The Dictionnaire philosophique is not a literary work like any other. Its very literarity poses a problem, not only because it presents itself as a dictionary, and not as a followed text, but also and above all because it is part of an action, a commitment, in the real world therefore, far from any fiction.

The encyclopedic adventure

The 1750s saw dazzling successes in the philosophers camp: after the publication of L'Esprit des lois by Montesquieu in 1748, the first volumes of L'Encyclopédie by Diderot and D'Alembert came out at a rate of 1 per year from 1751 to 1757. But everything changed after Damiens' attempt on Louis XV's life in 1757. D'Alembert's article on Geneva in Volume VII of the Encyclopédie, written after a visit to Voltaire's home in the summer of 1756, set things alight: clumsily distributing praise and blame in Geneva, D'Alembert provoked an indignant reaction from both the Sorbonne and the Swiss. Diderot stood firm, but Voltaire took fright. In early 1759, Parliament suspended the sale and distribution of the Encyclopédie ; a few months later, in March, the Conseil d'État forbade publishers to continue publication and revoked the king's privilege, i.e. the official authorization that guaranteed and protected publishing. On the same date, give or take a few days, the Pope placed the Encyclopédie on the index.

Palissot's provocation

In 1760, the Comédie française performed a violent satire aimed personally at Diderot : it was Charles Palissot's Les Philosophes, which was a smashing success as a scandal. The artisans of the Enlightenment are portrayed as a gang of corrupt demagogues : Crispin, the anti-philosopher valet, does a memorable pantomime in one scene, mocking the Citizen of Geneva, Rousseau, whom he apes by crawling on all fours before his admiring masters. Philosophers congratulate him on this representation of the state of nature, and misinterpret Crispin's satire as a genuine act of philosophy.

Palissot sends his play to Voltaire in Ferney. But Voltaire declares his solidarity with Diderot and his friends : " I regard the Encyclopedists as my masters1 ". In July, he writes to Mme d'Epinay :

" I know better than anyone what is going on in Paris and Versailles, about philosophers : if we divide ourselves, if we have little weaknesses, we are lost. The infamous and the infamous will triumph. Would philosophers be so stupid as to fall into the trap set for them? Be the link that must unite these poor persecuted2. "

Voltaire however, despite D'Alembert's pressing requests, does not respond publicly to Palissot's public insult : " The only reasonable party in a ridiculous century, is to laugh at everything "3.

I. Voltaire s'engage : Rochette, Calas, Sirven

Then erupt one after another three scandalous court cases, in which Protestants, banned by law since the revocation of the Edict of Nantes by Louis XIV in 1685 confirmed by Louis XV's Declaration in 1724, are the victims of shameful partiality. /// The Calas affair began with Pastor Rochette, arrested north of Montauban in September 1761; his son Calas was found dead in Toulouse in October 1761; Sirven, on the run after the death of his daughter, was arrested in Mazamet in January 1762. Voltaire's abundant correspondence suggests that the first articles of the Dictionnaire philosophique were written around this time (1759-1761), although the first edition was not printed in Geneva until 1764.

" ...all for singing David's songs... "

But here again Voltaire is reluctant to get involved. He intervened only half-heartedly in the Rochette pastor affair. Rochette had been arrested north of Montauban on suspicion of theft. He then declared himself a minister of the Reformed religion, exposing himself to death under the Declaration of 1724. The next day, on market day in Caussade, where he had been incarcerated, a riot broke out: Protestant peasants clashed with Catholic townsfolk. Three Protestant glassmakers attempt to free Rochette. Arrested and brought with Rochette before the Toulouse Parliament, they were condemned to death: in February 1762, Rochette was hanged and the gentlemen beheaded. Voltaire, warned by a young Protestant merchant from Montauban, did indeed intervene with the Duke of Richelieu, to request a pardon for the condemned men. On March 2, he concludes a letter to the d'Argental devoted to his latest literary productions with these words :

" Nor do you tell me anything about the Burgundy parliament, which has also decided to cease dispensing justice to spite the king, who, no doubt, is greatly distressed that my trials are not being tried. The world is quite mad, my dear angels. It has just condemned a minister of my friends to be hanged, three gentlemen to be beheaded and five or six burghers to the galleys, all for singing David's songs. This parliament of Toulouse doesn't like bad verse.

I kiss your wings with compunction4. "

The rebellion of Dijon's parliamentarians annoys Voltaire, who has some business there on trial5. From the parliament of Burgundy, he moves by association to the parliament of Toulouse : the folly of the Toulousans, who condemned Rochette and his friends, is worth that of the Burgundians, and more precisely of President de Brosses, with whom Voltaire is mired in a sordid tenant's quarrel.

But there's more : the tragedy of Pastor Rochette, who died heroically for his faith when arrested as a thief he could have avoided death, is not to Voltaire's taste. The assemblies of the Désert, where Protestants sing David's psalms, are for him assemblies of fanatics he ridicules them not from a religious point of view, but from an aesthetic one they are " bad verses ". Unlike Catholics, whose liturgy is always in Latin, Protestants in fact sing the psalms in the French translation by Clément Marot and Théodore de Bèze (1561), or in its revision by Valentin Conrart (died 1675).

It's clearly not for the incorrectness of an aged French, which doesn't meet the standards of classical elegance of language, that Rochette and his friends were condemned. Voltaire transposes the horror of real injustice into the madness, the nonsense of an aesthetic judgment in the face of a spectacle.

The dramatization of reality, its aesthetic distancing, nevertheless produces a seesaw effect : denigrated, parodied, Rochette's tragedy seems to us today scandalously denied and depreciated ; but it is precisely this parodic depreciation that allows it to enter Voltairean discourse. From the buffoonery of a failed show, /// the horror of reality returns, reaches its addressee the d'Argentals are angels and the Toulouse parliamentarians, crusty journalists, the kind Diderot sketched in Le Neveu de Rameau. The angelic point of view6, religious therefore, triumphs in extremis thanks to a witticism.

The Calas Affair

One affair chases another. The Calas affair erupts immediately after the Rochette pastor affair. Marc Antoine Calas, son of a Toulouse cloth merchant, was found dead in his father's home on the evening of October 13, 1761: was he murdered in the back room for an obscure gambling debt, as the family initially claimed, as they finished dinner upstairs. Or did he commit suicide, as they later claimed? For the Toulouse justice system, this contradiction proves the guilt of Father Calas there's no doubt that Marc Antoine wanted to convert to Catholicism, and that his family executed him, preferring him dead rather than converted ! The streets of Toulouse burst into flames against the Calas family, and Marc Antoine was buried in Saint-Étienne Cathedral, with great Catholic pomp. After much prevarication, since there was no material evidence against him, the Toulouse parliament condemned Jean Calas to the ordeal of the wheel: he was executed in March 1762. To the end, and even under torture, he proclaimed his innocence.

Voltaire at first doesn't believe in this innocence : " We're not worth much, but the Huguenots are worse than us ", he writes to Le Bault on March 22. However, indignation shakes Geneva, next door to his home. Information and details were accumulating. On the 25th, Voltaire hesitated. On the 27th, he writes to the d'Argental :

" You may ask me, my divine angels, why I take such an interest in this Calas who has been roué ; it's because I'm a man, it's because I see all the foreigners indignant, it's because all your Protestant Swiss officers say they won't fight heartily for a nation that has their brothers roué without any proof.

I was wrong about the number of judges. There were thirteen, five consistently declared Calas innocent. Had he had one more vote in his favor, he was absolved. What is the value of human life? What is the point of the most horrible tortures ? What ! because a sixth reasonable judge could not be found, a father of a family7 will have been put to death7 ! he will have been accused of hanging his own son, while his four other children cry out that he was the best of fathers ! Doesn't the testimony of this unfortunate man's conscience take precedence over the delusions of eight judges inspired by a brotherhood of white penitents who stirred up the spirits of Toulouse against a Calvinist? This poor man cried out on the wheel that he was innocent he forgave his judges, he wept for his son to whom it was claimed he had given death8... "

It was Voltaire who gave this miscarriage of justice, which could so easily have been forgotten, a public and European resonance. Europe looks to Toulouse, and France. Public judgment stands up to institutional judgment. With the Calas affair, Voltaire ushers French society into a form of political modernity.

