The boat of Theseus, theoretical model

It wasn't until the nineteenth century that literature began to massively summon the architecture, urban ensembles and rural landscapes of its own time1. The work of literature then consists in turning these contemporary documentary data into sites and signs of our culture, our history, our identity, thus helping to transform these objects, these spaces of reality into objects, spaces of heritage.

This work of literature is deeply linked to the semiological revolution initiated by Romanticism and Realism. By becoming the referent of the literary text, the real forces the writer to articulate and connect in a new and, as it were, unnatural way. To authenticate the text, it is necessary to bring into it that which is irreducible to the text, the raw materiality of reality, the incomprehensible dimension of what is given as encountered, in its raw state, in its random and immediate novelty. There is, for example, the brutality of the monument, which is built on a gutted city, in an evicted neighborhood, or which, on the contrary, collapses, disappears, swept away by new constructions. There's also a secret, diffuse brutality to the landscape, which surrounds and oppresses, or on the contrary, on which hangs the invisible threat of modernity. Paradoxically, space is not constituted as heritage because it becomes a place of memory, but it becomes a place of memory because it is confronted with this brutality of the new times, that it becomes its most visible sign.

Literature's relationship to the real is therefore twofold. Certainly, the real authenticates literature, and can only authenticate it brutally, by forcing the passage, so far removed is fictional, poetic, theatrical space from it, traditionally. But above all, literature in turn authenticates reality, transforming it into heritage. In this way, the gap between reality and representation is narrowed: the reality that literature conjures up tends to present itself as a reality already mediated by culture. Between the real and the literary text slips the mediation of the document, the preparatory file, the reverie that textualizes space the cathedral is a poor man's bible, and therefore a book the city unfurls its pages of history and globalizes itself as a " theater " where a " drama " the castle, the museum are visited and browsed like a list of textual references. Beyond the reality it absorbs, literature discovers or finishes discovering text. The text would only have transited into the real, which, having become a heritage object, thus veils, recovers its fundamental but unbearable brutality.

Literature's patrimonialization of the real is a way of restoring aura to a referent no longer immediately endowed with it2. This artificial aura does not manifest or detach the singularity of the heritage object, as the old aura could. On the contrary, it acts as a link, a mediation, attenuating the fracture consubstantial with realism, taming reality in literary space. In a way, for literature, heritage is the reverse side of reality, whose brutality it both erases and designates.

Before 1800 : literature as a space of heritage circulation

We might therefore ask whether the notion of heritage makes sense in pre-Realist culture, and whether the articulation between heritage and literature is relevant in a world where the category of the real is not operative. The culture of the Renaissance through to the Enlightenment is in fact constituted above all, in Thomas Pavel's phrase, as " art de l'éloignement "3, i.e. as an art which claims, far from /// of reality, its artificiality. Descriptions are rare in the classical novel, didascalies absent from theatre places are names the inconsistency of the real in texts discourages a priori any linking of fictions with the monuments contemporary with those fictions.

It's not a question of manufacturing, through literature, artificial aura. The aura is there, undisputed, posited as pre-existing literature : aura of the ruins of Rome, of ancient myths aura of Jerusalem, half-terrestrial, half-celestial, and of the chivalry that accompanies it aura of medieval wonder, of its fairies and saints. The problem is not to create a new heritage, but rather to live with a heritage that has become, since the Renaissance, old, cumbersome and out-of-date, except for a few denials. This problem, which arose at the beginning of the sixteenth century, is not without similarities to the pedagogical problem and challenge that lead us today to call upon heritage to teach literature. Why, in our classrooms, does the magic of the text alone no longer work? Why do we need to integrate this text into a whole curriculum in which heritage plays a key role?

If we call upon heritage to explain literature (when it is literature that, by calling upon it, has constituted it as heritage), it's because this literature has suddenly become distant, difficult to access, that we know that it presents itself for our students and for us sometimes, as an old, ponderous and out-of-date heritage. Let's not be ashamed of this gap: the Renaissance and the Enlightenment experienced this phenomenon and were nourished by it. In humanist culture, literature's relationship with heritage is not one of authentication, but of innutrition. Feeding on dead culture in order to reconstitute and restore living culture does not mean designating this or that object as heritage, in a text that remains external to that object; it means perpetuating heritage in a text that itself becomes that heritage, encompassing it and substituting itself for it. There is here a logic of transmission and creation that is totally foreign to what the nineteenth century established as a principle of construction and inventory of culture, a logic paradoxically closer to us today, at a time when this culture of authenticity, inherited from the nineteenth century, is coming to an end.

.Heritage and innutrition

Literature's humanist relationship to heritage is therefore one of supplement : it is both a complement to heritage and a substitute for it.

This literary work of supplementation manifests itself notably in the phenomenon of rewriting, a well-known and now much-studied phenomenon. Approached as a dialectic of literature and heritage, rewriting can no longer be seen simply as the inspiration of one text by another text, but more globally as a vast circulation, operating, for example, from a painting to a story (oral or written fiction), itself contaminated by a myth, by an event, by a landscape. The media through which representation passes are manifold. The resulting composite object may circulate concurrently in the form of one or more texts, iconographic motifs, theatrical or musical performances. Literature thus appears immersed in the heritage from which it draws its substance and, in turn, produces and designates objects.

Master of the Cassoni Campana, early sixteenth century, Theseus and the Minotaur. Poplar wood, 69x155 cm, Avignon, Musée du Petit Palais. This panel from a Florentine wedding chest (cassone) is the result of a double adaptation of heritage: the /// The narrative unfolding of the story of Theseus is adapted to a still image; the heroic myth dresses up an object intended for familiar use. Heritage is myth, painting and trunk.

This non-external relationship of literature to heritage, this negative dialectic that presides over the circulation between text and heritage object or space, can in some ways be illustrated by an anecdote told by Plutarch in his " Life of Theseus ", an anecdote promised to a long and rich metaphysical future. Let's take the text in the translation by Jacques Amyot, who made it known in France during the Renaissance :

The vessel on which Theseus went and returned, was a galiotte with thirty oars, which the Athenians kept until the time of Demetrius the Phalerian, always removing the old pieces of wood, as they rotted, and putting new ones in their places : so much so, that since then, in the disputes of philosophers concerning things that increase, whether they remain one, or whether they are made other, this galiotte has always been used as an example of doubt, because some maintained that it was the same vessel, while others, on the contrary, maintained that it was not4.

The Athenians thus preserved for a thousand years the ship on which Theseus had sailed from Crete to rid them of the Minotaur. This mythical vessel had undergone so many restorations over the years that nothing of the original wood remained. Was what was piously displayed the authentic ship of Theseus, or another object distinct from it, a kind of representation of the ship rather than the ship itself ?

