I. Love in psychoanalytic theory

Psychoanalysis didn't come to love right away; love wasn't its terrain. For poets, on the other hand, and for philosophers, love is the great subject : to say love, to deploy the prestiges and sufferings of love, to give oneself love as a goal, this is what defines the field of culture but this beautiful theater, this front of stage is suspect, too shiny, too smoothed for psychoanalysis, which would prefer it to the backstage of desire.

Fairbairn and the American School

However, from the 1950s onwards, American psychoanalysis, notably around the work of Ronald Fairbairn1, reoriented the Freudian theoretical model, which defined its field through the study of libido, and libido as pleasure-seeking. The new theoretical model places the child in a system of relationships rather than drives, and defines its development from the search for objects (object-seeking) rather than the satisfaction of desires (pleasure-seeking). With this theoretical reorientation, emotion, affectivity, positive or negative feeling replace drive and desire as the vectors of analytic discourse. The background of this discourse, its imaginary framework and its promise, is a pink novel of love that comes to replace the black novel of libido.

The observation of this American mutation is the starting point for Lacan's seminar on Le Désir et son interprétation2. Lacan begins by claiming Freudian orthodoxy in order to bring psychoanalysis back to its original terrain and theoretical vector, the interpretation of desire. But he does not ignore the new approach: it will be a question of making a place for love in psychoanalysis.

.I spoke of a pink novel of love, in Fairbairn's theorization of libido. It's this pink novel that Lacan tackles, putting desire back at the heart of analysis. The pink novel is the harmonious development of the personality that this psychoanalysis seems to aim for, and promise : the " possibility of openness to love, or of fullness of realization of love " (p. 13). Desire has nothing to do with the rosy romance of love. It points

" what Freud classified under the title of the ravishing of love life. Namely, that while desire does indeed seem to bring with it a certain quantum of love, it is very often a love that presents itself to the personality as conflicted, a love that does not confess itself, a love that refuses even to confess itself. " (ibid.)

In a word, love is not what the analyst can catch in his nets from what his patient tells him. In the psychoanalyst's office, if there's any question of love, it's always in the hollow, as conflict, as the unspoken, as the refusal to love. Love slips away, not as an end sought by the patient to which it would be difficult to gain access indeed, it's exactly the opposite : even when the object of the search seems to be love, this object soon reveals itself to be a lure, swallowed up, damaged, torn apart by desire.

.The European culture of desire

Lacan then summons poetry and philosophy, and more precisely on the one hand English metaphysical poetry (John Donne), on the other the medieval Aristotelian tradition of philosophy. It is the European foundation of culture that is called upon, the cultural roots of psychoanalytic theorizing, in the face of American behaviorism, i.e., an aculturated modeling of behavior.

.The European culture of desire warns us against the seductions of an easier, more optimistic discourse on emotions and relationships, of which love, taken as an objective, as an end in the fulfillment of personality, would be the lure. Let's simply quote, in Gilles de Seze's translation, the penultimate stanza of Donne's long poem, The Ecstasy, to which Lacan refers in passing :

So, let us turn to our bodies, that thus the vulgar

May love contemplate ;

Dans les asmes, ont beau s'épanouir des amours les mystères,

Remains that the body is its Book Revealed.

To our bodies turn we then, that so

Weak men on love reveal'd may look;

Love's mysteries in souls do grow,

But yet the body is his book.

Love, the spiritual unity of the loving fusion of souls, can't be seen all we can see are bodies, and for example those " firmly cemented " hands on which the poem opened. The signs of love are seen in bodies, just as the divine grace of revelation is seen only indirectly, in the testimony of the Gospels. From the disjunction of soul and body, Donne introduces what is not yet, but will become, a disjunction of desire: the signs that the book of bodies gives the vulgar to read obey the logic of bodies, which is not that of the spiritual mysteries of love, to which he has no access, for which there is no sign. These signs define the corporeal field of desire, jouissance ; but for love proper, that is, for what of desire has to do with the soul, for the noblest part of desire, where its fusional finality resides, there is no external access, no sign.

Philosophy's Aristotelian heritage says the same thing, and indicates the same disjunction, which is that of pleasure-seeking on the one hand (pleasure-seeking, on which the Freudian approach is based), and object-seeking on the other (object-seeking, this is Fairbairn's model), what in philosophy we designate as the search for the sovereign good : the object to be attained for optimal personal development is the sovereign good. Just as John Donne aligns the visible enjoyment of bodies with the invisible love of souls, so Aristotelian morality aligns the pursuit of pleasure with the pursuit of the highest good. But this ideal coincidence, this incantatory conjuring of coincidences, already tells us what the structure of the system of desire is, and the lever from which to deconstruct it.