The springboard for mobilizing opinion is the image, and it's the device. The image first " je vois tous les étrangers indignés ", Voltaire tells us. Faced with these staring faces, these Swiss from Versailles (" vos officiers suisses protestants ") who, mute at the service, carry the indignation behind their impassive faces, stands the image of Calas roué, Christ-like icon of the supplicant. /// forgiving his tormentors. But the image is not only verbal in this case. In 1765, following the retrial, Carmontelle, at Damilaville's request, executed a print9 depicting the widow Calas in a black dress seated between her two daughters and her faithful Catholic servant, Jeanne Viguière, in front of her son Pierre and Gaubert Lavaysse, the family friend, reading the sentence of rehabilitation. The sale was a huge success. Voltaire enthusiastically buys twelve and places one above his bed10. The discovery of the body of Marc Antoine Calas, Calas roué place Saint-Georges (engraving by Dodd), Calas' farewell to his family will also be engraved; Chodowiecki will even depict, in a satyrical way, The Effects of the sensitivity on the four different temperaments, in the form of four individuals observing this Farewell scene set on an easel.

The image is therefore only effective when taken as part of a device : Voltaire's entire successful campaign to overturn the Toulouse judgment, revise the trial of Jean Calas and rehabilitate his memory, involves the use of a network of active correspondents, who are not only linked by shared ideas and values. Solidarity of spirit is achieved through the shared experience of extraordinary verbal pleasure: bon mots, witticisms and depictions of the buffoonish absurdity of the world and its institutions coexist with horrific and moving depictions of the horrors of fanatical barbarism. It's reality, in all its tragic horror, and at the same time it's theater, with all the artifices of stagecraft: Voltaire takes great care to stage the widow Calas's arrival in Paris, transforming the woman he first calls " une petite Huguenote imbécile11 " into a tragedy heroine whose role he wrote (this is the ostensible letter from Mme Calas to Gaubert Lavaysse) as well as he wrote, in his Oreste of 1750, reprised in 1760, the role of Électre for the Clairon.

The Voltairean device does not, however, fictionalize the real : Mme Calas conquers, thanks to Voltaire, the authenticity of a true and independent figure Mlle Clairon, in the same way, had naturalized, as it were, the role the Ferney patriarch had written for her. At the end of a performance she had given at his home, the old man, bathed in tears and overcome with emotion, exclaimed: " It's not me who did it, it's her she created her role. "

Sirven, the other side of Calas

The story of the Sirven family is very similar to that of the Calas family, with a happier ending. At the outset, a Protestant family from the south-west of France, who, like the others, made a perfunctory conversion to Catholicism. In this case, it's the second of the three Sirven daughters, Elisabeth, who suffers from hysteria. In 1760, she ran away and asked the Bishop of Castres to make her a Catholic. The bishop placed her in a cloister to prepare for her conversion; her condition worsened; she was locked up, beaten and, after seven months, returned to her parents. Elisabeth Sirven's condition continued to deteriorate, as she obsessively demanded conversion and a Catholic marriage. In January 1762, she was found drowned at the bottom of the village well where the Sirvens, to escape public persecution of their family, had withdrawn.

.

Public opinion, the country doctor and surgeon in charge of the autopsy, and the judge immediately made the /// A comparison with the Calas affair, currently being investigated by the Toulouse parliament. A secret synod was held, perhaps in Lausanne, to decree Elisabeth's murder and thus prevent her conversion, just as Jean Calas prevented Marc Antoine's conversion by murdering him in Toulouse. Elisabeth's suicide or accident became murder against the evidence of the autopsy, and the Sirven family was ordered to take the body. Fortunately, they had time to escape, and thanks to the solidarity of the Protestants of Nîmes, they made it to Switzerland. In March 1764, the Sirvens were sentenced in absentia to be hanged. In September, their effigy was executed, in the form of a painting hanging from the gallows.

Voltaire learns of the case as early as February 1762, when the Sirvens are already on the run. But he doesn't want any interference with the Calas affair. He only met the Sirvens at the end of the latter in 176512. He would not obtain their rehabilitation until 1771.

The Calas affair directly and explicitly motivated the publication of the Traité sur la tolérance in 1763 : the full title, by the way, is Traité sur la tolérance à. the'occasion of the death of Jean Calas, and the first chapter is the " Histoire abrégée de la mort de Jean Calas ", even though from chapter III onwards the subject expands and to a very large extent prepares that of the Dictionnaire philosophique.

