Gustave Doré was born in Strasbourg in 1832; his father, an engineer at the Ponts et Chaussées, wanted to make him a polytechnician, while his mother would always support his artistic vocation, and this would become even more important after the death of her husband in 1849.

From an early age Gustave drew and painted, giving free rein to his overflowing imagination. After 1843, he made a name for himself and published his first drawings in Bourg-en-Bresse, where his father had been transferred. During a trip to Paris in 1847, he had the opportunity to meet Charles Philipon, publisher of the Journal pour rire, who accepted his drawings, and launched his career in the satirical press, while supervising his studies at the Lycée Charlemagne.

He began his career as an illustrator in 1852, first illustrating the works of Rabelais. Publications and successes quickly multiplied, and he was at the height of his fame when he published La Sainte Bible and John Milton's Paradise Lost in 1866.

The Holy Bible.

Doré and the Mame project

There were few illustrated editions of the Bible. During the French Revolution between 1789 and the year XII, Clément-Pierre Marillier and Nicolas-André Monsiau had succeeded in getting one published1, based on a translation by Lemaistre de Sacy, a translation that was also used for subsequent editions. In 1839 Achille Deveria illustrated a Bible with Houdaille2, followed in 1858 by Célestin Nanteuil with Martinon3, while in 1841 Charles Furne had published a Bible illustrated with 32 engravings after works by great painters such as Raphaël, Girodet, Murillo4...

It was time for images. Journalist Léon Lavedan writes:

"The art of illustration is thoroughly modern, and it goes well with our positive, realistic age. Even better than writing, it is the art of painting the word and speaking to the eyes, and in the hurried time in which we are agitated, a time when [...] we read everything except books, it is convenient that the pencil, summarizing the text and illuminating it with one stroke, instantly tells the eyes, what the mind has no leisure to seek and deepen5. "

Alfred Mame (1811-1893), heir to a dynasty of printers and booksellers, created a truly modern publishing house in Tours at mid-century, with an industrial printing plant on huge premises handling all stages of book production. He continued the family Catholic tradition, "nothing contrary to sound doctrines", with popular books, including, in 1855, the 48-volume "Bibliothèque de la jeunesse chrétienne".

But he also published prestige illustrated volumes, such as Don Quichotte, La Touraine de l'abbé Bourassé...

At this time, Gustave Doré and Alfred Mame embarked on a rather crazy venture together: the former, who dreamed of illustrating the Bible and had been turned down in Paris, struck a deal with the Touraine publisher, who innovated with regard to the text. All illustrated Bibles reproduced the same translation by Lemaistre de Sacy because, unlike Protestant countries, the French Catholic tradition remained cautious about translating the Scriptures. This time, however, Alfred Mame decided to publish a new translation, admittedly based on the Vulgate, but by two unknown canons of Tours, J. J. Bourassé and P. Janvier.

.The book was made, not without difficulty: it comprises 1000 folio pages in two volumes and several hundred original engravings, a fine example of what the house could do. It was also an excellent business deal: the woodcuts, executed for the most part in his workshops, became the property of the Mame family, and were a source of income for a long time to come.

Woodcuts: a good example of what the company could do.

The engraved images

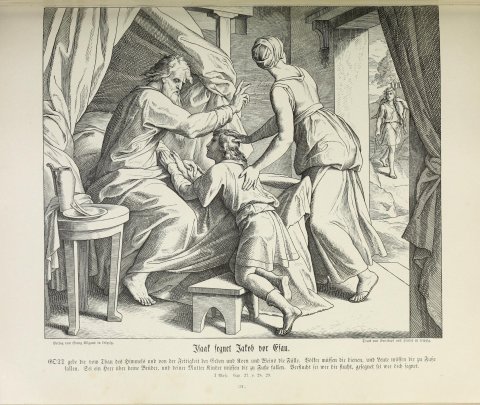

Doré set to work in 1862, and images of the Bible became a fixed idea. He created 274 images and, at the end of 1865, organized an exhibition of his drawings and engravings at the Boulevard des Italiens.

In Germany, there was an illustrated Bible by Schnorr von Carolsfeld, published in 18606, with 240 engravings, but this famous work was a picture Bible, following the sacred text scene by scene. For Doré, it was an illustrated Bible, in which he was free to select and interpret the scenes. The drawings form a visual sequence parallel to the texts, but not synchronized with them. The images follow the order of the books of the Bible, except for the Gospels, where he reconstructs a chronological order, instead of taking the books in the traditional order.

