" I see truth and virtue as two great statues raised on the face of the earth, and motionless amid the havoc and ruin of all that surrounds them. These great figures are sometimes covered by clouds. Then men move in darkness. These are times of ignorance and crime, fanaticism and conquest. But there comes a time when the cloud is parted, and prostrate men recognize the truth and pay homage to virtue. Everything passes, but virtue and truth remain1. "

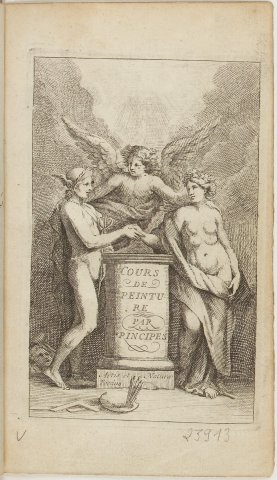

There would be a theater of truth and virtue. Its stage curtain would be the cloud of obscurantism its spotlight - the Enlightenment. Diderot's vision teaches us two things: there can be no truth without virtue - the truth of the Enlightenment is not photographic, but pedagogical; and there can be no truth without a stage on which to revere it - truth is part of a theater of truth. This theater transposes and moralizes that of the opening allegory of Roger de Piles' Cours de peinture par principes2 : Artis et Naturæ Fœdus, painting seals the alliance of Art and Nature (ill. 1).

The paradoxes of truth

The truth according to Roger de Piles

It's no surprise, then, to find a chapter devoted to " True in painting ". In it, he defines three kinds of truth, the simple truth, which is the transparent imitation of nature and objects, the ideal truth, which is " a choice of various perfections that are never found in a single model " (p. 21), in other words an ideal construction of beauty, and the compound truth, which consists in the articulation of the first two and is defined as " the perfect imitation of beautiful nature " (p. 22).

Roger de Piles makes no secret of the fact that such a conception of the true implies a triple paradox.

The first is that of simplicity : " although the natural object is true and the object that is in the painting is only feigned, the latter nevertheless is called true when it perfectly imitates the character of its model " (p. 20). In other words, the more perfect the imitation, the more perfect the deception, the greater the truth, " so that the figures seem, so to speak, to be able to detach themselves from the painting and enter into conversation with those who look at them " (p. 21). Truth is the abolition of the frame, the removal of the boundary between reality, the space of the viewer, and representation, the space of the painting. Likewise in sculpture: the paradigm of the statue is Pygmalion's Galatea, transformed into a woman of flesh through illusion3.

The second paradox is that of the idea. De Piles first characterizes the idea not by its singularity, but by its variety : " a choice of various perfections that are never found in a single model ". The true ideal is not an ideal model it can be found just about anywhere yet it is " ordinarily drawn from the antique ". So it does have a model. The true is disseminated, and the true is referenced we have to go and look for it here and there in nature, and at the same time it was always already there, at the ancient origin of our culture.

The third paradox is that of the subject. It is the idea that determines the subject, and it is in the subject that the idea is preserved. /// and appears with advantage. Yet the " legitimate subject is the true simple ", which alone prevents the reduction of " moral virtues " to " false appearances and phantoms of virtue ". The subject conditions the true compound, that is, beautiful nature as both an ideal nature, an artificial construct, and as true nature, the concrete, material reality of the objects, circumstances, events of real life.

These three paradoxes, of simplicity, idea and subject, set the framework for the classical aesthetic that Diderot is confronted with when he enters the space of the Salon. Roger de Piles' definition of the true is widely received : we find it, for example, in Hagedorn, whose Réflexions sur la peinture4 served as the basis for Diderot's Pensées détachées from 1775 to 1781.

But did Diderot read de Piles in 1759, when he began writing the Salons5 ? And if he did, was he inspired by it? It is through contact with works and artists, rather than from the theoretical writings of the time, that he will come to grips with the paradoxes of classical truth.

The simplicity of the true ? It excludes the coexistence of nature and its imitation. With the Vernet of 1763 (ill. 2), Diderot proposes a little experiment : " Look at the Port de la Rochelle with a telescope that embraces the field of the painting, and excludes the border ; and suddenly forgetting that you are examining a piece of painting, you will exclaim, as if you were placed at the top of a mountain, spectator of nature itself : Ô le beau point de vue ! " (Ver IV 271, DPV XIII 388-9). Same illusion, same pleasure in paradox in 1765 in front of Greuze's La Jeune fille qui pleure son oiseau mort (ill. 3) : " Soon we catch ourselves conversing with this child and consoling her. This is so true, that this is what I remember saying to her several times. " (Ver IV 381, DPV XIV 180). Similarly, speaking of Vernet at the 1767 Salon : " j'allais vous entretenir de ses ouvrages, lorsque je suis parti pour une campagne voisine de la mer et renommée par la beauté de ses sites " (Ver IV 594, DPV XVI 174). Sites take the place of paintings, or more exactly merge with them : " I had supposed myself to be in front of nature, and the illusion was quite easy ; and suddenly I found myself from the countryside, at the Salon " (Ver IV 625-6, DPV XVI 223). True painting is tautological: " What is this partridge ? Can't you see ? it's a partridge. And this one ? it's another ". Yet " Chardin only needs a pear, a bunch of grapes to sign his name " (Salon de 1769, Ver IV 844, DPV XVI 602). The singularity of style is paradoxically recognized by the identity of the real and the represented, which excludes manner.

The second paradox of truth would make a fortune in Diderot's thought, with the theory of the ideal model : but the notion doesn't appear until the preamble to the Salon de 1767 and only finds its full development in the Paradoxe sur le comédien. On this point, moreover, Diderot takes the opposite view from R. de Piles : the " choice of various perfections " can only produce a monster6. It is not a matter of selecting samples, but of restoring the global and progressive alteration of the ideal Beauty, conceived as Neutral, by the vicissitudes of Nature, according to an anamorphic game for which Diderot claims the " line of beauty " by Hogarth7 and Plato's The Republic. The revolt against a truth that would be obtained by disseminating membra disjecta8 comes from close observation of the paintings he describes. Before Greuze's L'Accordée de village, in 1761, Diderot overheard a woman's remark, " that this painting was composed of two natures. She claims that the father, the fiancé and the tabellion are indeed peasants, country folk ; but that the mother, the fiancée, and all the other figures are from the Paris market " (Ver IV 235, DPV XIII 271). Sometimes discordance is felt within the same figure, as in la Jeune fille qui pleure son oiseau mort : " Her head is from fifteen to sixteen, and her arm and hand from eighteen to nineteen. [...] It is, my friend, that the head was taken from one model and the hand from another..." (Ver IV 383, DPV XIV 183). In 1767, Hersé's leg, in Lagrenée's Mercure, Hersé et Aglaure, unleashed the Philosopher's verve : " This leg of Hersé at the end of which there is such a beautiful foot, this leg extended and placed on the knee, on this so beautiful, so precious knee of Mercure, is four large fingers too long [...]. Certainly, if Mercury only needs a thigh, he can carry this one under his arm, without Hersé being able to suspect it. " (Ver IV 564, DPV XIV 135, ill. 4)

Finally, the questioning of the subject as the touchstone of the work's truth does indeed occupy the Salons centrally. But Diderot approaches the question of the subject as a " poet ", that is, as a dramatist, summoning epic and tragedy to remonstrate with the painters9. Here again, the filiation does not pass through R. de Piles it mobilizes another of Diderot's experiences, his theatrical experience as author of Fils naturel.

