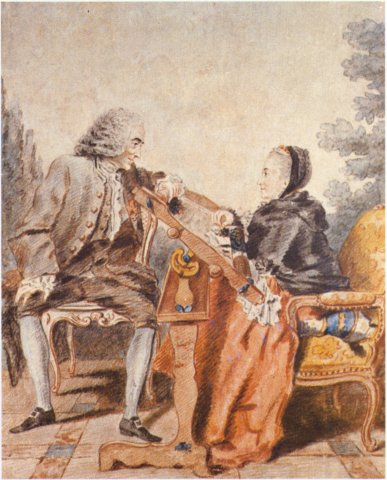

Carmontelle, Voltaire and Mme du Châtelet, 1747-1750, former Lady Mendl collection

Voltairean dialogue is not a genre of discourse

Circulation of the dialogic form, upstream and downstream of the Dictionnaire

Wondering about dialogue in the Dictionnaire philosophique might seem like a question of genre1 : Voltaire wrote separate dialogues, and the genre of philosophical dialogue, however marginal in his output, was no stranger to him. Better still, between these separate dialogues and the articles in the Dictionnaire, we can see a circulation.

If the Entretien avec un Chinois published in 1740 in the Recueil des pièces fugitives2 is only distantly related to the Chinese Catechism, the Catéchisme de l'honnête homme, ou Dialogue entre un caloyer et un homme de bien (1763) obviously inaugurates the four catechisms of the Dictionnaire, but also the article Dieu3. The theme of the Dictionnaire's Soul article inspires the second interview of L'A, B, C, ou dialogue entre A, B, C (1768)4, the article Etats, gouvernements, quel est le meilleur ? prepares the sixth interview, while the fourth interview is taken up almost identically in Loi naturelle, and the eleventh in Droit (du) de la guerre from Questions sur l'Encyclopédie. As for the Vertu article, which from 1764 proceeds by question and answer, confronting an indeterminate interlocutor (" What does it matter to me that you are temperant ? " " But, are you telling me... " ; " On fait une objection bien plus forte "), it would be preceded in 1772, in the Questions sur l'Encyclopédie, by the dialogue of an honest man and " the excrement of theology "5.

This circulation must be seen as a symptom : the dictionary genre presupposes that it collates definitions, objective data this collation6 is hardly reconcilable with the clash of subjectivities implied a priori by the dialogue device, with its alternating takes on words. However, this collation implied by the Dictionary genre necessarily divides and disseminates the monological instance: this is why we have spoken of the Dictionnaire philosophique as a collapsed monologism. In this context, the dialogue appears as a kind of perversion of the Dictionary, a derangement of its taxonomic dissemination. It manifests Voltaire's intention, which is not to objectify a plurality of isolated meanings in the distinct headings of a dictionary, but rather to arrange voices against each other, to operate short circuits through them, in a word to disorganize the dictionary through dialogue.

If Voltaire perverts the pre-stressed framework of the genre, it is in the dialogic and hence fundamentally anti-generic movement of this perversion that we must grasp his thought and writing : the Voltairian poetic tendency passes through the test of dialogue writing pushes towards the dialogic outcrop something in it produces, as a necessity, this dissemination of discourse, this splitting of the block, of the monological person.

Forms of dialogue : the interview, questions, interjection, /// the anecdote

The dialogues themselves, typographically marked by the centered and alternating inscription, in capital letters, of the names of the interlocutors, are few in number in the Dictionnaire philosophique : to the four catechisms, we must add the dialogue between Logomachos and Dondindac in the article Dieu, between Bambabef and Ouang in the article Fraude, between A and B in Liberté, between Medroso and Boldmind in Liberté de penser, between Osmin and Selim in Nécessaire, between the papist and the treasurer in Papisme. The article Idée finally questions and answers without character names.

To these eleven articles must be added those written entirely or partly in the form of questions, which formally prefigure the Questions sur les miracles (1765) the Questions de Zapata (1766) and above all the Questions sur l'Encyclopédie (from 1771). We might cite the eight questions in the Moses article introduced by a characteristic formula : " Others, bolder, have made the following questions ". These eight questions are therefore other questions before the questions were formally asked and typographically marked as interruptions, interjections in the text, there was already a vague questioning, a diffuse setting in contradiction, a dialogization in monological dissemination. The article Religion is made up of eight questions that constitute the eight sub-entries of the article the article Paul, questions sur Paul, is a veritable firework display of questions, which Voltaire concludes with a pirouette :

" I make none of these questions but to instruct myself, and I require of anyone who will instruct me that he speak reasonably. " (P. 319.)

The formatting of the article becomes, literally, a questioning, which is not a mere rhetorical disposition, or Voltairian variation on the generic structure of the dictionary, but interpellates the Other of discourse and tends towards dialogic knotting.

In addition to the questions themselves, Voltaire interjects and addresses various fictional characters. " Bonjour, mon ami Job... Avoue que tu étais un grand bavard " (p. 246) : summoned to confess, Job comes very close to starting a conversation with Voltaire. In the article Judea, Voltaire addresses the Jews : " Alas ! my friends, you never had these fertile shores of the Euphrates and the Nile... Promising and keeping are two my poor Jews... Farewell my dear Jews " (p. 253).

Finally, the Voltairean anecdote is an opportunity to broach a few brief dialogues in the course of an article. Thus, in the 1765 addition at the end of the article D'Ezéchiel :

" NB. I met one day in Amsterdam a Rabbi all full of this chapter. Ah ! my friend," he said, "how much we owe you ! You have made known all the sublimity of the Mosaic law, Ezechiel's lunch, his beautiful attitudes on the left side Oolla & Oliba are admirable things, they are tipes7, my brothers, tipes, which figure that one day the Jewish people will be masters of the whole earth ; but why have you omitted so many others that are about this strength ? why haven't you depicted the Lord saying to the wise Hosea as early as the second verse of Ir. chap. Hosea, take a daughter of joy, & make him sons of daughter of joy. These are his own words. Hosea took the damsel, he had a boy, then a girl, then a boy again, it was a tipe ; this tipe lasted three years. This is not all, said the Lord in the 3rde. chap. Go and take a wife who is not only debauched, but an adulteress Hosea obeyed, but it cost him fifteen écus, a septier and a half of barley for you know that in the promised land there was very little wheat. But do you know what that means? No," I told him; "nor do I," said the Rabbi.

A serious scholar /// told us they were ingenious fictions, all full of pleasure. Ah, Monsieur," replied a well-educated young man, "if you want fictions, believe me, prefer those of Homer, Virgil and Ovid; anyone who likes Ezekiel's prophecies deserves to have lunch with him. " (P. 188, ed. Varberg I, 310-3118.)

Eighteenth-century typography doesn't establish the clean break of quotation marks and dashes, which visibly delineate in the text what is being dialogued. A simple exclamation mark (" Ah ! mon ami "), a semicolon (" Non, lui dis-je ; Ni moi non plus, dit le Rabin ") modulate the intonation and bring out, in the monological discourse of the dictionary, the outline of an unlikely conversation between the enthusiastic rabbi and an incredulous Voltaire.

The dissemination of Voltairean monologism : dialogue and trait

The rabbi's strange speech, which it's impossible to determine whether it's inhabited by naïve, sincere enthusiasm, or biting irony that mocks Voltaire, insensitively drifts into a dialogue that's impossible to mark because it's uncontrollable : first it's the dialogue of the Lord and Hosea in the rabbi's mouth (" Hosea, take a daughter of joy, & make him sons of daughter of joy "), which itself responds to Ezekiel's dialogue with God, at the beginning of the article9. This is followed by a dialogue between the rabbi and Voltaire (" But do you know what it means ? No, I tell him "). Finally, the conversation becomes generalized with the intervention of " a grave scholar " who " approached us ", then a " highly educated young man " who " replied ". The dissemination is such that the final line (" anyone who likes Ezekiel's prophecies deserves to have lunch with him ") is unassignable : is it the young man who continues his defense of Homer and Virgil against the Bible ? is it Voltaire who takes over ? is it the small group aggregated in the conversation who choruses, thus forcing the reader to become part of the discourse ?

As we can see, dialogization proceeds from the same phenomenon as irony it's a tendency of the discourse rather than a procedure, a tendency that consists in interpellating the Other of the discourse, this institutional discourse in the face of which Voltairean speech is both in demand and in response, and disposes of itself, fragments itself in order, from one to the other, to operate the dialogic knotting.

Sometimes the dialogue is reduced to a line, as in this playlet Voltaire sketches out in the article Torture (1769) between the Conseiller de la Tournelle and his wife.

