The term "figure" has its origins in the field of plastic art. However, German philologist Erich Auerbach analyzed its use in Western literature1. In his view, the notion of the figure represents a convergence between two traditions: the Greek tradition and the Judeo-Christian tradition. While the Greek tradition contributed to the allegorical dimension, the Church Fathers adopted this approach to interpreting biblical texts. Thus, the term "figure" also encompasses a hermeneutical dimension, designating a literal meaning that leads to a spiritual meaning through a symbolic approach. The evolution of the word "figura" enabled Auerbach to develop a "figurative" method of interpretation that encompasses two fundamental dimensions: the literary and the exegetical.

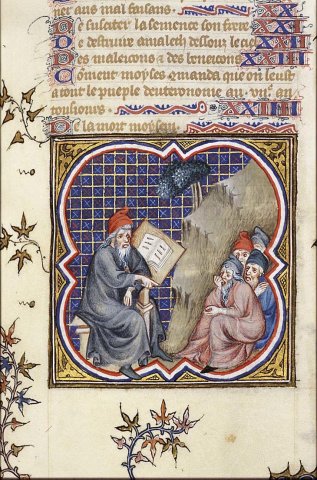

.Moses, as a Jewish prophet and presumed author of the Old Testament2, lends himself particularly well to a "figurative" interpretation. In the allegorical tradition of Christianity, Moses is seen as one of the prefigurations3 of Jesus Christ. Old Testament episodes, through their resonance with New Testament realities, allow us to anticipate symbolic meaning in the exegesis of the literary work's author. This approach also reveals a deep spiritual link between Moses and the Bible.

Petrarch4, in describing Moses as a great man, appears as the precursor of a new type of cultural construction due to Renaissance humanism. His treatise De vita solitaria5 praises Moses as one of the great figures of the solitary life, alongside pagan heroes, biblical figures and Christian saints. In the second version of his work De viris illustribus6, Petrarch adopts the biographical form to reconstruct the lives of Roman heroes and biblical figures. Moses occupies a central position as the last and most prominent of the eight biblical figures portrayed here.

A figure of sacred history, the figure of Moses undergoes a transformation into a great man within literary texts thanks to the work of Petrarch. Our aim is to examine the image of Moses in Petrarch's writings by adopting the figurative point of view, namely making this Hebrew Old Testament figure a prefiguration, through his two treatises, exploring the combination of two dimensions: the literary dimension and the exegetical aspect.

The "figurative" interpretation

Erich Auerbach explores the history of the evolution of the term "figura" in Western culture, taking an etymological approach. This evolution of the word "figura" followed two distinct branches: one in pagan culture and the other in the Christian world. In pagan culture, the term first took on the meaning of "copy", then entered the realm of rhetoric. Auerbach explains Quintilian's notion of the "rhetorical figure" as follows:

He separates tropes from figures: more specific, the trope refers only to the non-appropriate use of words and turns of phrase; on the other hand, any shaping of discourse that departs from common, direct usage is a figure7.

In the Christian world, on the other hand, "figura" has been incorporated into the field of hermeneutics. In early Christianity, the use of the term gave rise to a debate between historical and allegorical interpretation of the Old Testament. Tertullian, one of the earliest Church Fathers, attached great importance to the literary and historical value of the texts, while Origen, a Greek theologian from Alexandria, favored an allegorical and moral interpretation. Augustine of Hippo succeeded in reconciling these two perspectives, redefining the three levels of meaning associated with the concept of "figura": first, that of "Jewish law or history", second, that of the "Incarnation" of Christ, and finally, that of the "future realization of promised events8". Thus, in pagan culture, "figura" refers more to a literary value, while in the Christian world it takes on an exegetical dimension encompassing several levels of meaning in the allegorical tradition of Christianity.

Thus, the evolution of the term "figura" offers Auerbach the opportunity to develop a "figurative" method of interpretation, firmly fusing Western Christian tradition with pagan culture. In his application to literary analysis, Auerbach refers specifically to his study of Dante's Divine Comedy.

This "figurative" interpretation provides an analytical tool for exploring the convergence between Christian theology and the pagan world. On the one hand, as Hayden White points out, the "figuratism" model proves particularly useful in "the study of literary styles and genres9", illuminating generic links between literary texts. On the other hand, this "figurative" interpretation remains relevant for deciphering the process of encounter between Christian theological substance and the pagan universe, profoundly influencing the evolution of literature in the Renaissance period. This dynamic highlights how Christian theology was "secularized and recontextualized10".

"Figurative" interpretation comprises two essential aspects: the literary and exegetical dimensions. The literary dimension encompasses genre and style, while the exegetical approach incorporates the rich tradition of Christian allegorical interpretation as well as the author's personal vision. In other words, the author selects a specific episode from the life of a biblical character, then skilfully incorporates it into his text, taking into account literary genre and style, thus giving the character a whole new meaning. The final image not only faithfully reproduces the original biblical image, but composes a free interpretation that fuses both an exegetical dimension and literary invention.

We plan to use this method of interpretation to examine the representation of Moses in Petrarch's works. In the first place, Moses occupies a central position as the author of the Old Testament Pentateuch, also distinguishing himself as prophet, lawgiver and liberator in the history of Israel. He is of particular importance not only in Christian exegesis, but is also presented by Paul as a prefiguration of Jesus in the Old Testament, and the early Church Fathers regard him as a spiritual model for Christians11. He was also introduced into Roman society by Jews resident in Alexandria, becoming a notable figure in Judeo-Christian literature12. Petrarch stands out as the precursor of the Renaissance by reinterpreting Moses in the context renewed by him of the encounter between Christianity and pagan culture13.

The two treatises, De vita solitaria and De viris illustribus, examine various aspects of the character of Moses from a dual perspective, both literary and exegetical. By analyzing the representation of Moses in these writings by Petrarch, we can thus apprehend the operation of the figurative mode of interpretation within the work of this Renaissance author.

