I'd better warn the reader from the outset : the following lines will teach him nothing about eighteenth-century Russia. Worse still Leprince's painting says very little. Yet it was his trip to Russia that made Leprince famous it was on this trip and the sketchbooks he brought back that he built his entire artistic career. Unlike the chinoiseries of a Boucher or the turqueries of a Vanloo, Leprince's " russerries " (the term is his) derive from real experience, corresponding to real mores, real places.

.We'd like to ask here how, in the unrealistic space of classical representation, the notion, the idea of the document is born in the eighteenth century, how the rococo painter's pastoral fantasy can be led to claim to be a painting of Russia, proceeding from an ethnographic survey. Yet Leprince makes no radical transformations: between kitschy shepherds' huts and the seen scene, he remains in an ambiguity from which his audience did not wish to emerge. On the painter's intentions, on his approach, we have virtually no documents on the other hand, on the reception of his work, we have a choice testimony : these are Diderot's comments, notably the reviews of the Salons of 1765 and 1767.

.After briefly tracing Leprince's career, we'll show how Diderot's very lukewarm commentary, confronted first with the strangeness of Russian manners and then with the exhibition of Russian clothing, draws on this forced, unseemly presence of the referent to implement a new, unmediated relationship to painting.

Leprince and the trip to Russia

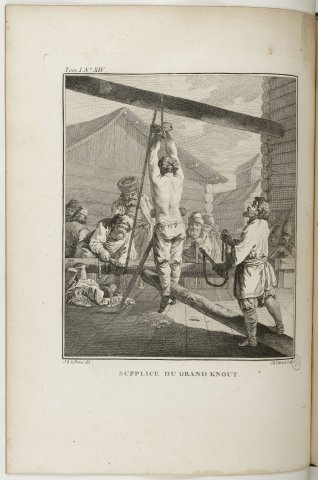

Jean Baptiste Leprince1 was born in Metz on September 17, 1734. Thanks to the protection of the governor of Metz2, the marshal of Belle-Isle, who granted him a pension, he became a pupil of Boucher. If his early works are to be believed, in 1754 he undertook the traditional pilgrimage to Italy: but he may well have been inspired for these views of Italy by the engravings of Piranesi. In any case, in 1757, fleeing the difficulties of an unhappy marriage concluded out of necessity with an older and wealthier woman, Marie Guiton, he left for Holland, from where he went to Russia in 1758, escaping an attack on his ship by privateers thanks to the composure with which he played his violin during the boarding (L. Réau). Leprince stayed in Russia from 1758 to 1763: from St. Petersburg, where he painted some door-tops and ceilings for the Winter Palace, he traveled to Moscow, Riga, Livonia, Finland, visited the Samoyeds and is said to have pushed as far as Eastern Siberia and Kamchatka3. He is thus " the first French artist to have ventured outside the completely Frenchized circles of the Russian court to record the habits and customs of the countryside " (P. Stein). The concordance of dates has sometimes led to the assumption (wrongly, it seems, and in any case without proof) that he accompanied Abbé Chappe d'Auteroche on his Siberian mission, commissioned by the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris, to Tobolsk to observe the transit of Venus over the sun, scheduled for June 6, 1761: Chappe d'Auteroche brought back from his fifteen-month expedition an account that is a veritable picture of Russian manners, /// which he had printed in three folio volumes illustrated with engravings after drawings by Leprince, Moreau le Jeune and Caresme de Fécamp4.

Returning to Paris at the end of 1764, Leprince brought back from his trip to Russia a whole supply of drawings that would feed, during the twenty years of his career as a painter and engraver, the genre paintings and Russian landscapes by which he became famous. In addition to the paintings he regularly exhibited at the biennial Salons of the Académie royale de peinture (he was approved in 1765 with Le Baptême russe as his reception painting), Leprince executed the cartoons for a six-piece hanging entitled Les Jeux russiens for the Beauvais manufacture, which was woven several times from 1769 onwards. He also devoted himself to engraving5, perfecting in 1768 the aquatint technique invented by his fellow Lorraine native Jean-Charles François to imitate wash drawings. Housed at the Louvre, where he befriended his neighbor the sculptor Pajou, Leprince in 1781 retired to the countryside with his niece Marie-Anne Leprince, to Lagny, where he died on September 30.

Illisibility of Leprince

Here, then, is a pupil of Boucher, the most delightfully artificial of the Enlightenment painters, the most insolently ignorant in his painting of the reality of the world, who makes himself a painter of Russia and builds his entire oeuvre on the least rococo of journeys. Yet Leprince's painting in no way breaks with his master's style and aesthetic. This is the fundamental ambiguity of his artistic project6.

Contrary to Boucher, who practiced it, Leprince is not a history painter ; he does not create in the noble sphere of representation, where the painted image holds the universal discourse of culture, where its device, idea or ideal is supposed to translate indifferently into the linearity of a narrative or the overall, spatial effect of a visual composition. Diderot's most popular canvases, Le Berceau pour les enfants and Le Baptême russe in particular, belong to genre painting, which does not develop from this pre-existing culture, shared by the creator and his audience. The viewer is led not to decipher, but to construct the discourse of the image, not to find, but to conjecture, to establish history. Genre painting produces its own discourse it internalizes, it autonomizes its hermeneutic code.

As for the landscape, through which Leprince attempts to rival Vernet, he tends squarely to economize on culture. Landscape is without history : the eighteenth century gradually evacuated from landscape all the mythological landmarks that Claude Le Lorrain still had there in the previous century. What remains is architecture, which, in the absence of fiction, makes it possible to historicize the landscape, to inscribe it in a civilization : in 1765, for example, Leprince exhibited a Vue d'une partie de Pétersbourg, Le Pont de /// Nerva7, or a View of a mill in Livonia ; in 1769, it's the Cabak, or sort of guinguette in the vicinity of Moscow8.

What does this district of a faraway town, this bridge or mill from elsewhere, this guinguette with a name that says nothing mean to a French audience? The exoticism of the location provides the performance with an alibi of historical inscription, while at the same time obscuring its legibility. The exotic stage displays the charm of the incomprehensibility of its code already in the intimacy of the seraglio or in the gestures of the tea ceremony, the audience wasn't trying to learn about another culture, but was enjoying the relief of not having to read and play the conventions of a foreign world. Exoticism is a safe-conduct and a vacation from deciphering. In the Salon de 1767, Diderot's article on Leprince immediately precedes that on Hubert Robert, in which the philosopher develops his poetics of ruins: like the mill in Livonia or the bridge in Nerva's obscure town, Robert's ruins deconstruct history as medium and support of representation. Only the cause of the strangeness changes. But in both cases, what can be read from or in the image becomes incomprehensible: the monument, the inscription, the very use of the place sink into illegibility.

.On a semiological level, the autonomy of the image is at stake here, as it begins to function as an autarkic medium, adopting its own language, then dispensing with all language, addressing itself directly to the eyes. In referential terms, what is communicated is no longer essentially of the signified order, of representation. Painting introduces the dimension of the real, no longer at its margins, as a jewel case from which to adorn, set, dress representation, but as a central issue, as an object in its own right : it becomes an image of, and for example an image of Russia.

