In the 1760s, the Salons experience confronted Diderot with what was then called pittoresque allegory, i.e. allegorical paintings. At first glance, he seems to espouse the ideas of Abbé Du Bos, whose criticism of allegory is based on a mistrust of the image's ability to signify, and on the need to subject painting, like theatrical representation, to typologies, standards of propriety and the rhetorical constraints of verisimilitude. But Diderot's critique of allegory, while taking up Du Bos's conclusions, also turns his ideological and semiological assumptions on their head. For Diderot, at the opposite end of the spectrum from the Abbé, allegory is not iconic enough: the idea of the painter, i.e., his thought through images, must be placed at the center of pictorial creation. This is the challenge of the Salon de 1767, which thus breaks with the ut pictura poesis : the scenic device1, where painting and dramatic poetry came to converge and articulate, is now denounced as a rhetorical reduction of thought through image, in the same way as allegory.

I. Du Bos's critique of allegory

Three characteristics of allegory can be identified according to Abbé Du Bos: firstly, allegory functions as an envelopment of meaning; secondly, it is a kind of "mot d'esprit": allegorical invention is a work of the mind, an ingenious spiritual game; finally, allegory is incomprehensible and, for this reason more than any other, it is condemnable.

Allegory as the envelopment of meaning

To decipher allegory is "to seek the meaning of the thoughts of a painter who envelops it always" (p. 692). Our heart, unsusceptible to this game, looks at allegorical characters "as symbols and riddles under which are enveloped precepts of morality and traits of satire that are the province of the mind" (p. 74).

This envelopment of meaning organizes a shift in the text that is of the order of metaphor. Du Bos evokes "the brilliance born of metaphorical action"; the figures of allegory are metaphors and, as such, are displaced from the reality they are intended to represent. But wrapping also ensures a condensation of meaning, and this is the strength of allegory, which wraps a large quantity of meaning under a small number of figures. Du Bos gives the example of Louis XIV's victories in Flanders, painted by Le Brun at Versailles. Painters like Le Brun at Versailles or Rubens in the Marie de Médicis Cycle "show in a single picture events that a historian could only narrate in several pages" (p. 67). In Le Brun's painting, the chariot of Victory, in which the king appears, "overturns in its course the astonished figures of the cities and rivers that formed the Dutch frontier, and each figure is first recognized either by the shield of its arms or by its other attributes" (p. 68). The painting becomes a book, each allegorical figure condensing a page of history, a battle narrative, and coming to articulate itself to the single chariot of victory that envelops the meaning of its glory, shielding by its triumph the tumult, the horror, the detail of the fighting.

Allegorical envelopment is thus both a matter of displacement (of metaphor) and condensation. Du Bos curiously joins the unconscious grammars of Freudian witz3.

Allegory as wit

For him, moreover, allegory has the same subversive function as the witticism. He gives two examples. The heir to the great Condé, having undertaken to have his father's history painted at Chantilly, had to depict the Frondeur's deeds in Flanders at a time when the latter "had found himself linked by interest with the enemies of the State". The allegory here circumvents the political prohibition that should apply to such a representation:

"He therefore had the Muse of history [...] drawn, holding a book on whose spine was written Vie du prince de Condé. This Muse was tearing out leaves from the book, which she threw on the ground, and on these leaves were read Secours de Cambrai, Secours de Valenciennes, Retraite de devant Arras; finally the titles of all the fine deeds of the Prince de Condé during his stay in the Spanish Netherlands, deeds of which everything was praiseworthy, except for the scarf he wore when he did them." (P. 67.)

The seditious man's victories are, through this allegorical subterfuge, both represented and ripped from the book: we see what we shouldn't see, arranged in such a way that we see it with a clear conscience. The allegorical game here intersects with the screen device that structures and models the classical history scene.

The second example is theatrical:

"I'm not unaware that the characters in several of Aristophanes' comedies, those in the Birds and the choruses in the Numbers, for example, are allegorical. But [...] this poet wanted to play in Athens the most considerable men of the Republic [...]. Aristophanes [...] could therefore not mask his characters too much, nor disguise his subjects too much. Thus, allegorical action and characters were more suited to his purpose than ordinary characters and action." (P. 74.)

Aristophanes' laughter thus masks the attack, the political aim, in the very movement of the allegory enveloping the meaning of the play. The allegory proceeds from the stroke, the witty aggression of the witz hitting the nail on the head.

This spirit is suspect, perhaps precisely because it is subversive. Allegory is also unsuitable "in devotional pictures", where it is nevertheless so often practiced:

"Truths we cannot think of without terror and humiliation must not be painted with such wit, nor represented under the emblem of an ingenious allegory invented at pleasure." (P. 70.)

The ingenuity of allegory is a work of pleasure; the work of aesthetic enjoyment is at work here, both for the creator and the spectator. In the theater, for example, "it takes too much wit to always correctly unravel the application we should make of an allegory" (p. 73). The speed of the pas-de-sens4 allegory is that of the witticism. In a word, allegory has "the defect of liking too much to make use of the brilliance of the imagination, which is commonly called wit" (p. 68). It is the preserve of "writers, to whom no one denies wit", and who would have benefited from "being less ingenious and treating a subject historically" (p. 73). It is characterized by "brilliance", "delicate thoughts", "fine turns", "all the graces that a fine mind can draw from a [...] fiction" (ibid.).

