for Marie-Thérèse Mathet1

" La jouissance de l'Autre n'est pas le signe de l'amour " : it's from this formula that Jacques Lacan enunciates and develops in Seminar XX Encore that we've attempted to articulate jouissance and love as part of our " psychoanalysis and culture " seminar. I suggested, however, that this articulation, which rests on extremely deep cultural foundations, described by Denis de Rougemont in L'Amour et l'occident, had undergone a profound mutation with the Enlightenment, which reshuffled the cards in the division between love and jouissance. While erotic jouissance and legal jouissance came to overlap and attempt to coincide, love aimed at another " other jouissance ", which was no longer the jouissance-knowledge of the Lady of fin amor, but the love-friendship of the confidence of belles âmes (Rousseau), an image of love in which the jouissance of the Other would be tamed, mastered, and even used.

It is this image of love that I propose to study here, insofar as the image is one of the forms that the sign of love can take, and undoubtedly the contemporary form it takes, coming to replace the classical, rhetorical forms of the discourse of love. Since love is no longer essentially the object of discourse, the stage plays an essential role as a medium for its representation as an image: in literature, it's the scene of the novel, whose emergence and generalization in the Age of Enlightenment is linked to the mutation I've just mentioned ; but psychoanalysis also mobilizes the scene, based on two notions: the traumatic scene on the one hand, and in its background the original scene (Urszene) that Freud identifies from his study of the case of the Wolf Man, scene repetition, or repetition compulsion on the other (Wiederholungzwang), whose fundamental scopic spring, which makes it a scene seen, Lacan identifies in Seminar XI on The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis.

In other words, the study of the signs of love, in literature as in psychoanalysis, requires an understanding of what a scene is, for the scene is what these signs, at least since the Enlightenment, are expressed, represented by. The difficulty lies in the polysemy of what we mean by a scene, between narratological or rhetorical form and traumatic, original or repeated form. In fact, these forms overlap very closely. This is what I propose to show by taking a literary example that has historically encountered Lacanian theorization in a spectacular way it's the example of Marguerite Duras's Ravissement de Lol V. Stein.

I. The scene of desire

On June 23, 1965, Lacan concluded his seminar by welcoming a talk by Michèle Montrelay, on Le Ravissement de Lol V Stein. Lacan has just become acquainted with the novel : " I was brought, at the last moment, a text on - you'll see - a book that seems to me very, very important. " At first, he doesn't give the title of " this book whose name I don't even know until she talks about it ". The words here are calculated : everything revolves around Lol's name, and what, in that name, bears the scar of a defloration, a rapture. The presentation by /// Mrs. Montrelay, a little slow, too scrupulous, is rather quickly jostled and interrupted by the impatient master, who condenses the essential elements in her eyes : the abbreviation of Lola as Lol, the loss of the a, then the central V, according to the American usage of the 2e first name of which only the initial is retained, finally Duras's practice of the " mot-trou ", which identifies the liminal traumatic scene - the casino ball at T. Beach, where her fiancé has gone off with another woman - to Lol's empty scene, to Lol herself, for whom this scene is empty, to the coincidence of the emptiness of the scene and the emptiness of Lol. Michèle Montrelay refers in particular to a passage at the beginning of the novel, where the narrator evokes Lol's impossibility of naming this ball scene, of formulating the word :

." I like to believe, as I do, that if Lol is silent in life it's because she believed, for the space of a flash, that this word could exist. Lacking its existence, she remains silent. It would have been a word-absence, a word-hole with a hole dug in its center, a hole where all other words would have been buried. [...] Missing, this word, it spoils all the others, contaminates them, it's also the dead dog on the beach at high noon, this hole of flesh. [...] oh ! how many there are, how many bloody incompletions along the horizons, piled up, and among them, this word, which doesn't exist, yet is there : [...] the eternity of the ball in Lol V. Stein's cinema. " (Folio, p. 48-49)

We note at the outset that this word is not a word in the ordinary sense of the term. Not so much because Lol can't name the ball that precipitated her shame and unhappiness, put words to a traumatic memory : but because this word, insistent in her because it doesn't exist, must at once manifest its presence-absence in a way other than verbal. A signifier of the absence of signifiers, at the edge of the unnameable and the named, it gives itself visual equivalents : a punctured dog on the beach, the flesh hole of the Origine du monde, the obscene display of an image.

In this use of the word, as a pure signifier of desire operating in discourse its hole, Lacan enthusiastically recognizes an essential dimension of his teaching and thereby, in Marguerite Duras an unexpected ally :

" There's something else in the text which is a text which seems... without either of us, Marguerite Duras and I, having done anything to meet... these are texts congruent with the very theme of what I've put forward to you this year. "

A text that seems what ? What is this other thing that manifests in the text something like a semblant ?