The problem of morals

The way Diderot reports on Leprince's paintings is characteristic of this mutation. Should we treat these bucolic subjects as pastorales, i.e. as a variation on the common cultural background constituted by theater, opera, decorative painting, lyric poetry and late epic, where shepherds' idylls constitute abstract representations in an unreal, codified world, or do these Russians in Paintings show us a real Russia, constitute a document9 ? Is Leprince's Russia an avatar of rococo turquerie, a pretext for the derealization constitutive of representation, or is there in itself an image of Russia that makes sense as a new, unprecedented referent, that communicates a description of manners, that lays the foundations for ethnographic investigation ?

Diderot approaches Leprince from the old world of common culture with its shared codes and honed histories. In Leprince's article in the Salon de 1765, the image of Russia is considered only negatively, as something to which he has no access : " Je ne réponds point des imitations russes, c'est à ceux qui connaissent le local et les mœurs du pays à prononcer là " (DPV XIV 223). To be read, the image of Russia presupposes knowledge of a code that is lacking, a key that is missing Its strangeness is indecipherable. " Songez, mon ami, que je laisse toujours là les mœurs que je ne connais pas " (DPV XIV 225) : Diderot refuses to consider the documentary dimension of this painting, and the ignorance he invokes reflects, if not dismay, at least annoyance at what is perceived as artistic incongruity. In fact, this annoyance bursts forth frankly on the following pages. Regarding Nerva's Vue d'un pont de la ville, Diderot exclaims : " ce sera, si l'on veut, le /// subject of a good plate in a travel writer10, but it's a detestable thing in painting " (DPV XIV 228). This is not the role of painting : the narrative emptiness of the document stands out in the culturally saturated world of painting ; " with the most rigorous imitation of manners it means nothing " (DPV XIV 229).

However, as Leprince's world, with its abundant output, becomes more and more apparent to Diderot, the art critic modifies his attitude. Instead of rejecting wholesale what manifests itself to him as an image of Russia, that is, of something foreign, unknowable, from outside painting, Diderot accommodates his discourse : the Halte des Tartares marks the moment of this shift.

" If morals are true, this piece may interest by there, of the rest, it is little. Objects are linked here only for the eye, no common action linking them. Indeed, what do this passing carriage, this standing woman, this seated man, this traveller on horseback have in common? What do they have in common with a stopover or the main subject? Nothing you can feel. This is placed there as in a genre painting a handkerchief, a cup, a saucer, a bowl, a fruit basket, and unless there is in the genre painting the greatest truth of likeness and the most beautiful faire, and in a landscape such as this one a great beauty of site with the most rigorous imitation of manners, it means nothing. " (DPV XIV 228.)

These are the harshest terms. Discourse on painting brutalizes it, crushing it and denying it precisely for what it is, which is not of the order of discourse : " c'est peu de choses " ; " cela ne signifie rien ". There are no comprehensible links between the objects, i.e. no familiar codes to help interpret the scene. Yet the picture is not badly composed but " the objects are linked only for the eye " ; there is a logic to the image, which is not relayed by any known story. But this logic, with no history, no text, has its place in painting it's that of the still life. Diderot still speaks of genre painting, but in the very next painting, he takes the plunge: " I'm going to describe this painting as if it were a Chardin ".

.The document enters painting by default, as a degree zero of representation. But Chardin is a very great painter, recognized by Diderot as such. Once read as Chardin, Leprince's painting can begin to exist as a painting of Russia and take on value as an image of Russia. Timidly, those mores that Diderot had dismissed from the outset as unknowable make a comeback as values, as positive elements of authentication and appreciation of painting.

This critique of the unbinding of objects should not be misunderstood. It certainly marks a distrust, a misunderstanding it perhaps indicates a flaw ; but it defines, first and foremost, the genre that Diderot assigns to this painting, the off-genre genre of still life, which, even in Chardin's work, manifests itself as the limit and critique of classical representation, a critique that is mute but radical in its economy of action, i.e. of that which provides the interface between text and image, the transparent shift from the discursive linearity of a narrative to the visual globality of a linking device, articulating characters and objects on canvas. What Diderot is pointing out here is the absence of this discursive articulation of objects, i.e. the impossibility for these Russian canvases to reproduce a common cultural narrative. By pretending to regard Leprince's painting as still life, Diderot is not simply punishing a bad pupil of the Académie royale: he is pointing out the irreducibility of this ethnographic painting to the classical codes of representation, deconstructing the code in order to make it a work of art. /// to make something new appear, to show, if only negatively, that dimension of mores, that documentary strangeness that constitutes Leprince's originality and has ensured his success.

.For that matter, the honest man's disdain for the trivial realities of painting manners soon gives way to the curiosity of the encyclopedist on the lookout for the world's knowledge, when confronted with Manière de voyager en hiver11 :

" All we're learning here is how cars are built in Russia. I do not know whether these curved sticks would not be of very good use in this very country, especially in the provinces where the roads are united and ironed, with the precaution of fitting large iron wheels to them. " (DPV XIV 229.)

Here we find the author of the Apricot article giving us his recipes for candied fruit, or the Bas article, explaining the workings of the most sophisticated loom of the pre-industrial era : Russian sleigh cars are neither more nor less exotic for the philosopher's cultured, polite, urban readers.

The Russian Baptism, or autofiction as code supplement

The end of Leprince's article on the Salon of 1765 is devoted to the Russian Baptism, the most dazzling of the painter's productions exhibited that year, his reception piece, and one of the Salon's most talked-about paintings. A choice painting, an exceptional commentary : Diderot is not content with a critical examination ; he sets up a veritable anthological banter.

It's first a question of setting the scene, that is, establishing the code, the symbolic mesh in which this representation comes to be inscribed :

" The Russian Baptism. From the same. Here we are. My goodness, it's a beautiful ceremony. That big silver baptismal font makes quite an impression. The function of these three priests, who are all on the right, standing, has dignity : the first embraces the newborn under the arms and plunges him by the feet into the basin the second holds the Ritual and reads the sacramental prayers, he reads well, as an old man should read, keeping the book away from his eyes the third looks attentively at the book ; and this fourth who pours perfumes on a burning pan placed towards the baptismal basin, don't you notice how well, richly and nobly dressed ? how natural and true his action is? You'll agree that these are four very venerable heads... " (DPV XIV 236.)

Beautiful ceremony, bel effect ; the second priest reads well ; the fourth, don't you notice how well he is? Circulating between the Beautiful and the Good, the rhetoric of praise displays all its lights : in keeping with the tradition that makes ekphrasis an epidictic genre, Diderot celebrates repetition and the perfection of the code : criticism belongs to another genre and is out of place. The painting is " du même " : the formula, anodyne and repeated from article to article in almost all of Diderot's Salons, speaks of redundancy and familiarity, and says so here all the more as we reach the last painting in the Leprince article. " Here we are " : The Russian Baptism is expected, as the highlight, as the sensational event that will crown this Russian journey. " Here we are " crowns the rumor that accompanied the face-to-face encounter with the work, suggests the gathering and the sensation. The canvas is already there, it already constitutes a worldly event : encomiastic amplification feeds on this repetition, this familiarity of an expected world with known codes.

