Eighteenth-century painting is defined both as classical painting and as painting in crisis. Deployed in Enlightenment Europe under the aegis of the Royal Academy of Painting, it established norms, codes of representation; it could only be composed, executed, viewed and critiqued in the exercise of a relationship to this canon.

The entire history of Western painting, from the generalization of linear perspective invented in Italy at the dawn of the Renaissance, is summoned to fix, systematize this canon around a model, a scenic device of representation that becomes a posteriori the classical device.

The ambiguity lies in this "after-the-fact" effect of classicism: in the Italy of a Michelangelo and a Raphael, no institution could claim to play the normative role imposed, in eighteenth-century France, by the Academy. Coming after the fact, but constituted by the great creators of the moment, the norm cannot be identified with conservatism. Rather, it is a rationalization, the integration of a practice in the making into an immobile discourse.

Through her, then, the device freezes. But the life of the painting takes its course. By the time the scene is formalized, it has already been undone: the theatrical model, necessarily summoned by the pictorial scene, is in crisis, and the conventions of dramatic genres are flying apart. Gentle emotion and tears, expressed in ordinary language or, better still, in the silent eloquence of pantomime, are preferred to the distinction of tragic discourse. The vestibules of royal palaces, where the gap between the parterre of ordinary people and the inaccessible retreats of Power was widened, are preferred to the bourgeois intimacy of the salon, a stage on a level with the spectator.

.The barriers fall, the emotion spreads from reality to performance, then from stage to spectator, the continuous current of tears: the theatrical effect wins from close to close, by contagion.

A new economy of representation is then established, no longer based on difference (between nature and representation), but on this emotion created, this flow that comes and goes from the spectator to the stage, tying him to it. The first pictorial consequence of this semiological revolution is the deconstruction of the very notion of the figure: in the internal economy of representation, classical difference was first and foremost the difference of figures, the distinction of characters that made it easy to substitute for discourse. In the sensitive fusion and rebellious spasm that painting now instills in the spectator's eye, the new primacy of color and flesh matter tend to abolish the interplay of figures. The discourse of the scene, the rhetorical expression of passions, are swept up in the new common contagion, colorful and mute.

The crisis of the figure should not, however, be seen as the collapse of the classical edifice of representation: in a way it ensures its second existence, the deconstruction of the figure constituting the foundation of the new economy of the revolted eye. The stage is no longer given from the outset by the layout of the locations and the distribution of roles between the figures. In a collapsed set-up, emotion and the sensitive interweaving in which the eye is precipitated, crystallize in the moment what will make the scene: the scene happens or doesn't happen at the end of a scopic crystallization that does or doesn't happen. The face-to-face encounter with the canvas becomes the test of an encounter, with the eye gathering momentum at the risk of catching or, on the contrary, falling back. The hook always goes against: resistance of the body or rebellious discourse, deviation of meaning or flesh, only the awareness of what grips the classical machinery of figures allows this crystallization.

The scene thus plays on these two economies: adventuring through the eye, through crystallization in the moment, it unfolds for want of the other, for want of this utopian norm, this unreal past of the scene that the spectator summons with enjoyment and nostalgia. To model the scene, to fix it with a schema, to reduce it to a structure[1], is to repeat the mirage constructed by the Enlightenment. To understand it, we need instead to grasp it in this anamorphic process, first as disfigurement, then as crystallization and revolt, and finally as nostalgia.

We therefore need to relearn how to look at this Enlightenment painting, in this movement of the scene as it makes and unmakes itself. There can be no aesthetic pleasure without this back-and-forth. Diderot's Salons are an invaluable tool for getting as close as possible to this, because when detailed, they express in detail what generally remains in the informal intimacy of the solitary pleasure of seeing. We therefore propose to follow step by step one of the most exemplary texts of the Salons in this respect, the commentary on Vanloo's La Chaste Suzanne, at the beginning of the Salon of 1765. Not only is this commentary a model of the genre, but the chosen subject provides the painting with an exemplary scenic device.

Remind that the story of Susanna, an apocryphal episode from the book of Daniel, takes place during the period known as the Babylonian Captivity. Susanna, the virtuous wife of the wealthy Ioakim, is surprised by two elderly neighbors when, after dismissing her servants, she bathes alone in the Bath set up in her garden. The old men blackmail her: if she doesn't give in to their desires, they will accuse her of adultery and stone her to death, as prescribed by Jewish law. Suzanne resists; the old men accuse her; Daniel, still a child, then intervenes and by questioning the old men separately, confounds them; the punishment thus falls on the slanderers, and the old men are stoned.

.In the Middle Ages and early Renaissance, Daniel's trial and intervention are often depicted as the triumph of justice and the prophet's performance. But when the scenic device became more widespread, the moment of blackmail by the elders, the surprised intimacy of Susanna, took hold and enjoyed an extraordinary vogue in religious painting, almost disproportionate if we consider that this apocryphal episode is only very debatably attached to the canon of texts making up the authorized Bible. There's no doubt that the artists' motivation was not exclusively religious: the Susanna scene constitutes something of a semiological prototype, allowing the resources of the classical scenic device to be exploited to the full.

.I. Figures in a place

Suzanne's body

What first defines a painted scene is that something in it is stopped. The scene stops a narrative: in so doing, it sends the viewer back to this sequence that it cannot produce; but it also indicates that it will be about something other than what, through this stop, has just been spurned.

"In the center of the canvas, we see Susanna seated; she has just come out of the bath."

The bath precedes the pause. Similarly, for the eye, the water in the basin, at the lower edge of the canvas, precedes the ascent to the flesh, the head, the pressure of the old men.

"Placed between the two old men, she leans toward the one on the left, and abandons to the gaze of the one on the right her beautiful arm, her beautiful shoulders, her loins, one of her thighs, her entire head, three-quarters of her charms."

