This paper was presented at a conference entitled ‘Literature and Politics–intermedial perspectives’ at the University of Berne in October 2023. I would like to express my gratitude to Sophie Stokes-Aymes, Anne-Cécile Guibard, Alice Breathe and Lukas Aresta for their corrections and remarks.

In Zurich the multitalented Füssli1 was strongly influenced by two literature professors, Johann Jakob Bodmer and Johann Jakob Breitinger who promoted English sensualism against the ideals of French classicism.2 Their claim that, next to the representation of the possible, the marvellous should find its way into literary and pictorial practice would particularly influence Füssli.3 They put this idea into practice by translating Milton and mostly forgotten medieval literature which made strong impressions on the young Füssli.4 This authentic interest for English literature clashed with the approximative German translations of Shakespeare and the very loose interpretations of the plays on the European mainland. Even though the 21 performances of Shakespeare’s plays staged between 1757 and 1760 were a major cultural event in eighteenth century Zurich, as the number of tickets sold proves,5 the German translation of Shakespeare by Wieland provoked harsh critique. Füssli wrote in a letter to Bodmer: ‘I wished Wieland would be consumed be a Swabian flame, before he touches on Shakespeare with unholy hands’.6 Moreover, the way of presenting Shakespeare on stage made Füssli rather unhappy. In contrast to English interpretations of Shakespearean plays, the European mainland adapted them quite massively to the French ideal of classicism. There were of course content-based adaptions, but also more pragmatic ones. The Elizabethan theatre allowed quick scene changes, which wasn’t possible in theatres with heavy backdrops.7 Füssli, who learned English early, which at the time was unusual in Switzerland,8 read Shakespeare in the original language and had therefore good reason to be dissatisfied with the European interpretation of Shakespeare.9

Füssli’s works show to what extent these misinterpretations of Shakespeare could be considered as an aesthetic shock which became a stimulating force for his ambitions in all the artforms he practiced throughout his artistic career.10 To this aesthetic background should be added the political one. During the Seven Years’ War, in which the French and the English fought each other from 1756 to 1763 in Europe and the colonies, performances of Shakespeare’s plays defy the classical dramatic unities (time, place, action) as well as the French rules of vraisemblance and bienséance, which one could translate as plausibility and decorum. According to the tradition of the Horatian precept ut pictura poesis, those rules were also applied to visual art.11 In this context of rivalry, fans of Shakespeare would logically question those rules and turn into opponents of ‘political and literary absolutism’.12 Shakespeare’s plays became a key element of the new English national identity.13 We will see that Füssli, who was called ‘Shakespeare’s painter’ by Lavater in a letter to Herder as early as 1772,14 detaches himself artistically from the classical rules. In considering Füssli’s oeuvre as the response to an aesthetic shock caused by classical misunderstandings of Shakespeare’s plays, we can see several dimensions of aesthetic subversion in his theoretical and artistic works. His life between two countries and the dual influences on his work of classicism ‘à la française’ and British sensualism may explain his choice of genre. Aphorisms stand mid-way between the forming of an idea and its literary development.

Füssli’s aphorisms express the relation between art and nation

According to the twentieth century Füssli scholar Eudo C. Mason, Füssli’s aphorisms are very classic and conventional, in the art historical tradition of Mengs and Reynolds.15 The main concepts use the aesthetic terminology of the Enlightenment.16 Mason points out the lack of more radical, dynamic, romantic ways of speaking about art as it had been practiced since the 1750s in Germany and later in England. This seems surprising because the first edition of the aphorisms was published in 1788 and the second extended version in 1818. In those intervening thirty years, Füssli continued working on the aphorisms and they became his favorite writing project.17 Mason presents Füssli as an old-fashioned classicist, at a time when new words and concepts were already circulating.18 It is possible to nuance Mason’s claim by taking a closer look at some of the aphorisms19 which explore the analogy of aesthetics and politics against the foreseeable, calculated and academic effects of art.

