Le laboureur et ses enfants (La Fontaine, Desaint et Saillant, 1755) - Oudry

There are two Jouissance articles in the Encyclopédie, the first is grammar and morals, the second jurisprudence. The second is signed with the letter A, which designates Boucher d'Argis, the leading jurist on the encyclopedist team, author of over 4,000 articles. The first is unsigned, but we know from correspondence and intertexts that it is by Diderot. So here we change register completely: from the anonymity of the Amour articles, which indicate a peripheral and slippery terrain, undermined perhaps, we move on to the big names of the encyclopedic enterprise. Jouissance occupies the limelight, in the intellectual debate of the Enlightenment, the notion delineates a sensitive, new, avant-garde zone.

I. Between sign and fruit : defect and excess of legal jouissance

Let's start with the law : the term jouissance is first and foremost a term of law, and it is from its legal meaning that its sexual meaning has derived.

" Jouissance, (Jurisprud.) is ordinarily synonymous with possession ; this is why we commonly say possession & jouissance ; however one can have possession of a property without enjoying it. Thus the seized party possesses until the adjudication, but no longer enjoys since there is an executed judicial lease.

Jouissance is therefore sometimes taken to mean the collection of fruits. To bring back jouissances is to bring back the fruits. Those who bring property to an estate, are obliged to bring back also the jouissances from the day of the opening of the estate the possessor in bad faith is obliged to bring back all the jouissances he has had. See Fruit, Possessor, Possession, Restitution. (A) "

To play is to possess, that's the starting point. But this equivalence is only valid as a kind of label, in the fixed legal expression, " possession and enjoyment ". The law gives you " possession and jouissance " possession and therefore jouissance, it guarantees you possession so that you have jouissance. Enjoyment is the finality of possession, it is also the sign of it, and it manifests itself in a saying : " c'est pourquoi l'on dit... ". If we possess in order to enjoy, if enjoying is the sign of possessing, the consequence may not take place, the sign may be deceptive. Enjoyment begins to detach itself from possession. For example, if your property is seized by the courts, you immediately lose the right to enjoy it, and can no longer use it. The bailiff takes away your furniture and seals your door. But you remain the owner of the property until a new court decision assigns it to a new owner (your creditor, for example, or the person who buys your property at auction). During the time between the seizure of the property and the auction sale, you have " possession of a property without enjoyment ". You have lost the /// enjoyment, but you haven't yet lost possession. So you can detach enjoyment from possession. When you remove enjoyment, possession still remains. This means that we never enjoy the totality of the good, that in the good there is a proper, there is the dimension of possession, an idea of the entirety, the plenitude of the thing, which we can never completely enjoy. There is a remainder that escapes enjoyment: the sign is not the thing, something of the thing escapes the sign.

But what, then, is jouissance itself ? This is the subject of the 2nde paragraph : jouissance is a matter of fruit. The law speaks Latin : fruit comes from the Latin verb fruor, to make use of, to enjoy, to have the enjoyment of. Enjoyment is a matter of fruit, the expression is apparently redundant. But the Latin says something more: fruit, fructus, literally what has been enjoyed, is what has been used, what has been used to do something. Fruit is a product if I have the jouissance of this field, it's to cultivate something if I have the jouissance of this machine, it's to make with it what it makes it possible to make. Enjoyment makes it possible to produce fruits it therefore pays, and gives rise to perception. Enjoying a good allows us to collect what it yields, even if we don't own it the farmer collects the fruit of his labor on the land he enjoys. The production of fruit is the very essence of enjoyment.

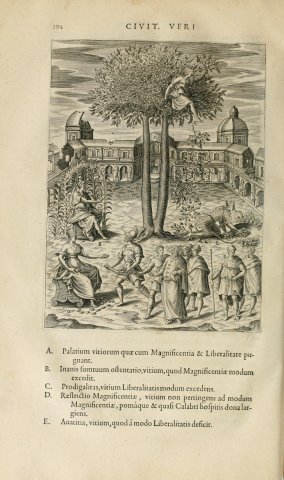

Dispute between peasants over a game of cards - Jan Brueghel the Elder

And here again the law notes a discrepancy between possession and enjoyment : in the case of an inheritance, the deceased's property is awarded to his heirs, possession changes ownership : when there is a dispute between several heirs, when indirect heirs have to be sought, the procedure for settling the succession can take time (sometimes years). The succession is opened, but the inheritance is only definitively settled at the end of this procedure. It's only at the end of this procedure that I take possession of the field, house or livestock I've inherited (this right is essentially agricultural). In the meantime, someone else (for example, another unsuccessful claimant to the inheritance) has worked the field or had someone else work it, lived in the house or paid rent for it, looked after the livestock. Someone else had the enjoyment of a property he did not own : the law stipulates that this enjoyment must be reported, that the profit produced by the property between the opening and settlement of the succession must be repaid to the legitimate heir.

