" She's very sensitive : yesterday after supper, I was reading her a book, in which is the epistle of a certain Ariadne, to a traitor named Thésée, who had abandoned her on a desert island, while she was asleep : In the middle of my reading, I cast my eyes on Tiennette, and saw her all in tears. O mon Dieu, qu'elle était aimable comme ça ! " (Rétif de la Bretonne, Le Paysan perverti, letter V from Edmond to his brother.)

The economy of Lettres de la Marquise is enough to surprise the modern reader : these letters without context, virtually without event, from a single woman addressing a man whose replies, declarations, bills we must assume, but from whom we never read a line, seem to us to constitute a truncated, lacunar, imperfect work. We suspect the bizarre, even saucy bias of a young author, a singularity that would be if not clumsiness, at least the timidity of a neophyte creator.

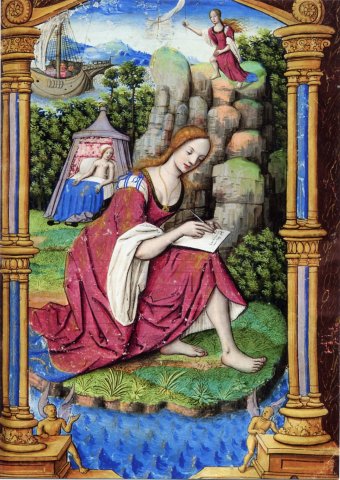

Ariane writing to Theseus, translation of Ovid's Heroids by Octovien de Saint-Gelais, illuminated manuscript by Jean Pichore circa 1510, Héroïde X, 30x21,5 cm, Paris, Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal

This is not the case. Crébillon, by giving the floor only to the Marquise in a series of letters that ostensibly turn their backs on narrative writing to describe psychological states, is part of a long literary tradition that can be traced back to Ovid's Héroïdes .

I. Origin of the genre: Ovid's Heroids

Composed between 20 B.C. and 8 A.D., the surviving Heroids consist of twenty-one letters in elegiac distichs which, for the most part, are supposed to have been written by heroines of Greek tragedy (Phaedra, Hermione, Medea), Homeric epic (Penelope, Briséis) or Virgilian epic (Dido), and more generally of ancient romance and mythology (Ariadne, Hero). The common theme of these letters is flight, or indifference, or contempt for the beloved.

Ovid doesn't invent any of these characters, whose stories are familiar to the reader, and even hackneyed. Narrative elaboration is therefore superfluous. It is supposedly acquired in order, from a universally shared fictional framework, to be able to deploy a stasis, an elegiac lament, a lamento, in a word an epistolary monody.

Supposedly, a friend of Horace's, Aulus Sabinus, composed replies to these heroics, the masculine responses of lovers to their forsaken mistresses. But these replies have been lost. However, of the twenty-one preserved heroides, three are the male counterparts to the epistles of forsaken lovers: Pâris' to Hélène, Léandre's to Héro, and Acontios' to Cydippe. In 1480, the Italian poet and humanist Angelus Sabinus (Angelo Sabino), composed three apocryphal responses as those of Aulus Sabinus : Ulysses to Penelope, Demophoon to Phyllis, Pâris to Œnone, which he included in his edition of the Héroïdes. They will be regularly included in later editions1.

This editorial history is significant : Ovid founds a genre, epistolary monody, and this genre calls from the outset for a supplement ; it creates a void to solicit a response. This void is twofold, and consubstantial structurally, it's the silence of the person addressed in the letter thematically, it's also the absence of the person who's writing the letter it's also the absence of the person who's writing the letter it's also the absence of the person who's writing the letter. /// whose painful anguish the letter expresses. Even when the answer is not there, the presence of the letter's addressee is constantly solicited in the text itself: the elegiac void that circumscribes the poetic subject, that defines his state, that characterizes in hollow, in negative, his symbolic status, is superimposed by the phantasm, the haunting, the phantom of the object of desire, likely to fill this void. Fundamentally, the supplement is inadequate : the object cannot take the place of subject, the absence of presence, the lability of the male figure, of consistency, permanence, female substance.

.Ariane à Naxos

Among Ovid's heroids, two play a decisive role in founding and characterizing the genre of epistolary monody these are Ariadne's heroid (epistle X) and Dido's (epistle VII). Ariadne, abandoned on Naxos by Theseus, who has secretly weighed anchor to join his father Aegeus in Athens, at first perceives her lover's absence only through her sleep:

It's an epistolary monologue.

" In that moment of uncertain awakening, all languid with sleep, I stretched out to touch Theseus still apprehensive hands ; no one beside me ; I stretch them out again, I search again ; I wave my arms across my bed ; no one. Fear snatches me from my sleep I rise in horror, and rush out of this lonely bed. My chest immediately echoes beneath my hands, which strike it2. "

Like a ghost between dream and wake, Theseus fades away. Absence has to do with the ghost, the φάντασμα, both the imagined, dreamed representation of the lover, and the specter, the vague awareness of his absence, which itself reverberates in the imagination. Ariadne is defined by her dream, that is, by the ghost of Theseus absent Theseus takes the place of Ariadne dreaming Ariadne's elegy is filled with this ghost of an object that inhabits the writing subject.

But Ariadne is hollow : she doesn't speak, but beats her chest, which, hollow, emptied by Theseus' absence, resonates. The elegy is identified with this resonance the heroine's air is the resonance of this hollow, this emptiness that takes the place of the female subject. All the images that follow feed into this play of emptiness that organizes the elegiac supplement :

" sobs made up for what my voice lacked. Blows accompanied the words I uttered. As you could not hear me, I stretched out my arms towards you, so that you could at least see me, making signals3. "

The central void is the void of the subject : it's not, first of all, Theseus' absence, it's Ariadne's silence, her inner emptiness... She is speechless. Sobs take the place of speech: tears, like the sea where Theseus disappeared, fill the void of voice, the lack of speech. The blows are Ariadne's hands beating her chest, the resonant expression of her inner emptiness. Finally, the arms outstretched to beckon towards the disappearing sail are extended " towards you ", as if to encompass, to embrace the object of desire, Theseus.

" Unhappy ! I stretch towards you, from whom the vast sea separates me, these hands tired of bruising my gloomy breast. [...] Come back, may the winds bring you back! If I succumb before your return, at least you'll bury my bones4. "

The song links the subject to the object, conjuring it back. The whole letter is organized around the inversion of the phantom: it opened with the awakening of consciousness to Theseus' absence, with the emergence of a consistency of Theseus as phantom it ends with a projection towards Ariadne's death, towards Theseus' return to the object. /// Ariadne's ghost. The letter accomplishes the definitive destruction of the subject, the elegiac song rests on the spectralization, the negation of the feminine " I "

.Didon abandoned

Epître VII from Didon à Énée reproduces the same device : facing the sea, Didon, queen of Carthage, addresses her swan song to Énée, whom she welcomed after the ruin of Troy and the storm provoked by Juno, with whom she fell in love and whom she now sees leaving to conquer Italy.

" Such, leaning over the wet reeds, the swan with white plumage sings on the banks of the Meander, when the fates call him. It is not in the hope of bending you by my prayer that I address these words to you: I am driven to it by a god who is against me. But after losing for an ingrate the fruit of my blessings, my honor, a chaste body and a prudish groin, it is little to lose words5. "

The beginning of the epistle identifies the abandoned lover's speech with a loss : it is a swan song, a speech without hope of return (nec quia... sperem). The song describes how the lover empties herself (perdiderim, perdere). Faced with a subject who empties himself as he speaks, the object of desire, Aeneas, takes on consistency only as a dream : it's the dream of the founding of Rome :

" You have resolved, Aeneas, to untie both your anchor and your faith, to seek a kingdom of Italy, which you do not even know where to find. [...] You flee from what is done, you pursue what is yet to be done. You must search the world for another land. And if you find it, who will give you possession of it? "

To leave for Italy to found Rome is to leave the real, Carthage, for a fantasy, for the Roman fantasy par excellence that is Rome. Identified with the supreme fantasy, Aeneas triggers, fuels the ghostly machinery of the elegy, right up to the final inversion :

" What have you before your eyes the sad image of her who writes to you ? I'm writing to you, and the Trojan sword is close to my breast. Tears flow from my cheeks over this naked sword, which soon, amidst tears, will be drenched in blood. [...] When the fire of the pyre has consumed me, the name of Élise, wife of Sichée, will not be engraved on my tomb, but this inscription will be read on the funerary marble: Énée, the author of her demise, also provides the instrument. Dido perished struck by her own hand6. "

Aeneas' initial ghost, the dream for which he left Carthage, is inverted here into the ghost of Dido, whose tomb inscription designates the empty envelope. Indeed, the tomb will bear not the full name of the queen of Carthage, of Elise wife of Sichée, but the name of Aeneas her murderer : by the Trojan sword he abandoned to her, by his very name, Aeneas fills the tomb of her who, dishonoring her first husband, lost her name.

