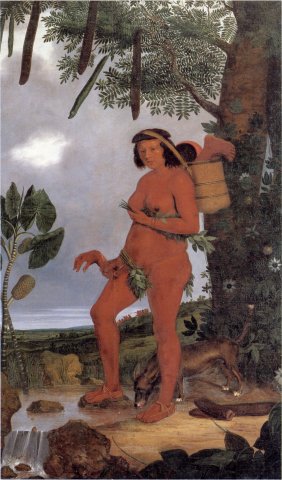

Albert Eckhout, Indian Tarairiu cannibal from Brazil, 272x165 cm, 1641, Copenhagen, National Museum, ethnographic collection

It may seem strange to speak of a negative dialectic in relation to a work as actively combative as the Dictionnaire philosophique : the internal and insidious work of negativity in the key notions of the symbolic edifice seems ill-suited to the frontal attack that the Portatif makes no secret of waging.

Paradoxically, however, the textual structuring movement at work here reveals a systematically indirect strategy. Polemical violence is rarely content with an indignant confrontation of Voltairian theistic creed with the ideological scandals of superstition and fanaticism. Faced with his target, Voltaire practices decentering rather than contradiction; he absorbs the discourse of the Other into his own. Violence emerges from within the discourse; it is the irruption of reality at the heart of the law that the satirist is aiming at. The strategy then reveals its reasons: for Voltaire, there is no symbolic outside, no external ideological framework on which to lean; the symbolic alternative can only be thought of from within the old law, whose irritating, ineradicable persistence Judaism represents. The proposed new model therefore recycles the old object that has been absorbed, the old law that has been violated. However, the recomposed father figure does not easily win back the legitimacy that the derision of its primitive form had undermined. Voltaire's ideological bricolage appears to be shaped by an inner emptiness, a foundational lack that fascinates and even, at times, anguishes. This space of lack is that of faith and metaphysics, which the reason of the Dictionnaire both refrains from elucidating and cannot help, tirelessly, from traversing.

We'll focus here on just one of the characteristic phenomena of Voltairian poetics that we've just sketched in broad strokes it's the generalized practice of object absorption. Indeed, the dictionary article presupposes an object that the text sets out to circumscribe. But Voltaire doesn't circumscribe; he first deconstructs, then recomposes, shifting the ideological demarcation line. We'll analyze this process in the Idole article, where it's particularly visible. Then we'll show how, more generally, the fragmentation and demultiplication of the object accomplishes Voltaire's deconstructive aim. The theme of ingestion, a corollary of the theoretical mechanism of object absorption, places anthropophagy in the foreground as a form of Voltairean combat. Finally, digestion completes the phantasmatic motif, turning the deconstructive dialectic into a liberating parodic movement, opening up the possibility of ideological reconstruction.

.The deconstruction of the object in the Idol article

Voltaire's first work in the Dictionnaire philosophique is thus, contrary to what we expect of a dictionary, to deconstruct its object the object of the article is not defined we are shown that it doesn't exist, or more exactly that the phenomenon doesn't overlap with the agreed field of the word.

Thus, in the article Idol, idolater, idolatry, the seemingly classic and methodical recourse to etymology, far from constituting an object, defining a practice, posing an issue, demultiplies meanings to the point of absurdity and completely blurs the notion :

Idole comes from the Greek eidos, /// figure ; eidolon representation of a figure ; latreuein, to serve, revere, adore. This word adore is Latin, and has many different meanings : it means to bring the hand to the mouth when speaking reverently, to bow, to kneel, to salute and finally, commonly, to render supreme worship. (Pp. 236-2371.)

Voltaire parodies the genre of the Dictionnaire, furthermore practices it to the point of absurdity : giving the etymology of adorer indeed makes no sense, since adorer is already an equivalent of the etymology of latreuein. The result of this etymological overzealousness is not only a totally incongruous image (there's no connection between " to bring the hand to the mouth with respect " and idolatry), but a reversal of meaning, since " to worship supreme " is to worship God, or at least a god necessarily, geographically, transcendent, up it's the very opposite of idolatry, which identifies the god with the image that represents him.

The expected opposition between Christians, worshippers of the transcendent God, and the others, the pagans who worship " a piece of wood or marble " (p.238) is then denounced and, with supporting examples, destroyed : not all non-Christians are pagans and, besides the fact that the word pagan etymologically has not a religious but a geographical meaning, the Ancients were not so foolish as to take their statues for the gods themselves in any case, Catholics have theirs in the churches.