Truth versus theater : Dorval and Greuze

To understand the strange singularity of Fils naturel, we need to imagine the climate in which the work was conceived. Throughout the 1750s, the controversy surrounding the encyclopedic enterprise had steadily escalated with each new volume published, culminating in the scandal of D'Alembert's article Genève, published in November 1757 in Volume VII, which led to his resignation in January 1758 and the banning of the Encyclopédie in March 1759. The philosophers' enemies are unleashed from all sides : it's impossible to perform Le Fils naturel on a public theater, and Diderot is accused of /// by Fréron of having plagiarized Goldoni. Was it for this reason that, when he published his play in February 1757, Diderot enshrined it in a fiction that gave the impossibility of performing it on stage a novelistic explanation ?

Diderot recounts meeting a certain Dorval, who is said to be both the real protagonist, author and actor of the play, performed in his salon, just once and without witnesses (other than Diderot in hiding), by the family, to commemorate his founding drama and carry out his father's last wishes. Dorval then asks Diderot for his impressions of this spectacle, which is not a spectacle at all, and whose unfolding he only broke in on. The three interviews on Le Fils naturel, which follow the text of the play in the original edition, are entirely worked by this founding contradiction : to all Diderot's objections to the play's departures from the rules of dramatic composition, Dorval replies that this is not a play, and that it is intended for the salon and not the tréteaux10. In other words: the rules of representation don't apply, because this play is not a play, but the truth itself. But this play, being the truth, must form the basis of the new rules of representation. Truth imposes itself in art by propagation of the simple11. The concatenation of discourses and events, their reciprocal reconciliation on the basis of simple fact, imposes natural situations against the conventions of propriety; a new rationality, metonymic, continuous, contaminating, replaces the predictive structures and categories of classical poetics, whose systems of constraint, figurative and generic taxonomies it deconstructs. Thus, for the sketch of Fils ingrat (ill. 5), in 1765, Diderot does not proceed to a description, strictly speaking, but rather to the suggestion of a situation from which to develop the canvas of a scenario :

" Imagine a room where daylight hardly enters except through the door, when it's open, or through a square opening made above the door when it's closed. Turn your eyes around this sad room and you'll see nothing but destitution. On the right, however, in a corner, there's a bed that doesn't look too bad; it's carefully covered. At the front, on the same side, there's a large black leather confessional where you can sit comfortably. Seat the father of the ungrateful son there. Adjacent to the door place a low cupboard, and very close to the old man caduc a small table on which soup has just been served. " (Ver IV 390, DPV XIV 196)

Diderot has just evoked the board game of the tableau vivant; he proceeds virtually in the same way. The eye of the spectator-reader enters the room and arranges, as naturally as possible, the props for a scenic space where all that remains is to install the characters. The moment has not yet been chosen the door is either open or closed you either enter or you don't enter the room. This opening-closing is characteristic of the stage set-up, which gives the spectator the enclosed space of the room. /// room in the fiction of a wall, a door, a screen interposed between him and her. Then Diderot pretends to proceed by successive logical deductions: what is virtuous poverty? It's an impeccable bed in a bare room. What is the furniture in a bare room? It's an armchair next to the bed, a low sideboard and a table. Who is it for ? Necessarily for the father of the family, from whom the installation of the scene's protagonists begins.

Because the situation has been logically thought out, Greuze can dispense with decorum and imagine a scene of rare brutality : the father's invective against the son (" he spares no harsh words for this unnatural child "), whom one of his daughters is holding by the arm (" by the tights of her habit "), the young man's insolent gesture (" he has his right arm raised by his father's side [...], he threatens with his hand "), blow against his mother (" the brute tries to get rid of her and pushes her away with his foot ").

The truth is this brutal indecency implacably deduced from the imagined situation. By way of contrast, we need only compare it with the 1777 painting (ill. 6) the clothes are more plush, the bed has disappeared, the recruiting sergeant no longer turns his back to the scene, the little sister delicately holds her father by the wrist, the son's hand sketches an almost shy farewell, there is no longer any question of a kick.

The truth is defeated when logical deduction from the situation created by the subject leads to a scene, a disposition, a posture, an action different from those represented by the artist. This is the case for the counterpart to Fils ingrat, Le Fils puni, which Diderot begins by showering with praise.

" But as it is said that man will do nothing perfect, I do not believe that the mother has the true action of the moment ; it seems to me that to hide from herself the sight of her son and that of the corpse of her husband, she had to bring one of her hands over her eyes, and with the other show the ungrateful child the corpse of his father. " (Ver IV 392, DPV XIV 199-200)

The mother introduces her son into the room : her two hands go in the same direction, they present the dead father. The son veils his face, the mother does not. Diderot polarizes gestures, introduces the differential play that is the hallmark of classical discursive theatricality I show, but I shy away I exhibit, but I hold back look, but I don't look. The mother's double gesture, which he imagines as " the true action of the moment ", is equivalent to the opening-closing of the door that introduced the bedroom space in the description of Fils ingrat.

No truth without this differential play that semiotizes the layout and articulates the monstration to a theatrical discourse. In L'Accordée de village, it's in the foreground " a hen leading her chicks, to which the little girl throws bread ", indifferent to the event and the paternal discourse. The same indifference is shown by " the child between the tabellion's legs [...] excellent for the truth of its action and color. Without taking any interest in what's going on, he looks at the scribbled papers, and walks his little hands over them" (Ver IV 233). In the paroxysmal scenes of Fils ingrat and Fils puni, this counterpoint indifference becomes impossible. But Greuze maintains it more or less happily, and Diderot spots the little true fact. For Le Fils ingrat, " j'oubliais qu'au milieu de ce tumulte un chien placé sur le devant l'augmentait encore par ses aboiements " (Ver IV 390). The dog adds to the scene, authenticating its truth. He's not necessary, he's there, he's proof that it's not all fabricated. And because he points outside (like the chicken, like the indifferent children), outside the theatrical fabrication of the /// representation, it somehow cancels out the artifice of this theatricality, or at least grounds it in truth12.

In The Punished Son, it's the stoup at the foot of the bed that should have played this role :

" And then the costume is wronged, in a trifle to the truth, but Greuze forgives himself nothing : the large round stoup with the pin is the one that the church will put at the foot of the bier for the one put in the cottages at the feet of the dying, it's a water pot, with a sprig of the boxwood blessed on Palm Sunday. " (Ver IV 392, DPV XIV 200)

The little true fact turns out to be false. Greuze has introduced into the private space of the mortuary chamber an object of public ceremonial, which should not be there but, at the moment of burial, near the coffin, for a final blessing. Thus, by its very impropriety, the object fulfills its function : from within, it points to the outside of the scene ; from the artificial, hyper-scenographed space we are given to see, it refers back to the real world, to the ordinary handling of death, it brings the " masterpiece of composition " and the " violent interest " of the scene back to a common norm and a simple story.

Truth as conformity

The hen is indifferent, the dog is unnecessary, the stoup is not conform : the standard of truth manifests itself each time at the edge of the classical differential game that orders representation as a system of figures. At the limit of the figures that articulate themselves to one another, someone or something doesn't articulate itself, and thus beckons towards, or from, the outside, so that truth returns as an authentication of the scenic artifice. How does this authentication work? By the addition of a conformity, the requirement for which was already apparent in Le Fils naturel :

" What is truth ? The conformity of our judgments with beings. What is imitative beauty ? The conformity of the image with the thing " (Third Interview, Ver IV 1181, DPV X 150)

This articulation of the two conformities, critical and mimetic, already outlines the field of the Salons, whose entire writing appears at once underpinned, between description and judgment, by the criterion of truth. From then on, the differentiation that Diderot still maintained in 1758 between philosophical research and the poetic demand for truth seems very tenuous:

.

