" - You can see that the fear is all in your head, Anastasia. (He's silent for a moment.) Would you do it again ?

I think for a moment despite my fatigue-fogged brain... Again ?

- Yes.

My voice is so soft " (CNG XVIII 427, FSG 3251)

" It goes even further. It's not a sufficient answer either, because love asks for love. It doesn't stop asking for it, it asks for it... again . Again, it's the proper name of this fault from which in the Other the demand for love departs. " (Lacan, Encore, p. 112)

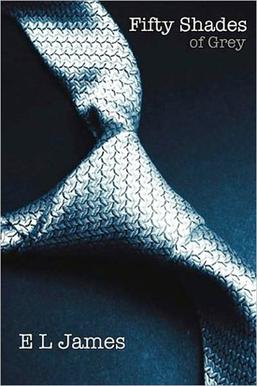

My purpose here will not be to discuss the literary quality of this novel : it is not for its literary quality that one reads this kind of literature. Nor will it be my intention to discuss its moral, ideological, sociological impropriety : it is precisely for its impropriety and vulgarity that this kind of literature is read. My intention, on the other hand, is to rely on its apparently convenient character: the stereotypes it agencies, and the huge audience that the book and then the film have conquered make Fifty Sades of Grey a phenomenon, a symptom of society, which questions us precisely at the crossroads of literature and psychoanalysis.

If Fifty Shades of Grey isn't exactly a literary work in the academic, French sense of the term, it feeds on literature : its heroine, Anastasia Steel is a literature student, completing a master's thesis on Thomas Hardy's Tess d'Urberville (CNG I 35). When she first meets Christian Grey, whom she is supposed to interview for the university's student newspaper, he turns the interrogation around and asks her:

" - And what's your thing, Anastasia ? he asks me in a soft voice, again with his "secret" smile.

No sound comes out of my mouth. No sound leaves my mouth. I'm teetering on shifting tectonic plates. Calm down, Ana, my conscience begs on its knees.

-The books. I whisper, but my conscience screams : You ! You're my thing ! I slap her shut, appalled by her delusions of grandeur.

-What kind of books? He tilts his head over his shoulder. Why does it interest him ?

Well, you know, like everyone else. The classics. Especially English literature" (CNG, II 44-45)

In English, the question is " What is your thing, Anastasia? " (FSG II 28), echoing Ana's mother's late husband Bob's question, " How are things with you, Ana " (FSG II 22). The rearrangement of terms transforms the expression of banal solicitude into an inquisition bordering on perversity. What's at stake is Ana's relationship to the Thing; she's asked how Things behave with her, then what her Thing is, with which Thing she has a privileged relationship. The Thing, the thing, das Ding, it's Ana's reality, her environment, the things in her life ; and the Thing at the same time, it's what she has elevated to the dignity of the Thing, it's what through which a sublimation is possible, and a symbolic order takes shape.

Ana brings to Christian Grey's question a double answer: his thing is books, literature, the literary field as a space from which to think about reality. And his thing is Christian Grey, You! You are my thing! : Christian Grey is the only possible object of her desire, an impossible desire, and above all one incompatible with literature.

This desire isn't just repressed. It clashes with a secret : facing Ana, Christian opposes the smooth surface of an enigmatic smile : his secret smile is back. I gaze at him, unable to express myself. On one side the screen of the smile shelters Christian Grey's secret on the other, Ana's devouring gaze blocks and paralyzes his speech.

The object of the novel is this double knot of speech, shown on the cover by the knot of the elegant gray tie, perfectly tied on a black background, meaning that it catches no body, no figure. There is only the knot, the knot of the Lacanian signifying chain, catching the black of the symptom from the RSI triangle thus formed, of the real, the symbolic and the imaginary.

The secret at stake is Christian Grey's perversion, a perversion confronted with Anastasia Steele's literary analysis. Mr. Grey is also a formidable businessman, and the embodiment of triumphant capitalism. We'll come back to this combination of disturbing, abject sadomasochistic perversion and the incredible seductive power of the capitalist fantasy embodied by the gray-suited supermodel. At this stage of the analysis, it's necessary to reiterate our threefold methodological position : the literary quality of the figure emerging before us is not our object nor is its moral appropriateness and the appropriateness of the character can only alert us a little more to the obviousness of the symptom manifested here. For now, let's confine ourselves to noting that the Grey figurine (less a fictional figure than a play figure, more a manipulable fantasy of manipulation) is characterized by its secrecy. The secret is psychoanalytical3 and, in a way, the novel is a case study. The scene that the perverse figure tirelessly intends to replay in the room devoted to his fantasy constitutes the obsessive repetition of a screen scene behind which it is a question of restoring a traumatic cause, the primitive scene experienced by the martyred child that Christian Grey was first, before being adopted by his wealthy Seattle parents.

.

I. Love and pleasure

Let's start by naively playing the fiction game, as if the figurine were a subject.

What Christian Grey is enacting, through the repetition he indulges in, is jouissance. What Anastasia Steele demands, through the negotiation she engages in with Christian Grey, is love. Christian is the psychoanalytic hero of the novel, his work of darkness a work of jouissance. Ana is the novel's literary heroine, aiming for a literary object, she writes, in the first person, her love story.

Making love and kissing

The whole novel rests on the tension between these two contradictory and asymmetrical demands. Ana asks for love, but receives pleasure. Christian gives pleasure, but refuses love:

The whole novel hinges on the tension between these two contradictory, asymmetrical demands.

" - So, you're going to make love to me tonight, Christian ?

Shit, did I really say that ? His mouth drops open slightly, but he recovers quickly. -No, Anastasia. First of all, I don't make love. I fuck... brutally (I dont'make love. I fuck... hard). Second, there are still papers to sign. And third, you don't yet know what you're committing to. When you do, you'll be running for your life. Come on, I'll show you my playroom. [My mouth drops open (My mouth drops open)4.] Rough sex ? Holy shit, what is that... pig5 (that sounds so... hot). " (CNG VI 136-137 ; FSG 96)

Once again, two stupefactions, two loopings of speech face each other : His mouth drops open slightly has its counterpart My mouth drops open. Christian doesn't expect Ana to speak so bluntly to him (you're going to make love to me) baffled, he outbids her by speaking even more bluntly (I dont'make love. I fuck... hard6). The essence of this one-upmanship is not its coarseness or vulgarity (" it's... dirty "), but the sexual excitement it produces (so... hot), i.e. the jouissance it promises.

