The taste revolution

" As many men, as many judgments1 " : it goes without saying for us today that taste is a matter of subjectivity. But taste has not always been identified with the sovereign expression of an intimate judgment. On the contrary, classical culture was based on an objectivity of taste, defining a common framework of representation, and implying a recognizable familiarity with forms, figures and composition. In 1757, Landois defined taste as follows in the Encyclopédie :

Goût, se dit en Peinture, du caractere particulier qui regne dans un tableau par rapport au choix des objets qui sont représentés & à la façon dont ils y sont rendus.

[...] Il y a goût de nation, & goût particulier : goût de nation, est celui qui régne dans une nation, qui fait qu'on reconnoît qu'un tableau est de telle école il y a autant de goûts de nation que d'écoles. Voy. School. Peculiar taste is that which each painter makes for himself, by which one recognizes that such and such a painting is by such and such a painter, although there always reigns the taste of his nation. We also say goût de dessein, goût de composition, goût de coloris or de couleur, &c. (R) (Goût, VII 770b)

At no point is there any question of the spectator facing the marble or canvas, of the effect the work produces, the pleasure he derives from it, the judgment by which he evaluates it. Taste is not a matter of reception; it defines and orders production regimes it does not affirm a singularity, but a community it is a genre of painting it is the distinctive mark of a nation, of a school. Nor does it have anything to do with the materiality of art : taste is ideal ; it's a beautiful nature, that is, an abstract model from which to execute representation.

At the end of the century, things would be very different. The aim of the Kantian triple critique is precisely to reverse the relationship between subject and object, and, for the Critique de la faculté de juger (1790), to make the subject experiencing aesthetic feeling in the face of the work of art the center and principle on which is founded, no longer the objective reality of taste, but the judgment of taste :

" To distinguish whether something is beautiful or not, we do not relate the representation to the object through the understanding with a view to knowledge, but we relate it through the imagination (perhaps linked to the understanding) to the subject and the latter's feeling of pleasure or displeasure. The judgment of taste is therefore not a logical judgment, but an aesthetic one, i.e. one whose determining principle can be nothing other than subjective. " (I, 1, 12)

We start from what we have in front of us, the representation, the work, to go not to the object it represents, but to ourselves who experience pleasure or displeasure. Taste is no longer a question of the relationship between the representation and the object; it is no longer a problem of imitation, or even a matter of understanding, of implementing the rules of composition and execution of the representation. Taste operates with and in the imagination, receiving the sensitive, aesthetic effects that the work produces on us.

This reversal founds aesthetics as a specific field of philosophy : etymologically, aesthetics is, globally, the science of sensation, i.e. of sensible effects here it becomes the science of art and the analysis of its effects it gives itself as its object, its field, the effect we receive from the work of art.

The second half of the eighteenth century is the scene of this fundamental double reversal in attention to the work of art : discourse slips from the point of view of its /// The second shift is the emergence of pleasure at the heart of aesthetic discourse. An essential corollary of this second shift is the emergence of pleasure at the heart of aesthetic discourse.

.Between model and judgment

Diderot's main writings on art take place between these two milestones, the article Goût in the Encyclopédie on the one hand, the Critique de la faculté de juger on the other. It would be tempting, then, to follow its evolution as a participant in that great reversal of the Enlightenment at the end of which is born what we today call aesthetics : at the time of the Encyclopédie, in the 1950s, Diderot became fascinated by the techniques of art, and privileged artisan art over artist art. This is the first phase. With the Salons, in 1759, a second phase begins: on the strength of his experience at the theater in 1757 and 1758, Diderot takes into account the position of the spectator and introduces taste in the modern sense of the term. But this new position is not exclusive of the old one, which persists in the original form that made the Salons famous: Diderot continues to consider as his priority not the visible realization, but the intellectual content, the idea, the story that the work tells. From this idea, in conjunction with the scene the artist has represented, he aims to recreate, to produce the work afresh. Diderot goes very far in this direction, going so far as to restore a story, an idea, to paintings that, by their very genre (landscape, still life), are devoid of them. He's not eccentric in this respect, but very much part of his era, for whom history was the paradigm, and the stage the principalmedium of representation. The very term description, which then as now does not aim at the detached, picturesque authenticity of detail, but is part of the encyclopedic logic of a definition of the object, implies this competition of pen and brush from the same idea.

However, from the Salon de 1767 onwards, the most accomplished of the Salons, doubt sets in is it indeed the ideal that takes precedence ? Isn't technique3 what's essential ? Wouldn't there be a " sublime of technique4 " ? From then on, it's impossible to go back to the idea to recreate the work in parallel with the one presented to us technique is judged by its effects it can only be evaluated by the pleasure we subjectively derive from it. Competing with painters by producing works through the pen alongside them, describing better than they would have painted, ceases to be the issue, because production is no longer the issue. Diderot becomes a broker, and begins the third phase of his relationship with art, that of the commercialization of taste: Diderot sold his taste to Catherine II, not only by helping her build the core of her classical collection through the massive purchase of paintings at the great private sales of the early 1770s (Gaignat, 1769 ; Thiers, 1771 ; Choiseul, 1772), but also by acquiring contemporary works (Vien, Demachy, Casanove, 1769). Finally, starting in 1776, he wrote the Pensées détachées sur la peinture, whose first chapter, as in Hagedorn's Réflexions sur la peinture, which he was reading at the time, is entitled " Du goût5 " the second, " De la critique ". This starting point centered on the reception of the work of art can be contrasted with that of the Essais sur la peinture which in 1766 served as the conclusion to the Salon de 1765 : the first two chapters, " Mes pensées bizarres sur le dessin " and " Mes petites idées sur la couleur ", started from the two pillars of artistic teaching and therefore production, /// all the classic academic debate about the pre-eminence of one or the other.

The metaphysical legacy

Does this mean that, before the emergence of aesthetics as a specific field of philosophy, the work of art was considered only in terms of production, i.e., in classical terms, poetics and composition ? There is, of course, a thousand-year history of our relationship to representation and theorizing about it. When Diderot wondered what it meant to see, a decisive prerequisite for taking into account the viewer's position in relation to the work, he inherited the whole Cartesian optic, and the mechanistic ideology that supported it: it was against this mechanism that he developed his own materialism. When he marvels at the spectacle of nature, he positions himself in relation to an entire theological tradition of vision, which runs from St. Paul to Thomas Aquinas, and to a scholasticism that, even by the eighteenth century, has left deep traces in patterns of thought and reasoning. Finally, when Diderot evokes the idea, the ideal, the ideal model of the work, he refers, explicitly, to Plato's Republic6, to the myth of the cave7 and to the Platonic exclusion of poets from the city8.

Not only does Diderot not adhere unconditionally to these metaphysical traditions, but he tends to overturn the metaphysical idealism he inherits. This is not the way to found an aesthetic, and a fortiori not the way to found a Kantian aesthetic. This is the difficulty, but also the originality and undoubtedly the modernity of Diderot's taste: what we might call his radical a-subjectivity, from which to apprehend the very matter of art.

.An a-subjective taste

When taste ceases to define a style or genre, when it detaches itself from the object, it is taken first as sense, as immediate sensitive apprehension, as corporization of art : to taste art, to be disgusted by it, to abolish and recreate the distance between subject and object ; taste undoes the subject, elides the verb and reduces vision to a monstration : to a " voilà ", to a " c'est ".

Taste then develops and propagates a commerce, a collectivity of taste, from which the positions of the dialogue are distributed. A new defection of the subject : taste introduces the plurality of voices, the sharing of opinions, the interplay of differences.

Taste finally designates the acquisition of an experience, what we acquire a taste for. But acquiring taste does not fix judgment. On the contrary, this experience is that of an exit from oneself into foreign territory, an alienation from the field of art, a reverie that passes through the enjoyment of one's own dissemination.

Taste, finally, designates the acquisition of an experience, that which one acquires a taste for.

