Ambiguity of the word

What exactly does nature designate in the expression " state of nature ", from which the whole demonstration of the second discourse is woven? Rousseau explicitly refers to a double tradition : the recent one, well marked out by critics, of the jusnaturalists and the philosophy of right1 ; but also the older, and less noticed, one of scholasticism and theologians :

" It has not even occurred to most of our people [= our French philosophers] to doubt that the State of Nature existed, while it is obvious from reading the Sacred Books that the first Man, having immediately received light and Precepts from God, was not himself in this state, and that by adding to the Writings of Moses the faith which every Christian Philosopher owes them, it must be denied that, even before the Deluge, Men were ever in the pure state of Nature, unless they fell back into it by some extraordinary Event. " (p. 1322)

From the state of nature, understood as the state of man in nature, and opposing the state of man in society, Rousseau slipped towards the pure state of nature, which refers to the status purae naturae found in commentators on Thomas Aquinas, Cajetan, Suarès and above all Jansen, who places this notion at the heart of the Augustinus. The purely hypothetical character of the pure state of nature, from which man has at once slipped into a corrupt state of nature, status naturae lapsae, comes from scholasticism ; and the mode of reasoning which consists in making a hypothetical, unreal category work, in order to deduce from it a certain organization, disposition of reality, is a mode of scholastic reasoning.

What does nature designate in the theological expression of the " state of nature " ? It's not about the spectacle of nature, nor about Nature as the organizing principle of the world, but about a state of nature of man, of man's original nature, of what man is in nature :

" Religion [...] does not forbid us to form conjectures drawn from the mere nature of man and the Beings that surround him, as to what might have become of the Genre-humain, had he remained left to himself. " (p. 1333)

This abandonment is the abandonment of man without God, it is the hypothesis of a purely logical development of man, without Providence, a hypothesis that must be made in order, by difference with the Christian reality we observe, to establish the intervention of God, grace : to the theological status naturae is opposed the status gratiae, to which Rousseau makes very slight reference here, taking up, without its content, the structure and model of reasoning, as Hobbes had already done before him4.

Nature, then, does not designate the world, a certain state of the world in which we would have to imagine the first men ; nature is a logical category, just as we distinguish in grammar between nature and the function of a noun, as Rousseau will discuss, at the end of the second discourse, " la Nature du Pacte fondamental de tout Gouvernement " (p. 184), " la Nature du Contract " (p. 185). Nature is an abstract operative instrument that refers to an unreal origin, which must be assumed, but which cannot be represented :

" Finally all, speaking incessantly of need, greed, oppression, desires, and pride, transported to the state of Nature ideas they had taken from society. They spoke of Wild Man, and painted Civil Man. [...] We mustn't take the researches into which we can enter on this subject to be mere /// historical truths, but only for hypothetical and conditional reasonings ; more apt to clarify the Nature of things, than to show their true origin, and similar to those our Physicists make every day on the formation of the World. " (p. 132-3)

Here we touch on the properly literary subtlety of the Discourse, which doesn't simply reject one mode of reasoning in favor of another, but superimposes one on the other and starts from this " paradox highly embarrassing to defend " to build the representation of its object from this logical impossibility.

On the one hand, then, the state of nature taken as a moral spectacle of human passions (need, greed, oppression... on the other, the nature of things, which is clarified by the hypothesis of the state of nature, can be seen on condition that the hypothesis that makes it intelligible is maintained to the end as a logical impossibility.

" They spoke of wild man, and they painted civil man " : when discourse turns to painting, when it gives to see, it is our humanity, our theater of the world that we see, in a false setting of nature. We cannot " show the true origin " : the nature of the state of nature can only be grasped in the indirect loop of " hypothetical and conditional reasoning ". It cannot be seen, it cannot be staged: to dramatize nature is to project our world onto it. On one side, then, a theatrical, scenic space, where we are, in the worldly actuality of the world ; on the other, an abstract, logical, intelligible and non-visible space, a nature of things that would take the place of origin in the absence of the impossible-to-think true origin in other words, a supplement of origin that would model itself as the reverse of the world stage, that is, as a space of invisibility.