The Ovidian device

Ovid gives us the basic device of epistolary monody : it's not a " classical ;" invention; it's neither a creation of Racine, nor an emanation of the moral literature of the Grand Siècle. It's a much older heritage it's that background of ancient culture which, in our culture, has founded, delimited what M. Foucault calls a " usage des plaisirs ", which defines, for pleasure, a measure and a disproportion, elegy being the representation, the celebration of this disproportion. What the heroines are saying is that culture is made up of nothing but the abuse of pleasures, and that this abuse is the foundation of song, the female subject as emptiness, the object of desire as that which supplements this emptiness, death as the consequence of this supplement.

.The use of pleasures comes only as a logical second stage of culture, as a reparation or conjuration of elegiac abuse and its consequences. /// ghosts. The use of pleasures introduces moral problematization. In the history of the genre of epistolary monody, this problematization is therefore not constitutive; nonetheless: Ovid's moralization, like the apocryphal responses to feminine lamentos, very early on fill the lyrical feminine void of the primitive Ovidian scene, of which Ariadne at the rock and Dido abandoned fix the epitome.

.There's a whole medieval history of the moralization of Ovid7, which passes through its rewriting, through its insertion into a discourse of symbolic regulation, and constitutes a major cultural axis at the dawn of the Renaissance : it culminates in Christine de Pisan's Épître d'Othéa. Othéa is a personification of Prudence and the author's spokeswoman. In the tradition of the prince's mirrors, she writes a hundred Trojan stories to a young knight, Hector, to teach him his trade and his duties. Othéa is not a jilted lover she is not writing to a fickle lover there is neither elegy nor sorrow but all Ovidian matter is summoned and stirred up in such a way that the female voice, monodic and epistolary, is identified not only with a moral problematization, but with the political horizon of the prince's mirror.

.II. Romantic attraction: Hélisenne de Crenne

It's important to stress that, in its original Ovidian model, epistolary monody has nothing to do with novelistic narration. It reflects, in the form of lyrical states, a pre-existing event or circumstance. Whereas the narrative subject is a full subject, establishing a point of view and constructing a signifying sequence, the lyrical subject is an empty, collapsed subject, undoing meaning and deconstructing the event. The two forms, of epistolary monody on the one hand, and novelistic narration on the other, are antinomian.

However, the novel has endeavored to ward off this antinomy : the moral problematization of the Ovidian model has been succeeded by an attempt at novelistic colonization.

Les Angoisses douloureuses: an Ovidian model on display

A century after Christine de Pisan, in 1538, Marguerite Briet, whose pen name was Hélisenne de Crenne, published Les Angoysses douloureuses qui procèdent d'amour8, a novel in which the narrator uses letters9. The novel's title in a way synthesizes the Ovidian model, while the heroine explicitly compares herself to those in the Heroids:

" O that blessed are those who from the flame of love are sequestered, but infelicitous is who without refrigeration and rest always toils, ard and is consumed like me, poor and wretched, who with sobs and moans incessantly feast. And am so agitated and persecuted by this conflagration that not only the veins, but the joints, nerves and bones are so cruelly tormented that my dolent soul, weary of being in this sad body, desires only separation, knowing that it cannot suffer more grievous pain than it feels from such a parting. For never Porcia for Brutus, nor Cornelia for Pompey, nor Laodamia for Protesila, nor the magnanimous Carthaginian queen for Aeneas, all together so much mourning suffered that I, poor unfortunate, feel10. "

Not only do the last two references refer to Dido's epistle VII to Aeneas11, and to Laodamie's epistle XIII to Proteilsas, but in the description of Helisenne's condition we find the inner collapse of the female lyrical subject, here under the spun metaphor of the fire of Love, recurrent and even commonplace in Ovid : if the separation of soul and body Christianizes the ancient model, the form of lamentation, the depressive shift are characteristic of epistolary monody.

The first part of Angoisses douloureuses begins with the marriage of the very young Hélisenne to " un jeune gentilhomme, à moi étrange " (p. 34), a foreigner therefore. Hélisenne is happy, but has not chosen him. She goes on a trip with her husband to a nearby town for a trial. There, from her window, she meets the gaze of a young man at the opposite window12 (p. 37) : this is the beginning of a fiery passion between her and Guénélic. Hélisenne's husband catches their glances (p.40) and decides to move out (p. 44) nothing happens. The lovers look at each other, then talk in the temple (p.60), then exchange letters (p.61) but Hélisenne no longer goes near the window (p.68), her husband having forbidden her to look at her friend. However, having gone with her husband to divine service in a monastery, she can't help looking at her friend with her eyes (p.69). Her husband brings her home, reproaches her, and she goes into a rage, contemplating death (p.71). He sends her to confession, tries to distract her by getting her interested in his trial nothing works. She manages to talk to her friend, only to be surprised by her husband, who beats her (p.99). Their meetings continue until the husband decides to send Hélisenne away (p.132), to Château Cabasus (p.136). There Helisenne is locked in a tower (p. 137).

In the second part, Guénélic recounts how, with his companion Quézinstra, they criss-cross Europe in search of Hélisenne. In the final part, Quézinstra takes the floor to tell what became of the two lovers, right up to the tragic denouement.

The elements of a new sentimental topic are thus taking shape: an adultery entirely concentrated in the exchange of glances ; an imprisonment that replaces lamentation by the sea ; the beginning of a moral problematization of pleasure, not in the deliberative form adopted by the nouvelle galante or the tragic monologue in the following century, but through the somatization of passion, which degenerates first into irrepressible attraction, then into fury and bewilderment. Gradually, elegiac complaint evolves into analysis and introspection.

Letters in the novel: the bedroom to tip the balance from elegy to introspection

The Ovidian topic of feminine emptiness is then challenged by the courtly heritage of a specifically feminine science of love, enveloped by the discourse of virtue :

" Mine sigillai letters, and, with great desire, found subtle means of consigning them to him, and he received them joyfully. And all of a sudden, after showing them to him, I retired to my room, where I was more willingly alone than accompanied, to continue more solitarily in my fantastic thoughts. And in such solicitude, I revelled in reading my friend's letters, then looked at the duplicate of mine, distinctly considering all the terms of both. And, as I occupied myself in such solicitous exercises, my husband appeared, of whom I took no heed who, howling, with his foot by great impetuosity, opened the door of my room, from which I was so wonderfully disturbed that I had neither notice nor discretion to hide the letters. " (I, 10, p. 65.)

We see here how the displacement of /// The shift from elegy to introspection relies on a change in the place of fiction no longer the open, cosmic space of complaint, the theatrical display of amorous pain, but the retreat, the solitude, the bedroom. The bedroom is, at least in the first part of Angoisses douloureuses, both the novelistic site of exposure to the gaze, when Hélisenne goes to the window to meet her friend's gaze, and, when she refuses to show herself, to expose herself, the enunciative frame of epistolary monody, a precarious frame that can be interrupted at any moment by the event : from the outside, the irruption of a husband from the inside, in the letter itself, the narrative opening of the event. The discourse in the bedroom, introspective, closed in on itself, reclusive, is then opposed by the noise, the shout, the brutality of the event.

The letter as pleasure regulation

The speech is a solitary pleasure : brought with the beloved's letter, the lover " receives it joyfully " ; pondered in the bedroom, it constitutes the " fantastical thoughts " of the imagination read in the lover's letter, it delights (" I delighted in reading my friend's letters "). But precisely because it is circumscribed by the bedroom, because the brutality of the outside world that threatens this epistolary enclosure sets a measure, a limit, for it, this discourse is a discourse of the use of pleasures :

" And after reading them, I had an incomprehensible and inestimable joy and consolation, for by his writings, he claimed to be mine in perpetuity. And then I began to cogitate and think within myself what answer I would give to his letters and it seemed to me that it would not be good to acquiesce promptly to his request, because the things that are easily obtained are little appreciated, but those that are acquired with great toil are esteemed dear and precious. For these reasons, I wrote him letters by which he could hardly hope to achieve his intention. " (I, 9, p. 63.)