Michèle Montrelay insists on the desire for the other, which defines the Lacanian subject : and in fact Lol vide exists only through the desire of the other, not the other she desires, but her attachment to the desire that another bears for a third party, first Michael Richardson's desire for another woman, then, making up for this wound, the desire of Jacques Hold, the narrator and lover-type, the lover of her friend Tatiana Karl, whom she begs to continue enjoying the Other while he devotes the exclusivity of his love to her. Lol's ego recoiling from being supported by Jacques Hold's desire for the Other.

The fixation on the desire of the other, of which Lol V Stein's name constitutes something of an emblem, with what it presupposes of the work of lack in the constitution of the subject, constitutes the vulgate of what Le Ravissement de Lol V Stein illustrates, masterfully, of Lacanian theory. Yet Lacan sees something else.

As Michèle Montrelay has stated, Lola minus the a in her full name exists only in the form of a core object, the objet petit a of the other's desire. Now, in the previous seminar of 1964, the one Lacan was holding while Marguerite Duras was writing Le Ravissement, the objet petit a was identified with the gaze. Lacan recalls it in this June session /// 1965 :

" It is insofar as this being, this being designated by this proper name which is the title of Marguerite Duras's novel, this being is only really specified, embodied, presentified in her novel insofar as she exists in the form of this core object, this object(a), of this something which exists as a gaze but which is a gaze... a gaze apart, a gaze-object, a gaze which we see repeatedly...

This scene is renewed, chanted, repeated until the end of the novel : even when she has made the acquaintance of this man, when she has approached him, when she has literally clung to him, as if she were joining this divided subject of herself, the one that only she can bear, which is also in the novel the one that bears her, it is the narrative of this subject thanks to which she is present, the only subject here is this object, this isolated object this object by itself in a way exiled, proscribed, shunned, on the horizon of the fundamental scene, that is this pure gaze that is Lola Valérie Stein.

The name Lol V Stein is an interchange between two paradigms, that of the old Freudian psychoanalytic discourse, and its case narratives whose wounded desire supports the weft, and that to come of the new Lacanian topologies, with their mathemes and graphs. What Duras brings to Lacan is the literary formulation of this shift, starting with the word, towards a non-discursive, topological access to the subject, jouissance and love.

.The " bien autre chose " is this access, and its formula in the Durassian text is not so much the word-hole of the other's desire as the scene that organizes its repetition. "This scene is renewed, scandalized and repeated right up to the end of the novel&" which scene ? Is it the opening scene of the ball, a traumatic scene whose entire narrative can be read as the cure, the procedure for bringing back the memory, naming the event, dominating the suffering and emptiness it has left ?

But it's not the beginning of the novel that Lacan chooses to read in seminar on this June 23, 1965 it's the episode of Jacques Hold and Tatiana Karl's rendezvous at the Hôtel des Bois, a rendezvous that Lol spies from outside, from the rye field overlooked by the lovers' bedroom window.

There's only one scene at the ball, and from the outset, it's barred for performance. The rendezvous scene, on the other hand, repeats itself: in a way, for Lol, it does repeat the liminal traumatic event, but it installs it precisely within the framework of a repetition, a configuration, a topography that Lol can tame, that she will appropriate, of which she will ultimately be the ordainer.

Here we see two opposing conceptions of the novel scene, and with them two possible psychoanalytic modelizations : in the first, the ball scene triggers a narrative, a case narrative, the Freudian narrative par excellence ; in the second, the rendezvous scene configures a device, an arrangement of locations, a relationship between characters, a symbolic stake of domination. The stage device prepares the shift in Lacanian theory from signifiers to mathemes. Configuration takes precedence over narration, the objet petit a as a gaze over the objet petit a as the product of desire. More precisely, the configuration of Ravissement de Lol V Stein configures for Lol, through this repeating scene, a relation of jouissance between the characters and establishes, in favor of this relation, the paradoxical, final domination of Lol by love.

Lacan would publish the following December, for the Cahiers Renaud-Barrault, a " Hommage fait à Marguerite Duras, du ravissement de Lol V. Stein ". In it, he reformulates the same displacement. Ostensibly, Le Ravissement offers us a liminal scene, then the narrative of her recollection :

" The scene of which the entire novel is nothing but the recollection, it is /// properly the rapture of two in a dance that welds them together, and under the eyes of Lol, third, with the whole ball, to undergo there the abduction of her fiancé by the one who only had to suddenly appear. " (Other writings, p. 191)

This is the ordinary (and misleading) understanding of what a scene is : two characters interact, in this case Michael Richardson dancing with Anne-Marie Stretter, under the gaze of a third party, Lol. The event of the scene is the ravissement, the abduction of Lol's fiancé by this woman who has suddenly appeared, by this rival who has fallen from the sky, whom nobody was expecting.