.Impossibility of the gaze

This space, we do not see it, we cannot see it, and at the same time we are summoned to represent it to ourselves : " how will man manage to see himself as Nature has formed him " (p. 122), asks Rousseau in the Preface ? But he immediately points out that this vision is impossible : " Que mes Lecteurs ne s'imaginent donc que j'ose me flatterer d'avoir vû ce qui paroit si difficile à voir. " (p. 123) The aim, then, is to replace vision with an indirect method, involving " reasoning " and " conjecture ", to determine " what experiments would be necessary to arrive at knowledge of the natural man "5.

This method is defined by difference from reading :

" Leaving therefore all scientific books which teach us only to see men as they have made themselves, and meditating on the first and simplest operations of the human Soul, I believe I apperceive there two principles anterior to reason... " (p. 125-6)

To what the reading of scientific books gives us to see, the theater of the current human condition, is opposed inner meditation, a gaze turned inward (the requirement for man to come " to the end of seeing himself as nature has formed him "), which believes it glimpses " two principles anterior to reason ". Looking inwards, breaking through the envelopes of reason (the disfigurements of the statue of Glaucus, p.122, the successive developments by which reason "has come to stifle Nature ", p.126), allows us to glimpse, by breaking in, an invisible below, a place where principles are buried. This place cannot be read, cannot be given to be read.

Unless there's another /// book :

" O Man, from whatever Country you are, whatever your opinions, listen ; here is your story as I thought I read it, not in the Books of your fellow men who are liars, but in Nature which never lies. " (p. 133)

This now defines nature as space, not as a pure category, a space if not visible, spectacular, at least legible and conjecturable. A space that would take the place of a book, that would make up for its impossibility.

In this space, Rousseau begins by refusing to describe man; this is the beginning of the First Part of the second Discourse :

" I will not follow his organization through his successive developpemens : I will not stop to investigate in the animal System what it may have been in the beginning [...] ; I will not examine, whether, as Aristotle thinks, its elongated nails were not at first hooked claws " (p.134)

Nature is a space of invisibility that Rousseau solemnly marks as not to be seen origin cannot be looked at better still, the examination of nature necessarily first passes through the solemn denial of an origin that would be visible, through the proclaimed impossibility of a spectacle of original nature.

We must give up seeing original man, for original man is not endowed with the gaze : because he walks on all fours, " his gazes directed towards the earth, and limited to a horizon of a few paces " mark " both the character, and the limits of his ideas ". Yet this embryo of description is only introduced through a double negation :

" I will examine not [...] if walking on four feet, his eyes directed towards the Earth, and limited to a horizon of a few steps, ne mark point both the character, and the limits of his ideas. " (ibid.)

To this bounded horizon which prevents the man of the state of nature from seeing, and which from our world we cannot see, a space on which we can only form " vague, and almost imaginary conjectures ", is opposed Rousseau's hypothesis, boldly advanced as a false hypothesis, an origin of convention, a visibility of substitute :

" I shall suppose him [the = man] conformed from all times, as I see him today, walking on two feet, using his hands as we do ours, bearing his gaze on all Nature, and measuring with his eyes the vast expanse of Heaven. " (ibid.)

Emerges, finally, the spectacle of Nature. Man measuring the vast expanse of the sky with his eyes, thus drawing, delimiting the space of his visibility, contrasts with the original quadruped whose dismayed, bounded gaze delimited only the emptiness of his ideas. The spectacle of nature is necessary to think the state of nature ; but it is impossible, both because we project it from our corrupted humanity and because the man of nature could not see it.

." His imagination paints nothing for him [...]. The spectacle of Nature becomes indifferent to him, by dint of becoming familiar. [...] he does not have the spirit to be astonished by the greatest marvels ; and it is not with him that we must seek the Philosophy which man needs, to know how to observe once what he has seen every day. " (p. 144)

It would be necessary to be able to observe what the natural man saw. But the natural man was not aware of seeing anything. We must therefore substitute a hypothetical man, " conforming to all times ", capable of observing a spectacle which, for the man of nature, was not a spectacle.