This spirit of allegory, against which Du Bos has no words harsh enough, is opposed to propriety and verisimilitude, which allegory contravenes. The most shocking defect of allegory is the defect of propriety, which leads Dubos to condemn "mixed compositions", such as those in Rubens' Cycle de Marie de Médicis, where real characters and allegorical figures are mixed: "allegorical characters employed as actors in a historical composition must alter its verisimilitude" (p. 63). Thus, in Le Débarquement à Marseille, "the nereids and tritons sounding from their conches, which Rubens has placed in the harbor to express the gladness with which this maritime city receives the new queen, do not make a good effect according to my feeling." (P. 64.)

Because it is witty, the allegory is implausible. It combines, through its line, the real and the chimerical or, more precisely, a plausible representation of reality and an ingenious construction of the mind. Allegory exhibits the artifice of representation, plays with it and enjoys it.

The allegorical artifice then tends to become an autonomous construction: the line distends, breaks, the plausible articulation is lost; the allegory becomes incomprehensible5.

The allegory is incomprehensible

Allegorical figures become "hieroglyphic figures" (p. 66). Hieroglyphics, indecipherable before Champollion, are the very model of obscurity; they are incomprehensible signs:

"Painters rarely succeed in purely allegorical compositions, because it is almost impossible that, in compositions of this kind, they can make their subject distinctly known and bring all their ideas within reach of the most intelligent spectators. [...] Purely allegorical composition should therefore only be used in cases of urgent necessity [...]. If it is not easily heard, it is left as a vain galimatias. There are galimatias in painting as well as in poetry" (ibid.).

Allegory presupposes a decoding task for the reader-spectator: it is a screen-image whose unintelligibility must be reduced in order to reach its meaning. Du Bos refuses this deciphering, this imaginative relationship to representation, which is the antithesis of the rhetorical demands of the movere6: representation must "move us" and not "exercise our imagination"; "The paintings must not be enigmas" (p. 68), nor represent "chimeras, whose mysterious allegory is an enigma more obscure than those of the sphinx ever were" (ibid.). We're not here to look for "the net of these numbers" (p. 69), "numbers to which no one has the key" (p. 63).

Du Bos thus clearly contrasts, in these two sections, two irreconcilable semiological functionings of representation: allegory is based on the envelopment of meaning, on the witticism that covers, then discovers, after deciphering, the intellectual truth of the subject. Allegory thus brazenly exhibits the mechanics it employs. In contrast, verisimilitude proposes a transparent representation of the subject: it relies on the expression of passions7, a stable, known typological structure endowed with a syntax that allows its elements to be combined ad infinitum. Verisimilitude doesn't build a new code every time; its apparent permanence gives the illusion of its transparency, the illusion that there is no code, no enigma, no cipher. This transparency of verisimilitude is the necessary condition for illusion, that is, for the abolition of the support of representation for the spectator: in front of him, there is no poetry, no painting, no stage trestles, no canvas, but representation, a subject, a story into which he enters directly. Verisimilitude ensures the functioning of the ut pictura posesis, that is, the circulation from text to image, from image to text.

On the contrary, allegory underlines the artifice of its construction: giving itself to interpretation, it designates itself as an envelope, i.e. a support. But interpretation is the antithesis of illusion: suddenly, the fact that it's painting or poetry becomes essential. This is the sign that the ut pictura poesis has ceased to be operative.

II. Cold symbols and passing shadows: the recovery of allegory in Diderot's Salons

Diderot apparently takes up the essentials of Du Bos's attacks on allegory: but a close comparison of the abbé's and the philosopher's motivations in fact reveals a head-on opposition. Diderot was going to use the discredit to which allegory had fallen in the eighteenth century, not to save the ut pictura poesis and the semiology of verisimilitude attached to it, but to break definitively with it, recovering the allegorical image, hijacking it to put it at the service of a generalized practice of thinking through images. Thought through images proceeds at the antipodes of verisimilitude: it distorts the models provided by culture, it combines the noble figures of tradition with the trivial realities of contemporary life, it proceeds by leaps and incongruities.

Half plausible, half allegorical: mixed compositions

As early as the Salon de 1761, commenting on La Publication de la paix en 1749 by Dumont le Romain, Diderot takes up Du Bos's criticism of mixed compositions: "Real beings lose their truth next to allegorical ones" (DPV XIII 216; Laffont 2028). Rubens' Marseilles tritons come to mind: In this case, Du Bos recommends eliminating allegorical figures, out of place in a modern history painting. Modern history is part of a culture where mythology and allegory are no longer objects of belief: none of us today believes in the reality of these figures, whereas the characters in an ancient scene are supposed to believe in the reality of the allegorical figures around them, and their religion and culture accepted these figures as plausible. The rejection of allegory is a question of propriety, i.e. of uniformity in the code of representation.

Diderot does indeed start from this question of propriety, but he turns it on its head:

"The contrast of these ancient and modern figures would lead one to believe that the painting is a composite of two patches, one of today and the other that was painted some thousand years ago ; and Abbé Galliani would separate it for you with scissors, leaving9 on one side all the flat and ridiculous, and on the other all the antique that would be bearable and that everyone would interpret as they pleased. One would find a hundred features of Greek or Roman history to which it would return." (DPV XIII 216; Laffont 202.)

