The telescoping of differences

We might think a priori that the construction of a poetics, the reflection on a poetics of representation inevitably leads to the establishment of divisions. Division seems to be the theoretical operator of all poetics, as the opening paragraphs of Aristotle's Poetics indicate:

"Epic and tragic poetry, as also comedy, the art of dithyramb, and, for the most part, that of the flute and the zither all have this in common that they are representations. But there are differences between them of three kinds (διαφέρουσι δὲ ἀλλήλων τρισίν): either they represent by other means, or they represent other objects, or they represent otherwise, that is, according to modes that are not the same." (trans. Dupont-Roc and Lallot, 47a 14-19.)

ἤ γὰρ τῷ ἐν ἑτέροις μιμεῖσθαι, ἤ τῷ ἑτερως : poetics manages the heterogeneous; positing the difference of media (ἐν ἑτέροις), objects (ἕτερα) and genres (ἑτέρως) of representation, it fixes hierarchies, institutes categories, and thus brings back, within each of them, an order, an identity whose laws of operation it fixes, by difference with other categories.

Narratology is the direct heir to this differential mode of thought: within a discipline delimited by the medium "text", it differentiates, according to the type of object the text deals with, genres of literature1, and then, within each genre, modalities of expression. We'll differentiate between the novel, whose subject is the real, the real world, lyric poetry, which deals with the soul, the intimacy of the subject, and tragedy, whose representation is ideal and aims at the unreal and absolute values of nobility. Then, within the novel for example, narratology distinguishes narrative genres2, and differentiates narration, which represents events by unfolding their succession, from description, which on the contrary stops time and unfolds a visual tableau in space, or discourse, which, outside time and space, logically and argumentatively links together the logic of the world it represents.

This mode of analysis constitutes the familiar framework of literary studies, and provides them with the apparently most assured and well-tested methodological tools. Yet in the case before us today, the study of Diderot's Salons and the poetics Diderot implements in them, it proves totally ineffective. Not that Diderot, in the very heart of the Salons, didn't think long and hard about the problems of poetics he faced: but we have to admit that it was absolutely not through a differential game that he thought them through, let alone solved them.

"It seems to me that there are as many kinds of painting as there are kinds of poetry: but this is a superfluous division." (Essais, chap. V, p. 505/653.)

The superimposition, indeed the amalgam of all the categories that the Aristotelian tradition is careful to distinguish constitutes, on the contrary, the basic principle of his thinking.

I. Poetics of the painting

Thus, the distinction in the Salons between the medium and the level of representation, between the painted picture on the one hand, and the text that reports on it on the other, would seem to us a priori a basic methodological presupposition. From this distinction, which shares artists on the one hand, Diderot the art critic on the other, follows a second differentiation, internal this time, and sharing Diderotian activity: it would be appropriate to distinguish between his reflection on the way painters compose and order their paintings and the way Diderot gives an account of the same paintings in the Salons. We would then oppose a theory, the elaboration of a poetics of the painting on the one hand, and a practice, the implementation of a poetics of description on the other. This practice itself requires reflection and legitimization.

"Producing our titles": legitimation as a lure

When Diderot announces, at the end of the Salon de 1765, that he is going to legitimize his enterprise and his critical stance with a treatise, it is not the treatise that, in all poetic logic, we might expect him to propose to his readers of the Correspondance littéraire :

"After having described and judged four to five hundred paintings, let us finish by producing our titles; we owe this satisfaction to the artists we have mistreated, we owe it to the people for whom these sheets are intended; it is perhaps a means of softening the harsh criticism we have made of several productions, that of frankly exposing the reasons for confidence one may have in our judgments. For this purpose we shall dare to give a little Traité de peinture, and speak in our own way and according to the measure of our knowledge of drawing, color, manner, chiaroscuro, expression and composition." (P. 466.)

Diderot announces that he will produce his titles, but what titles exactly, he will never say. Are we to understand that the Essais sur la peinture have the function of legitimizing Diderot's competence as an art critic? But, since we're dealing with the description and judgment of four to five hundred paintings, and not directly with their production, this competence should be above all rhetorical, and define the modalities of description and the criteria of judgment. Instead, Diderot proposes a Traité de peinture, i.e. literally a poetics of artistic creation, implicitly identifying his critical activity with the activity of the painters he has reported on: because he too is a painter4, his judgments can be trusted. At no point will there be any question of Diderot's critical skills, as he claims to expound here not a theory, but an experience of painting, as if he were a painter, "in our own way and according to the measure of our knowledge". This is why the Traité announced will become Essais, the systematic exposition being replaced by a kind of introduction to the very process of artistic creation: in this sense, and although Aristotle's differential rationality is flouted here, we are indeed in the presence of a properly poetic reflection.