It's an original work, without refraining from paying homage to the tradition of the great artists, using the works of Raphael, for Jacob's dream, of Delacroix, for the struggle of Jacob and the angel... he also draws inspiration from the drawings of other less famous illustrators, but most of it is personal, with little local color, as he has never been to the Near East. This didn't stop him from taking an interest in archaeological discoveries, going to the Louvre to look at Babylonian and Egyptian collections. But he didn't hesitate to create images, sometimes of pure invention, some of which were never published.

Doré's engravings took advantage of the revolution in "standing wood" engraving, invented in England by Thomas Bewick in the 1770s. The design is carved into a wooden board at right angles to the grain of the wood, hence the name "bois debout" (standing wood) as opposed to "bois de fil" (grain wood). The design is still in relief7, but this carving in a harder wood produces images with finer details, close to those produced on metal-engraved plates, with the advantage of allowing the illustrations to be integrated into the text, as the matrix has the same thickness as the typographic characters8. But for the Holy Bible the illustrations are always full-page.

This engraving implies close collaboration between the draftsman and the engravers. Doré took a close interest in the technique, and it was the illustration of L'Enfer of Dante in 1861, which inaugurated subsequent productions. Doré drew directly on the wood, leaving the engraver to interpret the grisaille. Héliodore Pisan wrote in 1886: "As for the engraving, he didn't have to worry about it, he left me free, but I didn't make any changes to his drawings9." Faced with an influx of commissions, he also used "tint etching", with wash and gouache replacing drawing. "Tint etching gave birth to large plates recognizable by their nocturnal tone and chiaroscuro effects, faithful to Doré's fantastic universe, to the point of making us forget the text they illustrate", writes Alix Paré10. The engravers who worked on images from the Bible are very numerous: in addition to Pisan and Paré, there are François Pannemaker, Gabriel Blaise, Charles-Louis Michelez, Laplante... and many others.

Editions of the Holy Bible

A first edition of the Holy Bible was produced for December 1, 1865, to take advantage of Christmas sales. It is, according to Louis Enault, "the subject of all artistic and literary conversations in Paris, and will be found in a few days on all aristocratic tables". With a print run of 3,200 copies and 228 hors-texte engravings, it sold out very quickly. But Doré found it imperfect, and for the second edition of 1866, he deleted 13 subjects, added 15, and retouched or redid 22 engravings: this made a total of 312 compositions created.

These form a collection housed at Strasbourg's University Library, and were photographed by Gabriel Blaste and Ch. Louis Michelet. These photographs were published in 3 volumes in 1868: this date, subsequent to the 1866 edition, should not lead us to believe that the images postdate it. On the contrary, they allow us to see all the drawings Doré had at his disposal. Some of them, such as "Dieu sépare les éléments" (God separates the elements), will never be engraved in any edition of the Bible. It should be noted that these photographs executed from the drawings give an inverted image compared to that of the printed engravings.

The second edition, that of 1866, is the one we know best. Right from the first page, the text is well referenced: La Sainte Bible, traduction nouvelle selon la Vulgate, par J. J. Bourassé et P. Janvier, chanoines de l'église métropolitaine de Tours, approuvée par Mgr l'archevêque de Tours, dessins de Gustave Doré, ornementation par H. Giacomelli. The editor adds that it is remarkable for its accuracy and fidelity, and that the notes drawn from the Holy Fathers and the best commentators contain nothing that is not in conformity with the holy doctrine of faith and morals.

This is well framed, at the risk of sounding a little too traditional. But, as André Lefèvre wrote in L'Illustration in December 1865:

"Besides, it was only a question of providing a text for M. Gustave Doré's drawings, and it would have been in bad taste to claim and regret here the discoveries of modern exegesis."

The editorial context was, moreover, highly tense, as La Vie de Jésus published by Ernest Renan, experienced 12 editions between 1863 and 1864, fabulous success and enormous controversy, with the author's dismissal from the Collège de France11, and this during the preparation of Doré's Bible.

The1866 version, printed in 3,200 copies and sold for 200 F, would be definitive, and its success led Mame to reissue the work in 1874 and again in 1882.

The engravings are found in English and American editions, then in the many editions published in European capitals, in German, Russian, even Hebrew. Dan Malan estimates that there are 700 editions of works containing engravings by Doré12.

In France many engravings would find their way into popular publications, such as the Histoire de la Sainte Bible published in 1892 by Canon Cruchet13, up to La Sainte Bible racontée aux enfants by Canon Pinault in 191114.