.The Greeks had the statue of Hercules, and we that of St. Christopher ; they had Aesculapius and his goat, and we St. Roch and his dog ; Jupiter armed with thunder, and we St. Anthony of Padua and St. James of Compostela. (P. 238.)

Telling off the Other as an idolater is a well-worn spring of Christian apologetics. Voltaire, having deconstructed idolatry as a consensually identifiable object of dominant ideological discourse, integrates the material into a single space : to pagan idols are opposed statues of saints, then to the very gods the very saints, in a homogeneous pantheon, but literally unqualifiable, since it is no longer either properly Christian or absolutely idolatrous. All difference falls away the real becomes desemiotized :

The difference between them and us is not that they had images and we have none : the difference is that their images figured fantastic beings in a false religion, and ours figure real beings in a true religion. (Ibid.)

Not only is the second difference posited by the statement annulled by the irony of the enunciation, for, being reduced to that of true and false, it appears purely arbitrary, but, by an added perversity, it takes exactly the form of the anti-discourse, the utopian one of the idolater : only the idolater can claim, Voltaire playing on the meaning of the verb, that other people's statues figure, i.e. represent imaginary gods, while his own figure, i.e. form, constitute real gods. The figure is according to whether this arranges symbolic form or real presence. In this discourse held from the outside, from an object that is deconstructed anyway, the identity of the verb completes the neutralization of difference.

The problematic node of Voltairean discourse, or in other words its object, is redrawn elsewhere and otherwise :

But you can draw from these bizarre ideas two great truths : one, that sensible images and hieroglyphics are of the highest antiquity ; the other, that all ancient philosophers recognized a first principle. (P. 244.)

How does the antiquity of images relate to the monotheism of all philosophers ? Both /// truths seem heterogeneous, and the object does not yet appear completely reconstructed. However, a chiasmatic structure is already emerging : the " ancient philosophers " of the second proposition belong to the " antiquity " of the first proposition, defining a common historical referent ; rational thought based on " a first principle " is opposed to analogical thought proceeding by " sensible images ", making the question of models, or logics of thought, the new terrain of ideological confrontation.

|

images (1) |

antiquity (2) |

|

ancient philosophers (2) |

first principle (1) |

(1) = model of thought ; (2) = historical referent

Beyond the disjointed discourse and deconstructed object, the device of the chiasmus reveals at the heart of the ancient opposition between the " images " of the idolaters and the " first principle " of the monotheists the new, properly Voltairian figure of the philosophers, included, hemmed in by the dilemma. From this inclusion, the new object can be born.

The new founding split only becomes systematized at the end of the article, at the moment when the real stakes of the article are revealed:

To console mankind for this horrible picture, for these pious sacrileges, it is important to know that, among almost all the nations named idolaters, there was sacred theology and popular error, secret worship and public ceremonies, the religion of the wise and that of the vulgar2. (P. 248.)

In place of the external, geographical and historical divide between Christians and idolaters, Voltaire substitutes an internal divide, isolating philosophers in the midst of the people, wisdom in the midst of superstition, the monotheism of the Mysteries in the midst of state polytheism. The new opposition is an inclusion. Once established, it lays the foundations for Voltaire's theistic creed, recycling quotations from Orpheus, Maximus of Madaura, Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius : the reconstruction is complete.

.This course of a complete article, seemingly very diffuse, highlights in Voltaire a skilfully concerted textual strategy : in the first instance, the aim is to deconstruct the object provided by the discourse of the old Christian apologetic symbolic system, proceeding by demultiplication (etymology plays this role), amalgamation (it's the parallel of gods and saints) and neutralization of founding differences (here, through the ironic pastiche of a Christian discourse to which Voltaire gives a tendentiously idolatrous content). In a second stage, the material of the former discourse is recycled in a chiasmatic movement positing the founding cleavage no longer between an ideology and its opposite (Christianity versus idolatry), but between an ideology and its hidden interiority (the theism secretly professed by the sages at the heart of the polytheism of ancient peoples), an interiority superior but surrounded, ruling but threatened.

