The emergence of technology (1761-1763)

Coussins

In the Salon of 1761, we can read this acerbic comment of a Adoration of the Kings1 not very successful:

There is a cushion in Parocel's Adoration that strangely shocks me. Tell me, please, how could a colored cushion have been in a stable, where misery gives us refuge, and where the breath of two animals warms a newborn against the harshness of the season? Apparently one of the kings had sent an advance cushion by his squire so that he could prostrate himself with greater convenience2. Artists are so attentive to technical beauty that they neglect all these impertinences when judging a production. Will we have to imitate them? and as long as the shadows and lights are right, the drawing is pure, the color is true, the characters are beautiful, will we be satisfied? (DPV XIII 258, Ver 2263.)

This "colored cushion", despite its ridiculousness completed in the Bethlehem stable, will be emulated. In the Salon of 1765, faced with Boucher's Angélique et Médor, Diderot reiterated the same assassinating remark:

Below Angélique imagine drapery, a cushion, a cushion, my friend! that goes there like the carpet of La Fontaine's Nicaise4. (DPV XIV 59, ver 311.)

Boucher arranges, beneath an ample drapery of old-pink satin, a cosseted boudin of green velvet, quite incompatible with the rusticity of the meeting place, the destitution of Médor left for dead on the battlefield, the simple apparatus of Angélique on the run, in love by chance or whim between three or four pursuers around the world5.

Diderot suggests from the outset, in fact, on the occasion of Parrocel, that these cushions are not a matter of the subject's intelligence; they escape the propriety of the scene; they claim a safe-conduct in the system of excluding implausibilities that governs, in all rigor, the composition of a painting. These cushions are not poetic; their "impertinence" is concerted: they are "technical beauties6", pertaining to pure painting and constituting a kind of gratuitous supplement to the story, offering the eye the color, the touch of their form, for an immediate and deliberately insignificant pleasure, a pleasure that would do away with the mediation of signs, a pleasure for the eye and without words, the pleasure of a cushion of metaleptic color, bringing the painted canvas back to its nature, its texture, its decorative and incongruous muteness.

If Diderot's revolt is so brutal against these innocent cushions that so sweetly furnish the improbable scenes of these worn-out stories, it's because what's at stake is not simply, circumstantially, stylistic: beyond the reprobation against rococo style is manifested here the emergence of a new relationship to painting, one that would do away with the ut pictura poesis. Diderot's attitude to this emergence is ambivalent: first, he fights it because it is the parallelism of the arts that legitimizes his posture as a salonnier, which is never that of an art critic (the term is foreign to him), but rather of a poet-painter among painter-poets; Diderot however at the same time recognizes this visual irreducibility of painting, and is gradually led to take into account the material of color, of which, outside of any poetic textuality, this visibility is made.

As incongruous as they were, Parrocel's and Boucher's cushions were still objects, assignable to a discourse, to a story, however silly: "Apparently one of the kings had sent a cushion in advance by his squire to be able to prostrate himself with greater convenience"; or Médor is another Nicaise, no longer the fiery soldier whose frolics made the great Roland lose his reason, but this draper's apprentice who, wanting to make his gallant rendezvous in the forest comfortable, made the lady lose her patience and miss the meeting.

The color

In the face of Vanloo's Grâces, however, in the Salon de 1763, however parodic and trivial, history falls away. Only the material of color remains, that unbearable green that revolts the Diderotian eye:

What can I tell you about the overall color of this piece? We wanted it strong, no doubt, and we made it unbearable. The sky is harsh. The terraces are as green as can be found anywhere. The artist can boast of possessing the secret of making a color that is of itself so soft that nature, which reserved blue for the heavens, has woven it into the mantle of the earth in spring, of making it, I say, a color to blind if it were in our countryside as strong as in his painting. You know I'm not exaggerating, and I defy the best eyesight to sustain this coloring for half an hour. I'll tell you of Vanloo's Grâces what I told you, two years ago7 of his Medea: it's a masterpiece of dyeing, and I don't think the praise of a good dyer would be that of a good colorist.

With all these shortcomings, I wouldn't be surprised if a painter said to me: What a beautiful eulogy I would give to all the beauties that are in this painting and that you don't see! There are so many things that depend on technique, and of which it is impossible to judge without having spent some time with one's thumb on the palette (DPV XIII 343, Ver 239.)

This green color, a true dyer's feat, does not strictly speaking characterize Vanloo's work, since it belongs on the contrary to "all those defects" to which a spectator who would be a painter would oppose "so many things that hold to technique", and which he would judge successful in these Graces. Yet this green that disgusts the eye prepares, in its very indecision, for the vagueness of "things that have to do with technique" and which, in their very technicality, fall outside the scope of any discourse, dissolve in the ellipsis of an unfinished sentence, are sent back to that skill of the "thumb passed through the palette", not the creative hand with the brush that paints, but the serving hand threaded, engulfed in pictorial matter. Technique is the anti-poetic remnant of painting, it is the unspeakable, the very matter of the visible, which no discourse, no poetics circumscribes.

To the natural green fabric woven by spring, Diderot contrasts Vanloo's blinding green, "a color to blind", and brings out the materiality of pictorial artifice, in contrast to the referential illusion, the fiction of the work ("This is how the good Homer imagined them, and how poetic tradition has transmitted them to us", DPV XIII 342, Ver 238). The harshness of the blue and green, the coarse, unbearable enormity of the colors, manifest themselves as a negative emergence of technique, a revolting but decisive emergence. Vanloo's hard sky and blinding green are the very matter of art, on which, dialogically, its technical beauties can be detached.

