I. The blink test

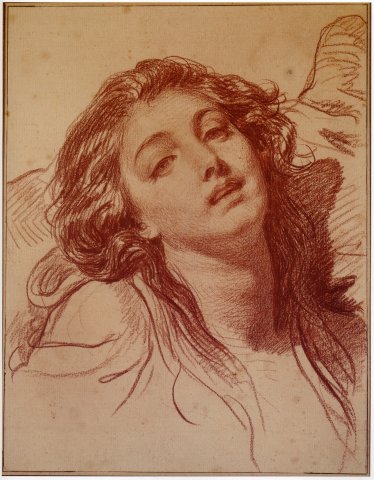

Fragonard - The love letter

In the first volume of the Encyclopédie, the following paragraph can be read at the article AMOUR DES SEXES:

" There is only one kind of love : but there are a thousand different copies of it. Most people take for amour the desire for joy. Do you want to fathom your feelings of good-faith, & discern which of these two passions is the principle of your attachment : question the eyes of the person who holds you in his chains. If his presence intimidates your senses & contains them in respectful soûmission, you love him. True love forbids even the thought of any sensual idea, any flight of the imagination which might offend the delicacy of the object loved, if it were possible for him to be informed but if the attractions that charm you make more of an impression on your senses than on your soul this is not love, it's a bodily appetite. "

Like many articles in the Encyclopédie, and in any case like all AMOUR articles, AMOUR DES SEXES is anonymous. The title, AMOUR DES SEXES, is a strange one, not referring to any common expression. It's explained by the way love is used in the article nomenclature: LOVE, then LOVE OF THE WORLD (i.e., of the world's mundanity, in particular libertinism understood as a social practice), then LOVE OF GLORY, then LOVE OF SCIENCES AND LETTERS, then LOVE OF NEIGHBORS, then LOVE OF SEXES, then CONJUGAL LOVE, then PATERNAL LOVE, then FILIAL AND FRATERNAL LOVE, then LOVE OF ESTIMATE, then LOVE-PROPER & of ourselves, then AMOUR OR CUPIDON, then AMOUR, painting with love, then AMOUR in Falconry (flying with love, means letting birds fly free), then SAINT-AMOUR, a town in Franche-Comté, then the river AMOUR in Eastern Tartary, then the AMOUROUS muscles, which give the eye an oblique movement, and make it do what we call œillades.

There's a logic to this declension : the Encyclopédie first considers social relationships, love develops sociability ; the world, glory, science, and bringing all this together the next. What's at stake in love is the Other. Next comes what founds and orders the family unit: the relationship between the sexes, then between spouses, then between children, then between children. Then comes the relationship with oneself: esteem, self-esteem, self-love. Finally comes the encyclopedic section of the dictionary, with its jumble of myths, techniques, trades, geography and anatomy. The œillade, which closes the series, mischievously refers to the worldly libertinism that opened it.

In this nomenclature, AMOUR DES SEXES has almost no place : after the social relationship that love establishes, and before the system of family relationships that it structures, AMOUR DES SEXES introduces a sexual infrastructure of sociability, it founds in kind a private relationship, just as the public relationship, in what it has of most serious, generous, glorious, was founded from the frivolity of libertine play and desire. There is thus a symmetry of foundations : Love of the world for glory, science and neighbor, Love of the sexes for spouses, and thence fathers, sons and brothers.

L'article AMOUR DES SEXES nonetheless disturbs the settled order and /// symmetrical to this beautiful nomenclature. There are not, he says, several kinds of love, as the declension of the dictionary entries might suggest. There is only one love, l'amour, c'est l'un, dans l'amour," says Lacan, Y a d'l'un. But there are a thousand different copies, which immediately attacks the very principle of nocmenclature : all these entries Amour ceci, Amour cela, are simulacra, we get lost, we get out of love. As a result, there are only two categories: love and its copies, love and the desire for jouissance, love and jouissance.