Further on, Rousseau evokes Mandeville and his fable of the Bees. Mandeville provides him with a figure of this original gaze /// impossible :

" the pathetic image of a man locked up who appercepts outside a ferocious Beast tearing a Child from his Mother's womb, breaking under its murderous tooth the feeble limbs, and tearing with its nails the palpitating entrails of this Child. What terrible agitation does this witness of an event in which he takes no personal interest feel? What anguish does he not suffer at this very moment, not being able to bring any help to the fainting Mother, nor to the expiring Child6 ?

Such is the pure movement of Nature, anterior to all reflection " (p. 154-5)

The parable, found in a book, delivers an image for this principle of pity that with self-love Rousseau from the beginning of the second Discourse thought he glimpsed after forsaking all books... We see clearly that thought always obeys a double constraint and deliberately superimposes two contradictory models of conceptualization : the demand for visibility and the affirmation of invisibility; the proclaimed and denied use of conjecture for this conjecture, the model of books and reading, and the proscription of such a model. Mandeville's parable articulates this double movement.

In it, man in the state of nature is identified with an enclosed man who, from his dungeon, witnesses a spectacle in which he cannot intervene : on the one hand, then, an offered, open stage, a vague theater of the world ; on the other, the inaccessible, closed, circumscribed space of original nature, identified with a kind of Platonic cave. This space is not the site of the action; it's merely a point of view directed outside this space, towards the object of the representation, the child devoured by the lion. Not only is the prisoner unable to get out, but " he takes no personal interest " in what he sees : between the show and him, there is no relation.

We can't describe the state of nature, the inside of the dungeon. Or rather, that's not the point. It's no longer a question here of the " pure state of nature ", but of the " pure movement of nature ", i.e. not of describing the inside of the dungeon, but of giving an account of what carries the prisoner towards this external spectacle which is nonetheless a priori totally foreign to him. Nature's space of invisibility is the place where the gaze originates : but the birth of the gaze projects the beholder out of nature, into the movement of history, towards social horror. The emergence of visibility prepares for denaturation and corruption.

.The emergence of visibility

The starting point of the second part of the Discourse is a gesture of closure :

" The first who, having enclosed a piece of land, ventured to say, this is mine, and found people assés simples to believe it, was the true founder of civil society. " (p. 164)

Beyond the symbolic and philosophical significance of this gesture, which identifies the state of society with a state of property, this transformation of man's relationship to space plays a decisive role in the transition from the invisibility of nature to the visibility of society7. A man delimits a space, settles in and utters a speech, This is mine, in front of spectators, " people simple enough to believe ", to whom this property, this stage, is now off-limits. The foundation of society is the foundation of a scenic space civil organization is a theatrical organization.

At the same time, the process of conceptualization, hitherto marked by the impossibility of looking, the labor and tension of conjecture, radically changes model : a point of view is constituted, faced with a painting /// visible.

" Let us therefore take things from higher up and try to gather under a single point of view this slow succession of events and connoissances, in their most natural order. " (ibid.)

While the philosopher gathers, reunites, orders the figures of a social scene that he will thus be able to make visible, the very historical process of constituting societies is described as a process of gathering, circumscription, binding, which stands in contrast to the generalized dissemination that characterized the state of nature. In the state of nature, men are " dispersed " (p. 135), they live " dispersed among the animals " (p. 136), " and as there was almost no other way of finding each other than not to lose sight of each other, they soon came to the point of not even recognizing each other " (p.147) dissemination is an essential characteristic of the space of invisibility, constituted in relation to the state of society and property like vague space in relation to the restricted space of the classical pictorial scene. When society emerges in nature, the gaze is constituted from nature towards this scenic delimitation of a civil organization, like the helpless gaze of the prisoner towards the lion devouring the child, or the dumbfounded gaze of wild men before the one who first, delimiting his land, dared to say This is mine.