Placed, leaning, abandoning... Diderot describes an arrangement, a geometrical organization: that is, in a given space, that of the bath, three figures. The idea is to place them, to assign them abscissas and ordinates, to make them stand in relation to each other. There's nothing visual a priori about this order: geometry logically manipulates objects, it abstracts, it intellectualizes the space it accounts for; it blinds it.

But the description slips: "placed between the two old men", Suzanne is still at equilibrium at the beginning of the sentence; "leaning towards", she betrays the disturbance of a clinamen. Finally, she "abandons to the gaze", undoing the geometrical arrangement and precipitating the eye towards scopic crystallization.

Unbalanced, the figure unravels. Suzanne unfolds in the paradigmatic juxtaposition of her limbs like a disarticulated body. She is no longer the chaste Suzanne, figure one placed in a space that gives her meaning, that provides a setting from which to decode her; she is "her beautiful arm", no, not even, but at the top of that arm, "her beautiful shoulders", and the eye slides inexorably towards the aim of desire, along the body towards "her loins", then turning ever closer to its target, towards "one of her thighs"... Desire panics, the gaze becomes disoriented, struggling between attraction and prohibition, the gesture that harms and the repressed desire. The sentence mimics this debate, regaining momentum after the touch of her thigh, pulling herself together with "all her head", only to immediately forfeit, ending in a final breath with the confession: "three quarters of her charms".

.

The confession recaptures the figure, restores the body to its entirety, even when crossed out by the semiotic cut: three-quarters and one-quarter, Suzanne is divided between what in her is abandoned and what resists. Through this cut, she becomes an object of language:

"Her head is overturned; her eyes turned skyward beckon for help; her left arm holds back the cloths covering her upper thighs; her right hand spreads, pushes away the left arm of the old man on this side."

To every figure corresponds a discourse, through which the visual dimension of the thing is once again obscured. Suzanne is no longer a body, but a voice calling on Heaven for help. The upside-down head is an eloquent head, an oratorical sign. Arms and hands are no longer lines of flesh where the desiring eye rushes and electrifies, but the differentiated, swaying punctuations of a mute, mimed discourse: left arm and right hand oppose each other; one holds back to the right, the other pushes back to the left; one leads back to the object of desire it bars, the other leads away from the object it denies. Discursive articulation kills desire.

Praise as a trap for the eye

Diderot will thus have given an account of Suzanne's body in three forms: the geometrical, blind form of the disposed body; the scopic, disfiguring form of the desirable body; the symbolic, or figurative, form of the eloquent body. The rhetorical stylization of the body brings the account back to its original model, the model of ekphrasis : to describe is to praise.

"The beautiful figure! The position is great; her trouble, her pain are strongly expressed; she is drawn with great taste; these are true flesh, the most beautiful color, and all full of truths of nature spread on the neck, on the throat, at the knees; her legs, her thighs, all her undulating limbs could not be better placed; there is grace without detracting from nobility, variety without any affectation of contrast. The half-tone part of the figure is beautifully done. The white linen spread over the thighs reflects admirably on the flesh; it's a mass of light that doesn't destroy the effect: a difficult magic that shows both the master's skill and the vigor of his coloring."

The praise is primarily technical, praising composition and drawing, then the rendering of flesh and color. Diderot distributes the compliment between the two main technical categories, which correspond to the two schools that clashed at the Académie, partisans of drawing, or poussinistes, and partisans of color, or rubénistes. He then returns to the body parts, using the same enumerative process that meanders along the female forms, throat, knees, linen on the thighs, as close as possible to the sex, the ultimate target. The eye finally fixes on the blinding brilliance of the linen, a screen to the sex at stake and at the same time melted into it since, "reflecting admirably on the flesh", it sets up a continuum of whiteness from garment to flesh, from forbidden nudity to the canvas that covers it.

Praise, then, is not a pure redundancy of the great, the beautiful and the good. It operates a displacement, from the categories of technical evaluation, drawing and color, to the trap of desire for the eye constituted by the sensitive screen of linen laid over Suzanne's thighs, occluding her sex and designating it, melting into it. The eulogy sanctifies the descent of the eye, installing the eye in Suzanne's lower body. The general, abstract discourse on the excellence of the work, the rhetorical exaltation, is converted into scopic crystallization, which takes place on the spot of white, spot and envelope, screen: the screen here, however, is not the wooden claustra or stone balustrade that traditionally separates Suzanne from the old men; the screen is not a border between two territories. White abolishes contours: from drawing to color, from color to the magic of white, the whole edifice of classical figuration unravels, and the screen becomes the instrument of this defection, a sort of hole wall designating the space of invisibility where desire tends.

Diderot thus accomplishes the performance of the eulogy, reiterates the age-old oratorical pose of the ekphrasis ; but at the same time, he tells its limit and end, the tipping of an economy of speech into an economy of desire.

Criticism as disfiguration

Hitherto, the commentary has focused on Suzanne, the composition's central character; Diderot now turns his attention to the two old men: praise of the figure then switches to criticism and disfiguration.

"The old man on the left is seen in profile. His left leg is bent, and with his right knee he seems to be pressing the underside of Suzanne's thigh. His left hand pulls at the cloth covering her thighs, and his right hand invites Suzanne to yield. This old man has a false air of Henri IV. This head character is well chosen, but it needed more movement, more action, more desire, more expression. It's a cold, heavy figure, with nothing but a large, stiff, uniform, foldless garment, under which nothing stands out: it's a sack from which a head and two arms emerge. It needs to be draped broadly, no doubt, but it's not like that.

