There's a double paradox of Casanovian seduction. To seduce, you have to show off ; but in seduction, it's the other that matters, it's the other that you have to interest in yourself. This implies a withdrawal from oneself for the benefit of the other. Seduction is therefore both writing about the self and suppressing the self; it constitutes the self as a receptacle for the spectacle of the other, which it welcomes, flatters, develops and grows.

.And this seduction is a seduction of possibilities. From an absolutely chance encounter, a simple combination of circumstances,it can,it could develop a story, an intrigue, a conquest : the scene that offers itself, the encounter that chance provides, the sight that excites desire could develop its potentialities. The precariousness of the possible is what seduces, the randomness is what makes seduction. But the work of seduction, on the other hand, requires the implementation of a strategy, the planning of actions, the structuring of conduct. Seduction is both the indetermination of possibilities and the determination of an action, it is the charm of the vague and its reduction. Seduction is a disengagement and a hold, a disengagement from the conduct of events and a hold on them.

The first paradox defines seduction's relationship to the ego the second paradox defines its relationship to the conduct of events. At this double level of self and event, the relationship is active and passive, the seducer proposes and welcomes, intervenes and undergoes, or more exactly enjoys an indistinction of the two positions. This ambivalent relationship comes under what is known in Greek grammar as the middle way, and defines chrèsis, usage. What is usage? Use consists in taking care of oneself by establishing a relationship with others, a relationship of use to things and people.

What is use in the History of my life1 ?

First, there is the use of language : Casanova receives French and, in French, establishes a forcing, introduces a declension, a deviance where jouissance is played out: the use of language boils down to a use of the body, the body that discharges, and the vit that puts itself behind rather than in front (scene at Mme Préodot's, p. 793-795).

Then there are usages, which define a usage of the world : Casanova arriving in Paris discovers usages, coffee, tobacco, theater, houses of pleasure. Back in Venice, he took advantage of customs: casinos and their parties, gambling, carnival and its masks, the parlors of convents. His seduction strategies were based on making use of and appropriating customs. Casanova installs himself in uses to turn them to enjoyment : here we are back to the use of bodies, which eroticizes and subjectifies uses, inflecting the community of uses into use for oneself, into the middle way of use.

Then comes the use of the other. By relying on language, and settling into the world, Casanova enters into a relationship with others. We're not talking here primarily about the seduction of women, but rather the male companions he establishes throughout his narrative, in a relationship of mastery that is always ambiguous : his protectors, Senator Malipiero (p. 79), then M. de Bragadin /// (p. 478) ; his companions on the road and in debauchery, Father Steffano, the Franciscan monk who accompanies him on Chiozza's journey to Rome (p. 187) Patu in Paris, who takes him to the Hôtel du Roule, one of Paris's most famous brothels, then to the Morfi (p. 855), where he meets " la petite Hélène " ; P. C. (Pier Antonio Capretta), who introduces him to her sister C. C. (p. 937) and solicits him for all kinds of shady business, right up to the Vicenza trap (p. 986). Casanova uses these relationships, but he is also used by them the use of the other is a perpetual negotiation where the position of master and dupe can be reversed at any moment, and where the horizon, the stakes, avowed or concealed, are women's bodies. The use of the body constitutes a beyond of mastery, which itself always remains uncertain and problematic.

I. Words, world, mastery : the three uses

But first we need to establish this relation of usage that defines usage as the middle path of chrèsis. Let's start from the beginning of chapter X of volume III (p. 712), which is a banquet, the very banquet of menippean satire, whose loose table talk feeds a narrative-fiction navigating the randomness of conversation.

Let's pause for a moment to consider the very special nature of this supper. In the 1st version of the text, Casanova explains that on the road that takes him and Balletti to Paris, after they have slept in Fontainebleau, their last stop, Balletti recognizes his mother in a carriage that comes to meet them :

" We slept in Fontainebleau, and an hour before we reached Paris, we saw a Berline coming from there. There's my mother," says Balletti, "stop, stop. We got out, and after the usual greetings between mother and son, he introduced me, and this mother, the famous actress Silvia, said to me: "I hope, Sir, that my son's friend will dine with us this evening. Saying this, she climbed back into her carriage with her son and nine-year-old daughter. I get back into the gondola2. " (p. 710)

Balletti has therefore notified his mother of his arrival in Paris. She is coming to meet him and has prepared a grand family supper for his welcome, to which Casanova is also invited. The entry structure of chapter X thus repeats that of chapter IX : Casanova inserts himself into an event that is not planned for him, does not revolve around him, could very well take place without him.

Of this event though he makes his " first time ", his first supper in Paris. At the supper, Flaminia emphasizes that this is " the first day of myarrival " (p. 714, first version), " the first day of your arrival in Paris " (p. 715, 2e version). After dinner, he says he's " very happy with this first evening " (p. 718, 719). The next morning, he asks his new valet L'Esprit to change a louis for him: he's just arrived, he hasn't spent anything yet, he has no change. This first supper was indeed the supper of the first evening in Paris.

The proper use of language

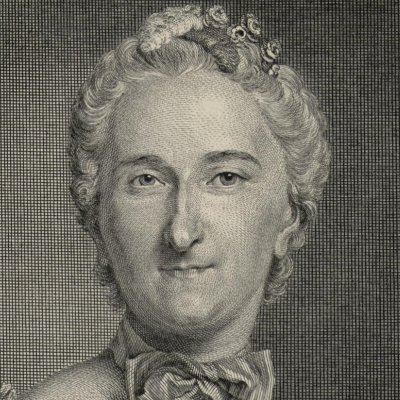

The supper to which Casanova was invited was therefore organized by Silvia, the mother of Antonio Stefano Balletti, with whom Casanova made the journey from Turin to Paris. The Balletti family, the heart of the Comédie-Italienne in Paris, is there in full. The queen of /// dinner is Elena Riccoboni3, known as Flaminia (in Italian comedy, Flaminia is the name of the first lover). Flaminia is the sister of Antonio Stefano Balletti's father. Born in1686, she played the fairy in one of Marivaux's early comedies, Arlequin poli par l'amour. Flaminia was 64 in 1750, a woman of letters " because of some translations ", she turned the heads of three Italian scholars and poets during their stay in Paris, Maffei, Conti and Martelli. No doubt thinking of introducing her to his august aunt in the most advantageous way, Balletti fils introduces his friend Casanova as a writer :

" When Balletti her nephew, introducing me to this woman, dared to tell her that I was also a young member of the Republic of Letters, of which truth be told, she asked me, smiling, what works I had given to the public ? I replied that her nephew had been bantering " (p. 713-715)

Casanova feels ridiculous : Balletti has him play an impostor, which he immediately denounces. In Flaminia's ironic, scornful smile, he perceives that he doesn't look like the intellectual his comrade has announced. So he takes off the air he doesn't have, but at the same time intends to prove that he is indeed this " young member of the Republic of Letters " whom " I didn't really look like ". The whole scene is based on this division of self from self. Casanova intends to prove to Flaminia that he belongs to the same world as she does to this end, he recites two verses by the abbé Conti, his former lover, whom he happens to have frequented in Padua :

" ... I quoted two of his verses in which happened to contain the word scevra. This word, which is a syncopation of scevera means separated. Flamminia told me, affecting an air of kindness, that I should say sceura, not scevra because the letter u was vowel. I replied, giving her one of those apologetic curtseys, that she was mistaken.

