Instability of the notion

Tolerance : an origin and an end

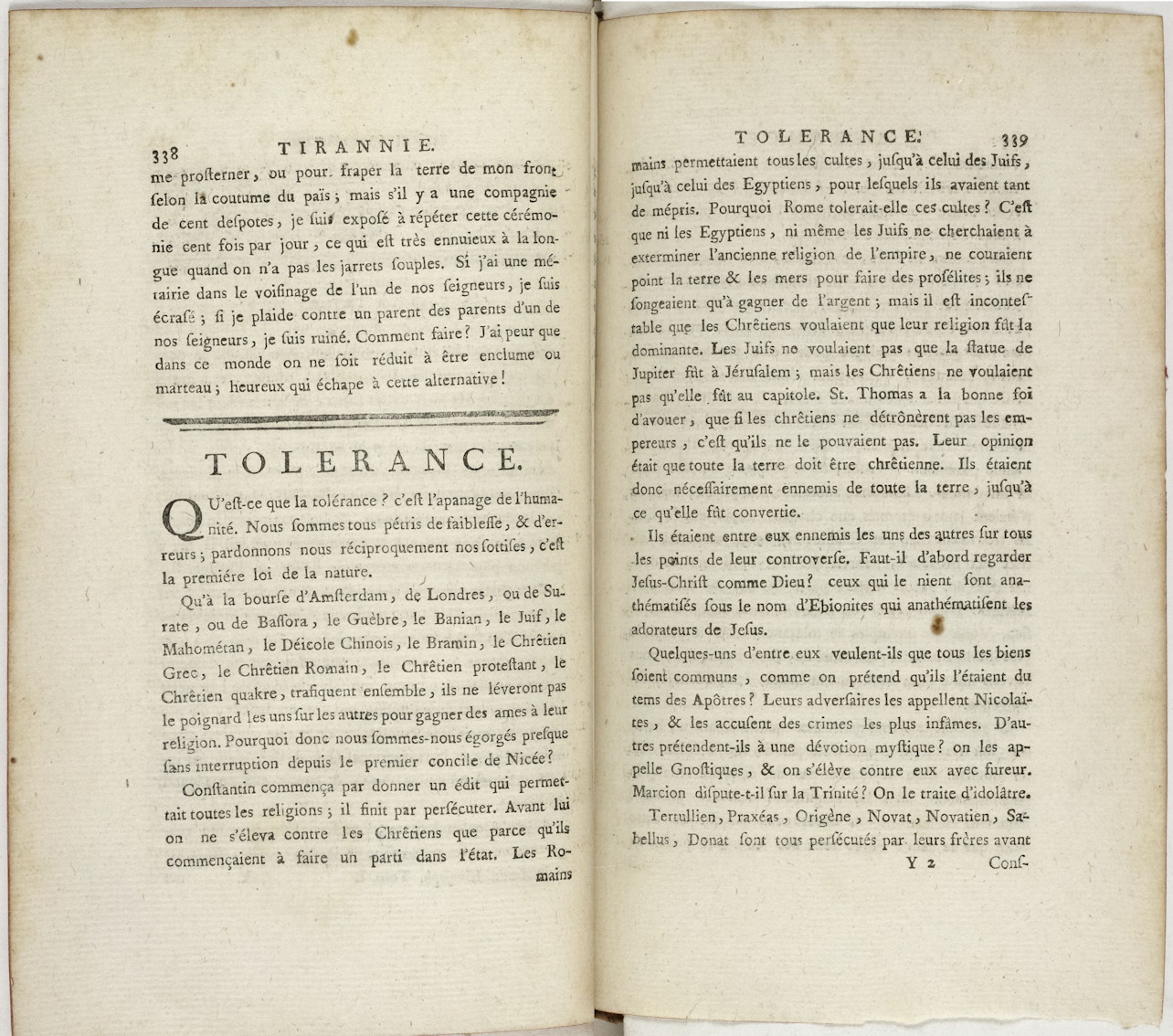

" What is tolerance ? It's the prerogative of humanity. We're all full of weaknesses and mistakes let's forgive each other our foolishness, it's the first law of nature. " (P. 235.)

The article Tolerance in the Dictionnaire philosophique opens with a contradiction : if tolerance is " the prerogative of humanity ", it is as a social value, as a regulating principle of civil administration that it must be instituted. Man ceases to be a savage, becomes properly a man, when he institutes tolerance. The model for this institution, never explicit in the Dictionnaire philosophique, is the Edict of Nantes1.

But if tolerance is " the first law of nature ", we need to completely reverse the reasoning : before any form of social state, before any civil contract, tolerance comes under natural law it is a principle of nature, which the barbarity of men distorts. To establish tolerance is to return to its origins, to restore " the first law of nature ". Because tolerance is natural, unlike an Edict, it cannot be revoked.

The notion of tolerance is therefore characterized from the outset by profound instability : it is an origin and it is an end it is an institution and it is a principle. Finally, this " prerogative of humanity " threatens to turn into its opposite. Indeed, doesn't Voltaire assert, in the chapter " De l'Inde " of the Philosophie de l'histoire, " que le fanatisme et les contradictions sont l'apanage de la nature humaine2 " ? These two contradictory prerogatives of humanity could be one and the same, characterized by the perpetual reversal of tolerance into its opposite fanaticism.

Tolerance and fanaticism : an inseparable couple

This reversal is explicit at the end of chapter XIII of the Traité sur la tolérance, where Voltaire takes as an example, but also as an explanatory model, Judaism caught in the contradiction of its laws and its practice, its principles and its history :

" In a word, if one were to examine Judaism closely, one would be astonished to find the greatest tolerance in the midst of the most barbaric horrors. It's a contradiction, it's true almost all peoples have been governed by contradictions. Happy is the one that brings about gentle morals when we have laws of blood ! " (GF, p. 99.)

Tolerance is born in the midst of " the most barbaric horrors " ; the " laws of blood " are inexplicably reversed into " gentle morals ". Voltaire has no discourse on tolerance, no circumscribed, isolated, philosophical notion of tolerance. What Voltaire points to, what he returns to again and again, is the couple, the polarity, the historical and living contradiction that tolerance and fanaticism form.

The idea of a Voltairean discourse on tolerance, widespread in Voltairean criticism, could therefore be no more than a pious myth, a reconstruction, a soothing simplification of Voltairean thought, which we have emphasized was inhabited, haunted, fascinated in the most troubled way by the spectacle of barbarism and human horror. There is no /// Voltaire, or at least not essentially, good feelings. It is in the spasm, the horror, the nightmare visions that historical investigation provides, that the demand for tolerance manifests itself, with the uncertainty of knowing whether this demand is that of a return to nature or of civilizational progress.

This uncertainty is the mark of a Voltairian unthought. Voltairian writing is trapped in this semiotic arc3 of absurd horrors from which it seeks to emerge through the establishment of a discourse, the construction of a treatise that never happens.

There is no Voltairian treatise on tolerance. The Traité of that name, published in 1763, is motivated conjuncturally by the Calas affair it opens and closes with its account. Its content, its unfolding, is a history of intolerance the theoretical demand falls back into the compulsion of history the promotion of a value turns into the haunting of its opposite. It's not a treatise it's a conjuration.

Tolerance like the Bourse : Voltaire's liberal economic model

The article Tolérance in the Dictionnaire philosophique is part of this movement. Voltaire wrote a first, rather short, article in the first edition, of 1764 this is section I, whose introductory table, set up as a theoretical model, is that of the world network of Stock Exchanges.