II. Genealogy of jouissance

The contemporary system of desire

For here we touch on the great contemporary system of desire : on the one hand, there is the physiological satisfaction of desire, jouissance on the other, sentiment, heir to the satisfactions of the soul, comes to justify, moralize, elevate desire. Desire of the body and desire of the soul form a system in our world we shouldn't enjoy without loving, because that would debase us and we shouldn't love without enjoying, because then we'd suffer. The ideal would therefore be to love and enjoy, to /// make these two territories overlap perfectly, in the same time and the same bodies, in the same uses of the body.

Yet the evidence is there this perfect superposition does not exist. At most, we sometimes achieve a temporary and imperfect coincidence. It is precisely and fundamentally from this non-coincidence of love and jouissance that both the terrain of psychoanalysis and the field of literature open up.

I spoke of a contemporary system of desire : it is indeed born with the Enlightenment, which operates the conceptual junction between an erotics and a jurisprudence of jouissance, between jouissance as pleasure and jouissance as property. The contemporary category of jouissance is the product of this junction.

.

Before the Enlightenment, another system of desire prevailed, going back to the troubadours and Tristan's novel. This system was described by Denis de Rougemont in L'Amour et l'Occident3. Love was not opposed by jouissance, but by marriage passion in love is then essentially thought of as adultery. Marriage introduces a separation into jouissance there is jouissance within marriage and jouissance outside marriage outside marriage, the eroticism of jouissance belongs to love, conceived as adulterous passion in marriage, jouissance consists in possession in the legal sense of the term. The fusion of the two jouissances, with the advent of the Enlightenment, led to the exclusion of marriage from the system of desire, and precipitated the decline of marriage throughout our Western societies, through its secularization (the bonds of marriage cease to be sacred), its liberalization (marriage is a contract that can be broken at any time), its dissemination into a multiplicity of possible configurations (marriage and PACS, marriage for all).

.Of course, these formulations are schematic. The decline of marriage reveals a more fundamental shift in the relationship between desire and the symbolic institution. With the Enlightenment, this relationship ceases to be necessary. This is what Lacan expresses at the start of the seminar on The Ethics of Psychoanalysis, evoking libertine literature and its sadistic culmination:

" A certain philosophy - which immediately preceded the one most closely related to the Freudian outcome, the one handed down to us in the 19th century - a certain philosophy, in the 18th century, had as its goal what might be called the naturalistic emancipation of desire4. "

This desire, which is now conceived and practiced as a natural need, what exactly does it free itself from ? First of all, from the social institution, which claims to frame, channel and govern it (in marriage, for example). But more generally, desire frees itself from all forms of typological thinking, from a physiology that would divide it into norms of use and perversions, from a poetics that would assign it this or that form, whether erotic, libertine, novel or philosophical dialogue. Of this global emancipation of desire, libertinism is, but is only, the advanced point.

For the new jouissance inherited from the Enlightenment has also radically transformed the nature of love. Of course, the reasons for this mutation, which should not be thought of as a simple conceptual mechanism, are many : economic (which /// eroticize nature and the peasant), social (naturalizing merit through seduction), political (relying on natural enjoyment to claim legal ownership), ideological (grounding the subjectivity of a judgment of taste in nature). But when it comes to love, and especially the new kind of love that emerged with the Enlightenment and is no longer necessarily defined in terms of marriage, we have to start by accepting the suspension of reasons. Love opens up a suspended space, socially and politically aberrant, which nourishes literary discourse: a fusional space, where the loving couple becomes one, where the impossible fusion of self and Other takes place. This fusion carries a new symbolic order, an extraordinary order, virtual and yet real, an unthinkable order.

How does this unthinkable express itself ?

Love and jouissance in Lacan's Encore Seminar

To think this unthinkable, Lacan resorts to a series of paradoxes. The first is the formula with which he opens the Séminaire XX, according to which " the jouissance of the Other is not the sign of love " : didn't John Donne tell us, though, that it was the only sign we had ?

To our bodies turn we then, that so

Weak men on love reveal'd may look;

To our bodies, to our bodies, to the enjoyment of our bodies, to the signs given us by the enjoyment of the Other, we turn then, turn we then, so that, that so, weak men, weak men, mere mortals who have not known the mystical experience of love from within, may look, may look, may have access through the gaze, on love revealed, to love revealed, to the revelation of love, to the divine grace, unrepresentable, ineffable, incommunicable, of this revelation.

What happened between our bodies and love reveal'd ? What does Lacan mean when he says that the jouissance of the Other (visible in our bodies) is not the sign of love (of love reveal'd) ?

First of all, we must point out the ambiguity of the noun complement " la jouissance de l'Autre ", which can designate a subjective genitive (the fact that I enjoy the Other), or an objective genitive (the fact that the Other enjoys... and then who, what does the Other enjoy ?). In the same vein, " the sign of love " can be understood as the sign that I love the Other (it's not because I enjoy my partner that I love him/her), or as the sign that the Other is in love (it's not because my partner enjoys that he/she is in love)

.Should we resign ourselves to never knowing ? In me, my enjoyment proves nothing. Facing me, the jouissance of the Other proves nothing. The object of jouissance does not coincide with the reality of the love relationship. Basically, thinking about the Other's jouissance is impossible.

