Joel Coen’s American cinematic adaptation The Tragedy of Macbeth, released in the autumn of 2021, belongs to those films that are almost entirely constructed with direct and semi-direct references to fine art. The film, that assembled a stellar cast with Denzel Washington as an aged warhorse Macbeth, Frances McDormand as a determined, mature Lady Macbeth, and the exquisite and versatile Kathryn Hunter as a Weird Sister, becomes an art gallery where cinematic frames are replaced by artworks infused with meanings, histories, references, visions, messages, and circumstances of their creation. The paintings, which Coen directly refers to in his Macbeth, provide interpretative material to construct enhancing characterisations of dramatic figures, to understand and justify characters’ decisions and actions, and to recognise archetypes that govern Shakespeare’s and Coen’s fictional worlds.

Paintings are artificial compositions of signs which are recognised as vehicles of meanings. The interpretative compatibility of signs and meanings is regulated by codes: ‘Since the (intended) meaning of a sign depends on the code within which it is situated, codes provide a framework within which signs make sense. [Codes] embody rules or conventions of interpretation which systematically regulate the ways in which meanings are produced’. (Chandler, 2017, p. 178). In a broader sense, the rules – in this case the laws of perception – are constructed within a sociocultural context shared by producers and recipients of meanings alike: these ‘are reflections of cultural patterns, or […] they are acquired forms, a system of preferences and habits, conventions, and emotions, fostered in us by the natural, social, and historical context we inhabit’ (Eco, 1989, p. 76). In the instance of Coen’s Macbeth, this article claims, Western and Central European and American cultural traditions determine the codes necessary to identify and read signs, e. g. archetypes, symbols, motifs, and metaphors embedded in paintings (Panofsky, 1955, pp. 28-42) and referred to in films.

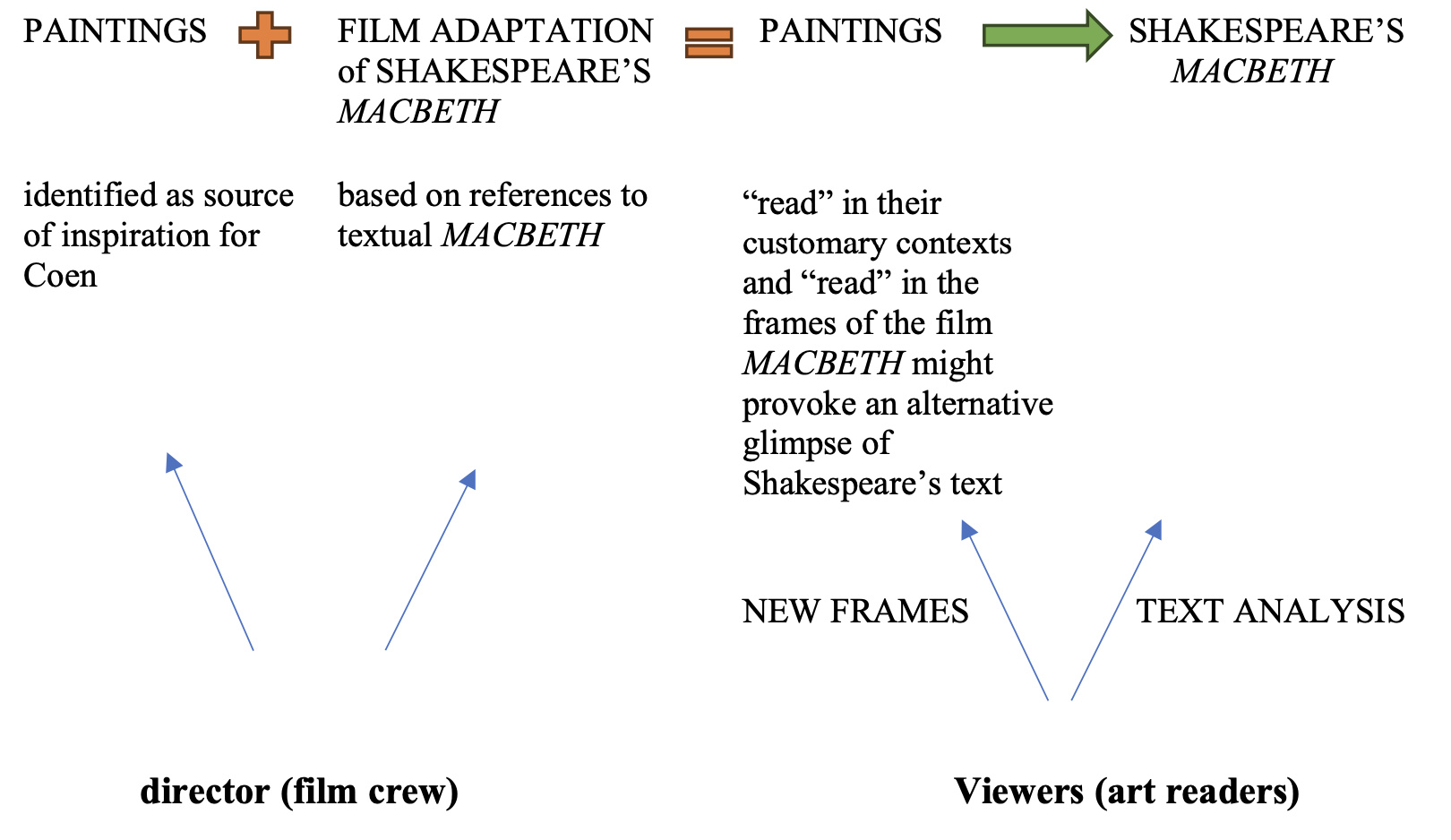

This article follows Mieke Bal who, in A Mieke Bal Reader (2006), introduces a technique, or methodology based on ‘reading images’ (2006, p. 290). She claims that each interpretation, i. e. each reading of signs happens in specific circumstances, called ‘frames.’ Frames, ‘a sociohistorical context or framework’ (Bal, 2006, p. 290), usually of a subjective nature, allow reading signs in a unique manner. The initial frames – pre-determined by an artist – ensure an image analysis compatible with the painter’s intentions. However, once initiated in new momentary circumstances, personal experience, or external interpretation, frames might alter the general messages embedded in an art piece. Gillian Rose confirms this when she claims that ‘an image may have its own visual effects’ (Rose, 2016, p. 22). In the case of The Tragedy of Macbeth, Joel Coen’s cinematic adaptation designates interpretative limits or original frames for reading not only Shakespeare’s text but also those paintings referred to in the movie. The frames’ interpretative ‘outcome is meaning’ (Bal, 2006, p. 290) attributed by the ‘viewer [who] is a decisive element in the process’ (Bal, 2006, p. 290).1 Consequently, this article examines a selection of paintings as first indicated in the Macbeth adaptation and then approached by viewers within the frames of Coen’s Shakespeare production. Together, Coen’s film and the recognition of these paintings – their customary and reframed meanings – bring to the surface a wider, or alternative, interdisciplinary understanding of Macbeth. A viewer would never make these connections without the film. As such, the paintings provide another angle that serves as an additional interpretative tool to appreciate Shakespeare, as the following chart depicts:

