A Voltairean fascination

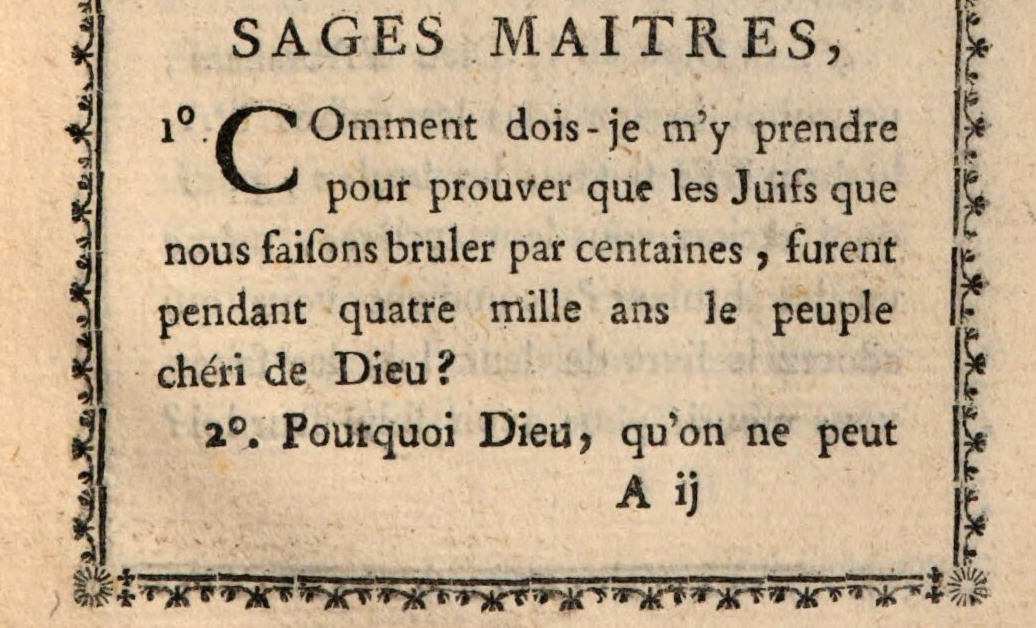

At the end of the Salomon article in the Dictionnaire philosophique, we can read :

" We abhor the Jews, and we want everything written by them and collected by us to bear the stamp of Divinity. There has never been a contradiction so palpable. " (P. 3601.)

What Voltaire poses here as a contradiction constitutes the fundamental framework from which the various, a priori rather disconcerting discourses Voltaire deploys on the Jews, before, during and after the Dictionnaire philosophique unfold.

How are we to read these texts ? What is this " nous " which asserts that " nous avons les Juifs en horreur " ? What, for Voltaire, is " les Juifs " ?

The Salomon article, which appeared in the first edition of 1764, was considerably reworked in the Varberg edition of 1765. The subject was then hot and central for Voltaire, who wrote, in chapter xxxvi of La Philosophie de l'histoire, in 1765 therefore :

" Our holy Church, which abhors the Jews, teaches us that the Jewish books were dictated by the Creator God and Father of all men ; I can form no doubt of this, nor allow myself even the slightest reasoning. " (Essai sur les mœurs, ed. R. Pomeau, Garnier, I, p. 129.)

This biting, ironic text from La Philosophie de l'histoire clarifies how we are to understand this " nous " and these " Juifs " that, obsessively, Voltaire arranges face to face.

We is " our holy Church " that is, the official, instituted collectivity to which Voltaire and his readers alike are supposed to belong ; but Voltairean writing aims precisely at the deconstruction of this " us ", first through ironic dissociation, then through indignation, abomination and revolt. The aim of the Voltairian performance is to insurrect us against this " nous ", to lead us to disassociate ourselves from it.

As for the " Jews " that " we " are supposed to " abhor ", Voltaire immediately substitutes " Jewish books ", i.e. essentially the Old Testament, against which he engages in fierce criticism. Voltaire's Jews are not, in this speech, the real, living Jews of his time : it's symbolic figures he's targeting, and targeting them essentially because biblical heroes, and even more so the texts that evoke them, form the foundation of the Christian institution.

Voltaire complacently, and insistently, underlines what appears to him to be a contradiction : " the Jewish books were dictated by the Creator God and father of all men " ; they are therefore sacred and, as such, escape critical examination, the test of methodical doubt, the exercise of reasoning, in a word the whole Cartesian heritage that the Enlightenment claims to be about.

It would be a mistake to reduce Voltaire's relationship to this Jewish sacredness of biblical texts to mere ironic reprobation. He spent too much time reading the Bible, first with Mme du Châtelet at Cirey2, then in the company of dom Calmet, until the /// publication of La Bible enfin expliquée in 1776. The Jews of the Bible fascinate Voltaire, and fascinate him in a contradictory relationship that is, indissolubly, one of admiration and horror. It is this relationship that we would like to study here, in an attempt to avoid the double pitfall of a sterile and anachronistic value judgment : it is indeed very easy to tax Voltaire with anti-Semitism, so revolting are some of his formulas, scandalized by their bad faith and injustice ; it is vain on the other hand to try to excuse or justify Voltaire by drawing up, in front of the anthology of his abominable formulas, the list, shorter moreover, of his testimonies of compassion or even admiration towards the Jewish people.

I. Evolution of Voltaire's relationship with the Jews

It seems more interesting, on the other hand, to consider the question of this relationship of Voltaire's with the " Jewish question " in diachrony, as a burning, central and decisive issue in Voltaire's discursive strategy, i.e. both poetic and ideological. Indeed, three phases can be distinguished in the 1760s.

Our fathers and our victims : a founding contradiction

The first, up to and including the publication of the Traité sur la tolérance in 1763, is the most moderate : indignant at the 1761 execution of the Jesuit Malagrida, wrongly or rightly implicated in the attack on the Portigal king, and with him of two Muslims and thirty-seven Jews, condemned in Lisbon by the Inquisition to the stake, Voltaire writes the Sermon from rabbi Akib3 and chapter ciii of the Essai sur les mœurs, which traces the situation of Jews in Europe since the Catholic Reconquest of Spain. We see the fundamental contradiction :

" Their famous rabbis Maimonides, Abrabanel, Aben-Esra, and others, had no problem telling Christians in their books : "We are your fathers, our scriptures are yours, our books are read in your churches, our hymns are sung there" ; they responded by plundering them, hunting them down, or having them hanged between two dogs in Spain and Portugal they took to burning them. Recent times have been more favorable to them, especially in Holland and England, where they enjoy their wealth, and all the rights of humanity, of which no one should be deprived. " (Essai sur les mœurs, ch. ciii ; 1761 ; II, 63.)

Voltaire contrasts filiation through texts with abomination in the real ; cultural, theological, ritual paternity with historical extermination. From the outset, however, we perceive in the virtuous discourse of the philosopher of tolerance the elements of an imaginary, properly pathological drift. From filiation through writing, we move on to filiation through the mouth (" our hymns are sung there "), which is the very mouth through which the Christian response is expressed (" they were answered ") : pillage, ignominious hanging, burning at the stake constitute this response and visually paint the picture as abomination, i.e. as secretion, horrifying ejection out of the mouth. The picture dehumanizes the Jews, who are curiously referred to in the third person, whereas the sentence was intended as a dialogue between " their famous rabbis " noble figures, and " Christians " reading the Bible and singing hymns. This beautiful dialogue is reduced to a face-to-face meeting between a " on " and its massacred victims.

The noble contradiction posed by the Essai sur les mœurs (" We are your fathers " / " on leur répondait en les pillant ") gradually goes to /// can be contaminated by this oral imaginary of abomination : Voltaire then displaces the contradiction within Jewish history and law itself.

Both tolerant and intolerant

In the Traité sur la tolérance, he makes the Jews the people who bear within themselves the universal contradiction of tolerance, which wants it to coexist indissolubly with its flip side, fanatical intolerance. The Jews as a tolerant people? Voltaire's statement was poorly received:

- "The Jews are a tolerant people ?

In a letter to D'Alembert dated February 13, 1764, about the Traité sur la tolérance, Voltaire responds to criticism of his portrayal of the Jews in the Traité sur la tolérance. Voltaire speaks of himself in the third person :

" The good man, author of the Tolerance, worked only with the advice of two very learned men4. You can imagine that he didn't quote Hebrew on his own. These two theologians agreed with him, to their astonishment, that this abominable people, who slaughtered, it is said, twenty-three thousand men for a calf5, and twenty-four thousand for a woman6, and so on., yet this same people gives the greatest examples of tolerance; it suffers in its bosom an accredited sect of people who believe neither in the immortality of the soul nor in angels. Find me on the rest of the earth a stronger proof of tolerance in a government. Yes, the Jews have been as indulgent as they have been barbarous there are a hundred striking examples : it is this enormous contradiction that needed to be developed, and it has never been developed except in this book. "

We see here how Voltaire works : he shifts the same problematic knot ; he goes for the maximum imaginary yield of the contradiction. Above all, he brings the central reversal, the revolt proper to the abomination, to the heart of the symbolic system, in the fictional world deployed by the Bible.