De vita solitaria : Moses as solitary

TheDe vita solitaria (La Vie solitaire) is a moral treatise by Petrarch addressed to his friend Philippe de Cabassole, bishop of Cavaillon. In this work, Petrarch encourages his reader to distance himself from everyday concerns and adopt a life devoted to study and solitary meditation. Composed from the spring of 1346 to around 1370, the treatise is structured in two distinct parts: the first outlines objections to the idea of ideal solitude, while the second presents illustrious personalities who have adopted this way of life. According to Kenelm Foster, this humble work represents "a new phase" in which Petrarch speaks "explicitly as a Christian14". In this work, Moses is presented as a great biblical figure embodying the practice of solitude. Episodes from his life are used as examples illustrating the benefits of "the solitary life" according to Petrarch. Moses guides us through the dialogues between Christian tradition and the pagan world in this treatise, offering a spiritual insight into Petrarch's world.

First of all, Moses emerges as one of the biblical figures who embraces solitude, and his role as prophet highlights the sacred dimension of this state. In Book I, Petrarch evokes the episode of Moses crossing the Red Sea to emphasize the constant presence of God, a central theme of solitary life. Even before formulating a verbal prayer, Moses' silent cry reaches the divine ear: illustrating the idea that God "hears us even before we speak15". In this way, Moses becomes an inspiring example of communion with God in the midst of solitude. In Book II, Petrarch provides a brief biography of Moses as a prophet, calling him "familiar with God16" and highlighting his spiritual intimacy as well as his exemplary life in solitude in the desert.

Petrarch strives to demonstrate that Moses acquires the ability to perform miracles and win victories through solitude. His narrative highlights two miraculous events in the desert: the descent of nourishing manna from heaven, and the blow to the rock that brings forth water17. The people of Israel and their adversaries become, in a way, the context for Moses' personal life. However, behind these miraculous victories and communication with God, solitude remains at the heart of everything. Petrarch concludes that "solitude is loved for its divine blessings and exchanges, it is prized for its great assemblies of angels18!" Moses' prophetic experience highlights the close link between solitude and supernatural communication with God. As Armando Maggi points out, Petrarch's new conception of "solitude" involves more "an intimate dialogue with a friend who pursues the same intellectual and spiritual ideals 19".

In addition, Moses' death symbolizes the conclusion of a life in solitude, as God orders him to ascend Mount Abarim and die there in solitude20. For Petrarch, Moses' "glorious death" means that solitude is destined for him "at the moment of departing from men21". Thus, Moses' prophetic experience illustrates how solitude fosters uninterrupted communication with God while symbolizing the concept of intimate dialogue with a friend sharing similar intellectual and spiritual ideals. This solitude, lived in communion, represents the glorious life of an exceptional man.

Secondly, the life of the prophet Moses demonstrates that communion in solitude is an active process. Petrarch seeks to dispel the false notion of solitude as a passive state by using the prophet's example to show that it involves active communication with God.

Petrarch lists the miracles of three biblical prophets living in solitude: Moses, Elijah and Elisha. He points out that these three prophets were "active in their isolation and were accompanied in their solitude22", thus quoting St. Ambrose. Then he offers specific examples of conversations with God in solitude for each prophet. Moses' experience includes three major aspects: conversing with God as with a friend, crying out to God and triumphing over his enemies by raising his hands. These three actions demonstrate that solitude is active communion.

After recounting the experiences of these three prophets, Petrarch begins to demonstrate how the Roman hero Scipio the African reproduces their actions, even without knowledge of these prophets. According to Petrarch, the crucial point is that "this imitation" of biblical solitude does not, as a rule, deprive human actions of their share of glory and fame23. In other words, imitating the solitary life of the biblical prophets also confers a distinct fame.

Thus, Petrarch lays down a universal rule: he aspires to an active and fruitful solitude, a leisure that, far from being inactive or vain, engenders beneficial benefits for a large number of people24. Petrarch thus elevates solitude, which he associates with biblical figures, to the status of an indirect model for Roman heroes and, by extension, for great men the world over. In other words, the solitary lifestyle he advocates is positive, useful and applicable to all, and biblical texts serve to establish this particular ideal of solitude.

Thirdly, Moses is described as a liberator who opened the Red Sea to save the people of Israel. By introducing his friend, the bishop of Cavaillon (the recipient of this brief treatise), to the mountain at Vaucluse as the holy place of solitude, Petrarch draws a comparison between the former bishop of Cavaillon, Véran, whose tomb lies in the mountain at Vaucluse, and Moses, the liberator of the people of Israel.

Petrarch draws a comparison between the former bishop of Cavaillon, Véran, whose tomb lies in the mountain at Vaucluse, and Moses, the liberator of the people of Israel.

Petrarch sets out to convince his friend to join the sacred place of solitude by telling the story of the mountain at Vaucluse. This place derives its sacredness from the tomb of Bishop Véran, who paved the way for others in search of the solitary life. After triumphing over a dragon, he erected a small sanctuary in honor of the Virgin Mary and furnished his modest cell. Véran is thus a pioneer, having made this mountain accessible by cutting the hard rock with his own hands25. Petrarch even recounts a miracle: after Véran's death, his mantle carried his body to the place where he wished to be buried. According to Petrarch, Véran's mantle performed a prodigy comparable to that of Moses' staff opening the Red Sea26.