If something is to be retained from Dumont le Romain's painting, then it is not the subject of recent history, which is flat and ridiculous, but the allegorical figures, because they contain something of ancient grandeur. Nor is it a question of reintegrating these figures into a picture of ancient history, where they would respect the necessary propriety, but of being able, at will and by imagination, to relate them to "a hundred features of Greek or Roman history". Once cut out, the figures become virtual images, left to Diderot's creative reverie. The allegorical image becomes an "idea", that is, a support for thought through images, the support of all representation.

Diderot takes up the criticism of mixed compositions in connection with Rubens' La Naissance de Louis XIII, a painting that Du Bos himself had commented on in section 24. In the Essais sur la peinture, he writes:

"I cannot suffer, unless it be in an apotheosis or some other subject of pure verve, the mixture of allegorical and real beings. [...] The mixing of allegorical and real beings gives the story the air of a tale, and to cut a long story short, this defect disfigures most of Rubens' compositions for me. I can't hear them. What is this figure holding a birds' nest10, a Mercury11, the rainbow, the Zodiac, Sagittarius12, in the bedroom and around the bed of a woman in labor? You'd have to get a legend out of each of these characters' mouths, as we see on our old castle tapestries, to say what they want." (DPV XIV 390; Laffont 499.)

The figures evoked by Diderot are those from La Naissance de Louis XIII, a painting he has just praised and to which he returns repeatedly with praise in the Salons. Certainly, like Du Bos, it is the expression on Marie de Médicis's face, where the past pain of childbirth and the nascent joy in the face of the child mingle, that holds his admiration13.

Allegorical figures fail to produce their effect because of a lack of appropriateness, because there's a mismatch between the heroic, glorifying world of allegories and the intimate, familial space constituted by the "bed of a woman in childbirth". Diderot would later recall Horace's precept: painting and poetry "must be bene moratæ; they must have morals" (DPV XIV 391; Laffont 500), i.e. they must contribute to a strong moral idea14.

This requirement of propriety apparently reproduces Du Bos's discourse and seems to reaffirm the classic principle of representational propriety. And yet, on closer inspection, everything about the image Diderot conjures up is distorted: the heap produced by the enumeration of allegories, the casual expression that designates the figure of abundance, "this figure holding a bird's nest", tip the heroic universe of Rubenian allegory into the naive familiarity of "our old castle tapestries". Conversely, what is this "bed of a woman in childbirth" evoked by Diderot, when the queen gives birth, in Rubens, seated on her throne!

The opposition, the contradiction of morals that Diderot notes in compositions mixing allegorical and real beings, is therefore not the contradiction of the morals of reality and the morals of allegory, but that of the tapestry of the medieval castle and the painting of Greuze's bedroom, a contradiction not generic, but semiological, between two kinds of allegory: enigmatic allegory of the ancient ages, with its phylacteries and mottoes; familiar, bourgeois allegory of the Enlightenment, where the word is no longer in a book, but in the mouth of children, or in the falsely naive questioning of the philosopher. Witness the two examples Diderot cites after Rubens's.

First is the monument erected by Pigalle in Reims in honor of Louis XV, monument that Diderot had already scorned in an article in the Correspondance littéraire in July 176015 and whose construction had just been completed in 1765, at the time he was writing the Essais sur la peinture :

"I've already told you my opinion of the Rheims monument executed by Pigalle, and my subject brings me back to it. What's the significance of this woman leading a lion by the mane, next to this porter lying on bales? The woman and the animal are going to the side of the sleeping porter, and I'm sure a child would exclaim: Mommy, that woman is going to make that poor sleeping man eat her beast." (DPV XIV 390; Laffont 499.)

The woman driving the lion is an allegory of good government, the flourishing city being traditionally represented, since Imperial Roman times, by a Cybele crowned with towers and driving a chariot drawn by lions16. As for the "portefaix", which is a self-portrait of the sculptor, it actually symbolizes the citizen enjoying the benefits of public bliss. However, the Reims monument does not blatantly mix allegory and reality, with the only real character, Louis XV, appearing above, off-stage. What is shocking, heteroclite, is the juxtaposition of the outdated codes of the medieval allegory of good government and that good peasant woman leading her beast, of the ideal citizen and the trivial portefaix.

Allegory, if it doesn't manipulate the very images of reality, turns into a contradiction in terms. It becomes a collection of figures:

"It's really all about furnishing your canvas with figures! These figures must place themselves there, as in nature. They must all contribute to a common effect, in a strong, simple and clear manner; otherwise I'll say like Fontenelle to the Sonata: figure, what do you want from me17?" (DPV XIV 391; Laffont 500.)

The classical conception of allegory as a taxonomy of figures, as a language-like syntax of coded images, could not be more radically condemned. But what is condemned here is not allegory as a genre and as a means of expression, it is a certain semiological functioning of representation reducing the image to a rhetorical allegory, to a succession of signs.

Diderot, on the contrary, assumes the floating, polysemous character of the allegorical image, based not on an articulation, but on a concentration of meaning: the "common effect", the "strong, simple and clear manner" place in the foreground the immediate, non-verbal impact of the image, the iconic power of an overall effect that will not break down into figures. This semiological transformation of allegory, which now involves the imagination and even knowingly plays on the popular springs of the image, is inseparable from the ideological transformation that is taking place: Pigalle had already renounced the traditional slaves accompanying the King's Triumph for his monument in Reims, substituting them with this Citoyen satisfied with the gentleness of a government that was renouncing absolutism of its own accord18. Diderot goes further:

"Pigalle, my friend, take your hammer, break me this association of bizarre beings. You want to make a king protector; let him be so of agriculture, commerce and the population. Your porter sleeping on his bales, that's Commerce. Slaughter a bull on the other side of your pedestal; let a vigorous inhabitant of the fields rest between the animal's horns, and you'll have Agriculture. Place a fat peasant woman suckling a child between the two, and I'll recognize Population." (DPV XIV 390-391; Laffont 499-500.)

