Aside from the three Ferrarese editions that mark the constitution of the text of Roland furieux (1516, 1521, 1532) other editions appeared in the intervening years, in Milan (1524) and, above all, Venice (1526, 1527, 1531). The abundance of these editions attests to the immense success of the book, which enabled publishers to embark on the commercial adventure of their illustration.

The first vignettes, engraved on wood, occupy half a page this is the case of the Giolito de Ferrari edition, in-8°, Venice, 1549, reprinted by Nucio in Antwerp in 1558, and the Valvassori edition, in-4°, 1566, and Rampazetto of 1570, both Venetian. Small engravings, dependent on Gothic illumination which they crudely imitate, these early images privilege the agon of chivalry, confrontation or reconciliation, combat or banquet. In 1556, the Valgrisi edition1 for the first time featured woodcuts occupying the full page of an in-4° (or large in-8° ?) volume. This edition, whose images are said to have been drawn by Dosso Dossi, painter and friend of Ariosto, was a runaway success, as evidenced by its numerous reprints between 1558 and 15802. In the space freed up by the full page, the characters swarm, despite the difficulty of woodworking : the purity of the epic agon gives way to the meandering narrative. Finally, the Franceschi edition of 15843 introduces a decisive technical innovation : this time it features copper engravings, strongly inspired by those of the Valgrisi edition and signed by a great name in engraving, Girolamo Porro (1520-1604), who had made a name for himself as a cartographer by illustrating L'isole piu famose del mondo by Thomaso Porcacchi (1572, 1575, 1590, 1604). Himself a commentator and editor of Ariosto, Porcacchi may have been the initiator, if not the commissioner, of G. Porro for this exceptional series.

For the novelty is not only technical : Girolamo Porro rationalizes the narrative space of these engravings teeming with characters. What in the Valgrisi edition constituted an almost exhaustive visual summary of the events of each song is organized in the Franceschi edition around a single episode, taken from a single perspective and tending to constitute, theatrically, a scene. It's a revolution with no turning back: after the near illustrative eclipse of the seventeenth century4, the great illustrated editions of Ariosto in the eighteenth century will only depict scenes from novels5.

This semiological shift, from the Valgrisi edition to the Franceschi edition, marks a decisive step in the constitution of the modern novel. It deconstructs medieval performance and consecrates the assumption of the stage. But there can be no stage without the strong implementation and promotion of a performance space. This space was first constituted from an imaginary geography: cartographic geography first, then spectacular topography. Between performance and stage, a geographic moment opens up in the history of novelistic representation. This geographical moment is vividly manifested in the illustration. But it was, in a way, structurally programmed by the text, each song being ordered from a territorial structure that comes to be superimposed on an outdated narrative structure.

However, despite the wealth of theatrical works it has nourished and influenced, the Roland furieux, paradoxically, does not obey an economy of the stage : the latter has been constituted from it, but outside it. The imaginary geography of the Roland /// furious is constantly turned on its head, contradicted by an antagonistic imaginary of invisibility. Between cartographic hypervisibility and the invisibility of fictional vortexes, the Ariostian narrative is constituted as a device.

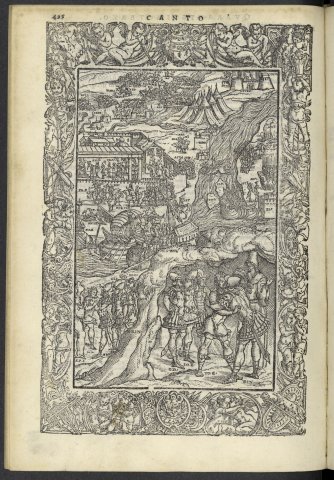

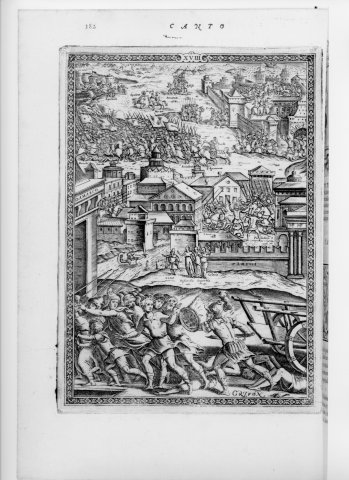

To develop our argument, we'll start with four engravings from the Valgrisi edition, where the cartographic dimension of the image is particularly strikingly expressed : these are the engravings from chants XV, XVIII, XX and XLIV6.

The geographical moment

At first glance, the engraving of Canto XLIV seems particularly confusing, not only because it obeys compositional codes that are baffling to the modern reader, but also because it follows a particularly tight sequence of events as closely as possible. Beyond the difficulty of deciphering, however, the cartographic dissemination of the image is characteristic of an organization of the narrative based on what we have defined, between performance and scene, as a geographical moment.

Lower right, in the cave of the hermit who welcomed them, Renaud de Montauban embraces Roger, his future brother-in-law, who has just been converted to Christianity7. The embrace under the auspices of the hermit represents the result of his speech: he has persuaded Renaud to accept the union of his sister Bradamante with Roger. On the left, Olivier, Sobrin and Roland8 approve this project.

The episode is circumscribed by a rocky hemline that delimits the hermit's cella, where the text sets the scene (stanza 14). It is preceded on the left by the knights' arrival on the hermit's island(canto XLIII, st. 190). Sobrin, seeing the effect of the hermit's blessing on Olivier, who emerges miraculously cured(canto XLIII, st. 179), then asks for baptism : he is depicted to the right of the hermit, unarmed, arms crossed over his chest. No abbreviation indicates his name, perhaps because the performance consists precisely, through baptism, in giving him one9.

In the center of the engraving, we see the knights leaving the island. They climb onto their boat via a small wooden gangway10. The boat is depicted three times from right to left, setting sail from the hermit's island, then at sea, then arriving in sight of Marseille (MAR11) The narrative movement then prevails over the performance : the engraver omits the hermit blessing the knights as they depart.

Meanwhile, on the right, Astolphe (AST), at the gates of Bizerte (BIS), a Tunisian port he has just victoriously besieged, bids farewell to his ally the Senapes (R. NU. : " il re de' Nubi ", st. 19) and gives him the austral wind enclosed in a wineskin to take away (st. 21-22). Below, " the fleet that defeated the pagans on the waters " encamps before the walls of Bizerte : Astolphe will transform it into a forest that will dissipate in the air (st. 20). Above, /// still on the right, the Nubians' horses, turned back in front of the Atlas defiles (ATLA), become rocks again (st. 23).

To the left of Bizerte, towards the center of the engraving, Astolphe (AST.) mounted on his hippogriff, flies to Sardinia (SAR.) then Corsica (COR., st. 24); he arrives in Provence, frees the hippogriff and joins Renaud, Roland, Sobrin, Roger and Olivier in Marseille (MAR, completely left)12. The middle part of the engraving is therefore mainly occupied by Astolphe's itinerary, represented seven times: Astolphe travels the entire width of the engraving from right to left to get from Bizerte to Marseille, then half the width from left to right to get from Marseille to the gates of Paris.

.In the text, Charlemagne comes to meet the knights " sopra la Sonna ", on the banks of the Saône (st. 28). Here we see him under the two columns of his Parisian palace (CAR.) accompanied by his wife Galerane (GAL.), in front of the walls of Paris (PARI.), facing the knights gathered on the left. On the right, Marphise (M.) embraces her brother Roger (RVG.) and Bradamante (B.) joins him and Astolphe (AST., st. 30).

A little higher up, and further to the right, the troop enters the city in triumph : Charlemagne in the lead (CAR.), accompanied by Roger (RV) flank to flank (st. 31), then Roland and Renaud (OR. above, RI. below) have already passed through the gates, while Astolphe, Sobrin and Olivier are still crowding outside (AST. and SOB. above, OLI below). Parisians throw flowers from their windows (st. 32).