Gustave Doré and religion

This Bible, soon to be called just Doré's Bible, questions his religious ideas. They are not well known, as they are rather rarely expressed by the author, except to his friend, Canon Frederick Harford, who reports his words:

I am a Catholic, I was baptized in the Catholic Church [...] but if you want to know my true religion, here it is. It's contained in the thirteenth chapter of St. Paul to the Corinthians, which thematizes the virtues of love ("If I lack love, I am nothing"), the incompleteness of earthly life and the expectation of knowledge ("We presently see a dark image in a mirror")15.

Elsewhere, in a letter addressed to the canon, the artist signs: "G. Doré, militant Christian16".

What is certain is his will and determination:

"When he talked about illustrating the Bible, everyone raised an eyebrow... The Bible after the droll tales! But he immediately warned me: it's a fixed idea... it'll take a long time! I want to make it my work17."

The work does not include an imprimatur18, which is rather surprising, and so it was a posteriori that the archbishop of Tours, Joseph-Hippolyte Guibert , wrote to Alfred Mame:

"I therefore had to wait for the first printing to examine the engravings which are the capital part of your publication. After examination I, like everyone else, can only express my admiration for M. Doré's talent, so high, so fertile so flexible, and I declare that in the illustration, religious propriety is perfectly observed19."

In his approval of January 18, 1866, published as an exergue in the 1874 edition, he clarifies for readers :

"The numerous engravings which form a capital part of the new publication, have been executed by a most renowned artist, who has combined the brilliance of his great talent with a perfect sense of religious propriety."

Right from the start, Mame and Cassel et Cie of London joined forces to publish the work simultaneously: relations were established directly with Gustave Doré. The Bible published in London caused a profound sensation. Cassel displayed several of the most important plates in its shop window: the one depicting God separating the light, in Ancient of Days, on the model of Raphael, caused a stir among the public and had to be withdrawn20. Doré, who was so touchy and irritable, submitted to this religious prudery without comment: other plates were engraved with the divine representation removed for English and German editions.

Doré made the acquaintance in Paris of several English publishers who opened a Doré Gallery in 1867-69, where drawings, pictorial works and statues were exhibited until 1892, before circulating in North America. With the success of this Gallery, Doré's reputation as a preacher painter was established. This is how Blanche Roosevelt21, his Anglo-Saxon biographer, refers to him, for whom the power of catechetical conviction and the visual rhetoric of his religious works is certain.

In France, critics don't care much about religion, but many find Doré on a par with the great poems of humanity. Thus Paul de Saint-Victor:

"His verve took on the wings of enthusiasm, his imagination rose to the height of the superhuman poems he had to translate22."

Zola often judges the artist's productions to be of great strength, but finds them too romantic, closer to Delacroix than to contemporary artists.

"The shows follow one another, they are all light or all shadow [...]. I can only call it a dream, because the engraving doesn't live our life, it's too white or too black, it seems to be the drawing of a theater set, taken when the enchantment ends in the radiant glories of apotheosis23."

And while he retains the originality of Old Testament images, those of the New seem more banal to him.

"I like this second part of the work less; the painter had to fight against the banality of subjects treated by more than ten generations of painters and draughtsmen, and he seems to have taken pleasure, by I don't know what feeling to attenuate his originality24?"

This opinion is shared by many critics.

Bibliography

Philippe Kaenel, dir., Gustave Doré. L'imaginaire au pouvoir, catalog of the Musée d'Orsay exhibition, Paris, Flammarion, 2014

Alix Paré and Valérie Sueur-Hermel, Fantastique Gustave Doré, Paris, Éditions du Chêne, 2021

Blanche Roosevelt, La Vie et les œuvres de Gustave Doré d'après les souvenirs de sa famille, de ses amis et de l'auteur, translated from English by M. Du Seigneux (actually Mme Van de Velde), Paris, Librairie illustrée, 1887

Sarah Schaefer, Gustave Doré and the Modern Biblical Imagination, New York, Oxford University Press, 2021

Notes

La Sainte Bible, contenant l'Ancien et le Nouveau Testament, traduite en françois sur la Vulgate, par M. Le Maistre de Saci. Nouvelle édition, ornée de 300 figures, gravées d'après les dessins de Marillier et Monsiau. A Paris, chez Defer de Maisonneuve. De l'Imprimerie de Didot jeune, 1789-1791; from volume VI onwards, Paris, chez Gay, libraire - chez Ponce, graveur - chez Belin, imprimeur libraire, An VIII-An XI (1800-1804), 12 volumes. The edition appeared simultaneously in two formats, in-4° (deluxe) and in-8° (economy). Several editions of Lemaistre de Sacy's translation had been published in the 18th century, but without illustrations.