Here we touch on an essential configuration of the device. Christian's unceasingly reaffirmed aim is to get Ana to accept the masochistic contract she has to sign. He will provide her with enjoyment in return for this contract, and according to the terms and limits it prescribes. This contract is negotiable, and so on the surface it's Christian Grey, the virile, economically and sexually overpowered subject, who leads the negotiation. In reality, Christian is constantly baffled by his project7. Here, for example, Ana's direct and brutal question catches him off guard, forcing him to name directly the object of jouissance that, according to a typically perverse logic, Christian always keeps veiled, at a distance, substituting for it the instruments and procedures of sado-masochistic jouissance, the discussion of these procedures, the presentation of the place of secrecy (the playroom). Christian seems to be outbid, when he switches from make love to me, where love is committed, to fuck hard, which designates brutal, crude jouissance, and expresses the sexual act even more directly. In reality, however, make love to medesignates the object, advances uncovered towards an Other who is named, to me, while fuck is used intransitively, without object, as a perverse recession, which manifests a solipsistic retreat of the subject8.

The subject of jouissance, Christian, is therefore also an abject subject, a subject without object relations, while the subject of love, Ana, remains suspended from her own object demand, exists only through this demand. Ana is the subject of demand through which alone Christian Grey exists : she is for him the suspended possibility of an object of desire, she is the one he is tempted to love, whom he could love if he abandoned the sado-masochistic system in which he is caught and chose her as the object of his desire.

Ana is the novel's lyrical subject, and as narrator the introspective subject : but paradoxically she is not, or is only marginally, the object of analysis. Ana is not an analytic subject; she is not the one whose analysis is being conducted. Conversely, if Christian is indeed the novel's analytic subject, his sado-masochistic system, which seems to define him, has virtually no real consistency. All Christian's acts, all the essential episodes, consist in departing from this system of jouissance and entering into the logic of love. Ana should negotiate, but it's Christian who deviates. Ana should renounce love, but Christian is always drawn back into it.

So, when he learns that she's a virgin :

" We'll rectify the situation immediately.

- What do you mean by that ? What situation ?

-Your situation. Ana, I'm going to make love to you now. -Oh! The ground just collapsed beneath my feet. I'm holding my breath.

- If you consent. I don't want to impose anything from you.

-I thought you didn't make love? That you fucked brutally? I swallowed. Suddenly, my mouth is dry.

He gives me a naughty smile, the effects of which are felt right up to there.

- I can make an exception, or combine the two, we'll see. I really want to make love to you." " (CNG VIII 155 ; FSG 110)

In English, situation is understood in two senses as situation and problem : there's the characters' situation, which literarily commands the scene to come ; and there's Ana's problem, her virginity, which analytically blocks the execution of the sado-masochistic fantasy. Ana is a situation, i.e. she's not a subject : the moment Christian Grey offers to make love to her in due form, he denies her the status that would enable him to initiate an object relationship with her. Christian makes an exception to his self-imposed rule of sadistic repetition, but he does so in order to rectify a situation, to bring reality back precisely to a situation within the rules, to the system of rules from which he does not intend to depart. Making love becomes a rectification protocol.

Making love is fucking

And this is where the novel reveals its extraordinary power of effectiveness : this protocol, Christian pulls off extremely well. This artifact of love is absolutely perfect, superior even. It is not only superior it marks the marvelous fulfillment of the world system we live in, of its fundamentally procolar organization9, and of the perverse, sado-masochistic substratum of this organization. It speaks of the collapse of the contemporary subject confronted with this pulsional device10 that organizes post-modern capitalism, and its extraordinary efficiency in liberating and procuring jouissance. But it also speaks of the last resistance to generalized protocol, which is the resistance of love. Christian Grey does better than love, he does even love, he's a remarkable expert in its artifacts, but he misunderstands love, he doesn't essentially access love, what's essential in love, and he can't satisfy Ana's demand for love, that imperious demand she sovereignly formulates, however ugly, however introverted, however literary.

The day after her first night of love at Christian Grey's, Ana prepares breakfast in the rich bachelor's luxury kitchen :

" I came to spend the night with Christian Grey and got there, when he won't let anyone sleep in his bed. I smile : mission accomplished. His words, his body, the way he makes love to me... I close my eyes, purring, as my muscles clench deliciously in the pit of my stomach. My conscience glares at me. He didn't make love to you, he fucked you, she screams at me, that filth [My subconscious scowls at me... Fucking - not lovemaking, she screams at me like a harpy11]. Deep down, I know she's right, but I shake my head to chase that thought away and focus on my task.

[There's an array of the latest utensils. I think I know how to use them. I need a place to keep the pancakes warm, and12 There is a state-of-the-art range. I think I have the hang of it. I need somewhere to keep the pancakes warm, and] I start cooking the bacon." (CNG IX 177, FSG 127)

The novel thus expresses explicitly that the dichotomy on which it rests, between love and enjoyment, reduced to the trivial opposition between making love and fucking, is a lure : making love is fucking, here both verbs command an object, and both formulas are formulas of brutality and contempt. The voice in Ana that formulates the observation and reproach is not, as Denyse Beaulieu translates it, the voice of conscience (consciousness, conscience) but the voice of the subconscious (subconscious), which is neither the Freudian unconscious nor the conscience of the Cartesian subject, but rather here the superego. This distinction is important, because this imperiously judging voice doesn't motivate its judgment : the motive is a principle as brutal and vulgar as it is powerful, a kind of reality principle of jouissance, " He didn't make love to you, he fucked you " ; Ana's subconscious , which seems to lecture her, above all enunciates the spring of phallic jouissance. This spring, this principle, is in Ana, not in Christian.