On the left, in the imperial palace, before Charles (C.) seated on his throne on the far left, Renaud (RI.) explains to his hardly pleased father Aymon (AMO.) that he has given his sister Bradamante (BRA.) to Roger (st. 35-36). Further to the right, Aymon's wife Beatrice (BEA.) has a stormy discussion with Bradamante (BRA., st. 37-39). At this point, the text dwells on Bradamante's despair (st.40-47), then Roger's (st.48-59), whom Bradamante reassures (st.60-67): there is no equivalent in the engraving, which, leaving aside the states of mind, moves on to stanza 68. Bradamante then asks Charles (CA.), seen between her (BRA.) and Roger (RV.) on the right in the palace, to intervene: she wishes that her future husband should first measure himself against her by arms. If he is defeated, let him seek a companion elsewhere (st.70). Once again, the illustration emphasizes the demand for performance. Charlemagne accepts the ordeal requested by Bradamante, but Aymon and Béatrice then resort to trickery: they take Bradamante to Rochefort (BEA., BRA., AMO. for " Amone ", R. FOR. for " Roccaforte " st. 72), which the engraving, in keeping with the text13, locates... between Perpignan to the south and Carcassonne to the north!

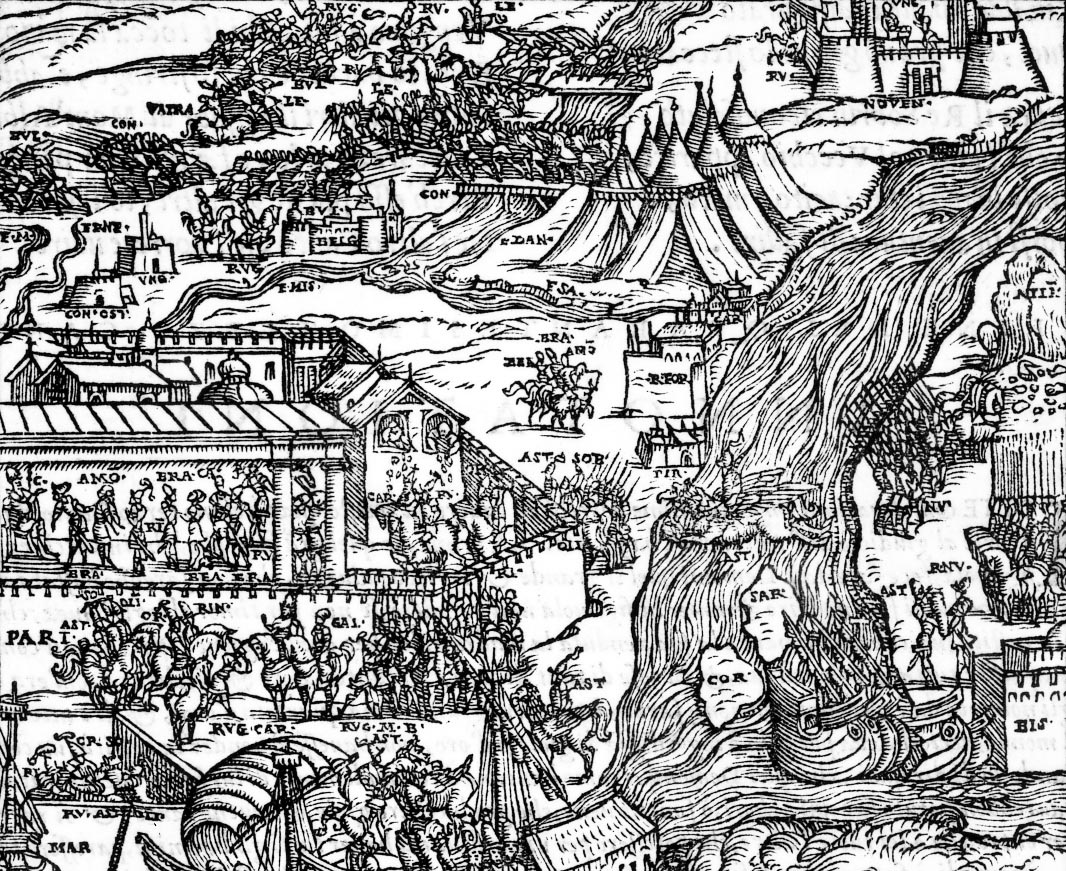

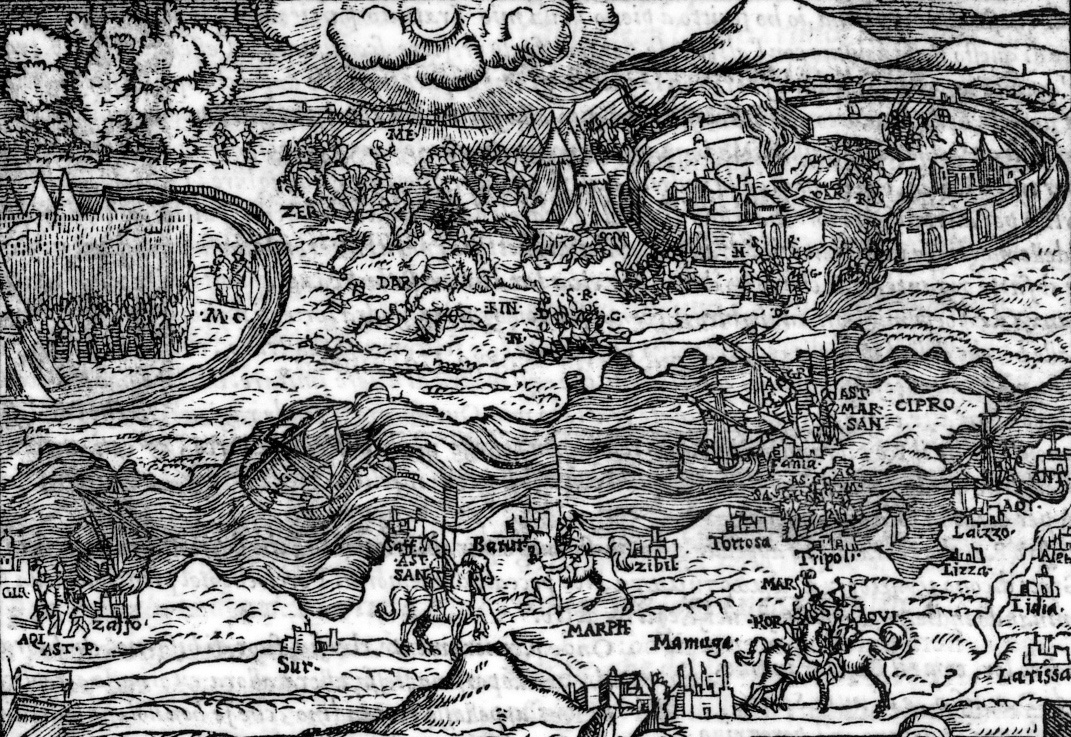

Understanding that Bradamante has been kidnapped, Roger crosses the Meuse and Rhine, passes from the Austrian lands into Hungary, follows the Danube along its right bank and rides so far and so fast that he arrives in Belgrade (st. 78). On the engraving, above Paris, from left to right, are the Meuse (F. M. and later, by mistake, F. MIS. for " Fiume Mosa "), the Rhine (F RNE in error for " Fiume Reno "), then two market towns (CON'OST and VNG, " contrade d'Osterriche14 " and " Ungheria "), finally the citadel of /// Belgrade (BELG). Roger is shown arriving on horseback in front of Belgrade, accompanied, as the text indicates, by his only and most faithful squire.

Above Belgrade, which it is supposed to occupy, the Bulgarian army (BVL) is trying to contain the advance of Constantine (CON), emperor of the Greeks, who has just, on the right, thrown a bridge over the Danube (F DAN for " Fiume Danubio ", st. 80). On the other bank, the tents of the Greeks are set up at the junction of the Danube and Save rivers (F. SA. for " Fiume Sava ", st. 79). Above, Constantine's son Leon (LE.) distracts and, further left, kills the Bulgarian king, Vatran (VATRA., st. 83). Completely to the left, and further down, the Bulgarians, baffled by the death of their leader, turn around and flee (st. 84)15.High above Belgrade, Roger rescues the routed Bulgarians out of hatred for Leon, the rival Aymon has destined for his daughter Bradamante: the Bulgarians regain the upper hand. Roger first arrives mingled with the Greeks (RV, st. 84), lowers his spear to charge a nephew of Constantine (RV, st. 85-86), then draws the sword Balisarde (RVG., st. 87) finally he calls Leon without seeing him (RV, st. 93).