Approached within the frames of Coen’s adaptation, the paintings offer auxiliary connotations and become supplementary interpretative frames for Shakespeare’s dramatic text. Incidentally, they develop into visual messages independent from their respective painters’ intentions (cf. Bal, 2006, p. 305). Thus, the images demand (de)construction but allow new meaning, as Kenneth Rothwell confirms when he states that ‘[s]ometimes a film adaptation of a Shakespearean play in visualizing the verbal, […] in making a ‘picturization’, will interpret or expand on the text, or explore a subtext, more intricately than is possible onstage’ (Rothwell, 1983, p. 50). He labels the camera ‘as partner in the de-creation and re-creation of a drama’ (Rothwell, 1983, p. 50) which in turn evokes original interpretations of the newly created film narrative. Coen’s adaptation, created according to established interpretative codes of art, becomes an artistic rendering of the textual source and simultaneously a meaningful intermediary between the evoked paintings and the original Macbeth. As a result, the images – employed intentionally by the director and appropriate crew members and transmitted to viewers and readers – are also adapted as references for Macbeth’s interpretation. Studying these ‘can shed a new light on the material and the dynamics studied in convergence’ (Fehrle, 2019, p. 9). Mieke Bal underlines that semiotics has developed tools ‘to examine how the idea of reading helps address questions of meaning and the power over meanings, without reducing the image’ (Bal, 2006, p. 299). She conscientiously draws on the methods of frames: the reading of these encourages the competent viewer to reframe, reread, and find further references: ‘Refusing that [initially intended] framing forces the viewer to revert to the image and look again’ (Bal, 2006, p. 299).

Coen employs a specific iconographically connotated genre that deals with the depiction of nature in paintings – landscapes –, to transmit his cinematic idea of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Landscapes indeed constitute the overarching atmosphere in Coen’s film version by mirroring a mood of oppression, fear, and uncontrollable forces. The present article relates to a few examples of the genre: The Abbey in the Oakwood (1809-1810) by Caspar David Friedrich (a moodscape/ veduta ideata), The Cliff at Étretat (1869) by Gustave Courbet (a marine), Rough Sea (1883) by Claude Monet (a seascape), Wheatfield with Crows (1890) by Vincent van Gogh (a landscape with staffage) and Three Women on the Road (c. 1930) by Kazimir Malevich (a landscape as a background for human figures). For this article, other paintings could have been chosen to elucidate on the film; however, our present choices undoubtedly reflect recognizable references that should appear detectable. Initially, compositions of landscapes are utilized as a background for figurative scenes. Since the 17th century, they have been acknowledged with complete independence and constitute a separate genre represented by ‘a painting, drawing, or other depiction of natural scenery. Although figures and man-made objects may be included in a landscape, they are of secondary importance to the composition and incidental to the content’ (Mayer, 1992, pp. 219-20).2 Except for landscapes with staffage – relatively small human beings or animals introduced to enliven a landscape (Mayer, 1992, p. 397) –, there are also seascapes where the sea becomes the central motif of a painting. If the image includes vessels or any other maritime objects, such a landscape is recognised as a marine (Mayer, 1992, p. 373). Finally, a different kind of landscape mentioned here is veduta ideata: ‘it is a scene [with architectural sections] that is realistically conceived but whose elements are completely imaginary’ (Mayer, 1992, p. 444). In the case of Caspar David Friedrich, these images would be called moodscapes – because they are saturated with symbols, mystery, spirituality, dream visions, or prophecies.3 Engaging Mieke Bal’s act of reading allows the interpretation of each ‘painting as a proposition, [the analysis of] a visual work that has something to say’ (Bal, 2006, p. 296) as a response to a social discourse. This article aims to discursively treat the chosen paintings as interventions (cf. Bal, 2006, p. 298) in Coen’s Macbeth.

In his landscapes, Caspar David Friedrich shows how to experience nature from a Romantic perspective. e.g. that of Novalis. In 1798, German writer and philosopher of early Romanticism, Novalis (Friedrich von Hardenberg), publishes his The Disciples at Saïs and redefines the idea of Nature. The author convinces readers that Nature should be seen as an independent being. ‘She’ is categorised as mysterious, possibly destructive, and serves as a spiritual entity. She invites appreciation as a peculiar, fascinating partner who causes fear and simultaneously awakens hope and intimacy. Novalis comprehends Nature as a being endowed with a soul, an opponent of God, an embodiment of death, a destroyer, and a mirror of human inner life. At the same time, ‘[l]andscape for him, as for every true Romantic, [is] but a state of the soul, Nature but the accompaniment to the motif of man’s mood’ (Birch, 1903, p. 48). As such, landscapes represent emotions, among them struggles, fears, ambitions, and dream visions of the painters and viewers. Nature, on the other hand, provides tools to experience and understand the mentioned feelings: the Romantic movement recognises ‘[N]ature’s sublime power and wonder’ (Langdon, 2001, p. 405). Landscape painting is, ‘like poetry, the means of exploring the spiritual depths of man’s response to nature. It [is] on the one hand fantastic and on the other hand exploratory’ (Vaughan, 2001, p. 654). The profound, sometimes even obsessive focus on Nature, her fleetingness and elusive atmosphere, establishes the foundations of Impressionist art, too. Impressionists manage to capture Nature’s ephemerality, sensuality, and complexity. The arrangements and elements of landscape compositions, the colours and techniques used, are intended to convey not only an infinite variability of nature but also in-depth psychological aspects. On the one hand, Claude Monet’s seascapes represent his constant efforts to capture the movement of waves and clouds. He achieves this by applying distinct brushstrokes to the canvas and producing unique wet colour effects. On the other hand, the post-Impressionist ‘van Gogh expressed psychological turmoil through expressionist contrasts of violent colour’ (Langdon, 2001, p. 405) in landscape paintings.