Diderot announced, in the last paragraph of the Salon of 1765 we quoted, the traditional parts of an academic treatise on painting: "of drawing, color, manner, chiaroscuro, expression and composition"5. The starting point is drawing, which, in the tradition bequeathed by Poussin and Le Brun, constitutes the noble part of painting, through which it is equivalent to poetry, since drawing produces and arranges figures on a stage in the same way as the dramatic poem. Color only comes later, because, absent from poetry, it constitutes a means of its own, singular, inexpressible and, by extension, disquieting. The manner is even more worrying than painting: characterizing the style of the work produced, it refers to pictorial matter itself, and abolishes the transparency of representation to its object. Things get worse when we come to chiaroscuro, which makes figures disappear into the shadows, dissolving them in the interplay of colored matter. Then painting can reorganize itself afresh: it is no longer drawing and figures, but expression that becomes the principle of representation, while the fixed, as it were geometric, order of the Poussinian scene is replaced by a new type of composition, known as "expressive composition" (p. 501/61), based on movement and, in this movement, as we shall see, on reversal.

Diderot will follow the announced plan, which radically deconstructs the academic poetics of painting. Indeed, he intends to make this deconstruction felt in the very wording he ultimately gives his chapter titles, with a parodic casualness worthy of Fielding or Sterne novels: "Mes pensées bizarres sur le dessin" (p. 467/11) herald a conception that has little in common with academic teaching and its Cartesian model adapted by Le Brun to painting, of a drawing that characterizes the passions of the soul by means of differential strokes permitting all the expressive oppositions, and hence all the polarities likely to structure the scenic space. "Mes petites idées sur la couleur" (p. 472/18) doesn't sound very serious either: is this the way to pledge confidence to harshly judged artists and readers likely to spend a fortune buying paintings they haven't seen, on the sole faith of what the Correspondance littéraire will have said about them? "Everything I understood about chiaroscuro in my life" (p. 477/26) ironically returns to the chiaroscuro of the notion, and hardly indicates that one should emerge enlightened. "What everyone knows about expression, and something everyone doesn't know" (p. 486/39) announces the paradoxical reversal from a notion that formed the backbone of Le Brun's famous lecture on "l'expression des passions6". Finally, "Paragraphe sur la composition où j'espère que j'en parlerai" (p. 496/53) underscores the digressive nature of a text that refuses to assume its role as a treatise.

The figure, a central but disappointing notion

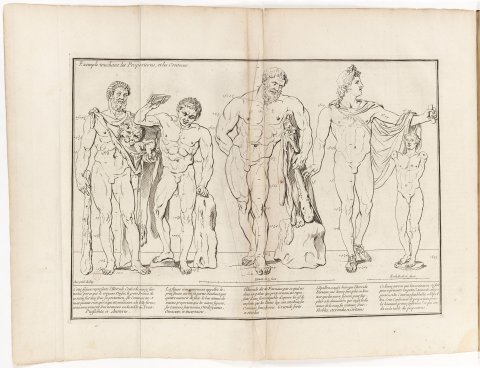

Just as the outline of the Traité apparently unfolds the parts of an academic course on painting, but doubly deconstructs its substance, through the order of the unfolding and the parodic formulation of the chapter titles, so the vocabulary of the Essais sur la peinture seems at first to correspond to academic vocabulary, since the central notion, which recurs on every page from start to finish of the Essais is the notion of figure. The figure is the basic mechanic of the poetics of the painting7: the expression of passions, which constitutes the stakes of classical pictorial representation, is achieved through figures and their arrangement. According to Le Brun, expression "must enter into the representation of landscapes, and into the assembly of figures8".

Thus, when it comes to contours, "Raphael, was careful to make them precise and correct in his works following the example of the excellent painters of antiquity, who were so exact in profiling even the smallest limbs of bodies, so that we might better see the figure, being certain that it is the circumscription of the lines (I must use this word) that gives knowledge of the true shape of the body9 ". As for Poussin's La Manne, its success lies in "this judicious contrast which serves to give movement, and which comes from the different dispositions of the figures whose situation, aspect and movements being in conformity with the story engender this unity of action and this beautiful harmony which we see in this painting10".

The figure is the instrument by which the system of differences constitutive of the poetics of the classical painting is established: the figure is first circumscribed by lines, i.e. it shares an interior and an exterior, signifies the body through this sharing. The figures are then arranged to form masses and groups: these arrangements of figures constitute the unity of action according to the principle of a "judicious contrast", i.e. once again a difference, a polarity. Finally, "figure assembly" is differentiated from "landscape representation" by opposing two spaces in the painting, the stage and the background scenery, i.e., on the one hand the restricted space where the figures play out the action and the vague space that serves as their backdrop.

