The narrative engravings come after the performative engravings. This semiological type represents a compromise formation between the old performative type inherited from illumination and the new scenic type that has already become widespread in painting. Narrative engravings seek to mimic the very movement of narration: unlike comics, although several successive episodes are represented, the space of the engraving is not compartmentalized. The space of narrative etchings is deliberately heterogeneous, containing several times and places. The same character is depicted several times contiguous spaces in the etching refer to spaces that, in the story, may be far apart.

From Atlant's castle to Alcine's palace : Roger's prisons ; Guinevere's story (chants IV to VII)

The comparative analysis of the illustrations for Canto III has highlighted a major problem for the draftsman-engraver: the problem of homogeneity, of continuity in the space of representation. In the old medieval logic of illumination (not narrative Gothic, but illumination of the thirteenth century and earlier, of which the Montpellier manuscript of Perceval provides an example), the unity of the representation space was a symbolic unity. in the Renaissance, with the development of linear perspective, the unity of representational space tended to become a geometrical unity: we had to act as if the space of the image were a real space, that we could actually walk through from start to finish, even if the characters and actions installed in this space were unreal.

The culmination of this transformation process is the passage from performative logic to scenic logic. Strictly speaking, then, there is no narrative logic to the performance: the narrative etching represents a transition between performance and stage, with its contradictions, backtracking or, on the contrary, unexpected bold innovations. Narrative does not exist : it is merely a precarious compromise between performance and stage.

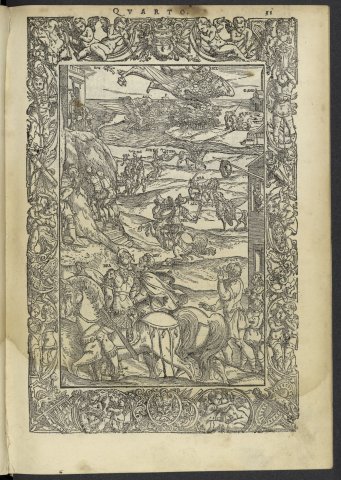

So the engraving of Canto IV in the Valgrisi edition highlights a liminal episode that seems in the text to play only the brief and technical role of clutching the narrative : the Bordeaux innkeeper at whose house Bradamante and Brunel have met points out to his guests Atlant in the sky mounted on his hippogriff. Atlant on his hippogriff at the top, the spectators at the bottom, the young woman at the window on the right, Brunel on the left, all form a narrative framework for the image, within the ornamental frame, always rich and busy in fine Renaissance editions. The narrative takes over from the decoration to ensure the unity of the picture space. But as early as the second shot, the effect of homogeneity is forgotten: Bradamante defies a second Atlant mounted on his hippogriff, who almost pushes the Atlant with the hippogriff in the foreground into the sky! The two Atlants merge into one as soon as Valvassori edition, whose smaller engravings are still very much inspired by the Valgrisi edition, with the inevitable simplifications due to lack of space. In the Franceschi edition, Girolamo Porro retains the two Atlants, but places them on either side of the castle where Roger is locked up, to avoid the effect of duplication. Eighteenth-century editions (engraving by Cochin, and engraving by the Zatta edition) select the episode of the fight between Bradamante and Atlant. What constituted the performance of the song becomes a scene, whose theatricality is constructed outside of any textual support, by the spectators the designers imagine for this fight : Bradamante's horse, the hippogriff and even Brunel tied to a tree in the previous episode !

See all notices corresponding to chant IV.