Despite being neither a Romantic artist nor an Impressionist, Gustave Courbet remains in an intimate relationship with nature. The artist’s connection with landscape seems to be a physical and sensual bond (De Font-Reaulx, 2021, p. 27). For Courbet, nature becomes a synonym of the return to an unspoilt life, purity of soul, inner harmony, and freedom as implied by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (cf. Rubin, 2013, p. 229). Consequently, landscapes not only provide the painter with a shelter from civilisation, but they also allow him to ‘reveal his inner self, barely dissimulated by the reproduction of nature’ (De Font-Reaulx, 2021, p. 29). The Realist Courbet, like many other artists of the 19th century, finds in landscape painting the source of his moral and physical recovery, as well as the sense of completeness and liberty (cf. Rubin, 2013, pp. 220 and 257). Similarly, the sensitivity to nature presented by Kazimir Malevich is closely related to his background of growing up in a rural environment. Consequently, his artistic output ‘represents an appreciation of the land in an ideal state’ (Crone and Moos, 2014, p. 78). His early works are inspired by Monet, Pissarro, Sisley, Cézanne, and the post-Impressionist visions of van Gogh. The tradition of the Impressionist depiction of nature, though already transformed and adjusted to artists’ taste, is still visible in Kazimir Malevich’s early paintings. All mentioned artists reveal intimate relations to nature exposed in their landscapes. Their works are emotionally and symbolically charged.

A similar approach to a symbolic, emotional, and dramatical potential of nature is presented in the works of William Shakespeare. In The Tragedy of Macbeth, the playwright uses verbal images – metaphors, similes, and other rhetorical figures – to build an atmosphere of ambiguity, mystery, and uneasiness, also represented in the macrocosm of the dramatic work. This is apparent from the beginning of the play when, for instance, Macbeth and Banquo encounter the Weird Sisters in a foggy heath landscape on a ‘foul and fair day’ (1.3.38) during stormy weather which reflects the political upheaval in the country. Shakespeare relies on the description of weather conditions and their symbolism when creating a hypotyposis of Duncan’s path to Macbeth’s castle (1.6.1-9). The lines also disclose a nocturnal landscape at the time of the king’s death (2.3.54-61). To concentrate on these correspondences in further detail would go beyond the scope of this paper, however, it has become evident that Shakespeare operates to create clear, imaginative representations of characters within their environment. As he leads his viewers through Scottish moors, battlefields, forests, and castles, they experience mystery and fear, black magic, inescapable fate, solitude, and unavoidable death. Comparable sensations, but visual in character, are provided by the aforementioned painters.

Their works, this article claims, provide inspiration for Coen’s Macbeth, directly or indirectly, and they are a certain point of reference to analyse Shakespeare’s tragedy. As such, the paintings serve as an ‘intertext’ (Bal, 2006, p. 291) which stipulates the implied viewer to understand Coen’s version of the tragedy. The complexity of the multiple acts of framing (cf. Bal, 2006, p. 292) must be compared to the idea of reader-response theory or reception aesthetics which this article cannot address in detail. The references to artworks in Coen’s adaptation The Tragedy of Macbeth serve as vehicles of meanings and allow for alternative readings not only for the paintings but also Shakespeare’s text, including the characterisations of the tragedy’s dramatic figures. They are symbolically shaped by the portrayed landscapes.

Caspar David Friedrich In his Macbeth adaptation, Joel Coen reaches for the traditions of German Expressionism. However, it becomes clear that not only Expressionism, but also Romantic art, Realism, Impressionism, and Post-impressionism provide further inspiration, e. g. the works of Caspar David Friedrich. Competent viewers perceive allusions to Friedrich’s Woman at the Window (1822), Hutten’s Tomb (c. 1823/24), Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818) or The Dreamer (Ruins of the Oybin Monastery) (c. 1835). Among these iconographic quotations is The Abbey in the Oakwood (1809-1810). The painting seems to be the inspiration for a lonely, ruined hut standing at a crossroads in Coen’s adaptation of Macbeth. The configuration of elements in both the painting and the film sequence including its nightmarish atmosphere suggest the idea of loneliness, abandonment, transfiguration, and transformation. This transpires as the essence of Macbeth’s plot and the reference to Friedrich’s landscape strongly supports notions of change and it reflects the topic of political upheaval in Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

In his Macbeth adaptation, Joel Coen reaches for the traditions of German Expressionism.4 However, it becomes clear that not only Expressionism, but also Romantic art, Realism, Impressionism, and Post-impressionism provide further inspiration, e. g. the works of Caspar David Friedrich. Competent viewers5 perceive allusions to Friedrich’s Woman at the Window (1822), Hutten’s Tomb (c. 1823/24), Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818) or The Dreamer (Ruins of the Oybin Monastery) (c. 1835). Among these iconographic quotations is The Abbey in the Oakwood (1809-1810). The painting seems to be the inspiration for a lonely, ruined hut standing at a crossroads in Coen’s adaptation of Macbeth. The configuration of elements in both the painting and the film sequence including its nightmarish atmosphere suggest the idea of loneliness, abandonment, transfiguration, and transformation. This transpires as the essence of Macbeth’s plot and the reference to Friedrich’s landscape strongly supports notions of change and it reflects the topic of political upheaval in Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

Caspar David Friedrich’s oeuvre is dominated by landscapes. However, it is near impossible to identify specific places in the real world, as they seem rendered indistinguishable by the painter. Although Friedrich observes Nature and makes sketches and notes of realistic elements of the environment, his final works are ‘never a simple imitation of nature, but the result of a complicated interplay of visual impression and mental and emotional reflection’ (Wolf, 2020, p. 8). Wolf implies that Friedrich shares with his viewers a unique kind of landscape, a ‘moodscape’, an image visualizing a tangle of emotions located in our souls: ‘In Friedrich’s own words, a picture must be seelenvoll – literally ‘full of soul’ – in its effect if it is to meet the requirements of a true work of art’ (Wolf, 2020, p. 8). In this manner, the artist’s philosophy agrees with the general atmosphere that governs Romantic thought. Thus eventually, his works become imbued with spirituality and symbolism: ‘“With each passing year Friedrich wades ever deeper into the thick fog of mysticism; nothing is too mysterious or strange for him; he broods and struggles to pitch the emotion as high as possible,” ran one article in an issue of the Tübingen Kunstblatt of 1820’ (Wolf, 2020, p. 8). Art viewers are faced with the quintessence of loneliness, yearning for undefined fulfilment and hopelessness. By employing these references as frames, Coen brings to the surface ideas of solitude and individuality in Macbeth. The warrior and his wife are clinging to their own devices – ‘What cannot you and I perform upon/ Th’unguarded Duncan’ (1.7.70-71) –, and the film highlights how much both detach themselves from ordinary society and regulated politics. The transience of human existence is envisaged by placing human beings against the vast natural world, or lonely ruins of past greatness in desolated surroundings where people are presented as mere shadows.