Voltairian discourse is not, strictly speaking, a discourse : it is a concatenation of images, a reversal and superimposition of affects. The Christian Bible, " this abominable people " of the Jews and the " strong proof of tolerantism " he gives amalgamate into a single systemic material, from which to nourish and drive the campaign against the infamous.

The device implemented, gradually elaborated by Voltaire, relies on an oral imaginary. We've seen how the campaign to crush the infamous was waged through texts themselves designated, by metonymic contagion, as Ecr l'Inf. The work incorporates the object it abominates and is constituted by it. The " abominable people " slit their victims' throats, but " suffer in their bosom " their adversaries. Both the throat and the breast refer to the passage, the oral reversal of the abomination. In this oral system, metonymy contaminates, corrupts the contradiction.The revered Bible was first opposed to the persecutions suffered the Bible now incorporates the persecutions, the Jews becoming the abominable flip side of the Bible, which polarizes into a " them " and an " us ".

D'Alembert, however, was not convinced, and spelled out the content of his " cruel criticisms " in his reply of February 22, 1764. Far from being outraged by a speech insulting the Jews, D'Alembert on the contrary criticizes him for a speech that is not exclusively insulting :

" The Jews, that beastly and ferocious scoundrel, expected only temporal rewards, the /// They were forbidden either to believe in, or to attack, the immortality of the soul, about which their charming law said nothing. This immortality was therefore a mere school opinion, on which their doctors were free to divide themselves, just as our venerable theologians divide themselves into Scotists, Thomists, Malebranchists, Descartists and other dreamers and chatterboxes. Does this mean that these gentlemen are tolerant, who would so willingly throw Calvinists, Anabaptists, Pietists, Spinosists and, above all, philosophers into the same fire, just as the Jews would have thrown Philistines, Jebusites, Amorites, Canaanites, etc., into a beautiful fire that the Pharisees would have lit on one side, and the Sadducees on the other? Jews and Christians, rabbis and Sorbonists, all these rascals agree to divide themselves on a few silly things but they all cry haro together on the first person who dares to make fun of the nonsense on which they agree. It is impiety not to agree that God is dressed in red, but they dispute among themselves whether stockings are the color of the habit. " (Letter from D'Alembert to Voltaire, Feb. 22, 1764.)

D'Alembert calls Voltaire to order, as it were, and tries to bring him back to what might be defined as the orthodoxy of doctrine. Unmoved by Voltaire's indulgence in horror stories, D'Alembert constructs a discourse against intolerance that is abstract, logical and non-dialectical. Jews are not both tolerant and intolerant they are " free to divide " on what is not important, " a simple school opinion "but their intransigence is absolute when it comes to " their charming law ". There's no contradiction here, just a hierarchy.

On the other hand, D'Alembert's Jews are not a special people, where all the issues and mechanisms of the fight against the Infamous would condense. They are fanatical sectarians like any others, " Jews and Christians, rabbis and Sorbonists ", today's Jews (" ces messieurs ") and the Jews of the Bible are confused in the same reprobation : they are " polissons ".

D'Alembert concludes with an image that is an allegorical image, purely logical, without affect : if, among sectarians, there is discussion about the color of God's stockings, all agree on his red garment. Therein lies the absurdity, therein the imbecilic intolerance that must be fought.

Voltairian imagination of abomination

But Voltaire didn't see things that way, and would never resign himself to this simple exercise in demonstration and discourse. For him, creative activity is an activity of enjoyment, both dirty and powerful, in which distancing oneself from the object of discourse is impossible. From 1764 onwards, Voltaire became increasingly biting and unjust against the Jews, but we must never forget that this dirtiness is always self-reflexive :

" This people must interest us, since we derive from them our religion, many even of our laws and usages, and that we are at heart only Jews with a foreskin. " (Essai sur les mœurs, ch. ciii, 1769 addition ; II, 61.)

" This people must interest us " : interesse, c'est être partie prenante, c'est en être. We are Jews (always this unassignable nous, in which we participate and from which we are summoned to divest ourselves), and this Jewishness in us is directly linked to the double, intimately corporeal question of sex and defilement. We are " Jews with a foreskin " does not mean that we have something more than they do, but that this something we carry within us virtually severed, since we are Jews, in the processional beat of sexual power and impotence, jouissance and abomination :

" There is /// It seems very likely that the Egyptians, who revered the instrument of generation, and who carried its image with pomp in their processions, imagined offering to Isis and Osiris, through whom everything on earth was begotten, a light part of the limb through which these gods had wished the human race to perpetuate itself." (Article Circumcision.)

By dispossessing the Jews of the invention of circumcision, Voltaire floats the metonymy of jouissance culturally. Those derisively called curti Judæi have merely inherited a fertility ritual as for the derision, it turns around : from the Jews, Voltaire passes to the Hottentots, who " have their male children cut off a testicle ". And they're the ones who laugh : " Les Hottentots sont peut-être surpris que les Parisiens en gardent deux. " (Ibid.)

After an initial phase of indignation against the fate of the Jews, to whom he assigned a privileged place in his fight for tolerance, Voltaire thus moved on to a second, much more ambiguous phase in 1764, where the discursive polarity of abomination is established: the Dictionnaire philosophique is the site of this polarity, whose expression passes through the systematic derision of Jewish history, then through revolt against the absurd horrors it conveys, finally through the contradiction and negation of the law of Moses and the Pentateuch.

This sweeping, massive, obsessive attack must not be dissociated from Voltaire's progressive identification with the Jews, of which the article Job, published in 1767, is one of the most accomplished expressions. " Bonjour, mon ami Job " (p. 246), exclaims Voltaire, opening a dialogue that will become increasingly personal. Voltaire's Jews then take on a life of their own as figures we leave behind the device of the abomination, and Voltaire enters, at the end of the 1760s, a third phase in his relationship with the Jews. This is the phase of dialogue, a dishonest dialogue to be sure, ironic and in bad faith, but one in which the relationship of a subject to an object, of an I to an Other, is reconstituted.

.

The first version of the article Jews in the Questions sur l'Encyclopédie, in 1771, is a series of letters Voltaire addresses to contemporary but fictional Jews, Joseph Ben Jonathan, Aaron Mathataï and David Wincker, characters created by Abbé Guenée. Antoine Guenée had in fact published in 1765 a Lettre du lévite Joseph Ben-Jonathan à Guillaume Vadé, accompagnée de notes plus utiles (Amsterdam, A. Root, in-8°, 28p.7), obviously addressed to Voltaire, of whom Guillaume Vadé is one of several pseudonyms. From the second printing, the opuscule takes the title Lettre du rabin Aaron Mathathaï à Guillaume Vadé, traduite du hollandois par le lévite Joseph Ben-Jonathan, et accompagnée de notes plus utiles (in-8°, 24p.8). In 1769 he published a much larger volume, the Lettres de quelques juifs portugais et allemands à M. de Voltaire, avec des réflexions critiques, etc., et un petit commentaire extrait d'un plus grand (Lisbon, [actually Paris, Prault], in-8°, 424p.), republished in 1772, 1776, 1781 and throughout the 19th century until 1863.

Voltaire's response was first the article Jews in the Questions sur l'Encyclopédie, which would continue to expand in successive reissues, and then a separate volume, entitled An Christian against six Jews, prepared in 1776, published in 17779, in which Voltaire plays the role of the Christian, and the six Jews are the fictional characters created by Guenée. The dialogic economy has thus definitively supplanted the abomination device.