The essential problem posed by Chant V for illustration is that of the long embedded narrative through which Dalinde, Guinevere's maid, learns from Renaud, who has just rescued her, the story of Polinesse's treachery. The Valgrisi and Franceschi editions do place Dalinde in the foreground, riding in rump behind Renaud's squire and telling her story, but the story itself is not depicted. The Valgrisi edition does, however, resort to a subterfuge by symbolically depicting Polinesse's treachery as a stump from which a spit springs, taking up a simile advanced by the character himself in stanza 23. In the Valgrisi edition and other contemporary woodcuts, however, the central object of the representation remains the feat of Renaud killing Polinesse. Girolamo Porro in the Franceschi edition breaks with this hierarchy, however, making Renaud's journey through the town of Saint-Andrews the common thread and central element of his illustration. This is a rare example of pure narrative logic in an engraving, with the knight's route metaphorizing the narrative route. Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century editions, on the other hand, exploit a decisive element of Dalinde's narrative, absent with one exception from sixteenth-century engravings : Polinesse's ruse is organized around Guinevere's balcony, which becomes the central element of the scenic device. There's a spectacular semiotic reversal here: the ruse, a fundamental modality of a narrative based on concealment, subtraction outside the field of the visible, shifts to a visual device, centered on what, by breaking in, is given to be seen. In the engraving by Moreau le Jeune, the balcony is again installed in l'espace vague, while the scene proper focuses on Ariodant's suicide attempt, in the tragic manner of the Ajax by Sophocles in that by Gustave Doré, a hundred years later, through the play of chiaroscuro, it's on the balcony that the light first fixes the viewer's gaze.

See all notices corresponding to Canto V.

With Canto VI, the problem of the relationship between narrative and allegory is raised. This problem is posed first by Ariosto's text, even before the illustrators are confronted with it. Indeed, the island of Alcine where Roger lands with his hippogriff is an allegorical island where the knight is summoned to choose between two routes, to /// On the left is Alcine's palace, with prison and death as a way out of the delights of the senses; on the right, the path to the territory of Logistille, her half-sister, as a quest for reason and a difficult path to virtue. The reference model for the Ariostian text is that of the choice of Hercules, here completely parodied and subverted : if Hercules chooses the hard and tortuous path of virtue against the easy and tempting path of vice, Roger's choice, initially virtuous, is thwarted not by vice, but by the very rituals of chivalry : it's out of courtesy that Roger leaves the derisory fight against Alcine's monsters to follow the two damsels with the unicorn it's out of chivalry and courage that he accepts the fight against Eriphile, which will nevertheless hurl him towards Alcine's palace where, at the end of the pleasures, death threatens him. Roger's journey is an allegorical one, in the manner of the Songe de Poliphile by Francisco Colonna : Roger at the fountain evokes Poliphile at the fountain the gateway to Alcine's city, described at length by Ariosto evokes the initiatory door of the Songe, but in Ariosto it represents not the beginning of a quest, but the danger of the narrative coming to a halt, the perpetual threat of Roger's confinement.

See all entries corresponding to chant VI.

The engraving of Canto VII in the Valgrisi edition clearly establishes the progression from the bottom to the top of the image, from the beginning to the end of the canto, as the passage from chivalric anti-performance to the humanist refoundation of performance. At the bottom, the fight between Roger and Eriphile, two knights facing each other and crossing their spears, takes on the forms of the agonistic face-off as depicted in medieval illuminations (see, for example, Perceval's fight against Clamadieu in the Montpellier manuscript). But Eriphile is no knight, and what's at stake is access to Alcine's ignominious palace. At the top, behind Alcine who has come out to welcome Roger and the two damsels, the banquet table takes the form of a medieval banquet celebrating the rediscovered unity of the knightly community. It is framed by the two moments of Roger's recovery: on the right, Mélisse's speech to Roger; on the left, Roger's exit from the palace in arms. The center of the engraving is the moment of suspense and reversal : Roger walks between the forest of his perdition on the left and the meeting of Bradamante and Mélisse on the right, which paves the way for his rescue (View engraving).

///Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Gravures narratives », Le Roland furieux de l’Arioste : littérature, illustration, peinture (XVIe-XIXe siècles), cours donné au département d’histoire de l’art de l'université de Toulouse-Le Mirail, 2003-2006.

Arioste

Archive mise à jour depuis 2003

Arioste

Découvrir l'Arioste

Épisodes célèbres du Roland furieux

L'île d'Alcine

Angélique au rocher

Bradamante et les peintures

La folie de Roland

Angélique et Médor

Editions illustrées et gravures

Principales éditions de l ’Arioste

Les trois territoires de la fiction

L’effet Argo

Gravures performatives

Gravures narratives

Gravures scéniques