.For this reason, Lacan launches this second formula, that there is no sexual relationship : in what we call sexual relationship, two partners enter into a relationship to jouissance ; but there is jouissance only from the Other, that is, from someone other than the one who is there, the one I imagine, idealize, the one in my fantasies. So, strictly speaking, there is no relationship.

So much for the jouissance side, and its disappointments. Yet, Lacan tells us, " love is a sign, and it is always reciprocal " : I spoke earlier of a suspended space of love, which is not rational, which is not dependent on the contingencies of reality. This fundamental unreality and logical impossibility of love is precisely its strength. Love is a sign, it's there, it manifests itself as evidence. And what love affirms (at the opposite end of the spectrum from jouissance) is the /// reciprocity : there is Unity in love, we are one with the other, and this Unity rests on the reciprocity of the feeling of love, which is not provable, to be proved, but is posited as an evidence and a credo. How can love be a sign since the jouissance of the Other is not a sign as a sign of love ? How can love always be reciprocal when there is never sexual intercourse ?

We need to measure here how far we've come since the seminar on Le Désir et son interprétation. Lacan now integrates love, which he had previously greeted with great suspicion, into his discourse and analytical thinking. Originally, love had come from Fairbairn to dismantle the whole Freudian analytic of the libido : well, love itself, Lacan suggests, has its symptomatic, which overlaps with that of jouissance, but differs from it at the same time.

.Throughout the Seminar XX, Lacan will navigate between two unthinkables, on the one hand the unthinkable of jouissance (there is no sexual relation, and so the jouissance of the Other is not the sign of love, but what then is it the sign of ?), on the other hand the unthinkable of love (love is a sign, and it is always reciprocal, but how can it be a sign and always reciprocal, if the jouissance of the Other is not the sign, and is not the visible witness of this reciprocity ?).

The strategy is going to consist in questioning what, in either case, manifests itself as a sign, what it implies, for jouissance, for love, to " make a sign " : in other words, Lacan restarts, freshly, the question of what it is to be the signifier.

III. The function of the signifier

The Saussurian model and the Lacanian model : linguistics and linguistics

We need to open a parenthesis here and recap Lacan's path in relation to linguistics. Lacan starts from Saussure's definition of the sign in the Cours de linguistique générale5. The sign is made up of two elements of different natures: the signifier, on the one hand, which constitutes the material part of the sign (the sound it makes when pronounced, its design when written6), and the signified, on the other hand, which constitutes its immaterial part (what the sign means, what it refers to in reality). Between the signifier and the signified, there's a cut, which Saussure refers to as the semiotic cut. With this cut, Saussure theoretically postulates that there is no necessary relationship, no immediate connection between signifier and signified. This is what we call the arbitrariness of the sign. A priori, any idea, any signified, can be signified by any sound, any assembly of letters. Language is an arbitrary code : this is demonstrated by the variety of languages humanity shares.

While constantly referring to it, Lacan would nonetheless distance himself profoundly from this definition of the sign. What he retained from the Saussurian system was its configuration, its topology. At the top, the signifier; at the bottom, the signified; between the two, the semiotic cut, which Lacan identifies with symbolic castration. But Lacan increasingly rejects both the difference in nature between signifier and signified, and the idea that the sign is arbitrary: what differentiates the signifier from the signified is not its nature, but its position, above or below the bar of castration. What motivates the sign is not the arbitrariness of a code, but the expression of a demand7 for love. /// and, in the failure of this demand, the declension of a symptomatic of jouissances.

In other words, with Lacan, there are now only signifiers, whose function depends on position. This position must be thought of as a movement : a demand carries the signifier upwards, towards the expression ; then this signifier falls, is repressed below the bar. Can we even speak of function? The most important thing is the configuration and the movement it enables.

.At heart, the problem of the signifier's function is a problem of linguistics. For the psychoanalyst, language is not a code that delivers information it is that in relation to which, and with which, the speaking subject defines itself as subject : the signifier is therefore defined first as the expression of a subject, as supported by a subject. Then there's the effect this signifier produces, what it aims at and what it misses. Above the bar, the signifier formulates current discourse8 below the bar, the signifier bears the traces of the unconscious. It is to this movement of speech that psychoanalysis is attentive : Lacan defines this field of attention, in contrast to linguistics, as a " linguisterie9 ", where we must understand a form of assumed linguistic cuistrerie, which would flirt with something like a n'importe quoi du langage : because it's through this n'importe quoi that we gain access to what's going on behind the bar.

This attention, this linguistics, is guided by a formula : " That which is said remains forgotten behind what is said in what is heard " (p. 20). First of all, there is what is heard: everyday speech, the clear and distinct utterance of the signifier as a conscious (and often insignificant) message. But in what is heard, something is said : something else is signified, which comes from deep within the subject and has to do with its demand. " Ce qui se dit " is the unconscious demand expressed in " ce qui s'entend " : this demand remains under the bar, below the current discourse.