" To describe a Salon to my liking and yours, do you know, my friend, what one would need to have ? All kinds of taste, a heart sensitive to all charms, a soul susceptible to an infinity of different enthusiasms, a variety of style that responded to the variety of brushes ; could be grand or voluptuous with Deshays, simple and true with Chardin, delicate with Vien, pathetic with Greuze, produce all possible illusions with Vernet ; and tell me where is this Vertumne9 ? " (Preamble to the Salon de 1763, Ver IV 237 ; DPV XIII 341)

Facing the work, Diderot experiences a triple dissemination : dissemination of objects, which threatens description with illegibility dissemination of voices and sharing of judgments, which dialogizes speech and breaks down discourse ; /// dissemination of points of view, fragmenting and alienating the gaze. This triple dissemination lies at the root of the radical a-subjectivity of Diderotian taste.

The paths of experience

For all that, despite an insistent reference to the objective exteriority of a public taste, a national taste, Diderot forges his taste through singular experience. He does not come to art from an artistic culture, and before the Salons he had seen virtually nothing. He confesses as much himself in the preamble to the Salon de 1765 :

" It was the task you proposed to me that fixed my eyes on the canvas and made me turn around the marble. I gave the impression time to arrive and enter. I opened my soul to the effects and let them penetrate me. I collected the sentence of the old man and the thought of the child, the judgment of the man of letters, the word of the man of the world and the words of the people and if I happen to wound the artist, it is often with the weapon he himself has sharpened. I questioned him, and I understood what it was that finesse of drawing and truth of nature ; I conceived the magic of light and shadows ; I knew color ; I acquired the feeling of flesh. " (Ver IV 291 ; DPV XIV 21-2)

This experience is one of dispossession : to let the impression in, to open one's soul to the effects, to let oneself be penetrated, is to accept a certain dissolution of oneself, a transport of oneself into the plurality of voices and objects. The first experience, then, is that of a kind of self-suppression : it was long prepared before the Encyclopédie.

Blind visions

In the first writings of the late 1740s, allegory occupies a prominent place, not only, according to a practice then common, in the frontispieces of his works, but also in their very conception.

Allegory of the Mask

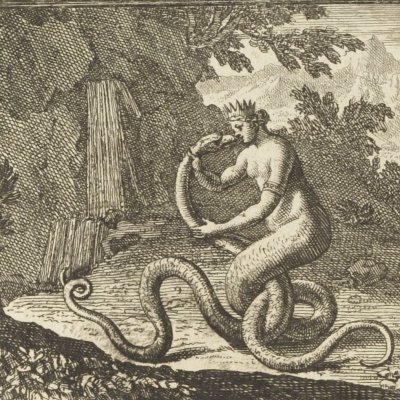

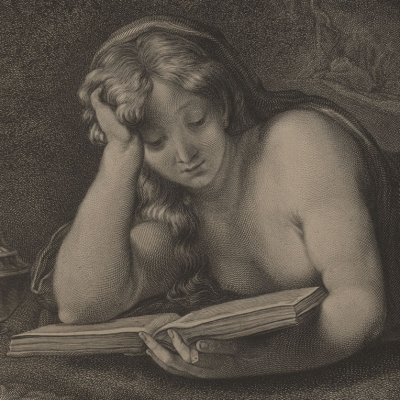

Among these early allegorical images is the mask of superstition, a prelude to the figure, central to Diderot, of the blind man. The allegorical frontispiece of Pensées philosophiques (ill. 1), in 1746, depicts Natural Religion, a kind of long-haired flying Venus, Lucretius's Aeneadum genetrix , snatching her closed-eyed mask from the hands of Superstition, an old woman with a broken scepter whose dress poorly conceals the dragon's tail10. Superstition's crown is down, and the sphynge with its enigmas (the incomprehensible discourses of supposedly revealed Religion) is crushed beneath it : vision in ænigmate, is thus identified a contrario with Christian faith, while the naked body with outstretched arms of the ancient goddess defines the exercise of philosophical Reason both as epiphanic experience of vision and as seduction of the gaze. The allegory of superstition unmasked will fizzle out we find her in revolutionary engravings, trampled underfoot alongside despotism (ill. 2). But her mask crosses paths with another, that of Thalie, the muse of the Theater11 : raising and lowering the mask is the founding gesture of classical theatrical performance.

Interposition of the curtain

Les Bijoux indiscrets, composed in 1747 following the Pensées philosophiques, offers a kind of narrative representation of this mechanics of representation : in the kingdom of Monomotapa, somewhere in Africa, the young sultan Mangogul is bored stiff in the company of his beautiful favorite, the virtuous Mirzoza. He decides to consult his tutelary genius Cucufa, who offers him a magical ring to entertain him: when turned on the finger, it makes the wearer invisible, and makes the jewel speak to the woman towards whom it is pointed12. The novel then unfolds as a series of thirty-one ring essays : the original two-volume edition of Bijoux is illustrated not only with an allegorical frontispiece, but with a liminal vignette and 6 prints. The last of these illustrates the twenty-ninth essay in the ring, the story of Zuleïman and Zaïde (ill.3). This story of perfect love between Zaïde and her lover Zuleïman, in which the jewel's speech contradicts neither Zaïde's words nor her fiery letters, despairs Mangogul, who sees it as competition to his love for Mirzoza. So the sultan visits the young woman a second time, and this is the scene the engraver has illustrated.

In the foreground, on a shepherdess adorned with a Venus shell, below a painted Pastorale (a woman lies at the foot of a tree, another sketches a dance step in front of her), Zuleïman develops the arguments of her amorous speech, her hands balancing the weight of it. Attentive, perhaps amused, slightly in the background, Zaïde has tenderly extended her right arm over his shoulder. A curtain shields their intimacy from the background, where Mangogul stands.

The scene echoes a print from the 1740 edition of Crébillon's Tanzaï et Néadarné (ill. 4), a libertine oriental tale to which Les Bijoux indiscrets makes explicit and repeated reference. In this print, which is also anonymous, the genius Jonquille approaches the beautiful Néadarné, who, deprived of her jewel by a spell, has come to offer herself to him in order to recover it. Néadarné plays the coward and, though almost naked and with her legs spread, modestly steps back. The scene is unwitnessed in the novel, but the illustrator adds a fountain to the right, with water gushing from the beak of a swan that seems to be watching the protagonists out of the corner of its eye.

The illustrator of Bijoux indiscrets returns to set design forLa Déclaration d'amour by Jean-François de Troy (ill. 5), with its coral damask-stretched bergère and gold-leafed shell, its curtain on the left limply preserving a simulacrum of intimacy, the large cushion on which the young woman leans on the right, and the pastoral painted panel, above, which seems to redouble, with even more ardor, the passionate momentum of the foreground. The engraving simplifies the scene cluttered by de Troy, making the hat disappear on the sofa (the hat deposited on the sofa is not to be seen). /// indicates the erotic scene), the dog clinging to the dress, the mantelpiece topped with a vase, and opens up a second shot to the left for voyeuristic break-in:

" Mangogul, overwhelmed with sadness, fell back in an armchair, and put his hand over his eyes. He feared to see things that are well imagined, and which were not... " (II, 19, Ver II 191, DPV III 148)

The figure seated by the window is Mangogul : it's dressed in the same long tunic that Mangogul invokes Cucufa in the print illustrating chapter IV of the first volume. The engraver has not reproduced Diderot's gesture of veiling his eyes. However, the layout of the premises makes it materially impossible for Mangogul to see, and the curtain held in place by a kiss materializes this impossibility13.

Mangogul doesn't use the ring. He lets the lovers talk, for a discourse that leads to nothing : the sincerity of the amorous discourse forbids sexual enjoyment. The engraver conveys this lesson of the scene through Zaïde's light irony and Mangogul's bored melancholy, observed as if in laughter by a comedy mask molded in stucco at the top of the wall above him. The mask, the curtain and the magic ring express the same mechanics of representation: something is temporarily lifted, revealing the object from a distance. Let the lifting become permanent, and the object vanishes.

