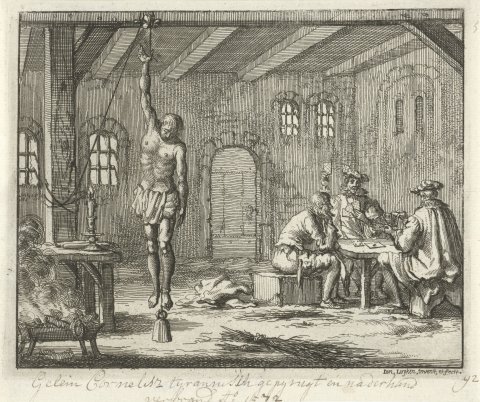

Gelijn Cornelis tortured in Breda, 1572. Luyken, Théâtre des Martyrs, Leiden, Pierre Van der Aa, 1685

From the time of its splendor, the educational institution of the humanities considered and presented Voltaire's Dictionnaire philosophique as a major monument to the intellectual adventure of the Enlightenment, as the cornerstone of the edifice of rationality and tolerance that the eighteenth century would have bequeathed to us. This place of honor in a system of cultural references that is now falling into disuse has dealt a mortal blow to the text, which is now, so to speak, illegible. The apostle of human rights, freedom of conscience and the secular state is basically boring and smells of mothballs.

The aim of this article is to restore the Dictionnaire to the difficult and unstable place where it had camped, on the troubling and anguished fringe of the Enlightenment. We will attempt to draw out the disquieting strangeness of a text that had come to be regarded as so familiar that it was no longer read. First of all, there is the violence of dogmatic speech, fanaticism, civil discord and mortification. The text doesn't just disapprove of this violence it nurtures it at its core, feeds on it in the fascinated field of its greedy gaze. But the Dictionnaire offers more than the thrill of bloody theatricality displaying its outbursts of inhumanity : in a deeper, more unexpected way, it articulates the violence it stages to the symbolic law it constitutes. From the old theological and metaphysical value system Voltaire rejects to the new one he elaborates, violence establishes the movement of a negative dialectic. It first triggers the symbolic deconstruction of a culture deemed dead, then releases the energy that builds a new world order. Thus, Voltaire's relationship to dead culture is not exactly defined as a critical relationship. If the work of the Dictionnaire does indeed consist, fundamentally and generically, in circumscribing and thereby criticizing the material of this culture, the detour and reuse of this material outside the text, on the pragmatic terrain of the campaign against the Infâme, inaugurates a new relationship of culture to reality.

First, we'll consider the object of the text, what, from article to article, it delivers to the reader's gaze. This object, as is normal in a dictionary, is language. We'll show how, by making language visible, Voltaire bends it to a deconstructive dynamic of unintelligibility and violence. We'll then turn to the poetic practice of text, that is, the relationship to language no longer as an object, but as an instrument of textual strategy. We'll then see how Voltaire recasts symbolic law in the abyss constituted by the nonsense of the old language.

" In us impotence, and before us an abyss " : violence as a supplement to law

Voltaire's use of language in the Dictionnaire philosophique is astonishing few dictionaries have mocked it more few have used it more theatrically. For the language that provides the words on which the Dictionnaire is about to dissert is not our language. Voltaire regards it with a certain distance as a fascinating and dangerous zoological object, as exotic material in which one does not circulate without damage.

From nonsense to outburst

The Arius article begins by posing " an incomprehensible question ", that of the nature of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit :

" I certainly don't understand it ; no one ever has, and that's the reason why /// which we slit each other's throats. We sophisticated, we quibbled, we hated each other, we excommunicated each other among Christians for some of these dogmas inaccessible to the human mind " (p. 34)1.

Language erupts in the investigator's face as incomprehensible violence. From this verbal derangement to hatred, destructive splitting and death, a necessary chain of events emerges, a system of delirious causality that needs to be broken, or more precisely circumscribed by the Dictionary, to be designated as an unintelligible and abject object with the ironic distance of an outside, critical, protected gaze.

In the fourth interview of the Chinese Catechism, Prince Kou, about to accede to the empire, confides to Cu-Su, a disciple of Confutzée :

" I am very fond of making prayers, I especially want them not to be ridiculous ; for when I have cried out that "the mountain of Chang-ti is a fat mountain, and that one should not look at fat mountains" ; when I have made the sun flee and the moon dry, will this galimatias be pleasing to the Supreme Being, useful to my subjects and to myself ? Above all, I cannot suffer the insanity of the sects that surround us." " (P. 76.)

Sophisticated discourse on the nature of God or ritual formula on Chang-ti Mountain, the object of the Dictionnaire is always the same it is the theological discourse and, more generally, the " galimatias " on which the symbolic order of the world is based that is targeted. Note here the same sequence as in the Arius article, from " galimatias " to " dementia ", from unintelligible language to its violent overflow, manifested, in Kou's discourse, by the edifying tortures that the bonzes inflict on themselves. These " mortifications that frighten nature ", fasting, carcans, nails driven into the thighs, this " popular disease so extravagant and so dangerous " (p.77) designate ideological discourse both as a sado-masochistic mise-en-scène offered to the voyeuristic and amused satisfaction of the reader, and as propagation, as contamination that threatens at any moment to include him discourse is an extravagant disease, a disease that literally spreads outside. Voyeuristic enjoyment can only develop thanks to this threatening reverse side of pleasure, this ceaselessly incurred risk of catching the disease, of being caught up by it.

This illness of the symbolic order, which is corrupted in the imaginary of an incomprehensible discourse, first manifests itself in fasting : " Some deprive themselves all their lives of the most wholesome foods, as if God could only be pleased by a bad diet " (ibid.). Not to eat is to frighten nature, i.e. to break with it and exclude oneself from it. Quite significantly, Cu-su opposes these mortifications, which enclose the delirium of language in an unnatural consummation, " that spirit of tolerance, that virtue so respectable, which is to souls what permission to eat is to bodies " (ibid.). To eat is to participate in the natural order, to enter into the tolerant neutrality of a desemantised real.

A dangerous fascination

The disjunction that then seems to appear between the destructive jouissance triggered by the mouth that speaks and the moderate satisfaction provided by the mouth that eats is, however, only apparent. From one to the other, the slope is slippery, the degradation irresistible. Voltaire's theological discourse is obsessively associated with food. In Le Catéchisme du curé, for example, Théotime describes to Ariston his way of " preaching to country folk " :

" I will always speak of morals, and never of controversy ; God forbid that I should delve into concomitant grace, the efficacious grace to which we /// resists, the sufficiency that is not enough ; to examine whether the angels who ate with Abraham and with Lot had a body, or whether they pretended to eat. There are a thousand things my audience would not hear, nor I either. " (P. 87.)