The imaginary gesture of breaking the statue, which will be found at the beginning of D'Alembert's Dream19, Diderot breaking Falconet's Pygmalion to, on its crumbs, lay the foundations of a biological materialism, changes the status of the image that occupies the text, but does not destroy this image: from the statue (imago, image), we move on to the idea, the model, the Platonic phantasma that Diderot will summon in the preamble to the Salon de 176720.

In fact, the virtual monument that Diderot proposes to Pigalle as a replacement for his own is not an absolutely different monument. It is indeed conceived from the real, failed monument, as an anamorphosis of it: the three characters - the woman, the lion and the portfaix - are not removed but transformed. The portmanteau is no longer the symbol of the satisfied citizen, but of Commerce; the lion becomes a bull, symbol of Agriculture; the woman, to whom the child spectator and critic summoned a few lines earlier is added, integrated into the representation, will henceforth represent the Population.

The essential function of this anamorphosis is to transform the relationships between the various elements of the allegory. In the old system, the figures were arranged in a syntax that is no longer understood: the woman led her lion for the greater good of the citizen; in other words, France (figure 1, the woman) softened her government (figure 2, the lion) for the happiness of the French (figure 3, the seated man).

France (figure 1, the woman) softened her government (figure 2, the lion) for the happiness of the French (figure 3, the seated man).

In the allegory Diderot reconstructs, Commerce, Agriculture and Population have no syntactic relationship with each other. Placed equally on the same plane, they all contribute in the same way to the same effect, superimposing, or concentrating three competing images of the same public felicity. The allegorical image has not only become virtual; it claims, outside language, its semiological specificity: it is image and not figure and, as such, cannot be reduced to a linguistic sign; it is juxtaposed and not concatenated; it contributes to a common effect and cannot, for this reason, be subordinated.

The image here is henceforth idea, model, and not imago; it is no longer a question of support; it circulates from poetry to painting, from painting to opera, from opera to the mere flow of the imagination. In order not to reduce the image to a sign, it is sometimes better not to represent it at all. In the case of the Pigalle monument, the strength of the reconstructed allegory lies perhaps in its immateriality.

Similarly, in the Pensées détachées, Diderot prefers not to see any illustration of Ariosto's text, so that the images the poet summons are not fixed, i.e. do not become figures, mere conventional signs:

"Why should the hippogriff, which pleases me so much in the poem, displease me on canvas? I'll say a good or bad reason. The image, in my imagination, is only a passing shadow. The canvas fixes the object before my eyes and instills in me its deformity. There is, between these two imitations, the difference from it can be to it is." (Laffont 101821.)

Du Bos had explicitly disapproved of the "Ariostan visions" for which Diderot begins by confessing his pleasure: how could Roger's ridden hippogriff displease him, the man who complacently parodied it in "Mangogul's Dream" in chapter 32 of Bijoux indiscrets22? Here, Diderot identifies "the hippogriff [...] in the poem" with "the image, in his imagination", while the hippogriff on the canvas is an object external to the viewer, an object that "the canvas fixes [...] before my eyes". Curiously, for Diderot, there is a kind of transparency in the support-text, and an opacity in the support-painting. The textual hippogriff once again pleases as a virtual image, offered fleetingly to the wanderings of thought. It is "a passing shadow": in motion, slipping into the flow of the spectator-reader's poetic reverie, the virtual image escapes the scenic device where, in painting, it remains fixed.

Picturesque allegory is thus criticized in Diderot not so much for its departures from verisimilitude, as because it escapes the magical virtualities of what "can be".

Materiality of painting, metaphoricity of allegory

This materiality of the allegorical object in painting conflicts with the essentially metaphorical dimension of allegory. Regarding Vanloo's L'Amour menaçant, Diderot writes, in the Salon de 1761:

"I don't know, my friend23, if you've noticed that painters don't have the same freedom as poets, in the use of Love's arrows. In poetry, these arrows go off, hit and hurt. This is not possible in painting. In a painting, Love threatens with his arrow, but he can never throw it without producing a bad effect. Here, the physical is repugnant. Allegory is forgotten; and it is no longer a man pierced by a metaphor, but a man pierced by a real24 line that we glimpse." (P. 204.)

The effect of reality specific to painting materializes the image, stripping it of the virtuality necessary for allegorical manipulation. Indeed, according to Diderot, painting is transparent to reality, just as the idea, the virtual image, is transparent to text, to poetry. Painting cannot render metaphor, that is, the displacement proper to allegorical "pas-de-sens".

At bottom, and forcing the point, painting is unfit for allegory, not for reasons of propriety, but for reasons consubstantial with the pictorial medium. This is a far cry from Du Bos.

From then on, and this is the fundamental semiological issue of the Salon de 1767, Diderot will endeavor to dissociate poetry and painting, and order his thinking around the opposition of the "do" and the "ideal"25. The picturesque allegory brings into play only the "doing", i.e. the painter's technical virtuosity, but cannot represent the "ideal", the idea, through which the "verve", the artist's creative fury, is exercised. Indeed, the allegorical idea, the sublime idea, the grandiose idea, is essentially a virtual idea, an image that can be thought, not represented. This is the germ of thought through images.

