L'île d'Alcine, or the erasure of allegory

L'île d'Alcine is an allegorical island: the war between the two half-sisters, the Logistille fairy, whose name evokes the Logistique fairy from Songe de Poliphile, and the Alcine fairy, who animalizes and vegetalizes her lovers in the manner of Circé, is the eternal war of reason and passion, virtue and vice.

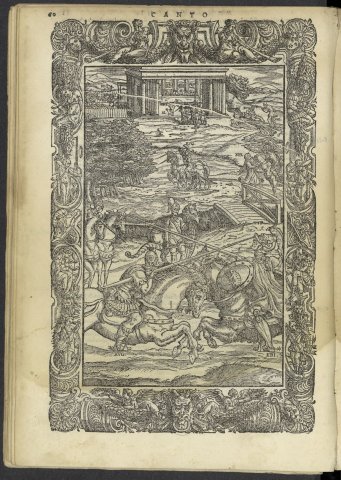

It's the engravings in the Valgrisi edition that make the most of this allegorical framework, particularly in the central intermediate spaces that almost always depict suspense, the balancing act between affirmation and negation of values: the division of episodes between left and right is often symbolic here. In Song VI, Alcine's path is on the left and Logistille's path is on the right.

In Canto VII, the forest leading to Alcine's palace, in the manner of allegorical forests depicting the soul's wandering, is on the left, while the saving appearance of Mélisse and Bradamante is placed on the right, this corner of Brittany coming to crash unabashedly close to Eriphile's bridge, located on Alcine's exotic island. Roger turns his back on Bradamante to go deeper into the forest: this posture does not correspond to any event in the narrative, but represents the symbolic framework of the story. In Canto VIII, Roger's unglamorous fight against the gyrfalcon hunter and the hermit's demonic preparations are placed together on the left, as symbolic equivalents, even though the actions are unrelated in narrative order and take place in different places. Mélisse, on the other hand, returns Astolphe to his human form to take him to Logistille, and is placed on the right: access to virtue requires the stripping away of all magic. Between the two, Roger walks along the bank from right to left, in the same direction as in Canto VII.

This direction has no geometrical significance : Roger doesn't go from Mélisse to the hermit; the direction is symbolic: the middle of the engraving (or song) is the time of the wavering of values, of the slide from right to left, before the resumption of the top (or end), even if in this case Roger nevertheless takes the path back to Logistille.... In Canto IX, the symbolic wavering to which the central space of the engraving is devoted is magnificently stylized by the tossing of Roland's ship in the storm.

.

The engravings by Girolamo Porro in the Franceschi edition, on the contrary, tend to make this intermediate space of symbolic swaying disappear, where the allegorical framework of the narrative is most visibly manifest. When the top of the engraving is not treated in the manner of a painting, given to view from below, the movement of the eye from the bottom to the top of the image organizes the passage from a space of performance (turned upside down, parodied) to a space of the scene figured by the paving of an esplanade (Canto VII, compare with the illustration of Canto XII in the Valgrisi edition) or the sea (Canto IX).

The disappearance of the in-between space crushes the sinuous movement of the narrative path in the image, a movement that is never put to the test. /// foreground: the road, in the engravings of chants VI and VII of the Valgrisi edition, is barely visible, less visible than the systems of symbolic opposition, from the right to the left of the image.

The comparative study of Ariosto's illustrative engravings thus allows us to arrive at this unexpected conclusion, to say the least: between performance and stage, between these two logics of the device, narration is no more than a formation of unstable compromise. Strictly speaking, there is no such thing as narration: in the narrative, the performance unravels, formalizing itself as allegory; in the narrative, the stage is born, as a new matrix producing form and meaning. It is only by crushing the historical strata deposited in narrative and image (there's what comes from the Middle Ages, there's ancient and Gothic allegory, there's the inflection of Ariostian material to the use of Baroque opera...), that the literary critic succeeds in reasoning in terms of narrative and narratology.

.