" The grave Magistrate who bought for some money the right to perform these experiments on his neighbor, is going to tell his wife at dinner what happened in the morning. The first time Madame was revolted by it, on the second she took a liking to it, because after all women are curious : & then the first thing she says to him when he comes home in his dress, My little heart, didn't you have the question given to anyone today10 ?

The revolting horror of judicial torture spreads from the scene itself to the magistrate's wife's revolt (" The first time Madame was revolted by it "), then turns into the pleasure of conversation (" she took a liking to it "), where the question to the " little heart " is superimposed on the other question (" didn't you ask anyone to give you the question today ? "). Here we find the superimposition constitutive of the ironic line " personne ", which expresses the absence of the tortured prisoner and at the same time his spectral presence in the pleasant conversation, gives a concrete body to the " personne ". /// " question " abstracted from the wife, and absent from this body. Conversely, the terrible figure of the magistrate " en robe " is turned, by the familiar sobriquet of the " petit cœur ", into the bland figure of an inconsistent husband. The " petit cœur " is the Nom-du-Père that carries the metaphorical charge of the trait the " question " articulates the real (torture) to the symbolic (language) in the semiotic arc of pas-de-sens ; " personne " carries the spectral haunting of conjuration11.

The ironic line marks the culmination of discursive dissemination : it not only reverses the horror of torture into enjoyment through language it divides this language and, through the suspense it creates, opens up the virtuality of dialogue.

This is no longer the dialogue announced and framed as an ongoing conversation, as a face-to-face meeting of two figures, two symbolic statuses, two discursive contents, but the outline or outcropping of an uncertain dialogue : his interlocutors remain undefined he throws out unanswered questions, the repeated interjection drawing the vague but insistent contours of a " tu " versus the Voltairean " je " sometimes, beyond the frank questioning, the dialogue takes shape in the mere contradiction of the discourse with itself.

We see emerging here not a generic category of articles, not a circumscribed regime of Voltairian discourse that would choose between different rhetorical strategies, but a propensity, an accentuation, a dialogic tendency. It is this tendency that we propose to analyze.

The dialogic tendency : example of CHINESE CATECHISM

Structure of the Chinese Catechism

The Chinese Catechism is presented as a series of six talks between Kou, a future king in China, and Cu-Su (qu'eût su ?), his philosophical adviser. From the outset, we note that the characters (unlike, for example, Logomachos' head-on opposition to Dondindac in the God article) do not represent antagonistic positions. The interview suggests connivance, a common propaedeutic approach, in the spirit of " catechism12 ". It belongs to the old rhetorical tradition of the Miroirs and Instructions du prince13, where the future monarch found the idealized abridgement of the values, the principles of government on which his political action was supposed to have to be based.

This is not the position of preceptor and disciple either, as in the Adventures of Telemachus written in 1694 by Fénelon for the Duke of Burgundy, grandson of Louis XIV. In it, Minerva, " who accompanied Telemachus under the figure of Mentor " showed her pupil the path of virtue14. But Cu-Su is not a master, still less a god in disguise : the pupil prince is faced by a philosopher pupil, a " disciple of Confutzée " : " what pleases me in you, Kou tells him, is that you don't pretend to know what you don't know " (p. 67).

The dialogue does not oppose doctrines, nor does it deliver positive teaching, at least initially.Instead, it expresses doubts : doubts about heaven in the first conversation, which denounces the absurdity of worshipping material heaven (" There is no heaven ", p. 6515), doubts about God in the second interview, which marks the impossibility of assigning God a place in space (" God is not like the emperor of China ", p. 67) doubts about the soul in the third interview, /// who pleads to believe in it for want of anything better (" the soul is a word invented to weakly and obscurely express the springs of life ", p. 70) ; doubts about worshiping God, finally, whose rites are absurd and delirious, in the fourth interview (" when I've shouted that the Chang-ti mountain is a fat mountain... will this galimatias be pleasing to the Supreme Being ? ", p. 76).

Separation in connivance in the face of instituted discourse

Voltaire arranges Kou and Cu-Su on either side of this common doubt, which unites them intellectually when their function, their social status separates them. This socio-political separation in intellectual connivance will be found again in Le Catéchisme du curé, between Théotime, a new and modest country priest, and his friend Ariston, who could buy a house in his parish. Similarly, in The Gardener's Catechism, a familiar, almost consensual conversation is established between Bacha Tuctan, governor of Samos, who wields political power, and the gardener Karpos, a Greek peasant who is subservient to him. The same separation in the connivance in the Freedom of Thought article, between the English officer Boldmind16, apostle of British liberties, and Count Medroso, subject of the Spanish Inquisition. If the setting of the dialogue is indeed the first phase of the War of the Spanish Succession, Boldmind is the conqueror, Medroso the vanquished, which does not prevent, in the dialogue, a certain connivance around the idea of tolerance, to which the words of both Boldmind and Medroso are confronted17.

A certain discourse is placed at the heart of the dialogue, is thrown at the interlocutors, a discourse that neither of them intends to assume. In the Chinese Catechism, this discourse is the discourse of fanatical theologians :

" It would be an insanity quite absurd to worship vapors "

" What do we claim when we say, heaven & earth, ascend to heaven, be worthy of heaven ? - One says an enormous silliness "

" You feel that if the inhabitants of the moon were to say that one ascends to the earth, that one must make oneself worthy of the earth, they would say an extravagance "

" But when we say he made heaven & earth, we piously say one great poverty. "

" These are tales that the bonzes tell to the children & to the old women " (p. 64-66 ; ed. Varberg, I, 100-102)

" follies ", " énormes sottises ", " extravagances " the " pauvretés ", the " contes "are uttered by an indeterminate " on ", which sometimes declines externally into " ils " and sometimes internally into " on ". Discourse is there, to be absorbed without distance, or rejected with horror and disgust. Discourse is literally abject, i.e. caught, outside any object relation, in a dialogic polarity, between fascination and abjection, between absorption and deglutition.

The actor and the witness

Very present in the first interview of The Chinese Catechism, the abject discourse of the Other, the discourse of the religious institution, is evoked, characterized more quickly in the following interviews : " ce galimatias " and " de telles rêveries " in the fourth interview (p.76) " preaching and writing their musings " in the fifth (p.81). Faced with him, the two interlocutors are both in a position of conspiracy. One, the witness, the philosopher, the intellectual, Cu-Su, conjuring the other, the political actor, the enlightened despot, Kou, to ward off the spectre of fanaticism, to ward off dead superstitions, the ghost of paternal religion.

Actor and witness are arranged on either side of the discourse /// abject and instituted. The object of the dialogue is the conjuration they set in motion. In the Catechisme du curé, Théotime is the actor, about to take office in his parish like Kou in his kingdom; he inherits his father's institution and, in it, inhabited by it, conjures it, that is, contradictorily, implements and repels it. Ariston is the witness who, by his presence, his encouragement, makes possible the conjuring that Theotime is about to perform.

The " comment " dialogic : naming and conjuring

Ariston's questioning takes the form of the " comment " :

" You are wise, & you have wise eloquence ; how do you intend to preach before country folk ? "

" Please tell me how you will use it in confession. "

" How will you prevent the peasants from enyvrering on feast days ? "

" It must be confessed, the state loses more subjects by festivals than by battles : how will you be able to diminish in your parish such an execrable abuse ? " (Pp. 86-88 ; ed. Varberg, I, 146-151)

This is the same question that animates Cu-Su at the beginning of the fifth interview, when the Chinese Catechism moves from the enumeration of doubts (which spectralizes instituted discourse), to the affirmation of the future sovereign's new principles (by which the specter of fanaticism must be warded off) :

" Since you love virtue, how will you practice it when you are King ? " (P. 79 ; ed. Varberg, I, 125.)

" But how will you use it with your enemies ? Confutzé recommends in twenty places to love them ; doesn't that seem a bit ridiculous ?

KOU

Love your enemies ! My God, nothing is so common.CU-SU.

How do you hear it ?KOU.

But as it must, I think, be heard. " (P. 81 ; I, 128)Facing the protagonist of the conjuration, facing the prince (Kou) or the priest (Theotime), the witness is not simply a passive spectator. His verbal, dialogical function is essential: he names what is to be conjured; he introduces the instituted discourse; he presentiments it through his words. Kou's exclamation at the start of the sixth interview is significant in this respect. Cu-Su evokes the virtues to be revived in the next reign: positive conjuration succeeds, in the last two talks, the doubts and superstitious conjurations that occupied the first four. Kou then asks Cu-Su about this all-important virtue which threatens to fall into disuse :

" What is it ? name it quickly ; I'll try to revive it. " (P. 82.)The witness, Cu-Su, names the spectres the actor, Kou, conjures them. One makes the thing come to speech the other, on the stage of dialogue, makes the thing enter or leave through speech.