The loss of meaning

Lagrenée's allegories provide Diderot with the opportunity for this realization and position. In the Salon of 1765, Lagrenée had exhibited two allegorical paintings that paralleled each other, La Justice et la Clémence and La Bonté et la Générosité26. Diderot is full of praise. Of the first, he says: "O le beau tableau! Praise the color, the characters, the attitudes, the draperies and all the details. The feet, the hands, everything is finished and of the most beautiful finish." (DPV XIV 82; Laffont 325.) Not a word on the meaning of these allegories; the praise is purely technical; only the mimetic effectiveness of the painting is targeted. Likewise for the second: "the characters of heads could not be more beautiful, and then feet, hands, flesh, life." (DPV XIV 84; Laffont 326.)

The heads are beautiful, but what do they characterize, what passion? Flesh is alive, but for what action?

These objections came only at the following Salon, where Lagrenée exhibited a series of allegorical paintings: first the Four States, commissioned by Mazade de Saint-Bresson, treasurer of the States of Languedoc; then Le Dauphin mourant.

From the outset, regarding L'Épée, ou Bellone présentant à Mars les rênes de ses chevaux, Diderot exclaims, "What does it mean? nothing, or not much" (DPV XVI 119; Laffont 553). Regarding La Robe, ou la Justice que l'Innocence désarme et à laquelle la Prudence applaudit, the same observation of a loss of meaning: "Était-il possible d'imaginer rien de plus pauvre, de plus froid, de plus plat? (DPV XVI 120; Laffont 554.) Allegory is incomprehensible; more precisely, allegorical figures, technically perfect, are not characterized by an idea that could particularize them. Their beauty is general, and hence insignificant. Lagrenée's insignificance turns his perfect beauties into horrors of ineptitude:

"If we think, if we dream of anything, it's the beauty of the touch, the draperies, the heads, the feet, the hands, and the coldness, the obscurity, the ineptitude of the composition. [...] Cursed writing master, will you never write a line that matches the beauty of your handwriting." (DPV XVI 121; Laffont 555.)

The criticism is strange: Lagrenée can draw, even letters, but he can't write.

He possesses the painter's faire, but not the ideal of the creator, who, whatever his art, is first and foremost a poet. Same observation for Le Clergé: "It's worse than ever. Another logogryph, colder, more impertinent, even more obscure than the previous ones." (Ibid.) The allegory turns to logogryph, a disparaging appellation for enigma. We find Du Bos's criticism here: but the enigma is not bad because it demands an effort of interpretation; it is bad for the poverty of what it gives to interpret.

Diderot then throws back onto the rest of the audience the attitude that had nevertheless been his own two years earlier: "Tout le monde accourt. Everyone admires. But no one asks, what does it mean." (DPV XVI 124; Laffont 557.)

It's not a question of rejecting allegory because it's incomprehensible, but of warding off allegory's slide into insignificance, due to the privatization, the gentrification of the great genres:

"little bélître, to whom then will you give grandeur, solemnity, majesty, if you give none to Religion, Justice, Truth. But," replies the artist, "don't you know that these virtues are a bit too much for a Receiver General of Finances? (DPV XVI 122; Laffont 555.)

Allegory does not accommodate a decorative function. Because it demands grandeur, the sublime, it recalls the primacy of idea over execution in representation.

Diderot repeats Du Bos's identification of great allegorical painting with Rubens: "Modern painters, abandon these symbols to the fury and brushwork of Rubens. Only the force of his expression and color can make them bearable." (DPV XVI 120; Laffont 554.) Here, Du Bos's criticism of Rubens turns to praise, even if Diderot, like Du Bos, still appears to distance himself from Rubens's allegorical practice. Still, this is where the strength of the idea lies, this fury, this poetic enthusiasm that has always constituted in Diderot, since reading Shaftesbury, the reference model for creative27.

Similarly, Diderot takes up the identification of allegory with the mot d'esprit, for a critique apparently aligned with Du Bos's: "Mr de La Grenée, sachez qu'une allégorie commune, quoique neuve, est mauvaise, et qu'une allégorie sublime, n'est bonne qu'une fois. It's a good word that's worn out, as soon as it's said again." (DPV XVI 123; Laffont 556.) On reflection, Diderot's identification of allegory with the bon mot does not disparage allegory, but rather condemns it to excellence. This uniqueness of the "bon mot usé dès qu'il est redit" is the very uniqueness of the trait, of that "pas-de-sens" peculiar to the witz and on which its effectiveness is founded. Allegory is of the order of the sublime word and thereby expresses the quintessence of this principial power of the idea.

About Durameau's Triomphe de la Justice, again in the Salon de 1767, Diderot remarks:

"but I claim that, he who throws himself into allegory, imposes upon himself the necessity of finding ideas so strong, so new, so striking, so sublime. Without this resource, with Pallas, Minerva, the Graces, Love, Discord, the Furies, twisted and turned in a hundred different ways, one is cold, obscure, flat and common." (DPV XVI 440; Laffont 766.)