Finally, behind " ce qui se dit ", in withdrawal from this withdrawal, something remains forgotten : it's the fact that we say, that is, the reason for this gushing power of saying, the reason for this demand, this movement. Attention to this reason is the linguistics of the psychoanalyst, who never forgets that there is there not only " what is said ", but a saying at work, a subject expressing itself through this saying.

This should not be seen simply as a Lacanian system of the signifier, as one theory among other theories. This conception, this representation of the signifier, not as an element in a structure, but as a trajectory in a device that posits an interception (" reste oublié derrière ") and its lifting, is based not only on the Freudian discovery of a discourse of the unconscious, but upstream of this discovery, on the whole classical culture of eloquence, and more precisely the mutations in the relationship to eloquence introduced by the Enlightenment.

It's not just a theory of the Lacanian system of the signifier, but a theory among other theories.

Tiepolo's Triumph of Eloquence

To make this point, we'll look at a fresco Tiepolo painted in 1724 on the ceiling of the ballroom at Palazzo Sandi in Venice. The Sandis were a family of lawyers from Feltre, in western Veneto. At the end of the 17th century, they were annobled /// by the Republic of Venice, and from then on exercised the function of judges. The fresco they commissioned from the young Tiepolo enshrines their social ascent through the power of eloquence.

In the center of the ceiling, in a swirl of yellow light, appears Minerva helmeted and brandishing a glaive above a cloud to the right, in the brightest core of the swirl, but slightly set back, Mercury, recognizable by his winged sandals and helmet, appears to be stumbling. On all four sides, four mythological scenes depict the powers of eloquence. If the viewer places himself so as to see the most developed scene at the bottom, where Amphion plays the lyre and, through the power of his poetry alone, builds the walls of Thebes, he will see, to his left, Bellerophon riding Pegasus to strike down the Chimera: this is, since Alciat10, an allegory of prudence and virtue, enabling triumph over more powerful or dishonest adversaries. The viewer must turn around to discover Orpheus descending into the Underworld, holding a violin and guided by a blindfolded Cupid: Orpheus attempts to snatch Eurydice from death in front of Cerberus, the three-headed dog, Pluto and Proserpine, masters of the underworld, and the three Fates, who hold the spindle that spins the thread of life. Finally, on the right-hand side of the ceiling, Hercules Ogmien is the Hercules mentioned by Lucien in his " Preface to Hercules ", who borrows his lion's skin from Heracles like Ogmios, the Gallic god of eloquence, Hercules restrains men with golden chains protruding from his mouth.

.

The young Tiepolo may have been inspired for this composition by the ceiling of the Hall of Olympus, painted in 1560 by Veronese at the Villa Barbaro in Maser, a paladian villa on the northern outskirts of Venice11. Veronese had already imagined a concentric system, with a golden nimbus in the center, on which an allegorical figure of divine wisdom stands out, then, behind a circle of clouds, seven Olympian gods arranged in a crown around her, including Venus with Cupid, and Mercury holding the caduceus. This configuration is also found in Tiepolo's work, which depicts a nebulous golden ring in the sky where Minerva sits and Mercury swirls. Tiepolo's four allegorical scenes replace Veronese's crown of Olympian gods, but the concentric arrangement remains the same. The truly original invention lies in the walls of Thebes, which are not confined to the crown of allegories, but delimit in the center, for the entire composition, an entrenched, invisible, protected space. To his master's shadowless epiphany, Tiepolo adds this central blind spot, this space of invisibility.

In this center is represented the reason for saying, that is, both its divine principle and its hidden spring. All around the walls of Thebes, the fortress of discourse, the four allegorical scenes of the power of eloquence unfold on the four sides, that is, what is said in what is heard, what is signified by allegory. Finally, these scenes are seen by the spectator on the floor beneath the painted ceiling, in the hubbub of what is being said. /// hears.

The play of the signifier is thus exposed theatrically, from its divine or hidden principle, from Minerva and Mercury or from the entrenchment of the walls of Thebes. It both exposes and withdraws itself: it is no longer the serene representation of the peaceful sovereignty of divine Wisdom; in the ring of fire, Minerva is off-center, Mercury is swept away, a darker cloud mingles with the luminous cloud. The logic of the swirl introduces the instability of movement and the anxiety of a march that makes and unmakes. But above all, this whirlwind is placed above the walls of Thebes under construction, hovering over, or projecting from an entrenchment : it's a thwarted movement, the very play of the signifier.

From this tumultuous center, the force of eloquence (in other words, the signifier) crosses the semiotic bar, which is represented here by the belt of allegorical scenes, where the power of speech is declined in the battles it fights. The signifier finally reaches the ear or eye of the spectator, caught in the insignificance of everyday speech. The center of the ceiling is the reason for the signifier, which shows itself but withdraws, which radiates but is troubled. The reason for " qu'on dise " can just as easily remain forgotten : to pay attention to it, the viewer must look up, distract himself from the current discourse.