.Fragmentation and demultiplication

More diffusely, the same processes can be found throughout the Dictionnaire : fragmentation and demultiplication are the key instruments of the first deconstructive work. For example, the article Soul, to prove that the notion does not exist in Jewish tradition, juxtaposes a long list of quotations from Deuteronomy alternating purely temporal threats of divine punishment (" you will be exterminated ", " you will be destroyed ", " you will experience famine, poverty ; you will die of misery, cold, poverty, fever you will have the rash, scabies, fistula...you will have ulcers in your knees and in your fat... /// legs "), with promises of rewards that could not be more immediate and concrete (" You will have enough to eat ", " so that you may eat and be drunk ", " so that your days may be multiplied ", " the fruits of your belly, of your land, of your cattle, will be blessed "), not to mention incitements to murder (" kill him at once, and let all the people strike after you ", " slaughter all without sparing a single man, and have no pity on anyone ")3. Such an anthology deconstructs the symbolic order that Deuteronomy is supposed to convey by isolating punishments and rewards from their context and justification. Voltaire can then conclude :

It is obvious that in all these promises and in all these threats there is nothing but temporal, and that not a word is to be found about the immortality of the soul and the future life. (P. 12.)

Deprived of any spiritual dimension, the lacunar text presents a de-emiotized and blurred object. The inflation of references paradoxically creates a void, a kind of floating discourse. It's no longer a discourse, but a jumble of " all these promises " and " all these threats ". The symbolic foundation of Christianity is deconstructed into picturesque barbarism, an Oriental bric-a-brac of materialistic horrors.

.More fleetingly, the tip that closes the article Divinity of Jesus plays on the same deconstructive power of demultiplication :

It was above all Fauste Socin who spread the seeds of this doctrine in Europe ; and on the end of the sixteenth century it was not long before he established a new species of Christianity : there had already been more than three hundred species. (P. 172.)

The Socinian doctrine that Voltaire seemed to be defending against the Catholic dogma of Jesus' divinity is ultimately integrated into the anonymous and ridiculous multitude of three hundred sects. Socin has no more grace here in Voltaire's eyes than the others : the point is to deconstruct the object Christianity, not to substitute it.

The aim is identical in this passage from the article Tolérance :

Contemplative Gnostics, Dositheans, Cerinthians existed before Jesus' followers took the name Christian. There were soon thirty Gospels, each of which belonged to a different society ; and by the end of the first century we can count thirty sects of Christians in Asia Minor, in Syria, in Alexandria, and even in Rome. (P. 404.)

Whether we're talking about thirty or three hundred sects, the dizzying effect is the same : the symbolic unity of early Christianity is fragmented, deconstructed. We also find in the accumulation of names, as we found in the article Soul in the promises and threats of Deuteronomy, or in the article Grace in the jargonous enumeration borrowed from Jesuit casuistry (p. 226), the exoticism of a verbal display whose shimmer accelerates de-emiotization.

The picturesqueness of this deconstructive demultiplication should not, however, obscure the sordid horror and cruelty that almost always underlies it, according to that dialectic of the object and the abject that J. Kristeva analyzes in Powers of the horror. The demultiplied sects that occupy the place of the deconstructed object crawl, swarm and tear each other apart in the underground of an ignoble clandestinity. Beneath the façade or veneer of apologetic discourse, the text exhumes the pestilence, fermentation and contagion of pre-object horror. Voltaire reduces symbolic structure to a shimmer that fascinates and ensnares us in its lure, only to deliver us brutally to the instinctive repulsion of the abject.

Even more terrifying than the evocation of the internecine quarrels of early Christianity, the list of /// crimes of the papacy in the article Pierre slides from distant irony to horrified indignation, ending with the evocation of an " Alexander VI, whose name is pronounced only with the same horror as those of the Nerons and Caligulas " (p. 351). If the ideological object is deconstructed by the discursive fragmentation engendered by the list's anaphoric structure (" quand on fait réflexion : Que... Que... Que... Qu'enfin... "), this deconstruction is accomplished in a double movement of horror, hence rejection, and inclusion, or more precisely here of integration of Christian history with the history of Rome that it continues. The crimes of the Borgias are worth those of Nero or Caligula, they suspend discourse in the horror of what they evoke : integration and abjection are accomplished here in horrified silence, the final degree of the neutralization and de-emiotization of discourse.

