We'd like to ask here what "writing about painting" might mean in the context of Diderot's Salons. We'll rule out from the outset the production of a discourse taking painting to be the indirect object of an aesthetic theory, or even simply a judgment of taste. The point is not to write about painting, but, transitively, to write painting, i.e. to translate painting into writing.

Classical painting had a very special relationship with text, one that is no longer the case. The dominant model to which it is supposed to submit is of a representation that translates a text into an image. In this sense, the dominant ideological model, from the Renaissance to the end of the 18th century, is that of a paintingwritten, a painting that can be read as writing, and this goes far beyond history painting alone. To write painting, then, is first and foremost, of course, to restore the text that the image has endeavored to represent.

But of course painting almost always escapes this model, both because painting's means of expression are too different from those of the written word, and because it claims its semiological autonomy. In the image, the viewer's eye encounters what we'll call unwritten painting, i.e. something irreducible to a text that needs to be translated into an image. This unwritten painting constitutes the essential stakes in writing the Salons, the challenge that Diderot will confront: writing painting will therefore be, in a second stage, translating this unwritten painting into text, giving an account in words of what in painting has not been structured from a text.

Unwritten painting reveals the genius of painting, its intimate spring; it does not, however, necessarily designate what, in pictorial production, is genial. The starting point for unwritten painting is often the painter's failure to translate the text correctly into an image. It was Diderot who turned this failure into the spiritual mainspring of the Salons. Put at fault, painting is then caught up by the written word that judges it. Criticism of the defect repatriates in extremis unwritten painting into the field of written painting.

After a brief reminder of the general functioning of this model from which written painting is supposed to be built, we'll study a famous example from the Salon of 1767, the commentary on Lagrenée's Mercure, Hersé et Aglaure.

The stage as medium of written painting

Since the Renaissance, the doctrine of ut pictura poesis has instituted a theoretical parallelism of the arts that tends, in practice, to subjugate the pictorial arts to the textual model. It's not a question of the written word taking cultural precedence over arts deemed inferior. What is at stake is the conjuration of the biblical ban on images: the Middle Ages, to ward off this ban, resorted to theological means; from the iconoclastic quarrel was born the theory of the translatio ad prototypum, which abolishes the painted image so that the faithful, without stopping at its surface, is transported beyond it, from sensible vision to intelligible vision, the clara visio dei.

Painting as a stage

The ut pictura poesis secularizes this conjuration. Faced with painting, the viewer will stop neither at the prestiges of color, nor at the pleasure that forms can give. Beyond the painted surface, he or she will grasp the text it represents and which, through it, he or she wants to remember. Painting is a pre-text to be read as text. Populated, bathed in images, the whole of classical culture is nevertheless ordered as if there were no images: very biblically, it celebrates the Text.

The stage plays a central role in the generalization of the ut pictura poesis system: theater is the art par excellence that lies at the articulation of text and image. A scene is said; a scene is seen. In the process of reducing image to text, the scene constitutes the medium common to both, which enables modeling. It is, in the image, what immediately refers to text. We know that history painting has come to occupy a position of overwhelming dominance in the hierarchy of genres. But what is a history painting? It is not essentially, as it is too often reductively defined, a painting that deals with a historical subject, nor a painting that tells a story: it is a painting that depicts a scene. The scene in the painting gives sight to, puts on a show, the text of a theatrical scene.

The invention of perspective also plays a key role in this secular adaptation of the translatio ad prototypum. Perspective establishes depth: it translates into space, materially, the ancient mystical distance from image to prototype, from the sensible world to the intelligible world. To achieve this, it assumes that the space of representation is a space established at a distance from the viewer's eye. Between the eye and the stage, something interposes, screens and marks the boundary: Brunelleschi's mirror, Alberti's intersector. This device, originally technical, is immediately thematized in painting, which puts it in abyme: the scene itself delimits a restricted space on the canvas, around which, or behind which, a vague space is suggested from which to view the scene. But the restricted space can only be seen by breaking in, from a door ajar, from behind a bush or a curtain. Sometimes, the door, the curtain signify the break-in even if no spectator is represented.