Isaac de /// Pinto

In this process of dialogization, a very real interlocutor certainly played a role: Isaac de Pinto (1717-1787), a Dutch Jew of Portuguese origin. A reader and admirer of Voltaire, in 1762 he published first a small Essai sur le luxe (Paris, Lambert, in-12, 34p.), then an Apologie pour la nation juive ou Réflexions critiques sur le premier chapitre du VII. tome des Œuvres de monsieur de Voltaire, au sujet des juifs, in Amsterdam, by Jean Joubert (40p. in-8°)10. Guenée would use this Apologie against Voltaire by republishing it, with a few cuts, at the head of his Lettres de quelques Juifs portugais et allemands (the 1769 edition). Pinto defends his correligionists and sends, around July 1011, his book to Voltaire, which he accompanies with a letter :

" If I had to address myself to anyone but you, sir, I would be quite embarrassed. It is a question of sending you a review of a place12 of your immortal works ; but as I respect the author even more than I admire his works, I believe him to be a great enough man to forgive me this criticism in favor of the truth which is so dear to him, and which has perhaps only escaped him on this one occasion. I hope at least that he will find me all the more excusable, since I am acting in favor of an entire nation to which I belong, and to which I owe this apology. I had the honor, sir, of seeing you in Holland when I was quite young13. Since that time, I have learned from your works, which have always delighted me. They have taught me how to fight you; they have done more. They have inspired me with the courage to confess to you. I am beyond all expression with feelings filled with esteem and veneration &c. "

This text is not only moving, as a testimony of admiration in reprobation ; it is exceptional, as it constitutes the only moment of encounter, for Voltaire, with a real Jew, who is neither a victim of Catholic persecution, nor a fanatical follower of his religion. Isaac de Pinto's Jewish appropriation of Voltaire's writing is equally disturbing: he reads the great man as one studies the Torah, meditates on Voltaire in silence, immerses himself in his books as one immerses oneself in the Bible - a far cry from the worldly lightness of Voltaire's line, the twirling jibes and theatrical antics of this writer of conversation. Yet this appropriation is not a misunderstanding, nor a diversion on the contrary, it captures what Voltaire does not willingly give away from the, so to speak, machine-like background of his writing, this biblical rehashing and, through it, the prophetic ambition of his work, in the manner of the great prophets of the Old Testament.

.

Voltaire replied to Isaac de Pinto on July 21, 176214, acknowledging the violence and injustice of his remarks in his little opuscule " Des Juifs " of 1756 :

" To M. Pinto, Portuguese Jew, in Paris.

Aux Délices, July 2115

The lines you complain of, sir, are violent and unfair. There are some very learned and respectable men among you your letter convinces me enough. I shall take care to make a box16 in the new edition. /// When you're wrong, you must right it ; and I was wrong to attribute to an entire nation the vices of several individuals.

I'll tell you, quite frankly, that many people can't stand your laws, your books or your superstitions. They say that your nation has always done much harm to itself, and to mankind. If you're as philosophical as you seem to be, you'll think like these gentlemen, but you won't say so. Superstition is the most abominable scourge on earth it's what has caused so many Jews and Christians to have their throats cut it's what still sends otherwise estimable peoples to the stake. There are aspects in which human nature is infernal. We'd dry up in horror if we always looked at it from these sides but honest people, passing through the Grève where the wheels are wheeled, order their coachman to go fast, and go to the Opera to distract themselves from the dreadful spectacle they've seen on their way.

I could argue with you about the sciences you attribute to the ancient Jews, and show you that they knew no more than the French of Chilperic's time ; I could make you agree that the jargon of a small province, mingled with Chaldean, Phoenician and Arabic, was a poor language and as rough as our ancient Gallic but perhaps I'd make you angry, and you seem too gallant a man for me to want to displease you. Remain Jews, since you are you won't slit the throats of forty-two thousand men for not pronouncing shiboleth, nor twenty-four thousand for sleeping with Midianites but be philosophers, that's the best I can wish you in this short life.

I have the honor to be sir, with all due sentimens, your most humble, etc.

Voltaire, Christian,

And gentilhomme ordinaire de la chambre du roi très chrétien "

This letter is very strange. If Voltaire seems to start by making amends, it's only to very quickly come back to the charge that Pinto is a Jew, be ; but that he is first and foremost a philosopher, which requires that he shares Voltaire's horror and contempt for Jewish superstitions and biblical abominations. There is no Jewish science, no Jewish language from the point of view of the spirit, Judaism does not exist. Worse still, Voltaire signs as a Christian, insolently and defiantly. In the face of the Jews, he will always be a Christian, i.e. superior, and a stakeholder in the institution within which he nevertheless revels, in the face of others, in the role of histrionics. To Pinto, Voltaire reminds us that he is " gentilhomme ordinaire de la chambre du roi très chrétien ", which Pinto cannot be, nor dare hope to become.

II. The Jews of the Dictionnaire philosophique

By its central position in the process, by the chronological spread of its writing and publication, the Dictionnaire philosophique reflects the different strata of Voltaire's complex relationship with the Jews, from indignation to abomination, from abomination to dialogue.

Take, for example, the article Abraham, which we know from Voltaire's correspondence with Frederick II17 is probably the oldest in the collection. The comedy of the article lies first and foremost in the depersonalization of Abraham. " Abraham is one of those famous names... " (p. 6) ; " Besides, this name Bram, Abram, was famous in India " (p. 8) ; " [the Jewish nation] probably knew the name Abraham or Ibrahim only through the Babylonians " (p. 8) : Voltaire plays on the genre of the dictionary, which after all only offers definitions of names yet here the name itself is disseminated. Is it Abraham ? Or is it Bram, Abram, Ibrahim ? There is no /// no longer has a name, and the article's strategy is to deconstruct the dictionary entry itself.

Where does the name come from? He was " famous in Asia Minor ", " famous in India and Persia ", known to the Jews, but " by the Babylonians " : the dissemination of the referent, the scattering of cultural references, prohibits the assignment of the name to a fixed person, anchored in a given culture.

Based on Genesis chapter II, verse 28, Voltaire declares : " We are told that he was born in Chaldea, and that he was the son of a poor potter, who earned his living by making small idols out of clay " (p. 6). Ironically, Voltaire pretends to doubt the first piece of information how ? Abraham was not a Jew ? The whole article in fact tends to prove that Jews don't exist, or at any rate that their culture is a composite heap of borrowings from bordering cultures.

.

As for Abraham's potter father, this is pure invention, even though Joshua, at the beginning of his last speech from Shechem, asserts that Abraham had an idolatrous father : " Thus says Yahweh, the God of Israel : Beyond the River dwelt your fathers, Terah (=Tare), father of Abraham and Nahor, and they served other gods. " (Joshua, 24, 218.) From idolatry, Voltaire slides, with Calmet, to idol-making19, then, on his own, to pottery : the mythical figure of the origins of the people of Israel is thus reduced to the trivial image of the craftsman, itself contaminated by the biblical metaphor of the potter, found in Jeremiah and Isaiah20, and to which St. Paul gives a mystical significance21. The image then turns against the denigrating intention : the potter father, in the Christian tradition, is God himself.

The dejudaization of the great figures of the Old Testament Jewish epic is a constant in the Dictionnaire philosophique : in the article Adam, we learn from the Ezour-Vedam, which Voltaire believes to be an ancient sacred text of the Brahmans, but which is in fact a forgery forged by a Jesuit22, that " the first man was created in the Indies, etc., that his name was Adimo, which means the begetter " (p. 9).

In the same way, Job was not a Jew : " Hello, my friend Job ; you are one of the oldest originals of whom the books make mention ; you were not a Jew : we know that the book that bears your name is older than the Pentateuch. If the Hebrews, who translated it from Arabic, used the word Jehovah to mean God, they borrowed this word from the Phoenicians and Egyptians, as true scholars have no doubt. " (P. 246.) The article Job appeared in 1767 its content would be taken up in the Questions sur l'Encyclopédie in 1771 under a title that immediately indicates the author's strategy : Arabs, and, by occasion, the book of Job23. But as early as 1764, Voltaire was fulminating with Pastor Moultou about this name Jehovah : " Everything is Phoenician or Egyptian among these miserable Hebrews. Even the name Jehovah was Phoenician." (Letter to Moultou, September 15, 1764.)

That Abraham and Job were born in Chaldea, soit : Voltaire distorts and caricatures from undeniable biblical data. But what about Joseph ?

" The story of Joseph, to consider it only as an object of curiosity and literature, is one of the most precious monuments of /// of antiquity that have come down to us. It seems to be the model for all oriental writers; it is more touching than Homer's Odyssey, for a hero who forgives is more touching than one who takes revenge.

We regard the Arabs as the first authors of these ingenious fictions which have passed into all languages... " (p. 250).

This time it's hard to prove that Jacob and Rachel's son, the father of two of Israel's twelve tribes, wasn't Jewish. Voltaire therefore takes a different approach, relying on the Koranic version of the story of Joseph24. In Joseph, he exalts the perfect literary character, typical of " one of those ingenious fictions " found throughout the Orient. Joseph, like Ulysses, is a literary creation he is a model of Oriental literature : his Jewish identity, thus both dehistoricized and removed from the biblical corpus, is disseminated in a vague, denationalized Orient.

It was more difficult to proceed in the same way with the historical kings, Saul, David and Solomon. The beginning of the David article, however, is characteristic in this respect:

It was more difficult to proceed in the same way with the historical kings, Saul, David and Solomon.