The uniqueness, the very identity of the heritage object makes no sense here, or remains an insoluble problem. What could the boat possibly have meant? It commemorated the exploit of Theseus, and hence the significance of the character of Theseus for the city of Athens.

It's not a question of the boat's identity, but of its significance for the city of Athens.

According to Plutarch, Theseus was the founder of the city of Athens, which nevertheless pre-existed it :

Again, since the death of his father ægeus, he undertook one thing great to marvel : it is that he assembled in one city, and reduced to one body of town the inhabitants of the whole province of Attica. " (Amyot XXVIII ; Ozanam XXIV,1.)

Of course, Plutarch's account of the synœcism that, by uniting the villages of Attica, gave rise to the city of Athens, is motivated by the parallel he intends to establish between Theseus and Romulus. Similarly, by making Theseus the inventor of a democracy that is nonetheless alien to the mythical world in which the hero evolves, Plutarch posits as a shortcut, at the threshold of his Parallel Lives, the face-off between the two democracies, Athens and Rome, that structures the whole of his work.

And having done this, he left his royal auctorate, as he had promised, and set about ordering the state and police of public affairs [...]. And may it be true, that it was he who first inclined to the government of public and popular things, as Aristotle says5, and who left royal sovereignty, Homere mesme seems to tesmoigner au denombrement des navires qui estoient en l'armée des Grecs devant la ville de Troye : by what he calls the Athenians alone among all the Greeks, people. (Amyot XXVIII and XXIX ; Ozanam XXIV,4 and XXV,3.)

Such a mixture of notions and eras would make the historian jump. Yet it is characteristic of the negative dialectic that articulates literature and heritage in pre-realist culture the new text supplants inherited culture it constitutes a mixed, totalizing object from heterogeneous bits of history, fragments of meaning. The work of literature on heritage is the work of repairing Theseus' ship. This ship was not only /// repaired in the material sense of the term, by substituting planks we can imagine that it was also the object of symbolic repair, first commemorating the victory over the Minotaur, then giving a heroic origin to the city, finally embodying the political identity of the city.

.Plutarch's text itself contains the seeds of a future work of repair, of mixing, of displacing the patrimonial materials from which it draws. Plutarch's account, for example, contains a strange detail. According to Clidemus, the anger of the Cretans against the Athenians was due to the flight of Daedalus, who had taken refuge in Athens. Minos, trying to pursue him by boat, died in a shipwreck in Sicily. However, Minos' boat did not comply with Greek legislation:

...

there was then a general ordinance by all Greece, which forbade any manner of people, to sail in vessels where there were more than five people, except to Jason, who was elected captain of the great nef of Argo, with commission to go here and there, to oster and chase away all coursaires and larrons escumans the sea (Amyot XXIII ; Ozanam XVIII,8).

The evocation of Theseus' nameless boat calls up, by a kind of contamination, of irresistible attraction, that of another mythical boat with a famous name, of this Argo with which Jason conquered the Golden Fleece. Isn't Theseus another Jason, and isn't his expedition to Crete the same as his expedition to Colchis? This time, it's not so much a question of establishing a parallel like that of Theseus and Romulus, which engages the macrostructure of the text, as of integrating the central story in depth into the heritage of mythical stories. Further on, Plutarch's intention is even more explicit:

...

And though in his time the other princes of Greece have done many fine and great feats of arms, Herodorus reckons that Theseus was not in one, except in the battle of the Lapithes against the Centaurs : and on the contrary, others say that he was on the Colchis voyage with Jason (Amyot XXXVII ; Ozanam XXIX,3).

Here, then, is Theseus sailing on Argo to conquer the Golden Fleece, as if the nameless ship tended to encompass, to become inauthentically the one with a name, the ship Argo.

In this logic, which we'll call the Argo effect, every heritage object is promised a series of repairs, both material and symbolic : materially, the text supplants the image ; the image, the music supplants the text symbolically, the same story, a name, a title, will be perpetuated from century to century by covering completely different meanings and above all, for the most fortunate objects, by encompassing by contamination elements (forms and meanings) originally completely heterogeneous.

The point, then, is not for literature to refer to an external heritage object, but to complement that object, to repair its wear and tear, to patch up through the literary work the insults that time has inflicted on culture. The work does not exist outside the heritage it invokes; it substitutes itself for it.

The Argo effect is therefore a logic of the supplement. But we shouldn't be too quick to substitute Plutarch's anecdote with the abstract, purely logical model of the supplement6. Repairing the boat is a matter of tinkering, of that tinkering with parts and pieces that Claude Lévi-Strauss has shown to be the driving force behind the creation of myths7. The contamination of objects and imaginary spaces of culture, their amalgamation to produce a totalizing work, is certainly a serious intention this collection of heritage works against oblivion it manifests a demand for cultural transmission, a duty to remember it tends towards a /// glorifying unification of its object. But the work's glorifying aim is disturbed by a certain awareness of the vanity, the ridiculousness, the senselessness of this bricolage. At the very moment when this totalizing object is being constituted, amalgamating the heterogeneous residues of a culture stricken by decay, the new work distances itself from this object and exacerbates its heterogeneous character. Note, for example, how Plutarch multiplies the sources he calls on, thus modulating the information he reports without taking it on board : Theseus didn't take part in the exploits of the other Greek heroes, but perhaps he did he did or didn't take part in the Centaurs' battle against the Lapithes he did or didn't board Jason's ship Argo...

.This constant contradiction between glorifying intention and distancing constitutes a mixed genre, what has been called the geloiospoudaion, or comic-serious, which characterizes not only philosophical dialogue, but more generally all enterprises of heroisation in which a certain parodic accentuation intervenes8. The totalization of the cultural network that the Argo effect tends to achieve induces a distance from this network, which becomes an object that we examine with both admiration and skepticism, exaltation and irony.

This is because there can be no work on heritage in literature without a manifestation of the insult of time : before this work, the heritage object appears somehow incomprehensible. The values, meaning and world it conveys are outdated, ridiculous or revolting: the humanist celebration of heritage, like the Alexandrian celebration, because it proceeds by supplement, by repair, is a parodic celebration. The Argo effect is not serious.

The example of Roland furieux

Ariosto's Roland furieux is a privileged object of study if we want to better understand this profound historical transformation in the relationship between literature and heritage. In a way, the text liquidates medieval culture, summoning that of antiquity and immediately establishing itself as an essential element of Renaissance artistic heritage, not only literary, but also musical and iconographic, as evidenced by the illustrated editions, paintings and documents on operas and ballets that have come down to us. The permanence of the Roland furieux in cultural space from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century makes it a privileged object of study : a single heritage object, which we'll call Roland furieux without identifying it exclusively with a text, or even of text, persists in the manner of Theseus' ship, merging with other texts, other iconography, other music to end up identifying with a certain culture and designating it as a whole. Although made up of documents and objects that could not be more material, this heritage ends up resting on the radical unreality of what it represents. The Roland furieux is detached from any referent and becomes, at the end of the nineteenth century, indecipherable or, worse, indifferent, for want of being able to assume the new function of authentication. While the costly restoration of cathedrals reflects the nineteenth-century idea of an authentic Middle Ages, the Roland furieux refers neither to the world of the epic, parodied by Ariosto, nor to the wars of the Italian Renaissance, very much present in the original text, but systematically retracted in its Baroque adaptations.