The introspective meditation of the epistolary lover is aimed at regulating pleasures. It's no longer a matter of running to death but, from the present intensity of pleasure to its final consummation, of making that pleasure last as long and as intensely as possible, of delaying its consummation through regulation. Hélisenne is explicit here about the rules of the epistolary game, which will become implicit in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but will continue to be played out in these very terms: the lover's discourse announces a perpetuity of pleasure (" by his writings he claimed to be mine in perpetuity ") ; the lover defies this perpetuity, interprets this gift as a demand and, on the basis of this demand, organizes a haggling : she raises the prices and thereby regulates a use of pleasures, an intensity, a duration.

Death is always the horizon of the epistolière's discourse, but a horizon that the establishment of a use of pleasures, of a measure, undertakes to ward off :

" For, if you consider well, you must not persist in such loves, which do not consist in virtue, because it would be impossible for me to satisfy your affectionate desire without denigrating and annihilating my good name, which would be more acrimonious to me than a violent death, because I do not esteem those alive, whose good name is extinguished, but must esteem themselves worse than dead, and on the contrary of those who have done virtuous deeds, whose names sempiternally endure, and in spite of the cruel Atropos : even though their demolished bones lie in ashes, they must consider themselves alive, and we must persuade ourselves to follow them by virtuous customs, which make man immortal. " (I, 10, pp. 63-64.)

Hélisenne's letter to Guénélic presents itself as a veritable conjuration of the Ovidian epistle : it's a question of not ending up dead like the lovers of the heroids, of turning the ignominious death of those who have abused pleasures (" but must esteem themselves worse than dead ") /// into " good fame ", to pass from the ashes of dead Dido to the living ashes of virtue (" those who have done virtuous deeds, whose names sempiternally endure ").

Lyrical persistence of the Ovidian model in the classical age

Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, this shift from elegy to introspection will coexist with the persistence of the Ovidian model, founded on the complaint and abuse of pleasures, on that feminine emptiness that vainly calls for the object of her desire, an object that never ends in failing to fill her. This Ovidian model is to some extent synthesized by the Italian epic, with Armide's lamentations at Renaud's departure, in Canto XVI of Tasso's Jérusalem délivrée (1581). The three forsaken lovers - Ariadne in Naxos, Dido in Carthage, Armide on the mirage of her Fortunate Island - nourish theater, painting, opera, ballet, until they gradually lose their narrative singularities and become, in the eighteenth century, interchangeable cultural representations.

To cite just one example, the three-act libretto of the Didone abbandonata composed by Metastasius in 172413 was used for a century by over fifty different composers, including Porpora (Reggio nell'Emilia, 1725), Hasse (Die verlassene Dido, Dresden, 1742 Berlin, 1769), Jommelli (1747 Stuttgart, 1751, 1763), Piccini (1770)... In 1734, Lefranc de Pompignan gave a Didon in five acts and verse at the Théâtre des Fossés Saint-Germain. It would be replayed several times during the century, and at least ten times during the revolutionary period14.

III. The lyrical χώρα: the Portuguese Letters

But the epistolary monody genre itself received a decisive boost with the publication in 1660 of the Lettres portugaises traduites en français, in Paris by Barbin. The publication was anonymous today, the letters are generally attributed to Guilleragues, a magistrate of Bordeaux origin, from the circle of Scarron's wife Françoise de Maintenon, also known to Mme de Sévigné15.

The Lettres portugaises are presented in the original edition as a small in-12 book, containing five letters and 66 pages. Their success would be considerable, as evidenced by the three pastiches that followed from 1669 : a second part with seven new letters, Réponses published in Paris (five letters), other Réponses printed in Grenoble (six letters)16. There would be verse adaptations in the eighteenth century, such as the Lettres portugaises en vers by the Marquis de Ximenes17, or Dorat's Lettres d'une chanoinesse de Lisbonne à Melcour, officier françois18.

Mariane: a cloistered Ariadne. The bedroom versus the stage

The Lettres portugaises are written on the model of the tenth heroid19. The letter writer is not Ariadne on her rock of Naxos, but Mariane Alcoforado20, Portuguese nun seduced by a French officer who has sailed back to France and will never reply to her letters. The first letter reads :

" cease, cease, unhappy Mariane, to consume yourself in vain, and to seek a lover you will never see, who has crossed the seas to flee you, who is in France amidst pleasures, who does not think for a single moment of your sorrows. " (P. 7221.)

Mariane echoes Ariane, the sea and France the Aegean and Athens, the officer's flight the flight of Theseus. Dorat's 1770 engraving, showing the sails of the French ship through the nun's window, underlines this parallel. Yet the discourse has changed: Mariane addresses her unfaithful lover only indirectly, and instead addresses herself. As a reclusive nun, she incorporates her reclusion into her discourse, addressing her pain only to herself. Critics have commented extensively on the first sentence:

.

" Consider, my love, to what excess you have lacked foresight. " (GF, p. 71.)

Amour should a priori designate the lover, and the heroic model, and the heroic model encourages us to read this address to the letter's recipient as an address from the letter-writing subject to the object of his desire. Yet the meaning of the sentence clearly indicates that it is to herself that Mariane is speaking, to her own desire, within herself, and not to the object of her desire. Yet the meaning of the sentence clearly indicates that it is to herself that Mariane is speaking, to her own desire, within herself, and not to the object of her desire, the Frenchman who has left. It is she, Mariane, who lacked foresight, who didn't foresee that " so many plans for pleasures " would plunge her into " mortal despair ".

Racine and the expression of passions

Because Guilleragues had planned five letters, Léo Spitzer, in his article on the Lettres portugaises22 identifies their structure with that of a Racinian tragedy, with its five acts23. In Guilleragues' work, there would be a theatrical expression and progression of passion. This reading by Spitzer has had important consequences, notably on Crébillonian criticism, because of the implicit homage that the monodic structure of the Lettres de la marquise pays to the Lettres portugaises : Crébillon's Lettres would be the locus, the means of a Racinian expression of the passions. Jean Sgard rightly proposes, in this legacy, to distinguish between style and situations :

" The breathless style, the language of passion is everywhere present here, as it was in the Portugaises, in the Lettres de la Présidente Ferrand or in Boursault. The most profound trace, however, remains that of Racine. It has less to do with the tragedy itself than with the harmony of the song. Sometimes the quotation is very close, and the lyrical monody seems to rely on it. [...] It's Bérénice ; but Crébillon adapts, transposes ; we won't find in his story any Racine situation, any great scene, any dramatic dialogue24. "

We're no longer talking about a Racinian progression of plot, nor a Racinian theatricality of passion, neither of which can be found in the Lettres portugaises, nor in the Lettres de la Marquise ; but can we dissociate these elements from a " style ", whose characterization by Jean Sgard (" style haletant ", " harmonie du chant ", " monodie lyrique ") refers us just as much to what we have defined, well upstream, from the Héroïdes to the Angoisses /// painful, as an ovidian model25 ? Philip Stewart, on the other hand, shows how, from the world of Racine to the world of Marivaux, Crébillon and Prévost, we move from the painful, unsentimental expression of passions to the emergence of sentiment, which becomes a positive category that the narrative subject appropriates and learns to enjoy26. Only in retrospect does the eighteenth century make Racine the poet of sentiment27.

Not only is there an epistemological break between passion and sentiment, between Racine and Crébillon ; but the theatrical model remains alien to Ovidian elegy and its classical epistolary avatars. The theatricality of the Racine stage is contrasted here with the withdrawal, the incommunicable chamber of the Portuguese nun. The works are indeed contemporary: Racine had Britannicus performed in 1669, Bérénice in 1670, Phèdre in 1677. There is, with Guilleragues, a real community of language, of style. But the spaces, the performance device is not the same : Phèdre comes out of silence and retreat to try to externalize, to communicate her passion. The time of the scene is the time of this externalization, of this communication. The Portuguese nun, on the other hand, speaks out after the disaster, when no communication is possible: the inner catastrophe we are given to see is breached, in the radical absence of any public space other than the distant political horizon of war and France. There is no expression of passions, but a collapse, a ruin of pleasures. In Phèdre, something long contained finds expression, is staged in Marivaux, expression is at first barred, denied.

.Collapse of the subject, saturation of pleasure: the masochistic disposition

From the very first lines, Mariane twice defines herself as " private " :

" What ? This absence to which my pain, ingenious as it is, cannot give a sufficiently ominous name, will thus deprive me forever of looking at those eyes in which I saw so much love, and which made me aware of movements that filled me with joy, that took the place of all things, and which finally were enough for me ? Alas, mine are deprived of the only light that animated them " (p. 71).