The stage as a device

Writing painting is therefore essentially about reversing the ut pictura poesis : it's no longer simply a question, as in the rhetorical tradition of the e[kfrasi", of recreating the text of the scene that the painting unfolds before our eyes and restoring, through this text, the meaning of a written painting, but of highlighting, in the painting, what is specifically of the image, what belongs to an unwritten painting, a painting that is only of the image, only of the visual. Something in the painted composition, in the written painting, escapes the theatrical logic of textual staging. Something resists textual modeling: the failure of the painter to stage his subject? or the stroke of genius of the artist opening up, for painting, an autonomous field of representation, freed from the tutelage of text?

For Diderot, it's all one: this iconic supplement (or flaw) deconstructs the parallelism of the arts and destabilizes the pictorial scene. To account for this supplement is to write what, on canvas, belongs to unwritten painting: both to denounce the crisis of the ut pictura poesis ending and, paradoxically, by writing unwritten painting, to re-establish in extremis the parallelism, the equivalence that has just been denounced.

The description of paintings, in Diderot's Salons, seems at first glance to obey no pre-established pattern. Some paintings are dispatched in a single line, others are the subject of digressions so long that they almost constitute a work within a work. Yet if we bear in mind this parallelism of poetry and painting, to which Diderot constantly alludes, and if we take into account the immediate consequence of this parallelism, the modeling of painting as a scene (the word "scene" recurs obsessively throughout the text), we soon realize that the account of the work almost always functions as a variation on a single reading protocol:

In painting, it's first a question of identifying the "moment", the "instant" that the painter wanted to represent. This (textual) moment delimits a scene, from which the commentator identifies the "order", the "machine", thus positing the equivalence between the scene taken as the concentration of a narrative, and the scene considered as set in space, as an arrangement in a certain depth. In this way, the geometrical dimension of the performance is superimposed on its symbolic dimension, i.e., on the meaning, the theatrical stakes set by the moment. The superimposition of the "moment" and the "machine" constitutes the device of representation: the device is always double, both geometrical and symbolic.

However, the articulation of the geometrical and the symbolic is no longer automatic or transparent in the eighteenth century: it opens up an intermediate dimension, where a whole phenomenology of the gaze unfolds. In this in-between dimension, the distance of fiction and the depth of space are abolished: the eye no longer reads; it is affected by the image, which either fascinates or horrifies it. The suspension of all distance is thematized in various ways, by the identification of the gaze with a touch, by the spectator's entry into the space of the canvas, by the emergence before the eye of an incongruous, disturbing or shocking object. Desiring impulse and feeling of the sublime bring out the scopic dimension of representation, where the reverse side of the ut pictura poesis manifests itself, i.e. precisely what is written when we don't simply read, but write painting, that we write what in painting is peculiar to painting and irreducible to text.

Diderot's criticism cannot be dissociated from the emergence of this scopic dimension. The work of criticism not only calls into question the painter's choice of moment and the arrangement of figures on the canvas, or in other words "the technique" (or "the doing") and "the ideal"1. It is the very protocol of reading underpinned by this device, by this superimposition of a geometrical structure and a symbolic order, that is shaken and, in a way, overcome. The work of criticism is fully accomplished, which delimits its object, the device of classical history painting, shows its reverse side, the scopic effect of painting, and, through this deconstruction, achieves something else, this materiality of painting that provides the eye with satisfaction or displeasure, an enjoyment exceeding all discourse.

Lagrenée's Mercure, Hersé and Aglaure: stage device

In the Salon of 1767, Lagrenée exhibited a painting depicting Mercure, Hersé and Aglaure jealous of his sister.

Omitting here to define the moment of the painting, and thus to reveal the text of Ovid's Metamorphoses (II, 708-832) that is to be represented, Diderot begins without transition by describing the disposition of the characters:

"Hersé, on the left, is seated. She has her right leg extended and resting on Mercury's left knee. She is seen in profile. Mercury, seen from the front is seated in front of her, a little lower and a little more against the background. Far to the right, Aglaure, drawing aside a curtain, looks with angry, jealous eyes at her sister's happiness." (DPV XVI 134.)