" If a young peasant, looking for asses, finds a kingdom, this does not commonly happen ; if another peasant cures his king of a fit of madness, by playing the harp, this case is still very rare. " (P. 156.)

Not only is the king unnamed, demeaned to his vulgar origin, " un paysan " (which contributes, on the contrary, in the biblical narrative, to his heroisation), but Voltaire mixes without warning the evocation of Saul with that of David, so that the former peasant turns out to be Saul when we expect David, and the latter throws the reading into confusion.

In the Solomon article, Voltaire insists first on the king's illegitimacy, then on the apocryphal nature of his writings, two more ways of symbolically suppressing the existence of Israel's third king.

III. Contradiction, abomination, dialogization : the Voltairian slip

As we can see, in the set-up of the campaign against the Infâme and in the economy of the Dictionnaire philosophique, Voltaire makes the Jews play a dirty role. Let's be clear about this it's a dirty role in a noble struggle, a role unworthy of his tireless denunciation of all fanaticism, his repeated pleas for tolerance and human dignity.

Economy of abomination

This dirty role is that of the abomination. The abomination is a biblical invention it's the imaginary fabric of the Bible, between the historical horrors it describes and the prohibitions, prescriptions, punishments it prescribes. Between reality and the law. Voltaire, an assiduous and long-time reader of the Bible, perfectly grasped this extraordinary, powerful and deeply moving singularity of biblical abomination. Unfortunately, he linked it to the abomination that historically befell the Jewish people, as if the representation of this abomination in the Bible made the people of the Book responsible for having suffered it. As if, in the abomination itself, having become an autonomous machine, the victim was his own executioner, or at least absolved his executioners from carrying out, prolonging, multiplying the horrors that his history and culture had bequeathed to him.

.

This economy of abomination is essential to understanding Voltaire's writing in the Dictionnaire philosophique : Voltaire draws from it the strength, the energy of a devouring word, which engulfs its object : through irony, through indignation, the Dictionnaire deconstructs the objects announced at the entrance to each article, amalgamating them into a shapeless, senseless, abject discursive matter, which becomes the very stuff of his revolt and laughter.

Upstream of the abomination, preparing it, we find in the texts the expression of a contradiction : we hate the Jews as abominable ;; but we respect the Jews, who are our fathers through the Bible. The Jews are the crux of the discursive deconstruction Voltaire engages in based on this contradiction.

Our relationship to the Jews makes no sense, and this pas-de-sens25 gradually contaminates the entire discursive edifice of the Dictionnaire : the Jews don't exist, have invented nothing, bequeathed nothing, have no Law, no history. The whole of common culture then sinks at the turnstile of this abomination.

The abomination is born of this failure of discourse in the face of Jewish contamination. Unable to hold this discourse, whose deconstruction he stages, Voltaire conceives the device of the Dictionnaire, whose engine, the machine, is the biblical abomination.

Downstream from the abomination, on the horizon of the Dictionnaire philosophique, the Voltairian dialogical economy takes shape: Voltaire addresses Job (p.240), sets up a dialogue between Jacob and Pharaoh at the end of the Joseph article (" I am a hundred and thirty years old, says the old man, and I have not yet had a happy day in this short pilgrimage ", p. 252), taunts the entire Jewish people at the end of the article Judea (" Adieu, mes chers Juifs ; je suis fâché que terre promise soit terre perdue ", p. 253). Even in the article David, the brutal confrontation of historical facts and Voltaire's comments, in which an exacerbated subjectivity is expressed, produces a dialogical effect: " when and by whom were these marvels written ? I don't know ; but I'm quite sure... " (p. 157) and further on " je suis fâché que on ami David... ", then " je suis un peu scandalisé que David... ", then " J'ai quelques scrupules sur sa conduite... "

With " my friend David ", which directly echoes " my friend Job " and " my dear Jews ", we're very close to a second-person address. This familiarity is ambiguous: contemptuous, condescending, insulting, it also betrays Voltaire's long practice of reading the Bible, and his dwelling on and obsession with Jewish historical figures. The very status of the Voltairean subject is contaminated by the abomination that takes hold of him : the Jews don't exist, but Voltaire is in the same position, since he claims not to be the author of what he writes the Jews haven't invented anything, but this imposture is the one Voltaire claims for himself when he claims he's only compiling and rehashing the Jews haven't invented anything, but this imposture is the one Voltaire claims for himself when he claims he's only compiling and rehashing ; the Jews have bequeathed nothing, but doesn't Voltaire, as soon as he's put in the hot seat, portray himself as a bedridden old man who writes nothing, can write nothing, whom nobody reads or listens to ?

The Jewish abomination unfolds between these two limits : before it, the Jewish contradiction and the resulting discursive deconstruction after it, the splintering of the Voltairean subject, and the movement of writing towards dialogization.

The Moses article

The poetic machine of Voltairean abomination undoes discourse and, through the revolting brutality of the discursive nonsense thus produced, disseminates the subject, shattering it into dialogical instances set against one another. This process is particularly visible in the article Moses, one of the oldest in the Dictionnaire, since a first version was presented to Frederick II in 1752. But the long note added, at the end of the first sentence, in the Varberg edition of the Dictionnaire philosophique in 1765, allows us to measure in time the displacement of the Voltairian purpose.

The entire beginning of the Moses article deals with the authenticity of the biblical text : Moses is not the author of the /// Pentateuch. Voltaire focuses on the materiality of the " first copy " known of the Bible, " found in the time of King Josiah26 ". It is not the person of Moses, nor the content of the Bible that counts : it is this concrete, palpable reality of the first manuscript.

Following this preamble, Voltaire poses a series of questions, which he numbers from 1 to 8. These questions consist of as many contradictions : to go towards the contradiction is to uncover in the biblical object (for the object of this article, at least in its first state, is the Bible and not Moses, who is merely its metonymic primer) the essential pas-de-sens from which all discourse becomes impossible and will be undone.

.

Voltaire first goes ever further in the materialization, the concretization of the discursive object : of Scripture (" par l'Écriture même il est avéré... ", p.303), to the " first known copy ", from " this unique copy " to the publication of the book by Secretary Saphan27, from the belatedly published book to the forgery forged from scratch by Ezra28 (" that is absolutely indifferent as soon as the book is inspired ", persifutes Voltaire, p.304) we move on to language, and soon to the medium of Scripture not " papyros ", but " hieroglyphs [engraved] on marble or wood ". The material, visual, thick, voluminous, Egyptian object bluntly contradicts the initial symbolic object, the Scriptures, divine, mosaic, Hebrew.

.

Voltaire then unfolds, from this materiality that makes no sense, the delirious, ironic and mocking picture of the thousand and one nights of the Exodus story, with its magical garments that don't wear out and its magical workers who made the golden calf, then, from the calf, powdered gold29, then the tabernacle with its luxurious display of silverware and precious fabrics. The aim is to point out that it's " an obvious contradiction to say that there were founders, engravers, embroiderers, when we had no clothes, no bread. "

The whole of this development is founded on a logic of contradiction : " Some contradicts add that... " ; " Is it likely that... " ; powdered gold is an " impossible operation " ; " this even fortifies the opinion of the contradictors " ; " it is an obvious contradiction to say " ; " could he have contradicted himself in the Deuteronomy ? ".

The contradiction remains on the verge of abomination : throughout this first part of the Moses article there is no mention of the errors and horrors committed by Moses, and Voltaire maintains an ironic yet dispassionate distance from his subject.

The shift begins with the seventh question : " whereas not only were there no kings among this people, but they were abhorred ". Taking advantage of the chronological contradiction (Moses " prescribes rules for Jewish kings30 " at a time when the Jews had no kings), Voltaire evokes, as if in passing, the Exodus Jews' horror of kings : the economy of abomination is set in motion.

In the eighth question, we move from the evocation of laws (prescriptions on the tabernacle, laws on marriage, political organization of cities, institution of kings) to the evocation of facts : " I brought you out six hundred thousand fighting men from the land of Egypt ".

From this virtual army, which is never described as such in Exodus31, Voltaire moves on to the massacre of the first-born of Egypt : " the God who speaks to you has slaughtered, to please us, all the first-born of Egypt " (p. 306) ; we find the oral imaginary of abomination32. Gutting goes down the throat, and here gives pleasure. The abject, distance-less pleasure will soon turn, from the pleasure of seeing others' children slaughtered to the pleasure of slaughtering one another : " you command your Levites to slaughter twenty-three thousand of your people " (p. 307 ; this is the punishment Moses inflicts after the episode of the golden calf)33.

