[p.78]

MICHEL VANLOO

This isn't Carle. Carle is dead. There are two ovals by Michel, one representing Painting, the other Sculpture. They are each 3 feet 8 inches wide, by 3 feet, 1 inch high.

The Sculpture is seated. We see her from the front, her head coiffed in the Roman style, her gaze assured, her right arm turned over and the back of her hand resting on her hip ; the other arm resting on the modeling saddle1, the trimmer in hand2. There's a bust started on the saddle.

Why this typeface of majesty ? Why the arm on the hip ? Does this workshop attitude fit well with the air of nobility ? Remove the saddle, the trimmer and the bust, and you'll take the symbolic figure of an art, for an empress.

" But it imposes." - Okay. - "But that upturned arm and wrist resting on the hip gives nobility and marks rest. " - Gives nobility, if you will. Marks rest, certainly. - " But a hundred times a day, the artist takes this position, whether weariness suspends his work, or he steps away from it to judge the effect. " - This [p.79] you say, I've seen it. What follows ? Is it any less true that every symbol must have its own distinctive character ? that if you approve of this Empress Sculpture, you will at least blame this bourgeois Painting that parallels it ? -"This first one is a good color." - Maybe a little dirty. - "Very well draped, great drawing correctness, quite good effect." - Moving on, moving on ; but let's not forget that the artist who deals with these kinds of subjects either sticks to the imitation of nature or throws himself into the emblem, and that the latter party imposes on him the necessity of finding an expression of genius, a unique, original and state physiognomy, the energetic and strong image of an individual quality. See this crowd of incoercible, swift spirits springing from Bouchardon's head and running to the voice of Ulisse who evokes the shadow of Tiresias3. See Jean Goujon's abandoned, limp, flowing naiads. The waters of the Fountain of the Innocents flow no better4. Symbols snake like them. See a certain Amour by Van Dyck5. It's a child. But what a child ! He is the master of men. He's the master of the gods. He seems to brave heaven and threaten earth. This is the poet's quos ego rendered for the first time6.

[p.80] And then, I ask you, wouldn't you rather that moody capped head7, its loose drapery8 and less arranged, and its look attached to the bust ?

Michel's Painter is seated in front of her easel ; we see her in profile. She has palette and brush in hand. She's working. She is common in expression. None of the warmth of the genius who creates. She's gray. She's bland. The touch is soft, soft, soft.

After these two pieces come portraits without number to count them all ; a few portraits, to count only the good ones.

That of Cardinal de Choiseul9 is wise, resembling, well-seated, well-fleshed, one could not be better posed nor better dressed. This is nature and truth itself. These are the clothes that have not been modeled. The more taste and true taste one has, the more one looks at this cardinal. He recalls those cardinals and popes of Julius Roman, Raphael and Vandick that we see in the first rooms of the Palais-Royal10. His fur is not otherwise available from the furrier.

[p.81] L'Abbé de Breteuil11, just as resembling, brighter in color, but less vigorous, less wise, less harmonious. All the same, the easy, uncluttered air of a grand seigneur and bawdy abbot.