II. Genesis of the Dictionnaire philosophique

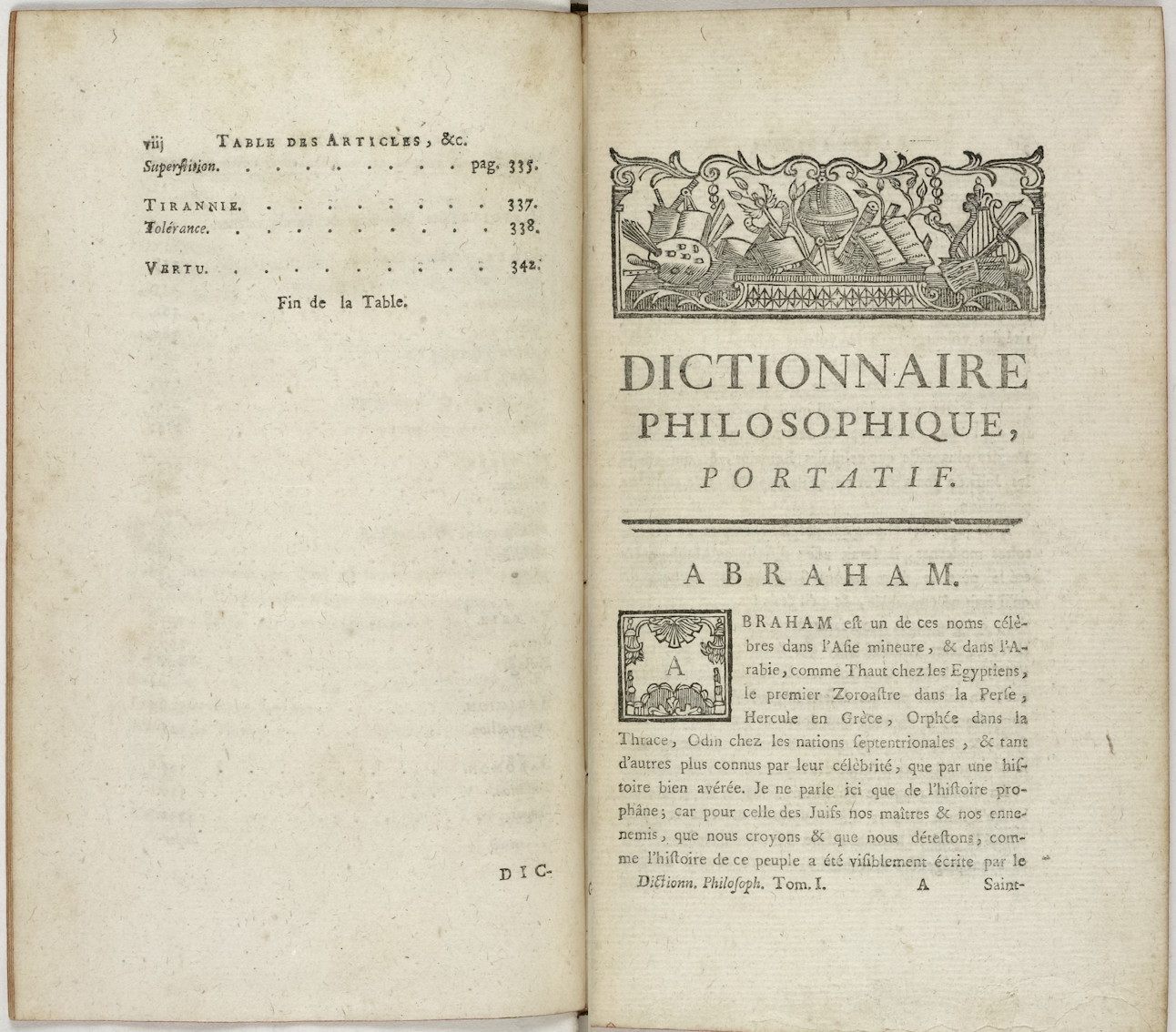

The Dictionnaire philosophique portatif (this was its first name, and it would take on others in successive editions) appeared much more detached : printed clandestinely by Grasset in Geneva in July 1764, i.e. between the condemnation and execution in effigy of the Sirvens, it was immediately energetically disowned by Voltaire. There's a kind of mimicry here with the second affair: Calas died publicly and heroically Le Traité sur la tolérance is a public speech, a J'accuse mobilizing all indignation, federating all the sympathies of the Enlightenment camp. Sirven, on the other hand, saved himself by fleeing Le Dictionnaire philosophique first stages the disappearance of its author, fragmenting and deconstructing the discourse, mobilizing the intimate springs of the mind, of conversation, the pleasant rambling of the otium, in private.

Mme du Deffand : the spirit of the Dictionary

Mme du Deffand is the great confidante of the Dictionnaire : it is to her, and her alone, that Voltaire, since 1759, entrusts, first allusively, then explicitly the project13. And Mme du Deffand was no activist: the Marquise was born in 1697, three years after Voltaire. Of poor nobility, but beautiful and intelligent, she devoted herself to libertinage in the boudoirs of the Regency. Her correspondence with Voltaire began in 1742. Since 1749, she had occupied the former apartments of the Marquise de Montespan in Paris. In 1753, she became blind, but this did not prevent her from holding a salon every day, and one of the most brilliant in Paris, especially on Mondays. Mme du Deffand was a jaded intelligence curious about everything, she feared boredom above all believing in nothing, she didn't approve of the Voltairian campaign against the infamous, and showed the greatest mistrust of enthusiasts like Diderot and the /// encyclopedists14 she laughed at Palissot's Philosophes and approved of his satire. But Voltaire's wit entertained her, she delighted in his writings, she was attuned to the denigrating detachment that the Voltairian pen knew how to take.

When Voltaire writes to her, he especially takes this turn of wit, always present in him, but here accentuated. Mme du Deffand, for Voltaire, is the touchstone of the effectiveness of what he writes outside the circle of the convinced, won over to his cause15. Writing persuades as long as it doesn't pretend to convince, and first provides the mind with the enjoyment of a firework display of points. On December 9, 1760, Voltaire sent him what may constitute the first two articles of the Dictionnaire philosophique16 :

" It's been over six weeks, madame, since I've been able to enjoy a moment of leisure ; this is ridiculous and no less true. As you don't like me writing to you simply for the sake of writing, I have the honor of sending you two little manuscripts that have fallen into my hands. One seems to me wonderfully philosophical and moral17 : it must, therefore, be to the taste of few. The other is a pleasant discovery I made in my friend Ezekiel. Ezekiel is not read enough. I recommend reading him while I can: he's an inimitable man. I don't expect these rogatons to amuse you as much as I do, but I would like them to amuse you for a quarter of an hour. [...]18 Take care, madam, try to have fun : the thing is not easy, but is not impossible.

A thousand respects from all my heart19. "

The letter opens with the desire to " enjoy a moment of leisure " and closes with the wish " to have pleasure ". The pleasure of the text is the envelope that carries its content, a priori much less engaging : it will be for the marquise to read moral philosophy on the one hand, a commentary on the book of Ezekiel on the other. Neither moralists nor theologians are very pleasant people. And therein lies the challenge: it is from the most ungrateful subjects, those furthest removed from the sphere of private pleasures, that the Voltairean pen will exert its overthrow. The Old Testament prophet is " inimitable " : the dull sublimity of his allegorical visions will provide fodder for laughter at the absurdity of sacred texts, which our society praises and reveres on condition that we don't read them.

.

Ezekiel's defense : abjection and revolt

The article Ezéchiel did not please Mme du Deffand. Voltaire was piqued and defended it in his letter of January 15 :

" You despise Ezekiel too much, madame the light manner in which you speak of this great man owes too much to the frivolity of your country. I'll pass on to you that you don't have lunch like him only Paparel20 ever had this honor reserved but you should know that Ézéchiel was more highly regarded in his day than Arnaud and Quesnel were in theirs. Know that he was the first to dare deny Moses that he dared to assert that God did not punish children for the iniquities of their fathers and that this caused a schism in the nation. Eh ! is it nothing, please, after having eaten shit, to promise the Jews, of the /// from God, that they will eat man's flesh all their drunkenness ?

Madame, don't you care to know the customs of the nations? If you had any curiosity, I would prove to you that there have been no peoples who have not commonly eaten little boys and girls and you will even admit to me that it is not such a great evil to eat two or three, as to slit the throats of thousands, as we politely do in Germany. "

Voltaire's falsely frivolous detachment to speak of the absurd horrors of fanaticism is effective, and acceptable, only if it arouses his reader's indignation through laughter, provoking his virtuous reaction. Let Mme du Deffand tire, show her blasé disinterest, and Voltaire mortifies her : Ezekiel is truly, seriously a great man Voltaire sees him as the one who first dared to revolt against the absurd and horrific prescriptions of Moses, refusing to let children pay for the crimes of their parents :

" in chapter XVIII, he says that the son will no longer bear the iniquity of his father, and that it will no longer be said "The fathers have eaten green grapes, and the children's teeth are set on edge21."

. In this, he expressly contradicted Moses, who, in chapter XXVIII of Numbers, assures that children bear the iniquity of the fathers to the third and fourth generation22. " (Dictionary philosophical, p. 186)

In the Bible, neither Ezekiel nor Moses say anything on their own : it's Yahweh's word that is proclaimed to Moses on Sinai, addressed to Ezekiel in his vision. To Moses, it is a question of manifesting God's power; to Ezekiel, of insisting on the personal responsibility of each Jew in Israel's turpitudes. Voltaire tinkers with the biblical material in order, faced with the despotic fanaticism of Moses, " the most barbaric of all men23 ", oppose a joker, a funny man, an inimitable Ezekiel, a jester of God indeed, who commands him to eat human excrement in jam, but a moderator of the excesses of the Judaic religion.

Ezéchiel is the financier Paparel, a rogue, a madman, a nephew of Rameau, but not a criminal. Ézéchiel is more important than Arnaud, the theoretician of Port-Royal, and Father Quesnel, the disciple of Jansen whose propositions were blacklisted by the Unigenitus bull. This implicitly identifies the leaders of the Jansenist party with the rigor of Moses. Moses, Arnaud and Quesnel on the one hand are the fanatics of the religious law ; Ezekiel and Paparel are its buffoons, whose absurd abjection is preferable to the terrorism of the fanatics.

This is not to enunciate a doctrine, and Voltaire does not claim, after Jansen's Augustinus and Les Réflexions morales du père Quesnel, to constitute a theological system. Receptive to any systematic radicalization, the discourse rears its head, and follows the sinuous reversals of its successive revolts : at the very time Ezekiel is defended against scorn, Voltaire fixes the figure as a coprophage. Ezekiel's jams in the Dictionnaire philosophique make people laugh, but revolt :

" As it is not customary to eat such jams on one's bread, most men find these commandments unworthy of the divine majesty. " (P. 185.)