Aphorism 110 for example shows how critical Füssli was when it comes to artistic rules:

The epoch of rules, of theories, poetics, criticisms in a nation, will add to their stock of authors in the same proportion as it diminishes their stock of genius: their productions will bear the stamp of study, not of nature; they will adopt, not generate.20

The clear link between poetics and nation shows that such a conception of literature can lead to cultural chauvinism. Füssli claims that less theory means more artistic freedom for the individual. The French, who are so attached to poetical theory as delineated by Boileau in his Art poétique, are implicitly characterized as incapable of producing artists of genius, as implied by ‘It diminishes their stock of genius.’ Aphorism 151 states the superiority of observation over academic precepts:

The rules of art are either immediately supplied by Nature herself, or selected from the compendiums of her students who are called masters and founders of schools. The imitation of Nature herself leads to style, that of the schools to manner21.

Superficially objective, the aphorism ranks a nature-based art production above academic training. Observe the repeated capital letter in ‘Nature’ that leads to ‘style’ in opposition to ‘manner’ in the quote. The emphasis on the difference between national poetics turns into an analogy in aphorism 130. Füssli finds a way to express those differences by means of political analogy as well. He uses moments in Roman history to illustrate the importance of knowing when to stop working on a piece of art:

He is a prince of artists and of men who knows the moment when his work is done. On this Apelles founded his superiority over his contemporaries; the knowledge when to stop, left Sylla nothing to fear, though disarmed; the want of knowing this, exposed Cæsar to the dagger of Brutus.22

The phrase ‘prince of artists and of men’ establishes the analogy between art and politics, between the Greek painter Apelles and the Roman general Sylla. This is not the only aphorism to use examples from ancient history to illustrate an aesthetic observation. Number 147 puts the analogy of society and art into a concise form: ‘Ancient art was the tyrant of Egypt, the mistress of Greece, and the servant of Rome’.23 The personification of art is a way to illustrate the dependency of art and nation. From Füssli’s point of view, the artistic phenomenon in all its aspects tells something about the society producing it. As an artist of the in-between, he is aware of differences and transformations from one aesthetic philosophy to another. In his paintings and drawings, the artist takes his distance to concepts of classicism by challenging the three classical unities, as well as the rules of vraisemblance and bienséance.

Füssli transgressing the unities

When it comes to Füssli’s main activity as a painter, we can observe how Anglo-French rivalry affects his art. Füssli challenges the prescriptive theory of the three unities of time, place and action. How does his oeuvre extend the conception of unity of time? Füssli wrote in aphorism 239 that the climax of the pictorial arts is reached ‘when they give wings to marble or canvas and from the present moment rays back to the past and forward to the future’.24 This means that pictorial art has the potential to integrate past or future events in one canvas and therefore to undermine the unity of time. This form of pictorial foreshadowing or flashbacks can be examined by the means of intermedial narratology.25 In his representations of the three witches from the play Macbeth, Füssli chose a supernatural and mystic moment.

It is a major moment in the first act of the play which corresponds to what he theorizes as a ‘middle moment’.26 The witches predict that Macbeth will become king. He is gripped by the desire for power and glory. The three witches and their prophecy are putting mischief into operation. Lady Macbeth contributes to this fatal dynamic and pushes Macbeth to kill King Duncan. In the tribulations even his friend Banquo gets killed. Macbeth visits the witches a second time in the third act. Tyranny, madness and suicide are the consequences. How does Füssli transpose those elements in his painting? The witches’ index fingers and gazes unanimously point at the future assassin and illegitimate king. The two warriors are brought face to face with otherworldly apparitions whose pointing fingers challenge them directly. The gesture of putting a finger to their mouth, shared by all three witches, symbolizes their unanimous opinion. Macbeth and Banquo are also unanimously troubled by the witches’ predictions. The gesture symbolizes what a painting is for the viewer: a mute code calling for an interpretation through imagination, this highly valued activity that was theorized by Füssli’s early poetic teachers, Bodmer and Breitinger.27

There are several versions of this scene. The first one, painted in 1783 (fig. 2), is a close-up of the witches, holding one finger to their lips while pointing with two fingers at something out of the frame. Here the light comes from the front: the witches’ gestures and facial expressions are perfectly highlighted. The death-heads hawkmoth flies in the direction pointed, materializing the disastrous prediction of the witches. The painter depicts the foreshadowing of future events through gazes, index fingers and the direction in which the insect flies. The parallels between gazes, gestures and light emphasize that the scene is treating the future, we could call it a pictorial foreshadowing.28 Thanks to the spectator’s interpretation and literary knowledge about the play, the painter increases the temporal intensity. Füssli uses this kind of strategy to simultaneously convey a sense of present and future and to challenge the notion that the subject of a painting, even more so than that of a play, should be restricted to a single moment in time.