The abomination is reversible. At first, it's the evocation of the desert walk, whose itinerary is absurd, and thus testifies, in the narrative, to a logical contradiction. But the desert is soon portrayed as an abominable place: " the horrible deserts of Etham, Kadesh-Barnea, Mara, Elium, Horeb and Sinai " (p.306) " dreadful solitudes ". Voltaire takes the word desert in a literary, even theatrical sense : the desert is not a climatic desert (marked by drought, sand, heat, and susceptible of a certain beauty), but a moral desert, a " horrible " place, inhuman, abandoned34.

In this shift from contradiction to abomination, the process of materializing, concretizing the object played an essential role : writing desubjectivizes its object Moses is a book, a copy, then an itinerary, a landscape, an opera set. Voltaire works to transform Moses into pasteboard.

.

Parallel to this moralization/abjection of the object, we witness the deconstruction of the subject of discourse. It's not Voltaire who's speaking but, from the very start of the article, " plusieurs savants " quickly designated as " contradicteurs ", which implies, at least implicitly, the confrontation of two discourses, or, rather, the face-off of a biblical discourse and its contradiction, of an instituted exegesis (dom Calmet) and its critique.

The contradiction dialogizes. But when discursive deconstruction precipitates textual production into an economy of abomination, this dialogization ceases to manifest itself as external and distanced (a quarrel between exegetes of the Bible) to settle at the heart of the object, between the Jews themselves. As early as the 8th question, Moses addresses the Jews ("Could it be that he had said to the Jews... ? "), and the Jews, at great length, answer him ("Would not the Jews have answered him... "). These are exactly Voltaire's Jews unreal, fabricated by him from his critique of the biblical text, revolted and revolting Jews, whose surrealist tableau feeds the tourniquet of abomination, of Voltairean creative repetition.

It is these virtual, revolting Jews who, in the article, provoke against Moses the evocation of the Jews as abominable : " you brought us out of Egypt as thieves and cowards ".

From the abomination of the Jews of that time, we pass, very quickly, to that of the Jews of today : " This is what those murmuring Jews, unjust children of the wandering Jews, dead in the deserts, could have said to Moses, if he had read them Exodus and Genesis.But how could Moses have read books that Voltaire has just proved he did not write to the children of the Jews of the Exodus and Desert generation, when he himself died? /// in the desert, without reaching the Promised Land? Here, the text betrays a logic of fantasy that has nothing to do with the exegetical rationality asserted and claimed at the beginning of the article, in the tradition of Bayle's and Moreri's Dictionaries. Even dispossessed of his history and his book, Moses remains the abominable interlocutor, the villain whose fanatical, irrational word always resurfaces before us. But who are we if not, superimposed on the learned contradictors at the beginning of the article, these " murmuring Jews " at the end ... We are the " unjust children of the wandering Jews " : this is how Voltaire, as a Christian, defines himself.

Murderers, unjust, vagabonds and dead, Voltaire's Jews figure the abomination in us, i.e. both the infamous and the fight against the infamous. The last page of the Moses article is then unleashed in an exalted and revolting evocation of " this incredible butchery ", of which Moses was twice guilty, first by slaughtering the worshippers of the golden calf, then the idolaters who had committed adultery with the Midianite women35.

But it's important to understand what this picture of unprecedented violence is aiming at: perhaps to indict the Jews, but certainly not to precipitate action, reprisals, repression against them. To a certain extent, Voltaire's aim is far more appalling: symbolic annihilation. There is no conscious strategy here, no concerted order of discourse. Rather, what emerges is the logical horizon of an economy of abomination.

.

The diatribe of the " murmuring Jews " against Moses does not indeed lead to condemnation, but stops at the edge of this illogical assertion that neither they nor he can exist.

" A few more actions of this gentleness, and there would have been no one left.

No, if you had been capable of such cruelty, if you could have exercised it, you would be the most barbarous of all men, and all the torments would not suffice to atone for so strange a crime. "

Moses was an exterminator : a little more, " and there would have been no one left ", no one then of those Jews from whom nevertheless descend the " murmuring Jews ". But he himself, for these abominable actions that threaten to wipe out his contradicts in front of him, is sent back to a strange unreal : " if you had been... you would be... and all the torments wouldn't suffice... " Just as his contradicts, stricken by the abomination of their fathers (the biblical abomination of the golden calf and sacred prostitution), almost didn't exist, so Moses, caught in the act of butchery (the Voltairian abomination of the twenty-three thousand, then the twenty-four thousand slaughtered), cannot, as such, exist.

Dissemination of the subject, normalization of History

The abomination is a virtualization. Its horizon is the splintering of the subject : this is the step taken, in 1765, by the introductory note to the Moses article. "Is it really true that there was a Moses? Moses never existed, is a Jewish affabulation. Voltaire's demonstration breaks down into two parts. Firstly, there is no evidence for the existence of Moses outside the Bible. Secondly, Moses is a rewriting of Bacchus. Voltaire removes Moses from history and reinscribes him, in a second stage, in fable. The stakes are clear: there is no Jewish exception, no original singularity, no Jewish principle or symbolic foundation for humanity. The negation of Moses, the conjuring up of the abominations of the Exodus by the screen figure of Bacchus (to whom Voltaire may attribute the miracles of Egypt, but certainly not the anti-idol massacres in the Desert) aim at a normalization of History.

The hierarchy between peoples is measured by the testimonies of a community of experts (Sanchoniathon, Manetho, Megasthenes, Herodotus, even Flavius Josephus), themselves moderated and relativized according to a political power that is supposed to be historically measurable, thus constituting a kind of standard of reality. In the face of this exegetical and erudite practice, which, with Voltaire, is in the process of transforming itself into a system of globalized expertise, the Jews are a scandal: what is " a small people of barbaric slaves ", " a people so poor, so ignorant, so foreign in all the arts " compared to the great empires of India, Egypt, Persia, or to a commercial power like that of the Phoenicians ?

.

Voltaire faces a distortion between the position, the military, political, cultural, commercial value of the Jewish people and the symbolic power, the constitutive function of Judaism for humanity. This distortion is the implicit starting point from which what is formulated as Jewish contradiction slips, skids, towards abomination, then disseminates into dialogization. There is in this distortion, which Voltaire constantly measures without naming it, a kind of capitalist objectification of the abomination : it is because of this distortion of value (political, cultural, historical) that the Jewish people is abominable.

Once again, it would be of little interest to judge Voltaire's untenable position morally, or still less scientifically : the problem is neither whether this distortion is real, nor whether it is abominable, but rather what it symptomatizes of the Dictionnaire philosophique enterprise, of which it reveals an essential ideological background.The fight for the Enlightenment, for the desacralization of biblical texts, for tolerance and against fanaticism, is based on this desire for the ideological normalization of the world, the reduction of culture to evaluable knowledge, to topical fictional materials, whose globalized circulation breaks down borders and identity differences.

Voltairean tolerance proceeds from what we today call globalization, of which the device of the Dictionnaire philosophique figures the nobility, the rationality, the progress in humanity, but also the abominable reverse to which it always returns, which resists it, and from which it feeds. And that flip side, for Voltaire, is the Jews.

Other Voltairean references:

I. The discourse of abomination

Destabilizing the reader by involving him in the abomination :

" Trouvez bon que je vous demande ici quelques éclaircissemens sur un fait singulier de votre histoire ; il est peu connu des dames de Paris et des personnes du bon ton.

It was not thirty-eight years since your Moses had died, when the woman in Michas, of the tribe of Benjamin, lost eleven hundred shekels, which are said to be worth about six hundred pounds of our currency. Her son returned them to her, but the text doesn't say whether he had stolen them. Immediately the good Jewess had idols made of them, and built a little itinerant chapel for them, according to custom. " (QE, art. Juifs, IV, Fourth letter. On the woman in Michas.)

The history of the Jews

Voltaire is not a man of discourse and system. He's a writing machine, a writing monster, absorbing and recycling everything he finds around him. To feed this machine, Voltaire was passionate about history in general, and Jewish history in particular, first and foremost because it provided ample material.

But this history, he treats mechanically, without precautions, without consideration, without ethics. He cuts it up, distorts it, trivializes it : in a word, he profanes it and feeds off this profanation.

The law of /// Jews

" Their law must appear to every polite people as strange as their conduct ; if it were not divine, it would appear a law of savages who begin to assemble into a body of people ; and being divine, one cannot understand how it has not always subsisted, and for them and for all men. " (QE, art. Jews, II.)

see article Moses

The philosophy of the Jews

" It is certain that the Jewish nation is the most singular that has ever been in the world. Although it is the most contemptible in the eyes of politics, it is, in many respects, considerable in the eyes of philosophy. " (QE, art. Jews, I.)

