Preparation for Voltaire's portrait - Maurice-Quentin de La Tour

The Dictionnaire philosophique from the Kehl edition of Voltaire's complete works1 constitutes something of a textual monster : the five sections of his Esprit article have various origins and do not correspond to any premeditated composition by their author. But they attest to Voltaire's ongoing attention to the term, and his awareness that he was destined to define it and identify with it. Voltaire not only defined wit, he embodied it. It should come as no surprise that Esprit is one of the few articles Voltaire delivered to Diderot for the Encyclopédie. But paradoxically it's not in this 1755 issue, full of doubt and false pretenses, that we should look for a simple definition from which to start. Rather, 11 years earlier in 1744, in the Lettre sur l'esprit that follows Mérope : esprit is defined there first in relation to tragedy, and thus marks for Voltaire a fundamental contradiction, and one that defines him : he is tragedy and he is the spirit of the Enlightenment.

" What we call spirit is sometimes a novel comparison, sometimes a fine allusion : here the abuse of a word that is presented in one sense, and implied in another there a delicate relationship between two uncommon ideas ; it is a singular metaphor it is a search for what an object does not present at first, but for what is indeed in it It's the art of uniting two distant things, or of dividing two things that appear to be joined, or of opposing one to the other it's the art of only half-saying one's thoughts, to keep them guessing. Lastly, I'd tell you about all the different ways of showing wit if I had more but all these brights (and I'm not talking about false brights) are not suitable, or very rarely suitable, for a serious work that should interest. The reason is that it's the author who appears, and the public only wants to see the hero. And this hero is always either in passion or in danger. Danger and passion do not seek out the spirit. Priam and Hecuba don't write epigrams when their children's throats are slit in fiery Troy; Dido doesn't sigh in madrigals as she flies to the pyre on which she is about to immolate herself. Demosthenes has no pretty thoughts when he leads the Athenians to war if he did, he'd be a rhetorician, and he's a statesman2. "

The mind establishes a relationship, that's the essential starting idea. The relationship is made between what an object presents, its façade, and " what is indeed in it ", but which we don't perceive at first sight. The mind establishes between this luring façade and this reality " indeed " a reunion based on a division or opposition. This reunion, this junction, is brilliant, producing the brilliance of a diamond. The brilliance of the mind defines the quality of its effect but at the same time, it strikes the mind with suspicion, even opprobrium. Because it is brilliant, wit is not serious, not worthy of serious work.

To understand the rest of Voltaire's reasoning, we need to bear in mind what he means here by serious work these are tragedies. On the tragic stage, the audience " only wants to see the hero " in other words, they only want to hear the declension of his character, his tragic façade, in what he says. If an actor slips a witty word into his tirade, it's the author, it's Voltaire, who's in charge. /// all of a sudden takes the floor through his character, and this is what the mimetic convention of classical theatrical representation does not allow. There is then disconvenience : " all these brilliant... don't convive at all or convive very rarely to a serious work ". Not only does this intrusion of the author behind the actor break the theatrical illusion, it constitutes a fault of taste : the spirit is light, fit for epigrams, madrigals, pretty thoughts, when the tragic action is heavy with passion and danger.

But isn't this heroism of the stage, which apparently makes the intrusion of the witty word impossible, whose lightness is incompatible with the serious genre, precisely the facade that the line comes to crack, which it needs to establish the rapport, the junction, the incongruous comparison, the salient metaphor ? Without this heroism, which forbids the spirit and which the spirit dismantles, there is no spirit. There is therefore a necessary heroism of the spirit, and through it the spirit necessarily exerts a disconvenience, which is the symbolic translation of what technically manifests itself as division, opposition in reunion, in the relationship of facade and reality itself.

Let's take an example.

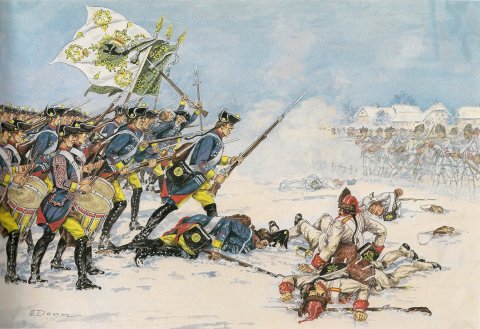

I. Heroic butchery : deconstructing the battle

Chapter III of Candide opens with a description of the battle fought between the Avars and the Bulgars, a battle into which Candide finds himself thrown to his utter terror and incomprehension. The bravura piece at the start of this chapter, which Voltaire calls "heroic butchery", has had a major literary impact: the device was taken up by Stendhal in La Chartreuse de Parme (1839), when he describes Fabrice del Dongo thrown into the middle of the battle of Waterloo3, by Tolstoy in War and Peace (1865-1869)4, when he recounts how Prince Andre Bolkonski wounded at Austerlitz is spotted by Napoleon5, and even to some extent by Claude Simon in La Route des Flandres (1960), to evoke the heroic yet derisory depiction of the death of Captain de Reixach6. What is this device? A character, the story's protagonist, finds himself caught up in a scene of war. There's a heroic beauty to this scene, an aesthetic power to the painting that unfolds but at the same time, it's the horror of war, the carnage, the blind death that befalls men. Between the aesthetic value of the sublime painting and its radical negation by the horror of war, the protagonist is gripped, trapped, crushed : he understands nothing, he bears the nonsense of the event.