Diderot's description starts neither from the foreground, nor from one side of the canvas, but from what constitutes its focal point, the baptismal basin, just as the cradle constituted the focal point around which the entire representation was concentrically organized in Le Berceau pour /// les enfants, n° 150 du Livret12. The tank is the real object from which the symbolic network of rites and social ties is built. The description is organized to progress from the real to the symbolic, from the most concrete gestures to the most abstract, even hidden meanings.

The first priest is the one who materially baptizes the newborn by immersing it in water : he " embraces " the child, i.e. he embraces it with both hands. The Russian exoticism of the gesture is barely perceptible : the child " plunged[e] by the feet into the tub " will be baptized by immersion, according to the Greek rite13, and not by sprinkling, as in the Latin church.

The second priest " reads the sacramental prayers " : we move on to the symbolic dimension of the rite, but Diderot appreciates it from a perspective that is neither ethnographic nor even religious. While all the exoticism of the scene derives from the strangeness of the melody chanted in Slavonic, Diderot praises the posture of the old man reading, the truth of the presbyter's gesture, a truth both intimate and transcultural, which has nothing specifically Russian about it. The commentary thus brings back the strangeness of unknown mores to the familiarity of an intimate experience universally shared.

The same is true of the fourth priest : passing quickly over the incense he spreads in the church, one of the most typical elements of Eastern liturgy nonetheless, Diderot insists on the technical quality of the rendering of clothing and gesture, a quality that brings painting back to a common, known practice and standards. At the same time, the enunciation changes : the distanced, third-person description is now addressed to a virtual interlocutor, with whom the critic seeks to establish a connivance : " ne remarquez-vous pas comme il est bien " " vous conviendrez que... "

Here a change of strategy is afoot : the erasure almost to the point of denial of Russian mores will no longer be compensated for by the mere technical appreciation of the artist's " faire ", which has hitherto led Diderot to treat Leprince's painting as still life, but by the construction of a virtual social space in which to integrate these new characters, of a hybrid scene, part of the painting, part of Diderotian fiction. Through this fiction in which he stages himself, Diderot will first continue to supplement, then finally integrate the dimension of manners.

The dialogue that opens after the description of the four priests thus integrates the strangeness, the heterogeneity of the referent by echoing it in the mode of banter :

" But you don't listen to me, you neglect the venerable priests and the whole holy ceremony, and your eyes remain fixed on the godfather and godmother. I don't begrudge you this it's certain that this godfather has the most frank and honest character imaginable if I find him outside of here, I'll never be able to resist seeking out his acquaintance and friendship : I'll make him my friend, I tell you. "

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Jeroboam sacrificing to idols, oil on canvas, 111.5x143.5 cm, Paris, École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts

To the dialogical φιλία established by the interpellation of a fictitious interlocutor, Diderot ups the ante by seeking and promising friendship with the baptismal godfather. The two fictitious intimacies /// have the same aim: to communicate and unify the space of the viewer (the eye and the judgment of the critic) and the space of the canvas. The other in the dialogue has already entered further into the scene depicted. One foot in the Salon with Diderot, one foot in the church with the characters, he constitutes the visual clutch that some painters install laterally in the foreground of their compositions, looking at the scene just ahead of the audience who will contemplate the canvas.

.As for Diderot's choice of the godfather as future friend, it's a strange one : this one, placed in the shadows behind the godmother, looking at nothing and no one, his eyes vague and his smile extinguished, hardly invites sociability ! Not a word, of course, about the swarthy complexion and arched eyebrows of this oriental face, which has nothing Russian about it and which Leprince probably brought back from his Siberian notebooks. Not a word either of the child, even more typical, who faces us in the left foreground. Diderot would later evoke him, in the wrong sense of the word " This young man I see behind the godfather is either his page or his squire ". But this is not a servant carrying his master's arms and luggage behind him the child is taking the sword, which is forbidden to be worn in church, out of the church, along with his heavy winter clothes. Indeed, as Voltaire reminds us, " such was the ancient custom [...] of presenting oneself neither in church nor before the throne with a sword, an oriental custom, opposed to our ridiculous and barbaric custom of going to speak to God, kings, friends and women with a long offensive weapon that descends to the bottom of the legs14. "

We can see here how Leprince's approach contrasts with Diderot's. The painter may have been inspired for this reception piece, in which he had to show not only his skill but his pictorial culture, by a work by Fragonard that had been awarded a prize in 1752 by the Royal Academy of Painting, Jeroboam Sacrificing to Idols, currently housed at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris15. This work seems to have inspired Fragonard himself for his Corésus et Callirhoé, exhibited at the Salon at the same time as Le Baptême russe.

Jean-Baptiste Leprince, The Russian Baptism, oil on canvas, 76x97 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. 7331

To the golden calf altar corresponds in Leprince's painting the baptismal basin16, while the godfather and godmother couple occupy the place of the prophet and the woman spectator, on the left. Finally, the figure in red, seated with his back to the foreground in Fragonard, is replaced by the priest preparing incense in Le Baptême. The ample Russian garments are very similar to the biblical tunics. As for the dais that isolates the restricted space of the ritual from the vague space from which it is observed, it is found naturally in all three paintings. However, it's hard to say for sure whether they're borrowings: the subjects are too different, and it's more the overall composition than any particular detail that's in evidence. What is certain is that Leprince adopts a familiar and expected basic layout, that he implements a scenic organization of space characteristic of classical history painting. This construction, this artifice, forms the basis of the representation, which is then adapted to the subject, which is the subject of a permitted variation, a moderate departure from the expected mimetic framework: instead of the beggars sitting in the shadows in /// Left in Fragonard's Jeroboam, Leprince places the child with the sword, meant to perform the same transitional function between vague and restricted space. Whereas Fragonard's beggars are insignificant, fulfilling only an ordinary structural role, the Oriental-style child, performing an action that refers to a specific trait of morality, constitutes the canvas as a document and introduces the dimension of the referent onto the scene of representation. Leprince slightly diverts a composition derived from common culture towards ethnographic particularization, while Diderot erases this particularization and instead brings the exoticism of the representation back to a common, familiar space of sociability.

But the banter can't stop there the reader awaits the opening of an erotic game. From connivance with the dialogic interlocutor, we've moved on to the promise to seek the godfather's friendship only to come to libertinage with the godmother. As the network of affective ties becomes tighter and more complex, the gap widens between what is woven in the dialogical space and what is played out on the pictorial stage of representation :

" For this godmother, she's so kind, so decent, so gentle... - That I'll make her, you say, my mistress, if I may. - And why not? - And if they're married, here's your good friend the Russian... - You're embarrassing me. But if I were the Russian, either I wouldn't let my friends get too close to my wife, or I'd have the justice to say My wife is so charming, so lovable, so attractive... - And you'd forgive your friend ?... - Oh no. But isn't this a very edifying conversation, all the way through the most august ceremony of Christianity, the one that regenerates us in Jesus Christ, by washing us clean of the fault our grandfather committed seven or eight thousand years ago ?... " (DPV XIV 237, continued from previous.)