The other jouissance

Anna's superego reproaches her for the jouissance Christian has given her, as pure jouissance without love. There would therefore be another jouissance, one to which Christian has not surrendered, has not lent himself, another satisfaction that he alone could deliver but of which he himself does not hold the secret. He formulates many approximations : it's vanilla sex, for example, " sex tout bêtement " 13, that foolishness of love that Lacan identifies with the angelic smile14 and which Ana embodies, the eternally clumsy, clumsy and naive15.

Without this approval, the jouissance experienced by Ana, which is only Christian's jouissance, phallic jouissance, remains an incomplete jouissance. Ana, who has enjoyed Christian, has enjoyed him at the reserve in him of her secret : a reserve in Christian has not been enjoyed ; he has remained, in jouissance, not-all, precisely in this sacramental night when, losing her virginity to rectify the situation, she has given all of herself, she has become fully woman, she has fully entered the economy of desire in which the negotiation engages.

The narrator then returns to breakfast : Ana has finished preparing the pancakes, and begins to toast the bacon. The kitchen metaphorizes the cleavage of being : there's a side for pancakes and a side for bacon. One side is reserved for the elaborate preparation of pancakes, which requires a mastery of kitchen utensils, knowledge and technique another side is devoted to the still-raw pork fat that is grilled, to the gourmet heaviness of bacon flesh. Wheat and pork, cooked and raw, reproduce and imagine the two jouissances, the secret one we reserve (and which the translator cuts) and the obvie one we brutally expose.

From Ana's inner speech to the preparation of breakfast, the link is made by comparing the superego to a harpy (which also disappears from the translation) : a female bird of vengeance, her cheeks hollowed out by hunger, the harpy devours everything in its path, and promptly rejects vile excrement16. It is both the voice of guilty conscience and the brutal appetite for jouissance, jouissance and its condemnation, in other words the very system of double jouissance and its devouring metaphor, which will then be translated, quite innocently, into the preparation and consumption of breakfast.

Anna's superego is a harpy, and Christian is obsessed with food17 : he forces Ana to eat, to finish her plate, her dish, to exhaust the abundance of the table, beyond satiety and to the point of disgust the harpy is Christian's abject flip side at the same time as Ana's superego.

So there's a part of Ana that protests against Christian Grey's jouissance (against Christian enjoying her and against the jouissance Ana derives from him, the genitive is always both subjective and objective). But this part that hungers, devours and sullies food with excrement, i.e. jouissance itself, is Christian Grey, it is the device he embodies and implements of the reduction of love to the negotiation of the contract of sado-masochistic defilement.

II. The contract

Sado-masochistic contract and marriage contract

What defines the contract Christian Grey would like Ana to sign is, first of all, its uncanny, antiquated resemblance to marriage vows :

" To serve and obey in all things. In all things ! I shake my head. I just can't believe it. By the way, don't wedding vows include that word... obey ? I'm still puzzled. Do couples still say that when they get married (Do couples still say that) ? [...]

And I won't be allowed to touch it. That doesn't surprise me. But all these silly rules... No, no, I'll never make it. I hold my head in my hands. This is no way to have a relationship" (CNG XI 239, FSG 175-6)

The English here doesn't say love but relationship. It's not that there is no love ; there is no relationship18. The contract doesn't codify a couple's relationship (Do couples...), it sets protocols for behavior that take the place of relationship protocol makes up for the lack of relationship it is the new, incredible, implausible form of relationship.

It would be a misreading to consider, on the basis of a literary tradition foreign to E. L. James's intended audience, which ranges from ephemeral fiction to the more literary... James' target audience, ranging from the erotic fiction of the Enlightenment to Sacher Masoch's The Venus in Fur (to which, incidentally, Fifty Shades of Grey never alludes19), this contract as a path to experimentation, to Anastasia's libertine education. Libertin, libertinage are also terms foreign to the novel.

The contract is very explicit about what it aims :

" The fundamental purpose of this contract is to enable the Submissive to explore her sensuality and boundaries safely, respecting her needs, limits and well-being.

(The fundamental purpose of this contract is to allow the Submissive to explore her sensuality and her limits safely, with due respect and regardf for her needs, her limits, and her well-being.) (CNG XI 227, FSG 165)

The contract is a personal protocol for managing enjoyment. Sensuality is jouissance, and it will be Ana's task to explore how and to what extent it can jouissance. The dominant's domination is not essential to this protocol; it is merely a means, by which he is denied as much as the submissive. What is essential, in this management, are limits: exploring one's limits, respecting one's limits. Managing limits replaces commitment to a relationship. The contract manages, arbitrates, the contradiction between the tendency of pleasure to unlimitedness and the limitations imposed by the body. The Submissive's body is in no way despised or humiliated, nor is it the object of any subjective domination20 : we leave behind a logic of the subject. The body is a pure body, respected, sanctuarized as a body. This is the contemporary biopolitical body, a celibate and singular body, an asocial and alveolar body, whose well-being the law respects, guarantees, protects, even promotes.

Biopolitics of the enjoying body

The contract, then, is not the peripheral whim of a perversely unbalanced person. Paradoxically, from the non-relationship it institutes between asubjective bodies, it makes society. It is the contemporary social contract, a global, universal, frightening contract, towards which the liberal capitalist society of control in which we are caught is tending.

This is the modern, unexpected aspect of this contract, which moreover reconduces the very old, feudal contract of marriage, which is a contract of female submission and property :

" 14.2 The Dominant accepts the Submissive as his property (to own), which he can control, dominate and discipline for the duration of the contract. [...]

14.13 The Submissive accepts the Dominant as her master, knowing that she is now the property (she is now the property) of the Dominant. " (CNG XI 231-233)

This property is not part of any financial transaction; the Submissive is in no way purchased. What seals ownership is a double and symmetrical acceptance, the very acceptance of marriage. Ana also points out to Christian, who readily acknowledges, that this binding contract, i.e. a contract that binds but does not establish a relationship, has no legal value. This contract is a vow, a sort of spiritual commitment, except that it only concerns bodies.

