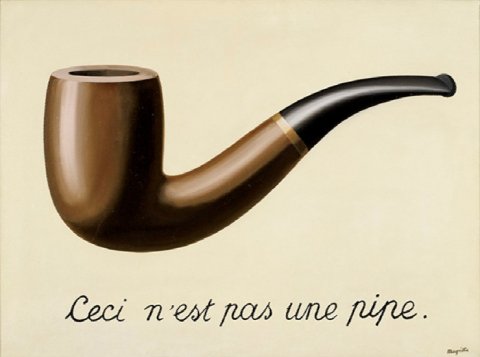

La Trahison des images (Ceci n'est pas une pipe) - René Magritte, 1929 - Los Angeles, The Los Angeles County Museum of Art

This is not a tale1...

Voltaire published Zadig in 1746 in its first version, Candide in 1759, L'Ingénu in 1767. Today we call these texts Voltaire's Contes, and we write this title in italics as if Voltaire had compiled them into a collection under this name. There is no such thing, and this is a pedagogical invention of the 20th century : a three-volume edition of the Romans et contes de M. de Voltaire appeared in 17782. But the table of contents quickly makes us realize that what we call fairy tales is in fact, for the publisher, novels, while the fairy tales, explicitly designated as fairy tales, refer to other texts, which our predagogical anthologies have relegated, or even excluded from the corpus3. Similarly, the successive complete works published during Voltaire's lifetime and under his control reserve, from 1768 onwards, a section " Romans " for our... contes4. The first separate publication of each of the three texts, Zadig, Candide and L'Ingénu, confirms this characterization, which we shall see is in fact not one.

Zadig, ou la destinée is published with a subtitle, " Histoire orientale ". In a letter to the Comte d'Argental, Voltaire writes :

" Au reste, vous parlez de Zadig comme si j'y avait part ; mais pourquoi moi ? Why do you call me ? I don't want to have anything to do with novels" (Châlons, September 12, 1748)

This is not a tale, and Voltaire didn't write it. As for the genre, it's a novel. The strategy and characterization is the same for Candide. Shortly after Candide left the presses, Voltaire wrote to Thiériot5 :

" I have read Candide ; it amuses me more than the History of the Huns6, and than all your ponderous dissertations on commerce and finance. Two young men from Paris have told me they look just like Candide. I look enough like Signor Pococurante7 but God forbid I should have the slightest part in this work ! I have no doubt that M. Joly de Fleury8 will eloquently prove to all the assembled chambers9 that this is a book against morals, laws and religion. Frankly, it's better to be in the land of Mumps10 than in your good city of Paris. You used to be monkeys gamboling now you want to be oxen ruminating : it doesn't suit you. " (Aux Délices, March 10, 1759)

Parisians used to resemble the monkeys of the Mumps country : that was the gay libertinism of the Regency. Now, the most conservative and dreary reaction reigns France has become a country of oxen. But of course Voltaire didn't write this..." ouvrage ", this..." livre ".

To the Marquis de Thibouville, he wrote a few days later. /// late :

" I have read at last, my dear marquis, this Candide of which you spoke to me ; and the more it made me laugh, the angrier I am that it should be attributed to me. Besides, whatever novel you make, it's hard for the imagination to come close to what's been going on all too truly on this sad and ridiculous globe for the last few years. We are a little interested, Madame Denis11 and I, in public misfortunes, in the persecution aroused against very estimable philosophers, in everything that interests the human race and when our friends speak to us only of plays and novels that are perfectly unknown to us, what do you expect us to answer ? " (At the Château de Tournay, by Geneva, March 15.)

This is still a novel, not a tale, and the word " novel " is to be taken less in the sense of an established genre than of a frivolous matter, an amusement that is not serious : " to make a novel " is to tell anything, to make lots and lots12. It's not serious, then, a new denial : the imaginative fantasies of Candide contrast with " what's happening all too really " in the world, with its brutal reality13.

L'Ingénu in the same way is not characterized as a fairy tale, but as a novel. It was announced by Grimm in November 1766 in the Correspondance littéraire :

" It is also said that the patriarch is working on a theological novel, and that so long as it resembles the theological novel of Candide, it will not fail to be edifying. "

Of course, the theological novel is not a genre at best, it's a parody of one. Roman théologique is an oxymoron, which attaches to a serious adjective, suggesting a scholarly compilation or erudite dissertation, a noun from the worldly vocabulary of light conversation.

On August 1er, 1767 Grimm uses the same expression :

" After the plagues of Egypt, I hardly know of a greater calamity than that which spread over France and operated a universal dearth of spiritual nourishment14. There is so far only one copy of the Défense de mon oncle15 in Paris, in the hands of M. d'Argental16. There is talk of a theological novel entitled l'Ingénu, and also worked on in Ferney ; but no one knows of it yet in Paris. In the past, this great city, like a general store, had an assortment of everything, and each devotee could provide for himself according to his needs and means ; today, you have to have letter carriers and commission agents in the vicinity of the main factory17 you have to deceive the whole cohort of clerks, inspectors, exempts and henchmen, when you want to have these precious commodities : that's what I wish for every faithful man who isn't afraid to spend money for his salvation. "

The novel of L'Ingénu is above all a book that cannot be found. It is lacking, missing. By virtue of its precious rarity, it becomes, contrary to official theology, an adventure, a theological quest for its reader, for " tout fidèle " of philosophers seeking " son salut " in the reading of good books, i.e. forbidden books. Roman then designates an anti-novel, the very opposite of easy, frivolous and cheap literature : the novel of L'Ingénu initiates for its readers, who become its " faithful ", a theological anti-parcours, a way of the cross transformed into a hide-and-seek with customs, at the end of which is promised, for a price /// gold, the " salute ".

A few days later L'Ingénu appears in the postscript of a letter from Voltaire to M. Lacombe, bookseller in Paris :

" N. B. You will know, sir, as a man of wit and taste, that there is in the world a man named M. Dulaurens, author of Compère Matthieu18, who has made a little work entitled l'Ingénu, which is much courted by men, women, girls, and even priests. This gentleman Dulaurens came to see me: he told me, before leaving for Holland19, that if you could print this little work, he would send it to you from Lyon to Paris by post. M. Marin mandated me that he had read this work by chance, and that we would give tacit permission20 without any difficulty. " (At Ferney, August 7, 1767)

So this is a " ouvrage ". Voltaire always uses the most undifferentiated, distant term, as if for an object held with tweezers. This mysterious object, of which he writes on August 7 that it is " couru ", by the whole world, i.e. sought-after, prized, becomes the next day a chimera, a book that doesn't exist. He writes to Damilaville21 :

" I have sent for l'Ingénu of which you speak to me he is not known. It's very sad that every day I'm accused not only of works I didn't do, but also of writings that don't exist. I know that many people are talking about l'Ingénu, and all I can answer very ingenuously22, is that I haven't seen it yet.