This example is symmetrical to that of seized and sold property. In the case of seizure, possession remains without enjoyment. In the case of inheritance, enjoyment must be reported to possession. It thus appears that enjoyment exceeds possession: there is something more in enjoyment than in possession. This something more in enjoyment is the fruit, which is the added value of the good put to use, put to work. The fruit produced by enjoyment constitutes a surplus of possession, which may or may not be returned. Enjoyment tends to become possession, by its excess it threatens the system of possession.

Joyissance is therefore both something less and something more than possession : something less because it is merely its consequence and sign ; something more because it produces a fruit. This is the legal basis /// to which the issue of love will be grafted.

- A new way of thinking, a new way of thinking, a new way of thinking.II. Jouissance and voluptuousness : the destruction of love

Jouissance is a priori a term of law; it is with law that Trévoux's dictionary begins, which so often provides the Encyclopédie with the framework of its nomenclature. The Trévoux article devotes a final paragraph to the moral meaning of the word :

" Jouissance, se dit aussi en choses morales, & particulièrement en matière d'amour. We pay a short jouissance for the favors of Fortune, for our freedom. S[aint] Evr[emont]. Hope, when it is not [too] doubtful, is a pleasure that hardly yields to jouissance. Le Ch[evalier] de M[éré]. The hope of what we are promised, naturally yields to the jouissance of the present. S[aint] Evr[emont]. Il faut de l'œconomie dans la jouissance des plaisirs ; car l'ame s'ennuye d'être toûjours dans la même assiette. " (Dictionnaire de Trévoux, 1738, p. 336)

What strikes us first is the suspicion and even condemnation that jouissance incurs. Enjoyment is brief, deceptive, disappointing, morally reprehensible. The fruit of jouissance, which occupies first place in its legal meaning and characterizes its positivity, has disappeared here. Without fruit, there is no production in matters of love, jouissance would produce nothing.

Yet jouissance enters into a whole commerce. We pay for it first : to enjoy Fortune's favors, in other words to make love with a woman, we pay with our freedom, we sell her our freedom. But what do we buy for our freedom if not a fruit, if not the pleasure we're going to derive from this enjoyment? Then we speculate on the enjoyment hoping to enjoy a woman is worth almost as much as the enjoyment itself but what does this hope consist of, if not in estimating the value of the fruit ? But hope is nothing compared to the " enjoyment of the present " in other words, the fruit. Finally, enjoyment is administered, regulated, and enters into an economy of production, which is a management of fruit. There is a libidinal capitalism of jouissance, but a capitalism that never names itself, never uncovers itself more than half : in matters of love, the fruit remains the unspoken of jouissance, signified by it but kept under the bar of the dicible.

Diderot is to counter this moral reprobation and repression of the fruit in a ceremonial article that takes on the allure of a manifesto :

" PLAY, s. f. (Gram. & Morale.) jouir, c'est connoître, éprouver, sentir les avantages de posséder : on possede souvent sans jouir. Whose magnificent palaces are these ? who planted these immense gardens ? it's the sovereign : who enjoys them ? it's me. "

Diderot isn't writing a moral supplement to a legal article he's seizing, totally, on jouissance, and starting again from the distinction between jouir and posséder, which comes from the law. He then adopts a moral perspective and takes up a Stoic metaphor, which he no doubt borrows from Seneca :

" Your roofs can shine in all places, whether camped on mountains with a vast view /// on the land and the sea, or raised on the plain against the heights of the mountains, you may build many large ones, but you're still just frail individual bodies. What are all these rooms for? You only need one to sleep. Wherever you are not, it is not yours1. "

Seneca distinguishes between building palaces and inhabiting them, between architectural and human occupation : only the latter counts, it alone is true possession, as the last formula forcefully and unambiguously affirms. The philosopher lectures the prince, and preaches against luxury : morally speaking, there is no specific category of enjoyment, enjoyment must function as the unambiguous sign of ownership.

.