Ergotage, galimatias, controversy, theological discourse always manifests itself as incomprehensible plethora, as inflation of "a thousand things" that no one hears. It is not opposed to, but rather corresponds to, the image of manducation. The formidable machine of theological language constitutes its own world, impervious to the reality represented here by eating: between speech and eating, between angels and their meal, there is indeed an abyss. But this abyss is the same one that separates the soul from the body, the abyss of unintelligible questions into which language rushes. The angels' meal does not represent, but on the contrary transgresses the disjunction between the order of language, in which the biblical narrative is inscribed, and the natural order, of which food should be the exemplary figure. This food, impossible and disturbing, becomes the very image of the unintelligibility of discourse. Cut off from reality, language can only develop contradictions: we resist efficacious grace, which if it were efficacious would have to be irresistible; sufficient grace is not enough. From these contradictions, we move on to the confusion of the real and the symbolic, imagined by the angels' meal.

This confusion affects not only theological discourse, but the symbolic model par excellence constituted for our culture by the language of the ancients. In the article Ciel des anciens, Voltaire in fact writes :

" The language of error is so familiar to men, that we still call our vapors, and the space from the earth to the moon, by the name of heaven [...]. If Homer had been asked to which heaven the soul of Sarpedon had gone, and where that of Hercules was, he would have been at a loss: he would have replied with harmonious verses. [...] But the ancients had no such finesse; their notions of physics were vague, uncertain and contradictory. Huge volumes have been written to find out what they thought on many questions of this kind. Four words would have sufficed : they didn't think not. " (Pp. 136-137.)

Language only begets language. Asked about one of his verses, Homer can only answer with other verses. As for Homer's commentaries, they develop into immense volumes, according to a disturbing process of proliferation that will never lead to the physical reality they claimed to attain. The music of language develops its dangerous song, independently of rational thought and its referents in nature.

Confusion of theological discourse or contagion, propagation of the verses of the ancients and the volumes they arouse, language constitutes a space of fascinating undifferentiation from which it is above all important to preserve oneself : " God forbid that I should deepen " exclaims the country parish priest, to ward off the temptation of a diabolical exercise in language. To go deeper is already to sink into confusion. The harmonious verses with which Homer eludes the answer to his exegete's questions on physics repeat the same fascinating indifferentiation; they produce the enjoyment of the sublime text without satisfying the desire to know. Like the song of the Sirens, they lose the investigator in the pure music of a language without beginning or end, in the ocean of immense volumes, only to send him back, by a fatal reversal, to the primitive neantization of desire, to the imaginary killing of the subject, to the merciless verdict of the four words that reduce the song to silence " they did not think ".

The undifferentiated and fascinating overflow of language then reveals its flip side, silence and death, otherwise manifested, in the Arius article or in the Catechism of the Chinese, the unleashing of the /// blind, destructive violence. The same movement of passage to the abyss is always repeated, of reversion of the fascinating enigmas of an incomprehensible and proliferating language into the killing of the subject, by its reduction to silence, to the emptiness of thought, or by the sado-masochistic staging of its torment.

In the article Matter, the dangerous leap is depicted in a particularly striking way. We know nothing about matter. But it is the object of a metaphysical discourse that, like the theological, like the poetic, oscillates from embarrassed silence to verbose overflow :

" So, either they're mute, or they talk a lot, which is equally suspect. [...] We weigh matter, we measure it, we break it down ; and, beyond these crude operations, if we want to take a step, we find within us impotence, and before us an abyss. [The system of eternal matter, like all systems, is fraught with difficulties. That of matter formed from nothing is no less incomprehensible. We must admit it, and not flatter ourselves that we can explain it philosophy cannot explain everything. How many incomprehensible things are we obliged to admit, even in geometry? Can we conceive of two lines that will always approach each other, and never meet ? " (Pp. 298-300.)

The step we would like to take from physical reality, which can be weighed, measured, broken down, to metaphysical discourse, which strings questions and answers together indefinitely to form incomprehensible systems, this step reveals " in us powerlessness, and before us an abyss ". The narcissistic plunge into the abyss of undifferentiation inhabited by the fascinating shimmer of "undifferentiated things " has as its corollary the impotence of the neantized subject. The exercise of a language incapable of " rendering reason " of the principles of matter, and unfolding indefinitely " from replica to replica " engulfs the subject caught in the reels of the desire to know, reducing it to a derealizing impotence. However, if language inevitably provokes the powerlessness of the subject it ensnares in its delirious questioning, this powerlessness guarantees the indefinite nature of its proliferation in a system of causality cut off from reality, and hence the formidable power of the dogmatic machine it constitutes. The powerlessness of language to articulate the "systems " it produces to an effective taxonomy of the world makes this language autonomous and, paradoxically, reinforces its effectiveness detached from reality, it encounters no obstacle it extravagates without restraint. Its imaginary power thus makes up for its symbolic impotence.

From supplement to surplus

A system of supplement then seems to be set up in Voltairean discourse, between the Church and its theology, or more generally between an ideological order in full dereliction and a language supposed to account for this order and violently failing to do so. The imaginary violence of language makes up for the symbolic bankruptcy of state religion. In the Dictionnaire philosophique, fanaticism and the spirit of systems are not simply the object of a principled condemnation. They constitute the fascinating supplement that rebalances a bankrupt representation of the world ; they are the violence, offered to the voyeuristic enjoyment of the reader, counterbalancing the errances and weaknesses of the law.

The point here is not to question the sincerity of Voltaire's commitment against fanaticism and intolerance, but to clearly mark the place they occupy in the fantastical work of Voltairean writing. Voltairean combat draws its tireless energy precisely from its coincidence with an imaginary device that places the archaic violence of the infamous mother at the fascinated center of a vast system of conjuring the abject object through writing. It's because the supplementing of the law by violence works with /// a formidable efficiency that writing can draw from it, in a negative way, a structural logic as powerful, as coherent, as implacable.

Take, for example, the seventh question in the article Religion :

" Why then do you speak insults to your brother when you preach to him a mysterious metaphysics ? It's because his common sense irritates your self-esteem. You have the pride to demand that your brother submit his intelligence to yours humiliated pride produces anger, which has no other source. A man wounded by twenty rifle shots in battle doesn't get angry. But a doctor wounded by the refusal of a suffrage becomes furious and implacable" (P.369.)

The Christian religion claims to base its legitimacy on a language of gentleness and love of neighbor that is contradicted by the very use of this language, for the purposes of proselytizing and, hence, violence on the conscience, if not the person, of others. This contradiction between the foundation and the effect of this language renders it unintelligible: the "mysterious metaphysics" becomes pure music of language, an autonomous system of signs with no referent. The symbolic ineffectiveness of this language is then compensated for by the physical violence its exercise provokes the preacher doctor's self-esteem becomes irritated, he utters insults, demands the unconditional alienation of the Other to his will. The furious, implacable violence provoked by the failure of language to persuade reasonably is then compared to the violence of war. Such is the unleashing of the imaginary imaginary not because it has the hazy unreality of pure phantasmagoria imaginary because it is situated at the most archaic sources of violence, when the Other is not so much destined for destruction (as in war) as for the denial of his otherness, for his crushing into the mold of the Same. The doctor's insults make up for the unintelligibility of theological discourse the dogma and religion he imposes through violence take the place of the symbolic law he should have persuaded through language.