" Something else is truth in poetry, something else in philosophy. To be true, the philosopher must conform his discourse to the nature of objects ; the poet to the nature of his characters. " (De la poésie dramatique, XVII, " Du ton ", Ver IV 1324, DPV X 392)

The formula seems to oppose the truth of art and the truth of philosophy : but the system of conformities is formally modeled on both sides in the same way ; and the category here maintained of " characters " shatters everywhere else13.

Boucher, the genius of forgery

Truth is the banner of the philosophers he's an encyclopedist, a fighter for the Enlightenment who comes to the Salon and looks at the works his gaze is not neutral, and Diderot intends to display himself as such. Truth is therefore his watchword, the basis for ideologically differentiating between a good and a bad camp, between artists and the real thing. /// and fake artists. Boucher is the enemy :

" What colors ! what variety ! what a wealth of objects and ideas ! this man has everything, except truth. There's no part of his compositions that you don't like you're seduced by the whole. One wonders, but where have we seen shepherds dressed with such elegance and luxury ? what subject has ever brought together in one place, in the middle of the countryside, under the arches of a bridge, far from any habitation, women, men, children, oxen, cows, sheep, dogs, bales of straw, water, fire, a lantern, stoves, jugs, cauldrons ? What's this charming woman doing there, so well dressed, so clean, so voluptuous and these children playing and sleeping, are they hers? And this man carrying fire that he's about to spill on her head, is that her husband? What does he want to do with these lit coals where did he take them ? What a racket of disparate objects you can feel the absurdity of it all with all that, you can't leave the picture. It holds you. You come back to it. It's such a pleasant vice. It's an extravagance so inimitable and rare. There is so much imagination, effect, magic and ease ! " (Salon de 1761, Ver IV 205, DPV XIII 222)

Diderot doesn't explicitly give the title of the painting he's describing, and simply reproduces the indications in the Livret : " Pastorales et paysages de Boucher ". We can recognize, however, from his description and Gabriel de Saint-Aubin's sketch14 (ill. 8), the Halte à la source preserved at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, a painting Boucher executed in 1761, and enlarged on the left side in 1765, when he signed it (ill. 9). Diderot first feigns to play along with the title : the painting gives itself for a pastoral, a landscape with shepherds, a genre scene therefore, captured in the truth of nature of a crossroads, at the entrance to a bridge.

.

The heap of objects

In fact, we recognize a Flight into Egypt15, which Boucher has somehow secularized into Pastorale : in the left foreground, the Virgin rests leaning against a trough where her donkey is drinking she watches Jesus sleep against her belly and thighs, on a bit of straw. Above her, Joseph unloads the donkey and prepares the camp: he has already stretched a red sheet as a canopy over them, in the branches of a tree. Boucher drapes the Virgin in red, the Child in blue, the colors of the Incarnation and Faith. The canopy, the colors, the characters indicate the religious basis of the scene, which Diderot, knowingly or unknowingly, glosses over.

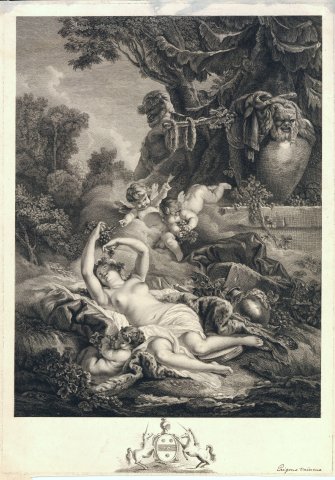

Diderot's enumeration seems malevolent it breaks the composition's order, produces a heaping effect, prohibits any circulation between objects. Yet Diderot doesn't ask questions at random " what subject ? " points to the deception of the advertised subject, a pastoral, a landscape, when it's a thinly disguised religious scene " what is this charming woman doing there ? " invites us to recognize the unreal elegance of the Virgin in what cannot be a Bohemian woman on the road ; /// the hesitation over Joseph's status (" is he her husband ? ") is, so to speak, theological16. After insisting on the characters and the actions, Diderot expressly speaks of " paysage ", to show that he is not fooled : " Quand on a longtemps regardé un paysage tel que celui que nous vient d'ébaucher, on croit avoir tout vu. But we're wrong. One finds in it an infinity of things of a price ! " (ibid.) Deliberately painting at the antipodes of truth, Boucher seduces as a virtuoso of pictorial technique. He paints by feats of strength and deploys a rare power of imagination finally, he seduces with his libertinism : " how [would visitors] resist the salience, the libertinism, the brilliance, the tassels, the nipples, the buttocks17, Boucher's epigram ? " (ibid.). It's not La Halte that has Diderot talking like this, but for example, exhibited under the same number at the 1761 Salon, the Bacchantes endormies dans un bocage & couchées sur de molles draperies(ill. 10) : a naked young woman, limply reclining on a red silk bed throw, feigns sleep, her right hand resting on her face. A plump companion, flat on her stomach on a blue blanket with yellow moiré, slumbers beside her. On the left, a satyr is watching them surreptitiously, enjoying a sleep that deceives no one: behind him, a second satyr, who is silent with an unconvinced finger, seems to be trying to steal Bacchus' thyrse from the urn's pedestal. Boucher has sprinkled the whole with white grapes and black grapes, in an unreal turquoise blue, alluding to the defeated Erigone, whom he painted on several occasions18, seduced by Bacchus changed into a bunch of grapes. Above the nymph, in an absolutely gratuitous cloud, two putti float in an uncertain equilibrium one holds suspended the bunch of temptation and the promise of the enjoyment the sleeping young woman dreams of. The urn above the satyr, with its goat-horned faun's head and festoons, is the same as that in Boston's La Halte and is found almost identically in Deshays' Érigone vaincue (ill. 11). Boucher gratuitously combines the objects of his compositions, constantly reshuffling the cards of his formal game, his art lies in this infinite variation from the same arrangements19. A woman offers herself, gallant, elegant, coquettish, in the midst of a theatrical nature, to the libertine gaze, a gaze that the very painting puts in abyme : it's Jupiter as satyr watching Antiope sleep, it's the overhang of the putti, it's the objects arranged in space like big eyes : the cauldron of La Halte, the antique urn. Here, Diderot learns about the machinery of classical painting, deployed cynically, as it were, as a pure game, of which Boucher would be the absolute organizer.

The artifice of colors

Born in 1703, Boucher was only ten years older than Diderot : Diderot's fascinated revolt against rococo, embodied by Boucher, is not simply a change of generation marked, after the Regency and then Pompadour styles, by a return to the Antique and neo-classical purity. Boucher's art attacks all the old reverence for the grand manner of religious subjects. We have seen how a Flight into Egypt could be treated as a Halt of Bohemians20. See also how Le Sommeil de l'enfant Jésus, exhibited at the Salon of 1759, genially distorts and parodies the wise Lumière du monde of 1750 (ill. 12).

In the 1750 painting, commissioned by Mme de Pompadour for the Château de Bellevue21, beige cameos dominate and the gathered holy family wisely surrounds the sleeping swaddled infant : it's a pious adoration, composed in a semicircle and open to a hole of light that links the humble stable below to the transcendence suggested above. Between the two, we can make out a miller's ladder, placed there like a Jacob's ladder to express this articulation, which is also a separation and guarantees the scene a modicum of verisimilitude.