Harmony

It's with this in mind that, faced with Deshays' La Chasteté de Joseph, whose color alliances don't strike him as very happy8 Diderot launches into a digression on color:

Assemble confusedly objects of all kinds and colors, linen, fruit, liquors, paper, books, fabrics and animals, and you will see that air and light, those two universal harmonics, will tune them all, I don't know how, by imperceptible reflections. Everything will bind together, the disparities will weaken and your eye will not reproach the whole. The art of the musician who, by touching the perfect C chord on the organ, brings to your ear the dissonant C, E, G, C, G#, B, D, C, has come this far; that of the painter will never come this far. This is because the musician sends you the sounds themselves, and what the painter grinds on his palette is not flesh, blood, wool, sunlight, air from the atmosphere, but earth, plant juices, calcined bones, crushed stones, metallic limes. Hence the impossibility of rendering the imperceptible reflections of objects on one another; for him, colors are enemies that can never be reconciled. Hence the particular palette, a technique unique to each painter. (DPV XIII 372; Ver 259.)

Technique is the supplement to natural harmony9. It constitutes the painter's style only by default, because he is summoned to overcome the impossibilities consubstantial with pictorial matter: painters are obliged to have style, a "particular palette" because color is not given from the outset, but produced, and produced as it were randomly, by trial and error, at the mercy of a difficult transformation, impossible to totally master, of the raw materials. Unlike music, which directly produces sonic harmonies, pictorial harmony is metaphorical: it transposes into visual effect a long and uncertain chemistry of materials. Color emerges from matter, it is a quality produced by the encounter, action and reaction of ground and mixed products, it emerges as a supplement to chemical affinities10.

Technique and prescription

From the materials crushed on the palette so that the colors emerge, to the imperceptible reflections of objects on each other, whose linking, sequencing effect the painter's technique seeks to artificially restore, the subject shifts from a know-how to an intelligence of painting, from a problem of recipes to a problem of order. Technique becomes intellectualized:

What is technique? The art of saving a certain number of dissonances, of dodging difficulties superior to art. [...] Some objects win, others lose, and the great magic consists in getting very close to nature, and making everything lose or win proportionally. But then it's no longer the real, true scene that we see; it's just a translation, so to speak. Hence the hundred-to-one wager that a painting whose arrangement is rigorously prescribed to the artist will be bad, because it's tacitly asking him to suddenly form a new palette. In this respect, painting is like drama. The poet arranges his subject in relation to the scenes he feels he has the talent for, and from which he believes he can draw advantage11. Never would Racine have well filled the canvas of Horaces; never would Corneille have well filled the canvas of Phedre. (Continued from previous.)

There's a paradox of technique: the more it supplements those "imperceptible reflections" that nature introduces between objects, the more it manufactures harmony by altering colors to bind objects together, the further the painting moves away from the reality of things, substituting for "the real, true scene we see" a "translation", which is a stylistic coloring of reality, an artist's signature. Technical perfection demands a fundamental unrealism in painting.

From then on, it's no longer simply a matter of craft, of know-how, of the practical realization of an intellectually pre-formatted project: the technique, the painter's palette, decides the order, and the order, i.e. the very arrangement of the figures in the space of the painting, equivalent to the canvas of the play, comes under this project. Technique thus conditions the idea of the painting, its drawing, its canvas, its order: this conditioning certainly constitutes a reversal of the values posited by the ut pictura poesis, since it gives matter and color an intellectual dignity and forces us to think visually about painting; but at the same time, this newly acquired dignity of visual magic implies a poetic catching-up with technique: the painter grinds colors as Racine and Corneille fill the canvas of their play; the visual harmony of the canvas translates the real scene as the poet's style translates the thing simultaneously seen and globally felt. Technique thus becomes a matter of style, of harmony, of appropriateness; of writing, then...

The technical and the ideal: constructing a hermeneutic couple (1765)

The Salon of 1765 massively enshrines this integration by systematizing the opposition of the technical and the ideal, which becomes the basic opposition for thinking about and evaluating the process of artistic creation. In the article "Sculpture", at the end of Salon, Diderot writes:

Painting is divided into technique and ideal, and both are subdivided into portrait painting, genre painting and historical painting. Sculpture comprises much the same divisions (DPV XIV 286, Ver 444.)

Not only is this divisional thinking characteristic of the method of analysis instituted by Aristotle in the Poetics12, but by articulating the opposition of the technical and the ideal to the hierarchy of genres (portrait, genre, history), Diderot indisputably makes the technical-ideal pair the fundamental operative concept for thinking about a poetics of painting. Technique and ideal become the two exclusive criteria for judging the work:

A student who would put a price on such a daub would go neither to boarding school, nor to Rome13. We must abandon these subjects to the one who knows how to assert them by technique and by the ideal. (DPV XIV 74, Ver 320.)

Technique, the poor relation

Generally, Diderot deplores the lack of ideal, which technical qualities compensate for. Thus Carle Vanloo, Chardin, Vien:

Carle drew easily, quickly and greatly. He painted broadly; his coloring is vigorous and wise; much technique, little ideal. (Salon of 1765, eulogy of Carle Vanloo, DPV XIV 52, Ver 307.)

Middle ground: either interesting ideas, an original subject, or an amazing faire. The best would be to unite the two, and the piquant thought and the happy execution. If the sublime technique wasn't there, Chardin's ideal would be miserable. (Salon de 1765, article Bachelier, DPV XIV 111, Ver 342.)

Painting with no merit other than the technical... "But isn't it harmonious and from a spiritual brush?" [...] These are the words of the artists. Invincible about technique, which is everywhere; mute about the ideal, which is nowhere to be found." (Salon de 1767, article Vien, DPV XVI 114, Ver 550.)