The opposition that then emerges between a good and a bad use of language finds its political translation in the eighth question of the same article :

" Shouldn't we carefully distinguish between the religion of the State and the theological religion ? That of the State requires that imams keep registers of the circumcised, parish priests or pastors registers of the baptized ; that there be mosques, churches, temples, days consecrated to worship and rest, rites established by law that the ministers of these rites have consideration without power ; that they teach good morals to the people [...]. This is not the case with theological religion it is the source of all imaginable foolishness and unrest it is the mother of fanaticism and civil discord it is the enemy of the human race. " (P. 369.)

The language of state religion is taxonomic : by listing, classifying, ordering the population in a register of births, marriages and deaths, it assigns it a symbolic constitution, it relates it to an ideological grid of social states this grid is translated into the organization of space and time by the visible and concerted distribution of sacred and profane places, working days and holidays. The "rites established by law " represent and enshrine this taxonomy of the world, under the control of a law that is supposed to protect them from all excesses. By depriving ministers of religion of all political power and confining their discourse to the private sphere of good morals, the law locks the religious exercise of language : the taxonomy it unfolds constrains it the order it legitimizes imposes silence on it.

In contrast, theological religion defines itself directly through its discourse, without the lock of a higher state law. No place, no /// no limit has been set. The language of theological religion, because it is not regulated by law, but proceeds from the most archaic imagination, produces only unintelligible noise " of all nonsense " only " troubles " or confusion of categories. It doesn't order the world, doesn't separate it into classes, species and nameable qualities, but invades it, overflows it. It is " the source " " the mother " " the enemy " of everything that underpins sociability. This perverse outpouring clearly designates itself as the fascinating and abject figure of the archaic mother.

The strangeness of the text lies in the articulation of these two systems of religion, the good state system on which Voltaire's conception of tolerance rests, and the bad theological system, in which language runs wild and gives rise to violence and anarchy. Formally, Voltaire " distinguishes " them as two antithetical and seemingly independent systems. Yet the state system appears as the Machiavellian recuperation of the theological system, as the channelling by law of the disordered power that this language unleashes. The remedy is in the evil : registers, festivals, monuments and rites have meaning and function only in relation to the " civil discord " that their taxonomy manages to conjure.

.Or, if the taxonomic language of state religion appears logically as the result of a domestication of the noise and fury that designate theological religion, the latter is described secondarily by Voltaire it is the ideologically terrible but poetically stimulating degradation that triggers the final anecdote of the Dalai Lama, absurdly debonair arbiter of two sects that tear each other apart while kissing his turd. The archaic overflowing power of this untamed language is presented at the culmination of the Voltairian writing process to crystallize what makes its specificity, the brio of a little tale, the tightness of a spiritual apologue whose meaning escapes and whose rhythm stuns.

The tale doesn't replace the lost taxonomy of language it exceeds it. Voltaire's theory of tolerance was sufficient to compensate for what the fascinated fall into the regressive language of fanaticism had deconstructed in the symbolic order Voltaire's writing adds the tale which, through the change of semiotic regime it operates, far from being reduced to an ornamental redundancy of the message of tolerance, opens the text to a radical detour of the symbolic constitution of the world. The absurd laughter of the Dalai Lama distributing his pierced chair in the midst of civil war is supposed to represent the theological anarchy and violence engendered by the establishment of a monopolistic dogma. Yet the gesture goes beyond allegory, for whom the choice of Fo over Sammonocodom was sufficiently meaningful. This gesture, which repeats the inaugural rite and provides the point of the story, causes it to deviate from its original aim, as if reality, with its vagaries and circumstantial excesses irreducible to the constitution of a meaning, provided the salt of the tale at its most comically successful. The laughter of the law establishes the sovereign casualness of history at the heart of the violence unleashed by this very law. The abyss is this reality that jumps out at us in the derisory abjectness of its fecal materiality.

.From materialist inclusion to devouring surplus : the poetic function of galimatias in the article Ame

Thus emerges an economy of Voltairian writing in direct relation to the object of the text : to the fascinated contemplation of the abject object that, in the form of theological, metaphysical or poetic discourse, constitutes the language that the Dictionnaire seeks to account for corresponds a practice of writing that draws its energy and fires its shots precisely from the incongruous juxtaposition of a trivial reality and an imaginary outburst, unleashed by the archaic violence of the deviant languages that the Dictionnaire comes to /// convene.

The unfolding of the Ame article is characteristic of the structural dynamics engendered by this juxtaposition.

The soul between gaze and language : circumscribing the field

The soul constitutes, in metaphysical logic, an essential articulation of the intelligible space of essences to the sensible space of matter. By deconstructing the soul, Voltaire turns the mediating notion into a leap into the unintelligible, isolates and regresses the logical tool into a fascinating and dangerous pre-object. Significantly, the article doesn't open on an object of speech, but on an impossible given-to-see:

" It would be a beautiful thing to see one's soul. Know thyself is an excellent precept, but it belongs only to God to put it into practice : what other but he can know his essence ? " (P. 7, 1st §.)

The Plotinian diversion2 of the Socratic precept into a narcissistic plunge into the abyss of a knowledge inaccessible to mortals inscribes from the outset the questioning of the notion of soul as a presumptuous demand of the mystic, as a transgression of the human measure that forbids us to equal ourselves with God. It's a good idea not to lean too far over this abyss of metaphysical discourse:

" We call soul that which animates. We know little more, thanks to the limitations of our intelligence. Three quarters of the human race go no further, and do not bother with the thinking being ; the other quarter seek ; no one has found nor will find. " (2nd §.)

The etymological definition turns into an aporia in the face of the space of unintelligibility circumscribed by the textual strategy of the Dictionary. Yet the " limits of our intelligence ", far from laying the critical groundwork for a Kantian separation of the respective fields of reason and faith, only establishes a prohibition where the logic of the article requires it to be transgressed : the dictionary should not open a heading to read that it is impossible to open it ; if it does, it is only to better mark the procedure of impediment constitutive of its approach, to signify the fascinating plunge into the mysterious, dangerously autonomous language of metaphysics.

Then we realize that the etymology here was not posed at random : " that which animates " defines the deep spring of the entire metaphysical language, of which the soul is but the exemplary figure. Animated by an irrepressible movement of overflow, metaphysical language is defined in the same way as the irrational, fascinated approach to it that is expressed in the article. Under cover of Voltairian irony, which clears us of our transgression, we cross the famous " boundaries ", we go further far, we embarrass ourselves of thinking being : this movement bogs us down, this deepening engulfs us.

Let us not be deceived by the dismissive invective to the " pauvre pédant ", which in 1764 became the " pauvre philosophe ". The ironic, distant second person traces the fascinated plunge into the abyss of language, and follows the movement of impossible self-contemplation announced at the beginning of the article :

." Poor philosopher, you see a plant vegetating, and you say vegetation, or even soul vegetative. You notice that bodies have and give movement, and you say force ; you see your hound learning his trade beneath you, and you shout instinct, soul sensitive you have combined ideas, and you say spirit.

But, please, what do you mean by these words ? " (3rd §.)