No more of the same from 1759 : Boucher exhibited a first Sommeil de l'enfant Jésus off booklet at the 1759 Salon (ill. 13), and a second at the 1763 Salon, known today by a grisaille sketch22. But it's the color that stops Diderot :

" But color? For the color, order your chemist to make you a detonation or rather deflagration of copper by nitre23, and you'll see it as it is in Boucher's painting. It's that of a fine Limoges enamel. If you say to the painter: Mais, Monsieur Boucher, où avez-vous pris ces tons de couleur ? he will reply, Dans ma tête.... But they're fake... That's possible, and I didn't bother to be real. I paint a fabulous event with a romantic brush. What do you know... the light of Tabor24 and that of paradise may be like this ? Have you ever been visited at night by angels ?... No... Neither have I, and this is why I try as I please in a thing that has no model in nature... Monsieur Boucher, you are not a good philosopher, if you ignore that in whatever place of the world you go, and they speak to you of God, it is something other than man." (Ver IV 246, DPV XIII 355)

Diderot the braggart, the extrovert, may well have actually had this conversation with Boucher. It's in the name of verisimilitude that he reproaches him ; but it's the truth that Boucher taunts and defies by deploying the colors of his imagination. Diderot gets the message loud and clear by criticizing the verisimilitude of colors, which is a matter of pictorial technique, he has ventured into the space of painters by challenging truth, Boucher leads the counter-offensive on the philosophers' terrain.

Greuze versus Baudouin

To stand on the side of truth is to commit to the Enlightenment : does Monsieur Boucher want to interpret God on canvas ? it's man he'll have to deal with, and God as a metaphor. For the true object of art lies there in man, in morals, in the virtue that it is a question of recommending by example.

The preaching of good morals

Boucher covered in glory disdains the Salon, where he exhibits little. But his pupil Pierre-Antoine Baudouin, who was just starting out in his career, was very much in evidence. Ten years younger than Diderot, he married Boucher's youngest daughter, Marie-Émilie, in 1758. In 1763, he was received into the Académie with a Phryné of small dimensions (ill. 14), but in the great neo-classical manner : Vien would execute a César face à la statue d'Alexandre in the same vein in 1767 (ill. 15). Diderot accuses Baudouin of having put Boucher to work on his Phryné. But above all, Phryné is fake :

" She who dares to brave the gods, should not fear to die. I would have made her tall, upright, fearless, much as Tacitus shows us the wife of a Gallic general passing nobly, proudly and with downcast eyes between the lines of Roman soldiers25. One would have seen her from head to toe. When the speaker had removed the veil that covered her head, we would have seen her beautiful shoulders, her beautiful arms, her beautiful throat, and by her attitude I would have made her contribute to the action of the speaker at the moment when he said to the judges : You who sit as the avengers of the offended gods, see this woman whom they have taken pleasure in forming, and, if you dare, destroy their most beautiful work. " (Ver IV 274, DPV XIII 393)

Baudouin's timid Phryné kneeling at the bottom of the Athenian court steps becomes, in Diderot's imagination, a proud Gauloise, or a haughty Armide splitting the crowd of men and defying the gods : on the one hand, the pretty whore of a libertine fable, on the other, the heroine of the fighting Enlightenment truth is an ideological struggle.

Diderot takes advantage of the sequence of the libretto, which he follows in his descriptions, to emphasize this cleavage : Greuze comes after Baudouin, and Diderot makes him his corypheus. " That's really my man that Greuze26. " At the following Salon, Baudouin made a name for himself and gained fame, exhibiting a dozen gouaches. Diderot then emphasized the contrast between the two painters:

" Greuze has made himself a painter preacher of good morals, Baudouin, painter, preacher of bad ; Greuze, painter of family and honest people ; Baudouin, painter of small houses27 and libertines. But fortunately he has no drawing, no genius, no color, and we have genius, drawing, color, and we will be the strongest. " (Salon de 1765, Baudouin, Ver IV 375, DPV XIV 169)

The point here is no longer to judge works impartially, but to assess the strengths of his side : Diderot annexes Greuze whom he makes the spokesman for his truth. Greuze is popular, he triggers a sensitive contagion that confers a kind of immediate evidence to what Diderot wants to read as a break with rococo unrealism. In 1761, L'Accordée de village had been an insolent success bordering on scandal. In L'Année littéraire, directed by Fréron, the philosophers' bitter enemy, we read this invitation /// in the form of persiflage : " Praise M. Greuze as he deserves, without making him l'ami du Parterre, that is, a kind of Jester28. " Further on, the amphigious praise of Deshays and Greuze is denounced: " Quel galimatias ! But here is the great. [...] ...M. Greuze's paintings may one day form a complete Traité de Morale domestique...29 " To declare oneself for or against Deshays and Greuze, almost amounts to declaring oneself for or against the Encyclopédie.

Chance and code

But what's so revolutionary about L'Accordée de village (ill. 16) ? First and foremost, it's a new relationship with truth :

" At last I've seen it, this painting by our friend Greuze; but it wasn't without difficulty; it continues to draw a crowd. It's of a father who has just paid his daughter's dowry. The subject is pathetic, and one is won over by a gentle emotion as one looks at it. The composition seems to me very beautiful it's the thing as it must have happened. There are twelve figures each is in its place, doing what it should. How they all fit together! How they undulate and pyramid ! I don't care about these conditions however, when they meet in a piece of painting by chance, without the painter having had the thought of introducing them, without him having sacrificed anything to them, they please me. " (Ver IV 232, DPV XIII 266-7)

This is no longer a scene, the theatrical arrangement of an idea : " it's the thing as it must have happened ". Yet this " thing ", which is not pre-determined by any school order or stylistic artifice, has the good taste, by chance, by a pure coincidence of art and reality, to respect all the academic conventions of history painting : the pyramid composition orders the twelve figures into a single group, whose linear rigor is attenuated by the undulation of the heads, the bride on the left a little beyond, the father on the right slightly below the geometric outline.

Truth coincides with code, nature with composition, but it does so without the artist even thinking about it. The code unfolds from nature it is its natural evidence and touchstone. The pleasure, when faced with Greuze, consists in rediscovering all the tricks of classical composition, and at the same time pretending to ignore them, even pretending that the painter hadn't thought of them...

For, Diderot eventually confesses, Greuze's truth is not absolutely true :

" Teniere paints truer mores perhaps. It would be easier to find the scenes and characters of this painter ; but there is more elegance, more grace, a more pleasant nature in Greuze. His peasants are neither coarse like those of our good Fleming, nor chimerical like those of Boucher. " (Ver IV 234, DPV XIII 270-1)

Dutch painting was in vogue, its small formats and simple subjects suited to the furnishings of pleasure houses and their deceptively rustic boudoirs. In L'Homme au chapeau blanc, for example (ill. 17), we see how Teniers, before Greuze, arranges to have the pipe smokers of a tavern pyramid in front of a large plain wall that introduces the theatrical cutout. Greuze establishes this type of wall as a compositional principle, but omits the crude background in favor of a simple, discreet staircase from which a shadow disappears. /// fugitive.