Through this comparison, Véran's role is likened to that of Moses for the people of Israel, the bishop of Cavaillon becoming the liberator of individuals aspiring to the solitary life. His mantle is invested with a divine anointing, enabling his body to return to the holy land of solitude, the sacred mountain of Vaucluse. This analogy is intended to glorify the miraculous effects of solitary life and confer a mysterious aura on the mountain, establishing a sacred link with solitude. This perspective could be linked to Petrarch's personal experience at the summit of Mont Ventoux27. As Jean-Claude Margolin explains, the "mountain metaphor" often symbolizes "the ladder of perfections28". Petrarch thus confers a spiritual and mystical value on the solitary life, evoking the supernatural experience of Bishop Véran. This story can be interpreted as a Christianization of Petrarch's "literate solitude29", bringing together a community in search of intellectual and spiritual perfection.

The example of Moses in Petrarch's perspective on solitude illustrates a profound conception of the solitary life. Solitude, he argues, is both a form of active, intellectual and spiritual communication, while also serving as a source of inspiration for mysterious actions. This experience is not confined to biblical prophets, but also extends to Roman heroes, meaning that any individual can draw inspiration from it. Through the image of Moses, Petrarch invites us to embrace the ideal of intellectual life, which consists of a small group sharing and developing in solitude. However, this solitary life also contains a spiritual aspect. The example of Moses' personal mystical experience can be interpreted as a metaphor, or understood as a desire for mystical experiences. After all, Petrarch himself aspired to a mystical experience similar to that of St. Augustine. Nevertheless, Petrarch's conception of solitary life is more akin to a humanist ideal. As Dolora Chapelle Wojciehowsk points out, Petrarch's imagination of "a small community of friends united in intellectual and spiritual activities" differs markedly "from medieval religious communities30". In this way, the image of Moses transcends his role as biblical prophet to become a symbol of the solitary life, accessible to the whole of humanity.

De viris illustribus: Moses as a Christian hero

In the De viris illustribus, Petrarch writes a detailed biography of Moses, pursuing the goal of offering inspiring examples to encourage his readers to aspire to human greatness31. In his lengthy preface, he sets out his reasons for undertaking this task, noting that his contemporaries lack "both the will and the capacity for greatness32". At the same time, he highlights the distinction between those who are lucky and truly illustrious men. Wealth and power can result from chance, while illustrious men emerge thanks to the "glory" and "virtue" they have cultivated33.

However, the outline of this work reflects Petrarch's evolving conception of heroes. Early in his career, he envisaged creating an epic and a biography serving as an "apology for Rome34". Thus, the first version of the De viris illustribus in 1337, conceived as a complement to the epic Africa, began with the biography of Romulus and was structured around a plan centered on the Roman Republic. Over time, this series expanded to include heroes of "all ages35" in the second version. However, it's the second version that remains the best-known, and that's what we'll be focusing on. Thus, the overall structure of the work encompasses twelve characters, eight of whom are figures from the Bible: Adam, Noah, Nimrod, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph and Moses.

Petrarch highlights two distinct dimensions in the image of Moses: glory and virtue. Glory is associated with the grandeur of a Roman hero, drawing his military might from the divine presence. Moses is presented as a hero who uses miracles to win his battles. At the same time, virtue refers to the Christian traits present in Moses' character, such as patience and love. Thus, Moses is depicted as both a military leader and a spiritual guide, compared by Petrarch to a shepherd leading God's flock.

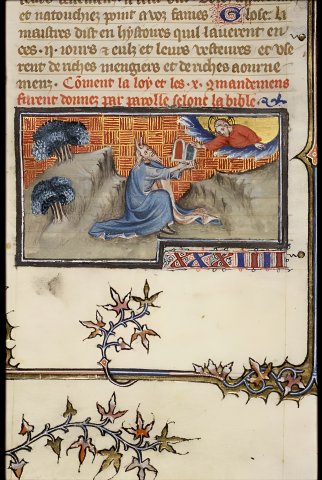

The image of Moses is mainly constructed from biblical texts, where Petrarch discards supernatural elements to present him as an extraordinary man prospering despite difficult trials. To portray Moses as an exemplary leader facing hardship, Petrarch prefers to follow the narrative framework of Jerome's Vulgate36 and ignores the anecdotes of the historian Flavius Josephus. Petrarch's depiction of Moses with horns receiving the tablets of the Law reflects this admiration for Jerome.

The poet deliberately omits Moses' success in Egypt, as well as his wisdom gained in the Egyptian palace. Nor does he relate the anecdote of "the love of a daughter of the king of the Ethiopians for Moses", present in Josephus and Virgil37. These legendary elements are overlooked by Petrarch to avoid Moses being perceived as a man of wealth. Instead, the emphasis is on Moses' difficulties in leading the people through the desert, and the text is painstakingly devoted to describing the individual challenges faced by the Jewish leader during the collective journey through the wilderness. Key events, such as the turning of bitter waters into fresh, the war with the Amalekites, the giving of the Tables of the Law, as well as the people's revolts against Moses, are all carefully preserved in the narrative.

Exegetically speaking, Petrarch doesn't particularly dwell on allegory to establish a link between Moses and Jesus. He concentrates on the human aspect of Moses, using him as an example to recount the evolution of a great man with the aim of inspiring emulation and learning in his readers.

As Petrarch expresses it in his preface, illustrious men are "the products of glory and virtue38". The trials endured by Moses reveal his unique glory and precious virtues. The author uses several key events to illustrate Moses' rise39, highlighting both his glory and his moral character. The story of Moses' life is structured around four major trials, each closely emphasizing the link between glory and virtue, although each event highlights different aspects of his personality. For example, the crossing of the Red Sea highlights Moses' ability to perform miracles, demonstrating his strength, synonymous with glory. By contrast, the ordeal in the desert highlights Moses' virtue in the face of a rebellious people. Throughout his life, Moses' skills and character continue to grow.

Moses' glory manifests itself through two key aspects: his ability to defeat his enemies through miracles, reflecting his strength, and his intimate bond with God.