It should come as no surprise, then, that the term figure obsessively recurs in the Essais sur la peinture. But the formulas with which the figure is associated are almost systematically disappointing, or negative: "Cover this figure, show only the feet" (p. 467/11); "A human figure is too composed a system..."; "to accuse a figure of being badly drawn"; "a figure difficult to find" (p. 468/13); "of false, primed, ridiculous and cold figures" (p. 470/15); "try, my friends, to suppose the whole figure transparent and to place your eye in the center" (p. 471/17); "si une figure est dans l'ombre" (p. 482/33); "plus la figure aurait la figure d'un homme de bois" (p. 485/37); "je laisse là le reste de la figure" (the figure of Antinous to be disfigured, p. 486/39); "when the poet says, vera incessu patuit dea, you have to look within yourself for that figure (which does not exist, therefore, p. 489/43); "When you consider certain figures, certain head characters by Raphael, the Carraches and others, you wonder where they got them from" (p. 490/45); it is ridiculous "to compare any common figure with the Venus of Gnide or Paphos" (p. 493/49); "no idle figure, no superfluous accessory" (p. 496/54); "Take away from Watteau his sites, his color, the grace of his figures" (p. 498/56); "ces figures partagées, ces personnages indécis" (p. 499/57); "il s'agit vraiment bien de meubler sa toile de figures!" (p. 500/59); "Figure, que me veux-tu?" (ibid., paraphrasing Fontenelle); "Je me soucie bien que l'artiste ait disposé ses figures" (p. 501/61); "From six to five figures, scarcely two or three would remain on which the brush would not have to be passed" (p. 502/62); "half-naked figures in a composition, are like forests and countryside transposed around our houses" (p. 504/64); "the actions and movements of the figures, so far removed from real actions and movements" (p. 506/66); "let me be shown over the whole surface of the earth, I do not say a single whole figure, but the smallest part of a figure, a fingernail, that the artist can rigorously imitate" (p. 512/74).

In this virtually exhaustive survey of the word's occurrences, we have not for the moment focused on the logic of the demonstration, but on the context, the situation in which the figure appears: it's always a question of denouncing a representational artifice, distancing oneself from an outdated conception of history painting, ridiculing a distortion, or then outright attacking the figure, disfiguring it, making it transparent or, on the contrary, plunging it into shadow, i.e. fundamentally stripping it of its differential function both internal (as the circumscription of a body) and external (as constitutive of a mass or group).

Representation as alteration

"My weird thoughts on drawing

. Nature does nothing incorrectly. Every beautiful or ugly form has its cause, and of all the beings that exist, there is not one that is not as it should be.

Look at this woman who lost her eyes in her youth. The successive growth of the orb has no longer distended her eyelids. [...] The alteration has affected every part of the face." (P. 467/11.)

The starting point of Essais sur la peinture is certainly drawing, i.e. the academic basis of pictorial representation. But drawing, instead of circumscribing figures, produces alterations11. Worse: it's not the painter who alters the figures; it's nature itself. Diderot thus telescopes three levels of poetic activity, the productions of nature, their representation on the painter's canvas and the poet's descriptions of them (Diderot never defines himself as a critic).

Alteration deconstructs the figure as a principle of differential structuring of the painting, and the entire first part of the Essais accomplishes this deconstruction: the work of negativity is spectacular at the opening of the first chapter of the Essais, where Diderot camps, in place of the traditional models given to admire (the Medici Venus, the Belvedere Apollo, Ganymede and Antinous), a blind woman and a hunchback. In Chapter IV on expression, however, the Essais effect a reversal, at the end of which alteration is to become the new organizing principle of representation. In Chapter VI on architecture, the term reappears, immediately associated with the hunchback of Chapter I:

"In the lower orders [of society] we must choose the rarest individual, or the one who best represents his state, and then submit to all the alterations that characterize him. The figure will be sublime, not when I notice in it the exactitude of proportions, but when I see in it, on the contrary, a system of well-connected and necessary deformities.

Indeed, if we knew how everything fits together in nature, what would become of all the symmetrical conventions? A hunchback is hunchbacked from head to toe. The smallest particular defect has its general influence on the whole mass." (Essais, chap. VI, p. 512/75.)

From the arrangement of figures, we have moved on to "a system of well-bound and well-necessary deformities", i.e. not only from the figure to disfiguration, but from the differential play of classical composition to a production of meaning that passes through binding, dynamic alteration, movement. The figure is conceived first and foremost as a displacement of a line: "A line displaced by the thickness of a hair, embellishes or disfigures" (p. 490/44).