" You ask what was the philosophy of the Hebrews ; the article will be quite short : they had none. Their very lawgiver speaks expressly in no place either of the immortality of the soul or of the rewards of another life. " (QE, art. Jews, I.)

see article Ame

II. The discourse of conjuration

The mother

" O devout tigers ! fanatical panthers ! who have such great contempt for your sect, that you think you can support it only by executioners, if you were capable of reason, I would question you, I would ask you why you immolate us, we who are the fathers of your fathers.

What could you answer, if I told you : Your God was of your religion ? He was born a Jew ; he was circumcised like all other Jews ; he received by your admission the baptism of the Jew John, which was an ancient Jewish ceremony, an ablution in use, a ceremony to which we subject our neophites ; he fulfilled all the duties of our ancient law, he lived a Jew, he died a Jew ; and you burn us because we are Jews ! " (Sermon by Rabbi Akib, 1761.)

" Denatured children, we are your fathers, we are the fathers of Muslims. A respectable and unhappy mother had two daughters, and these two daughters drove her out of the house ; and you blame us for no longer living in this destroyed house ! You make us a crime of our misfortune, you punish us for it." " (Sermon by Rabbi Akib, 1761.)

" They are the last of all peoples among Muslims and Christians, and they believe themselves to be the first. This pride in their abasement is justified by an unanswerable reason, which is that they are really the fathers of Christians and Muslims. The Christian and Muslim religions recognize the Jewess as their mother ; and, by a singular contradiction, they have both respect and horror for this mother. " (QE, art. Jews, I.)

" All of a sudden you lose five beautiful cities that the Lord destined for you at the end of Lake Sodom, and this for an inconceivable attack on the modesty of two angels. In truth, it's much worse than what your mothers are accused of with the goats. How can I not have the greatest pity for you when I see the murder, sodomy and bestiality of your ancestors, who are our first spiritual fathers and close relatives according to the flesh? For after all, if you descend from Shem, we descend from his brother Japheth : we are obviously cousins. " (QE, art. Jews, IV, Second letter. On the antiquity of the Jews.)

" If Jewish Ladies slept with goats.

You claim that your mothers didn't sleep with goats, nor your fathers with goats. But tell me, gentlemen, why you are the only people on earth to whom the laws have ever made such a defense. Would any legislator ever have ventured to promulgate this bizarre law, if the offense had not been common ? " (QE, art. Jews, IV, Fifth letter.)

Human sacrifice : Jephthah

" After this butchery36, it's no wonder that this abominable people sacrifices human victims to their god, whom they call Adonai, from the name Adonis, which they borrow from the Phoenicians. The twenty-ninth verse of chapter xxvii of Leviticus expressly forbids the redemption of men devoted to the anathema of sacrifice, and it is on this law of cannibals that Jephthah, some time later, immolates his own daughter. " (Sermon of fifty, 1749 ?)

" Scholars have agitated the question whether the Jews indeed sacrificed men to the Divinity, like so many other nations. It's a question of name : those whom this people consecrated to anathema were notn slaughtered on an altar with religious rites ; but they were nonetheless immolated, without it being permissible to forgive a single one. The Leviticus expressly forbids, in verse 27 of chap. xxix, to redeem those who will have been vowed ; it says in its own words : It must that'they die. It was by virtue of this law that Jephthah vowed and slaughtered his daughter, that Saul wished to kill his son, and that the prophet Samuel cut King Agag, Saul's prisoner, in pieces. " (QE, art. Jews, I.)

" It is expressly commanded, in the xxviith chapter of Leviticus, to immolate the men who will have been vowed in anathema to the Lord. "No ransom," says the text "the promised victim must expire." This is the source of the story of Jephthah, whether his daughter was really immolated, or whether this story is a copy of that of Iphigenia this is the source of Saul's vow, who was going to immolate his son, if the army, less superstitious than he, had not saved the life of this innocent young man.

It is therefore only too true that the Jews, according to their law, sacrificed human victims. " (QE, art. Jews, II.)

" Allow me first of all to be moved by all your calamities ; for, in addition to the two hundred and thirty-nine thousand and twenty Israelites killed by the Lord's command, I see Jephthah's daughter immolated by her father. He had fit as ilo l'had vowed. Turn every way ; twist the text ; argue against els fathers of the church : he did to her as he had vowed, and he had vowed to slit his daughter's throat to thank the Lord. A beautiful act of grace!

Yes, you have immolated human vistims to the Lord ; but console yourself ; I have often told you that our Welches and all nations did the same once. M. de Bougainville has just returned from the island of Taïti, the island of Cythère, whose peaceful, gentle, humane and hospitable inhabitants offer travellers everything in their power, the most delicious fruits and the most beautiful and easy-going girls on earth. But these peoples have their jugglers, and these jugglers force them to sacrifice their children to smagots whom they call their gods. " (QE, art. Juifs, IV, Cinquième lettre, Calamités juives et grands assassats.)

" You dare to assure me that you do not immolate human victims to the Lord ; and what then is the murder of Jephthah's daughter, really immolated, as we have already proved by your own books ?

[...] Did not the priest Samuel hack to pieces the wren Agag, whose life the wren Saul had saved ? did he not sacrifice him as the Lord's portion ?

Or renounce your books, in which I firmly believe, according to the decision of the church, or confess that your fathers offered rivers of human blood to God, more than any people in the world ever did. " (QE, art. Jews, IV, Fifth /// letter)

" Jewish children immolated by their mothers.

I tell you that your fathers immolated their children, and I call your prophets as witnesses. Isaiah reproaches them for this cannibalistic crime: "You immolate your children to the gods in torrens, under stones."

You're going to tell me that it wasn't to the Lord Adonai that women sacrificed the fruits of their wombs, that it was to some other god. It really doesn't matter whether you called Melkom, or Sadai, or Baal, or Adonai, the one to whom you immolate your children; what matters is that you were parricides. It was, you say, to foreign idols that your fathers made offerings Well, I pity you even more for descending from parricidal and idolatrous forefathers. I groan with you that your fathers were still idolaters for forty years in the wilderness of Sinai, as Jeremiah, Amos and St. Stephen expressly say.

[...] you were only faithful to one God after Ezra restored your books. That's when your true, uninterrupted worship begins. And, by an incomprehensible providence of the Supreme Being, you have been the splus unhappy of all men since you have been the most faithful, under the kings of Syria, under the kings of Egypt, under Herod the Idumean, under the Romans, under the Persians, under the Arabs, under the Turks, until the time when you do me the honor of writing to me, and when I have that of answering you. " (QE, art. Juifs, IV, Fifth letter.)

" My tenderness for you has but one word left to say. We have hung you between two dogs for centuries37 ; we have pulled your teeth to force you to give us your money ; we have driven you out many times for greed, and called you back for greed and stupidity we still charge you in more than one city for the freedom to breathe the air we have sacrificed you to God in more than one kingdom we have burned you in burnt offerings : for I do not wish, following your example, to conceal the fact that we have offered sacrifices of human blood to God. " (QE, art. Jews, IV, Seventh letter.)

The Jews, wretched and abominable

" You are struck by this hatred and contempt that all nations have always had against the Jews : it is the inevitable consequence of their legislation they had to either subjugate everything, or be crushed. They were commanded to abhor the nations38, and to believe themselves defiled if they had eaten from a dish that had belonged to a man of another law. [...]

They were therefore rightly treated as a nation opposed in everything to the others ; serving them through avarice, hating them through fanaticism, making usury a sacred duty. And these are our fathers ! " (Essai sur les mœurs, ch. ciii, 1761 ; II, 64.)

" Our enemies make us a crime today for having robbed the Egyptians, for having slit the throats of several small nations in the towns we seized, for having been infamous usurers, for having also immolated men, for having even eaten them, as Ezekiel says. We have been a barbarous, superstitious, ignorant, absurd people, I admit ; but would it be right to go today and burn the Pope and all the monsignori of Rome, because the first Romans kidnapped the Sabines and stripped the Samnites ? " (Sermon from Rabbin Akib, 1761.)

" It follows from this abbreviated picture that the Hebrews were almost always either wanderers, or brigands, or slaves, or /// seditious : they are still wanderers today on earth, and in abhorrence to men, assuring that heaven and earth and all men were created for them alone.

It is evident from the situation of Judea and the genius of this people that they were always to be subjugated. " (QE, art. Jews, I.)

" It is commonly said that the horror of the Jews for the other nations came from their horror for idolatry ; but it is far more probable that the manner in which they first exterminated some of the peoples of Canaan, and the hatred which the neighboring nations conceived for them, were the cause of this invincible aversion which they had for them. As they knew no peoples but their neighbors, they thought that by abhorring them they hated the whole earth, and so accustomed themselves to be the enemies of all men. " (QE, art. Jews, I.)