.But very quickly, Lacan tells us that the real scene, the important scene, the one that is repeated throughout the novel, is not that, is not that :

" We'll think to follow some cliché, that she [that Lol] repeats the event. But take a closer look. It's to be seen in its entirety that it's recognizable in this lookout to which Lol will now return time and again, of a couple of lovers in whom she has found, as if by chance, a friend who was close to her before the tragedy, and assisted her at her very hour : Tatiana.

It's not the event, but a knot that is remade there. And it's what this knot encloses that properly delights, but then again, who ? "

Now here's a different understanding of what a scene is. In the repeated scene, unlike the liminal scene, the interaction between the two partners of the couple of lovers is not the constitutive core. The core is the lookout. Thinking of the scene as interaction implies identifying it with an event, and therefore with a narrative thinking of the scene as a lookout means inserting it into a logic of repetition, in which the gaze plays a central role. The scene doesn't arise it knots : it first ties a chance event (by chance, Lol found her old friend Tatiana in the street, by chance, Jacques Hold accompanied her, on whom she sets her heart2) to the primitive chance of trauma (by chance, Anne-Marie Stretter found herself at the casino ball at T. Beach casino ball). The knot here has nothing to do with a plot knot, with the unfolding of an Aristotelian mythos it's a chance superimposed on another chance, of identical configuration. The node pairs congruent configurations. Through this pairing, it brings the scene into a logic of device.

II. The empty scene

While Lacan was delighted to find in Le Ravissement confirmation of what he was orienting his teaching towards, the expressions of enthusiasm were hardly reciprocal Marguerite Duras had very little interest in psychoanalysis, and Lacan's midnight rendezvous with her in Saint-Germain-des-Prés did not lead to an exchange likely to nourish his work. The coincidence of Durasian practice of the stage in Le Ravissement with the theory of the gaze as objet petit a that Lacan was developing at the same time is an objective coincidence, without filiation : Duras worked from other models and for other ends.

To understand what role the scene plays in the Durassian poetic project, we need to return to the very literal, very practical understanding of the word in the narrative. The very term "scene" appears only four times in the text of the novel, and never to define the content of an event. The Durassian scene is a purely geometrical scene, that is, the delineation of a restricted space within a larger, vague space. The first occurrence is in the 3th chapter, which opens with a description of Lol's life after she marries Jean Bedford and they move into a big house in U. Bridge. In this house, where she is raising three daughters, Lol maintains meticulous order. According to an immutable timetable, she leaves in the afternoons, probably to take the children out, leaving the house in a state of calm. /// empty.

" Didn't the house, in the afternoon, in her absence, become the empty stage where the soliloquy of an absolute passion whose meaning escaped was played out? And wasn't it inevitable that sometimes Jean Bedford would be afraid ? " (p. 34)

The stage here is, in the etymological sense of the Greek skènè, the bare stage, the vacant trestle, the pure empty surface on which ordinarily the theater of life takes place. The house reveals itself as an empty stage when the whirlwind of family life is removed from it: the stage is what remains when the content of life disappears. We understand that these are the questions that Lol's husband, who works in an aircraft factory but is above all a musician (p. 29) asks himself: we'll see him later in the novel locking himself away in his bedroom (or office ?) to practice the violin3. Bedford is well-versed in listening to silence, and what can be played out musically.

In the silence that then settles in, he perceives " the soliloquy of an absolute passion ", the signifier of Lol's passion, a signifier she addresses to no one, a soliloquy, a signifier that signifies what is not, what has not taken place, what cannot constitute the fullness, the content of a scene. A signifier, then, whose meaning escapes not because we don't understand it, but because it is the signifier of the escape of meaning. This is why the empty scene, the receptacle that should hold signifier, becomes that signifier itself.

The next two occurrences of the word scene appear in the sequence where Lol spies on Jacques Hold's rendezvous with Tatiana Karl at the Hôtel des Bois. But " scène " does not refer to this sequence : here too, it refers to the reception surface, the support for the performance. On the rectangle of the stage, an event will occur, the object of the watch will appear.

" Eyes riveted to the lit window, a woman [= Lol] hears the void - feeding, devouring this non-existent, invisible spectacle, the light of a room where others are.