The anamorphoses of figures that Diderot indulges in in the Essais sur la peinture ("Keep all the features of this beautiful face as they are, raise only one of the corners of the mouth", p. 487/40; "does it occur to you to transform your linen maid into Hebe?", p. 513/76) follow that of Giambologna's massive Hercules Farnese as a frail Mercury, then vice versa of Mercury as the Hercules imagined in the Salon of 1765, the two figures coming together in Antinous, an ideal and therefore null, unreal figure, "a man of no state", "an idler who has never done anything, and whose proportions have not been altered by any of life's functions"12. The figurative line moves imaginatively, becoming a principle of alteration rather than circumscription, snaking not to dispose, but to animate space, populating it with ghosts. Incantorily summoned as "true ideal model of beauty, true line" in the preamble to the Salon de 1767 (p. 525), it becomes the screen that stands "between truth and its image":

"Don't you agree that every being, especially animate, has its functions, its passions determined in life; and that with exercise and time, these functions must have spread over its whole organization an alteration so marked sometimes, that it would make one guess at the function? Wouldn't you agree that this alteration not only affects the general mass, but that it's impossible for it to affect the general mass without affecting each individual part? Do you not agree that when you have faithfully rendered both the alteration proper to the mass, and the consequent alteration of each of its parts, you have made the portrait? So there is a thing that is not the thing you painted, and a thing you painted that is between the original model and your copy." (P. 523.)

This thing from which painting produces its alteration is the "subsistent phantom that serves as your model", "this ill-finished shadow", "this phantom" (p. 522). The theoretical model invoked here is explicitly Platonic, against Aristotelian poetics, but Diderot gives it a new functionality: the figurative line stands between the reality that painting shows and the invisible phantom it feeds on and gives us to imagine; between the primary model, this ideal model of Platonic beauty, and the painting we have materially before our eyes, a ghostly thing stands in between. Painting becomes "the art of arousing ghosts, of animating them" (Essais, chap. V, p. 502/62); without it, "no ghost that obsesses you and follows you" (ibid.).

The poetics of the painting finds its limit here: painting is not just about arranging, or even altering visible forms. To paint is to deal with ghosts, Diderot playing to the full the classic ambiguity of the word, which already means the ghosts of cemeteries, but still retains the Greek meaning of φαντάσμα, of representation, at the interface therefore of the visible and the invisible.

II. Stage device

With nature, the painter and the poet thus fused into a single gaze that both attends as spectator and creates the spectacle it witnesses, it is no longer a painting, it is a scene that unfolds before us, without the technical framework of a border, without the immediate boundary from the real world to the pictorial matter of representation.

Voiling the hunchback: the matrix scene of the Essays

The scene that emerges before us is neither real nor artificial; it is, in the real, composed, arranged. It constitutes a device. Let's take up the beginning of the Essais sur la peinture :

"Turn your gaze on this man whose back and chest have taken on a convex shape. While the anterior cartilages of the neck lengthened, the posterior vertebrae collapsed. The head turned upside down; the hands straightened at the wrist joints; the elbows swept back; all the limbs sought the common center of gravity best suited to this motley system. The face took on an air of constraint and pain. Cover up this figure, show nature only the feet; and nature will say, without hesitation, These feet are those of a hunchback." (P. 467/11.)

The establishment of a "heteroclite system" of alterations to the figure13, of a universal principle of disfigurement is in fact only the prerequisite of the performance, the preparation for the real spectacle that follows, and presents itself as a dialogue of painter-poet and nature. Before the disfigured figure of the hunchback, the artist interposes a veil: covering the figure, he delimits a stage; lowering, then raising the curtain of representation, he initiates the essential theatrical game, that classic game where the real is always sent backstage, into the wings of impropriety. Nature's word, "These feet are those of a hunchback" accomplishes the performance of representation, which is thus defined both as discourse, as the articulation of a visibility to an invisibility, as the displacement of what is shown towards what is hidden and understood only by breaking in14.

The interposition of the veil, the interception of the gaze are the watchwords of the scenic device, and return obsessively in the Essais.

"Let me carry the veil of my hunchback over the Venus de Medici, and let only the tip of her foot be seen. If, on the end of this foot, nature, evoked again, were to complete the figure, you would perhaps be surprised to see only some hideous, counterfeit monster born under her pencils." (P. 468/12.)

The artist merely transports the veil; it is nature that completes the figure: the scenic device dethrones the sovereign gesture of the drawing hand; it displaces creation from mimesis proper to the circumscription, installation, interposition constitutive of the scenic space. Already, the model of artistic production is photographic.