The troubadour's submission

The submission that the contract commits to is, moreover, explicitly linked to a very ancient era, via etymology. Christian Grey emails the narrator the dictionary definition of the word " soumis ":

" Origin: 1580-90; submiss + -ive " (FSG XIII 208)

To which Ana immediately responds by pointing out the enormous anachronism and the regression it implies :

" Sir, Please note the date of origin: 1580-90. I would respectfully remind Sir that the year is 2011. We have come a long way since then. " (p. 209)

In the French translation, the etymology is older, and produces a much more significant connection :

" Etymology : First half of the 12th century, from suzmetre "to put in a state of dependence (by force)." " (CNG XIII 27821)

The 12th century was the time when troubadouresque poetry of fin amor developed as a counterpoint to the brutality of feudal marriage. The marriage contract, which suz puts the wife and her property under her husband's jurisdiction, is opposed by the other law, of chivalry22 and love, which reverses the balance of power and places the Lady in the position of suzeraine. Denis de Rougemont thus sums up the symbolic splitting from which the whole of Western poetry is born, and hence a field, a regime of literature :

" We know that marriage, in the 12th century, had become for lords a pure and simple opportunity to enrich themselves, and to annex lands given as a dowry or hoped for in inheritance. When the "affair" turned sour, the wife was repudiated. The pretext of incest, curiously exploited, found no resistance from the Church: it was enough to allege, without too much proof, a fourth-degree relationship, to obtain an annulment. To these abuses, generators of endless quarrels and wars, courtly love opposes a fidelity independent of legal marriage and based on love alone. It even goes so far as to declare that love and marriage are not compatible23. "

The submission of the contract, the very submission described by the contract proposed by Christian Grey, claims its model in this marriage, which institutes a legal enjoyment of the woman, of the lands she brings, of the properties of which she is the pledge. This marriage, like the contract in the novel, is easily revocable, and the brutality of the fuck it administers is set against the ideal of the love it excludes. The dichotomy on which Fifty Shades of Grey fundamentally rests is the original symbolic splitting from which our Western literature has developed, as the flip side and supplement to the political system of oppression and control of which our contemporary societies are the culmination.

The contract is incestuous, always hovering over it the suspicion of incest from which it can be revoked. And indeed in the novel, if the contract is never made with Ana, or is ultimately made only to be immediately broken, Christian has already made use of this contract, the origin of which is his first, as it were incestuous, affair with Mrs Robinson, the " old friend " who raped and subjugated him24.

III. Reversal

The discovery of this homology of marriage and contract, which in no way institutes the sado-masochistic relationship, but carries the haunting and anguish of the old dead structure of feudal marriage and its juridical jouissance, leads us to completely reconsider the articulation between love and jouissance in Fifty Shades of Grey, in order to identify its reversed form.

Christian and Ana, the Lady and the Poet

Anna's desire for love seems a priori to anticipate marriage to her wealthy, handsome suitor. This is the pattern of the Enlightenment romance novel : the simple girl, Richardson's eternal Pamela, finally marries Mr. B., who has tried to seduce her, and becomes a lady. But since it is the contract that embodies, in the form of an abject repellent, fulfillment in marriage, Ana's demand must be interpreted differently, precisely as a demand for jouissance, as the desire to enjoy Christian completely, as the fantasy of possessing him totally.

But Christian has a secret. The one of the two who is secret isn't the woman, it's Christian. Christian's tireless sexual efficiency and the power he wields don't make him a virile figure of heroic masculinity. It's his youth and beauty that first strike Ana on their first meeting, when she stumbles across the threshold of his office :

" So young - and attractive, very attractive. " (CNG I 15, FSG 7)

Attractive is more properly said of an attractive, charming woman for a handsome man we more commonly use handsome : Christian's charm is not a priori that of the domineering male whose ultra-virile lure the contract seems to draw. As he sleeps and Ana contemplates him, he is the sleeping Bel :

" I'm starving. I head back out of the bedroom. Sleeping beauty25 is still sleeping, so I leave him and heead for the kitchen. " (CNG IX 176, FSG 126)

From the outset, moreover, the virility of this sleeping hermaphrodite is questioned by Ana who, reading the questions prepared by her friend Kate for the interview, asks him if he's gay26 : Kate has noticed that he's never accompanied (CNG I 35), and he tells Ana that " girlfriends aren't my thing " (CNG III 71) : no harem, then, whatever Ana's fantasies. When Christian Grey has Seattle's top gynecologist come to his house one Sunday to prescribe contraception, Ana wryly remarks :

" - I thought I was seeing your doctor, and don't tell me you're really a woman, because I won't believe you. " (CNG XVII 410, FSG 312)

Christian Grey is the one whose secret must be pierced, penetrated and violated. Conversely, Ana's virginity is by no means a fortress, just a situation that the novel hastens to rectify, according to an initiatory ritual, a ritual of passage that is a ritual of virility, of phallic experience. Ana harbors no secrets: if she is cleaved between her desire for jouissance and the surmoic voice of her subconscious, this cleavage refers much more in her case to symbolic castration and the schize of the phallic subject than to any secret or pas-tout de La Femme.

In Fifty Shades of Grey, Ana is " on the side where man ", on the side where all x is a function of Φx, where the subject is a " all x ", the affirmation of a One, a whole, through the play of the phallic function. The one who exercises this function, who asks, who experiences, who fully procures this jouissance, who believes in the love it promises, is Ana27.

" This is the act of love. Making love, as the name suggests, is poetry. But there's a world between poetry and the act. The act of love is the polymorphous perversion of the male, that in the speaking being. " (Lacan, Encore, p. 68)

And indeed Ana is a student of literature; an avid reader, she intends to work in publishing. Her desire for love is desire for poetry, the function of making love is the poetic function, which refers to the field, the regime of literature, in its very inadequacy with the real : between poetry and the act, between love and make love, between love poetry and the polymorphous perversion of the male (where Ana recognizes that jouissance resides) there's a world. At stake here is the function of the troubadour, i.e. the side, in love, where the man ranks. Faced with her,

" when any speaking being takes his place under the banner of women, it's from this that he grounds himself in not-being-everything, in placing himself in the phallic function. This is what defines the... the what? - woman precisely, except that La woman can only be written by crossing out La. There is no Lafemme, definite article to designate the universal. There is no La femme since - I've already risked the term, and why would I look twice ? - of her essence, she is not all " (Ibid.)