But it's also sometimes the opposite, as with Deshays, or Fragonard:

Deshays had been conceived with the highest expectations, and he was missed. Vanloo had more technique, but he was not to be compared to Deshays for the ideal and genius part. (Salon de 1765, article Deshays, DPV XIV 104, Ver 337.)

The ideal part is sublime in this artist who lacks only a truer color and a technical perfection, which time and experience can give him. (Salon de 1765, Fragonard, Corésus et Callirhoé, DPV XIV 264, Ver 431.)

Certainly, the consideration of the technical on a par with the ideal in evaluating painting does not prevent the persistence of a negative apprehension. Quality, "the sublime of the technical", struggles to compensate for the prohibitive defect of the ideal, while technical imperfections are pointed out with indulgence when "the ideal and genius part" is present. Technique remains the poor relation of the pair14.

The fact remains, however, that the technique-ideal pairing imposes itself as a major structuring polarity for thinking poetically about painting, i.e. not only for evaluating it, but for understanding the process of its creation. Once this pairing is established, a subtle dialectic can be set in motion, aimed at overturning traditional hierarchies that attributed all prestige to the literary activity of composing the subject, and systematically deprecated on the one hand the work of matter to produce visual effects, and on the other the ordering of figures according to these same effects, for the eye therefore rather than for history.

.Revision in the division of genres

The polarization of critical discourse around the technical and the ideal and, through the establishment of this hermeneutic polarity, the dialectization of the technical and the reversal of the ideal constitute the central theoretical problematic of the Salon of 1765. The process can be seen, for example, in this passage from the Chardin article, which initially seems to corroborate the academic hierarchy of genres and confirm the cultural superiority of history painting:

I must, my friend, communicate to you an idea that comes to me and which perhaps would not come back to me at another time, is that this painting, which is called genre painting should be that of old men or of those born old; it requires only study and patience, no verve, little genius, hardly any poetry, much technique and truth, and then that's all. (DPV XIV 118, Ver 346.)

Remember that Diderot distinguishes only three genres of painting: history, genre and portraiture, so Chardin's still lifes fall into the category of genre painting, along with Greuze. Diderot himself would remark, in the Essais sur la peinture, that this categorization was absurd: "it was necessary to call genre painters the imitators of raw, dead nature; history painters, the imitators of sensitive, living nature" (DPV XIV 399, Ver 506). If Greuze is thus promoted to history painter, Chardin becomes the central model of genre painting.

Ideal and technique; history and genre; poetry and philosophy

Genre painting is painting in which the painter's technical talent is most exclusively deployed:

"it requires only study and patience, no verve, little genius, hardly any poetry, much technique and truth, and then, that's all" (Salon de 1765, article Chardin, DPV XIV 118, Ver 346).

On the other hand, history painting, which is also the painting of life and movement, requires verve, genius, poetry, all the qualities that contribute to the ideal part of painting, imagination of the subject and invention in its composition, i.e. in adapting the poetic subject to the pictorial support. To excel in technique is to be born old; genius, creative enthusiasm are all on the side of the ideal.

Then comes the reversal:

Or you know that the time when we set ourselves to what is called according to usage the search for truth, philosophy, is precisely the time when our temples turn gray and we would have bad grace to write a gallant letter. By the way, my friend, about those gray hairs, this morning I saw my head all silvered with them, and I cried out like Sophocles when Socrates asked him how love was going: A domino agresti et furioso profugi15 ; I escape the wild and furious master. " (Continued from previous.)

Old age becomes wisdom, the laborious experience of the years turns into philosophical practice, the very practice of Diderot resurrecting Sophocles in front of his mirror : Chardin, Diderot and Sophocles don't just practice their art; they reflect on it. The unfortunate impotence of old age is rethought as the congenital impotence of philosophy, that sublime childbirth sterility of Socrates who deliberately places himself outside, above the desiring circuit: the technique of art, its dead, impotent, inanimate part, is then revealed as the ideal of its ideal, the means of a self-reflexive return or overhang.

.Technique as disposition

At first glance, however, this philosophical revelation in the face of Chardin's still lifes seems to boil down to very little:

"I am amusing myself here chatting with you all the more willingly because I will tell you only one word about Chardin, and here it is: Choose his site, arrange on that site the objects as I indicate them to you, and be sure that you will have seen his paintings." (Continued from previous.)

No color here, no matter, but a simple arrangement of objects. The harmony of the composition is assumed, so to speak, and becomes transparent in the process: the materiality of technical means dissolves, is abolished in the magic of art, and only the sovereign gesture that presides over the order remains, this gesture by which the objects find themselves "posed on a kind of balustrade16", "scattered[s] on a table covered with a reddish carpet17", "a host of miscellaneous objects distributed in the most natural and picturesque manner18", i.e. contradictorily the most in keeping with nature and painting.

The arrangement becomes the supreme invention: Imagining is throwing a garland and placing a wine glass19. Objects triumph at the expense of the subject: piling up is the new logic of painting, display dethrones discourse; the show effect takes the place of history.

The new reign of objects deconstructs canvas composition in favor of order. Composition was the means of expressing the ideal: charged with implementing the theatrical rule of the three unities, composition was the centerpiece of the ut pictura poesis20. But the promotion of objects disseminates the pictorial scene and fragments the space of representation.

The technical flaw: dissemination and materialization

This dissemination, which radically disrupts the economy of classical painting, initially manifests itself negatively. Of Casanove's Une marche d'armée , Diderot writes:

Ah! if the technical part of this composition met the ideal part! If Vernet had painted the sky and the waters, Loutherbourg the castle and the rocks, and some other great master the figures! if all these objects placed on distinct planes had been lit and colored according to the distance of these planes! one would have to have seen this painting once in one's life; but unfortunately it lacks all the perfection it would have received from these different hands. It's a beautiful poem, well conceived, well conducted, and poorly written.