" Whether on the stock exchange of Amsterdam, London, or Surat, or Basra, the Gebre, the Banyan, the Jew, the Mohammedan, the Chinese deicole, the Bramin, the Greek Christian, the Roman Christian, the Protestant Christian, the Quaker Christian trade together : they will not raise the dagger on each other to win souls to their religion. Why then have we slit each other's throats almost without interruption since the first Council of Nicea ? " (P. 3754.)

Voltaire, who adheres and will increasingly adhere to a liberal conception of society, takes the economic sphere of trade as a model for the political foundation of tolerance. The private, bourgeois, mercantile sphere of the stock exchange is opposed to the public space of representation5 constituted by the church and councils. Traders on the Stock Exchange are not concerned with " winning souls for their religion " and are tolerant for this reason ; in the same way, the ancient Egyptians and Jews " were only concerned with making money ". The competition of the two gains (" to win souls ", " to win money ") constitutes the armature of Voltairean discourse.

Voltaire reminded us, in chapter III of Traité sur la tolérance, that the " idea of reform in the 16th century " was first and foremost a story of big money :

" Pope Alexander VI6 had publicly purchased the tiara, and his five bastards shared the benefits. [...] To pay for his pleasures, Leo X trafficked in indulgences as one sells commodities in a public market. [...] When annates7, trials in the Court of Rome, and dispensations that still exist today, would cost us only five hundred thousand francs a year, it is clear that we have paid since Francis I, in two hundred and fifty years, one hundred and twenty-five million. [...] We can therefore agree without blasphemy that the heretics, in proposing the abolition of these singular taxes which posterity will be astonished at, were not doing the kingdom any great harm, and that they were rather good calculators than bad subjects. " (GF, pp. 43-44.)

The trade in indulgences takes the form of a /// stock market transaction, " as one sells commodities in a public market ". The Stock Exchange is thus both the model of tolerance and the model of ecclesiastical corruption.

Spectrality of tolerance

The foundation, or economic model, of tolerance is, moreover, in a way no more than a historical lure : Voltaire does not rely on it to theoretically develop an alternative model of society.The economic basis is entirely negative: it destroys the public space of representation, of which the Catholic Church is the master builder; it indicts the political sphere, but without proposing any alternative, except in the vague form of complaint, imprecation or wishful thinking. Thus, at the end of Torture :

" Woe to a nation which, having long been civilized, is still led by ancient atrocious usages ! " (P. 384.)

Or this parable, which concludes the Dogmes article:

" When all these trials were emptied I then heard promulgate this ruling :

"By the Eternal Creator,

Conservative, remunerative,

Venger, forgiver, etc. etc.

be it known to all the inhabitants of the hundred thousand million billion worlds it has pleased us to form, that we will never judge any of said inhabitants on their hollow ideas, but only on their actions ; for such is our justice."

I confess that this was the first time I had heard such an edict : all those I had read on the little grain of sand where I was born ended with these words : For such is our pleasure. " (P. 170.)

The form of the edict, the very term, which Voltaire does not advance at random, refers to the implicit, informal model of the Edict of Nantes, which it would not be political to mention by name since its revocation in 1685, confirmed by Louis XV in the declaration of 1725. The Dogmes article relates a nightmare of Voltaire's the Edict of Toleration that closes it is one of its ghosts.

Tolerance is not about reality. It's an injunction that comes from outside, like the Code drawn up by Catherine II for her empire, and which Voltaire receives by post. He refers to it in the article Torture :

" The Russians passed for barbarians in 1700, we are that in 1769 ; an empress has just given this vast state laws that would have done honor to Minos, Numa, and Solon, if they had had enough wit to invent them. The most remarkable is universal tolerance " (p. 383)8.

It is from the confines of the civilized world, from the barbaric periphery of Europe, that the model of the law is constituted, like an injunction.

Tolerance always manifests itself in this polarity, in the mysterious couple it forms with barbarism. Always, the discourse on tolerance falls back into the history of intolerance. The 1764 article Tolérance, after its inaugural overview of the world's different exchanges, unfolds in three characteristic phases: Voltaire first castigates the intolerance of early Christians9 ; he then develops the paradoxical tolerance of the Jews10 and concludes with a discussion of the contradictions in Francis I's policy towards the Reformed11.This article takes up the main elements of the Traité sur la tolérance, but modifies its orientation it is the Calas affair that motivates the Traité and it is the question of Protestants that constitutes the Traité. /// the framework and the issue. In the Treaty, tolerance is a negative principle, according to which one must refrain from..., not interfere with..., let believe..., thus preserving that private sphere that public power, the state apparatus is so often tempted to want to control. The tolerance of the Treaty is not political ; it is even anti-political, precisely below the Edict of Nantes which constitutes its spectre, in the manner of the spectre of communism whose haunting Marx points to at the beginning of the Manifesto of the Communist Party (1847)12.

Conjuring theme and working with negativity

For Voltaire, as for Marx with communism, it's a contradictory matter of establishing tolerance and conjuring the spectre of the Edict that haunts the political sphere. From this perspective, the Traité sur la tolérance can be seen much more as a Manifesto than as a Treaty, that is, as a passage from the hidden, the spectral, to the formulated, the manifest, as a reversal of the spectral haunting into a rational proposition. This reversal involves an intense work of negativity, particularly clear in chapter IV of the Traité sur la tolérance, " Si la tolérance est dangereuse, et chez quels peuples elle est permise " :

" I do not say that all those who are not of the prince's religion13 must share places and honors with those of the dominant religion14. In England, Catholics, viewed as attached to the party of the pretender15, cannot reach jobs16 : they even pay double tax ; but they also enjoy all the rights of citizens. " (GF, p. 49.)

The edict of tolerance Voltaire calls for here, drawing on the English model, is introduced by a double negation : " Je ne dis pas que tous ceux qui ne sont point de... " The model evoked is itself a negative model : tolerated English Catholics are a kind of antithesis representation of persecuted French Protestants. The affirmation of English tolerance itself begins with a negation they " can't get jobs ", and so much the better. A few pages later, Voltaire develops this negative picture:

" We know that many heads of families, who have raised great fortunes in foreign countries, are ready to return to their homeland they ask only for the protection of natural law, the validity of their marriages, the certainty of their children's status, the right to inherit from their fathers, the frankness of their persons no public temples, no right to municipal offices, dignities : Catholics have none of these in London or in many other countries.It is no longer a question of giving immense privileges and places of safety to a faction, but of allowing a peaceful people to live, of softening edicts that were once perhaps necessary, but are no longer so. It is not up to us to indicate to the ministry what it can do it is enough to implore it for the unfortunate. " (Pp. 55-56.)

It's clear once again that the Edict of Nantes haunts this text, that it is the spectre that Voltairian speech intends to conjure, i.e. both recall to presence and send back in peace17 : the guarantee of " public temples ", the " right to municipal offices ", " places of safety " /// are the substance of the Edict of Nantes, reduced to presence by Voltairian formulation. But Protestants do not ask for this substance : " they nedemand que... " ; " point of temples " ; " point of right ".

These hunted and wealthy Protestants (" who have raised great fortunes in foreign countries "), that is, who accuse us and tempt us, are posted close to Voltairian speech, like him on the bangs of the kingdom. Like the spectres we conjure, they are " ready to return ". Like the spectres we conjure, they are crossed out by the negative formulation that evokes them : " il ne s'agit plus ", " qui ne le sont plus ". Carried along in his own movement, Voltaire includes himself in this spectralizing denial : " Ce n' est pas à nous à indiquer au ministère ce qu'il peut faire ". Yet this is indeed, in the most concrete and precise way, what the Traité does, but this program of tolerance manifests itself there spectrally, through history, as an immanent injunction of which Voltaire is, as it were, only the spectator.