Allegorical structure and whirlwind device : the failure of the signifier

The allegorical scenes answer each other in pairs on the short sides is represented the fighting strength, so to speak military, of eloquence. Bellerophon overcomes the Chimera, Hercules shackles his adversaries. Here, the signifier hits the nail on the head. The Chimera and Hercules' prisoners have no chance of escaping their conqueror: this is the simple power of eloquence, and it's only this power. Tiepolo would take up the figure of Bellerophon in another ceiling fresco depicting an allegory of glory, in Venice's Palazzo Labia12. The Oggian Hercules, on the other hand, is a rare figure however, the gold chain motif is found in a fresco from the Villa Loschi Zileri dal Verme in Biron near Vicenza13.

To the large sides is reserved the noblest force, the poetic and musical power of eloquence, with the representation of the first poets, Amphion and Orpheus. And here, paradoxically, the effectiveness of the signifier is much less obvious! Orpheus has defeated Cerberus, Pluto and Proserpine, the Fates themselves but Orpheus won't bring back Eurydice. And Amphion moves the stones, but what a mess the image is, as if the wall of Thebes were collapsing as it was being built. The noble signifier misses its mark: its nobility, its poetic prestige, lies precisely and paradoxically in this failure, where aesthetic enjoyment is at stake.

The device formed by this stage area says something else about the signifier : Orphée dit de quoi le signifiant est le signe, et c'est de l'amour : Dans le tourbillon d'or central, les figures emportées dessinent une farandole qui indique un enchaînement, de Minerve à Mercure, de Mercure à Cupidon, de Cupidon à Orphée. Amphion, for his part, tells how the signifier signifies : under the action of his lyre, " what is heard in what is said " is figured by the stones moved and flying to build the walls of Thebes. Poetry moves stones, shifting and rearranging them. The ceiling of the Palazzo Sandi ballroom, for instance, not only expresses the triumph of eloquence, which consecrated the glory of these new Venetian aristocrats it posits the central articulation of love to the signifier : love is what the signifier aims at (the pink novel of the object-seeking) ; it is what his reason tends towards, what Orpheus sings ; but the means, the production of the signifier have nothing to do with love they have to do with Amphion and his entrenchment. Tiepolo's genius consisted in introducing this disorder, this non-coincidence of the effects of eloquence into the representation of its triumph, in substituting for the epiphanic structure of a conquered Olympus (this was the object of his commission) the swirling dynamics of a signifier that does not produce what it aims at, and gives pleasure through the instability it thus maintains and this is to understand and represent exactly what eloquence does.

.Amphion moving stones not only figures the power of poetic speech ; it tells how this power works : by rearrangement. What is poetry ? Basically, it's stones, it's the naive simplicity, the very stupidity of stone. But the effect of poetry is a displacement of stones: not the sublime construction of Thebes, but the cloud of stones building it, and the voluble edsordre it produces. For the signifier, there is no definitive architecture. At any given moment, " you can do lots of things with it " :

" Yet it is by the consequences of the said that the said is judged. But what we do with what is said remains open-ended. For we can do all sorts of things with it, just as we do with furniture, from the moment, for example, that we have endured a siege or a bombardment. " (ibid., p. 20)

The signifier is caught up in a process. It comes from saying and goes towards the consequences of saying. It is judged and enjoyed on this journey. In this journey, the siege and bombardment of symbolic castration is replayed, through which the subject has come to speech, and a saying has been made possible. The signifiers uttered by the subject are the furniture salvaged from this founding catastrophe you can make lots of things out of them that's what Amphion imagines, making the stones fly to build the walls of Thebes. Amphion saves the furniture in his discourse, he builds, he tinkers with the scattered materials of the unconscious.

IV. The sign of love as " quarter turn "

In the journey of the signifier, which aims and misses its effect, the miss is somehow recycled in advance to produce additional meaning. Meaning is communicated, duly addressed, and another meaning is produced and put into circulation by the tape, the production of which has to do with jouissance, what I have provisionally called, in response to Tiepolo, aesthetic jouissance. In this unstable, subterranean production, the signified effects of love circulate.

Changer de raison : un poem by /// Rimbaud

Lacan offers a very strange and somewhat unexpected example, which he borrows from Rimbaud's Illuminations . The poem is entitled " A une raison " :

One tap of your finger on the drum unloads all the sounds and begins the new harmony.

One step from you, and the new men rise and march.

Your head turns away - the new love! Your head turns back, - the new love !

" Change our lots, sift the plagues, starting with time ", these children sing to you.

" Raise anywhere the substance of our fortunes and wishes " we beg.

Arrival of always, who will go away everywhere.