-You're the one who's wrong. Don't be angry that you learned to pronounce an Italian word the first day you arrived in Paris.

- I'm not the only one. - I wouldn't be upset, madame, but on this occasion I must prefer Ariosto's opinion to yours.

-From Ariosto ?

- Yes madame ; he gives scevra to rhyme with persevra ; so you see that the letter u there is consonant. " (p. 715)

And indeed, in stanza 26 of Canto V of Roland furieux, which Casanova knew almost by heart, we read :

" Così dice egli : io, che divisa e scevra,

E lungi era da me, non posi mente,

Che questo, in che pregando egli persevra

Era una fraude pur troppo evidente... "

This is what he says to me. I, who was divided, separated,

far from me, I did not realize

that what he prayed for and persevered in

was a treachery, alas ! too obvious...

Polinesse, jealous of Ariodant, Guinevere's lover, persuades his servant Dalinde that he is in love with her and that she must take her mistress's clothes to welcome him to her chamber. He intends to prove to Ariodant that Guinevere gives him nocturnal rendezvous: Ariodant, posted under Guinevere's window, believes he sees Guinevere in the arms of Polinesse, whereas /// the traitor embraces Dalinde. Dalinde, who understands only too late what a tragic mistake she has been the accomplice of, tells how Polinesse seduced her. Dalinde, divided from herself, separated from herself, scevra, lets herself be deceived by Polinesse, who insists that she disguise herself, and insists, and perseveres, persevra.

Casanova quoting Conti is in fact quoting theRoland furious : he takes refuge in the word of Dalinde, the fooled servant, scevra, separated from herself, and in this withdrawal he affirms his mastery of the language of Ariosto, the genius of Italian poetry. Casanova withdraws and exhibits himself, he loses and he regains the use of his language, he separates and he seizes the republic of letters.

Silvia, l'usage du monde

After the altercation with Flaminia comes the portrait of Silvia, who is in some ways the antithesis of her sister-in-law. Flaminia represents the worldliness of the world, which separates, divides, excludes she is what the narrator faces, makes a poor figure, makes a tableau and, despite everything, operates the injection of the signifier, through the word scevra, which says the exclusion and operates the inclusive reversal.

Faced with the mundanity of the world, whose use is the use of words, Silvia figures the use of the world, her figure is seen as the image of good use. Casanova paints a portrait of her according to the rhetorical rules of portraiture, first physical, then moral. The physical portrait is an anti-portrait :

" At this supper, Silvia, whose fame was going to the skies, attracted my main attention. I found her above all that was said of her. Her age was fifty, her person appeared well-built, her stature was elegant, her air noble as were her manners; in conversation she was easy-going, affable, laughing, fine in her remarks, obliging towards everyone, full of wit without giving any sign of pretension. Her face was an enigma she was interesting she appealed to everyone and despite this, on examination, she could not be found beautiful but no one ever dared to decide she was ugly. It could only be said to get rid of her that she was neither beautiful nor ugly, because a character had to jump out at you. So what was she? Beautiful. But by laws, and proportions unknown only to those who felt compelled by an occult force to love her, had to study her to learn, and to come to recognize her for beautiful. " (p. 715-717)

Silvia first impresses and disconcerts : there is no circuit there into which the narrator, arriving, could fit. Silvia is above it all. Casanova doesn't describe any physical features, eye or hair color, height or shortness of stature, singularity of dress, hairstyle or ornament. What strikes him, on the contrary, is precisely the generality of his superiority the world is that air there to have the use of the world, is to use it as Silvia uses it.

So what Casanova sees doesn't give rise to a description as such, but rather to a learning experience. Casanova doesn't look at her, he studies her. Silvia's image is an apprenticeship in the world. First comes her air (" her person..., her height..., her air... ") ; then her conversation (" in conversation she was easy, affable, laughing... ") finally comes the figure, which must synthesize the whole and allow the portrait to be characterized.

.Or the figure is an enigma : it's neither beautiful nor ugly we must appreciate it as beautiful in the end, but it's not /// not what comes first. There is always the disconcerting impression of something superior, something beyond the ordinary categories of judgment. One cannot characterize Silvia, because characterization proceeds from the use of the world, and Silvia is, embodies this use. It is from Silvia that the young Venetian disembarking in Paris learns to characterize, and first to calibrate the beautiful from Silvia herself, who can therefore only be said to be beautiful at a later stage, once the paradigmatic enigma of her figure has been posed.

This portrait is a bravura piece. Silvia was Marivaux's actress, as Casanova reminds us a few lines later, in a strange way: " I saw her, two years before her death, play the role of Marianne in the little play by Marivaux that is called Marianne. " (p. 719) No play by Marivaux is entitled Marianne. The Leborgne-Igalens edition suggests that it might be L'Épreuve, a play first performed in 1740 at the Hôtel de Bourgogne, where Silvia played under the name Marianne the lead role, replaced by Angélique in the version of the play printed in Paris by Mérigot the same year.L'Épreuve was performed again in 1744, in 1747 at Fontainebleau, in 1749 again at the Hôtel de Bourgogne, in Brussels in 1754. Silvia died in 1758, so it's possible that she acted in an undocumented performance ofL'Épreuve in 1757, and that Casanova, who was then thinking of marrying his daughter Manon, attended : but she would then have played as Angélique and not as Marianne. It's far more likely here that Casanova confuses, and thus unwittingly reveals, a literary borrowing. The Marianne he's thinking of here would be La Vie de Marianne. Silvia's well-written portrait could well be inspired by that of Mme de Miran, in Part IV of Marivaux's novel :

" My benefactress, whom I haven't named yet, was called Madame de Miran, she could have been fifty. Although she was a beautiful woman, there was something so good and reasonable about her physiognomy, that it must have detracted from her charms, and prevented them from being as piquant as they should have been. When you look so good, you seem less beautiful an air of frankness and goodness so dominant is completely contrary to coquetry it only makes you think of a woman's good character, not her graces ; it makes the beautiful person more estimable, but her face more indifferent so that one is more content to be with her than to look at her4. "

It's the same age of fifty and above all the same unclassifiable beauty. Mme de Miran's kindness, her frankness that makes one " happy to be with her ", designate her as " to be with " rather than " to be ", as access to, or embodiment of, the use of the world rather than as the exclusive distinction of a figure in the world (" her more indifferent face... "). We don't see Mme de Miran ; we are welcomed into her network of sociability.