God is said to have ordered Ezekiel, in penance, to spread his bread with human excrement. The prophet rebelled and his penance was softened : he would simply knead his bread with cow dung. Voltaire has been laughing about this ever since his Sermon. /// des cinquante, in 1752. Dom Calmet argues in his Commentary literal that the text should not be translated in this way. And indeed, the modern translation of the Jerusalem Bible has " You shall eat this food in the form of a barley cake that has been cooked over human excrement " (Ezekiel, 4, 12), then " Well ! I grant you ox dung instead of human excrement you shall bake your bread on it " (4, 15)24.

From eating shit, we then move on to eating children, and that old anti-Semitic accusation, that Jewish liturgy includes cannibalistic rituals. In Ezekiel, Voltaire is probably referring to the siege of Jerusalem and the imprecations against Gog, king of Magog. Indeed, after the account of Gog's burial and the victims of the war, the following verses :

.

" And you, son of man, thus says the Lord Yahweh. Say to the birds of every kind and to every wild beast : Gather yourselves together, come, gather from all around for the sacrifice I offer you, a great sacrifice on the mountains of Israel, and you shall eat flesh and drink blood. You will eat the flesh of heroes, you will drink the blood of the princes of the earth. They are all rams, lambs, goats, fat bulls of Bashan. You will eat fat until you are satiated and drink blood until you are drunk, in this sacrifice that I offer you. You shall be satisfied at my table with horses and steeds, with mighty men and with every man of war, saith the Lord Yahweh. " (Ezekiel, 39, 17-20.)

Ezekiel does describe a banquet where the flesh and blood of human beings are devoured. But these are the corpses of Israel's heroes who died on the battlefield and were devoured by ravens and wild beasts, a horrific image, but one that has nothing cannibalistic about it, and one that is found in the Iliad as well. It's by fragmenting the text, isolating formulas like " You will eat the flesh of heroes " or " You will eat fat until you're satiated and drink blood until you're drunk " (where you refers to birds and wild beasts, not Jews) that Voltaire obtains the revolting image his text needs, at the cost of a detour from the biblical text25.

The bad faith is certain and probably explains the disappearance in the 1764 article of this development that Voltaire mentions in his letter to Mme du Deffand. But what's more important is the logic of revolt through imagery that manifests itself here from Ezekiel's jams, we move on to the cannibal abomination, which concentrates the quintessence of all religious fanaticism. Voltaire wrote to Madame du Deffand: "If you had any curiosity, I would prove to you that there have been no peoples who have not commonly eaten little boys and little girls ".

Is this horror revolting ? What then of the current horrors of war in Germany ? " you'll even admit to me that it's not such a great evil to eat two or three, than to slit thousands of throats, as we politely do in Germany ". The Seven Years' War, which had begun in 1756, was raging at the time, and the French had suffered a bloody defeat at Minden in Germany in August 1759. From 1761, the full title of Candide became Candide, or l'optimism, with the additions that'we a. found in the pocket of the doctor, when'he died at Minden,. /// l'an de grâce 1759. Ezekiel was only a pretext, or at any rate a primer : what Voltaire aims at is the study of morals (" Vous ne souciez donc pas, madame, de connaître les mœurs des nations ? "), that is, not to map them, but, in the general spectacle of the world's present and past horrors, to grasp the principle of barbarism, which is also the principle of humanity.

Once and again, with Voltaire, we are caught in this balancing between fascination and abjection of the biblical text, between light-hearted derision of the absurdities of reality and revolted seizure in the face of injustice, between stigmatization of monsters and participation, at the peril of mud, in the nauseatingly human condition. Mme du Deffand was not a party to the fight to crush the Infamous, yet it is to her, with her in mind, that Voltaire writes the Dictionnaire philosophique that constitutes its militant discourse. The Dictionnaire is a work of propaganda and will end up being identified with the very figure of Voltaire ; and yet, Voltaire, either fear or publicity ploy, violently denies its authorship as soon as it is published.

Ecraser l'Infâme

On April 20, 1761, Voltaire wrote to D'Alembert : " Laugh and love me, confound the inf... as much as you can. " On the " 7th or 8th of May " of the same year, he adds, to the same addressee : " Come on then, do some service to mankind, crush fanaticism, without yet risking falling, like Samson, under the ruins of the temple it demolishes ". On February 25, 1762, speaking of Curé Meslier, who on dying had left a communist and atheistic will, Voltaire wrote, again to D'Alembert :

" Quoi ! Meslier in dying will have said what he thinks of Jesus, and I will not tell the truth about twenty detestable pieces by Pierre, and about the sensitive defects of the good ? Oh pardieu, je parlerai good taste is preferable to prejudice, salve reverentia. Crush l'inf..., I beseech you. "

" Confuse l'inf ", " crush fanaticism ", " crush l'inf... " : the formula was born26. It will now run like a red thread through Voltaire's correspondence, " Ecrasez l'Infâme ", " Ecr.linf27 ", " Ecra. l'Inf " ? L'infâme is feminine ; this monster essentially designates fanaticism, and first and foremost religious fanaticism.

According to René Pomeau, Frédéric II was the inventor of the infamous. In May 1759, he wrote to Voltaire :

" You have made the Tomb of the Sorbonne ; add that of parliament, which rambles so loudly that it won't28 make it long. As for you, you won't die. You will still dictate, from the Delights, laws to Parnassus you will still caress the inf... with one hand, and scratch it with the other you will treat it as you do me and everyone else.

You have, I presume,

In each hand a feather ;

One, candied in sweetness,

Charmed by its flattering tone

The self-esteem it kindles,

Watering him with her error;

The other is a vengeful sword

That Tisiphone and his sister

Plunged into the bitumen

And all the acrid blackness

of the infernal bitterness Of infernal bitterness;

It hurts you, it consumes you,

Pierces your bones and your heart."

According to Frédéric, /// Voltaire's relationship with the infamous is ambiguous: caressing it with one hand, scratching it with the other, Voltaire manipulates it with not one, but two feathers. The infamous is not simply an enemy to be destroyed, a flaw in civilization that simply needs to be removed. The infamous is, along with barbarism and its horrors, the other side of barbarism, culture and civilization. Its allegory, its figure is the woman, object of all desires, and biblical instrument of the Fall.

Or precisely, in the formula that was to become the leitmotif of the Voltairian campaign, fâme, femme is not pronounced : " you will still caress the inf... with one hand " writes Frédéric ; Voltaire, in a letter to D'Alembert dated June 23, 1760, perhaps already thinking of the Traité sur la tolérance, writes :

" I would like to see, after these deluges of jokes and sarcasm29, some serious work, and yet one that would be read, where the philosophers would be fully vindicated and the inf... confounded. "

The woman is elided, suspended on the threshold of a fascinating but monstrous vision, which can only be verbalized through the detour of culture and philosophical engagement. Here, we touch on the imagination of Frédéric, whose homosexuality was repressed and atrociously humiliated by his father (corporal abuse, exile of page Keith in 1728, execution of Katte in 1730) it is through the society of philosophers and the culture of French that, from 1736 onwards, Frédéric compensates for a sexual outpouring that is either impossible or forbidden to him. L'infâme, c'est l'un-femme, ou l'un en guise de femme, the whole denied, repressed, rendered inaudible.

The Voltairean imaginary is not that of Frédéric. But Voltaire will exploit the ambivalence of the infamous. In September or October 1759, he wrote to Mme d'Épinay :

" Oolla and Oliba give you a thousand compliments, I commend the infamous to your holy hatred. "

Oolla and Oliba are two prostitute sisters from the Book of Ezekiel, allegorical figures of the corruption of the kingdom of Israel given over to idolatry and foreign invaders. Voltaire likes to evoke them in his correspondence, not only for the libertine filth they represent, flourishing right in the middle of the sacred books, but also most certainly for the sonorous effect of their names stuck together : Oolla and Oliba resounds like a cheerful infant's babble it's the echolalia of childhood, its joyful innocence, and at the same time the sordid horror of universal fornication, and even more, of the barbarism of fanatics.