From engraving description to textual analysis

Ariosto's poetic language, and the cultural references he manipulates, make it awkward and thankless to approach the text from the scholarly philological perspective of the literary historian. Instead, we propose to enter the work through the illustrations to which the text, thanks to its /// success, gave rise as early as the sixteenth and continuously into the nineteenth century. The extracts presented and narrated by Italo Calvino in a recent edition9 will, for high school pupils or undergraduates, provide accessible reading of reasonable length.

The work will therefore first be given to see and told : humanist innutrition is as much visual and oral as it is bookish. The goal announced from the outset, and the exercise required of pupils or students at the end of the group work, will be to decipher and analyze an engraving. Simply deciphering a sixteenth-century narrative engraving usually requires a careful reading of the text. But this reading is only a working tool for the exercise. Of course, it's also a question of bringing reading, and the reading of a difficult text, to an audience that is not already familiar with it. So we'll have to read, but that's only a preliminary, the aim being to elucidate the image : in this way, we perhaps return to the essence of culture, which isn't acquired by reading texts but by learning stories, which doesn't require us to technically study works, but to concretely represent them.

Such an approach does not propose a cheap, simplified reading : we'll show that analyzing the engraving provides analytical tools for the text. Every engraving is already an explanation of the text, a document of how it was received and perceived in a given period. In this way, the abstract, difficult questions of rewriting, structural analysis and the workings of narrative are approached from concrete representations, from a visual material that is much richer, more accessible to the public of our time than the rhetorical tools that were still able to structure, some fifteen years ago, the teaching of literature and literary research.

.The engraving of Canto X in the Valgrisi edition

The narrative style of Renaissance illustration engravings lends itself particularly well to such an approach to the Roland furieux, grasped in its globality as a heritage object, in the interplay of cultural networks and contaminations of meaning and images that constitute it. Take, for example, the engraving of Canto X in the Valgrisi edition of 156210 : the multitude and meticulousness of the characters, often depicted several times in different situations and places, enabled the illustrator to represent the narrative content of the song almost exhaustively. We will show how the layout of the image establishes a system of territories that structures this song, and more generally constitutes the structuring mode of Ariosto's text. More difficult to perceive by reading the text alone, this system of territories manifests itself with simplicity and obviousness if we begin by analyzing the engraving.

Lodovico Ariosto, Orlando furioso, Venice, Valgrisi, 1562. Lower part of the engraving for Canto X. Cote Bnf Résac yd 389. On the right, Biren between Olympe and the daughter of Cimosque. On the left, Biren takes his clothes and abandons Olympe.

In Canto IX, Olympe, after sacrificing family and kingdom, implored Roland to deliver her lover Biren11, a prisoner of King Cimosque at Dordrecht in Holland. But Biren is saved and falls in love with Cimosque's daughter (X, 10), who is promised to his brother. Biren leaves Dordrecht by boat, taking Olympe and Cimosque's daughter with him. His ship /// then wanders off to a desert island (X, 16).

In the foreground of the engraving, on the right, the boat drops anchor on the island. In the boat are Biren, identified by the letters BIR, and two women. The one on the left is Olympe, as indicated by the letters OL above her hair.

Biren sets up the tent on the island and falls asleep with Olympe.

To the left, Olympe in the tent (OL is inscribed on the flap of the sheet), asleep and trusting doesn't see that Biren (center), picking up his clothes, is about to weigh anchor, abandoning her on the island. The vessel on the right represents both the time of arrival in daylight and the promise of stealthy departure in the dead of night. As for the central figure in the foreground, naked Biren holding his clothes in his arms, he makes sense only when caught in the network of what lies on either side of and slightly behind him.

Central left portion of the engraving. Bottom left, abandoned Olympus. For the rest, it's Roger's journey from evil to good: above Olympe, Roger fleeing is stopped by three followers of the diabolical Alcine. Above center, he reaches the shore. Then, on the right, he crosses the sea and overcomes Alcine's boats, visible at the very top, thanks to the flashes of light from Atlant's shield. Completely to the right, four ladies allegorizing four virtues welcome him to the island of Logistille.

In the central part of the engraving, on the left above the tent, Olympe forsaken at the tip of the island gestures grandly, imploring the return of the boat that abandoned her (X, 23). The boat is shown a second time, from behind, sailing off to the right with all sails and oars out.

.The shift to the background, which involves crossing the sea, introduces a narrative break, a change of story (X, 35). Facing each other, the artist has set the island of Alcine (ISOLA DI ALC.) on the left and the island of Logistille (ISOLA DI LOGI.) on the left, the palace of the lust fairy is barely visible : bare, the island is occupied by the characters. On the right, the magnificent palace of the fairy of reason, with its colonnades and hanging garden (X, 61), occupies almost the entire island.

.The characters organize the eye's path from left to right : mounted on his horse, Roger (RV, for Ruggiero) flees Alcine's palace. Three of Alcine's attendants try to delay him by tempting him, says the text, with the pleasures of the banquet (X, 36). The first, on the left, takes him by the stirrup to invite him to dismount; the second, in the center, grabs him by the arm; the third, in front of him, hands him a drinking cup and, with her left hand, a napkin and a dish. In the background of the island, to Roger's left, on a carpet spread out on the floor, we can make out two jugs and a pate.

.

Central right portion of the engraving. On the right, the Logistille palace, with its hanging garden. In the loggia, Mélisse talks with Logistille, then, on the right, Roger meets Astolphe again. At top left, Alcine's fleet is set ablaze.

Roger without stopping leaves the island with his horse on an old nocher's boat (X, 43). He is depicted a second time at the far end of the island, as if echoing the distraught Olympus in the background, and then a third time with his horse on the boat, in a sort of reprise of the "old nocher's boat". /// Biren's runaway vessel, drawn just below. In each case, RV identifies Roger.

Roger is pursued by Alcine's ships : these are the three ships the designer has placed above him. The knight confronts them with his magic shield, represented by the rays of light around the boat, meant to dazzle and annihilate his adversary (X, 49).

Roger is pursued by Alcine's boats.

Roger finally lands on the island of Logistille, where he is welcomed by four ladies with allegorical names indicated by initials : A for Andronique (Courage), P for Phronésis (Prudence), D for Dicille (Justice) and S for Sophrosyne (Wisdom) (X, 52).