From libertinism with the godmother to " the most august ceremony of Christianity ", the gap widens. This gap transposes another, the gap between Russian mores and the French system of performance codes, the hiatus between document and performance stage. The transposition reduces the gap to a game between two equally familiar worlds: it's no longer a question of Russeness, but of eroticism and baptism, i.e., a conflict between two familiar worlds, two heterogeneous symbolic systems from which all strangeness and exoticism has been banished. The dialogue merely prepares the situations that will form the material of the Paradoxe sur le comédien, these erotic or trivial asides by the actors through the most pathetic of theater scenes17. Diderot progressively placed aesthetic pleasure in this hiatus between the artifice of representation and the rise, the irruption of the real : but the ambiguity always remains, in the relationship to painting as in the reflection on theater, of the playful, even libertine, deviation within the authorized limits of classical representation, or of the fundamental semiological mutation making the document the new scenic paradigm.

.Textile saturation

The Leprince article in the Salon de 1767 does not return to the question of the strangeness of Russian mores. The problem has shifted. The first works announced in the Livret, whose order Diderot follows for his critical account of the exhibition, are tapestry cartoons :

" Leprince is not without talent ; and the one who knew how to do the Russian Baptism is an artist to be regretted. Why is his color, so warm in his reception piece, dirty and ineffective here ? the answer is that this painting was destined for a tapestry factory. We had to wait, squeeze the paintings and display the tapestries. The same could not have been said of those painted by de Troy and the Vanloos for the Gobelins, nor of the Resurrection of Lazarus, nor of the Meal of the /// pharisien, by Jouvenet, nor du Baptême de J.-C. par St Jean, by Restou. The only way for a copy, however it is made, to be of great effect, is for there to be more in the original than less. Thus, the only excuse is the one we thought should be printed in the booklet" (DPV XVI 302-303.)

Beyond the criticism of color, which is recurrent in Diderot's treatment of Leprince18, it is the decorative function of painting that is targeted here and provokes the critic's bad temper19. Does he not elsewhere inveigh against Hallé, Lagrenée or Boucher, who earn their living painting tabletops and adorning gallant boudoirs, instead of creating the ideal machines of the grand manner20 ? Diderot purposely invokes tapestry cartoons from history painting as counterexamples, the antithesis of Leprince's rococo pastorales.

From the Berceau ou le réveil des petits enfants (which would be either the oval Hermitage painting21, or a lost replica of this painting), this criticism of colors is accompanied by remarks on clothing : " But one thing I am quite curious about, and which I may know one day, is whether this luxury of clothing is common in the Russian countryside " (DPV XVI 307). Already in the Salon de 1765, Diderot was astonished at the disproportion between the poverty of men and the richness of women's clothing : " Voilà bien la chaumière du paysan, mais il est trop grossier, trop pauvrement vêtu pour que cette vieille femme soit sa femme. [...] Could it be that in Russia, wives are good and husbands are bad ? " (DPV XIV 233.) And further on : " this peasant woman is also very well dressed, note that, it's as in the previous picture. " Although Diderot never mentions Boucher in his comments on Leprince, it is indeed this filiation that is intended, as can be seen from the comparison we can make with what he wrote about Boucher's pastorales and landscapes in the Salon de 1761 :

" One wonders, but where have we seen shepherds dressed with such elegance and luxury ? what subject has ever gathered in one place, in the middle of the countryside, under the arches of a bridge, far from any habitation, women, men, children, oxen, cows, sheep, dogs, bales of straw, water, fire, a lantern, stoves, cauldrons ? what is this charming woman doing there, so well dressed, so clean, so voluptuous ? [...] what a racket of disparate objects one feels all the absurdity ; with all this one cannot leave the picture. " (Salon de 1761, DPV XIII 222.)

As can be seen, before 1765, Diderot had not yet made a clear statement against Boucher, whom he castigated in 1765 and in the preface to the Salon de 1767. Similarly, his tone hardens against Leprince in the article in the Salon de 1767. With reference to two Russian-style gallant counterparts featuring a girl, a letter, a matchmaker and a young man, the slightly snide questioning turns to scathing reproach :

." If all you hear is fabrics and fitting, leave the Académie, and make yourself a store girl at Au Trait galant, or a master tailor at the Opéra. To speak to you without disguise, all your great paintings of this year are to be made, and all your small compositions are only rich screens, precious fans. There's no other interest in looking at them than the one we take in the bizarre attire of a stranger passing in the street or showing up for the first time at the Palais Royal or the Tuileries. However well-fitted your figures may be, if they were French, they would be passed over with disdain" (DPV XVI /// 313.)

Clothing kills the ideal. It transforms the stage into a fashion show, undoes the space of representation in favor of a curiosity for the eye that reduces the canvas to its textile materiality, to a matter of texture, cut, color. Whether destined for a wall tapestry or a fireplace screen, or reproduced on a fan that beats the air in a chic boudoir, the canvas no longer conjures up the illusion of depth and a theatrical moment; rather, without the mediation of a fiction, it is directly addressed to the eye, for pure, detextualized scopic satisfaction. This is the ambiguity of rococo, which undoes and flattens22 the space of representation, but at the same time opens up a new use for the eye, a material, textile, colorful apprehension of things. The rococo canvas becomes a surface saturated with things and, in so doing, without itself going that far, it prepares the advent of the dimension of the referent, of what will show itself in its raw state : a jar or a fruit by Chardin, the strangeness of a view brought back from a distant country.

For there is a brutality to rococo. The feminine mawkishness of these textile saturations conceals what began as pillage. About the second counterpart, Diderot writes :

.

" Same richness of fit, same flatness of heads that would like to be painted and aren't23. If a Tartar, a Cossack, a Russian saw this, he'd say to the artist, you've looted all our wardrobes, but you haven't known one of our passions. "

The rhetoric of the passions belongs to the old world of classical representation, which rococo aesthetics undid. The new world presents itself first of all negatively, as a disarticulation of reality, as a pillage of wardrobes.

But just as the denial of Russian mores, in the Salon of 1765, was eventually turned, through gallant autofiction, into the promise of Russian travel, love and friendship, so the annoyance at the display of dressed-up clothes is reversed, at the end of Leprince's article in the Salon de 1767, into a long digression on the problem of costume in painting, where Russian clothes, closer to the antique than French ones, are finally rehabilitated :

" If this artist had not taken his subjects from mores and customs whose manner of dress, clothing24 have a nobility that ours do not and are as picturesque as ours are gothic and flat, his merit would vanish. Substitute for Le Prince's figures Frenchmen adjusted to the fashion of their country, and you will see how much the same paintings, executed in the same way will lose their price, no longer being supported by details, accessories so favorable to the artist and to art. " (DPV XVI 320.)

The idea is not original. It can be found in Hogarth's The Analysis of Beauty (1753) and Leprince himself takes it up25. As for the praise of antique costume, it's a veritable Enlightenment commonplace26. But that's not the whole point: in this way, Diderot once again succeeds in assimilating Russian strangeness into the familiar interplay of classical codes of representation. Instead of flattening the scene, of lowering the painter's ideal to the tailor's, " l'habillement des Orientaux " (p. 321) restores the antique simplicity of the grand manner. It is we who are ridiculous with our clothes :

" Imagine in a heap at your feet, all the remains of a European, these stockings, these shoes, this cultotte, this jacket, this habit, this hat, this collar, these garters, this /// chemise ; c'est une friperie. " (DPV XVI 322.)

Let's not forget that a few pages earlier, Leprince was summoned to become a master tailor at the Opéra ! So the thrift shop changed sides. Without warning, as is his wont, Diderot has reversed the roles, but he integrates Leprince's russianisms only at the cost of erasing the Russian singularity. The dimension of the document is only accepted once the critic has made his exotic disconvenience coincide with the most classical requirements of representation27.