The iconographic indication embedded in the presented screenshot [Fig. 1] can be interpreted as a reference to Friedrich’s The Abbey in the Oakwood (1809-1810) [Fig. 2]. The images share similar compositional arrangements with ruined buildings at their centre, comparable layouts, a parallel outline of clouds, light, and general symmetry. Friedrich achieves a certain balance in the painting by adding thickets, whereas in the film frame, mountains guarantee the symmetry of the composition. Friedrich’s landscape and the cinematic frame employ similar elements, a dry tree, ruins, and open passages through devasted constructions to evoke the feelings of fear, insecurity, a sense of threat and evil.

However, the artistic solutions concerning the light arrangements in the skies – its source situated behind the horizon – might be read as an indication of a positive alteration: ‘In Friedrich’s picture, lastly, the possibility of a better world seems to reveal itself only on the pale horizon, on the far side of history and death’. (Wolf, 2020, p. 34). In Coen’s film, the ruined cottage where Banquo’s son Fleance is imprisoned and thereby temporarily removed from the time frames of the story appears lit by such a pale horizon which seems to brighten Fleance’s future.6

Beyond the obvious compositional similarities, the resemblance of Coen’s screen shot to Friedrich’s painting also concerns spiritual spheres. Friedrich’s painting provides an atmosphere of religious nature, inevitable death, and the ephemeral passage of time. The ruined church is approached by a humble funeral procession. They pass through the gates, by the cross located in the archway. The group is moving towards the light brightening the horizon line. Referring to Christian beliefs, the image indicates that the cross signifies a passage from death to eternity, from misery to happiness. However, the very moment of passing seems to be removed from time, which might evoke reminiscences of Hamlet who claims that ‘The time is out of joint; O cursed spite/ That ever I was born to set it right!’ (1.5.186-187). The cinematic frame in Macbeth is deprived of any clear references to religion but yet retains a spiritual ambience. The hut, where Ross leaves Fleance under the wardenship of a sinister old man (the character is also performed by the female actor of the Weird Sisters, Kathryn Hunter), becomes an iconographic echo of Friedrich’s Gothic ruins, a place of transition. However, instead of the cross that ‘opens’ the passage between death and life, here the metaphysical corridor is malevolently blocked by the figure of Ross sitting at the gates of the dilapidated cottage. Thus, the pale form of ‘hope’ behind the ruined walls remains unreachable for Fleance to whom the witches had prophesied a redemptive, glorified future.

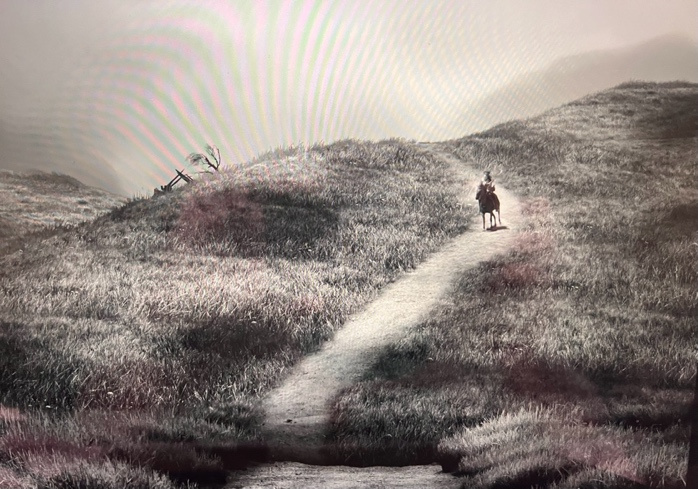

The idea of an inescapable fate, designed by external forces, is brought to the surface in both Friedrich’s and Coen’s images. There is an indication of only one possible path in the painting that runs through the ruins of the Gothic church. The film frame depicts three available roads, but viewers are inclined to select the middle path, as the compositional design enforces the visual trajectory. The sensation is additionally enhanced by a hidden source of light located in the mist behind the hut that attracts attention. Moreover, the less attractive side paths end in impenetrable mountains veiled in clouds. In Friedrich’s painting, options of movement are limited by the surroundings. Coen decides on a compositional solution that gives the impression of choice but is equally limited. The returning motif of three paths, i. e. three options, refocuses the attention on Macbeth’s scene when King Duncan dies. There are three possible ‘successors’ – two sons and Macbeth seem to take side roads that end in unavoidable destruction in foggy dangerous mountains [Fig. 1] or darkness [Fig. 2]. The third path is apparently blocked by the figure of Ross but becomes the gate to transformation. Fleance, Banquo’s son to whom the Weird Sisters prophesy the crown (1.3.67), enters this gate, accompanied by eerie Ross, and is diverted from his path. Eventually, there is neither redemption nor resurrection for Scotland.

As in Shakespeare’s text, the transformation will concern the very country, as the reader is presented with pathetic fallacies on the macrocosmic unruliness: ‘chimneys were blown down; […] Lamentings heard i'the air; […] some say, the earth / Was feverous and did shake’ (2.3.55-61). Mirrored by a microcosmic correspondence to this chaos, the country of Scotland is shaken when the king dies: ‘Most sacrilegious murder hath broke ope / The Lord's anointed temple’ (2.3.67-68). At this point the text interacts with religious references, as the sacred life of the king is violently extinguished by his brother(s)-in-arms, or brother(s)-in-blood. If this catastrophe is approached via the religious context of Christ’s death, it could be interpreted as an opportunity for redemption. However, the death of Duncan, whose ‘wine of life is drawn’ (2.3.96), does not provide this option. Friedrich’s painting approached within the frames of Coen’s adaptation suggests that the violent death of the king seals the passage towards redemption and prevents the rebirth of Scotland. Neither Duncan’s sons nor Macbeth would cross the ruined gates and become a saviour for the country. In Coen’s adaptation, even Fleance is eventually deprived of this chance when kidnapped by Ross at the end of the feature.