Between the peasant roughness of Teniers and the mignardise of Boucher, Greuze would thus offer a middle way, with " more elegance, more grace, a more pleasant nature ". The balance, however, proved difficult to maintain. In 1765, faced with the Portrait de Mme Greuze (ill. 17) that served as a study for La Mère bien aimée, Diderot emphasized the libertine equivocation :

" Here, my friend, is something to show how much equivocation remains in the best painting. You can see this beautiful fishwife30 with her heavy stature, whose head is tilted back, whose pallid color, her headclothes spread out, in disarray, her mingled expression of pain and pleasure show a paroxysm sweeter to experience than honest to paint ; well, this is the sketch, the study of la Mère bien-aimée. How is it that here a character is decent, and there it ceases to be ? " (Ver IV 385-6, DPV XIV 188)

Here again, it's difficult to incriminate the painter's intention. Anne-Gabrielle Babuti, his wife, daughter of a bookseller on Quai des Augustins, from whom Diderot as a young man supplied himself with libertine reading31, was a young woman very sure of her attractions. Greuze had married her on January 31, 1759, but parted company with her in 1785, tired of her infidelities. Diderot suggests that the portrait reveals more truth than the artist intended, perhaps even more than Greuze knows. Mme Greuze had three daughters, Marie-Anne Claudine in November 1759, who died in infancy, Anne-Geneviève, known as Caroline on April 16, 1762, Louise-Gabrielle on May 15, 1764. In 1765, the painter could soon imagine himself at the head of a large family and project himself into the virtuous picture of family happiness that would radiate from the luminous face of his wife as a beloved Mother.

Libertine scene and bourgeois drama

Are we so far removed from Baudouin's Coucher de la mariée, in front of which Diderot pauses at length in 1767 (ill. 19) ? Here too, the subject is moral : the young woman whom her attendants lead to bed before her husband, who conjures her to his feet, falters and weeps she flaunts her virtuous modesty in a painting whose libertine scenography is perfectly superimposed on the virtuous sensibility of a maudlin bourgeois comedy scene, perfectly authorized. The very legitimate, pathetically respectful husband of the naive mourner is, after all, only fulfilling his duty, which is sanctified by a purely conventional and excellent female resistance. So it's not on the subject that Diderot attacks Baudouin, but, obliquely, on the choice of moment :

" This moment is false. If it were true, it would be the wrong choice. What interest can this husband, this wife, these maids, this whole scene have. Our late friend Greuze32 would not have failed to take the previous moment33, the one where a father, a mother send their daughter to her husband. What tenderness ! what honesty ! what delicacy ! what variety of actions and expressions in the brothers, the daughters and the children! /// sisters, parents, friends, girlfriends, what pathos he wouldn't have put into it. The poor man who imagines in this circumstance only a flock of maids. (Ver IV 668, DPV XVI 287)

Diderot folds Le Coucher de la mariée over L'Accordée de village. He substitutes paternal discourse, family order and liaison for the flickering of maids arranged around the bride for the conjunction of sex. Baudoin distributes an array of colors and frills; Diderot imagines the scene of a bourgeois drama. Baudouin's gratuitous explosion of color, the twirling lightness of his unreal figures, the gentle derision of bourgeois sociability that they mime as if playing themselves, appear to him in all the falseness of their rococo irreverence, which nevertheless prepares the autonomization of painting from poetry, the awareness of the immediate attraction that painting exerts on the eye, the closing of an imaginary, associative chamber of pre-romantic reverie.

So the interplay of fake and real doesn't exactly overlap with that of real and artifice. Baudouin is false because he contravenes morality, i.e. a previous system of verisimilitude. What is immoral is not the subject itself, but the code used to represent it, or more precisely, the economy of the code : Le Coucher de la mariée escapes the regime of theatrical discourse, to which Diderot is still attached it deploys a direct trap for the eye, without the mediation of a reading, a deciphering, truer therefore in a sense than the alternative scene proposed by Diderot : here, the eye glides effortlessly to the slit in the curtain and the opening in the bed, everything leads to it. It is this obviousness, this ease, much more than what is shown, that appears scandalous.

Diderot's embarrassment is clearer in La Mère qui surprend sa fille sur une botte de paille34 (ill. 20). He begins by announcing " an excellent thing ", but, after a careful description, he changes his mind :

" I go back on my first judgment. All this, well painted, but very well painted, is nothing but a heap of contradictions. No truth. No real taste. I am revolted by the baseness of this old woman, these straw bales, this stable, and this elegant woman and this elegant man who caresses her."(Ver IV 673, DPV XVI 295)

The " well painted " refers to a technical perfection that treacherously traps the eye what shocks Diderot once again is not so much the immorality of the subject (after all, the mother's gaze condemning the scene legitimizes its virtuous representation) as the impropriety of the two elegants in the barn, in other words the association of two incompatible worlds in the same place. Just as Greuze's truth was identified with his taste (the dog in Fils ingrat), Baudouin's defect of truth is a defect of taste. Today, we would clearly oppose an objective category, truth, and a subjective category, taste : the eighteenth century places both of them in between.

Portrait truth

More than any other artistic practice, that of portraiture is shot through with the paradoxes of truth in painting. Behind the simple word lurks " a very abstract theory35 " : like the painting36, the portrait in Diderot does not /// designates not an object, but a tendency in the process of representation.

Platonic theory of portraiture

In the preamble to the Salon of 1767, the portrait is defined by its radical opposition to the ideal model :

" if you had chosen for your model the most beautiful woman you knew, and had rendered with the greatest scrupulousness all the charms of her face, would you believe you had represented beauty. If you tell me that you have, the last of your pupils will contradict you and tell you that you have painted a portrait. But if there's a portrait of the face; there's a portrait of the eye; there's a portrait of the collar, the throat, the stomach, the foot, the hand, the toe, the nail; for what is a portrait, if not the representation of some individual being? And if you don't recognize a portrait of a fingernail as quickly, as surely and with the same certainty as a portrait of a face it's not that the thing isn't, it's that you've studied it less; it's that it offers less scope; it's that its characters of individuality are smaller, lighter and more fleeting. " (Ver IV 522, DPV XVI 64)

The portrait singularizes the figure, the antithesis of the ideal generality of beautiful nature. But above all, the principle of logical coherence that governs truth should make it possible, from the rigorous imitation of the smallest detail, to find the whole of the portrait, according to a formula that Diderot is fond of, ex ungue leonem37. Here, however, we reach the aberrant limit of the classical theory of truth. In fact, the detail is always false :

" you would not dare to assure me from the moment you took up the brush, to this day, that you have subjected yourself to the rigorous imitation of a hair. You have added you have removed ; otherwise you would not have made a prime image, a copy of the truth, but a portrait or a copy of a copy, *φαντάσματος, οὐκ ἀληθείας, and you would have been only third, since between the truth and your work, there would have been, the truth ; or the prototype, its ghost38 subsisting that serves as your model, and the copy you make of this ill-finished shadow, this ghost. Your line would not have been the true line, the line of beauty, the ideal line, but some altered, distorted, portraitist, individual line; and Phidias39 would have said of you, **τρίτος ἐστὶ ἀπὸ τῆς καλῆς γύναικος καὶ ἀληθείας. There is between truth and his image, the beautiful individual woman he has chosen as his model. " (Ver IV 522, DPV XVI 64-5)

The necessary falsity of the portrait enables Diderot to overturn the Platonic theory of imitation. Even beyond the challenge of an imitation that cannot be exact to the minutest detail, there is never a portrait because, fundamentally, the painter's ambition is not to produce an imitation, a copy of what he has before his eyes, but " une image première ", i.e. the direct representation of the idea (which is unthinkable for Plato). In this respect, the painter is the philosopher's rival: what's at stake in the production of images is the search for truth, a search that involves /// by the plastic materiality of the artistic experience, by what Diderot designates as technique.