In this recommendation to Mme d'Épinay, we find the dual relationship to the infamous, whom Voltaire recommends, thus precipitates into the arms of the Parisian muse of the philosophers, but recommends to her hatred instead of her friendship or protection, the formula we would expect here according to usage. To recommend to hatred is, in the final analysis, to tear from Mme d'Épinay's arms, not to precipitate the infamous into them.

By its very nature, écraser l'infâme cannot therefore take the form of a massive militant campaign. Too much affect, too complex and loaded an imaginary is at stake : the Voltairean campaign will be essentially epistolary, and will target selected recipients. Voltaire did not speak of the infamous to all his correspondents. The formula, initially reserved for Frédéric II and Mme d'Épinay, was extended to D'Alembert, Thiriot, d'Argental and Damilaville, but hardly beyond. It persisted at least until 1765. But it does not appear in public writings, such as the Traité sur la tolérance or the Dictionnaire. /// philosophical30, although in a way it motivates and accompanies them.

We must never forget this intimate character of Ecr. L'Inf., which is never reduced to a simple ideological watchword. The slogan also designates the object produced. Ecr. l'Inf. is the horizon that Voltairian discourse confronts, but at the same time it constitutes that discourse, ritually frames it, and ultimately identifies with it. The abjection, the horror of Ecr. l'Inf. draw the movement of a conjuration and fix, fetishize this conjuration as a work. The work becomes a Ecr. l'Inf. Thus in this letter to Damilaville of February 5, 1765 :

" My dear brother, écr. l'Inf. I am occupied only with écr. l'Inf. It is the consolation of my last days. Say écr. l'Inf. to everyone you meet. You will incessantly have the little Destruction of alembertine31 which is a good ecr. the Inf. and the first traveler who leaves for Paris will bring you a good supply of small diabloteaux32.

M. de Laleu must give you an important paper, concerning my temporal affairs it's my will, don't get me wrong, to which I must make a few additions. Although this work is not an ecr. l'Inf., I nevertheless recommend it to your kindnesses which extend to all objects. "

Voltaire opens with a sacramental word, " Mon cher frère, écr. l'In. " ; he goes on to designate the purpose, the direction of his speech, " Je ne suis occupé que d'écr. l'Inf. " ; speech becomes contagion, epidemic disease, " Say écr. l'Inf. to everyone you meet ", on the model of the fanatical contagion it is intended to ward off finally ecr. l'Inf colonizes and fixes the work as object-fetish : " la petite Destruction d'alembertine qui est un bon écr. l'Inf. ", " Quoique cet ouvrage ne soit pas un écr. l'Inf. ".

The publication of the Dictionnaire philosophique played a decisive role in this fetishization process.

The publication of the Dictionnaire philosophique in 176433

The Dictionnaire philosophique appears, no longer as a project, but as a printed work, in Voltaire's correspondence in July 1764. Voltaire denies authorship34 :

" My dear brother, I'm not wasting the little time I have left to live. I well suspect what Brother Cramer will show you ; but I do not believe that this work should ever be sold with privilege. " (Letter to Damilaville, July 6, 1764.)

The Dictionnaire isn't even named when Voltaire is already disowning it. Brandishing his seventy years, he declares himself too old to write. Cramer, not technically the publisher of the first edition35, published the Traité sur la tolérance in 1763 and would publish the 1769 edition, after which Voltaire stopped augmenting his Dictionnaire. But François Grasset was the Cramers' first clerk, before leaving them in 1753 to found his own firm in Lausanne. It was his brother, Gabriel Grasset, who in Geneva published the /// Dictionnaire philosophique : he was never troubled for this banned book and even burned in front of Geneva's town hall (Sept. 24, 1764), thanks to the protection of Gabriel Cramer, member of the Council of the Republic.

Voltaire most likely signifies to Étienne Noël Damilaville, by this letter, that Gabriel Cramer will bring him the Dictionnaire philosophique, with the mission of ensuring its distribution, as he was the philosophers' letter carrier. Indeed, as first clerk at the Vingtième office, he benefited from the postal franchise, i.e. a mail service escaping censorship. Damilaville took full advantage of this for his philosopher friends.

Warning him in a very neutral way that the Dictionnaire would not obtain the King's approval and privilege, Voltaire made Damilaville understand that the work would have to be distributed clandestinely.

These disavowals and precautions are a double entente : Voltaire's measures to protect himself must certainly be taken seriously. The book was dangerous, and any link between it and its author had to be severed. The Paris parliament, in a ruling dated March 19, 1765, condemned to fire the Dictionnaire philosophique, and the history of the Chevalier de La Barre, beheaded in 1766, among other things because the Dictionnaire philosophique had been found in his home36, will vindicate these precautions. When the knight's body and head were placed on the pyre in Abbeville on July 1er, 1766, the Dictionnaire philosophique37 was thrown in, as provided for in the award38.

" Useful books should belong to no one39 "

But there is also, at the same time, a malice of denial. Voltaire knows that the book's success stems both from its scent of scandal and from the network of reader-diffusers that scandal itself can motivate :

" I ask you in grace to confound every barbarian and false brother who might suspect me of having put his hand to this holy work. I want the good of the church, but I renounce martyrdom and glory with all my heart. Know that God blesses our nascent church ; three hundred Mesliers, distributed in a province, have operated many conversions. " (Continued from previous.)

The distribution of the Testament du curé Meslier, rewritten (and watered down) by Voltaire, be used as a model for that of the Dictionnaire philosophique. Voltaire builds his network on the model of the early church.

To deny authorship is to sign the book to proclaim renunciation of martyrdom and glory is to designate oneself as the protagonist, the hero of a new ideological adventure on the scale of that led by Christ. The symbolic system attacked by the Dictionnaire philosophique is also the one on which it is modelled. Christian fanaticism, denounced in the article Fanatisme as a disease that gangrenes the brain (p.191), is at the same time the brutal, fascinating expression of the force of the symbolic principle, the force to which Voltaire always returns and whose energy he aims to absorb and recuperate. Getting out of the Christian church through the Dictionnaire philosophique will be done by refounding the Voltairian church : " je veux le bien de l'église ".

A strategy of withdrawal

In his July 9 letter to the same Damilaville, Voltaire clarifies his strategy : " the best way to /// fall on the infamous is to appear to have no desire to attack him " (p. 391). Unlike the Traité sur la tolérance, the Dictionnaire philosophique is not intended as a polemical work. We find here the strategy of withdrawal : disengagement of the author, disengagement of the discourse, it is through the work of the negative that the Voltairean strategy is constituted. It's all about " letting the reader draw the consequences " ; " the work will say less than it thinks, and [it] will make people think a lot ". The Dictionnaire philosophique therefore features neither a famous author nor an assertive discourse, even if both are known to and present for the public. Instead, the aim is to present a different kind of presentation, to offer a chance to reread " antiquity " and " ancient history ". The author is " an old pedant, surrounded by old in-folio40 " : Voltaire paints himself as Dom Calmet41 and, like Calmet, claims to illuminate texts through reasoned exegesis. It's all about " untangling a little of the chaos of antiquity ".

But the need for pleasure soon mingles with the need for clarity : we'll have to " tâcher de jeter quelque intérêt " ; from interest, we move on to pleasure (" répandre quelque agrément sur l'histoire ancienne "), then from pleasure to laughter : " ce qu'on nous a donné pour respectable est ridicule ". Aesthetic pleasure served as a vehicle for turning exegesis into philosophical revolt. Unravelling becomes ridiculing explanatory unveiling is reversed into ironic contradiction. This is the movement of the articles in the Dictionnaire philosophique, obeying Voltaire's perfectly concerted strategy. Exegesis does not constitute a discourse on the Bible, or even against it explaining, unfolding ancient history, it deconstructs it, fragments it, puts it in contradiction with itself. Scholarly culture becomes dialogical material.There is no discourse of the Dictionary philosophical, but a device : device of dissemination first, of reading second, device of discourses finally, which the Dictionary dialecticizes and reverses.