Society emerges through delimitation, but also through gathering, the reunion of individuals : it's " the effect of a new situation which brought together in a common dwelling husbands and wives, Fathers and Children " (p. 168) it's now " men thus brought together, and forced to live together " (p. 169) ; they " slowly draw closer together, come together in various troops " (ibid.) ; dispersion is succeeded by liaison, " some liaison between various families " (ibid.), " liaisons extend and bonds tighten " (ibid.).

The story is a synthetic, and hence scenic, ordering of what nature offered in a dispersed way :

" Things having reached this point, it's easy to imagine the rest. [...] I shall confine myself only to glancing at the Genre-humain placed in this new order of things. " (p. 174)

This ease of the glance is opposed by the deception and impossibilities in which conjectures about the state of nature strayed. The philosopher's gaze can be exercised here, at the very moment when the gathering of men, their connections, introduces the gaze into the heart of the civil community. It is first and foremost the gaze on oneself, which degenerates self-love into self-love:

" Thus it was that the first glance he cast upon himself, produced there the first movement of pride ; thus it was that scarcely knowing how to distinguish ranks, and contemplating himself in the first by his species, he prepared himself from afar to claim it by his individual. " (p. 166)

The gaze is the split, which divides being and appearing, thereby introducing the theatrical play of worldliness into the world, and through this play the ferment of corruption :

" Everyone began to look at others and to want to be looked at himself [...] ; and the fermentation caused by these new leavens finally produced compounds fatal to happiness and innocence. " (p. 170)

From then on, along with society itself, the gaze will degenerate and precipitate the social state towards a return to the invisibility of nature. Rousseau speaks of a circle, of this " extreme point which closes the Circle and touches the point from which we started " (p. 191).

Panoptic vision and blinded vision

However, this is not exactly a return to the situation at the beginning of the Second World War. /// discourse : the blindness of enslaved and corrupted men, " the eyes of the People [...] fascinated " by their leaders (p.188), are themselves, in the eyes of the wise man, "a few great Cosmopolitan Souls, who cross the imaginary barriers that separate Peoples, and who, following the example of the sovereign being who created them, embrace the whole human race in their benevolence" (p. 178). The false, divided, blinded vision is itself caught up in a larger device, as a piece in the conceptual picture that is being scaffolded, around the love of freedom.

" Politicians make the same sophisms about the love of liberty that the Philosophers made about the State of Nature ; by the things they see they judge very different things they have not seen and they attribute to men a natural inclination to servitude by the patience with which those they have before their eyes bear theirs " (p. 181)

Faced with the love of liberty, which arises within the state of society as a demand for a return to nature, Rousseau finds the same blindness of the philosophers he had denounced, at the beginning of the second discourse, faced with the state of nature. It's the same transposition of the lure they see around them into a situation, a state that has nothing to do with that lure. In appearance, then, the circle is complete: the social tableau is blurred, and the scissionary effect of its visibility returns the space of representation to its original dissemination.

.However, the very parallel of the love of liberty and the state of nature introduces a new device : the love of liberty is not a state, but a movement from the civil state to nature, that is, from the social, actual and visible space, the means of seeing this state of nature stricken with invisibility and marked by the original paradox. The love of freedom does not reproduce the original invisibility, but makes a tableau towards this invisibility, and thereby, indirectly, makes it visible.

" As an untamed steed bristles its manes, strikes the earth with its foot and struggles impetuously at the mere approach of the bit, while a trained horse patiently suffers the rod and the spur, barbarian man does not bend his head to the yoke that civilized man wears without a murmur, and he prefers the stormiest freedom to quiet subjection. " (ibid.)