I send you my love. I kiss you very tenderly. " (August 8)

Our first apprehension of the genre of what we now call Voltaire's Contes proves radically disappointing. There is no genre of the tale, and Voltaire did not invent a genre that would be that of the philosophical tale. These writings first appear and spread as authorless and genre-less: the term " histoire ", which characterizes Zadig and L'Ingénu neither characterizes a genre ; " histoire " is the least determinant in terms of genre23, it's a way of freeing the narrative from any form of generic caracterization. What we call Contes are texts that free themselves from the poetic regime24 : no genre constraints are exerted on them, just as no auctoriality plays on this anonymous literature. Everyone knows that Voltaire is the author, but a radically irresponsible author, thus producing a radically free text.

Des contes malgré tout

However, we can't radically renounce the generic characterization of these texts as fairy tales, for they themselves refer to them. In the Epître dédicatoire à la sultane Sheraa25, which opens Zadig, we read, in reference to " cet ouvrage " :

" It was first written in ancient Chaldean, which neither you nor I hear. It was translated into Arabic, to amuse the famous sultan Ouloug-beb26. This was back in the days when Arabs and Persians were beginning to write A Thousand and One Nights, A Thousand and One Days27, and so on. Uloug liked reading Zadig ; but the sultanas liked Mille et un better. How can you prefer, the wise Ulug would tell them, tales that are without reason, and that mean nothing ? /// - That's precisely why we love them, replied the sultanas28. "

The falsified tales of Pétis de la Croix, whose gallant taste and gratuitous fantasy the Sultanes prefer, are here contrasted with " this work of a wise man " that is Zadig, translated at least twice before reaching us, if we were to take the dedicatory epistle seriously. Now, not only is the amount of erudition supposed to have gone into getting us to read Zadig in French after it was supposedly translated from Chaldean (the ancient language of Babylon, before Persian domination) and then from Arabic (but Uloug-beg spoke Persian), a joke, but conversely the Mille et un jours is much more consistently, if not without trickery, a translation !

The difference that is made between Zadig, a scholarly work, and Les Mille et un jours, tales without reason29, falls : it is posed in derision so that the reader revokes it. Here we are at the heart of what characterizes the enunciation of the tale, its spirit, in its singularity : presenting face to face what it claims not to be so that we hear that it is what it is. It is indeed a tale, but we only gain access to it through a double negation it is not true that this is not a tale. Better still : there is no difference between the nonsense of the marvellous tale and the wisdom of the serious work.

Candide has neither preface nor dedication. The reference to the genre is therefore more indirect. In the first chapter, Voltaire describes the protagonists at the beginning of his story :

" Monsieur le baron was one of the most powerful lords of Westphalia, for his castle had a door and windows. His very great hall was adorned with a tapestry. All the dogs in his barnyard made up a needy pack; his grooms were his pickers; the village vicar was his chaplain. They all called him monseigneur, and laughed when he told tales.

Madame la baronne, who weighed around three hundred and fifty pounds, was highly regarded, and did the honors of the house with a dignity that made her even more respectable. His daughter Cunégonde, aged seventeen, was colorful, fresh, fat and appetizing. The baron's son was worthy of his father in every way. The tutor Pangloss was the oracle of the house, and little Candide listened to his lessons with all the good faith of his age and character30. "

In this gallery of portraits, Voltaire seems to follow a hierarchical order, from the most important character, the baron master of the premises, to the least important, " le petit Candide ", the only one designated as small between these imposing figures. This hierarchy is parodic, not only because everything presented as a sign of the characters' importance is ridiculous, but also because the story will give them a place inversely proportional to this order of presentation.

.But above all, the division of the paragraphs and the similarity of their entries suggests a more subtle parallelism. The first paragraph doesn't actually say anything about the baron's figure, but rather about his environment : it sets up the setting, the walls, the dogs, the staff in which the baron holds court, and peregrinates. And this is called " making tales ". The second paragraph seems to open a portrait of the baroness that answers the portrait of the baron, but in fact unfolds all the other characters: at the end of the enumeration, a second court takes shape, totally unexpected, in reverse of the first. It's Pangloss's audience, reduced to Candide listening to him like an oracle, with the same reverence with which the grooms and the vicar listened to Pangloss. /// the baron.

There are thus two words, two modes of enunciation, the baron's tales and Pangloss's oracles : we find again the opposition of Zadig's dedicatory epistle, between the tale and the learned work. These two words are artificial, ineffective indeed, we doubt that this baron, who is pompously described to us as a common farmer, is capable of " faire des contes ", i.e. of having wit in conversation, of knowing how to furnish a light, pleasant, worldly exchange in a salon with anecdotes, pleasant traits. The tales he tells can't be good tales. And in parallel, we learn a few lines later that Pangloss's oracles consist of teaching " metaphysical-theological-cosmolonigology31 " : in other words, apparently learned discourse, and in fact completely niggardly.

In both cases, the speech doesn't fulfill its specifications, doesn't do what it should. In the same way, the château is no more than a farmhouse, the great hall decorated only with a draught-proof tapestry, the pack of racy hunting dogs reduced to a few good big barnyard dogs, the farmhands who look after the horses (the palefreniers) take the place of the piqueurs (the valets de chasse who lead the pack on horseback during hunts à courre), the vicar (there isn't even a titular parish priest) acts as the château's private chaplain. At the same time, the Baroness's importance is one of weight! Cunégonde is " haute en couleur ", which refers to a peasant whose cheekbones, beaten by the fresh air, are quite red, instead of the aristocratic pallor of young girls who live in the shadow of palaces and only go out protected from the sun32.

The importance, the brilliance, the aristocratic prestige of the Thunder-ten-tronckh family are all in the words (castle, great hall, pack, pikemen, chaplain) and the reverence rendered (" They called him monseigneur ", " a very great consideration ", " even more respectable "), to which the things don't correspond (the farmyards, the village, the baroness's 350 pounds, Cunégonde's colors). The weight of the things contrasts with the lightness of the words, which accumulate in an inconsequential causal chain: the " car ", " et ", " par là " are all absurd. And the son is " in everything worthy of his father ", i.e. he is totally unworthy...

The Baron's contes thus wink mischievously at Voltaire's roman, who also " fait des contes ", writing his bon mots to laugh against Pangloss's Leibnizian galimatias and to give to see, to feel the triviality, the irreducible harshness to the language of reality. The tale thus gradually and increasingly clearly takes shape as a three-term affair : imaginative fantasy, more or less gratuitous and successful, of the bon mot heavy deployment and learned accumulation of a metaphysical discourse background of reality contrasting with the discourse, by its triviality, its misery and, as we shall see later, by its brutality.