The excommunication

Thus, in the Curé's Catechism, among Theotime's prerogatives, Ariston is led to name excommunication :

" Ariston.

And excommunications, will you use them ?Theotime.

No ; there are rituals where grasshoppers, sorcerers & comedians are excommunicated. I will not forbid grasshoppers to enter the church, since they never go there. I will not excommunicate witches, because there are no witches : & with regard to comedians, as they are pensioned by the King, & authorized by the magistrate, I will be careful not to defame them. " (P. 87 ; I, 15018.)The old conjuration, the magical conjuration, is repudiated by Theotime, stigmatized as ridiculous and of another age19. But it's still there, consubstantial with Christianity. In the article Christianisme, Voltaire reminds us that " what most distinguished Christians, and what has lasted until our latest times, was the power to cast out devils with the sign of the cross " (p. 123).

Theotime won't excommunicate comedians :

" Le Seigneur de mon village fait jouer dans son château quelques de ces pièces, par de jeunes personnes qui ont du talent : ces représentations inspirent la vertu par l'attrait du plaisir elles forment le goût, elles apprennent à bien parler & à bien prononcer. I don't see anything but very innocent, and even very useful I intend to attend these shows for my education, but in a grilled box so as not to scandalize the weak. " (I, 150-151.)Failing to chase the theater demon out of the parish, the good parish priest himself becomes, in the shadow of his grilled dressing room, a specter impenetrable to the eyes20. Faced with the dramatic actors, the dialogic actor Theotime becomes a witness, naming the virtues the play enacts, and delegating to the stage the work of conjuring21.

The conspiracy

This dialogical distribution of actor and witness on either side of the spectral discourse, i.e. both instituted and abject, constitutes the Voltairean dialogical device as a conjuring device, which the Voltairean imagination then declines and adapts to the most varied situations : in the Gardener's Catechism, it is paradoxically the humble Karpos who is placed in the position of actor, while the powerful Tuctan serves only as his humble witness. The dialogue quickly turns to conjuration, taken here in the sense of conspiracy :

" Tuctan.

But if your Pâpa22 Greek made a conspiracy against me, & if he ordered you on behalf of Tou Patrou, & of Tou you, to enter into his plot, would you not have the devotion to be ?Karpos.

Me ? not at all ; I'd give it a go.Tuctan.

And why would you refuse to obey your Greek Pâpa on such a fine occasion ?Karpos.

It is that I have sworn obedience to you, & that I know well that Tou Patrou does not order conspiracies23. " (P. 96 ; I, 15624.)While the bacha Tuctan holds the temporal reality of power on the island of Samos, he is well aware that hovering among his constituents is the shadow, the specter of religious revolt, against the occupier's Islam, in the name of Orthodoxy. The spectre is very explicitly designated as the Name-of-the-Father : it is in the name of the father and son, εἰς τὸ ὄνομα τοῦ Πατρός, καὶ τοῦ Υἱοῦ, that at any moment a plot can be formed. Karpos simplifies the formula : " I know well that tou patrou (the Father's Name) does not order conspiracies ".

Karpos refuses conspiracy as Theotime renounces excommunication : but such is the power of spectres that the refusal to conjure them, far from making them disappear, permanently installs their presence25, and constitutes, as it were, the revolted framework necessary to the establishment, the perpetuation of Voltairian dialogue.

The ironic figure, /// pivot of dialogic reversal

The reversal of roles between actor and witness in the dialogue of The Gardener's Catechism is found between Logomachos and Dondindac in the article Dieu : Logomachos, like Tuctan, has come as a master, but witnesses the enactment of natural religion which the elderly Dondindac provides him with.

" The good old man Dondindac was in his great low hall, between his great sheepfold & his vast barn ; he was on his knees with his wife, his five sons & his five daughters, his parents & his valets ; & all singing the praises of God after a light meal. What are you doing here, idolater?" said Logomachos. I'm not an idolater, says Dondindac." (P. 163 ; I, 266.)Between Logomachos and Dondindac, the tableau formed by the gathered Scythians invoking God constitutes the dialogic object, of which the former is the witness, and the latter the actor. More precisely, this object is a discourse (" all sang the praises of God ") that forms a tableau as a representation of an ideal symbolic institution, reflected in the spectral unreality of the Scythian world. The song of natural religion, sung by the old man from another world, creates a tableau as a spectre of lost simplicity. In this tableau, Logomachos' interruption is ambiguous: " what are you doing there " must be understood as " what are you doing ", by which Logomachos reproves the Scythian heresy and the rite he overhears, but can also be understood as " what are you doing there ? ", you have nothing to do here, by which Logomachos would chase away, conjure up what for him appears as the spectre of a bygone primitive religion... The interruption has at bottom only symbolic meaning, as conjuration : What are you doing here, idolater, as Vade retro, Satanas...

The actor Karpos, who sells his figs and not his daughter26, like the actor Dondindac, through the conjuration they produce, turn upside down the hierarchical situation that initially seemed instituted. This hierarchical reversal constitutes, as we shall see, an essential spring of dialogical thinking, the form and the fundamental stake of the devices it implements.

At Liberté de penser, the conversation between Medroso and Boldmind is not so much ordered around a discourse of the institution as around the very horrific and abject institution of the Inquisition, which blocks, forbids any possibility of discourse. Boldmind attempts to represent to Medroso the cage in which his enslaved mind is locked :

" It's up to you to learn to think ; you were born with spirit ; you're a bird in the cage of the inquisition the Holy Office has clipped your wings, but they can come back. " (P. 266 ; II, 94.)Medroso is invited to the spectacle of himself, by Boldmind who, on the very person of his witness, undertakes the dialogic conjuration :

" Medroso.

So you think my soul is in the galleys ?Boldmind.Boldmind.

Yes, I'd like to deliver her.Medroso.

But if I find myself in the galleys ?

In that case you deserve to be there. " (P. 267 ; II, 95-9627.)

The point marks the failure of the conjuration : it expresses the break, the abrupt interruption of the process, as at the conclusion of the Ezekiel article :

" Anyone who loves Ezekiel's prophecies deserves to have lunch with him. " (P. 189.)

It's the same merit, identified with the figure, with the scatological metaphor produced by the Voltairean witz : Ezekiel's toast for his prophecies, Medroso's galleys (Merdoso) /// for his subjection to the Inquisition, metaphorize the symbolic institution, but metaphorize it as abjection, as an eternal Revenant whose conjuration is always to be begun anew.

.Irony figures the spectre, produces for it a ridiculous, miserable figure: the spectre to be conjured becomes jam or tartine in Ezekiel, becomes Karpos fig in the Gardener's Catechism , becomes cage or galley in Liberté de penser. To produce the Nom-du-Père in place of these derisorily feminized figures is to provide the material, the verbal support for conjuration. The witticism does not produce this Nom; it stops at the threshold of what dialogue, for its part, can accomplish.

Medroso unwillingly provides Boldmind with the figure ; he names the galleys that Boldmind offers to conjure. Boldmind calls him a galley slave. But the Name-of-the-Father is given neither by the " galley slaves ", the subjects of the Inquisition, nor by the Inquisition itself, by these " galleys ", these cages where they are taken : Voltaire would only name Saint Dominic, the Father of the Inquisition, in the Aranda article of the Questions sur l'Encyclopédie28.

The figure on which the trait d'esprit pivots screens, with all the thickness of its triviality, the Nom-du-Père then impossible to conjure. This very figure is taboo : Boldmind does not pronounce the name Medroso provides ; " je voudrais la délivrer " (votre âme des galères) ; " vous méritez d'y être " (aux galères). In vain you will not pronounce my name29. Behind the screen metaphor, it's the Nom-du-Père that it's always a question of defying and freeing oneself.

Dialogical liberation : example of JAPANESE CATECHISM

Dialogue as genre and dialogism as trend

The characterization of Voltairian dialogue in the Dictionnaire philosophique not as a predetermined genre (which would contradict the Dictionary's genre anyway) but as a tendency, the functioning of dialogue, not as the opposition of two theses, of two discourses on a given subject, but as the distribution of two functions (of the witness and the actor, of the one who names and the one who conjures) around a spectralized discourse leads us to consider dialogue in the continuity of the ironic devices we studied earlier and, by the same token, to take into account the dimension of liberating reversal they lead and propose, within the framework of an imaginary scenography that discursive analysis alone cannot account for.