The other two classical unities of place and action are transgressed in the images of dreams particularly, as Füssli does in ‘Titania and Bottom’ (fig. 3), which represents a lot of figures from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The different figures and groups display several narrative layers which find their place around the two protagonists in the centre of the picture: Titania drugged by a love potion and Bottom transformed into a donkey. The figures belong to different spaces and actions which allow an intermedial reading of Füssli’s painting which transmutes a scene of a Shakespearean play into visual art.29

Through imagination – the most important talent painters and poets must possess in the conception of Bodmer and Breitinger,30 the canvas contains not only copies of the natural but also of the supernatural and of the marvellous. Füssli transposed it into theory in a lecture at the Royal Academy:

Form, in its widest meaning, the visible universe that envelopes our senses, and its counterpart the invisible one that agitates our mind with visions bred on sense by fancy, are the element and the realm of invention; it discovers, selects, combines the possible, the probable, the known, in a mode that strikes with an air of truth and novelty, at once.31

One might argue that the classical rules had little impact in England. Indeed, theorists such as Samuel Johnson or John Dryden dismissed them as unessential for drama. The distance between literary practice and the ideals of French classicism increased in France too: in the period of anglophilia in the mid-eighteenth century, leading authors like Voltaire and Diderot also explored new ways of literary expression.32

Another principle linked to the three unities is what the French call vraisemblance. In English we could translate it as ‘likelihood’ or ‘plausibility’ meaning that a representation should be believable, intelligible, should stick to the real world, and should be comprehensible within the shared cultural background of the spectators.

Füssli’s art passes over concepts of vraisemblance and bienséance

The transgression of the principle of likelihood (vraisemblance) is evident. The most striking in the interpretations of Shakespearean plays by Füssli is his preference for the supernatural appearances like ghosts, witches and fairies. Since his first sketches Füssli loves ghosts; especially in combination with the classical elements which coexist with the supernatural, as in one of his early drawings ‘The apparition appears to Dion wielding a broom,’ or less repetitively ‘Spectrum Dioneum’ (fig. 4) from 1768. The drawing clearly indicates the classical source; from his reading of Plutarch’s ‘Life of Dion’ Füssli chooses a supernatural episode. The chosen moment of the apparition shows a fury, a creature from Greek mythology, wielding a broom, her hair resembling flames, imitating the line of beauty theorized in the figura serpentinata in a long tradition since Michelangelo.33 This classic element can be considered a first sign of the influence of Joshua Reynolds who’s known for his admiration for the Renaissance masters and his collection of Michelangelo drawings.34 Reynolds’s influence is important for a whole generation of artists which was deeply inspired by the “immediacy of Michelangelo’s art that ignited their burning ambition’.35 Reynolds suggests to them not to imitate but to admire and only to borrow from Michelangelo as practice.36 Füssli perfected through his career this new pictorial language culminating in his ambitious Michelangelesque ‘Milton Gallery’37 finished in 1799. The drawing of ‘Spectrum Dioneum’ is part of this evolution of Füssli’s art.

Beside the classical forms, the supernatural is omnipresent in this drawing. The classical and the gothic do not coexist harmoniously. The closed eyes of the sculptures contrast with the scared opened eyes and mouth of Dion. The harmony of the drapery exposed in Dion’s cape and in the curtain behind him changes into irregularity in all objects that are about to be transformed. Dion is surrounded by neo-Roman furniture that gives place to supernatural figures. In an excellent article, Laurent Bury lists several other elements which show the painters predilections for supernatural apparitions.38 The clash of supernatural and classical elements is symbolized by the terrific head of a snail emerging, mouth wide open, next to the fury wielding a broom, the dolphin at the corner of the table, the face of boar as a base of a Greek vase in the background and the pillow supporting Dion’s right foot, which seems to be coarsened into a paw.39 Those monstrous transformations within a classical framework create a new aesthetic space of transgression.