Christian takes his place under the banner of women : the contract of submission that defines him is a contract of management of female enjoyment.

Paradoxes of the phallic function

Ana fantasizes him surrounded by a cohort of submissives with whom he has put his contract to the test. Christian isn't everything; he has a secret, linked to the trauma of his childhood with a drug-addicted mother, hunger and beatings. This secret is the secret that generally founds the analytic subject, the knowledge and the secret on which every analysis undertakes to work : this knowledge, no one has access to it, it is posited as existing by the analysis, which works on it.

Christian places himself in the phallic function : his absolute sexual power, the brutality of his practices are never paradoxically manifested as assault, as non-consensual violence, as the forcing of consent. The insistence on the contract, more than the contract itself, has the essential function of guarding against the intrusive exercise of the phallic function. Christian is not the subject of the phallic function he is within it he supplies the demand he satisfies Ana's demand for phallic jouissance abundantly, excellently, flawlessly. In so doing, he brings to perfection the capitalist production of more pleasure: supply, not demand. The /// position of capitalist domination is the feminine position of supply, in the phallic function. The demand of masculine desire is the demand of the consumer : the demand for Ana.

Christian's offer is the offer of La femme : the real stakes, the deep stakes of the novel, are not Ana's possession, strictly controlled, limited, by the masochistic contract, but Christian's possession, which would be sealed by his consent to the marriage. The marriage Ana dreams of has nothing to do with the real, practical institution of marriage, with the regulation of enjoyment it institutes. It's the dream of an all-encompassing jouissance, the dream of love, which carries within itself its poetic process of failure, of being set up for failure, because it clashes with the not-all of La Femme, of which Christian constitutes the figurine and the completed capitalist fantasy. In the novel, Ana formulates this demand for an all-encompassing jouissance every time she says she wants more28. The vagueness of the formula points exactly to the other satisfaction, the supplement to phallic jouissance that Christian, the Lady, could provide.

The wanting more of courtly protocol

The underlying model on which both Ana's demand for love and the Lacanian theorization of La Femme as the poetic object of this demand is modeled is the courtly model, of which Fifty Shades of Grey offers an inverted representation, where the side where the man should position himself, where the phallic function is exercised, is occupied by the narrator, while under the banner of women ranks the figurine of her male fantasy, Christian Grey.

The lyric poetry of the troubadours, and its continuation by the trouvères of the 12th and 13th centuries, consists in the expression of this vouloir plus. The poet expresses his suffering in the face of the Lady's reluctance, as she sparingly consents to loosen the stranglehold of the chivalric service contract to which her lover has agreed to submit. It's all about getting the Lady to do more, so a negotiation is established between the poet's want more and the Lady's do more : this is the framework of the lyrical protocol that is grafted onto the chivalric contract29, and is expressed, for example, in this song by Blondel de Nesle :

" Dieu ! If my lady knew the pact (the couvine)

I have made with pain and sorrow !

Her heart, however, whispers

that my love for her tortures me !

She alone has all the power over me,

she alone knows the root of my evil.

Without her, no remedy will heal me,

nothing will restore my health30. "

The couvine, or convine, is the pact of love, which for the poet is a pact of pain and sorrow, which puts him to the torture : the spiritual pain of the poet in love becomes in Fifty Shades of Grey the material pain of the masochistic contract. Through this couvine, the Lady becomes the poet's sovereign through the contract, Christian becomes the Dominant. Here's how the poet imagines the end of this torturous amorous service :

" It's been so long that I've loved her, that I've served her,

now I deserve my reward (que la deserte en aie).

Then I'll see if she's loyal and frank

or if she's false and disloyal to me friend31. "

The poet's long service deserves dessert, release from service, satisfaction. This dessert becomes in Fifty Shades of Grey " wanting more ", the demand for the complete gift of love. But in the litany of pain, which provides the substance of the lyrical narrative, this reward, this point of culmination is in fact indefinitely /// postponed, so that ultimate consumption, all enjoyment, never comes.

In Fifty Shades of Grey, Christian is the Lady who proposes to her servant, to Ana, to engage in this protocol of suffering, the outcome of which she (Ana in the poet's position) catches herself hoping could be the full enjoyment of the beloved (Christian in the Lady's position), the gift by him, full and entire of his love. The contract is thus the distorted and chilling representation of feudal marriage, and its counterpoint, courtly protocol, the donnoi or the couvine, with its attendant suffering and procrastination.

Objections and responses

I'd like to pause for a moment at this stage of my demonstration, and try to respond to the objections, criticisms and snide septicism it is bound to elicit. What? To compare the sublime poems of our troubadours and trouvères of the 12th century, at the birth of Western poetry, with this rag of a novel, written in the most vulgar language, and conveying the most hackneyed clichés of the pulp novel, seasoned with a few salacious episodes that give it the cheap appeal of novelty ? And, on top of that, to link this comparison to Lacanian categories of jouissance and love, as if this psychoanalysis could be applied indifferently to such heterogeneous bodies of work? And even supposing such a comparison were relevant, what mediations, what transformations between the courtly love sung by Blondel de Nesle and the love 2.0 described by E. L. James !

First of all, it must be stressed that Lacan builds his theory of love and jouissance precisely from the courtly protocol that originated in the twelfth century, or at least from the representation of this protocol that he was able to read in Denis de Rougemont32. He refers to it as early as Seminar VII on The Ethics of Psychoanalysis33, and he returns to it in Seminar XX, Encore, referring moreover to Seminar VII34. Paradoxically, he presents " the invention of courtly love " as a " meteor " at the very moment when he theorizes La Femme comme pas-toute et l'autre satisfaction based on the terms and relationships instituted by courtly protocol.

The contradiction is only apparent, Lacan explains, in what is actually a very condensed way :

" After the meteor of courtly love, it was from an entirely different score that came what rejected it to its original futility. It took nothing less than scientific discourse, something that owes nothing to the presuppositions of the ancient soul.

