The motif of fighting over a corpse: the story of Cloridan and Medoro (Cantos XVIII and XIX)

Ariosto based the story of the chant X about Biren's betrayal and Olympus' abandonment. The Enlightenment and the nineteenth century favored, isolated and fetishized the late episode of Roger's fight to free Angelica from the orca, and the single icon of Angelica at the rock. But the hijacking of the text, the shift in hierarchies within the narrative, is even more blatant when it comes to the chant XIX.

First, Ariosto completes his account of the exploits of Médor, the young Saracen soldier who returns to the battlefield by night to recover the body of his captain Dardinel and give it a burial. The epic model to which this story refers is the fight between Menelaus and Ajax over the body of Patroclus killed by Hector:

" While in his soul and body [Menelaus] rolled this spensées,

The Trojan line advanced. Hector was leading it.

Then Menelaus stepped back and left [Patroclus'] body there,

Not without turning around. It was like a hairy lion

That men and dogs try to chase out of their barn

With pikes and shouts; his valiant heart froze

Within him, and he left the enclosure only with regret :

In the same way the blond Menelaus moved away from Patroclus

And only turned back after joining his own.

Seeking with his eyes the great Ajax, Telamon's son,

He soon spotted him, far to the left of the fighting,

Reassuring his people and urging them to fight,

Phœbos having thrown a mad panic over them.

So quickly he ran to join them and said these words to him again:

"Dear Ajax, help me save Patroclus' body

And let's try to bring him back to the Peleid Achilles,

But without his weapons, which the proud Hector has stolen from him."

He said and the valiant Ajax was touched at heart.

He gained the forwards, escorted by the blond Menelaus..." /// (Iliad, Canto XVII, vv. 106-124, trans. Frédéric Mugler.)

Homerius attaches particular importance to the question of burying the dead. To deprive a hero of a burial is the worst ignominy to provide him with a funeral is a sacred duty, worth risking one's life for. And yet, while Menelaus' battle alone, then aided by Ajax, is heroic, the expedition of Médor and his friend Cloridan turns into a farce: "I'm of the opinion that opportunities should never be wasted," exclaims Cloridan as he crosses the sleeping Christian camp. Médor, must I not take advantage of this one to slaughter those who killed my master?" obviously a massacre on such cheap terms is totally contrary to the rules of chivalry, and contrasts singularly with the delicacies of Roland crossing the Sarazin camp as he leaves Paris, at the beginning of Song IX (see the engraving of G. Porro).

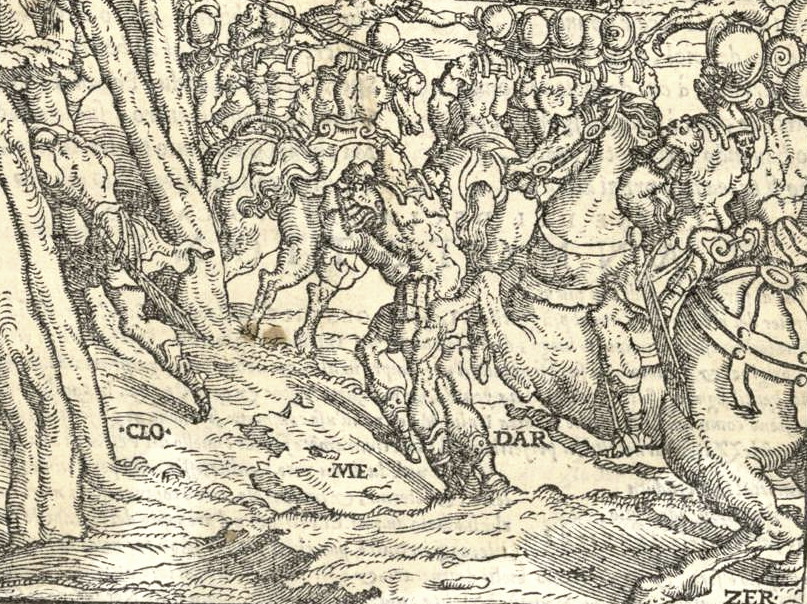

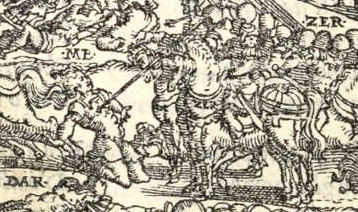

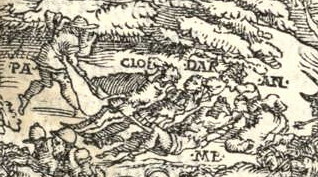

After an inglorious slaughter, the pair finally arrive at the battlefield (XVIII, 182), where the corpses piled up in the dark make it difficult to identify Dardinel. Once Dardinel has been found under the cover of the moon (see the engraving by Moreau le jeune), it's time to flee, as horsemen led by Zerbin arrive (st. 188): but the captain's body is heavy, preventing Médor from running fast enough: what trivial details for a heroic feat! Had Homer even considered the weight of Patroclus' body? (See the engraving by Novelli, which illustrates Canto XVIII, and that of Canto XIX in the Valgrisi edition.)