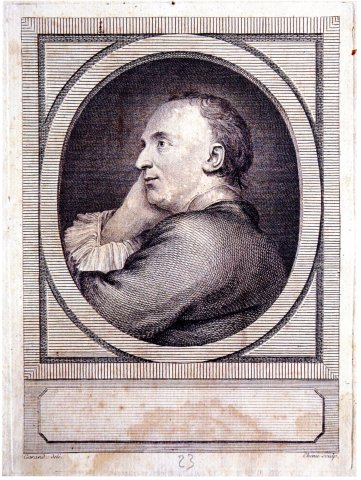

Monsieur Diderot12. Me. I like Michel ; but I like the truth even better. Quite a likeness. He can tell those who don't recognize him, like the farmer in the comic opera, cis that he's never seen me without a wig13. Very lively. It's his sweetness, with his vivacity. But too young, head too small. Pretty as a woman, leering, smiling, cute, making the little beak, mouth in heart. None of the colorful wisdom of Cardinal de Choiseul. And then a luxury of clothing to ruin the poor littérateur14, if the collector of the capitation comes to impose it on his robe. The writing desk, the books, the accessories as well as it's possible, when you wanted the brilliant color and you want to be harmonious. Sparkling up close, vigorous from afar, especially the flesh. Beautiful, well-modeled hands, except for the left, which is not drawn. We can see him from the front. His head is bare. His gray toupee with its mignardise gives him the air of an old coquette who is still being friendly15. The position, of a secretary of state, not a philosopher. The falsity of the first moment influenced everything else. It was that crazy Made Vanloo who came to chat with him, while he was being painted, who gave him that air and spoiled everything. [p.82] If she had taken to her harpsichord and preluded or sung, Non ha ragione, ingrato, un core abbandonato16, or some other piece of the same ilk, the sensitive philosopher would have taken on an altogether different character, and the portrait would have suffered. Or better still, leave him alone and let him reverie. Then his mouth would have parted, his distracted gaze would have wandered off into the distance, the work of his busy head would have been painted on his face, and Michel would have made a beautiful thing. My lovely philosopher17, you will forever be to me a precious testimony of the friendship of an artist, excellent artist, more excellent man. But what will my grandchildren say, when they come to compare my sad works with that laughing, cute, effeminate, old coquet there ? My children, I warn you that it's not me. I had a hundred different looks in a day, depending on what I was affected by. I was serene, sad, dreamy, tender, violent, passionate, enthusiastic. But I was never as you see me now. I had a large forehead, very lively eyes, rather large features, the head quite of the character of an old orator18, a bonhomie that touched very closely on the stupidity, the rusticity of the old days. Without the exaggeration of all the features in the engraving made after Greuze's pencil19, I would be infinitely better. I have a mask that deceives the artist, either [p.83] there are too many things fused together, or the impressions of my soul following one another very quickly and all painting themselves on my face, the painter's eye not finding me the same from one moment to the next, his task becomes much more difficult than he thought. I was never well done except by a poor devil called Garant, who caught me, as happens to a fool who says a good word.

He who sees my portrait by Garand, sees me. Ecco il vero Polichinello20. Mr Grimm had it engraved21 ; but he doesn't communicate it. He's still waiting for an inscription22 which he won't get until I've produced something that immortalizes me. [p.84] " And when will he have it ?" - When ? tomorrow maybe. And who knows what I may ! I'm not aware that I've used half my strength yet. So far, I've just been wandering. I was forgetting among the good portraits of me, the bust of Mlle Collot ; especially the last one which belongs to Mr Grimm, my friend. He is good. He's very good. He has taken the place at home of another that his master Mr Falconet had made and who was not well. When Falconet had seen his pupil's bust, he took a hammer and smashed hers in front of her. This is frank and courageous. This bust, in falling to pieces under the artist's blow, uncovered two beautiful ears that had been preserved whole under an unworthy wig with which Made Geoffrin had had me affixed afterwards. Mr Grimm had never been able to forgive Made Geoffrin for that wig. Thank God, here they are reconciled ; and this Falconet, this artist so unjealous of his reputation in the future, this contemptor so determined of immortality, this man so disrespectful of posterity, delivered from the worry of passing on to it a bad bust. I will say, however, of this bad bust, that one could see in it the traces of a secret sorrow of soul with which I was consumed, when the artist made it.

How is it that the artist misses the coarse features of a physiognomy he has before his eyes, and passes on his canvas or clay the secret feelings, the impressions hidden at the bottom of a soul he is unaware of ? La Tour had painted the portrait of a friend. This friend was told that he had been given a brown complexion that he didn't have. The work is brought back to the artist's studio, and the day taken to retouch it. The friend arrives at the appointed time. The artist picks up his pencils. He works, he spoils everything ; he exclaims : " I've spoiled everything. You look like a man struggling with sleep " ; and this was indeed the action of his model, who had spent the night next to an indisposed relative.