We find here, in slightly modified form, the three elements we identified in the previous course as constitutive of the tale : imaginative fantasy crystallizes here as an aesthetic façade and will constitute the façade of the wit ; the vain rationality of metaphysical discourse is transposed into the sequence of the historical narrative and the ordering of the event, with the same questioning of causality ; this questioning establishes the relationship, the relation that binds, that knots the mot d'esprit ; the background of reality always constitutes the background, or the tendency of the narrative, " of what is indeed in it ". The device of heroic butchery thus orders these three elements as façade, relation and tendency. The spirit implements the device of the tale it is in fact the same /// dispositif :

" Nothing was so beautiful, so lithe, so brilliant, so well-ordered as the two armies. Trumpets, fifes, oboes, drums, cannons, formed a harmony such as never was in hell. First, the cannons toppled some six thousand men on each side; then the musketry removed from the best of all worlds some nine to ten thousand rascals who were infecting its surface. The bayonet was also sufficient reason for the death of a few thousand men. The whole might well have amounted to thirty thousand souls..." (p. 43)

" ...the two armies " : for the opening of this chapter, Voltaire adopts an overhanging, external point of view. The battle is not seen from one side rather than the other; it's a kind of aerial view showing the two troops advancing towards each other. The use of the imperfect tense in the first two sentences confirms that we're dealing with a description, before switching to narration with the past simple tense in the third sentence.

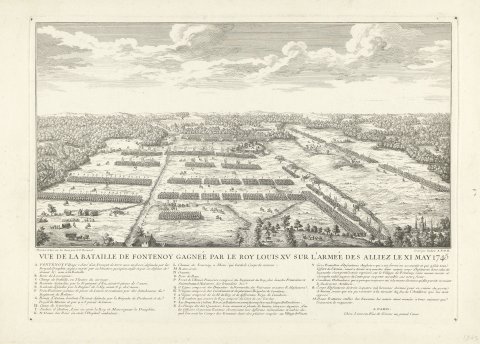

This point of view of the map constitutes the topical clutch of a battle narrative in classical historiography. We need look no further than Voltaire's own practice. Voltaire, appointed historiographer to the king in 1746, had undertaken to write the Histoire de la guerre de mil sept cent quarante et un7, which we now call the War of the Austrian Succession, of which the Battle of Fontenoy in 1743 is one of the most significant events.

It is to this war and not to the Seven Years' War (1756-1763) that chapter III of Candide alludes. The two main powers at war at the start of the War of the Austrian Succession were Maria Theresa's Austria and Frederick II's Prussia, which set out to take Silesia, south of Poland, from her. The peoples contested by the belligerent powers were therefore Slavs, and this may have suggested to Voltaire the name of the Bulgars. In the eighteenth century, Bulgarians were associated with the barbaric Scythians and confused with a heretical sect, the Bogomils, who were identified with the Manicheans, from whom the word Bulgarian is derived. These heretics are accused of being sodomites :

" Their detestable crimes further caused their name to become an odious one, a name of debauchery, so that Bulgare, or as found in some Authors Bugare, means a Sodomite, a Ctenobatte8, & a usurer, because they indulged in all these vices. In spite of all this the Protestans recognize the Bulgarians for their fathers, & have no shame in proving before them the pretended succession of their Church. " (Dictionnaire de Trévoux, 1738-1742, p. 1282)

There were rumors of the homosexuality of Frederick II, with whom Voltaire fell out in 1753. The King of the Bulgars, then, is this sodomite Frederick II, who pretends to seize the Scythian barbarians of Silesia. Faced with the Bulgars, Voltaire imagines Abares, based on a Scythian people, the Άβαροι, attested to by Isidore of Seville and Paul Diacre. Abares and Bulgars are therefore two subcategories, or variants, of the Scythians; they are barbarians who wage war against each other.

If the king of the Bulgarians is Frederick II, the kingdom that speaks the same language as Prussia, belongs to the same people, and yet is then at war with them, is the Austrians9. The Abares and the Bulgars are the Austrians and the Prussians, at war over a Silesia that we French have no use for. This is the war we're talking about. This war can be broken down into two phases: the first is the confrontation between Prussia and Silesia, which quickly concludes with Frederick II's victory at the Battle of Mollwitz on April 10, 1741. Voltaire was directly involved in this victory, which could constitute the original wound constitutive of the narrative of Candide10. Frederick concludes a separate peace with Austria, but their respective allies remain at war. The main belligerent powers became France and England. In this second phase of the war, the decisive battle is that of Fontenoy, on May 11, 1745: it is a French victory, but a Pyrrhic one; the French will gain no advantage.

The Heroic Butchery is a parodic condensation of these two battles, that of Mollwitz, a battle between Scythians a long way from France, which can be viewed with detachment and laughed at and that of Fontenoy, north of Lille, which was to become the emblem of what would become known a century later as the wars of lace11. Voltaire gave a detailed account of Fontenoy in chapter XV of Siècle de Louis XV. He begins thus :

" Looking at the maps, which are quite common, you can see at a glance the disposition of the two armies. We notice Antoing quite close to the Scheldt, on the right of the French army, nine hundred toises from this bridge of Calonne, by which the king and the dauphin had advanced ; the village of Fontenoy beyond Antoing, almost on the same line a narrow space four hundred and fifty toises wide between Fontenoy and a small wood called le bois de Barri. This wood, these villages were garrisoned with cannons, like an entrenched camp. Marshal de Saxe had established redoubts between Antoing and Fontenoy other redoubts at the ends of the Bois de Barri fortified this enclosure. The battlefield was no more than five hundred toises long from the place where the king was, near Fontenoy, to this wood of Barri, and was scarcely more than nine hundred toises wide ; so that we were going to fight in an enclosed field, as at Dettingen, but on a more memorable day. " (p. 149)

The starting point of a battle narrative is a device. Armies are laid out on a map. A configuration of places, a site, determines one, strategies, and from them, depending on the circumstances, the actions to come. There is a logic to the battle, a chain of cause and effect, whose rationality will be highlighted by the historiographic narrative. Nothing is more unreal, nothing more rational than a battle narrative. This is what Voltaire sets out to deconstruct in La boucherie héroïque, not as one would satirize another kind of narrative, another writing practice, but from his own practice.