To the reality of nature, to the actions that " you see " or that " you notice " and whose verbs /// account for, is opposed by the artifice of italicized nouns, the scholastic reification of the real into empty categories that " tu dis "3, and soon that you " cries ", according to a process of necessary degradation in violence that is now familiar to us. The " ideal order " of saying and the " physical order " of seeing, to use Dumarsais' terms, are irremediably disjointed. The metaphysical object of the article is thus deconstructed, first by its fragmentation, its demultiplication into a series of objects, then by its reification, its derealization into signs of nothing, nomina nihili, names with no ideas4. The infernal spiral of delirious questioning is then set in motion:

" But, please, can't you hear these words ? This flower vegetates, but is there a real being called vegetation ? This body pushes another, but does it possess in itself a distinct being called force ? This dog brings you a partridge, but is there a being in it called instinct ? Wouldn't you laugh at a reasoner (had he been Alexander's tutor) who told you, All animals live, therefore there is in them a being, a substantial form which is life ? " (4th §.)

That which discourse names has no " real being ". Between the verbs that account for the phenomena of the world - vegetate, grow, report - and the nouns that assign them a place in a metaphysical order - vegetation, force, instinct - opens the abyss of an unthinkable and impossible articulation. Unlike verbs, the system constituted by the constellation of nouns functions as a pure system of language, without referents, and fails to define a taxonomy of the world. Aristotle, Alexander's preceptor, appears here as the exemplary figure of this taxonomic aim of language, and of the philosophical systematization that ensued in medieval nominalism. The article opened against Plato, whose Know Thyself was deviated into a narcissistic figuration of an impossible gaze the preamble ends against Aristotle the " reasoner ", whose grammatical method of classifying reality into " beings " and "substantial forms " turns into the most ridiculous galimatias. This framing is not accidental: it circumscribes the entire philosophical field as unreal, open to a fascinated gaze and a delirious language. The image that closes the preamble brings these two elements together:

" If a tulip could speak, and it said to you, My vegetation and I are two beings joined obviously together, wouldn't you laugh at the tulip ? " (5th §.)

If the tulip brings to mind the tulip lover that La Bruyère, at the beginning of " De la mode If the tulip is reminiscent of the tulip-lover whom La Bruyère, at the beginning of "De la mode ", fascinated all day long by the delicate iridescence of its corollas, this word for flower refers to the sophism of the ephemeral, which makes Fontenelle's rose say that no gardener in living memory has ever seen a rose die5. The deviant systematizations produced by language contaminate nature itself. It's no longer the philosopher looking at the tulip, it's the tulip itself that's delirious, continuing the work of splitting subjective reality from the scholastic essence of the world: the immediate unity of which the image of the tulip provides its admirer with sensible evidence is opposed by the division of the two beings reflected in its words, " my vegetation and I " while derision and mockery establish at another level, that of the enunciative frame, a distance that the fascinated gaze tended, on the contrary, to abolish. The split thus takes place on two levels: the split of the object, of the tulip that has become double, produces the split of the "double". /// of speech, delirious tulip speech and the reader's mockery of the tulip.

The impossible given-to-see of the opening Know Thyself had engendered the disjunction of the gaze seeing the plant and the speech naming vegetation in it. But this disjunction itself is further deconstructed and fragmented by the double scission staged by the tulip discourse. The epistemological field circumscribed here is only constituted in the vertigo of its crumbling.

Scholastic structuring of the text (first phase)

In fact, to the absolute disjunction of theological-metaphysical galimatias and natural reality that organizes the ideological strategy of the article corresponds, in the textual strategy, the repeated use of the second person, the author's interpellation of the " poor philosopher " (p.7), then of the scholars (" O scholars, I'm afraid you are as ignorant as Epicurus ", p. 8), and finally of humanity as a whole (" Prends garde, ô homme ! ", p. 9), which distances the deprecated discourse, not as an external, neutralized object (this would be the role of the third person : metaphysicians think that...), but as an obsessive representation to which the author is prey, as the hysterization of discourse.

For, though condemned and sidelined by ironic enunciation, the metaphysical proposition remains structuring : cut off from reality, deconstructed as an object, it nevertheless gives rhythm to the text and inhabits it. The four basic categories that scholastically justify the notion of soul - vegetation, force, instinct (or sensitive soul) and spirit - reappear periodically without much variation. They are first set out in italics in the third paragraph. The same italics are taken up again in the fourth paragraph, in the form of a repeated question : is there a being called vegetation, force, instinct ? The mind alone disappears, replaced by the Aristotelian " reasoner ". In the sixth paragraph, the statement of certainties cuts across the four categories, without the names :

" Let us first see what you know, and of what you are certain : that you walk with your feet that you digest with your stomach that you feel with your whole body, and think with your head. " (6th §.)

To walk is to have movement : the " poor philosopher " thus defined force. To digest is to perform the life-giving natural functions that constitute vegetation. To feel belongs to the sensitive soul to think, to the spirit. Voltaire has particularized, imagined, theatricalized unchanged notions between the real we're sure of and the discourse we're repulsed by, the gap is quite slim, a gap from the noun to its putting into verb, from the idea to its putting into image.

The abstract terms reappear, moreover, in the ninth paragraph, when the point is made that indivisibility is not exclusive to the soul, that it also concerns the attributes of matter :

The driving force of bodies is not a being composed of parts. Nor is the vegetation of organized bodies, their life, their instinct, beings apart, divisible ; you can no more cut in two the vegetation of a rose6, the life of a horse, the instinct of a dog, than you can cut in two a sensation, a negation, an affirmation. Your fine argument from the indivisibility of thought therefore proves nothing at all (Pp. 8-9.)

Force, vegetation and instinct return to the charge like a leitmotif, but have surreptitiously passed over to the other side, as attributes of matter and no longer as categories of the soul. However, this common indivisibility, which places them on the same level as thought, is no longer ridiculed as it was in the fourth paragraph: the metaphysical entity /// is abandoned, but the abstract property remains. It allows the scholastic categories of the soul to be included in the reality of matter.

Materialist twisting of the scholastic model (second phase)

This inclusion remains imperfect, however, since it concerns the first three categories to the exclusion of the fourth, thought or spirit. The second phase of the article will therefore consist in reducing this last opposition :

Now, tell me in good faith, is this power to feel and think the same as the one that makes you digest and walk ? You confess to me that it is not, for however much your understanding might say to your stomach : Digère, it will do nothing if it is ill in vain your immaterial being would order your feet to walk, they will remain there if they have gout. (P. 9, 11th §.)