By scrolling the characters from left to right, i.e. also from the front to the back of the stage, Diderot highlights first the restricted space of the stage proper, the couple formed by Hersé and Mercure, and then the vague space outside designated by the curtain pulled aside by Aglaure. Mercure is "a little further back": depth is established, allowing the screen device to be installed with its interposition system. The green curtain and the balustrade on which Mercury is seated delimit the screen of the performance, a screen that Aglaure lifts to look, by trespassing, at an intimate scene, forbidden to the gaze. According to Ovid, Aglaure occupied the first room at the back of Cecrops' palace in Athens, and Hersé the second, so that Mercury had to pass through Aglaure's room to reach Hersé's, with whom he had fallen in love3. The curtain, the balustrade and Aglaure's left hand materially represent the separation of the rooms, and symbolically the cut of desire that gnaws at the neglected sister. Aglaure is forbidden in more ways than one: she is not allowed to look; she is mortified by what she sees; she will be petrified by Mercury, who will punish her for her jealousy. This forbidden gaze metaphorizes the gaze of the spectator who, faced with the image, transgresses the biblical ban on representation. Aglaure is another of Loth's wives4.

The scopic dimension

However, what is given to look at is not, is no longer strictly speaking neither the cult of images, nor its symbolic equivalent, the practice of lust, but simply "happiness". What is at stake in representation is the expression of jouissance:

"Artists may tell you that the main figures are heavy on drawing and color, and without passages of hue. I don't know if they're right; but after reminding myself of nature, I cried out in spite of them and their judgment, O beautiful flesh, beautiful feet, beautiful arms, beautiful hands, beautiful skin; life and the incarnation of blood transpire through; I follow beneath this delicate, sensitive envelope the imperceptible, bluish course of veins and arteries. I'm talking about Hersé and Mercure. The flesh of art struggles against the flesh of nature." (Continued from previous.)

The technical reproaches that can be levelled at Lagrenée are initially warded off by the force of natural evidence, by the voluptuous appeal of the flesh.

Diderot then contrasts two views: the distanced, technical view of the "artists" will criticize the "design", the "color", the "passages of hues", in a word everything that, conventionally, must make it possible to represent "the flesh of art...". In response, Diderot invokes nature ("après m'être rappelé la nature", "les chairs de nature"). Yet these are not two points of view, or even two instances of judgment. Technique certainly opens up the geometrical distance of judgment5; but nature abolishes this distance; it impregnates things, it undoes the structure of the body whose parts it isolates, it brings about enthusiastic adherence. It's no longer a question of looking, let alone criticizing, but of feeling: the artifice of painted figures is forgotten, and the viewer participates in the life of the flesh. Just as the depth of space fades away, it is the depth of flesh that makes way for it: beneath the flesh, the blood, beneath the envelope of the skin, the veins.

These are no longer figures, they're flesh. The gaze no longer circumscribes a scene. The eye adheres to sublime membra disjecta. The object of the gaze is deconstructed, disseminated. From this very dissemination, where the gaze is lost, comes the feeling of the sublime and the scopic dimension, where the device of representation finds both its fulfillment (we have never been so close to Mercury's amorous enjoyment with Hersé) and its end (there is no longer either Mercury or Hersé, but flesh).

."Bring your hand close to the canvas, and you'll see that imitation is as strong as reality, and outweighs it in beauty of form. You'll never tire of looking at Hersé's neck, arms, throat, feet, hands and head. I put my lips to it, and I cover with kisses, all these charms." (Continued from previous.)

In the text, the moment when the scopic dimension of the image is expressed is also the moment when the distance of the gaze switches to the sensitivity of touch. "I" walk through Hersé, "I" reunite the separated parts of his body in a journey that reconstitutes the figure. His name can then return: the space emptied by the gaze is once again inhabited by sensitive communion.

Supplement and defect, principles of symbolic splitting

"I" enjoy Hersé: the spectator identifies with Mercure and no longer with Aglaure, whose point of view and gaze by effraction ordered the geometrical dimension of the scene. This time, it's a question of entering into the scenic game rather than delimiting its boundaries. "Je" comes into the scene as an extra, as something extra that designates something less, precisely Mercury's failure, this constitutive defect of jouissance:

."O Mercury, what do you do? what do you wait for? you let that thigh rest on yours, and you don't seize it, and you don't devour it? and you don't see the drunkenness of love that seizes this young innocent, and you don't add to the disorder of her soul and her senses, the disorder of her clothes; and you don't lunge at her. God of tricksters!..." (Continued from previous.)

Mercury does not respond to the call of the flesh. The image remains motionless, painting fails by nature, essentially, to produce the movement that, in its very scenic dimension, it elicits.