II. " Rien n'était si beau, si leste, si brillant, si bien ordonné " : la façade de l'esprit

The introductory view with which chapter III begins is dazzling. Voltaire uses an adjective that deserves our attention. The ensemble he describes to us was leste. This adjective is used /// first and foremost that in a military context :

Léste. Adj m. & f. Who is brave, in good condition & in good crew to appear. Alacris, expeditus, succinctus, promptus. Une armée fort léste ; de l'Infanterie bien léste, bien vétuë & gaillarde. De la cavalerie bien léste, i.e., well mounted. Fêtes, carrousels, balls require people to be well léstes, pimpans & magnifiques. " (Dictionnaire de Trévoux, 1738-1742, p. 635)

Leste has nothing to do with elegance in the worldly sense. It's the dapper uniforms, it's the glitter of regiments parading for show, it's the gleaming facade of war. The whole beginning is orchestrated by Voltaire as a parade : visual parade first, aural parade second.

But right from the start this brilliance is undermined. First, there's the negative turn of phrase in the first sentence. Rien n'était si beau, it's a double negation, it's the double negation proper to the tale (it's not true that this is not a tale). In the end, this means that everything was beautiful, but what bursts out at the head of the chapter is nothing, it's this nothing that sounds like the kick-off to the heroic butchery : all this pomp, all this display of magnificence, it's all nonsense, it's worthless, it's nothing. Voltaire may well have coined this opening phrase from a letter from the Count of Saxony to d'Argenson, Minister of War during the War of the Austrian Succession, some ten years earlier. Several chapters of what was to become the Siècle de Louis XV were written at the time in Versailles at the home of Count d'Argenson, Minister of War : no doubt it was at this time and place that Voltaire read the letters from Count Maurice de Saxe (whom Voltaire always refers to by his military title, Marshal de Saxe), who commanded the French troops, to his supervising minister, and found in them what would become ten years later the opening formula of the chapter on " boucherie héroïque " :

" J'ai l'honneur de vous envoyer, Monsieur, une Lettre que j'ai reçuûe de Mr le Comte Des-Alleurs, par laquelle vous pourrez voir que j'ai depuis plus de deux Mois 500. Tartars and nearly 1000. Chevaux à la solde du Roi cette Lettre contient un Décompte, qui vous fera voir les sommes employées.

Ie survenû quelque empêchement à leur Marche, causé par la Cour de Saxe, qui me fait grand tort je cherche à le redresser, ainsi que vous pourrez le voir par la Lettre que j'écris à Mr. d'Ostens, Lieutenant Colonel de ce Régiment.

Notre Retraite de la Baviere est cause, que les Répresentations de la Cour de Vienne ont trouvé tant de poids à Dresde, j'ai de quoi m'affliger de tout ceci ; because in addition to this affair ruining me, Mr d'Osten increases my regrets by writing to me that he chose these Tartars out of 15,000, that they are the Elite of the Horde de Lips, & that nothing is so brave, so brilliant, & so light ; but I must not speak to you of my displeasures. " (Lettre de Mr le Comte de Saxe à M. D'Argenson, au Camp de Heitern du 26 août 1743, in Campagne de M. le maréchal duc de Coigny en Allemagne l'an 1743, Amsterdam, Marc Michel Rey, 1761, p.189-190)

" Rien n'est si brave, si brillant, & si leste ", says the Count of the Cossack cavalrymen of the Horde de Lips he had recruited to form the elite of his troops and march with Saxony against Vienna. It's not a question of him raving about the aesthetic effect that handsome soldiers could produce, but of praising the military quality of his recruits, for which he intends to be reimbursed. These soldiers are brave and nimble, courageous /// and well equipped.

Voltaire changes " brave " into " beau " and thus inflects the meaning of " leste " : he aestheticizes a formula that was a recruiter's formula, valuing good recruitment. Finally, to the triad of adjectives he adds " well-ordered ", which orients the point of view : the view we are offered is not the view of men (as the first three adjectives might suggest), but the strategy of an ordering, the organization of a ballet timed on a staff chart. There is an order to this view, a logic of arrangement that presides over the battle: but this order, this logic, will never be given to us. This immediately reveals the device on the imaginary plane, it unfolds the dazzling façade of battle on the symbolic plane, it is ordered as the futile rationality of a strategy on the plane of reality, it confronts us with the horror of the massacre.

The non-superposition of these planes defines the technique of the mind. This non-overlay is evident from the very first sentence : " Nothing was... but the two armies. " Syntactically, " les deux armées " makes explicit the opening " rien ". Now, this " rien " designates a whole, or a heap, a single whole in any case, and the brilliance of this whole, whereas " les deux armées " implies a face-to-face confrontation in which it's difficult to grasp, in a single view, the two fronts confronting each other. The syntax of the second sentence again sets up a (non-)superposition: " une harmonie telle qu'il n'y eut jamais en enfer " identifies the harmony of the instruments of the military parade with the din of Hell, the symphony with a cacophony. This reversal was prepared by the addition of an intruder to the enumeration of instruments, apparently putting them all on the same plane the last instrument is the cannons the lacy war parade, the joyful, well-ordered march gives way to war proper.