From afar, with fairy fingers, the memory of a certain memory passes. She brushes past Lol soon after she lies down in the field, she shows him at that late hour of the evening, in the rye field, this woman looking at a small rectangular window, a narrow scene, bounded like a stone, where no character has yet shown himself. " (p. 63)

Scene and spectacle are clearly dissociated : the stage is the surface, or field of light, where a spectacle could be projected, added. But there is no show. Or rather, the spectacle offered by the empty stage is a non-existent, invisible spectacle, reflecting the emptiness of U.'s house. Bridge's house in the afternoon, without Lol, to an inexistent, invisible first, to the repressed memory of the empty dance floor at T. Beach's Casino, deserted by Michael Richardson who left with Anne-Marie Stretter.

This time, however, the model for this empty stage is not the theatrical trestle of the skènè, but the cinematic screen, which draws a rectangle of light4. But the principle is the same : the stage exposes the device of representation, reveals its geometrical foundation, through the negation, the suppression of the contents it could accommodate.

Here, it's " champ " that has a double meaning, just as, in the previous quotation, " se jouait " was understood both as " était en jeu " and as an empty score that would be performed, i.e. as a game of the symbolic and a game of the real. The " field " in which Lol finds herself is the field of rye that stretches out behind the Hôtel des Bois, and the field of the cinematic device, from which, by turning the camera, the text gives to /// The field of rye, from which Lol delimits what is to be seen, orders the geometrical field of the real. The field of rye, from which Lol delimits what is to be seen, orders the geometrical field of the real ; the counter-field of the lit room conceals the symbolic content of the scene, where the image of love is produced the play of field and counter-field, finally, articulates in the imaginary register the scopic functioning of the device.

.At stake is " the memory of a certain memory ", which passes through the counter-field of the luminous scene, on the screen of the cinema Lol is making for herself, in the rectangle of the illuminated window, which passes from afar with fairy fingers, i.e., it barely grazes the scene, it barely flushes its surface, it sustains itself from its invisibility alone. The content of the scene, this memory of T. Beach's casino ball, only manifests itself from a scene absolutely devoid of content, in this case from a totally emptied field of cinematic projection light.

In the empty scene, any manifestation of content screens the fundamental void, comes to intercept the essential signifier of the absence of signifier :

" Tatiana Karl, in turn, naked in her black hair, crosses the stage of light, slowly. Perhaps it's in Lol's rectangle of vision that she stops. She turns towards the back where the man must be.

The window is small and Lol must only see the lovers' bust cut off at belly height. So she doesn't see the end of Tatiana's hair.

At this distance, when they talk, she can't hear. She sees only the movement of their faces, which have become the same as the movement of a body part, disenchanted. They speak little. And even then, she only sees them when they pass near the back of the room behind the window." (p. 64)

Tatiana passing in front of the window does not deliver the content of the scene : she screens its fundamental absence of content. An interposed figure in the Platonic cavern, Tatiana is a black stain her black hair does not circumscribe itself as an object as hair itself it remains unfinished, cut off, referring back to an incomplete image, what's more a mute image whose sound has been lost with the distance.

What Lol sees is placed under the seal of restriction : " Lol must only see... ", " So she doesn't see the end... ", " She only sees the movement ", " And still she only sees them ". A " ne... que... " bars her seeing, this " ne... que... " verbally translated, echoes in the text the interface, or coincidence, of image and screen in the device of representation.

The device is illuminated by Lacan's modeling of it during the March 4 and 11, 1964 sessions of his seminar on The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis.

To the left, in the hotel, is the object of representation, whose fragmentary, crossed-out image, the scene in the window, is delivered to us from the geometrical point that Lol constitutes at the bottom of the rye field. Here we have a first triangle, whose vertex is Lol and whose base is the room. Lol sees the room, but in the room she sees only an empty scene.

A second triangle is superimposed on this first triangle, arranged in the opposite direction: its apex is the point of light at the back of the room, which is intercepted by the black shape of Tatiana and her hair. Vaguely, the light of the room illuminates Lol, who, lying in the rye, spying or asleep, creates a tableau. Lol paints a picture from the bedroom; she paints a picture for Jacques Hold, who potentially looks at her, could look at her, and in subsequent repetitions of this scene will look at her. But more fundamentally, more essentially, the room looks at Lol, it looks at her, the room is the id, the vague memory of an id, /// who looks at her.

The superimposition of the two triangles constitutes the stage-breaking device that installs one opposite the other (but precisely not face to face) on the left a gaze, the gaze of the room, that looks at Lol, and on the right the subject of the representation, Lol in the field of rye, neanized by the gaze of the stage. Between the room and Lol stands the image-screen of the scene, a dazzling rectangle of light on one side, Tatiana's black hair, cut, unfinished, on the other.