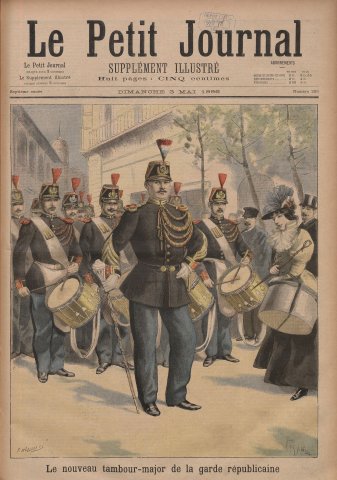

Rimbaud apparently evokes a military parade. At the head of the parade, he looks first at the drum major, who gives the signal to the other drums and bugles in the regiment (even though the drum major doesn't normally hold a drum himself). On May 3, 1896, Charles Gourdin, the new drum major of the Republican Guard, made the front page of the Petit Journal. It read: " Le maréchal des logis-chef Gourdin, nouveau tambour-major, est considéré par ces dames comme le plus bel Apollon de France ! It's true that his handsome height (1m93) and impeccable uniform are imposing, and make the milliners' hearts tumble. " Rimbaud doesn't specifically mention the aptly named Gourdin here, but it's definitely this spring of seduction we're talking about.

At the given signal, the troupe shakes off and the parade begins. Then, according to a well-ordered choreography, the Tambour turns his head to one side, and with him all the men who follow him. Rimbaud, the spectator, can no longer see his face. Some time later, he turns his head again, and his face becomes visible again.

The poet addresses the drum major as " to a reason " : reason to love, justification of the springs of his own desire. He describes his magnetization to the face that arouses his desire, then the disappearance of the face that frees him and makes him available for a new love, then the return of the face, which magnetizes his gaze once again. It's the face of a man who commands other men, who orders their destiny: the music here metaphorizes or recalls the order of battle, which the captain can change for each of his men. As the drums roll, Rimbaud believes he hears the young men marching in prayer to their leader: a carefree, thoughtless prayer, with each shake of the head that the major gives his troop, that the fate of his men may change, that he may be elevated. Each person's destiny is compared to a grain, beaten by a scourge and then sifted, so that it falls, as one falls on the field of honor, and through this death raises the " substance of our fortunes and wishes ". As in the Gospel parable " Si le grain ne meurt ", the fall (the sifting)à is necessary for elevation (" elevates our substances ") and redemption. The end of the poem abymes the procession of the signifier : this poem is not the address, the singular sending of a message ; it has the general value of a parable, it is an " arrival of always " likewise, it is not aimed at an addressee : it " will go everywhere ".

However, just as in Le Triomphe de l'éloquence the structure /// concentricity is distorted into a whirlwind to explode the non-coincidence of signifier effects, similarly in " A une raison " the prayer is mad, but the tone is carefree death lurks, yet it's only a joyful parade the choreography explodes a beautiful order, but a secret disorder runs through it : all the words are there, but their order is disturbed it makes no sense to say that we sift the flails in principle, what we sift is the grain that has been threshed by the flails first we use the flails, then the sieve. "Sifting the flails" changes the order in which things must be done, and responds in advance to the injunction of the men on parade: the first change is the change of time, of the order of succession in the process. The movement of turning heads is matched by a change in order. The poet makes this almost mechanical change the sign of love, which has slipped from Rimbaud's gaze on the drum major to the drum major's exchange with his men. Several images are then superimposed, that of the beating of drumsticks riddling the surfaces of drums, that of flails beating wheat, perhaps also the more subterranean one of the sado-masochistic whip, another scourge.

Lacan formulates this change :

" Love, in this text, is the sign, pointed out as such, of what one changes reason, and this is why the poet addresses this reason. We change reason, that is to say - we change discourse. " (Ibid.)

Rimbaud expresses here what the sign of love is, which has nothing to do with the jouissance of the Other. There's this tourniquet heads turn, the gaze is released then taken up again, and with the gaze the scopic drive, the rise of desire and its demand. Each time, this demand is related to a reason, to be found in the choreography of the parade, but just as much in the prayer of the marching men, or in the poet's desire for love, formulated in the previous verse. This change in reason, amounts to a pivoting of the heads in the parade, which Lacan compares to the quarter-turn in the arrangement of the four constituent elements of the four Lacanian discourses.