.During Candide and Cunégonde's crossing from Cadiz to Argentina, as Cunégonde complains of having been horribly unhappy in the old world, the old woman proves to her that there have been more unhappy than her by telling her story :

" I would never even have told you about my misfortunes, if you hadn't piqued me a bit, and if it wasn't customary, on a ship, to tell stories to take the edge off. Give yourself a treat, get every passenger to tell you his story, and if there's a single one who hasn't often cursed his life, who hasn't often said to himself that he was the most unfortunate of men, throw me into the sea with the most unfortunate of men! /// tête la première. " (chap. 12, p. 71)

The old woman's story constitutes a narrative embedded in the main narrative, according to a structure characteristic of the Baroque novel33. And the old woman's story, which presents itself as a succession of catastrophes, is in many ways a mise en abyme of Candide's story indeed, this is what the old woman herself suggests. As a result, when the old woman speaks of " telling stories ", when she proposes to Cunégonde to engage " each passenger to tell you his story ", it is also the enunciation of the main story that she characterizes.

It's a story, but this story is told. In the same way, the baron did tales. Voltaire is not characterizing a genre, but a way of speaking, of telling. This way has a very specific function, which is the same in the farmyard of Thunder-ten-tronckh castle and on the boat crossing the Atlantic : it's all about " se désennuyer ", when there's nothing else to do. The tale always refers to this emptiness of the setting, to a barred, vacant action. Voltaire borrows from the site and circumstances that constitute the enunciative frames of the two most famous collections of tales that preceded him : in Boccaccio's Le Decameron34, the narrators and their companions withdrawn from plague-stricken Florence tell their stories because they have nothing better to do until they return. In Marguerite de Navarre's L'Heptaméron35, the devisants are travelers stranded in an abbey in Cauterets, whom a storm has isolated from the world. Narrative kills time, storytelling is the pleasant way of telling, in this context where the signifier is enunciated far from the referent, where the word that tells is set back from the world that acts.

In chapter XIII of Candide, Voltaire reports that the passengers all told their stories, vindicating the old woman. Set back from reality, the tale reflects it in all its brutality it tells of the world's misfortune, " physical evil and moral evil " (p. 72). In chapter XIX, on his return to Europe from Eldorado, Candide renews the boat experience, with the same reflections (p.98). The setting in which the tales are told is even more explicit: Candide rents a room on the ship on which he is to set sail, promises to pay for the crossing to the most unfortunate storyteller, selects the twenty candidates who seem most sociable and gives them supper while they recount their misfortunes. Double pleasure of the mouth...: there's an enjoyment of storytelling, paired with the pleasure of the banquet and the retreat to the bedroom. The tale is an enunciation rather than a statement, and the symptom of a possible sociability the good storyteller will be the one with whom it will be pleasant to live for the duration of the crossing. The same enunciative structure is repeated in chapter XXVI, during Candide and Martin's Venetian supper with six dethroned kings (p. 126-128) it was already present in Zadig, in the Souper chapter, when Zadig, at the great fair of Balzora, finds himself at table with a collection of merchants from all countries who compare, based on their respective dietary prohibitions, the history of their peoples (p.59-62) the succession of tales of misfortune, or accounts of singularities, is not primarily aimed at historical or political knowledge, to inform the reader or the guests. But the banquet does seal the solidarity of the storytellers who, despite their particular misfortunes, join together to help Théodore, the short-lived and unfortunate king of Corsica, or embrace Zadig, who has brought them to agree on the principle of " a superior Being, on whom form and matter depend " /// (p.62).

The breakup of L'Ingénu

With L'Ingénu, the relationship between story and tale seems to disappear : there is not a single occurrence in the text of the word " conte ", nor of the verb " raconter ". This disappearance is perfectly concerted : the ingenuous is one who speaks ingenuously, naively, and this is not the way of the tale, which speaks to please and not to inform, unfolds its story to pass the time, and only tells the horror or absurdity of the world through the wit it can unleash.

.Just arrived in Brittany, the ingénu is invited by the Abbé de Kerkabon and his charming sister to dine at the priory. All " the good company of the canton36 " press him and even overwhelm him with questions :

" Monsieur le bailli, who always seized strangers in whatever house he found himself, and who was the greatest questioner in the province, said to him, opening his mouth half a foot : " Monsieur, what is your name ? - I've always been called l'Ingénu," replied the Huron, "and that name has been confirmed for me in England, because I always say naively what I think, just as I do whatever I want. " (chap. I, p. 45)

Voltaire has reproduced here the site and circumstances of the tale the ingenuous man is summoned to tell his story, before an assembly gathered on the borders of France, in a secluded place therefore, and come both to eat and to enjoy the tale. Voltaire emphasizes the oral pleasure: the bailiff "opens his mouth by half a foot", in astonishment at what the ingenue has just said, in admiration, but also in expectation of the words he is about to drink. In addition to the fact that it is materially impossible to open the mouth 15 cm, Voltaire plays on the measurement in feet, on a mouth that would belong to half a foot : the comical expression, literally absurd, telescopes body parts and precipitates the imagination into a chaos of membra disjecta.

She thus says, in advance, that the performance of the tale cannot be fulfilled. He who is summoned to say his name has no name, which is what the Ingénu wants to say, that is, no distinctive sign, no trait that characterizes him : his trait is the absence of trait no singularity, no programmed deformation of discourse characterizes him. Better still : " I do whatever I want ", the Ingénu situates and claims to be on the side of action, when the enunciative framework of the tale presupposes a barred action (the plague in town, a storm blocking the roads, the inaction of a long sea crossing or, simply, of a meal).

In L'Ingénu the performance will therefore consist in placing the hero in the situation of producing a tale, i.e. vain speech to please, to satisfy a pleasure of orality, and then disappointing the expectation thus aroused. There can be no fairy tales: times have changed, the time is no longer for courtly avanities (Zadig) or despair in the face of the world's misfortunes (the Lisbon earthquake, Candide), but for action. After the Calas affair, Voltaire has moved on to the Sirven affair ecrl'inf, he thinks he can act.

Narratio et Fabula : the tale according to Trévoux

So there is indeed a Voltairian tale, but one that doesn't let itself be grasped with as much obviousness and ease as we might have thought. We have defined the Voltairean tale as a double negation of the tale, then as a three-part game in which learned discourse, pleasurable discourse (the tale itself) and the blackness of reality confront each other, and finally as a withdrawn enunciative framework, presupposing a barred action and producing the oral pleasure of the banquet. Each time, the deceptive dimension of the tale is essential: it refuses itself as such; it melts into its opposite and breaks against the wall of reality; it dissolves into the pleasure of gratuitous performance, /// indefinitely renewed.

Is it for this reason that the tale is never called a tale from the outset ? Voltaire, however, did not disdain using the term for other texts, notably his Contes de Guillaume Vadé. In our three " novels ", the tale manifests itself as a relation to the tale, and it is the distance of this relation that forbids naming them directly as such. In the generic identity displayed by the tale, there is something with which Voltaire maintains an ambiguous relationship, and which he intends to go beyond. This something is not insignificance, which Voltaire adorns himself with and even wallows in to his heart's content. The Voltairean novel exceeds the tale, and it does so apparently with obviousness, since both its audience and its author recognize it from the outset and without discussion as a novel and not a tale.