Diderot will completely subvert this image of the palaces and estates of kings. Ownership and enjoyment are this time identified with two distinct subjects, the sovereign builder and the user self. Diderot says " the sovereign " not the king, or the prince. The term sovereign has a precise political meaning: he is the one who politically exercises sovereignty. In principle, and by and large, it comes down to the same thing: the king but strictly speaking, in Enlightenment political thought, the sovereign is, in whole or in part, the people, who delegate their sovereignty to the king2. And indeed, while the king ordered the buildings and plantations in his name, it was the people who planted the gardens...

If the sovereign and I constitute at one level two persons who oppose each other, they define at another level the relationship of a political community to its singular metonymy, and through this relationship an exchange, a circulation between the king and me. Through my walk in the public gardens (Diderot loved to stroll) I enjoy as a sovereign, I experience sovereignty metonymically.

But come on, Diderot interrupts, ebullient : we're talking about jouissance, there's much more on the carpet... And to follow up with voluptuousness, which he praises in the spirit of Lucretius3.

" But let us leave these magnificent palaces that the sovereign has built for others than himself, these enchanting gardens where he never walks, & let us stop at the voluptuousness that perpetuates the chain of living beings, & to which we have dedicated the word jouissance. "

As he explicitly states, his discourse will be a discourse on voluptuousness, " to which we have dedicated the word jouissance ". Volupté is elevated to the dignity of jouissance, and the Encyclopédie article recognizes, sanctions a mutation in society, which now uses this term rather than the other.

This is because, outside the small materialistic sect, voluptuousness is perceived negatively. We saw how the last paragraph of the Jouissance du Trévoux article, " en choses morales " and " en matière d'amour ", avoided voluptuousness and dispensed with the " fruit ", which nevertheless served as the basis for the legal explanation of the word in /// the preceding paragraphs. When Diderot praised voluptuousness in the epistle to the Princess of Nassau Saarbrucken that was to serve as the dedication to Père de famille in 1758, he was forced to withdraw this compromising paragraph, at the princess's request4. In the allegorical iconography from which Titian's Sacred Love and Profane Love derives, the two opposing figures are often named Virtue and Voluptuousness. Volupté, or lust, corresponds to immoral life conduct.

By bringing volupté into the legal vocabulary of jouissance, or rather by solemnly consecrating this new usage, Diderot completely reverses the moral depreciation of volupté. But this reversal comes at a cost volupté, by becoming jouissance, by blossoming as full and positive jouissance, replaces love.

" Among the objects that nature offers on all sides to our desires ; you who have a soul, tell me, is there one more worthy of our pursuit, whose possession & enjoyment can make us as happy, as those of the being who thinks & feels like you, who has the same ideas, who experiences the same warmth, the same transports, who carries his tender & whose caresses will be followed by the existence of a new being who will be similar to one of you, who in his first movements will seek you out to hold you, whom you will raise by your side, whom you will love together, who will protect you in your old age, who will respect you at all times, & whose happy birth has already strengthened the bond that united you ? "

In this lyrical evocation of the procreative deployment of voluptuousness, Diderot once again links possession and enjoyment, which the law had dissociated. This possession-jouissance is expressed using a very specific syntax: a first cluster of relatives (" l'être qui pense..., qui a..., qui éprouve..., qui porte..., qui vous embrace... ") develops the activity of the beloved in relation to the lover a second cluster (un nouvel être qui sera...a second cluster (a new being who will be..., who will seek you out..., whom you will raise..., whom you will love..., who will protect you..., who will respect you...") is organized around the child, who in turn develops his or her activity. Under the guise of a simple paradigmatic accumulation of relatives, Diderot operates a double mutation from erotic love to conjugal, then filial, love. Under the guise of similarity (" the same ideas, ...the same warmth, the same transports " then " similar to one of you "), Diderot converts voluptuousness into a family bond, the impulse of desire into the duty of children. He also shifts the point of view: from me to us, to you, from you to the beloved, to the new being produced, and back to you. A loop is completed that seals the family unit, according to the same logic that presided over the nomenclature of the Encyclopédie's Love articles.

Here we touch on the fundamental ambiguity of the Jouissance article and, behind it, of the Enlightenment's relationship to the question of love and jouissance. On the one hand, we see the liberation of voluptuousness, its positivization as jouissance, which becomes a conceptual category in its own right. On the other hand, we see the topological interplay of possession and enjoyment, opened up by legal definition but also made possible by the Stoic heritage, closing down: we possess the essence while we enjoy the fruits; we possess architecturally, by building and transforming places, while we enjoy personally, where we are. This game disappears as voluptuousness is superimposed on jouissance jouissance spreads, depersonalizing and simultaneously de-eroticizing itself, occupying social space in its turn, restructuring it as a new principle of possession.