This painting is dark, it is dull, it is muted. The whole canvas offers you nothing but the various accidents of a great crust of burnt bread, and this is the effect of these great rocks, this great mass of stone raised in the center of the canvas, this marvelous wooden bridge, and this precious vault of stone destroyed and lost. There is no intelligence in the tones of color, no degradation of perspective; no air between objects, the eye is stopped and cannot wander. The objects in front have none of the vigor required by their sites. (DPV XIV 159,Ver 368-369.)

The technical assessment of the composition leads Diderot to divide the space of the painting into parts - sky and water, castle and rocks, figures - which he brings back, each time, to the specialist in the field, Vernet, Loutherbourg, some other great master. In this way, the critic produces a kind of perfect, but chimerical, heterogeneous virtual painting, from which to assess everything that the real painting lacks.

The technical criterion breaks down the canvas, deconstructs the subject, and substitutes an ordering of objects ("all these objects", "point d'air entre les objets", "les objets de devant") distributed according to planes ("placés sur des plans distincts", "selon la distance de ces plans"). The site then replaces the scene, just as objects replace figures. Site and objects characterize reality, not representation. It's in the real that objects are placed, and it's nature, not theater, that provides their site.

The ordinance controls the alteration of objects according to their position in the site: it is the ordinance that illuminates and colors them according to the distance of the planes, that determines the "intelligence in the tones of color", that scales the "perspective degradation". Order is what produces meaning in painting from technique: not the meaning of a story, but an intelligence of depth, an order of planes, an organization of space.

Or Casanove's painting, which promises so much in the ideal part, turns out to be technically flawed. Diderot immediately translates it into literary terms: "It's a beautiful poem, well conceived, well conducted, and badly written." Technique, as we have seen, is the style of painting, just as the ideal is to a painting what the canvas is to a play. The technical flaw translates into a flaw in color, a flaw in light: "This painting is dark, it is dull, it is deaf". The point is indeed stylistic, consistent with the ancient articulation of the technical and the ideal.

But immediately recalled, this articulation is reversed. "The whole canvas offers you nothing but the various accidents of a large crust of burnt bread": paradoxically, the technical flaw makes the technique visible, abolishes the transparency of the real to the represented, and recalls the viewer's eye to the materiality of painting. The crust of burnt bread is a very material characterization of the blistering of the colored paste on the canvas, its lumpy irregularity, which becomes noticeable when the referential illusion falls away and the scene unravels. From color and light, we then move on to a critique of order: the technical flaw affects the scenic unity of the painting; it breaks down a "poem" that cannot, as a result, have been properly "conceived".

The visionary ideal of technique

"These great rocks", "this great mass of stone raised in the center of the canvas", "this marvelous wooden bridge", "this precious stone vault" cease to produce their scenic effect, to provide the scene with "this infinite variety of actions". No more action, no more effect: all that remains is a collection of badly arranged, badly degraded objects:

The eye's proximity separates objects, its distance presses and confuses them. That's the A, B, C, which Casanove seems to have forgotten. But how, you may ask, did he forget here what he remembers so well elsewhere? Shall I answer as I feel? He will have opened his portfolios of prints, he will have skilfully fused three or four pieces of landscapes together, he will have made an admirable sketch; but when it comes to painting this sketch, the craft, the talent, the technique will have abandoned him. If he had seen the scene in nature or in his head, he would have seen it with its planes, its sky, its waters, its lights, the true colors, and he would have executed it. (DPV XIV 160, Ver 369.)

The technical defect was therefore merely a symptom, a consequence of plagiarism, i.e. the defect of invention. The tâcherone conception of a technicality that compiles, borrows from various models (precisely as Diderot had done in reporting this part of the painting to Vernet, that other to Loutherbourg), is now revoked. Only the ideal vision of the scene can give the painting its harmony, i.e. its technical unity. Vision and execution proceed from the same creative movement, which telescopes the painter's head and nature, the ideal model and the real site. Technique is abolished in this pure disposition, where the material of painting becomes transparent, becomes the very light and color of reality: but this abolition is a sublimation; it intellectualizes technique, identified henceforth with the installation of objects in nature, with the virtual circumscription of an order in reality. The ideal then manifests itself only secondarily, as a vision of what nature executes in the fiction that the canvas is merely this natural execution: the ideal becomes the ultimate dematerialization of the technical.

The poetic revolution of the visible (1767)

The Salon of 1765 consecrated the decisive hermeneutic function of the technique-ideal couple. This couple manifests itself at first as an unequal one, in which the technical is downgraded to the tricks of the painter's trade, while the ideal constitutes the noble poetic part, common to both painter and poet, and valued precisely because it legitimizes the ut pictura poesis. We have seen, however, how the promotion of this pairing, however unequal, prepares the revaluation of the technical and the reversal of its relationship with the ideal. This reappraisal involves the dematerialization of technique, which no longer executes a figurative composition, but virtually arranges and lightens an order of objects. Technique is the natural degradation of objects, in contact with one another, in the light naturally given to them by the site from which they are taken.

From then on, technique becomes vision, discursively incommunicable: the ordinance, through which this new technique essentially manifests itself, establishes a regime of visibility without words, unrelated to the means, the effects of poetry. The Salon of 1767 would take the measure of this emancipation of painting.