The juxtaposition of these two rather sombre frames allows viewers to identify indications of change, superstition, redemption, and possible resurrection, all also embedded in Shakespeare’s dramatic text. In the film sequence taking place at the ruined hut, Ross and the old man both ruminate on the unruliness of the night: ‘I have seen/ Hours dreadful, and things strange’ (2.4.2-3). This indeed takes place during the night of Duncan’s murder. Illustrating this with Friedrich’s painting adds to the layers of desperateness. This also echoes the following lines from the play: ‘Nature seems dead, and wicked dreams abuse/ The curtained sleep. Witchcraft celebrates’ (2.1.50-51). Framing the scene with the Romantic painting underlines its otherworldly character. Reframing as an ‘act of interpretation was reinserting the image within a larger whole’ (Bal, 2006, p. 292). This is, as Bal defends her methodology, not ‘idiosyncratic. Instead, the image becomes a meeting ground where cultural processes can, precisely, become intersubjective’ (2006, p. 309). The interpretation of both images can therefore be used to define, reread, and rewrite impressions of death, destruction, decline of order, etc. appearing in Shakespeare’s tragedy Macbeth. Such a reading of Coen then supports and enhances the motifs governing the play, like a missed opportunity for rebirth and continuity. It highlights the implications of fruitless transformative events in the tragedy.

Vincent van Gogh, Wheatfield with Crows (1890)

Joel Coen uses an astonishing film technique: all Weird Sisters are portrayed by the same actor, Kathryn Hunter. She seems to be producing mirror images of herself and seems like a raven. An association between the Weird Sisters in Shakespeare’s Macbeth and corvids is not unusual regarding cinematic adaptations of Macbeth. In 1969, the same motif of a flock of blackbirds making loud and disturbing noises is used by Andrzej Wajda.7 As in Coen’s cinematic work, the director suggests to viewers that three women take the shape of ravens or crows after pronouncing their prophecies, and they appear above the heads of Macbeth and Banquo. However, Coen adds further insinuation linking corvids, witches, and yet another dramatic figure. In the closing scene, viewers witness an implied transformation of Ross – and Fleance – into a flock of noisy black birds emerging on the road among wheatfields. As such, three become one, one become(s) three, three become many, and many become one as if viewers were to identify Ross with Macbeth’s Hecate, a triple goddess of, among many, night, ghosts, and sorcery.8 The final part of Coen’s cinematic work adopts Vincent van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows (1890) [Fig. 4] to evoke parallels between the readings of the black birds as Weird Sisters and Ross.

Vincent van Gogh, in one of his letters to his brother Theo, writes the following lines about Wheatfield under Thunderclouds (1890) and Wheatfield with Crows (1890): ‘They are immense stretches of wheat under turbulent skies, and I did not have to strain to express sadness […] extreme solitude’ (Graetz, 1963, pp. 272-273).9 The artistic means used in the paintings reveal the artist’s objectives and the mood he probably intends to share. Moreover, when carefully approached, the painting discloses its strange, symbolic, and prophetic significance, characteristic of any other of van Gogh’s landscapes. Ingo F. Walther claims that when looking at Wheatfield with Crows [Fig. 4], viewers experience a vague feeling of unease caused by the lack of a defined horizon line (2001, p. 84). The balance in this composition is disturbed by the layout of colours and the prominent brushstrokes. The yellow of overripe wheat dominates; the warm hue is contrasted with a dark blue sky marked by two lighter spots. The blue paint covers merely one-third surface of the canvas. The indeterminate horizon, shifted decidedly upward, ‘is windswept and flooded by the mounting waves of the blazing wheat, large as a sea. The path in the centre […] has come to a dead end, barred by the fire which has taken possession of the whole field’ (De Leeuw, 1996, p. 500). The other roads to the left and the right – notably, this shows is another choice of three – sealed by the painting’s frame seem to end somewhere beyond in an unknown reality. The perspective of an open field is reversed; its lines, visualised by three divergent roads, meet in the foreground. The stormy sky and yellow field break apart abruptly (Walther, 2001, p. 84). A scattered flock of blackbirds seem to recede towards and beyond the horizon. Van Gogh’s birds remain rather complex but also ambiguous symbols:

The dark silhouettes of the crows were preceded by the loose branches […]. In their movement against the sky, they recalled the gesticulating branches of the tree, which, since his earliest drawings, had symbolised Vincent’s struggle. They are now completely detached and have become identical with the birds, traditional messengers, which were nearly always sombre in his paintings like the thoughts they carried. The few little birds […] the counterpart to the wheatfields, have become the stormy swarm of the huge crows, sinister and foreboding in their intense blackness (Graetz, 1963, p. 276).

Taking into consideration the artist’s inner struggle, Van Gogh’s birds are gloomy creatures, associated with death. They remain faithful to the literary and artistic tradition of depicting ravens and crows. James Edmund Harting, in his The Birds of Shakespeare: Critically Examined, Explained, and Illustrated (1871), explains the role and nature of these birds. They are supposed to bring news of death, fighting or vengeance (Harting, 1871, pp. 99-123). With references to their diet, a propensity to stay alone or as familiars in company of witches, and finally, their blackness (their colour and dark nature), ravens and crows are seen as evil creatures.

Coen unmistakably refers to van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows [Fig. 4]. Similar to van Gogh’s painting, the middle path in Coen’s Macbeth [Fig. 3] seems to end in prophetic mystery. The crows of van Gogh and Coen are free to fly towards the light in the dark sky. This could be compared to a ‘vision of resurrection’, – embedded in the last image of wheatfields by van Gogh as ‘his soul rises to the sky, symbolised by the light cloud just above the road which has come to its end’ (Graetz, 1963, p. 278).10 However, the crows seem violent, agitated, and unpredictable; the painting and the screenshot share an atmosphere of insecurity and mental struggle. Both squander the option of redemption because the birds never reach the bright horizon, they abandon this direction and turn to the right.11

Ravens function as oracles; they are ominous birds of death, messengers of misfortune. In antiquity, they belonged to Kronos / Saturn (Kretschmer, 2019, p. 335); Kronos is the God of Time, so one could suggest that ravens present the linearity but also the disruption of time. Taking his cue from the above idea and van Gogh, disruption can be seen as the ravens’ function in Coen’s Macbeth as they ominously fly through the setting in this film version of the tragedy. In the play, Lady Macbeth refers to the creatures with the following verses: ‘The raven himself is hoarse/ That croaks the fatal entrance of Duncan/ Under my battlements’ (1.538-40). The ominous birds therefore become omnipresent in the film, continuously implying doom. Coincidentally, they could, if these connotations are not adhered to, herald a new beginning.12 At the end of the film, they remain an incarnation of the Weird Sisters and depart in the direction of the light, unless – and this is the bleaker reading – they simply and irredeemably disappear and leave an uncertain, dire future.