The detail and the idea

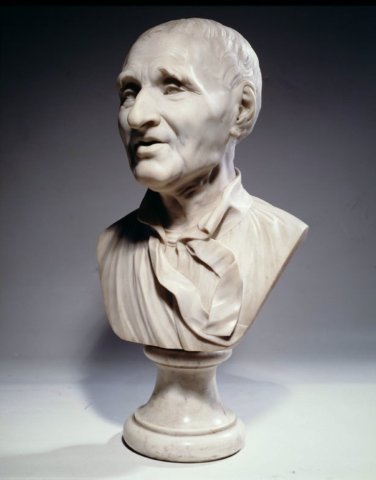

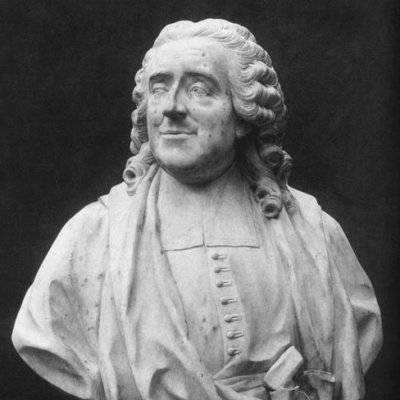

The point, then, is to turn the portrait against the portrait, to make a prime image out of the portrait. As early as 1761, Diderot sensed what was to become the founding reversal of his materialism, the sensitive recovery of the Platonic idea. Thus, in front of the bust of Falconet médecin (ill. 21), by Falconet40, he exclaims :

" Beautiful, very beautiful. Couldn't be more like him. When we've lost this venerable old man, we'll ask where his bust is, and we'll go and see it again. Also, this head lent itself well to art. Bald. Big nose. Big, deep wrinkles. A large forehead. Long strings of old age stretched from under the jaw, along the collar, to the chest a mouth of a peculiar shape. Serenity ; ingenuity, and bonhomie. " (Ver IV 229, DPV XIII 262)

The stone bust is intended to take the place of the old man of flesh at his death, occupying the same place, the same degree of truth as him in the order of representation. This truth is attested by the portrait's dissemination of details, fragments of truth: the nose, the wrinkles, the forehead, the tendons of the neck, the mouth. But are these details valid as exact copies, or rather as exemplary signs of an ideal old man's head ? " this particular head lent itself well to art " : it's true because it's general as well as resembling.

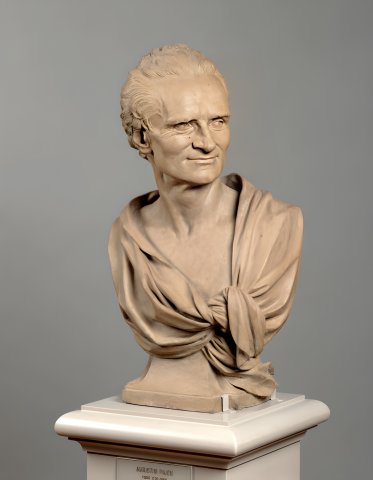

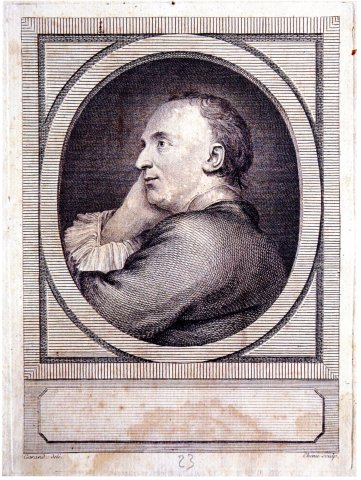

Similarly, his pupil Pajou's eulogy of the bust of Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne le fils consists in bringing it by word, incantatory as it were, to the flesh41 and to life (ill. 22 and 23) :

" He lives, he thinks, he looks, he sees, he hears, he'll talk. I'm tempted to go to your house and throw out the windows this dead block of earth that's there. " (Ver IV 200, DPV XIII 82)

Did Grimm own another bust of Lemoyne ? The truth of the portrait is exclusive, there can only be one. Regarding the portrait of the engraver Jean-Georges Wille (ill. 24), an early friend and neighbor of Diderot's, with whom the latter had " lived in the same attic " (Ver IV 362), Diderot takes up, in 1765, as for the bust of Falconet médecin, the inventory of micro-truths scattered beyond the figure :

" It's Wille's brusque, hard air, it's his stiff neckline, it's his small, fiery, frightened eye, it's his blotchy cheeks. What a hairstyle! How beautiful the drawing! How proud the touch! How true and varied the tones! /// velvet, and the jabot, and the cuffs of an execution ! I would be pleased to see this portrait next to a Rubens, a Rimbrand or a Vandyck " (Ver IV 388, DPV XIV 192).

Here again, the accumulation of singular truths turns into an ideal model, likely to rival the greatest portrait painters, Rubens, whose old man's head Diderot owned42, Van Dyck, whom he had admired in the Duc d'Orléans collection at the Palais-Royal43, Rembrandt, seen in engraving probably in Baron d'Holbach's attic44.

The secret of the portrait

The portrait thus succeeds in being true despite the fact that, theoretically speaking, truth and portraiture have been posited as two antagonistic tendencies. The effect is achieved through a reversal that turns the minutiae of true detail into a sign of general truth. The subtlety of this reversal lies in the fact that it sometimes takes place without the painter's knowledge, as when Greuze paints his wife as Mère bien aimée, in 1765. The photographic exactitude of verist painting then betrays on canvas what the didactic intention, the creative imagination, the learned composition had not foreseen. Diderot evokes this additional truth about his own portraits (ill. 25) :

" I was never well done except by a poor devil called Garant, who caught me, as happens to a fool who says a good word. He who sees my portrait by Garant, sees me. Ecco il vero Polichinello45. [...] I was forgetting among the good portraits of me, the bust of Madlle Collot46 ; especially the last one which belongs to Mr Grimm, my friend. It's good. He's very good. He's taken the place of another one that his master Mr Falconet had made and that wasn't right. When Falconnet saw his pupil's bust, he took a hammer and smashed his in front of her. This is frank and courageous. [...] I will say, however, of this bad bust, that one could see in it the traces of a secret soulache I was consumed with, when the artist made it.

How47 is it that the artist misses the coarse features of a physiognomy he has before his eyes, and passes on his canvas or clay the secret feelings, the impressions hidden deep in a soul he ignores ? La Tour had painted the portrait of a friend. This friend was told that he had been given a brown complexion that he didn't have. The work was taken back to the artist's studio, and the day was set aside for retouching. The friend arrives at the appointed time. The artist takes his pencils, he works, he spoils everything he exclaims: I've spoiled everything, you look like a man struggling against sleep... and this was indeed the action of his model, who had spent the night next to an indisposed relative. " (Salon de 1767, Ver IV 532-3, DPV XVI 84 and 514)

If Jean-Baptiste Garand caught Diderot's truth, it was by chance, just as it was by chance that Greuze encountered the classical pyramidal composition in naturally arranging L'Accordée de village. Truth in painting comes in addition to art, and in some ways against it. It manifests itself as a trace on Falconet's bust, " traces /// d'une peine d'âme secrète dont j'étais dévoré ", or on the portrait of Mme Greuze ; she spoils a portrait by La Tour by betraying a sleepless night on the part of the model. An external circumstance affects the painting, outside the pose, outside the commission's intention. And this circumstantial exterior, this additional detail, betrays an intimate truth, expresses the truth of the portrait, both as a simple (photographic) truth and as an ideal truth : Diderot as Polichinelle, as an unhappy lover, such another devoted to a sick relative, detach the portrait from the pure social order to make an image.