And it is only from this that psychoanalysis arises, namely the objectification of what the speaking being still spends time talking about in pure loss. " (p. 79)

Without doubt, courtly love was not the meteor that Lacan evokes here : the great medieval novelistic prose cycles, Ficino's neo-Platonism (which updated the Renaissance's " presuppositions of the ancient soul "), Petrarchanism followed in its wake and durably installed its rules, its values, its protocol in the literary field, and organized a symbolic splitting that is still felt in Cornelian tragedy in the mid-seventeenth century. What had begun as a futile courtly entertainment in fact structured the poetic regime of our representations for over five centuries.

What does scientific discourse have to do with courtly love ? Lacan is referring here to the Copernican revolution that enabled Descartes to lay the foundations of the modern subject, based on the experience of the cogito, according to a model that no longer has anything to do with that of the cogito. /// of Platonic asceticism of the soul, in the experience of love. Love then loses its central hermeneutical function, in favor of the thought-experience of the cogito : it is thus, as it were, " rejected to its primary futility ".

But it is rejected, so to speak, only on the surface : the establishment of the Cartesian subject, whose consciousness becomes not only the seat of rationality but a rational object, susceptible to scientific investigation and modelling, opens up the exploration of its edges and underpinnings, from which psychoanalysis emerges. In this exteriority to the rationality of consciousness and its scientific discourse, psychoanalysis rediscovers the futile use of the spoken word, which is at once the reservoir of the unconscious, the archive of poetic lyrics of yesteryear and the place where we speak of love, with the broken words of today.

Spending time talking in pure loss : that's precisely what Anastasia Steele is doing, fresh out of university but not yet entering working life, who therefore finds herself precisely in the in-between of pure loss. As far as the action of the novel is concerned, from reversals to procrastination, it revolves around this contract, but does not sign it more to the point, the signing of the contract marks the end of the novel, which remains at its threshold, just as Anastasia remains at the threshold of life. The particularity of Fifty Shades of Grey is not only the reversal of the positions of man and woman in relation to courtly protocol it's also this edge relationship that fiction maintains with the contract. Indeed, it is not the contract itself, but rather the series of deviations negotiated with Christian (with the Lady) in relation to the contract (to satisfaction) that constitute the narrative basis from which to make poetry, the weft, the structure from which the narrator can compose the novel we read. Literature deregulates : it no longer plays with a law and a counter-law (of marriage and chivalry, feudal institution and courtly protocol), but with a haunting and a threshold, in the liberal fiction that for the lyrical subject no law applies, or at least does not yet apply.

So it's the contract that delimits the part of Christian reserved for secrecy, the unanalyzable part of the analytic subject what the contract won't deliver to Ana from Christian constitutes his secret what she truly desires from him, what she desires to enjoy in him is this secret that the clarity, the rationality, the simplicity, the technicality of the contract comes to screen.

The implementation of the contract depoetizes the amorous service : the Lady, Christian, can only surrender to the ultimate terms of the contract at the cost of breaking Ana's amorous courtship, programmed to fail.

The inversion is truly incredible, constructing the female fantasy (of E. L. James, of Ana) of domineering virility and triumphant capitalism from a figurine, Christian Grey, whose model is the Lady of the 12th-century amorous court. This phallocratic fantasy, this figurine of Christian Grey, embodies the completion of the pulsional device that governs our contemporary societies, but it also embodies them from what's left of the subject-poet, reduced to the rank of a slightly doddery female narrator. Anastasia Steele is the consuming and ordering figure of the device: she is the singularity that orders the collapse of contemporary capitalism. If the all-consuming grip of sex, of the desire for pleasure, in all the interstices, all the forms of social life, completes the transformation of our simulacra of democratic societies into biopolitical devices of pleasure, procedural, honeycombed, commodified, this apparently unanswerable triumph comes at the price of a general inversion of the sexes, where masculine domination comes to ground on the rock of any femininity. At the same time, or rather in the background, Christian /// Grey set about converting his empire, based on " the telecommunications industry35 "In the food industry and technology36 : the failure of enjoyment and its contract has as its corollary the shift from post-industrial information capitalism to subsistence capitalism.

" - I can't stay. I know what I want and you can't give it to me, and I can't give you what you need. " (CNG XXVI 664, FSG 513)

The intersubjective circulation of love and jouissance, their communication breaks down here, in the face-off of two devouring hungers. Never has thewant more and its courteous economy of desire been so imperious.

Notes

References are given for the original text in the Arrow Books edition, London, 2012, abbreviated FSG, and for the French translation by Denyse Beaulieu, J. C. Lattès, 2012, in the Livre de Poche edition, 2014, abbreviated CNG. The chapter number follows in Roman numerals, and the pages in Arabic numerals. The quality and fidelity of Denyse Beaulieu's translation must be emphasized : when I comment on the deviations or omissions of the French translation from the English original one must bear in mind that the efficiency and fluidity required for the reader differ from the attention to the letter, which must be that of the critic.

Lacan, Le Séminaire, livre XX, Encore [1972-1973], ed. J. A. Miller, Seuil, 1975.

Christian Grey undergoes therapy, with Dr. Flynn.

This sentence is omitted in Denyse Beaulieu's translation.

Exciting, rather...

This distinction recurs obsessively in the novel. See in particular CNG VIII 155, IX 177 (cited and analyzed below), XII 271, XX 470, XXI 487.

These are the " firsts " : each stage of the novel constitutes a first for Christian Grey. The firsts are so many departures from the rules of protocol which, far beyond the contract he claims Ana is signing, order his otherwise extraordinarily timed and tidy life, right down to the debauchery of his " other life ". See CNG V 110 (sleeping with a woman in his bed), VI 129 (taking a woman in his helicopter), IX 190 (fellatio), X 199 (introducing a woman to his mother), 211 (" a weekend with many firsts "), XII 266 (not knowing what to say), 267 (getting fired), XVII 386 (being late), XXIV 583 (taking a woman gliding), XXV 637 (fucking while listening to Thomas Tallis' Spem in Alium). The sum of the former draws the Carte du Tendre according to which, paradoxically within the entirely conventional rules of the pink novel, Christian Grey woos Ana.