Reframing Wheatfield with Crows with regard to Macbeth underlines that the existence of the corvids and three paths remains, one of which ends in desolation, or – as described above – in ruins.13 The association between the ravens and fatality provoked by the Weird Sisters echoes in Macbeth’s quote after the death of his wife: ‘The time has been, my senses would have cooled/ To hear a night-Shriek’ (5.5.10-11). This shriek reverberates in Coen’s Macbeth as caused by the birds.

Gustave Courbet and Claude Monet

In their paintings, the French Realist Courbet [Fig. 6], and the Impressionist Monet [Fig.7] render versions of the cliff at Étretat. Despite differences in style and technique, the artists manage to reveal the timelessness of Nature in her most powerful manifestations: the sea and the mountains. Monet’s seascapes result from an intense observation and are accompanied by passion and even a sense of danger (Wildenstein, 2022, p. 210). In the case of Courbet, his are more ‘an emotion than an observation’ (De Font-Reaulx, 2021, p. 33). Nevertheless, Nature’s endurance, her universality and the emotional charge become keys that open the way to further analyses. The decision of employing paintings to interpret characters also embraces possibilities for an enhanced reading of Lady Macbeth. Scenes depicting her at a cliffside in Coen’s film show clear references to Impressionist artworks, such as the paintings of Étretat. The following description is adequate for both Courbet’s and Monet’s appreciation of Nature:

Set in a recognisable geographical space, Courbet’s landscapes are free of temporal references, seemingly outside of time. They appear to be eternal; they have always been there, and they will never disappear. They seem to create a world that is both near and yet so far, delimited but open to an intense sensibility; they offer the possibility of unveiling both an archaic and modern form of nature. (De Font-Reaulx, 2021, p. 31)

The same notion of eternity, solidity and intimacy is captured by the cinematic shot depicting Lady Macbeth standing on the edge of a cliff [Fig. 5]. The stormy weather, the play of lights among dark clouds, and the firmness of rocks add a human figure that seems an elongation of the top front and thus fused with the cliff. The brighter cloud around Lady Macbeth could present hope and consistent confidence.14 However, the cliffside could also be seen as brittle, unsteady, and prone to erosion. Such framing confirms its nature as a ‘a constant semiotic activity, without which no cultural life can function’ (Bal, 2006, p. 300) – the references continue to historically link ‘invisible threads to other images’ (Bal, 2006, p. 301), like those of life close to the seaside.

Regarding the film scene, the association with nineteenth-century art pieces offers itself. Such paintings can provide a hint of hope for transformation and resurrection. Here, the chosen two artworks [Fig. 6-7] add to characterise Lady Macbeth with a notion of loneliness but at the same time strength and resilience. Both Courbet’s and Monet’s renderings of Étretat add layers of sturdiness, grace, and permanence to the mood. Macbeth’s wife becomes a natural continuation of a rocky cliff – a solid, eternal and (seemingly) unmovable foundation that stands against turbulent weather or restless waters. Lady Macbeth’s dark and dangerous desires seem to be reflected by the forces of nature.

Lady Macbeth is an ambitious figure who is acknowledged as the driving force in their marriage. She convinces her husband to commit regicide: ‘But screw your courage to the sticking place, / And we’ll not fail’ (1.7.61-62). She is the strong party in their marriage; she seems the steadfast rock while he needs to take the plunge into the abyss of murder. She persuades Macbeth in 2.7 to fulfil the witches’ prophecy through their own agency: ‘O never/ Shall sun that morrow see’ (1.5.60-6) and evokes ideas about the downfall of monarchy.

In the above scene, however, Lady Macbeth is alone when facing dangerous Nature. Consequently, the combination of the screenshot and the paintings mentioned reveal an overwhelming solitude of the Shakespearean female heroine: the convergence then includes her desire to confront her fate but it also draws attention to her exclusion from patriarchal court affairs. In this context, Lady Macbeth represents eternal Nature with a sensitive intensity who appears both near and yet so far (cf. De Font-Reaulx, 2021, p. 31). At the same time, Lady Macbeth – exposed, devoid of protection from the wind, and standing on a corroded part of the rocky cliff – can be read as destinated for destruction by the slightest gust of a storm.

Another decoding process allows the viewer to link this scene with Lady Macbeth’s death. Though the film later provokes thoughts that Lady Macbeth does not die because of her own inner turmoil, this scene seems to confirm a possible plunge from the cliff which parallelly could be read as a suicidal attempt. This has been one of the readings of her off-stage death, as the consequences of the couple’s action lead to a culmination of chaos ‘[o]f dire combustion and confused events’ (2.3.58). Such roughness might already be invoked by the unruly waves of Monet’s painting. To support this notion, Ross comments on the vagueness of circumstances: we ‘know not what we fear, / But float upon a wild and violent sea’ (4.2.20-21). Lady Macbeth on the cliff seems to reflect this unknown danger and to evoke a violent end.

The imbued metaphors take on meanings beyond the paintings and confirm different and added perspectives on the reading of Lady Macbeth. It is productive to analyse Coen’s adaptive process and draw further conclusions on the implications of character construction and proleptic application of frames.

Kazimir Malevich

In the works of Kazimir Malevich, the cinematic image of three witches disappearing into the mist [Fig. 11] could find its painterly extension and closure [Fig. 9]. Malevich’s scene not only corresponds to the chosen frame of the film but also offers a complementary perspective on the position of the Weird Sisters in Macbeth’s Scotland; especially concerning the final scene where Ross and, accompanying him, Fleance reappear as a flock of blackbirds [Fig. 8 and 10 below, Fig. 3 above].