Iconology of the headband

Religione (Ripa, 1603) - Chevalier d'Arpin

In La Promenade du sceptique14, Diderot imagines three alleys representing three different philosophical attitudes: the allée des épines, for religious fanatics; the allée des fleurs, for libertines; and, in between, the allée des marronniers, frequented by skeptics. The inhabitants of thorn alley are blindfolded15. The fanatic believer's blindfold caricaturizes Paul's parable in the Epistle to the Corinthians, " We see now through a mirror and in a blur, but then we shall see face to face " (I Cor 13, 12)16. The blindfold, or veil, allegorically represents the imperfect vision of pre-Revelation man, for whom face-to-face vision is still forbidden. This is why the allegory of Religion, in Ripa's Iconology, is depicted with her face covered by a thin veil (ill. 6). The veil of Religion is opposed by the blindfold of Error, represented by a blindfolded traveler groping with a stick17 (ill. 7). But this opposition is only apparent : the journey of Error is the pilgrimage of life, at the end of which, if we don't go astray, we can hope for Christian bliss. It's also the journey of the pilgrims on the thorn path, in the same posture as Christ when he appeared to his disciples at Emmaus18, a path that Ripa identifies with that of Reason19. We thus see how, in the most orthodox iconology, blindness is turned into illumination, and the blindfold becomes the necessary prerequisite for vision.

A parodic veil of Faith, it is compared to a " faceted glass20 ", which fragments and multiplies the object observed or projected through it. Not only is it a question of seeing through the veil and the blindfold, but, from the avenue of chestnut trees to that of thorns, of spying through the bushes, of making incursions21, of slipping " stealthily through a defile, a wood, a fog, or some other stratagem likely to favor the secrecy of their march22 ", conversing through a cabinet of greenery, " separated by a sharp hedge, thick enough to prevent them from joining, but not from hearing each other23 ". Finally, in the flower aisle, the headband continues to exert its empire : " Their headband bothers them a lot ; [...] so they only leer at intervals and as if by stealth24. " The alley itself is compartmentalized into " cabinets destined for various uses " where, while a lover walks away, " a rival, who only waited for his absence, crossed a bower that hid him ", where women " leered at me through a light gauze that covered their faces "25.

In contrast to this concealed, concupiscent, backward gaze, regulated by the interposition of a veil, a bower, a screen, is the mystical vision of the blind of the thorn alley, awaiting the magnificent rewards of Faith :

But what do these magnificent rewards consist of ?... In what ? seeing the prince ; seeing him again ; seeing him over and over again and still being as amazed as if seeing him for the first time, and how is this ?... How ? By means of a lantern that will be placed on the pineal gland, or on the corpus callosum, I'm not sure which, and which will show us everything so clearly that...

We'll be able to see it again and again, and always be as amazed as if we'd seen it for the first time...? À la bonne heure (Allée des marronniers, §27, Ver I 112, DPV II 127).

Diderot mocks Descartes' Dioptrique , where the philosopher, describing the " images which are formed on the back of the eye ", imagined their transport " to a certain little gland, which lies about the middle of these concavities " of the brain. This gland, identified with the pineal26, excited the verve of Descartes' opponents. To make it operational, Diderot grafted onto it, for the benefit of the Christian rewarded by the lights of Faith, the lantern of Empedocles27, a deaf lantern, i.e. a closed lantern, whose candle is uncovered only through a narrow opening, so that the wearer can see without being seen : Christian superstition only enlightens the fanatic who claims to be enlightened by it. But beyond the anti-Christian persiflage, it's the optical device that's important from the illumination provided by the /// clara visio dei, we've moved on to a break-in system, which individualizes and subjectifies vision, defining it as a break-in, the voyeur thief surprising by means of his lantern a commonly stolen spectacle. This device will occupy a central place in the Salons28, where it founds the spectator's gaze on the work, and in Diderotian fiction, whose scenes it orders.

The blind man with two sticks

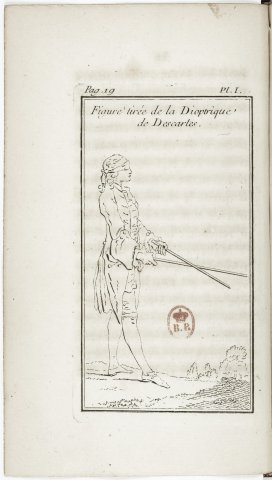

The origin of the gaze is thus, for Diderot, an impeded vision, a vision of the blind. The frontispiece of the Lettre sur les aveugles, published in June 1749, refers to the parable of the blind man that opens Descartes' Dioptrique (" De la lumière "). Initially, it's any of us " walking at night without a torch, through difficult places ". But in the chapter " De la vision ", when the illustration comes, " l'aveugle, dont nous avons déjà tant parlé " has become a true blind man29 (ill. 8 and 9). In any case, Descartes is not blindfolded. As for the two sticks that meet at point E, which the blind man looks at with the tips of his hands, these are extrapolated by the designer, Descartes speaking only of " straight lines that one can imagine being drawn from the end of each of these parts " : the man " turns his hand A towards E, or C also towards E ". These straight lines thus represent the two natural abscissa and ordinate axes by which the viewing subject instinctively defines, as he moves, the optical plane in which to measure the geometrical position of the object being viewed.

.

The blind man with two sticks is thus in a way a post-Cartesian aberration, which Diderot exacerbates : " Madame, open Descartes's Dioptrique, and you will see there the phenomena of sight related to those of touch, and optical boards full of figures of men busy seeing with sticks. " (Ver I 142, DPV IV 21) The recurring figure in the Dioptrique is in fact that of the racket player, and the blind man with sticks appears only once ; the draughtsman has taken care to stop the sticks at point E, which by their means must be located in space, and to extend them as virtual straight lines by dotted lines30. The two intersecting sticks on the frontispiece of the Lettre sur les aveugles thus make no sense, and the elegant young man in a Louis XV suit who replaces the old blind man weighted down with a dog on a leash echoes the allegories of Flower Alley far more than Cartesian demonstrations (ill. 10).

Blinded by the blindfold for the /// The young man withdraws into himself, like the characters Carmontelle would plant standing pensively in a vague landscape31 in 1765, Carmontelle drew M. de Tourempré raising levels by means of two small mirrors attached to the end of a cane he extends in front of him (ill. 11), or the Montmort brothers absorbed in front of an optical instrument32. Each time, absorption signifies a withdrawal, towards a reverie, an attention below representation, and at the same time an exhibition : from the reverie, it's the dreamer who must be seen, his figure designates his interiority.

From then on, the blindfold and crossed sticks take on meaning, no longer as an optical parabola to demonstrate, as Descartes had done, the tactile geometrality of vision, but as an observational device that is at the same time a representational device. Putting on and taking off the blindfold, crossing and uncrossing the sticks, is a virtual experience of blindness, and of the uncertainty of the stick as a supplement to the eye, an experience carried out in the manner of a game, a parlour play, by a temporary, worldly, clumsy blind man. To understand vision, we'll have to play blind, exhibiting ourselves on the stage of this virtual game in the posture of withdrawal, clumsiness, and the impossibility of seeing.

The experience of looking

The entire beginning of the Lettre sur les aveugles is in fact devoted to setting up this device : Réaumur refused to allow Diderot to attend a cataract operation33 that restored sight to a born-blind woman ; " in a word, he only wanted to drop the veil before inconsequential eyes " (Ver I 139, DPV IV 17). The word " voile " echoes the blindfolds in La Promenade du sceptique, also referred to as veils, and will play an essential role in the theoretical thinking of the Essais sur la peinture, which came to close the Salon de 1765 in 1766. The Essais take as their starting point a blind woman : " See this woman who lost her eyes in her youth " (Ver IV 467, DPV XIV 343). Nature, called in as a virtual spectator for a stolen scene, will be presented with just one part of this woman's body, any part except her face. The same goes for a hunchback: "Cover this figure, show nature only the feet...". From there, we move on to the great antique models : " May I be permitted to transport the veil of my hunchback on the Venus de Medici, and let only the tip of her foot be seen "34. Nature, then, restores the blind man and the hunchback, but not Venus, for the best statuary has not been able to render at every point of the body the exact proportions and deformations that each of its parts has induced on the others.

The imaginary scenario is the same every time, and harks back to the childhood experience of things disappearing. Diderot, anticipating the Freudian scenario of the fort-da35, only indirectly conveys the anguish, through the joy of the reappearance of objects :

" Wouldn't it be more natural to suppose that children then imagine that what they cease to see has ceased to exist ; all the more so as their joy seems mingled with admiration, when the objects they have lost sight of, come to reappear. Nannies help them to acquire the notion of the duration of absent beings, by exercising them in a little game which consists in covering themselves and suddenly showing their faces. " (ibid.)