." The brutish, insensitive, immobile, lifeless beings that surround us can serve our happiness ; but it's /// without knowing it, without sharing it: our sterile and destructive enjoyment, which alters them all, reproduces none of them. "

Generous praise for sharing and sensitivity must not blind us to the new political economy that is taking shape : the old destructive pleasure of lustful voluptuousness is opposed by a pleasure that produces and reproduces the predatory egoism of the libertine is succeeded by a sensitive power that orders an environment. In this restructuring, which moralizes without saying so, we recognize the new bourgeois family unit of the Enlightenment, but also the triumph of a commodified, productivist economy of desire enjoyment is productive, and the social bond it orders monetizes an exchange to life given answers duty consented.

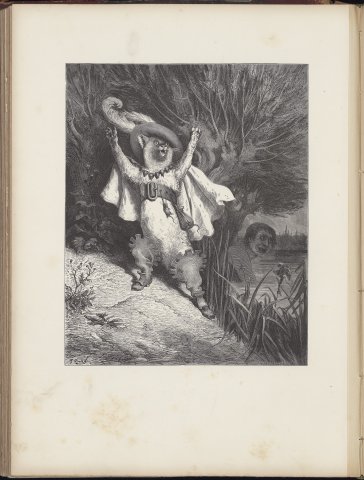

III. The problem of possession without jouissance : Le Chat botté

The empowerment of jouissance at the dawn of the Enlightenment had decisive consequences for our culture, but also more generally in the relationship to the body and the relationship between the sexes, and in the way this dual relationship became articulated in the general economy of our societies. Lacan identified this decisive mutation with the figure of Sade, whom he articulates as Kant's flip side, extending the analysis developed by Adorno and Horkheimer in The Dialectic of Reason5.

But the fracture noted by Lacan, the radical separation that takes place between the pursuit of pleasure (jouissance) and the pursuit of the moral good (the old love), was prepared well upstream. This is shown, for example, by the tale of the Chat botté, published by Charles Perrault in 1697. The starting point of the Chat botté is a matter of inheritance. We know that it's during inheritances that the question of possession and enjoyment arises par excellence. The three sons of the miller receive a mill for the eldest, a donkey for the second, and a cat for the last, who is distressed :

" My brothers, he says, will be able to earn their living honestly by getting together ; as for me, once I've eaten my cat, and made myself a muff from its skin, I'll have to die of hunger. "

It's important to understand what's at stake here, which isn't just the inequality of sharing. The mill and the donkey are already unequal shares, but both are productive inheritances, indispensable instruments for turning wheat into flour : the mill doesn't turn without the donkey, and the donkey has no interest without the mill. This is why the two elders will be able to set up their business together, and thus make the most of their inheritance : make it bear fruit, insert it into an exchange and convert it into trade.

.

Nothing like this with the cat : the miller's youngest son owns a cat, but he can't enjoy it, there's no possible fruitful enjoyment likely to value it as property. The pleasures he imagines - eating it or making a sleeve out of it - consist in destroying his property, i.e. dispossessing himself of it. The whole tale is about warding off this initial aporia: if I own my cat, I don't have the right to dispose of it. /// if I enjoy my cat, by destroying it, I will cease to possess it. Possession and enjoyment are disjointed, and it's a question of making them coincide again.

In the Italian version of the tale6, from which Perrault draws, the cat was a pussy : jouir de la chatte, the sexual allusion is obvious, even if the benjamin's desire is never explicitly formulated.

The cat then sets out to save his skin. He goes on the hunt :

" Don't grieve, my master ; all you have to do is give me a bag and make me a pair of boots to go into the brush, and you'll see that you're not as badly shared as you think. "

Everything about this outfit is strange, and totally implausible : where does the miller's son get the money to make the cat aristocratic hunter's boots ? And what does he need with a hunting bag ? The bag and boots don't function here as adjunct instruments to the quest (as is often the case with objects in a tale) ; they are signs7. The bag is a sign for the game, and the boots a sign for the king. Enjoyment has to do with the sign. The cat stands behind his bag, and in his boots, withdrawn from himself. The cat gives meaning to what it wears, what it takes, what it says. He doesn't signify by himself, but by what he shows. But he stands on the side of the signified.