Hence the idea of a test. To find out whether you're dealing with love or a desire for jouissance, question the eyes of the Other; everything happens in the eyes, so we now understand why this affair begins in libertinism and the desire to please and ends in a blink. Either the " charm des prunelles " (to borrow a phrase from Zadig) works, and it's love that's at stake, or it doesn't, and it's jouissance that's on the mat. So, in the erotic relationship with the other, there are two clearly differentiated practices one is a " bodily appetite " it establishes this relationship through the body, which it dominates, possesses, and perhaps also damages because it is shameless. This practice is jouissance it worries us and arouses a certain moral disapproval. Enjoyment is the pleasure derived from sexual intercourse, a pleasure that society views with suspicion, contempt and scandal. We even wonder whether this relationship, inevitable for the reproduction of the species, shouldn't take place without jouissance. It would perhaps, no doubt, be more moral, cleaner.

The other erotic relationship to the other is established quite the opposite of jouissance, through the mind. It " intimidates the senses ", it's love : love imposes submission and respect, it's all about delicacy. Love cannot therefore arouse moral reprobation, for it is cultura anima, education of the soul :

" I fear nothing for morals from love, it can only perfect them it is he who makes the heart less fierce, the character more binding, the mood more complaisant. By loving, we have become accustomed to bending our will to the liking of the person we love we thereby acquire the happy habit of commanding our desires, mastering them & repressing them conforming our taste & our inclinations to places, times, people but morals are not equally safe when we are worried by those carnal protrusions that coarse men confuse with love. " (LOVE OF SEXES, Encyclopédie, I, 369)

Love's submission to the Other is a morality police force. In this, love is opposed to jouissance and its " carnal protrusions " - the term is crude, animalistic, referring to the bestiality of sexual intercourse - the enemy is in a way designated, it's not love, it's jouissance !

.We need to grasp here what is at stake in what is shifting and reconfiguring in the movement of Enlightenment thought. The moralization of love, its full social acceptance, presupposes the creation of a new category in which to place reprobation; this category will be enjoyment. The boundary between what is permitted and what is forbidden shifts: everything is now permitted and even celebrated in love, in the social and family game of the love relationship, on condition of an unprecedented and violent repression of sex, on condition of a displacement, or rather an attempt to displace jouissance below the bar of the licit, the bar of the dicible, below the semiotic cut-off point. From then on, jouissance is defined as a projection, an (e)jaculation of this bodily, bestial, shameful en deçà towards the surface of the dicible and the signifier, as an overflow, or return, from the signified into the signifier.

II. Are there two /// love ?

This conceptual pairing of love and jouissance, the good and bad relationship between the sexes, is invented here, in 1751, in this article AMOUR DES SEXES. It replaces another relationship, which preceded it, and which is apparently presented as the relationship of two loves: sacred and profane, celestial and terrestrial, virtuous and lustful. According to tradition, Titian proposed an allegorical representation of this in 1514, which is as famous as it is enigmatic, in a painting currently housed in the Galleria Borghese in Rome.

.Two women sit on the edge of a fountain, in a country landscape. Between them, young Cupid plays with the fountain water, where he dips a hand. To the left, Love, in a long gown whose sleeves completely cover his arms, gloved, turns away from the child to look directly at the viewer. The young woman is seated on the edge of the fountain, occupying the space. On the right, Love, almost naked, with a light cloth running carelessly over his thighs and a scarlet drapery slipping from his left shoulder, leans with his right hand on the edge of the fountain to lean towards his son, while with his left hand he holds, raised above her, a small urn steaming with incense. This second woman comes to lean against the fountain, but remains in the corner: this is not her territory

.There is no apparent, immediately visible interaction between the two women. Everything is held together by a system of compensated imbalances : the fountain factory, supposed to unite the two women, is shifted to the left, it is the territory of Amour vêtu. Cupid, placed in the center of the fountain, is thus brought closer to her, even though he is the son of d'Amour nu, who, brooding over him with his gaze, signifies this to us.