The Catechisme du curé's meal of angels prompts us to note this new digestive reference, already appearing in the sixth paragraph as a pictorial substitute for vegetation (" tu digères par ton estomac ", p. 8). An opposition emerges not between doing and saying, but between bodily reality and the power of understanding. This is no longer a simple, external opposition, between the position of Enlightenment philosophers and that of reactionary theologians, but a more insidious opposition, internal to Enlightenment rationality, between the powers of the body and those of the mind. These two discordant powers governing man are first and foremost located in the soul they are " two souls quite embarrassed and quite unmasterly at home ". Such terminology masks the shift we've made. Situating the realities of the body and the impulses of the mind within the soul in a homogeneous manner reveals a deconstructed object, stripping the notion of soul of all meaning. Voltaire is at liberty to summon up Greek thought and its "nou", then jumble together the speculations of Plato, Epictetus, Leibniz, Tertullian, Gregory of Nyssa, Descartes, La Peyronie and Thomas Aquinas, all of whom touch on the articulation of soul and matter. After ridiculing the pineal gland and its dwelling in the corpus callosum, the text parodies this articulation by asking how " a soul whose leg " and arm have been cut off in different places, then reused by other beings in the cycle of nature, can be fully resurrected. This leg of the soul, this oxymoronic noun complement, achieves bodily inclusion by force, through ironic telescoping. Irony is the only way out of the delirious metaphysical babble, forcing an inclusion that reason refuses, performing through the repeated image of digestion what discursive strategy cannot, namely the recomposition of the metaphysical object into a purely material one. From the theological soul, we have passed to a soul of flesh, vegetables and blood.

A paradoxical modeling : cannibalism in Jewish law (third phase)

The third phase of the article concerns the absence of soul in Jewish tradition. This time it's an inclusion in the literal sense, as Voltaire takes up a text he had already published in the Correspondance littéraire of July 15, 1759, under the title " De l'antiquité du dogme de l'immortalité de l'âme "7. The quotations from Deuteronomy that he accumulates both delegitimize the notion of soul, which does not appear in the law, and deconstruct a law that does not include the notion of soul. But, more profoundly than the negative dialectic it enables, the reference to Deuteronomy continues the telescoping of the real and the symbolic that founded the irony of the legs of the soul by identifying God's justice with bodily violence. Paradoxically, this telescoping, this identification, refers to the cultural modernity of a materialistic representation of the world. Judaic law thus appears contradictory /// as the original model of Christian theology, which the article rejects, and as the anti-model of theism and temporal morality, which it constructs. This contradiction of the archaic model of Jewish law, which the textual strategy designates as an abject object where the abominable Other, where theological language finds its foundation, but which at the same time it recycles and hijacks into the cultural system of modernity, translates into a cannibalistic hysterization of discourse. The last quotation is revealing in this respect:

" And you shall eat the fruit of your womb, and the flesh of your sons and daughters, etc. " (P. 12 ; Deuteronomy, XXVIII, 53.)

The quote is accurate, but, taken out of context, it changes meaning. The biblical text prophesied the miseries of the people of Israel if they did not serve God an enemy nation would invade they would be besieged in their cities and, reduced to hunger, would come to devour each other. The evocation of anthropophagy, taken in isolation, leaves behind the dramatized realism of a biblical prophecy that accumulates images, to become a terrible statement of the law, a veritable symbolic anti-model. Ingestion, which recurs in the article for the fourth time, and here in its purest Voltairian fantastical form, manifests in violence and horror the process, characteristic of the Dictionnaire philosophique, of integrating symbolic otherness into the materialist body of the text. Theological discourse, which here unfolds unchecked in the absence of mediations, since the mediating object has been deconstructed, resorbs itself in its own devouring. Excessive, hysterized, and thereby neutralized in the textual strategy, it delivers symbolic power by imaging and demultiplying itself, but abdicates all relation to the signified and manifests its abdication in cannibalistic reference.

A disjunction then appears between the unintelligible unfolding of this language and the impossible given to see that constitutes it as an abject and fascinating object. The article opened with this foundational impossibility (" It would be a beautiful thing to see one's soul "), which is now authorized by a biblical guarantee :

It's a disjunction between the unintelligible unfolding of this language and the impossible given to see that constitutes it as an abject and fascinating object.

" Moses, the only true lawgiver of the world before ours, Moses, who spoke to God face to face and only saw him from behind, left men in profound ignorance about this great article. " (P. 14.)

Beyond Voltaire's clever exploitation of the minor inconsistencies in the biblical narrative, the illogic of a device in which the law as word is received face to face despite the impossibility of seeing God's face resonates here with the structural economy of the text, for which the language of symbolic law is at once the object of the indefinite questioning of the Dictionary and the fascinated prohibition of the metaphysical gaze.

Limits (fourth phase)

The fourth phase of the article has been augmented by two additions to the original 1759 essay, the first in the Varberg edition of 1765, the second in that of 1769. Voltaire asserts the need to suspend judgment, to limit the exercise of reason to that which touches on metaphysics. Formally, however, the movement of the text is identical to that of the two previous phases. Cicero, Locke, Gassendi, " all the early fathers of the Church " are summoned to endorse the limits Voltaire assigns to the exercise of reason. But here again, the perspective and purpose of the article contradict and transgress the limits it pretends to impose on itself. The God who endorses this pseudo-critique of reason is a ridiculous puppet whose prescriptions are worth what the Dalai Lama was handing out at the end of the article Religion. Voltaire purposely parodies the eloquence of a preacher and derisively accentuates the emphasis of his injunctions, hammered home at least four times :

" You are I don't know what, thinking and feeling, and when you would feel and think a hundred thousand million years, you would /// know no more by your own lights without the help of a God.

[...] O man ! this God has given thee understanding to conduct thyself well, and not to penetrate into the essence of the things which he hath created.

[...] No one knows what it is to be called spirit [...]. It is impossible for us narrow-minded beings to know whether our intelligence is substance or faculty.

[...] we ourselves know nothing of the Creator's secrets. Are you then gods who know everything ? We repeat to you that we can know the nature and destination of the soul only through revelation. " (Pp. 14-15.)

Inflationary repetition constitutes this limit in excess, identifies the measured wisdom of the Enlightenment with a precipitation towards the abyss. The work of writing then reveals what the mere consideration of the theoretical statement risks missing. The article thus ends, as it were, with an I know that I know nothing that parallels the impossible Know thyself yourself of the first paragraph. The Socratic precepts respond to each other, marking that the text has indeed traversed the philosophical and metaphysical space it had supposedly stricken as unintelligible.

Textual strategy and structural misunderstanding

The Ame article is based on the historical passage from the classical representation of the world to its modern deconstruction and recomposition. In the old system, language operated a taxonomic articulation between the reality of the world and its symbolic order8 : the notions on which man based his representation of the world were mediating notions. The soul articulated matter and thought in man angels made it possible " to place intermediary beings between the Divinity and us " (p.22) confession instituted the confessor as mediator between the sinner and the symbolic authority Voltaire vividly portrayed this mediation in the Jesuit Coton promising to throw himself between Henri IV and the regicide who had entrusted him with his project (p.148) ; this mediation becomes a scandalous interposition for Voltaire in the article Prêtre, while the article Superstition questions, indignant : " Et qu'est-il donc ce prêtre de Cybèle, cet eunuque errant qui vit de vos faiblesses, pour s'établir médiateur entre le Ciel et vous ? " (P. 395.) ; as for the chain of created beings, it established a " gradation of beings rising from the lightest atom to the Supreme Being " (p. 101) ; similarly, the chain of events " extends from one end of the universe to the other " (p. 104). A whole series of articles in the Dictionnaire take this ancient system of mediations as a basis from which to operate a work of ideological deconstruction.