The characterization of the old man goes off the rails from the outset: Vanloo hasn't painted a corrupt Jewish judge from biblical Babylon, but "a false air of Henri IV": the Cycle de la Vie de Marie de Médicis painted by Rubens for the Palais du Luxembourg now identifies the profile of the mature man with the bourbon nose, sparkling eye and pointed beard with Henri IV. The identification is all the more irrepressible given that Henri IV, nicknamed le vert galant, was known for his passion for women well into old age. Voltaire echoes in the Essai sur les mœurs the abominable reputation that Bayle, in the Dictionnaire historique et critique had given him[2].

For this reason, Diderot concedes, not without mischief, that, paradoxically, "this head character is well chosen". But the figure immediately unravels. We are witnessing the abortion of scopic crystallization. Diderot had set in motion the geometrical play of the figure, the gestures of the action ("left leg bent", "right knee [which] seems to press the underside of Suzanne's thigh"), the progress of desire through the "left hand", then its verbal expression through the "right hand" accompanying the blackmail speech.

But "it was necessary to add more movement, more action, more desire, more expression": the abstract nouns take up in the same order and characterize rhetorically what the body parts had indicated geometrically. From the legs to the left hand, we pass from movement to action and desire; from the left hand to the right, from desire to expression. The eye then makes the same journey from bottom to top, from left to right, from shameful to exposed, but without settling, without finding the hook by which the whole becomes meaning and tableau.

.Then comes the eye's third journey, still following the same path, but this time focusing on the garment, i.e., as close to the texture as possible, on what is likely to establish the hook, to knot the gaze's interlacing. It is then that the figure completely unravels, tipping over into the formlessness, the crude, monstrous abjection of the bag[3]. The bag is linked to the imaginary of impotence: "nothing is drawn" is indeed understood as the dissolution of features, but also as the absence of the marks of male excitation[4]: the failure of scopic crystallization, the defection of figures equivalent to a failed erection.

Writing, the oratorical performance of ekphrasis, then makes up for what for the eye has been missed. Since the libidinous old men's gestures freeze and abort, the spectator's gesture takes their place, reengaging the mechanics of desire:

The gesture of the spectator is the substitute for the gesture of the libidinous old men.

"The other old man is standing and seen almost from the front. With his left hand, he has pushed aside all the veils that robbed him of the Suzanne on his side; he is still holding these veils apart. His right hand and his arm stretched out in front of the woman have a threatening gesture; this is also the expression on his face. This one is even colder than the other: cover the rest of the canvas, and this figure will show you nothing more than a Pharisee proposing some difficulty to Jesus Christ."

There's a double movement in this criticism of the old man on the left: the movement of the old man who unveils Suzanne, delivers her as pasture for the eye; the movement of the viewer who covers the canvas, veils Suzanne and, thus marking a pause, artificially reintroduces the cut of a screen. Veiling, unveiling: the oratorical performance re-establishes for the eye the pulsation of what is exhibited and subtracted, of what can only be seen crossed out, and can be seen precisely in the fundamental essence of this crossed-out signified that is the woman offered and refused to enjoyment, delivered, but "not all". The viewer virtually veils the canvas, at the moment Suzanne is unveiled and after the first old man has dissolved into a sack of canvas: fabric on fabric, the eye touches and crumples linen, amalgamates pictorial matter and skin, flesh and figure.

Once again, in this shift, the figure slips, the old man is characterized in a shifted way: the "Pharisee who proposes some difficulty to Jesus Christ" evoked by Diderot inevitably refers to the evangelical scene of the adulterous woman, a veritable anagogic actualization of the Susanna from the Book of Daniel.

"Now the scribes and Pharisees bring a woman caught in adultery and, placing her in the middle, they say to Jesus, "Teacher, this woman has been caught in the act of adultery. Now, in the Law, Moses commanded us to stone such women. They said this to test him, so as to have something to accuse him of." (John, VIII, 4-6.)

The old men will bring Susanna before Ioakim her husband bearing the same accusation and with the same result, so that the parable of the Gospels appears as if not the re-telling, rather the one-upmanship of Susanna's story: Daniel clears an innocent and unjustly accused Susanna; Christ forgives a guilty woman against the Law. The Pharisees of the Gospels seek to put Christ at fault; through the adulterous woman they hand over to his judgment, they intend to contradict the Law and his teaching. They put him to the test, they "propose a difficulty" to him: Diderot's expression fits this context perfectly.

Vanloo's old man has his right arm "extended" towards the center and back of the painting. Diderot does not explain this gesture, which, like that of his acolyte, carries the figure's discourse: designating the vague space, the outside from which at any moment someone could emerge and surprise the young woman in this equivocal posture, the arm indicates to whom the slander will be directed, to the husband now absent, to the community that will assemble to judge the young woman. Taken out of context, however, and projected into the Gospel scene, this arm could just as easily be calling out to Christ, who is busy writing on the ground, as can be seen, clearly, left in Tiepolo's composition on this subject[5], or, less characteristically, in Poussin's[6].

Like the reference to Henri IV, the identification of the old man with a Pharisee from the parable of the adulterous woman distracts from the subject, but at the same time brings us back to it, and this time in the purest tradition of the Christian reading of images: Christian meditation relates Old Testament stories to New Testament parables, the plurality of figures to the unique mystery of faith.

II. Terror and the norm: the economy of revolt

Imaginary reconstruction

After this vicarious scopic crystallization, the text completes its work of reconstruction.

"More heat, more violence, more anger in the old men, would have given a prodigious interest to this innocent and beautiful woman, delivered to the mercy of two old scoundrels; she herself would have more terror and expression from it, for everything is entangled. The passions on the canvas match and mismatch like the colors. There is an overall harmony of feeling and tone. Had the old men been more urgent, the painter would have felt that the woman must have been more frightened, and soon her gaze would have made the sky an entirely different instance."