Or the excess of objects in Boucher, the indifference or inadequacy of detail in Greuze implemented the same movement of what Jacques Derrida designates as parergon :

" A parergon comes against, alongside and in addition to the ergon, the work done, the fact, the work but it does not fall alongside, it touches and cooperates, from a certain outside, within the operation. Neither simply outside nor simply inside. Like an accessory that we're obliged to welcome to the edge, on board48. "

A certain overabundance of art, against which Diderot rages, finds, in this very revolt, its moment of truth.

Notes

///

Deuxième entretien sur Le Fils naturel, Ver IV 1160, DPV X 122. Grimm cites this allegory as a recurring evocation of Diderot in a letter to Sophie Volland (Correspondance littéraire of August 15, 1763).

Cours de peinture par principes, composé par M. de Piles, Paris, J. Estienne, 1708 ; Gallimard, Tel, 1989.

Jacqueline Lichtenstein, La Tache aveugle. Essai sur les relations de la peinture et de la sculpture à l'âge moderne, Gallimard, Nrf Essais, 2003, and Aurélia Gaillard, Le Corps des statues - Le vivant et son simulacre à l'âge classique (de Descartes à Diderot), Paris, Champion, 2003.

Christian Ludwig von Hagedorn, Réflexions sur la peinture... [1762] traduites de l'allemand par M. Huber, tome I, Leipzig, Gaspar Fritsch, 1775, p. 85-86.

See " Diderot, le goût de l'art ", note 88.

See the beginning of the Essais sur la peinture, Ver IV 467-9 and the notion of " conspiration générale des mouvements " (Ver IV 470), opposed to R. de Piles, based on the choice, seasoning and composition of elements (Cours..., op. cit., p. 21-22).

William Hogarth, The Analysis of Beauty, 1753, read in English on the occasion of Webb's review in early 1763. See the Salon of 1765, Ver IV 349 and 351 and the satirical reference to a bust of Lemoyne in 1767, Ver IV 800. But above all Hogarth inspired Diderot's inspired flight on " the line of beauty, the ideal line ", which becomes the " true line, ideal model of beauty ", then the only ideal model (Ver IV 522-8).

On the relationship between Hogarth and the Salon of 1765, see Elisabeth Lavezzi, " Diderot et Hogarth, la pyramide et la ligne serpentine ", in Les Salons de Diderot, théorie et écriture, PUPS, 2008, p. 73sq.

This is the story of Zeuxis's Chimera (Pliny, Natural History, XXXV, 64), which /// Diderot was apparently unfamiliar with the subject. He does, however, read, or reread Pliny during his controversy with Falconet on posterity (February 1766, Ver V 616). The outline of the story, without the characters, can be found at the beginning of the Salon de 1767, Ver IV 522.

See O. Zeder, " Peindre en poète ".

See in particular in the first interview " And leave there the trestles ; enter the living room " (Ver IV 1135) ; " This is not fiction, but fact " (Ver IV 1138) ; " This is fact, not fiction " (Ver IV 1140). Second interview, " Ah ! There you go again " (Ver IV 1159) ; " And this action doesn't seem natural to you ! Recognize on the contrary, in these characters, the difference between an imaginary event and a real one. " (Ver IV 1162). Third conversation, " It seems to me that there is much advantage in rendering men as they are. " (Ver IV 1181)

Second interview on The Natural Son, Ver IV 1155-6, developed in the third interview, Ver IV 1174.

Yet this cancellation is paradoxically what determines the painter's style, manner, creative singularity : " this barking dog is one of those accessories that Greuze knows how to imagine by a very particular taste. " (Ver IV 391, DPV XIV 198)

See De la poésie dramatique, XIII, " Des caractères ", Ver IV 1311-7, a virulent plea against the " contrast of characters ", and, in the third interview on Le Fils naturel, the theory of conditions : " it's no longer, strictly speaking, the characters that need to be put on stage, but the conditions. " (Ver IV 1176-7)

Saint-Aubin's drawing is problematic for the right-hand side of the painting, where an ox can be made out on the right instead of the young people chatting beneath an antique urn, and the background appears empty, whereas it's teeming with characters and animals (including a dromedary) in the Boston painting. If it is indeed the same painting, Boucher has profoundly reworked it, notably removing the ox from the foreground on the right and replacing it on the left next to the donkey, on the added strip of canvas.

See for example Le Repos pendant la fuite en Égypte conserved at the Hermitage (inv. 11.39), and dated 1757. Acquired by Catherine II between 1766 and 1774, it may have been with Diderot as intermediary...

We see neither fire nor lit coals on the Boston canvas : Joseph holds a basket and tea towel in his left hand, and loosens the donkey's harness with his right. Diderot's error, or Boucher's additional modification ?

Grimm toned down this passage for the Correspondance littéraire : " au saillant, aux pompons, aux nudités, au libertinage, à l'épigramme ".

See the painting in the Wallace collection, dated 1745, P447, and the one in the Musée Lambinet in Versailles, inv. n°528.

We can compare these Sleeping Bacchae /// by Boucher to Deshays' Erigone vaincue, engraved in 1768 by Lévesque, where we find the urn, the hanging grape, the two putti, and even Bacchus behind the urn on the lookout like Boucher's satyr.

The reference to Bohemians is explicit in the Boston counterpart to La Halte from 1761-1765, U Marche de Bohémiens ou Caravane dans le goût de Benedetto di Castiglione, no. 1 in the 1769 Salon booklet.

Exhibited at the Salon of 1750, preserved at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, mentioned by Diderot in the Baudouin article of the Salon of 1767, DPV XVI 294.

Boucher, Le Sommeil de l'Enfant Jésus, oil on canvas curved in brown monochrome, 62.5x36.8 cm, Sotheby's Paris sale June 23, 2011, lot. 74.

" The deflagration takes place only after the nitre is molten & reddened [...]. Although nitre is not very effective on copper, it calcines it completely, reducing it to lime. This lime is used in enamel paint. If it is melted alone in a crucible, it converts into glass of a rather beautiful brown color" (Antoine Baumé, Chymie expérimentale et raisonnée, Paris, Didot, 1773, t.2, p.653. A first version, by Macquer and Baumé, was published by Hérissant in 1757)

Mount Tabor, in Galilee, is said to be the site of Christ's Transfiguration.

Allusion to Boudicca queen of the Icenaeans at the head of the Bretons' revolt in 61 ? See Agricola, 16, 1 and especially Annales, 14, 35, 1-2. But Boudicca was not handed over to the Romans : according to Tacitus, she poisoned herself (37, 2).

Salon de 1763, Greuze, Ver IV 275.

Les Petites-Maisons does not refer here to the insane asylum created in 1557 on the site of the sick bay of the abbey of Saint-Germain des Prés, but rather the gallant little residences that aristocrats and wealthy financiers had built on the outskirts of Paris to entertain their mistresses and organize parties. See Jean-François de Bastide, " La Petite-Maison ", in Contes de M. de Bastide, Paris, L. Cellot, 1763, II, 1, p. 47-88.

L'Année littéraire, Année 1761, par M. Fréron..., t. 7, Amsterdam et Paris, Lambert, p. 48, oct. 1761.