The device does not, however, confront a gaze with a subject, Jacques Hold with Lol V Stein. The screen-image is not a semiotic bar, but a copula of being, or more precisely of the lack of being represented by the scene: the subject lacks being, the gaze that the empty scene places not in front of him (the window in front of Lol), but in him crossed out (the scene is Lol, insofar as Lol is defined by this lack of being of the empty scene). Or, in other words, the gaze (of Jacques Hold, of the room) is the lack-to-be, signified by the screen-image, of the subject of representation (Lol).

The last occurrence of the word " scene " in Le Ravissement appears during the pilgrimage that Lol, accompanied by Jacques Hold, makes, ten years after the fateful ball, to the T. Beach Casino. It's afternoon, the casino is deserted, yet the guard agrees to open the room to them, which Marguerite Duras has humorously named " La Potinière " : vanity of everyday speech, pure noise of the signifier that means nothing.

" We enter. The man lets go of the curtain. We find ourselves in a rather large room. Concentrated tables surround a dance floor. On one side is a stage enclosed by red curtains, on the other a walkway lined with green plants. A table covered with a white tablecloth is there, narrow and long. " (p. 180)

The stage here designates, as in the first occurrence, the vacant space of the game, the space where the music is played, at the end of the dance floor. A second curtain separates the dance floor from the stage, following the layout of the biblical tabernacle. The stage is the Holy of Holies, set back from the Holy of the dance floor. During the ball sequence at the beginning of the novel, the stage is never mentioned, but the orchestra occupying it is, on two occasions. The narrator explains where, in his story, he takes Lol's character:

" So I go looking for her, I take her, right where I think I should, at the moment when she seems to me to be starting to move to come and meet me, at the precise moment when the last comers, two women, walk through the door of the T. Beach Municipal Casino ballroom.

The orchestra stopped playing. A dance was ending.

The dance floor had slowly emptied. It was empty. " (p. 14-15)

and

" No doubt Lol, like Tatiana, like them, had not yet taken heed of this other aspect of things : their end with the day.

The orchestra stopped playing. The ball appeared almost empty. Only a few couples remained, including their own and, behind the green plants, Lol and that other young girl, Tatiana Karl. They hadn't noticed that the orchestra had stopped playing : at the moment when it should have resumed, like automatons, they had joined in, not hearing that there was no more music. " (p. 20)

The ball sequence opens and closes with this indication that the orchestra stops playing. Lol behind the green plants at one end of the track faces the mute orchestra at the other. Between the two, the dance floor becomes an image and a screen, with the appearance of the two spectres of Anne-Marie Stretter and her mother (" the emblems of an obscure negation of nature ", " this abandoned, bending grace of a dead bird ", p. 15), followed by the mechanical dance of the automaton couple formed by the hypnotic morte /// and Michael Richardson bewitched5. One thinks here of the ball given by Professor Spallanzani in Hoffmann's L'Homme au sable : Nathanaël dances with Olympia without realizing that he is only dealing with an automaton.

" The concert was over, the ball began. Dancing with her !... with her ! For Nathanaël, this was now the goal of all his desires, all his ambition... But how could he be bold enough to invite her, the queen of the party ? However, without knowing himself how it was done, the dance had barely begun, and he wriggled close to Olympia, who had not yet been engaged, and had already seized her hand, stammering out a few words. Colder than ice was Olympia's hand. Nathanael felt the horrible cold of death run through his limbs he fixed his eyes on Olympia's, which answered him, radiant, full of love and longing... " (E. T. A. Hoffmann, L'Homme au sable, Contes nocturnes, trans. Madeleine Laval, Phébus, coll. Verso, 1979, p. 48)

In Hoffmann, the mocking gaze of the student spectators of this ridiculous dance with a puppet is sovereignly ignored by love-struck Nathanaël. In Duras, Lol's gaze is the only thing that counts, in the face of the realization that there's nothing to see. It's not simply a matter of a change of focus: even when Michaël Richardson dances with Anne-Marie Stretter, the dance floor is empty, devoid of events.

III. The other scene

This empty stage that the text complacently waves before us speaks of the collapse of classical representational devices, the end of the novel scene as it was constituted in our culture, starting with the Italian invention of linear perspective and the generalization of the theatrical paradigm in the arts. At this point, there is no longer a stage in the literary sense of the term, and it is on this bare ground that psychoanalysis recognizes the configurations of the analytic stage, grasped not as representation, but as repetition, not as dramatic condensation, but as the obviousness of the drama, through which the schize of the subject is expressed.