Only absence is there, a nameless, unspeakable absence, " to which my grief, ingenious as it is, cannot give a name fateful enough ". Absence deprives the subject (" me privera donc pour toujours ", " les miens sont privés de la seule lumière "). This present situation of absence and deprivation is contrasted with past evocations of a plenitude of pleasures. Seeing her lover's eyes, the nun experienced " movements " in other words, a sexual arousal that " filled her with joy ". The present emptiness, the absence that deprives, is contrasted with the past fullness that filled.

This fullness was a supplement of being : coming from the object of desire, it took the place of the subject (" which took the place of all things to me "). The Portuguese nun's speech describes the collapse of this supplement, in the tradition of the heroines in Ovid's Herods. What changes is the obsessive return of the evocation of pleasures. The discourse is inhabited by the regret of having abused them. These are no longer pure " painful anguish " (and Hélisenne de Crenne's already weren't), but the awareness of a perverse, masochistic shift from pleasure to pain, the setting up of a balancing of pleasure and pain :

" I destined my life for you as soon as I saw you, and I feel some pleasure in you /// sacrificing her" (l. 1, p. 71.)" the memory of my pleasures fills me with despair " (l. 2, p. 75)

" [your portrait] gives me some pleasure ; but it gives me pain as well " (l. 2, p. 76)

" je me meurs de frayeur que vous n'avez jamais été sensible à tous nos plaisirs " (l. 3, p. 78)

" I have had very surprising pleasures in loving you, but they cost me strange pains " (l. 4, p. 83)

" and I could not live without a pleasure that I discover and enjoy by loving you in the midst of a thousand pains " (l. 4, p. 84)

" I have forgotten all my pleasures and all my pains " (l. 5, p. 94)

There is no equivalence between pleasure and writing it is, on the contrary, a perverse substitution : the evocation of pleasure triggers pain the writing of pleasure supplements the pleasure that is missing, but supplements it with its flip side, pain.

Epistolary monody, monodic song proceeds from this perverse substitution : it creates a void, an absence, an incompleteness in the space of this void, it deploys elegiac lament, taut between the evocation of past pleasure and the expression of present suffering. In this deployment, the event is not first it is a condition of possibility, a tragic prerequisite to elegiac deployment.

The song, the tune merely reflects the event in a situation, a state, a masochistic disposition :

" I shall have pleasure in excusing you, because you may have pleasure in not taking the trouble to write to me, and I feel a deep disposition to forgive you all your faults " (l. 3, p. 76).

Same disposition to letter 4 :

" I resist all appearances which should persuade me that you hardly love me, and I feel much more disposition to abandon myself blindly to my passion than to the reasons you give me for complaining of your lack of care. " (L. 4, p. 82.)

The disposition identifies the female subject as that which receives the lover's absence, that which receives the pain of absence inflicted by the lover. Even as epistolary monody seems to promote a hypertrophied feminine " je ", the fact that this " je " is defined as disposition, situation, state, shows that it is a subject by proxy, an imaginary repercussion, in the artifice of a false feminine writing, of the pain manufactured by the absent from what it is absent.

The χώρα: device of epistolary monody

The woman who writes, or the simulacrum of a woman writing (an Ovid, a Guilleragues, a Boursault, a Crébillon), does not, however, define herself as a subject barré, tenaillé, torn apart by desire. Rather, she is χώρα (chôra28), an empty space welcoming pain, whose constitutive social relation is the relation to the absent insofar as the pleasure it could provide is missing.

What fascinates and explains the extraordinary success of these Lettres portugaises is not the stylistic, let alone narrative, quality of these five little letters : it's the device they fix, in its clearest and most obvious purity. The letter-writer is not simply an Ariadne, a Dido, a forsaken lover : she is a nun, whose cloistered status immediately figures the disposition of the feminine " je " as χώρα, as an emptiness that must fill a pleasure reversed into pain, a negation of the other.

" I cannot forget you, and I also do not forget that you made me hope that you would come and spend some time with me. Alas! Why don't you want to spend your whole life here? If it were possible for me to leave this unhappy cloister, I would /// would not wait in Portugal for the effect of your promises : I would go, without keeping any measure, to seek you, follow you and love you by all the world. " (P. 73.)

The reference to the convent comes at the end of the letter, to anchor the discourse of state to the emptiness of place (the convent in the love letters is pretty much a convent without God). The nun is eternally in a position of waiting in a forgotten room: she holds the discourse of memory in the place of oblivion. The cell, the room, is the opposite of the novel's stage: a space with no witnesses, no exit and therefore no possible theatricality, a mute space where speech, in vain, is lost. What makes these five letters poignant is that they carry this discourse into the cloister, a discourse that is lost, from the emptiness of a place to the absence of an interlocutor. There's a difference here with the Ovidian theatrical heritage, which goes back to opera: there's a scene for Ariadne, for Dido, abandoned, modulating their distress on the stage. There is no stage, and therefore no expression of passions for the Portuguese nun.

If there is no expression, what does this discourse say, which starts from a void to go towards another void ?

" some nuns who know the deplorable state in which you have plunged me, speak to me of you very often I go out as little as possible from my room where you have come so many times and I look ceaselessly at your portrait, which is a thousand times dearer to me than my life. " (P. 76.)

It's not the nun who cries, who laments, who speaks. It is her companions who feed her with the representation of the absent. The portrait of the absent is substituted for the lyrical subject " a thousand times dearer than my life ". It's not a passion that is expressed, it's a representation of the absent that saturates the space, that inhabits it, less as discourse than as vision.

The " deplorable state " is thus identified with the room where the image of the absent is received, in the form of the nuns' speech or the portrait looked at. The state, the room are saturated by this image, and this saturation turns pain into pleasure, i.e. the relationship to the absent into identification with his desire :

" Adieu, it seems to me that I speak to you too often of the unbearable state in which I am ; yet I thank you in the bottom of my heart for the despair you cause me, and I hate the tranquillity in which I lived before I knew you. Farewell, my passion increases every moment. Ah ! how many things I have to say to you. " (P. 81.)

What is unbearable is " the state in which I am " ; what the nun hates is " the tranquility in which I have lived " : hatred, pain are not directed towards an object, but aim at the collapse of the subject as a state, as a chamber, as a receptacle. The discourse speaks of the subject's reduction to this collapsed void.

In this void, a word rises : " je vous parle trop souvent " ; " Ah ! que j'ai de choses à vous dire ". These words are aimed at the lover, at the " despair you cause me ", i.e. her desire as lacking, her desire as able to provide pleasure.

.That is, it's not really an addressed word. We saw, at the beginning of letter 1, the ambiguity of the address, which appears to designate the lover, but in fact only designates the nun herself (" Considère, mon amour... ", p. 71). At the end of letter 4, the nun is explicit: " I write more for myself than for you ". The target is not the lover directly, but rather the absentee's desire: on the surface, the desire for the absentee; in essence, the desire that the absentee has, no longer has, for the letter-writer. It is from a collapsed state that a word rises towards this desire that is missing ; /// speech saturates the emptiness of this chamber-state, and this saturation takes the place of jouissance.

The balcony scene

The disposition to suffer, the unbearable state, identified with the chamber of the recluse nun, thus form the basis of the device of epistolary monody, a device that constitutes itself as a radical antithesis to the novelistic device of the scene. This is evidenced by the first-view scene in letter 4, set on a balcony with a panoramic view. The balcony frames the scene and arranges the visibilities it constitutes face to face a subject looking (from the balcony) and an object looked at (the lover, moving in the field of the nun's gaze) :

" Doña Brites persecuted me these past days to get me out of my room, and, thinking to entertain me, she led me for a walk on the balcony from which Mertola is seen; I followed her, and was immediately struck by a cruel memory that made me weep for the rest of the day she brought me back, and I threw myself on my bed where I made a thousand reflections on the little appearance I see of ever being cured. " (P. 85.)

From the balcony, the nun cannot see the town (or gate) of Mertola29. Instead of seeing, she is struck by a memory : " on voit ", " je fus frappée ", the active is carefully avoided. The nun is a dark room of sensibility: she cannot expose herself to the balcony, just as she cannot express her passion; everything leads her back to her room, in which " je fis mille réflexions ", that is, in which the saturation of unaddressed words inhabited, as it were, abstractly by the desire for the absent one rises. The vision comes only in retrospect, not as a real, present vision of Mertola, but as a past, painful recollection of what has been seen :

" I have often seen you pass in this place with an air that charmed me, and I was on this balcony on the fatal day that I began to feel the first effects of my unhappy passion ; [...] I convinced myself that you had noticed me among all those who were with me. " (P. 85.)