Meanwhile, Léon (LE) mounted on a mound can't help admiring Roger (st. 89-93). His overhanging position allows him to see without being seen, and to take in the whole battle scene: the scenic device here takes precedence over the performance. Leon sounds the retreat and the Greeks cross the Danube in the opposite direction, on the upper bridge (st.94). Leaving the Bulgarians behind, Roger pursues Leon. At the top right, he arrives in the city of Novigrad (NOVEN. for " Novengrado ") where, in the next song, he will be taken prisoner (XLV, 10).

The overall composition of the engraving clearly reveals three territories, bounded by the sea: below, the hermit's island constitutes the territory of chivalric performance (st. 1-18). The hermit converts, baptizes and reconciles. His island embodies the ancient values : faith, loyalty, friendship.

Top right, the second territory is Africa. Astolphe is victorious, but leaves (st. 19-26)16. This territory, temporarily acquired by the Christians, remains that of the Infidels, and Astolphe's victory " was bloody and joyless " (st. 19). This precariousness is represented by the winds, modelled on the episode of Ulysses and Aeolus in the Odyssey (Canto X, st. 20-26), as well as by the prodigy of horses turned to stone. Magic and the unleashing of the elements are the prerogative of these places of uncertainty and reversals.

The third territory, top left, is the most densely populated with figures: this is where all the narrative activity of Canto XLIV, centered on the quarrel over Bradamante's marriage, is devoted. Marseilles, Paris and Belgrade are brutally superimposed, with Austria and Hungary constituting two castles, while the Meuse flows unhappily into the Danube just outside Belgrade. The fictional territory concentrates the narrative and reorganizes the geography of places into a theatrical topography: in front, the scene of conflict is Charlemagne's court in Paris, where Renaud, Roger and Bradamante, on the one hand, and Aymon and Beatrice, on the other, are tearing each other apart. Behind the scenes, Roger fights to eliminate his rival, Léon le Grec. This third territory contrasts the feudal economy of performance (below) with the mercantile economy of the stage: on the stage of Charles's court, and behind the scenes, the exchange of Bradamante is monetized. Thus repeats the primitive scene from Roland furieux, the bounty on Angélique, between Renaud and Roland, under Charles's control (canto I, st. 9).

At top right, Roger crosses /// Novigrad is depicted above Bizerte, and Roger crosses the Danube symmetrically with Astolphe crossing the Mediterranean. In this way, Novigrad repeats the territory of uncertainty, betrayal and the negation of values, across the river just as Africa is located across the sea. According to the symbolic logic of territories manifested in the engraving, Novigrad is in some way situated in Africa...

The imaginary geography of the narrative locations proceeds by distortions of real geography. Here, it's not a question of inventing fabulous kingdoms, of creating allegorical islands (as, for example, in Canto VI, with Alcine's island), but rather of recomposing the world map to make it coincide with a symbolic narrative topography.

The imaginary geography of narrative locations proceeds by distorting real geography.

The hermit's island is both an enclosed field, where the knightly embrace is celebrated, and a stage to which one arrives and from which one departs, between two journeys. It is a symbolic and cartographic island. For the engraver, it's not a question of geometrically organizing a space where the edge of a coastline or port circumscribes the cell, the hermit's entrenched cave, where an outside is articulated to an inside. The performative inside of the embrace (which the Valvassori edition retains almost exclusively for the island) is brutally superimposed on the narrative outside of the voyage (favored by the Franceschi edition), by means of a rocky border of theatrical pasteboard that seems to extend the river border of the Mediterranean.

.Higher up, between Tunisia and Provence, the Mediterranean arm comprises only Corsica and Sardinia, with no Italy : the narrative meander is reduced to the simplest. It disappears completely in Girolamo Porro's engraving, which places the only French towns on the horizon of the hermit's island in perspective.

.The geography of fiction goes through the steamroller of scenic unification : Paris advances into Provence to meet the knights freshly landed in Marseille. The city, unnamed in the text, is located on the banks of the Saône (st. 28) : for the illustrator, this city can only be Paris, conventionally designated in the Roland furieux as Charlemagne's besieged capital. Rochefort, probably Rochefort-du-Gard, is set by the sea, between Carcassonne in the Aude and Perpignan in the eastern Pyrenees, not because it's actually a port, but because, in the story, Bradamante's imprisonment is a narrative terminus.

.Finally, the rivers, top left, grid the space according to an aberrant geography : the Meuse, the Sava and the Danube converge before Belgrade the Sava rises or flows into the Mediterranean. These topographical aberrations are symbolically motivated. On the vertical axis, the Danube, parallel to the Mediterranean, repeats the same boundary between places of valorization and glorification (Paris and Belgrade celebrating Roger's triumph) and places of defeat and betrayal (Novigrad and Bizerte). On the horizontal axis, the Meuse and Save rivers mark the boundary between the stage below, Charlemagne's court, and the off-stage above, the backstage realities of the Bulgarian-Greek war.

.Territorial structure of song

This tripartition of the performance space is recurrent in the engravings of the Valgrisi edition. It's not just a technique for composing the narrative image it interprets the text and reveals the device of its narrative, masked by the broken, tangled lines of its narrative proliferation. The three abstract levels of the Ariostian narrative device (chivalric performance, symbolic reversal, novel scene) correspond to the three territories of the engraving, which are also the three fictional worlds that the narrative traverses each time.

.Or, this correspondence constitutes a logical aberration: /// While the levels of the device are concomitant (the performance revolves continuously on stage), the territories of engraving as well as the worlds of fiction are supposed to appear successively in the narrative and to be arranged separately in the cartographic space of song. Geometrical (or narrative) succession and semiological superposition seem irreconcilable.

We propose to show, using a few examples, how this aberration is expressed, based on a tripartite territorial structure as imperturbably recurrent as it is irreducible to any narrative logic.

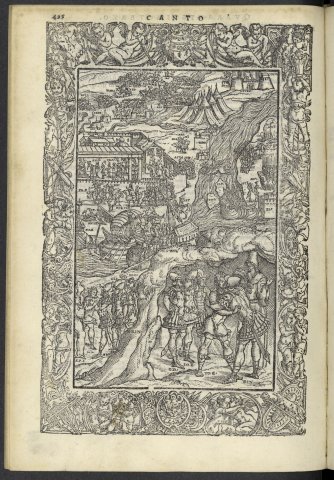

Chant XV opens with Agramant, king of Africa and leader of the expedition against Charlemagne, storming the gates of Paris. This assault occupies the base of the engraving, with Agramant's name clearly visible on the shield of the leading warrior (AGRA.). The agonistic face-off constitutes the first territory, on the model of chivalric performance, pitting the Moorish swords against the tips of the Christian spears emerging from the gate17.

At mid-height, on the right, rises the palace of Logistille, with its hanging garden above. Logistille (LO.) gives a book of enchantments and a magic horn to Astolphe (AS.), who is about to set sail (st. 13-14)18. The castle of Logistille, the fairy of rationality, appears as a tower and is a sort of background replica of the Porte de Paris, where war is raging. Although no territorial break is marked on the ground between the foreground and background, this play of replicas between the two towers differentiates the second territory of engraving and song, where allegory and enchantment reign.