We thus understand what psychoanalysis can do with the Durassian empty scene. But we have yet to grasp the literary project in which this collapse is inscribed. To grasp it, we need to move away from the alternative of structuring from the original scene or structuring from the repeated scene, where the previous models that Duras overturns are exhausted. What Le Ravissement aims at is, for Lol, the attainment of satisfaction. Here, we must proceed with extreme caution, guarding against familiar scenarios, which Duras carefully avoids : the narrative does not aim at reparation, the restoration of a subject in its plenitude, it is the implementation of neither a revenge, nor a cure. Something is repaired, but not the subject; satisfaction is achieved, but not subjectively. What's at stake, in an almost naive, childlike way, is the image of love.

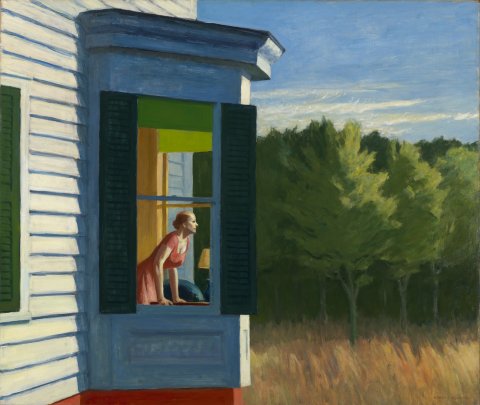

The image of love is carried by the romantic device of scenic effraction : the subject observes the intimacy of the lovers from behind the separating screen, experiencing its division in the face of the scandalous unity of the couple. This is Gianciotto Malatesta observing Paolo and Francesca (Ingres) ; Canon Fulbert surprising Heloise in the arms of Abelard (Kauffmann) King Mark arriving at the end of Tristan's song to Yseut (Leighton)6.

The point, in Le Ravissement, is to restore this device. The satisfaction of demand could be carried by this device from another age that persists there, in more or less cleverly cobbled-together forms. First, there's the hedge of green plants in the casino :

" Lol always remained where the event had found her when /// Anne-Marie Stretter had entered, behind the green plants of the bar. [...] When the mother discovered her child behind the green plants, a plaintive and tender modulation invaded the empty room. " (p. 20-21)

The screen of green plants shelters Lol's eye, but the event from which it should protect her collapses in front of it and fails to make a scene. This failed device will continue to try to reproduce itself, to fulfill itself. Thus, when Lol leaves her house for the first time after the scandal of the ball, and sees Jean Bedford by chance at night:

She's not the only one who's been in the dark.

" Jean Bedford was walking along the sidewalk. He was about a hundred yards from her - she'd just come out - she was still in front of her house. When she saw him, she hid behind a pillar of the gate. [...] Jean Bedford didn't see her come out; he thought she was a stroller afraid of him, of a man alone, so late at night. The boulevard was deserted.The figure was young, agile, and when he reached the gate he looked. " (p. 25)Lol's eye shelters behind the screen of the pillar, which repeats the screen of the green plants at the ball. This retreating eye beckons the gaze of the man who walks to meet her without seeing her. For this reason alone, this chance, this gaze somehow objectively, image-wise, repairs the loss of the ball, Lol marries her. Ten years later, back in S.Tahla, the same scenario is repeated: she sees a woman in the street, later identified as Tatiana Karl. The woman is in a relationship:

" The man with her had turned his head and looked at the freshly painted house, the small park where the gardeners were working. As soon as Lol had seen the couple approaching from the street, she had hidden behind a hedge and they hadn't seen her. The woman had looked back, but less insistently than the man, like someone who already knew. " (p. 38)Lol hides again to see a man watching, pointing his gaze towards her, towards the absent place of her being, this house that a few pages earlier Jean Bedford has designated as " the empty stage where the soliloquy of an absolute passion whose meaning escaped " was played out. Only a few words from Tatiana reach Lol: " Morte peut-être " : we grasp the neantizing dimension of the gaze and the need to shelter from it !

Then it's the narrator (we don't yet know it's Jacques Hold) who repeats the break-in :

" I saw, following her - posted hidden in front of her - that she sometimes smiled at certain faces, or so it seemed. " (p. 42)Through this reversal of point of view, Lol's angelic, slightly naïve smile is given to see, which is the sign of the love whose image she asks to restore.

