[54]

Butcher

I don't know what to say about this man. The degradation of taste, color, composition, character, expression, drawing, has followed step by step the depravity of morals. What do you want this artist to throw onto the canvas? What's in his imagination. And what's in the imagination of a man who spends his life with the lowest-class prostitutes? The grace of his bergères is the grace of the Favart in Rose et Colas1; that of his goddesses is borrowed from the Deschamps2. I defy you to find in an entire countryside a blade of grass from its landscapes. And then a confusion of objects piled on top of each other, so out of place, so disparate, that it's less the picture of a sensible man than the dream of a madman. It was from him that it was written:

...velut aegri somnia, vanae

Fingentur species : ut nec pes, nec caput3...

[55] I dare say this man really doesn't know what grace is; I dare say he's never known the truth; I dare say the ideas of delicacy, honesty, innocence, simplicity, have become almost foreign to him ; I dare say that he has not seen nature for a moment, at least that which is made to interest my soul, yours, that of a well-born child, that of a woman who feels; I dare say that he is without taste. Among the infinite proofs I would give, one will suffice: in the multitude of figures of men and women he has painted, I defy anyone to find four of a character suitable for bas-relief, still less for statue. There are too many mines, little mines, mannerisms, afféterie4 for a severe art. He may show them to me naked, but I always see the red, the flies, the pompoms, and all the fanfiole5 of the toilet. Do you think he ever had something of Petrarch's honest and charming image in his head,

E'l riso, e'l canto, e'l parlar dolce, humano 6?

Those fine, loose analogies that call objects to the canvas and bind them there by imperceptible threads, on my God, he doesn't know what it is. [All his compositions make an unbearable fuss to the eyes7.] He's the deadliest enemy of silence I know; he's at the prettiest puppets in the world; he'll fall to illumination8. Well, my friend, it was when Boucher ceased to be an artist that he was [56] appointed premier peintre du roi9. Don't think that he is to his genre what Crébillon le fils is to his10. It's more or less the same mores, but the writer has a completely different talent from the painter. The only advantage the latter has over the other is a fecundity that never runs out, an incredible facility, especially in the accessories of his pastorals. When he makes children, he groups them well; but let them remain frolicking on clouds. In all this innumerable family, you won't find one to employ to the real actions of life, to study his lesson, to read, to write, to tiller hemp11. They are romantic, ideal natures, little bastards of Bacchus and Silenus. Sculpture could easily accommodate these children on the rim of an antique vase. They're fat, chubby, chubby. If the artist knows how to knead marble, we'll see. In a word, take all the paintings by this man; and there will hardly be one to which you can't say like Fontenelle to the sonata: Sonate, que me veux-tu12? Tableau, what do you want from me? Wasn't there a time when he was taken with the fury of making Virgins13? Well, what were her Virgins? Sweet little chicks. And her angels? little libertine satyrs. [57] And then, in his landscapes, there's a greyness of color and a uniformity of tone that would make you mistake his canvas, two feet away, for a piece of turf or a layer of parsley cut into squares. He's no fool, though. He's a fake good painter, as one is a fake beautiful mind. He has no thought of art; he has only the concetti14.

8. Jupiter transformed into Diana to surprise Callisto (#002293)

From the same.

Oval painting approximately 2 feet high, by 1 1/2 feet wide.

In the center, we see the metamorphosed Jupiter; he's in profile; he's leaning over Calisto's lap15: with one hand he's trying to gently part her linen; this hand is the right one. He passes his left hand under her chin. Two busy hands. Calisto is painted from the front; she faintly pushes away the hand that is busy revealing her. Below this figure, the painter has spread drapery and a quiver. Trees occupy the background. To the left, we see a group of children playing in the air; above this group, Jupiter's eagle.