This reminiscence of the beginnings of passion allows us to compare two radically opposed regimes of fiction : on the one hand, the balcony of visibilities, which triggers the scene and promotes the theatrical play of passion (the amorous parade, the mines, the airs, the mute maintenance of the eyes) ; on the other, the chamber of invisibility, where depression is organized, both as an emptiness of self and, in this emptiness, as the saturation of the desire of the other.

From the Lettres portugaises onwards, we see two trends in the genre : on the one hand, the reintegration of the event into the epistolary game normalizes the elegy, bringing it back towards what becomes the novelistic norm of fiction. The letter thus establishes a polarity between the triviality of the event and elegiac saturation. We start from the scene and move towards what reverberates from it in the room of the wavering, stricken, threatened subject.

IV. Integration or exclusion of the event: The Lettres de Babet and the Lettres galantes

This is the tendency to which Boursault's Lettres de Babet, for example, belong, published in 1669, the same year as the Lettres portugaises : the fifty-three letters exchanged between Babet, a young Parisian bourgeoise from the Marais district, and her lover do not constitute an epistolary monody, and the plot is a bourgeois Roman plot. While Babet is in love, a stingy Norman gentleman arrives at her father's house and claims to marry her. Babet refuses, her brother intercedes on her and her lover's behalf : nothing can be done, and Babet is finally shipped off to a convent.

The other trend in the genre is the radical evacuation of the event. This is the tendency we encounter in the Lettres galantes de Madame ***, published by President Ferrand in 1691. The genesis of these letters, very similar in style to the Lettres de la Marquise, is characteristic. Anne Ferrand began publishing a novel, the Histoire nouvelle des amours de la jeune Bélise et de Cléante, in 1689, whose plot is very close to that of Hélisenne de Crenne's Angoisses douloureuses.

Bélise secretly loves Cléante, who doesn't take her seriously and treats her like a child. Cléante is himself engaged in an impossible passion for one of Bélise's relatives, who has taken refuge in a convent. A jealous Bélise considers taking the veil, but is warned off by her parents, who force her into marriage. A few years later, Cléante's mistress, whom he had secretly married, dies, leaving behind a child. Bélise tries to seduce Cléante, writes to him and takes care of his daughter. Cléante finally succumbs and begins an affair with Bélise in secret from her husband and father.

The third part of the novel, narrated by Cléante's confidant Tymandre, changes the perspective as in Les Angoisses douloureuses : for Tymandre, Bélise is a schemer. Cléante must leave on an embassy to Italy. The lovers resume their epistolary correspondence. When Cléante returns, Bélise is changed : Cléante discovers that she has given herself up to a pedant who shows her the sciences30.

The Lettres galantes which Anne Ferrand published two years later is presented as an appendix to this novel printed after it : Histoire des amours de Cléante et de Bélise, avec le recueil de ses lettres... In reality, the letters we read have only a distant connection with the novel. The characters' names have disappeared, and they contain almost nothing in the way of events. A false alarm in letter XXIII: " We had yesterday all the fright that gives women the appearance of a great peril : we thought we were drowned " (p. 20231) ; the husband's entrance, in letter XXXI, which surprises the letter-writer : " But my husband enters. Dieu ! What cruelty to see what one hates by leaving what one loves " (p. 206). In letter LIX, the letter-writer brazenly announces that she will not recount what happened to her husband : " I promised you in my last letter a long account of something that concerns my husband, but in truth I don't have the strength to think about him or talk about him for so long. Leave me32 of my word and content yourself with knowing that he now treats me in a manner quite opposite to that which you knew him : he has almost become gallant with me " (p. 224). In light of Crébillon, we can conjecture the causes : spurned or disappointed by his mistress, the husband returned to his wife, just as the Marquis de Crébillon returned to the Marquise after the end of his affair with Mme de ***33. These are about the only traces of event in the Lettres galantes : such distance, such severe filtering is a tour de force. Epistolary monody presupposes the installation of an enunciative void it's not just a question of evacuating the subject, but also the event. Anne Ferrand can't help but have the Ovidian model in mind. In letter LXVII she has her heroine say:

"I don't know what I'm talking about.

" Theseus was blamed less for having been sensitive to Ariadne's charms than for having /// abandoned the greatest of crimes is to violate one's oaths you made me love you tenderly. " (P. 229.)

Here we are reminded of the basic elegiac situation, the original device of the monodic complaint : Ariadne lamented on her rock, Theseus violating his oaths.

The letter writer describes many states :

" L'Amour m'est témoin que votre absence a été la plus sensible de mes douleurs et que j'ai été occupée de vous en ce triste état avec autant de vivacité que dans des moments plus heureux. " (L. LXV, p. 228.)

We find the same state of saturation by desire lacking the absent, with the emergence of a new category, of " moments ".

" In what state did I beg you not to leave ! " (LXVII, 229.)

" I must not fear to let you see there the sad state to which my heart and my health are reduced " (LXXII, 232)

Taken separately, Anne Ferrand's Lettres galantes bear many similarities to Crébillon's Lettres de la Marquise . But the book printed in 1691 did not foresee this separation the letters are published as an appendix to the novel. The exclusion of the event, like the exclusion of the other's voice, are all relative.

V. The elegiac interference: Les Lettres de la Marquise

The originality of the Lettres de la Marquise in relation to the Lettres galantes lies in their existence independently of any novel. Even the Lettres portugaises are after-the-fact letters, presupposing a love story, which they take after. Since Ovid, this has been the principle the elegiac lament comes after the weaving of events. We've seen that even when the text was in one voice (the heroines of Héroïdes, the narrator of Angoisses douloureuses, or that of Amours de la jeune Bélise et de Cléante), it elicited apocryphal responses (Aulus then Angelus Sabinus) or, in the course of the novel, a change on sight of narrator and point of view (Quézinstra for Hélisenne de Crenne, Tymandre for President Ferrand). Even the Lettres portugaises prompted Réponses in the very year of their publication in 1669.

Crébillon, the dissemination of the event

With Crébillon, nothing of the sort the Lettres record the Marquise's affair and the birth of sentiment right up to the heroine's death, struck down by absence and illness. The voice is unique; it doesn't come after the event to lament it, but accompanies it from birth to death. In keeping with the continuity of the genre, Crébillon proceeds by echoing, filtering and evacuating the intensity of the event. But he atomizes and disseminates the event into a succession of small facts: the Marquise's husband kissed her (letter III) ; the Marquise wasn't there when the Count came to see her the day before (letter IV) ; quarrels and missed appointments (letter VI) ; the Count's illness (letter IX) ; " surprise " of the portrait by Saint-Fer*** (letter XI) ; arrival of a rival in the Marquise's salon (letter XII) ; evening at the Marquise's mother-in-law's (letter XIX) ; new suitor for the marquise (letter XX) the count fought a duel with the marquis de C***, his unwelcome rival (letter XXI) the marquis fell in love with the count's cousin (letter XXII) ; new rival for the marquise, whom the count has dared to introduce to her (letter XXIV) we thus go from micro event to micro event until the announcement of the marquis's promotion, which forces the marquise to go abroad (letter LXV) :

" Our misfortune is all too certain, my husband's ambition plunges the dagger into my heart, he has at last obtained what he desired, and he drags me to a country /// which, however beautiful it may be, will never be anything but a barbaric country." (P. 209.)

This departure constitutes a generic event, with the difference that it is usually the lover's departure. In the Lettres portugaises, the French officer is recalled to France in the Histoire de Bélise et de Cléante, Cléante is called to the king's service in Italy.

Here we touch on what makes the Lettres de la Marquise so singular. There is a fundamental heterogeneity of the genre to whose tradition they belong : the elegiac void is always built from an eventful, narrative plenitude the collapse of the lyrical subject clings, anchors itself to the solar radiance of the desired absentee, whose image saturates the enunciative space. Crébillon does not escape this polarity, this co-presence of the two heterogeneous substances that make up the elegiac fictional world.

But he disseminates its opposites in fine fragments, in each letter : it is this dissemination, this pulverization of polarities that constitutes epistolary monody.

Epistolary monody: a one-voice dialogue?

For the expression was coined for Crébillon, for the Lettres de la Marquise, even as it could define the entire genre. In 1968, Jean Rousset published an article entitled " La Monodie épistolaire : Crébillon fils34 ", which essentially repeats the preface to his edition of the Lettres de la Marquise (Lausanne, 1965). Rousset anchors the Lettres de la Marquise in a shorter filiation, from the Lettres portugaises to the great Romantic elegies, Les Souffrances du jeune Werther by Goethe (1774) and Obermann by Sénancour (1804).