Under cover of taking the field, of repeating the scene differently, Diderot makes it continue. Heat, violence, frenzy: we are no longer, as at the beginning of the account, at the end of the bath, in the moment of surprise, but at the heart of the rape, in the convulsive excitement of hurried bodies. It's no longer a disposition of bodies given to see, it's a pressure ("les vieillards plus pressants"), a drive ("tout s entraîne "): agreement, disagreement, harmony are summoned under the pretext of color; but Diderot imposes at the same time the cadence of the opera aria, superimposing the absolute disorder of desire and the musical ordering of terror. Space becomes purely sensitive ("the painter would have senti..."), without geometrality or theatricalization of a gaze. From this cadenced convulsion, the outcome is a gaze, not the gaze we place on the object of the scene, but the gaze the convulsion produces, this reversal of the attack suffered into a gaze thrown, this revolt of Suzanne's body which, pressed from all sides, attests to the sky, turns towards it.

Here we touch on that fundamentally new economy that takes shape under Diderot's eye and pen, that economy of the revolted eye, which turns the geometrical "on voit" into a sensitive "ça regarde", which cancels the cut posed by the scene in favor of a continuity of touch, emotion, revolt. "Cover the rest of the canvas": the economy of the stage posited and abolished the separation between the viewer and the painted composition, giving and taking away sight. The screen, with the geometric distributions it instituted in space, reverberated in the writing of the account: praise and disappointment, prestiges of wonder and collapse of illusion, textually transpose this same oscillation, pulsation of phallic desire.

Here it is, however, replaced by another economy. Everything is now played out between the pressure and resistance of flesh, between the drive towards rape and the body's revolt, the spasm, the "instance". The eye weaves continuities and carries this movement forward, this precipitation destined to turn, to revolt, eye skin out of discourse of the female body that is no longer the object of the rape of two old scoundrels, but the tactile extension of what "the painter would have felt".

In this new economy of the revolted eye, Diderot takes up again at the beginning, like an anodyne repetition, the geometrical description of the scene:

"On the right we see a greyish stone factory; it's apparently a reservoir, a bathing apartment; in front a canal from which a petty, tasteless little jet of water gushes to the right, breaking the silence. If the old men had had all the outburst imaginable and the Suzanne all the analogous terror, I don't know if the hiss, the sound of a mass of water rushing with force wouldn't have been a very true accessory."

"On voit à droite" echoes "On voit au center", with which the account opened. But it's no longer a question of arranging figures in a space regulated by perspective. "Fabrique" is a painter's word, designating any construction intended to structure the space of representation. Here, the factory oppresses and crushes the figures. Diderot distinguishes a small jet of water, absent from the engraving, either due to the engraver's negligence, or rather to the philosopher's confusion with one of the Suzanne he will later evoke by comparison. The point is to restore the majesty of the jet: Diderot virtually makes the old men's outburst coincide with the "mass of water rushing with force", just as in the real world the abortion of the rape coincides with the pettiness of the small jet. The obscene metaphor is patently obvious, and speaks to the extent to which the figures' relationship to space has changed: the differential system that opposed the vagueness of an extra-scenic space, occupied by reality, to the circumscribed symbolicity of the stage proper, has been replaced by a system of contagion, of sensitive continuity, where the factory replays, accompanies and amplifies what, at the heart of the performance space, has entered into resonance, has launched the influx. Through the use of color, we noticed the entry into play of a musical vocabulary, in which "chord" and "harmony" were the vectors of meaning. The "hissing, noisy sound of a body of water", and not, for example, its glistening, splashing sound, mark that the implicit model here is again acoustic.

Vanloo and de Troy

From internal resonances, we then move on to external ones, and Vanloo's work comes to take its place, through public judgment, in a virtual gallery alongside the famous Suzanne:

"With these flaws, this composition by Vanloo is still a beautiful thing. De Troye painted the same subject. There is scarcely an early painter whose imagination it has not caught and whose brush it has not occupied, and I'll wager that Vanloo's picture stands up in the midst of all that has been done."

Already dead when Diderot wrote, Jean-François de Troy (1679-1752) belonged to the generation that preceded that of Carle Vanloo (1705-1765). He painted Suzanne et les vieillards on several occasions.

The 1721 version[7] went on sale in Paris on December 10, 1764. It entered the collections of Catherine II between 1766 and 1768, and is still in the Hermitage collections today. This suggests that Diderot was familiar with the 1721 painting. Like Vanloo's, J. F. de Troy's composition is high (235x178 cm). It already features the stone border of the water basin at the bottom, the old men on either side of Suzanne, one on the left, standing and giving Suzanne a speech, the other on the right, seated, feeling her thigh and arm. The very position of Suzanne, whose knees are turned to one side, towards the bath from which she has just emerged, while her head is turned to the other, towards the old man who is assaulting her, seems to have been borrowed from de Troy by Vanloo. The reversal of right and left even suggests that Vanloo worked from an inverted engraving of J. F. de Troy's Suzanne .

The Suzanne of 1748, painted in Rome for Cardinal de La Rochefoucault to replace a Fuite de Loth judged too licentious, had been exhibited at the Salon of 1750; it is currently preserved at the Museo de Arte de Ponce. Although the format is different (95.6x126), several analogies with Vanloo's composition are also striking: Suzanne's right leg passed over the left, her hand pushing back an old man, the other's left arm extended and pointing to the background. This outstretched arm, in particular, betrays the borrowing: whereas in de Troy's work it unambiguously indicates the garden gate, from which a troublesome witness for Suzanne could emerge at any moment, in Vanloo's, who painted neither garden nor barrier in the background, the meaning of the gesture is lost. De Troy makes masterly use of the scenic device, with the differential play between the restricted space of the stage in the foreground, delimited by the factory, and the vague space of the garden in the background, where the small gate between the posts of which stands a tree designates the virtuality of the irruption of a gaze, the possibility at any moment of breaking the intimacy of the rape, of theatrically exploding and thus reducing the scandal of the brutality. Compare this with Le Rendez-vous à la fontaine (1723, London, Victoria and Albert Museum), where Suzanne's device is employed in a profane and even licentious context: the couple in intimate conversation by the fountain is opposed, behind the balustrade and from the garden, by the maid who comes to interrupt the banter and probably announce the husband's arrival. In Vanloo, this differential play disappears: we've seen how Diderot took advantage of this collapse to highlight the new economy of revolt.