The interposition and lifting of the veil bring out the visible, a visible that is no longer merely optical (a geometry of touch), but phenomenological, or scopic a thrust, a drive manifests itself from the visible, which makes one see and steal, which exhibits and subtracts, which dramatizes and absorbs. This visible, which is learned through play, is irreducible to the blind vision that Christian mysticism and classical optics had first bequeathed to Diderot.

The spectacle of nature

This irreducibility is manifested most violently in the Lettre sur les aveugles by the blind man's revolt against the spectacle of nature : " We come out of life, as out of an enchanting spectacle ; the blind man comes out of it as out of a dungeon " (Ver I 145 ; DPV IV 24). As a result, the theological argument of the wonders of nature, as proof of God's existence, falls for the blind man, whose allegory Diderot, this time radically flipping the allegory of La Promenade du sceptique, makes the spokesman for atheism36 : " it's that this great reasoning we draw from the wonders of nature, is quite weak for the blind " (Ver I 148 ; DPV IV 28). As the blind Saunderson, Cambridge's genial and virtuous professor of mathematics, is about to die, Parson Holmes is dispatched to his bedside

" The minister began by objecting to the wonders of nature : "Eh ! Sir," said the blind philosopher, "leave here all this beautiful spectacle that was never made for me ! I have been condemned to spend my life in darkness, and you quote prodigies to me which I do not hear, and which prove only for you and for those who see as you do. If you want me to believe in God, you must make me touch him." " (Ver I 166 ; DPV IV 48)

And Saunderson dismisses Newton, Leibniz and Clarke back to back37 : " I see nothing ; yet I admit in all an admirable order ". For the blind, Beauty can only reside in the arrangement of parts, in the composition of the whole Saunderson therefore substitutes the order of nature for its spectacle. It is characteristic that the two articles Diderot will devote to art in the Encyclopédie, Beau and Composition, start precisely from what, of art, is, by his own admission, comprehensible by the blind, i.e. inessential : the system of relationships (the word recurs more than a hundred times in the Beau article), the distribution of parts.

The Architect's taste

The Beau article, published in Volume II of the Encyclopédie in 1752, compiles the gray literature of the time, itself highly exegetical. In it, Diderot doesn't develop his aesthetic theory he describes a field, and thereby reveals to us what he's reading : neither the Abbé Du Bos, whose name is never mentioned (nor in the Salons for that matter), nor Félibien, nor the lectures at the Académie royale de peinture, but first, via Father André38, Plato and Saint Augustine, then the Leibnizian Christian Wolff39, which Formey rightly remarks he has only read superficially40, Crousaz41, finally Hutcheson42 whom he follows closely.

The basis of the Beau article is chapter 32 of the first book of Augustine's De vera religione. Augustine asks what drives the construction worker (artifex) to /// look for symmetry in what it builds:

" he'll tell me that this is how it's done, that this is what's beautiful, that this is what pleases the people watching, and he won't hazard anything more. He settles in on himself, his eyes turned towards the ground, and he doesn't understand where this is coming from. But it's the man who has eyes inside (virum intrinsecus oculatum), and who sees into the invisible (invisibiliter videntem) that I will not cease to admonish [...]. And I will first ask him if there is beauty because it pleases or if it pleases because it is beautiful43. "

Agustin contrasts the down-to-earth vision of the worker with the inner eye of man, the spiritual clairvoyance that sees the invisible. The search for beauty is the search for grace : aesthetics is the true religion and the vision of the beautiful - the vision of the mystically blind.

In Father André, who paraphrases Augustine, the mystic's inner eye disappears, and the pleasing colonizes discourse :

" But why does this symmetry seem necessary to you ? For the reason that it pleases. But who are you to set yourself up as the arbiter of what should or should not please men ? And how do you know that symmetry pleases us? I'm sure of it, because things arranged this way have decency, rightness, grace in a word, because it's beautiful. All very well. But tell me : is it beautiful, because it pleases, or does it please because it is beautiful44 ? "

There's no longer any question here of the inner eye, or of seeing the invisible. It is in the very disposition of things that lies the origin of their beauty ; but beauty consists in this disposition. The origin, the cause of this principle of symmetry and order is then proclaimed as unity, " this unity, which directs you in the construction of your design ", " this unity which you regard in your Art as an inviolable law ", " a certain original, sovereign, eternal & perfect unity ".

At this point in the demonstration, Father André returns to Augustine and reintroduces, as the principle of this unity, " the art of the Creator[,] that supreme art, which furnishes him with all the models of the wonders of nature " : here we find Pastor Holmes's speech to Saunderson in the Letter on the Blind. In the article Beau au contraire, which then follows Wolff, the Beautiful is deduced " from the things that please us ", according to an " internal sense " (Hutcheson), a " faculty of feeling and thinking " which establishes " relations of propriety and disconvenience " (Ver IV 97, DPV VI 154). The logical circle of origin45 somehow short-circuits the development of a metaphysical thought of beauty.

Everything indicates that Diderot wrote this article in 1748 before the Lettre sur les sourds46. The theory of relationships developed in the article Beau, which contains no reference to any literary or artistic work whatsoever, remains dependent on the conceptual framework of the Letter on the Blind : the Beautiful is thought of there as an intellectual construct of the imagination, which does not differentiate the spectacle of nature from the productions of art. An event will precipitate this fundamental epistemological mutation and the intimate split on which it rests.

The stage and the painting

On the morning of July 24, 1749, the police raided Diderot's apartment on rue de l'Estrapade, with orders to seize the manuscripts there, and had him taken to Vincennes prison, on /// lettre de cachet. The initiative was taken by the Comte d'Argenson, who had been director of the bookshop since 1737, and as such in charge of censorship. D'Argenson acted in concert with the Lieutenant General of Police, Nicolas René Berryer, a friend of La Pompadour, who led the interrogation on July 31. Diderot denies being the author of the Pensées philosophiques, the Bijoux indiscrets and the Lettre sur les aveugles, but is betrayed the very next day by his publisher, the bookseller Durand. On August 13, terrified at the prospect of indefinite detention, which the lettre de cachet allowed, Diderot recanted and pledged on his honor not to write anything in future without submitting it to Berryer's judgment47. The conditions of his detention were softened and, thanks in particular to the repeated intervention of the editors of the Encyclopédie, who demanded that he complete the greatest editorial undertaking of the century, he was released on November 9. In the early days of his imprisonment, Diderot wrote twice to his father, who replied on September 3, rather harshly :

" And remember the reminder that your poor mother, in the remonstrances she gave you in a loud voice, told you several times that you were a blind48. "

Diderot's blind man, both blind mystic and militant atheist, thus referred to Diderot himself, under the combined and repressed gaze of his mother and father.

The order of words

The Lettre sur les sourds et muets à l'usage de ceux qui entendent, published in February 1751, indicates by its title the paradigm shift : deprived of speech since Vincennes, having become something of a deaf-mute, Diderot seeks another means of expression, and this means will not be diverted : it's about rediscovering the original expression, the energy of gesture, the immediate and global effect of the image.

The subject of the Lettre is apparently essentially technical and erudite : it's about the question of inversions, introduced by 17th-century grammarians49 and recently raised again by Abbé Batteux50 ; this question will be taken up again, with abundant borrowings from the Lettre sur les sourds, in the article Inversion in the Encyclopédie, signed by Beauzée51 (VIII, 852-6).

The starting point is the experimental device of the Lettre sur les aveugles : an eye is confronted with an object for the first time. What happens when we see things for the first time ? The nature of things is given to us in a certain order, called " natural order ", but language will express them in another order, " scientific or institutional order "52. The discordance of phenomenological apprehension and discursive representation is manifested by inversion.

Under cover of a grammarian's discussion that seems somewhat Byzantine, Diderot here makes a fundamental epistemological shift : by identifying the order of language with an order of institution, he introduces an order of thought, anterior to language. He then defines the primary nature of thought as an experience of sight : " the eye would first be struck by the figure ", this is the beginning of thought, the prerequisite of representation53.