" And so, I think, as one had been with Madame de Miran ; one did not take heed that she was a beautiful woman, but only the best woman in the world. Also, I was told, she had hardly made any lovers, but many friends, and even girlfriends ; which I have no trouble believing, given the innocence of intention one saw in her, given that simple, consoling and peaceful countenance which must have reassured the self-esteem of her companions, and made her look more like a confidante than a rival. " (p. 168)

Silvia, like Mme de Miran, according to Casanova, had no lovers : " Her morals were pure. She wanted to have friends never lovers. " Friend, confidante, this fifty-something ideal portrait doesn't compare or rival her. She is " the best woman in the world " which is both a superlative and an elegant way of excluding the register of desire. This friendship with an exceptional woman denotes equality in the upper sphere of the world. The use of the world is the use of a being-with superlative.

What is the function of Silvia's portrait in the economy of a text like the Histoire de ma vie, in the autobiographical project it sets in motion ? The evocation of Flaminia that opened the chapter implemented, through the misuse of the word scevra, the injection of the signifier by which Casanova came to insert himself into the world described. But Silvia's portrait, built as an antithesis to Flaminia, offers no foothold for the insertion of the autobiographical subject. There is no scene with Silvia. This rhetorical portrait, which explicitly presents itself as a funeral oration (" Excuse reader, if I made Silvia's funeral oration ten years before her death... ") seems to constitute an autonomous, and therefore apparently gratuitous, textual cell.

It makes sense only by construction, precisely as Flaminia's antithesis. The use of words writes life, is the key that makes possible the injection of the signifier the use of the world writes death : it is the ideal reverse of desire and, through the image it returns, that it interposes in the text, it establishes the ideal of a perfect sociability where the play of differences and the tension of power relations would not be exercised. L'usage du monde reveals the death drive that underlies the writing of life.

Master and Jack

Still by antithesis, Silvia's funeral oration is followed by the episode of the recruitment of a valet, where, a contrario to the perfect equality in which Silvia held her friends, the harsh difference of master and valet, of the great and the small, of the one with a name and the one without is established:

" I see an alert ; but very small in stature enter.

- You're too small, I tell him. - My size, my prince, will make you sure I won't wear your clothes to good fortune.

- Your name? - Whatever you like. - What's your name? I'm asking you what your name is. - I have no name. Every master I serve gives me one, and I've had at least fifty in my life. I'll call myself by the name you give me.

- But you must have a name of your own that of your family.

- Family? I've never had a family. I had a name as a child ; but in the twenty years I've been serving I've forgotten it.

- So I'll call you the Spirit. - You do me great honor. - Fetch me the change for this louis.

- Here it is. - I see you're rich. - At your service. - I'll give you thirty cents a day. I won't dress you. You'll go to bed at your place at eleven, and you'll be at my orders every morning at seven. (p. 719-721)

A drille is, according to Trévoux's dictionary, a " nasty soldier " and " ne dit que par mépris et par raillerie ". However, the term is sometimes taken in good part, in popular language : " Le peuple appelle drille un jeune soldat éveillé et /// bold." This is the equivalent of Casanova's " alerte ". The dictionary then hints at an etymology : " This word is old Gaulish, and means a haillon, a garment that comes off in tatters, such as wicked soldiers ordinarily wear. " And indeed, the man who appears before Casanova immediately alludes to his clothes : his are his own, he'll never wear his master's, for practical reasons of size. Next comes a competing etymology : " from ὅλος we made solus, solidus, solidatus, soldat, soudar, soudrille, drille. " Not only is the link between drille and soldat thus justified by etymology, but from soldat we move on to solidus, the Byzantine gold ducat. And it's a louis d'or that Casanova asks his new valet to coin at the end of their conversation. In other words, the whole interview is a metaleptic deployment from the signifier : an alert drille, his bad soldier's garb, the solidus that gives him his name, his pay.

The drille's introduction is surprising : to Casanova who reproaches him for his size, the valet in no way responds by seeking to justify the advantages of his smallness smaller, he will be neither more agile, nor more discreet, nor less cumbersome, nor less expensive to feed. What the valet emphasizes is that he won't be able to borrow his master's clothes to seduce women. So he can't play his master's game, usurping his function. The risk of identity substitution is nil.

And it's on the identity of the valet that the whole interview hinges : not only can he not take on that of his master, but he claims no identity of his own, he claims no name. He is thus the opposite of the one who, since Plautus, has constituted the archetypal valet, the Amphitryon's doppelganger. In Molière's version, aptly performed in Paris in 1750 at the Comédie française, Sosie confronted by Mercury, who pretends to be Sosie in his place and rains down canings, painfully exclaims :

" Who throws you, tell me in this fantasy ?

What will become of you to take away my name ?

And can you do at last, when you're a demon,

That I'm not me? Let me not be Sosie5 ?

Sosie has nothing, he's nothing socially, he can't claim anything. But at least he has a name. His name is also the means by which he gives Mercure hold of him: through his name, Mercure holds him. He takes possession of him because he takes possession of his name.

This guides us in understanding what's at stake in Casanova's exchange with the little dodo : to ask him for his name is to solicit a use. " Your name ? " amounts to " How shall I use it with you ? " Polite solicitation of a relationship, ethical concern for otherness : the other shies away, won't offer a grip, won't give his name.

The valet offers a service, but refuses a use. He gives himself for hire, but evades the seduction of conversation. A certain exchange is possible and another is not : he won't exchange his habit, but he can change his name he won't deliver his name, but he has the change of money for a louis d'or. The custom of a master with his valet is expressed here, in this sharing of licit and illicit exchange. What the valet proposes to his master is the use of his body, and this is why the impossibility of exchanging clothes is a primary condition: the valet's body cannot escape, regain its autonomy, compete in the master's world. The conversation begins with the valet's size: it's his body we're talking about. It concludes with the allegiance of a " all at your service " : this /// what counts is not that the valet is rich, that he has money what counts, what is here the object of the contract, is the valet's body, it is that he be all at Casanova's service.

A division of use is thus made here, which defines the relationship between master and valet : the valet refuses the use proposed to him by Casanova, which is what I've called the use of the world, based on exchange and seduction. He offers another use, the use of the body, which Casanova defines as different from the use of the world. He thus reminds us that the first use, the one Aristotle posits at the beginning of Politics, is the use of the slave's body, ἡ τοῦ σώματος χρῆσις (1254b 18). This usage defines the despotic relationship, i.e. the relationship between master and slave, the one at play at the beginning of Plautus' Amphitryon and which Molière translates as the relationship of the valet to his master. In Aristotle, the despotic relationship establishes a norm of the relationship, from which, by difference, to define the other two relationships that constitute the family, the conjugal relationship and the parental relationship6. In the context of L'Histoire de ma vie, a use of the body is posited against a use of the world, with the use of words bridging the one to the other. The use of bodies constitutes the inconceivable horizon of the Histoire de ma vie : this is what Casanova stages in this dialogue he doesn't understand what the valet is saying to him, or more exactly he formulates its original difference from the use of the world in which he sets up his writing. He formulates that use of the body and use of the world do not overlap.