On top, the third territory, separated from the previous two by the Indian Ocean, is that of the map, where the elements of the narrative are arranged on the regions of the world : the ground is treated differently, in the manner of a map ground, smooth and abstract, with stylized reliefs, and in contrast to the lumpy, stony asperities of the lower engraving. From right to left, Astolphe skirts India (INDIA) and the mouth of the Ganges (GANGI. Fl, st. 16-17), Persia (PERSIA) and the Persian Gulf (erroneously noted M. PON. for " mare ponticum " : the Black Sea, st. 37), then overland through Arabia (ARABIA) to the Red Sea (MAR. ROS., st. 39). He rides along the Trajan Canal (F. TRA., st. 40), which links the Red Sea to the Nile (NILO. F., st. 41)19. There he meets a hermit on a boat (st. 41-42).

From this meeting point, the narrative line moves back across the engraving from left to right to unfold Astolphe's battles with Caligorant (CAL.)20, then against Orrile (HORR.21). This third territory, where the narrative spirals out of control and episodes multiply as at the end of Canto XLIV, appears in the overall composition as a backdrop22, framed by Charles and Logistille's porte-coulisses, and separated from them by the Indian Ocean. Astolphe, who is about to leave Logistille's, will turn to him, arrange himself, by /// spectator, facing him. The cartography is thus ready to tip over into scenography.

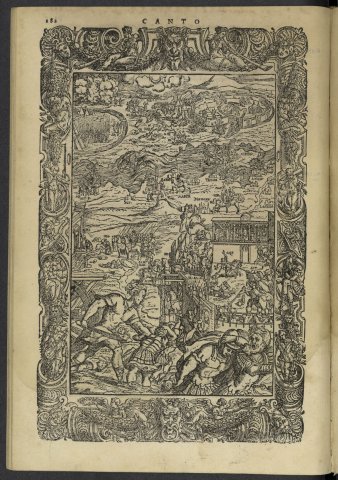

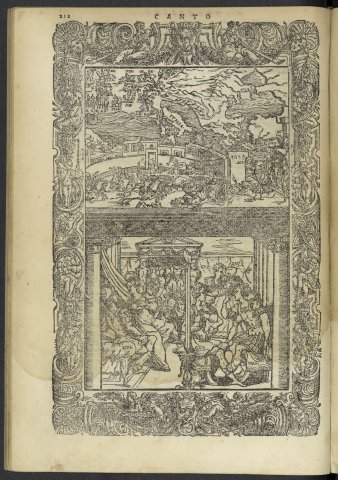

In the illustration of Canto XVIII, the distortion between the narrative succession of the text and the system of territories exploited by the engraving is even more striking. As is customary in narrative engravings, the bottom of the image is occupied by the first episode of the text to be illustrated: here, Griffon (GRI.), victim of the scheming of his perfidious mistress Origile and her accomplice, the cowardly Martan, has been robbed of the prize for his victory in the Damascus tournament. Dragged on a cart of infamy, he managed to free himself on the outskirts of the city and, sword in hand, set about reclaiming his tarnished honor. In the engraving, the men who fall at his feet or flee are depicted, against history, as soldiers rather than bourgeois. In the text, the town's drawbridge is hastily raised, leaving the stragglers at Griffon's mercy. Yet Griffon's bravery must, visually, be exercised in battle, not in a suburban melee with unarmed people : the first territory is that of performance23.

A path delineates this territory on the left, so as to encompass, above the first episode, the arrival of Noradin, King of Damascus, and his reconciliation with Griffon, after the latter's fight at a temple gate. The path geographically links the temple, on the left, to the city, on the right, from which Noradin emerges. In the text, however, the episode of reconciliation only occurs in stanza 60, after a long detour by the narrator to Paris (stanzas 26-59), where Rodomont's ravages are fought with great difficulty by Charlemagne and his paladins. Paris, which once again becomes the scene of the narrative at the end of Canto XVIII, is depicted at top right, recognizable by its Île de la Cité.

Just as, in the engraving of chant XLIV, the hermit's island is divided into an exterior and an interior, into a narrative shoreline and a performative grotto, so here the territory of Damascus is divided between this exteriority, delimited by the gates where Griffon slaughters the men who humiliated him, and the interior of the city, surrounded by ramparts, where a second tournament is played out, after the tournament treacherously won by Martan. Like the hermit's cave, where the embrace seals the knights' friendship in song XLIV, like Paris where Charles and Agramant clash in song XV, the city of Damascus is in song XVIII the site of an endlessly reiterated and distorted performance, the medieval performance par excellence that is the tournament.

.Between Griffon's gesture and the second Damascus tournament, Noradin's exit from the city to take the frontier path to meet Griffon acts as an interface : he emerges spatially from the ramparts, but not temporally, since the tournament represented in Damascus won't come until well after this exit. The territory is a space-time, a mixed chronotope, where heterogeneous narrative temporalities aggregate: the drawbridge where Noradin stands does not correspond to a door Noradin literally emerges from the wall.

Noradin therefore organizes a tournament in Griffon's honor, to make up for his misunderstanding and the infamy of the cart. Renommée, represented by a figure flying over Damascus, announces the event throughout Palestine (st. 96-97). Sansonnet (SAN), Marphise (MAR) and Astolphe (AST) arrive at the gates of Damascus to take part in the tournament (st. 103). They are greeted by Noradin (NO), whose horse is this time drawn on either side of the wall24. But the tournament triggers a scandal: Marphise recognizes in her prize the weapons stolen from her in Armenia. Astolphe and Sansonnet take up the cause of the horsewoman, who routs her opponents and reclaims her weapons (st. 119).

Above Damascus, but below the Mediterranean Sea, the second territory25 is organized around a transverse road, through which we follow Aquilant's journey in search of his brother Griffon, before the second Damascus tournament. We therefore have to go backwards in the text, as well as in the narrative succession of the story, contrary to the ordinary rules of composition and reading of narrative images: the geographical layout of the places conflicts with the unfolding of events and imposes this distortion. But, above all, the bipolar space of the first territory, where the performance breaks up, split in two by the Damascus wall and opposing Griffon's gesture on the left to Marphise's gesture on the right, is succeeded by a territory reunited by the narrative route that runs along the southern shore of the Mediterranean.

.

In Jerusalem (GIR, far left), a Greek pilgrim (P) informs Aquilant26 (st. 70-72), who embarks at Jaffa (Zaffo, st. 73) :

The land of Tyre, the next day,

He sees it and Sarepta, one right after the other.

He passes Beirut and the Jebaïl, and understands

That on his left hand, Cyprus stretches its coasts into the distance.

To Tortosa from Tripoli and Latakieh

And to the Gulf of Alexandrette he directs his path27 (st. 74).

After Aquilant's landing at Antioch (ANT, st. 75), we follow his overland route to Aleppo (Aleh for " Aleppe "), Lydda (Lidia) and Larisse (Larissa)28. Before Mamuga, he meets Martan accompanied by Origile (MAR and HOR, st.77). After a tough interrogation, the two traitors are led by Aquilant to Damascus: we see them below between the city walls and the tournament liceum (H.M.A., st. 87-90).

Like Astolphe passing from Bizerte to Marseilles in Canto XLIV, or from the château de Logistille to Egypt after crossing the entire Orient in Canto XV, Aquilant occupies the second territory of Canto XVIII with his enormous, tireless route : fiction becomes globalized at the moment when values unravel, after the reversal of performance in the first territory, and as lies and treachery unfold in the speeches of the deceitful Martan and his damned soul Origile.

At the very top, finally, north of the Mediterranean, the third territory opens up. The /// France is divided between two camps on the right, Paris and, in front of the city, the tents of the Christian camp on the left, surrounded by a moat, the Saracen camp, where Médor and Cloridan (M. C.) are preparing a spectacular night out (st.165-171) the aim is to recover the body of their leader Dardinel (DAR.), abandoned on the battlefield, and give him a burial. But Zerbin (ZER), on patrol for Charlemagne, appears and pursues the two Saracens with his companions, who are trying to take refuge in the forest above left (st. 192). Médor's gesture sketches out a symbolic refoundation of the epic : but it's the gesture of a simple soldier, a Moor, and one that, what's more, takes place at night this refoundation in no way constitutes a return to the performative origins of medieval fiction.