" This is why it's important for us to realize what analytic discourse is made of, and not to ignore this, which undoubtedly has only a limited place in it, namely that we're talking about what the verb foutre perfectly enunciates. We're talking about foutre - verb, in English to fuck - and we're saying that it doesn't fit. " (Lacan, Encore, p. 33) Isn't that exactly what E. L. James says ?

The generalization of protocols as a profound trend in our contemporary societies was analyzed by Michel Foucault in Surveiller et punir, Gallimard, 19754, then in his Collège de France lectures, Sécurité, territoire, population (1977-1978) and Naissance de la biopolitique (1978-1979), EHESS-Gallimard-Seuil, 2004.

Jean-François Lyotard, Des dispositifs pulsionnels, Galilée, 1994.

I'd translate : " My superego gives me the stink eye - its way of fucking, not of making love, it screams at me like a harpye. "

This sentence is omitted in Denyse Beaulieu's translation.

CNG IX 184, X 211-212, XX 468, XXIII 569.

Lacan, Encore, " la bêtise ", p. 16-18, and " Le signifiant est bête. It seems to me that this is likely to generate a smile, a stupid smile naturally. A silly smile, as everyone knows - you only have to go to the cathedrals - is an angel's smile. In fact, that's the only justification for Pascal's warning. And if the angel has such a silly smile, it's because he's swimming in the supreme signifier. It would do him good to be a little dry - maybe he'd stop smiling. It's not that I don't believe in angels - everyone knows I believe in them inextricably and even inexteilhardently - I just don't believe they bring the slightest message, and that's why they're really signifiers. " (p. 24)

On Ana's stupidity : " what a pie ! " (CNG II 29), " idiotic questions annoy him " (II 30), "swallow the idiotic smile that threatens to split my face in two " (III 62), " planted in front of him like an idiot " (IV 74), " apart from an idiot calling you in the middle of the night " (IV 92), " like an idiot " (VII 147), " sex, quite stupidly, Anastsia " (X 211), " don't be an idiot " (X 213), " smiling like a moron " (XI 246), " holy klutz " (XIII 285), " I feel a bit of a klutz with this " (XIV 320), " there's nobody more klutz than me " (XVI 371), " poor klutz " (XIX 444), " a good old silly sex-vanilla " (XX 468), " I looked like an idiot " (XXII 510), " smiling like an idiot " (XXIII 570), " smiling stupidly " (XXIV 591).

See Virgil, Aeneid, Canto III, v. 210-244.

CNG I 21 ; II 41 ; III 50 (Christian Grey invests in agri-food technologies) ; III 63 (" Would you like something to eat ? "), V 109 (" Eat, [...] empty your plate. "), VI 134 (" Are you hungry ? "), VII 143 (" You must eat "), 145 (" You will eat "), VII 148 (" the Submissive will not nibble between meals "), IX 180-181 (" Eat "), X 209 (" You must eat "), 213 (" Eat "), 215 (" I watch him devour everything on his plate. He eats like an ogre "), 224 (" What is this obsession with food ? "), XIII 288 (" You have to eat "), XIV 315 /// (" I myself have known hunger ") 316 (" his obsession with food "), XV 337 (" Have you eaten today ? There it is again. "), XVI 376 (" I also learned that Christian had experienced hunger... "), XVII 409 (" Have you eaten ?" he asks me point-blank. Shit), XVIII 414-4125 (" you must eat [...]. The god of sex insists on folding my stomach. "), XIX 451 (" Christian keeps his good mood until the end of the meal, no doubt partly because he sees me eating with good appetite "), XXI 491 (" Of course you're going to eat "), XXII 532 (" And I'm indeed delighted to hear you're eating "), XXIV 573 (" Come on, eat "), 576 (" Eat, he orders me ").

Compare with lunch in the previous chapter : " Is this what our, er... relationship will be like) ? You're going to order me around ? I can't look him in the eye. - Yes " (CNG X 214, FSG 155) Ana even hesitates to formulate a " nous ", an " notre " that would commit the existence of a relationship. The relationship is the unthinkable around which their exchange circulates.

The contract in Fifty Shades of Grey instates an inverse relationship to that in La Vénus à la fourrure, since in Sacher Masoch it's Wanda who makes the male narrator her slave. See Gilles Deleuze, Présentation de Sacher-Masoch, avec le texte intégral de La Vénus à la fourrure, Minuit, 1967, p. 195. Séverin von Kusiemski renounces his status as lover for that of slave, agrees to be mistreated by his mistress " according to her good pleasure " ; in exchange " Madame von Dunajev agrees as his mistress to show herself as often as possible in fur ". The contract exchanges a loving relationship for a perverse one, in which the slave satisfies her fantasy of Venus in fur. There's never any question of suffering, and everything is relationship. In Fifty Shades of Grey the contract doesn't actually evoke any relationship, since it separates in each of its articles what concerns the Dominant and the Submissive. The essence of the contract is the management of suffering, which Sacher Masoch's contract is precisely designed to ignore. The two contracts are therefore literally mutually exclusive.

Servitude is mentioned only once, in article 14.5 (15.5 in the English original) : the Dominant may, by punishment, " ensure that the Submissive takes the full measure of her servitude to the Dominant (her role of subservience to the Dominant) ". (CNG XI 231, FSG 168. English Article 1, The following are the terms of a binding contract between the Dominant and the Submissive, has been deleted in French, hence the discrepancy.)

Denyse Beaulieu takes up here the etymology that the Trésor de la langue françaiseproposes at the end of the article Soumettre.