The word, ecco il vero Pulcinella, reminds me of a tale by Abbé Galiani. A missionary having set up his trestles in the Piazza di San Marco in Venice, next to a puppet player, the latter attracted such a crowd to himself by means of his Polichinelle, that the other could never get an audience. The poor missionary exhausted all the resources of his rhetoric to lure a few spectators away from his happy neighbor. Finally, seeing that he couldn't succeed, he pulled a crucifix from under his cap, and cried out in a pathetic, loud voice : Ecco il vero Pulcinella qui tollit peccata mundi. Venite et audite verbum Domini.

[p.85] Made the Princess of Chimay23, Monsieur le chevalier de Fitz-James her brother, you are bad, perfectly bad ; you are flat, but perfectly flat. In storage. No nuances, no passages, no flesh tones. Princess, tell me, don't you feel how heavy this curtain you're drawing is? It's hard to tell which of brother and sister is more roideal and cold.

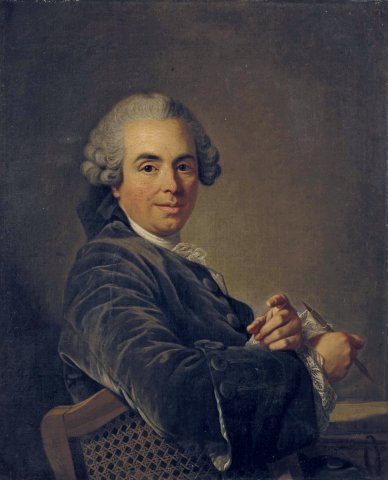

Our friend Cochin. He is seen in profile. If the figure were finished, the legs would go on the bottom. His right arm is over the back of a straw chair. The attitude is quite picturesque. He looks good. He's thin. He's going to say a scumbag or a mischief. If we compare this portrait of Vanloo with the portraits Cochin made of himself, we'll know the physiognomy we have and the one we'd like to have24. Incidentally, this one is quite well painted ; but it doesn't come anywhere near Cardinal de Choiseul.

Michel's other portraits are so mediocre that you wouldn't think they were by the same master. Where does this inequality come from, which in a fairly short space of time affects the two extremes of good and bad ? Would talent be so daily ? Would there be ungrateful figures ? I don't know. What I do know, what I see, is that there are few physiognomies more [p.86] displeasing, more hideous than that of the oculist Demours, and that La Tour did not paint a more beautiful portrait25 ; it's enough to make a fat woman turn her head away, and an elegant one say, Ah the horror. I think health has a lot to do with it.

The Little Young Man full-length, dressed in the old English fashion26, is very handsome of drapery, of natural and easy stance, charming in his simplicity, his ingenuity, of a beautiful palette ; satin and boots to delight; fabrics that couldn't be truer in the silk store. Very nice piece ; quite in the Vandick manner. It is 4 feet 7 inches high, by 2 feet 3 inches wide.

Michel Vanloo is truly an artist. He hears the big machine ; witnesses a few family paintings where the figures are large as life and commendable by all parts of the painting. This one is the opposite of Lagrenée. His talent expands with the size of his frame. Let us agree, however, that he does not know how to render the delicacy of women's skin ; that for all this variety of hues we see in it, it only has white, red and gray ; and that it works best on portraits of men. I love him, because he's simple and honest, because he's gentleness and benevolence personified. No one has the physiognomy of his soul more than he does. He had a friend in Spain27. It occurred to this friend [p.87] to fit out a ship. Michel entrusted him with his entire fortune. The vessel sank ; the entrusted fortune was lost, and the friend drowned. Michel learns of this disaster, and the first word that comes to his mouth is, Ihave lost a good friend. That's worth a good painting.