The four Lacanian discourses

Pivoting heads in the parade, pivoting signifiers in the carousel of Lacanian discourse : the comparison is abrupt and may seem arbitrary. It's based on the research Lacan developed in the seminar on L'Envers de la psychanalyse, three years earlier14. The signifier cannot be defined without taking into account the environment in which it is embedded: the signifier manifests itself in discourse. Discourse is the signifier's means of expression. What is a discourse? Lacan defines it in terms of four elements. Discourse begins with a signifier that expresses itself, noted as S1 and called the master signifier. Discourse is addressed to someone: S1 targets the big Other. From the point of view of discourse, the big Other is defined as the set of signifiers available in language, what Lacan calls the battery of signifiers and notes S2. S2 is also " the already structured field of knowledge15 ". S1 aiming at S2, pointing with an arrow towards S2, is the visible, emerging structure of the basic discourse. It itself rests on an underlying structure, set back from the discourse but supporting it: S1 is the signifier that expresses itself, but it expresses itself from a subject, from the speaking subject formatted by symbolic castration, and marked for this reason with a barred S, $. On the other hand, what S1 is aiming for when it points to the S2 battery of signifiers, a possible meaning, a message likely to be heard, understood by the big Other, well, S1 to /// the spleen. By definition, the big Other cannot be reached, and so the signifier fails to produce its effect in S2. It fails, but something always remains, and that's how, haphazardly, communication still works. In other words, in the transmission from S1 to S2, there is loss, and this loss is productive, and Lacan designates it as a, or in other words as the plus-de-jouir, the extra jouissance that makes up for the failure of communication S1 → S2. This little a, in the basic device of Lacanian discourse, is placed under S2, as it is the product of loss when S1 fails to reach its goal in S2.

S1 → S2

- -

$ a

This basic device, which Lacan calls the Discourse of the Master, is not, however, the only possible device : you can rotate its four elements by a quarter turn, and with each new quarter turn you get a new type of discourse. In fact, the possibilities are not infinite the most important rotation is that which raises the subject $ from its position as the foundation from which the signifier S1 expresses itself, placing it at the top left in the position of agent, addressing S1, the master signifier this is the discourse of the hysteric, the study of which opened the way to the possibility of a psychoanalytic discourse. Psychoanalytic discourse is the third discourse, obtained at the cost of a new quarter-turn, which gives voice to a, to the loss of meaning of the signifier S1, and to the more-than-joy thus obtained. In the analyst's discourse, a is in the position of agent, relying on the battery of S2 signifiers of which it is the fall, the remainder, the scrap. The psychoanalyst postulates that a targets the subject $, that it is to him that he addresses and speaks ; a targets the subject as bearer of the master signifier S1, as speaking subject, who says things that a reconfigures to make something else heard.

The hysterization of amorous discourse

But the quarter-turn that configures the analyst's discourse from the hysterical discourse is a theoretical quarter-turn, which does not correspond to a real situation, in life. The quarter-turn in life is from the master to the hysterical and from the hysterical to the master. The analyst's discourse is a metadiscourse that makes it possible to account for this quarter-turn, at the cost of a quarter-turn that the analyst decides upon and constructs. As for the fourth discourse, which must be logically postulated from the other three, it places S2, knowledge, in the position of agent : it's the discourse of the university, which plays a priori no role in the living situations with which the psychoanalyst is confronted.

.So everything plays out, in life, between the discourse of the master and the discourse of the hysterical. If we return to Rimbaud's poem, and the swivel of heads in the parade, what's at stake in the change Rimbaud notes in the scansion " le nouvel amour " is a hysterization of discourse : the description of the procession (the deployment of the S1 signifier) is followed by a cry from the heart: it's the barred subject who speaks, defiantly or bitterly, or seeking to put on a brave face, a subject barred and rebarred in any case by the averted and upturned head of the one he's looking at. This is no longer a reciter addressing an audience (S1 → S2), it's a wounded heart speaking to itself ($ → S1).

Love manifests itself as a sign when we change discourse, when the subject changes discourse regime, when the subject's position in discourse changes. This change consists in a hysterization16. In other words, the sign of love is not a direct sign (a content that would be directly signified), but a change in the economy of signs, in the /// the semiotic apparatus that governs the production of signs : the sign of love is when $ speaks.

Let's pause for a moment to consider the singularity of this example borrowed from Rimbaud, which breaks radically with the old, pre-classical understanding of love. What's new here is not that love is born of a look : the whole Petrarchan tradition of love poetry is nourished by the scene of the innamoramento, where the poet is trapped by his Lady's gaze. The fact that the love in question here is homosexual is nothing new either : Petrarchanism feeds onMarsilius Ficino's commentary on Plato's Banquet, which the neo-Platonic philosopher dedicates to his " very sweet Jean ", the young Jean Cavalcanti, who granted him " from his celestial gaze a prodigious sign17 " ; one could even say that the love of the Platonic banquet, which founds the lyrical structuring of Western poetry in its articulation with philosophy, is originally a homosexual love. There's nothing new in change of reason either. It's important to understand here what changes it's not the person Rimbaud is looking at, here still the parade drum major, but the regime of discourse. There is a change of regime in the discourse, from ordinary reason to amorous unreason, a loss of control in the economy of discourse precipitates a "beckoning", the reason of amorous beckoning replaces the reason of controlled discourse. This disturbance of discourse is part of a whole tradition of lyrical disorder, which speaks of love through the stammering of speech.