For Diderot, allegory doesn't allow for simple typological manipulation of figures. It imposes the obviousness of the idea, and is the ideal medium for expressing sublime inventions. Here again, the formulations are reminiscent of Abbé Du Bos, yet express the exact opposite of what he says. According to Du Bos, good representation is plausible and, to this end, focuses exclusively on the expression of passions, i.e., on the typological manipulation that Diderot castigates in bad allegory (turning Pallas, Minerva, the Graces, etc.). On the contrary, according to Du Bos, allegory is criticizable because, breaking out of this manipulation within an agreed code and typology, it creates new figures, breaking out of the conventions of the known code to construct its own code, thus flirting with the incomprehensible. Yet it is precisely this out-of-code creation, this transcending of typologies, that inspires Diderot's enthusiastic support for sublime allegories. The allegory of Justice, for example, is not this "stiff woman [who] holds her scales in a prim manner" (DPV XVI 437 ; Laffont 764), a conventional, sullen figure, but the figure of Calas and his Histoire, whose "trait" is "capable of inviting [judges] to commiseration, to distrust; to make one feel the weakness of man, the atrocity of capital punishments, and the price of life" (DPV XVI 438; Laffont 765).

The allegory in this example is very much a feature, and a subversive one at that, placing in imagination the famous engraving of Calas's death on the wall of every court, making this denial of justice an emblem of justice.

From allegory to device

The subversive play sometimes saves the allegory in spite of itself, as in Lagrenée's Le Dauphin mourant:

"A large curtain was raised, and the dying dolphin was seen, stretched out on his bed, his body half-naked.

This idea of the dolphin behind the curtain made a fortune. The dolphin spent his whole life behind a curtain, and a thick one at that; it was Thomas who said it in prose. I said it in verse. It was Cochin who said it in engraving28. It is Lagrenée who says it in painting, after M. de La Vauguyon who had taught him to stand there." (DPV XVI 148 ; Laffont 572 .)

The Duc de La Vauguyon, who commissioned the work, was the Dauphin's tutor and himself imagined the composition, which he gave to Lagrenée to execute. The curtain device, classic in history painting29, makes sense here as a witticism despite the painter and his inspirer: the effect of the allegorical "bon mot" is triggered in reverse of the manifest intention, condensing all the epigrams.

Here, perhaps more visibly than elsewhere, the deconstruction of allegory is made up for by the scenic device: the visible order of the painting saves what the emptiness of the discourse it allegorizes had threatened. It's not a question of representing a discourse, but a scene: "it's a scene of manners, a family scene, a last scene of life, a pathetic and highly pathetic scene". (DPV XVI 149; Laffont 573.)Diderot seeks the virtual image that underlies the subject, that famous "idea" that lies at the principle of creation. But the image is not one; the characterization of the scene is an enumeration, a dissemination. The floating of the virtual image, the slip into imagination, contradicts the fixation, immobilization, focus that characterizes the image painted on canvas.

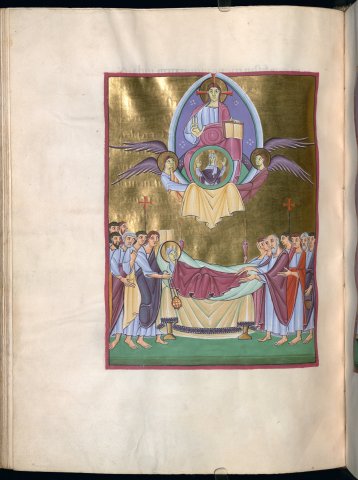

"that's what my fellow artists don't feel. They have in their heads, Ut pictura poesis erit; and they have no idea that it is even truer that ut poesis pictura non erit. What works well in painting always works well in poetry, but it's not reciprocal." (DPV XVI 150; Laffont 57330.)The curtain supported by two cherubs is borrowed from tabernacle iconography; it traditionally frames depictions of the Virgin. Here, Dormition of the Virgin, Pericopes of Henry II, 11th century, Munich, Bayerische Staatbibliothek, clm 4452, fol. 161v°. The cherubs support a mandorla with the Christ of Judgment, the Virgin Mary in the Byzantine model of the Virgin of the Blachernes and the veil of the tabernacle. Cherubs wearing the veil are more common in depictions of the Virgin in Majesty, the Adoration of the Magi, or apparitions of the Virgin.

To save allegory, Diderot abandons the ut pictura poesis31: allegory is detached, so to speak, from its visual support to become an inner exercise of thought, of a new thought, through images.

"Imagination moves swiftly from image to image; its eye embraces everything at once. If it discerns planes, it neither graduates nor establishes them. Suddenly, it will go to immense distances. Suddenly it will come back on itself with the same rapidity, and press objects onto you." (DPV XVI 151; Laffont 574.)

The eye of the imagination is opposed to the real eye by this global apprehension, this constitution of a network within a space that is, so to speak, de-geometralized: there are no longer any planes, depths, distances or stable separation between a looking eye and a looked object. Imaginary space is the space of instability, of scopic reversibility, which recovers the reversible, labile nature of the allegorical image.

Or this imaginary space is none other than Diderot's own creative imagination:

"Chardin, La Grenée, Greuze and others assured me, and artists do not flatter literati, that I was almost the only one of these whose images could pass on canvas, almost as they were ordered in my head." (DPV XVI 152; Laffont 574.)

Diderot recovers for himself the prestiges and powers of allegory. In 1767, it was still a question of thinking about paintings; but already the Salon de 1767 was filled with philosophical digressions. This thinking through images, cultivated by Diderot in contact with paintings, would become the thinking of philosophical dialogues.

Notes

On the notion of scenic device, see S. Lojkine, La Scène de roman, A. Colin, collection U, 2002 and La Scène. Littérature et arts visuels, dir. M. Th. Mathet, L'Harmattan, 2001.