Because here, more than in any other song, the third territory reveals its scenographic potential: set against the enchanting moonlight, Cloridan and Médor's gesture becomes a tableau. Médor, unable to discern his captain in the horrible mix of corpses plunged into the night, begs the moon to illuminate him :

The moon at this prayer opened the nue

(whether it was chance or really the effect of such faith),

beautiful as she was as she offered herself

and, naked, threw herself into Endymion's arms.

With Paris in this light, one camp was discovered

, then the other&. one camp, then the other ; and mountain and plain became visible ;

we also saw the two hills in the distance :

Montmartre on one hand and Montlhéry on the other.

His light shone even more brightly

where d'Aumont's dead son lay.

Médor went, weeping, to his dear lord,

whose ruddy white shield he recognized;

and all his face he bathed in a bitter

of which he had a stream under every eyelash,

in gestures so gentle, in complaints so sweet

that the winds would have stopped to listen29.

The engraving describes this panoramic nocturnal landscape as closely as possible, illuminated in the center by a crescent moon peeking through the clouds30. The narration successively illuminates the walls of Paris, then the Christian camp set up in front of the City, then the Saracen camp, then the more distant landscape, before focusing on Dardinel's body : this is the scene chosen by Moreau le jeune to illustrate the Brunet edition of 1776.

.But in the Valgrisi edition, the cartographic landscape for a moment unfurled and arrested is traversed by the irrepressible movement of the narrative. Dardinel is first depicted in the center, struck down by Renaud (DAR and RIN, st. 153), then, above, crushed beneath his horse, he is discovered by Médor praying under the moon (st. 186) ; finally, on the left, Médor, who is carrying him on his back, seeks to reach the forest to escape Zerbin and his riders (ZER, st. 188-192).

A final example of this structural tripartition in the engravings of the Valgrisi edition. /// The illustration in canto XX depicts the hospitality given by Guidon to Marphise in the Amazon-held town of Alexandrette. Like Renaud's embrace with Roger (canticle XLIV), Agramant's assault on Paris (canticle XV) or Griffon's fury in Damascus (canticle XVIII), Guidon's hospitality celebrates the values of chivalry. On the left, Guidon persuades one of his wives, Aléria (ALE.), to betray the Amazons, allowing them to escape. As in the engravings of chants XLIV, XV and XVIII, this first territory itself breaks down into an inside and an outside : on the right, the public space of the banquet is the place of recognitions (of the warrior as Marphise, of Astolphe as Guidon's cousin) on the left, the private space of the bedroom prepares the plot : the bedroom is the anti-performative space of the narrative weave, where the rouerie is woven.

The second territory is the town of Alexandrette itself, identified with an arena. The scheduled battle between Guidon and Marphise turns into a rout of the Amazons thanks to Astolphe's horn and, in flight, thanks to the boat prepared by Aléria (st. 95). As in Chants XV and XLIV, the second territory is crossed from left to right by a sea voyage, no longer a blind adventure marked by randomness, but a concerted journey that can be traced on a world map: its course prepares the shift from representation to panoramic fiction, and then to scenic fiction. The cartographic regulation of the route replaces the performative regulation of events. Like the second Tournament of Damascus in Canto XVIII, the Amazons' regulated and indefinitely revived joust tips over into cunning, betrayal and flight : the second territory is one of reversed values and symbolic instability.

.The upper part of the image, finally, unfurls a magnificent map of the Mediterranean, where the illustrator has arranged the journey of Marphise and her companions, then, on the left, her encounter with old Gabrine (L.) and her victory over Pinabel (PIN., st. 111-115), then over Zerbin (ZER., st. 117sq.), to whom finally falls the charge of transporting the perfidious old woman. Top center, Marphise disappears into a forest, like Cloridan at the end of Canto XVIII. Gabrine's presence parasitizes the chivalric gesture, without any clear stage reconfiguration taking shape. Although the stage reconfiguration is not visible in the engraving, it is nevertheless perceptible in the text. The narrative game of substitutions that passes Gabrine from hand to hand gradually depreciates the agon of chivalry in favor of the burlesque effect produced by the old woman at the side of the knight required to accompany her (st. 113, 116, 119-120, 128, 132-133) : Gabrine becomes a tableau, and this grotesque spectacle perverts, competes with the performative effectiveness of combat.

Fictional device of Roland furieux

This tripartite structuring of the engravings in the Valgrisi edition (performance /tipping /stage) cannot be reduced to an illustrator's device. It interprets in depth the writing of Roland furieux and constitutes an informed reading of it, all the more relevant if the illustrator was Dosso Dossi, friend of Ariosto and perhaps a privileged witness to the poem's elaboration.

One immediately notices, when reading Roland furieux, the frequent narrative interruptions to change, on the fly, characters and place, often knowingly interrupting the action at its most thrilling moment. For example, in the opening stanzas of Canto XV, the battle is still raging outside the gate that Charlemagne himself is defending against the Saracens: the narrative still belongs to the sequence opened in the previous canto, centered on the siege of Paris.

It's not until the middle of stanza 9 that Ariosto suddenly pretends to remember that Astolphe's gesture, the central subject of canto XV, is to begin. It's time to move on from the real city /// from Paris to the allegorical island where the Logistille fairy arms Astolphe, Duke of England, in preparation for his future adventures:

The Logistille fairy arms Astolphe, Duke of England, in preparation for his future adventures.

Of this [battle] elsewhere I want to give you an account

for towards a great duke force me to look

who shouts at me and beckons from afar,

and begs me not to let go of my pen. It's time to go back to where I left

the adventurous the adventurous Astolphe d'Angleterre31.

While the narrator refers to his tale elsewhere in the narrative (" altrove io vo' rendervi conto "), the characters solicit it from the territories of their fiction : Astolphe beckons from afar (" di lontano accenna "), from one island to another, from which, for Ariosto, it's a matter of transport. The same transport in Canto XVIII, when we must once again leave the bloody Parisian battles for Griffon's grand gesture in Damascus :

But let enough be said for once

of the glorious deeds of the West.

It's time I returned to where I left Griffon32...

Even more casually, in Canto XLIV, as Roland and his companions dock at Marseille, about to be reunited with Charlemagne at last, Ariosto plants them in the harbor to find Astolphe :

But let them stay there as long as I lead

with them Astolphe, the glorious duke33.

Marseille is the location of the narrative seam, where our heroes will have to wait while the narrator brings the duke there from Bizerte, Africa34.

Ariosto was already practicing the technique of sequencing, with which soap operas have made us familiar he was not, however, its inventor. It is the narrative technique of the Gothic novel, with the difference that it is no longer the tale, but the person of the narrator who assumes its implementation. For example, in Lancelot du lac : " But in this place the tale speaks no more of Banin or Claudas or his company, and returns to King Ban, from whom it has long since fallen silent35. " The place of the text (" this place ") is well identified with the place of action where returns the tale, moving from one narrative territory to another. Again, in this territory the tale sticks to a linear progression : " The tale therefore sticks to its straight path and tells us that King Ban had a neighbor whose land bordered his on the Berry side which was then called the Terre-Déserte36. " To the straight path of the narrative corresponds the straight march of Claudas against Ban de Bénoïc, Lancelot's father.

This system, however, gets somewhat out of hand in Ariosto. Firstly, it doesn't coincide with the division of the songs, introducing a game, a tension between two forms of structuring the text : territorial, on the one hand, and poetic, on the other. Secondly, it's no longer simply a matter of moving from one place to another, circumscribed and often bordering places : fiction is globalized and presented as a mesh of a global map, as an occupation, literally speaking, geographic. It provides itself with the means for this global vision, notably with the hippogriff, which enables it to fly over territories (Atlant in canto IV, Roger in cantos VI, VIII and XI, Astolphe in canto XXIII), but also with overhanging allegorical figures, such as Renommée calling for the Damascus tournament in canto XVIII, Discord spreading through Agramant's camp in canto XXVII, /// or the chariot of Elijah on which Astolphe rides in song XXXIV. Fiction discovers the panorama.