.The title of this painting is L'Amour sacré et l'amour profane, but this title only appeared to designate it at the turn of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries1, almost two centuries after its execution, leaving us to speculate about the interpretation of this allegory. Erwin Panofsky proposed a resounding interpretation2 : influenced by Florentine neo-Platonism, the young Titian is said to have overturned medieval symbolism and depicted profane love clothed, identifying the beautiful naked Venus with sacred, celestial love, stripped of its earthly envelopes. For this, Panofsky draws on the theme of the double Venus developed by Marsilio Ficino3 following Pausanias' speech in Plato's The Banquet and its interpretation by Plotinus. On the other hand, he relates Titian's painting to a medal attributed to Michelet Saulmon, valet de chambre and painter to Duke Jean de Berry from 1401 to 14144, the so-called Constantine medal5, depicting the emperor on horseback on the obverse and an allegory of two women, one nude and the other clothed, on either side of a fountain on the reverse. According to E. Panofsky, this medal may have been known to Titian, who drew inspiration from it for his composition, inverting the meanings of nude and clothed.

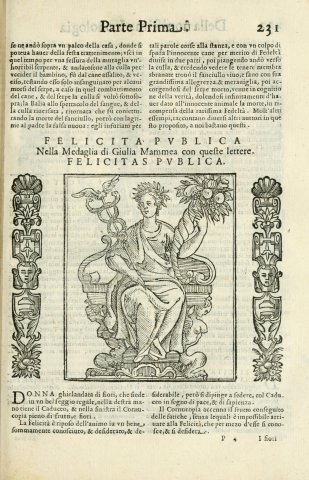

E. Panofsky's interpretation is seductive it makes Titian's painting a manifesto of nascent humanism, which identifies spiritual elevation with the nudity and beauty of the female body, breaking with an austere representation of spiritual morality as detachment from and rejection of the body. But it is also counter-intuitive: we are naturally inclined to identify sacred love with the woman dressed in white who looks at us with sternness, and the dazzling white of her dress, which occupies all the space on the left of the canvas, can only signify chastity and purity, in contrast to the red of passion draped over the seductive Venus on the left, who entices us with a totally profane sway. Of course, Titian's Nude Venus is far more seductive: it reminds us of the primary power of painting, which is a power of the eyes, a power of sensual seduction whose spiritual finality can only be felt at the end of a whole process. Moreover, while examples of the identification of the nude with the profane and the clothed with the sacred abound, reverse examples are rare, late and unconvincing : these are essentially the allegories of the Felicità in Ripa's Iconology, the 1st edition of which dates from 1593, and the 1st illustrated edition, from 1603. Yet there are not two but three Felicità, only Felicità publica gives rise to an image and the description of Felicità breve evokes a white and yellow garment, whereas our clothed Love is dressed in white and... red.

But above all, the deciphering of a small detail on the sarcophagus that takes the place of the fountain definitively calls this interpretation into question : right next to the pipe from which the fountain's water escapes, Titian has depicted a coat of arms, with a lion's head at the top and a writhing snake at the bottom. Typically, the coat of arms refers to the canvas's patron, who has been identified as the Venetian Nicolò Aurelio, secretary to the Council of Ten, on the occasion of his marriage to Laura Bagarotto, daughter of a Paduan jurist, a marriage celebrated in 15146. The figure on the left represents Laura in her white wedding dress, her head girded with a crown as is traditional at the wedding7. The figure on the right is now interpreted as an allegorical figure accompanying the bride, a symbolic, tutelary Venus. This interpretation at least partially preserves E. Panofsky's moralizing neo-platonic reading: Laura the bride on the left, beneath her austere, chaste appearance as a married woman, is a woman in love, and her pure love for her husband is embodied, as a neo-platonic idea of love, in the naked, red-draped Venus on the right of the picture. There is, as it were, an exteriority and an interiority to Laura, a social propriety and a loving ideal.

But how could such an accompaniment of the bride by a Venus in red signify the amorous asceticism whose process Ficino describes ? And if it's a question of inside and outside, wouldn't the painting cast a terrible suspicion on the young bride ? Instead, we propose to interpret the two figures according to an overall allegorical syntax as figures of Laura before and after marriage, and the painting representing marriage as the conversion of Laura's love from virginal, profane love on the right to conjugal, sacred love on the left.