As Israel's liberator, Moses possessed a singular power that enabled him to challenge his adversaries by performing prodigies40. Petrarch emphasizes Moses' unique responsibility among the people. As God's "interlocutor"41, Moses soothes human complaints and passes on divine commandments, a charge that also constitutes his unique glory. The episode of the battle against the Amalekites illustrates this singularity of Moses' glory, with the repeated use of the term "alone": "the bare hands of a single old man" or "himself all alone42". This is particularly evident in the episode of the crossing of the Red Sea, where Moses' combat skills come to the fore. As the people of Israel are pursued by the enemy, the "lifting of Moses' hand43" causes the sea to recede. As the Israelites cross the river on foot, the sea returns to its natural level "by command of the same hand", engulfing their pursuers44.

The second element of Moses' glory lies in his intimate and singular relationship with God, stemming from his role as prophet. A particularly striking example of this relationship is found in the episode of the promulgation of the tables of the Law, offering two significant moments45. First, during this event, the people stand at the foot of Mount Sinai while Moses climbs "the slopes of the high mountain"46. In this situation, God speaks to him directly and face to face47. Then, during the forty-day conversation with God at Mount Sinai, Petrarch describes Moses as addressing God almost as "a friend"48. Although this experience is fraught with difficulties, it brings tangible glory in the form of an astonishing sign: "unusual horns"49. Thus, despite the challenges surrounding him, Moses enjoys an intimate exchange with God in the exercise of his ministry, which sustains him in performing illustrious deeds as leader of the Jewish people.

Moses' virtues emanate from God, enabling him to fulfill his divine service, bringing him closer, as it were, to God himself.

Initially, Petrarch describes the singular genesis of Moses' virtues as a servant of God. The author deliberately omits anecdotes about Moses' successes at Pharaoh's court50, thus ruling out the possibility of depicting the natural virtues acquired during his childhood and adolescence. The description of Moses' virtues begins with the miracle of the scepter51. These virtues are in no way of human origin, the scepter being "as proof of divine virtue" intended to "show prodigies"52. After receiving the scepter, Moses begins his ministry as a prophet, and it's in adversity that his virtues fully manifest themselves. Thus, Petrarch recounts the process of the genesis of Moses' virtues, emphasizing that they are heavenly gifts bestowed by God at a precise moment to fulfill His divine purpose, thus excluding any human contribution to their emergence.

Moses' virtues are then manifested through his actions in the service of God, emphasized by Petrarch twice with exclamations.

The first mention highlights "gentleness and modesty53", illustrated by the way Moses accepts the advice of his father-in-law54 and his submission to the divine commandments on Mount Sinai55. These two aspects are a perfect representation of this virtue. The second mention highlights Moses' "patience" and "love56" through his prayers for the people and his adversaries, illustrating his tolerance towards God's people57 and reflecting divine zeal towards the rebels58. Petrarch thus creates a successful narrative dichotomy by establishing two opposing groups, where the virtues of Moses correspond to the primitive meaning of the Bible.

In addition, Petrarch compares the benevolence of the leader to the ingratitude of the people, showing Moses as the illustrious leader of an ungrateful people, while revealing how he overcomes hardship through his experience, as part of his pedagogical objective.

So, in the De viris illustribus, Petrarch presents Moses as a human hero whose achievement relies on divine assistance, relying mainly based on Jerome's Vulgate. Rather than emphasizing Moses as a prefigurement of Jesus, Petrarch models him as a great man of history, hoping that his audience can draw inspiration from him. In this process of character creation, he integrates his own exegetical reflections and literary understanding into the image of Moses. Petrarch seeks to portray both glory and virtue, thus conferring two distinct dimensions on the image of Moses: one secular, borrowing from the tradition of Roman heroes, emphasizing glory, and the other Christian, focusing on Moses' character and virtues, notably patience and love, which stand in contrast to the general traits of Roman heroes, but align with traditional Christian virtues.

This unique biography leads Petrarch to draw on key events in Moses' life and highlight his heroic aspect, even if it means making the prophet a Christian hero.

Conclusion

The "figurative" approach sheds light on the fusion of literary and exegetical dimensions in Petrarch's works devoted to Moses. Petrarchan exegesis, rooted in a historical perspective, presents Moses as a great man eminent in human history. In the De vita solitaria, Moses becomes the embodiment of the solitude advocated by Petrarch, reinventing this way of life as a new cultural modality for personal ends. On the other hand, in the De viris illustribus, Moses illustrates how the glory and virtue of a great man grow. The distinction between these two aspects is reflected in each work. As two scholars point out, the De viris illustribus paints "the traditional fusion of the biblical and Roman past59" while the De vita solitaria expresses the need of "a middle-aged man to attune his last readings of Christian texts to what is historically important to him60 ". At the same time, the literary form of biography provides criteria for the creation of the image of Moses, transformed into a "great man" according to the new ideology of the humanist Renaissance, as an exceptional writer using the events of Moses' life to serve his own humanist vision of the human being and the world.

Bibliography

AUERBACH, Erich, Figura. Jewish law and Christian promise, trans. by Diane Meur, post. by DE LAUNAY, Marc, Paris, Éditions Macula, 2017 (1993).

BEECHER, Donald, "Petrarch's "Conversion" on Mont Ventoux and the Patterns of Religious Experience", Renaissance and Reformation / Renaissance et Réforme, vol. 28, no. 3, 2004, pp. 55-75.

DARMON, Rachel, "Figuration fable et théologie dans les traités de mythographie", Réforme, Humanisme, Renaissance, n° 77, 2013, p. 31-50.

D'ALEXANDRIA, Philo, De vita mosis : I-II, Paris, Éditions du Cerf, 1967.

DE LUBAC, Henri, SJ, Exégèse médiévale : les quatre sens de l'Écriture, Paris, Cerf, DDB, 1993 (1959).

DE NYSSE, Grégoire, La vie de Moïse, trans. by Jean Daniélou, Paris, Éditions du Cerf, 1968.