So what's new in " A une raison ", and deeply disturbs us in the so-simple exclamation, in the so-seemingly-naive scansion brought about by this refrain, " le nouvel amour " ? Isn't it precisely this blandness, this reduction of love to the limit of stupidity ? Love would be what's on display here, in front of a vulgar fashion show, in this fashion show a furtive glance, probably without a future, and from this glance a midinette's exclamation. The transgression here is not so much the expression of a homosexual desire as of a pink novel desire, a milliner's desire from the Petit journal, l'amour would be that chromo there, deploying a fine display of signifiers, but just a display.

Notes

. . ///Ronald Fairbairn, Psychoanalytic Studies of Personality, London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1952.

Lacan, Le Séminaire, book VII, Le Désir et son interprétation [1958-1959], Seuil, 2013.

Denis de Rougemont, L'Amour et l'Occident, Plon, 1956, 10-18, 1972.

Lacan, Le Séminaire, book VII, L'Éthique de la psychanalyse [1959-1960], Seuil, 1986, p. 12.

Ferdinand de Saussure, Cours de linguistique générale [1916], Payot, 1972, 1982, I, 1, §1, " Signe, signifié, signifiant ", p. 97, and §2, " L'arbitraire du signe ", p. 100.

This written form of the signifier poses a problem in Saussure's system, for whom the transcription of the phoneme is transparent. Questioning this transparency is one of the foundations of Derridean deconstruction. See Jacques /// Derrida, De la Grammatologie, Minuit, 1967, I, 2.

The expression of demand is modeled by the desire graph. See Le Désir et son interprétation, op. cit., 1st session, p. 20-28.

" Write the disc-current ", says Lacan in the 3rde session of the seminar Encore (op. cit., p. 34).

Lacan coined the word during the 2nde session of the Encore seminar (op. cit., p. 20). But the idea was already in the making in Seminar XVIII, D'un discours qui ne serait pas du semblant, where Lacan responded to linguists' attacks against an allegedly " metaphorical " use of linguistics (p. 41sq), an unscientific use intended for ignoramuses (p. 45sq.).

André Alciat, Emblematum libellus, Paris, Ch. Wechel, 1534, p. 108, and numerous later editions. See Utpictura18, notices A4237 and A0913.

Chantal Eschenfelder, Tiepolo, Cologne, Könemann, 1998, p. 10 (Veronese influence), 15 (fresco description), 16-17 (reproduction).

Chantal Eschenfelder, op. cit., p. 70-71 and Utpictura18, record A4044, compare with B7522.

Op. cit., p. 32 and 35 and Utpictura18, notice B7521. The conjugal bond is expressed at the center of this composition at least twice: the young woman gives her right hand to her husband, granting him her trust. Reciprocally, the young man gives his heart to the young woman, and binds her by this gift. Marital harmony is thus based on a reciprocal relationship, but one that is not perfectly symmetrical. The husband declares his love and expresses his desire, but the wife does not. The wife confides in her husband, abandons herself and relies on him, while the man does not. The chain of the marital bond, which can be compared to the chain on the Oggian Hercules in the Sandi Palace, painted ten years earlier, is loose for the husband, but stretched around the neck of the wife, whom the husband draws to him and holds by this means. The standing husband holds the chain and moves forward; the seated wife steps back. In the lower right, Cupid, recognizable by his blue wings and the quiver resting on his lap from which a feather emerges, is coaxing a dog, symbolizing the fidelity that guarantees marital harmony. Opposite the white dog, from beneath the beautiful yellow dress, emerges the tip of a seductive shoe, as white as the dog, whose pale spot catches the eye: even submissive and bound by marriage, the woman remains a temptress. The whole composition, which appears peaceful and almost dull at first glance, is shot through with contradictory tensions Cupid prowls, but his game with the dog disarms him the young woman gives her hand but plays with her foot the young man gives his heart but pulls the chain.

.

The four links of the chain joined by the husband's hand are depicted in a way that strongly evokes the Ogmian Hercules painted ten years earlier. We thus see the articulation between the power of eloquence and the signs of love, which have nothing to do with the jouissance of the Other (the woman), but with something between submission and fusion.

Lacan, Le Séminaire, book XVII, L'Envers de la psychanalyse [1969-1970], Seuil, 1991.

L'Envers de la /// psychoanalysis, op. cit., p. 12.

Lacan formulates things more cautiously, and as a result necessarily more complicated : " Well, I'll say now that of this psychoanalytic discourse there is always some emergence at each passage from one discourse to another. " (p. 20) In fact, the passage is always from the discourse of the master to the discourse of the hysteric, and this passage itself calls for its interpretation by the analytic discourse.

Marcile Ficin, Commentary on Plato's Le Banquet, Les Belles Lettres, 2002, dedication p. 2.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Les signifiants du désir » , Séminaire LIPS, automne 2020, université d'Aix-Marseille.

Littérature et Psychanalyse

Archive mise à jour depuis 2019

Littérature et Psychanalyse

Le Master LIPS

Séminaire Amour et Jouissance (2019-2021)

Amour et Jouissance

Jouir et Posséder

Vers l'amour-amitié

Les signifiants du désir

50 nuances de Grey

Duras, la scène vide