Emergence of a value

Of course, there's a tactical prudence here that imposes moderation to reassure not only Catholic opinion, but the absolutist exercise of power. But it's not just a matter of calculation: if tolerance's mode of being in the Voltairean Traité is that of the spectre, it's because, in a way, we're witnessing its birth as a value : a few years later, when Catherine II disseminates her nakaz throughout the Europe of the Enlightenment, in which " universal tolerance " is proclaimed, the situation will be quite different18.

With the Dictionnaire philosophique, the Protestant question ceases to be the heart and central issue of the discourse, while polemical acrimony increases. The empowerment of tolerance as a positive value requires a globalized vision of the religious question. The planetary mosaic of religions forms the basis of the discourse: it's with this that the article Tolérance opens, evoking the Bourses du monde ; but it's also with this that it closes, in the fiery peroration that first summons all the wise men of the world, then all the religious minorities against the " insensés ", the " malheureux ", the " monstres " of fanaticism :

" Fools, who have never been able to give pure worship to the God who made you ! Wretches whom the examples of the Noachides19, the Chinese scholars, the Parsis and all the sages could never lead ! Monsters, who need superstitions like crows need carrion ! We've already told you, and we have nothing else to tell you if you have two religions, they'll cut each other's throats if you have thirty, they'll live in peace. Look at the Great Turk: he governs Gebras, Banians, Greek Christians, Nestorians and Romans. The first one who wants to stir up an uproar is impaled, and everyone is quiet. " (P. 377.)

Tolerance here becomes a principle of government. It is no longer simply an economic model of prosperity it is imposed as a principle of order, as a guarantee of public safety. But at the same time, a sadistic imaginary unfolds that is not confined to the opposite pole of the semiotic arc, to intolerance and fanaticism. Certainly, the intolerant are the monsters : " Monsters, who need superstitions like crows' gizzards need carrion ! "

.Tolerance and devouring

Voltairean writing draws its energy /// in this imaginary of devouring, where a strange metonymic game is at work. The gizzards of fanatical crows feed on superstitions, not victims it's not the persecuted, it's the very source of persecution that it devours. In a letter to M. Bertrand dated March 26, 1765, Voltaire also writes :

" I don't know when the persecuting spirit will be sent back to the depths of the underworld, from which it has emerged ; but I do know that it is only by despising the mother that one can overcome the son ; and this mother, as you well understand, is superstition. "

No doubt a year apart and in a different context Voltaire is not obliged to remain consistent in his metaphorical play. It's clear, however, that the monsters in the article Tolérance, the carrion crows and " l'esprit persécuteur " refer to the same thing, while superstitions are sometimes referred to as carrion crushed in the crows' gizzards, sometimes as the crows' mothers. In this imaginary of devouring, it is the mother who is targeted " it is only by despising the mother that one can overcome the son ". The profanation, the devouring of the mother is identified with the height of horror, which, through tolerance, must be conjured up, that is, once again, not simply avoided, but, in the same contradictory movement, made to appear and disappear, to summon and repel.

This contradiction is evident in Voltaire's depiction of the muscular tolerance practiced by the Grand Turk in his vast empire : " The first who wants to excite tumult is impaled, and everyone is quiet. " The impaled fanatic succeeds the carrion in the gizzard of the crows but did the impaled deserve such a torment ? The Voltairian trait and the irony of the clausule turn the meaning around in extremis: it's clear that neither Voltaire nor his reader subscribe to the policy of torture practiced by the Great Gate. The impaled victim identifies Turkish tolerance with cruel despotism, superimposing on the specter of fanaticism a fleeting and unexpected specter of tolerance.

Fanatical horror thus appears as the imaginary foundation from which tolerance emerges as a value and never ceases, in the Dictionnaire philosophique, to emerge, without ever definitively constituting itself as a discourse. This is why the theoretical discourse constantly announced, summoned, even begun, always falls back on the history that constitutes its imaginary reverse side and principial matrix.

Early Christian intolerance

The order of historical discourse is significant in this respect. In the Treaty on Tolerance, the Protestant question, and therefore the history of Francis I and the Reformation, were first. In the article Tolérance in the Dictionnaire philosophique, François Ier comes last, while Henri IV, the King of the Edict, but also the epic figure of the Henriade, is carefully avoided20.

The first to be summoned are Christians, who are the great absentees from the Traité sur la tolérance : Voltaire denounced the imposture of martyrologies and the absurdity of martyrdom stories21. He reread the Gospels to show that Jesus Christ had never prescribed intolerance22. But never were Christians taken to task as such, as a globally guilty community, and guilty from the very beginning. Here again, in the Dictionnaire philosophique, we observe a radicalization of the proposition.

" Constantine began by giving an edict that allowed all religions ; he ended by persecuting. " Constantine's edict of tolerance23 degenerated into persecution. In Voltaire's words, it was an edict without a name, a vague " edict that allowed all religions " : from the outset, Christians attacked " the ancient religion of the empire " and constituted " a party in the state ". Voltaire sums things up with an image, which is also a double negation :

" The Jews did not want the statue of Jupiter to be in Jerusalem ; but the Christians did not want it to be in the Capitol. " (P. 375.)

Christians are the foundation of the political institution, yet they wished to dethrone the emperors. The question of tolerance is therefore directly linked to the political order, contrary to what the more moderate discourse of the Treaty asserted.

Christian intolerance is also the ferment of political discord : in the second section of the article Tolérance, added in 1765, Voltaire is clear :

" This horrible discord, which has lasted for so many centuries, is a very striking lesson that we must mutually forgive each other our errors discord is the great evil of the human race, and tolerance is its only remedy. " (P. 379.)

Mutual forgiveness of errors refers immediately to the opening of the article Tolerance : " let us reciprocally forgive our foolishness " (p. 375). Christian discord is the ferment of ongoing political instability, which runs through the entire history of the Church Voltaire thus reverses the official discourse that justified the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in the name of the political unity of the kingdom. But the Christian discourse on martyrs is also targeted : Christians persecuted each other far more than they were victims of political authority.

.Jewish tolerance : Voltairian bricolage of the Traité sur la tolérance

The second summoned are the Jews. They occupied a central position in the Traité sur la tolérance : making tolerance a Jewish practice constituted a strategic argument. It meant making the historical and symbolic foundation of the Christian religion the historical and symbolic foundation of tolerance. Indeed, this strategy is clearly that of chapter XII of the Treaty, which begins by recalling all that God himself, through the intermediary of the Jews, has instituted (" One calls, I believe, divine right the precepts that God himself has given "), before enumerating the gods the Jews worshipped :

" Amos says that the Jews always worshipped Moloch, Remphan and Kium in the desert. Jeremiah expressly says that God asked no sacrifice of their fathers when they came out of Egypt. Saint Stephen, in his speech to the Jews, expresses himself as follows : "They worshipped the host of heaven ; they offered neither sacrifices nor hosts in the wilderness for forty years they bore the tabernacle of the god Moloch, and the star of their god Rempham24." " (GF, p. 90.)

From the idolatry of the Jews in the Desert, Voltaire infers a practice of tolerance that it is a matter of erecting into principle :

" Other critics infer from the worship of so many foreign gods that these gods were tolerated by Moses, and they cite as proof these words from Deuteronomy : "When you are in the land of Chanaan, you will not do as we do today, where everyone does what seems good to him." " (Ibid.)