But do mythological characters have other hands and feet than we do? Ah! La Grenée, what do you expect me to think of this, when I see you right next to me, and am struck by your firm color, the beauty of your flesh, and the truths of nature that pierce every point of your composition? Feet, hands, arms, shoulders, a throat, a neck, if you need them as you have [58] fucked them sometimes, the Grenée will provide you with them; for Boucher, no. Past fifty, my friend, there's hardly a painter who calls the model; they're all about practice16, and Boucher's at it: these are his old turned-and-turned figures. Hasn't he already shown us a hundred times and this Calisto, and this Jupiter, and this tiger skin with which he's covered17?

9. Angélique et Médor (#001216)

From the same.

Table of the form and size of the preceding.

The two main figures are placed to the right of the viewer. Angélique18 is lying nonchalantly on the ground and seen from the back, except for a small portion of her face that is caught and makes her look moody. On the same side, but on a deeper plane, Médor, standing, seen from the front, his body bent over, brings his hand to the trunk of a tree, on which he is apparently writing Quinault's two verses, those two lines that Lulli set so well to music19, and which give rise to all Roland's goodness of soul to show up and make me cry when the others are laughing :

Angélique commits her heart,

Médor is victorious.

Amours are busy surrounding the tree with garlands. Médor is [59] half-covered in a tiger skin, and his left hand holds a hunter's dart. Below Angelique imagine drapery, a cushion-a cushion, my friend! that goes there like the carpet in La Fontaine's Nicaise20; a quiver and arrows; on the ground a fat Amour lying on his back and two others playing in the air, in the vicinity of the tree confident of Médor's happiness; and then to the left landscape and trees.

It pleased the painter to call this Angélique et Médor, but that will be all that pleases me. I defy anyone to show me anything that characterizes the scene and designates the characters. Oh dear, all you had to do was let yourself be led by the poet. How much more beautiful, grander, more picturesque and better chosen is the setting for his adventure! It's a rustic lair, it's a secluded place, it's the abode of shadow and silence21. That's where, far from any intruder, you can make a lover happy, not in broad daylight, out in the countryside, on a cushion. It's on the moss of the rock that Médor engraves his name and that of Angélique.

This doesn't make common sense; little boudoir composition22. And then no feet, no hands, no truth, no color, and still parsley on the trees. See or rather don't see the Medor, his legs especially; they're of a little boy who has neither taste nor study. Angelique is a little tripière23. O the dirty word! Okay, but he paints. Round, soft drawing and flabby flesh. This man only picks up the brush to show me nipples and buttocks. I'm quite happy to see them, but I don't want them shown to me24. [60]

10. Two pastorals (#002292)

From the same

Boards 7 feet 6 inches high, by 4 wide.

Well, my friend, have you ever understood anything? In the center of the canvas, a shepherdess, Catinon25 in a little hat, driving a donkey; we see only the animal's head and back. On the donkey's back are clothes, luggage and a cauldron. The woman holds her animal's halter in her left hand, and a basket of flowers in her right. Her eyes are fixed on a shepherd seated on the right. This great blackbird finder is on the ground; on his lap he has a cage; on the cage are small birds. Behind this shepherd, further in the background, a small farmer stands and throws grass to the little birds. Below the shepherd, his dog. Above the peasant, even further back, a stone, plaster and joist factory, a sort of sheepfold, planted there somehow. Around the donkey, sheep. To the left, behind the shepherdess, a rustic barricade, a stream, trees, landscape. Behind the sheepfold, more trees and landscape. At the bottom, on the front, quite to the left, again a goat and sheep, and all jumbled together with pleasure: it's the best lesson to give a young pupil on the art of destroying any effect by dint of objects and work.

I'm not telling you anything, neither about the color, nor the typefaces, nor the other [61] details; it's as before. My friend, is there no police at this Academy? In the absence of a commissioner of paintings to prevent this from entering, wouldn't it be permissible to kick it along the Salon, up the stairs, into the courtyard, until the shepherd, the shepherdess, the sheepfold26 the donkey, the birds, the cage, the trees, the child, the whole pastoral was in the street? Alas! No, it must remain in place; but indignant good taste nonetheless makes the brutal, but just execution.

11. Autre Pastorale (#001208)

From the same.