The spirit of the statement lies in this discordance : the aesthetic façade determines the tone and rhythm of the enunciation, light, joyful, perky. The paradigmatic accumulation requires no effort on the part of the reader to understand the complex syntax. The reader's attention is relaxed, and so the cannons slip, dare we say without a moment's hesitation, into the tail of the second enumeration. At the end of each sentence, however, the light-hearted verbiage is brought back to the harsh reality of war: " nothing was so beautiful... " / " ... the two armies " " the trumpets... " / " in hell ". " En enfer... " is said to the sound of the fife, the stinging horror of war slips as if from nothing into the gallant tone of salon conversation.

III. The sum and the count

With the switch to the simple past, the weapons that the cannons had introduced into the beautiful ordinance take syntactic command : the next three sentences, in the simple past, present themselves as an addition, of which the fourth is the total. The addition of weapons means a subtraction of men, the discordance rests first on this contradiction of movements :

| Canon | 2x600 | |

| + | Mouqueterie | 9 or /// 10000 |

| + | Bayonets | Some 1000 (apparently 4 or 5000) |

| = | The whole | ± 30000 |

In the same way that the description, presenting itself as a view, was in fact unfolding on the march, this sum, which seems like a tactical countdown, actually follows the course of the battle. First, from afar, the cannons fire the long-range cannonballs; then, from closer range, the rifles launch the medium-range shots, when the two armies are already very close to each other; finally, the rifles' bayonets only come into play in the hand-to-hand melee. So Voltaire is always playing on both the aesthetic, overhanging level (the sum of the weapons and their effects, the ordering of the battle) and the dynamic level of the actual unfolding of the battle (the advance of the men, the accumulation of the dead). Each of the terms of the addition follows the same syntactic logic as the first two sentences: first the brilliance of the deployment of weapons, then the reality of war, the countdown of the dead.

A syntactic mechanism is thus set up, based on this non-superposition of aesthetic overhang and macabre immersion. In the order of this mechanism (note the symmetry of " six thousand men on each side ", which extends the opening symmetry of " so well ordered that the two armies "), Voltaire introduces the disorder of sarcasm, as an indicator of the disturbing presence of the real.

This disorder initially goes almost unnoticed. After the cannons should come the guns. But Voltaire says " mousqueterie " instead of rifles. The word is all the more surprising as Trévoux's dictionary tells us of a subtle distinction :

" Mousqueterie, s. f. Art de bien manier le mousquèt. Ars catapultaria. This Master hears well the mousquetereie. It is also said of the salvos or discharges of musketeers which are done by honor, & without ball. But the discharges made against the enemy are called mousquetades. It is usage that has established this difference between mousqueterie & mousquetade. "

Strictly speaking, musketry does not refer to muskets as a whole, but to the act of using muskets. However, in this usage we distinguish between a -erie suffix and a -ade suffix, which don't have the same meaning. In battle, it's -ade that's in use a canonnade, a fusillade, a mousquetade. The suffix -erie refers to the parade, the theater of war, the " nothing was so beautiful, so lithe, so brilliant ". Now we're in battle why does Voltaire use the wrong word ? Because the word arrives, in the syntactic mechanics that order the passage, at the moment of aestheticizing flight, not of falling back into reality and death. This salvo of muskets is first seen as musketry, before being counted as a musketry. This word musketry is already the word he uses in Le Siècle de Louis XV for the battle of Fontenoy :

" The officers of the French guards then said to each other : We must go and take the cannon from the English. They quickly went up with the grenadiers, but were astonished to find an army in front of them. The artillery and musketry knocked nearly sixty of them to the ground, and the rest were forced back into their ranks. " (p. 153)

Mousqueterie is heroic vocabulary. Voltaire is also sensitive /// to the noise of language : " l'artillerie et la mousqueterie " form the almost Cratylian signifier of the rolling fire of weapons unloaded on the enemy ; it's a fanfare, it's the ringing brilliance of heroic battle. The same word thus sounds both, in the Siècle de Louis XV, as the heroic vocabulary of the grand genre, of the French epic of Fontenoy, and, in Candide, as a witticism ridiculing the already aged, already unfashionable parade of an operetta army. It should be noted that muskets, the ancestors of rifles invented in the 16th century, were no longer in use when Voltaire wrote. The article Mousquet in the Encyclopédie (1765) tells us that " on s'est servi de mousquets dans les troupes jusqu'en 1604 ; mais peu de tems après cette année on leur substitua le fusil. " In fact, muskets remained in French armies until around 1700 but in the 18th century, they became a museum weapon, evoking the prehistory of modern warfare. A museum weapon : an aesthetic object. You have to read this word mousqueterie with a little ironic pout, it doesn't look like anything, it's pretty, it's a bit old-fashioned, and pan nine to ten thousand men killed !

These are no longer men, by the way, but " rascals who infected the surface " of the earth : the tone becomes cynical, and above all the order of the addition becomes increasingly disturbed. The aim is to make the unreasonableness of this reason for the sum felt, by introducing affect into the cold calculation. On the other hand, there is a higher logic to this slaughter, suggested by the introduction of Leibnizian vocabulary: "brave new world" and "sufficient reason" refer to La Théodicée and imply that Providence is at work in the slaughter we are told about, that this slaughter has a reason, that these dead die for the best. " Coquins " is therefore not just a vocabulary inflection for " hommes ", it's a cause : nine to ten thousand men are killed in the artillery salvo because they're coquins. In the same logical order, the sum of the dead is not established in men but in souls : at this point, at the moment of the sum, the men are dead, only souls remain to be counted.