On the far right, on the second floor of the Logistille palace, Roger is reunited with Astolphe (X, 64) : their initials, RV and A, can be distinguished. In the window on the left, the fairy Mélisse, who has restored Alcine's prisoners to their human appearance and brought them to Logistille, asks her for help and protection for the two knights (X, 65) : the characters are identified by ME and LO. On the roof of the palace, we can make out the vegetation of the hanging garden (X, 61).

The third shot reads from right to left, completing an inverted S-shaped path. On the right, Logistille's fleet, materialized by five ships, sets fire to Alcine's fleet, in the center, from which high flames escape. Alcine flees alone to her island in a tiny boat topped by an AL, in the center of the engraving (X, 54).

Top left of engraving. On the left, Renaud reviews the English troops. On the right, Roger mounted on his hippogriphe frees Angélique from the orca. Beneath the killer whale is the boat on which Alcine piteously returned to her island after the rout of her fleet. Above left, Roger and the freed Angelique land in Brittany.

.Completely to the left, under the sign of Alcine's palace, Roger (RV) holding the hippogriphe in his bridle completes his world tour and arrives in England, designated by INGH for Inghilterra (X, 72), where he joins Renaud (RIN, above the island on the right) sent by Charlemagne and reviewing the troops who will come in reinforcement to defend Paris (X, 74). To the right of the island, Roger (RV) demonstrates his hippogriphe in the air and over the sea to the amazed soldiers. Then he sets off for Ireland, indicated by IRLAN (X, 91).

Flying over the coast of Ireland, Roger spots Angelica (ANG.) offshore, tied to the rock on the Isle of Ebudians (EBV), also known as the Isle of Weeping (X, 93). From his hippogriphe, high up in the center, he fails to kill the orca with his spear (X, 101).

The text tells how he then entrusts Angelique with Mélisse's magic ring and dazzles the orc with Atlant's shield. Angélique begs Roger to leave the orc, which he has temporarily incapacitated, to deliver her and take her away.

The text tells how he then entrusts Mélisse with the magic ring and dazzles the orc with Atlant's shield.

Taking Angelique in rump on his hippogriphe, Roger passes into Brittany. We return to the left of the engraving: Ireland is now Brittany. Angelique and Roger are finally face to face, safe and sound.

Image topography, narrative device

Now that we've deciphered the engraving linearly as a whole, let's step back and try to consider it holistically. We find that the image can be viewed in two ways either we focus on narrative spaces, with their ruptures materialized by the sea, or we emphasize the perspective continuity of a global view, treated on the borderline between map and landscape. This space, at once divided and linked, is characteristic of /// of a network structure.

Each narrative sequence corresponds to a space in the engraving. The course of these narrative spaces organizes a system of territories : in the foreground, the island where Olympe is abandoned, in the second, the face-to-face meeting of the two allegorical islands, the island of Alcine and the island of Logistille, in the third, England, Ireland and the island of the Ebudians, define three distinct territories, at once separated by the sea and linked by boats and the hippogriphe. Each of these territories has a different semiological status or, if you prefer, corresponds to a different literary genre: here, the lower part of the image tells the unglamorous story of a betrayal in love ; the island of Olympe corresponds to the genre of the tragic story, the short story, the tale ; the middle part of the image is occupied by an allegory ; the upper part, with Renaud's review of the troops and Roger's fight against the orc, accesses the highest genre, the epic.

The tale, the allegory, the epic are immediately differentiated on the image : intimate tent space and trivial nudity below learned architecture and face-to-face symmetry in the center standards and battles above.

The journey from one territory to another in the text orders not so much a progression as a relationship that we'll find again from one song to the next. We'll see that, while the progression is different each time, the system of territories remains grosso modo always the same.

From the moment when we no longer consider narrative as a linear sequence of events, or even as the construction of a point of view or the interplay between several points of view on a story, but as a means of moving from one territory to another, the first analytical task that becomes necessary is to compare these different territories, to seek to find the same imaginary matrix that reduplicates and adapts in different spaces. We will then define the narrative device of a work as the poetic construction, i.e. as the mechanism implemented by the author to produce history, stories, from the same narrative matrix12.

The narrative matrix is a kind of actantial schema13 ramassé, a configuration of character-functions linked by symbolic stakes, this configuration being capable of being transposed into different narrative sequences, scenes, situations. In other words, the narrative matrix is the primitive scene of the text. The narrative device is the process of repetition, variation and obliteration of this primitive scene.

To identify the text's narrative matrix, we'll once again use the engraving : the boat in the foreground is taken up by the boat fleeing above it, then by the boat where Roger unveils the luminous shield, then by Alcine's tiny boat defeated, above, under the orca. To these figures of flight, we can contrast Olympe in her tent, then Olympe at the end of her island, then Roger at the end of Alcine's island, then Angélique on her rock, which are the opposite figures of the stop at the edge, of suspense and narrative rupture. Two chains of figures face each other and repeat themselves from the bottom to the top, until they multiply and scatter at the very top, on the right between the fleets of Logistille and Alcine confronted, on the left between the armies of Renaud and the antics of the hippogriphe.

There is thus a motif14 that repeats and recontextualizes itself as it moves from one territory to another, a motif made up of flight and arrest, surreptitious betrayal and the terror of being cornered at the edges. The figure of imprisonment and that of escape, clearly dissociated and opposed /// Angélique is both the imprisoned, abandoned, cornered woman, and the one who, surreptitiously, must escape. If we go back to the text, we discover at the beginning of Canto XI that Angélique, rescued by Roger as soon as she arrives in Brittany, flees by means of the magic ring he has entrusted to her, to escape unchivalrous advances.

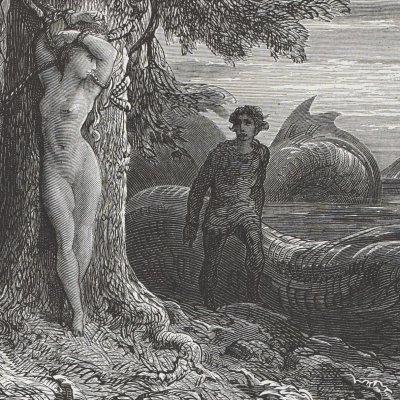

.Angelica Kauffmann, Arian abandoned by Theseus, second half of the eighteenth century, private collection.

The compositional principle is therefore superposition and reversion : superposition of the same motif taken from one territory into another, or into the same territory reversion of a motif into its antagonistic motif, until the articulation, the fusion of these opposites into a scenic device that is in some way oxymoronic. Angélique, here, carries the scenic oxymoron towards which the entire song converges. Angélique is the heart and principle of the system of territories. From this motif and compositional principle, we'll gradually tease out the narrative device of song X.