Same size, shape and merit as the previous27.

And you think, my friend, that my brutal taste will be more forgiving for this one? Not at all. I can hear it screaming inside me: Hors du Salon, hors du Salon. No matter how many times I repeat Chardin's lesson: De la douceur, de la douceur28... he gets depressed, and shouts only louder: Hors du Salon.

This is the image of a delirium. On the right, on the front, still the shepherdess Catinon or Favart29, lying down and asleep, with a good fluxion over her left eye30. Why also fall asleep in a damp place, a little cat in her lap? Behind this woman, starting from the edge of the canvas, and sinking successively, through different planes, and turnips, and cabbages and leeks, and an earthen pot, and a seringa in this pot, and a large quarter of stone, and on this large quarter of stone a large vase of flower garlands, and trees, and greenery, and landscape. Opposite [62] the sleeper, a shepherd stands contemplating her; he is separated from her by a small rustic barricade: in one hand he carries a basket of flowers; in the other he holds a rose. There, my friend, tell me what a kitten is doing on the lap of an unsleeping peasant woman at the door of her thatched cottage. And isn't this rose in the peasant's hand an inconceivable platitude? And why doesn't this simpleton bend down, take a kiss, or be ready to kiss a mouth that's there? Why doesn't he come forward slowly? But do you think that's all the painter wanted to put on his canvas? Of course not! Isn't there another landscape beyond? Isn't there the smoke rising behind the trees, apparently from a nearby hamlet?

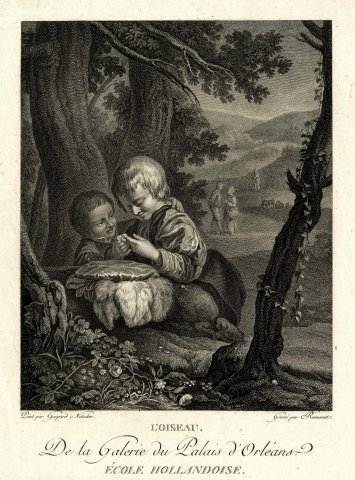

A naughty little painting by Philippe d'Orléans31, where we see the two prettiest little innocent children possible, annoying with the tip of their finger a sparrow placed in front of them, stops, gives more pleasure than all that: it's that we can see from the little girl's expression that she's playing mischievously with the bird. Same confusion of objects, and same falseness of color as in the previous one. What an abuse of brush facility! [63]

12. Four pastorals

From the same.

Two are oval, and all four are about 15 inches high by 13 wide.

I am just, I am good, and I ask no better than to praise. These four pieces form a charming little poem. Write that the painter once in his life had a moment of reason. A shepherd ties a letter around a pigeon's neck; the pigeon leaves. A shepherdess receives the letter, reads it to one of her friends and is given an appointment. She is there, and so is the shepherd.

The first one. (#001211)

To the viewer's left, the shepherd sits on a piece of rock. He has the pigeon on his lap, tying up the letter. His staff and dog are behind him; at his feet he has a basket of flowers, which he may be offering to his shepherdess. Further to the left, a few pieces of rock. To the right, greenery, a stream and sheep. Simple and wise, all that's missing is color.

The second one (#001215)

The messenger pigeon, the Mercury bird, can be seen arriving on the left; it's coming with a rush. The shepherdess, standing with her hand resting against a tree in front of her, spots him between the trees; he fixes her gaze; she has quite the air of impatience and desire. Her position, her action are simple, [64] natural, interesting, elegant. And that dog who sees the bird coming, who has both paws raised on a bit of terrace, who has his head raised towards the messenger, who barks at him in joy, and who seems to be wagging his tail, he is imagined with wit. The animal's action marks a long-established gallant trade. On the right, behind the shepherdess, we see her distaff on the ground, a basket of flowers, a small hat with a kerchief; at her feet a sheep. Even simpler, and better composed; all that's missing is color. The subject is so clear that the painter could not obscure it with details.