It's impossible to cite every example of integrative demultiplication. Let's mention the article Resurrection, which dissolves the founding Christic episode in the evocation of all the similar miracles of antiquity : " Athalide, daughter of Mercury, could die and rise again at will ; Aesculapius restored life to Hippolytus, Hercules to Alcestis Pelops, having been chopped to pieces by his father, was resurrected by the gods. Plato relates that Heres was resurrected for fifteen days only. " (P. 371.)4. But it's in everything to do with Jewish history that the examples are most abundant : the article Abraham compares the patriarch to Thaut, Zoroaster, Hercules, Orpheus and Odin (p. 2) the article Adam identifies Adam and Eve with Adamo and Procriti, protagonists of the Indian Veidam (p. 6, repeated p. 218 and p. 294) ; the Genesis article integrates the biblical serpent with Chaldean, Bachic, Egyptian, Arabic, Indian and Chinese myths (p. 219) ; the article Joseph states about the episode at Putiphar's that " it's the story of Hippolytus and Phaedra, of Bellerophon and Stenoboea, of Hebrus and Damasippe, of Tanis and Periboea, of Myrtile and Hippodamia, of Peleus and Demenette " (p. 261).

More clearly than the former, all these examples are based on a disproportion between the initial object and the multiple comparants to which it is integrated : integration is assimilation, dissolution, ingestion. It's no coincidence, then, that the motifs of cooking, eating, and especially devouring and anthropophagy are so recurrent in the Dictionary. To the textual strategy of deconstruction corresponds the development of an imaginary of ingestion and digestion.

Ingestions

The fantastical work is evident as early as the article Ame, when Voltaire focuses on the absurdities and contradictions of all philosophical systems that assume an immortal soul, wondering

[...] how the me, the identity of the same person will subsist ; [...] by what trick of skill a soul whose leg will have been cut off in Europe, and who will have lost an arm in America, will recover this leg and this arm, which, having been transformed into vegetables, will have passed into the blood of some other animal (p. 11).

Beyond the ironic confusion between the spiritual substance of the soul and the material vicissitudes of the body, there's a burlesque telescoping of the symbolic object and the violence of reality. This soul-body is the psychoanalytic moi that populates our fantasies. The haunting of membra disjecta, characteristic both of this mirror stage where the moi is constituted and of its flip side, the anxiety of subjective deconstruction, appears here with the severed leg and the lost arm. But Voltaire's originality lies in articulating this fantasy with the theme, then fashionable in scientific circles, of latus and assimilation5 : the me is not confined to fragmentation and injury ; it recomposes itself elsewhere, recycles, vegetalizes, to be eaten, i.e. absorbed into another living being, another me6.

The idea is expressed even more clearly in the article on Papism, in the form of the accusations that the Unitarians level at English Catholics according to one of them :

You know that these monsters no more believe in the resurrection of bodies than the Sadducees ; they say that we are all anthropophagous, that the particles which composed your grandfather and your great-grandfather, having been necessarily dispersed in the atmosphere, have become carrots and asparagus, and that it is impossible that you should not have eaten some small pieces of your ancestors. (P. 334.)

Anthropophagy is not repelled as an unnatural horror (we know Voltaire's leniency towards Indian cannibals, in the article Anthropophages) ; it is natural law7. The resurrection of the dead is impossible because we have recycled them in ourselves, because their matter and ours are common. The textual strategy of deconstructing and recovering the old symbolic object in a new discourse thus corresponds to an equivalent phantasmatic device, at the end of which the anguish of symbolic castration and the dereliction of the me is turned around and positive in a dynamic of absorption, ingestion and recycling. Anthropophagy bears the new values : here, in an ironic, distanced form that preserves its author, the substitution of anthropophagy for resurrection violently lays the foundations of a materialism.

We obviously find a similar text to the Resurrection article, in the second section :

The body of a man reduced to dust, scattered in the air and falling back on the surface of the earth, becomes vegetable or wheat. So Cain ate part of Adam ; Enoch fed on Cain ; Irad, on Enoch Maviael on Irad Methuselah, on Maviael and it so happens that there is not one of us who has not swallowed a small portion of our first father. That's why it's been said that we're all anthropophagous. Nothing is more sensitive after a battle not only do we kill our brothers, but after two or three years, we've eaten them all when we've harvested on the battlefield we'll be eaten too without difficulty in our turn. But when we have to rise again, how can we give back to each one the body that belonged to him without losing any of our own ? (Pp. 373-374.)