What is this difference, which enables Voltaire to place novels and fairy tales in the same collection, thus conceding them a generic affinity despite everything, but yet clearly differentiating between what belongs to the novel and what belongs to the fairy tale ? Let's take a look at how Trévoux's dictionary defines conte :

" CONTE, s. m. Story, pleasant tale. Fabula. Les contes d'Ouville37, d'Eutrapel38, de Bonaventure des Périers39, de la Reine de Navarre40. Brevity is the soul of the tale. The Font[aine]41. Ésope sçu envelopper la vérité dans la fâble il faut beaucoup d'art pour déguiser ainsi en petits contes les instructions les plus importantes de la Morale. Fonten[elle]42. It is the characteristic of a great mind when it begins to age & decline, to take pleasure in contes & fâbles ; Boil[eau]43. You always need something spicy in contes. S[aint] Evr[emont]44. There's a lot of skill in making a tale with good grace. He [gets] well at embroidering a tale.

You whose naive expression

A sçu divèrtir tant de foi[s]

Dans des contes charmans

le plus puißant des Rois.

Mlle L'Héritiér.

Une morale nuë apporte l'ennui :

The tale passes the precept along with it.

La Font[aine]45.

TALE, sometimes said of fabulous & invented things. Ficta, commentitia, narratio. It's a tale made for fun, a tale for laughs.

CONTE, se dit aussi de tous les discours de néant & qu'on méprise, qui ne sont fondez en aucune apparence de vérité, ou de raison. Fabula. This impèrtinent has come to me to make a foolish conte. I make no mention of all he promises, they're all contes, contes in the air.

CONTE, se dit provèrbialement en ces phrâses : Ce sont des contes de vieilles, dont on amuse les enfans, des contes à dormir debout, de peau d'âne, de la cigogne, de ma mère l'Oye. Un conte violet, un conte jaûne, un conte bleu, & c46. " (Dictionnaire de Trévoux, ed. 1738-1742)

The first thing that strikes you on reading this article are the introductory references to the short story writers of the Renaissance and early 17th century. The tale does not yet refer to the popular, or folk, tale that we today assign to children's literature : the only author of /// fairy tales quoted is Mlle l'Héritier, but in a poem. At the very end of the article, "old wives' tales, with which children are amused " are mentioned, i.e., with which they are deceived. The marvellous, the enchantment of the tale only comes into play at a later stage, this character of the tale is not seen as an essential and primary feature the enunciative framework of the tale can therefore reasonably be identified with that of the Decameron and the Heptameron.

The tale, on the other hand, is not clearly dissociated from the fable. It is the preface to La Fontaine's Fables and not Contes47 that is quoted, and the reference to Aesop, directly and then indirectly via Fontenelle's dialogue, is symptomatic of this indifferentiation. The question of the morality of the tale is thus brought to the fore as an essential issue, and is the focus of the Trévoux article's main addition to Furetière48 : the tale envelops the moral lesson, the truth in a pleasant fable, there's a background and an envelope, the gratuitousness, the facetiousness, the unbridled fantasy of the tale are justified by this serious content that it introduces without seeming to and as if by playing. The tale is a pedagogy. This is what Fontenelle had Homer say in his dialogue with Aesop it's what La Fontaine was already asserting in the preamble to the fable of The Shepherd and the Lion.

.But this moral purpose of the tale is beaten back by an all-powerful pleasure principle : the great aging mind, i.e. one that has come back from everything, without hope or ideal, enjoys tales for their brevity (La Fontaine) and the pleasure they bring (Mlle L'Héritier), for the pleasure of brevity and improvisation they concentrate (a tale is " brode "), i.e. for the form of the spirit they welcome and convey. This is the " piquant " of the tale (Saint-Évremont) : the tale produces the points, the projections of the witz, of the wit.

There is thus a tension in the tale between the fable, fabula, which aims for a meaning, a morality, and the story, narratio, which aims for the trait, the witticism, at the risk of nonsense and absurdity. It is in this sense that we must understand the denomination of Zadig as well as L'Ingénu : oriental history, true history, these are stories, i.e. pure fantasy, " true " understood, of course, by antiphrase. The entire end of the Trévoux article directs the tale towards this light, gratuitous pleasure of the mind, to the detriment of the serious moral message that the fable is supposed to convey. The tale is no more than a variation of colors. The conte violet comes from Scarron, who undoubtedly invented the expression for the rhyme :

At once Iris sets sail

And, leaving all her colors,

Of which, when the authors make theirs

(That is to say, when they cheer up,

And of strong berries49 pay us),

Make us a hundred purple tales,

Children of their wispy spirits... (Le Virgile travesti, book V)

The expression " conte jaune " is undoubtedly forged on " toile jaune ", the large household cloth, whose raw fabric has not been bleached and primed. As for the " contes bleus ", they're probably shorthand for the tales of the blue library, the popular books that have been printed in Troyes since the early 17th century.

.We can now better define this " something " of the tale against which Voltaire measures himself, with which he establishes a complex relationship of appropriation, detachment, overcoming. This something is the very spirit of the tale, its witz, what brings it together, concentrates it in the witticism, by which a meaning, a moral is promised to us, waved like a red rag, and by which we /// are seduced, deceived, disappointed: it was all color. The story does not envelop an object of fable, there is no morality in the end. But that's not to say that the story is absolutely objectless. In the absence of an object, Voltaire produces " something " : this something, which supplants the object of the fable, we call the spirit of the Voltairian tale.

These stories are not tales : they resolve themselves neither in the symbolic institution of a morality nor in the imaginary color of a gratuitous fantasy. Nor do they oscillate between one and the other: in contrast to the tension inherent in fairy tales, they transcend into reality. As we have seen from our analysis of the first chapter of Candide, there are three terms at play here. These three terms are knotted together from an originary scene whose outline we must now sketch.

The mind and the real : one hundred stirrup leathers

At the end of the preface to Contes de Guillaume Vadé (1764), we read a tale, which Voltaire attributes to Jérôme Carré50, at the end of a conversation with frère Giroflée. Jérôme had complained about his baptismal names, associated with saints to whom he always found something to reproach. Brother Giroflée suggested various alternative names, but " with each saint he proposed, he asked for something for his convent51 ". Jerome then told him this tale :

" There was once a king of Spain who had promised to distribute considerable alms to all the inhabitants near Burgos52, who had been ruined by war : They came to the palace gates ; but the bailiffs would only let them in on condition that they would share with them. The good man Cardéro53 presented himself first to the monarch, threw himself at his feet, and said : Great king, I beg your royal highness to have each of us given a hundred strokes of stirrup leathers54. Here's a pleasant request says the king why are you making this prayer to me? It's because," says Cardéro, "your people absolutely want half of what you're going to give us. The king laughed loudly, and gave Cardéro a considerable gift. Hence the proverb that it's better to deal with God than with his saints55. "

The tale poses an enunciative framework that we recognize as constituting the topical site of the genre. In return for the promise of alms, the king organizes a parade before him of life stories, each destined to present itself as more unfortunate and pitiful than the last. It's the parade of travelers before Candide and Cunégonde as they cross the Atlantic ; it's the selection at the end of which Candide chooses Martin as his companion for his journey home it's the supper of the fallen kings in Venice.