.Of course, in the context of libertine seduction, the use of the body also takes on a completely different meaning : but it is somehow veiled, covered over by the discourse, the strategy of seduction. The episode of the hired servant sent to him by the demoiselle Quinson offers a staging at its simplest, a foreshortened, naked, use of the body, detached from the erotic game with which Casanova almost always associates it.

.Requested to choose a name for him, Casanova names his valet the Spirit. What kind of spirit is this? It's not the spirit of the valet, who has no name and surrenders his body to the use of his master, for whom everywhere he will be in representation. The valet's name is merely the name his master gives him; he is the master's representation, he participates in that representation. Casanova is thus represented as the master of the Spirit, as the one who, through his spirit, has the use of words. His entire first stay in Paris will have the function, in the economy of the Histoire de ma vie, of attesting to this mastery.

The name of the Spirit, which refers to the use of words, assigns a name to the one who refuses to say his name. L'Esprit is the valet's service name, by which he can be used ; but it is also Casanova's man's name of representation, by which he will give a certain image of himself in the world. Esprit, as a name, thus links the use of the body to the use of the world it organizes their imperfect superposition.

II. Spirit and companionship

Mind is the point of contact of usages : spirit sanctions the correct use of words, it is the effect of correct usage spirit manifests the worldliness of the world, it signifies on the part of the one who makes use of it that he has the use of the world, that he is aware of the usages, that he also knows and masters the margins that one can invest to free oneself from the world without derogating from it ; the spirit, last but not least, spares the use of the other, in a relationship of reciprocal seduction, of mastery conquered and abandoned, which defines Casanovian companionship.

The chance encounter

Casanova's companion in Paris is not Balletti. He is not the one that the structure of the story ordered : it is with Balletti that Casanova goes up to Paris, it is through Balletti /// that he makes the acquaintance of Silvia, of the troupe of Italian comedians, of the world of entertainment. Balletti generously and scrupulously fulfills his duties of hospitality : " Balletti came to see me to beg me for dinner, and supper during the whole time of my stay in Paris. " (p.7217)

But here the chance meeting comes into play. Casanova asks Balletti to take him to one of the most famous public places in Paris at the time, and the most fashionable too it's the garden of the Palais Royal, which, opposite the Louvre, attracts elegant strollers, regulars at its cafés, vendors of all sorts of licit and illicit pamphlets and an interloped population of more or less priced women... Balletti leaves Casanova alone at the Palais Royal, seated at a café. An abbot, perhaps a matchmaker in an abbot's habit, strikes up a conversation with him (p. 723). Casanova is wary and evasive. A robin stops in front of them. Robin : the term is pejorative, a man of the cloth, a lawyer, but a little ridiculous in his dress, or infatuated. Casanova remains on his guard, this is not the beautiful, great world. The man whose name he doesn't immediately give, however, becomes his inseparable Parisian companion. It was Claude-Pierre Patu (p.729), son of a paymaster and nephew of a notary, a successful young Parisian bourgeois who became a lawyer at the Parlement de Paris. Patu was born in 1729, aged 21. He was just beginning his career in letters and died prematurely in 1757.

Usage and misuse

Patu is a bit shady, and Patu is terribly seductive, as was Father Steffano in Chiozza, Ismaïl in Constantinople, as will be P. C. in Venice : Casanovian companionship is a use and misuse :

" He [= the abbot] meets a robin ; he embraces him, and he introduces him to me as a docte in Italian literature : I speak Italian to him, and he answers me well, and with wit ; but with phrases that excite me to laugh, for he spoke precisely the language of Boccaccio. I tell him that although the language of this ancient was perfect, it becomes ridiculous in the mouth of a modern : you would also laugh I tell him if I spoke to you in the style of Montagne8. He liked my remark, and in less than a quarter of an hour, recognizing the same tastes, we became friends, and promised each other reciprocal visits. " (p. 723)

The starting point is a misuse of language. Patu speaks the Italian of books, the language of Boccaccio, the Florentine short-story writer who in the 14th century helped establish Tuscan as the classical language of Italy. But the Tuscan of the 14th century is no longer the Tuscan of the 18th century, a language which itself is not the Venetian of Casanova. Patu, met by chance, takes the place of Balletti, who structurally should have been Casanova's cicerone in Paris9 ; and Patu speaks the bookish structure of the language, instead of its contemporary usage. But Patu is witty, making Casanova laugh: is he witty despite the awkwardness of an inadequate language, or is it the very impropriety of his use of language that makes what he says witty? Spirit lies at the edge of use and misuse, and it is the use of language that establishes the connection and other uses : Casanova and Patu promise each other reciprocal visits, a bond of sociability is established, and with it a certain use of the world.

Sociability rests on the spirit, which establishes the equality from which a use of the world becomes possible. But the spirit is both use and misuse, according to the same play of edges and linking principle we saw at work with affabulation as the matrix of Casanovian writing, between fact and fiction. Casanova is perfectly aware of this ambivalence of the mind, for which he provides a sort of formula through Patu :

" You are at present in the only country in the world, where wit is the master of making fortune either whether it shows itself by giving truth, and for that reason the one who welcomes it is wit, or whether by imposing it gives falsehood, and in that case the one who rewards it is foolishness. It is characteristic in the nation ; and what is astonishing is that it is the daughter of wit, so that, it is not a paradox, the French nation would be wiser, if it had less wit. " (p. 72510)

The play of inversions in this definition of the French spirit is deliberately dizzying. L'esprit couples with sottise and reverses itself into it : this reversal defines the edge of use and misuse. The word wit means both truth and falsity truth is not a criterion of wit (which aims at enjoyment, the pleasure of a good word, not truth). " Ce n'est pas un paradoxe " in fact introduces a paradox : " la nation française serait plus sage (c'est-à-dire a priori qu'elle aurait plus d'esprit), si elle avait moins d'esprit. " Aspiring immoderately to the enjoyment of the mot d'esprit, the world indiscriminately consumes wit to say the true and wit to say the false, so that the silliness of gossip, of fake news, circulates as well as the wisdom of a subversive arrow and a hard-to-say truth whose witty formulation will have bypassed censorship, propriety and prohibition.