Here we touch on the properly Bakhtinian dimension of dialogism, a term, a notion that Mikhail Bakhtin was the first to introduce, as a central mechanism in the historical, philosophical and fundamentally anti-generic constitution of the novel. At the end of Chapter IV of Poetics of Dostoevsky, entitled " Composition and genre ", Mikhail Bakhtin opens a long and famous digression on what he calls " menippée ", or the " comico-serious ", which extends from the Socratic dialogue to the modern novel, via satire, Lucian's dialogues and the introduction, into literary representation, of all the caricatures, parodic features, realia grotesque or buffoonish inspired by the present moment and constituting what he designates as the " carnavalesque " dimension.

The collapsed monologism of the Philosophical Dictionary

The first characteristic of " comico-serious " writings is the distance they take from instituted discourse. Far from being neglected, however, or passed over in silence, the latter constitutes the central object of the dialogic tendency, which weakens, disseminates or turns it inside out, and carnivalizes :

" It's true that all comic-serious genres contain a /// powerful rhetorical element ; but in the atmosphere of the joyful relativity proper to the perception of the carnivalesque world, this element changes considerably : its one-sided rhetorical seriousness, its rationalism, its monic and dogmatic aspect are weakened. " (P. 15230.)

The ironic accentuation of Voltairean speech, and the dialogic tendency that proceeds from this accentuation, create precisely this atmosphere of joyful relativity where, faced with the horror of the world, everything being equal, the best thing is still to laugh about it31. Voltaire's own difficulty in producing a dogmatic discourse of his own other than in the form of the reversal of doubt (Catechisme chinois) or cautious withdrawal (Catechisme du jardinier ; Dondindac's falsely naïve interrogations in the article Dieu) is symptomatic of this weakening, even collapse of monological discourse.

Actuality and atemporality : contradiction of genre and trend

The second characteristic of a work marked by a strong dialogic tendency is its unprecedented relationship with " the most vivid current events " (p. 152). This immediate treatment of current events conflicts with traditional generic constraints, which impose a distancing from the present in the representation of a mythical past, according to the principle recalled by Racine in the second preface to Bajazet, major e longinquo reverentia32.

So we shouldn't just notice Voltaire's borrowings from current events in the Dictionnaire philosophique, such as the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) as a backdrop to the article Liberté de penser, the allusions to the Seven Years' War (1756-1763) in the article Guerre, the Calas affair (1761-1765) behind Tolerance, the torture of the Chevalier de la Barre (1766) in the Torture article, the Equality article as a reaction to reading Rousseau's Second Discourse (1755), the Local Torts article as an extension of Beccaria's treatise33.

These borrowings contradict the taxonomic timelessness of the definition, constitutive of the Dictionary genre. They are not supporting examples, secondary historical colorations of the discourse : it's the real insofar as it undoes meaning, that it ruins any possibility of definition. The anecdote thus creates a tension between the brutal emergence of reality and the distancing generically necessary to representation. From this tension arises the semiotic arc, the pas-de-sens constitutive of the trait d'esprit.

The Japanese Catechism implements this contradiction of genre and trend, of the didactic timelessness of the Dictionary and the biting actuality demanded by the carnivalesque spirit, in an original way. The dialogue is in fact presented as a history of Japanese cuisine, i.e. as the most distanced representation possible of an ideologically neutral reality (cooking) in a distant country and in a distant era. This threefold distance of object, place and time from the revolts and struggles shaking the political news satisfies the generically constitutive requirements of the Dictionary, which claims to circumscribe objects of knowledge and not take sides in the upheavals of History.

At the same time, in the Age of Enlightenment, no Dictionary complied with such specifications. It's obvious to everyone that the Dictionary's taxonomic objectivity and totalizing (totalitarian ?) principle of collation constitute armed devices in an ideological war in which the timelessness of representation serves as an alibi for the partisan representation of current events : the deployment of dazzling erudition (Voltaire /// imitating that of a Bayle or a Moreri) is willing to allow himself this partisan supplement.

Le mot dialogique : travestissement allégorique et exercice jubilatoire

Voltaire, however, is not content, in the Catechism of the Japanese, with a partisan orientation of the exotic knowledge he claims to provide. The entire Japanese narrative is in fact an allegory of England's religious history Japan metaphorizes England cuisine metaphorizes religion. The allegory is such that, although many of the words in the speech are authentically exotic34, the narrative reports almost nothing genuinely Japanese. With the exception of two fleeting allusions, one to " war with the peoples of Tangut35 " (p. 89), the other to the insurrection of the woodcutter Toquixiro36 (taicosema, p. 93), the referent, the content of the discourse are English.

Alongside these " words represented37 " Japanese, Voltaire introduces in verlan figures, sects, the world of English and European religious conflict : the canusi, Japanese priests, are in fact pauxcopsies, or episcopal38, i.e. the clergy of the Anglican church. The Breuxeh are the Hebrews, the Pispates are the Papists, Terluh is Luther, Vincal - Calvin, the Batistanes are the Anabaptists, the Quekars - the Quakers ; Sutis Raho is Horace (Horatius), Recina - Racine.

As M. Bakhtine points out " appears a fundamentally new relationship with the word as literary material ". It's not just this ironically casual, deliberately and shamelessly puerile verbal creation, which gives for Japanese the hot words of European religious controversy, which it has travestied and somehow tumbled, which quotes a table talk put into verse by Horace as a precept " written in the sacred language " and evokes " a certain pastry which in Japanese is called pudding " (p. 91) ; this is the background to the narrative oriented towards the jubilant experience of the word, which identifies the content of the religious controversy with a culinary exercise, i.e. the production of words with the production of dishes, religious practice with a kitchen, a banquet, an ingestion.

.Cooking here is no mere metaphor : it designates the nature of this new, dialogical relationship to the word. The incomprehensible abstraction of theological discourse, the suffering linked to this incomprehensibility, is then turned over into the materiality of culinary consumption, into the enjoyment of the met. The culinary consumption of the word radicalizes the dialogic device by conjoining rhetorical abstraction and oral materialization, the dissemination of instituted discourse and the absurd concretion of revolting speech.

Dialogic syncretism : Socratic and Menippean dialogue

In the artistic field of " comico-serious39 ", Mikhail Bakhtin distinguishes two dialogic practices, Socratic dialogue on the one hand, menippean satire on the other. His aim is to show how Dostoyevsky, in the exercise of his novelistic poetics, operated a syncretism between these two practices and, more generally, how Western literature, particularly the novel, has been very largely innervated by this syncretic exercise, from Rabelais to Sterne, from Cervantes to Dickens40. But the Philosophical Dictionary, which Bakhtin does not mention41, implements a dialogism much closer to ancient satire and dialogue, as it /// like them, frees himself from the monological constraints of novelistic narration and representation.

." The Socratic conception of the dialogical notion of truth "

What characterizes the Socratic dialogue, according to M. Bakhtine, is first

" the Socratic conception of the dialogical notion of truth and the human thought that seeks it. The dialogical method of discovering truth is opposed to the official monologism that claims to possess a ready-made truth, and to the naive pretension of men who think they know something. " (M. Bakhtin, op. cit., p. 135.)

It would be futile, of course, to look for any objective filiation from the dialogues written by Plato to the Voltairean dialogues, and what M. Bakhtin designates as " Socratic conception of the dialogical nature of truth " has nothing to do with a Platonic philosophical content that it would be a matter of locating, of finding in Voltaire. In the Bakhtinian perspective of a general theory and global history of composition and genre, we note recurrences of forms, attitudes, processes ; these recurrences constitute a field of comic-serious, Socratic dialogue, but this does not mean that there has been a direct influence from a Platonic source text to a Voltairean target text that rewrites it42. In a word, Voltaire can very well recreate, recover a " Socratic conception of the dialogical nature of truth " without having been directly influenced either by Socrates, or even by any of the immediate disciples who transcribed (and inflected) his dialogues, Plato, Xenophon or Antisthenes.