Without insisting on the delusional character of a theory that can only be explained by the underlying workings of fantasy, we note that anthropophagy is identified by Voltaire sometimes with the ingestion of the father, sometimes with that of the brothers, which clearly marks the equivalence of the Father and the Other in the figuration of the alienating instance of the symbolic : the external conflict with the law is resolved by the incorporation of the one who represents it. Symbolic mediation, the latus of which " vegetable ", " wheat " and " harvest " play the role, is absorbed, precipitating the telescoping of souls. To eat is to do away with mediation, to eat the Other.

As we might have suspected, anthropophagy has something to do with the symbolic. Yet curiously, in the Dictionnaire philosophique, it both manifests the violent irruption of natural law into theological babble, or in other words identifies with the principle of reality, and, quite the opposite, represents this babble, through the intermediary of transubstantiation. We see this in the Third Question of the article Religion, where Voltaire defines the Eucharist as " la manducation supérieure, l'âme nourrie ainsi /// than the body of the members and blood of the Man-God adored and eaten in the form of bread, present to the eyes, sensitive to the taste, and yet annihilated " (p. 364). The scandal of the Eucharist is matched by the ridicule of the dietary prohibitions of the Mosaic law8, with which the apostles dithered so much9, but also that of the Christian distinction, deemed absurd, of fat and lean10. In the article Pierre, Voltaire recalls the allegorical dream from the Acts by which the apostle is ordered to eat the forbidden foods :

[...] the voice of an angel had cried out : " Kill and eat. " This is apparently the same voice that cried out to so many pontiffs : " Kill all, and eat the substance of the people ", says Wollaston (p. 349).

Always ingestion degenerates. The abolition of the old law translates into an injunction to anthropophagy, since God asks the pope to feed on the substance of the people : anthropophagy no longer expresses the natural law but its opposite, the delirious inflation of the disease of fanaticism.

The article Lettres, gens de lettres ou lettrés proposes another type of reversal, against oneself. After denouncing the persecution suffered by the philosopher who publicly seeks and speaks the truth, Voltaire resorts to a series of images :

The man of letters [...] resembles flying fish : if he rises a little, the birds devour him if he dives, the fish eat him.

Any public man pays tribute to malignity ; but he is paid in denarii and honors. The man of letters pays the same tribute without conceiving ; he has descended for his pleasure into the arena, he has condemned himself to the beasts. (Pp. 273-274.)

Caught between " the contempt of the world's powerful ", and the misfortune " of being judged by fools ", the intellectual risks devouring himself both when he places himself under the protection of a high figure and when he appeals to public opinion. Above him, the tyranny of "Kill all, and eat the substance of the people", and below him, the harsh natural law of mutual devouring, are part of the same cannibalistic overflow. Object absorption degenerates into universal absorption, the very subject is threatened.

But, and this is the most astonishing thing, the intellectual of the Voltairian imaginary takes pleasure in his torment. This masochistic anthropophagy is part of the absorption and recycling movement that characterizes the textual strategy of the Dictionnaire philosophique. In the phantasmatic universe that underpins this strategy, absorbing the world or being absorbed by it is all one : pre-object orality is reversible. The Voltairean struggle is a cannibalistic one, in which the victor is both the eater and the eaten. Outside and inside are confused what matters is the movement of inclusion that results from this horrible and delicious ingestion, whether my father is in my belly (Resurrection article), or my belly is in the arena (Letters article).

Feces

Ingesting has no limits. It is both pure power and pure excess, dynamic and overflowing. So it's only natural that it should be associated with the symmetrical motif of dejection11. The article Transubstantiation, for example, describes the scandal of the Eucharist for Protestants :

Their horror increases, when they are told that one sees every day, in Catholic countries, priests, monks who, coming out of an incestuous bed, and not having yet washed their hands stained with impurities, go and make gods by the hundreds, eat and drink their god, shit and piss their god. (P. 411.)

The outrageous reference to incest, as well as the detail of soiled hands, demonstrate the transgressive nature of consumption that is indiscriminately sexual, dietary and spiritual, whose implicit anti-model is paradoxically the Jewish religion, founded on the prohibition12, separation and the dread of defilement. The symbolic object Voltaire deconstructs is not only an object of consumption, but also of dejection, the host representing this brutal telescoping of the highest symbolic and the lowest corporeal. In the first section of the Vertu article in Questions sur l'Encyclopédie, Voltaire is even sharper, going so far as to imagine a dialogue of the honest man and " cet excrément de théologie " soon to be called, more lapidarily, the excrement (pp. 627-628).

