographical project is carried by an acting, liberating body, whose liberating force is transferred from life to history, from action at the moment it is experienced to writing, which restores, extends, amplifies this liberating enjoyment of action. In this flow that writing feeds, life is essential. Speaking of himself in the third person, Casanova says: " he loves life like his soul " (p. 1321). Life is not to be understood here as the biographical content of a life, as the factual authenticity of the events actually experienced in a life, but as the living force of life, in which the protagonist comes to be inscribed, and whose word embraces the acting movement. Life is not a person, it is the life of the body, whose sensitive matter was arranged differently before, and will be recomposed differently after this existence. This is a far cry from the narcissistic focus on the "me" of confession. It also shows how little we care about the factual veracity of the events described...

The theater of possibilities

This economy of the writing project, which mimics and extends the flow of the living, not only ruins the moral structure and reading pact that organize the confession genre. Confession reconfigures the entire medium of performance. The theater of the world and of writing as representation of the world becomes the theater of life thought of as flux :

" It is a sorry duty to oblige an attentive spectator to leave a theater, where the very learned author God has a play performed, whose interesting varieties offer at every moment a plot, and a denouement, a beginning, and an end, dreadful catastrophes mingled with continual buffoonery, which temper the sadness, which the former should cause in the minds of the spectators, who in turn become actors, and where the incidents always surprise, despite the fact that they should have been foreseen, and where the philosopher himself finds himself pleasantly surprised, because he sees their novelty precisely in the fact that they are always the same. " (p. 1325)

The very formulation is dizzying, if only because of the mise en abyme on which it implicitly rests : Casanova compares himself in life to a spectator in a theater, but on the stage of this /// theater are also spectators, themselves confronted with a theater within the theater... This vertigo is not only that of the theater of the Baroque world and its structures of reversal. It mimics being drawn into the flow of life.

For the author does not describe himself, strictly speaking, in the theater ; he envisions the exit from the theater, as a metaphor for the exit from life. "It's a sorry duty to have to leave the theater of life, a theater in which you're a spectator only waiting your turn to move on to the stage, to become an actor. There is no division of stage and parterre, only suspensions and actions, trahit and ducit. Only the actors count, there is enjoyment only in life and in action : the exit from the theater, death, is what the story, the History of my life, comes to conjure.

The story does indeed seem to develop all the constituent elements of a play : God apparently puts on plays that tie up the beginning of a plot, that unravel that plot with " an end ", death, and that between these two terms stagger peripatetic events, painful (the " catastrophes ") or pleasurable (the " bouffonneries "). But Casanova's life, the story of his life, will not be one play it will be a set of " interesting varieties ", i.e. " at every moment " the possibility of a plot to be tied up ; in other words, a range of situations offering material for possible plays. From the theatrical structure of a poetics of narrative, we move on to a device for the aestheticization of life, i.e., to an apparatus of virtual enjoyments organized around a declension of nodal moments, from which to start, to continue life.

In this device, situations (what Casanova refers to as " instants ") trigger flows : the spectator then becomes an actor and produces an " interesting variety ", on the model of the Lucretian clinamen. The stage is demultiplied and virtualized, following the same movement and logic that disseminates the autobiographical self in a temporary, labile living.

.

In this theater of possibilities, the truth of actions, the authenticity of facts, the sincerity of narrative, are not the essential criteria of the story. Casanova's problem, the challenge of the History of my Life, is not to persuade (to establish a truth), but to interest. Yet, as Casanova explains, the mainspring of interest is precisely the seduction of possibilities :

" Pliny the Younger said to me gravely : If you don't do things worthy of being written, at least write things worthy of being read. This precept is a diamond of the first water polished in England ; but it is none of my business, for I write neither the life of an illustrious person, nor a novel. My subject is my story, and my story is my subject and I know that my life, which will interest many readers, would perhaps interest no one, if I had spent sixty years making it with a premeditated intention to write it. The wise will read my story when they know that it narrates facts, which the actor did not believe the day would come in which he would determine to publish them. " (p. 1326, repeated in a more condensed form in the 1797 preface, p. 7)

Aut facere scribenda, aut scribere legenda14 : Pliny the Younger's formula is taken from the famous letter to Tacitus in which he recounts the death of his uncle, the Pliny of the Natural History. Pliny the Elder had indeed just died during the eruption of Vesuvius that buried Pompeii, and Tacitus had asked the young man to tell him about it. Pliny the Younger then weighs up two ways of recommending himself to posterity: either as an actor in history, who has done things worthy of the name, or as an author, who has done things worthy of the name. /// to be written, or as a historian, who writes things worthy of being read : " worthy of " is one of the possible meanings of the Latin verbal adjective. If Tacitus reports the death of Pliny the Elder, himself famous for his books, as a historian, then the deceased will have been doubly favored by the gods.