The cat hunts with a bag. The bag is not only a sign it operates as a function of jouissance. The game falls into his bag and provides his contentment :

" No sooner had he gone to bed than he had contentment : a young stunner of a rabbit entered his bag, and the maistre Chat, also tost the cords, took it and killed it without misericorde. "

The bag is a female sex, or the sign that the cat functions as sex : it enjoys what enters it. The rabbit, or conil, which we met in L'Amour sacré et l'amour profane, redoubles this sign. The second take consists of two partridges : the two partridges designate pederasty in Horapollon's Hieroglyphica. Enjoyment is declined in its various relationships. Each catch is offered to the king by the Marquis de Carabas, to whom it gives pleasure.

- Tell your maistre, replied the roy, that I thank him and that he gives me pleasure.

The king again received with pleasure the two partridges, and made him give them to drink.

This is indeed jouissance; the king will enjoy the fruits of the cat's hunt. But this hunt is poaching, and the cat in no way owns the game it offers. The cat produces jouissance without possession.

Then comes the episode of simulated drowning : the cat makes the king believe that his master has been robbed of his clothes, so that the king dresses the miller's son in his own clothes :

" The king gave him a thousand caresses, and, as the fine clothes he had just been given enhanced his good looks (for he was handsome and well made of himself), the king's daughter found him very much to her liking, and the marquis de Carabas had not given him two or three glances, very respectful and a little tender, that she became madly in love with him. "

After enjoyment, love : the king's daughter falls in love with the miller's son in the clothes of his /// father she falls in love with a sign of belonging, she deludes herself with the reflection of her family's own brilliance. Once again, the so-called Marquis de Carabas promises enjoyment without possession. He doesn't promise it as a subject: he never speaks, takes no initiative, doesn't act. It manifests itself simply as a signifier, whose signified the cat has replaced. The cat is, objectively and not subjectively, the jouissance of the Other it implements the jouissance its master lacks, the inheritance of which has frustrated his master it constructs it, makes up for it. But the subject of this jouissance is the Marquis de Carabas, who doesn't exist : crossed-out subject, and in this par excellence subject of jouissance, insofar as there is no jouissance but marked, founded by castration.

The miller's son, in this case, conveys the signifiers of love : it is of these signifiers, foreign to himself, that the king's daughter becomes madly in love. The tale thus illustrates Lacan's formula that " the jouissance of the Other, of the body of the Other that symbolizes it, is not the sign of love8 " : the Other's jouissance is the cat he, bequeathed in possession to the miller's son with no possible jouissance, turns out to be the purveyor of all jouissances, the tale operates this reversal.

But the cat doesn't offer jouissance directly, immediately ; he first constructs simulacra of it, he presents the king with signifiers : see how my master hunts, see all that my master possesses. The cat transfers these simulacra to his master's body in the episode of simulated drowning. In this episode, the cat provides the master's body, through the gift of the king's clothes, with the ideal envelope of the perfect lover. The miller's son is not the subject in this affair, he is merely the sign of love, a mute pantomime wearing the livery of the one he should be, reducing himself, identifying himself with the sign of the Marquis de Carabas : a coat rack of signifiers provided by the cat.

There's a limp, or a flaw in this story : the cat seems the real hero of the tale, which nonetheless leans towards rewarding the miller's son, who's totally naïve, passive and veiled. The love story that Le Chat botté does not tell (the story of a miller's son who marries a king's daughter) is the story of the triumph of stupidity : the fool wins9. But in fact the hero of the story is the Marquis de Carabas, a virtual subject, the pure signifier of a non-existent subject: the cat supplements the jouissance of the Other, producing it under his hand through his actions and stratagems, while the miller's son receives on his body, in the light of the gaze of the king and his daughter, what is signified by the cat, and becomes, as a pure mute body, the signifier of the marquis, Constantin's true labarum10, and through him the signifier of love. The pair formed by the cat and the miller's son thus constitute, signifier and signified, the sign elaborated by the tale.

Then comes the ogre episode, which completes the device : the cat seizes his castle, which constitutes the paradigm of possession. Whether we're thinking of Seneca's dazzling roofs or Diderot's magnificent palaces the castle symbolizes possession, in which the aim is to install enjoyment. Possession is achieved by absorption to install the simulacrum of possession, the cat becomes an ogre, i.e. /// pure devouring power11. He threatens to chop up the peasants as mincemeat if they don't say that the meadow they're mowing, the wheat they're harvesting belongs to the Marquis de Carabas : mowing, harvesting, possession is signified by cutting, it rests on the symbolic institution of castration. But the simulacrum of possession is achieved through the threat of food, the threat of devouring. And the occupation of the castle is achieved by carrying out the threat: the cat devours the ogre, the devouring turns against itself.