The logical order has shifted : from the order of armies, the order and sequence of battle, Voltaire slides to a more abstract order, which is the order of the providential finality of events. The vain rationality of the symbolic plane shifts, from the aesthetic to the metaphysical, while the plane of reality is revealed : death is first suggested by periphrase : " renversèrent " suggests simple pawns overturned on a map " ôta du meilleur des mondes " formulates an abstract subtraction it's only at the moment of the melee, when we disembowel each other with bayonets, that death is explicitly signified. This corresponds to the actual experience of Enlightenment warfare death is at first almost abstract at the start of the battle, when the soldier advances and his comrades fall around him under the seemingly totally random effect of enemy artillery it's only at the moment of hand-to-hand combat that it takes on a face, and you have to kill to avoid being killed yourself. Voltaire does, however, give figures that indicate a proportion: a few thousand deaths by bayonet, for 30,000 deaths in total, i.e. a little over 15%: in modern warfare, melee becomes a marginal cause of death; mass death, the one that centrally characterizes the reality of battle, is an impersonal death, governed by chance. The soldier advances in a /// field with a certain proportion of chances of being killed. Such is the precise reality that the critique of Leibnizian theodicy aims at in Candide : not in itself the dogmatic content of a providentialist theological discourse (always reduced by Voltaire to galimatias) but the erasure of meaning in reality, the triumph of randomness, the absurd and mute horror of blind death.

IV. The aesthetic regime of the mind

So, in the device of the mind, there is on the one hand the aesthetic plane of the ordered view, of the brilliance of uniforms, of the staff map, of the declination of weapons, and on the other hand the real plane of the dead who fall at random, of the battle that is fought even before the battle, no one knowing for what cause or for what gain. Between these two planes, and holding them together in their unlikely coupling, the narrative unfolds the succession of events.

This succession constitutes the march of the battle. Here, it virtually fades into the background, whereas it is the essential, ultra-visible spring of the historiographical narrative. Compare this with the Voltairian account of Fontenoy:

" the English and Hanoverians advance with him [= the Duke of Cumberland] without almost disturbing their ranks, dragging their cannons by the paths : he formed them into three fairly tight lines, each four meters high, advancing between the cannon batteries that struck them down in a field about four hundred toises wide. Entire ranks fell dead to the right and left; they were immediately replaced; and the cannons they brought up to arms opposite Fontenoy and in front of the redoubts responded to the French artillery. In this state, they marched proudly, preceded by six artillery pieces, and with six more in the middle of their lines " (p. 152-153)

What gives the battle its rationality in the narrative is its march, towards victory or defeat. The cannons are transported on carts of sorts, moving with the advancing troops. For Fontenoy, Voltaire insists on the effort of movement, and on the heroic gesture of men engaged in a march that costs physically in heroic butchery, the cannons seem immobile, there is no effort the narrative fades, the picture becomes an abstract sum. It is the very heroic substance that is sucked out.

There is much more here than a technique of the mind : in the seizure of war as sight and as randomness the same shift is played out, which is the shift from a poetic regime of representation, with its rules and hierarchies, to an aesthetic regime, centered on potentiality and singularity of any kind. In the poetic regime, the narrative articulates one or more heroes to an event that makes sense within a genre (the epic of a war, or its historical chronicle) in the aesthetic regime, the form of the narrative, the figure of the hero, the consistency of the event are deconstructed. In each case, it is the (non-)superimposition of the planes of the spiritual narrative device that brings about this deconstruction : the event is reduced to the oxymoron of a heroic butchery, where butchery says what is real and heroic ironically recalls what the symbolic should be there are no heroes, but numbers on the battlefield, men, then rascals, then souls there is no narrative, but the description of a view, of an order of battle, and it is this description that carries the rubble of the narrative of the event. The categories that emerge with the establishment of this new aesthetic regime of representation are potentiality and singularity of any kind.

Potentiality first it is paradoxically carried by theodicy /// Leibnizian philosophy that the recite brocades. We live in the best of all possible worlds, so we could live in an infinite number of other worlds: what the heroic butchery expresses, overturning Leibniz, and what the rest of the story will suggest, is that any other world would be preferable. There are therefore two ways of looking at potentiality, either positively, as the election by reality of the best of all possible worlds, or negatively, as a revolt against reality and the opening up by fiction of all its possible alternatives12. This opening, which presents itself as a critique of Leibniz, is only possible from the theoretical model created by the Theodicy. Potentiality denies Leibniz on the basis of Leibniz. This is manifested in the story's resurrection of Pangloss at the end of the chapter : killed by war, Leibnizian discourse returns from the dead : " The ghost stared at him, shed tears and jumped at his neck. " After the worst catastrophe that brutally and horribly belies it, Leibnizian discourse always returns like a ghost, like a... spirit13. For it gives shape to the new representation of the world that denies him : a world of radical symbolic negation on which the wildest hopes and chimeras a reality at once absolutely null and fully potential, opening up to all possible worlds.

The heroic reality of the world Voltaire deconstructs here is not, however, an abstract reality. The battle he evokes is not a theoretical one, even if it doesn't exactly represent any actual battle. But Voltaire shifts the emphasis from the reality of the moment, from the battle itself, to its consequences, its aftermath. To see this, we need only continue our comparison with the account of Fontenoy in Le Siècle de Louis XV. Voltaire concluded it thus :

" This action decided the fate of the war, prepared the conquest of the Netherlands, and served as a counterweight to all the unfortunate events. What makes this battle forever memorable is that it was won when the weakened and almost expiring general14 could no longer act. Marshal de Saxe had made the disposition, and the French officers won the victory. " (p. 167)

The battle is an " action " ; because this action is prepared by a " disposition ", it determines a meaning and makes an event. Heroic butchery" systematically contradicts this: there's no genius in disposition, which is pure window-dressing. There's no action, because the only character who stands out as a singularity is Candide. Lastly, there is no event, because there is no victory, no path towards a way out of the war, or even towards a decisive turning point : from the butchery of the battlefield, we pass without transition to the two Te deum, which cancel each other out in a way : there is no victory if both sides attribute it to each other. In Fontenoy's account, victory is a theatrical scene, of the grand kind, where the narrative takes care to preserve the dignity even of the vanquished :

" The English rallied, but they yielded they left the battlefield without tumult, without confusion, and were vanquished with honor.