La Sainte Bible illustrée par Devéria. Histoire de l'Ancien et du Nouveau Testament... by J. Derome. Preceded by an introduction by M. l'abbé Deguerry... Augmenté d'un voyage à la terre d'Israël, Paris, Houdaille, 1839, 2 parts in one in-8° volume. The plates are missing from the Bnf copy.

La Sainte Bible traduite par Lemaistre de Sacy, illustrée par Célestin Nanteuil, Paris, Martinon, G. de Gonet, 1858, in-4°.

La Sainte Bible traduite par Lemaistre de Sacy, Paris, Furne, 1841, 4 vols. large in-8°.

Léon Lavedan, "Bibliographie. La Bible illustrée par Gustave Doré", Le Correspondant, n°66, December 1865, p. 1040.

Jules Schnorr de Carolsfeld, Die Bible in Bildern. 240 Darstellungen, erfunden und auf Holz Gezeichnet (with 240 drawn and woodcut illustrations), Leipzig, Georg Wigand, 1852-1860, 30 vols. collected in 2.

As opposed to copperplate engraving, for which the drawing on the plate is intaglio.

For copperplate engraving, a special press had to be used: a page containing both text and engraving therefore had to go through the press twice.

Autograph letter signed by Héliodore Joseph Pisan, November 29, 1886, Paris, Bibliothèque de l'Institut national d'histoire de l'art, cote NUM 0290 (14).

Alix Paré, Fantastique Gustave Doré, Éditions du Chêne, 2021, p. 31.

Appointed to the Collège de France in 1862, Renan was suspended after his inaugural lesson for referring to Jesus as "an incomparable man". He was dismissed and revoked in June 1864. He was reinstated in November 1870 by the provisional government, and held the chair for 22 years. See Jean Balcou, "Ernest Renan ou l'honneur du professeur", Études renaniennes, 1996, n°102, p. 19-31.

Dan Malan, G. Doré, Adrift on Dreams of Splendor, St. Louis, Malan Classical Enterprises, 1995, p. 139.

Histoire de la sainte Bible, Ancien et Nouveau Testament, par M. l'abbé Cruchet, Tours, A. Mame et fils, 1892, in-Fol. The book was regularly republished until 1926.

Pierre Pinault, La Sainte Bible racontée aux enfants, Tours, Maison Alfred Mame et fils, 1911. Gathers L'Ancien Testament raconté aux enfants and La Vie de N.-S. Jésus-Christ racontée aux enfants.

Blanche Roosevelt, La Vie et les œuvres de Gustave Doré, Paris, Librairie illustrée, 1887, p. 254.

Quoted in Philippe Kaenel, dir., Gustave Doré, l'imagination au pouvoir, Flammarion, 2014.

Georges D'Heilly, "Promenades artistiques dans les ateliers de Paris", Les Beaux Arts, revue nouvelle, t. IV, 1er janvier-15juin 1862, 1862 (actually 1863), p. 133.

The imprimatur is the permission to print given by ecclesiastical authority. It is always mentioned in the book.

Letter published in the Revue du Monde catholique, t. 14, p 560, December 10, 1865.

Philippe Kaenel, dir., Gustave Doré, l'imagination au pouvoir, catalog of the Musée d'Orsay exhibition, 2014, p. 17.

Blanche Roosevelt, La Vie et les œuvres de Gustave Doré d'après les souvenirs de sa famille, de ses amis et de l'auteur, translated from English by Du Seigneux, Librairie illustrée, 1887.

Paul de Saint-Victor, "Les livres illustrés : la Bible de Gustave Doré", L'Artiste, journal de la littérature et des beaux-arts, dir. Arsène Houssaye, n° de janvier 1866, p. 10.

Émile Zola, article of December 14, 1865 for Le Salut public, journal de Lyon, politique, commercial et littéraire, in Écrits sur l'art, ed. Jean Pierre Leduc-Adine, Gallimard, Tel, 1991, p. 55.

Émile Zola, Écrits sur l'art, op. cit., p. 60.

Illustrer la Bible

Dossier dirigé par Serge Ceruti depuis 2023