.There's no oral pleasure in this devouring : the cat continues his work, which he began by taking a rabbit. The cat is a bag, a feminine sex working for pleasure through absorption : of the rabbit, of the two partridges, of the peasants reduced to fodder if they disobey, of the ogre foolishly transformed into a mouse. Up until the Marquis de Carabas' marriage, there is no mention of the cat's pleasure, and he acts methodically, consistently and effectively to achieve it. The cat's work of death, the proliferation of devouring it implements, supplements the enjoyment that as a mere cat, as part of the miller's inheritance, it cannot provide the miller.

The extra jouissance produces a simulacrum of possession, which triggers love :

" Le roy, charmé des bonnes qualitez de monsieur le marquis de Carabas, de même que sa fille, qui en estoit folle, et voyant les grands biens qu'il possedoit, luy dit, après avoir beu cinq ou six coups :

"Il ne tiendra qu'à vous, monsieur le marquis, que vous ne soient mon gendre." "

It's not the miller's son who charms the king. The real person never takes over from the assumed identity. Right to the end, it's a pure signifier of enjoyment (" les bonnes qualitez de monsieur le marquis de Carabas " charment le roi, produisent un effet charmant, procurent de la jouissance) associated with a pure signifier of possession (" seeing the great goods he possesses ", whereas the miller's son really possesses nothing but the cat) that determines the king's decision to give him his daughter's hand in marriage, through which he will obtain the reality of enjoyment and possession.

In this process, love plays a decisive role : without the love of the king's daughter, the shift from simulacrum to the reality of possession and jouissance cannot take place. Love, in a completely unexpected way, is the real, it's what connects the cat's delirious phantasmagoria back to the real. The madness of love (" elle en devint amoureux à la folie ", " sa fille, qui en estoit folle ") symbolically triggers royal acceptance, recognition of the title of marquis and the consequent change in social position, turning the apparatus of feigned jouissance constructed by the cat into real possession and jouissance. Love is the reversal of the cat's bag, where the real and imaginary had been caught in the trap. In this trap we find real wild game with fictional highway robbers, real peasants in their fields but fictitiously reduced to swill, a real ogre in his castle, but the ogre exists only in fairy tales.

.IV. The scandal of pure enjoyment

Narratively speaking, what's at stake in Chat botté is the resolution of the liminal aporia posed by the cat's possession without jouissance. The cat resolves this aporia by constructing an apparatus of jouissance based entirely on the management of the signs with which he endows the miller's son. Love converts these signs into the reality of possession with jouissance. The union, the perfect superposition between possession and jouissance is thus re-established.

To bring about this restoration, the tale creates an extraordinary character it doesn't call /// simply the cat, or the puss in boots, but Le Maître chat, that's the original title of the tale published by Perrault in 1697. Nowhere in the tale does the cat usurp the rank, the precedence of his master, always taking great care to speak in his name, to stand in the background of the Marquis de Carabas's name, which he is not and never claims to be. But the cat is nonetheless the sole architect of the spectacular reversal of fortune that promotes the miller's youngest son to the future inheritance of the king's very kingdom.

So this cat turns out to be a master cat, it's obvious even if it's never said, except in the title, that he's the real master. The cat holds a discourse that takes the place of the discourse of the master he is not, which Lacan schematizes with the formula and mathemes of the discourse of the hysterical :

| $ | S1 | |

| - | → | - |

| a | S2 |

Where S1 designates the signifier of the master (of the miller's son), S2 the signifier of the slave who is at the same time the holder of knowledge (the cat), $ the subject as lacking (the Marquis de Carabas) and petit a the apparatus, the production of jouissance, the " plus-de-jouir12 ". The arrow indicates what discourse does, which is to represent, and also marks thereby what it cannot do, its impossibility of being : $ speaks, or more exactly, the cat makes $ speak, because it is impossible for S1 to express itself, because the miller's son is incapable of enunciating, of holding the S1 discourse of the master signifier he's too stupid to do so. The cat's discourse is held in the name of the Marquis de Carabas; it is the cat who inhabits, who manipulates the signifier S1, and who through it pulls the strings of $ : he holds the knowledge of the master signifier, he constitutes its signified, S2. Of the Marquis de Carabas, what is signified by the cat is that not only does he possess, but he knows how to enjoy : beneath $, the underpinning, the signifier, justifying that he is the only subject, stands a, the " plus-de-jouir ", the apparatus of jouissance. This apparatus consists in the implementation of a production : the garenne produces the game of the hunt, the fields produce hay and harvests, the château, finally, produces the banquet, which is the height of jouissance.