The third one (#021497)

To the right we see two young girls, one on the front and reading the letter, on the shot that follows, her companion. The first has her back to me, which is wrong, as she could easily have been given the physiognomy of her action; it was her companion who needed to be placed this way. The confidence takes place in a solitary, out-of-the-way spot, at the foot of a rustic stone factory, from which a fountain emerges, above which there is a small Amour in bas-relief. To the left, goats, billy goats and sheep.

This one is less interesting than the last, and that's the artist's fault. Besides, this place really was the rendezvous; it's the love fountain. Always wrong color.

The fourth (#021498)

The rendezvous. In the center, toward the viewer's right, the shepherdess seated on the ground, a sheep beside her, a lamb on her lap, her shepherd gently clasping her in his arms and looking at her passionately. [65] Above the shepherd, his tethered dog. Very nice. To the left a basket of flowers. To the right, a broken tree. Still very good. In the background, hamlet, hut, part of a house. It was here that the letter should have been read, and it was at the fountain of Love that the rendezvous should have been set.

Whatever the case, the whole is fine, delicate, beautifully thought out; these are four little eglogues à la Fontenelle. Perhaps the simpler, more naive mores of Theocritus, or those of Daphnis and Chloe, would have interested me more32. Whatever these shepherds do, mine would have done; but the moment before they would not have suspected; instead these knew in advance what would happen to them, and that displeases me, unless it is quite frankly pronounced.

My faith, my dear philosopher, I fear that all this is still a little false in thought as in color. A shepherd and a shepherdess who have succeeded in making a letter carrier out of a pigeon are prodigiously corrupted, all the more so as country love knows none of the hindrances that civil life has placed on this passion: between shepherds, when one loves and is loved, all is said; the considerations of convenience and fortune on which paternal consent depends, and which are the source of unhappy passions in society, do not exist in pastoral life. So why train a pigeon to carry letters? Apparently there's some torrent between the shepherd and the shepherdess, which prevents him in bad weather from going on his errands himself?

And then, however much I may suppose a site and poetic mores, I cannot find any where the pigeon can be letter carrier and commissionaire, if not at the French opera33. A commissionaire has to be clever, deft, careful ; and the pigeon is only innocent. I also think that a shepherdess who has perverted the dove's morals enough to accustom her to this servile and abject employment, would have something else to do, when her lover is beside her, than to hold a lamb in her lap. All these people are from the French opera, where it is customary to spend the precious moments of a rendezvous chanting a madrigal in the ears of one's mistress, or dancing rigaudons around her to express one's love. Ah, how I hate this false genre ! My dear philosopher, you got too angry with this Butcher and then in the midst of your outburst your bonhomie grabbed you, and for fear of being unfair you relented too much. I, who am not as good as you, and who have said no insult to Mr. Boucher, whatever I think of him as you do, I remain ruthless. This is fine, pretty, true even, if you like, but in a false genre and one I abhor.

13. Another pastoral.

Of the same.

It's a standing shepherdess, holding a crown in one hand, and carrying a basket of flowers in the other; she's stopped in front of a shepherd sitting on the ground, his dog at his feet. What does it say? Behind her, on the far left, we see a group of bushy trees, at the top of which, though we're not sure how it got there, is a fountain, a round hole pouring water. These trees apparently hide a rock, but they didn't have to. I've mellowed at little cost; if it hadn't been for the previous four, I might well have said to this one: Hors du Salon; but I'll never grace the next one. [66]

14. Another pastoral.

From the same34.

Oval table approximately 2 feet high, by one foot 6 inches wide.

Will I never get out of these cursed pastorals? It's a girl tying a letter to a pigeon's neck; she's seated, we see her in profile. The pigeon is on her lap, ready for the role, as you can see from its hanging wing. The bird, the shepherdess's hands and lap, are embarrassed by an entire rosebush. Tell me, please, if it's not a rival jealous of killing this little composition, who has stuffed this shrub there. One has to be an enemy of oneself to play such tricks.

The booklet speaks again of a Paysage où l'on voit un moulin à l'eau (#006169). I've been looking for it but haven't been able to discover it; I don't think you'll lose much.