It is through the interplay between the structure of territories and the structure of song on the one hand, through the globalizing movement of fiction which, by geographing itself, so to speak, tends towards a unified symbolic articulation, that the succession of a first territory of performance . is revealed for each song;- recalling the world, the values, but also the narrative mode from which we start -, a second territory of instability and tipping - where this world and these values are overturned, where this narrative mode is complicated to the extreme. Finally, the third territory is that of scenographic recomposition, where the new space-time of the novel scene takes shape, barely sketched out in Ariosto's text, but progressively hypertrophied in the later use made of Ariostan fiction ; the most famous scenes from Roland furieux in Baroque painting, opera and ballet37 belong to the third territory, and as such only give rise to tiny details in narrative engravings : Angélique au rocher rescued by Roger (chant X), Angélique et Médor dans la grotte de leurs amours (chant XIX), Roland discovering Médor's inscriptions that will drive him mad with amorous despair (chant XXIII).

But the geographical globalization of Ariostian fiction doesn't just constitute a system of territories articulated to the system of song. It opens fiction up to a new, pre-theatrical form of visibility: the fictional island, where, to use Frank Lestringant's formula, the archipelago of fiction38 unfolds as an ideal map, certainly, but also as a landscape. Such is the case of Alcine's island, which Roger, mounted on the hippogriff, discovers in Canto VI (st. 20-23). From an overhanging cartographic vision, we very quickly move, as the hippogriff descends to land, to an oblique, then grazing panoramic vision : birds appear under the foliage, then fallow deer and goats under the groves, finally the flower-dotted grass trodden by Roger.

.To this poetic movement of fictional spectacularization, supported and accentuated by the deployment of Ariostian imaginary geography, we must, however, oppose a rigorously inverse and deceptive movement, which magnetizes and precipitates the characters towards their disappearance from the visible surface of the narrative territory. This second tendency is first polarized around Brunel's magic ring, which renders invisible whoever puts it in his mouth. In Canto III, the magician Mélisse reveals its existence to Bradamante, who must obtain it to deliver Roger her lover from Atlant's spells. In Boiardo's Roland amoureux, the ring had actually belonged to Roger39. Bradamante recovers the ring in canto IV; she entrusts it to Mélisse, who gives it to Roger in canto VIII. Roger, fighting the orc on the Isle of Ebudian in canto X, gives the ring to Angelique, chained to the rock, so that she doesn't suffer the magical effects of Atlant's shield. In Canto XI, Angélique uses the ring to escape Roger, who has arrived with her in Basse-Bretagne and tries to rape her. Angélique reappears in song XII in front of Sacripant, then disappears again to the beard of her pursuers (sts. 57-60). In chant XXIX, faced with the crazed Roland, who stands before her and Médor, she again uses her ring, which " makes her disappear like a light that a breath puts out " (st. 64).

But the ring isn't the only instrument of invisibility. The castle where Atlant has locked Roger up, with its steel walls, is a space of invisibility that cannot be accessed (song IV, st.12), from which there is no return (song IV, st.7) and whose /// walls, reflecting the surrounding landscape, hide the presence from view. Bradamante destroys this fictional castle (" finzïon ", st. 19 ; " figmento ", st. 20) to free Roger, who immediately escapes her on the hippogriff. But above all, Atlant, who has fled, rebuilds his castle in Canto XII. The knights who enter it, and Roland in particular, fictitiously find the object of their desire, whose simulacrum they pursue inside: their desire thus keeps them artificially imprisoned. The château is not destroyed until Song XXII, by Astolphe.

Other castles in Roland furieux proceed from the same imaginary space, removed from visibility and troubling vision : Alcine's castle in Canto VII, similar to Circe's dwelling the Senapes' castle in Ethiopia, in Canto XXXIII, doubly cursed before Astolphe's intervention. The Sénapes is blind and harassed by Harpyes, who pillage and defile his meals, reducing him to starvation (song XXXIII, st. 112-115). Similarly, the Palace of Time, in Canto XXXV, contains the names of men whose plaques are inexorably cast into oblivion by the waters of Lethe: only two swans manage to keep a few names safe. This palace, then, is yet another vortex of invisibility, where the figures of fiction are precipitated into annihilation.

Thus emerges the polarity that orders the fictional device of Roland furieux : on the one hand, the territories of narration constitute the geographical, visible body of fiction ; on the other, rings and castles precipitate narration into a void that signifies its end, through the disappearance of characters, or their damnatio memoriæ. The space of the spectacle then appears to be bordered by the time of oblivion, with narration ensuring the transfer of one into the other, from the full but vain surface of the map to the empty but total body of infigurability. In this transfer lies the human enigma of desire: driven by their desire, the characters plunge into these vortexes of death. It's not a question of ignoring them, but of stopping at their edge, as Renaud does at the tale's last allegorical château, in Canto XLIII: he won't drink from the cup that reveals the women's infidelity. The geographical moment of fiction subsists at the cost of this misrecognition.

List of illustrations

Fig 1. Tractations for Bradamante's marriage. Illustration from Canto XLIV of Roland furieux, Venice, Valgrisi, in-8°, 1556, reprinted 1562, BnF, Résac YD 389. Wood engraving after a drawing by Dosso Dossi (?).

Fig. 2. Roger among the Bulgarians. Detail of previous engraving (upper part).

Fig. 3. Agramant's assault on Charlemagne in Paris. Illustration of Canto XV, Venice, Valgrisi, 1562, BnF, Résac YD 389.

Fig. 4. Griffin at the gates of Damascus. Illustration from Canto XVIII, Venice, Valgrisi, 1562, BnF, Résac YD 389.

Fig. 5. Griffin at the gates of Damascus. Illustration from Canto XVIII, Venice, Valvassori, in-4°, 1566. Wood engraving. Montpellier, Médiathèque Émile-Zola, 10948 RES in-4.

Fig 6. Griffin at the gates of Damascus. Illustration from Canto XVIII, Venice, Franceschi, 1584, BnF, Résac YD 396. Copper engraving by Girolamo Porro.

Fig. 7. Medor praying to the moon. Detail of fig. 5 (upper part).

Fig. 8. Guidon and Marphise in Alexandrette. Illustration from Canto XX, Venice, Valgrisi, 1562, BnF, Résac YD 389.

Consulted works

Anonymous, Lancelot du lac. Roman français du XIIIe siècle, Elspeth Kennedy [ed.], François Mosès [trans.], Paris, Librairie générale française, 1991.

Ariosto, Ludovico, Orlando furioso, Venice, Antonio Zatta, 1776, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des Imprimés, cote 4-YD-157.

Ariosto, Ludovico, Orlando furioso, /// Venise, G. A. Valvassori, 1566, Montpellier, Médiathèque Émile-Zola, call number 10948 RES in-4°.

Ariosto, Ludovico, Orlando furioso, Birmingham and Paris, Jean de Baskerville and Jean-Claude Molini, 1775.

Boiardo, Matteo Maria,Orlando innamorato, Venice, Giovani Battista Brigna, 1655, Bibliothèque de l'École normale supérieure.

Coccia, Paolo, " Le illustrazioni dell'"Orlando furioso" (Valgrisi, 1556) già attribuite a Dosso Dossi ", La Bibliografia 3 (1991), p. 279-309.

Coste, Florent, " L'île et le chaos dans le Quart Livre ", Tracés. Revue de sciences humaines, 3 (2003), p. 71-92, http://traces.revues.org/index3553.html (page consulted May 18, 2009).

Fumagalli, Elena, Massimiliano Rossi and Riccardo Spinelli, L'Arme e gli amori. La poesia di Ariosto, Tasso e Guarini nell'arte fiorentina del Seicento, Livorno, Sillabe, 2001.

Gardair, Jean-Michel, " Index analytique ", in L'Arioste, Roland furieux, Francisque Raynard [trans.], 2003, t. II, p. 481-552.

L'Arioste, Roland furieux, André Rochon [trans. and ed.], Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 1998-2002, 4 t.

L'Arioste, Roland furieux, Louis d'Ussieux [trans.], Paris, Brunet, Paris, 1776, Bibliothèque municipale de Lunel, Fonds Médard.