Mercure's interpellation gradually re-establishes the distance of speech. "I" leaves the stage. Insidiously, the spectator's identification slides further to the left. It's no longer Mercury's jouissance, but Hersé's that's in question, jouissance excited by the moment of the scene, by the god's enterprise, then frustrated in its fulfillment.

Unwritten painting: Hersé's point of view, the flip side of the device

It's not just the stillness of the painting, necessarily suspended on the threshold of narrative fulfillment. Mercury does nothing with his hands. He doesn't seize Hersé's offered thigh, he doesn't devour that appetizing flesh with his kisses, he doesn't mess up the blue drapery of her tunic wisely laid on his lap.

What's Mercury doing? Right hand on his heart, left hand open, index finger slightly stretched forward, in the position of an actor declaiming his tirade, Mercure pérore. In this, Lagrenée respects the conventions of history painting. This painting is written; it writes, on a medium other than the text, Mercury's speech: the declaration of love is the text of which this scenic device provides us with the image.

But Mercury's speech does not satisfy Hersé's jouissance. It is inscribed in the image, as a lack of action, as the skulduggery of which Mercury, god of thieves, becomes the emblem. What's revealed here is that we don't really care about the text that the image is supposed to convey. The essential can only be said under the veil of banter: Hersé's enjoyment remains unfulfilled. Beyond the anecdote, Hersé's point of view, which is one of lack, turns Aglaure's point of view on its head, introducing into the scene the additional element of a break-in. Both, in their own way, metaphorize the gaze that every painted scene programs for the spectator of the work of art in general: this gaze is solicited to enter a space where it is, by nature, impossible to enter (this is Aglaure's tragedy) and enjoy a spectacle that, by nature too, cannot satisfy the enjoyment it promises (this is Hersé's drama).

Here we touch on the fundamentals of the classical scenic device:

On the one hand, the staging of the break-in manifests the symbolic cut constitutive of the stage: space is cut off; speech is cut off. This cut covers and figures a castration, the conjuring of which constitutes one of the driving forces and stakes of aesthetic jouissance.

On the other hand, and this is less well known, faced with this economy of the cut, the scenic device brings into play, manifests a certain consubstantial defect of jouissance that has nothing to do with castration. It's a certain feeling of feminine flesh with which the gaze is identified. Diderot expresses this feminine feeling in the dream of sensitive continuity, of the impossible caress of the eye, which becomes the spectator's hand, replacing Mercury's caress, which never comes. The important thing is not for the eye to replace Mercury, but for the caress to melt into Hersé. "I" is then identified with the lack of jouissance that inhabits the woman's body and threatens to dislocate it. Another economy of jouissance is at play, a non-phallic economy, all surfaces and touches of flesh, a feminine economy of the hymen6, which is the place and means of another symbolization.

Hersé's leg, punctum of the canvas

Suddenly, then, this "enormous defect" in Hersé's leg appears on this canvas. Immediately the material distance and the symbolic distance are re-established, the distance of the gaze that delimits painting as a scene and the critical distance that turns this limit into a defect, a failure of painting. The spectator leaves behind the "transport" provided by the experience of the scopic dimension of representation. The lack of jouissance he had experienced at the end of his "transport" persists in the rediscovered space of the stage. But it manifests itself in another way. Transposed geometrically, it becomes a technical defect, a defect of order :

"I felt all these things and was transported by them, when having moved a little away from the painting, I gave a cry of pain, as if I had been struck by a violent blow. It was an error, but such a cruel error of drawing that I felt a mortal pain to see one of the best compositions of the Salon spoiled by an enormous defect. This leg of Hersé at the end of which there is such a beautiful foot, this leg stretched out and resting on the knee, on this so beautiful, so precious knee of Mercury, is four large fingers too long; so that leaving this beautiful foot in its place, and shortening this leg by its excess, there would be much missing, but much that it would not hold to the body; a defect which led to another, that in following it under the drapery, one does not know where to bring it back." (DPV XVI 135.)

Hersé's leg is not attached to his body. It floats, it undoes Hersé's body and, paradoxically, it thus signifies the lack of jouissance that constitutes it.