If the 12th-century etymology isn't in the original text, that's the spirit of it. Indeed, Anastasia Steele makes several references to chivalry : " Have you escaped from a medieval chronicle, or what ? You sound like a courtly knight (Which medieval chronicle did you escape from ? You sound like a courtly knight) " (CNG V 98, FSG 67), " He loves me enough to rescue me when he thinks I'm in danger. He's not a black knight but a white knight in shining armor, a hero from a novel, a Gauvain or Lancelot (He cares /// enough to come and rescue me from some mistakenly perceived danger. He's not a dark knight at all but a white knight in shining, dazzling armor - a classic romantic hero - Sir Gawain or Sir Lancelot) " (CNG V 100, FSG 68-69), " Chevalier noir, chevalier blanc : c'est une bonne métaphore pour Christian (Dark knight and white knight, it's a fitting metaphor for Christian) " (CNG VI 131, FSG 92), " This man, whom I once thought a valiant white knight - or a dark knight, as he said - is not a romantic hero, but a deeply disturbed being who leads me down a dark path (This man, whom I once thought a romantic hero, a brave shining white knight - or the dark knight, as he said. He's not a hero; he's a man with serious, deep emotional flaws, and he's dragging me into the dark) " (CNG XX 466, FSG 355).

Denis de Rougemont, L'Amour et l'Occident [1st ed. 1938], Plon, 1972, 10/18, 1983, p. 35. Denis de Rougemont's assertions are undoubtedly dated, caricatured and ideologically dubious. They nonetheless synthesize a certain modern genealogy of love, of which Fifty Shades of Grey is the culmination... and point of no return.

See for example CNG XXII 534, FSG 413.

I correct the translation, incorrect in French, by " Beau ". The undifferentiation of Bel and Belle in French is just the thing to translate the English neutral !

CNG I 23, see also II 30, 34, 38, III 67, 71, 210, 312, 339, 379, 410, 535.

Lacan, Encore, p. 67 and 74.

" but I want more " (CNG XIV 325), " you told me you wanted more " (XV 345), " I want more. I want him to stay because he wants to stay with me, not because I'm bawling like a calf" (XVI 378), " He leans over to whisper in my ear : - I want more - much, much more " (XVIII 429, here, in the red room, Christian ironically echoes Ana's formula), " Deep down, I know I want more, quite simply : more tenderness, more lightness, more... love. " (XX 465), " - I want more. -I know," he murmurs. I'll try." (XX 466), " I'm glad you told me you'd try to do more. I just need to think about what 'more' means to me" (XXII 515, e-mail from Ana), "Then tell me what you want more of. I'll try to stay open, to give you the space you need " (XXII 523, e-mail from Christian), " - What happened to her ? - We broke up. [She wanted more. The sentence hangs in the air between us. That explosive little word again. - Not you? [I never wanted to go any further until I met you. " (XXIV 580), " - So, how was it ? he asks, his eyes a dazzling silver-gray. -Extraordinary. Thank you so much. - Was it... more ? he asks, a hint of hope in his voice. - Much more " (XXIV 590), " But I've already told you, I want more too. Oh, my God. He's letting himself be convinced" (XXIV 592), " - It makes me happy, that you want more. - I know you do. - How do you know? -How do you know? - Trust me, I know," he says with a chuckle. He's hiding something from me. What ? " (XXIV /// 596), " - Thank you for the... more. " (XXIV 597), " - Well, I think the contract has expired, don't you ? [...] - But you wanted it so much ? -That was before. But the rules still apply. - Before? Before what? -Before... He's silent for a moment. - Before... "more". " (XXVI 646).

This courtly protocol is formulated thus by Denis de Rougemont : " But this courtly fidelity presents a most curious feature : it opposes, as much as marriage, the "satisfaction" of love. "He knows of donnoi really nothing, he who desires his lady's entire possession. This is no longer love, which turns to reality." " (L'Amour et l'occident, op. cit., p. 35-36). Rougemont cites Claude-Charles Fauriel, Histoire de la poésie provençale. Cours fait à la Faculté des lettres de Paris, Paris, Jules Labitte, 1846, I, 512. Fauriel translates a nine-verse poem by an unnamed troubadour. De Rougemont retains only the beginning, which is subsequently included in all histories, studies and summaries of Provençal poetry.The donnoi is the ritual of chivalric love, imposed by the Lady, which consists of a " graduated series " of " favors, permitted enjoyments " making up " a kind of rule " (Fauriel, op. cit., p. 511. We can see here how Lacan has imbibed the formulations of the Provençalists.)

" III. Deus ! Car seüst ma dame la couvine | De la doleur que j'ai et de la paine ! | Car ses cuers bien li dit et adevine | Conment s'amours me travaille et demaine. | Seur toutes autres est el souveraine | Car melz conoist de mes maus la racine. | Ne puis sanz li re couvrer medecine | Ne guerison qui me soit preus ne saine. " (Li Rossignous a noncié la nouvele, in Poèmes d'amour des XIIe et XIIIe siècles, ed. Emmanuelle Baumgartner and Françoise Ferrand, 10/18, 1983, p. 24)

" Mult longuement l'ai amee et servie : | Bien est mes tems que la deserte en aie. | Or verrai bien s'ele est loiaus et vraie | Ou s'el m'est fausse et desloiaus amie. " (Ibid., stanza V, p. 26)

See for example Encore, op. cit., p. 70.

" L'amour courtois en anamorphose ", séance du 10 février 1960, in Le Séminaire, livre VII, L'Éthique de la psychanalyse, Seuil, 1986, p. 174-184.

Seminar XX is haunted by Seminar VII. The first word of Seminar XX is " It happened to me not to publish the Ethics of Psychoanalysis ". The session of February 13, 1973, also opens with a reference to the 1959-1960 seminar : " In dealing a long, long time ago with the ethics of psychoanalysis, I started from nothing less than Aristotle's Ethics to Nicomachus. " (Encore, op. cit., p. 49) Lacan returns to courtly love in the session of March 13, 1973, which J. A. Miller titles " Une lettre d'âmour " (see p. 79).

CNG I 19, the telecommunications businesse, FSG I 10-11.

It is for this reason and in this field that he invests in the university, whose generous sponsor he is by no means gratuitous. See CNG I 21, II 41, III 50.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « 50 nuances de Grey » , Séminaire LIPS, automne 2021, université d'Aix-Marseille.

Littérature et Psychanalyse

Archive mise à jour depuis 2019

Littérature et Psychanalyse

Le Master LIPS

Séminaire Amour et Jouissance (2019-2021)

Amour et Jouissance

Jouir et Posséder

Vers l'amour-amitié

Les signifiants du désir

50 nuances de Grey

Duras, la scène vide