To the natural, material, immediate vision received by the eye, Diderot superimposes a view of the mind, metaphorical, mediated by language. Inversion becomes the experience of this superposition, for which Diderot borrows the figure of translation: to go from the instituted order to the natural order of thought, he asks a deaf mute to translate a speech "from French into gestures". But this translation is impossible: Diderot surreptitiously reverses the meaning of the translation, pointing out that there is an expressive intensity to gesture that words will never translate.

." ... one would manage to substitute gestures more or less for their equivalent in words ; I say more or less, because there are sublime gestures that all oratorical eloquence will never render. Such is the case of Macbeth in Shakespeare's tragedy. The sleepwalking Macbeth strides silently across the stage, eyes closed, imitating the action of someone washing their hands, as if theirs were still stained with the blood of the king whose throat they had slit more than twenty years ago. I know of nothing so pathetic in speech as the silence and movement of this woman's hands. What an image of remorse ? " (Ver IV 17 ; DPV IV 143)

The sublime gesture is mute ; it still defines an allegorical figure, the image of remorse, in continuity with the allegories of La Promenade du sceptique and Bijoux indiscrets. But inexorably, from this point on, Diderot moves away from the discursive54 and grammatical perspective on which the question of inversions rested: the theatrical stage becomes the fundamental form of expression and representation.

What remains of the stage when we take away the word ? The sublime pathos of a gesture without eloquence, the silence of a mechanical movement, in other words, that which, in the actor's performance, remains irreducible to any system of signs, bordering on the infigurable. It's still, and already no longer, an allegory.

The sublime gesture

Diderot probably hasn't read Macbeth : he's mistaken in evoking the murder of Duncan, the rightful king, by Lady Macbeth, when it was Macbeth himself who slit his throat. Shakespeare was then almost an unknown in France55, even though Voltaire praised him in 1734 in the nineteenth of his Lettres philosophiques. There is no attested performance of Macbeth in France before 178456. But in the 1740s, Diderot earns his living as an English translator. He took an interest in Alexander Pope, whose translation by Silhouette of the Essay on Man57 he annotated. Yet Pope was Shakespeare's great publisher in the early eighteenth century : his 1725 preface was constantly republished in later editions, and notably in the 1744 edition illustrated by Hayman58. The illustration from Macbeth depicts precisely scene 1 of Act V, where sleepwalking Macbeth enters rubbing his hands together, as his physician and his lady-in-waiting look on worriedly59 (ill. 12). We can assume that Diderot just went through the play and fantasizes the scene from the print inserted at the beginning of the text.

The hypothesis is reinforced by another convergence between these frontispiece engravings given in editions of dramatic texts and the scenic examples that Diderot pretends to invoke spontaneously. In Corneille's Héraclius he cites the place

" where the tyrant turns successively to the two princes, calling them by his son's name, and the two princes remain cold and motionless.

Martian! To this word nobody wants to answer.

Here is what paper can never render here is where gesture triumphs over speech ! " (Ver IV 18 ; DPV IV 143)

Diderot doesn't have the text in front of him : he quotes a false verse from memory. On the other hand, this face-off between Phocas and the two princes is the subject of François Chauveau's engraving for the 1664 edition60 (ill. 13) ; it is still him we see in the forgeries of 1714 and 174061 and Gravelot chose him for the illustration in 176462. The scene evoked is therefore only fictitiously theatrical : Héraclius was performed in Paris until 1723 and from 1766 ; Diderot had not seen it in the theater when he wrote the Lettre sur les sourds.

The convergence is the same when Diderot quotes Rodogune63 :

" In the sublime scene that ends the tragedy of Rodogune, the most theatrical moment is without question, the one where Antiochus raises the cup to his lips, and Timagene enters the stage shouting : ah ! Lord ? what a host of ideas and feelings this gesture and this word do not simultaneously evoke ! " (Ver IV 18 ; DPV IV 144)

This is the scene illustrated by Chauveau (ill. 14) in the same 1664 volume of Pierre Corneille's Théâtre, reprinted in the forgeries of 1714 and 1740, illustrated afresh by Gravelot in 1764 : like Héraclius, Rodogune features two interchangeable heir princes bound by an unbreakable friendship. The engraving shows Antiochus, one of the princes, in the center, who has just taken the cup from the hands of his mother Cleopatra, Queen of Syria. Antiochus on the right, supported by her follower Laonice, staggers, while on the left Rodogune, princess of the Parthians, whom Antiochus is to marry, but whom Cleopatra pursues with her hatred, reaches out to remove the cup. Behind them, on the left, the helmeted Orontes, ambassador of the occupying Parthians, and the old Timagenes, tutor to the two princes; on the right, the women of Cleopatra's retinue; in the center, the throne of Syria, which is at stake throughout the play. In this last scene of Rodogune, the engraving represents the final moment when Cleopatra, who has poisoned herself, collapses, having failed to regain power from her sons and rival. Diderot does evoke this scene, but at its beginning, when Timagène enters, with his interjection " Ah ! Lord ! ", stops Antiochus, who was about to /// drinks the poison and announces the death of his brother Seleucus.

These slight shifts give us valuable insights into Diderot's way of working : the engraving fixes for him the sublime scene, which he plays out inwardly. He doesn't describe the image he has seen he recreates the scene. Each time, the sublime gesture is captured before the illustrator's representation: Diderot recreates the preparatory movement, Phocas' hesitation between Heraclius and Martian before their governess Léontine intervenes, Timagène's irruption before Cleopatra, who is about to poison herself with the cup intended for her son. He explains this in the article Composition in the Encyclopédie : when Hercules must choose between the path of vice and that of virtue, it's not the decision made, but the hesitation before the decision that needs to be painted ; when Calchas sacrifices Iphigenia, it's not Clytemnestra's fainting at the sight of her dead daughter, but, before her death, her desperate gesture to stop Calchas' raised knife that needs to be painted64. Classical representation would have celebrated or deplored a completed action the Diderotian imagination anticipates and suspends time before the decision. The energy of representation lies in its inchoativeness the sublime gesture comes just before the image. Not only do the engravings reveal its origins, but they also enable us to grasp Diderot's emerging taste, from which he would lay the foundations of the theory of the pregnant instant.

.The mother, the stage : a constitutive withdrawal

Let's add the personal resonance of these scenes. While his mother, of whom he never speaks65, has just died, Diderot, who married without his family's knowledge, evokes Rodogune where Cleopatra, the queen mother, dies trying to prevent her son's marriage ; as he emerges from Vincennes prison, from which he has vainly implored his father to intercede for him, and clashes head-on with his brother Didier, a bigoted canon, he evokes Héraclius, where a father is summoned to choose between his son and the latter's milk brother, whom he meditates to assassinate in order to retain his usurped throne while his father has just reminded him, in a biting letter, of his late mother's admonitions, he evokes a sleepwalking Lady Macbeth trying to wash the blood from her hands, an image of remorse : each of these images can be read as a counter-accusation, each of these gestures - as the restrained expression of a revolt against one's own.

The mute image carries the meaning of what cannot be said, both because at Vincennes Diderot promised the highest authorities of the State to keep silent, and because, on a private level, his mother's death reduces his rancor to silence. The meaning of the image, then, is first and foremost that of a suppression of speech, dramatized by a curious experiment :

" I used to go to shows a lot, and I knew most of our good plays by heart. On days when I proposed an examination of movement and gesture, I went to the third boxes : for the further I was from the actors, the better placed I was. As soon as the canvas was up, and the moment came when all the other spectators were ready to listen ; me, I put my fingers in my ears, [...] and stubbornly kept my ears plugged, as long as the actor's action and acting seemed to me to agree with the speech I remembered. " (Ver IV 21 ; DPV IV 148-9)

The first stage of the experiment is the observation, on stage, of a purely gestural expression, which Diderot relates to his memory of the corresponding speech to experience the discordance : the scene slides into nonsense. This scissionist experience is the basis of what he will practice in his Salons. But the game, the contamination of the incomprehensible, doesn't stop there: Diderot observes and is observed. He makes a spectacle of himself, plugging his ears and enjoying the spectacle he produces. The device invented here to order the Diderotian spectator's relationship to the stage and the painting organizes a back-and-forth movement from subject to object, a loop through which the scopic dimension of the gaze manifests itself from the parterre the spectator withdraws " aux troisièmes loges ", as far away from the stage as possible he withdraws from its visibility, in a way reiterating the posture of the blind man.