DE NOLHAC, Pierre, Pétrarque et l'humanisme, Geneva, Slatkine Reprints, 2004.

DOTTI, Ugo, Pétrarque, trans. from the Italian by Jérôme Nicolas, Paris, Fayard, 1991.

EICHEL-LOJKINE, Patricia, Le siècle des grands hommes: les recueils de vies d'hommes illustres avec portraits du XVIe siècle, Louvain, Sterling (Va.), Peeters, Paris, Peeters France, 2001.

FABRE, François, "Pétrarque et saint Jérôme", in BROCK, Maurice, FURLAN, Francesco, LA BRASCA, Frank, eds, La bibliothèque de Pétrarque : livres et auteurs autour d'un humaniste, Turnhout, Brepols, 2008, p. 143-160.

FOSTER, Kenelm, Petrarch: poet and humanist, Edinburgh, Edinburgh university press, 1984.

JOSÈPHE, Flavius, Ancient history of the Jews. Livres I-V, Clermont-Ferrand, Éditions Paleo, 2014.

KOHL, Benjamin G., "Petrarch's Prefaces to de Viris Illustribus", History and Theory, vol. 13, no. 2, 1974, pp. 132-144.

La Sainte Bible, Nouvelle Édition de Genève 1979, Romanel-sur-Lausanne, Société Biblique de Genève, 2015.

MAGGI, Armando, ""You Will Be My Solitude": Solitude as Prophecy (De Vita Solitaria)", in KIRKHAM, Victoria and MAGGI, Armando, eds, A Critical Guide to the Complete Works, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2009, pp. 179-195.

MARÉCHAUX, Pierre, " François Pétrarque ", in NATIVEL, Colette, dir, Centuriae latinae : cent une figures humanistes de la Renaissance aux Lumières offerts à Jacques Chomarat, Genève, Droz, 1997, p. 607-612.

MARGOLIN, Jean-Claude, " Contemplation et vie solitaire chez Français Pétrarque et Charles de Bovelles ", in LA BRASCA, Frank, TROTTMANN, Christian, eds, Vie solitaire, vie civile, l'humanisme de Pétrarque à Alberti, H. Champion, 2011, p. 97-120.

MICHEL, Alain, Pétrarque et la pensée latine : tradition et novation en littérature, Avignon, Aubanel, 1974.

Moïse, figures d'un prophète, HOOG, Anne Hélène, SOMON, Matthieu, LÉGLISE, Matthieu, dir., Paris, Flammarion, Musée d'art et d'histoire du judaïsme, 2015.

PETRARCA, Francesco, De viris illustribus. Adam-Hercules, ed. by MALTA, Caterina, Università degli studi di Messina, Centro interdipartimentale di Studia umanistici, 2008.

PÉTRARQUE, De vita solitaria, La vie solitaire, bilingual Latin-French edition, trans. by CARRAUD, Christophe, Grenoble, Éditions Millon, 1999.

SAMUEL, Amsler, "Où en est la typologie de l'Ancien Testament?", Études théologiques et religieuses 3, 1952, pp. 75-81.

WHITE, Hayden, "Auerbach's literary history: Figural Causation and Modernist Historicism", in LERER, Seth, ed, Literary History and the Challenge of Philology: The Legacy of Erich Auerbach, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, 1996, pp. 124-139.

WITT, Ronald G., "The Rebirth of the Romans as Models of Character (De viris illustribus)", in KIRKHAM, Victoria and MAGGI, Armando, eds. Petrarch: A Critical Guide to the Complete Works, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2009, pp. 103-111.

WOJCIEHOWSKI, Dolora Chapelle, "Francis Petrarch: First Modem Friend", Texas Studies in Literature and Language, vol. 47, no. 4, 2005, pp. 269-298.

Notes

.Erich Auerbach, Figura. La Jewish law and the Christian promise, trans. by Diane Meur, post. by Marc de Launay, Paris, Éditions Macula, 2017.

See Moïse, figures d'un prophète, Anne Hélène Hoog, Matthieu Somon and Matthieu Léglise, eds, Paris, Flammarion, Musée d'art et d'histoire du judaïsme, 2015.

"Prefiguration" is linked to the typological method of Christian exegesis. See Amsler Samuel. "Où en est la typologie de l'Ancien Testament?", Études théologiques et religieuses 3, 1952, pp. 75-81. See also Henri de Lubac, SJ, Exégèse médiévale: les quatre sens de l'Écriture, Paris, Cerf, DDB, 1993 (1959).

Petrarch's place is presented in depth by Ugo Dotti in his Pétrarque, trans. from Italian by Jérôme Nicolas, Paris, Fayard, 1991; or Pierre Marchaux, "François Pétrarque", in Colette Nativel, ed, Centuriae latinae: cent une figures humanistes de la Renaissance aux Lumières offertes à Jacques Chomarat, Geneva, Droz, 1997, p. 607-612.

Petrarch, De vita solitaria, La vie solitaire, bilingual Latin-French edition, trans. by Christophe Carraud, Grenoble, Éditions Millon, 1999.

Francesco Petrarca, De viris illustribus. Adam-Hercules, ed. by Caterina Malta, Università degli studi di Messina, Centro interdipartimentale di studi umanistici, 2008.

Erich Auerbach, op. cit., p. 26., and more broadly p. 10-30.

Erich Auerbach, op. cit., p. 48.

See Hayden White, "Auerbach's literary history: Figural Causation and Modernist Historicism", in Seth Lerer, ed, Literary History and the Challenge of Philology: The Legacy of Erich Auerbach, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, 1996, p. 128: "The model is most pertinently utilizable in the study of literary styles and genres". Unless otherwise stated, translations are ours throughout.

Rachel Darmon, "Figuration fable et théologie dans les traités de mythographie", Réforme, Humanisme, Renaissance, 2013, n° 77, p. 49-50.