" Finally you will find in them only an ignorant and barbarous people, who have long joined the most sordid avarice to the most detestable superstition, and the most invincible hatred for all peoples who tolerate and enrich them. "Yet we must not burn them." " (QE, art. Jews, I.)

" We've already seen how the Inquisition had the Jews banished from Spain. Reduced to running from land to land, from sea to sea to earn their living everywhere declared incapable of owning any property, and of having any employment, they saw themselves obliged to disperse from place to place, and to be unable to establish themselves fixedly in any country, for want of support, of power to maintain themselves there, and of enlightenment in the military art. Trade, a profession long despised by most European peoples, was their only resource in these barbaric centuries; and, as they necessarily grew rich, they were called infamous usurers. The kings, unable to delve into their subjects' purses, tortured the Jews, whom they did not regard as citizens.

What happened in England to them may give some idea of the vexations they suffered in other countries. King John39, in need of money, had the wealthy Jews of his kingdom imprisoned. One of them, who had seven teeth pulled out one after the other to get his property, gave a thousand silver marcs to the eighth. Henri III40 drew from Aaron, Jew of York, fourteen thousand silver marcs, and ten thousand for the queen. He sold the other Jews of his country to his brother Richard for the term of a year, so that this earl might disembowel those whom the king had already flayed, as Matthew Pâris41. "(QE, art. Jews, III.)

III. The discourse of normalization

The Jews didn't invent anything

The Jews transmitted nothing

" You then ask whether the ancient philosophers and legislators drew from the Jews, or whether the Jews took from them. We must refer to Philo : he avoiue that before the translation of the Seventh foreigners had no knowledge of the books of his nation. Great peoples cannot draw their laws and knowledge from a small, obscure and enslaved people. The Jews did not even have books in the time of Osias. " (QE, art. Jews, I.)

The Jews, like the Gebras and the Banyan trees

" This is not how we treat the banians in the Indies, who are precisely what the Jews are in Europe, separated from all peoples by a religion as old as the annals of the world, united with them by the necessity of the trade of which they are the factors, and as rich as the Jews are among us. These banians and the Gebras, as ancient as they are, as separated from other men as they are, are nevertheless well wanted everywhere; /// the Jews alone are in abhorrence to all the peoples among whom they are admitted. " (Essai sur les mœurs, ch. cii, 1761 ; II, 58.)

But aren't these Parsis, these Magi older than us, these spremiers Persians who were once our conquerors and masters, and who taught us to read and write, scattered like us over the earth ? Are not the Banians, more ancient than the Parsis, scattered across the frontiers of India, Persia and Tartary, without ever merging with any nation, without ever marrying foreign women ? What am I saying ! do your Christians, people living peacefully under the yoke of the great padisha of the Turks, ever marry Muslims or girls of the Latin rite ? What advantages do you claim, then, to derive from the fact that we live among nations without incorporating ourselves into them ? " (Sermon from Rabbin Akib, 1761.)

" Do you want to live peacefully, imitate the Banians and the Gebras ; they are much older than you, they are scattered like you, they are without a homeland like you. The Gebras especially, who are the ancient Persians, are slaves like you, after having been your masters for a long time. They say nothing; take this side" (QE, art. Juifs, IV, Seventh letter.)

Conclusion : apostrophes to the Jews

" Far from hating you, I have always pitied you. If I have sometimes been a little mocking, as was the good Pope Lambertini42 my protector, I am no less sensitive. I cried at the age of sixteen when I was told that a mother and daughter had been burned for having eaten a bit of lamb cooked with slaitues on the fourteenth day of the red moon ; and I can assure you that the extreme beauty that was extolled in this girl did not enter into the source of my tears, even though it should augur in the spectators horror for the murderers, and pity for the victim. " (QE, art. Jews, IV, First letter, to Messrs. Joseph Ben Jonathan, Aaron Mathataï and David Wincker.)

" It may be that the negroes of Angola and those of Guinea are much older than you, and that they worshipped a beautiful serpent before the Egyptians knew their Isis, and that you dwelt near Lake Sirbon ; but the negroes have not yet communicated their books to us. " (QE, art. Juifs, IV, Second letter. De l'antiquité des Juifs.)

" Don't reproach me for not loving you : I love you so much, that I wish you were all in Hershalaim instead of the Turks who are devastating your whole country, and yet have built a rather fine mosque on the foundations of your temple, and on the platform built by your Herod.

You would cultivate this unfortunate desert as you once cultivated it ; you would still carry soil on the rump of your arid mountains you would not have much wheat, but you would have quite good vines, a few palm trees, olive trees and pastures.

Although Palestine does not equal Provence, and Marseille alone is superior to all Judea, which did not have a seaport ; although the city of Aix is in an incomparably more beautiful situation than Jerusalem, you could do with your land much what the Provençals did with theirs. You'd perform your detestable music to your heart's content, in your detestable jargon.

[...] Return to Judea as soon as you can. I ask of you only two or three Hebrew families to establish at Mount Krapack43, where I dwell, a small but necessary trade. For if you are very ridiculous theologians (and so are we), you are very intelligent traders, which we are not. /// not. " (QE, art. Jews, IV, Sixth letter.)

Notes

///

1References to the Dictionnaire philosophique are given in Raymond Naves' edition revised by Olivier Ferret, Classiques Garnier, 2008.

2La Correspondance littéraire evokes this period on the occasion of the publication of La Bible enfinitely explained in 1776 : " Every morning, during breakfast, a chapter of the Holy History was read, on which everyone made his reflections in his own way. " (XI, 348.)

3" I don't say they were all burned to a crisp. We are told that three were whipped to death, and two sent back to prison. Thirty-two were consumed by the flames in this savage sacrifice. What was their crime? None other than that of having been born." We know of this Sermon from rabbi Akib three editions in 1761.

4Voltaire's intermediary was the Genevan pastor Moultou, whose two learned friends were Pastor Vernes and Abauzit, administrator of the Geneva library.

5Allusion to the repression ordered by Moses after the episode of the golden calf. See Exodus, XXXII, 28.

6Numbers, XXV, 1-9.

7Bnf D-21438 and ZP-2140. Arsenal 8-BL-35848(2).

8Bnf D21439 ; Z-27303 ; Z Bengesco-518 ; Z Beuchot-922 ; Z-Beuchot-1299. Arsenal 8-BL-35848(1).

9The work advertises itself as published " à La Haye, aux dépens des libraires ", but was actually printed in Geneva. It will have little resonance. See R. Pomeau, On a voulu l'enterrer, Oxford, 1994, pp. 180-182.

10Bnf A-12749. Pinto's Apologie would be the subject of two reviews in the Bibliothèque des sciences and des beaux-arts (1762) and The Monthly Review (1763). Pinto replies in 1766 : Reply from the'author from. l'Apology of the nation, &tc. a two critics, which have been made from this little written, The Hague, Pierre Gosse junior and Daniel Pinet, 40p. in-8°. Bnf A-12758.

11D10579..

12Pinto is referring to the essay " Des Juifs " published in volume V (and not VII, as he claims) of the Collection complete works of Voltaire in 1756. This text will be added to the Jews article of the Questions sur. /// the'Encyclopédie and will become section I in the posthumous edition of the Dictionnaire philosophique.

13Voltaire had made a first trip to Holland in 1722 : but Isaac de Pinto was only five years old... After the scandal of the Mondain (1736), he hid for a while in Leiden and Amsterdam, where he prepared an edition of his works for the bookseller Ledet (letter to the Marquis d'Argens, January 28, 1737, from Amsterdam).

14D10600.

15On the same day, Voltaire wrote to Cardinal de Bernis, sending him L'Histoire desCalas : " Read this, my lord, I beseech you, and see if it is possible that els Calas are guilty. "

16The cardboard, interposed between the plate where the characters are arranged and the sheet to be printed, makes it possible to remove part of the text without redoing the typographic composition of the work. The cardboard introduces a blank in the page in place of the printed text to be removed. A censored edition of a work was called a hardback edition. Voltaire never fulfilled this promise.

17See the letter of sept-oct 1752.

18Servieruntque diis alienis in the Vulgate. Joshua reminds the people of Israel that their God has not been given to them from time immemorial, that he has made a covenant with them. He invites them to renew this covenant : " put away the gods which your fathers served beyond the River and in Egypt, and serve Yahweh " (24, 14).