.This subtraction was prepared from the very first pages of the Lettre sur les sourds : Diderot, addressing his bookseller, suggests a curious manipulation :

" You'll find in the plate of Lucrece's last book, from Avercamp's fine edition, the figure that suits me it's only necessary to move aside a child who half hides it, suppose a wound below the breast, and have the line taken from it. " (Ver IV 12 ; DPV IV 133)

Sigebert Havercamp had published in Leiden in 1725 a Latin edition of Lucretius' De rerum natura adorned with engravings by Frans Van Mieris. That of Book VI (ill. 15) illustrates the Plague of Athens and suggests to Diderot the ancient painting of Aristides of Thebes described by Pliny : " An infant who, during the capture of a city, crawls to the breast of his mother dying of a wound we see that the mother notices this and fears that, his milk having dried up, he will suck her blood. " The mother engraved by Van Mieris has no visible wound and does not look at her child66. Diderot then engages in a mental manipulation of the engraving, which first proves that the basis of his thinking is not Pliny's text, nor Du Bos who glosses it67, but the image found while leafing through the engravings of a luxurious illustrated edition, an image from which her imagination anticipates the scene it produces, giving us a glimpse of the mother before the child has begun to crawl towards her, while her wound is still visible. This anticipation takes the form of a subtraction : to remove the child from a mother who turns away from him to slide towards death is to figure the gesture of abandonment, the dead mother as mother turned away.

Landscape with a man killed by a snake / The Effects of Terror - Poussin

The body of the dead mother, from which the child is removed, is designated here as a figure for the Lettre sur les sourds (ill. 16). The withdrawal of the child corresponds, on a theoretical level, to the withdrawal of the spectator, his voluntary deafness, and on a traumatic level to the abandonment experienced by Diderot during his imprisonment at Vincennes. The dead mother, marked by this withdrawal68, forms the body of the scene.

In the Salon of 1767, she reappears twice at the evocation of a painting by Poussin69. The Paysage with the Man with the Snake, also known as Les Effets de la terreur (ill. 17), is cited by Fénelon and Félibien as a model of gradation in the expression of passions70. But it's a woman that Diderot sees enveloped, embraced by an enormous snake. Fénelon, who accurately describes the painting, explicitly evokes a dead man; the explanation beneath Étienne Baudet's engraving does the same71. Diderot changes the image, perhaps influenced by an iconographic subject from Ovid's Metamorphoses, Cadmus and Hermione changed into a snake, where Cadmus is usually depicted already a snake embracing Hermione still a woman (ill. 18).

.

The image somehow finds its motto in the Letter on the Deaf when discussing word order Serpentem fuge72 : fuis le serpent, is the cry of the traveler who rushes off, in Poussin's composition, after seeing the body embraced by the snake.

Speculation and the practice of art

The writing of the Lettre sur les sourds is contemporary with the first articles of the Encyclopédie, whose first seven volumes appeared, up to the letter G, at the rate of one per year, from 1751 to 1757. The Art article was undoubtedly written in the wake of the Prospectus, published in November 1750 at the same time as the Lettre sur les sourds. What Diderot, in accordance with the classical understanding of the word, defines as the field of art corresponds only incidentally to the Beaux Arts, and encompasses much more generally " the industry of man applied to the productions of nature " (Ver I 265-6, DPV V 495). Diderot's essential aim was to rehabilitate the mechanical arts, i.e. the crafts of artisans and the activities of manufactures, vis-à-vis the liberal arts, i.e. the theoretical and abstract disciplines taught at university.

.Here the fundamental tendencies and frameworks of the Salons discourse on art are decided. In place of the medieval distinction and hierarchy of the liberal and mechanical arts, Diderot substitutes the unique and universal opposition of art and science, an opposition that runs through all objects without distinction or hierarchy:

.

" If the object performs, the collection & technical arrangement of the rules according to which it performs, are called Art. If the object is contemplated only from different sides, the collection & technical arrangement of the observations relative to that object are called Science : thus Metaphysics is a Science, & Morality is an Art. [...] It is evident from what precedes, that every Art has its speculation & its practice73. " (Encyclopédie, Art, I, 713, Ver I 266)

The opposition of speculation and /// The structural polarity from which Diderot thinks of art is the opposition of the practical and the technical; in the Salons, this opposition translates into that of the technical and the ideal. But this opposition is immediately presented as a contradiction : it does not define the complementarity of two logical categories, but the ideological conflict of two conceptions of art, one idealistic, based on the speculation of scholars and philosophers, the other empirical, starting from the practice of trades, the doing of craftsmen, the experience of workshops.

.The praise of Colbert in the Art article makes this hiatus immediately apparent:

" Colbert regarded the industry of the people & the establishment of manufactures, as the surest wealth of a kingdom. In the judgment of those who today have sound ideas of the value of things, he who populated France with engravers, painters, sculptors & artists of all kinds who surprised the English with the machine for making stockings, the velvets to the Genoese, the mirrors to the Venetians, did hardly less for the state, than those who defeated his enemies, & took away their strongholds & in the philosopher's eyes, there is perhaps more real merit in having given birth to the le Bruns, the le Sueurs & the Audrans ; painting & engraving Alexander's battles, & executing in tapestry the victories of our generals, than there is in having won them. " (I, 714, Ver I 267)

Colbert did more for France by promoting the arts than Louis XIV did by winning battles. But above all Diderot distinguishes two aspects of his policy, the institution of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, " which populated France with engravers, painters, sculptors & artists of all kinds ", and industrial espionage, which enabled the development of manufactures. The Académie gave French artists the legitimacy of speculation, and the authority of a universal discourse on art factories imported, recovered foreign technologies. In other words, French creation is speculative it is through the crucible of the Académie that this imported technique is transformed into the export of tapestries designed by Le Brun, or engravings executed by Audran.

.In the same way, the promotion of the mechanical arts, and therefore of craftsmen, against the rhetors, is extended in the Salons by criticism of the hierarchy of genres and the redefinition of the boundaries between history painting and genre painting74. But Diderot never overturns this hierarchy. If Chardin, Greuze, Vernet, Loutherbourg borrow from the manner and subjects of Dutch painting, just as the Manufactures borrowed from Genoa, Venice and the English, it is as magicians, as demiurges, as creators75 that they return their borrowings the very experience of still life is philosophical76. A speculative origin of Art replaces the practical origin of borrowing and gives the work its universal scope.

It is in this epistemological tension between idea and experience, between metaphysics and the matter of art, that Diderot's contributions to the Encyclopédie in the field of art are inscribed. At first glance, they are extremely technical : the article *Copy (Painting), where Diderot first mentions Chardin77, poses the problem of distinguishing between original and copy ; the article *Couleur, dans les Arts, written with Landois, deals with the transition and gradation of colors ; the article Dessein (terme de l'art de Peinture), written with Watelet78, /// outlines a method for learning drawing the article Empreinte, written with de Jaucourt, develops the processes of engraving79.

However, these contributions should not be reduced to a collection of factual descriptions. Diderot positions himself from the point of view of production because there is not yet an aesthetic field from which to systematically consider the reception of the work of art. Production is the specific supplement that the Encyclopédie brings in relation to other dictionaries, " like muscles added to arms, and springs accessory to those of the mind " (Art, Ver I 267) ; but this supplement is also an origin and a theoretical criterion on which to establish a discourse of truth : the copy poses the problem of manner, and of the duplication of the Beautiful, which are the constitutive problems of a discourse of art ; color produces effects and thereby conditions taste ; drawing " signifies in the first place production ", but to define an " art of imitation ", in other words a theory ; imprint carries the same ambiguity, since it is " the engraving, the impression itself; & the thing engraved or expressed ", the technical process of production and the result produced to be judged speculatively.