Importation and transformation of heritage

Ancient and medieval sources : borrowings and contaminations

This compositional principle of engraving and, a fortiori, of text should not be considered as an isolated and autonomous phenomenon, operating in autarky within a clearly delimited semiological space as an engraving or a song from Roland furieux may be. The engraving and the song carry out a work of composition, of innutrition begun upstream, with the tinkering of the heritage objects that are imported here, and continued downstream, in the continuation of the text, in its illustrations, adaptations, continuations. The Argo effect is an indefinite resonance.

Lodovico Ariosto, Orlando furioso, Paris, Plassan, 1795; Olympe abandonnée par Biren, copperplate engraving for Canto X signed at bottom, drawing by Giovanni Battista Cipriani, engraving by Francesco Bartolozzi (probably dating from 1776-1777). Cote Bnf Rés yd 91.

The principle of composition is therefore superimposition and reversion : superimposition of the same motif taken from one territory into another reversion of a motif into its antagonistic motif. This principle is continuous, from one Ariosto song to the next, but also from inherited heritage to recomposed heritage. Let's take a few examples: Olympe abandoned in the tent by Biren is presented to us by the illustrator in the posture of the medieval dream, as seen for example in Le Songe de sainte Ursule by Carpaccio (Venice, Accademia), the angel announcing to the sleeping saint her impending end, or in The Dream of Constantine by Piero della Francesca (Church of San Francesco in Arezzo), the angel points out to Constantine the sign of the cross by which he will defeat Maxentius15. At the end of the century, Le Tasse takes up the dream motif again, Hugues announcing to Godefroi in Canto XIV of the Jérusalem délivrée the forthcoming victory of the Crusaders if Renaud is recalled to the siege of Jerusalem.

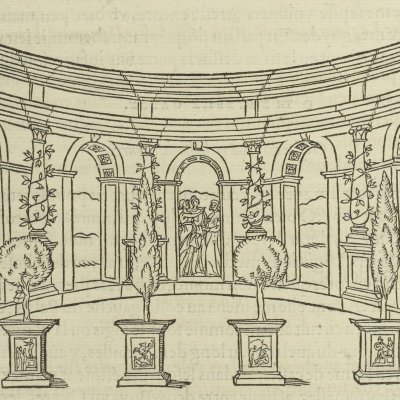

Le jardin en pots de Logistique, in Francesco Colonna, /// Le Songe de Poliphile, French translation by Jean Martin, woodcuts by Jean Goujon, Paris, Jacques Kerver, 1546, folio 41v°.

As for the tearful Olympus watching her perfidious lover's veils drift away, she evokes Ariadne at Naxos abandoned by Theseus, whose grief Catullus, for example, describes embroidered on Thetis's veil at Peleus's wedding16, and whom Guido Reni paints facing Bacchus who has come to propose marriage (The Los Angeles County Museum of Art). Ariadne, in the myth, slides from Theseus to Bacchus Olympus will likewise slide from Biren to Roland, who saves her from the orca only to get rid of her immediately by offering her to King Obert opportunely landed on the shore of the island of the Ebudians (XI, 76).

Alcine holding Roger locked up in his palace condenses the figures of Circe (like her ancient model, she transforms her lovers into plants and animals) and Morgana, who imprisoned Lancelot17. The maid Logistille, meanwhile, evokes Logistique, the allegorical fairy from Francesco Colonna's Songe de Poliphile : Ariosto's fleeting evocation of the hanging gardens of Logistille's palace, which the woodcut of the Valgrisi edition has not forgotten, echoes the abundant descriptions of Logistique's gardens and their illustrations, right from the first editions.

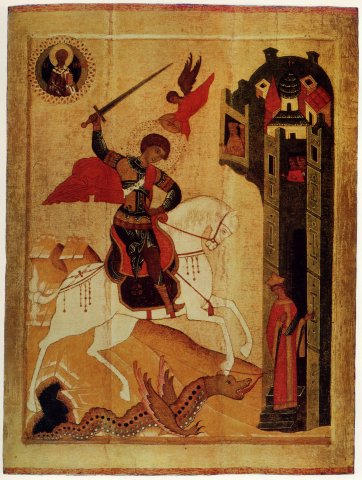

Saint George slaying the dragon, first half or mid-sixteenth century. 89.2x67.2x3.3 cm. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, inv. no. 168. Basswood panel. From the church in the village of Litvinovo, Chenkursk district, Arkhangelsk region.

Finally, the final scene of the fight against the orca takes in both the medieval battle of St. George slaying the dragon to save the daughter of the king of Silcha18 and Perseus' ancient fight to deliver Andromeda, victim of the presumption of Cassiopeia, his mother, who had claimed to be more beautiful than the Nereids19. The iconography of Saint George develops as a triumphal representation in Byzantine and Russian icons (the rider above the dragon), in Italy with Paolo Uccello20 and Carpaccio21, which turn it into a knightly combat (the knight facing the dragon), then staged by Raphaël22 in a theatrical space, the princess in the vague space23 of the landscape at the dramatic moment of the fatal blow. As for Perseus, Piero di Cosimo painted the story in Florence at the same time as Ariosto was writing his work in Ferrara, in a painting whose narrative style is so close to our illustrative engravings that it may have served as the cover for a recent edition of Roland furieux24. The iconography of Perseus would make a fortune : we find it under the brush of Veronese, Rubens, Van Dyck, Rembrandt, Coypel.

Ariosto, /// Roland furieux, illustrated by Gustave Doré, Paris, Hachette, 1879, in-folio, Résac Smith Lesouef R-6551.

This brief overview gives an idea of the extent of the contamination of medieval and ancient heritage in Roland furieux. One cannot speak of a source in the strict sense : there are no explicit references in Ariosto (or these references are more often than not false leads25) and it is impossible to establish exactly what he may have read and seen. Rather, it's a matter of establishing the cultural nebula in which the text bathes and understanding what kind of relationship the text has with this nebula.

Piero di Cosimo, Persea delivers Andromeda, oil on wood, 70x123 cm, Florence, Uffizi Gallery, inv. 1890, no. 1536. According to Vasari, the work was executed around 1515 for Filippo Strozzi. Exhibited in the Tribune as early as 1589, it would allude to the return of the Medici to Florence in 1512.

We have identified the two competing principles of text composition, the principle of superposition and the principle of reversion : we will show how these principles regulate the import of cultural heritage in the same way as they order, within it, the system of territories.

Narrative device of Roland furieux

The temptation is great to reduce the phenomenon to one word : syncretism. Doesn't Ariosto mean to amalgamate into a single textual material the different cultural strata that come together at the time he writes, the material of ancient myths, medieval tales of the chivalric and courtly world, and more recently tragic stories, short stories, as well as allegorical speculations ?