III. Life, youth, love : the hijacking of a medieval mystical allegory

If the hypothesis of the reversal of the nude and the clothed must therefore be abandoned, E. Panofsky's interpretation remains extremely fruitful, if only for the comparison she draws between Titian's painting and the Medal of Constantine. Let's take a closer look at the meaning of the medal's allegory. The medal's fountain is the fountain of life of the allegories of the mystic lamb, which can be compared with that of Van Eyck's contemporary polyptych, the Ghent Altarpiece (B1039), or the panel by the Master of the Fountain of Life, preserved in Prague, itself contemporary with Titian (A0564) : in the latter painting, the identification of the fountain of life with the Passion cross, as in the Constantine Medal, is explicit.

.The figure on the left of the medal, who is clothed, is picking one of the flowers spouting from the fountain, thus nourishing herself from this source : she therefore represents religion, faith, sacred love if you like, or eternal bliss. She corresponds in every way to Titian's clothed woman, who for this reason holds white carnations in her hands, symbols of faithful passion, not because she wastes them, but because she harvests them. The figure on the right, on the other hand, is provocatively undressed and teasing a small dog with her foot. She's a courtesan, she's Lust, or brief bliss. She ostentatiously turns her head to the right, turning away from the fountain, refusing salvation from the fountain of life, whose Eucharistic water is equivalent to nothing less than the blood of Christ. The identification of the two figures is confirmed by the circular inscription around the edge of the medal. It is a quotation from Paul's epistle to the Galatians, Mihi absit gloriari, nisi in cruce, Domini nostri Jesus Christi, " Far be it from me to glory, except in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ " (Ga, VI, 14). This quotation is divided into three segments first the one on the right next to the naked woman, facing gloriari, then the one at the bottom places the fountain from which the cross springs just above nisi in cruce, finally the one on the left next to the clothed woman places Domini nostri behind her back.

We shouldn't forget that this allegory is found on the reverse of the Medal of Constantine, so its meaning necessarily has to do with Christian apologetics linked to Constantine. Emperor Constantine's conversion to Christianity is recounted by Jacques de Voragine in La Légende dorée, in a chapter entitled " L'invention de la sainte croix ". On the eve of a decisive battle against the Danube barbarians, who were invading the empire under Maxentius, Constantine dreams of an angel showing him Heaven, where a luminous cross bears the inscription In hoc signo vinces, " par ce signe tu vaincras8 ". Constantine had a cross made on his flag and won the battle. He then had his mother Helena look for the true cross in Jerusalem. St. Ambrose, whom Voragine quotes, tells us that Helena was originally stabularia, at best an inn servant, but more likely a stable girl, a prostitute. Hélène had a dig made : through the discovery of the true cross, she became a saint9.

It is logically Helen who is represented here twice, first in her life turned away from the faith, on the right, then in her life sanctified by the cross, on the left : " And for this God drew her out of the garbage.... /// to raise her to a throne10. " So this is not a vague dialogue of Nature and Grace, opposing two separate, abstract and antithetical persons, but a single woman, Helen, depicted before and after conversion, first glorifying herself in her youth, trading in her seductive nudity, then turning to the Lord and the cross. Conversion is depicted without possible hesitation on the left, by the clothed woman11.

If we retain the hypothesis that this Medal of Constantine provided Titian with the device from which he composed his allegorical painting of 1514, we must now examine how he hijacked Michelet Saulmon's Gothic allegory into a Venetian humanist allegory, it being understood that this hijacking does not involve interchanging the nude and the clothed. Just as the medal depicts the same woman, Helena mother of Constantine, before and after her conversion, so Titian's painting depicts the same Laura before and after her marriage, Laura as a young girl, as a nude Venus, then as a married Laura, as a chaste matron. To do this, Titian necessarily adapts and transforms the allegory first of all, he turns the naked woman on the right towards the fountain, he gives a place also to this woman at the edge of the fountain, and he does so in full Christian iconological orthodoxy : the allegory of the fountain of life is an allegory of salvation, which in its canonical form depicts, around the fountain, only the elect and the saved. This naked beauty also leads to salvation, and is entitled to its share of the fountain. But there's a gradation: naked Venus looks towards the fountain, draws closer to it; clothed Amour occupies the fountain, sits on it, identifies with it. Similarly, the sublime Laura-Venus whom Nicolò Aurelio (whose place the viewer occupies) has just married has been converted into the wise Laura who occupies the left-hand side of the painting.