The King of France went from regiment to regiment cries of victory and long live the King, hats in the air, standards and flags pierced by bullets, the mutual congratulations of officers embracing each other, formed a spectacle that everyone enjoyed with tumultuous joy. " (p. 164-165)

In place of this spectacle, this heroic scene of storytelling, the narrative of Candide substitutes the journey behind the scenes of the event, into the offstage of the battle's sides, into the reality of looting, civilian massacres, rape and torture.

" Candide, who trembled like a philosopher, hid as best he could during this heroic butchery.

Finally, while the two kings were having Te Deum15 sung, each in his camp, he took it upon himself to go reason elsewhere about effects and causes. He passed over heaps of dead and dying, and first reached a nearby village it was in ashes it was an Abare village that the Bulgarians had burned, according to the laws of public law. Here, old men riddled with blows watched their slaughtered wives die, holding their children to their bloody teats there, girls, disembowelled after having satisfied the natural needs of a few heroes, breathed their last others, half-burned, cried out to be put to death. Brains were scattered on the ground next to severed arms and legs.

Candide fled as quickly as possible to another village it belonged to Bulgarians, and the Abar heroes had treated him the same way. Candide, still walking on throbbing limbs or through ruins, finally arrived outside the theater of war, carrying a few small provisions in his bissac, and never forgetting mademoiselle Cunégonde. "

After the brief parodic account of the battle, Candide is the first individual to appear. If he can be said to appear : his action is to hide. Candide is not part of the heroic scene of action, which is itself maintained in the neutralizing vagueness of butchery. Candide's singularity is parodically reduced to a generic category by comparison: Candide, " like a philosopher ". Voltaire may have been recalling the verses Frédéric had sent him after his victory at Mollwitz in Silesia, in May1741 :

In a word, from the center of trouble,

I seek you in the bosom of peace,

Where you know how to enjoy double

A hundred pleasures, a hundred successes ;

Where you live when I work ;

Where you instruct the universe,

When from a hundred diverse peoples

I see, at the height of battle,

The shadows pass to the underworld16.

Frédéric opposed two worlds, that of Prussian warfare and political action on the one hand, of which he presented himself as the center and master, and that of French refinement and spirit on the other, which is also that of philosophy, whose crown he obligingly granted to Voltaire. Voltaire, on the other hand, places Candide at the heart of the battle, not in the happy position of the philosopher of the pleasures of the mind, but in the terror of carnage. Candide " trembled like a philosopher " is at first understood ironically : the philosopher is not the valiant hoplite of the battles of Potidea, Delion and Amphipolis that Socrates was ; the philosopher is that vain talker whom Frédéric describes under the guise of flattery and whom Voltaire caricatures as Pangloss, a man of words and ideas quite incapable of facing the reality of the enemy in battle.

But, as is often the case with irony, " like a philosopher " can also be understood without irony : as a good philosopher attentive to causes and consequences, Candide is in no way deluded by the gleaming apparatus of armies on parade. He trembles as the soldiers run blindly to their deaths, because he is aware of the /// danger and butchery.

V. The line of any singularity

In the devastated space of war, Candide's journey traces a line that is the line of singularity : from the butchery of battle to the first massacred Abare village, from there to the Bulgarian village that has suffered the same fate, and from there finally to the Dutch border. Candide is reduced to this line. Voltaire tells us what he sees, never what he feels. Instead, he constructs a parody of his interiority. Does he have to decide to act? " he took it upon himself to reason elsewhere about effects and causes. " In other words to take a hike. Is it to express what he feels ? He goes through the horrors " carrying a few small provisions in his bissac, and never forgetting mademoiselle Cunégonde ". In other words he's packed his lunch and is still dreaming of his quiet little pink novel.

Candide is a " singularity of some kind ". Giorgio Agamben recently summoned this scholastic category, the quodlibet ens, to think through it the deconstruction of the post-modern subject and the new relationship that is forged, through it, to " the coming community17 ". Candide does not bring to the world the singularity of a point of view, nor of an action likely to change it. Candide does not take part in the event, is not a hero (or even an anti-hero, for that matter) set on a stage of history (with a capital H): he is not a figure in an event. Candide is a line that crosses a reality, a world.

Candide doesn't describe the horrors he goes through this description is taken over by an omniscient narrator. When a look emerges, when a cry is heard, it's not Candide's, but that of an old man in front of his slaughtered wife, of a burnt girl asking to die. It is reality that is watching, not a subject, an observer that the narrative would place face to face with it, or in its midst18.

For all that, the description is not objective : it is conditioned by Candide's crossing, by the line of his singularity. This line confers on the reality described the value of ultima realitas, which is the last state, the most actual, the most present, the most alive state of the very form of reality, of its atemporal and universal form. In other words, it's the general form, the topical category of the horrors of war ; but it's this form seen from the line of Candide's journey through the midst of this reality.

What does this journey bring to this reality ? It gives it ecceity. The eccentricity of a form is its individuation principle, it's what makes someone, anyone, in front of this form say, ecce, here it is, it's her, I recognize her. Candide attests that what is described to us and through which he passes is indeed the horror of war, the very example, individualized here in this precise episode in chapter III of Candide, of what the horror of war in general is.