The dialogical attitude that Bakhtin identifies here does not consist in opposing in dialogue two pre-established discourses of truth, nor even in expounding a discourse of truth that a conventional interlocutor would be content, for form's sake, to accompany, to relaunch within the framework of a dialogue of pure complacency43. To this rhetorical genre of dialogue, Bakhtin contrasts dialogical practice, which places the discourse of ready-made truth, the instituted discourse, outside itself. The aim of dialogue becomes the dismantling of this discourse, which will remain in the text in a collapsed form, or in other words, disarticulated, fragmented, ruined. Voltairean dialogue feeds on this collapsed monologism, ordering and arranging itself around it. The reign of this official monologism is depicted at the beginning of The Catechism of the Japanese by the account of the bygone era when the grand lama, i.e. the pope, " decided sovereignly on their eating and drinking " (p. 91), i.e. on all their religious affairs, and more precisely on the bread and wine of the Eucharist, which constitute their visible figure and spiritual quintessence. The culinary metaphor is neither arbitrary nor anodyne it concerns the central dogma of every Christian catechism and, disguising it, figures it in abyme, since precisely the theological challenge of the Reformation consisted in renouncing transubstantiation and accepting the Eucharist as a mere metaphor44.

The story begins when this sovereign decision by the grand lama is challenged by the canusi, who intend to share with him the exercise of this discursive sovereignty :

" The great lama had a pleasant habit, he thought he was always right ; our daïri and our canusi wanted to be right at least sometimes. the great lama found this claim absurd our canusi would not budge, and they broke with him forever. " (P. 90.)

The burlesque story of this schoolyard breakup, which parodies one of the bloodiest episodes, one of the deepest and most enduring ruptures in European history, is presented by Voltaire as the end of /// This is the definitive, irrevocable end of official monologism, i.e. of that time, of that world where the great lama was always right. Everyone wants to be right some of the time it's in this shattering of instituted, official monological truth that the dialogic nature of truth is vindicated.

To be right, to be reasonable : the expulsion of discourse from dialogue

But this dialogical nature of truth is itself no more than a delusion without the Socratic approach that reverses its certainty, however partial, however splintered. It's not a question of "being right sometimes " (that's the mainspring of a perpetual civil war), but of being reasonable, i.e. of definitively renouncing that anyone is ever totally right, of renouncing discourse, even fragmented discourse. Such, at least in the Dictionnaire philosophique, is " the Socratic conception of the dialogical nature of truth ", which Voltaire formulates thus :

" we persecuted, tore apart, devoured each other for nearly two centuries. Nos canusi voulaient en vain avoir raison ; il n'y a que cent ans qu'ils sont raisonnables. " (P. 90.)

This transition from " being right " to " being reasonable " is fundamental, as it constitutes the universal basis of the dialogical device, marked by the externalization of instituted discourse (which no interlocutor claims to embody or even defend anymore) and by connivance in separation (connivance of reasonable beings, but separation consecutive to the shattering of monological truth).

" to be reasonable " forbids recourse to monological discourse and poses the double constraint that serves as the starting point for the exercise of dialogical thinking : summoned to define his new, dialogical relationship to truth, the interlocutor no longer seeks to be right, and therefore cannot spout a discourse. All discourse is henceforth perceived as an object external to the dialogical device, apprehended with distance, skepticism and irony by the interlocutors more or less complicit in the dialogue. Discourse thus becomes a representation, a figure. Imported into the dialogic device, it becomes stylized as a word, metaphorized as a line, figured as an allegory. The double allegory of culinary and Japanese in the Catechism of the Japanese is characteristic of this process of figurative reintroduction of instituted monological discourse, which has been previously shattered and projected outside the dialogical space : the Japanese and the Indian can converse peacefully because the great lama no longer exercises the empire of his sovereign decisions over the territory of the dialogue.

.It is therefore through the metaphor of cooking that the Japanese can express, formulate the dialogic " Comment " of " être raisonnable ", can say what it is to be reasonable even as being reasonable involves renouncing the claim to a dire :

" If there are twelve caterers, each of whom has a different recipe, will it be necessary for them to cut each other's throats instead of dining ? On the contrary, each one will make good food in his own way at the cook who pleases him more. " (P. 90.)

We've already had occasion to highlight the liberal economic model that underpins, time and again, Voltaire's expression of the regime of tolerance : the reign of tolerance is a reign of free competition, of the freedom of the market. Everyone chooses their caterer, just as everyone buys and sells on the stock market45 : the revolution of tolerance is a capitalist revolution.

IV. The banquet as an imaginary form of the dialogical device

" the dialogized word of the banquet "

But at the same time this culinary allegory refers back to the very ancient model of the συμπόσιον, which Bakhtin considers one of the oldest expressions of menippean satire, i.e. of the second /// dialogical practice in the field of " comico-serious ", after the Socratic dialogue.

" The symposium (conversation during a banquet) already existed at the time of the "Socratic dialogue" (we have examples in Plato and Xenophon), but flourished above all, with multiple variants, in subsequent eras. The dialogued word at the banquet was endowed with special privileges (initially of a cultic nature) : the right to special freedom, spontaneity, familiarity, unusual sincerity, eccentricity, ambivalence combining praise and insult, seriousness and comedy. By its nature, the symposium is a purely carnivalesque genre. " (M. Bakhtine, op. cit., p. 167.)

The Catechism of the Japanese is not itself a symposium, but thematizes the symposium as object, as figure of the dialogical conversation. This mise en abyme of the symposium as the allegorical content of dialogue is undoubtedly symptomatic of a late, somewhat mannerist expression of an already worn-out dialogical device. However, all the characteristics of the " dialogical word of the banquet " are to be found in the content of the narrative.

Mikhail Bakhtin first recalls its primitive cultural dimension : the word of the banquet is originally a religious performance, and so it's only natural that its carnivalesque thematization in the Voltairian dialogic device identifies the form of the word46 (the culinary allegory) with a religious content.

The freedom, familiarity and sincerity of the banquet word is also thematized in the Catechism of the Japanese narrative, since the description of the different cuisines that coexist peacefully under the Japanese (English) regime of tolerance tabulates as a social expression of this freedom, familiarity and sincerity, conquered throughout Japanese society and constituting this Japanese fictional world : Japanese fiction unfolds the alternative world of the banquet, exactly as in the ancient συμπόσιον the word of the banquet constitutes and unfolds this same alternative world, where instituted monological discourse falls, and with it its hierarchies, its constraints, its imposed silences47.

The religious discourse, between culinary allegory and economic satire

Finally, the carnivalesque ambivalence of symposiac speech is fully expressed in the allegory of the Japanese Catechism, which functions as both a buffoonish parody and a serious affirmation of Voltairian values of religious tolerance and renunciation of the exercise of dogmatic speech.

This carnivalesque ambivalence manifests itself in the permanent reversal of allegory into satire, that is, of serious figuration into madcap caricature, which ironic accentuation pushes towards trivial brutality, bordering on nonsense. Such is the case with the description of the Jews and their dietary prohibitions:

." There are first of all the Breuxeh*, who will never give you blood sausage or bacon they are attached to the old way of cooking they would rather die than prick a chicken " (p. 9148).

The first proposal is hardly metaphorical, since it describes the actual prohibitions of cachroute. " L'ancienne cuisine " already constitutes, if not exactly a metaphor, at least a parodizing parodic stylization, where cuisine no longer simply designates the dietary prohibitions of the Jews, but already, more globally, the Old versus the New Testament, the Old Law versus the Christian institution, the Synagogue versus the Church. As for poulet piqué, it's the word that makes the image, crystallizing the point, the pas-de-sens and the reversal of the word /// of spirit.

" We can therefore speak here of an embryo of the image of the idea. We also observe a free creative attitude towards this image. " (M. Bakhtine, op. cit., p. 157.)

Piquer de la viande is said of meat that is larded with large lardons, according to the Dictionnaire de l'Académie49. But pricking a chicken is a challenge because of the carcass: the operation is comical because it's virtually impossible50. Finally, of course, assuming that a chicken can be pricked, thus larded, it then ceases to be kosher, becomes unfit for Jewish consumption : the carnivalesque process, identified with the culinary process, reverses lawful food into grotesquely unlawful food, and condemns to death, for laughs, the Jew faced with the larded chicken.

.The whole game of carnivalesque ambivalence, fused here in the figure on which the witticism pivots, lies in the polysemy of the verb piquer. To prick, does not yet mean, strictly speaking, to steal, but the expression " piquer les tables ", which is at the origin of this meaning, has been attested since the 17the century51.

Or the Jews, who don't prick a chicken, even under torture, are " moreover great calculators ", in other words they prick the money of " eleven other cooks ". In this way, the piqué chicken is a way of engaging with the eternal theme of the rapacity of usurious Jews.

Finally, " piquer " produces the effect of the witticism because the image of the piqué chicken materially and comically figures the effect of the rhetorical point, perfectly superimposing the slash of the knife and the word, the culinary pique and the verbal pique.