Notes

.One-act comic opera by Sedaine, music by Monsigny, premiered March 8, 1764 at the Hôtel de Bourgogne, illustrated by Boucher's son-in-law Baudouin (#008053). Diderot is mistaken, however, as Justine Favart, also known as Mlle Chantilly, played no role in the play. Grimm therefore corrects, in the Correspondance littéraire, to Annette et Lubin, first performed at the Italiens on February 1er 1762 (13 performances). Favart had co-written Annette et Lubin, after Marmontel. Baudouin also illustrated Annette et Lubin (#007052).

Marie-Anne Pagès born in Paris around 1730, daughter of a ladies' sausage-maker in the cul-de-sac Dauphine, near the passage des Tuileries, had just died in 1764, after having made headlines in the world of fashion. See C. Capon and R. Yve-Plessis, Fille d'Opéra, vendeuse d'amour. Histoire de Mlle Deschamps, Paris, Plessis, 1906.

"Like the dreams of a sick man, phantasmagorias are imagined there, footless, headless that..." (Horace, Art poétique, v. 7-8)

" Affetterie, s. f. The words & actions of an affetted speech; certain manners studied & full of affectation; visible care & full of art in the things one says & does. Affectatio, consectatio nimiæ concinnitatis. Afféterie pure, ridiculous, disgusting, boring. Poppae, the wittiest & most beautiful Lady of her time, first took Nero by his afféteries, & by his caresses. Ablanc. She wanted to lead him by affeteries, & by her caresses, to shameful things. Id." (Trévoux)

Fanfiole is neither in Trévoux, nor in the Dictionnaire de l'Académie. According to the Trésor de la langue française this would be the first occurrence of the word here. Diderot apparently crosses fanfreluche with babiole. The neologism would be taken up by Goncourt.

"Laughter, song and sweet human speech" (Petrarch, Canzoniere, sonnet 249, v. 11).

Added from the Correspondance littéraire.

This is not the meticulous, refined work of medieval illumination, but the assembly-line work of coloring popular images: "Enluminer, se dit particulièrement de ceux qui appliquent des couleures en détrempe avec de la gomme, & sans huile, sur des cartes, sur un éventail, sur un écran [de cheminée]. Les présens des Régens [= professors] à leurs écoliers sont des images enluminées [= des bons points]" (Trévoux)

Boucher succeeds Carle Vanloo, who has just passed away. This is the most prestigious title in the Académie, earning its holder the most important official commissions.

Crébillon fils, a libertine novelist, was the author of Tanzaï et Néadarné (1734), the Êgarements du cœur et de l'esprit (1736-1738) and the Sopha (1742). Diderot parodies him in Les Bijoux indiscrets (1748).

11" Tiller le chanvre, (Econom. rustique.) is an operation which consists in taking the strands of hemp one after the other, breaking the chenevotte, & detaching the filasse by sliding it between the fingers.

In some provinces, all the hemp is spun; in others, it is spun only when there is very little; otherwise, it is crushed.

This is a very time-consuming process, but it's a good way to get the most out of your hemp.

This work is very time-consuming; but it keeps the children busy, and they do it as well as grown-ups. Vsee the article Hemp." (Encyclopédie, XVI, 1765, 329b. Trévoux and the Académie give Teiller or lieu de Tiller.)

The formula is apocryphal. Fontenelle apparently used it to express his exasperation with the instrumental interludes in operas, which delayed the action without delivering any meaning. (Cousin d'Avallon, Fontenelliana, Paris, 1801, p. 56, not very explicit...)

See in particular La Lumière du monde (1750, #003984) and Le Sommeil de l'enfant Jésus (1759, #001800). In the Salon de 1763, Diderot fulminated against the colors of a Nativité by Boucher (#011233).