The scene is empty : it doesn't necessarily call for an event. It simply posits a configuration that repeats and perfects :

" When it rained we knew around her that Lol was watching for lightning behind her bedroom windows. I think she must have found there, in the monotony of the rain, this elsewhere, uniform, bland and sublime, more adorable to her soul than any other moment of her present life, this elsewhere she had been looking for since her return to S. Tahla. " (p. 44)Expressed here is the pure form of the request, which is not addressed : a request for enlightenment, for a clearing of being, for a sublime elsewhere behind the bland screen of rain. Then Lol spies Jacques Hold and Tatiana at their rendezvous at the Hôtel des Bois (p.62) an imperfect formula, in which Lol does not control the chance of the encounter, which she has followed, but should not be able to reproduce, let alone control. On her return from the Hôtel des Bois, when it is already dark, Lol /// finds her husband in the street, alarmed. She then invents a lie:

" She told how she had had to go far from the center to make a purchase she could only make in the nurseries on the outskirts, plants for a hedge she had in mind, between the park and the street. " (p. 66)Lol's lie formulates the screen of representation, the regulating hedge between Lol's empty eye, safely installed in the house, and the inquisitive gaze of passers-by, random, circumstantial, the gaze of a desirable man who would turn on her (that's how she married Jean Bedford), the gaze above all of a couple who love each other (Jacques Hold and Tatiana), a couple who would offer her, from their sheltered vantage point, the image of love. In a way, it's this screen that Lol has gone to buy at the Hôtel des Bois rendezvous : her lie formulates a representation, a configuration surer, better ordered than that of the very scene it supplants.

In the next chapter, Lol experiments with the same device in a different way. From a wooded alley, she spies Tatiana's high-rise house, Tatiana sunning herself on her terrace (p. 68). She tries to tame the device, she seeks to master the mechanism of scenic break-in, to ensnare by it the chance of the encounter (the event of the scene) :

" Who knew ? Tatiana might come out, they'd meet like this, find each other like this seemingly by chance.That didn't happen. " (Ibid.)After this latest setback, Lol takes the lead, somehow forcing her way into her friend's home. There, Tatiana's husband, Pierre Beugner, expresses his unease :

" Pierre Beugner, once again, diverted the conversation, he was obviously the only one of the three of us who couldn't stand Lol's face when she talked about her youth, he started talking again, talking to her, about what ? the beauty of her garden, he had walked past it, what a good idea this hedge between the house and this busy street. " (p. 78)Pierre Beugner somehow plants the hedge, which hasn't been able to reasonably grow since Lol's lie, uttered a few days earlier7.... The hedge makes no sense in the logic of a realistic narrative; on the contrary, it revives for the reader the signal of Lol's lie, and recalls the screen device that floats across the narrative, like a machine that needs to be mastered, reappropriated. Pierre Beugner formulates what is at stake in Lol's visit, which he is the only one to understand it is not the reminiscence of the wound of T. Beach's ball, but the mastery of the screen that regulates its image, as an image of love, even if this mastery by Lol endangers Tatiana and ruins the balance she has established between her lover and her husband.

.Finally comes the invitation to Lol's home, and this is the great scene in which Lol takes control of the scenic device, passes to the side of the gaze :

" She has an opaque, soft gaze. This gaze that was for Tatiana falls on me : she catches sight of me behind the bay. " (p. 91)The bay replaces the hedge, the glass screen, which Lol controls, with the green screen of her impotence, which always brought her back to the derisory green plants of the liminal scenic collapse.

" She takes a few steps towards Tatiana, returns, lightly embraces her and, insensitively, leads her to the French window overlooking the park. She opens it. I understand. I walk along the wall. That's it. I stand at the corner of the house. So I can hear them. Suddenly, here are their intertwined voices, tender, in the nocturnal dilution, of a femininity similarly joined in me. I hear them. This is what Lol wanted" (p.92)Jacques Hold /// can't see the couple formed by the two women, whose voices alone produce the image of fusion in love. Lol seizes the image of love, which she shows off to Jacques Hold, beckoning him through the bay window, and then withdraws, forcing him to retreat to the corner of the house. Jacques Hold will be the unifying feature of Lol's fusion with Tatiana, and his affair will be Lol's instrument for ensuring her mastery of the stage-breaking device. Through this mastery, Lol gains access to jouissance, the other jouissance, purely feminine, which comes to inscribe itself in the vacant space of the empty stage, left empty by Michael Richardson's departure.