Finally, let's mention the Suzanne of 1727, now in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Rouen. It was engraved in reverse by Laurent Cars, probably as early as 1731, which ensured a certain diffusion among artists and enthusiasts. Apart from the figure of Suzanne, extremely close to Vanloo's, the layout of the scene is quite different, more in line with the classical canon that Diderot will recall later: the two old men are placed on the same side, so that the balustrade for one, Suzanne's arm for the other, establishes the separation in the scenic space, the fundamental screen. The inquisitive old men, separated from Susanna, who has been delivered to their eyes, metaphorize the spectator's eye and act as visual clutches for the scene. Such a construction falls into Vanloo's composition, and in general as soon as the old men are arranged on either side of the young woman.

An academicized Suzanne

In any case, it's not without reason that Diderot first mentions de Troy when it comes to evoking other painters who have painted the same subject. The very neutral mention, incidental as it were, virtually covers up plagiarism, as if Vanloo had sought to synthesize J. F. de Troy's Suzanne. Diderot does not, however, take responsibility for an accusation; rather, he provides the elements of suspicion. After mentioning the painter, again under the false air of praise, the attack targets Suzanne's posture, i.e. the most blatant borrowing from de Troy:

"It is claimed that Susanna is academicized; could it be that her action is indeed somewhat primed, that the movements are a little too cadenced for a violent situation? Or could it be rather that the model is sometimes posed so well, that this study position can be successfully transported to the canvas, even though it is recognized? If there's a more violent action on the part of the old men, there may also be a more natural, truer action on the part of Susanna. But as it is, I'm happy with it, and if I had the misfortune to live in a palace, this piece might well move from the artist's studio to my gallery."

This term "académisée", which does not appear in any early dictionary, is in fact a neologism coined by Diderot. Littré quotes a passage from the Paradoxe sur le comédien, to which we'll return ; the Trésor de la langue française adds... the commentary on Vanloo's Suzanne. As for the Goncourt passages, they are probably themselves influenced by reading Diderot.

Yet Diderot doesn't speak for himself. He reports what is said in the Salon audience: "It is claimed that the Suzanne is academized". Forging a half-savory, half-ridiculous verb in this way is a matter of popular invention, or at least presents itself in the manner of a deformation, a popular recycling of the grand style. "Could it be that...? Diderot tries to understand this word heard in the crowd, and in so doing poses the problem of the encounter between the real and the ideal model.

The text thus reversed the point of view: whereas until then it had been a matter of criticizing the coldness of Vanloo's composition, as soon as this coldness is identified with an academicism on the part of the painter, Diderot takes its defense, and claims the natural simplicity of a pose that coincidentally joins the school exercise, at the antipodes of violent action and its theatricality[8].

The meeting of nature and code pleases. This pleasure in measure, in artifice rediscovered at the very heart of the theatrical excess of the stage prepares the major theses of the Paradox on the actor:

"But what?" one might say, these accents so plaintive, so painful, which this mother wrings from the depths of her bowels, and with which mine are so violently shaken, is it not actual feeling that produces them, is it not despair that inspires them? By no means; and the proof is that they are measured; that they are part of a system of declamation; that lower or higher by the twentieth part of a quarter-tone, they are false; that they are subject to a law of unity; that they are, as in harmony, prepared and saved; that they satisfy all the conditions required only by long study; that they contribute to the solution of a proposed problem; that to be pushed just, they have been repeated a hundred times, and that despite these frequent repetitions, they are still missed" (Colin 95; Vers 1383; DPV XX 55).

In these lines written in 1769, Diderot repeats the terms we noted in connection with La Chaste Suzanne: the agreement, the harmony that guarantee the homogeneous consistency, the effectiveness of the spectacle, are artifice, just as Suzanne's academic pose is artificial. The primary underlying model of artifice, then, is not an arrangement in space, but a certain regulation of song, a musicalization of the cry, of the accent: the scream of the mother at the death of her child, of the woman being raped in the solitude of a garden, must be cadenced, poetized, and therefore academicized, in order to produce their effect, that is, to communicate from gut to gut. A few pages later, the word returns under the pen of Diderot writing the Paradox, rare enough to constitute a quotation, a reference for its own sake, implicit, to the Suzanne:

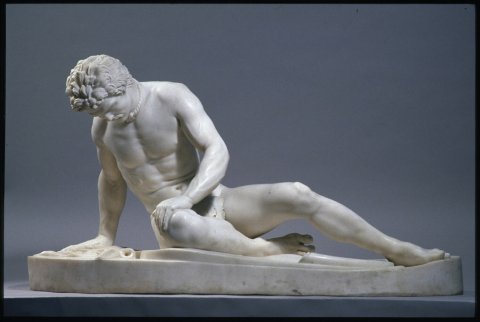

"We want man to retain the character of man, the dignity of his species, at the height of torment. What is the effect of this heroic effort? To distract from pain and temper it. [...] Who will fulfill our expectations? Will it be the athlete subjugated by pain and decomposed by sensibility? Or the academized athlete who possesses himself and practices the lessons of gymnastics as he breathes his last?" (Colin 104; Vers 1387; DPV XX 62.)

Artifice, the submission of gesture and voice to norms, to models, is not only commanded by an aesthetic requirement. The dignity of man is at stake: the problem is no longer the technical imitation of nature, nor even the immediate effect for the eye, but the symbolic, ideological foundation of representation.

Humanist representation cannot accept an aesthetic of disfigurement, even though, as we have seen, the new economy of the rebellious eye is fundamentally affirmed by and in the deconstruction of the figure.