The phenomenon is, however, very different from Alexandrian syncretism, which attempted to coordinate all myths into an ever more continuous and complete story. Ancient syncretism is an art of transition, of conciliation, of passage.

The practice of superimposition is quite different. Let's return to the engraving to illustrate our point : we noticed how the boats on the right, the " finistères " on the left constituted two chains of figures tending to converge towards the vanishing point of this strange cartographic landscape. On the other hand, the multiplication and scattering of the figures and boats at the top of the image seems to counterbalance the unifying, syncretic movement induced by perspective : the system of territories is a system of ruptures.

The image translates the double, contradictory movement of the text : the movement of the song is both a movement of integration, of reducing proliferating stories to a single narrative matrix, and a movement of dissemination of attention, of dispersion in space, of thwarting the linearities of history. We run towards a vanishing point, but the flight multiplies and dissolves the point(s). This double movement of focusing and dispersing the narrative, of dissipating and reviving the event, is the driving force behind the narrative device.

This narrative technique is thematized : the stories that follow one another for the reader to superimpose are stories of escape. Biren flees Olympe, Roger flees Alcine, Angélique flees Roger.

The superimposition of these stories highlights a common narrative matrix : on one side we find the lover on her island, Olympe abandoned, Alcine tied to her eponymous territory, Angélique chained to her rock. On the other, a knight floats on the waters: Biren sails away in a boat, with no return; Roger flees in a boat, but turns back to fight ; /// Roger again takes the initiative in the fight against the orca, from his hippogriphe.

.Let's denote the narrative matrix of Canto X by a formula : Facing the lover on her island, a knight floats on the waters. The narrative matrix itself delivers no meaning. It is its implementation in the narrative device that orients the meaning of the story. Here, the meaning of the repeating narrative motif begins by inverting itself: the weak Olympus, figure of the sacrificed Ariadne, becomes the fearsome Alcine, figure of a Circe whom only a bitter battle can reduce to mercy. Angélique seems to condense these two opposites, first exposed to the rock, accentuating Olympe's position to the point of excess, then fleeing thanks to the ring of invisibility. Until then, freedom of flight had been a male prerogative. Angélique's story thus feeds on Olympe's, which she parodies, and Alcine's, which she turns on its head.

As for Biren, pale and cowardly parody of Thésée26, operating a symmetrical reversal of that of Olympe in Alcine, he first heroes himself in an allegorical novel Roger : the former's shameful flight becomes for the latter (not without irony) a journey from the island of vices, inhabited by Alcine, to the island of virtues, where Logistille reigns. In the final episode, Roger, mounted on his hippogriphe and slaying the orca, condenses the two antagonistic figures of Biren and the first Roger, and cuts across the two cultural traditions they embody : as a good courtly knight, he nobly and gratuitously defends an unknown lady in peril as an infamous bribe-taker, he attempts to rape her his battle is edifying in the manner of Saint George's and terrifying in the manner of Perseus's.

.Lodovico Ariosto, Orlando furioso, Paris, Plassan, 1795. Copper engraving for Canto XI, drawing by C. N. Cochin, engraving by N. Ponce, signed and dated 1776. From his boat, Roland drives an anchor into the orca's mouth to pull it to shore, exterminate it and deliver Olympus.

The inversion of meaning, then the inclusion of contrary meanings, are characteristic of a narrative device worked by parody. Here we find the two contradictory tendencies of the Argo effect: the logic of innutrition, which encompasses and totalizes contradictory meanings, and the logic of distancing, which suspects, modalizes, ironizes, to the point of inverting the meaning of what it claims to report. This contradiction has repercussions at the symbolic level, the upper level of the narrative device: courtly values based on service to the Lady and heroic, chivalric values based on prowess in combat, are overturned into their brutal, trivial or absurd opposite, the irrepressible, immoral surge of desire, the inversion of roles between man and woman, the absurdity of a heroic combat that loses all meaning. Courtesy and anti-courtesy are then fused into a single system, which can be defined as a system of symbolic duplication.

The hollowing out of the narrative matrix

The story always tends towards perfecting, but also hollowing out, the narrative matrix. The Argo effect is a logic of the shell.

Rembrandt, Andromeda, painting on wood, 34.5x25cm, 1631, The Hague, Mauritshuis.

We have seen how Song X tends towards the totalizing episode of the fight against the orc, where all the contradictory ingredients of the preceding episodes are brought together. But if we take /// If we take into account the end of Canto X and the beginning of Canto XI, we discover a second battle: if Roger delivers Angélique in Canto X, failing to find Bradamante, to whom he is promised, Roland, in Canto XI, also fights the orc in the hope of saving Angélique, who is indeed his Lady. But it's no longer Angélique, it's Olympe, whom the Ébudiens have tied to the rock after the knight with the hippogriphe freed the Queen of Cathay, so Roland, like Roger, is not fighting for the right Lady. The two episodes are out of sync, and for this reason degenerate very quickly the valiant Roger manifests his desire for rape the chaste Roland disposes as quickly as possible of the cumbersome prize of his useless victory, the sublime, blushing body of this Olympus who unwillingly blocks his path to Angelique for the second time.

.Arioste, Roland furieux, translated by A.-J. du Pays, Hachette, 1879. Introductory engraving of Canto XI, signed, drawing by G. Doré, engraving by Ch. Barbant. After killing the killer whale on shore, Roland comes to deliver the naked Olympe.

The superimposition of the two sequences reveals the fundamental scene that will never take place, Roland's fight for Angelique, the qualifying test for which the Lady would be the prize. But the first time the combatant, the second time the victim, are not the right ones. These shifts and evasions ensure narrative dissemination (the narrative fails to crystallize any scene) and blur the symbolic stakes: it's the chivalric performance itself that, by splitting into two (Roland superimposed on Roger), parodies itself and slides into sublime, fairy-tale nonsense. Roger and Roland, faced with the killer whale and the girl on the rock, form a tableau, like figures of a glory for nothing, a glory whose meaning and justification flee forward.

.This obviousness, this nonsense will ensure not only the survival, but the formidable posterity of Roland furieux, which itself becomes, in classical culture, a heritage monument. We've seen how heritage entered and then circulated within the text, organizing a system of territories. But the text itself becomes a heritage object, and can in turn be exploited by other cultural productions. The Argo effect continues its work not upstream, but this time downstream of the work.

.Just as the repair of Theseus' boat infinitely completes an empty shell, whose meaning is both immediate and elusive (it's the great Theseus, but what does Theseus actually mean ?), just as the Argo effect at work in Roland furieux constitutes patrimonial territories, delimits spaces of memory and culture but the meaning, the very matter of these territories is elusive. One might even suppose that they derive all their value from this paradoxical, luminous vacuity.