Boucher's legacy

Are we to conclude that Diderot didn't understand Leprince's work, or that he betrayed his intentions ? In any case, Leprince's Russia is neither more nor less Russian than it becomes under the critic's pen, and the pleasure of the exotic departure, which ensured the painter's success and notoriety, only very insidiously and indirectly calls into question the framework and functioning of the classical space of representation.

The painter's work is not a work of art, but a work of the critic.

Let's take as an example the tapestry of La Bonne Aventure, the carton of which was exhibited at the Salon of 176728. This tapestry is part of a series entitled Les Jeux russiens commissioned from Leprince by the Beauvais manufacture and comprising six subjects. Two other cartoons from this series were exhibited at the 1767 Salon, Une Jeune Fille orne de fleurs son berger pour prix de ses chansons (the tapestry would be entitled Le Musicien) and On ne saurait penser à tout (La Laitière in the final version). Leprince did not exhibit the last three cartoons, for Le Dénicheur d'oiseaux, Le Repas and La Danse, at the Salon of 1769, perhaps because of the lukewarm reception the first three had received in 1767.

It would be an understatement to say that the Russia represented in La Bohémienne, as indeed in the other compositions of the Jeux russiens suite, is a very un-Russian operetta Russia. The commission for the Jeux russiens renews in the same vein that for Boucher's Fêtes italiennes, a series woven by Beauvais from 1736 to 1762. The title of the Jeux russiens is modeled on that of the Fêtes italiennes itself established on the model of Watteau's Fêtes galantes or André Campra's Fêtes vénitiennes, a 1710 opera-ballet on a libretto by Antoine Danchet. The program, as advertised and intended, is indeed pastoral entertainment in a world of pure kitsch fantasy. Moreover, the theme of each of the compositions in no way refers to a range of specifically Russian realities, but rather to the program established by Boucher : La Bonne Aventure takes up the theme of La Bohémienne, Le Repas is to be related to La Collation, Le Dénicheur d'oiseaux constitutes only a slight variation on the Jardinier. Leprince's models are not about things seen, but already about representation29.

The subject of La Bonne Aventure is, however, an innovation for the Pastoral world, where it introduces new characters. But this innovation is neither Russian, nor Leprince's doing. At the same time, the Manufacture de Beauvais commissioned Casanove to produce a series on Les Bohémiens ; that's enough to say that the subject was fashionable and made sense as a symptom of an aesthetic mutation. Significantly, No.1 in the 1769 Salon Booklet is a Marche de Bohémiens by Boucher30.

The depiction of a Bohemian woman taking the hand of a young man, then a young girl, can be traced back to Caravaggio and, from there, developed in all the ramifications of Caravaggesque painting and its heirs : Vouet, Régnier, Valentin de Boulogne, Georges de La Tour, or, in Flanders, Cossiers painted it31, not to mention the many engravings on the subject32. But the Caravaggesque treatment of the theme favors the study of the figures' physiognomies, cut at mid-body and set against an almost plain background. This is another vein that will enable the construction of a representational space in which to set up a genre scene, strictly speaking: the bambochade33, to which Sébastien Bourdon's La Bonne Aventure belongs34.

From then on, the fortune-teller is no more than an element in the painting, where she comes to signify the triviality of the world represented.

Boucher's composition for the series of Fêtes italiennes commissioned by the Manufacture de Beauvais inherits this tradition of the bambochade to some extent: seated in the center in front of her sheep, holding her houlette between her knees, a shepherdess with a ribbon around her neck reaches out to a young Bohemian woman, placed on the right and carrying a child on her back. The child looks at the viewer. Raising her right index finger to hammer home her conclusion, the Bohemian completes her prediction, as indicated by her gaze, already directed at the next customer: below the shepherdess with the neck ribbon, in fact, her companion leaning forward holds her right forearm raised in front of her, under her chin, ready to extend it in turn towards the Bohemian. The Bohemian woman is thus torn between a prediction that is coming to an end, signified by her hands, and another that is about to follow, announced by her gaze.

On the left, below, a shepherd was holding out a wreath of flowers with his left hand towards the young girl, who turned away to await her turn to face the Bohemian. At the same moment, a third shepherdess, busy weaving a long garland of flowers and seated in front of the shepherd, turns to her left, bringing her garland back to her to keep it from the appetites of the upraised sheep on the right, who covets it with his gaze. It's only by chance that she finds her head under the shepherd's outstretched wreath and, tauntingly, overhears a gesture that wasn't intended for her. The embarrassed shepherd tries to put on a brave face.

.Above the shepherdess with the garland, in front of a ruined stone factory, a caryatid column depicts an armless faun, perhaps the god Pan. In a tree just behind, reeds assembled into a flute and suspended from a branch await the wind to resonate35.

The complexity of this composition, bordering on illegibility, stems from the intertwining of the two scenes, the good fortune scene in the center right, the gallant coronation scene on the left. The Bohemian is not a character from the Pastorale, and her idealized world is not that of the bambochade: it's with a veritable weave that Boucher inlays the Caravaggio motif of good fortune into the unreal setting of Rococo libertinage. The composition's allegorical intent gives it unity: in the upper part of the tapestry, Pan contemplates his flute from his ruined temple, both close to him and definitively lost to him. This is the image of desire facing its object. In the same way, the shepherd believes he possesses the shepherdess with upraised arm, the shepherdess with upraised arm believes she will soon know her future, the sheep believes it will be possible for him to possess her. /// the flower garland. Everyone is chasing the imminent satisfaction of an illusory desire: the shepherdess with the garland's sardonic look confirms her companion's indifference and suggests that the young man's declaration will have little success; the gesture of her hands indicates that she is bringing back her garland, which will not be for the sheep. As for the shepherdess with the neck ribbon, doesn't she sketch a sort of disappointed withdrawal, which contrasts with her companion's feverishness, but at the same time foreshadows her future disappointment ?

In Leprince's composition, we find the same descending diagonal as in Boucher's, contrasting the figures in the scene at bottom left with the trees and sky at top right. However, the tree species have been adapted to the new country they are supposed to represent: on the right are three or four fir trees, on the left a birch, recognizable by its white trunk marked with black. On the other hand, instead of being set against a stone structure representing a ruined temple, the scene here has the Bohemians' cart and tent as its background and support. The shepherds and Boucher's gallant scene have disappeared. The sheep, this time on the left, are no longer pastoral sheep, but the Bohemians' own sheep: they go with the caravan. The temple has disappeared, and with it any reference to classical culture. Diderot describes the scene as follows:

...

" The scene is deep in a forest. Under a kind of tent formed by a large veil supported by tree branches, we see a large cradle or travelling bed mounted on wheels, and suitable for being dragged by horses. Further back, behind the rolling bed and horses, some of our sorcerers. Outside the tent, on the right, in front and on the ground, a horse collar, some sheep, a chicken cage. " (DPV XVI 305.)