The veil thus has not essentially, in this new model of understanding representation, a function of delimitation, of division, but of superimposition: the Medici Venus, ideal model of ancient beauty, once veiled, comes to be imaginatively superimposed on the inaugural veiled hunchback of the Essais. However admirable, this handcrafted Venus cannot technically realize the virtual figure of a perfect body: to produce the figure is already to alter it. The imperceptible alteration of the Venus' foot, if nature were called upon to deduce the corresponding natural body, would run the risk of accentuating itself and producing a monster - in other words, the very hunchback from whom the device of the veil was borrowed. What the veil fundamentally implements, then, is the superimposition of the Venus and the hunchback. The unveiling of the body of which only the beautiful foot could be seen, revealing a hideous, counterfeit hunchback instead of the expected Venus, is the repeated scenario of the device: it manifests the play of the scopic impulse, which ensnares the eye with the lure of the beautiful foot, fascinates it by means of this lure, this fetish, then, brutally, abolishing the distance from the painted object, erasing the boundary between the real and the represented, precipitates it into horror and abjection, makes it see what it had wanted to avoid, precipitates it, plunges it, envelops it in an absolutely new dimension of representation, the revolting dimension of the real. The eye is thus brought out of its hinges by the play of the device, literally exorbitant: at the beginning of the Essais, the portrait of the old blind woman with empty orbits, whose eyelids "have reentered the cavity that the absence of the organ has hollowed out" (p. 467/11), preceded the evocation of the hunchback.

The principle of superposition

The rest of the Essais unfolds as an attenuated repetition of this gesture, or inaugural trap. The artist's eye is distorted by his temperament:

"If he is icteric and sees everything yellow, how will he prevent himself from casting over his composition the same yellow veil that his vitiated organ casts over the objects of nature, and which grieves him, when he comes to compare the green tree he has in his imagination, with the yellow tree he has before his eyes?"(Chap. II, p. 473/20.)

Not only does the veil of temperament, interposed between eye and object, reverse the warm colors of pictorial matter into bilious overproduction, abject organic excretion, but the veil triggers superposition, inviting comparison between the real, but absent, invisible green tree and the yellow tree produced by the paint. Two images are thus conjoined by the device, the scene constituted by the journey from one to the other, by the disfiguration of the ideal into the material, of the real into the painted.

This superposition does not constitute a stable structure: the device is an adaptation, a movement from the figure to its disfiguration, from disfiguration to the restitution of a figure:

"Here on a canvas is a woman dressed in white satin. Cover the rest of the painting, and look only at the garment; perhaps this satin will seem dirty, dull, untrue. But restore this woman in the midst of the objects with which she is surrounded, and at the same time the satin and its color will resume their effect." (Ibid., p. 475/22.)

Maybe Diderot is recalling here Roslin's portrait of the Countess d'Egmont Pignatelli, about whom he wrote, in the Salon de 1763 : "the dress doesn't do satin too badly. The flesh is a little white. [...] In general the whole looks white; that's because we aimed for brilliance and effect." (P. 273/231.)

Here, the interposition of the veil doesn't obscure the figure, but precisely, on the contrary, what surrounds it, the "objects with which it is surrounded". But it's the same interplay of concealment and revelation that turns "dirty, dull, untrue" satin into brilliant satin, "satin and color regaining their effect": the satin sheen of white fascinates the eye, but after having revolted it from its dirtiness; the fascination is born of a reversal of abjection, the eye "revolts" in a way the dirtiness by bursting forth, the ignoble extinction of the dirty garment in theatrical, luminous appearance, on the primed stage of the apartment where the marquise makes her entrance and strikes a pose.

For the veil is a theatrical curtain: it not only diminishes the lures of a figure made a ghost or turning into a monster; tearing, opening, it triggers the coup de théâtre of an apparition:

"Perhaps it would belong to only one master to tear away the cloud that enveloped Aeneas, and show him to me as he appeared to the credulous and facile queen of Carthage:

Circumfusa repente

Scindit se nubes, et in æthera purgat apertum15." (Chap. III, p. 480/29.)

The figure of Aeneas is accessed through the cloud that enveloped him, circumfusa nubes, and which the eye tears apart: the painter's creative act is identified with the action of the viewer's eye, which splits, scindit, and discriminates. To this example, which Diderot borrows from Webb16, he prefers that of Venus appearing to Aeneas in the forest of Carthage:

"When the poet says, vera incessu patuit dea, you have to look within yourself for that figure. When he says, summa placidum caput extulit unda, one must model that head there." (P. 489/43.)

Vera incessu patuit dea, it's in her gait that the true goddess betrays her divine nature: the foot once again manifests the figure in this movement of the gaze which rises from the bottom of the dress, and which Freud identifies with the fetishist gaze, stopped by this limit, refusing to confront the archaic horror of the veiled sex17. The scenic device signifies the fetishist stop and at the same time transgresses it; it says how inaccessible the object of the gaze is, and yet, by breaking in, by surprise, it makes it seen anyway.

To the example of Venus revealing herself to her son, Diderot joins that of Neptune taking his head out of the waves, at the end of the storm that opens the Eneid : Neptune projects his calmed head, placidum caput extulit, from the depths of the wave, summa unda. Only the head is shown, leaving us to imagine the god's gigantic yet invisible body. Diderot had already used this example in the Lettre sur les sourds. For him then, despite Rubens' example18, such a painting was impossible, or at least a challenge:

"why should the god then appear as nothing more than an unstuck man, and his head, so majestic in the poem, look bad on the airwaves? How does it happen that what delights our imagination displeases our eyes? (Lettre sur les sourds, p. 44.)