To tell the truth, it's both the example and the general form. It's the example on the line of the journey, and it's the general form on its outskirts. In order to maintain this logical contradiction constitutive of any singularity, it is necessary to preserve the unthought of any Candide is neither exactly indifferent to the approaches he crosses, nor a party to what he cannot fail to see. But he takes no position the question of his position is not asked. He is therefore neither absolutely singular (occupying the singularity of a point of view) nor indifferent. He is quodlibet, whatever, or more precisely whatever we like him to be, delivered as a vacant place to the libidinal investment of the reader who through him, from his post, can come to enjoy the outskirts, can circumscribe a scene of the world through the interpretative value he will give to the line of the path likely to delimit it.

This is where the heroism of the mind comes in. Voltaire strategically places the term in his text. It is absent from the battle right up to its macabre conclusion: " cette boucherie héroïque ". The hero emerges in adjectival form, i.e. adjacent, not as the essence of a figure on the stage of war, but as an attribute, a quality of a non-spectacle, a common non-event. The hero shifts from essence to attribute, from stage to approach, from individual to common. And indeed it is in these monstrous approaches to the backstage of war that the hero manifests himself : the disemboweled girls have " satiated the natural needs of some heroes " " some heroes abares had treated the neighboring Bulgarian village the same ".

It's not enough to note here that the heroes are heroes only by antiphrase, and that Voltaire is satirizing the horrors of war. The heroes are displaced from the collapsed scene of the narrative to the outskirts of Candide's journey the heroes conquer in the narrative their denomination and, hence, their essence as heroes only after the battle. They summon from behind the scenes a category that the proscenium can only disappoint.

Voltaire makes wit about this word hero, and in so doing he implements the relationship, the conjunction he described in 1744 in the Lettre sur l'esprit : it's the author who appears when we'd like to see the hero. But the author appears pointing at the heroes, who are rapists and mass murderers. So the text satisfies the demand, which is the demand for the hero: you wanted novel heroes, Voltaire's wit deprives you of them, but he gives them to you all the same, not in the brilliance of history but in the sordidness of the outskirts of reality, he gives them to you by antiphrase, and he gives them to you heroically, by making an act of courage through his wit. In the new world governed by the aesthetic regime and ordered by arbitrary singularities, heroism has been virtualized on the stage of language, reviving the scholastic categories of quodlibet ens. The new heroism is the heroism of the spirit.

Notes

///

The Kehl edition is the first posthumous edition of the complete works, produced between 1785 and 1790 in 70 in-8° and 92 in-12° volumes, under the direction of Beaumarchais and Condorcet. This monumental edition, produced with great care, served as the model for all subsequent editions of the complete works until the end of the 19th century. Beaumarchais installed the printers in the fort of Kehl opposite Strasbourg, on the lands of the Margrave of Baden to escape censorship.

Voltaire, La Mérope française, avec quelques petites pièces de littérature, Paris, Prault, 1744. Bnf, 8-YTH-11676 and 11677 ; Z BEUCHOT-565 (1).

" Ah ! here I am at last at the fire ! he thought. I've seen fire!" he repeated to himself with satisfaction. Here I am, a real military man. At that moment, the escort was going belly-up, and our hero realized that it was cannonballs that were making the earth fly in all directions. No matter how hard he looked, he could see the white smoke of the battery at an enormous distance, and in the midst of the even, continuous hum of the cannon shots, he seemed to hear discharges much closer by he couldn't make any sense of it at all. " (Stendhal, La Chartreuse de Parme, I, 3, ed. H. Martineau, Garnier, 1961, p.. 43)

On the parallel of Tolstoy and Stendhal, see J. Rancière, " Le maître des surfaces ", in Aisthesis, Galilée, 2011, /// p. 195.

" Beautiful men, said Napoleon, looking at a slain Russian grenadier, who, his face sunken into the ground and his neck blackened, was lying on his stomach, one hand already stiffened, thrown away. [...] Here's a fine death ! he said, looking at Bolkonski. Prince André understood that these words were spoken by Napoleon and referred to him. He heard that the speaker was called Sire. But all this was as uninteresting to him as the buzzing of a fly; he paid them no attention and forgot them at once. [...] What happened next was like a nightmare, of which Prince Andrew remembered only shreds... " (Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace, Part III, chap. 19, trans. M. J.-W. Bienstock and P. Laurent, Marabout, s. d., t. I, p.314-315. Sentences in italics are in French in the text.)

" ... like for example that reflex he had to draw his saber when that gust went into his nose from behind the hedge : for a moment, I could see him with his arm raised, brandishing this useless and derisory weapon in the hereditary gesture of an equestrian statue that generations of swordsmen had probably passed down to him, an obscure silhouette in the backlight that colored him as if he and his horse had been cast together from a single material, a gray metal, the sun shimmering for a moment on the bare blade, then the whole thing - man, horse and saber - collapsing in one piece to one side like a lead rider starting to melt by the feet, bowing slowly at first, then faster and faster on his flank, disappearing with the saber still held at arm's length behind the carcass of that truck collapsed there, indecent as an animal - a full bitch dragging her belly along the ground... " (Claude Simon, La Route de s Flandres, Minuit, 1960, p. 12)

This Histoire by Voltaire had an eventful editorial destiny : the unfinished manuscript was stolen and published in spite of itself in 1755 and 1756 Voltaire incorporated part of it into his 1763 edition of Essai sur les mœurs, and finally completed his project, which he published under the title Précis du Siècle de Louis XVin 1768. This means that in the late 1750s, Voltaire had his account of the War of the Austrian Succession on the table, when he wrote Candide.