The apostle Paul writes in the New Testament, 1 Corinthians 10:2: "they were all baptized into Moses in the cloud and in the sea". The earliest Church Fathers to regard Moses as a spiritual example are Gregory of Nyssa and Clement of Alexandria. For more, see Gregory of Nyssa's La vie de Moïse, trans. by Jean Daniélou, Paris, Éditions du Cerf, 1968.

See the Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria, De vita mosis: I-II, Paris, Éditions du Cerf, 1967. See also the historian Flavius Josephus, Ancient History of the Jews. Livres I-V, Clermont-Ferrand, Éditions Paleo, 2014.

See Alain Michel, Pétrarque et la pensée latine : tradition et novation en littérature, Avignon, Aubanel, 1974.

Kenelm Foster, Petrarch: poet and humanist, Edinburgh, Edinburgh university press, 1984, p. 9: "showing Petrarch entering a new phase in his development as a writer... written for the public, spoke out explicitly as a Christian" ("showing Petrarch entering a new phase in his development as a writer... written for the public, spoke out explicitly as a Christian.")

Petrarch, De vita solitaria, La vie solitaire, bilingual Latin-French edition, trans. by Christophe Carraud, Grenoble, Éditions Millon, 1999, Livre Premier, V, 8, p. 102-103: "Videt Ille igitur nos auditique prius etiam, quam loquamur."; "He sees us, He hears us even before we speak." This event precedes the crossing of the Red Sea, as evoked in Exodus 14:14-15: "Moses said to the people, 'The Lord will fight for you, and you keep silent. And God said to Moses, 'Why these cries? Speak to the children of Israel, and let them walk."

Ibid., Livre Second, III, I. p. 196-197: "Ubi erat ille familiarissimus Deo vir Moyses"; "Where was this familiar of God, Moses" See Exodus 15, 22: "Moses set Israel out from the Red Sea. They headed for the wilderness of Shur; and after three days' march through the desert, they found no water."

Ibid.: "quando in castris coturnices ortigias affatim celo lapsas populus legit esuriens et de rupe percussa dulcis aque copiam sitiens bibit"; "when the starving people gathered, between the tents, all those quails that had fallen in profusion from heaven; when, thirsty, they drank to satiety the fresh water that gushed from the rock that Moses had struck."

Ibid.: "Vides, ut solitudo divinis beneficiis atque colloquiis et angelicis sit amica congressibus!"; "See how solitude is loved by divine benefits and talks, loved by great contests of angels!"

Armando Maggi, ""You Will Be My Solitude": Solitude as Prophecy (De Vita Solitaria)", in Victoria Kirkham and Armando Maggi, eds. A Critical Guide to the Complete Works, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2009, p. 180: "but rather intimate dialogue with a friend who pursues the same intellectual and spiritual ideals" ("mais plutôt un dialogue intime avec un ami qui poursuivues les mêmes idéaux intellectuels et spirituels").

See Deuteronomy 32, 48-50: "That same day, the Lord spoke to Moses, saying, 'Go up to this mountain of Abarim, to Mount Nebo, in the land of Moab, opposite Jericho; and look at the land of Canaan, which I give for a possession to the children of Israel. You will die on the mountain where you will go up, and you will be gathered to your people...". See J. Bondol's 1372 "Death of Moses" (online at Utpictura18).

Petrarch, op. cit., Livre Second, III, I. p. 196-197: "Quo minus miror, ut preclare vite viri illius sic et gloriose morti solitudinem deputatam, dum ex hominibus migraturo, quod fratri eius iam antea acciderat"; "So I watched without astonishment that to the glorious death as to the luminous life of Moses it was solitude that was assigned, when, at the time of departing from men [as his brother, already, had done]."

Ibid., Book Second, XIII, 15, pp. 350-351: "quos fuisse vult ante Africanum diu et in otio negotiosos et in solitudine comitatos"; "he wants them to have been before him active in leisure and accompanied in their solitude."

Ibid., Livre Second, XIII, 16, p. 352-353: "... nulla prorsus interveniente notitia omnis cesset imitatio, quam de rebus humanis laudum fameque particulam delibare atque decerpere solitam non nego? "; "and that we cannot therefore speak of imitation in his case - that imitation which I do not deny usually subtracts from human actions a few scraps of glory and renown?"

Ibid., Livre Second, XIV, I, pp. 352-353: "... volo solitudinem non solam, otium non iners nec inutile, sed quod e solitudine prosit multis"; "I want a solitude that is not alone, a leisure that is neither inactive nor useless, but draws from solitude a benefit that many can enjoy."

Ibid., Livre Second, XIV, 13, pp. 368-369: "Hunc ipse montem pervium fecit et hanc montanam preduramque silicem perforavit suis, ut aiunt, minibus, opus fervoris atque otii igentis"; "... He made this mountain accessible and, it is said, dug this very hard rock with his hands: a work requiring great ardor and considerable leisure."

Ibid., Book Second, XIII, pp. 368-369: "quod olim in transitu Maris Rubri viventis Moyseos virga potuerat, hoc, siqua fides, in transitu fluminum Verani pallium posset extincti"; "what the staff of the living Moses was once able to do at the passage of the Red Sea, the mantle of the dead Veran accomplished at the passage of the rivers."

See Donald Beecher, "Petrarch's "Conversion" on Mont Ventoux and the Patterns of Religious Experience", Renaissance and Reformation / Renaissance et Réforme, vol. 28, no. 3, 2004, p. 55-75.

Jean-Claude Margolin, "Contemplation et vie solitaire chez Français Pétrarque et Charles de Bovelles", in Frank La Brasca and Christian Trottmann, eds, Vie solitaire, vie civile, l'humanisme de Pétrarque à Alberti, Paris, H. Champion, 2011, p. 106.