In fact, the whole article is going to consist in showing that monody is not monody. First of all, the absence of the Marquise's interlocutor, unlike that of the French officer in the Portuguese nun, or that of Cléante, to whom Bélise writes in Anne Ferrand's Lettres galantes, is only a brief and close absence. The comte is almost there. The marquise saw the count the day before35 ; through a bill, she arranges an appointment for the next day, for the very same day36. Rousset concludes that there is a dialogue underlying the monody:

." in the Lettres de la Marquise, the monologue is only apparent, it is the visible face of a dialogue whose other face remains hidden this dialogue exists, the exchange is real this time, the two partners communicate, meet, see each other face to face, but we are only given part of the case, we only read the young woman's letters. [We are witness to a duet in which we hear only one voice; the game is played by two characters, and we see only one of them on stage.This text is important because it provides a kind of vulgate for the modern interpretation of the Lettres de la Marquise. It is from this schema that the analysis of a rhetoric of passion and the model of what has been called, elsewhere, a one-voice dialogue37 is then developed.

The elegiac device: interference versus exchange

But this model does not correspond to the reality of the elegiac device, which is fundamentally not based on exchange (epistolary correspondence), but on interference (an impossible, prevented, hindered address). It's not a game for two that's being played out before us, but for three, at every moment, and has been for a long time in the tradition of the genre, at least since Hélisenne de Crenne : in the Lettres de la Marquise, there's the marquise and the /// count, of course, but what fuels the letter is the interference of a third character, often the husband, the marquis, sometimes a rival of the marquise, when the latter is not stirring up a suitor against the count.

Because interference takes precedence over exchange, there is no dialogue, because there is no possible reversion of point of view : the lyric subject, in Crébillon as since Ovid, is defined as a collapsed state, that is, it is not an object. Between a crossed-out subject and a crossed-out object, there is no possible exchange : proximity is a lure, which the accumulation of letters will progressively bring to light.

L'état de la marquise: logic of elegiac collapse

At letter V, the marquise writes:

" May I, examining my present state, indulge in the feelings you would like to inspire ? " (P. 58.)She defines herself as the empty space of the " present state " that the feelings inspired by the Count, that the Count's desire could come to fill. The state is an impersonal interface, created within the Marquise for the Count to inhabit. Thus, in letter VI :

" Let us speak of nothing, I pray you, until I can make you a fixed state in my heart " (p. 61-62).This state settles at the boundary between the marquise and the count, it is the locus of epistolary monody, or rather the locus on which the elegiac device is built. In letter IX, for example, while the Count is ill:

It's the place where he's going to write.

" You I don't like ! How hard that word seems to me ! [...] You've said it to me so many times, so gracefully, so tenderly what's the harm in repeating it, especially in the state you're in ? What use can you make of this word ? " (P. 66.)There is no exchange : there are only uses of discourse within an emptied space, which the marquise designates as state. In letter X, Saint-Fer*** comes to complain about " the state to which he claims I reduce you " (p. 68).

Little by little, however, this state will become fixed as the Marquise's state. Thus, at the end of letter XIII :

" Find yourself tomorrow at nine in the morning in the garden of... perhaps I'll go there. Forgive me this doubt, I am in a state of uncertainty and pain, where you could not see me without pity. " (P. 77.)In a first analysis, the Marquise sets a rendezvous with the Count, they are going to see each other, she organizes the exchange : in fact the text contrasts the garden of the rendezvous with the " state of uncertainty and pain ", place versus non-place, plenitude of reality and the fulfillment of desires versus elegiac emptiness and invisible pain : " you could not see me without pity " ; the letter responds to the request for an appointment arrangement to see each other38 by evoking this offended vision, pity blocking the view. There is thus a discursive structure to the exchange (you ask me for an appointment, here's my answer), a surface of discourse polarized by request and response, desire and satisfaction but this surface, this structure is contradicted by the depth of the elegiac device, centered on another polarity, of the visible and the invisible : the device sets up and exploits a state ; here is the emptiness of my state, here, in this state, this situation, this occasion (sliding from subject to event), is what interferes, what prevents us from seeing each other.

The garden of visibilities is then opposed to the state we can't see, just as in the Lettres portugaises the theatrical balcony of the first view was opposed to the cloister chamber, to the non-place of lyrical collapse. Underneath the lure, the bait, the trompe-l'œil of exchange, it's this depression that unfolds, /// depression of space, of the subject, of visibilities.

This lure is particularly noticeable at the end of letter XVIII. Of course, this letter is situated between two appointments and, evoking one in order to program the other, it seems to fit into a structure of exchange :

" Farewell, it's been two days since I saw you, and there was no need to write to me to say so many disparaging things. Come this evening, I'd be very happy to have an explanation with you. " (P. 87.)Beware, however, that this exchange is denied : " there was no need to write to me ". Even in such a short time, what counts is the elegiac lament over absence :

" Your heart is no longer mine, your assiduity diminishes, and you still see me from time to time only to make me feel more painfully the torments your absence causes me. " (Pp. 86-87.)This is the space of the elegiac void, where subjects unravel in the painful saturation of desire for the absent. The Count breaks down into " votre cœur ", " votre assiduité ", while the Marquise retracts into fragments of subjective interiority : " J'en crois aussi mes mouvements secrets " (p.87), she writes; she identifies with these movements, she is no longer one, but this constellation of movements, scattered throughout the " babil bien extraordinaire " of the letter. The speech misses its effect, fails to respond to the request, because the marquise's disseminated state prevents it :

" I'm not in a loving mood today, and I would perhaps tell you too coldly what you deserve me to tell you well. It is not however by caprice, but I do not find myself pretty, boredom has made me considerably ugly, and I cannot bring myself to believe that in this state you would be under any obligation to me for my tenderness. " (Letter XIX, p. 88.)There is no desirable state in the elegiac device : the discourse desires and the state prevents it. Even at the moment of amorous consummation, or when this consummation is almost acquired, the state of jouissance in which the marquise finds herself is a state of impediment :

The discourse desires and the state prevents it.

" My bewildered eyes, even looking at you, could no longer see you. I was in that state of stupidity where one lets everything be undertaken, and my reflections had given way to an intoxication, easier to feel than to express: what would I have become, if the Marquis had not arrived! I postpone your loss by one day. What do I know ? perhaps for ever ? the state in which I saw myself, whatever disorder it brings to the senses, however enchanting it may be, is too much to be feared for me not to seek to no longer find myself there. " (Lettre XXVIII, p. 106.)The state is a loss of capacity: it makes one stupid, that is, it petrifies and blocks exchange. The marquise no longer sees the count, but sees herself as stupid (" ne voyaient vous plus " / " où je me suis vue ") : the elegiac state is self-reflexive ; it's the state of Valéry's young Parque, where " je me voyais me voir "39, but reversed from plenitude into abyss, into anguish of absolute self-possession.

Abomination of the state

In the second part of Lettres de la Marquise, we witness a reversal of situation : the upward dynamic of the encounter, which made each letter the account of a past visit, the preparation of a future rendezvous, is succeeded by the vertigo of separation, doubt, absence, i.e. the very core of the elegiac device. The marquise's deplorable state becomes the depressive center of the elegiac complaint, exerting its pressure on the absent person, whom it guilts into a state of guilt by conjuring him to /// coming soon:

" Never have I loved you more tenderly ; but it is by the very love I have for you, that I beseech you to forget me. Ah, it will be all too easy for you. In the state I'm in, shouldn't you be consoling me? Have you lost all human feelings for me? You must have no doubt that I'm overwhelmed by the cruellest pain, and you stay away from me! Ah ! don't let me see all my misfortune : let me at least flatter myself that you are losing me with some regret. With so much love, do I deserve so much indifference ? " (Lettre LII, p. 177.)The state of the Marquise, who believes she has just learned that her lover is about to marry Mlle de la S***, should arouse the Count's pity, the depression of the forsaken exerting its attraction on the absent. The state introduces a logic of tropism: I'm repulsive, so I must attract you. A perverse logic, at the antipodes of seduction do we attract a lover, do we reverse indifference by appealing to " feelings of humanity ". Seduction is the structure of discourse, perverted by the prodondeur of interference, of repulsion of the state, of that elegiac state where the subject never stops collapsing, trying to drag with him, from his perverse tropism, and by the spectacle of his abomination, the fascinated absent.

