Orlando Furioso's Cantos XXXII and XXXIII are built around a very special space: the Castle of La Roche Tristan. In Canto XXXII, this castle calls into question the rules of chivalric and courtly hospitality; on the other hand, the paintings it contains, which are the subject of a long description in Canto XXXIII, are the pretext for Ariosto's vigorous outburst against the French invasions of Italy and against war in general.

In many ways, then, this castle is an anti-castle. In fact, in Canto XXXII, under the guise of recounting a very old medieval custom dating back to Tristan, Ariosto imagines delirious rules of hospitality for the castle. Instead of the sacred principle of welcoming and protecting visitors, he substitutes a system of expulsion where only the law of the strongest prevails. The performance of the banquet, which identifies the representation of the medieval castle with the celebration of the knightly community gathered together, is thus systematically prevented, destroyed.

In Canto XXXIII, the description of the prophetic paintings created by Merlin on the walls of the banquet hall enables Ariosto to draw up a veritable indictment, not only of Francis I's imperialist France, but of the injustice and futility of war in general : after courtly values, it's agonistic values that are here clearly denounced in the name of humanism. After the performance of the banquet, it's the performance of combat that becomes impossible and loses all meaning.

The castle thus crystallizes the humanist deconstruction of medieval values and performances.

Canto XXXII

For Canto XXXII, both Valgrisi and Franceschi offer engravings based on the opposition of castles. Three castles are set against each other: the fortress of Arles in the foreground, where Brunel is castrated; the fortress of Montauban in the background, where Bradamante receives disturbing news from Roger through a Gascon knight; and the castle of La Roche Tristan in the background, where the interrupted banquet is depicted. In Arles, medieval law is exercised, but to punish, not to celebrate; in Montauban, the law is suspended : Roger is absent, Bradamante waits, nothing happens; at La Roche-Tristan, finally, the law is re-established, but a parodic, ridiculous law.

The Valvassori edition and the Nucio d'Anvers edition privilege Bradamante's fight at the castle gates. The semiological model of the performance, of the agonistic confrontation, is obvious, but it is somehow crossed out, erased by the rain: the trivial detail deconstructs the performance. In the Antwerp engraving, Bradamante no longer even has an opponent to overcome. She stands, lance raised, facing a horse whose rider has emptied the pommels.

In the eighteenth century, the ideological stakes of chant XXXII are no longer understood. In the Brunet edition, Monnet draws a detail /// the moment when a shepherd tells Bradamante how to get to the Château de la Roche Tristan. It is the narrative journey, Bradamante's journey, that seems important to represent the narrative is no longer the pretext for tying the performances together it becomes the fundamental issue of the story. Cochin represents Bradamante as she pleads for Ulanie, whom the castle's laws should expel. Ulanie's spite is a psychological detail absent from Ariosto, who transforms the problem of the banquet celebration into a scene of gender and manners, a family dispute à la Greuze : Doesn't Le Fils ingrat stage an expulsion of sorts ?

Canto XXXIII

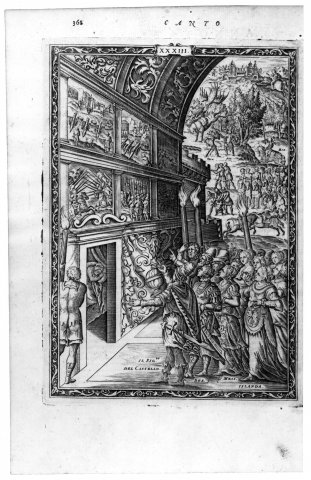

For Canto XXXIII, the Valgrisi and Franceschi editions favor the depiction of Merlin's paintings, explained to Bradamante and Ulanie by the lord of the castle. In the Valgrisi edition, the painting gallery is still depicted from the outside, but already occupies between a third and a half of the engraving (see engraving) in the Franceschi edition, the gallery is depicted from within, the reader-spectator is assumed to be breaking into the castle the gallery occupies three-quarters of the engraving, all the other episodes of the song being squeezed into a kind of window landscape, which can already be considered the vague space of a scenic device.

In all the other 16th-century editions, the chivalric exploits occupy a more prominent place, and the display of paintings is downplayed, despite the insistence of the text, which presents this gigantic ekphrasis both as a tour de force by the poet and as the highlight of Merlin's wonders. In the Nucio d'Anvers edition and in the Rampazetto edition, the paintings are absent altogether it's Roger's deeds at the Senape that are favored. This trend is accentuated in the eighteenth-century editions, where the harpies are deemed decidedly more picturesque. Closer to the Valgrisi edition, the Valvassori edition contrasts a right half of the engraving dedicated to the paintings and a left half dedicated to the battles.

The setting of the lord of the Château de la Roche Tristan describing the paintings in his banqueting hall to his guests had, however, enough to excite the engravers' imagination, since it represented precisely the articulation between text and image, on which every book illustration works. Through this ekphrasis, Ariosto brought the image into his text, just as, through engravings, draftsmen brought the text into their images. The ekphrasis was an obligatory part of epic writing : Homer had described Achilles' shield in the Iliad ; Virgil, Aeneas' in the Aeneid. It is in this capacity that Ariosto embarks on the virtuoso exercise of Canto XXXIII. But early engravers reduced their illustrations to the conventional codes of chivalric performance; as for more recent engravers, they only wanted to retain the marvel of the oriental tale, the monsters and wonders of Ethiopia. The specificity of Canto XXXIII is lost. Only in the brief interval around the turn of the century will the two editions by Valgrisi and ranceschi have grasped the essential semiological stakes of this chant XXXIII.

... about the Senape, also known as the " priest John "

The priest John is the name of a Christian priest-king. /// mythical medieval ruler of a vast empire located first in Central Asia, then later in Ethiopia. He first appears in the Chronicle of Otto of Fresingen, who is said to have heard of a powerful Christian ruler in the East in 1145 from a Syrian bishop who came to the pope's court in Viterbo. In 1177, Pope Alexander III wrote a letter to " presbyter Iohannes ", hoping to make him an ally of European princes in their fight against Islam in the Mediterranean. At the time, the priest John was believed to be the ruler of an Asian country near India.

During the Fifth Crusade, in the early 13th century, the Crusaders gathered information about Ethiopia in Egypt. This is how the Christian rulers of Nubia and Ethiopia, fighting to defend their faith, became known in Europe. The priest John of India, whose legend was older, was then identified with the emperors of Ethiopia, probably because in Europe India and Ethiopia were often confused. Until the Renaissance, it was believed that only a thin strait separated Ethiopia from the Indian subcontinent.

In 15th-century documents, the priest John takes the name At Senab, which is a corruption of the Arabic Abd as-Salib, an Egyptian translation of the Ethiopian Gäbrä-Mäsqäl, the servant of the cross, the official title of some Ethiopian emperors, notably Amda-Seyon I (1314-1344).

In the 16th century, the Senape appears not only in Ariosto. In Tasso's Gerusalemme liberata, Clorinda is the Senape's daughter: a warrior heroine, she receives baptism from her lover Tancrède, who mortally wounded her in battle without recognizing her, before dying in his arms.

(after Enrico Cerulli)

Arioste

Archive mise à jour depuis 2003

Arioste

Découvrir l'Arioste

Épisodes célèbres du Roland furieux

L'île d'Alcine

Angélique au rocher

Bradamante et les peintures

La folie de Roland

Angélique et Médor

Editions illustrées et gravures

Principales éditions de l ’Arioste

Les trois territoires de la fiction

L’effet Argo

Gravures performatives

Gravures narratives

Gravures scéniques