Casanova rejects this model. He did not live his life " with the premeditated intention of writing it down " he did not live in order that his life might be written down, conditioning his life's actions by the prospect that one day it would be the subject of a book nor did he write his story in order that it might become a school : we've seen the meaning of Casanova's expression, " my story is a school of morals ", which refers to a textbook case, but in no way to the " to school " of an exemplary narrative, of a life that would have been reformatted to become a compendium of deeds commending their author to posterity. Casanova here accentuates and, as it were, forces the meaning of Pliny's verbal adjectives, scribenda and legenda, which he is still glossing : " avec un dessein prémédité de " denudes the intention value of the Latin verbal adjective, which remained attenuated, concealed in the translation by " dignes de ". History, in Pliny's model, becomes the final cause of life, and posterity - the final cause of history.

What is Pliny's precept worth? It's " a diamond of the first water ", i.e. of the purest transparency, " brilliant in England ", cut for the British crown jewels that make up the world's most fabulous diamond collection15. In other words, this percept has nothing to do with common life, with the living of real life, which is not transparent, which is badly cut and which belongs to no treasure.

Casanova then substitutes Pliny's chiasmus with another, in which the matter of life is the pivotal element : " my matter is my story, and my story is my matter ". It's not diamond, it's matter the sheer material flow of life (not an illustrious man's life, or the novel of a life) is matter to my story, while my story is not written for the ideal audience of posterity, but as matter to live, as an extension of my life.

It is this matter that will interest readers, because Casanova's life did not obey a " premeditated design " : the design is the Aristotelian form of the historia, the plot, with its system (moral, poetic, providential). It's matter, it's facts, not produced for publication : facts caught in the flow of life, facts that only take on value in being written down because a priori they were not inscribable.

Remember the simplicity of the terms Casanova uses to define his project : it's " mon histoire ", a neutral term that can designate both the life lived, the referent, and the writing of life, the written text. What is this story about? Of a " life that will interest ", we couldn't more vaguely formulate the content, which is also referred to as " matter " and " facts ", that is, content that nothing delimits, structures, circumscribes.

L'intérêt du tableau : the autobiographical project is an aesthetic project

Is this story, however, the antithesis of Crown diamonds, that of the random variety of a life that nothing illustrates ? How then can it interest ?

" I will be accused of being too much of a painter where I narrate several exploits of love. That's what my cynicism consists in but this criticism will only be fair if I'm found to be a bad painter. It will be said that /// I circumstantiate these facts in such a way that I seem to enjoy remembering them. You guessed it. I agree that the memory of my past pleasures renews them in my old soul: I am then delighted to convince myself that they are not vanities, since my memory shows me their reality. But the critic insists, and tells me that my overly lewd descriptions may inflame the reader's fantasy. That's what I want. It's a service I claim to render him, for I don't suppose a reader is an enemy of himself. Besides, isn't it true that a writer's job is to interest? Am I to be condemned, then, if I fulfill my task ? I can only be criticized if I am convinced that I have written badly, and to be criticized it will suffice for me to know that I am not interesting " (p. 1328)

What makes the Histoire de ma vie interesting, by its author's own admission, are the licentious paintings with which it provides its reader's fantasy. Casanova claims both their lewdness (" my descriptions are too lewd ") and his cynicism (" that's what my cynicism consists of "). What interests the reader is the amoral eroticism of these paintings, which Casanova " circumstantiates " with complacency : he doesn't just describe, he circumstantiates, he produces circumstantiated descriptions, where bodies, gestures, acts are shown without false modesty. It's the explicitness of situations that interests the reader, it's for flesh and sex that he's read.

Very clearly, very deliberately, the erotic interest of the paintings replaces the rhetoric of truth persuasion and exemplary illustration. This interest is achieved by aestheticizing the autobiographical project: subject to the reader's criticism (" the critic insists ", " I cannot be criticized "), the Hstory of my life will be evaluated by him not as a life (possibly morally condemnable), but as a story, as the work of a writer doing his office (" the function of a writer is to interest "), demonstrating a quality of writing : " I can only be criticized when convinced that I have written badly ".

The value of text is assessed by its style, not by the exemplarity of its content. Style itself is not thought of as pure form, but as an interest trap. Style is the aesthetic criterion for validating the narrative: aestheticizing the story, circumstantiating the tableaux, establishes sensitive contact with the reader, communicating sensation, aisthesis. And the most powerful sensation is the erotic one of " the pleasures that love has brought ", of " the intoxication of love ". Style, interest and lechery are the new aesthetic economy of writing, whose exclusive criterion will henceforth be the reader's interest: by aestheticizing itself, writing is constituted as a self-aware literature, i.e. as a literary field and a writer's craft. Casanova capitalizes on a memory from which he produces the added value of writing. This value is measured by the interest of the reader, who buys or doesn't buy the story, who follows or doesn't follow it, who asks for more or doesn't ask for more.

" For I do not suppose a reader to be an enemy of himself " : through the product that the writer delivers to him, the reader pleases himself, this is the fundamental aesthetic spring of literature that has become self-conscious. It is also the mainspring of capitalism.