In the new symbolic order, the disappearance of the old mediations is compensated for by a system of limits. These are the " bornes de l'esprit humain ", to which Voltaire also devotes an article. Language then loses its taxonomic and mediating function to become the site of all kinds of delirious excesses, from which it is advisable to protect oneself with prudent ejpoch;.

.But this historical passage underlying many articles in the Dictionnaire does not deliver its conscious structure. Indeed, first of all Voltaire figures the utopian model that his book and ideological campaign seek to promote with the features of the old system, idealized, restored to an imaginary and primitive efficiency. We saw in the article Religion how the state religion, by politically realizing Voltairean tolerance, restored the taxonomic power of its language. On the other hand, the ideological constitution of the languages of theology, metaphysics, literature, etc., has been the subject of much debate. /// is now perceived only in the degraded form of an unintelligible overflow, a kind of devouring superfluity of the work of reason. Yet - and this is the second aspect of the structural misrecognition that underpins Voltairean poetics - the article's textual strategy, far from excluding this rational surplus, this empty work of reason that metaphysics constitutes, incorporates it as a founding abyss, as a constitutive defection of reason. As we saw in the article Matière, to take a step into metaphysics is to find impotence within oneself. Through denial and the assertion of limits, Voltaire's writing constantly overcomes this step, which exposes it to precipitation into the abyss. The transition from physics to metaphysics frees language from any relation to reality, and delivers it as a gratuitous expense, as pure surplus, to ideological devouring. But designating the limit or crossing it is a whole :

[...] you treat the philosopher's humble doubt and submission like the wolf treated the lamb in Aesop's fables ;; you tell him : " You spoke ill of me last year, I must suck your blood. " (P. 15.)

This fifth figure of devouring, which almost closes the article Ame, joins the masochistic anthropophagy to which the intellectual is given over in the arena, at the end of the article Lettres, gens de lettres ou lettrés9. Whether or not he imposes limits on his reason, the disappearance of mediations exposes the Enlightenment propagandist to having his blood sucked by his opponents and, confusing the " submission of the philosopher " with the wisdom of philosophy, to identifying the limitation of discourse with the representation of the sacrificed discursor. " You spoke ill of me last year " represents, in its derisory futility, the tiny surplus of the lamb's discourse. For discourse is always excess even by a small amount, even for nothing, it exceeds the reality it represents, and always incurs the injunction to limit itself. Yet the real always catches up with what language exceeds, in order to eat it.

Voltaire's poetic logic manifests itself here in all its powerful modernity : the basic referent for structuring writing is not textual, or even linguistic it's reality. Discourse - the discourse of sophists, theologians and metaphysical speakers, but also, because it proceeds by mimeticism, negative dialectic and inclusion, Voltaire's own discourse - exceeds reality. Voltaire's textual strategy consists in confronting this verbose excess, this noise of slander, this uprooted signifier, and colliding it with reality, the most striking image of this collision being the image of devouring. The Voltairian text feeds on its excesses to return to reality, dramatizing it in its violent brutality it stages the wolf that lies in wait sooner or later it leads to its sucked blood.

The Voltairian poetics of the surplus, as we can see, is at the antipodes of the Derridean supplement, which, formally at least, it might appear to resemble. Unlike the supplement, the surplus does not re-establish a failing textual logic on the contrary, it eliminates it in favor of something else, in favor of that famous " signified outside text whose content could take place, could have taken place outside language, that is [...] outside writing in general ", or more simply of that hors-texte to which J.Derrida denies any structuring function for writing10. This signified, this hors-texte that devours writing, is already in the real, and is produced directly by it. This is the profound challenge of the deconstructive work of the Dictionnaire philosophique to abolish mediations, to establish the limits that discourse exceeds, to create an abyss of impotence at the heart of the text, is to prepare the advent of a new symbolic. /// outside language and mediation, is to open up the real to meaning. This heterodox real-symbolic that is at stake in Voltairian poetics, this cannibalistic telescoping of discourse and reality that legitimizes literature outside itself, opens writing to a radically modern practice : it founds engaged literature.

Recap

Analysis of the Ame article has enabled us to distinguish four phases in the transition from the old to the new ideological space. In the first phase, the object of the article, the mediating notion of soul identified with the four scholastic categories of vegetation, force, instinct and spirit, is deconstructed, thanks to a strategy of fragmentation and demultiplication. But, contradictory to this deconstruction, the obsessive repetition of categories and the widespread use of the second person hysterize the discourse delivered by the deconstructed object, constituting it as the structuring energy of the text.

The second phase of the article integrates the deconstructed object with the reality of matter, recomposing in parody a properly Voltairian object, a material soul with arms and legs. The falsely fortuitous use of the image of devouring is a symptom of the disappearance of mediation; the text confronts the symbolic directly with the real. In Voltaire's work, devouring always signifies this confrontation.

The third phase of the article, using the Judaic model, points to the paradox of Voltaire's ideological construction : as the foundation of theological discourse, the law of Leviticus and Deuteronomy is here reclaimed by Voltairean materialist argumentation, which thus overflows the boundaries it had assigned itself. This inclusion of the Judaic model in Voltairian textual strategy makes metaphysical discourse no longer an otherness to be combated by the Enlightenment, but a surplus of reason, a surpassing of the signifier. The new word, by incorporating the old symbolic law, designates the antagonistic discourse as surplus of power, as overflow.

Then comes the fourth phase, where the limiting injunction replaces the scholastic statement of mediations as structuring repetition. This limitation, this metaphysical " we know nothing ", designates the poetic foundation of Voltairian writing as textual emptiness, i.e. not as a failure of the signified in the text, but as a passage to the hors-texte, as a commitment to the real :

.

Philosophy does not take revenge ; it laughs in peace at your vain efforts ; it gently enlightens men, whom you want to dumb down to make them like you. (P.15.)

The use of the third person situates the remedy for metaphysical evil outside the direct dialogue on which the article is based. Philosophy, moreover, does not speak : it laughs and enlightens. The process of ingestion, which as we have seen constitutes Voltaire's own textual strategy, is blamed on the enemy, who is accused of reducing men to his own stupefaction, of incorporating them. The terrible anthropophagic dynamic of discourse is the same for everyone it is therefore outside of it, by laughing (with irony, which detaches discourse from the speaker) and by enlightening (with images, which confront discourse with reality) that philosophy paradoxically finds its victory. Irony and image are certainly textual effects; but they are the means by which the text signifies that its principle and logic lie elsewhere. Irony and imagery are figures of speech, and rhetoric knows how to account for them but these figures, instead of bringing the springs of language into play (as would the arrangement of a brilliant metaphor, or the cadenced flow of a period with epic breath), put language at a distance, showing it as an object into whose articulations we do not enter. When Voltaire sums up Saint Thomas in one obscure paragraph, concluding that he "has written two thousand pages of this force and of this /// clarté aussi est-il l'ange de l'école " (p. 10), we watch the metaphysical discourse snore as an object of irony, but we don't enter into its reading, into its true intellection. When he concludes with the fable of the wolf and the lamb, the image of sucked blood jumps out at us as an object to be looked at, it strikes us as a propaganda poster but the story of the fable is not given to us to read we don't enter into the reasons for the wolf and the lamb. Both the object of irony and the image of combat are indeed textual productions ; but they draw their force outside the text, in the connivance and movement of fighting action, as shared laughter, as a placard brandished to crush the Infamous.