However, nothing is lost in the ideological reconstruction machine launched by Voltaire. Even dejection is recuperated and recycled, thanks to the motif of coprophagy, as can be seen, for example, in Ezéchiel :

[...] several critics revolted against the command the Lord gave him to eat, for three hundred and ninety days, bread of barley, wheat and millet, covered with shit.

The prophet cried out " Pouah ! pouah ! pouah ! my soul has not hitherto been polluted " and the Lord replied " Well ! I give you ox dung instead of man's excrement, and you shall knead your bread with this dung. " (P. 191.)

Playing on the ambiguity of the Latin translation13, Voltaire hijacks the injunction of Iahweh, in Ezekiel chapter IV, verses 12 to 15, which instructed the prophet to bake his galette on heaps of human excrement, then on cattle dung, as a fuel, not an ingredient. Parodic excess and deliberate bad faith certainly explain this hijacking of the biblical text ; but, set against the previously cited passages, this passage delivers a deeper meaning. Scatological abjection, identified with the divine command, articulates the symbolic principle (" the command that the Lord gave him ") with the movement of abjection (" Pouah ! pouah ! pouah ! "). At first, of course, the aim is to reduce the old symbolic system, to make it regress into an imaginary of abject orality. But - and this is a fundamental characteristic of phantasmatic work - this reduction, this regression, is reversible at a second level, the text demonstrates that with excrement, by ingesting digestion, we can manufacture the symbolic.

.Voltaire's hesitation at the end of the article tends to confirm the reversible meaning of this parody. In the first version, Voltaire concluded by preaching tolerance :

Let us defy all our prejudices when we read ancient authors, or travel to distant nations. Nature is the same everywhere, and customs everywhere different. (P. 194.)

The biblical text was thus justified after having been parodied, and the primacy of nature over usage referred directly to ingestion as a principle of reality, as a violent but salvific irruption of reality into the literal ridiculousness of the law. In a way, this conclusion legitimized Ezekiel's parable.

However, the addition published in 1765 in the Varberg edition clearly disassociates itself from the rabbi who came to congratulate Voltaire in Amsterdam for having " made known all the sublimity of the Mosaic law ". Indeed, there is a long way to go between the apology of Judaism and Voltaire's recuperation of its symbolic power at the end of a work of negativity that parodied it as a duty of coprophagy. Symbolic recovery /// builds another object, even if the ancient law plays an essential role as material. The penances inflicted on Ezekiel form the basis of the injunction of tolerance and the principle of a transcultural humanism that recognizes the same nature behind " uses everywhere different ". The Mosaic Law was the material of Voltaire's discourse, not its aim. So Voltaire, reporting the words of " a highly educated young man ", concludes :

Whoever loves Ezekiel's prophecies deserves to have lunch with him. (P. 19414.)

However, this quip ridiculing the Amsterdam rabbi's proselytizing enthusiasm is ambiguous : Why doesn't Voltaire speak directly, but through a young man who isn't him ? Doesn't this mean that, through his article, he has just had lunch with Ezekiel? More generally, doesn't this fascinating and ignoble lunch designate the Dictionary itself ? Indeed, symbolic elaboration presupposes the neighborhood of the abject, as ironically marked by the article Gloire, conceived as a harangue by Ben-al-Bétif, leader of the dervishes :

What would you say of a little chiaoux who, while emptying the pierced chair of our sultan, would exclaim : " To the greater glory of our invincible monarch ? " (P. 225.)

The double gesture of evacuating excrement and singing the monarch's glory once again signifies, in parodic mode, the articulation between dejection and symbolic elaboration. The verbal play that associates the name chiaoux with the contents of the pierced chair reinforces the pre-object indifferentiation between the servant performing the ritual - in other words, the symbolic representative - and the ritual's abject object, the royal excrement. But here again, what's ambiguous is that the dejection manifests itself both as a subversion of the symbolic and as a manifestation of power15 : not only does Ben-al-Bétif's question ridicule the shiaoux, not the " invincible monarch ", but it prepares the reversal of the article.