Diderot identifies the persistence of the classic performance device : the " espèce de tente " delimits the restricted space36 of the stage. From " behind the rolling bed and horses ", from the darkness of the Bohemians' tent, a man turns his back while an old man observes the scene. The Diderot description simply juxtaposes this information. But the very order in which they are presented suggests the fundamental articulation of the scenic device : the old man's breaking-in gaze, from the vague space, towards the fortune-teller and her client, in the restricted space, clearly establishes an illuminated space of the public stage and an obscure, withdrawn, intimate space of the backstage area, the gaze being constituted by the transgressive passage from one to the other.

.The comparison of the two tapestries highlights the primary character for Leprince of the classical device of representation : Leprince does not start from reality and does not describe reality above all he practices the craft he has learned and combines the forms, the dispositions provided by his art and his culture as a painter the very exoticism of Russianism is an exoticism of convention, which moreover leads him to favor the representation of the most oriental types of the Russian empire, as we saw in Le Baptême russe. As for the Bohemian woman painted for Beauvais, is she a gypsy from Russia or a gypsy from Naples ? The importance of the notebook of drawings brought back from Russia has undoubtedly been overestimated: these drawings are no closer to a realistic representation of Russia than those executed later, on Leprince's return to France. The proof is in the /// difficult to date. As for the illustrations of Chappe d'Auteroche's Voyage en Sibérie, they represent scenes that Leprince never saw, and which he drew as novel illustrators compose their engravings, with the conventions and codes of the classical scene.

However, Leprince's trip to Russia is of decisive importance for art history, perhaps more for the fame it brought the artist than for the actual influence it exerted on his work. The idea of document emerges: Leprince wanted to get closer to this idea, and it's in this respect that his public appreciated him, even if the result is only a timid arrangement of the codes of rococo painting.

Faced with this idea, Diderot's attitude is ambiguous : he first refuses to take Russian mores into account for his analysis of the paintings, claiming ignorance ; then he castigates Leprince's predilection for beautiful costumes, as unworthy of the concerns of great painting. But at the same time, the digressions at the end of his articles on Leprince recast an imaginary, gallant Russian society, and conclude with the ancient simplicity of Russian costume. Diderot also creates his own russianism: the result is certainly not very Russian, but the essential thing is this reversal that organizes the text. Diderot practices humanist decentering, albeit within a closed, regulated space. The painter's exercise, like that of the philosopher, thus precedes the ethnographic enterprise.

Bibliography

Diderot's texts are cited in the edition of the complete works published by Hermann on the initiative of Herbert Dieckmann, Jacques Proust and Jean Varloot, known as the DPV edition, the Roman numeral indicating the volume.

Jules Hédou, " Notice sur le peintre-graveur Jean Le Prince, fils de Jean-Baptiste le Prince ", Précis Analytique des travaux de l'Académie des Sciences, Belles - Lettres et Arts de Rouen, 1878-1879, p. 500 ff

Jules Hédou, Jean Le Prince et son œuvre, Paris, 1879, repr. Amsterdam, 1970

Mary-Elizabeth Hellyer, Recherches sur Jean-Baptiste Le Prince (1734-1781), thèse de 3e cycle, Paris IV, dir. J. Thuillier, 1982 (unpublished)

Michel Mervaud, Chappe d'Auteroche, Voyage en Sibérie, 2 volumes, Oxford, VoltaireFoundation, 2004, p. XIII - XVI, 1-122

Madeleine Pinault Sørensen, " Le Prince et les dessinateurs et graveurs du Voyage en Sibérie " in Chappe d'Auteroche, Voyage en Sibérie, I, SVEC, Oxford, 2004, n° 3, p. 125-158, followed by a catalog raisonné of the plates.

Louis Réau, " L'Exotisme russe dans l'œuvre de Jean Baptiste Leprince ", Gazette des Beaux-Arts, t. I, 1921, p. 147-165

Perrin Stein, " Le Prince, Diderot et le débat sur la Russie au temps des Lumières ", translated from English by Jeanne Bouniort, Revue de l'art, n° 112, 1996-2, p.16-27

Exhibitions

Rouen, 2004 : Jean-Baptiste Le Prince, le Voyage en Russie, musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen, 2004. Cahier du cabinet des dessins n° 8,

Metz, 1988 : Jean-Baptiste Le Prince, Metz, Musée d'art et d'histoire, 1988. Catalog by M. Clermont Joly

Paris 1986-1987 : La France et la Russie au siècle des Lumières, Paris, Galeries nationales du Grand-Palais, 1986-1987. Catalog by A. Angremy, J.- P. Cuzin et alii

Philadelphia - Pittsburgh - New York, 1986 - 1987 : Drawings by Jean-Baptiste Le Prince for the Voyage en Sibérie, Philadelphia, Rosenbach Museum & Library, 1986-1987 ; Pittsburgh, The Frick Art Museum, 1987 New York, The Frick Collection, 1987. Catalog by Kimerly Rorschach with an essay by C. Jones Neuman

Notes

. ///The biographical information below is taken from La France et la Russie au Siècle des Lumières, catalog of the Grand Palais exhibition in 1986-1987, Ministère des affaires étrangères and Association française d'action /// artistique, 1986 ; supplemented by E. Bénézit, Dictionnaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs et graveurs, Gründ, 1999 and by M. Pinault-Sørensen's very precise article.

Lorraine was attached to the French crown at the peace of 1736, and this cession was the work of the Count of Belle-Isle, who had the confidence of Cardinal de Fleury. As a reward, the king gave him the government of Metz and the three bishoprics, which he retained for the rest of his life.

Madeleine Pinault believes, however, that the Prince never went beyond western Siberia. The continuation of the voyage has been wrongly inferred from the fact that Leprince illustrated " La descritpion du Kamtchatka " by M. Kracheninnikov, in the third volume of Chappe d'Auteroche's Voyage en Sibérie.

Jean Chappe d'Auteroche, Voyage en Sibérie fait par ordre du roi en 1761, contenant les mœurs, les usages des Russes et l'état actuel de cette puissance, la description géographique et le nivellement de la route de Paris à Tobolsk, l'histoire naturelle de la même route..., in Paris, by Debure père, 1768. Two volumes in three in-folio volumes and a large in-folio atlas. Paris, Bnf, Cartes et Plans, Ge DD 4796 (90-93). The book was republished the following year and translated into English in 1770.

There are over one hundred and sixty plates by him. These include, between 1764 and 1768 : Divers ajustements et usages de Russie (suite of ten etchings dedicated to Boucher), Habillement des Prêtres de Russie, les Strelitz, Habillements des femmes de Moscovie, Cris des marchands de Russie (the latter had two sequels).

According to P. Stein, Leprince would have literally translated the realistic and critical sketches brought back from Russia into more conventional rococo scenes when he switched to painting : " Drawings evoking sketchy living conditions and barbaric traditions, such as the rather critical-sounding illustrations in Voyage en Sibérie, are cleansed of all too distressing elements during the transposition into oil painting, and made to conform to the standards of the French plastic tradition as passed down through Boucher's studio. Hence, Le Prince's paintings never deviate much from the pictorial formulas of the rococo, despite the novelty of their subjects, nor is this what was expected of them. " (P. 18.)

This painting is now identified as the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen, inv. 818.1.22, formerly entitled Paysage aux environs de Tobolsk.

Let us also point out the six etching plates from 1765, the suite of which is entitled Diverses vues de Livonie and the four books of Principes du dessin dans le genre du paysage published by Demarteau after Leprince (M. Pinault, p.135).