.Yet, as will be the case at the beginning of L'Ingénu, this enunciative framework is disappointed : old Cardéro doesn't recount his misfortunes, doesn't even ask for money and succor, but the whip for all solicitors. Not just any whip giving stirrup leathers is the punishment a master gives his valet, a degrading punishment that returns the valet to his subordinate condition56. The pattern is as follows the valet has incorrectly attached the stirrups to the saddle, his master rips off the stirrup leathers and beats the valet with them.

Cardéro's request is absurd : its absurdity constitutes the point of the witticism. To denounce the corruption of the king's guards, the good man is /// ready to give up the promised alms, and calls down humiliation and punishment on himself and his fellow sufferers. The absurdity of the request should make us laugh, and through laughter defuse the reality of its content. It's not a real request, it's a facade to mean something other than what's being said. The good guy isn't in a position, or doesn't feel he has the quality and position, to state outright what is not a request, but rather a complaint, or even indignation.

The line, the point therefore comprises, behind the brilliant façade, a contained aggression, this is the thesis developed by Freud57. Cardéro's bon mot is a political accusation. But this accusation is somehow dodged in " pleasant request ". " Plaisante " is ambiguous, either if we take it literally, that the request is basically just a buffoonery that makes the king laugh gratuitously, or if the adjective is to be understood antiphrastically : this request is no pleasure at all, it implies that there's a big problem, it clearly implies something. The request is therefore both pleasant and unpleasant, the hallmark of a witticism.

Finally, this whole story is brought in by Voltaire following a long development on the first names of Jérôme Carré, who himself unexpectedly comes to substitute himself for Guillaume Vadé as the author of the tales for which this is the preface, Guillaume Vadé himself being a nominee of Voltaire. The moral of the tale is " that it is better to deal with God than with his saints ", with the king than with his bailiffs. In other words, all names are corrupt : there is only one name, the one we must not utter in vain, the empty name of God.

The only real name is Voltaire's, but Voltaire has no name : Voltaire is an anagram, his particle a dummy. The terrible scene with which Voltaire began his writing career is repeated here. It's January 1726, in the dressing room of Adrienne Lecouvreur, one of the most prominent tragedians at the Comédie française. Voltaire is sparkling with wit, and the Chevalier de Rohan, of the oldest nobility, takes umbrage at the success of his rival, who is merely a parvenu. - Voltaire ? Arouet ? Finally, do you have a name ? And Voltaire replies, scathingly: Voltaire ? I start with my name, and you finish with yours. A few days later, Voltaire dined at Sully's. A servant took him downstairs. In the street, he is beaten by the Chevalier's henchmen, who watch from a carriage. Mortified, Voltaire takes fencing lessons to challenge the Chevalier to a duel. On April 17, he was arrested and put in the Bastille. On May 5, he is in Calais, bound for exile in England.

The stirrup leathers are the caning inflicted by Rohan the name is the stake in the caning the mind is Voltaire's weapon, his strength and weakness too. Cardéro's tale gives this founding scene the form and value of the primitive scene of the Voltairean tale. At play here is the fundamental form of the site, where the accumulation of misfortunes is summoned, of the circumstances, of the trait that disorganizes this accumulation, and of the determination of the action.

.Notes

is a ...conte written by Diderot in 1772, recounting two unhappy passions, that of Tanié for the venal Mme Reymer, and that of Mlle de la Chaux for the inconstant Gardeil.ROMANS | ET CONTES | DE | M. DE VOLTAIRE. | [Chain] | TOME PREMIER [TROISIÈME]. | [Vignette portant la devise : Nuper sub modio nunc super, naguère sous le busseau, maintenant au-dessus] | A BOUILLON, | AUX DÉPENS DE LA SOCIÉTÉ TYPOGRAPHIQUE. | [Guirlande] | M. DCC. LXXVIII. See Bnf, Rés P-Y2-1809 (1 to 3).

These texts are : " Contes arabes et /// indiens ", taken from the Arabic article in the Questions sur l'Encyclopédie and " Contes en vers ", which take up the Contes de Guillaume Vadé, published by Cramer in Geneva in 1764 and regularly republished since.

This is volume XVII of the Collection complette des Œuvres de M. de Voltaire, Genève, Cramer, 1768-1796, 45 vol. in-4°.

Nicolas-Claude Thiériot, Voltaire's childhood friend and literary correspondent to the King of Prussia. Voltaire and Thiériot had been placed together as clerks to the prosecutor Alain.

Joseph de Guignes's little Histoire des Huns, a 20-page pamphlet published by Coignard in 1751, had become a Histoire générale des Huns in 4, then 5 volumes, by Desaint et Saillant, in 1756, then in 1757-1758.

See Candide, chap. 25, p. 119-125.

Joseph Omer Joly de Fleury, avocat général at the Parlement de Paris, a bitter enemy of the Philosophes, had just obtained, in February, the banning of the Encyclopédie and the Poème sur la loi naturelle. But it was also he who, in 1762, was behind the decree of the Parlement de Paris seizing Jesuit property and closing their colleges.

The Parlement de Paris was a group of jurisdictions, or chambers, each with specific competencies and dealing with a certain type of case. The Grand'Chambre was the main chamber, which heard appeals from lower courts. The Parliament sat " toutes chambres assemblées " for the most important cases.

See Candide, chap. 16, p. 80-84.

Marie-Louise Mignot, niece of Voltaire, married against the advice of her uncle Nicolas-Charles Denis in 1738. She became " Madame Denis ", her pen name. Her husband died in 1744. Her affair with Voltaire began in 1745, was interrupted when Voltaire left for Potsdam and the court of Frederick II, and resumed in 1755 at Les Délices. Voltaire drove Madame Denis away in 1768, and they reconciled shortly after.

" In general & in discourse, we call all fabulous or implausible stories, fictions of Romans. Fabulosæ fictæ narrationes. It is even said of an extraordinary tale that is made in company, Voilà un Roman. It's a Roman avanture, a Roman intrigue. She could have been talking about her Roman in the alleys [=in the bedroom of a Précieuse]. Pat. C'est-à-dire de ses chimères, de ses visions. " (Trévoux, art. Roman)

The reference to " real " in the modern sense of the term is exceptional for the time and deserves to be emphasized : the frame of reference for classical fiction is not the real, but the true, the quality of a ficiton is not to be realistic, but vraisemblable. In the 18th century, the word "realist" didn't at all have the meaning it has today. It referred to a branch of scholastic philosophy at the time of the Quarrel of the Universals (14th century): the realist philosophers were the school of Duns Scotus, opposed to William of Ockham and the Nominalists. For realists, universals (more or less : concepts) are realities that exist outside thought and imagination alone for nominalists, they are merely words, abstract categories.