.This fountain is no longer exactly the fountain of mystical life. Titian does away with the cross, substituting it with a playful Cupid, who muddles the water playfully. Cupid is the mythical child of naked Venus, through whom Nicolò was struck by the love stroke, and the future child of married Laura; he moves from one to the other as a promise of passage from one state to the other.

IV. Neo-Platonic progression

It is undoubtedly in this central position now occupied by Cupid12 that both the neo-Platonic inflection that Titian gives to the allegory and the limits of this inflection lie: the source of life is no longer the cross, but eros, the vital and spiritual power of desire but the source of life also becomes, far from Marsilio Ficino, the promise of maternity. Naked Venus has moved closer to the fountain, even leaning against its edge to keep an eye on her son, who, all at play, has gradually moved away from her to play almost behind the figure of Sacred Love, Religion, Chastity... Clothed Love is disgruntled, disturbed, holding her closed cup close to her, while the other cup, on the right, is already empty. There's a whole story here about neighbors at the fountain, which inflects the allegory towards an unfolding in time, a progression from right to left.

.There is only one progression, from the space of fiction, the mother's gaze towards the child, to the space of the spectator (identified with the husband), his stern interpellation by the woman dressed in white. In fact, there is only one woman, first naked, then clothed, first frolicking in the games of profane love, then withdrawing into herself, reserving herself for sacred love. In any case, the sense of progression is suggested by the horizon line, which is not the only one. /// not horizontal but rises from right to left, thus indicating the direction of elevation.

It's true that it's on the right that we can make out, in the background, a church, against a castle on the left13, and that it's on the left that we see two rabbits out of their burrow, rabbits or conils in Old French, coniglio in Italian, figuring fornication. It would be a mistake, however, to interpret the signs in isolation, outside the allegorical syntax they enter. On the right, hunting and pastoral games, depicted on the plain, stand at a distance from the village and its church, separated from it by a wide river and a reservoir. It's the distance that makes sense, to remind us that these games are profane, are separated from religious life14. On the left, the rabbits are shown at the height of the hunt on the right and in the shadow of the forest. You'll have to leave this forest, climb up to the castle and, at the end of the chivalrous quest, have the door to the castle opened, or to the fortified village where the castle is located. The door is apparently open: from the love game to the door, all separation has disappeared, and the rider on the path indicates the possibility of access, of asceticism, which opposes the separation of the watercourse on the right. The significance of this exit from the wood, this ascent to the castle and this penetration of the fortress is certainly less mystical than sexual : it is the consummation of marriage.

In this logic of progression, the two women are not opposed ; they are the same woman before and after the marriage understood as conversion, the one on the right absorbed in Cupid's game, ignoring the viewer, and the one on the left facing him on the contrary, and almost reproaching : Et toi donc, quand te convertiras ?, she seems to ask : the husband too has some duties. Amour sacré is dressed in white, but her right sleeve has retained the scarlet fabric of Venus' nude drapery. She has donned the white of chastity and spiritual purity over the red of passion, or more exactly she has rearranged according to a new hierarchy the white and red with which Venus nude was already, from the start, adorned.

.

The slope of the land also indicates something else : the water in the fountain comes from the left to spill out to the right : spiritual progression is to go back up towards the source ; but natural progression orders the landscape from the source on the left, in the wood, towards the river and pond in the background. In the fountain, the water comes from the left, where Amour sacré is seated: she is the principle, the source of life. The water then flows out of the fountain through a pipe concealed by a wallflower on the right, symbolizing constancy and fidelity. The wallflowers bloom on the left, on the side of sacred Love, while the water that pours out prevents them from blooming on the right, on the side of profane, inconstant Love. The theme of outpouring, spilling and loss is repeated: the cup above the pipe is empty, and naked Venus scatters the incense from her incense burner to the winds. Hybridizing mythological references and Christian symbolism, Titian endows Amour profane with the perfume burner of Mary Magdalene15, the prostitute to whom Jesus first appears after his resurrection, to whom among the first is promised a place in the kingdom of Heaven in a Noli me tangere painted the same year (A5148), Titian adopts the same symbolism of white and red, and we find the incense burner in Mary Magdalene's left hand.