But let's leave painting there, my friend, and do a little moralizing. Why does the tale of these actions we [know28] the soul suddenly, in the strongest and least thoughtful way, and why do we let others see all the impression we get of it ? Believe with Hutcheson29, Smith30 and others that we have a moral sense31 fit to discern the good and the beautiful is a vision that poetry can accommodate, but philosophy rejects. Everything in us is experimental. The child sees early on that politeness makes him agreeable to others ; and he bows to its antics. In later life, he'll know that these outward displays promise beneficence and humanity. At the recital of a great deed our soul embarrasses, our heart moves, our voice fails us, our tears flow. What eloquence ! what praise ! We excited our admiration. We put our sensibility on the line. We show that sensitivity. It's such a beautiful quality ! We strongly invite others to be great. We have so much interest in it ! We'd rather recite a good deed than read it alone. The tears it tears from our eyes fall on the cold pages of a book. They exhort no one. They recommend us to no one. We need living witnesses. How many secret and complicated motives in our blame and praise ! The poor man who picks up a louis doesn't suddenly see all the advantages of his find ; he's no less keenly affected. Our habits are formed so early that we call them natural, innate ; but there's nothing natural, nothing innate like fibers32 more flexible, more rosolid, more [p.88] or less mobile, more or less willing to oscillate. Is it happiness, is it unhappiness to feel keenly ? Is there more good than bad in life ? Are we more unhappy with evil than happy with good ? tany questions that differ only in terms?

Add that most of these questions are idle, and that one neglects to bring into their solution the real elements, such as the force of habit, the prestiges of hope, etc. Moreover, the philosopher is right to mock the moral sense of the English metaphysicians ; but he does not explain the way in which the impression of a beautiful action is made on our organs. In addition to imitation and habit, there's something else that goes on inside us, something mechanical, that we need to know how to explain. The true treatise on moral sentiments would be a pure treatise on mechanics ; but the most perfected anatomy will never give us this theory. We would have to be able to observe the play of the brain, the heart, the diaphragm, the entrails, throughout life, and have eyesight subtle enough, piercing enough to see the most imperceptible oscillations.

Notes

" Saddle, is also a Sculpture term, which they use to model. It's a stand, a quarried wooden table, on which models are placed to work on them. Tabula, tabulatum Sculptorum. Otherwise known as an easel. To model or make clay figures, you don't need several tools. One grounds it on a saddle or easel, & it is with the hands that one begins to work, & that one advances more the besogne. Félib[ien]" (Dictionnaire de Trévoux, 1738-1742)

2" Splinters, Sculpture tools; these are small pieces of wood or boxwood, about seven to eight inches long; they go rounding at one end, & at the other they are flat & mitered. Some are joined at the end, which is mitered, and are used to polish the work; others have waves or teeth. They are called bretelés ébauchoirs; they are used for brewing clay. See Sculpture Plates." (Encyclopédie, V, 213b, 1755 and Tome VIII of the Plates (vol. 29), "Sculpture of all kinds", #021112 and more specifically Plate 3, "Différens ébauchoirs de buis ou d'ivoire", which resemble spatulas)

See #010197.

See #021114.

See #021115. Diderot knew this painting only indirectly, either from Poletnich's engraving (#021116) or from Michel Vanloo's copy of it (#021117).

" Quos ego..." Virgil's famous formula (Aeneid, I, 135) announcing the end of the storm: an angry Neptune interrupts himself mid-sentence and, in one fell swoop, puts an end to the turmoil of the waves. Although it was considered impossible to depict this change in full view, several artists took up the challenge. The most famous is Rubens (#000860), whose painting Diderot will see in Dresden (Pensées détachées sur la peinture, last page, Ver IV 1058).

Understand: Wouldn't you like the Sculpture's head better if it were styled in a hurry, if it were a little disturbed in its hairstyle.

The drape of her garment a little floaty, in motion.

See #021118.