The only exception to these technical articles is the article *Composition, en Peinture, where the first elements of Diderot's artistic culture appear : he mentions Rubens' Cycle de Marie de Médicis, which he had seen in the Cabinet du Luxembourg open to the public since 1750 ; Le Choix d'Hercule, probably by Paolo de'Matteis (ill. 19) commented on by Shaftesbury80, whose Essai on Merit and Virtue he translated in 1745 ; the sacrifice of Iphigenia and the sacrifice of Abraham, generally taken as subjects for composition without precise reference ; finally L'École d'Athènes by Raphaël81 (ill. 20). But these unoriginal references, which can be found in the literature of the time, do not attest to the personal appropriation of works looked at at length. In the article *Encyclopédie, Diderot tells us that, in his capacity as director, he unwillingly acted as a stopgap, writing an article for which he had not found a taker:

Encyclopédie.

" We had hoped from one of our amateurs most praised, the article Composition en Peinture, (M. Watelet had not yet offered us his help). We received from the amateur, two lines of definition, without accuracy, without style, & without ideas, with the humiliating admission, that he knew no more ; & I was obliged to make the article Composition en Peinture, I who am neither amateur nor painter82. "

In luce e tenebris...

The movement of thought, which imports the material of art from the outside in order, in this experience, to assign it a theoretical origin likely to prepare its reception /// aesthetics, will gradually find its visual translation. The basis for this is Diderot's insistence on the dispositions of things83. The Pensées sur l'interprétation de la nature, published in December 1753, opens with a quotation from Lucretius, " Quæ sunt in luce tuemur e tenebris ", what is in the light, we see from the darkness. Lucretius describes the phenomenon of vision, explaining why it is from light to dark and not vice versa :

" From the darkness we see what is in the light

for this reason that, when the veil of black air approaches,

penetrates the eyes and takes possession of them while they are open,

it is immediately followed by the glow of luminous air,

which, as it were, purges them and disperses the dark shadows

of the first air. of the first air : for in all its parts the second is

more mobile, finer and more powerful.

And as soon as it has filled the accesses of our eyes with its light

and cleared those previously encumbered by the black air,

immediately follow the simulacra of things

that are placed in the light, and they assail us so that we see them84. "

Seeing from the darkness refers both to the blind man's vision with the sticks85 and to the theatrical performance where Diderot, from the darkness of his dressing room, plugged his ears to watch the actor's sublime gesture stand out in the stage light. Of course, Diderot misappropriates the quotation: the scene referred to in the Interpretation of Nature is the very spectacle of nature, which we observe as best we can from the darkness of our ignorance and stammering physics. Nonetheless, a certain order of representation and, to see it, an observational device are put in place, a theatrical, scenic device whose effectiveness is intended to be transgeneric, or in other words encyclopedic. Nature, art, mechanical art in workshops and the fine arts produced by poets, statuaries and painters, are brought back to this device, which tends to constitute itself as a kind of universal hermeneutic and epistemological medium.

.The object of art (artist art and technician art) is seen from the darkness of the dark room and unfolds, is ordered on the stage of a theater : intimacy of darkness ; publicity of light. Between the two, an invisible interface, a veil in Lucretius, it's caliginis aer ater, a veil of black air that obstructs the ocular channels of vision, interposing itself between the eye and the light, only to be expelled by the light of the image. The veil is the very veil of nature itself:

" If a few authors were allowed to be obscure, were I to be accused of aping myself here, I'd dare say it's to the metaphysicians proper alone. The great abstractions carry only a dark glow. The act of generalization tends to strip concepts of all that is sensible about them. As this act progresses, corporeal spectres fade away; notions gradually withdraw from the imagination into the understanding; and ideas become purely intellectual. Then the speculative philosopher resembles the man who looks down from the top of those mountains whose summits are lost in the clouds the objects of the plain have disappeared before him all that remains is the spectacle of his thoughts, and the awareness of the height to which he has risen, and where it may not be given to all to follow him and breathe.

XLI. Hasn't nature enough of its veil, without doubling it again with that of mystery ? isn't that enough of the difficulties of art ? " (Ver I 582, /// DPV IX 69)

Diderot here explicitly refers to himself as that metaphysician who must be forgiven his obscurity because he is engaged in the Lucretian process of vision. The " dark glow " (aer ater) of abstraction constitutes the beginning of theorization. Then comes the movement of generalizing thought from phenomena hunts " bodily spectra " (nigras discutit umbras) : then comes the purely intellectual, or speculative, vision, which is a face-to-face encounter with the spectacle of nature86 completely internalized, identified by the philosopher with " the spectacle of his thoughts ".

Paradoxically, while Diderot lays the first foundations of his biological materialism in this 1754 text, the object of this experience still remains, in its expression at least, linked to the ancient mysticism of vision, to that wonder of nature which, unveiling itself, reveals Grace. What emerges is the form of the painting, which radically breaks with this powerful logic of wonder87.

What is a table ?

Diderot first thinks of the painting from its metaphysical practice, as a movement of thought conceptualizing ideas in the inner theater of the mind. The painting is therefore not a form, but an experience; it does not define an aesthetic, but a practice. And it is from a practice, from Dorval's improvised theater in her Salon with her family, that the Entretiens sur le Fils naturel give the first explicit formulation of this in 1757 :

" I would much rather have tableaux on the stage, where there are so few, and where they would produce such a pleasant and sure effect, than these coups de théâtre which are brought about in such a forced manner, and which are founded on so many singular suppositions, that, for one of these combinations of events which is happy and natural, there are a thousand which must displease a man of taste. " (1er entretien, Ver IV 1136 ; DPV X 91)

To the poetic process of the coup de théâtre88, Dorval opposes the natural evidence of the tableau, which he initially refuses to define, precisely because the tableau is not a poetic category of fiction, but an empirical fact of life. The coup de théâtre is brought in from outside, it forces the space of the stage, it introduces the artifice of " singular suppositions " of a constructed plot, it manifests par excellence the poetic spring of fiction. On the contrary, the painting imposes the immanent logic of its internal layout and the continuous flow of its development. " Moi ", Dorval's interlocutor, thus concludes :

" An unforeseen incident that occurs in action, and suddenly changes the state of the characters, is a coup de théâtre. A disposition of these characters on the stage, so natural and true, that, faithfully rendered by a painter, it would please me on canvas, is a tableau. " (ibid.)

The painting is a layout. It is defined neither by its frame or border, nor by the fixity of a chosen, arrested moment89 : it's about letting people be, seeing them live in their homes, then transposing their living room as delicately, as faithfully as possible onto the stage, then the stage onto the canvas.

The tableau is the horizon of the representation's movement, the medium into which it could project itself. The tableaux vivants that Diderot imagines at the beginning of each act of Père de familletranspose to the theater the thought experiment he has been indulging in since the Lettre sur les aveugles, an experiment that, /// from optics to physics, from metaphysics to the mechanical arts, will have traversed every field, every exercise of the mind. The epistle to the Princesse de Nassau-Saarbruck, which opens the 1758 edition of the Père de famille, insists on this projective mobility that prepares the writing of the Salons.

The taste for useful things

From the end of the first paragraph, Diderot portrays herself as a mother meditating on the education of her children91, an education that will preserve their fantasy of making happy and thereby give them a taste for art :

" So if images of happiness cover the walls of their living rooms, they'll enjoy them. If they have gardens, they will walk in them. Wherever they go, they will bring serenity. (Ver IV 1195 ; DPV X 183-4)

Diderot starts from the old aristocratic conception, which assigns to painting an ornamentation function in the princely dwelling : rococo painting deploys its hedonistic decorations on palace walls ; but to enjoy them, you have to be able to relate these " images of happiness " to a personal experience of pleasure : you have to get out. From paintings on the walls, we then move on to statues in the gardens, and then to adventure in the wide world92.

The young princes will not just enjoy existing works ; they will become patrons and participate in the production of art.

" Will their taste call artists around them and fill many studios with them ? The crude song of the man who toils from sunrise to sunset, to obtain from them a morsel of bread, will teach them that happiness can also be to him who saws marble and cuts stone ; that power does not give peace of soul and that work does not take it away. " (Continued from previous)

This participation is educational it will bring them into contact with working life, it will introduce them, outside the gilded cages of their palaces, to the world of simple people. This is the very approach Diderot advocated for the implementation of the Encyclopédie93 it is also, in the amorous version of the Père de famille, not without mawkishness, that of Saint-Albin, the son of M. d'Orbesson, gone to live under the name of Sergi with the beautiful but poor Sophie94.