III. Uses of the body

L'Hôtel du Roule

There is, however, a use for this misuse. Casanova's companionship with Patu unfolds essentially around two episodes, which are the night spent at the Hôtel du Roule (p. 767) and the courtship of Morfi and her little sister Hélène (chap. 13, p. 855). The narrative is scattered with all sorts of other anecdotes linked to the use of the world but these are the two episodes that engage, nakedly, the use of the body, starting with this companionship, and reveal its troubled and disquieting substratum. Elsewhere, the use of bodies is always veiled, or mediated by the use of words. Here, Casanova gives us direct access.

Casanova arrives at the Hôtel du Roule in the same way he met Patu : by hijacking the narrative structure initially planned. He has befriended Coraline, one of the actresses of the Italian actors : this liaison is logical, deduced from the way he arrived in Paris and was welcomed by Silvia Balletti. Coraline is from the Veronese family : the father had played Pantalon since 174411, the eldest daughter called herself Coraline, her younger sister - Mlle Camille12 their brother, more episodic on the stage, played the Doctor in Le Double mariage d'Arlequin (1754). The Veronese family is the other major Italian family along with the Balletti.

Casanova aspires to be the lover of Coraline's heart, whose protector /// is the Prince of Monaco13. Coraline introduces him to the prince; he could almost become her sigisbe14. But the prince makes it clear that he is only a " guerluchon15 " by taking him to a lecherous old duchess who tries to rape him (p.763) ; as for Coraline, after promising him a fine game at La Garenne16, where the Prince of Monaco has a house, she " plants " Casanova en route : their carriage does indeed cross paths with that of the Chevalier de Wirtemberg, whom Coraline unhesitatingly prefers to her commoner, penniless companion. An ulcerated Casanova goes to see Patu, who " told me that the thing was not new, that everything was in order " the custom has been respected, Coraline could not have acted otherwise than she did. Did she, in fact, act, or was she subjected to the custom that corresponds to her condition as an actress ?

But above all, Casanova's companionship with Patu is established on the basis of the narrator's pitiful retreat to the margins of adventure and event from Coraline, he's not the priority with the Prince of Monaco, impossible to woo at the Duchess de Rufec's, the urgency was to get out en route to La Garenne, he was planted. The Hôtel du Roule episode is triggered by these failures, these successive exclusions, which he comes to repair : " When [Patu] saw that everything he was saying to me to calm me down was useless, he proposed that I go to dinner with him at the Hôtel du Roule. " The Hôtel du Roule is a consolation, a supplement, a pis aller the story will make it one of the most significant events of Casanova's first stay in Paris. It is at the Hotel du Roule that Casanova reveals himself in his stature and figure as a libertine : it is the most impromptu, least deliberate, most coincidental event, if you will, that takes place during the stay as a characteristic event in Casanova's personality.

.The Hôtel du Roule is characterized first and foremost by its " police ", that is, by the customs established there by its landlady, Madame Pâris :

" The police of her house were very wise : all pleasures were taxed at a fixed price, and not expensive. One paid six francs for lunch with a girl, twelve for dinner, one louis17 to sleep there. At last, it was a well-appointed home that people in Paris were talking about with admiration. I couldn't wait to get there, and I thought the game might be better than the one I would have made at the garenne. " (p. 767)

In 1750, Rochon de Chabanne and Moufle d'Angerville published Les Cannevas de la Pâris, ou Mémoires pour servir à l'hôtel du Roulle, à la porte de Chaillot18. The final chapter, entitled " Projet d'embellissement " (t. 2, p. 159), concludes with a " Ferme générale. Tarif " in which we find the three categories of tariffed pleasures Casanova alludes to, under more explicit headings : " Passades " corresponds to lunch (a simple pass), " Dîners et soupers " to dinner (the prostitute is hired out for the day), and " Couchers et promenades " to bedtime (one spends the night). Pâris's pseudo-memoire then refines, distinguishing three price classes for each category, with Casanova's prices corresponding to the 2nde class. But these prices are part of an " embellishment project ", they are an imaginary extrapolation : the pseudo-memoire proposes that they be collected by a " general farmer " who will /// will then pay the Pâris an annual annuity of 10,000 livres. In Casanova's account, he and Patu deal directly with the Pâris...

The fixed tariff, regulates the use of bodies. Casanova admires its simplicity, modesty, efficiency : the house is " well put together ", what beautiful organizations !

However, all the rules of custom will be transgressed : Patu and Casanova each begin by " rendering his duty " to his each, according to custom. Observe here the interplay of the middle path of chrèsis. By sleeping with the prostitutes they've chosen, they are certainly acting, but they're doing so by conforming to the custom of the brothel, submitting to its law. The party, the pass, is both an action and a submission. Through the passe, Casanova re-establishes his virility, scorned by Coraline ; but he only re-establishes himself by initiating himself into a usage.

The use of bodies then necessarily overflows into misuse, into the disorder of libertinism, into the overflow of the law : this derangement must not delude us, it's part of the use of this kind of place, it's what makes the fortune of the Pâris ! Patu and Casanova swap partners, promising the owner a new royalty. But Patu's organ no longer responds to demand, it has become impotent (p. 769) !

" Patu says that these pleasures measured by the hour were becoming drudgery : he proposes that I have supper, and spend the night there, and I'm willing. We go and tell the abbess of our plans, and she recognizes us for our wit. We tell her we want to go and choose again, and she leads us back into the room, where by the light of four candles I see a tall girl sulking. I approach her, find her a beauty I'm surprised she escaped me the first time ; but I console myself, thinking that I'll have her for twelve hours and all at my command. " (p. 769)

The use of bodies is measured by the Pâris's fee, and the protocol it implies : agreement of the landlady, return to the reception room where the girl is chosen, significance of the choice. The Pâris is here ironically named the abbess, i.e. the mother superior of a convent whose rule she enforces : according to a metaphor usual in libertine literature, the custom that governs the brothel is modeled on the rule of the convent, with its protocol and submissions that govern here the action of bodies, if not souls.

The structure of the rule, with its differential play of the permitted and the forbidden and its taxonomy of tariffs, is opposed by the device of use, which associates, more or less exactly, more or less effectively, the rule with the actions of bodies : if the girl submits reluctantly to the rule, and manifests her " maussaderie ", if she " boude " or shows herself " revêche ", if she " se moque ", she compromises the " duty " to be rendered and risks rendering the client " impotent ", depriving him " of the amorous faculty ", no longer succeeding in " making him alive ". The girl submits, but without her full and free desire, or at least the fiction of her willingness, enjoyment does not happen the customer orders, but he is subject to the girl's goodwill, to the goodwill of his own body too. The use of bodies thus manifests more clearly, more bluntly than any other use, the middle way of chrèsis, by which the usant subject defines himself paradoxically asubjectively, or pre-subjective, outside the framework, the structure, the rationality of the Cartesian subject19.