Fiction d'un Portatif " de plusieurs mains "

Voltaire does everything in fact to give the illusion of a plurality of discourses, of voices in the Dictionnaire philosophique. Is it nostalgia for the aborted project in Potsdam in 1752 ? In a further attempt to prove that he was not the author, he intends to demonstrate that the work is collective. In his letter to D'Alembert dated September 19, 1764, he states that " ce recueil est de plusieurs mains, comme vous vous serez aisément aperçu " (p. 394) ; to Damilaville, on the same day : " On doit regarder cet ouvrage comme un recueil de plusieurs auteurs fait par un éditeur de Hollande " (p. 396), the latter intended to divert attention from Geneva, Cramer and Grasset, and Ferney ; on October 1er, to D'Alembert : " c'est une rhapsodie, un recueil de plusieurs morceaux détachés de plusieurs auteurs " (p.403) ; on October 12, to the same : " It is very true that this work is by several hands " (p. 408) ; and to detail the authors : Abauzit for Apocalypse42, Pastor Polier, of Lausanne, for Messiah43 ; Bishop Warburton44 for Enfer ; /// Idolatry would be an article from the Encyclopédie45. These half-lies are instructive not only does Voltaire reveal his sources and working method, for he has indeed drawn on the authors he cites, but he points to his great model, the Encyclopédie, whose symbolic effectiveness he seeks, with the Dictionnaire philosophique. It's not just a question, or even really, of disowning himself as an author. Taking his cue from Diderot and the Encyclopédie, Voltaire intends to be seen not as an isolated author, but as the conductor of an " société de gens de lettres " : the Encyclopédie46 formula, moreover, appears in Voltairean correspondence.

As in the letter to Damilaville of December 11, 1764 : " Je prie instamment tous les frères de bien vouloir crier dans l'occasion que le Portatif est d'une société de gens de lettres c'est sous ce titre qu'il vient d'être imprimé en Hollande " (p. 428).Same formula, again to Damilaville, on December 26 : we must go and speak to " Omer "47 and tell him " that he is sure that the Portatif is not mine, and that this work is by a society of people of letters very well known in foreign countries " (p.431). On July 27, 1767, Voltaire repeated this formula, on the occasion of a reprint of the Dictionnaire philosophique, in a letter to Coger, the conservative rector of the University of Paris : " You impute to me a Dictionnaire philosophique, work of a society of people of letters, printed under this title for the sixth time in Amsterdam, which is a collection of more than twenty authors, and in which I have not the slightest share. "

Voltaire fleetingly tried his hand at other strategies. In early October 1764, he imagined a fictitious author for the Dictionnaire philosophique, " un nommé Dubut " (letters to D'Alembert and Damilaville of October 1er, pp.403 and 405), " le jeune homme nommé Des Buttes " (to Damilaville, October 3, ibid.). The scenario had been and would be used for other works by Voltaire, such as the Traité sur la tolérance in 176348, or like the Philosophie de l'histoire attributed when it appeared in 1765 to an Abbé Bazin49. But this diversion only lasts a few days. On October 12, Voltaire is about to declare to D'Alembert: " Quelques personnes ont rassemblé ces matériaux, et je puis y avoir quelque part " (p. 409). But he immediately retracted his statement. On October 19, to the same : " it is the pure truth that this book is by several hands, and that it is a collection made by an ignorant bookseller " (p. 411).

The Dictionary, a " convenient " arrangement of discourse

The model Voltaire adopts is that of the book-dispositive, of what he calls a " rhapsody " i.e. not " a system " philosophical system constituting a discourse, but a " convenient arrangement " likely to draw a wide audience into its net. This was perfectly understood by Jean-Robert Tronchin, in the letter he addressed to the Council of Geneva on September 20, 1764:

.

" Let us add that the form of this book, in which the subjects are distributed in alphabetical order, makes its substance more dangerous it is not a system, whose propositions /// dependent on each other have force only in so far as they prove each other, which hardly appeals to that numerous order of readers out of condition to follow the chain of ideas, and whose defect would be easily seen by those who could embrace it they are detached articles, whose convenient arrangement leaves them the unfortunate facility of finding in it what can flatter them most, and which is most proportionate to the degree of their intelligence. " (P. 398.)

Voltaire himself compares himself, as author-non-author of the Dictionnaire philosophique, to Harlequin on two occasions. In the letter to D'Argental dated November 2, 1764, he writes :

" Besides, what can one say to V. when V. has given this work to no one, and when he first cried thief, like Harlequin robbing houses ? V. is intact. V. wraps himself in his innocence" (P. 421.)

A Arlequin dévaliseur de maisons or les Fâcheux, a comedy in five acts, was performed at Fontainebleau in 1724. A Pantalon lover unhappy or Arlequin. valet étourdi and dévaliseur de maison, a three-act play on an Italian canvas (la Casa svaligiatà), was performed in 1716 at the Théâtre du Palais-Royal50.

In 1770, Voltaire would take up this comparison in the Questions sur l'Encyclopédie, in section VI of the article Ame :

" the greatest benefit of which we are indebted to the new Testament, is to have revealed to us the immortality of the soul. It is therefore in vain that this Warburton has tried to throw clouds over this important truth, by continually representing in his legation of Moses, " that the ancient Jews had no knowledge of this necessary dogma " [...] English philosophers have even reproached him with how scandalous it is in an Anglican bishop to manifest an opinion so contrary to the Anglican church ; and this man after that ventures to call people impious : similar to the character of Arlequin, in the comedy of the Dévaliseur de maisons, who, after throwing the furniture out of the window, seeing a man carrying some away, shouted with all his might : Au voleur ! "

We thus understand that Harlequin the house robber is a figure of the robbed thief : the one who reproaches the public for attributing the Dictionnaire philosophique to him has done far worse before to ransack the house of the infamous. Voltaire claims to be innocent he reduces himself to V. ; but at the same time he exhibits himself like the Harlequin of farce. Voltaire wraps himself in anonymity ; but this anonymity is a shimmering Harlequin coat, the rhapsodic coat that qualifies the Dictionnaire, identified with an arrangement of disparate pieces.

With the Duc de Richelieu, on February 27, 1765, Voltaire took up the metaphor : " so, don't go, please, defending me as Scaramouche defended Harlequin, confessing that he was a drunkard, a gourmand, a debauchee, attacked by shameful diseases, and apologizing to Harlequin, telling him that these were flowers of rhetoric. " (P. 432.)

Voltaire denies himself, depreciates himself, disseminates himself into a plurality of authors, hands, pieces to his mantle. This trivialization of the auctorial function gives him the means for extraordinary success. On December 19, 1764, he wrote to d'Argental, concerning what was already to be a reprint of the /// Dictionary :

" It is said that some philosophers have added several insolent chapters to the Portatifs ; that it was printed in Holland with these irreligious additions ; that 4000 were sold in eight days, and that the sacrosanct is dropping like a stone throughout Europe. " (P. 429.)

4000 in eight days is an extraordinary throughput for the eighteenth century, especially for a clandestine work, distributed under the cloak. By way of comparison, on December 15, 1762, Voltaire told Cramer of a total print run of 4,000 copies for the first printing of Traité sur la tolérance, which would be insufficient51.

This success, Voltaire owes it to what he was able to combine : a noble purpose and a success of scandal, a moral, virtuous commitment in the fight for tolerance and a complacently grotesque encanailment in the jest of good and worst taste. The defender of the Calas family is also a Harlequin who robs houses.

This ambivalence of the Dictionnaire philosophique manifests itself vividly around a central subject of the book, which is also an ideologically difficult one that is, the role Voltaire assigns to the Jews in the constitution and deconstruction of the discourse of the Dictionnaire philosophique.