" *Concetti, s. m. (Gramm. & Rhetoriq.) This word comes to us from the Italians, where it is not taken in a bad light as it is among us. We have used it indiscriminately to designate all the sought-after points of wit that good taste proscribes." (Encyclopédie, III, 1753, 804b, the asterisk indicates that the article is by Diderot.) The word is not in Trévoux, but appears in 1762 in the Dictionnaire de l'Académie: "Mot emprunté de l'Italien. Il se dit des pensées brillantes & sans justeesse."

Callisto was one of the nymphs in Diana's retinue. Jupiter disguised himself as Diana to approach and rape her. Callisto became pregnant and Juno furiously changed her into a bear. The story is told by Ovid in the 2nde book of the Metamorphoses.

" Practice, also means, routine, habit contracted by assiduous excercise. Mos, experientia. A Merchant knows Arithmetic only by practice, without knowing the reason for what he does. The continuous practice of a trade, renders a Craftsman skillful." (Trévoux). Painting from a model, which involves paying someone to pose in front of you, is contrasted with practice painting, which is faster and more economical, where the painter paints from memory, and repeats by routine faces and poses he has already painted.

Boucher had already treated Jupiter and Callisto in 1744 (Moscow version, #003911), in 1759 (Kansas City version, #002890), and he would take up the theme again in 1769 (London version, #003910). The speckled cheetah (not tiger) skin is found in the 1759, 1765 and 1769 versions. It is also found, for example, in the Renaud et Armide of 1734 (#001206). And it will be found again in Angélique et Médor.

Angelica is the main heroine of Ariosto's Orlando furioso (Roland furious) (1532). Pursued by Roland's love, Angelica comes across the wounded soldier Médor, whom she nurses back to health and falls madly in love with, while they are staying with shepherds, far from the battlefield. Although queen of Cathay (China), Angélique marries Médor, a simple soldier, and takes him to her kingdom. Their blissful stay with the shepherds leaves its mark, however: their monogram, and even their verses engraved all over the place by Médor will be found by Roland, who goes mad (furious) with grief.

Lulli's Roland, Quinault's adaptation of Ariosto's epic, dates from 1685. If you look closely at Boucher's canvas, Médor is not extending his right hand to inscribe the lovers' monogram on the trunk (the scene commonly painted when Angélique et Médor is painted) but to pluck a rose.

Nicaise is a verse tale by La Fontaine (1671). The silly Nicaise is an apprentice draper; his master's daughter gives him a gallant rendezvous at night in the forest.

"Nicaise after a few moments

La va trouver: et le bon sire

Seeing the place starts to say:

How damp it is here!

Hay, your habit will be spoiled.

It's beautiful: it would be a shame.

Suffer without further delay

I'll fetch a rug.

- My God, let's leave the clothes on!

Says the stung beauty.

I'll say I've fallen."

But Nicaise is stubborn, and keeps his belle waiting for some time. When he returns, it's too late:

What's the point," he says to the lady,

"That you didn't wait for me?

That you didn't wait for me?

On this well-spread carpet

You'd be a woman in no time.

Let's go back without consulting:

Come and stop being a virgin;

Since I can, without spoiling anything

I can show you how zealous I am.

Perhaps a memory of the descent into the Underworld, in Book VI of the Eneid: Umbrarum hic locus est, somini noctisque soporae, This is the abode of shadows, of sleep and of the drowsy night.

In fact, this was probably the intended destination for this painting.

" Tripière, s. f. Woman who sells tripe. Iliaria propola omasaria. A basin, a tub of tripière. A woman coarse of body & too fat is also called a Tripière. Perpinguis." (Trévoux)

" Compare with this reflection on Vanloo's Grâces: "They don't know that it's an uncovered woman and not a naked woman who is indecent. An indecent woman is one who would have a cornette on her head, her stockings on her legs and her mules on her feet. This reminds me of the way Mme Hocquet had made the prudish Venus the most dishonest creature possible. One day she imagined that the goddess was hiding herself badly with her lower hand, and here she had a plaster cloth placed between this hand and the corresponding part of the statue, which immediately looked like a woman wiping herself." (DPV XIV 33-34; Ver, IV, 298) About Lagrenée's Suzanne, in 1767, Diderot wrote: "This is the difference between a woman we see and a woman who shows herself." (DPV XVI 127)