The use of bodies in the episode at the Hôtel du Roule is a perfect example of the economy of withdrawal that characterizes Casanovian narration : Casanova exposes the customs of the house, and in relation to them the failings of Patu, who proves to be /// impotent after the first pass, and the sullen, vindictive, exclusive failings of the girls. At the same time, there is very little mention of Casanova himself, who by default is the only one who fully respects customs. Casanova thus portrays himself as an accomplished libertine, indefatigable in the pleasures of sex, yet never needing to show off. At the beginning of his stay in Paris, he portrayed himself as an onlooker20 attending the colorful tableau of the Palais Royal's promenaders (p. 721), its cafés, its tobacco (p.723) again as a spectator, he reports on theaters and opera again at the Hôtel du Roule, he witnesses " a scene " (" j'ai joui d'une scène, dont je n'avais pas d'idée ", p. 771) and " tableaux " (" the last painting that enchanted me in Paris was this one... ", p. 773) ; and it was almost as a tourist that he visited the Salon organized by the Royal Academy of Painting in the Louvre in September (p. 775) and made his entrance into the court at Fontainebleau (p. 777).

Casanova visits and collects paintings. But he enters these paintings. The painting is the medium, the interface of the use of the body : a painting offered, at a distance, to the scopic jouissance of a spectator, it is at the same time the painting of the very jouissance of the spectator turned actor. The use of the body tends, slips towards the use of the painting, which fetishizes its economy.

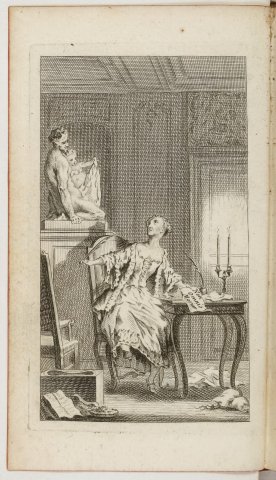

Le portrait de la belle Hélène : usage et tableau

At the start of chapter XIII, Patu leads Casanova to the Morfi, " a Flemish actress " (p. 855), in fact a prostitute. The episode is built on the symmetry of the Hôtel du Roule episode, where the relationships were reversed: the need, the desire that needs to be satisfied is no longer that of Casanova flattered by Coraline, but that of Patu infatuated with Morfi the misuse is no longer the work of Patu, who has become impotent after the first pass, but the work of Casanova, who refuses to sleep with Victoire Morphy's little sister, Louison, whom he calls Hélène, perhaps in reference to Zeuxis's chimera.

Casanova doesn't use the body offered to him in return for a financial transaction similar to that at the Hôtel du Roule. He gives the money, but he doesn't have sex. The girl shows him " a straw mattress on three or four planks " supposed to take the place of a bed :

" - Well ! Go and lie down there yourself, and you'll get the shield. I'll have the pleasure of seeing you naked. - Yes, but you won't do anything to me. - Not a thing. She undressed in the blink of an eye, lay down and used an old curtain as a blanket. She wasn't yet fourteen. She offers herself laughingly to my eyes in all the postures I... " (p. 855-857)

The tableau of the body replaces its use, or takes the place of it. Casanova enjoys little Hélène's body by sight alone. He enjoys a hidden body : " an old curtain serves as her cover ". The screen of the curtain steals from him what he has renounced. He finally enjoys a nubile, barely sexualized body. This body, on the other hand, is summoned to lend itself to all manner of postures: postures are the transposition of usage. The development of the scene, and the negotiation of postures to which it gives rise, is lost in the 2th version of the story, where a leaf is missing, but it survives in the 1st version :

" - Well ! Why don't you go to bed yourself /// the little shield. I want to see you.

It's not just a matter of raising the curtain (this term curtain is undoubtedly not purely contingent here and engages the theatrical metaphor), but of engaging in a transaction that is also a conversion from vision to touch, whose ultimate horizon is the girl's virginity. Usage and tableau: two regimes of the body are articulated here, with different economies. Hélène presents herself as an ideal picture of absolute beauty, "neither wench nor tattered", i.e., as an image that screens her real, filthy body. The picture is not a picture of the body, but of what can be projected and imagined from it. Hélène gives herself to be seen on the condition that she doesn't give herself away: she'll come out of Casanova's hands a virgin. The use, on the contrary, is the use of the real body, which Casanova washes, handles and could depucelate. The painting lies, then, because it doesn't offer the real body, but usage also disappoints: it's all about the removal of the virginity, about the wear and tear of novelty, and it's heading for the end. Between usage and the painting, the pricing of sessions highlights this difference in economies :

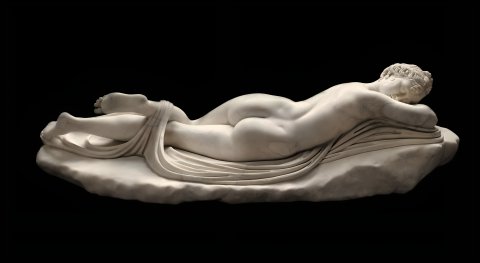

At the end of two months, her sister pointed out to me that I was the biggest dupe of all, since I had already shelled out two hundred francs to six at a time just for childishness. She attributed this to my avarice, despite the fact that I had already given six louis to a German to do a miniature portrait of her. He did it so well that she seemed alive. She was lying on her belly, leaning with her arms, and with her little throat on one ear and holding her beautiful head turned as if she had been on her back. The skilful artist had drawn her legs and thighs in such a way that the eye could not wish to see more. In this same posture I saw a hermaphrodite in London that we want to attribute to Coreggio21. I had O-Morphi written below the portrait. This Greek word, though not Homeric, means beautiful.

But these are the secret ways of very powerful destiny. Patu wanted a copy of this portrait, and I didn't refuse him. I ordered it from the same painter, who did it to perfection. But here is the moment of the happy combination22. " (p. 857)

La Morfi doesn't understand how Casanova spends his money, she feels she's cheating him with her little sister and deep down she despises him for it. La Morfi only understands the economics of body use : the more you use the girl's body, the more you pay the newer the body, the more you pay with " enfantillages " you waste with " enfantillages " you waste . /// his money and devalue the true use that will eventually be made of a body that will no longer be brand new.

Casanova reasons quite differently on the contrary, he capitalizes on what he spends, according to an economy of the painting. It's all about fixing and then monetizing the painting offered to him by little Hélène. The painting exists before the painter fixes it on canvas and distributes copies. The painting exists imaginary before it exists as an object, from the moment when little Louison becomes, for Casanova, Hélène, the beautiful Hélène of the painting of ideal beauty, the ideal of beauty whose painting the Greeks of Crotone commissioned Zeuxis to paint.

While he gives Louison six francs for each posing session, Casanova gives the painter six louis23 to execute the painting, i.e. twenty-four times more expensive, but four times less than the rate for depucating : he therefore makes a good deal !