The Ariostian narrative thus parodies its Homeric model, without lapsing into satire: it's the literary genre and the narrative device that are deconstructed here, not the character and his story, treated instead in a moving, human way. The pity that seizes Zerbin in the face of Medor's beauty and courage, an episode that Girolamo Porro treats in the manner of a stage scene in the Franceschi edition, is a great moment of humanity, even if it is immediately upset by the untimely spear-thrust of one of Zerbin's companions.

To the external parody must be added an internal one: just as there were two fights against the orc and two maidens at the rock, the motif of fighting over a corpse is treated twice : Médor's fight for Dardinel (Médor is compared to a bear instead of the Homeric lion, XIX, 6-7) Cloridan's fight for Médor (XIX, 14-15).

Angélique et Médor - Bloemaert

Angelica and Medoro, or the birth of the Pastoral

After Cloridan has been killed by Zerbin's troop and Médor has been left for dead on the battlefield beside his captain and companion, Angélique stumbles into this space littered with corpses : the epic becomes pastoral.

While Medoro and Cloridan's battles over Dardinel's body disappear from Baroque rewritings of Roland furieux for opera (see the tapestry cartoon of Coypel illustrating the Roland furieux by Lulli, for the music, and Quinault, for the libretto), what will remain and even take on its full development are the gradually standardized figures of the young leading man, Medoro, the unfaithful belle, Angelica, and the spurned lover, Orlando. Orlando's own madness, wild and devastating to the Orlando furioso's Canto XXIV, is aestheticized, moderated, remodeled into an air of spite ///

What's Ariosto all about? Angélique has been pursued since the first song by every knight in the land: not only Orlando, but Sacripant, Ferragus, Rinaldo.... Twice she almost gets raped: by the hermit in Canto VIII (see the painting by Rubens, the engraving by Moreau le jeune or the drawing by Fragonard), by Roger in Canto XI (see the engravings in the Valvassori edition and the Valgrisi edition). At the Canto XII, she narrowly escaped her coalesced pursuers in Atlant castle. A pirouette is used to bring this unbridled tale to a close. The pirouette is a bizarre, insulting marriage to a common soldier. It is also an act of feminine independence and freedom: Angélique refuses to be used as booty, as an object of epic performance; she chooses her husband, and chooses him in such a way that she will not later have to be subjugated to him. This extraordinary hymn to initiative, to the autonomy of feminine desire, was completely subverted in the 17th and 18th centuries, when Angélique became a princess-bergère who succumbed, rather hastily, to the naive solicitations of a soldier-shepherd who was younger, fresher and more enterprising than her rival Roland.

The same reversal can be seen in the iconography: if the Angélique of Toussaint Dubreuil, in 1580, still supervises and controls the writing of the inscription, that of Bloemaert, who in 1620 nonetheless formally takes up the same device, takes a back seat and raises timid, subjugated eyes to her new master, who tackles an abandoned breast without much resistance... Boucher, in 1765, again reinterprets in his own way the device imagined by Toussaint Dubreuil : the inscription disappears, which articulated in the Ariostian narrative the pastoral parenthesis of Angelica's lovemaking to the epic tale of Orlando's madness. Dreamily, Angelica waits molly to be deflowered, all risk of pursuit, all threat of interruption, all pressure of military and chivalric events now removed. Tiepolo, however, in the same rococo aesthetic, revives the Ariostian spirit, depicting in the Villa Valmarana a conquering Angelica, herself engraving her lover's name on the bark of a tree.

Even if Ariosto is neither the only origin nor the only reference in this field, it can be said that the idyll of Angelica and Medoro founded a genre, the genre of the pastoral, whose rise and cultural impact would be considerable until the eighteenth century, as witnessed, for example, by the numerous reprints and performances of Guarini's Pastor fido, but also the writing of Aminte by Tasso, alongside the Gerusalemme liberata.

The pastoral, however, is not reduced to the sweet idylls of shepherdesses and shepherds in the unreal and charming locus amoenus of their clean sheepfolds and flowery meadows. A whole meditation on death is elaborated in these texts and paintings, as evidenced by the famous motif of the Et in Arcadia ego, an enigmatic formula that could be translated as follows: Et moi aussi la Mort, je hahaante les lieux de l'Arcadie heureuse. It makes sense, in this context, that the idyll of Angélique and Médor is framed by Médor's injury and Roland's madness. The motif of Angelica nursing the wounded Médor would be taken up by Tasso, who imagined Herminie treating the wounded Tancredi, not with herbs, but with her own hair.

See the notices for Canto XIX.

The engraving for Canto XIX in the Valgrisi edition.

///

Arioste

Archive mise à jour depuis 2003

Arioste

Découvrir l'Arioste

Épisodes célèbres du Roland furieux

L'île d'Alcine

Angélique au rocher

Bradamante et les peintures

La folie de Roland

Angélique et Médor

Editions illustrées et gravures

Principales éditions de l ’Arioste

Les trois territoires de la fiction

L’effet Argo

Gravures performatives

Gravures narratives

Gravures scéniques