The superstitions of the Jews, their idolatry, become a different and tolerated religious practice in the time of Moses, then a tolerance on the part of the father of the Law from which Voltaire cobbles together, builds the biblical guarantee of Moses, and, from there, by slippage, a biblical principle of /// tolerance.

This strategy is no longer that of the Dictionnaire philosophique, which no longer seeks to biblically, religiously, endorse tolerance. By positivizing itself as a value (and no longer as mere moderation, as a negative practice, as a limitation of barbarism), tolerance opposes religion, which it claims to organize, regulate, and ultimately symbolically depose.

Tolerance as adjustment

The article Dogmas

In the article Dogmes (p. 169), Voltaire recounts how two years earlier, in 1763, he was " transported to heaven ", where he saw a kind of tribunal where each death pleased its cause.

Charles de Guise (1524-1574), Cardinal of Lorraine and leader of the Catholic party in France since 1563, is considered by Voltaire to be one of the instigators of the Saint-Barthélémy25, According to Brantôme, "as ecclesiastic as he was, his soul was not so pure, but quite smeared" by his gallant adventures26. When he asks for eternal life as a reward for his involvement in the Council of Trent27, his female conquests and his League accomplices28 " appeared around him " like accusing shadows.

Then comes Calvin (1509-1564), the Geneva reformer, who boasts of having vituperated against the arts and, through his doctrine of grace, destroyed the idea of a remunerative God : " I have made it evident that good works serve no purpose at all ". Calvin was faced with a spectre:

.

" As he spoke, a flaming pyre was seen near him ; a ghastly spectre, wearing a half-burnt Spanish strawberry around its neck, emerged from the midst of the flames with dreadful cries. Monster," he cried, "execrable monster, tremble! Recognize this S... whom you destroyed by the cruelest of torments, because he had disputed with you about the way in which three people can make a single substance".

Michel Servet (1511-1553) was a Spanish humanist. A physician in Vienne, Isère, he discovered the circulation of blood ; " but he neglected a useful art for dangerous sciences29 " : in 1531, he published in Latin Seven books on errors concerning the Trinity30 in which he challenged this dogma ; then he entered into an epistolary controversy with Calvin on the subject. Calvin treacherously obtains the leaves of a clandestine work Servet was preparing and sends them, along with the letters received, to the Lyon Inquisition. Servet was arrested, escaped and fled to Geneva, where he was burned alive by order of the Calvin-controlled Grand Council on October 27, 1553.

.Jean Calvin " asked for the tolerance he needed for himself in France, and he armed himself with intolerance in Geneva31 ". He " who boasted, in his coarse patois, of having kicked the papal idol32 " is then himself in a way overthrown by this specter that accuses him. God's tribunal is a stage on which intolerance is displayed, along with the parade of theological discourse. The demand for tolerance is not signified here by a discourse against dogmas, against intolerant discourses it manifests itself at the meta-level of the device, by the setting in competition of these discourses. The demand for tolerance is in a sense programmed /// as soon as you enter the article, with the " s " of Dogmes.

There is no unity, no smooth surface to tolerance, but a misalignment, a dejoining, a disassembling of, discourses, by which it expresses itself as a demand for restoration. The expression of this demand, which arises in the cracks, fissures and silences of theological discourse, manifests itself as a spectre. The spectre of S... designates the ghost of Michel Servet, but also embodies, more essentially, the S... of the spectre, which manifests the fundamental spectrality of tolerance.

Tolerance arises as a demand from the ghost of the dead : the ghost of S... facing Calvin ; the ghost of C... facing the Cardinal of Lorraine (and C... can be read as the rest of Cardinal) ; the ghost of the Cardinal facing Voltaire in the grip of the nightmare of February 18, 176333.

The spectres of Calas

But the first specter is that of Father Calas, whose conspiracy is what's at stake in the Traité sur la tolérance :

" if an innocent father of a family is delivered into the hands of error, or passion, or fanaticism ; if the accused has no defense but his virtue : if the arbiters of his life have nothing to risk in slitting his throat but to be mistaken if they can kill with impunity by a decree, then the public outcry rises, everyone fears for himself, we see that no one is safe from his life before a tribunal erected to watch over the lives of citizens, and all voices unite to demand vengeance. " (GF, p. 31.)

It's a " father of a family " who must make amends for the murder, and this reparation does not involve the order of discourse. The " hands of error, or passion, or fanaticism " to which Calas has been delivered are nameless hands, hands of nightmare against which it is impossible to defend oneself. Against these hands rises " the public cry ", " voices" that " gather to demand vengeance " : a conspiracy is brewing, vague, as disturbing as the first injustice. Voltaire's concern is deliberate: when the courts no longer dispense justice, only vengeance remains. These conjured voices of the public, immaterial, anonymous, inarticulate, pose, at the threshold of Traité sur la tolérance, the presence of spectres.

The first chapter of the Traité is inhabited by the implicit image of the Erinyes : " Spirits once moved do not stop. " (P. 33.) This time it's the fanatical Catholic rabble. Between " grande pompe " and " profanation ", the burial of the Calas son is yet another manifestation of spectres, staged by the white penitents wearing " a sheet mask pierced with two holes to leave the view free " :

" Above a magnificent catafalque, a skeleton was raised and moved, representing Marc-Antoine Calas, holding in one hand a palm, and in the other the quill with which he was to sign his abjuration of heresy, and who was indeed writing his father's death warrant. " (GF, p. 34.)

The expiatory ceremony of this burial superimposes all the conjurations : conjuration of the white penitents provoking, maintaining the collective hysteria conjuration of the heresy, which Marc-Antoine had to abjure conjuration of his father's death, which the Toulouse street now demands. The skeleton puppet is supposed to both repel heresy and provoke condemnation he seals, through this double horror, the collective and spectral outline of the conjuration.

To promote tolerance is to conjure this conjuration. Tolerance is a conjuration of conjurations, as the specters it enacts are generated recursively, as successive horrification in the face of precedent. The /// recursive virtualization of the fanatic constitutes the principle of the demand for tolerance, which is both a demand for justice for the dead and a demand for a return to justice for the living. This demand arises as a symbolic principle34 ; it arises spectrally in the community, in the public ; it manifests itself as a supplement to a Voltairian discourse of tolerance that cannot be held.

Shakespeare, Heidegger, Derrida

This spectrality of tolerance, which demands justice in the cry35, but short-circuits revenge, takes us back to Jacques Derrida's analysis in Spectres de Marx (Galilée, 1993). This meditation based on the collapse of communism is dedicated to Chris Hani (1942-1993), Secretary General of the Communist Party of South Africa since 1991, and one of the leaders of the ANC, assassinated on April 10, 1993 outside the door of his home in the suburbs of Johannesburg, on the orders of an English-speaking MP from the Conservative Party of South Africa who sought to thwart the peace and reconciliation process.

>Derrida is no more a communist than Voltaire, defending Calas, was a Protestant. Spectres de Marx starts from Act I, Scene 5 of Hamlet. The ghost of Hamlet's murdered father appears to him, demanding vengeance for the murder he suffered. Hamlet then asks Horatio and Marcellus, his companions, to swear silence about what they have seen. The Spectre then cries out from under the stage:

Hamlet's companions, Horatio and Marcellus, swear silence about what they have seen.

" Ghost cries under stage.