For all that, Casanova doesn't claim to have anticipated and planned the sale of the young girl to Louis XV through the painting. Once again, it's a combination of circumstances: Patu asks for a copy of the first painting24, the painter shows this copy to the king's valet de chambre, who asks to see the original, and little Helena, fortunately left a virgin by Casanova, becomes Louis XV's mistress. Casanova points out this hiatus in what could order the structure of the story and is only the randomness of conjunctures : he begins by evoking " the secret ways of the most powerful destiny ", a providential order then, but immediately falls back on " the happy combination " of a chance that unexpectedly turned out well.

.The insistence on chance produces an effect of truth, for a scene at the king's house that Casanova has not witnessed and can only imagine. The scene is deduced, if not from the painting, at least from the device imagined by Boucher, which in fact constitutes its matrix :

" He sat down, took her between his knees, caressed her a little, and after making sure with his royal finger25 that she was brand new, and having given her a kiss, asked her26 what she was laughing at. She replied that she was laughing because he looked like a six-franc écu like a drop of water to another. " (p. 861)

The royal finger slipping into the sex of the beautiful Hélène, which itself repeats that of Casanova washing the young girl who stops him there, is fantasized from the posture Boucher gives his bonde odalisque, modeled on the brown odalisque he had already painted several years earlier. The painting engenders the writing of the event of which it is the product. The image of the young girl lying on her stomach, thighs spread wide, appeals to the imagination of the insinuating finger; the painting engenders the writing of this use of the body, which it bars at the same time by signifying its prohibition : the young girl only has value by exposing a sex that is always threatened, and always untouched.

.Casanova then imagines Louison's naiveté in recognizing her client's resemblance to the king's effigy on the six-franc écus, the prize, the coin precisely that Casanova gave her for each pose, for each painting. The king is thus also extrapolated from the painting, not by the content it represents, but by the price it costs. Seeing the king touch her sex, Louison sees again the shield given by Casanova to see and touch her, it is in fact the same scene always, always the same painting where Casanova is not but inserts himself, image without him but paid for by him, produced, provided for by him.

Little Hélène's laughter triggers the process that will lead to the tip of the /// narrative, to the witticism by which the Casanovian signifier is reinjected into everyday discourse, in this case the nonsensical chatter of fat Morfi, the big madam sister:

Casanovian signifiers are reinjected into everyday discourse.

" What amused me greatly was the joy of Fat Morfi when she saw herself mistress of twenty-four thousand pounds. She couldn't find words strong enough to express her gratitude. She regarded me as the author of her fortune. I didn't expect such a large sum," she said, "because it's true that Hélène is very pretty but I didn't believe what she told me about you, and I was wrong, because if the king hadn't found her brand new, he wouldn't have wanted her and the king says he knows all about it. Come on. I didn't believe that an honest man of your caliber could exist. " (p. 861-86327)

" Ce qui m'amusa beaucoup " immediately follows " elle riait " : the little sister's laughter is succeeded by Casanova's amusement at the big sister's silliness. Louison's laughter is silly too she doesn't understand why the king in front of her looks like the effigy of the ecus she receives for her poses she doesn't understand that it's the same person. But does this incomprehension amuse her, can it amuse the king, who is reduced to this simple tariff? It's from Louison's laughter, which refers to the écus paid by Casanova, that Casanova's amusement is in fact first born.

Casanova thus becomes part of a chain of incomprehension, from the little and big O-Morphi, to the king himself, who can't understand why this resemblance that tarifies him is so amusing. The degradation of all the characters enables the integration of Casanova, degraded, disqualified from the start by the reprobation of the madam sister, who finds him wasting her money.

But by the way, is this the real reason for her disapproval ? The young blonde odalisque, showing her bottom with legs spread, adopts the posture of " a hermaphrodite in London that they want to attribute to Coreggio ". Correggio never painted a hermaphrodite, but the Louvre has a Roman copy of Hermaphrodite endormi, a 2nd-century CE marble sculpture that belonged to Pope Pius VI (the Count Braschi that Sade features in the Histoire de Juliette). Casanova himself identifies his voyeuristic fantasy of the young O-Morphi with the misguided desire for an ambiguous body offered to sodomy. The episode of Ismaïl in Constantinople already associated voyeurism of the female body and homosexual enjoyment with a companion.

The pimp sister's contempt is therefore not just contempt for wasted money, but contempt in the face of a rogue jouissance, in the face of a perversion of jouissance, between impotence and inversion. It allows us a posteriori to reinterpret the Hôtel du Roule episode as one in which Patu's impotence (which, after all, is perhaps also an affabulation) already figured Casanova's ambivalent relationship to jouissance, between impotence and over-power, between male over-virility and inversion. Casanova and Patu offered each other the spectacle of their hetaïres, like Casanova and Ismaïl, like here, by interposed painting, Casanova and the king, partners in the use of Louison's body.

The king's intervention restores regular use of the blonde odalisque's body. The pension the fat O-Morphi receives reverses her judgment Casanova will have made her fortune, he is worthy of respect and admiration. But the way she expresses her feelings is almost an antiphrase: " I didn't think a /// honest man of your caliber could exist " ; honest is the word, the line that closes the anecdote, and the signifier by which Casanova injects himself into a story he at best only witnessed from afar, but in any case is not the protagonist he claims to be. Honest is a falsified signifier for a falsified story. But this falsification is in a way put into abyme in the narrative, which denies any use of little Hélène's body, and on the contrary pinpoints the fact that she is for him only a painting, that it is even a copy of the first painting, a copy of a copy, that has ensured the " happy combination ".

Thus, the use of the body ultimately boils down to a use of the word, the " honest " word of mind.

Notes

.By contrast, the paintings of little Morfi in the posture Casanova describes here are known : these are the paintings by Boucher (Munich version, B7506, and Cologne version, B7507), who had his entrances at court and traded in exactly this kind of canvas. Boucher was painting opera sets at the time, so Casanova may well have met him through Italian actors.

But Casanova doesn't mention a meeting with Boucher that he would have had no reason to keep quiet if it had taken place. The mysterious German painter makes the story unverifiable, and leads us to suspect that Casanova's insertion in the story of little O-Morphi is an affabulation... The diary of police inspector Jean Meunier reveals that Boucher sold his painting to M. de Vandières.de Vandières who showed it to the king the king asked to see the young girl and made her his mistress, probably in 1752. (Journal de Meunier, note of May 8, 1753, Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, Bastille 10234)

///This presentation is dependent on the work of Michel Foucault and Giorgio Agamben on the notions of usage and chrèsis. See Michel Foucault, L'Usage des plaisirs, Gallimard, 1984, I, 2, and Giorgio Agamben, L'Usage des corps, trans. Joël Gayraud, Seuil, 2015. Agamben refers to other texts by Foucault, notably L'Herméneutique du sujet. Cours au Collège de France (1981-1982), EHESS, Gallimard, Seuil, 2001, as well as to Recherches sur χρή, χρῆσθαι. Étude sémantique by Georges Redard, Paris, Champion, 1953. Agamben strongly inflects Foucault's theses in a Heideggerian sense, and it is in Heidegger's sense that the world is to be understood in the notion of the use of the world developed by Agamben. In this presentation, however, where the use of the world will play an essential role, the world is taken in the sense of the classical language: it is the world of the mundane, the space of exceptional sociability where the desirable beings of the society of the spectacle evolve. This is not to say, however, that Heideggerian phenomenology is absolutely inoperative to account for also this use of the world.