Voltaire makes the same shift from culinary allegory to economic satire, from the comic figure of the banquet to the grating figure of the relationship to money, when he moves from the Jews to the Catholics :

" il y a ensuite les Pispates, qui certains jours de chaque semaine, & même pendant un temps considérable de l'année, aimeraient cent fois mieux manger pour cent écus de turbots, de truites, de soles, de saumons, d'esturgeons que de se nourrir d'une blanquette de veau, qui ne reviendrait pas à quatre sous. " (P. 91, graphie éd. Varberg.)

Papists pride themselves on eating lean on Fridays and during Lent, but what was originally a dietary penitence has, among well-to-do Catholics, been totally perverted : we certainly continue to eat fish, but in such abundance and with such refined dressing that nothing remains of the religious prescription of frugality. Like the lard of the Breuxeh, the fish of the pispates is not strictly speaking a metaphor : the banquet table overloaded with the most varied and expensive fish literally describes the Catholic religious practice that Voltaire denounced and ridiculed on numerous occasions52. The banquet is literal before it is allegorical. Superimposed on the generous, overflowing picture of the carnival banquet, however, is the pecuniary valuation of this banquet, " one hundred écus " for the penitential fish, against the " four sous " to which would accrue " a blanquette de veau ", forbidden though it is on lean days. The laughing, joking parody then turns to satire, which no longer laughs at all : either cautious or mansuétude, Voltaire here doesn't develop, as he will in the Requête à tous les magistrats du royaume in 1769, a discourse denouncing social inequalities that force the poor to fast, forbidden from blanquette (or petit salé, mutton or cheval de voirie depending on the version) while the rich find in /// the ritual of lean days, a refined opportunity to vary the pleasures of the mouth.

The totalizing banquet, economic model and poetic model

Then comes the turn of the Protestants, of " nous autres canusi ", i.e. Japanese priests, otherwise known as Anglican bishops, or pauxcospie. Protestant cuisine is not a matter of consumption beef and " poudding ", the English ordinary, are quickly dispatched, in favor of a deepening of knowledge. As a universal cuisine, Protestant cooking is identified with the encyclopedic knowledge of cuisines from the history of the world :

" No one has more aproved than we the Garum of the Romans, has better known the onions of ancient Egypt, the grasshopper paste of the first Arabs, the horse flesh of the Tartars, & there is always something to learn from the books of the Canusi, who are commonly called Pauxcospie. " (P. 91, Varberg spelling.)

Episcopal cuisine produces recipe books that neither metaphorize nor represent any religious dogma or specific dietary practice, but found the genre of the dictionary, and more specifically Bayle's dictionary, which in so many ways served as a model for the Voltairian dictionary. Here, culinary allegory becomes autonomous, losing touch with its religious referent. The fictional world of the banquet becomes an autonomous world and the basis, at once phantasmagorical and serious, of a new knowledge, newly expressed and represented.

With Lutherans, Calvinists, Anabaptists, Quakers, the culinary metaphor is diluted, only to return when evoking the last sect, the deists, named diestes, which probably plays on digeste53, for they alone eat everything :

" those give dinner to everyone indifferently, & you are free with them to eat whatever you please, larded, barded, without bacon, without bard, with eggs, with oil, partridge, salmon, grey wine, red wine, all that is indifferent to them [...]. il est bon seulement que nos Diestes avouënt que nos Canusi sont très savants en cuisine, & que surtout ils ne parlent jamais de retrancher nos rentes ; alors nous vivrons très paisiblement ensemble. " (P. 92, graphie Varberg.)

The Diestes banquet crowns and absorbs all other banquets. Food tolerance not only metaphorizes religious tolerance it produces carnivalesque abundance. Here again, the allegory of the banquet slips into satire, expressed once again in the economic order: just as the rapacity of the scheming Jews, or the hypocritical Lenten pomp of the wealthy Catholics, were the flip side of their respective banquets, the Deist banquet is conditioned by the hypocrisy of a discourse that legitimizes the financial privileges of the Anglican Church. Civil peace rests on the acceptance of this religious and economic inequality religious tolerance is obtained at the price of these consented privileges and a political renunciation.

The total banquet of the Diestes is opposed by the rebellious, insurrectionary banquet of the " stubborn ", who dare to confront the king directly :

" but if stubborn people want to eat sausages under the king's nose, for which the king will have an aversion, if they assemble four or five thousand, armed with grills to cook their sausages, if they insult those who do not eat them ? " (P. 93.)

The sausage feast is the authentic carnivalesque feast, which can be compared to Gargantua's54 tripe feast. Yet this feast described, promoted not by the Japanese like the previous ones, but by the Indian, his interlocutor, is forbidden. The denigration of the king, his " indétronisation55 " carnivalesque, the central ritual of the carnival and the cult ideological core of the comic-serious artistic field, is suggested, brought to representation by the Other of the dialogue, only to be immediately revoked, struck down with prohibition. Carnivalesque renovation constitutes the horizon of the dialogic device, which nevertheless places itself, vis-à-vis it, in a position of cautious withdrawal.

The other banquets in the Dictionnaire philosophique

The motif of the banquet as a figural frame for the dialogical device does not only appear in the Japanese Catechism. In the fourth conversation of the Chinese Catechism, the Chaldean story of the pike Oannes and its eggs gives rise to a culinary allegory very close :

" Chaldean priests had taken to worshipping the pikes of the Euphrates. They claimed that a famous pike named Oannes had once taught them theology, that this pike was immortal, that he was three feet long, & a small crescent on his tail. It was out of respect for this Oannes, that it was forbidden to eat pike. There arose a great dispute among theologians, as to whether the pike Oannès was laité, or œuvé. The two parties excommunicated each other, and several times came to blows. This is how King Daon managed to put an end to the disorder. He ordered a rigorous three-day fast for both parties after which he summoned the followers of the egg pike, who attended his dinner he had a three-foot pike brought to him, with a small crescent on its tail : Is this your God ? he said to the Doctors : Yes, Sire, they replied, because it has a crescent on its tail. The king ordered the pike, which had the most beautiful milk in the world, to be cut open. The pike was eaten by the king and his satraps, to the great displeasure of the egg theologians, who saw that the God of their adversaries had been fried.

As soon as the pike was eaten, the king sent for the eggs. The doctors of the opposing party were also sent for: they were shown a three-foot God with eggs and a crescent on his tail; they ascertained that this was the God Oannes, and that he was laity; he was fried like the other, and recognized as œuvé. Then, the two parties being equally foolish, and not having had breakfast, the good King Daon told them he had only pike to give them for their dinner, and they ate them greedily, either œuvé or laité. The civil war ended everyone blessed the good King Daon & the citizens since that time had as many pikes as they wanted served for their dinner. " (Pp. 77-78, graphie Varberg.)

Voltaire borrows for this apologue, which he has already sketched out in Zadig56, a mythical setting that comes from Bérose57, whose abbé Banier had evoked (denigrated ?) the story, attempting to rationalize it, in La Mythologie et les fables expliquées par l'histoire58. But neither the content nor the object of the Chaldean myth has anything to do with Voltaire's apologue Annes, half man, half fish, marks the beginning of history and constitutes " the Tradition of the Chaldeans on the origin of the world " (Banier, p. 80) ; arrived from the sea, he brings to the Chaldeans " some principles of Philosophy, & some connoissance of ancient traditions " (Banier, p. 79).

Berossus does speak of an egg, but of the egg from which Oannès came, and not of those he could himself produce :

" What he says next, that it was published that he had come out of the primitive egg, from which all other beings /// avoient été tirés, n'est fondé que sur la ressemblance de son nom, avec le mot grec Oon, qui signifie un Oeuf ; ou plutôt sur l'ancienne fable qui supposoit que tout étoit sorti d'un œuf. " (Banier, op. cit., p. 79.)

As for King Daon, it comes from Apollodorus, for whom there would not have been one Annnes, or Annedotus, but several animals resembling him :

" Le même Apollodore parle d'un quatriéme Annedotus, qui étoit aussi sorti de la mer, sous le regne de Daonus " (Banier, op. cit., p. 80).

A Chaldean king Daon, a mythical king of whom we know nothing, would therefore have been confronted with a kind of Oannes, and Voltaire embroiders from this very simple canvas59.

The fish's milt is its spermatic fluid : milt pike therefore refers to the male pike, while œuvé pike is the female. But it's very difficult to determine the sex of a pike without cutting it open, which explains the guessing game King Daon plays. The theological controversy that Voltaire portrays through this quarrel over the sex of the divine pike is also burlesquely based on biology experiments of Voltaire's contemporaries, first Needham and then Buffon60.