Paris was surrounded by 57 octroi (customs) gates, where everything that entered was controlled. These barriers were wooden barracks, to be replaced by stone buildings in 1784, under the aegis of architect Claude Nicolas Ledoux. In January 1766, when the last volumes of the Encyclopédie were published, distribution was free in the provinces and abroad, but prohibited in Paris and Versailles. Parisian subscribers had to go to warehouses close to the octroi barriers on their way out of Paris: they then re-entered Paris with their copies at their own risk... Control was thus reinforced at the octroi barriers, causing, beyond the Encyclopédie, a general shortage of prohibited books.

Charles-Augustin de Ferriol d'Argental, nephew of Mme de Tencin, councillor at the Paris Parliament and then French ambassador to Parma and Piacenza from 1759 to 1788, friend of Voltaire, with whom he maintained an extensive correspondence.

The manufacture : the printing works, where books are made. The printing works were located on rue Saint-Jacques in the heart of Paris. Voltaire here jokingly refers to Paris as " chef-lieu de la manufacture " of the Encyclopédie. As distribution is forbidden in Paris, subscribers cannot collect their copies from rue Saint-Jacques, and are obliged to go " aux environs " to the warehouses set up beyond the octroi barriers. You then have to " deceive " the customs, passing through the barriers again to get back home into Paris.

Henri-Joseph Dulaurens, a brilliant student of the Jesuits in Douai, became a canon in 1727. His wit and erudition earned him the hatred of his colleagues. After the 1761 ruling against the Jesuits, he wrote a violent satire against them and went into exile in Holland. In 1766, he published a licentious novel, Le Compère Matthieu, ou les bigarrures de l'esprit humain, attributed to Voltaire. Dulaurens decided in 1767 to return to France : he was incarcerated in Mainz, for impiety. His head became disturbed, and he showed signs of delirium. He remained under house arrest until his death in 1793.

A first edition of L'Ingénu had appeared in July 1767. The title page read " L'INGÉNU, | HISTOIRE | VÉRITABLE, | Tirée des manuscrits du Père Quesnel. | [Fleuron] | A UTRECHT. | [Double filet] | 1767. ". The actual place of printing of this clandestine edition is undoubtedly Geneva, and the printing may have been the work of the Cramer brothers, with whom Voltaire worked regularly. The mention " Utrecht " for a book published without an author's name would make authorship by Dulaurens, who had been living in exile in Amsterdam since his publication of his Jésuitiques in 1761, almost plausible.

Tacit permission was a lighter form of censorship introduced in the early 18th century to allow the publication of books that the royal power did not wish to officially authorize. It is therefore an intermediate regime between clandestine publishing and " approbation et privilège du roi ". A Registre des /// permissions tacites was kept in the Archives of the Chambre syndicale de la Librairie et Imprimerie de Paris, and was handed over to the curators of manuscripts at the Bibliothèque nationale in 1801.

Étienne Noël Damilaville, a friend of Diderot's from 1760 onwards, let him take advantage of his postal franchise as first clerk at the office of the vingtième tax to route correspondence between the philosopher and his friend Sophie Volland. Damilaville subsequently provided Voltaire with the same services, notably during the Sirven affair in 1767. More radical than Voltaire on the religious question, Damilaville was an atheist. We owe him several important articles in the Encyclopédie, notably Population and Vingtième.

The adverb is a wit : Voltaire replies that he is not the author of L'Ingénu, he denies authorship. But he replies ingénument, which is normally understood as " naïvely, tout simplement ", but can also be read in context as " à la manière de L'Ingénu ", and even " à la manière de l'auteur L'Ingénu que je suis ". In other words, the adverb indirectly signs, in spite of everything and through the sleight of hand of the witticism, the authorship of the work Voltaire denies.

History is first understood in the noble sense of a narrative of the great genre : " Histoire, s. f. Récit fait avec art : description des choses comme elles sont par narration soutenuë & continuée, & véritable des faits les plus mémorable, & des actions les plus célébres. Historia. " (Trévoux, début de l'art. Histoire) But in the case of Zadig and L'Ingénu, this makes little sense, except as an antiphrase. Histoire also has a trivial meaning : " Histoire, is said proverbially in these phrases, he wants to have this wife, this tenant farm, this annuity : these are indeed histoires, these are many things together. We also say to those who make several faces before saying or doing something, Voilà bien des histoires, vous faites bien des façons. We say similarly, L'histoire dit, to say, C'est le bruit commun, on le conte ainsi. " (End of article) History is therefore also what we conte, a very neutral word to designate a narrative with no particular coloration.

On the " poetic regime " of art, which orders a hierarchy of genres, each comprising a system of binding prescriptions, in the same way that the social hierarchy politically organizes Ancien Régime inequality according to a system of states and constraints, see Jacques Rancière, Le Partage du sensibe. Esthétique et politique, La Fabrique, 2000, p. 28-31.

A comic, flippant abbreviation of Scheherazade. It's not clear how Voltaire would address Mme de Pompadour here, even indirectly and ironically, as suggested by J. Goldzink and S. Menant. Voltaire is writing a parodic dedication. At most, we can consider that the serious dedication whose counterpoint he takes here would be a dedication dedicated to Louis XV's favorite, protector of the arts.

It should read Uloug-beg, grandson of Tamerlan, prince then sultan of Samarkand in the first half of the 15th century. An astronomer and mathematician, he is praised by Voltaire in his Essai sur les mœurs : " The famous Ulugh-beg, who succeeded [Tamerlane], founded in Samarkand the first academy of sciences, had the earth measured, and took part in the composition of the astronomical tables which bore his name ; similar in this to King Alfonso X of Castile, who had preceded him by more than a hundred years. /// Today the greatness of Samarkand has fallen with the sciences, and this country, occupied by the Usbec Tartars, has once again become barbaric, perhaps to flourish again one day. " (Essai sur les mœurs, chap. 88 " DeTamerlan ", ed. René Pomeau, Garnier, 1990, t. I, p. 808-809)

The tales of the Thousand and One Nights are in fact much older : to the core formed in Baghdad in the 11th century is added an Egyptian popular background in the 13th century, the whole transforms until the 16th century. The publication in 1704 by Antoine Galland of the first translation of the Thousand and One Nights was so successful that it gave rise to all kinds of imitations, continuations, parodies and more or less fanciful translations of Oriental tales. The first was François Pétis de la Croix's Les Mille et un jours, contes persans traduits en français, published by the Widow Ricoeur in 5 volumes from 1710 to 1712. Is it a translation of the manuscript of the dervish Moclès, as Pétis de la Croix claims, who was indeed an orientalist and had just returned from a trip to the Ottoman Empire ? The French author borrows, rearranges and invents... In any case, following in Galland's footsteps, he creates a genre : Les Mille et un quarts d'heure, contes tartares (1733) and Les Mille et une heures, contes péruviens (1740) by Thomas Simon Gueullette were to follow; Les Mille et une faveurs, contes de cour tirés de l'ancien gaulois, by Chevalier de Mouhy (1740) ; Les Mille et une fadaises (1742) by Jacques Cazotte ; Les Mille et une folies, French tales (1771) by Pierre Jean-Baptiste Nougaret.