Opposite the Louvre in Paris, the Palais-Royal housed the Duc d'Orléans' collection of paintings, one of the most important in France. Diderot had access to it. In particular, the collection housed a Jules II by Raphael (known from the engraving, #021120), a copy of the one now in London's National Gallery (#021119).

See the painting in the Château de Breteuil, which may be a copy (#021121), and the oval reduction, which is original (#021122).

See #000782.

Réplique du Jardinier et son seigneur, opéra comique en un acte by Sedaine, music by Philidor, performed February 18, 1761 at the Théâtre de la Foire Saint-Germain, Paris. In Scene 7, the Seigneur, who arrives with his retinue and dogs, completely ignores M. Simon and only has eyes for the pretty Fanchette: "M. Simon. Monseigneur, je suis... à part. He doesn't see me. [...] The Lord apperceiving Fanchette. There's a pretty girl! Fanchette. Ma mere, he's looking at us. Mme Simon. Stay there. (She adjusts her daughter's kerchief.) Mr Simon, aside. He doesn't recognize me. The Lord. Have my horses arrived? The Valet. They're at the Farm. The Lord, to one of his people, looking at Fanchette. She's so pretty! Mr Simon, aside. He's never seen me without a wig. to his wife. Laugh, you foolish girl, rather than go... to the Lord. My lord, I will... The Lord, to his people. Bring the Horses."

Augustin de Saint-Aubin, when he engraved Diderot's portrait after Vanloo's painting, endeavored to correct this. He gave him a simpler garment and a more open forehead, the figure of an intellectual rather than a courtier. See #011121.

In his letter to Sophie Volland dated October 11, 1767, Diderot writes: "I have not yet seen the Vanloo, but I will tomorrow. Michel sent me the beautiful portrait he did of me; it arrived, much to Mme Dideot's astonishment, who thought it was intended for someone. I placed it above the harpsichord of my little maid [= of her daughter Angélique]. I'd like it just as much elsewhere. Mme Diderot claims that I've been given the air of an old coquette who plays the little beak and still has pretensions. There is some truth in this criticism. Be that as it may, it's a mark of friendship from an excellent man, which must be and always will be precious to me." (CFL VII 607) The expression "vieille coquette" (old coquette), which is said to be by Mme Diderot and is found in identical form, allows us to assume that the text of the Salon was written around the same time.

Enea. E pur a tanto sdegno | non hai ragion di condannarmi. Didone. Indegno. | Non ha ragione, ingrato, | un core abbandonato | da chi giurogli fé ? (Aeneas. And yet you have no reason to condemn me to such disdain. Didon. Is there no reason, ungrateful one, for a heart abandoned by him who had sworn his faith to me?) Verses from Metastasio's Didone abbandonata (1724), which was set to music by over 50 composers until 1823, in Italy, Germany, London (but not Paris). The text was regularly printed, and scores circulated, enabling the public to play the arias to harpsichord accompaniment. Diderot was very fond of music, and his daughter was a good harpsichordist.

Diderot challenges his portrait.

That is, a Roman orator, in the noble neo-classical genre. Later in the Salon, Diderot recalls his posing sessions with Madame Therbouche, who painted him in the antique style: "His other portraits are weak, cold, with no merit other than that of resemblance, except for mine, which resembles, where I am naked to the waist and which, for pride, flesh and style, is far superior to Roslin's and to any other portraitist at the Académie. I placed it opposite Vanloo's, to whom it was playing a trick. It was so striking that my daughter told me she would have kissed it a hundred times while I was away, if she hadn't been afraid of spoiling it. The chest was painted very warmly, with passages, and flats that were quite real.

When the head was done, the neck was in question, and the top of my garment hid it, which rather annoyed the artist. To put an end to this displeasure, I went behind a curtain, undressed and appeared before her as an academy model. I wouldn't have dared propose it to you," she said, "but you've done the right thing and I thank you for it. I was naked, but completely naked. She painted me, and we chatted with a simplicity and innocence worthy of the first centuries." (DPV XVI 375) This portrait is lost but was carried to engraving: see #006254.