The revolt of the barbarian who refuses civilization is incomprehensible to politicians, who assess his nature, his conduct, by the yardstick of what they see, i.e. civilized, enslaved, bastardized peoples. The rebellious barbarian emerges in the social space as a symptom of the state of nature, a priori incomprehensible, insemiotizable. To make it visible, Rousseau resorts to the subterfuge of culture, which provides him with the image that the asepsis of a corrupt world could not provide : the double epic metaphor of the untamed steed and the trained horse introduces, into the sphere of the visible, the difference between the two states, and thus makes the state of nature visible from the state of society into which it introduces protest and revolt, the demand for freedom. This double image should not, however, lead us into a conceptual juxtaposition: in the trained horse we see the untamed steed, in civilized man - the original barbarian, and in the statue eroded by the sea - the primitive Glaucus. The state of society is a screen for the philosopher's eye to the state of nature, a screen that not only envelops it in such a way as to render it invisible, but corrodes it, corrupts it, disfigures it8.

The emergence of visibility then occurs only through the intelligibility of this superposition, which allows us to conjecture, through the exercise of philosophical indignation, the beyond of nature from the social symptom. In this way, another eye is revealed than the luring and deluded one of moralists and politicians, /// un œil révolté :

" but when I see others sacrificing pleasures, rest, wealth, power and life itself to the preservation of that one good so disdained by those who have lost it [= freedom] ; when I see Animals born free and abhorring captivity break their heads against the bars of their prison, when I see multitudes of naked Savages despise European voluptures and brave hunger, fire, iron and death to retain only their independence, I feel that it is not for Slaves to reason about freedom. " (p. 181-2)

What Rousseau sees is incomprehensible, and Rousseau himself sees it only at the cost of his own exclusion from the civil community, which he denounces as a community of slaves. For the reader, these unseemly, nonsensical pictures become visible only in the movement of Rousseau's revolt, which is a movement, an escape to nature. Rousseau still has the social gaze at his disposal, but frees himself from the lures that this gaze induces from nature; he has not yet left the social sphere of the visible, but is already sufficiently detached from it to bring into play the scissionist difference, which is represented by the metaphor of the two horses.

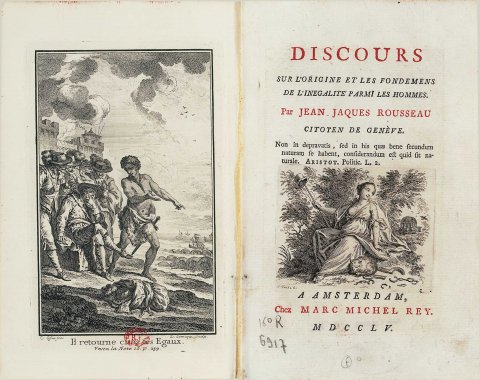

Frontispiece and first page of Discourse on the origin of inequality, first edition, Amsterdam, Rey, 1755, engraving by Sornique after Eisen. Bnf 16-R6917.

This makes it easier to understand the choice of the 1755 frontispiece engraving, executed by Sornique after a drawing by Eisen. Eisen refers to an obscure anecdote from the Histoire des voyages collated by Prévost and reported at the end of the first and longest of the three notes in the second part. At the end of the seventeenth century, the governor of the Cape, Simon van der Stel, adopted a young Hottentot savage, had him richly dressed, instructed in several languages, and traveled to the Indies. On his return, the young man visits some of his parents' Hottentots:

." he took it upon himself to strip off his European finery to dress in a Sheepskin. He returned to the Fort, in this new adjustment, loaded with a pacquet that contained his old clothes, and presenting them to the Governor he gave him this speech* : Have the goodness, Sir, to take care that I renounce for ever this device. I also renounce for all my life the Christian Religion, my resolution is to live and die in the Religion, manners and usages of my Ancestors. The only grace I ask is that you leave me the Necklace and Cutlass I wear. I will keep them for the love of you. So without waiting for Van der Stel's reply, he fled and was never seen again in Cape Town. Histoire des voyages, Tome 5, p. 175. " (Note XVI, p. 221)

Engraving by Delignon after Moreau le Jeune for the Discourse on the origin of inequality, in Rousseau, Œuvres, Paris, Didot-Bozerian, 1801. Coll. part.