Diderot's commentary is caught up in this contradiction: the demand for sensitive contagion, the new apprehension, tactile so to speak, of the pictorial thing as a raw thing of desire that the eye comes to knot, without distance, to the viewer's own libidinal economy, tend towards the disfiguration of figures, the decomposition of scenes, either in the exaltation of a sublime moment, or in the ferocious depreciation of a missed moment. But the step is never definitively taken: the old economy of the scene, with its figures, its arrangements, with the distance and reverence it institutes between the subject looking and the object being looked at, remains the reference model. Academized Suzanne is a humanized Suzanne, worthy of being looked at[9].

Less than a contradiction, it's more a case of back and forth. The superimposition of terror and norm, violent action and cadenced movement, offers this pleasure for the eye of a figure that unravels into a thing, and a thing that recomposes itself into a figure. Priming becomes natural, true posture meets Academy model[10].

III. Stage set-up

The scenic break-in

In fact, at both ends of the performance, disfigured as if academized, the character endangers the stage:

"If you lose the sense of the difference between the man who appears in company and the interested man who acts, the man who is alone, and the man who is watched, throw your brushes into the fire. You will academize, you will straighten, you will luff your figures." (Essais sur la peinture, IV, Vers 490; DPV XIV 377.)

This is the third and final occurrence of this strange verb academize. The academized figure emerges from the device; it is a figure in itself, which does not reflect the deformations necessarily engendered by a given situation, a given action: the man in company, the man we are looking at is not himself, he conforms to his social environment, unless, interested, absorbed by his action alone, he forgets those around him and behaves like the man who is alone. The academicized figure denies interaction and, thereby, risks coldness; it undoes the scene but saves the figure.

Now we understand that the entire commentary on Vanloo's Suzanne revolved around this problem of interaction, not only between the characters, but of the scene with the viewer. There is an autonomy to the figure, which presupposes an impassable obstacle between it and the viewer; but there is at the same time a dramatic effect of the figure, which commands that this obstacle be overcome and even abolished. Now, the iconographic tradition of the Suzanne provides a kind of epure of this device, which, with few variations, constitutes the basic device for all scenes - pictorial, theatrical, novelistic - in classical culture. Diderot uses two examples:

"An Italian painter has composed this subject very ingeniously. He has placed the two old men on the same side. Susanna wears all her drapery on this side, and to hide from the eyes of the old men, she gives herself over entirely to the eyes of the spectator. This composition is very free, and no one is hurt by it; it's that the obvious intention saves everything, and the viewer is never of the subject."

The Italian painter whose name Diderot does not give is, according to a hypothesis proposed by Else-Marie Bukdahl, Giuseppe Cesari, also known as the Chevalier d'Arpin (1560 or 1568-1640), otherwise famous as the author of the drawings from which the engravings in Cesare Ripa's Iconology are taken. Cesari had painted a Suzanne au bain which was, at the time Diderot was writing, in the Duc d'Orléans gallery in the Palais Royal. The painting has since disappeared, but is known from the collection of engravings that make up the catalog of this gallery, compiled from 1786 by Louis Abel de Bonafous, abbé de Fontenay[11].

The engraving, executed by Jacques Bouillard after Antoine Borel's drawing, corresponds to Diderot's summary description, except that it's not her drapery, but her hair that Suzanne interposes between herself and the two old men, placed "on the same side", behind the bath parapet. This hair, however, is so dense that Diderot may have mistaken it for drapery.

Cesari's Suzanne is a model of classical composition. As in almost all Suzanne scenes prior to the eighteenth century[12], a clear separation in space opposes on one side the two old men looking at Suzanne, on the other, in a space different from the one they are in, Suzanne looked at by them. Suzanne conceals her nudity from the inquisitive eyes of the perverse old men by the interposition of abundant hair, which characterizes her as a Madeleine, or even as Mary the Egyptian.

Through the intertwining of her arms and hair, Susanna evades the eyes of the old men, but surrenders herself to those of the viewers on the canvas, perfectly accomplishing the founding contradiction of the scenic device: the viewer looks at what he should not see, Susanna is delivered to him at the very moment she virtuously evades the eye of the old men, who nonetheless metaphorize the viewer on the canvas.

The space of the bath, delimited, circumscribed by the architectural factory against which Suzanne leans, constitutes the space of the scene proper, or restricted space: the column bases against which Suzanne leans in Cesari, and even the vegetation that invades the stone, are reminiscent of Vanloo's column bases. The water fountain missing from the 1765 canvas faces Cesari's Suzanne.

The architecture alone circumscribes the figure of the young woman: the intimate space of the Bath is delimited at the back by a parapet adorned with a bas-relief, in front by the ledge under which the water flows. This space is the space of the scene itself, a restricted space towards which gazes converge, the perverse gaze of the old men and the supposedly virtuous gaze of the viewer.

.Behind the factory, on the right, the painting offers the eye the opening of a sky and the vagueness of a garden. This is where the old men are, in this space of strolling and indeterminacy, a vague space, from which the focal object of the representation, the scene itself, is viewed.

The parapet: a screen that divides the space of representation

Between these two spaces, the vague space where the old men are and the restricted space where Suzanne is, a parapet carved with a bas-relief redoubles in stone the screen of hair interposed by Suzanne. Just above Susanna's calf, the bas-relief shows a woman kneeling at the feet of a young man (hairless) who is advancing, arms outstretched towards a group of bearded men in deep discussion: one of them raises his arm to attest to Heaven. It's not impossible that the bas-relief represents Suzanne's judgment and young Daniel's intervention, i.e. the narrative continuation of the scene.