Lestringant, Frank, Le livre des îles. Atlas et récits insulaires de la Genèse à Jules Verne, Geneva, Droz, 2002.

Lestringant, Frank, " L'insulaire de Rabelais ou la fiction en archipel (pour une lecture topographique du Quart Livre)", Études rabelaisiennes 21 (1988), p. 248-274.

Rossi, Massimiliano and Fiorella Gioffredi Superbi (eds.), L'Arme e gli Amori. Ariosto, Tasso and Guarini in Late Renaissance Florence, Florence, Olschki, 2004.

Troyes, Chrétien de, Le conte du Graal ou le Roman de Perceval, Charles Méla [ed.], Paris, Librairie générale française, 1992.

Notes

In the same vein, the Brigna edition (Venice, 1655) of Boiardo's Orlando innamorato, which advertises being provided with " di bellissime Figure nove ad ogni Canto " (" de très belles gravures nouvelles à chaque chant "), in fact reproduces, for the most part and in no particular order, the engravings of the Giolito de Ferrari edition of 1549, an edition not by Boiardo, but... by Ariosto !

. ///Vincenzo Valgrisi, active from 1539 to 1572, was a bookseller printer of French origin. He left Lyon in 1539 to set up in Venice, then Rome. His two sons, Giovanni and Felice, took over from him in Venice from 1573.

After 1572, the editions of 1579 and 1580 bear the mention " appresso gli heredi di V. Valgrisi ". The attribution of the drawings for the engravings in the Valgrisi edition to Dosso Dossi is disputed today. See Paolo Coccia, " Le illustrazioni dell'"Orlando furioso" (Valgrisi, 1556) già attribuite a Dosso Dossi ", La Bibliografia 3 (1991), p. 279-309.

Francesco de' Franceschi (1500-1599), a Venetian bookseller originally from Siena, worked in association with Giovanni Criegher from 1567 to 1569, with Giovanni Battista Ciotti from 1592 to 1594 and with Giorgio Angelieri in 1599. I have found only one printing of this edition, dated 1584.

This eclipse concerns the Roland furieux, not illustrated editions in general. In the manner of the illustrators of the Valgrisi and Franceschi editions of Ariosto, we should mention the fine illustrated editions of Pastor fido (Venice, Ciotti, 1602, in-4°) or Ovid's Métamorphoses (Paris, Veuve l'Angelier, 1617). These two printing workshops are linked to Franceschi (see previous note) : the narrative engravings they print, aesthetically very successful, historically constitute a regression, or at least a stagnation in the process of scenic unification.

The two most important editions are those of Jean Baskerville and Jean-Claude Molini (Birmingham and Paris, 1775) and Brunet (Paris, 1776), both of which are linked in terms of illustrations. Also worthy of note is the in-4° Venetian edition by Antonio Zatta, published for the 1st time in 1772.

For the text, our reference edition is the following bilingual edition : L'Arioste, Roland furieux, André Rochon [ed.], Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 1998-2002, 4 vols. We have reproduced the translation as closely as possible to the Italian text. We have also consulted Jean-Michel Gardair's index in L'Arioste, Roland furieux, Francisque Raynard [trans.], 2003, t. II, p. 481-560.

In engravings of the time, characters are usually identified by the first three letters of their name. Here, " RIN " for Rinaldo and " RVG " for Ruggiero. The episode refers to stanzas 4 to 11 it is the first episode of the song, after the moralizing preamble of stanzas 1 to 3. In principle, narrative engravings are read from bottom to top. Episodes are represented in perspective: the further into the song, the smaller they appear. The margin of freedom in selecting the episode illustrated in the foreground is therefore reduced : it is necessarily found in the first stanzas of the chant.

From left to right, " OR " for Orlando, referred to here (st. 11) as " el principe d'Anglante " ; " SOB " for Sobrino (Canto XLIII, st. 192) no initials visible on the engraving for Olivier in the background.

Sobrin is actually depicted twice : the first, in arms among the knights and with his initials (" SOB "), visible halfway up the rocky hem of the cave ; the second, on the left, unarmed and next to the hermit.

The initials " OR " and " R " (Roland and Roger, on the boat's hull), then " O ", " S " and " RVG " (Olivier, Sobrin, Roger, on the rocky hem). See st. 18.

We've tried to systematically transfer, in brackets and without quotation marks, the captions inscribed in the engraving, striving to respect the original typography and punctuation as closely as possible. The two or three caption letters are sometimes followed by a period, sometimes not, usually in capital letters, sometimes not.

Above the figures read " RI ", " OR " and " SO ", and, below and aligned : " RV ", " AST " and " OLI ". Astolphe is surrounded by his companions. The Marseilles harbor wall is blocked by the wooden footbridge that provides access... from above and without a door !

" tra Pirpignano assisa e Carcassone " (st. 73) ; /// " PIR " and " CAR " on the engraving.

Perhaps the illustrator misunderstood " contrada ", contrée, which can also mean neighborhood, burg ?

Note that this escape is supposed to take place between the Danube and Belgrade, where the Bulgarians retreat, and not, as depicted here, between the Rhine and the Meuse.

The Bizerte episode, which finds its brief conclusion here, was developed in chants XL-XLIII. Agramant and Sobrin, defeated at Bizerte, take refuge in Lampedusa, where they have challenged Roland and his companions. Roland, who wants his horse Bayard and his sword Durandal back, accepts the challenge and wins.

We can compare the lower part of this engraving from Canto XV (or the entire engraving in the Valvassori edition) with several illuminations from a Perceval from the late 13thth century (Bibliothèque de la faculté de Médecine de Montpellier, ms. H249), pitting the knight against a door (f° 9 v°, 11 v° and 170 v°) or, better still, a horde outside against a knight framed in a door (f° 38 v°). The heading for this illumination reads: " Comment li vilain assaillirent monseignor Gauvain en la chambre a la damoiselle et brisierent luis ". See Chrétien de Troyes, Le conte du Graal ou le Roman de Perceval, Charles Méla [ed.], Paris, Librairie générale française (Livre de Poche), 1992, p. 418sq., v. 5866sq.

Compare with Astolphe's gift of the windskin to the Senapes (song XLIV, st. 21-22).

Begun under Trajan, completed under Hadrian, Trajan's canal fell into disuse in Byzantine times. Cleaned and recreated by Omar, it took the Arabic name of Canal du Prince des Fidèles, and was deliberately silted up 150 years later, in 775, by the Abbasid caliph Abou-djafar almansor, for military reasons.

Astolphe's battle with Caligorant is broken down into three drawings, which must be read by going back : to the right of Cairo (" CAIRO "), the dragon attempts to take Astolphe from behind (st. 52) below, at the edge of Arabia, Astolphe pursues him above, further to the right, the dragon is caught in his own net (st. 54).

" Orrilo " is noted " Horrilo " in all early editions. The tower of Orrile, near the mouth of the Nile (st. 65), is depicted above Cairo, but the engraver mistakenly mentions " CA " for Caligorant. To the right of the tower, Astolphe rides towards Jerusalem (" GIERV "), holding Caligorant tied behind his horse. Astolphe's battle with Orrile, in the presence of Griffon and Aquilant, is depicted further right in five sequences: on the left, Astolphe arrives dragging Caligorant behind him. Above, Griffon (" GRI ") and Aquilant (" AQUI ") fight Orrile (" HORR ") in front of the two fairies protecting them (st. 67, 72). On the right, Astolphe, followed by Caligorant, Griffon and Aquilant, is received in the fairy castle (st. 76). On the right, beneath the castle, Astolphe confronts Orrile. Still below, he is pursued by Orrile, whose head he has cut off : he will scalp this one to remove the hair on which his life depends (st. 87).

Same effect on the engraving in Canto XLIII, where the map of the /// Renaud's journey on the Po River serves as a backdrop to the allegorical palace where he has been offered the cup that reveals adultery.

It is designed on the same model as the agon illustrated in the engraving in Canto XV ; to the valiant Griffon, on the left, corresponds, also on the left, Charlemagne's tower bristling with pikes ; to the assault by Agramant's companions, as a troop, the stampede of the citizen-soldiers of Damascus.