This "huge flaw" manifested itself as a clash, as a "violent blow". The leg abolishes the fourth wall which, in front of the foreground, delimits the scene and separates it from the spectator7. The defect penetrates the real; it ensures the junction, the communication of these two theoretically disjointed worlds, the Salon where the spectator evolves and the stage where the imitation is produced. The leg shocks; to use Roland Barthes' expression in La Chambre claire, it points me; disarticulating nature and "the technical", the leg constitutes the unpredictable randomness of the real within the culturally framed device of imitation; in this way, the "enormous defect" prefigures the punctum. The critique of painting, by revealing its defect, leaves the economy of mimesis to enter an economy of punctum.

In fact, Lagrenée's half-assed painting becomes an anthology piece for Diderot the art critic. In this piece, the leg fait tableau: we see only it. Faire tableau is not a concerted imitation of nature, modeled as a scene so that the image becomes a legible, textualized object. Making a painting is a matter of random crystallization: Diderot's eye could fixate, as well as not fixate, on this defect in the leg. This defect can make sense as a subversive reversal of the meaning of the history scene; but this defect can remain insignificant, demolishing Lagrenée without opening up to another truth of the image.

Diderot makes the leg defect the sign of a fundamental semiological shift. The imitation was centered on Mercury's speech; the punctum shifts attention to Hersé's jouissance defect, deconstructing the whole edifice that structured the painting written from a theatrical tirade, to conjure up, in Diderot's text, the virtual, floating, disquieting and parodic image of this disarticulated leg.

Diderot makes the leg defect the sign of a fundamental semiotic shift.

The choice of moment and the crisis of the ut pictura poesis

Mercury's tirade collapses, denouncing in the process the artifice, the very falsity of the chosen moment.

While Veronese, who in this had served as a model for several paintings on the same subject, had chosen to depict the moment when Mercury crosses the threshold of Hersé's chamber, passing over Aglaure's body and petrifying her with his caduceus, Lagrenée imagines a moment that does not exist in Ovid's account: Mercury is already in the room, and it's Aglaure who has the function of breaking into the restricted space of the scene, a purely visual break-in.

Veronese's moment constitutes the climax of Ovid's tale: it is the fall of the tale, the punishment of metamorphosis, beyond which there is nothing left to imagine, to make up for. The choice of a paroxysmal moment in the story corresponds to a semiology of the expression of passions, or even their emblematization: Aglaure, struck down, represents the punishment of Envy; opposite her, Hersé, a spectator, represents modesty and the regulated use of desire: seated modestly, in the background, in Veronese and in Jean-Baptiste Pierre's painting, which is directly inspired by it; more lascivious in Poussin's version, but soon covered with a veil by opportune putti.

Lagrenée prefers to this paroxysmal moment what Lessing theorizes in the Laocoon as the "pregnant instant". Mercury is already in the room: before the scene before us, he has already made a deal with Aglaure. Aglaure has not yet been punished: after the scene, when she leaves the room, there will be a metamorphosis. Caught between a narrative before and after, the moment concentrates a series of events in a single, suspended, artificial device. It's no longer a question of allegorizing the story to extract figures and fix signs, but of dramatizing the scene, imagining an unfolding. Painting now writes its own text. It invents an improbable speech by Mercury. Through this unfolding, this invention, this theatricalization, the new semiological device, based on the instant, makes the image float, opening it up to the virtualities of the imagination. In burlesque form, the floating leg pointed out by Diderot expresses this imaginary floating, symptomatic of a profound semiological transformation: the compositional flaw that escaped Lagrenée is turned by Diderot into a means of imaginary expansion, i.e. precisely into what the pregnant instant produces when it is successful.

This semiological transformation, marked by the shift from the paroxysmal moment to the pregnant instant, from trespassing through intrusion to trespassing through the gaze, doesn't simply reflect an evolution in taste and a change in aesthetic order. It's the very symbolic articulation of the image that's turned upside down: we move from a phallic economy, marked by the cut of the screen, to a non-phallic economy, where bodily dislocation places flesh at the heart of the meaning that's being called into question here. Causing "mortal pain" to the viewer, the defect designates death, like the anamorphic skull in Holbein's Ambassadors. The woman's sex becomes the new focal point where representation fails, the point from which nothing can be articulated: "il s'en manquait beaucoup"; "on ne sait où la rapporter". Mercury punishing Aglaure represented symbolic castration: Aglaure perished for having crossed out the phallus. Hersé's dislocation in the face of Mercury's speech represents the call of the female sex, the rush and fusion into it.