The Diderotian device consists once again in superimposing two images, the Virgilian image of imagination and the material image of the painter. The sublime Virgilian colossus then turns into the abjection of "an unstuck man", who doubly topples the father figure, Neptune first, Virgil second.

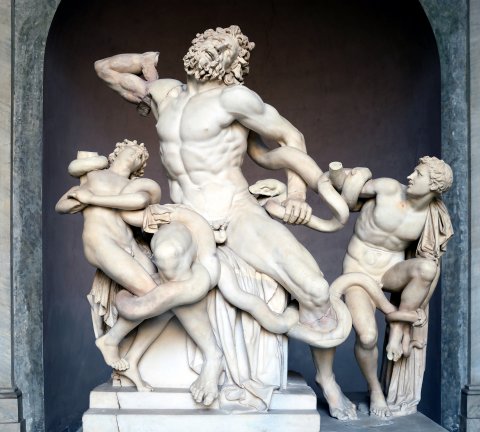

The deconstruction of the figure is then embodied in the relationship of the eye to the stage, as symbolic castration, where the father's face is reached and crossed out. If Neptune's head emerging from the pacified ocean becomes a severed head floating on the sea, the Laocoon, another oh-so-emblematic figure, doesn't meet a more enviable fate:

The deconstruction of the figure is embodied in the relationship between the eye and the stage, as a symbolic castration, where the father's face is hit and crossed out.

"Every scene has an aspect, a point of view more interesting than any other; that's the way to see it. Sacrifice to that aspect, to that point of view, all subordinate aspects or points of view; that's the best. What simpler, more beautiful group than that of Laocoon and his children? What group could be more sullen, if viewed from the left, where the father's head is barely visible, and one of the children is projected onto the other? However, the Laocoon is still the most beautiful piece of sculpture known." (End of chap. V, pp. 507-508/68-69.)

The point of view from which the scene19 is to be ideally viewed is posed only as a prerequisite destined to be transgressed by strolling around the statue. The point of view is part of the a priori figural representation, which the implementation of the device must blur and then restore, disfigure and then reconfigure. The beauty of the Laocoon is undone when the statue is circumvented laterally, in a way that deliberately veils the father's face ("the father's head can barely be seen") and crushes his children on top of each other ("one of the children is thrown on top of the other").

.Once again, the creative gesture does not consist in sculpting the Laocoon, which is given as an a priori figure of representation, but in organizing its disappearance in order, subsequently, to ideally restore its visibility: "However, the Laocoon is so far the most beautiful piece of sculpture known." Symbolic castration (defection of the father, crushing of the children) bars the figure, but at the same time organizes the path of the gaze, through the pulsation of which the object can, nonetheless, be reached and mastered.

III. Towards a poetics of connections

The line

This pulsation, which gives rhythm to the alteration of figures and implements the scenic device, is thematized by the snake:

"The Laocoon suffers, he does not grimace. Yet the cruel pain snakes from the tip of his toe to the top of his head. It affects deeply without inspiring horror. Please let me neither stop my eyes, nor tear them from your canvas." (Chap. IV, p. 489/43.)

Diderot would return, in the Paradoxe sur le comédien, to the need to compose theatrical pain, not to exhibit its grimacing reality, but to produce its most aestheticized artifact20, which clearly shows that, even when deconstructed, the figure, with all its stylization and "academic" postures, remains for him the fundamental instrument of representation.

But the expression of passions no longer takes the form of a fixed line: it "snakes", i.e. it constitutes itself both as line and undulation. We find here the terms by which Hogarth sought to rethink the composition of forms, both in painting and sculpture: "undulating line" runs through and unifies the furnishings of houses, or follows the whalebone of corsets (waving-line, chap. IX); the "serpentine line" wraps around the horns of plenty and bones of the human skeleton, which it envelops in muscle, flesh and drapery (serpentine-line, chap. X). Undulating and serpentine, they constitute respectively the "line of beauty" (line de beauté) and the "line of grace" (line de grace), echoed in the apostrophe to the painter that opens the Salon de 1767:

"Your line would not have been the true line, the line of beauty, the ideal line, but any line altered, distorted, portraitique, individual" (p. 522).

Under the influence of Hogarth, then, Diderot thinks of composition as a single line, no longer as a system of strokes that delineate and contrast figures. The differential game is replaced by a system of links.

Notes

G. Genette, H. R. Jauss, J.-M. Schaeffer et alii, Théorie des genres, Seuil, 1986.

G. Genette, Figures II, Seuil, 1969, "Frontières du récit".

References are given in Laurent Versini's edition, Volume IV of Diderot's Œuvres, Laffont, Bouquins, 1996. For the Essais sur la peinture and the early Salons references have been added to the edition by Gita May and J. Chouillet, Hermann, 1984, 2007.