For P. Stein, who analyzes Le Berceau russe from the Salon of 1765, now in the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, " the artist has combined attitudes, costumes and landscapes, presumably observed in Russia and carefully selected, with an already common symbolism of procreation and domestic harmony [...]. The Prince, adopting a resolutely unfaithful approach, isolates and recomposes memories of his Russian sojourn to conform them to a utopian vision of a primitive society in tune with the natural order, as described by /// Rousseau. The resulting image, with its delightful rococo palette and interlocking forms, bears only a distant relation to the realities of Russia at that time" (P. 24). Stein's in-depth article is absolutely convincing in terms of the pictorial analysis of the paintings and how they relate to one another, the seductive analysis of the ideological content that leads to this conclusion raises a number of objections : the rococo aesthetic of a Boucher and the nature evoked by Rousseau (and his illustrators) in La Nouvelle Héloïse and the Emile, which here seem to enter into synergy, are in fact absolutely opposed, to the point where we can define Rousseau's vision of nature and natural education as a frontal reaction to the artifices of the Regency pastorals, from which Boucher proceeds. How, then, could a Rococo painting convey a Rousseauist message? (Same contradiction in M. Pinault, p. 137.) Finally, why should the painter's most faithful approach, his first movement too, necessarily be realist ? Is it not, on the contrary, the craft learned from his master Boucher that comes first with Leprince, and betrays itself as early as the drawings for Chappe d'Auteroche (and all the more irrepressibly so as he was apparently not on the trip), the documentary value of " russerie " only gradually coming, after the fact, to disrupt a rococo aesthetic that in any case, as the 70s approach, is drawing to a close ? However, Madeleine Pinault's skepticism and dismissal of the article as a whole (p.135) make us smile: we fail to understand, for example, why Leprince's poor health would have prevented him from slipping into his canvases the sexual allusions on which the entire eighteenth century embroidered, and which P. Stein decodes with great certainty...

.

These head-on contradictions are due to the fact that both authors think of the question of the paintings' content in terms of illustration (did Leprince illustrate the Philosophes ?) and not representation (what did Leprince represent and how did he do it ?), that is, thematically and not semiologically.

Probable allusion to Chappe d'Auteroche's Voyage en Sibérie, in the illustration of which we saw that Leprince had participated. The Abbé's depiction of a miserable Russia under despotic rule was seen as a criticism of the reign of Catherine II, even though the Russia described was that of Elizabeth I and Peter III. The book was therefore castigated by the philosophers, whom the empress openly supported, even though the clumsy pamphlet with which Catherine anonymously replied to him under the title of Antidote (Princess Dachkov and Falconet were the authors, according to Lalande) did not meet with their approval either (letter from Diderot to Grimm, March 4, 1771). This affair could explain Diderot's a priori unfavorable attitude towards Leprince.

It might be interesting to relate this lost painting to Leprince's drawing for the first engraving of Voyage en Sibérie, executed by J. Ph. Le Bas and entitled Traîneaux de Russie pour voyager en hiver, although Diderot's description mentions a seigneur's post, a bridge and boats that are not to be found in the engraving. In any case, Leprince painted at least one Russian snowscape (M. Pinault, p. 132) !

This is the painting commented on by P. Stein, who spots the same concentric arrangement. See also our analysis in Utpictura18.

" The dominant Religion of Siberia, as well as of all Russia, is the Christian Religion of the [sic]Greek Rite. [...] The Greek Religion differs principally from the Christian Religion. /// Latin in the following Articles. The Greeks give the Baptism by immersion, & the Latins by aspersion : the latter consecrate with unleavened bread ; the former with leavened bread, & they administer the Sacrament of the Eucharist under both especes. " (Chappe d'Auteroche, Voyage en Sibérie, t. 1, " De la religion grecque ", 1768 ed., p. 128.) Chappe d'Auteroche refers in this chapter (p. 128, p. 139, p. 141) to Voltaire's Histoire de l'empire de Russie sous Pierre-le-Grand, which addresses the religious question in two chapters (I,2 and II,14). But Voltaire, who deals with religious history in its political dimension, makes no mention of these differences in customs.

Voltaire, Histoire de Russie, I, 2.

Although this early painting by Fragonard is more dependent on the aesthetics of a Carle Vanloo or a Jean-François de Troy, Fragonard had in common with Leprince having been a pupil of Boucher. It was in this explicit capacity that he was accepted in 1753 as a protégé of the Royal Academy of Painting. Leprince, only two years younger, arrived in Paris from Lorraine and became Boucher's pupil in the same years. See Fragonard, catalog by Pierre Rosenberg, RMN, 1987, p. 38 and n° 8, p. 52-54.

... and in the Coresus and Callirhoe the incense vessel, in the center of the canvas (absent from the description by Diderot, DPV XIV 257-261).

This is, for example, the scene of Lucile and Eraste in Le Dépit amoureux, a pathetic scene during which the two actors perform a domestic scene as an aside (Paradoxe sur le comédien, Colin, 1992, pp. 111-112), or one of La Chaussée's " most touching scenes ", which Gaussin uses to win back a scalded lover installed among the spectators in the balconies (p. 113-114). Similarly, Caillot, after playing Alexis in Sedaine's Le Déserteur, with " all the trances of an unhappy man ready to lose his mistress and his life ", approaches the Princess of Galitzine to court her as if nothing had happened, much to her scandal (p.156-157) finally, Mlle Arnoud, playing Télaïre in Rameau's Castor et Pollux, swoons " between the arms of Pillot-Pollux she is dying, or so I believe, and she stammers softly to him "Ah ! Pillot, how you stink !" " (p. 166).

" an unpleasant mixture of ochre and copper ", " all its yellow daub of which I have no idea " (DPV XVI 310) ; " But it colors badly ; its tones are bis, gingerbread and brick color " (DPV XVI 319).

This accusation is all the stranger given that the only surviving fragment of cardboard, La Diseuse de bonne aventure from the Musée de Picardie in Beauvais (inv. 66-2), is extremely brightly colored : the transposition to tapestry does indeed tend to soften contrasts and extinguish colors. Diderot's criticism is in fact aimed at something else.

DPV XIII 228 (Salon of 1761, Hallé's overdoor) ; DPV XIV 54-57 (Boucher) ; DPV XVI 62 (la dépravation des mœurs, préface du Salon de 1767) ; DPV XVI 123 (Salon de 1767, dessus-de-porte de Lagrenée). Oddly enough, Servandoni, who had made a specialty of painting overdoors, /// escapes the general anathema pronounced on gender (DPV XIV 124).

Inventory number 8408.

About Leprince's Autre Bonne Aventure, Diderot writes : " The flat figures resemble beautiful and rich images pasted on canvas " (DPV XVI 316). And facing the Concert, he exclaims : " why these faces so flat, so flat, so weak, so weak, that one hardly notices any relief. " (DPV XVI 317.) Flat is to be taken, of course, in both the geometric (depthless) and aesthetic (insipid, expressionless) senses.

Understand : that Leprince only wanted to paint, i.e. to which Leprince tried in vain to give expression.

Understand : according to Russian manners and customs, the manner of dress and clothing have a nobility...