What's certain, in any case, is that this low wall, which spatially materializes the prohibition of gaze (the old men are behind the low wall because they're not allowed to look at Suzanne naked), is itself the object and support of a representation, in defiance of all verisimilitude. Almost all classical Suzanne include, in the absence of this kind of bas-relief, a statue, vase or carved basin, hardly compatible with Suzanne's rigorous Judaism. In this scene, which tells us not to look at it, painting puts itself in abyss as art. The screen of representation makes the image happen all the same, that is, it poses a ban and then circumvents it.

Suzanne's quarter-turn

In Cesari's work, this circumvention is very materially sensitive. Suzanne turns around, performing the quarter-turn on herself that steals her away from the old men and delivers her to the painting's viewer. It is thus by chance that she meets our gaze in passing. The eye must grasp the device in this pivot that moralizes it: the old men could see but no longer see this nudity; we see it but were not supposed to. Effraction, then, is not simply the eye's penetration of the forbidden, restricted space of the stage; it is based on a temporality of painting: we enter and leave it; we are there and have never been.

.Through this temporality, painting constitutes itself as discourse: Cesari paints us the discourse of the old men: curiously, they are not looking at Suzanne; they have stopped looking at her; the one in front has turned to the one behind, he is still pointing at the young woman, but eye to eye they are both all in their commentary. The entire painting represents the old men's detailing of Susanna's beauties, their praise, their ekphrasis. The painting is constituted as a sign, according to the classical structure modeled by Saussure: at the top, the signifier, the old men's speech; then the semiotic cut, the parapet, the screen; at the bottom, Suzanne's diverted body, the signified of the discourse enunciated at the top. What referent does this sign refer to? Facing Suzanne, water gushes out of the fountain, from a monstrous and as if disfigured mouth: the real of desire is the jet.

The scene as a deconstruction of narrative

The second painting mentioned, by Sébastien Bourdon, which was at Baron d'Holbach's home, is not as favored by Diderot:

"Since I've seen this Suzanne by Vanloo, I can no longer look at the one by our friend Baron d'Holbach. It is, however, by Bourdon."

A Suzanne by Bourdon is indeed mentioned at no. 23 of the Catalogue de tableaux des trois écoles formant le cabinet de M. le baron d'Holbach drawn up on the occasion of the sale of March 16, 1789. This is probably the same painting that reappears at the Solirène sale in Paris, March 11-13, 1812, no. 6. Presented at the Trésors d'art de la Provence exhibition, Marseille, 1861, it was then owned by the Baroness Du Laurent. On November 7, 1916, it was sold in Marseille. It reappeared at the Heim-Gairac gallery in Paris, then lost its trace, perhaps in a private American collection.

As far as we can tell from the snapshot we have, this is a very fine painting. If Diderot rejects it, it's not for its intrinsic artistic qualities, but because it no longer corresponds to the canons of the scenic device whose room for maneuver he established, from Cesari to Vanloo, from the cut and distance of a sign scene to the pressure, to the sensitive continuity of a convulsion scene.

Sébastien Bourdon's Suzanne certainly features the thwarted movement of the young woman, turned forward to exit the Bath, then turned back to escape the grip of the old men who lay hands on her nakedness. The old men are both on the same side, leaning forward towards the object of their desire, but no parapet separates them from the young woman. Behind them, tied to a tall statue of a man, a large drapery is stretched out, meant to shelter naked Suzanne from prying eyes coming from the garden. It delimits the limited space of the scene, beyond which, on the left, we can make out foliage, a monumental gate and two upturned women, undoubtedly the two servants whom Suzanne has sent to fetch oil in town. Sébastien Bourdon has condensed the story, but retained its elements. The garden should be deserted by the time the old men approach Suzanne. The two women act as visual clutches from the vague space to the restricted space, but at the same time constitute a relic of the old, pre-scenic narrative organization of the performance, where the succession of episodes was materialized by the juxtaposition of spaces.

Notes

For example, by defining it as the interaction of characters under the gaze of a third party, whereas this interaction is tending to disappear and the third-party gaze is in the process of changing.

"Bayle, often as reprehensible and as small, when dealing with points of history and world affairs, as he is judicious and profound when he wields dialectic, begins his article on Henri IV by saying that, "if he had been made a eunuch, he could have erased the glory of the Alexanders and Caesars". These are things he should have erased from his dictionary. His very dialectic is lacking in this ridiculous supposition: for Caesar was far more debauched than Henry IV was in love, and it is hard to see why Henry IV would have gone further than Alexander. Has Bayle claimed that one must be half a man to be a great man?" (Voltaire, Essai sur les mœurs, chap. CLXXIV, ed. R. Pomeau, Garnier, t. II, p. 528.)

Similarly, Diderot reproaches Adam, for his sculpture of Ulysses and Polyphemus, for giving us "a sack of nuts for an Ulysses" (Salon of 1765, Vers 453). In Hallé's Allegie de la paix, "Ces échevins ne sont que des sacs de laine; ou des colosses ridicules de crème fouettée" (Salon de 1767, Vers 536); and Diderot returns to it further: "A ces foutus sacs rouges, noirs, emperruqués, en bas de soie bien tirés, bien roulés sur le genou, en rabats, en souliers à talon, substituez-moi de graves personnages à longues barbes, à têtes, bras et jambes nus, à poitrines découvertes, en longues, fluentes et larges robes consulaires" (Vers 692). As for Baudouin's Coucher de la mariée: "le mari vu par le dos a l'air d'un sac sous lequel on ne ressent rien; sa robe de chambre l'emmaillote" (Salon de 1767, Vers 670).

"a large garment [...] under which nothing can be seen" can be compared to the "bag under which nothing can be felt" in Le Coucher de la mariée, i.e. under which the features of a body cannot be guessed, or rather under which there is no body to feel sexual arousal. Similarly, Ulysses' sack immediately follows a joke about the name of the painter Adam, first husband, and cuckolded husband. As for Hallé's aldermen, they're foutus sacs, suggesting passive homosexuality. (Text references in previous note.)