As a reference to Shakespeare’s and Coen’s Weird Sisters, the painting Three Women on the Road (1930) [Fig. 9] becomes a natural continuation of the earlier pictures.15 The work from the 1930s is an instance of Post-Impressionism in the œuvre of Malevich. For this study, it is necessary to realise that the most intriguing aspects of the painting are to be discovered somewhere between pre-iconographic description and iconographic analysis (cf. Panofsky, 1955, pp. 28-29): a road dividing wide wheatfields, a consciously organised background with a slightly stronger focus on the right side of the image; three women placed in the central point of a well-balanced composition; sunny weather during the middle of the day; blue sky with several clouds whose silver linings seem shaped into white birds. Malevich reveals an idyllic (pastoral) nature of a rural environment. However, the longer the image is contemplated, the more disturbing it becomes. The three figures seem to approach the viewer. Their faces are stripped of all distinctive features and replaced by bright blotchy brushstrokes that could cause anxiety and unease. Compared with the Weird Sisters and an emblematic confrontation of their interchangeability – which is underlined by the triple casting of the female actor – and therefore facelessness, aspects of mutability and transformation lend themselves. The witches are ambivalent creatures who vanish into air and whose corporality melts (cf. 1.3.79-82) into the unknown.

Juxtaposed with the final frames of Ross and Fleance riding on horseback along a road between fields [Fig. 8], Malevich’s work further connects the indefinite and ambiguous creatures that are labelled as Weird Sisters with a flock of birds, as mentioned above. In Coen’s film, Ross seems to be elevated in importance and to have his own mischievous agenda and his scenes are so eerily cut that viewers are suggested to clearly associate Ross’ presence, motivation, and actions with the crow-like Weird Sisters and their supernatural forces. The three fading figures [Fig. 11], in an ominous cover of mist, change into black ravens [Fig. 10] with croaking sounds and flapping wings, which brings out the tragedy’s uncanny atmosphere of otherworldliness. A striking resemblance to this metamorphosis is experienced in the last scene of the film when the horse riders Ross and Fleance [Fig. 8] take the same sinister shape of blackbirds [see Fig. 3].16

Consequently, due to the similar composition and motif of Nature – including the continuous references to the eerie birds, – it is possible to establish a clear relationship between Malevich’s three women on the road and Coen’s Weird Sisters as well as the horse riders. The evocation of a comparison generates a constant threat of doom.

Conclusion

This article proposes new referential content by showing how Joel Coen’s Macbeth frames art and states how the decoding viewer of the film reframes and adds intertextual, intermedial, and interdiscursive references for an expanded ‘abstract, structural idea of narrative’ (Bal, 2006, p. 304). The engagement with the narrative frames connects with their reading of the film adaptation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Film adaptations limit a text just as its frames seem to limit the adapted images, but the film then empowers and enriches its interpretative reading through decoding. This in turn exceeds its limitations and permits new ‘propositional content’ (Bal, 2006, p. 304).

Regarding Coen’s Macbeth, the gallery of iconographic references expands the play by alluding to Romantic, Realist, Impressionist, Post-impressionist, and Expressionist artworks. These could be extended upon in another article. Every painting generates an authorial interpretation based on, first, iconographic analysis and iconological interpretation. Further to this, the interpretations result from the act of reading, for instance, the emotional condition and moods embedded in these artworks. This article focuses on landscapes by prominent European artists of the 19th and 20th centuries. They are approached regarding their archetypical, symbolic, and metaphoric potential. In Gustave Courbet’s or Claude Monet’s case, the paintings disclose Nature’s beauty, magnitude, and potency. As such, they add to the grandeur of Shakespeare’s gloomy political tragedy. The landscapes convey messages and, therefore, when the paintings are juxtaposed with cinematic frames taken from Coen’s adaptation of Macbeth and carefully analysed, viewers gain a critical perspective regarding both Coen’s interpretation of Shakespeare’s drama and the original dramatic text. The intentionally framed paintings thus serve as enabling tools to decode and understand Shakespeare. Their imbued metaphors take on meaning beyond the paintings in Coen’s cinematic adaptation and provide material to construct an enhancing analysis of Shakespeare’s drama.

Nature as a mysterious, spiritual entity plays a fascinating and invaluable role in this connection. Recruiting Friedrich and Van Gogh highlights the choices of a future that Macbeth seems to consider. The former draws the attention to the inescapable fate of Scotland in a spiritual context. Van Gogh confirms a religious connotation but adds ravens as anthropomorphic representations of human entities. Courbet and Monet attach visual characteristics and expose a character’s weaknesses and strength; simultaneously they underline how nature becomes an important factor in the tragedy, which the correspondence of the weather highlights. Lastly, Malevich adds to an exposure of the Weird Sisters and how their features highlight disturbance and ambiguity in Macbeth’s Scottish society. The viewer is invited to empathise with these ambivalent creatures.

The exemplary paintings that this article identifies as sources of inspiration for the film, consider reading frames in new analytical circumstances (cf. the chart at the beginning of this article). Hereby, Joel Coen’s adaptation sheds a new artistic light on Shakespeare’s Macbeth. The juxtaposition of frames allows to identify indications of characterisation, transformation, or redemption, all embedded in Shakespeare but surfacing for the viewer in Coen. Defining and reframing symbolically charged landscapes and thereby rereading impressions of death, decay, and destruction in Shakespeare’s Macbeth become apparent. They are shaped by the portrayed landscapes. Together, Coen’s film – including the recognition of these paintings in their customary and reframed meanings – allow for an interdisciplinary understanding of Macbeth for the viewer who would not draw such conclusions without the film. The paintings provide and additional angle to approach and analyse Shakespeare.

Notes

This framing influences the reception of the film which corresponds to Linda Hutcheon’s idea that an adaptation reflects and creates responses: “the context in which we experience the adaptation—cultural, social, historical—is another important factor in the meaning and significance we grant to this ubiquitous palimpsestic form” (Hutcheon, 2012, p. 139).

The progress of landscape-paintings into an independent genre has been dated as originating in the 1500s: “It is conventionally reckoned that the decisive shift of emphasis to landscape becoming the dominant motif took place early in the 16th century in Antwerp, the Danube area, and north Italy, notably Venice.” (Langdon, 2001, p. 404).

All definitions of different landscape types are introduced in The HarperCollins Dictionary of Art Terms and Techniques, edited by Ralph Mayer. Moodscapes are mentioned by Norbert Wolf in Caspar David Friedrich 1774-1840. The Painter of Stillness 2020.

German Expressionism as a source of inspiration explored by Coen is mentioned in several interviews and articles, for instance an interview by Hugh Hart who talks with production designer Stefan Dechant ‘The Tragedy of Macbeth’ Production Designer Stefan Dechant on Joel Coen’s Minimalist Masterpiece, published on 13.01.2022 ‘The Credits’. Available at: https://www.motionpictures.org/2022/01/the-tragedy-of-macbeth-production-designer-stefan-dechant-on-joel-coens-minimalist-masterpiece/ [Accessed: 2 November 2023].