The motto of 1797

In the 1797 preface, Casanova deletes the 1791 motto, which he had maintained in 1794, and replaces it with a quotation he attributes to Cicero and which is in fact by Erasmus : Nequicquam sapit qui sibi non sapit. We provisionally translate : he is wise in vain who is not wise for himself. This motto echoes for us /// to that which Kant assigns to the Enlightenment, sapere aude, dare to know. Sapere means first of all to have taste, and hence to exercise judgment. It's clear what we're talking about in Kantian vocabulary this is neither wisdom of experience, nor the accumulation of knowledge sapere refers more precisely to the faculty of judging (Urteilskraft), of critically exercising one's judgment. Enlightenment, for Kant, is the effort of man whose mind has come of age and freely exercises judgment.

Let's turn now to Casanova. We understand that there is no question of wisdom here. Casanova is talking about his reader, and indeed it is to his reader that his first sentence is addressed. The reader exercises his taste and judgment, sapit, the text of the History of my life is subject to the sapit of its reader, whom it is therefore a question, for this judgment to be positive, of interesting. The reader must taste the story, appreciate its flavor, and to do this he must find his interest in it : this is the meaning of sibi. It's for nothing, in vain, that the reader cconsumes, if it's not for him that he does it, if he doesn't find his account in doing it, if he's not interested in doing it. We must link this motto to the formula in the Preface of 1791, " I do not suppose a reader to be an enemy of himself " : to criticize well, you must first love yourself, and through this love of yourself, take pleasure in what you read. The taste, the flavor, the consumption of sapit only make sense sibi, for oneself, if it's to please oneself

.

The new motto accomplishes and radicalizes the project logic that replaces a poetics of genre in the History of my life. The project projects the story entirely towards the reader it is intended to interest. The narrative device is developed from this interest, which it is a question of seducing.

Notes

Access to the beginning of the manuscript of volume III : https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6000856t/f10.image.

///

See Histoire de ma vie, ed. Igalens-Leborgne, II, 1133-1180. This edition is now abbreviated Laffont2013.

G. Casanova, Soliloquy of a Thinker, Allia, 1998. https://books.google.fr/books?id=qKNtoKSo8Z8C

Laffont2013, I, 1353-1488.

Since 2010, it has been kept in the Bnf's manuscript department. See Marie-Laure Pérvost's presentation of the manuscript and its history, https://gallica.bnf.fr/essentiels/casanova/histoire-vie/manuscrit.

Laffont2013, I, 1318-1330.

Laffont2013, I, 1331-1335.

Laffont2013, I, 3-19.

Philippe Lejeune, Le Pacte autobiographique, Paris, Seuil, 1975.

This is what Raphaëlle Brin attempts to do in Ellipse's volume devoted to the 2021 agrégation program. See " Retour sur une trajectoire littéraire ", p. 277-283.

Similarly, in the Preface of 1797 : " the only system I had was to let myself go where the wind that blew pushed me " (p. 5). Compare with Casanova's reflections on Miss XCV, in love with an imaginary "phœnix ": " This story confirmed me in my system. Our most decisive actions in life depend on very slight causes. [...] Everything is a combination, and we are the authors of facts of which we are not accomplices. All the most important things that happen to us in the world are simply things that must happen to us. We are but hanging atoms, who go where the wind blows them. " (Histoire de ma vie, IV, 6, ed. Igalens-Leborgne, t. 2, p. 179)

See Marie-Françoise Luna, Casanova mémorialiste, Champion, 1998, p. 276-277.

We must therefore pay attention to the expression Casanova uses later, " mon histoire est une école de morale " (p.1326) this in no way means that the History of my life is moral, or that it is an edifying, exemplary story that provides moral instruction. École must be understood here as a textbook case that can give " food for thought " to the wise, i.e. to those who know that in " the vicissitudes of life " one never acts out of prudence. In other words, the only lesson to be learned is that there is no lesson to be learned...

Casanova condenses a formula from a letter from Seneca to Lucilius : " Ducunt volentem fata, nolentem trahunt " (letter 107, §11). Drawing on Cicero's example, Seneca here translates into verse a prayer to Jupiter he found in the Greek Stoic Cleanthe : " O Father, O King of the heavenly heights, lead me where thou hast willed. I obey without hesitation. I bring you my valour. Shall I shrink back? Then I'll walk in your ways moaning. Cowardly heart, I will suffer what a beautiful soul would have accomplished. The fates lead a docile will they drag along that which resists. " (Seneca, Letters to Lucilius, trans. Henri Noblot, Les Belles Lettres, 1971, t. IV, p. 176-177). The prayer opens with the imperative Duc, lead me, and closes with the verb ducunt, the fates lead. Casanova writes from the castle of Dux, and builds himself a Stoic motto from the castle.

Pliny the Younger, Letters, VI, 16, 3.

I don't think Casanova is mocking the English diamond cutters here as being less competent than the Antwerp ones (ed. Igalens-Leborgne, note 4 on p. 7). This makes no sense in context " brillanté en Angleterre " is not opposed to " de la meilleure eau " but rather outbids it.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Le projet autobiographique », Casanova, la séduction des possibles, cours d'agrégation donné à l'université d'Aix-Marseille durant l'année 2020-2021.

Casanova

Archive mise à jour depuis 2020