Finally, the fountain is depicted in the manner of an ancient sarcophagus with bas-reliefs, the exact meaning of which has not been definitively elucidated. On the right, I propose to identify the drunkenness of Silenus, molested by Chromis and Mnasyle under the gaze of the nymph Aegle: this is the episode Virgil recounts in his VIth Eglogue. Silenus' drunkenness symbolizes the dangerous joys of profane love. Titian placed Nicolò Aurelio's coat of arms above this scene, as a moral warning: beware of what awaits you if you indulge in Silenus' drunkenness instead of respecting the duties of marriage! It's the same warning sent by Laura's stern, married gaze.

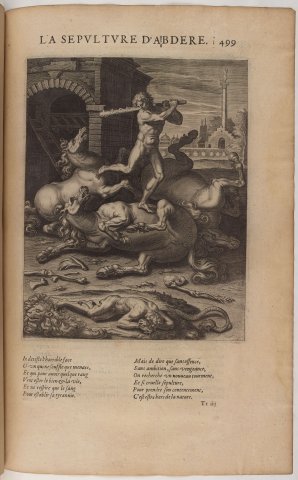

The episode on the left depicts a horse surrounded by three figures who seem to be trying to stop it. This could be Hercules taming Diomedes' carnivorous mares the horse would then be surrounded by Hercules on the left, Abdère, his companion who will be devoured in the fight, and Diomedes, whom Hercules in revenge threw to the terrible mares. The episode is the subject of the 25the painting in Book II of The Gallery of Paintings by Philostratus, which had just been printed in Venice16 : Philostratus describes Hercules' grief at the sight of his lover's shredded body common grief, however, that only Hercules was able to sublimate by founding a city in the name of the one he had lost, in Thrace, at the mouth of the Nestos river. The allegory here is more obscure and uncertain: if we follow this line of thought, however, it would represent carnal passion overcome and sublimated on the left. Can we venture this : Platonic love, in its purest form, takes homosexual desire (Hectore and Abdère) as its foundation, which it would be a question here of overcoming and sublimating, as Hercules did and as Nicolò and Laura are invited to do ?

The discreet allusion to Hercules, should it prove to be true in the interpretation of the bas-relief on the left, allows us to compare Titian's allegory with another subject very close in meaning, the choice of Hercules, also known as Hercules between vice and virtue, or Hercules at the crossroads. The two goddesses who present themselves to Hercules are sometimes one clothed, the other unclothed, always in such a way that the garment designates virtue17. But with Hercules, the monological progression towards conversion is transformed into the alternative of a choice: this is what Titian does not do. In his painting, there is neither questioning nor testing : the fountain is a place of welcome, it becomes a fountain of love, on the model of the fountain that Boiardo had just imagined in the Roland amoureux, in parody of Merlin's fountain18. Here, Boiardo inspires the conversion of the Christian allegory of earthly happiness and heavenly life (B7134), from Nature /// and Reason (B7135) or Lust and Faith (B7137) into an allegory of love, whose neo-Platonic asceticism can certainly be interpreted religiously, but just as well as a secular philosophical asceticism.

V. Lessons from Titian : unity of love, sign function, relegation of jouissance

What should we learn from this painting by Titian ? The essential lesson lies in E. Panofsky's misinterpretation, prompted by the erroneous title given to the painting in 1693. There are not two, but a single love, which Titian embodies in the portrait of a young bride, Laura, herself named after the beloved of Petrarch, the most famous poet of neo-Platonic love. This unity of love, fundamental to medieval allegory and Renaissance iconology, was no longer understood at the dawn of the Enlightenment, hence the new title given to the painting. The radical rearrangement of the categories of love in the Encyclopédie and the idea of a good and a bad erotic relationship splitting the idea of love in two stems from this misunderstanding.