GHOST

Swear ! "

Hamlet changes places several times to swear his companions away from the specter, who always returns with his injunctive cry, Swear !, which ominously displaces the meaning of the oath : if Hamlet asks to swear silence, it's for vengeance that the specter demands an oath. This superimposition of two oaths - the one demanded by the specter and the one requested by the young prince - constitutes the spectral device. Derrida identifies the contradictory double meaning of the conjuration, which on the one hand returns the specter to the silence of his tomb, and on the other awakens the specter to demand justice and exact vengeance. Hamlet concludes the scene with an enigmatic formula:

Hamlet, the specter, is the only one of his kind in the world.

" The time is out of joint. O cursed spite

That ever I was born to set it right ! "

(O cursed spite

That ever I was born to set it right ! Who wants me to be born to set it right36.)

This is not a story about tolerance ; but it is indeed the moral, political, metaphysical function of the spectrum, which Voltaire will summon and implement to think about tolerance. It's a question of noting, of pointing out the disjointedness of the present, the out of joint. From this observation arises, emerges the demand that justice be done, that this present be joined, straightened, set straight, to set it right.

To comment on Shakespeare, Derrida summons a text by Martin Heidegger, " La parole d'Anaximandre " : commenting on a fragment by this pre-Socratic philosopher37, Heidegger introduces the notion of disjointure (Un-Fuge) to think the articulation between Justice and Injustice and, beyond that, between Presence and Absence :

" Insofar as it is thought from being as presence (als Anwesen gedacht), Dikè harmoniously conjoins, as it were, joint and agreement. Adikia on the contrary : at once that which is disjointed, dislocated twisted and outside the law, in the wrong of the unjust, even in stupidity38. "

Here we are, back at the heart of Voltairean preoccupation : starting from the general picture of adikia, which is not only injustice, intolerance, superstition, fanaticism, but manifests itself above all as disjoinment, dislocation of discourse39, and ward off this dislocation, this adikia, straighten out the saying, say the right, and say it straight.

The article Theologian

This is the concern of the theologian in the article Theologian, which immediately precedes, in the Dictionnaire philosophique, the article Tolerance. The theologian is a master of discourses :

" I have known a true40 theologian ; he possessed the languages of the East, and was instructed in the ancient rites of the nations as far as one can be. " (P. 374.)

Contrary to the caricatured sectarians who populate the Dictionary philosophical, such as Logomachos in the God article, or Bambaref in the Fraud article, the true theologian does not hold one discourse, but claims to assume the totality of theological systems, to reconcile them, adjust them, fit them together, smooth them.

" The Brahmans, Chaldeans, Ignatians, Sabaeans, Syrians, Egyptians were as well known to him as the Jews the various lessons of the Bible were familiar to him he had for thirty years tried to reconcile the Gospels, and attempted to tune together the Fathers. " (Continued from previous.)

" Concilier ", " accorder ensemble " : this not only distinguishes the activity of the exegete, from a Dom Calmet, for example, whom Voltaire perhaps portrays here, less sarcastically, but just as critically as usual. To reconcile, to reconcile points to the present reality of the disjointing, the misalignment of discourses. What the theologian confronts is the out of joint of time, these are the cracks, these solutions of continuity from which, from reality, filters the demand for tolerance that is at the same time the demand for justice and the demand for rationality, what Voltaire calls " l'esprit philosophique41 ".

Facing the theologian stands the bariolure of discourses, and this bariolure enters into violent discord with the unity, the rational continuity of straight discourse. Between the clash of cultures, in the sphere of reality and time, and the rational demand for discursive homogeneity is created the constitutive tension, the semiotic arc through which the denial of tolerance turns into a demand.

.This semiotic arc is inscribed in temporality. The time is out of joint. Not this time, this time, present time, but the time, temporality in general, is constituted by the experience of this disharmony, this disjoint. This is why the theologian's research is a historian's research, that is to say, an experience of temporality, or more precisely of temporality's resistance to rationality.

" He sought in precisely what time the symbol attributed to the apostles, and that which is put under the name of Athanasius ; how the sacraments were instituted one after the other ; what was the difference between the synaxis and the mass how the Christian Church was divided from its birth into different parties, and how the dominant society treated all the others as heretics. " (Continued from previous.)

The theologian's historical research turns his attention to the beginning of things. It is a search for origins and, in each origin, the identification of a dejointing, /// It's no longer dom Calmet who's doing the research, but Voltaire himself, Voltaire who is simultaneously, in the same movement of thought, working as a theologian, historian and polemicist, fulfilling, as it were, the medieval tradition of exegetical activity to its ultimate conclusion. The enterprise of theological knowledge is a search for origins : origin of the symbol42, of the sacraments43, of the Mass44, of divisions in the Church45.

But every origin is a discord. The institution of rites, the history of this institution, make the, differences appear and play out: difference of the Apostles' symbol and Athanasius' symbol, disparity of the sacraments instituted " one after another ", division of the Church " into different parties ", distinction " between politics and wisdom ".

.

The highlighting of these differences is a dejoining of temporality ; it manifests the adikia of History, i.e. the absurd, incomprehensible character of every institution, of every origin. This depression of the adikia calls for, demands a return of the dikè, a rejointement, a return of the dikè, a rejointement, a return of right discourse, of law. It is in this return, which starts from the origin of institutions, but points towards the achievement of civilization, it is in this spectral return, then, that tolerance is inscribed, manifested.

Tolerance is a spectral return that takes place against a backdrop of temporal disjunction. So it's not simply a matter of readjusting the discourse: it's not enough to put things back in order, to rationalize things a little. We need to respond to a spectral, ancestral demand for justice: there are many dead, paternal deaths that demand justice. Between adikia and dikè, between justice and law, between what triggers the demand for tolerance and what responds, necessarily on another level, to this demand, there is a hiatus, a discordance. It doesn't answer where it was asked : this is the problem of tolerance, a matter of specters, conscience, intimacy and ethics brought to the light of the public sphere, in a place whose rationality and publicity deny the haunting of specters and misunderstand the secret wounds of intimacy.

This hiatus, this discordance of the adikia and the dikè, Voltaire's " true theologian " experiences it :

" He probed the depths of politics, which always meddled in these quarrels ; and he distinguished between politics and wisdom, between the pride that wants to subjugate minds and the desire to enlighten oneself, between zeal and fanaticism.

The difficulty of arranging in his head so many things whose nature is to be confused, and of throwing a little light on so many clouds, often put him off ; but as these researches were the duty of his state, he devoted himself to them in spite of his disgusts. " (Continued from previous.)

This moment in the Theologian article is crucial, as it consecrates the tipping of history into politics. The spring of the theological unjoining of temporality is political : it's because what's at stake in every institution, in every theological discourse, is political, that necessarily gets involved in quarrel, dispute, by which time gets out of its hounds, not conjuncturally, but structurally.

On the one hand, the theologian observes a reality /// mingled : a mishmash of cultures, " various lessons from the Bible ", multiple and contradictory Gospels and Fathers, but above all mingled theology and politics (" the politics that always mingled... "). On the other hand, his work consists in introducing, into this mixed reality, a logical order, the rationality of a discourse : " he distinguished between... "

But this discursive distinction, which fixes difference instead of resolving it, which responds to discourse with discourse, fails. The difference that discourse seeks to assume dwindles, dissolves in the very moment it formulates it. If " the wisdom " of the tolerant is opposed to " the politics " of the intolerant, if " the desire to enlighten oneself " is opposed according to the same divide to " the pride that wants to subjugate minds ", what about zeal and fanaticism ? But zeal and fanaticism no longer refer to two distinct spheres (public vs. private, political vs. intellectual) they're really the same thing, the same activity from two points of view. The difference becomes blurred, the discourse rears its ugly head, the situation collapses. This theologian, so learned, so knowledgeable, who was able to unravel so many things, struggles to maintain a difference in his discourse that is impossible to control, to master. He had " tried to reconcile ", " tried to agree " ; he is now confronted with " the difficulty of arranging ". The object of his research rebounds him, and even disgusts him.