Witty portraits

Once the flaw has been spotted, Diderot revels in it and makes wit:

"Certainly, if Mercure only needs a thigh, he can carry this one under his arm, without Hersé being able to suspect it. Mercure's arms, neck, chest and flanks are very skilful, but you can tell he was drawn after the Pigalle statue. Here again, the painter has planted two wings on his head, which don't look any better than they do elsewhere. I thought I'd say nothing about Aglaure. She's cold, flat, petty, stiff in position, weak in color, null in expression. If you can forgive this work this small number of faults, cover it with gold on Le Moine's word." (DPV XVI 136.)

Mercury does indeed need a thigh, as he's missing one. Given the position of the bed Hersé is sitting on, as well as the stool she's putting her foot on, there's nowhere for Mercure to place her right leg.

The witticism brings in extremis the floating leg, a sign of the defect in female jouissance, back to Mercury and the traditional symbolism of castration. Hersé's excessive leg becomes Mercury's defective leg, and thus merely redoubles, on the imaginary plane, the semiotic cut represented by the constitutive screen of the classical scene. In fact, Hersé's leg explicitly bars Mercury's desire on the canvas, just as the curtain and balustrade bar Aglaure's desire, which itself metaphorizes the spectator's gaze.

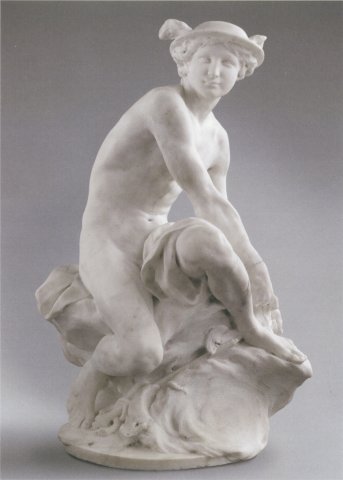

.Mercure, according to Diderot, is imitated from Jean-Baptiste Pigalle's Mercure attachant ses talonnières, his famous reception piece for the Académie in 1744. Pigalle, with Mercure's gesture, wanted to signify the speed of running, at which this god excelled. Distractedly fastening his sandal, Mercure's eyes turn towards the goal of his race. He is stopped, pulled backwards by this setback. But his body is turned forward, tense towards recovery. Sculpting movement is a challenge, and Pigalle was applauded for this tour de force.

But above all, the representation of movement in the immobile arts of the image participates in the scenic modeling imposed by the ut pictura poesis. To represent movement is to inscribe the image in a narrative linearity. If Diderot insists so much on the immobility of Lagrenée's Mercure, it's in reference to his famous model, which had become a veritable allegory of speed. Lagrenée's Mercure chatters instead of rushing. He kills the text he pronounces by the very act of pronouncing it. What's in motion is the other leg. But this movement doesn't refer to a narrative; it belongs to the symptom.

Finally, Aglaure's review concludes with a final witticism: we are therefore authorized to cover this work in gold if we agree with the judgment of Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne, with whom Diderot discussed it. This gold alludes to the reward that the greedy Aglaure had demanded from Mercury to allow him to cross her room and join Hersé:

Proque ministerio magni sibi ponderis aurum

Postulat... (II, 750-751)

And for the price of the service she demands a great weight of gold...

Aglaure never receives the gold she asked for, as Mercury impatient with her procrastination petrifies her.

To cover the painting in gold is to petrify it, i.e. to conjure in it that scopic dimension which, for a moment, had brought blood, life and the sensations of flesh to these disarticulated bodies. Similarly, in the Salon of 1763, Diderot had concluded his brief commentary on Pierre's painting, entitled Mercure amoureux qui change en pierre Aglaure qui l'éloignait de sa sœur Hersé, with these words: "Ce n'est pas Aglaure, c'est l'artiste et toute sa composition que Mercure en colère a pétrifiés." (DPV XIII 360.)

Conclusion

As an art critic, Diderot certainly obliged himself to describe the order of paintings. When he makes the characters speak, when he animates the "moment" of the scene, he takes to the extreme what constitutes the normal protocol, forged by the tradition of ut pictura poesis, of reading painting.