Metaphysics or pederasty : figures of excess

This movement of destroying the mediating object to release conceptual material, de-systematizing it to the point of nonsense and thus constituting a floating verbal surplus, can be found throughout the Dictionnaire philosophique. The whole strategy of the Voltairean text then consists in literally incorporating this material and diverting it, thanks to a dialectic of limit (external, deconstructive) and lack (internal, foundational). This strategy is based on the presence, in counterpart to the abyss that the text opens up within it, of a structuring hors-texte.

Violence is the natural law of desire

In a field that seems totally foreign to theology and metaphysics, the article Amour nomme socratique obeys this same structural logic :

" How could it be that a vice, destructive of the human race, if it were general, that an infamous attack on nature, should nevertheless be so natural ? It seems to be the last degree of reflected corruption, and yet it is the ordinary share of those who have not yet had time to be corrupted. It has entered into brand-new hearts, which have as yet known neither ambition, nor fraud, nor the thirst for riches ; it is blind youth which, by an ill-discerned instinct, rushes into this disorder as it emerges from childhood. " (P. 18, 1st §.)

The same spiral of destructive violence is set in motion here, the same blindness marks the leap into the abyss. But above all, this violence is founded on the same logical contradiction that metaphysical or theological language triggers. It is both natural and unnatural it is the primitive mark of a desire that is still new, and the most corrupt expression of desire gone astray it lies at the foundation of man's constitution, and radically threatens that constitution. Jewish law, in the article Ame, played on the same swing from model to anti-model, from a lack that founded our culture and radically criticized it.

.Finally, Socratic love is defined as the overflow of amorous violence, which the previous article, describing in the form of a Lucretian pastiche the rutting of a horse, absolutely identified with what we would today rather call desire. This overflowing of a " penchant [...] generally much stronger in men than in women " "this force that nature begins to deploy " in the young males of our species, this " sang [...] allumé " find their symbolic translation in self-love, the foundation of social organization and the subject of the following article. Socratic love is thus the imaginary, destructive surplus of a fundamental mediating function, which Voltaire represents in the dual guise of desire and self-love. Beneath the scabrous exterior of pure libertine entertainment, the ideological stakes of the text remain unchanged.

The imaginary surplus of desire is reflected in the writing by recourse to an equally surplus textual practice, that of poetic quotation. The truncated reference to Ovid, resituated in its original context, takes on its full meaning :

" [ amorem / In teneros transferre mares ] citraque juventam / Ætatis breve ver et primos carpere flores. "

[ defer love to young males ] and gather the short spring and first flowers of that moment of life which precedes youth.

Voltaire has elided the direct message, retaining only the ornate periphrasis, the metaphorical detour, the verbal surplus that the symbolic ban has produced. But above all, the subject of these infinitives is none other than Orpheus, who, refusing to trade in women after the death of Eurydice, is said to have taught pederasty to the people of Thrace! For Voltaire, the absent figure of Orpheus marks the link between the verbal power embodied by the archetypal poet, and the corrupting derangement that this power inevitably triggers. Homosexual violence makes up for feminine lack, just as the overflow of language makes up for the failure of the symbolic order. To the " blind youth " corresponds the interdict of the gaze which strikes Orpheus and which he transgresses : the verbal excess is only constituted by this fascinated dazzlement.

.Pederasty and the writing of laws

The second part of the article raises the problem of the relationship of this violence of desire to the constitution of laws. As early as the second paragraph, Voltaire founds homosexual desire in nature : desire, stronger in men than in women (" It is a law that nature has established for all animals. "), demands immediate satisfaction that the other sex cannot provide. He is then mistaken about the object, thanks to the young boy's resemblance to a young girl : " nature misunderstands ".

Without insisting on the highly fanciful nature of such an explanation, we'll focus on Voltaire's transition from natural law to social law. For he finds the same founding contradiction Alcibiades was both a great politician and a famous pederast the legislator Solon wrote verses advocating pederasty Theodore de Bèze " made verses for the young Candide " before founding the Reformed Church Plutarch, an undisputed moral authority, demonstrates the superiority of love between men in one of his dialogues. As Voltaire excuses, refutes, and weakly exonerates, the picture is completed and enriched. The refutation then reveals its dual purpose: while it excludes pederasty from the law, it establishes it as an abject and, as it were, necessary foundation. It is in fact a matter of constituting pederasty as the first moment of the law, as an abject excess that the law comes to sublimate.

For the last examples are also the most beautiful. A young man's lovers are a " holy and warlike institution " ; the " troupe des amants ", a Theban regiment famous for its bravery but also for its morals, " is the most beautiful thing ancient discipline ever had ". Through Plutarch's mediation, homosexuality provides a heroic and exemplary social model. From the abject side of debauchery, we move on to the sublime side of aristocratic distinction. The textual strategy has made it possible, through a negative dialectic of refutation and denial, to include the abject and fascinating object of the article not only at the foundation of natural law, but at the shining pinnacle of ancient institution and mores, that is, of the legislative model par excellence.

Contradictions of Voltairian nature

The third part of the article seeks to erase this scandalous modeling by excluding pederasty from the law. But here again, we'll be wary of denials, and Sextus Empiricus saying " that pederasty was recommended by the laws of Persia " is perhaps as much an endorsement as an opponent. Be that as it may, Voltaire clearly states that pederasty /// legal is impossible because... unnatural!

" No, it is not in human nature to make a law that contradicts and outrages nature, a law that would annihilate the human race if observed to the letter. How many people have mistaken shameful customs tolerated in one country for the laws of the country ! " (P. 20.)

This reversal from what was asserted at the beginning of the article clearly marks the change of perspective : from an amused historical account, we gradually slide towards the universal foundations of the law for the Enlightenment ; from the circumscription of an abject object, an abyss of imaginary regression within the symbolic instance, we have moved on to a philosophical refoundation for which pederasty becomes tolerated use, a limited space of contained derangement, a marginal practice stripped of any founding function. But above all, from the first to the third part of the article, the nature invoked changes status: it was the phenomenal object of an observation that was intended to be scientific it becomes the regulating and normative instance of a symbolic order superior to the letter of the laws. The article closes with a petition of principle:

.

" Finally, I don't believe that there has ever been a policed nation that has made laws against morals. " (P. 21.)

Very curiously, " mores " come here to oppose " usages ", natural morality prohibits the natural practice of homosexuality. Bypassing the system of symbolic alienation on which the institutional power of laws is founded, morals become the symbolic principle directly in the real. This continuum from the real to the symbolic, from nature as the exercise of desire to nature as the legislating power of mores, here designates the structuring hors-texte, mores, that last word in the text which ultimately confers symbolic legitimacy on the reversal that characterizes the article.