So here we find all the carnivalesque ingredients of comic-serious dialogic fiction : the tragic question of religious dissension, which was already the subject of the culinary allegories in the Japanese Catechism, is translated into a burlesque apologue set at an indetronization banquet, where the consumption of sacred fish ridicules theologians, but bolsters royal authority. The joyous, festive transgression of dietary prohibitions then leads to an abundance of cocagne : " & the citizens since that time had as many pikes as they wanted served at their dinner. "

The apologue that brings the fanatics' dissension to an end with a feast and banquet starts from an obscure myth, remote from actuality in both time and space. But through this myth, he figures the contemporary, burning question of tolerance: dialogism here consists in making the reality present in the mythical representation heard, turning the exotic esotericism of Oannès into an allegory of the religious persecution raging in Europe at the very moment Voltaire was writing. But in this rhetorical process of metaphorical figuration, the buffoonish dimension of allegory is essential the apologue has no meaning, no univocal moral it does not constitute a discourse. How can " both parties being equally foolish " suddenly resolve to eat " greedily " pike ? Here, the party game prevails over political reasoning, the logic of the carnival and its ritual sequences over the discourse of history and its social mechanisms.

.Finally, the myth of Oannès is a myth of origins, which Voltaire travesties into a killing. In the story told by Berossus, Annes emerges from the sea as a beginning he marks the beginning of culture and history, through the knowledge he brings to mankind. In Voltaire, on the other hand, the parodic banquet to which the good King Daon invites the rival religious factions consists in the killing and eating of the pike Annes, i.e. symbolically not only in the devouring of the god, but in the extinction of his religion. Yet the killing marks the beginning of prosperity, just as the arrival of Berossus' Oanes marked the beginning of Babylon's glory. The dialogic narrative is a threshold narrative, where the threshold of death and the threshold of life are superimposed61.

If, from the theological and philosophical point of view of Voltairian allegory, the exact nature of the fish put to death is of little importance /// The banquet unfolds in three stages. The banquet takes place in three stages: first, the " partisans du brochet aux œufs " then the " docteurs du parti contraire " finally, the general, gulping consumption of pike " soit œuvés, soit laités ". On the surface, the first two phases, which aim to ridicule both factions in turn, are symmetrical. However, if King Daon eats a milky pike (male) in front of the supporters of the œuvé pike (female) and satisfies them at first, it's again a milky pike that is fried in front of the supporters of the milky pike, before being " recognized œuvé ".

Voltaire obviously plays on the difficulty of identifying the sex of pike, and even on the hermaphroditism of certain specimens, but stages, exclusively, the killing of the paternal god, whose masculine identity is underlined by the " fusiform " character of the fish. Finally, the pike has another characteristic, which dictionaries underline:

" Pike. s. m. Freshwater fish, white, long & strong voracious, which eats others. The tooth of the Pike is highly venomous, & forms part of the jawbone. Lucius.

☞ In some Pikefish are found eggs & a milt at the same time. This leads to the conclusion that they are hermaphrodites.

☞ It is prepared in kitchens in several ways. The eggs of brochet excite nausea, & purge violently. Its flesh is white, firm, quite nourishing, indigestible for many people ; although the Vocabulistes assure that it is easy to digest. " (Dict. de Trévoux, 1771.)

Notes

" How ! said the heated scholar, don't you at least know the difference between pagans, Christians and Muslims don't you know Constantine, and the history of the popes ? We've heard a lot about a certain Mohammed," replied the Asian.

It's not possible, replied the other, that you don't at least know Luther, Zuingle, Bellarmin, Œcolampade*. I'll never remember those names," said the Chinaman. He then went out, and sold a considerable portion of pekoe tea and fine grogram**, from which he bought two beautiful girls and a moss, whom he brought back to his homeland worshipping the Tien, and commending himself to Confucius.

For me, witness to this conversation, I saw clearly what glory is ; and I said : Since Caesar and Jupiter are unknown in the most beautiful, most ancient, most vast kingdom, /// the most populated, the best policed of the universe, it suits you well, O governors of a few small countries ! O preachers of a small parish, in a small town ! O doctors of Salamanca or Bourges ! O small authors ! O ponderous commentators ! it suits you well to claim reputation. "

* Jean Husschin dit, Œcolampade (1482-1531) led the Reformation in Basel, Switzerland. Cardinal Robert Bellarmine (1542-1621), a famous inquisitor, took an active part in the trial of Giordano Bruno, whom he had burned in 1600, and Galileo, whom he ordered to stop teaching Copernicus' heliocentrism as truth in 1616.

** Grogram (deformation of gros-grain) is a coarse fabric, a mixture of silk and mohair, or raw silk.

" The caloyer. - Would you be a Jew ? are you a Christian of the Greek rite, or the Armenian, or the Cophtic, or the Latin ?

Honest man. - I adore God, I strive to be just, and I seek to educate myself.

The caloyer. - But don't you give preference to Jewish books over the Zend-Avesta, over the Veidam, over the Alcoran ?

The honest man. - I fear I have not enough light to judge books well, and I feel I have enough to see in the great book of nature that one must adore and love one's master.

The walnut tree. - Is there anything that embarrasses you about Jewish books ?

The Honest Man. - Yes, I admit that I find it hard to understand what they say. I see in them some incompatibilities that surprise my feeble reason. "

Then follows an enumeration of the contradictions and obscurities of the Old, then the New Testament. But Caloyer is more accommodating than Logomachos. As in the catechisms of the Dictionnaire, he ends up agreeing with his interlocutor, and the ending evokes that of the Catechisme du curé :

" Le caloyer. - Come on, come on, I'm as much of a caloyer as you are.

" The caloyer.

The honest man. - My God, bless this good walnut tree!

The walnut tree. - My God, bless this honest man ! "

The honest man. - Ah, master ! that is, if you didn't hope for heaven, and if you didn't dread hell, you'd never do any good works. [...]

The excrement. - Ah, sir, you're a Fenelonist.

The honest man. - Yes, master.

The excrement. - I'll report you to the official of Meaux.

Honest man. - Go, denounce. "

In the 16th century, several treatises inspired by Erasmus' Institution of the Prince Christian (Institutio Principis Christiani, saluberrimis referta praeceptis), 1515 : L'Instruction d'ung jeune prince pour ce bien gouverner envers Dieu et le monde, Paris, 1517 Gilles d'Aurigny, Le Livre de police humaine, ... Ensemble un brief recueil du livre d'Érasme qu'il a composé de l'enseignement du prince chrestien, Paris, L'Angelié, 1549 ; François Patrice, De l'Estat et maniement de la chose publique; ensemble du gouvernement des royaumes et instruction des princes, ... Plus y est adjousté un petit abrégé du livre d'Érasme, touchant la doctrine et enseignement du prince chrestien, Paris, 1584 ; Claude Joly after Erasmus, Codicile d'or ou petit recueil tiré de l'institution du prince chréstien, 1665.

In the 17th century, the dialog form appears: Instruction du prince chrestien, par dialogues between a young prince and his principal, with a meditation on the vow of David, au psaume CI, Leiden, 1642.

The Fronde saw the flowering of parodic and/or satirical mirrors of the prince: Deacon Agapet, Le Miroir des roys et des /// princes, extraict d'un docteur grec et présenté à très-hault et très-illustre prince Dom Antoine, roy de Portugal, par M. Nicolas de Nancel ; The Mirror to two opposing faces, one praising the ministry of the faithful minister, the other condemning the conduct of the evil and unfaithful usurper and enemy of the prince and his State, 1644 (1649) ; J.-J. de Barthès, Les veritez royales. ou l'instruction du Prince chrestien, Paris, Moreau, 1645 ; Miroir des souverains où se voit l'art de bien régner, Paris, 1649 (mazarinade) ; Le Miroir des souverains, où se voit l'art de bien régner, et quelles sont les personnes qu'ils doivent élire pour être leurs commensaux.... and their ministers of state, Paris, Noel, 1649.

Some European mirrors translated into French : Juan Antonio Vera y Figueroa, Le Miroir des Princes, présenté à tous les monarques de ce siècle, 1683 (vie de Charles Quint) ; Le Miroir des Princes ou le Dénouement des intrigues les plus secrètes des Cours de l'Europe... Avec des réflexions sur le traité de Trêve, conclu à La Haye le 29 de juin de cette année, 1686.