But the greatest originality of the Salons could lie elsewhere, in the exploitation of painting's defects. The defect ensures a passage, a communication between the experience of the scopic dimension of the gaze and the critique of the scenic model of painting. Scopic fascination or horror then ceases to constitute the fleeting moment of transition between the two dimensions, geometric and symbolic, of the device.

The uncertain trial of the defect of feminine jouissance is perpetuated, objectified in the designation of a technical defect. Writing painting then consists, for Diderot, in writing the defect in painting. The critic reveals the reverse side of history painting, highlighting what in painting escapes textual modeling. To write painting is to move from the old written painting, which was read as text, to an unwritten painting where the experience of the defect of jouissance abolishes the mimetic frontier between the real and its representation.

Notes

.See S. Lojkine, "De l'écran classique à l'écran sensible : le Salon de 1767 de Diderot", L'Écran de la représentation, l'Harmattan, coll. " Champ visuel ", 2001, pp. 295-308.

On the layout of the rooms, see v. 737-739.

See S. Lojkine, "Une sémiologie du décalage : Loth à la scène", La Scène, littérature et arts visuels, textes réunis pas M. Th. Mathet, L'Harmattan, 2001.

In the first part of this presentation, we defined the geometrical dimension of the device as the establishment of respective distances between objects and characters so as to establish the illusion of perspective and depth necessary for the establishment of a scene. This geometrical, rationalized, mathematized distance is opposed to the scopic relationship to the object, where fascination and abjection manifest themselves in an unstable, distance-free way. For this reason, the distance between the spectator and the scene that the geometrical dimension of the device establishes prepares, on a symbolic level, the distance of judgment.

On the hymen, see S. Lojkine, "Representing Julie: the curtain, the veil, the screen", L'Écran de la représentation, op. cit.

See Diderot, Paradoxe sur le comédien, A. Colin, 1992, introduction, p. 59sq.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « La Jambe d’Hersé : Écriture de l’image et cristallisation scopique dans les Salons de Diderot », Écrire la peinture entre XVIIIe et XIXe siècles, dir. P. Auraix-Jonchière, Presses universitaires Blaise Pascal, 2003, p. 75-92.

Diderot

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Diderot

Les Salons

L'institution des Salons

Peindre la scène : Diderot au Salon (année 2022)

Les Salons de Diderot, de l’ekphrasis au journal

Décrire l’image : Genèse de la critique d’art dans les Salons de Diderot

Le problème de la description dans les Salons de Diderot

La Russie de Leprince vue par Diderot

La jambe d’Hersé

De la figure à l’image

Les Essais sur la peinture

Atteinte et révolte : l'Antre de Platon

Les Salons de Diderot, ou la rhétorique détournée

Le technique contre l’idéal

Le prédicateur et le cadavre

Le commerce de la peinture dans les Salons de Diderot

Le modèle contre l'allégorie

Diderot, le goût de l’art

Peindre en philosophe

« Dans le moment qui précède l'explosion… »

Le goût de Diderot : une expérience du seuil

L'Œil révolté - La relation esthétique

S'agit-il d'une scène ? La Chaste Suzanne de Vanloo

Quand Diderot fait l'histoire d'une scène de genre

Diderot philosophe

Diderot, les premières années

Diderot, une pensée par l’image

Beauté aveugle et monstruosité sensible

La Lettre sur les sourds aux origines de la pensée

L’Encyclopédie, édition et subversion

Le décentrement matérialiste du champ des connaissances dans l’Encyclopédie

Le matérialisme biologique du Rêve de D'Alembert

Matérialisme et modélisation scientifique dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Incompréhensible et brutalité dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Discours du maître, image du bouffon, dispositif du dialogue

Du détachement à la révolte

Imagination chimique et poétique de l’après-texte

« Et l'auteur anonyme n'est pas un lâche… »

Histoire, procédure, vicissitude

Le temps comme refus de la refiguration

Sauver l'événement : Diderot, Ricœur, Derrida

Théâtre, roman, contes

La scène au salon : Le Fils naturel

Dispositif du Paradoxe

Dépréciation de la décoration : De la Poésie dramatique (1758)

Le Fils naturel, de la tragédie de l’inceste à l’imaginaire du continu

Parole, jouissance, révolte

La scène absente

Suzanne refuse de prononcer ses vœux

Gessner avec Diderot : les trois similitudes