This word doesn't exist in French ! In Greek, κτηνοβάτης, who goes to the beasts, zoophile (Aristophanes).

We wanted to identify the king of the Abares with Louis XV. This identification is unfounded and unproductive. The King of the Abares is created by a verbal game based on " King of the Bulgars ", to say that it's a case of blanc bonnet et bonnet blanc. It's certainly not what Voltaire would say about Louis XV and Frédéric II.

Frédéric writes to Voltaire to announce his victory. Voltaire reads his letter to the audience during a performance of Mahomet in Lille. But he disapproves of the annexation of Silesia and, more generally, hates war. He hopes that the old Fleury, who is then Louis XV's prime minister, will make peace with Maria Theresa of Austria, to whom he addresses an ode to this effect. The ode is published, causing a scandal. Voltaire congratulates Frédéric on his separate peace. In June 1742, he wrote to him: " half the world cries out that you are abandoning our people to the discretion of the god of armies the other half cries out too, and doesn't know what it's all about. A few abbots of Saint-Pierre bless you in the midst of the shouting. I'm one of those philosophers, I believe you'll force all the powers to make peace, and that the hero of the century will be the peacemaker of Germany and Europe. I think you've beaten the good old man to the punch." (Jean Sareil, Voltaire et les grands, /// p. 45) Voltaire first refers to Frederick's separate peace, abandoning France, which had nevertheless come to his aid ; the Abbé de Saint-Pierre was the author of a Projet de paix perpétuelle (1713) based on the political construction of a federal Europe ; the good old man is Fleury.

The emblem of this lacy war is a famous anecdote reported by Voltaire at the start of the battle : " The English officers saluted the French by taking off their hats. The Comte de Chabanes, the Duc de Biron, who had come forward, and all the officers of the French Guards returned the salute. Milord Charles Hay, captain of the English guards, shouted: "Messieurs des gardes françaises, tirez."

Le comte de Hauteroche, then lieutenant of the grenadiers, and since captain, told them in a loud voice: "Messieurs, we never shoot first shoot yourselves." The English made a rolling fire, that is, they fired in divisions ; so that, the front of one battalion on four men's height having fired, another battalion made its discharge, and then a third, while the first reloaded. The French infantry line did not fire in this way: it was alone on four high, its ranks quite far apart, and not supported by any infantry troops. Nineteen Guards officers were wounded in this single charge. Messieurs de Clisson, de Langei, de Peire, lost their lives ninety-five soldiers remained in the square two hundred and eighty-five received wounds eleven Swiss officers fell wounded, as did two hundred and nine of their soldiers, of whom sixty-four were killed. " (p. 154-155)

See, for example, Candide's exclamation at the end of chapter VI : " If this is the best of all possible worlds, what are the others ? " (p. 54) Or in chapter X, as they set sail for the Americas : " We're going to another universe, said Candide it's in this one, no doubt, that everything is good. [...] It is certainly the new world that is the best of all possible universes. " (p. 63)

In the first section of the article Esprit in Questions sur l'Encyclopédie, Part V, we read :" What we commonly understand in French by esprit, bel esprit, trait d'esprit, etc..., means ingenious thoughts. No other nation has made such use of the word spiritus. The Latins said ingenium ; the Greeks, εὐφυΐα, or else they used adjectives. The Spanish say agudo, agudeza. " And a few lines further on : " Manes, umbræ, simulacra, are the expressions of Cicero and Virgil. The Germans say geist, the English ghost, the Spanish duende, trasgo ; the Italians seem to have no term meaning revenant. The French alone have used the word esprit. The proper word, for all nations, must be fantom, imagination, reverie, silliness, knavery. "

Voltaire means here the Count of Saxony, who was the heroic strategist of this battle and took part in it in person and at the front, when he was already dying.

At the end of the Battle of Dettingen (June 27, 1743), where the English led by their King George II defeated the French commanded by Marshal de Noailles, Handel composed the Te Deum of Dettingen, HWV283.

Letter from Frederick to Voltaire, from the camp at Mollwitz, May 2, 1741.

Giorgio Agamben, The Coming Community. Théorie de la singularité quelconque, trans. Marilène Raiola, Seuil, 1990. See especially Chapter V, Principium individuationis.

Contrast this description of behind-the-scenes battles with Voltaire's account of the care of the wounded after the battle of Fontenoy, a model of organization and humanity, and also a model of community: "Never since war has there been more care taken to relieve the evils associated with this scourge. Hospitals were set up in all the neighboring towns, and especially in Lille; even the churches were used for this worthy purpose; not only was there no help, but no comfort was lacking, either for the French or for their wounded prisoners. The zeal of the citizens even went too far delicate food was constantly brought to the sick on all sides and the hospital doctors were obliged to put a stop to this dangerous excess of good will. Finally, the hospitals were so well served, that almost all the officers preferred to be treated there than in private homes ; and this was something we had not yet seen. " (p. 166-167)

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « L'héroïsme de l'esprit », Voltaire, l'esprit des contes, cours d'agrégation donné à l'université d'Aix-Marseille, 2019-2020

Voltaire

Archive mise à jour depuis 2008

Voltaire

L'esprit des contes

Voltaire, l'esprit des contes

Le conte et le roman

L'héroïsme de l'esprit

Le mot et l'événement

Différence et globalisation

Le Dictionnaire philosophique

Introduction au Dictionnaire philosophique

Voltaire et les Juifs

L'anecdote voltairienne

L'ironie voltairienne

Dialogue et dialogisme dans le Dictionnaire philosophique

Les choses contre les mots

Le cannibalisme idéologique de Voltaire dans le Dictionnaire philosophique

La violence et la loi