Leprince illustrating Saint-Lambert: technical impossibilities of painting

It all begins with an anecdote: Jean François de Saint-Lambert, the lover of Mme du Châtelet and Mme d'Houdetot, had asked Jean Baptiste Leprince to decorate his poem des Saisons with engravings21; Leprince complained to anyone who would listen about the impractical demands of his poet patron:

There are few men, even among people of letters, who know how to order a painting. Just ask Le Prince, commissioned by Mr de St Lambert, a man of wit, certainly if ever there was one, to compose the figures that are to decorate his poem Les Saisons. It's a host of fine ideas that can't be rendered, or that rendered would be without effect. They are either mad or ridiculous, or incompatible with the beauty of the technique. It would be passable, written; detestable, painted; and that's what my colleagues don't feel. They have in their heads, Ut pictura poesis erit; and they have no idea that it is even truer than ut poesis, pictura non erit. What does well in painting, always does well in poetry, but this is not reciprocal. (DPV XVI 150, Ver 573.)

Ut poesis pictura non erit : the hijacking of the formula carries a double revolution. On the one hand, painting dethrones poetry by becoming the subject of comparison; on the other, it becomes autonomous as a non-discursive art by negating the non erit. Admittedly, this revolution is first noted negatively: "What does well in painting, always does well in poetry; but this is not reciprocal." Painting can do less than poetry; it is its ineptitude that consecrates its specificity.

However, we also know that Diderot had little appreciation for Saint-Lambert's Saisons, despite his friendship with the author. In his Correspondance littéraire of April 15, 1767, he wrote:

But the worst, the original, irremediable vice, is the lack of verve and invention. There is no doubt some number, harmony, sentiment and sweet verses that one retains; but it is everywhere the same touch, the same number, a monotony that lulls you, a cold that wins you, an obscurity that depresses you, prosaic turns of phrase and from time to time flat and sullen ends of descriptions. (DPV XVIII 25.)

The "verve" and "invention" that Saint-Lambert lacks betray the defect of an ideal reduced to "fine ideas", while "number" (rhythm) and "harmony" constitute technical qualities. These fine ideas are "incompatible with the beauty of the technical": in essence, Leprince cannot agree with Saint Lambert because they both camp on technical conceptions of their art, which are therefore necessarily irreconcilable, since only the ideal allows circulation between text and image, which it conditions and overhangs.

.Virgil's Neptune: visionary ideal and intermedia circulation

For Diderot, the ideal remains the major mainspring of artistic creation, conceived as an intellectual creation, virtual therefore first and foremost. Yet, by emphasizing the work of art's regimes of visibility, technique shifts the ideal from history to vision, from the conception of the subject to the imagination of the device. The promotion of the technical thus inflects the very workings of the ideal

.I keep coming back to Virgil's Neptune, summa placidum caput extulit unda22. Let the most skilful artist, stopping strictly at the poet's image, show us this head so beautiful, so noble, so sublime in the Aeneid, and you will see its effect on canvas. On paper, there is no unity of time, place or action. There are no determined groups, no marked rests, no chiaroscuro, no magic of light, no intelligence of shadows, no tints, no halftones, no perspective, no planes. Imagination moves swiftly from image to image, its eye taking in everything at once. If it discerns planes, it neither gradates nor establishes them. Suddenly, it will go to immense distances. Suddenly, it will come back on itself with the same rapidity, and press objects onto you. It doesn't know what harmony, cadence, balance are; it piles up, it confuses, it moves, it approaches, it distances, it mixes, it colors as it pleases. (DPV XVI 150-151, Ver 573-574.)

Diderot had already evoked Neptune's head emerging from the waves at the end of the inaugural storm in the Eneid in the Lettre sur les sourds, then in the Essais sur la peinture and Le pour et le contre23. This Virgilian hieroglyph, this "admirable painting in a poem" is, according to Diderot, untranslatable on canvas, despite the example of Rubens. But it's not a question of opposing a textual logic, a verbal poeticity of the Virgilian passage, to the visual means of painting; the opposition is entirely organized within the visible, and in fact opposes two regimes of visibility, a virtual visibility of the text, governed by the eye of the imagination, and a material visibility of painting, controlled by the viewer's gaze on the canvas. In contact with the technicality of painting, it's not the ideal that gives up, but a poetics of regimes of visibility that asserts itself, opposing visibility on paper blackened with writing and visibility on canvas colored and impastoed with paint. If paper is more powerful than canvas, it's because, contrary to the prescriptions of Aristotle and his emulators, "on paper there is neither unity of time, nor unity of place, nor unity of action". The foundation of the ut pictura poesis shatters, or more precisely paradoxically survives only in the colonized territory of painting, whose technical constraints naturalize Aristotelian poetic prescriptions.

The poetic revolution: Mars and Venus

The poetic revolution taking shape here is based on a new imaginative visibility of the text, now mobile, fast, abrupt and free: in the parallel of the arts, this visibility alone can continue to guarantee the superiority of the poet over the painter, the best performance of the text over the painted or sculpted scene. It is now up to the poet to integrate the means of painting in advance, to think visually about his artistic creation, to create images directly, to order in a word, instead of composing. Leprince's difficulties in satisfying Saint-Lambert's demands are thus contrasted with the ease with which painters can execute what Diderot imagines. :

Chardin, La Grenée, Greuze and others assured me, and artists do not flatter literati, that I was almost the only one among them whose images could pass on canvas, almost as they were ordered in my head.