The expression " tales without reason " is to be related to the one used by Pococurante, a Venetian lord, in front of Candide about Ariosto. The great Virgil bores this aesthete who has come back from everything : " I prefer the Tasse and the sleepy tales of Ariosto. " (Candide, ed. J. Goldzink, GF, chap. XXV, p. 122)

Diderot recalls this in Le Rêve de D'Alembert (1769), when he calls the logical contradictions that D'Alembert claims to oppose his materialism " galimatias métaphysico-théologique " (DPV XVII 106).

Compare this with Sultana Sheraa in the dedicatory epistle of Zadig : " I do not kiss the dust of your feet, because you hardly walk on them, or walk on carpets from Iran or on roses. " (p. 23)

See, for example, the beginning of Gomberville's Polexandre (1638) : the handsome Turk's smashing arrival on his ship in port is met with the suicide of two men who throw themselves overboard from a cliff in front of him. Rescued, they must tell their story. Later, Polexandre asks Zelmatide to tell his story : " but since you intend to oblige all we are icy, don't deny us any more the connoissance of your fortune " (ed. 1637, I, 2, p. 235). The " Histoire de Zelmatide, heritier de l'empire des Yncas, et de la princesse Isatide ", told by his servant Garucca, begins p. 238.

The hundred short stories that make up Boccaccio's Decameron collection were composed in the mid-14th century. The stories range from saucy tales to love stories /// satire of monks. They had a European impact. Some of these short stories are imitated in La Fontaine's Contes en vers. Voltaire devotes a development to Boccaccio in chap. LXXXII of the Essai sur les mœurs : " Boccaccio fixed the Tuscan language : he is still the first model in prose for accuracy and purity of style, as well as for naturalness of narration. " (" Sciences et beaux-arts aux XIIIe et XIVe siècles ", in Essai sur les mœurs, ed. R. Pommeau, Garnier, t. I, p. 765.) A very fine edition in Italian was published in London (actually Paris) in 1757, in 5 volumes, illustrated by Gravelot. (See Utpictura18, series A0253.)

The Heptaméron was published posthumously in 1559. Marguerite de Navarre starts from a framework similar to that of the Decameron. The stories are contemporary French tales, or supposedly true stories. Some are, with a few transpositions, autobiographical. The stories are then discussed by the devisants : the question of their morality and exemplarity is now raised.

Antoine Le Métel d'Ouville, a writer of the first half of the 17th century, was the author of L'Élite des contes (1641, reissued 1669 and 1680) and then of Contes aux heures perdues (1643). He also translated Boccaccio. His tales had just been republished in 1732.

Pseudonym of Noël du Fail, 16th-century writer, author of Baliverneries d'Eutrapel (1548) and Contes et Discours d'Eutrapel (1585).

39Bonaventure des Périers, writer of the first half of the 16th century, author of Nouvelles récréations et joyeux devis de feu Bonaventure Des Périers, valet de chambre de la royne de Navarre, Lyon, 1558. Both Furetière and Trévoux take [De] Bonaventure and De[s] Périers to be two different authors.

Marguerite de Navarre, author of the Heptaméron (1559). In Furetière's dictionary, whose definition served as a model for Trévoux's, the article continues: " [les contes] sont agreables & divertissans. Il y a bien de l'adresse à faire un conte de bonne grace. Il entend bien à broder un conte. " The rest of the article up to the next sub-entry is new in Trévoux.

" The indulgence that has been shown to some of my fables gives me reason to hope for the same grace for this collection. It is not that one of the masters of our eloquence has disapproved of the idea of putting them in verse he has thought that their principal ornament is to have none that moreover the constraint of poetry, joined to the severity of our language, would embarrass me in many places, and banish from most of these stories brevity, which may well be called the soul of the tale, since without it it must necessarily languish. " (La Fontaine, preface to Fables choisies mises en vers, in Œuvres complètes, ed. J.-P. Collinet, Gallimard, Pléiade, 1991, t. I, p. 5)

Fontenelle, Nouveaux dialogues des morts, Paris, Blageart, 1683, Dialogue V, " Homer, Aesop. Sur les mystères des ouvrages d'Homère ", p. 53-54. Homère addresses Aesop.

This quotation from Boileau can be found at Esprit, where Voltaire /// has read it, and includes it in the Esprit article in Questions sur l'Encyclopédie, at the end of section II.

" Narratives and tales do not always succeed, one should not make them often, and when one is engaged in them, one should take care that they are not long, and that there is always something peculiar and piquant of which one is surprised. " (Saint Evremont, Nouvelles œuvres mêlées, t. 2, Paris, Claude Barbin, 1693, " Maximes pour l'usage de la vie ", p. 314)

La Fontaine, Fables, VI, 1, " Le pâtre et le lion ", v. 3-4.

These last three paragraphs are taken from Furetière, Trévoux merely adding the Latin translations.

Nouvelles en vers tirée[s] de Boccace et de l'Arioste par M. de L. F., Paris, Claude Barbin, 1665 (actually 1664) then Contes et nouvelles en vers de M. de La Fontaine, Paris, Claude Barbin, 1665 ; a second part appeared in 1666, a third in 1671, Nouveaux Contes in 1674 other tales were added in the 1685 edition, two more tales were published posthumously. The preface to the 1665 edition begins as follows: " I had resolved not to agree to the printing of these tales until after I could add those by Boccaccio which are most to my taste but some people have advised me to give what remains of these trifles now, so as not to dampen the curiosity to see them, which is still in its first flush. [...] I have only added new tales because it seemed to me that people were enjoying them. [...] Two main [objections] can be made to me: one, that this book is licentious; the other, that it does not spare the fair sex enough. As for the first, I say boldly that the nature of the tale so desired being an indispensable law, according to Horace, or rather according to reason and common sense, to conform to the things of which one writes. [...] People will say that I would have done better to suppress certain circumstances, or at least to disguise them. There was nothing easier ; but that would have weakened the tale, and robbed it of its grace. " (La Fontaine, Œuvres complètes, ed. J. P. Collinet, Gallimard, Pléiade, 1991, t. I, p. 555-6)

The first edition of Furetière's dictionary was published in The Hague, by A. and R. Leers, in 1690, two years after its author's death. Furetière had had to leave the Académie, whose dictionary was not progressing fast enough for his liking: hence the printing of the dictionary outside France. An expanded edition by Basnage and his team appeared in 1727, making Furetière the leading French dictionary. However, the revenues from this dictionary, published in Holland, went to Protestants...