Greuze had drawn a head of Diderot in profile in black stone in 1766. See #002896. This drawing was immediately engraved by Augustin de Saint-Aubin (#021123), and this engraving subsequently copied by numerous engravers.

Allusion to an anecdote circulating at the time, which Diderot already reported in his letter to Sophie Volland dated September 5, 1762. Dr. Gatti returns from Italy, and the conversation turns to the carnival in Venice: "and how not to stop in a place where the carnival lasts six months, where even the monks go in masks and dominoes, and where on the same square, on one side, on trestles, you see histrions playing gay farces but of unbridled license, and on the other side, on other trestles, priests playing farces of a different color, and crying out: "Messieurs, laissez là ces misérables; ce Polichinelle qui vous assemble là n'est qu'un sot"; and pointing to the crucifix: "Le vrai Polichinelle,le grand Polichinelle, le voilà." " (CFL V 739) Grimm later takes up the anecdote in his commentary.

Garand's portrait is lost, but the engraving commissioned by Grimm has come down to us: see #006253.

Grimm would like a few lines from Diderot to inscribe below the engraving. Abbé Le Monnier would have written the following couplet: "He had great friends and jealous little ones; The sun pleases the eagle and hurts the owls." (Grimm, Correspondance littéraire, May 1771). But on the engraving preserved at Langres the cartouche is empty.

See #007023.

See the self-portrait engraved by Daullé in 1754, #021127.

See #021128.

See #010224.

Michel Vanloo had secured Rigaud's appointment as first painter to the King of Spain, Philippe V. This was where his fortune came from, and where he also lost it...

Diderot had written: saisissent-elle. The Correspondance littéraire corrects: Dites-moi je vous prie pourquoi le récit de ces actions nous saisit...

Francis Hutcheson was the author of Recherches sur l'origine de nos idées de beauté et de vertu (London, 1725). Diderot commented extensively on it in the Traité sur le beau (probably written on the occasion of Hutcheson's French translation, Amsterdam, 1749), which became the Beau article in the Encyclopédie (1752).

A pupil of Hutcheson, Adam Smith was preoccupied with moral philosophy before becoming the theorist of economic liberalism. His first substantial work is The Theory of moral sentiments (London, 1759), in French Métaphysique de l'âme, ou Théorie des sentiments moraux (Paris, Briasson, 1764).

Hutcheson, inspired by Hume, had imagined a sixth sense, or moral sense, which would lead man, instinctively, to prefer the useful. On this moral sense, Smith is less categorical than Diderot writes: "Whatever foundation we suppose to our moral faculties, whether it be a certain modification of reason, an original instinct called the moral sense, or some other principle of our nature, it cannot be doubted that these moral faculties have been given to us to direct our conduct in this life. (ed. PUF, 2014, 3e part, chap. 5, p. 229-239)

These fibers are the nerves, which Diderot, in Le Rêve de D'Alembert, represents as sensitive cords.

Les Salons de Diderot (édition)

Archive mise à jour depuis 2023

Les Salons de Diderot (édition)

Salon de 1763

Préambule du Salon de 1763

Louis-Michel Vanloo (Salon de 1763)

Deshays (Salon de 1763)

Greuze (Salon de 1763)

Sculptures et gravures (Falconet, Salon de 1763)

Salon de 1765

La Chaste Suzanne (Carle Vanloo, Salon de 1765)

Boucher (Salon de 1765)

La Justice de Trajan (Hallé, Salon de 1765)

Chardin (Salon de 1765)

La jeune fille qui pleure son oiseau mort (Greuze, Salon de 1765)

La Descente de Guillaume le Conquérant en Angleterre (Lépicié, Salon de 1765)

L'antre de Platon (Fragonard, Salon de 1765)

Sculpture (Salon de 1765)