To access art, then, you have to start by getting out of it, leaving the palaces and gardens, going to meet the " artists ", cavorting with the men of art, the workers, taking part in the productive life of the workshops. This movement, this thought experiment (Diderot imagines herself Princess and mother, and from there projects a totally virtual life for the children of her protector95) is radically antagonistic to the aesthetic approach that will found, with Kant, the judgment of taste on the ideal detachment of the subject from the work of art96.

" I have a taste for useful things, and if I pass it on to them, facades, public squares, will move them less than a dunghill on which they will see naked children playing, while a peasant woman sitting on the threshold of her thatched cottage will hold a younger one tied to her teat, and swarthy men will occupy themselves in a hundred various ways with the common sustenance.

They will be less delightfully moved by the sight of a colonnade than if, passing through a hamlet, they see the ears of corn emerging from the half-open walls. /// of a farm."(ibid.)

The taste for useful things, which this ideal education of princes should instill, manifests itself first and foremost in a profound distrust of ceremonial architecture, identified with the noble and detached art of princes. At the opposite end of the spectrum from a pompous urban setting, Diderot conjures up for the princes a thatched cottage, a hamlet worn down by agricultural work.

Strictly speaking, it's not the frame of the genre scene that replaces that of the history painting the frame falls : " My son, if you want to know the truth, get out, I'll tell him ". It's life that makes the picture, and in life the activity of the humble. The poetics of the tableau, theorized in the Discourse on dramatic poetry that follows the Père de famille in the first edition of the play in 1758, is part of this movement and logic, constituting neither an aesthetic (which would presuppose the exercise of a distanced judgment in the face of the tableau), nor a form (the cutting out, the circumscription of the tableau-form ; the text of the didascalia).

Projection, virtualization

The tableau is born of the impression that life produces on the imagination. It's an ideal construction, i.e. a virtual one, and a construction in motion, to walk around in. How to judge a drama, Diderot asks, at the beginning of De la poésie dramatique ?

" One way of deciding which has often succeeded me, and to which I return whenever habit or novelty makes my judgment uncertain, for both produce this effect ; is to seize objects by thought, to transport them from nature to canvas, and to examine them at that distance, where they are neither too near, nor too far from me.

Let's apply this method here. Let's take two comedies, one in the serious genre, the other in the gay let's form, scene by scene, two galleries of paintings ; and let's see which one we'll wander through the longest and most willingly, where we'll experience the strongest and most pleasant sensations ; and where we'll be in the greatest hurry to return. " (Ver IV 1282 ; DPV X 337)

Strictly speaking, there are no paintings anywhere but in the imagination. Still, these paintings form a gallery in which to wander, not an object or objects in front of which to stand. The gallery is an evasive space towards which to step out (" If you want to know the truth, step out ") ; it is also a space in motion, where the paintings are not fixed : what counts is the transport of nature on canvas the gallery is made and unmade on sight, scene by scene97, in the movement of the walk. This is why the faire-tableau, rather than the forme-tableau, orders the poetics that Diderot intends to implement, reversing the posture of the critic into that of the creator.

We've seen him invest speech, the very body of the Princess of Nassau-Saarbruck and, from that body, colonize the young prince's gaze when faced with genre scenes of a hamlet. In the same way here, he turns the passive, receptive position of the amateur summoned to evaluate, to judge, into a creative enterprise, and transforms the critical face-to-face encounter with the object into a virtual investment in an imaginary picture gallery, i.e. in a device that envelops him98 and of which he is the animator.

The painting is not real : the real, nature, is what is to be transported into the painting, what to form a gallery of paintings with. The painting is in formation; it is caught up in the sensitive movement of transport. In these lines, and even before Diderot had begun writing the Salons, we can see what was to condition his position as " poet " among artists, and the stakes of the mastery he intended to acquire in the field of art : /// not the critical overhang of the amateur, for which he would never cease to reiterate his contempt, but a victorious competition on the very terrain of creation, painting against painting, idea against idea, description against execution.

.Culture des Salons

Diderot didn't have the concrete experience of assiduous attendance at works of art until 1759, when his friend Grimm entrusted him, for the Correspondance littéraire, the task of writing reviews of the exhibitions that the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture organized every two years in the Salon carré du Louvre99 (ill. 21 and 22). La Correspondance littéraire is a handwritten journal, which therefore escapes censorship for printing. Its subscription is costly, its prestigious subscribers few and far between100. Diderot thus obtained a guarantee of almost absolute confidentiality, which gave him a wide margin of freedom in his appreciation of works and artists his Salons were to become, in the course of the 60s, the most famous section of the Correspondance littéraire and, one thing leading to another, the most voluminous too.

The Correspondance littéraire did not have the exclusivity of such a column, provided by the major printed journals of the time : Le Mercure de France and L'Année littéraire are the most regular, to which are added L'Observateur littéraire, then the Mémoires secrets, initially handwritten, and a whole series of more or less anonymous pamphlets. One of the aims of these descriptions is to encourage readers to buy the works exhibited by artists approved by the Académie101. Did Diderot and Grimm immediately think of the profit to be made from such sales, for which they would be the intermediaries? It was in fact later, in the 1970s, once his reputation had been established, that Diderot would act as broker for Catherine II in some very important private sales.

.Politics of taste ?

It was first of all something else that fascinated Diderot : the Salons were an extraordinary public event, revolutionary in its conception, and one whose success continued to grow. This is evidenced by the fact that the exhibition booklet, necessary to decipher the works displayed like a jigsaw puzzle on the high walls of the Salon carré, was piled up on long tables without labels. Only the numbers of the paintings, drawings, prints and sculptures refer to the explanations in the booklet. Just over 8,000 copies of the booklet were printed in 1759, 18,000 in 1781 we can deduce from this that the exhibition attracted, in the period, between 15,000 and 30,000 visitors, which is considerable compared to the 600,000 inhabitants of Paris.

An event of this magnitude is part of the public arena and of the long term :

" Blessed be forever the memory of him who, by instituting this public exhibition of paintings102, excited emulation among artists, prepared for all levels of society, and especially for men of taste, a useful exercise and a gentle recreation, postponed among us the decadence of painting, and by more than a hundred years perhaps, and made the nation more learned and more difficult in this genre !

It's the genius of a single artist that makes the arts flourish it's general taste that perfects artists. Why did the Ancients have such great painters and sculptors? It's that rewards and honors awakened talent, and that the people, accustomed to looking at nature and comparing the productions of the arts, were formidable judges. " (Preamble to the Salon of 1763, Ver IV 236, DPV XIII 339-340)

The taste /// is a public production not the detached judgment of a singular consciousness, but the movement, the collective expression of a culture and a history103, which not only appreciates the works made, but influences the works to be made, awakens, stimulates and perfects creation. A dialectic of taste takes shape here, linking the singular manifestation of genius to a "general taste", as well as the instruction of the nation and the judgment of the people to the intimate pleasure of the man of taste. This dialectic embraces the form of the democratic political game, without its content :

" I exclude eloquence : true eloquence will only show itself in the midst of great public interests. The art of speech must promise the orator the first dignities of the State without this expectation, the mind, occupied with imaginary and given subjects, will never heat up with a real fire, a deep warmth, and we will only have rhetors. To speak well, you have to be a tribune of the people or be able to become a consul. After the loss of liberty, there were no more orators in either Athens or Rome declaimers appeared at the same time as tyrants. " (ibid.)

Diderot's tribute to Louis XIV that opens the Salon de 1763 is therefore a perfidious tribute : the man who endowed France with an Academy responsible for organizing the Salons is also the absolute monarch who makes the political exercise of public eloquence impossible in France, an impossibility whose rigors Diderot, imprisoned in Vincennes, prevented from publishing the Encyclopédie, harshly experienced.

Diderot's thinking on art is marked by this ban. It's a description lacking in eloquence, a barred writing, of the blind, the prisoner, the outlaw, a writing e tenebris. But at the same time, buoyed by the hope of the century, opening from the most unexpected intimate breach a revolutionary public space, Diderot's taste gives birth to a gaze in luce, the gaze of the Enlightenment.

The encyclopedic canon