19" The Arabs and Turks give as Abraham's father a man named Azor, and as his forefather Tharé. Many Orientals believe that Azor is the same as Tharé, and that he was Abraham's father. The Persians and Turks call him Pour-Tirasch, i.e. sculptor of idols, because the Muslim tradition is that he was not only an idolater, but also an idol-maker and merchant; that he had great disputes with Abraham, his son, on this subject; that he accused him to Nemrod, who had him thrown into a fiery furnace. [...] The Jews tell us that Thare was not only an idolater, but also a sculptor and merchant of idols that one day Thare, having gone on a journey, left Abraham in charge of his store... " (Calmet, Dictionnaire historique et critique de la Bible, article Tharé.) Calmet thus relies on Arab, but also Jewish, tradition, without specifying his sources.

20" I will break this people and this city as one breaks the potter's vessel, which can no longer be mended " (Jr 19 10) ; he who rejects the word of the prophets, God " will break him as one breaks a potter's jar " (Is. 31, 14).

21" Is not the potter master of his clay to make of the same dough a vessel of luxury and an ordinary vessel ? " (Rom. 9, 21), i.e. God can give grace to one and withhold it from another.

22Voltaire delivered the manuscript to the King's Library in 1761. It was published in 1778 by Baron de Dainte-Croix under the title /// L'Ezour-Vedam, or l'Ancient commentary du Vedam, containing the'exhibition of opinions. religious and philosophical of Indians,translated from samscretan by un Brame, revised and published with preliminary observations , des notes and des clarifications, à Yverdun [actually in Avignon], imprimerie de M. Felice, 2 vols. in-12. Bnf 8-O2K-433 (1 and 2) ; Z Beuchot-1220 (1 and 2).

The Ezour-Védam is presented as a commentary on fragments of ancient Indian sacred texts. Confusion over the book's authenticity is partly due to the ambiguity of the title, which can be understood either as " commentary [modern] on sacred texts ", which it really is, or as " ezour-veda " or yajûr veda, the second of the four canonical sacred texts of ancient India, reputed lost at the time.

It seems that the Ezour-Védam was written by a Jesuit missionary (from the 17the century ?) with the aim of reconciling some of India's beliefs and myths with the Christian religion and, on the basis of this conciliation, more easily converting Hindu populations to Christianity. Voltaire, of course, saw it quite differently: not only did the Ezour-Vedam overturn Mosaic chronology by establishing the anteriority of Indian myths over biblical ones, but by describing a monotheistic and virtuous Aryan society, anterior to the polytheistic Hindu society corrupted by Bramins, it gave the Ferney philosopher a kind of deistic original model on which to base his theological battle against the infamous.23It reads that " Job, the hero of the play, cannot have been a Hebrew. [...] It was thought that he could have been a Jew, because in the twelfth chapter the Hebrew translator put Jehova in place of El, or Bel, or Sadai. But what educated man is there who does not know that the word Jehova was common to the Phoenicians, Syrians, Egyptians and all the peoples of the neighbouring regions. [...] It therefore seems very well proven that the book of Job cannot be by a Jew, and is prior to all Jewish books. "

24The episode of Joseph's tunic, torn by Putiphar's wife not from the front, but from the back, comes from the Koran. Voltaire did not take this detail from Calmet, who at least does not mention it in the Joseph article of his Dictionnaire de La Bible.

25On the notion of pas-de-sens, see J. Lacan, Le Séminaire. Livre V. Les Formations de l'inconscient, 1957-1958, Seuil, 1998, chap. V, esp. pp. 98sq. Lacan forges this notion from Freud's analysis of the mot d'esprit in its relation to the unconscious. For Freud, the mot d'esprit first produces an " absurd façade " : " the nonsense [of the mot d'esprit is placed at the service of the same figurative ends " as the dream (Freud, The Word d'mind and its relation with the'inconscious, folio essais, p.315). /// Lacan compares this envelopment of meaning in nonsense to a short semiotic circuit (Freud's " amazement and illumination ", p. 127 the " discharge " of " psychic energy ", p.269) the word "spirit" literally has no meaning, but it takes a signifying step that turns this lack of meaning into the meaning of the word "spirit". This step is the pas-de-sens.

26" The high priest Hilqiyyahu said to the secretary Shaphân : I found the book of the Law in the Temple of Yahweh. Hilqiyyahu gave the book to Shaphan, who read it. Saphan then reads this book to King Josiah, also known as " book of the covenant " (23,2) which is not the whole Pentateuch, but may be Deuteronomy. Josiah then ordered a great religious reform.

27" et le secrétaire Saphan publia le livre de la loi l'an du monde 3380 " : Voltaire plays on words. If we respect the biblical text, Voltaire's "publish" must be understood in the sense of making public by reading before Josiah, and not of printing, of course, nor even of distributing by copying. As for " book of the law ", this is not a metaphor for the Bible, but, literally, Deuteronomy.

28" They told the scribe Ezra to bring the book of the Law of Moses, which Yahweh had commanded Israel. Then Ezra the priest brought the Law before the assembly, which consisted of men, women and all who were of the age of reason. It was the first day of the seventh month. In the square before the water gate he read from the book from dawn until noon [...] : all the people gave ear to the book of the Law. " (Nehemiah, 8, 2-3.) The episode repeats that of Josiah.

29In La Bible enfinitely explained, Voltaire will specify : " This article is not the least difficult of Holy Scripture. We must first agree that gold cannot be reduced to powder by throwing it into the fire it is an operation impossible to all human art : all the systems, all the suppositions of several ignoramuses who have spoken haphazardly about things of which they have not the slightest knowledge, are far from solving this problem. The drinking gold they speak of is gold dissolved in aqua regia and this is the most violent of poisons, unless its strength has been weakened yet gold is only very imperfectly dissolved and the liquor in which it is always mixed is always very corrosive : one could also dissolve gold with sulphur but this would make a detestable liquor that would be impossible to swallow. [...] Everything Dom Calmet says about this is from a man who knows nothing of the principles of chemistry. We see here, from the logical and scientific contradiction (" une opération impossible ", an expression taken from the Dictionnaire), the discourse skidding into abomination (" le plus violent des poisons ", a " liqueur... very corrosive ", " une liqueur détestable "), and in his oral imagination (" qu'il serait impossible d'avaler "). The abomination in turn triggers dialogization, with the invective to dom Calmet.

30Deuteronomy, 18, 14-20. The text foresees, with the utmost defiance, the case where, in the future, the people of Israel would choose a king : " When you come to this land which Yahweh your God is giving you, and you take possession of it and dwell in it, if you say to yourself, I want to establish over me a king, like all the nations around... "

31" The Israelites set out from Rameses in the direction of Sukkot numbering nearly six hundred thousand footmen - just the men, not counting their families. " (Exodus, 12, 37.) In the Vulgate : sescenta ferme milia peditum virorum. The word " combattants " is a tendentious innovation by Voltaire, as is the shift of the narrative to the 1st person.

32This is another Voltairean slip. The Exodus account simply bears " In the middle of the night, Yahweh smote all the firstborn in the land of Egypt " (Exodus, 12, 29). To strike, percussit in the Vulgate, is not to slit the throat.

33In fact Exodus speaks of only three thousand men : " The sons of Levi did as Moses had said, and of the people there fell that day about three thousand men. " (Exodus, 32, 28.) The error of the twenty-three thousand is not Voltaire's, but the Vulgate's, perhaps under the influence of the text of the First Epistle to the Corinthians (1Co10, 8), itself inspired by the episode of the Baal of Peor and the massacre of Shittim (Num 25, 1-9).

34Note 18 of the Moses article in the Ferret-Naves edition is therefore a misinterpretation.

35" Israel settled in Shittim. The people played the harlot with the daughters of Moab. [...] A man of the Israelites came and brought this Midianite woman to his brothers, before the very eyes of Moses and the whole community of Israelites weeping at the entrance to the Tent of Meeting. At this sight, Pinhas, son of Eleazar, son of Aaron, the priest, rose from the midst of the community, seized a spear, followed the Israelite into the alcove and there pierced them both, the Israelite and the woman, in the belly. The plague that had struck the Israelites was stopped. Twenty-four thousand of them were dead..." (Numbers, 25, 1 and 6.) It is not because of a single Midianite that the punishment is unleashed this episode comes, as a challenge to Moses, after the establishment, in Peor, of idolatrous worship and sacred prostitution with the Moabites.

36Massacres perpetrated at Moses' behest.

37" They were always careful to hang them between two dogs when they were condemned. " (Voltaire, Essai sur les mœurs, chap. 103, " De l'état des Juifs en Europe ", ed. Pomeau, Garnier, II, 62.)

38Deuteronomy, VII, 16.

39John the Earthless.

40Henry III of England (1207-1272), son of John Landless, distinguished himself by promulgating anti-Semitic decrees, for example forcing Jews to wear " the badge of shame ", in the shape of the double table of the Law.