Roger dans les bras d'Alcine : l'image comme théâtralisation du texte

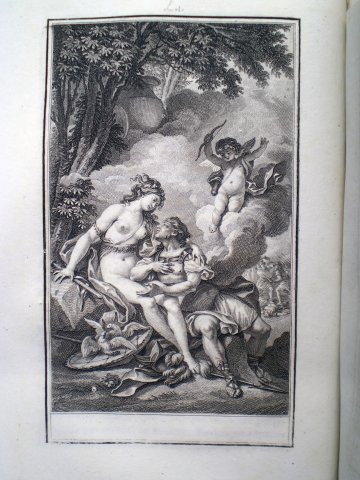

Sixteenth-century engravings hardly illustrate the interior of Alcine 's palace: the game of secrets in the ear by which the magician and Roger confide their love to each other (see the painting by Manetti or the engraving after Cochin), festivities, moments of amorous intimacy are, on the contrary, privileged material for painting and illustration as early as the seventeenth century.

The representation of the couple formed by Roger and Alcine tends in the eighteenth century to constitute an undifferentiated iconographic topos, which is confused with other famous couples : the confusion with Renaud and Armide is further explained by the fact that Tasso, in imagining the episode in Canto XVI of La Jérusalem délivrée, was directly inspired by the chant VII du Roland furieux. But what about Mars and Venus, or even Venus and Adonis ? Baroque mythological painting, ballet and opera gradually blended and homogenized these mythological, epic and novelistic materials of diverse origins to form a common syncretic culture. All that remains of these diverse origins is a common visual device, for which missing elements sometimes have to be made up. Here, the common feature of these embracing couples is the inversion of sexual attributes: the fairy, the goddess, dominates her companion and takes the initiative in the gesture; the enamored young man, on the other hand, is feminized, both in his clothing and in his posture. Charles and Ubalde spy on Renaud in Armide's gardens (see, for example, the painting by the Dominiquin, or the one by Boucher); Mélisse spies on Roger resting by a stream; Apollo spies on the lovemaking of Mars and Venus, which he will then report to /// Vulcan her husband. But this intrusion is not always explicitly represented, with the viewer sometimes playing the role of the ambushed voyeur alone, as in the Roger and Alcine after Moreau the Younger, or the Mars and Venus after Boucher.

But the most striking, and perhaps also the most personal, evocation of Roger and Alcine's lovemaking is Fragonard's drawings, which break down all the stages of the seduction: the public, collective pleasures of theater and dance; the semi-public pleasures of playing secrets by ear; Roger's departure for his room, almost backwards; and finally the passionate, nocturnal embrace.

Fragonard makes virtuoso use of the possibilities offered by the stage set: instead of wisely arranging the main characters and the action in the restricted space, then confining the vague space to the set, he organizes a shift, a dramatic tension between the play, the presence of the protagonists at the edge of the two spaces and the vacancy of the restricted space. This shift in space also corresponds to a shift in the choice of the moment to be represented, not the paroxysmal moment when everything comes to an end, but the pregnant moment, when nothing is yet played out.

This play on the edge of the two spaces heralds the crisis of the scenic device and the end of the pre-eminence of perspective and the geometrical organization of space in the implementation of iconic devices. In Tiepolo's Renaud et Armide in Chicago, the restricted space is identified with Armide's own dress, which defies all the laws of perspective and inscribes her one-legged body in a mandorla borrowed from medieval Christian iconography, while the classical screen traditionally articulating scenic devices - in this case, the low wall concealing Charles and Ubalde - becomes a laughable accessory, no longer allowing the gaze to break through. All the dramatic tension is concentrated on Renaud, at once caught in the space of the dress and drawn out of it.

///

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Le Roland furieux de l’Arioste : littérature, illustration, peinture (XVIe-XIXe siècles) », cours donné au département d’histoire de l’art de l'université de Toulouse-Le Mirail, 2003-2006.

Arioste

Archive mise à jour depuis 2003

Arioste

Découvrir l'Arioste

Épisodes célèbres du Roland furieux

L'île d'Alcine

Angélique au rocher

Bradamante et les peintures

La folie de Roland

Angélique et Médor

Editions illustrées et gravures

Principales éditions de l ’Arioste

Les trois territoires de la fiction

L’effet Argo

Gravures performatives

Gravures narratives

Gravures scéniques