The gondola here refers, curiously, to the stagecoach. Earlier, Casanova wrote " la diligence gondole " (p. 706). In the second version, he develops an entire comparison between the Venetian gondola and " the French gondola " (p. 705).

Elena Riccoboni, known as Flaminia, should not be confused with the novelist known as Mme Riccoboni : Mme Riccoboni is the wife of Flaminia's son.

Marivaux, La Vie de Marianne, ed. Frédéric Deloffre, Garnier, 1963, p. 167-168. According to F. Deloffre, Marivaux would here be portraying Mme de Lambert, who died in 1733, i.e. while Marivaux was in the midst of writing his novel, the fourth part of which would appear in 1736.

Molière, Amphitryon, I, 2, 412-415. In Plautus, the question of one's name is the main thread running through the exchange between Mercury and Sosie : " Formido male, ne ego hic nomen meum conmutem et Quintus fiam, e Sosia " (I'm bloody afraid I'll have to change my name today and become Quintus instead of Sosie, v.305) ; " mihi certo nomen Sosia'st " (what's certain is that my name is Sosie, v. 332) ; " Quid ais ? quid nomen tibi'st ? - Sosiam vocant Thebani, Davo prognatum patre " (What do you say ? What's your name? - The Thebans call me Sosie, son of Davus, v364) ; " Argumentis vicit; aliud nomen quaerundum'st mihi " (He has the arguments to convince ; I'll have to find myself another name, v. 423)

See Giorgio Agamben, " L'homme sans œuvre ", L'Usage des corps, op. cit., p. 25-51.

" pour tous les jours " in the first version (p. 720) is clarified in the 2e version : " pendant tout le temps de mon séjour à Paris ". The subjective correction (mon séjour) and objective at the same time, by specifying the duration, according to the double movement we observed in the study of the encounter with Cattinella, at the beginning of chapter IX.

This reciprocal remark about Montaigne is not present in the first version of the text. Similarly, later in the same chapter, when Casanova, attending Campra's Fétes vénitiennes at the Opéra, criticizes the set, where the layout of the buildings lining Piazza San Marco has been reversed, he adds in the second version, to his neighbor : " being Venetian I had the same reason to laugh at this mistake that he himself would have seeing in Venice a painting where he would see the Pont neuf with the Samaritaine on the left side seeing it from the Louvre.(p.751) The first draft establishes, through use, mastery over the other, who makes a mistake, who doesn't use it well but this mastery is immediately released, through politeness, the acceptance of reciprocal misuse. Everything is played out on this seductive edge, where mastery is conquered only to be immediately returned.

To Patu, whom he has just met and who accompanies him to the door of Silvia's house, Casanova assures that " it was the only house in Paris I could count on ".

Similarly, in the first version, p. 726.

Carlo Antonio Veronese made his debut with Le Double Mariage d'Arlequin on May 6, 1744, in which his daughter Anna played Coraline. He also wrote many of the outlines for the commedia dell'arte plays performed with his daughters.

Giacomina debuted in Paris ten days after her father and sister, in Coraline esprit follet. She became Camilla on 1er July 1747 alongside her sister in Les Deux Sœurs rivales. When Coraline retired in 1759, Camille took over her sister's soubrette roles. Camille contributed to Goldoni's success in Paris, playing the lead role in Les Amours d'Arlequin et de Camille (1763), La Jalousie d'Arlequin (1763) and L'Inquiétude de Camille (1764).

Coraline " was maintained by the Prince of Monaco " and, " having a lover in title, she could only receive me at inducted hours " (p. 761).

In 18th-century Italian nobility, the sigisbee was the knight-servant of a young married woman, with the approval of her usually older husband. The term is used elsewhere by Casanova. But here Coraline is only the mistress of the prince, who himself is only 30.

" I had been thought guerluchon for a month, and it was not so. " (p. 763) Guerluchon, or greluchon, from grelot, for testicle, refers to the kept lover of a prostitute.

La /// Garenne, currently La Garenne-Colombes, is in the Hauts-de-Seine department near La Défense. Casanova systematically wrote " la garenne ", without capitalization.

One louis is equal to 24 francs or pounds, so each service is priced at double the previous one.

The first chapter of this book, entitled " La curiosité des Parisiens ", begins with a stroll through the Palais-Royal that should be compared to Casanova's in chap. X (p. 721). The narrator spots two rather shady women, " des filles de chez la Pâris ". One of them is Richemont, precisely the woman Patu chose on his arrival (p.769). In chapter XXII, Émilie's story is the occasion for another visit to the Palais-Royal.

Descartes is absent from the bibliography and is only mentioned once in L'Usage des corps. Again, this is through Michel Foucault, from whom Agamben inherits the notion of chrèsis in its relation to a hermeneutics of the subject : " the subject implies an ontology, which is not, however, for Foucault, that of the Aristotelian hypokeimenon nor that of the Cartesian subject. [...] Descartes' specific contribution is in fact to have "succeeded in substituting a subject founded on practices of knowledge for a subject constituted thanks to practices of the self." " (L'Usage des corps, p. 155) The hermeneutics of the Foucauldian subject inherits the Cartesian revolution of the subject, even if, undoubtedly, it arranges its structuring rigidity into the management of practices ; but this Cartesian heritage is foreign to the use of bodies as thought by Agamben.

Paris is defined as a city-spectacle offered to onlookers : " the onlookers who heard it " (p. 725)

The reference to the hermaphrodite is not in the 1st version.

This sentence is an addition from the 2nd version.

As Casanova presents this painter as a German, it has been imagined that he could be the Swede Gustav Lundberg (p. 858, note 2), who was essentially a pastelist of court portraits. Not only would the austere Lundberg never have painted this kind of picture, but he had left Paris in 1745, first for Spain and Portugal, then for the Stockholm court, where he was appointed hovkonterfejare (court portrait painter) in 1750.

In fact, there are two paintings by Boucher depicting Marie-Louis O'Murphy as an odalisque. Neither of them ever belonged to Patu or Casanova...

From his royal hand in the 1st version.

All that follows in direct style in the 1rst version.

This passage is completely rewritten compared to the 1st version.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « L'usage des corps », Casanova, la séduction des possibles, cours d'agrégation donné à l'université d'Aix-Marseille durant l'année 2020-2021.

Casanova

Archive mise à jour depuis 2020