" Is a letter enough ? and in the situation I'm in, would it be too much of yourself to calm my worries ? What are you doing away from me? You think I'm being unfaithful, and I'm afraid you're being treacherous. Should we be at peace with these ideas and if you still had any interest in my heart, wouldn't you have come to convince me of my infidelity, or enjoy with me the pleasure of finding me constant ? Have pity on the state I'm in, deign, and this is the only thing I require of you, deign to reassure me of my fears, and clarify your suspicions. Let me know if I should still love you, or think of hating you forever."(End of letter LIII.)On one side the letter's discourse, indifferent, insufficient, perfidious perhaps, a pale substitute for presence, immediately denounced on the other the marquise's state, which only the lover's presence could reassure. The state is an abyss, a call to be filled by a presence, and at the same time one that no presence can fill. Even when the false news of the Count's marriage is denied and the anxiety dispelled, the Marquise's state continues to exert its attraction of abomination :

" When you would have abandoned me, could I have complained ? you would only have obeyed me, but you knew what it cost me to beg you; you were touched by the fatal state to which the fear of losing you had already reduced me. Try not to repent..." (Letter LIV.)Funny, the state is what programs the Marquise's inescapable death within the elegiac device. Her state is always already what she has been reduced to: it is a reduction of self, a collapse of self upon self. The state interferes with speech: it costs her to beg the Count, she can barely express the fear of losing him, her very complaint cannot legitimately escape her retreat. The state becomes pure interference, plunged into inaudible invisibility, the marquise struggling with herself not to close in on her state :

" By my last letter I begged you to see me no more, I felt that your sight would foster feelings in me that it is important for me to extinguish ; but in the cruel state you have reduced me to, the most awful of my misfortunes is not to see you. I no longer ask you for tenderness but I have not deserved your reluctance to see me. Don't be afraid that I'll reproach you, I know how useless it would be I complain more about myself than about you. /// de vous. " (Letter LVIII, p. .)At the final stage, the state ceases to be a call to the other and closes in on itself. The Marquise then struggles with herself in a last, vain effort to prevent this closing in : but already she can no longer formulate her request to see the Count. The whole speech is organized around this dead request : " je vous ai prié de ne plus me voir ", in the past tense, means that this prayer is no longer appropriate ; the " mais " that introduces the second part of the sentence should introduce the request for a rendezvous, but the state immediately interferes (" mais dans le cruel état où vous m'avez réduite "), reducing the request to elegiac complaint, which assumes it without expressing it : " le plus affreux de mes malheurs est de ne vous voir pas ". To say that one suffers from not seeing the other is not exactly to say that one would like to see him the suffering caused by absence refers to elegiac depression and the device that develops from this depressive space, while the expression of the desire to see structures a demand, a discourse. Precisely, the request dies: " I no longer ask you for tenderness ". Only the complaint remains: " but I have not deserved the repugnance you have to see me ". It's the pain of seeing the other's gaze extinguish desire, turning it into repugnance, reversing the tropism of attraction into repulsion. This is a logic of interference, where the state interferes with desire, and not a logic of exchange, which would imply the existence of an otherness. Yet the elegiac complaint itself withdraws into itself, no longer aimed at the other: " I complain more about myself than about you ".

The last expression of the desire to see is only to rid oneself of this desire :

" Have pity on the state I'm in, I only want to see you, I won't be alone, accustom me insensibly to losing you forever : tell me everything that can confirm my misfortune, it would be too much cruelty to spare me. " (End of letter LVIII, p. 190.)We find here the masochistic device of the Portuguese nun's discourse : the exercise of pity would consist, according to the Marquise, in not showing it. One last time, she expresses the desire to see the Count, but drowns this desire in her denial : " je ne veux que ", " je ne sera point seul ", and it's to " vous perdre toujours ".

Finally, in the last letter, the Marquise's condition has completed its work of interference. The desire to see the Count has been extinguished, the verbal exchange is no longer even the horizon, or surface, of the elegiac device, whose collapse is complete :

" Isn't death itself painful enough, and would you by your presence increase the horrors of mine ? Believe me, this fatal spectacle would be too awful for you, you would not see me yourself, without dying, in such a deplorable state : avoid an image that would only embitter your despair, and leave me, in these last torments, to bear all the weight alone. " (Letter LXIX.)The epistolary monody is thus really a monody, in which exchange, correspondence are but a lure. The interior space described by this monody, the state of the marquise, has programmed its collapse since the beginning of the Lettres. What this space essentially organizes is interference, tropism, between fascination and abomination. Interference constitutes the depth, the infrastructure of Crebillonian discourse.

This discourse thus functions as a lure. But an extremely brilliant lure. What the elegiac device teaches us about this discourse is not to take it at face value. Crebillon's discourse is a meta-discourse, a /// hyperstructure : we will study this hyperstructure through the complex relationship that Crébillon, in the Lettres de la Marquise, has with marivaudage.

Notes

The first Moralized Ovid is an anonymous poem from the early 14th century. It contains large insertions from the Heroids (XII, 112-361 and 372-737).

See Marylène Possamai-Pérez's well-documented lecture, " Ovide au moyen âge ", Nov. 13, 2008, halshs-00379427.

Dorat, while believing in the authenticity of these letters, nevertheless writes Mariamne, who is a heroine of tragedy (Hardy, Voltaire) : she is Herod's wife, driven to the rack by him for having scorned him (Flavius Josephus).

, 65, 1953.

After its first performance in 1670, Bérénice, which Jean Sgard evokes, was performed twenty times between 1680 and 1685 at the Hôtel Guénégaud theater. Only two performances followed, one in 1709 at Versailles, the other in 1717 at the Théâtre des Fossés-Saint-Germain, before its resurrection in 1789-1790 at the Théâtre de la Nation. In other words, the play was all but forgotten in the 18th century.

It's above all Andromaque that eighteenth-century stages love: 1701 (six times), 1702 (six times), 1703 (twice), 1711, 1712, 1719 (twice), 1724, 1725, 1728, 1730 (twice), 1731, 1732 (twice), 1733 (twice), 1734, 1736, 1738, 1739 (twice), 1747, 1753, 1776... and so on. Same success for Iphigénie (34 performances between 1701 and 1737) not matched by Mithridate, Britannicus, Athalie or even Phèdre (23 performances /// between 1701 and 1737). Yet Andromaque, like Iphigénie, are Trojan plays, the most Ovidian of Racine's tragedies.

, n°2, Université Laval, Québec.

///1Among the first printed editions of the Héroïdes, we can mention P. Ovidii Nasonis Heroidum liber, Milan, J. de Marliano, 1478 ; Publii Ovidii Nasonis Heroides, cum commentario Antonii Volsci, Venice, B. de Tortis, 1481 (numerous reprints) ; Publii Ovidii Nasonis Heroidum epistolae, Auli Sabini Epistolae tres, Venice, with dedicatory epistle by publisher Aldus Manutius, 1502.

2incertum uigilans ac somno languida moui / Thesea prensuras semisupina manus : / nullus erat. referoque manus iterumque retempto / perque torum moueo bracchia : nullus erat. / excussere metus somnum ; conterrita surgo / membraque sunt uiduo praecipitata toro. / protinus adductis sonuerunt pectora palmis / utque erat e somno turbida, rupta coma est. (Ovid, Heroids, X, 11-18.)

3quod uoci deerat, plangore replebam ; / uerbera cum uerbis mixta fuere meis. / si non audires, ut saltem cernere posses : / iactatae late signa dedere manus. (Op. cit., X, 39-42.)

4" infelix tendo trans freta lata manus ; [/ hos tibi qui superant ostendo maesta capillos ; / per lacrimas oro, quas tua facta mouent] : / flecte ratem, Theseu, uersoque relabere uento ; / si prius occidero, tu tamen ossa feres. " (X, 148-152.)

5Sic ubi fata uocant, udis abiectus in herbis / ad uada Maeandri concinit albus olor. / Nec quia te nostra sperem prece posse moueri, / alloquor : aduerso mouimus ista deo ! / sed meriti famam corpusque animumque pudicum / cum male perdiderim, perdere uerba leue est. (VII, 3-9.)

6adspicias utinam, quae sit scribentis imago ; / scribimus, et gremio Troicus ensis adest ; / perque genas lacrimae strictum labuntur in ensem, / qui iam pro lacrimis sanguine tinctus erit. [...] / nec consumpta rogis inscribar Elissa Sychaei,/ hoc tantum in tumuli marmore carmen erit: / praebuit aeneas et causam mortis et ensem./ ipsa sua Dido concidit usa manu. (VII, 187-200.)