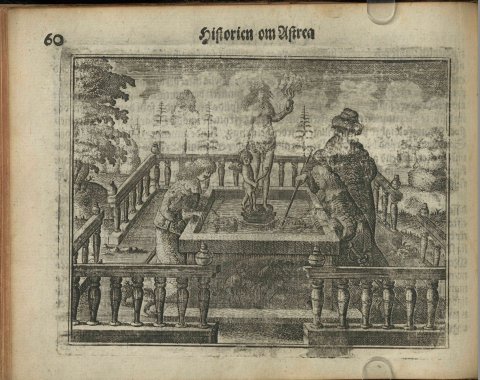

The second lesson has to do with the genealogy of the love fountain. This fountain doesn't exist until the Renaissance. There are all kinds of fountains in medieval literature, including those around which a quest or amorous encounter is played out, and Christian allegory also has its share of mystical fountains, but the love fountain we're talking about here, the modern love fountain, was born in northern Italy at the end of the 15th century as a parody of all these fountains, as a relic of a rich and diverse medieval symbolism. Titian's fountain is a transformed fountain, as indicated by the reuse of the ancient sarcophagus. It is also, in its allegorical filiation, a fountain of baptism and conversion, which is the function of the fountain of mystical life. In L'Astrée, the fountain becomes the fountain of the truth of love, separating a false from a true, introducing this separation, this division, into love. The fountain then implements in the image the function of love as sign.

The third lesson concerns the place reserved for jouissance. This place is not zero, but it is relegated. It is first represented on the left by the two rabbits, but placed on the side of marriage, in the shadow of the forest, at the base of a process of sublimation. It is then depicted on the bas-reliefs of the fountain, in all the violence and misery of a reprobated experience: the castigation of Silenus and the taming of Diomedes' mares indicate the punishment of enjoyment far more than enjoyment itself. The new, modern love being constructed here is a love that represses jouissance. From this great repression, it will be up to the Enlightenment to reinvent it.

Notes

///" The designation Amor celeste e mondano appears for the first time, it seems, in D. Montelatici, Villa Borghese, 1700, p. 288 " (quoted by Lionello Venturi, Arte, XII, 1909, p. 37 ; reprinted by E. Panofsky, Hercules..., note 459 p. 230). E.Panofsky will give in 1969 a date a few years earlier, 1693 (Le Titien, p. 164), which is the date of the first inventory of the Borghese collection.

Erwin Panofsky, " The Neo-Platonic Movement in Florence and Northern Italy (Bandinelli and Titian) ", in Essais d'iconologie. Les thèmes humanistes dans l'art de la Renaissance [1939], French trans. Claude Herbette and Bernard Teyssèdre, Gallimard, nrf, 1967, p. 223sq ; " Pour /// l'interprétation de l'Amour sacré et l'amour profane de Titien ", appendix to Hercules à la croisée des chemins [1930], trans. Danièle Cohn, Flammarion, Idées et Recherches, 1999, p. 173-178 ; " Réflexions sur l'amour et la beauté ", in Le Titien. Questions d'iconologie [1969], trans. Eric Hazan, Hazan, 1989, p. 164sq.

Marsilius Ficino, Commentary on Plato's Banquet, ed. Pierre Laurens, Les Belles Lettres, 2012, chap. 7, " Des deux genres d'Amour et de la double Vénus ", p. 38sq. Pierre Laurens here writes Amours in the plural, but the Latin does carry amoris in the singular.

I. Villela-Petit, " Quelques réflexions sur les médailles de Jean de Berry ", Bulletin de la Société nationale des antiquaires de France, séance du 25 mars 2009, Année 2012, p. 167.

See Utpictura18, record B7137. References to records and images in the Utpictura18 database will now be noted simply by the record number in brackets in the body of the text.

Kristina Herrmann Fiore (ed.), Guide to the Borghese Gallery, Éditions De Luca, 1997, p. 124.

This portrait of a married woman can be compared with the approximately contemporary portrait of Lucrezia Valier by Lorenzo Lotto (1533, see A1011).

Jacques de Voragine, La Légende dorée, French trans. J. B. M. Roze, GF-Flammarion, 1967, t. I, p. 343sq.

Ibid., p. 345-346.

Saint Ambrose quoted by J. de Voragine, op. cit., p. 346.