Fréron responds to the anonymous and highly complimentary author of Observations d'une Société d'Amateurs sur les Tableaux exposés au Salon cette année 1761. The italics designate quotations from the said brochure. Fréron may also be referring to a vaudeville of the time. Indeed, several took as their theme the parterre : Le Parterre merveilleux, by Denis Carolet, music by Gillier (1732), Compliment au parterre, by Guyot de Merville (1744), Crispin censeur, ou le parterre mécontent...

Op. cit., p. 50.

" Poissarde. s. f. Insulting term that Herringwomen say to each other to reproach each other for their uncleanliness. " (Trévoux's Dictionary, ed. 1771, VI, 866)

See the scene Diderot spits out about an Autre Portrait de Mme Greuze, Ver IV 386-7, and Jean Sgard, " Diderot et La Religieuse en chemise ", Recherches sur Diderot et l'Encyclopédie, n°43, p. 49-56.

Diderot had just fallen out with Greuze, no doubt because of the advances of his wife, " one of the most dangerous creatures there is in the world " (Letter to Falconet, August 15, 1767, Ver V 748).

The proposal to anticipate the moment of the scene is recurrent in the Salons. See, " Diderot, le goût de l'art ", " Le geste sublime " and note 70.

The gouache was engraved by Nicolas de Launay in 1775 under the title Les Soins tardifs : il est trop tard quand la mère se soucie de sa fille...

Diderot's precise description doesn't exactly match Les Soins tardifs. Diderot mentions a goat on the right, an angry old woman in the center, ploughman's tools on the left. Instead, we see a young mother and boy pointing their heads from the ladder up to the attic. Is Diderot's memory betraying him? Or is the gouache a simplified variant of the lost one exhibited at the 1767 Salon ? The Jeune fille querellée par sa mère, from 1765, features straw bales and old fists at the sides...

This is Grimm's commentary to the development that follows from Diderot. See CFL VII 34.

See " Diderot, le goût de l'art ", " Qu'est-ce qu'un tableau ? ".

" A l'ongle on connaît le lion, pour dire qu'on juge du tout à proportion de ses parties " (Dictionnaire françois latin de l'abbé Danet, Lyon, Deville, 1737, Ongle, p.905). See also Ver IV 629 (about the 6e tableau de la Promenade Vernet), 636 (about La Tour's portraits at the Salon de 1767), 844 (Chardin's signature, Salon de 1769). The idea was already present at the beginning of the Essais sur la peinture, Ver IV 467.

The expression is said to have been used in 1697 by Jean Bernoulli in connection with Isaac Newton's anonymously submitted solution to his brachistochronous curve problem. But Bernoulli didn't invent it : it comes from Lucian, Hermotimos ou les sectes, chap. 54 (about Phidias), transits through Michel Apostolios and Erasmus. See Apostolii Bisantii Paroemiae, Basileae, apud Ioan. Hervagium et Ioan. Erasmium Frobenium, anno D. MDXXXVIII, p. 85 (in Greek only), Michaelis Apostolii Parœmiæ, Lugduni Batavorum, ex officina Elzeviriana, anno MDCXIX, VIII, 68, p. 98 (bilingual Latin-Greek) and Adagiorum Chiliades Erasmi Roterodami... , Froben, Basileae, MDLI.

The ghost and not the thing (note by Diderot, who quotes Plato, Republic, 598b).

Phantom in the sense of representation, to stick as closely as possible to the Greek φάντασμα.

Phidias' chryselephantine Athena is invoked by Socrates in the Major Hippias to define the Beautiful (289th).

You're only in 3rd place, after the beautiful woman and beauty (Diderot's note, /// according to Republique, 597e).

Apparently Lyon physician and scholar Camille Falconet was not related to sculptor Étienne-Maurice Falconet.

Compare with Le Moyne's bust of Chancellor de Maupeou : " Le Maupeau is beautiful, it's flesh " (Ver IV 875). Diderot returns several times to the bust of Pajou, the only good thing he is said to have done since his return from Rome... (Salon de 1761, Ver IV 230 ; Salon de 1767, Ver IV 805).

Regrets on my old dressing gown, Ver IV 822.

Ver IV 531 and " Diderot, le goût de l'art ", note 123.

Diderot was already associating Rembrandt with Van Dyck when commenting on Louis-Michel Vanloo's self-portrait with his sister working on her father's portrait, in 1763 (Ver IV 243). On Baron d'Holbach's attic, see Ver IV 518.

A reference to an anecdote told in the letter to Sophie Volland of September 5, 1762 : faced with the trestles of the commedia dell'arte, in Venice, priests attempt the counter-offensive of a pious show and, pointing to the crucifix, exclaim " the real Polichinelle, the great Polichinelle, here he is. " (ed. Non Lieu, p. 335)

A replica of this marble bust, made by Mlle Collot in Russia, is kept at L'Ermitage, Palais Youssoupov, Saint-Petersburg.

Here begins a later addition to the Correspondance littéraire, which we read in the Vandeul and Leningrad copies, in the Coppet mansucrit and the 1798 Naigeon edition.

Jacques Derrida, La Vérité en peinture, " II. Parergon ", Flammarion, 1978, Champs, p. 65.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Peindre en philosophe : le pari de la vérité », Le Goût de Diderot. Chardin, Greuze, Falconet, Hazan, 2013, p. 91-127.

Diderot

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Diderot

Les Salons

L'institution des Salons

Peindre la scène : Diderot au Salon (année 2022)

Les Salons de Diderot, de l’ekphrasis au journal

Décrire l’image : Genèse de la critique d’art dans les Salons de Diderot

Le problème de la description dans les Salons de Diderot

La Russie de Leprince vue par Diderot

La jambe d’Hersé

De la figure à l’image

Les Essais sur la peinture

Atteinte et révolte : l'Antre de Platon

Les Salons de Diderot, ou la rhétorique détournée

Le technique contre l’idéal

Le prédicateur et le cadavre

Le commerce de la peinture dans les Salons de Diderot

Le modèle contre l'allégorie

Diderot, le goût de l’art

Peindre en philosophe

« Dans le moment qui précède l'explosion… »

Le goût de Diderot : une expérience du seuil

L'Œil révolté - La relation esthétique

S'agit-il d'une scène ? La Chaste Suzanne de Vanloo

Quand Diderot fait l'histoire d'une scène de genre

Diderot philosophe

Diderot, les premières années

Diderot, une pensée par l’image

Beauté aveugle et monstruosité sensible

La Lettre sur les sourds aux origines de la pensée

L’Encyclopédie, édition et subversion

Le décentrement matérialiste du champ des connaissances dans l’Encyclopédie

Le matérialisme biologique du Rêve de D'Alembert

Matérialisme et modélisation scientifique dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Incompréhensible et brutalité dans Le Rêve de D’Alembert

Discours du maître, image du bouffon, dispositif du dialogue

Du détachement à la révolte

Imagination chimique et poétique de l’après-texte

« Et l'auteur anonyme n'est pas un lâche… »

Histoire, procédure, vicissitude

Le temps comme refus de la refiguration

Sauver l'événement : Diderot, Ricœur, Derrida

Théâtre, roman, contes

La scène au salon : Le Fils naturel

Dispositif du Paradoxe

Dépréciation de la décoration : De la Poésie dramatique (1758)

Le Fils naturel, de la tragédie de l’inceste à l’imaginaire du continu

Parole, jouissance, révolte

La scène absente

Suzanne refuse de prononcer ses vœux

Gessner avec Diderot : les trois similitudes