Notes

This first project, for a collective Dictionary in the spirit of Bayle's, was to come to nothing. Voltaire in the 1760s certainly recovered the material, but in an entirely different spirit, both more personal and more worldly.

And to Catherine II, July 24, 1765 : " I did not fail to seek out Abbé Bazin's nephew to communicate to him the letter with which Your Imperial Majesty honored me. He is a retired and obscure man, but your glory has come to him it is dear to him, he knows the extent of your genius, your spirit, your courage. "

///

See letter to D'Alembert, June 10, 1760.

Letter to Mme d'Épinay, July 14, 1760.

Letter to D'Alembert, May 21, 1760.

Letter to d'Argental dated March 2, 1762.

The link is perhaps made, for the association of ideas, with the fagots : Voltaire is in litigation with President de Brosses, whom he nicknames " le fétiche ", " pour douze moules de bois " in Tourney, otherwise known as fagots (letter to Fyot de la Marche, Nov. 4. 1761 to Le Bault, March 22, 1762 this last letter is also the 1stère in the correspondence to mention Calas). And to smell the fagot (the stake) is to be a heretic... like Rochette. See R. Pomeau, " Écraser l'infâme ", Oxford, 1994, chap. III, pp. 48-53.

The epithet " mes anges " is the consecrated epithet for the D'Argental in Voltaire's Correspondance. The effect here is not its use, but its place framing the evocation of the Rochette affair.

A majority of two votes was needed to secure a death sentence.A sixth judge favorable to Calas would have given a score of 7 to 6 for death, which was insufficient.

Letter to d'Argental, March 27, 1762.

The engraving is by Jean-Baptiste Delafosse, after Carmontelle. Its title is: " La Mère, les deux Filles, avec Jeanne Viguière, leur bonne Servante, le Fils et son ami, le jeune Lavaysse ".

See the letter of April 22, 1765, and the letter to Damilaville of May 20.

Letter of August 7. /// 1762.

The rehabilitation of the Calas family was pronounced on March 12, 1765. Voltaire receives the Sirvens at Ferney on April 5.

The project for a Dictionnaire philosophique is older. Voltaire, who had settled in Cirey with Mme du Châtelet, had spent 11 years reading and commenting on the Bible (see R. Pomeau, " Avec Mme du Châtelet ", chap. II, p. 33). According to Étiemble, " the dictionary project was born in Potsdam, on September 28, 1752, during a royal supper. Frédéric had promised his support. The very next day, Voltaire began writing within a few weeks, he had finalized the articles Abraham, Soul, Atheism, Baptism, Julien, Moïse ; but Frédéric balked, the others too soon it was a falling out with the philosopher-king. " (Preface to Dictionnaire philosophique, Garnier, ed. 2008, p. xxxv. But where did Étiemble get this list ?) See letter to Frédéric II, Sept. 5, 1752, " Nous avons de beaux projets pour l'avancement de la raison humaine " , which would allude to the project for a Dictionnaire philosophique. See especially, late Sept-Deb Oct 1752, " I place at your feet Abraham, and a Catalogue [=an alphabetical table of the Dictionnaire]. The Father of Believers is only sketchy because I'm bookless. But if Your Majesty casts his eyes over this article in Bayle, he will see that this sketch is fuller, more curious and shorter. This book honored with a few articles from your hand would do the world good. Chérisac [=the Marquis d'Argens] would sink the sts pères to the bottom. " We are at least assured by this letter that a draft of the Abraham article was written in October 1752.

See Mme du Deffand's letter to Voltaire of September 5, 1760.

Mme du Deffand is therefore not of Voltaire's " parti ":" You are a great and amiable child, Madame. How could you not feel that I think as you do But consider that I am of a party, and of a persecuted party, which, persecuted as it is, has nevertheless obtained in the end the greatest advantage one can have over one's enemies, that of making them both ridiculous and odious. You therefore feel what one owes to the people of one's party. " (Letter to Mme du Deffand, September 12, 1760.)

In fact, Voltaire had been meditating on Ezekiel for some time. See in particular the end of the letter to Mme du Deffand of September 17, 1759, which already contains a kind of program for the article, and that of October 13, where Voltaire advises her to read the Old Testament. And he adds: " But you, madame, do you pretend to read as one does conversation ? to take a book as one asks for news ? to read it and leave it there ? to take another which has no connection with the first, and leave it for a third ? To have pleasure, you need a bit of passion you need a great object of interest, a determined desire to learn, which occupies the soul continually this is difficult to find, and cannot be given. You're disgusted you only want to amuse yourself, I can see that and amusements are still quite rare. "

This could be the Catechism of the Curé.

The heart of the letter is devoted to theater : Voltaire loathes the spectacle of the scaffold, and criticizes Shakespeare.

See also the letter of December 22, where Voltaire worries that " les rogatons " have not arrived safely : " Il y a eu, madame, de la réforme dans les postes. The big packages no longer go through."

At the article Déjection des Questions sur l'Encyclopédie, Voltaire will write : " We have known the treasurer Paparel to eat the droppings of milkmaids ; but this case is rare, and it is one not to dispute tastes. " Prévost already evoked Paparel's coprophagia in Mémoires d'un homme de qualité : " What is certain is that if he had a miserly and corrupt soul, he had no less deranged imagination ; he would deserve to die, the Abbé du Bois tells us, if only to purge the human race of a monster who dishonors it they assure us that his most exquisite food is the excrement of the first person to come along. At first I didn't understand the meaning of this expression, but I was enlightened to learn that Mr Paparel commonly ate the product of natural necessities; that he even always carried a small spoon with him for this purpose, and that more than once, on seeing a lackey in good health, he had stopped him and engaged him for money to make him a few pieces of this horrible meat. This derangement of taste seemed so strange to me, that I would not dare report it as a truth, if the assurances I was given had not been strong enough to convince me (MHQ, t.VI, p.468, variant on p. 291). The anecdote was censored in the 1756 reprint. See Érik Leborgne, "Le régent et le système de Law vus par Melon, Montesquieu, Prévost et Lesage", Féeries, 3, Politique du conte, 2006). Claude François Paparel (1659-1725), of commoner origin, grew rich under Louis XIV and then under the Regency as Treasurer of the Extraordinary of Wars. Convicted of fraudulent enrichment at the expense of the state coffers, he was sentenced to death in 1716. His sentence was commuted to life imprisonment; he eventually lived on a pension in Provence, and died rehabilitated in Paris in 1725. During his captivity and exile, his cook never left his side...

Ezekiel obviously doesn't speak, in the Bible, on his own behalf, but reports the words God communicated to him : " The word of Yahweh came to me in these words : What have you to repeat this proverb in the land of Israel : The fathers have eaten green grapes, and the teeth of the sons have been chafed ? By my life, oracle of the Lord Yahweh, you will no longer have to repeat this proverb in Israel. All lives are mine, the life of the father as well as that of the son, they are mine by law. Whoever sins, he shall die. Whoever is righteous [...] he will live, oracle of the Lord Yahweh. " (Ezekiel, 18, 1-9.)

In fact, as Calmet pointed out, this threat appears in the Exodus. Moses has ascended Sinai, and Yahweh is about to conclude the Covenant with the giving of the tablets of the law. Moses prays: "He called on the name of Yahweh. Yahweh passed before him and he proclaimed: Yahweh, Yahweh, God of tenderness and mercy, slow to anger, rich in grace and faithfulness who keeps his grace for thousands, tolerates fault, transgression and sin /// but leave nothing unpunished and punish the iniquities of the fathers on the children and grandchildren, to the third and fourth generation. " (Exodus, 34, 5.)

Moses article, p. 307.

The Vulgate text goes in Voltaire's direction : " et stercore quod egredietur de homine operies illud ", and you will cover it, operies, with the excrement, stercore, that will come out of man.