The stage name of Catherine-Antoinette Foulquier, of the Italian comedians. She "debuted on December 20, 1753 with the role of Angélique in La Mère confidente by Marivaux. A rather mediocre actress but a good dancer and a very pretty woman, she married M. de Rivière, chargé d'affaires at the Saxon court, and had a daughter [...]. Catinon Foulquier [...] left the theater in 1769" (É. Campardon, Les Comédiens du roi de la troupe italienne pendant les deux derniers siècles, I, 49 and 105). Catin, or Cathin was the diminutive of Catherine. "But it is only among the people, it is low. [...] Catin even sometimes has a bad meaning, & is almost taken for a runner." (Trévoux)

Diderot omits the comma here: it's the jumble effect...

La Jardinière endormie is the counterpart to L'Offrande à la villageoise. The two paintings, of the same format, are in fact presented in the booklet under the same number 10.

At the beginning of the Salon of 1765, Diderot reported on a visit organized by Chardin, the Salon's upholsterer, for the critics: "Messieurs, Messieurs, de la douceur. Between all the paintings that are here look for the worst, and know that two thousand unfortunates have broken the brush between their teeth in despair of ever doing so badly." (DPV XIV 22) Chardin's appeal for indulgence was aimed at young painters at the start of their careers rather than painters at the height of their fame: competition was fierce for the Prix de Rome, and then the approval of the Académie, which allowed for exhibition.

They played together, for example Mlle Catinon as Jeannot opposite Justine Favart as Jeannette, in Les Ensorcelés, a parody performed by the Italians at the Hôtel de Bourgogne in 1757 and revived in 1760.

Fluxion: inflammation. In fact, the left eye of the sleeping gardener is larger than the right eye...

L'Oiseau by Gaspard Netscher was then kept at the Galerie du Palais-Royal. See Romanet's engraving (#021499) after a version of the painting preserved at Apsley House in London.

As part of the querelle des Anciens et des Modernes, supporters of the Anciens had criticized Fontenelle for the preciousness of the shepherds in his pastorales. Fontenelle defended himself (Poésies pastorales, avec un Traité sur la nature de l'églogue, et une Digression sur les anciens et les modernes, Paris, Brunet, 1708). Abbé Desfontaines, publishing a new translation of Virgil in 1743, had revived the polemic with a Discourse on pastoral poetry, illustrated by Cochin (#017909): a pretty shepherd in fine clothes interrupts the concert of a real shepherdess surrounded by real shepherds...

Overlaid on the querelle des Anciens et des Modernes was the querelle des Bouffons, which pitted the proponents of French music, which was more codified and text-based, against those of Italian music, which placed more emphasis on lyricism and the melody of song. The quarrel had erupted during the performance of Pergolesi's Servante maîtresse in Paris in 1752. It serves as the backdrop for Rameau's Neveu. While philosophers tended to side with the Italians, Diderot always remained measured between the two camps: hence Grimm's intervention here...

The painting is lost, but its probable counterpart, Le Courrier secret, by Boucher in 1767 (#016556), is known.

Les Salons de Diderot (édition)

Archive mise à jour depuis 2023

Les Salons de Diderot (édition)

Salon de 1763

Préambule du Salon de 1763

Louis-Michel Vanloo (Salon de 1763)

Deshays (Salon de 1763)

Greuze (Salon de 1763)

Sculptures et gravures (Falconet, Salon de 1763)

Salon de 1765

La Chaste Suzanne (Carle Vanloo, Salon de 1765)

Boucher (Salon de 1765)

La Justice de Trajan (Hallé, Salon de 1765)

Chardin (Salon de 1765)

La jeune fille qui pleure son oiseau mort (Greuze, Salon de 1765)

La Descente de Guillaume le Conquérant en Angleterre (Lépicié, Salon de 1765)

L'antre de Platon (Fragonard, Salon de 1765)

Sculpture (Salon de 1765)