Similarly, in another example summoned up by E. Panofsky, a 9th-century illuminated manuscript containing the writings of Saint John Damascene (Bnf Grec 923), Saint Basil between earthly happiness and heavenly life is depicted between a naked young woman, on the left, representing profane love, and a clothed young woman, representing sacred love (B7134). Here, St. John Damascene evokes a passage from the homilies of St. Basil, which tells the story of two sisters, one lascivious, the other chaste and betrothed to Christ. The chaste girl must be given decent clothes, lest her betrothed want nothing to do with her when she appears before him. But does the image really represent the two sisters? Or does it represent Christ's fiancée, first naked and imploring the saint on the left, whose cloak she touches, then receiving on the right the golden dress of the same fabric as the saint's tunic ? In allegorical syntax, opposition is conversion. And in good Christian orthodoxy, there are neither two kinds of happiness, nor two kinds of love.

The allegory of love is almost always a threesome. In an illuminated manuscript from the early 16th century containing a collection of royal songs in honor of Marie (Bnf Français 379), we find on the recto of folio 33 an illumination depicting a nude woman and a clothed woman facing each other (B7135). It illustrates a sung dialogue between Nature and Reason by Charles Morel. But Nature is not opposed to Reason she is questioning him about Marie the main character of the song is invisible, the spiritual principle cannot be represented the two women are two means to this end. /// parvenir : " Nature. Responds reason. Raison. Fay ton propos nature. Nature. Where is marie. Raison. Intronisee es cieulx. Nature. In what honor. Raison. En regial stature. Nature. Where triumphant. Raison. With immortieulx. Nature. Looking at whom. Reason. Dieu son specieux. "

This opposition of castle and church is perhaps a borrowing from Giorgione, whose pupil Titian was. See the background landscape of the Virgin of Castelfranco (A7639). Giorgione characterized in this way the two saints he placed at the Virgin's feet, St. Francis, whom he clothed in knightly armor, like a fighting saint, and St. Nicaise, whom he dressed as a meditative monk.

The river borders the Garden of Love. See Le Jardin d'amour by Bernardino da Asola, B7144.

E. Panofsky interprets this incense burner as an oil lamp where the flame of divine love burns. But Titian has taken great care not to paint any flame, and instead to let the black smoke of incense escape : nothing heavenly in this symbol of priced pleasures.

This is a 572 p. composite in-folio collection of works by Lucian, Philostratus and Callistratus, printed in Venice by Aldus Manutius in 1503. See Bnf Res Z 248 (249, 250), Arsenal FOL-BL-1204 (1205, 1206) and Philostratus, La Galerie de tableaux, trans. A. Bougot and F. Lissarague, Les Belles lettres, La roue à livres, 1991, p. 105-106.

B3494 (quoted by Panofsky) and B3483 (Dürer's Hercules brings the fight between the two women to an end), to cite only examples predating Titian.

" In an instant love embraced [Angelica] with all her fire, as if this mighty god they wished to give run example to mortals who pretend to evade his laws. To subdue the rebellious Angelica, he undoubtedly lured her to the dangerous banks of this spring called by those who knew it the fountain of love. It was not enchanted like Merlin's fountain. Its wave naturally had the virtue of inspiring tenderness in those who drank from it, or rather of kindling in their souls an amorous fury that the water of the other fountain alone could extinguish. " (Boiardo, Roland l'amoureux, translation by A.-R. Lesage [1717], I, 9, Publications de l'Université de Saint-Étienne, 2001, p. 47.) The Orlando innamorato had begun publication in 1483, the work a great success in Ferrara. Titian worked in Ferrara for ten years, but later, from 1519 to 1529, which didn't stop him reading Boiardo from Venice. In Boiardo, there are two fountains, one of love, the other of lovelessness.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Amour et jouissance, introduction », séminaire LIPS automne 2019, université d'Aix-Marseille.

Littérature et Psychanalyse

Archive mise à jour depuis 2019

Littérature et Psychanalyse

Le Master LIPS

Séminaire Amour et Jouissance (2019-2021)

Amour et Jouissance

Jouir et Posséder

Vers l'amour-amitié

Les signifiants du désir

50 nuances de Grey

Duras, la scène vide