In the first paragraph, in fact, Voltaire deconstructed the glory of God, which serves as a pretext for the actions of fanaticism, by reducing the object of theological discourse to an empty formula in the language of the devout. After the scatological reference, the second paragraph contrasts the inaccessible " glory of the infinite Being ", with the pettiness of men : glory can never mediate between men and God on the contrary, it is the symptom of his inaccessibility through language, God's ineffable, unspeakable glory constituting a real hole, a foundational lack on which Voltaire's article is built : " But you, poor people, what glory can you give to God ? Ce cesser de profaner son nom sacré. " (P. 226.) The dejection thus articulates the old mediatorial conception of glory, in the first paragraph, to the new transcendent conception in the second. It marks the end of the deconstructive work and prepares, in parody and abjection, the new symbolic order, recognizable by the founding failure of its object.

The problem of symbolic mediation is posed in a more complex way in the apologue found in the eighth question of the Religion article, and pits the supporters of the god Fo against those of Sammonocodom. They choose to refer to the Dalai Lama to decide which of the two is the true god:

.The Dalai Lama begins, according to his divine custom, by distributing his pierced chair to them.

The two rival sects first receive it with equal respect, dry it in the sun, and enshrine it in small rosaries which they kiss devoutly ; but as soon as the Dalai Lama and his council have pronounced in Fo's name, here comes the condemned party throwing the rosaries at the vice-god's nose, and wanting to give him /// a hundred blows with stirrup leathers. The other party defends his lama, from whom he has received good lands both fight for a long time ; and when they are tired of exterminating, murdering and poisoning each other, they still say big insults ; and the Dalai Lama laughs ; and he still distributes his pierced chair to whoever is willing to receive the good father lama's excrement. (Pp. 369-370.)

The first deputation of the two rival factions to the Dalai Lama constitutes the latter as the mediating instance of symbolic space. The distribution of excrement materializes this mediation in what tends to constitute a transitional object, i.e. something intermediate between the abject and the object. The little rosaries are devoutly kissed in an ambivalent gesture of the incorporating and recipient mouth16, which integrates power or addresses it, depending on whether the kiss is taken as ignominious reality (kissing shit) or parody of symbolic ritual (praying while shelling out one's rosary). As soon as the symbolic mediation shifts from the Dalai Lama in person to the excremental rosary, the object targeted by the tale tends to deconstruct itself as a petit a object, causing the symbolic frame to regress into the imaginary. The metonymic designation of excrement by the pierced chair, the container for the content, is characteristic of this regression.

The second phase of the story opens after the Dalai Lama has sided with Fo against Sammonocodom : through the choice of " nom de Fo " the symbolic is no longer associated with the excremental and is identified with linguistic proferation it leaves anal ambivalence and metaphoricity for scission and selection. Paradoxically, Voltaire's identification of the symbolic with language is devastating: from controversy, it degenerates into civil war and spreads horror. The shift from a theme of mediation to an escalation in scissionist violence introduces a new textual dynamic based on outburst and overflow. To the excess of violence (" when they are tired of exterminating, murdering, poisoning each other ") corresponds the excess of goods (some have " received good land " ; all can " receive the dejections of the good father lama ") and the plethoric effect of syntax (" they say again big insults ; and the Dalai Lama laughs ; and he distributes again his pierced chair "). The disappearance of the initial object (symbolic mediation) is replaced by a triple dynamic of excess: thematic, referential and textual. From dejection as mediation, we've moved on to dejection as supplement. The apologue ends, then, only in appearance, with a recommencement. The first distribution of the divine pierced chair was a ritual whose ridicule was external: only the reader laughed at a ceremony that the protagonists took seriously. The last distribution is no longer ritualistic, but superfluous: busy with their civil and verbal war, the enemy factions no longer pay attention to it. Criticism is internalized; the symbolic object collapses. Laughter becomes part of the ritual. It's the Dalai Lama, not the reader alone, who laughs17.

The theme of dejection as excess, parodic overabundance and contagious violence, reveals itself to be inseparable from a movement of internalization of critique, introversion of ideological cleavage and confrontation.

The reversal of the Glory article, like the passage from the first to the second phase of the Dalai Lama's apologue in the Religion article, thus manifests an identical textual strategy of decomposition and recomposition based on the ambivalence of the excremental motif, at once a support for the work of the /// negativity through parody and abject disintegration, and a dynamic figure of symbolic energy and power. But the kinship between the two texts is also apparent at another level: the ideological space of reference shifts from a system of mediations (the human celebration of divine glory, like the father figure of the Dalai Lama, is a mediating instance between man and God) to a system of disproportions and excesses: in the serious mode, divine glory becomes incommensurable with man's smallness in Ben-al-Bétif's harangue ; in the parodic mode, the Dalai Lama's largesse, slipping outside the symbolic game, unleashes a violence without recourse or regulation.