Voltaire would indeed acknowledge this in the article Jews in the Questions sur l'Encyclopédie : " If the Jews ate human flesh. Among your calamities, which have made me shudder so many times, I have always counted the misfortune you have had of eating human flesh. You say that this only happened on special occasions, that it was not you whom the Lord invited to his table to eat the horse and rider, that it was the birds who were the guests, I want to believe it. Obviously things are spun in such a way that the Jews still look guilty...

On May 4, 1762, D'Alembert wrote in response : " Ecrase l'inf..., do you keep repeating to me : eh, mon Dieu ! laissez-la se précipiter elle-même elle y court plus vite que vous ne penses. " Voltaire imperturbably concludes with " Écrasez l'inf... " on July 12, 1762. To which D'Alembert replies : " but will reason be the better for it, and the inf... the worse ? " On September 15, Voltaire concludes his letter to D'Alembert thus : " Criez partout, je vous en prie, pour les Calas et contre le fanatisme, car c'est l'inf... qui a fait leur malheur. " And D'Alembert on October 2 : " you see that philosophy is already beginning very noticeably to win the thrones, and farewell the infamous, if only it loses a few more. " Voltaire on November 28 : " Whatever you do, crush the infame, and love who loves you. " January 18, 1763 : " reason goes a long way. Crush the'infame. " April 1, 1764 : " Farewell, my dear philosopher ; if you can crush l'inf..., crush it and love me, for I love you with all my heart. "

" It is for you to laugh at everything, for you are well, and I am only an old sick man. Au surplus, écr. l'inf... " (letter to D'Alembert, May 1er, 1763). September 28 : " I embrace you very tenderly, my dear philosopher. Ecr. l'inf... ". December 13 : " defend the good cause, pugnis, unguibus and rostro ; enliven the brothers, continue to lard the fools and rascals with good words. Ecr. l'inf... " December 15 : " let us read holy Scripture well, and écr. l'inf... " February 13, 1764 : " Ecr. l'inf..., I tell you ". March 1er : " Keep me your friendship. Ecr. l'inf.... "

la = sa /// defense ? its agony ?

Probable allusion to Palissot's Philosophes.

For all this development, see René Pomeau, Voltaire in his time. " Crushing the'infamous ", Oxford, Voltaire foundation, 1994, p. 8.

D'Alembert's Sur the destruction of the Jesuits in France.

That is, copies of the Dictionnaire philosophique. In a letter to d'Argental dated October 22, 1764, Voltaire wrote: " Le petit abbé d'Estrée, qui n'est assurément pas descendant de Gabrielle, emploie toutes les ressources de son métier de généalogiste pour prouver que le diable engendra Voltaire, et que Voltaire a engendré le Dictionnaire philosophique. "

See Appendix I to the Naves-Ferret, Garnier edition, pp. 391-437.

Same denial in letter to d'Argental of July-August 1764 (D12027), to D'Alembert of September 7 (D12073). Voltaire would repeat these denials to these three addressees until the end of 1764.

The first edition of the Dictionnaire philosophique is published in Geneva by Gabriel Grasset. The name of the author, city and publisher do not appear on the title page, which only mentions the date, 1764, and London, to mislead the censors. See the illustration booklet of the Naves-Ferret edition.

October 10, 1765. See René Pomeau, " Écraser l'infâme ", chap. XVI, p. 296

Ibid., p. 301.

Ibid., p. 297.

Voltaire to Damilaville, November 2, 1764.

Compare with the letter to Frédéric II of September 5, 1762, where Voltaire first alluded to a planned Dictionnaire philosophique. The letter begins : " Your pedant in points and commas, and your disciple in philosophy and morals, has profited from your lessons, and lays at your feet La Religion naturelle, the only one worthy of a thinking being. "

Antoine Calmet (1672-1757), Dom Augustin in religion (he was a Benedictine), is the author of the monumental Commentaire littéral et critique de la Bible (1707-1716, 23 volumes in-4°), a Histoire de l'Ancien et du. New Testament and ofthePeople Jewish, 1718, 2 vols., and the Dictionnaire historique et critique de la. /// Bible, 1722-1728, 2 vols. in-fol.

Firmin Abauzit (1679-1767) was a Calvinist scholar who took refuge in Geneva. His Discours sur l'Apocalypse was not published until 1770. Voltaire condenses and adds.

Voltaire actually edited and corrected the manuscript by Jean-Antoine Noé Polier de Bottens (1713-1783).

William Warburton (1698-1779), Bishop of Gloucester since 1759, had just published, in 1762, The Doctrine of Grace. Is it to him that Voltaire alludes at the end of Enfer, when he writes that " It was not long ago that a good honest Huguenot minister preached and wrote that the damned would one day have their grace, that there had to be a proportion between sin and torment, and that a fault of a moment could not merit infinite punishment. The priests, his confreres, deposed this indulgent judge". But Warburton was not deposed, and the case referred to would rather be that of Pastor Petitpierre, deposed in 1760 in Neuchâtel.

Voltaire did indeed send it to D'Alembert for inclusion in the Encyclopédie in 1757. But the revocation of the privilege suspended its publication until 1765, with the last ten volumes of texts. The text also appears, summarized, as chapter 30 of La Philosophie de l'histoire.

The full title of the Encyclopédie was Encyclopédie, or dictionary reasoned of the sciences, of the arts and trades, received from best authors, and particularly from dictionaries English from Chambers, d'Harris, de Dyche, &c. by one company. of people of letters. Mis en ordre & published by M. Diderot ; and quant à la partie mathématique, by M. D'Alembert. See also the article Gens de lettres in the Encyclopédie, which is by Voltaire.

Joseph Omer Joly de Fleury (1715-1810) was avocat général at the Grand Conseil (1737-1746), then at the Parlement de Paris (from 1746) and finally president à mortier. A staunch opponent of the philosophers, against whom he obtained the banning of the Encyclopédie and the Poème sur la loi naturelle in February 1759, the banning of variola inoculation in June 1763, " Omer " was made famous by the jokes Voltaire heaped on him : Voltaire called him the /// " petit singe à face de Thersite " (Pantaodai à Mlle Clairon, 1761), then " maître Omer ", and said of him that he was " ni Homère, ni joli, ni fleuri ". Omer Joly de Fleury delivered an indictment against the Dictionnaire philosophique in March 1765.

" Beware of imputing to secularists a little work on tolerance that is soon to appear. Il est, dit-on, d'un bon prêtre il y a des endroits qui font frémir, et d'autres qui font pouffer de rire car Dieu merci, l'intolérance est aussi absurde qu'horrible. " (Letter to Damilaville, Jan. 24, 1763.)

In his letter to Damilaville dated March 25, 1765, Voltaire writes : " M. d'Argental must give you seven or eight copies of a book entitled Dictionnaire philosophique, which slander has quite indignantly imputed to me. You will have in a while La Philosophie de l'histoire, and you will see in it things that are as true as they are little known. This work is by an Abbé Bazin who respects religion as he should, but who has no respect at all for error, ignorance and fanaticism. [...] We can burn it for everything it suggests, but in my opinion we cannot condemn it for what it says. "

Molière's ballet Les Fâcheux (1661) is said to be drawn from the same canvas. But there's no Harlequin robbing houses.

And in December 1763, he advised Gabriel Cramer " to print a thousand copies on the spot, which you would send by Lyon straight to Paris ".

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Introduction au Dictionnaire philosophique », cours d’agrégation donné à l'Université de Provence, Aix-en-Provence, automne 2008.

Voltaire

Archive mise à jour depuis 2008

Voltaire

L'esprit des contes

Voltaire, l'esprit des contes

Le conte et le roman

L'héroïsme de l'esprit

Le mot et l'événement

Différence et globalisation

Le Dictionnaire philosophique

Introduction au Dictionnaire philosophique

Voltaire et les Juifs

L'anecdote voltairienne

L'ironie voltairienne

Dialogue et dialogisme dans le Dictionnaire philosophique

Les choses contre les mots

Le cannibalisme idéologique de Voltaire dans le Dictionnaire philosophique

La violence et la loi