Abbé Du Bos, Réflexions critiques sur la poésie et sur la peinture, 1719, 1733, École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, 1993.

Sigmund Freud, Le Mot d'esprit et sa relation à l'inconscient, 1905, French translation M. Bonaparte, 1930, 1969, trans. D. Messier, Gallimard, 1988, Folio essais, 1992.

On the "pas-de-sens", see Jacques Lacan, Séminaire V, 1957-1958, Seuil, 1998, chap. V, pp. 98-100.

This critique of allegory is inherited from the seventeenth century and the reaction against precious culture. One example is the Nouvelle allégorique, which Antoine Furetière published in 1659: "The dominion of this Kingdom [of Pedanterie] has been usurped by Captain Galimatias, an obscure man born of the dregs of the people [...]. As soon as these Troops [understand: these tropes] were in the enemy country, they capered in such a way that they easily led Prince Galimatias to declare war on Rhetoric. [...] The army was arranged like this: [...] The other battalion to the left was made up of Metaphors and Allegories." (Quoted inY. Hersant, La Métaphore baroque, Points-Seuil, 2001, pp. 134-135. Furetière's allegories bring together the constellation of words that would return quite naturally under Du Bos's pen.

See Leon Battista Alberti, De pictura, 1435, Macula, 1992, II, 41, p. 175: "Animos deinde spectantium movebit historia, cum qui aderunt picti homines suum animi motum maxime prae se ferent", history painting will arouse the emotion of those who look at it when the characters painted in it clearly bear the expression of their passion on their faces.

The rhetorical movere is thus articulated with its pictorial translation, the expression of passions (motus animi).

Du Bos here takes up the vulgate established by Le Brun. See Charles Le Brun, L'Expression des passions, Dédale, 1994 (lecture delivered in 1668 , published in 1680, 1698 and in 1727 with engravings).

Diderot's text is that of the edition of the complete works published by Hermann, abbreviated DPV. For the Salons, references have been added to the current edition of the Œuvres, tome IV (Esthétique-Théâtre), presented by Laurent Versini, Laffont, "Bouquins", 1996, abbreviated Laffont.

Perhaps it would be better to restore the autograph copy's singular "laisseroit", "qui" having "l'abbé Galliani" as its antecedent.

The young woman on the left, in Rubens' painting, is actually holding a cornucopia in which five marmots are chirping, representing Marie de Medici's five unborn children.

The young man on the right holding the newborn in his arms carries a snake wrapped around his right arm, the whole making up a kind of living caduceus that allows him to be identified as a Mercury-Asclepius, an allegory of the prince's good health.

Here, Diderot seems to have lost track of the painting. The rainbow could in fact refer to Apollo on his chariot in the upper left: Louis XIII will be a new Apollo. "Le Zodiaque, le Sagittaire" must refer to Sagittarius as the sign of the zodiac. But Diderot got the sign wrong: the young woman on the right, adjusting the child's diaper, is holding a pair of scales, which could be interpreted as an allegory for the star sign of Louis XIII, born on September 27. Libra is both the sign of Louis XIII and Themis, the Justice that must prevail in the new reign.

This was the obligatory commentary for this painting since Cassiano dal Pozzo. See Simone Alaida Zurawski, Peter Paul Rubens and the Barberini 1624-1640, UMI Research Press, 1980.

The reference to Horace is offbeat and prepares the turnaround. One would expect here the very first lines of the Art poétique, which condemn, in painting precisely, the disparate Chimera: "Humano capiti cervicem pictor equinam / jungere si velit", if to a man's head a painter wanted to join the neck of a horse...

Instead, Diderot refers us to verses 319-322: "Interdum speciosa locis morataque recte / fabula nullius veneris, sine pondere et arte, / valdius oblectat populum meliusque moratur / quam versus inopes rerum nugaeque canorae", sometimes a story with striking episodes and right morals, but without beauty, strength or art, gives more pleasure to the people and holds their attention better than verses poor in content and melodious trifles.

The moral content of the work takes precedence over its aesthetic success and, hence, homogeneity. Disparity becomes a secondary flaw...

DPV XIII 163-168.

See Ronald Forsyth Millen and Robert Erich Wolf, Heroic deeds and mystic figures, a new reading of Rubens' Life of Maria de' Medici, Princeton University Press, 1989, p. 76. In the Cycle de Marie de' Medici, Rubens had depicted the meeting of Henri IV and his wife in Lyon, where they consummated their marriage, by the arrival of a woman on a chariot drawn by lions. The allegory referred to Cybele, goddess of fertility, and to the lion/Lyon homonymy. This painting, immediately preceding La Naissance de Louis XIII, probably guided the association of ideas that led Diderot from "lit d'une accouchée" to "monument de Rheims".

Diderot had already alluded to Fontenelle's bon mot about Boucher's paintings in the Salon of 1765 (DPV XIV 56). Yet Boucher is the first painter he mentions, three lines later. "Sonate, que me veux-tu?" is here the implicit image that guides Pigalle's transition to Boucher, from the question of meaning to that of morals.

See Michael Levey, L'Art du XVIIIe siècle, Yale University Press, 1972, French translation, Flammarion, 1993, pp. 141-143.

"Diderot. [...] I take the statue you see, I put it in a mortar, and with great blows of the pestle...