Jean Meyers, op. cit., p. 222-223: "... literate solitude is, through reading and writing, a permanent struggle of vices and virtues, similar to that waged by hermits in the desert or by saints in the seclusion of monasteries. By comparing himself to them, Petrarch Christianizes an otium cum litteris of ancient inspiration and equates it with a form of sanctity."

Dolora Chapelle Wojciehowski, "Francis Petrarch: First Modem Friend", Texas Studies in Literature and Language, vol. 47, no. 4, 2005, p. 277: "He imagines a tiny community of friends joined in intellectual and spiritual pursuits - a quite different arrangement from medieval religious communities." ("He imagines a tiny community of friends joined in intellectual and spiritual pursuits - a quite different arrangement from medieval religious communities.")

Patricia Eichel-Lojkine sheds light on the significance of the De viris illustribus in Le siècle des grands hommes: les recueils de vies d'hommes illustres avec portraits du XVIe siècle, Louvain, Sterling, Peeters, Paris, Peeters France, 2001, p. 32: "The first Renaissance work devoted to Roman history, this collection is also the first literary attempt to revive the ancient genre of the Lives, and to secularize the model of hagiographic collections."

Benjamin G. Kohl, "Petrarch's Prefaces to de Viris Illustribus", History and Theory, Vol. 13, no. 2, 1974, p. 136: "Petrarch found them lacking both will and ability for greatness."

Ibid., p. 140: "while the illustrious ones are the product of glory and virtue" ("tandis que les illustres sont le produit de la gloire et de la vertu.")

Pierre de Nolhac, Petrarch and Humanism, Geneva, Slatkine Reprints, 2004, Book II, p. 2.

Benjamin G. Kohl, op. cit., p. 134: "all-ages" ("tous les âges").

See François Fabre, "Pétrarque et saint Jérôme", in Maurice Brock, Francesco Furlan, Frank La Brasca, eds, La bibliothèque de Pétrarque : livres et auteurs autour d'un humaniste, Turnhout, Brepols, 2008, p. 143-160. See the depiction of Moses with horns, communicating with God and receiving the Tables of the Law, in the miniature entitled "Moses receives the Tables of the Law" by Jean Bondol in 1372 (online at Utpictura18).

Pierre de Nolhac, op. cit., p. 155, note 2.

In the long preface to De viris illustribus, see Benjamin G. Kohl, op. cit.,p. 140: "the product of glory and virtue" ("le produit de la gloire et de la vertu").

In Christian exegesis, the Church Father Gregory of Nyssa establishes a tradition by making Moses the perfect model of perfection. See Gregory of Nyssa, La vie de Moïse ou Traité de la perfection en matière de vertu, ed. by Jean Daniélou, S.J., Paris, Éditions du Cerf, 1968. According to Gregory of Nyssa, as a "friend of God", Moses becomes an archetype whose life represents elevation "to the extreme limit of perfection" (II, 319, p. 325). According to Jean Daniélou, the life of Moses symbolizes three stages of the spiritual path, reminiscent of Origen's thoughts: "to pass from the darkness of ignorance to the light, then, beyond the light, to enter the cloud, and in the cloud, to let oneself be guided towards 'the darkness that is more than luminous'" (p. 37).

See Patricia Eichel-Lojkine, op. cit., p. 66: "In fact, literary glory and military glory are not felt to be incompatible, or even essentially different by the majority of humanists (apart from the notable exception of Erasmus)."

Francesco Petrarca, De viris illustribus. Adam-Hercules, a cura di Caterina Malta, Università degli studi di Messina, Centro interdipartimentale di studi umanistici, 2008, 25, p. 72: "Deo collocutore et si dici licet consiliario fretus ..." ([Moses] relying on God as interlocutor and, if it is fair to say so, adviser...). See Exodus 18:13: "The next day Moses sat down to judge the people, and the people stood before him from morning until evening."

Ibid., 24: "quam unius senis nude manus et ad celum erecte de tot armatis hostium milibus peperere, quando, Iosue exercitui preposito, ipse cum fratre solus et amico in verticem montis ascendit et inde precibus piis pugnans stravit exercitum Amalech? "("what did the bare hands of a single old man, raised to heaven, win over so many thousands of enemy soldiers, when, being Joshua leader of the army, he himself alone with his brother and a friend reached the summit of the mountain and from here fighting with pious prayers struck down the army of Amelech?"). See Exodus 17, 11-12: "When Moses raised his hand, Israel was strongest; and when he lowered his hand, Amalech was strongest. Moses' hands were tired, so they took a stone and placed it under him, and he sat on it. Aaron and Hur supported his hands, one on one side, the other on the other; and his hands remained firm until sunset."

Ibid., 20, p. 70: "quando mosayce manus obtentu mare vidit et fugit..." ("when, at the lifting of Moses' hand, [Pharaoh] saw the sea and fled..."). See Exodus 14:21: "Moses stretched out his hand over the sea. And the Lord drove back the sea with an east wind, which blew impetuously all night; he dried up the sea, and the waters were split."

Ibid., 20: "eiusdem manus imperio, in naturam propriam versa..." ("by order of the same hand, [the sea has] returned to its natural form"). See Exodus 14:27: "Moses stretched out his hand over the sea. And toward morning, the sea resumed its impetuosity, and rushed the Egyptians into the middle of the sea."

See Exodus 19:20: "So the Lord came down to Mount Sinai, to the top of the mountain; the Lord called Moses to the top of the mountain. And Moses went up."

Francesco Petrarca, op. cit., 26, p. 72: "et universo populo audient colloquium Dei et hominis ac stupente ad radices populo unum Moysen, vocante Deo, scandentem convexa montis aerii..." ("and, while all the people listened to the conversation of God and man and marveled at the feet [of the mountain], Moses all alone at God's request climbed the slopes of the high mountain.")

See Exodus 20:21: "The people remained in the distance; but Moses approached the cloud where God was."