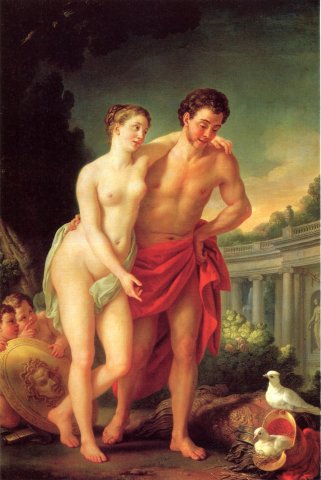

Lagrenée says to me, give me a subject for Peace, and I answer him; show me Mars covered in his cuirass, his loins girded with his sword, his head beautiful, noble, proud, disheveled. Place Venus standing at his side, but Venus naked, tall, divine, voluptuous; throw one of her arms gently around her lover's shoulders, and let her smile enchantingly at him, showing him the only piece of her armor she lacks, her helmet in which her pigeons have made their nest. I hear, says the painter; we'll see a few strands of straw coming out from under the female; the male sitting on the visor will stand sentry; and my picture will be done. (DPV XVI 152, Ver 574.)

Subtly, Diderot has substituted himself for Saint-Lambert, not to enslave painters to his technique, but to make up for the general lack of ideal, to become its universal purveyor, to revive the crisis-ridden economy of the ut pictura poesis.

Lagrenée asks him for an allegory, the most textual genre there is in painting, enslaved to a centuries-old syntax that reduces the image to a system of signs that are, so to speak, verbal. In Lagrenée's genre, Diderot proposes a Mars and Venus, but reversing the usual device: to the languid Mars, effeminate in the reels of desire inspired by the goddess, he opposes a furious Diomedes; to the reclining or seated Venus, inviting her lover to amorous consumption rather than to warlike enterprise, and feeding the warlike metaphor of love through her gesture of invitation, Diderot prefers a woman standing and dialoguing, an ironic interlocutor, a voluptuous philosopher.

From allegorical signs to scenic conflict

The image no longer makes a sign: the helmet with its nest designates neither war nor peace, but the conflict of interests, or even rather the conflict of desires, desire for military glory and desire for voluptuous love. The helmet is not a sign, but a scene: encamped at its edge, the sentinel male pigeon circumscribes its limits, which "a few strands of straw" would like to overflow, thus reversing the scene of the gods, in which the disheveled departure of Mars is circumscribed, circumscribed by the goddess's arm thrown limply around her lover's shoulders.

.The Diderotian order does not compose the allegory, whose traditional signs it destroys on the contrary: the lovers' love nest, a voluptuous bed in a divine palace or an improvised couche in a happy Arcadia, is projected into the laughable insignificance of a pair of pigeons, while the helmet disappears beneath the nesting. Venus's gesture leads the viewer's eye to this undone sign, where the chiasmus of visibilities24 is ordered: Venus left shows the pigeon kept by her pigeon, while the helmet assigned to a new use returns to its disheveled Mars. Likewise, the viewer attracted by Mars and Venus is deported to the scene of the helmet and nest, this helmet-nest whose circle makes an eye, whose ocelli looks at us tauntingly.

Diderot's project was realized, not by Lagrenée, but by Vien, in a painting commissioned in 1768 by Prince Galitsyne, bought in 1769 by Catherine II, and since preserved at the Hermitage. As for Lagrenée, he tried to work on the idea of pigeons nesting in Mars' helmet, but in a more traditional composition25 where Venus' diaper remains the central, classical scene of the composition, with its green theatrical curtain ajar for the viewer to break into, as if Vulcan were to appear and snare the adulterous couple. What is revolutionary in Diderot's prescription, executed (more or less skilfully) by Vien, is the lovers' walk, the conversation that this walk implies, and the identification of the dialogic back-and-forth with the back-and-forth of the gaze between gods and pigeons. Venus "shows him the only piece of her armor that is missing": she provides the extra gesture to designate the defect of a missing object, thus superimposing the two regimes of visibility, the ideal, deployed by the imagination but lacking in the real, and the technical, present in painting, but referring to the failure of signs.

Technical visibility and ideal visibility: the honest model

The painting imagined for Greuze achieves this same articulation of visibilities:

Greuze says to me, I would like to paint a woman naked, without wounding modesty; and I reply, make the model honest. Sit a naked girl in front of you; let her poor body lie on the ground beside her, indicating her misery; let her head rest on one of her hands; let two tears run down her beautiful cheeks from her downcast eyes; let her expression be one of innocence, modesty and modesty; let her mother be beside her; that she covers her face with her hands and one of her daughter's hands; or that she hides her face with her hands, and that her daughter's hand is resting on her shoulder; that this mother's clothing also announces extreme indigence; and that the artist witnessing this scene, moved and touched, drops his palette or pencil. And Greuze says, I see my painting. (Continued from previous.)

Greuze never painted this picture, but Baudouin executed it in gouache for the Salon of 1769. Indeed, Diderot recognized his project in it, since, addressing the young libertine painter who painted this Modèle honnête, he advises him, "Believe me, abandon these kinds of subjects to Greuze." (DPV XVI 623, Ver 855-856.)

Le Modèle honnête hijacks and popularizes Apelle painting Campaspe, Alexander's mistress, and falling in love with her, a classical history scene evoked by Pliny and often depicted since the 17th century (Winghe, Trevisani, Restout, Tiepolo, Gandolfi...). The classical scene represents the birth of desire in the painter, in the very gesture that creates the portrait. For Apelle, seeing, painting and desiring Campaspe proceed from the same movement, so that the scene speaks of the impulsive, scopic spring of creation, but also more generally of artistic consumption.