.The cat's gifts to the king are the small a on which this discourse rests. In so doing, the cat represents his master, S1, whose position of mastery is signified by his cat service, S2.

$, the Marquis de Carabas, is thus placed, as a name, in the cat's discourse, in the position of signifier. Lacan suggests that " the signifier, unlike the sign, is what represents a subject for another signifier ", and " nothing says that the other signifier knows anything about the affair13 ". the name of the Marquis de Carabas represents the subject function for the miller's son, S1, and brings with it the function, or product, of jouissance, the knowledge of jouissance, petit a.

The discourse of the hysteric is a twisted master discourse : the four elements of the discursive structure have undergone a quarter-turn that moves the master signifier, S1, from representative to represented, from the one who holds the discourse to the one for whom, in whose name, the discourse is held. The master's discourse - the discourse that is lacking in the tale - is as follows:

| S1 | S2 | |

| - | → | - |

| $ | a |

The master's speech S1 represents the slave's knowledge S2. The slave has the know-how, but the master alone is capable of formulating it, of holding its language. In other words, the master's discourse rests on his distinction, his quality as master, $ ; while the slave's know-how rests on his ability to produce wealth, the plus-de-jouir, petit a. When the master is not, or is no longer, able to hold the discourse that justifies his rank, the place of S1 can be occupied by one of the other three instances of the constitutive square of all discourse. This is what happens in Le Chat botté. But there is no simple substitution possible, because each of the elements is linked to the others in a chain, or a necessary carousel: the master signifier S1 is linked to the slave's knowledge S2, which is linked to the production of jouissance petit a, which is linked to the subject $, which is linked to the master signifier. When one of these elements malfunctions, the only thing the carousel can do is spin.

The cat's essential sleight of hand consists in this quarter turn : he doesn't have it, jouissance, petit a, and he's powerless to procure it, that's the starting point of the tale. While the mill and the donkey, through their ownership, immediately provide enjoyment, the cat does not. From S2 to petit a, then, there's a relationship of impotence. Failing to procure jouissance, the cat assumes this capacity in the Marquis de Carabas, inventing this signifier of the Marquis to which it attaches the signified of jouissance. The whole thus formed, the simulacrum $/a, will represent the couple S1/S2 that it forms with its master, wisely placed in the position of signified, under him, possessed by him to enjoy it. It takes all this hysterical apparatus for jouissance to be drawn from the cat.

The apparatus in question, $/a, the jouissance signified by the marquis's name, is a pure creation of the cat. This simulacrum takes the place of pure jouissance, making up for what the miller's youngest son lacked in the sharing. This device produces pure jouissance this is what the master cat represents, ultimately and by reversal, as " other satisfaction14 " identified with the woman's sex. Pure jouissance is not phallic jouissance no desire for an object is expressed in the tale, which would be obstructed rather, the pattern that repeats itself is that of a trap being set, the cat's open sack, followed by increasingly elaborate substitutes for the sack, into which all sorts of game fall, right up to the king's daughter, the ogre and the king himself.

The cat sets up this net, these spread thighs, where the signifiers of jouissance are trapped. But the cat, as master, stands back from this apparatus. Of him, of his desire, he says nothing, we know nothing, except this very fleeting final mention :

" The marquis, making great reverences, accepted the honor the king did him, and, dice the same day, he married the princess. Le Chat became a great lord, and no longer chased mice except for amusement. "

The so-called marquis expresses no satisfaction, no pleasure. It's an honor bestowed on him, the symbolic sanction of honor that puts an end to his request. The cat, on the other hand, gets something more. By becoming " grand seigneur " like his master, he accedes to the position of master and justifies his title of master cat. But on top of that, he can " entertain " : entertaining is more ; it's the cat's income. /// of the " plus-de-jouir ". The last word is for the cat's pleasure, which has never been mentioned before and while nothing is said about the pleasure of the miller-turned-marquis.

He " ne courut plus aprés les souris que pour se divertir " : the cat no longer feeds on that hunt, it is beyond the satisfaction of a need, it is no longer hungry such is pure enjoyment, which manifests itself detached from any problem of possession, gratuitous and sovereignly immoral.