In the foreground, the pile of clothing that the Hottentot has come to return makes a symptom, both as the remains of civilization and the movement of a return to nature. Above, the young man dressed in sheep's skin /// points to the discarded garments with his right arm, to accompany his speech, and with his left hand to the shore, the wave of the sea populated by boats as a point of escape and return. On the left, sitting in front of his advisors in hats, who are watching for his reaction, Van der Stel meditates. In the background on the left, clouds gather over the Dutch fort.

In the space of the representation, there is no room for nature, even as the Hottentot demands, for the love of freedom, a return to the state of nature where his people live. The pile of clothes, the governor and his advisors assembled as spectators of the scene the young man makes for them, the fort, the boats - all the elements that surround him inscribe him in the civil society he claims to be fleeing. Even the vague space of the sea is criss-crossed by Dutch ships. The movement alone of his flight, and the liminal stripping of his clothes at the threshold of the stage space, designate the space of nature's invisibility. In Moreau le Jeune's version, the vague space is populated by Hottentots, but busy with the work of the Dutch. In Marillier's version, the emphasis is on the young man's flight, as he passes the pile of clothes. But turned towards his interlocutors in an operatic dancer's pose, he seems destined never to escape. To think about and represent this anthropological space of nature, we'll have to break with the classical scenographic framework of its representation.

Notes

///See Robert Derathé, Jean-Jacques Rousseau et la science politique de son temps, Vrin, 1979, and Victor Goldschmidt, Anthropologie et politique. Les principes du système de Rousseau, Vrin, 1974, especially p. 217sq.

References are given in Jean Starobinski's edition of Œuvres complètes, t. III, " Écrits politiques ", Gallimard, Pléiade, 1964.

Jean Starobinski here refers in note to Suarez (De Gratia, Prol. 4, c. 1, n. 2), who himself cites Cajetan.

Yves-Charles Zarka, Hobbes et la pensée politique moderne, PUF, 1995, 2000.

Jean Starobinski has shown the ban on the gaze in Les Confessions (L'Œil vivant, Gallimard, 1961, p. 93sq). Is this autobiographical prohibition of desire objectified here in a philosophical formulation, or, on the contrary, is a certain theological-political device, through which Rousseau thinks nature, projected in The Confessions as a prohibition of the gaze ?

Should we relate this image to that of the frontispiece engraving of the Lettre sur les sourds, which Diderot had published in 1751 ?

On the second nature of scenic visibility in Rousseau, see Jean-Christophe Sampieri's analysis of Chapter I of the Essai sur l'origine des langues, in Résistances de l'image, PENS, TIGRE, 1992, pp.225-244, and in particular p.231.

See J. Starobinski's analysis of the Glaucus myth in La Transparence et l'obstacle, Gallimard, 1971, Tel, p. 27sq.

See the frontispiece.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « La nature comme espace d’invisibilité », communication prononcée au Colloque Jean-Jacques Rousseau : nature et culture au fondement des sciences humaines et sociales, Université Paris-Descartes/New York University, 21-22 mai 2012. Cette communication a été publiée en anglais, sous le titre « Nature as a Blind Space », Rousseau between Nature and Culture. Philosophy, Literature and Politics, dir. Anne Deneys-Tunney et Yves Charles Zarka, De Gruyter, coll. Culture & Conflict, 2016 , p. 45-56.

Rousseau

Archive mise à jour depuis 2001

Rousseau

Les Confessions

Julie, le modèle et l'interdit (La Nouvelle Héloïse)

Le charme désuet de Julie

Julie, le savoir du maître

Passion, morale et politique : généalogie du discours de La Nouvelle Héloïse

L'économie politique de Clarens

Saint-Preux dans la montagne

La mort de Julie

La confiance des belles âmes, de Paméla à Julie

Politique de Rousseau

La nature comme espace d'invisibilité

Entre prison et retraite : Rousseau juge de Jean-Jacques

L'article Economie politique