There's an abjection, a horror of dejointage, linked to the nightmare vision the spectre sends. What, in the disjointing of time, demands justice is the specter of fanaticism, since the specter combines in the vision it provides the horror suffered and the demand for reparation. This brings us to the limit of the theologian's ability to satisfy this demand: the re-establishment of right is not a matter of saying the theologian's discourse can only collide with that which rebuffs it, and ultimately fall from disgust to disgust, as the article's terrible conclusion underlines:

.

" At last he arrived at knowledge unknown to most of his confreres. The more truly learned he became, the more he distrusted everything he knew. While he lived, he was indulgent ; and at his death, he confessed that he had uselessly consumed his life. " (Continued from previous.)

Like the Marxist specter of communism, the Voltairian specter of tolerance haunts Europe both as a picture of desolation and as a promise of revolution and struggle.The theologian cannot set it right, restore the right, because he remains at the level of discourse and does not pass to the meta-level of device.To dispose of them, of discourses, a return of the real is necessary : this is the meaning of the Voltairian struggle, which makes tolerance a militant requirement and not the speculative object of a discourse, the promise of a commitment and not the material of a treatise.

Such a requirement passes through the dialogization of the Dictionnaire philosophique, as for example in the article Dieu, which opposes Logomachos, theologal of Constantinople, to the Scythian old man Dondindac (p. 163). Logomachos, the one who fights not speech, comes to eradicate paganism from the northern confines of the nascent Byzantine Empire. Logomachos carries the theological discourse with its illusion of totalizing continuity. Opposite him, Dondindac is the idolater who must be converted and instructed. The story of God is the failure of this conversion. Dondindac's name reflects the contempt of the educated theologal for the barbaric peasant among his turkeys. Logomachos catches Dondindac giving thanks at the end of a frugal meal. Dondindac's religion is not an idolatrous polytheism, as Logomachos accuses him, but deploys the /// A virtual, unreal picture of the natural religion dreamed up by the philosophers of the Enlightenment: a religion of the past, which preceded Christianity and which Christianity perverted, a religion of man's origins in the state of nature, it is also a model of what should be achieved, of the religion of the future to which the fight for tolerance is directed. As such, Dondindac's fiction is a spectral fiction, participating in the spectrality of tolerance.

This scene, this verbal joust between Logomachos and Dondindac, is impossible. It doesn't fit into any plausible temporality:

This scene, this verbal joust between Logomachos and Dondindac, is impossible.

" for the theologal knew a little Scythian and the other a little Greek. This conversation was found in the Constantinople library." " (Article Dieu, p. 164.)

These ironic details should be taken as markers of spectrality : Voltaire here delivers a fiction assumed as fiction. This is Voltaire's way of setting aside all facts, of situating himself outside discourse (there is no possible discursive communication) and outside time (there is no possible memory for such a scene, no possible library, no possible archive for such a conversation). The level of out-of-discourse and out-of-time is the fictional meta-level of the device by which Voltaire seeks to capture and represent tolerance. In this unlikely encounter, what is not yet a value makes an effort to emerge.

Notes

" And in order not to leave any occasion for disturbances and disputes between our subjects, we have permitted and allow those of the said religion claimed to be reformed to live and remain by all the towns and places of cestui our kingdom and countries of our obedience, without being questioned, vexed, molested or forced to do anything for the fact of religion against their conscience, nor for reason of icelle be searched in the houses and places where they will want to live, behaving in the rest as it is contained in our present Edict. "

The word " tolerance ", then extremely pejorative (in the sixteenth century, tolerance meant suffering), never appears in the edict. In 1685, the Edict of Nantes was revoked by Louis XIV. The expression "Edict of Toleration" refers to the Edict of Versailles promulgated by Louis XVI in 1787, which granted Protestants civil status. A step back from the Edict of Nantes, it officially recognized neither freedom of conscience nor freedom of worship.

" Enter the London Stock Exchange, that Place more respectable than many Courts : there you see assembled the deputies of all Nations for the utility of men.There, the Jew, the Mohammedan and the Christian deal with each other as if they were of the same Religion, and give the name of infidels only to those who go bankrupt the Presbyterian trusts the Anabaptist, and the Anglican receives the /// At the end of these peaceful and free assemblies, some go to the Synagogue, others go drinking this one goes to be baptized in a large vat in the name of the Father by the Son in the Holy Spirit this one has his son's foreskin cut off and has Hebrew words mumbled over the Child that he does not hear these others go to their Church to wait for God's inspiration, their hat on their head, and all are happy.

.If there were only one Religion in England, despotism would be to be feared if there were two, they would cut each other's throats but there are thirty, and they live in peace and happiness. " (Éd. Naves, Garnier, p. 29.)

In the Lettres philosophiques, Voltaire starts from the picture of the London Stock Exchange, where all Nations and religions spawn. In the Dictionnaire philosophique, the model has become more complex and globalized it is all the world's Stock Exchanges, in which all nations and religions trade, that weave the network, commercial, of universal tolerance.

"In a great empire which extends its dominion over as many diverse peoples as there are different creeds among men, the fault most harmful to the rest and tranquility of its citizens would be the intolerance of their different religions. Only a wise tolerance of orthodox religion and politics, equally avowed, can bring the lost sheep back to the true faith. Persecution irritates spirits tolerance softens them and makes them less obstinate it stifles those disputes contrary to the repose of the state and the union of citizens."

[...] I believed that it was the only practicable way to introduce the cry of reason, to support it on the foundation of public tranquility, whose need and usefulness every individual continually feels. "

Voltaire transcribes this passage from his letter in the first section of the Puissance article of the Questions sur l'Encyclopédie, which deals with " deux puissances ", the temporal and the spiritual. The Questions sur l'Encyclopédie add a third section to the Tolerance article, where Voltaire writes : " Let us always reflect that the first law of the Russian empire, greater than the Roman empire, is the toleration of all sects. "

In chapter X of Essai sur les mœurs, Voltaire details the reasons for his horror of this despotic and cruel emperor : " Constantine, who became emperor in spite of the Romans, could not be loved by them. It's obvious that the murder of Licinius, his brother-in-law, murdered in spite of oaths Licinian his nephew, massacred at the age of twelve Maximian his father-in-law, slaughtered by his order in Marseille his own son Crispus, put to death after winning battles for him his wife Fausta, suffocated in a bath all these horrors didn't soften the hatred they felt for him. " (Garnier, I, p. 298.) From private crimes, Voltaire then moves on to public massacres, perpetrated notably by Christians against their former persecutors.

One might think that the reasons for this Voltairian fixation against Constantine are linked to the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. On that occasion, Bossuet hailed Louis XIV as a "new Constantine". See Michel Le Tellier's funeral oration: "Let us pour out our hearts on Louis' piety.Let us raise our acclamations to heaven and let us say to this new Constantine, to this new Theodosius, to this new Marcian, to this new Charlemagne, what the six hundred and thirty Fathers once said in the Council of Chalcedon : You have strengthened the faith you have exterminated the heretics : this is the worthy work of your reign this is its own character. " Jesuit Le Tellier, chancellor of France and executor of the Edict of Fontainebleau, which revoked the Edict of Nantes, is /// one of Voltaire's Turks.