7The Heroids were translated into the vernacular as early as the 12th century. See Luca Barbieri (ed.), Les Epistres des dames de Grece. Une version médiévale en prose française des Héroïdes d'Ovide, Paris, Champion, 2007. These French Héroïdes appear inserted in the second version of the Histoire ancienne jusqu'à César, which eliminates the biblical parts and develops the Trojan material.

8Les angoysses douloureuses qui procèdent d'amours : contenantz troys parties composées par Dame Helisenne..., Paris, D. Janot, s. d. [privilege dated Sept. 11, 1538]. New edition in 1541, and with her other works in 1543, 1551, 1560. The text was then not republished until 1968 (edition by Jérôme Vercruysse).

9The insertion of letters into the novelistic material became widespread from the 13th century onwards : these are the epistle of the dame d'Escalot /// in La Mort Artu, and the ten epistles of Tristan en prose.

10Hélisenne de Crenne, Les Angoisses douleureuses qui procèdent d'amours, ed. Jean-Philippe Beaulieu, Publications de l'université de Saint-Étienne, 2005, p. 136.

11A first reference to Dido was found, in the words of the seventh heroid, p. 64.

12The exchange of glances at the window is a topical novelistic device. Compare Marguerite de Navarre, Heptaméron (1542-1546), 3rd day, 21st short story: "Laquelle, advisant par plusieurs foys ce jeune prince à sa fenestre, en feyt advertir le bastard par sa gouvernante; lequel, après avoir bien regardé le lieu, feyt semblant de prendre fort grand plaisir de lire ung livre des Chevaliers de la Table ronde, qui estoit en la chambre du prince. And, when each one went to dinner, one of the chamber servants would let him finish reading, and lock him in the room, and tell him to keep it well. The other, who knew him to be a relative of his master, and a safe man, let him read as long as he pleased. On the other side, Rolandine came to his window, and in order to have the opportunity to stay there longer, she started to have a leg ache, and said and sighed so early that she didn't go to the ordinary ladies'. She made herself a lict all in crimson silk, and tied it to the window where she wanted to sleep alone; and when she saw that no one was there, she talked to her husband, who could speak so loudly that no one could hear them; and when he approached her, she coughed and made a sign, by which the bastard could quickly withdraw.(LP, pp. 309-310.)

13Before Métastase, we can cite la Didone by Francesco Cavalli (Venice, carnival of 1641), that of Andrea Mattioli (Bologna, April 1656), Dido and Æneas by Henry Purcell (London, 1689), Didon by Henry Desmarets (Académie royale de musique, Paris, September 1693), Dido, Königin von Carthago by Christoph Graupner (Hamburg, 1707).

14Same variety and abundance for operas with Ariadne as their subject. See Oscar George Theodore Sonneck, Catalogue of Opera Librettos Printed Before 1800, Sonneck Press, 2007.

15Gabriel Joseph de Lavergne, comte de Guilleragues (1628-1685) led a diplomatic career from 1679 as French ambassador to Constantinople. He left no works apart from these Lettres, which he never confessed to.

16New edition of the Lettres portugaises et des Réponses in 1670 ; Lettres portugaises, avec les réponses en 2 vol. in 1680 ; Italian translation in 1682 ; " last edition increased by seven letters " in 1689.

17Lettres portugaises en vers. Par Mlle d'Ol***, A Lisbonne, et se trouvent à Paris, chez N. B. Duchesne, 1759, 23 pages in-8. Actually printed in France, with tacit permission.

18The Hague and Paris, Delalain, 1770, 2nd ed. 1771, nelle ed. 1776. Dorat's verse imitation was subsequently published with the original text : 1796, 1806.

19We should point out the possible attraction of another model, that of the lettres d'Héloïse, published in 1616, then translated into /// French by Grenaille : François de Grenaille, Nouveau recueil de lettres des dames tant anciennes que modernes, 2 vols, Paris, Toussainct Quinet, 1642. See Constant J. Mews, La Voix d'Héloïse : un dialogue de deux amants, 2001, French ed., Cerf / Academic Press Fribourg, 2005.

20Only her first name, Mariane, is revealed in the text: " cesse, cesse, Mariane infortunée, de te consumer vainement " (l. 1, p. 71) ; " Je suis au désespoir, votre pauvre Mariane n'en peut plus " (l. 2, p. 77). In 1810, Boissonade, thanks to a handwritten note found in his copy of Lettres portugaises, identified her with Mariane Alcoforado (1640-1723), and her lover with Noël Bouton de Chamilly, comte de Saint-Léger, an officer who fought on Portuguese soil, under the orders of Frédéric de Schomberg, during the War of Restoration of Independence. But as early as 1715, Saint Simon, in his account of Chamilly's death, had written: " He had served as a young man in Portugal, and it was to him that these famous Lettres Portugaises were addressed by a nun he had known there, who had become crazy about him. "

21References are given in Bernard Bray and Isabelle Landy-Houillon's edition, Lettres portugaises, Lettres d'une Péruvienne et autres romans d'amour par lettres, GF Flammarion, 1983.

22Romanische Forschungen23Dorat was already drawing the parallel with Racine. Characterizing the Lettres in his " Remarques préliminaires ", he wrote: " elles respirent l'amour le plus tendre, le plus passionné, le plus généreux ; il y est peint dans toutes ses nuances, approfondi dans tous ses détails on y retrouve ses orages, ses inquiétudes, ses retours, ses résolutions d'un moment, la délicatesse de ses craintes, & l'héroïsme de ses sacrifices. Racine himself, that Painter par excellence, did not present her in more lovable, more seductive, more energetic & softer colors. What a character Mariamne ! " (ed. 1771, p. 7.)

24Jean Sgard, Crébillon fils, le libertin moraliste, Desjonquères, 2002, p. 74. Further on, he adds : " it is a question for him of reaching a literary perfection of which Racine, more than any other, gave him the idea " (p. 88)

26Philip Stewart, L'Invention du sentiment : roman et économie affective au XVIIIe siècle, Voltaire foundation, Oxford, 2010. See in particular his analysis of Racine, p. 56 :" One can topple [from one passion into its opposite], but not stop in the middle one can express the awful heartbreak, but not temper it with a synthesis. [...] The passive essence of passion [...] leads to madness ". In Crébillon, on the other hand, "the dilemma of passion is analyzed in terms that differ from the classical tragic tone. [...] Love, while remaining problematic, essentially obeys a pattern of reciprocity. " (P. 162.) Philip Stewart's historical analysis must, however, be crossed with the generic approach, marked by the competition of the novelistic and elegiac models.

27In a note in La Nouvelle Héloïse, Rousseau contrasting Racine with Molière writes: " for the former is, like all the others, full of maxims and sentences, especially in his verse pieces : But in Racine everything is sentiment, he knew how to make everyone speak for himself, and it is in this that he is truly unique among the dramatic authors of his nation. " (Rousseau, La Nouvelle Héloïse, second part, letter XVII from Saint-Preux to Julie, Gallimard, Pléiade, p. 253.)

28" So let's not talk about origin but about the instability of the symbolic function [...]. It is the drive that, here, reigns to constitute a strange space that we will name, with Plato (the Timæus, 48-53), a chora, a receptacle. [...] as I recognize my image as a sign and alter myself to signify myself, another economy takes hold. The sign represses the chora and its eternal return. Only desire will henceforth witness this 'originary' beat. " (Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror, " Approaches de l'abjection ", Seuil, Points, p. 21.) But for Kristeva, the notion of chora is linked to Byzantine theology: " Emptiness of Christ's sacrifice, but also emptiness of virginal space : proto-space, according to Nicephorus, "space without space", chôra. The patriarch uses the enigmatic Platonic term of a space before space. The body of the Virgin is chôra tôn achôrètôn, platytera tôn ouranôn, space of things without space, wider than the heavens. " (Visions capitales, RMN, " Parti pris ", p. 62, and quotes in note the same passage from the Timée.)

29If the nun is indeed Mariane Alcoforado, the scene cannot take place in Mertola, but in Béja, her hometown, and the town where her convent Notre-Dame de la Conception is located. From Béja, the nun cannot see what is happening in Mertola, 54 km away! There is, however, a monumental gateway in Béja called "Porta de Mértola", which may be opposite the supposed convent window. D'où l'on voit Mertola would be shorthand (or a translation slip if there was a Portuguese original) for d'où l'on voit la porte de Mertola.

30Relate to letter XLIII of the Lettres de la Marquise: " J'ai pour maître le plus joli pédant du monde..." (p. 141).