Giambattista Tiepolo, Christ and the Adulteress, oil on canvas, 77x127 cm, Marseille, Musée des Beaux-Arts, 1752-1753.

Nicolas Poussin, Le Christ et la femme adulère, oil on canvas, 121x95 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre, 1653.

The three paintings by J. F. de Troy discussed below are signed and dated.

We have seen, in the commentary on Greuze's Accordée de village, the same contradiction developed, regarding the arrangement of the figures: "How they go undulating and pyramiding! I don't care about these conditions; however, when they meet in a piece of painting by chance, without the painter having had the thought of introducing them, without him having sacrificed anything to them, they please me." (Verse 232; DPV XIII 266-267.)

The contradiction erupts, for example, in connection with La Naissance de Vénus by Briard, in the Salon of 1769. Diderot first writes: "Miséricorde! quel ventre! quelle hanche! et l'énorme derrière et les cuisses exostosées d'une autre figure de femme posée sur des nuages qui avaient la complaisance de la porter!" (Vers 861; DPV XVI 634.) We're in the midst of disfigurement. But Diderot, who annotated a booklet on the spot at the Salon, then took his notes home, inadvertently did the job twice for Briard: two booklets were annotated at two different times, and with two contradictory judgments, hence this remark a few pages later in the Lépicié article: "Reread the lines above on Briard's la Naissance de Vénus, I say the devil with it; that's the judgment of one of my booklets, and here's the judgment of another of my booklets: "Quite pleasant, though the composition is arranged; the Venus of a rather fine drawing..." D'un dessin assez fin! That's what confuses me, because that's what it says, and I'm not mistaken. Then it says: "But with an academic and sophisticated attitude...". And then have some confidence in my knowledge of art and preach to me, if you dare, to publish my reflections. However, I must explain to you the very real contradiction between these two judgments: there was one point of view under which Briard's Venus had all the faults I reproach it with, and another point of view under which it no longer had them. So was this figure good or bad? Well, I don't know. (Vers 862; DPV XVI 637.) The figure's academicism saves it in extremis from disfigurement, as Vanloo's Suzanne is saved, by an ultimate reversal.

Diderot describes this virtual movement of disfiguration-refiguration in a digression from the Servandoni article where he reduces Glycon's Hercules, "killer of men" and "crusher of beasts" and at the same time exaggerates "a Mercury, some of those light, elegant, slender natures": "follow this ideal metamorphosis, until you have two reduced figures that resemble each other perfectly, and you will meet the proportions of the Antinous. " (Salon of 1765, Vers 351; DPV XIV 127.)

Galerie du Palais Royal gravé d'après les tableaux des differentes ecoles qui la composent : avec un abrégé de la vie des peintres & une description historique de chaque tableau, Paris, Couché et Bouilliard, 1786-1808, Bnf, département des Imprimés, cotes V-292 to V-294.

With the two old men on the same side, we can cite among many others Lorenzo Lotto's Suzanne, 1517, Florence, Uffizi; Julius Romano's fresco in the Palazzo del Te in Mantua, 1525 ; the painting by Tintoretto, 1555, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum; the one by Louis Carrache (1555-1619), formerly kept with the Cesari in the Duc d'Orléans gallery; the one by Dominiquin, 1603, Rome, Galerie Doria Pamphilj; the first version by Rembrandt, 1636-1647, The Hague, Mauritshuis; the canvas by Jean-Baptiste Santerre, 1704, Paris, Musée du Louvre.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « S'agit-il d'une scène ? La Chaste Suzanne de Vanloo », supplément inédit à L'Œil révolté, J. Chambon, 2007.

Diderot

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Diderot

Les Salons

L'institution des Salons

Peindre la scène : Diderot au Salon (année 2022)

Les Salons de Diderot, de l’ekphrasis au journal

Décrire l’image : Genèse de la critique d’art dans les Salons de Diderot

Le problème de la description dans les Salons de Diderot

La Russie de Leprince vue par Diderot

La jambe d’Hersé

De la figure à l’image

Les Essais sur la peinture

Atteinte et révolte : l'Antre de Platon

Les Salons de Diderot, ou la rhétorique détournée

Le technique contre l’idéal

Le prédicateur et le cadavre

Le commerce de la peinture dans les Salons de Diderot

Le modèle contre l'allégorie

Diderot, le goût de l’art

Peindre en philosophe

« Dans le moment qui précède l'explosion… »

Le goût de Diderot : une expérience du seuil

L'Œil révolté - La relation esthétique

S'agit-il d'une scène ? La Chaste Suzanne de Vanloo

Quand Diderot fait l'histoire d'une scène de genre

Diderot philosophe

Diderot, les premières années

Diderot, une pensée par l’image

Beauté aveugle et monstruosité sensible

La Lettre sur les sourds aux origines de la pensée

L’Encyclopédie, édition et subversion

Le décentrement matérialiste du champ des connaissances dans l’Encyclopédie

Le matérialisme biologique du Rêve de D'Alembert

Matérialisme et modélisation scientifique dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Incompréhensible et brutalité dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Discours du maître, image du bouffon, dispositif du dialogue

Du détachement à la révolte

Imagination chimique et poétique de l’après-texte

« Et l'auteur anonyme n'est pas un lâche… »

Histoire, procédure, vicissitude

Le temps comme refus de la refiguration

Sauver l'événement : Diderot, Ricœur, Derrida

Théâtre, roman, contes

La scène au salon : Le Fils naturel

Dispositif du Paradoxe

Dépréciation de la décoration : De la Poésie dramatique (1758)

Le Fils naturel, de la tragédie de l’inceste à l’imaginaire du continu

Parole, jouissance, révolte

La scène absente

Suzanne refuse de prononcer ses vœux

Gessner avec Diderot : les trois similitudes