Symbolic inclusion of poetic language, spectral marginalization of law

Or, just as in the article Ame the materialist reversal operated by the text was conveyed by the spectral presence of a scholastic taxonomy, of an unintelligible but structuring metaphysical language, so the article Amour nomme socratique bases its reversal on the absurd and delirious presence of a poetic language that inhabits it. Initially purely ornamental to a quotation from Ovid, poetry becomes the verbal surplus of the great legislators, Solon for politics, Bèze for religion, Plutarque for morality. This surplus then became autonomous, constituting the general sphere of culture. Poetic language, originally situated on the bangs of the laws, then reappears at the heart of the symbolic device:

" Octavian-Augustus, that debauched and cowardly murderer, who dared to exile Ovid, thought it very good that Virgil sang Alexis and that Horace made little odes for Ligurinus ; but the ancient law Scantinia, which forbade pederasty, still remained : the emperor Philip put it back into force, and drove out of Rome the little boys who did the trade. " (Last §, pp. 20-21.)

Ovid, who initially provided the poetic detour of a pretty quotation, reappears here, with the allusion to his exile, at the political and ideological heart of the cultural sphere. The light ornament of fine verse becomes a symbolic foundation, and if the poetic games of Solon and Bèze could easily be subtracted from what constitutes them as exemplary figures, the Bucolics with Alexis11, the Odes with Ligurinus12 lie at the foundation of classical culture. The marginal surplus of poetic language is reintroduced at the heart of the system. But this refoundation is a détournement culture marks its departure from the /// law and the deviance that underpins it does not abolish the sleeping interdict, the provisionally conjured ghost of lex Scantinia.

However, Emperor Philip pales in comparison to the great Augustus. This tolerated deviation that was the foundation of Roman culture, this conjured ghost that takes the place of law but effectively sidelines it, provides a vacant space at the heart of the symbolic device thus described, which morals, in the article's final sentence, come to occupy. Thus ends the inclusion of the real in the symbolic and reveals the role of nature as a structuring hors-texte.

So it's a far cry from anticlerical pantalonnades and protests of more or less good-natured tolerance that the unsettling modernity of Voltaire's Dictionnaire philosophique springs forth.

The representation of the world as violence - the physical violence wrought by fanaticism, the verbal violence of confronting dogmas, the violence of desire " not finding the natural object " of its satisfaction - bursts into the text as a principle of reality that fascinates and hollows out an abyss irreducible to Enlightenment reason. Yet this fascination with the abyss, while reminiscent of a certain contemporary literature of despondency and narcissistic withdrawal, still constitutes in Voltaire the first phase of a dynamic of ideological reversal, of the hijacking of models bequeathed by classical culture and their recycling in the committed movement of the Enlightenment.

.In denouncing the violence at the root of the law, Voltaire does not renounce the law, but rather draws out its dialectical nature the soul, like pederasty, are necessary errors the gap they designate between the nature from which they proceed and the nature they transgress founds the new symbolic game, the new articulation to reality of a classical culture threatened by scholastic or aestheticizing closure. Thus is born the modern figure of the engaged intellectual.

Article published in Littératures, n°32, Spring 1995

(Presses universitaires du Mirail), pp. 35-59

Notes

///References are to the edition by Raymond Naves, Garnier, 1967.

Voltaire could be parodying here a passage from the Enneads : " And human souls ? They see their images as in the mirror of Dyonisos, and from above they rush towards them. " (Trad. E. Bréhier, Les Belles Lettres, IV, 3, 12, 1-2.) On Plotinus' narcissistic disguise of the Platonic doctrine of knowledge, see J. Kristeva, Histoires d'amour, Denoël, 1983 ; Folio essais, 1985, pp. 134-139.

On the rhetorical stakes of this opposition, see Françoise Douay, " Les combats sémantiques de Voltaire : armes métalinguistiques et lexicographiques ", paper presented on October 5, 1994 at the Voltaire et ses combats conference. Indeed, Voltaire's taunts can be compared with Dumarsais's comments on alchemical treatises, in the chapter " Allégorie " of the treatise Des Tropes ou des différents sens : " The term matter general is merely an abstract idea that expresses nothing real, i.e. that exists outside our imagination. There is no general material in nature, from which art can make whatever it wants; in the same way, there is no general whiteness from which white objects can be formed. The idea of whiteness comes from the various white objects [...]. It is to pass from the ideal order to the physical order, to imagine another system" (Françoise Douay, Critiques, /// Flammarion, 1988, II, 12, p. 151.)

Françoise Douay, art. cit.

Les Caractères, Garnier, pp. 393-394 ; Entretien sur la pluralité des mondes, 5th evening, reprinted in Le Rêve de D'Alembert, Hermann edition of the complete works, t. XVII, p. 132.

The return of the tulip to the rose could confirm the borrowing from Fontenelle.

Dictionnaire philosophique, edited by Christiane Mervaud, op. cit., p. 304, n. 1.

On this subject, see Michel Foucault, Les Mots et les choses, Bibliothèque des sciences humaines, nrf, Gallimard, 1966, especially chap. IV.

" The man of letters [...] resembles flying fish : if he rises a little, the birds devour him if he dives, the fish eat him. Every public man pays a tribute to malignity but it is paid in denarii and honors. The man of letters pays the same tribute without conceiving ; he has descended for his pleasure into the arena, he has condemned himself to the beasts. " (Pp. 273-274.)

De la grammatologie, Minuit, 1967, p. 227.

The second Bucolica opens with these two verses : " Formosum pastor Corydon ardebat Alexim / delicias domini : nec quid speraret habebat " (the shepherd Corydon burned for the handsome Alexis, his master's beau : so he had nothing to look forward to).

The fourth book of the Odes devotes two poems to Ligurinus. Let's quote the end of ode I : " Nocturnis ego somniis / Jam captum teneo, jam volucrem sequor / te per gramina Martii / campi, te per aquas, dure, volubilis " (For me when I dream at night, I already hold you in my arms, I pursue you fluttering on the grass of the Field of Mars, and splitting, cruel, the waves of the water). As for ode X, it addresses the young man with one of those carpe diem that Ronsard will remember...

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « La violence et la loi, langages et poétique du Dictionnaire voltairien », Littérature, n° 32, printemps 1995, PUM, Toulouse, p. 35-59.

Voltaire

Archive mise à jour depuis 2008

Voltaire

L'esprit des contes

Voltaire, l'esprit des contes

Le conte et le roman

L'héroïsme de l'esprit

Le mot et l'événement

Différence et globalisation

Le Dictionnaire philosophique

Introduction au Dictionnaire philosophique

Voltaire et les Juifs

L'anecdote voltairienne

L'ironie voltairienne

Dialogue et dialogisme dans le Dictionnaire philosophique

Les choses contre les mots

Le cannibalisme idéologique de Voltaire dans le Dictionnaire philosophique

La violence et la loi