" Moloch, or Melcrom, god of the Ammonites. The name Moloch means king ; and that of Melchom, their king. Moses forbids in more than one place (Le 18:24; 20:2-5) the Israelites to consecrate their children to Moloch, making them pass through the fire in honor of this false god he wants to punish with death the one who will have contravened this ordinance and God threatens to stop the eye of his wrath on this man, and to exterminate him from the midst of his people. There's plenty of evidence that the Hebrews were devoted to the worship of this deity even before they left Egypt, since Amos (Am 5:26), and, after him, St. Stephen (Acts 7:43), reproach them for having carried into the desert the tent of the god Moloch. Portastis tabernaculum Moloch vestro. Solomon (1Ro 11:7) built a temple to Moloch on the Mount of Olives ; and Manasseh, long after, imitated his impiety (2Ro 21:3,4), making his son pass through the fire in honor of Moloch. It was mainly in the valley of Topheth and Hennon, to the east of Jerusalem, that the impious worship of Moloch was practiced by the Jews (Jer 19:5,6 Sop 1:4,5), who consecrated their children to him and made them pass through the fire in his honor. Calmet then asks what is really meant by " passing through the fire " : " we are convinced that, as a rule, the worshippers of Moloch immolated their children and caused them to die in honor of this divinity ". We're pretty far from tolerant here...

For Kium, see the Chion article, where Calmet explains that this is the pedestal of idols. The Remphan article identifies this God as either Saturn or a deified Pharaoh. Calmet also wrote a Dissertation on the idolatry of the Hebrews in the desert.

.On the other hand, although he was officially born on November 21, 1694, Voltaire claimed that his true date of birth was February 19, or 20 : his baptism would have been delayed, convinced as they were of the imminent death of such a sickly infant. See the letter to Damilaville of February 20, 1765 : " I enter today my seventy-second year, for I was born in 1694, on the 20th of February, and not on the 20th of November, as ill-educated commentators say. "

In his letter to Cardinal de Bernis of February 25, 1763, Voltaire concludes :" Agréez, monseigneur, les tendres respects du vieil aveugle de soixante-dix ans, car il est né en 1693. He is very weak, but he is very cheerful; he takes all the things of this world for bottles of soap, and frankly they are just that. " The night of February 18, 1763 was experienced by Voltaire as the night before his seventieth birthday... so much for his death !

In the same letter to Cardinal de Bernis, Voltaire solicits him to subscribe to the edition of Corneille he has prepared to endow Marie-Françoise Corneille : " L'ombre de Pierre vous sera très obligée, et moi, autre ombre, je regardai cette permission comme une très grande faveur. " The spectral device falls into place...

The wedding was celebrated by a Jesuit. On this occasion, Voltaire amused himself with a little masquerade, which he recounts to Damilaville :

" The day before yesterday there were two Jesuits at my house with a large company ; we played a parade, and here it is : I was monsieur le premier président I questioned my two monks ; I said to them : Do you renounce all privileges, all bulls, all opinions, either ridiculous or dangerous, that the laws of the state reprobate ? do you swear never to obey your general or the pope, when such obedience would be contrary to the interests and orders of the king ? do you swear that you are citizens before being Jesuits ? do you swear without mental restriction ? To all this they answered : Yes. And I pronounced : The court acknowledges your present innocence ; and making right on your past and future offenses, condemns you to be stoned on Arnauld's tomb with the stones of Port-Royal.

.I salute all the brothers ; however écr. l'inf... "

This parade may have motivated Voltaire's dream, or dream fiction, if we take " le 18 février de l'an 1763 " as an indication of when the Dogmes article was written.

The demand for rationality is not necessarily irenic, as evidenced by the conclusion of the Abbé article, which prophesies a veritable revolution : " You are right, gentlemen, invade the earth it belongs to the strong or the skillful who seize it ; you will /// have taken advantage of times of ignorance, superstition, and insanity, to rob us of our inheritance and to trample us underfoot, to fatten yourselves on the substance of the unfortunate : tremble lest the day of reason should come. " (Pp. 5-6.)

///Promulgated in 1598 by Henri IV to put an end to the Wars of Religion, the Edict of Nantes guaranteed Protestants unrestricted freedom of conscience throughout the kingdom of France and, under certain conditions, freedom of worship. This freedom of conscience is proclaimed in article VI of the edict, in the following terms :

Voltaire, Essai sur les mœurs, ed. R. Pommeau, Garnier, t. 1, p. 61. Published in 1765, the Philosophie de l'histoire then served as an introduction to the Essai sur les mœurs.

On this notion, see the November 5 essay correction.

Voltaire here repeats a development already present at the end of the 6the of the Lettres philosophiques : (1734) :

On this notion, see J. Habermas, L'Espace public, 1962, French trans. Marc B. de Launay, Payot, 1978, 1993.

Roderic de Borja, who became Rodrigo Borgia after his arrival in Italy, was pope under the name of Alexander VI from 1492 to 1503. A corrupt, nepotistic and bloodthirsty pope, he was also a generous and cultured patron of the arts. He fascinated Voltaire, who imagined in the first section of the Faith article in the Dictionary a dialogue between Alexander VI and the humanist Pico della Mirandola.

Annates were, since the 14th century, a tax levied by the Pope on ecclesiastical benefices, at each vacancy of the endowed see. The tax corresponded to one year's net income from the benefice. It was abolished by the French Revolution of 1789.

See also the Sermon preached in Basel, on the first day of the year 1768, by Josias Rossette

Compare with chapter X of the Treaty on Toleration, " Of the danger of false legends and persecution ".

Compare with chapter XII, " Whether intolerance was by divine right in Judaism, and whether it was always put into practice ", and with chapter XIII, " Extreme tolerance of the Jews ".

Compare with chapter III, " Idea of the 16th-century Reformation ".

The Manifesto begins thus : " A spectre haunts Europe - the spectre of communism. [Ein Gespenst geht um in Europa - das Gespenst des Kommunismus.] All the powers of old Europe have united in a Holy Alliance to hunt down this spectre : the pope and the tsar, Metternich and Guizot, the radicals of France and the policemen of Germany. Which opposition has not been accused of communism by its opponents in power? Which opposition has not, in turn, sent back the infamous epithet of communist to its opponents on the right or left? The result is twofold. Communism is already recognized as a power by all the European powers. It is high time for Communists to expose their conceptions, aims and tendencies to the whole world; to oppose the tale of the Communist spectre with a Party manifesto. /// itself. " The term spectrum (gespenst), which appears here four times, is never used again in the rest of the Manifesto.

" la religion du prince " refers to the doctrine cujus regio ejus religio (" tel prince, telle religion ", Joachim Stefani, 1612) : the sovereign of a country has the right to impose his religion on his subjects. This Protestant-inspired doctrine was first applied at the time of the Peace of Augsburg in Germany, in 1555. Each German principality adopted as its official religion that of its sovereign.

This was guaranteed by the Edict of Nantes.

" The Viscount of Bolingbroke, who had come to give peace to Louis XIV with a grandeur equal to that of this monarch, was obliged to come and seek an asylum in France, and to reappear there in supplication. The Duc, d'Ormond, the soul of the parti du prétendant, chose the same refuge. " (Voltaire, Siècle de Louis XIV, chap. XXIV.)

to employment, i.e. to public office.