Francesco Petrarca, op. cit., 28, p. 74: "rursum quoque Moysen coram facie ad faciem cum Deo quasi cum amico colloquentem..." ("and once again Moses finds himself directly before God, as if speaking almost to a friend"). See Exodus 34:28: "Moses was there with the Lord forty days and forty nights. He ate no bread, and drank no water".

Ibid., 28: "... et a colloquio Dei redeuntis insolitis prodigiosam cornibus effigiem." ("and the prodigious image of him who returned from the colloquy with God with unusual horns"). See Exodus 34:29: "Moses came down from Mount Sinai, having the two tablets of the testimony in his hand, as he came down from the mountain; and he did not know that the skin of his face glowed, because he had spoken with the Lord."

The historian Flavius Josephus relates several anecdotes, including one in which Moses throws Pharaoh's diadem to the ground. See Flavius Josephus, Ancient History of the Jews. Livres I-V, Clermont-Ferrand, Éditions Paleo, 2014, Livre II, Chap IX, 7, p. 115.

God commands Moses to perform miracles with his shepherd's rod. See Exodus 4:17: "(God said to Moses) Take this rod in your hand, with which you shall do signs."

Francesco Petrarca, op. cit., 18, p. 70: "... quando virgam illam, quam in manu gestabat, non iam pastoralis pedi sed divine virtutis officium gerere voluit in faciendis monstris..." ("when he wanted to use the rod he had in his hands not as a shepherd's staff, but as proof of divine virtue, to show prodigies...")

Ibid., 25, p. 72: "Iam quis illam mansuetudinem ac modestiam non miretur..." ("and then who will not have admiration for [Moses'] gentleness and modesty...")

Ibid., 25: "cognati multo imparis consilium tam dignanter amplexus est ut..." ("Moses] accepted the advice of a far inferior relative with such courtesy"). See Exodus 18:21: "[Moses' father-in-law said to him]: Choose from among all the people able men, God-fearing, men of integrity, enemies of greed; set them over them as rulers of thousands, rulers of hundreds, rulers of fifties and rulers of tens."

Ibid., 29, p. 74: "... et delectatum Dominum perfecti decore operis, ac diurnam nubem ignemque nocturnum incumbentum tabernaculo divinamque maiestatem circum ac supra sacrum edificium visibiliter coruscantem, ita ut ipse quoque Moyses ingredi non auderet." ("and the Lord was pleased with the magnificence of the finished work, with the cloud that stretched over the tabernacle by day, with the fire that hovered over it by night, and with the divine majesty that shone, in the eyes of all, around and above the sacred edifice. So much so that Moses himself dared not cross the threshold.") See Exodus 40:35: "Moses could not enter the Tent of Meeting, because the cloud remained over it, and the glory of the Lord filled the tabernacle."

Ibid., 30, p. 74: "et inter hec omnia quanta ducis patientia, quantus amor, ut et pro populo et pro emulis exoraret..." ("and in all these circumstances, how much patience on the part of the guide [Moses], how much love, to the point of praying without ceasing both for the people and for his rivals...") See Numbers 11.

Ibid., 31: "dum ne universum populum perderet exoratus Deus iussisset populum ab impiis segregari...". ("When Moses prayed to God not to destroy all the people, God commanded that the people be separated from the ungodly...") See Numbers 16:20-24: "And the Lord spoke to Moses and Aaron, saying, 'Separate yourselves from the midst of this assembly, and I will consume them in a moment.' And they fell on their faces, and said, O God, God of the spirits of all flesh, one man hath sinned, and thou wilt be angry with the whole congregation. And the Lord spake unto Moses, saying, Speak unto the congregation, and say, Withdraw yourselves on every side from the habitation of Korah, Dathan and Abiram."

Ibid., 35, p. 76: "... ubi notare est mitissimi ducis acrimoniam..." ("and there we can notice the harshness of this so peaceful leader...") See Numbers 31:14: "And Moses was angry with the commanders of the army, the chiefs of thousands and the chiefs hundreds, who were returning from the expedition. He said to them, 'Have you left all the women alive? Behold, they are the ones who, at Balaam's word, led the children of Israel astray from the Lord in the matter of Peor; and then the plague broke out in the assembly of the Lord. Now kill every male among the little children, and kill every woman who has known a man by lying with him; but leave alive for yourselves every daughter who has not known a man's bed."

Hans Baron, From Petrarch to Leonardo Bruni: studies in humanistic and political literature, Chicago, London, University of Chicago Press, 1968, p. 27: "... the traditional commixture of the biblical and the Roman past..." ("the traditional commixture of the biblical and the Roman past").

Ronald G.Witt, "The Rebirth of the Romans as Models of Character (De viris illustribus)", in Victoria Kirkham and Armando Maggi, eds. Petrarch: A Critical Guide to the Complete Works, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2009, p. 110: "As awakening in the middle-aged man a need to integrate his recent readings in Christian literature with his conception of the historically important" ("As awakening in the middle-aged man a need to integrate his recent readings in Christian literature with his conception of the historically important.")

Figures et images. De la figura antique aux théories contemporaines ?

1|2024 - sous la direction de Benoît Tane

Figures et images. De la figura antique aux théories contemporaines ?

Présentation du numéro

Figures et figuration. Le modèle exégétique

Le « peuple figuratif », entre lecture figurale et anthropologie structurale

La figure de Moïse comme grand homme chez Pétrarque

Les amours de Pyrame et Thisbé et le divin

Représentation visuelle, représentation textuelle

La figure de la licorne

Fonction de l’image dans les descriptions jésuites de la Chine et des Indes orientales

Marqué d’une croix : l’espace de la figure dans la poésie de Jørn H. Sværen

L’épopée figurale des corps dans Tombeau pour cinq cent mille soldats et Éden, Éden, Éden de Pierre Guyotat