Through this cannibalistic violence, at once horrific and liberating, Voltaire represents, from within the old world that his writing shatters and his imagination recomposes, the saving hydra of modernity.

Communication delivered at the international congress Voltaire et ses combats, Oxford and Paris, September 1994

Notes

///All references are given in Raymond Naves' edition, Garnier, 1967. Other games with a similar deconstructive aim can be found, a game of scission in the article Abbé, which pretends to take the etymological meaning of père literally (p. 1), or a game of dissemination in the article Pierre, which multiplies the translations of the name, marginalizing the originally Hebrew pun of Christ on Cepha (p. 347).

The same idea can be found in the article Religion : " All these Babylonian, Persian, Egyptian, Scythian, Greek and Roman philosophers admit a supreme, rewarding and avenging God. They do not tell this to the people first ; for anyone who would have spoken badly;about onions and cats in front of old women and priests would have been stoned. " (P. 363.)

See pp. 11-12.

The same examples appear in the article Miracles, p. 316.

See, for example, the beginning of Rêve de D'Alembert, admittedly of later writing (1769).

The term animal here has the generic Latin meaning of living being. The animal, in the classical language, is not the beast that is contrasted with man.

The idea also appears in the article Destiny, in the apologue of the owl and the nightingale : " Stop singing under your beautiful shades, come into my hole, so that I may devour you there. " (P. 167.) Finally, we find it again in the article Genesis, where Voltaire opposes the harsh law of nature to God's alleged alliance with the beasts, ridiculed with the mawkishness of Francis of Assisi : " That all animals would devour each other ; that they would feed on our blood and we on theirs that after eating them, we would exterminate each other with rage, and that all we would lack would be to eat our fellow creatures slaughtered by our hands. " (P. 223.)

Cf. des Lois, p. 288 ; Tolérance, II, p. 406.

Cf. Christianisme, pp. 116-117.

Cf. Lent, p. 63 ; Japanese Catechism, p. 92 ; War, p. 231.

There's an article Dejection in the Questions on the Encyclopedia. /// (Information given by A. Magnan.)

One thinks here of the horror felt by the Essene for the incest of his rogue compatriot, in the article of the Laws, pp. 282-283.

Clarification given by Roland Mortier.

We find, in another register, the same movement of parodic and masochistic inclusion at the end of the article Liberté de penser, which consists in the dialogue of a liberal English milord and a Spanish count, hired by opportunism in the service of the Inquisition : " Médroso. - You think my soul belongs in the galleys ? Boldmind. - Yes and I'd like to free it. Médroso. -But what if I am in the galleys? Boldmind. - In that case you deserve to be there. " (P. 281.)

Voltaire may have drawn inspiration for his joke from the account of the Persian ambassadors at the beginning of Aristophanes' Acharnians (vv. 80-82).

It's the same gesture of " bringing the hand to the mouth while speaking with respect " that Voltaire featured at the head of the Idol article. The incongruity, the incoherence of the speech in the obtuse register can be explained by the phantasmatic obsession, always the same from Idole to Religion, which governs the text's obtuse register.

We should compare this apologue with that of the pikes of the good King Daon, in the Chinese Catechism, pp. 77-78. The mediating object, the Oannes pike, is destroyed by the ingestion of the male pike, then the female. But this destruction is made up for by a general banquet, where guests from both factions "greedily ate [pikes], either œuvés or laités " (p. 78). The abject object, the fish, produces scission, then overflow and indistinction in ingestion.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Le cannibalisme idéologique de Voltaire dans le Dictionnaire philosophique », in Voltaire et ses combats, dir. U. Kölving et Ch. Mervaud, Voltaire foundation, Oxford, 1997, t. 1, p. 415-428.

Voltaire

Archive mise à jour depuis 2008

Voltaire

L'esprit des contes

Voltaire, l'esprit des contes

Le conte et le roman

L'héroïsme de l'esprit

Le mot et l'événement

Différence et globalisation

Le Dictionnaire philosophique

Introduction au Dictionnaire philosophique

Voltaire et les Juifs

L'anecdote voltairienne

L'ironie voltairienne

Dialogue et dialogisme dans le Dictionnaire philosophique

Les choses contre les mots

Le cannibalisme idéologique de Voltaire dans le Dictionnaire philosophique

La violence et la loi