This is not to say that Ariosto's text, or the paintings, various rewritings, operas and performances to which it has given rise, are meaningless. But we will distinguish the heritage object that constitutes the Roland furieux taken as a narrative device from each of the investments of meaning to which this or that work has given rise. Each time, the sumptuous ship is summoned, supplemented and hollowed out a little more to signify an entire culture, to designate a heritage totality that is increasingly encompassing, increasingly vague and disseminated, increasingly detached from any referent this totality is anything but insignificant ; but a meaning cannot be attributed to it.

In fact, Ariosto's text contains within itself its own end, and programs the impossibility of its monumentalization. The circulation of precious objects in the text, particularly weapons (the Balisarde sword, /// Durandal and Hector's thousand-year-old weapons) but also mythical horses (Frontin, Bayard, Bride d'or), which are won and lost in successive adventures and battles, is well presented as a circulation of heritage, inscribing a permanence of cultural memory amid the uncertainty of battles and the twists and turns of the narrative.

.But precisely because they circulate, heritage objects are under threat. We need to be able to assign them a fixed territory, to monumentalize them. The word monument is never uttered in Roland furieux27. Merlin's tomb in Canto III, Merlin's fountain deciphered by Maugis in Canto XXVI, the gallery of paintings contemplated by Bradamante in Canto XXXIII are anti-monuments : Ariosto resorts to the performance of epic ekphrasis to commemorate the past by describing objects that prophesy the future. Caught between the times of fiction and Ariosto's own time, this patrimonial future-in-the-past that the poet had actualized for his contemporaries was destined to die for posterity. Every monument, at the moment it deploys the memory of culture, announces its irremediable death.

Discography

Antonio Vivaldi, Orlando furioso, I solisti veneti, Claudio Scimone, Erato, 1978 (Marilyn Horne, Orlando ; Victoria de Los Angeles, Angelica ; Lajos Kozma, Medoro)

George Frideric Handel, Orlando, The Academy of Ancient Music, Christopher Hogwood, Decca/L'Oiseau-lyre, 1991 (James Bowman, Orlando ; Arleen Auger, Angelica Catherine Robbin, Medoro) Alcina, Les Arts florissants, William Christie, Erato, 1999 (Renée Fleming, Alcine ; Natalie Dessay, Morgane Kathleen Kuhlmann, Bradamante). There is also a Ruggiero and a Bradamante, available on disc.

Jean-Baptiste Lully, Roland (Versailles, 1685), Les Talents lyriques, chœur de l'opéra de Lausanne, Christophe Rousset, Ambroisie, 2004 (Nicolas Testé, Roland ; Anna-Maria Panzarella, Angélique ; Olivier Dumait, Médor)

Proposed groupings of texts

L'amante abandonnée

-

Virgil, Aeneid, IV, 584-705 (Dido's death)

-

Catullus, Poesies, 64, 50-266 (description of Thetis's bridal veil, representing Ariadne abandoned by Theseus)

-

Ariosto, Roland furious, X, 10-34. In Italo Calvino's edition, " Olympe abandonnée ", GF, pp. 101-110

-

Le Tasse, La Jérusalem délivrée, XVI, 35-75 (Renaud quitte Armide), LP, " Bibliothèque classique ", trans. Jean-Michel Gardair, pp. 515-528 (illustrated edition, very fine translation)

The hero slaying the dragon

-

Jacques de Voragine, La Légende dorée, " saint Georges ", GF, tome I, p. 297-301

-

Ovid, Metamorphoses, " Andromeda ", IV, 663-764, folio p. 157-160

-

Philostratus, La Galerie de tableaux, " Persée ", I, 29, La Roue à livres, Les Belles lettres, p. 57-58

-

Ariosto, Roland furieux, X, 92-XI, 77. In Italo Calvino's edition, " Les captives de l'île des pleurs ", GF, p. 111-120

-

Alain Robbe-Grillet, Angélique ou l'enchantement, Minuit, 1987, p. 192-195 (Angélique at the rock facing Roger's spear, paradigm of sexual fantasy)

Love on the margins of war

-

Ariosto, Roland furieux, XIX, 16-42. In Italo Calvino's edition, " Cloridan et Médor ", GF, pp. 163-177 (the most famous stanzas, where Médor engraves the names of the two lovers on the trees, are unfortunately missing)

-

Le Tasse, La Jérusalem délivrée, XVI, 1-26 (Renaud in Armide's garden) and XIX, 102-117 (Herminie cares for Tancrède), LP, pp. 503-510 and 622-628

-

Flaubert, L'Éducation sentimentale, III, 1, GF, p. 392-403 (Frédéric and Rosanette in Fontainebleau during the June 1848 insurrection)

-

Alain Robbe-Grillet, Angélique ou l'enchantement, Minuit, 1987, p. 136-145 (the death of Simon and Carmina)

The hero's madness

-

Sophocles, Les Trachiniennes, 748-812 (Hyllas tells Dejanira of the effects of Nessus' tunic and the death of Lichas)

-

Seneca, Hercules on the Œta, 817-

-

Philostratus, La Galerie de tableaux, II, 23, " Héraclès furieux ", ed. cit. p. 101-103

-

L'Arioste, Roland furieux, XXIII, 100-121 (Roland discovers the inscriptions) ; XXIII, 122-136 (beginnings of madness : Roland strips naked and uproots the trees) XXIV, 4-14 (naked Roland terrorizes the countryside). In Italo Calvino's edition, " La folie de Roland ", GF, p. 199-209

Notes

. ///We can contrast, for example, Parisian architecture as it appears in Zola and the allegorical architectures of the Songe de Poliphile, or the antique ones of the Antiquités de Rome. Zolian architecture is above all real humanist architectures are above all symbolic.

" The hic et nunc of the original forms the content of the notion of authenticity, and on this rests the representation of a tradition that has handed down to the present day this object as having remained identical to itself. The components of authenticity reject all reproduction, not just mechanized reproduction. [...] What withers in the work of art, in the age of mechanized reproduction, is its aura." " (Walter Benjamin, " L'œuvre d'art à l'époque de sa reproduction mécanisée ", 1936, Ecrits français, Gallimard, Bibliothèque des idées, 1991, pp. 142-143.)

Thomas Pavel, The Art of Remoteness. Essai sur l'imagination classique, Gallimard, folio essais, 1996.

Plutarch, " Theseus ", Les Vies des hommes illustres, grecs et romains, comparées l'une à l'autre, par Plutarque de Chaeronée, translatées premièrement de grec en françois par maistre Jacques Amyot,.... et depuis en ceste troisième édition reveues... par le mesme translateur..., Paris, Vascosan imprimeur du roy, 1567, Club français du livre, 1967, t. I, § XXVII, p. 19. See also " Thésée ", Vies parallèles, translation by Anne-Marie Ozanam, Quarto Gallimard, § XXIII, p. 76. These two editions will henceforth be referred to by the names of the translators, i.e. Amyot and Ozanam respectively.