"If all one needed to be an artist was to feel keenly the beauties of nature and art, to carry in one's bosom a tender heart, to have received a mobile soul with the lightest breath, to have been born one whom the sight or reading of a beautiful thing intoxicates, transports, makes sovereignly happy, I would exclaim as I embraced you, throwing my arms around the neck of Loutherbourg or Greuze: "Mes amis, son pittor anch'io." " (Salon de 1763, p. 268/225.) " Happy is he who, going through the lives of great men, approves of them and does not admire them, and says: son pittore anch'io!" (Pensées détachées sur la peinture, p. 1021.)

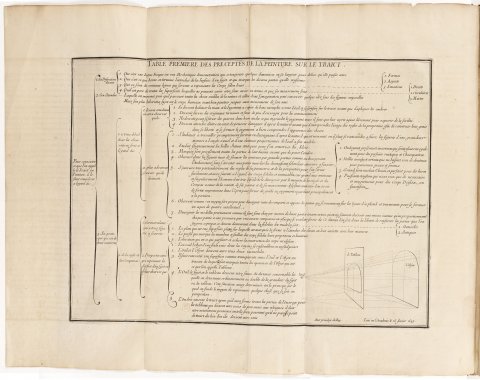

On January 25, 1670, Le Brun had commissioned Henri Testelin to prepare a pedagogical synthesis of the Academy's lectures, and thus put down in writing what would constitute the orthodoxy of academic teaching. Testelin drew up six "tables of precepts", which he published in 1680 (Sentiments des plus habiles peintres du temps, sur la pratique de la peinture, recueillis et mis en tables de préceptes par H. Testelin), and dedicated to Le Brun. Subsequent editions were published in The Hague, as Testelin, a Protestant, had been expelled from the Académie in 1681. The titles of the tables of precepts directly inspired those of Diderot's Essais sur la peinture: "Sur l'usage du trait et du dessin", "Sur l'expression générale et particulière", "Sur les proportions", "Sur l'ordonnance", "Sur le clair et l'obscur", "Sur la couleur". See Les Conférences de l'Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, ed. A. Mérot, ensb-a, 1996, pp. 297sq. But Diderot modifies the hierarchical order followed by Testelin.

Delivered at the sessions of April 7 and May 5, 1668. See Conférences, op. cit., pp. 145sq.

On the figure in Le Brun, and its deconstruction by Diderot, see S. Lojkine, L'Œil révolté, J. Chambon, 2007, chap. 2, "La figure et le moment".

"L'expression des passions", Conférences, op. cit., p. 148.

"Sur le Saint Michel terrassant le démon de Raphaël", ibid., p. 62.

"On The Israelites gathering manna in the desert by Poussin", ibid., p. 103.

Testelin begins by distinguishing two schools of drawing, that "imitating the natural in the simplicity of its form" and that "affecting embellishment" to conform to "the beauty of antique figures". He sided with rigorous imitation of nature, but made sure that this imitation, always presented as a stripping away of forms, a simplification of lines, coincided with the ancient ideal, the study of which he advocated as a propaedeutic to natural imitation, understood as simple imitation. ("Sur l'usage du trait et du dessin", 1675, Conférences, op. cit., pp. 305-311.) It is this coincidence that the Essais begin by dismantling.

Digression from the Servandoni article, p. 351, itself inspired by Chapter I of Hogarth's Analysis of Beauty (1753). But Hogarth speaks of "propriety" (fitness), of adapting body parts to a given purpose or design (to the uses they are designed'd for), the "purposes of speed" (the purposes of speed) for Mercury, the "purposes of the utmost strength" (the purposes of the utmost strength) for Glycon's Hercules. Alteration, disproportion, are therefore no more than "apparent defects" (seeming faults) for those who, unlike the Ancients, have only an inadequate knowledge of anatomy; on the contrary, they reveal "beauty of fitness, or propriety". In Hogarth as in Testelin, true imitation of nature meets the ideal of Greek beauty, and alteration is merely an error of judgment.

Similarly, p. 499/57, "a somewhat composed system of beings".

In a way, this device is already present in Testelin, whose "Table première des préceptes de la peinture, sur le traict", includes a sketch defining, very explicitly, the painting as a screen interposed between the eye and the object. The interposition, like the braces, establishes a division and materializes the scissionist activity of all Aristotelian poetics. But, in Alberti's tradition, this screen is envisaged as a window, giving a mistaken view of the object, without the slightest play or effect of concealment. (See Conferences, op. cit., illustration p. 304.)

"The cloud that surrounded Aeneas opens in two and purifies itself into transparent air." (Virgil, I, 586-7.)