Speaking of his engraved series of Russian costumes, Leprince wrote in Le Mercure de France, in October 1764 : " On trouvera dans une grande partie de ces ajustemens, des rapports singuliers avec ceux des plus anciens Peuples. The spirit of fashion, so pernicious to the Fine Arts, having not penetrated these climes, beautiful things have been preserved, far more beautiful and more natural than our ephemeral finery. " (quoted by M. Pinault, p. 142)

For Salons, see in particular DPV XIII 250-251 and XIV 396. Otherwise, see Daniel Webb, An Inquiry into the beauties of painting and into the merits of the most celebrated painters, ancient and modern, London, R. & J. Dodsley, 1760, whose French translation by Claude-François Bergier was printed in 1765.

To take up categories we use elsewhere, the brutality of the referent (russeness) is identified with the regenerative power of the symbolic principle (the grand manner, the ideal), so that in the end we never leave the symbolic institution (the conventions of the classical pictorial scene).

Only a fragment of this carton has been preserved, depicting the central scene where the young girl standing on the right holds out her hand to the Bohemian woman as a red-capped man looks on (Beauvais, Musée de Picardie, inv. 66-2). All other cartoons in this series are lost.

Similarly, Madeleine Pinault shows that Leprince, who according to her never went as far as Kamchatka, copied some of the costumes he drew and painted from other illustrated series that preceded him : Corneille Le Brun's Voyages par la Moscovie, et la Perse et aux Indes orientales, in Dutch in Amsterdam, Willem and David Goeree, 1711, then in French in Amsterdam, frères Wetstein, 1718 ; La Chine illustrée de plusieurs monuments tant sacrés que profanes by Father Athanase Kircher, two Latin editions in Amsterdam in 1667, ed. French, Amsterdam, Jean Jansson..., 1670 (2e part, chapter IV) finally the drawings executed by Fedor Vassiliev at the time of Peter the Great (circa 1719), or the portraits of Russian and Finnish peasants and burghers painted by Pietro Rotari and inserted in 1764 by the architect Jean-Baptiste-Michel Vallin de la Mothe in the woodwork of the portrait room at Petrodvorets.

See Diderot's almost glowing commentary, DPV XVI 574-576.

31 All the following paintings are oils on canvas designated under the title La Diseuse de bonne aventure : Caravaggio, 1598, Musée du Louvre ; Simon Vouet, 1618-1620, Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada ; Nicolas Régnier, 1625, Musée du Louvre Valentin de Boulogne, 1628, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Valenciennes ; Georges De La Tour, 1635-1638, New-York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art ; Jan Cossiers, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Valenciennes, mid-seventeenth century.

Despite the identical title, the scene depicted is not always the same. There's no robbery in Caravaggio's work, where the client is a young man but in Vouet's, Régnier's and eighteenth-century scenes, it's a young girl when there is robbery, it's sometimes the client who is robbed by a companion (De La Tour, Cossiers), sometimes he who steals the Bohemian through a companion (Vouet, Valentin), sometimes both (Régnier) !

At the Estampes de la Bibliothèque nationale de France, we can see a Diseuse de bonne aventure engraved by Michel Lasne which is a double portrait (a young man's head, his hand on which a coin is placed and a Bohemian face), another by Pierre Brébiette which camps the scene in a landscape, with a long verse poem as the caption.

Bambochades are small paintings or etchings depicting burlesque or country subjects. The name comes from a painter, Pieter van Laer (Harlem, 1592-5/1642) nicknamed the Bamboche (the little hunchback, from the Italian bamboccio), who excelled at reproducing popular, facetious scenes (Le Vendeur de petits pains, Rome, Gallerie nationale ; Paysage aux joueurs de Morra, Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts). Callot ranks first among authors of bambochades. We should also mention Téniers and Van Ostade, for whom Diderot repeatedly expresses his admiration, while at the same time professing the utmost contempt for bambochade. In the preface to the Salon de 1767, for example, he deplores the reduction of great subjects " to bambochade ; and to convince you of this, see Vérité, Vertu, Justice, Religion ajustées par La Grenée pour le boudoir d'un financier " (DPV XVI 62) ; in the same Salon, he criticizes Cochin's engravings " a low, ignoble aspect, a false air of bambochade " (DPV XVI 500).

Sébastien Bourdon, La Bonne Aventure, c. 1636-1638, copper painting, 48x39 cm, Florence, Uffizi Museum, inv. of 1890, no. 1206.

Perhaps there's an allusion here to the legend of Pan and Syrinx. Syrinx had transformed herself into a reed to escape Pan's advances. As Pan sighed at the reeds, he thought he heard them moaning. He then had the idea of joining reeds of unequal length with wax to make Pan's first flute, called syrinx in Greek (Ovid, Metamorphoses, I 705-712).

The tent, the curtain conventionally designate the restricted space in the classical stage, for reasons of theological origin. See, for example, S. Lojkine, " Une sémiologie du décalage : Loth à la scène ", La Scène. Littérature et arts visuels, dir. M.Th. Mathet, L'Harmattan, 2001, p. 15-17.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « La Russie de Leprince vue par Diderot », Slavica Occitania, n°19, Toulouse, 2004, p. 13-38.

Diderot

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Diderot

Les Salons

L'institution des Salons

Peindre la scène : Diderot au Salon (année 2022)

Les Salons de Diderot, de l’ekphrasis au journal

Décrire l’image : Genèse de la critique d’art dans les Salons de Diderot

Le problème de la description dans les Salons de Diderot

La Russie de Leprince vue par Diderot

La jambe d’Hersé

De la figure à l’image

Les Essais sur la peinture

Atteinte et révolte : l'Antre de Platon

Les Salons de Diderot, ou la rhétorique détournée

Le technique contre l’idéal

Le prédicateur et le cadavre

Le commerce de la peinture dans les Salons de Diderot

Le modèle contre l'allégorie

Diderot, le goût de l’art

Peindre en philosophe

« Dans le moment qui précède l'explosion… »

Le goût de Diderot : une expérience du seuil

L'Œil révolté - La relation esthétique

S'agit-il d'une scène ? La Chaste Suzanne de Vanloo

Quand Diderot fait l'histoire d'une scène de genre

Diderot philosophe

Diderot, les premières années

Diderot, une pensée par l’image

Beauté aveugle et monstruosité sensible

La Lettre sur les sourds aux origines de la pensée

L’Encyclopédie, édition et subversion

Le décentrement matérialiste du champ des connaissances dans l’Encyclopédie

Le matérialisme biologique du Rêve de D'Alembert

Matérialisme et modélisation scientifique dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Incompréhensible et brutalité dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Discours du maître, image du bouffon, dispositif du dialogue

Du détachement à la révolte

Imagination chimique et poétique de l’après-texte

« Et l'auteur anonyme n'est pas un lâche… »

Histoire, procédure, vicissitude

Le temps comme refus de la refiguration

Sauver l'événement : Diderot, Ricœur, Derrida

Théâtre, roman, contes

La scène au salon : Le Fils naturel

Dispositif du Paradoxe

Dépréciation de la décoration : De la Poésie dramatique (1758)

Le Fils naturel, de la tragédie de l’inceste à l’imaginaire du continu

Parole, jouissance, révolte

La scène absente

Suzanne refuse de prononcer ses vœux

Gessner avec Diderot : les trois similitudes