As Venus showed the missing helmet, Diderot's honest model "indicates her misery", designates, by "her poor remains" laid "on the ground beside her", the missing object of desire. The naked woman is barred by this lack, the mother (in Baudouin's case, the daughter) covering her face in the manner of Agamemnon in The Sacrifice of Iphigenia, stopping the painter's action, undoing desire, reversing the attraction of sex into tenderness. In the center of the painting, the lowered palette is the interposed eye, where the gaze converges, and from which the painting returns as a disappointment of desire and, in this disappointment, as a rebellious fulfillment: the viewer's eye embraces the painter's tenderized revolt against the social institution that precipitates the young girl into debauchery. The painter "drops his palette", but the thumb passed through the palette draws the erection of desire at the moment when the weapons are lowered. The device superimposes an ideal visibility, saturated with tenderized sensibility, and the revolted lack of a technical visibility, this body barred with indigent nudity, this woman without clothes, without gaze, without the possibility of desire.

The new ut pictura poesis: a poetics of the image

Why does Diderot verbally succeed in these images to paint? What is the tour de force by which he revives a faltering ut pictura poesis, threatened by the technical claim of the arts and by the erasure of the poetic mediations of representation, the compositional unity of the scene, the syntactic arrangement of figures, the convergence of effects towards the fulfillment of history?

This apparently comes from the fact that my imagination has long since subjugated itself to the true rules of art, by dint of watching its productions; that I have taken to arranging my figures in my head, as if they were on canvas; that perhaps I transport them there, and that it is on a large wall that I look, when I write ; that long ago, to judge whether a woman passing by is well or ill-fitting, I imagined her painted, and that little by little I saw attitudes, groups, passions, expressions, movement, depth, perspective, planes that art can accommodate; in a word, that the definition of a regulated imagination should be drawn from the ease with which the painter can make a beautiful picture of the thing that the litterateur has conceived. (DPV XVI 153, Ver 575.)

Diderot succeeds where Saint-Lambert failed, because he has turned the tables on the ut pictura poesis : it is now the image, with its regimes of visibility, and no longer the story, with the norms of its dramatization, that constitutes the common ground from which the arts exchange. The wall of visual projection on which Diderot gazes was prepared by the allegory of the Platonic cave in the Salon de 1765 : this wall undoes the stage, with all that it presupposed of discourse, even defeated, and history, even concentrated, arrested; the wall establishes the virtual visibility of the phantom image, of lack made image, as the poetic matrix from which to deploy the material, technical artifices of the order.

The painter then becomes a magician, competing with the Creator to order matter: he intellectually conceives his image, which is perfectly realized, in the illusion of a perfect, transparent technical interface. Matter is idea, idea is in matter. But paradoxically, just as the idea is about to triumph, matter disappears: the artist's virtual world competes with the real world, intending to take its place. Idealization of technique and virtualization of matter are the two faces of the new device of representation.

Notes

The collegiate church of Sainte-Marthe in Tarascon has two authenticated paintings by Charles Parrocel in its Saint-André chapel, Sainte Marie l'Égyptienne and Saint André, and an anonymous painting depicting L'Adoration des mages et des bergers, which may be the painting by Joseph François Parrocel exhibited at the 1761 Salon. There is a Adoration of the Shepherds and a Adoration of the Magi by Pierre Parrocel in the Chapelle Sainte-Cécile. The San-Francisco Museum of Fine Arts owns a series of engravings by Joseph Parrocel, including an Adoration of the Magi and two Adorations of the Shepherds (Achenbach Foundation).

This sentence is an addition by Grimm.

References to Diderot's Salons are given first in the edition of the Œuvres complètes published by Hermann, known as DPV, then in Laurent Versini's edition, published by Laffont, coll. "Bouquins", tome IV, abridged Ver. Diderot's text is that of DPV. Grimm's comments, which appear in neither DPV nor Ver, can be read in the Oxford Seznec edition or in the Lewinter edition of the Club français du livre.

Instead of satisfying his belle during their nocturnal rendezvous in the forest, Nicaise exclaims, "How damp it is here! / Hay, your habit will be spoiled. / It's beautiful: it would be a shame. / Suffer without further delay / That I go and fetch a carpet." (La Fontaine, Contes et nouvelles, III, "Nicaise", vv. 152-156, Pléiade, p. 751.)

L'Arioste, Roland furieux, chant XIX, stanzas 17 (Angelica's garment) and 20 (inamoramento).

On the appearance of the word "technique" in Diderot, which is not immediately substantivized, see J. Chouillet, La Formation des idées esthétiques de Diderot, Colin, 1973, pp. 348-352. J. Chouillet demonstrates, against Y. Belaval, that le technique is far from being systematically disparaged by Diderot: putting the Encyclopédie and the Salons into perspective proves this. J. Chouillet also recalls the novelty of the word, which appears laconically in the Dictionnaire de Trévoux in 1721; the definition is repeated without much change in the Encyclopédie; use of the word does not become habitual with Diderot until after 1763.

In fact four years ago, in the Salon de 1759: "C'est [...] un faste de couleur qu'on ne peut supporter." The error is corrected in the Vandeul and Saint-Petersburg copies (variants V and L). Criticism of color is recurrent. Diderot wrote of the following Vanloo in 1763: "The color of this piece is as harsh as the idea is sullen. All the bladders of a color merchant have been poured crudely over a space of four feet." (DPV XIII 345, Ver 240.) Similarly, in 1761, regarding an allegory by Hallé: "it's a children's hullabaloo. Huge canvas, and many colors." (DPV XIII 228, Ver 209.) And, again about Hallé, in 1765: "It looks like you've smeared this canvas with a cup of pistachio ice cream. If chance had produced this composition on the surface of the misty waters of a paper marbler, I would be surprised, but it would be because of chance." (DPV XIV 73, Ver 320.) This criticism of color debauchery disappears, however, from 1765, when color, considered as matter, becomes a positive category. See infra.