Syntheses on the question : Michel Senellart, Les Arts de gouverner : du regimen médival au concept de gouvernement, Seuil, 1995 ; Myriam Chopin-Pagotto, " La prudence dans les Miroirs du prince ", Chroniques italiennes, n°60, 4/1999, pp. 87-98. http://chroniquesitaliennes.univ-paris3.fr/PDF/60/Chopin.pdf

From England, Peterborough had first docked in Lisbon (June 1705), where the dialogue in the Liberté de penser article is apparently supposed to take place. He also died in Lisbon in 1735. Voltaire is said to have met him during his stay in England : see the Histoire de Jenni, chap. IV, Contes en vers et en prose, ed. Menant, Garnier, 1993, t. II, p. 465.

Christiane Mervaud points out, Ritual from Pope Paul V in support (1614), that grasshoppers are not strictly speaking excommunicated, but that the parish priest can perform " a blessing of the fields to drive away the grasshoppers ".

I promise, says the intendant des Menus ; but finish revealing your mysteries to me. Why of all those to whom I have spoken of this affair, is there not one who does not agree that excommunication against a company pledged by the king is the height of insolence and ridicule ? "

The conversation ends with a conjuring : " I like your frankness, says le Menu. Let old nonsense peacefully subsist; perhaps it will fall out of itself, and our grandchildren will call us good people, as we call our fathers fools. Let the tartufes scream some more, and from tomorrow I'll take you to the comedy of Tartufe. " (Voltaire, Conversation de M. l'intendant des Menus en exercice avec M. l'abbé Grizel.) The abomination of excommunication is spectralized into " old sottises ", themselves identified with the imbecility of our fathers. The derisory figure of the imbecile father remains as a ghost that should be left to peacefully subsist.

It was only right that a Spaniard should deliver the land from this monster, since a Spaniard had given birth to it. " Voltaire takes as his starting point a news item from 1770, the arrest of a bigamous Spanish soldier, whom Charles III of Spain ordered tried by the tribunal of Count Aranda rather than the Inquisition. Voltaire then compares the Count of Aranda to Saint Dominic, the conjuror to his spectre.

The Latin formula, passed into proverb, is borrowed from Tacitus, Annales, I, 47.

.The great lama thus effectively waged war on the peoples of Tangut...

We try to avoid as far as possible the term " genre ", which Bakhtin uses and abuses : the category of " comico-serious " serves him precisely to deconstruct the notion of genre for want of those of " champ " and " dispositif ", which have not yet been invented.

Voltaire insists several times in the /// Dictionnaire philosophique on this filiation which arouses in him the greatest mistrust :

" Some Philosophers of the Sect of Plato became Christians. This is why the Fathers of the Church, of the first three centuries, were all Platonists. " (Art. Christianisme, p. 117.)

" Platonism helped a great deal in the understanding of its dogmas. The Logos, which for Plato meant wisdom, the reason of the Supreme Being, became for us the Word, & a second Person of God. A profound metaphysics, & above human intelligence, was an inaccessible sanctuary, in which Religion was enveloped. " (Art. Religion, 3e question, p. 342.)

" The belief in resurrection is much older than historical times. [...] Plato relates that Heres was resurrected for only fifteen days. The Pharisees, among the Jews, did not adopt the dogma of the resurrection until a very long time after Plato. " (Art. Resurrection, p. 348.)

Despite this defiance, Voltaire manifests an ambivalent attitude towards " divine Plato ". In the article Âme, he certainly mocks his metaphysical galimatias : " Finally, according to the divine Plato, [the soul] is a compound of the same and the other " (p. 11). The same type of mockery in the article Atheist, atheism, is counterbalanced by the recognition of a sublime beauty of Platonic thought : " Vanini was keen to renew that beautiful sentiment of Plato, embraced by Averroës, that God had created a chain of beings from the smallest to the greatest, the last link of which is attached to his eternal Throne ; idea, in truth, more sublime than true, but which is as far removed from Atheism, as the being of nothingness. " (P. 39.)

Admired and ridiculed, Plato is evoked only at the periphery of Voltairian discourse, here as Vanini's intertext, elsewhere as Leibnitz's counterpoint, in the article Tout est Bien : " It was a fine noise in the Schools, & even among people who reason, when Leibnitz, paraphrasing Plato, built his edifice of the best of all possible worlds, & that he imagined that everything was for the best. " (p. 54). At the end of the article Chain of Created Beings, it's to Newton that Plato serves as a foil : " O Plato so much admired ! we have only told fables, & there has come to the Isle of Cassiderides, where in your time men went naked, a Philosopher who has taught the earth truths as great as your imaginations were puerile. " (P. 102.)

The light-hearted mockery of Plato appears inseparable from a certain admiration, which Voltaire confesses at the start of Chain of Created Beings : " The first time I read Plato, & that I saw this gradation of beings rising from the lightest atom to the Supreme Being, this scale struck me with admiration ; but having looked at it attentively, this great phantom vanished, as formerly all apparitions fled in the morning at the crow of the cock. " (P. 100.) Curiously, this admiration which at first paralyzes, but which the lights of reason then conjure up, is not unrelated to the torpedo effect Socrates produced according to Meno, but which Socrates himself says he was first struck by (Menon, 80a).

From 1765 onwards, Voltaire's judgment becomes more nuanced, as evidenced, for example, by the laudatory evocation of the article Philosophe, which dates from 1765 : " One cannot read certain places in Plato, & sur-tout l'admirable Exorde des Loix de Zaleucus, without feeling in one's heart the love of honest & generous actions. "(P. 323.)

We must not forget, on the other hand, that in the camp of philosophers it is agreed to name Diderot brother Plato, and that it is under this /// name that Voltaire refers to him with deference in his correspondence.

We also say, Piquer de gros lardons, to say, Larder de meat with gros lardons. Piquer une daube avec de gros lard. " (Dictionnaire de l'Académie, 4e edition, 1762.)

Similarly, " We also call, piquer meat, when we lard it close by, with small lardons : larido interpungere ; that we pique an orange, a lemon, when we drive cloves into it, that we pique candied walnuts with lemon peel. " (Dictionnaire de Trévoux, ed. 1771, tome VI, pp. 793-4.)

The meaning is ancient, as we find it as early as the first Dictionnaire de l'Académie : " On dit, Picquer de la viande, pour dire, Larder de la viande avec de petits lardons & prés à prés. Picquer des perdaux. ces lapreaux sont bien picquez. on a picqué ce rosti fort proprement. " (Dictionnaire de l'Académie, 1ère édition, 1694.)

The priests " prove in three points and by antitheses [...] that a man who has two hundred écus of tide served on his table on a Lenten day inevitably makes his salvation, and that a poor man who eats for two and a half sous of mutton goes forever to all the devils. " (Art. Guerre, p. 223.)

" We are told that during Lent it would be a great crime to eat a piece of rancid bacon with our brown bread. We even know that in the past, in some provinces, judges condemned to the ultimate torture those who, pressed by a devouring hunger, would have eaten during Lent a piece of horse or other animal thrown into the street while in Paris a famous financier had horse relays that brought him fresh tide from Dieppe every day. He regularly went to Lent he sanctified it by eating fish with his parasites for two hundred écus : and we if we ate for two liards of disgusting and abominable flesh, we perished by the rope, and we were threatened with eternal damnation. " (Request to all magistrates of the royalty, 1769, Part I.) The financier in question is Bouret, to whom Voltaire had sent a " copy of this Tolerance not tolerated ", unfortunately seized by the police (letter to D'Alembert, Jan. 8, 1764).

It's interesting to see how Fourmont turns Oannes into a Reformer hero of primitive Religion, while Banier is preoccupied with stripping him of his divinity and minimizing his action.

61 M. Bakhtine speaks of Apuleius as " pseudo-murder on the threshold " (p. 182). "Carnivalization penetrates to the philosophical-dialogical heart of the menippean. We have seen that this genre is characterized by the stripping down and purity of the ultimate questions about life and port, as well as by extreme universalism (it knows neither developed philosophical argumentation nor particular problems). Carnivalesque thought gravitates around the same questions, only it doesn't find an abstract, philosophical, religious or dogmatic solution to them, it plays them out in the concrete, sensitive form of acts and gestures. " (M. Bakhtine, op. cit., p. 183.)

And further on, when M. Bakhtine returns to Dostoyevsky : " Let us recall that the menippean is the universal genre of ultimates questions. In it, the action takes place not only "here" and "now", but in the entire universe (earth, hell, heaven) and in eternity. [...] Its main heroes stand on the threshold (between life and death, truth and lies, reason and madness), and they are presented as voices that resound "in the face of earth and heaven". " (P. 198.)