D'Alembert. Gently, please. This is Falconnet's masterpiece." (DPV XVII 93.) See also S. Lojkine, "Le matérialisme biologique du Rêve de D'Alembert", Littératures, n°30, Spring 1994, PUM, Toulouse, pp. 27-49.

DPV XVI 64-65.

DPV volume XXIV is still unreleased.

This is chapter XXIX of part one in the DPV edition, which follows the original edition and places the four chapters added later at the end. See DPV III 131.

Diderot addresses Grimm.

Here, Diderot plays on the word trait, as marked by the addition of the adjective "réel": trait can also designate the witticism, the metaphorical construction constitutive of allegory.

See S. Lojkine, "De l'écran classique à l'écran sensible : le Salon de 1767 de Diderot", L'Écran de la représentation, L'Harmattan, coll. "Champs visuels", 2001.

To be compared, according to M. Sandoz, with Pompeo Batoni's allegorical diptych, Truth and Charity and Peace and Justice, at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Jacques Chouillet, La Formation des idées esthétiques de Diderot, A. Colin, 1973, pp. 60-61, and Diderot poète de l'énergie, PUF, 1984, pp. 14-15 and passim.

Antoine-Léonard Thomas, a specialist in the epidictic genre, frequented philosophers in spite of everything; he had won the prize of the Académie française, which had put the eulogy of the Dauphin up for competition. As for Diderot, he had proposed various projects to Cochin, first for engraving, then for sculpture. All these texts were eulogies, which Diderot here turns into biting satire.

See S. Lojkine, "La main tendue, le regard démasqué : théâtralité et peinture de Poussin à Greuze", Théâtralité et genres littéraires, La Licorne, Poitiers, 1996, pp. 93-114.

The Versini edition here gives a different, probably faulty text. Instead of "ut poesis, pictura non erit", painting does not function like poetry, "ut pictura, poesis non erit". There is negation, but also interversion: not only does Diderot's formula undo the parallelism of the arts, but it refocuses modeling around painting, which becomes the subject of the sentence.

On the surface (but only on the surface), Diderot reverses his position in the Loutherbourg article in the same Salon of 1767, which bears the epigraph Ut pictura, poesis erit. But in the Loutherbourg article, Horace's verse is taken in its original sense, not in the reversed sense given to it by the Renaissance (see on this subject R. W. Lee, Ut pictura poesis, Norton, 1967, French trans., Macula, 1991): it's not a question of subjecting painting to the demands, the compositional standards of poetry, but rather of poetry developing its own faire, "its palette" (DPV XVI 383; Laffont 732). Taking up the type of analysis inaugurated with regard to the poetic hieroglyphs of the Lettre sur les sourds, the Loutherbourg article thus insists on the effects proper to the support-text: rhythm and harmony constitute the poetic image in the same way as color determines the painted image. Admittedly, these means are parallel, but they are heterogeneous.

The divorce has even deepened: poetry is no longer transparent to the idea, to the ideal, even if "It is nature and nature alone that dictates the true harmony of an entire period" (DPV XVI 385; Laffont 733).

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « De la figure à l’image : l’allégorie dans les Salons de Diderot », in Allégorie, Edward Nye (ed.), Studies on Voltaire and the eighteenth century, 2003:07, Voltaire foundation, Oxford, p. 343-370.

Diderot

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Diderot

Les Salons

L'institution des Salons

Peindre la scène : Diderot au Salon (année 2022)

Les Salons de Diderot, de l’ekphrasis au journal

Décrire l’image : Genèse de la critique d’art dans les Salons de Diderot

Le problème de la description dans les Salons de Diderot

La Russie de Leprince vue par Diderot

La jambe d’Hersé

De la figure à l’image

Les Essais sur la peinture

Atteinte et révolte : l'Antre de Platon

Les Salons de Diderot, ou la rhétorique détournée

Le technique contre l’idéal

Le prédicateur et le cadavre

Le commerce de la peinture dans les Salons de Diderot

Le modèle contre l'allégorie

Diderot, le goût de l’art

Peindre en philosophe

« Dans le moment qui précède l'explosion… »

Le goût de Diderot : une expérience du seuil

L'Œil révolté - La relation esthétique

S'agit-il d'une scène ? La Chaste Suzanne de Vanloo

Quand Diderot fait l'histoire d'une scène de genre

Diderot philosophe

Diderot, les premières années

Diderot, une pensée par l’image

Beauté aveugle et monstruosité sensible

La Lettre sur les sourds aux origines de la pensée

L’Encyclopédie, édition et subversion

Le décentrement matérialiste du champ des connaissances dans l’Encyclopédie

Le matérialisme biologique du Rêve de D'Alembert

Matérialisme et modélisation scientifique dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Incompréhensible et brutalité dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Discours du maître, image du bouffon, dispositif du dialogue

Du détachement à la révolte

Imagination chimique et poétique de l’après-texte

« Et l'auteur anonyme n'est pas un lâche… »

Histoire, procédure, vicissitude

Le temps comme refus de la refiguration

Sauver l'événement : Diderot, Ricœur, Derrida

Théâtre, roman, contes

La scène au salon : Le Fils naturel

Dispositif du Paradoxe

Dépréciation de la décoration : De la Poésie dramatique (1758)

Le Fils naturel, de la tragédie de l’inceste à l’imaginaire du continu

Parole, jouissance, révolte

La scène absente

Suzanne refuse de prononcer ses vœux

Gessner avec Diderot : les trois similitudes