Research into the beauties of painting and the merits of the most famous ancient and modern painters, by Mr. Daniel Webb. Ouvrage traduit de l'anglais par M. B*** [Claude-François Bergier]. Paris, Briasson, 1765.

See Henri Rey-Flaud, How Freud invented fetishism..., Payot, 1994. Henri Rey-Flaud shows that Freud's theory of fetishism evolved from an anal model (the fetish as an idealized substitute for repressed anal pleasure) to a scopic model (the fetish referring to the elusive object of the gaze), which interests us here.

Perhaps Diderot was aware of Rubens' painting of Le Voyage du cardinal infant de Barcelone à Gênes as the face-to-face flotilla of Aeneas and angry Neptune. The painting is now in Dresden, and a sketch is in the Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp. In 1735-1736, Boucher designed the frame of a title page for the allegorical monument engraved in honor of Sir Cloudesley Shovel depicting, on the same model as Rubens, angry Neptune running with his chariot over raging waves (Vienna, Albertina).

No reference to painting in this development on point of view: painting doesn't necessarily have a single point of view for Diderot, who instead enjoys moving towards it, away from it, wandering through it. The single point of view refers to the theatrical stage set-up, within the framework of what E. Hénin calls the ut pictura theatrum: painting, sculpture and theater proceed jointly from the same scenic space. Italian theater is designed for a single, ideal point of view, somewhere in the center of the parterre, it being understood that this point of view... is, so to speak, never that of the spectator in reality! We never see what we should see, and have to mentally recreate.

"An unhappy woman, and truly unhappy, cries and does not touch you; there is worse, it is that a light line that disfigures her makes you laugh ; It's that her habitual movements show you her ignoble and sullen pain; it's that outraged passions are almost all subject to grimaces that the tasteless artist slavishly copies, but that the great artist avoids. We want man to retain his human character, the dignity of his species, at the height of his torments. What is the effect of this heroic effort? To distract from pain and temper it. We want this woman to fall with decency, with softness, and this hero to die like the ancient gladiator, in the middle of the arena, to the applause of the circus, with grace, with nobility, in an elegant and picturesque attitude. Who will fulfill our expectations? Will it be the athlete subjugated by pain and decomposed by sensibility? Or the academic athlete who possesses himself and practices the lessons of gymnastics as he breathes his last? The ancient gladiator, like a great comedian, a great comedian, as well as the ancient gladiator, do not die as one dies on a bed, but are obliged to play us another death to please us, and the delicate spectator would feel that the naked truth, the action stripped of all primp would be petty and contrast with the poetry of the rest." (P. 1387.)

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Les Essais sur la peinture : une poétique de la défiguration », conférence prononcée à l’université catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-neuve, 19 novembre 2007.

Diderot

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Diderot

Les Salons

L'institution des Salons

Peindre la scène : Diderot au Salon (année 2022)

Les Salons de Diderot, de l’ekphrasis au journal

Décrire l’image : Genèse de la critique d’art dans les Salons de Diderot

Le problème de la description dans les Salons de Diderot

La Russie de Leprince vue par Diderot

La jambe d’Hersé

De la figure à l’image

Les Essais sur la peinture

Atteinte et révolte : l'Antre de Platon

Les Salons de Diderot, ou la rhétorique détournée

Le technique contre l’idéal

Le prédicateur et le cadavre

Le commerce de la peinture dans les Salons de Diderot

Le modèle contre l'allégorie

Diderot, le goût de l’art

Peindre en philosophe

« Dans le moment qui précède l'explosion… »

Le goût de Diderot : une expérience du seuil

L'Œil révolté - La relation esthétique

S'agit-il d'une scène ? La Chaste Suzanne de Vanloo

Quand Diderot fait l'histoire d'une scène de genre

Diderot philosophe

Diderot, les premières années

Diderot, une pensée par l’image

Beauté aveugle et monstruosité sensible

La Lettre sur les sourds aux origines de la pensée

L’Encyclopédie, édition et subversion

Le décentrement matérialiste du champ des connaissances dans l’Encyclopédie

Le matérialisme biologique du Rêve de D'Alembert

Matérialisme et modélisation scientifique dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Incompréhensible et brutalité dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Discours du maître, image du bouffon, dispositif du dialogue

Du détachement à la révolte

Imagination chimique et poétique de l’après-texte

« Et l'auteur anonyme n'est pas un lâche… »

Histoire, procédure, vicissitude

Le temps comme refus de la refiguration

Sauver l'événement : Diderot, Ricœur, Derrida

Théâtre, roman, contes

La scène au salon : Le Fils naturel

Dispositif du Paradoxe

Dépréciation de la décoration : De la Poésie dramatique (1758)

Le Fils naturel, de la tragédie de l’inceste à l’imaginaire du continu

Parole, jouissance, révolte

La scène absente

Suzanne refuse de prononcer ses vœux

Gessner avec Diderot : les trois similitudes