"You may tell me that [...] the red carpet that covers this end of the toilet is hard; that this yellow drapery on which the woman has one of her hands pressed, is raw, imitates bark" (DPV XIII 371; Ver 258)

Jacques Chouillet points out that the expression "universal harmonics" recalls the title of Father Mersenne's work, Harmonie universelle, contenant la théorie et la pratique de la musique, Paris, S. Cramoisy, 1636, and most recently, Génération harmonique, ou Traité de musique théorique et pratique by Jean-Philippe Rameau, Paris, Prault fils, 1737.

The Affinity article in the Encyclopédie considers only the legal sense of the term, i.e. problems of consanguinity in marriage. But the Fermentation article, written by Venel, essentially revolves around chemical affinity, as Fumie Kawamura shows in a thesis in progress on Diderot's notion of fermentation. Both legal and chemical notions of affinity are explicitly articulated in Goethe's Les Affinités électives.

Diderot seems to have hesitated between "tirer avantage" and "se tirer avec avantage" (lesson from L and V).

To quote only Chapter 1 (47a16, b23, b29), "there are differences of three kinds between them" (διαφέρουσι), "here then are the distinctions that had to be made on these subjects" (διωρίσθω), "such are the differences between the arts" (διαφορὰς).

You had to win the prize of the Royal Academy of Painting to become a pensionnaire at the French Academy in Rome, the starting point of an academic career.

Diderot repeatedly returns to this asymmetry: "It wouldn't take long to get along with technique; for the ideal, that can't be learned."(DPV XIV 151, Ver 364.)" Technique is acquired over time; verve, the ideal doesn't come, you have to bring it with you when you're born." (DPV XIV 224, Ver 406.) " Pigal, the good Pigal, called in Rome le Mulet of sculpture, by dint of doing, knew how to do nature, and do it true, warm and rigorous, but has and will have, neither he nor his compère the Abbé Gougenot, Falconnet's ideal; and Falconnet already has Pigalle's doing. (DPV XIV 290, Ver 447.)

Cicero, De senectute, XIV, 47, quoting Plato, Republic, 329c.

Chardin, Les Attributs des arts ; Diderot, DPV XIV 119, Ver 347.

Les Attributs de la musique ; ibid.

Ibid.

Refreshments ; Diderot, DPV XIV 120, Ver 347.

See the article Composition from the Encyclopédie.

Engravings based on drawings by Leprince and Gravelot were produced by Choffard, Prévost, Rousseau and Nicolas de Launay for the 1769 Amsterdam edition.

"[Neptune] made his head emerge from the bottom of the pacified sea" (Eneid, I, 131, placidum for placida and even placata, by hypallage).

DPV IV 183, Ver 44; DPV XIV 75, Ver 489; DPV XV 213 (letter XVI to Falconet).

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Le Visible et l'invisible, Gallimard, 1964, coll. "Tel", 1979, "L'entrelacs - le chiasme", esp. pp. 183-184.

Lagrenée, Mars and Venus, oil on canvas, 1770, Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum, 97.PA.65.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Le technique contre l’idéal : la crise de l’ut pictura poesis dans les Salons de Diderot », in Aux limites de l’imitation. L’ut pictura poesis à l’épreuve de la matière (XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles), dir. R. Dekoninck, A. Guiderdoni-Bruslé et N. Kremer, Rodopi, « Faux-titre », 2009, p. 121-140, pl. coul. 16-30.

Diderot

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Diderot

Les Salons

L'institution des Salons

Peindre la scène : Diderot au Salon (année 2022)

Les Salons de Diderot, de l’ekphrasis au journal

Décrire l’image : Genèse de la critique d’art dans les Salons de Diderot

Le problème de la description dans les Salons de Diderot

La Russie de Leprince vue par Diderot

La jambe d’Hersé

De la figure à l’image

Les Essais sur la peinture

Atteinte et révolte : l'Antre de Platon

Les Salons de Diderot, ou la rhétorique détournée

Le technique contre l’idéal

Le prédicateur et le cadavre

Le commerce de la peinture dans les Salons de Diderot

Le modèle contre l'allégorie

Diderot, le goût de l’art

Peindre en philosophe

« Dans le moment qui précède l'explosion… »

Le goût de Diderot : une expérience du seuil

L'Œil révolté - La relation esthétique

S'agit-il d'une scène ? La Chaste Suzanne de Vanloo

Quand Diderot fait l'histoire d'une scène de genre

Diderot philosophe

Diderot, les premières années

Diderot, une pensée par l’image

Beauté aveugle et monstruosité sensible

La Lettre sur les sourds aux origines de la pensée

L’Encyclopédie, édition et subversion

Le décentrement matérialiste du champ des connaissances dans l’Encyclopédie

Le matérialisme biologique du Rêve de D'Alembert

Matérialisme et modélisation scientifique dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Incompréhensible et brutalité dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Discours du maître, image du bouffon, dispositif du dialogue

Du détachement à la révolte

Imagination chimique et poétique de l’après-texte

« Et l'auteur anonyme n'est pas un lâche… »

Histoire, procédure, vicissitude

Le temps comme refus de la refiguration

Sauver l'événement : Diderot, Ricœur, Derrida

Théâtre, roman, contes

La scène au salon : Le Fils naturel

Dispositif du Paradoxe

Dépréciation de la décoration : De la Poésie dramatique (1758)

Le Fils naturel, de la tragédie de l’inceste à l’imaginaire du continu

Parole, jouissance, révolte

La scène absente

Suzanne refuse de prononcer ses vœux

Gessner avec Diderot : les trois similitudes