" The French noun "conjuration" brings together and articulates the meanings of two English words. [...] Conjuration means on the one hand conjuration (its English namesake), [...] the magical incantation intended to evoke, to bring about by voice, to summon a charm or spirit. [...] Conjuration on the other hand means conjurement, namely the magical exorcism which, on the contrary tends to expel the evil spirit which would have been called or summoned " (J. Derrida, Spectres de Marx, " Injonctions de Marx ", pp. 73-84).

The nakaz was circulated in August 1767. But as early as her letter to Voltaire in early July 1766, Catherine wrote : " Here is word for word what I have inserted [...] in an instruction to the committee that will recast our laws [i. e. in the nakaz] :

Compare with the Traité sur la tolérance, chap. IV : " The government of China has never adopted, for more than four thousand years that it has been /// known, than the worship of the Noachides, the simple adoration of a single God " (GF, p. 51). There is an article Noachides in Dom Calmet's Dictionnaire: " This is the name given to the children of Noah, and in general to all men who are not of the chosen race of Abraham. The rabbis claim that God gave Noah and his sons certain general precepts, which, according to them, comprise the natural law common to all men indifferently, and the observance of which alone can save them. The notion of " noachide laws ", unknown in antiquity, is said to have been invented by Maimonides, then developed by certain rabbis, in order to avoid considering Christians and Muslims as idolaters.

Henri IV is the subject of chapter 174 of the Essai sur les mœurs, which is highly complimentary of him, but never mentions the Edict of Nantes by name.

Traité sur la tolérance, chap. IX " Des martyrs " and chap. X " Du danger des fausses légendes et de la persécution ".

Chap. XIV, " If intolerance was taught by Jesus Christ ".

In Milan in 313, Constantine concluded an agreement with Licinius to divide the Empire. Among the measures agreed was an edict of religious tolerance, usually referred to as the Edict of Milan. Under the terms of this edict, Christians were no longer discriminated against; their worship was authorized, and property confiscated from them was returned to them. The Christian religion was placed on an equal footing with other faiths. Constantine then came up against the Donatist schism. In 321, an edict of tolerance, while condemning their movement, allowed the Donatists to keep the churches they owned.Finally, Constantine was the promoter of the Council of Nicaea, in 325, which condemned Arianism and agreed on the first symbol, or credo of the Church. These events feature prominently in the Dictionnaire philosophique : see in particular the articles Arius, Councils, Credo. The Council of Nicaea is also discussed in the article Christianity, pp.129-130.

Voltaire probably got his information from Dom Calmet, who in the article Moloch in his Dictionnaire de la Bible writes :

" This awful day was meditated and prepared for two years. It is hard to imagine how a woman such as Catherine de Médicis, brought up in the lap of pleasure, and to whom the Huguenot party was the one that shaded her least, could have taken such a barbaric resolution. This horror is even more astonishing in a twenty-year-old king. The Guise faction had much to do with the enterprise..." (Essai sur les mœurs, chap. 171, Garnier, t. II, p. 494.) Charles de Guise was in Rome at the time of the massacre and it would seem that he had no part in it nothing, at the same time, gave him more pleasure.

Mémoires de Messire Pierre de Bourdeille, seigneur de Brantôme, A Leyde, chez Jean Sambix le jeune, à la Sphere, 1665-1666, 4 parts in eight volumes. The third part is entitled " Les Vies des Hommes Illustres & grands Capitaines François de son temps ". It contains a life of François de Guise, in which Brantôme relates this trait concerning his brother Charles.

Charles de Guise took part in the Council of Trent in 1563 and campaigned for the application of its decrees in France.

The League was actually founded in 1576, two years after his death. Henri, Duc de Guise, nephew of Charles, Cardinal of Lorraine, was its leader in Paris. Voltaire condenses... He draws his information probably from Bayle's Dictionnaire historique et critique, article Guise. Speaking of the Duc de Guise and his brother the Cardinal de Lorraine, Bayle writes: " It is therefore to these two brothers that we can impute all the misfortunes of the civil wars of that time. They opposed the freedom of conscience of Protestants, they fomented /// persecution, they fostered a bloodthirsty spirit in the kingdom, against the most essential and inalienable right that man can enjoy, and the one that sovereigns must regard as the most inviolable. " Bayle goes on to report how the two brothers were guilty of the Vassi massacre in 1562, unable to tolerate Protestants worshipping legally next to their Joinville castle.

Essai sur les mœurs, chap. 134, " De Calvin et de Servet ", Garnier, t. II, p. 244.

De Trinitatis Erroribus libri septem, per Michaelem Servetum, alias Reves, ab Arragonia Hispanum, anno MDXXXI, in-8°.

Essai sur les mœurs, chap. 134, p. 245.

Dictionnaire philosophique, article Dogmes, p. 169.

This date is enigmatic. The big event that occupied Voltaire at the time was the marriage of Corneille's great-grandniece, Marie Françoise Corneille, to a young neighboring gentleman from Ferney, Pierre Jacques Claude Dupuits, on February 13, 1763.

On the distinction between symbolic principle and institution, see S. Lojkine, Image et subversion, J. Chambon, 2005, pp. 91sq.

In 1769, Voltaire published Le Cri des nations on the occasion of the expulsion of the Jesuits ; in 1775, Le Cri du sang innocent, as a supplement to Relation de la mort du chevalier de La Barre.

J. Derrida here prefers Yves Bonnefoy's translation, 1957, Gallimard, Folio, 1992. See Spectres de Marx, pp. 43-44.

Anaximander of Miletus was a sixth-century pupil of Thales. Only a fragment of his work has survived, but his philosophy is also known to various commentators, including Simplicius. Anaximander reflects metaphysically on origin as apeiron (unbounded) and on the plurality of worlds, which appear and disappear in perpetual motion.

Spectres de Marx, p. 49. Derrida paraphrases " Der Spruch des Anaximander ", Holzwege (Paths that lead nowhere), Klostermann, 1950, p. 329.

In the Economy article of the Questions sur l'Encyclopédie, section " De l'économie publique ", Voltaire remarks : " It is evident that the more men and wealth there are in a state, the more abuses one sees there. Friction is so considerable in large machines, that they are almost always out of order. These disturbances make such an impression on people's minds, that in England, where every citizen is allowed to say what he thinks, every month there is some calculator who charitably warns his compatriots that all is lost, and that the nation is ruined without resources. English tolerance, which has brought public abundance and the free expression of opinions, manifests itself in an obsessive discourse on " the friction " of the economic machine, its " derangements ", on the fact that it is " deranged ". This is the discourse of the adikia, which is the discourse of the present as a disjointing of temporality.

From the outset, this qualifier introduces into the discourse a dejoining : a true theologian assumes that those we ordinarily call theologians are not true theologians. There are theologians and theologians. This true theologian will act as a lever against theologians, operating the disjoinment in the real, in the present time, that the practical injunction of tolerance, in the following article, should make it possible to rejoin. But the article Tolerance in turn unjoined, and so on...

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « La tolérance voltairienne, une conjuration de spectres », cours d’agrégation sur le Dictionnaire philosophique, Université de Provence, Aix-en-Provence, 2008-2009.

Voltaire

Archive mise à jour depuis 2008

Voltaire

L'esprit des contes

Voltaire, l'esprit des contes

Le conte et le roman

L'héroïsme de l'esprit

Le mot et l'événement

Différence et globalisation

Le Dictionnaire philosophique

Introduction au Dictionnaire philosophique

Voltaire et les Juifs

L'anecdote voltairienne

L'ironie voltairienne

Dialogue et dialogisme dans le Dictionnaire philosophique

Les choses contre les mots

Le cannibalisme idéologique de Voltaire dans le Dictionnaire philosophique

La violence et la loi