Baie or Baye. " Baye. A deception one makes to divide oneself; blunder, lie, joke one makes at the expense of someone, to whom one gives great hopes, or to whom one frightens about something that is not true. Mendacium, fraus. To give someone a baye, to pay with a baye, verba dare. P. Thomassin notes that Italians say baia in the same sense, & he believes these words come from the Greek, βαιὸς, parvus, modicus, small, moderate : it even derives βαιὸς from bohon, a Hebrew word, meaning inanis, inane, inanitas, res inanis. " (Trévoux, p. 936)

Jérôme Carré was a pseudonym of Voltaire, who credited him with one of his comedies, Le Café ou l'Écossaise, performed in Paris in 1760 as a riposte to Palissot's Philosophes. Voltaire took particular aim at Fréron. The play was printed in Amsterdam in 1760, as being by Hume, the English philosopher...

For each saint, Giroflée mentions a convent named after him and pleads that Jerome, if he takes that name, should make a donation.

Burgos was the capital of Castile around 930, then capital of the unified kingdom of Castile and Leon from 1037 until the fall of Granada in 1492. The Spanish king in question could therefore have been Alfonso X, known as Alfonso the Wise (13th century).

This name is obscure. Did Voltaire coin it from cardo, thistle, to designate a peasant, a beggar ? In the apologue, Cardéro parodies Giroflée, whose name in Spanish is Hilario : Giroflée is a monk for laughs, a hilarious monk... There's a frère Giroflée in Candide, chap. XXIV, " De Paquette et de frère Giroflée ". Candide meets this young theatin in Venice, he looks so cheerful and well (p. 116), yet he dreams of setting fire to his convent... (p. 118)

" Estrivière, s. f. Leather strap from which stirrups are suspended. [...] To give the étrivières. It's to chastise liverymen, to whip them with étrivières. We also say that a man has let himself be given étrivières when he has suffered some affront, some indignity, when by his cowardice, he submits to whatever we want. In this sense, the word of étrivières has no singular. " (Trévoux)

The story is imitated from Straparola, 3e fable from his 7e night, in which the jester Cimaroste introduced to the Holy Father plays the role of Cardéro to the King of Spain.

Candide is beaten twice, but never in this manner. In chap. II, he is condemned by the Bulgarians " to pass thirty-six times through the chopsticks ", but pardoned after the 2ndth passage. During the autodafè in chap. VI, " Candide was spanked in cadence, while singing ". In /// Zadig, the battered wife blames Zadig for killing her Egyptian lover.

Freud, Le Mot d'esprit et sa relation à l'inconscient[1905], trans. Denis Messier, Gallimard, 1988, Folio, 1992, A. II., " La technique du mot d'esprit ", §6. Freud began by identifying the condensation peculiar to the mot d'esprit, whose model is the mot valise (" Rotschild treated me in a quite famillionnaire ", familiar and millionaire-like). He then shows how, from apparently logical reasoning, the witticism introduces a " détournement ", a displacement. It's the story of the salmon mayonnaise : the young man who eats the salmon with the money he's just borrowed displaces the lender's scandalized interrogation into a question of logic. Similarly, Heine's comparison of a rich man with the golden calf is diverted to the calf: no, he's older than a calf! Freud then returns to the salmon mayonnaise (p.115) behind the witticism, Freud detects a " cynical remark ", which constitutes the " sense in the nonsense " (§7, p.123) of the witticism. There's a kind of " retour à l'envoi " (§9, p. 142), or a " figuration par le contraire " (§10, p.144) Thus, from the " technique " of the mot d'esprit, based on the grammar of the unconscious (condensation, displacement), Freud moves on to its " tendencies " : the mot d'esprit may be, or appear to be, gratuitous but it is essentially tendentious when it " risks encountering people who would not have liked to hear it " (A. III. §1, p.177). Then " the nonsense contained in the witticism replaces the mockery and criticism contained in the thought behind the witticism " (§3, p.205) ; " the objects of the attack launched by a witticism may just as well be institutions, persons insofar as they are the representatives of these same institutions, moral or religious rules, conceptions of life, all things that enjoy such consideration that the objection to them cannot appear otherwise than under the mask of a witticism, and which is that of a witticism covered with a facade " (p.208).

In La Défense de mon oncle, Voltaire defends his Philosophie de l'histoire, written as an introduction to the Essai sur les mœurs, against one of his opponents, Larcher, author of a Supplément à la Philosophie de l'histoire. In it, the author of La Philosophie de l'histoire is reputed to call himself Abbé Bazin, and his nephew is supposed to speak out to avenge the memory of his late uncle.

, ed. J. Goldzink, Pocket, p. 24.

, p. 37-38.

, ed. J. Goldzink, GF, p. 44.

What can we learn from this ? That La Fontaine has two models, Boccaccio and Ariosto, both Italian, both modern. The tale is modern and Italian, as opposed to the fable, which comes from Aesop and is ancient and Greek. Tales are not serious they are " bagatelles ", " licentious " tales, whose primary aim is " to please ". The tale is graceful : it's a matter of " taste ", of " common sense ", which can't stand anything " disguised ".

The Jesuits therefore decided to publish a rival dictionary, in the town of Trévoux : Trévoux, capital of the principality of Dombes (now in the department of Ain), then benefited from a privilege allowing printing without requesting the King's Approval and Privilege, which the Jesuits found too favorable to the Jansenists. The base /// of Trévoux's dictionary is the Furetière, whose nomenclature and even article content the Jesuits adopted, sometimes augmenting or re-Catholicizing as they saw fit. The first edition of Trévoux dates from 1704, the last from 1771, and the place of publication varied according to political circumstances. The edition we use for the course is the CNTRL online edition (Isabelle Turcan), published in Nancy by Pierre Antoine in 1740.

///Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Le conte et le roman », Voltaire, l'esprit des contes, cours d'agrégation donné à l'université d'Aix-Marseille, 2019-2020

Voltaire

Archive mise à jour depuis 2008

Voltaire

L'esprit des contes

Voltaire, l'esprit des contes

Le conte et le roman

L'héroïsme de l'esprit

Le mot et l'événement

Différence et globalisation

Le Dictionnaire philosophique

Introduction au Dictionnaire philosophique

Voltaire et les Juifs

L'anecdote voltairienne

L'ironie voltairienne

Dialogue et dialogisme dans le Dictionnaire philosophique

Les choses contre les mots

Le cannibalisme idéologique de Voltaire dans le Dictionnaire philosophique

La violence et la loi