The narrator then notes this reversal, which makes Lol the heart and organizing principle of the scenic device, of which she had hitherto seemed the spectator and victim :

" Lol's approach doesn't exist. You can't get closer to her or further away. You have to wait until she comes for you, until she wants. She wants, I clearly understand, to be met by me in a certain space that she's creating at the moment. Which space? Is it populated by the ghosts of T. Beach, the sole survivor Tatiana, trapped in false pretenses, twenty women with Lol names? Is it otherwise ? " (p. 105)It's not simply a question of changing Lol's place in the stage set that she appropriates. By gaining control of it, she fundamentally alters its configuration. In the ballroom of T. Beach's casino, the bar with its curtain of green plants, the dance floor and the orchestra delimited a fixed space in which the respective positions were measured and evaluated. In her house, where Duras is careful to warn us that she maintains a maniacal order, Lol is constantly on the move, playing with a door she closes (isolating her husband), a bay window she interposes between herself and Jacques Hold, a French window she opens to drag and isolate Tatiana in the garden, a wall behind which she relegates the man she's caught in her clutches. Everything is in flux, and there is no longer any geometrically assignable stage space. Yet Lol imposes a stage space that is purely virtual, "a certain space that she is creating at the moment", an imaginary construction, through speech, with no territorial foundation. The ultimate evolution of the empty stage is deterritorialization.

.The time of the stage, too, is disrupted8. As we've said, it's neither the dramatic condensation of a pregnant moment, nor the obsessive repetition of a non-event. The new scene, introduced by Lol, deconstructs the event: it brings T. Beach's ghosts to life not as a memory, but as an advent, whose coherence and project the trapped narrator does not yet perceive, except that it involves an encounter with him, his integration into the device. Jacques Hold is to become the advent of T. Beach's ghosts, the connecting piece that will make the image of love torn apart and frustrated at the opening ball coincide with the image of love harvested, forced, artificially cobbled together by Lol's use of Jacques Hold's affair with Tatiana. What she " arranges in this moment ", the scenic moment that doesn't occur but that she configures, that she fabricates, thus superimposes the spectres of the past with the image that it's a question of producing, the image Lol has the project for.

Image of another scene to come, of a happiness encountered, or decided : image of love.

I'll conclude with a remark about Lol's character. My reading of her is not that of the drifting neurotic woman that critics generally propose. I've tried to show that Lol takes her image of love into her own hands. For all that, she doesn't "heal " she doesn't come back to any kind of love. /// of normalcy. This takeover is fundamentally perverse. It is this perversion that the stage, the empty Durassian stage that it uses as a truchement, encourages and nourishes. Strangely disquieting, the truchement of the Other's desire, of Jacques Hold's desire, establishes the image of love on the ruins of the stage that Lol, for him, has emptied.

.Notes

///1This work was the subject of a paper at the annual study day of the Société Internationale Marguerite Duras, Le Récit à la scène / la scène dans le récit , Université de Lille, September 30, 2020.

2P. 38.

3At the party Lol organizes, where she seduces Jacques Hold while Tatiana Karl looks on, Jean Bedford isolates himself and plays the violin : " Jean Bedford has retired to his room. He has a concert tomorrow. He needs violin practice " (p. 88) ; " We enter the salon. They are still silent. - Aren't you going to call Jean Bedford? Lol gets up, enters the vestibule, closes a door - the sound of the violin abruptly fades. " (p. 99) ; " The violin continues. No doubt Jean Bedfod is playing too, so he won't be with us tonight."(p. 101) ; " When I closed his office door Jean didn't even notice. "(p. 107).

4Compare with the passage on the word-hole, quoted above, evoking " the eternity of the ball in Lol V. Stein's cinema ". This inner cinema projects itself into the narrow scene of the window, but projects itself in hollow, in negative, in subtracted.

5See Marie-Thérèse Mathet, " Eros et Thanatos : la scène du bal dans Madame Bovary et dans Le Ravissement de Lol V. Stein ", La Scène. Littérature et arts visuels, L'Harmattan, 2001, p. 263-277. Marie-Thérèse Mathet identifies Anne-Marie Stretter, in her appearance at the ball, with the Lacanian Chose, purveyor of life and death (p. 274).

6We shouldn't be misled by the literary origin of these scenes, which is medieval. It is Romantic iconography that establishes the device as a scenic break-in device.

7" For the next few days, Lol searched for Tatiana Karl 's address" (p. 67), then " She delayed her visit to Tatiana Karl for two days" (p. 70).

8See S. Lojkine, " La scène et le spectre. Inventing the event, from the classical age to the end of the Enlightenment ", Synergie Pays Riverains de la Baltique, n°13, 2020, p. 85-107.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Duras, la scène vide » , Séminaire LIPS, automne 2021, université d'Aix-Marseille.

Littérature et Psychanalyse

Archive mise à jour depuis 2019

Littérature et Psychanalyse

Le Master LIPS

Séminaire Amour et Jouissance (2019-2021)

Amour et Jouissance

Jouir et Posséder

Vers l'amour-amitié

Les signifiants du désir

50 nuances de Grey

Duras, la scène vide