Notes

Rousseau is more radical. In Lettre à D'Alembert [1758], he writes that " dans une Democratie où les sujets et le souverain ne sont que les mêmes hommes considérés sous différents rapports " (Œuvres complètes, ed. Gagnebin et Raymond, t. 5, Gallimard, Pléiade, 1995, p. 105). And in Le Contrat social [1762] : " This public person which is thus formed by the union of all the others formerly took the name of City, and now takes that of Republic or political body, which is called by its members State when it is passive, Sovereignwhen it is active, Power when comparing it to its fellows. " (Livre I, chap. 6, in Œuvres complètes, t. 3, p. 361-362.)

///" Omnibus licet locis tecta vestra resplendeant, aliubi imposita montibus in vastum terrarum marisque prospectum, aliubi ex plano in altitudinem montium educta, cum multa ædificaveritis, cum ingentia, tamen et singula corpora estis et parvula. Quid prosunt multa cubicula? In uno jcetis. Non est vestrum ubicumque non estis. " (Seneca, Letters to Lucilius, Book XIV, 89, 21, I translate)

In L'Esprit des lois [1748], Montesquieu differentiates " three espèces de gouvernements " according to the sharing of " la souveraine puissance " (Livre II, chap. 1, ed. R. Derathé, t. I, p. 14). " In the republic, the people as a body have sovereign power " (ibid., chap. 2) ; " in the aristocracy, sovereign power is in the hands of a certain number of persons " (chap. 3, p. 19) ; but for monarchical government, where " the prince is the source of all political and civil power ", Montesquieu is careful not to use this term " sovereign ", insisting instead on " the intermediate powers "

Lucretius' De rerum natura opens with an invocation to Venus : Æneadum genetrix, hominum divumque voluptas, " Enfanteuse des Énéades, volupté des hommes et des dieux ". Diderot repeatedly refers to this Epicurean text as a benchmark for Enlightenment materialism. Note here how Lucretius associates voluptuousness with a production, a fruit : Venus is genetrix, not simply mater.

Diderot remembered these censored lines in 1758 when he wrote the Jouissance article, published in 1765 but perhaps written at the same time as the epistle. The paragraph began: " I'll be careful not to disparage voluptuousness or decry its appeal. Its purpose is too august and too general " (DPV X 185)

Lacan, L'Éthique de la psychanalyse, Séminaire VII, 1959-1960, ed. J.-.A. Miller, Seuil, 1986, p. 93-97 ; " Kant avec Sade " [1963], in Écrits, Seuil, 1966, p. 765-790.

Straparola, " La Chatte de Constantin le Fortuné " (modern title) in Les Nuits /// facétieuses, Venice, 1553, XI, 1. In this version, the three objects the three sons inherit are a hutch for kneading bread, a lathe for turning dough, and a cat. The disproportion between the objects is less clear-cut on the other hand, the distinction between what can produce jouissance and what cannot is very much the same.

On the symbolism of the bag, or besace in the tale, see P. Eichel-Lojkine, Contes en réseaux, Droz, 2013, p. 245-246. In Straparola's version, the bag is used by the cat to bring young Constantine food from the king's table. Perrault does away with this whole theme of hunger and food in favor of the sole function of producing signs of jouissance.

Lacan, Encore, Séminaire XX, I, 1, Seuil, p. 11.

" Lacan, it seems, in his first seminar, as it's called, of this year, would have talked, I'll give you that, about love, no less. [...] I think it's clear, even if you haven't formulated it for yourself, that in this first seminar I spoke of stupidity. " (Encore, op. cit., p. 16-17) Love is unspeakable, we can only speak of the way love is written, said, of the construction of the signs of love. This construction is organized as an overbidding of demand : more, more ! Nothing could be sillier than this one-upmanship, to which, when we speak of love, we can only collaborate.

Constantin is the name of the cat's master in Straparola's tale.

There is no ogre in Straparola's tale, where the lord of the castle the cat seizes is simply absent, then dead on a journey. With the ogre, Perrault perfects the bag device.

See Encore, p. 21.

See L'Envers de la psychanalyse [1969-1970], Séminaire XVII, Seuil, 1991, p. 31sq.

Lacan, Encore, VI, p. 61.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Jouir et Posséder » , Séminaire LIPS, automne 2019, université d'Aix-Marseille.

Littérature et Psychanalyse

Archive mise à jour depuis 2019

Littérature et Psychanalyse

Le Master LIPS

Séminaire Amour et Jouissance (2019-2021)

Amour et Jouissance

Jouir et Posséder

Vers l'amour-amitié

Les signifiants du désir

50 nuances de Grey

Duras, la scène vide