Aristotle, Constitution of Athens, XIII, 2.

Jacques Derrida, De la grammatologie, Minuit, 1967, II, 2, especially pp. 226-227.

Claude Lévi-Strauss, La Pensée sauvage, Plon, 1960, p. 27.

Mikhail Bakhtin, La Poétique de Dostoïevski, 1963, French translation by Isabelle Kolitcheff, Seuil, 1970, chapter IV, pp. 151sq.

Ariosto, Roland furieux, presented and narrated by Italo Calvino, Turin, Einaudi, 1970, French translation of Ariosto by C. Hippeau and of Calvino by Nino Frank, Garnier-Flammarion, 1982. The complete text of Roland furieux, trans. Francisque Reynard, has since been published by Gallimard, Folio classique, 2 vols, 2003. These paperback editions reproduce nineteenth-century prose translations, which are highly readable but sometimes quite far removed from the original text. Two new translations have also recently appeared (bilingual editions) : one by André Rochon, Les Belles Lettres, 4 vols., 1998-2002 (juxtalinear translation), the other by Michel Orcel, Seuil, 2 vols., 2000.

The engraving we reproduce below is bound in an edition dated 1562. However, the Montpellier municipal library has an illustrated Valgrisi edition dated 1560 (call no. 37511 RES), with the same set of woodcuts. An edition illustrated with woodcuts, Venice, Valgrisi, 1558, was reported for sale in February 2003. According to J-Ch Brunet's Manuel du libraire et de l'amateur de livres (ed. 1860), the first Valgrisi edition dates from 1556. The unsigned engravings are said to have been executed after drawings by Dosso Dossi. Ariosto was his friend and employed him to make these drawings, while he celebrated him as one of the most distinguished artists of his time. The engravings in this series are exceptional for their size and the finesse of their details, which are extremely difficult to execute on wood. Their exemplary status is attested to by the fact that they served as models for other series of engravings, such as those on copper in the same format by Girolamo Porro (Franceschi edition, Venice, 1584, Bnf Résac yd 396 call number) as well as a series of vignettes on wood, in a smaller format (Valvassori edition, Venice, 1566, BM Montpellier 10948RES call number).

The French trasncription of the characters' names varies from edition to edition : Bireno is sometimes called Biren, sometimes Birène ; Olimpia, sometimes Olympe, sometimes Olympie, and so on.

The notion of narrative device is extrapolated from that of scenic device, defined in La Scène. Literature and visual arts and in La Scène de roman. Méthode d'analyse. The scenic device matches a concrete space, whose layout makes sense, with a symbolic stake abstractly echoing the same layout. The narrative device works on the same kind of dispositions, but instead of superimposing them in a single scene, it transposes them throughout a narrative. In this case, we don't speak of a disposition, but of a motif.

The notion of actantial pattern was developed by A. J. Greimas, Sémantique structurale, Larousse, 1966, PUF, 1986, based on the work of Vladimir Propp, Morphologie du conte, 1928, 1969, French transl. Seuil, 1965 and 1970. But if the Greimasian semiotic model is fundamentally syntactic and Aristotelian (presupposing a universal structure of language that would also be that of any narrative), the narrative matrix, operating by translations of territories, is a visual and topographical model with no common originary model.

Greimas, following Propp, speaks of function. But under their matrix-like appearance, these functions are in fact no more than paradigms whose combination and syntagmatic sequence constitute the narrative, from the point of view of its linguistic formalization. Unlike a function, which may occur only occasionally, a motif is a configuration of characters, movements and situations that are linked to each other. /// repeats : the critic deduces the objective existence of a motif from the evidence of its repetition.

Ariosto and his illustrators will again resort to the representation of the dream in Canto XXIII, when, in Tristan's castle, Roger appears to the sleeping Bradamante to assure her of his fidelity. Bradamante, worried about a possible betrayal by the faithful Roger for Marphise, is the symmetrical figure of Olympe sleeping untroubled while the unfaithful Biren betrays her for the daughter of Cimosque.

Catullus, LXVI, 50-266.

Odyssey, X, 210-223 and The Death of King Arthur, trans. Marie-Louise Ollier, 10-18, 1992, §§ 51-52, pp. 99-100.

Jacques de Voragine, La Légende dorée, GF, t. I, pp. 297-301.

Ovid, Metamorphoses, IV, 670-739.

There are two versions, one in the Jacquemart André Museum in Paris, the other in the National Gallery in London.

Cycle of San Giogrio degli Schiavoni, Venice, Scuola di San Giorgio.

Musée du Louvre and Washington, the National Gallery of Art.

On the notion of vague space, see S. Lojkine, La Scène de roman. Méthode d'analyse, A. Colin, 2002.

Ludovico Ariosto, Orlando furioso, A cura di Lanfranco Caretti, Presentazione di Italo Calvino, Torino, Giulio Einaudi editore, 1992, Volume primo.

For example, Canto X opens with a snide reference to Helen of Troy, who can have served as a model for neither Olympus (abandonment is an antithesis of abduction) nor the fleeting evocation of Cimosque's daughter: " dico ch'Olimpia è degna che non meno, / anzi più che sé ancor, l'ami Bireno : // e che non pur non l'abandoni mai / per altra donna, se ben fosse quella / ch'Europa et Asia messe in tanti guai ", I say that Olympe was worthy that Biren loved her, not less, but even more than himself, and that not only would he never abandon her for another, even for the one who put Europe and Asia in such chaos... (X, 2-3). Helen is thus evoked for nothing, gratuitously, while Ariadne, Andromeda and the daughter of the king of Silcha are neither mentioned nor even alluded to.

Theseus betrays Ariadne but saves Athens Biren's betrayal is both amorous and political. Theseus delivers the prisoners of the labyrinth, while Biren is the prisoner who is rescued.

It appears in French translations, to translate sepoltura, the tomb.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « L’effet Argo : le système des territoires dans le Roland furieux de l’Arioste », Patrimoine et littérature au collège et au lycée, dir. Hélène Waysbord, Scérén, CRDP Franche-Comté, 2007, p. 123-153.

Arioste

Archive mise à jour depuis 2003

Arioste

Découvrir l'Arioste

Épisodes célèbres du Roland furieux

L'île d'Alcine

Angélique au rocher

Bradamante et les peintures

La folie de Roland

Angélique et Médor

Editions illustrées et gravures

Principales éditions de l ’Arioste

Les trois territoires de la fiction

L’effet Argo

Gravures performatives

Gravures narratives

Gravures scéniques