The same German artistic movement is mentioned by Richard Brody in his article “The Tragedy of Macbeth,” Reviewed: Joel Coen’s Sanitized Shakespeare published in The New Yorker on 25.12.2021. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-front-row/the-tragedy-of-macbeth-reviewed-joel-coens-sanitized-shakespeare [Accessed: 2 March 2023]. In another interview conducted by Adam Woodward, Stefan Dechant, the Production Designer admits the following ideas: ‘From the beginning we talked about wanting the imagery to be very abstract. We discussed what German Expressionism had meant for filmmaking, and how it influenced people like Charles Laughton when he was making The Night of the Hunter. We looked at Carl Dreyer and FW Murnau, and we also looked at Hiroshi Sugimoto’s photographs of architecture, and Casa Luis Barragán in Mexico, which is just two slab walls and a square tower. Joel was immediately saying ‘I think that could be Inverness’. That then led us onto a conversation about a 20th century theatre designer named Edward Gordon Craig, who created these very abstract, geometric designs. That was just our first conversation.’ (Joel Coen: How we made The Tragedy of Macbeth, ‘Little White Lies’ 14.01.2022. Available at: https://lwlies.com/interviews/joel-coen-the-tragedy-of-macbeth-making-of/ [Accessed: 3 March 2023].

See Umberto Eco’s or E.H. Gombrich’s distinction between competent and naïve readers/viewers in On Literature by Umberto Eco (2002), p. 220, and in Art & Illusion. A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation by E.G. Gombrich (1960), pp. 155, 169.

As such, the frame serves as an act of appropriation and thereby adds layers to its interpretation.

The scene appears in the 04:05 minute of the TV theatre production directed by Andrzej Wajda and released in 1968, with the main roles played by Andrzej Łomnicki as Macbeth, Magda Zawadzka as Lady Macbeth and Daniel Olbrychski as Banquo. The production is available on the platform © 2023 Telewizja Polska S.A. https://vod.tvp.pl/teatr-telewizji,202/makbet,339666 [Accessed: 3 March 2023].

Later, the idea of transformations is presented again, then based on Malevich paintings.

A letter to Theo van Gogh and Jo van Gogh-Bonger. Auvers-sur-Oise, on or about Thursday, 10 July 1890.

According to another archetypical meaning of blackbirds, they are associated with “the early, undifferentiated, but feminine, cosmic state. […] crows and ravens, because of their black colour, are symbols of the idea of beginning, of primordial darkness, maternal darkness, and fertilising earth” (Werness, 2006, p. 106).

Macbeth repeats “Tomorrow, tomorrow, tomorrow” which is identified with ravens’ screams “cras, cras, cras” as this means “tomorrow” in Latin (Forstner, 1990, p. 238).

In the mentioned above letter Vincent adds: "I almost think that these canvases will tell you what I cannot say in words, what I see as healthy and strengthening in the countryside." (Graetz, 1963, pp. 272-273). Thus, there is still hope in van Gogh's work.

In art tradition, an image of ruins also holds symbolic meanings: “These ruined places were thought to be places of magic, terrible warnings to living humans and the haunts of ghosts and evil spirits.” (Cooper, 2018, website)

An alternative and more telling is the interpretation of Macbeth’s frame in the context of Gustave Doré’s illustration of Milton’s Paradise Lost of Satan Overlooking Paradise. To include another illustration here would have exceeded the scope of this paper, however, in the frame, Lady Macbeth, standing on the edge of a cliff, faces the mighty, destructive Nature (dark clouds may suggest stormy weather). Situated on a similar rocky edge, Satan admires the power and beauty of Paradise. That is the time when the fallen angel has a chance to rethink his decisions, turn back from the path of evil and ask for forgiveness: “Satan is shown [by Doré] as a small figure, almost overwhelmed by the vastness of the space around him. Also, placing him at the edge of a large cliff gives him a commanding presence over the landscape, as if to highlight the gravity of his actions and the profound effect they will have on the story. […] Milton chose a mountaintop for this crucial moment […] and the verticality of the scene gives it a weight that wouldn’t be present if he was at ground level.” (Botham, 2021, website)

In another of Malevich’s painting, Bathers (1928-1929), Malevich presents three white female characters ‘two of which have whited faces, […] set into a landscape with compositional […] water complicating the relationship between foreground and background […]. This affinity is augmented by the awkward poses of the bathers, which agitate a potentially straightforward calm landscape scene’ (Crone and Moos, 2014, pp. 39-41). The contrast emphasises the juxtaposition of two realities. Because the work covers an impossible transition, viewers experience sufficiently disturbing sensations. In the context of Macbeth, the witches are as solid as the bathers in Malevich’s painting. Thus, when the frame and the picture are placed together, Malevich’s work reveals an oddity of three cinematic incarnations of Shakespeare’s Weird Sisters. The image of Coen’s witches acquires a new dimension of an ongoing process of transformation and transition.

In Herder-Lexicon, Symbol ‘mist’ represents a place of transition between various states/ dimensions; in Cooper’s An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Traditional Symbols, the “mist” (a religious context) is associated with ‘initiation; the soul must pass out of the darkness and confusion of the mist to the clear light of illumination (106); finally, The Book of Symbols where we learn that “a [Scandinavian] mythical wasteland of freezing mist and fog populated by monsters, also included the realm of the dead” (76); in general mist/ fog is closely related to death, demons, magic, as well as, transition or transformation.

Shakespeare, ´if that an eye may profit by a tongue’

2|2024 - sous la direction de Jean-Louis Claret

Shakespeare, ´if that an eye may profit by a tongue’

Du texte de théâtre à l'image

Quelques pièces et leur/s image/s

L’âne et la fée : la métamorphose de Nick Bottom dans le Songe d’une nuit d’été

‘This is a strange thing as e’er I look’d on’

‘We speak of Lady Macbeth while in reality we are thinking of Mrs. S.’

Le regard de Fuseli

Fuseli’s Macbeth: bringing « the unclear » to light

The Shakespearean painter Johann Heinrich Füssli defying French classicism in theory and practice

En passant par le cinéma

Champ de blé aux corbeaux: The Tragedy of Macbeth (2021) by Joel Coen

The unsettling mise-en-scène: Shakespeare’s Macbeth as seen through Kurosawa’s and Welles’s lenses