In the text, they lodge on the outskirts of the city and go to the tournament alone.

This division of territories is, for Canto XVIII, specific to the Valgrisi edition. The extreme sinuosity of the Ariostian narrative in this song led illustrators to a variety of solutions. In the Valvassori edition, the ramparts, depicted as horizontal bars, divide the image into three parts: Griffon routing the Damascenes at the bottom, Astolphe overcoming Aquilant at the second Tournament of Damascus in the center, Médor under the moon between the Sarrazin camp and Paris at the top. In the Franceschi edition, the tripartition is also very clear, but it's Paris that occupies the center, with Rodomont's battles, while Damascus is back in the picture at top right : the story of Cloridan and Médor is only barely suggested at top left.

The engraving, which builds on stanza 70 (" But I leave [Griffon], for it is to his brother Aquilant and to Astolphe in Palestine that I turn "), depicts Aquilant accompanied by Astolphe before the pilgrim (" AQI ", " AST " and " P "). The narrator " [turns] " to both characters, but abstractly and separately ! Aquilant, however, asks Astolphe for his leave as he leaves Jerusalem (st.73). Astolphe then travels to Damascus, on hearing of the tournament (st.96), but separately from Aquilant. He meets up with Marphise and Sansonnet (st.100). Aquilant sees Astolphe again only at the tournament, where he is defeated by him (st. 118) : it is this pass of arms that is depicted on the engraving in the center of Damascus.

" che la terra del Surro il dí seguente / vide e Saffetto, un dopo l'altro tosto. / Passa Barutti e il Zibeletto, e sente / che da man manca gli è Cipro discosto. / A Tortosa da Tripoli, e alla Lizza / e al golfo di Laiazzo il camin drizza. " The map shows Tyre on the land route on the left (" Sur. " for Surro), then Sarepta by the sea on a promontory (" Saff. " for Saffetto), then Beirut (" Barut " for Barutti), Djebaïl (" zibil " for Zibeletto), Tortose (" Tortosa "), Tripoli, Latakieh (" Lizza "), the Gulf of Alexandrette (" Laizzo " for Laiazzo). Cyprus (" CIPRO "), with its port of Famagusta (" Fama " for Famagosta), is above Tortose, Tripoli and Latakieh, and crosses the return route of Marphise, Astolphe and Sansonnet (" AST ", " MAR " and " SAN ", st. 134-140) after their exploits in Damascus.

Ariosto's own text presents itself as a cartographic indication : " Verso Lidia e Larissa il carmin piega : / resta più sopra Aleppe ricca e piena " (" Vers Lydda et Larisse il tourne son chemin ; Alep reste plus au dessus, riche et pleine ", st. 77). " Piega " marks the turning point in the itinerary, while " sopra " only makes sense through /// in relation to a map.

" La Luna a quel pregar la nube aperse / (o fosse caso o pur la tanta fede), / bella come fu allor ch'ella s'offerse, / e nuda in braccio a Endimïon si diede. / Con Parigi a quel lume si scoperse / l'un campo e l'altro ; e'l monte e'l pian si vede : / si videro i duo colli di lontano, / Martire a destra, e Lerí all'altra mano. // Rifulse lo splendor molto più chiaro / ove d'Almonte giacea morto il figlio. / Medoro andò, piangendo, al signor caro ; /che conobbe il quartier bianco e vermiglio : / e tutto 'l viso gli bagnò d'amaro / pianto, che n'avea un rio sotto ogni ciglio, / in sí dolci atti, in sí dolci lamenti, / che potea ad ascoltar fermare i venti " (st.185-186).

We've already encountered this panoramic effect of the third territory at the end of Canto XLIV, when Leon contemplates Roger's exploits against the Greeks from a knoll (st. 89-93).

" Di questo altrove io vo' rendervi conto ; / ch'ad un gran duca è forza ch'io riguardi, / il qual mi grida, e di lontano accenna, / e priega ch'io nol lasci ne la, penna. // Gli è tempo ch'io ritorni ove lasciai / l'aventuroso Astolfo d'Inghilterra " (Canto XV, st. 9-10).

" ma sia per questa volta detto assai / dei glorïosi fatti di Ponente. / Tempo è ch'io torni ove Grifon lasciai... " (song XVIII, st. 59).

" ma quivi stiano tanto, ch'io conduca / insieme Astolfo, il glorïoso duca " (song XLIV, st. 18).

The meeting will take place at stanza 26.

See also Lancelot du lac. Roman français du XIIIe siècle, Elspeth Kennedy [ed.], François Mosès [trans.], Paris, Librairie générale française (Livre de Poche), 1991, ch. 2, p.69 (end of chapter) : " Mais ci endroit ne parole plus li contes ne de Banyn ne Claudas ne de sa compaignie, ançois retorne au roi Ban dont il s'est longuement teüz. " In the edition quoted here, this sequencing gives rise to a division into chapters. Thus we find similarly, at the end of ch. 3 : " Mais atant se taist ores li contes de la reine et de sa conpaignie et retorne au roi Claudas de la Deserte. En cet endroit le conte dit que [...] " (ibid., p. 80-83). The formula that will be most prevalent appears at the end of ch. 6 : " Mais de lui ne parole plus li contes ci endroit, ençois retorne à parler de Lionel [...] " (ibid., p. 98). An identical formula is found on pages 136, 160, 182, 210, ..., 682, 690, 702, 722, etc. Some examples of variants : " Mais d'aus lo laisse atant ester li contes ici endroit que plus n'en parole " (ibid., p. 112) ; " Si ce taist orendroit li contes de lui " (ibid., p. 680). This process is also evident in La Mort du roi Arthur.

" [...] ançois tient li contes sa droite voie et dit que li roi Bans avoit un sien veisin qui marchissoit a lui par devers Berri, qui lors estoit apelez Terre Deserte " (ibid.ch. 1, p.41).

On this subject, see Elena Fumagalli, Massimiliano Rossi and Riccardo Spinelli, L'Arme e gli amori. La poesia di Ariosto, Tasso e Guarini nell'arte fiorentina del Seicento, Livorno, Sillabe, 2001, and M. Rossi and Fiorella Gioffredi Superbi (eds.), L'Arme e gli Amori. Ariosto, Tasso and Guarini in Late Renaissance Florence, Florence, Olschki, 2004.

Frank Lestringant, Le livre des îles. Atlas et récits insulaires de la Genèse à Jules Verne, Genève, Droz, 2002, as well as " L'insulaire de Rabelais ou la fiction en archipel (pour une lecture topographique du Quart Livre)", Études rabelaisiennes 21 (1988), p. 248-274. See also Florent Coste, " L'île et le chaos dans le Quart Livre ", Tracés. Revue de sciences humaines, 3 (2003), p. 71-92, http://traces.revues.org/index3553.html (page consulted May 18, 2009).

Boiardo himself borrowed it from Lancelot du lac : in it, the Lady of the Lake gives it to Lancelot as she separates from him in front of Arthur. : " [...] et li dit qu'il a tel force qu'il descuevre toz anchantemanz et fait veoir " (Lancelot du lac, op. cit., ch. XXI, p. 431).

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Les trois territoires de la fiction : le Roland furieux et ses illustrateurs », Geographiae imaginariae : Dresser le cadastre des mondes inconnus dans la fiction narrative de l’Ancien Régime », dir. M.-Ch. Pioffet et I. Lachance, Presses de l’Université Laval, Éditions du Cierl, « Symposiums », 2011, p. 165-193, 8 ill.

Arioste

Archive mise à jour depuis 2003

Arioste

Découvrir l'Arioste

Épisodes célèbres du Roland furieux

L'île d'Alcine

Angélique au rocher

Bradamante et les peintures

La folie de Roland

Angélique et Médor

Editions illustrées et gravures

Principales éditions de l ’Arioste

Les trois territoires de la fiction

L’effet Argo

Gravures performatives

Gravures narratives

Gravures scéniques