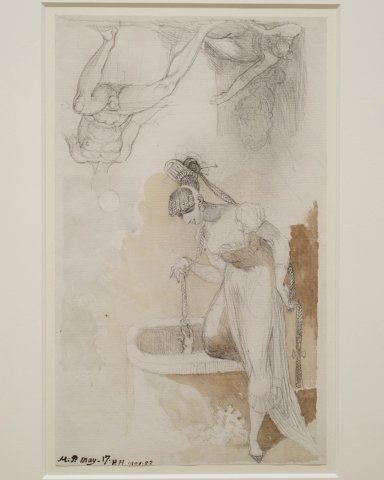

The last classical principle is bienséance or decorum in which the rules of politeness express the respect for morality and norms shared by a part of society. Füssli also transgresses this ideal, especially in his drawings of dominant female bodies with extravagant hairstyles (fig. 5-7). Those drawings do not depict idealized, graceful female bodies in the academic style exercised by copying Greek statues. But they display women in corsets, in ribbons, wearing dresses with ornamented sleeves and pointed shoes, their heads topped with complex hairstyles.40 David H. Solkin characterizes these drawings as ‘secretive and vaguely threatening’ and as blatantly violating moral rules which contrasts with the submissive, eroticized female bodies represented by painters such as Boucher, Fragonard and Ingres.41 The rococo and libertine painters Boucher and Fragonard paint women exposed to male gazes. Ingres, formed in the cercle of David, paints female portraits and odalisques in a conventional manner. This is not what Füssli does in the same historical period. He depicts socially provocative female figures.42 The flamboyant hairstyles, the challenging gazes show confidence, either by facing the spectators or by ignoring them artistically; the women control the erotic and mystical ambiance.

Conclusion

The aesthetic shock caused by European mainland misinterpretation of Shakespeare is one possible explanation of Füssli’s lifelong aversion towards classical and dogmatic art conceptions. As an aphorist he theorizes his opposition to academic notions of art and indicates his conviction that national particularities bring out more or less brilliant ways of aesthetic expression. And he puts his theories into action: he systematically undermines the three classical unities and transgresses the ideals of polite society in his art. The fact that an Anglo-Swiss artist disobeyed all these rules in his entire oeuvre from his early drawings to his late aphorisms shows his will to elaborate new principles based on the potential of imagination.

Bibliography

BODMER und BREITINGER, Schriften zur Literatur, Stuttgart, Reclam, 1980.

BURY Laurent, « L’homme qui aimait les spectres », Sillages critiques, 8, 2006, p. 85-99.

DERWENT, Lord, « Johann Heinrich Füssli: peintre anglo-suisse », Neue Schweizer Rundschau, 9, 1942, p. 545-561.

FEND, Mechthild, « Zeichnen und Ondulieren. Fetischismus, Künstlichkeit und die Freuden der Zurschaustellung », Füssli : Mode-Fetisch-Fantasie, David H. Solkin, dir., Zürich, Scheidegger & Spiess, 2023, p. 47-65.

FRIEDLAENDER, Walter, «Die Entstehung des antiklassischen Stiles in der italienischen Malerei um 1520», Repertorium für Kunstwissenschaft, 46, 1925, p. 49-86.

FRIES, Katja, « Maniera Moderna: intermedial aesthetics in the theory and work of Henry Fuseli (1741-1825) », xviii.ch Swiss Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, Basel, Schwabe, 2023, p. 5-29.

HOCHHOLDINGER-REITENER, Beate, « Shakespeare’s Maler Johann Heinrich Füssli und das Londoner Theater », Füssli- Drama und Theater, Reifert, Eva/Blank, Claudia Blank, dir., Kunstmuseum Basel, München, Prestel, 2018, p. 59-76.

HONOLD, Alexander, « Handlung, Szene und Momentum–Johann Heinrich Füssli und die Literatur », Füssli– Drama und Theater, Reifert, Eva/Blank, Claudia Blank, dir., Kunstmuseum Basel, München, Prestel, 2018, p. 37-58.

KNOWLES, John, dir., The Life and Writings of Henry Fuseli, London, Colburn/Bentley, 1831 1818.

MASON, Eudo C., dir., Johann Heinrich Füssli Aphorismen über die Kunst, Basel, Schwabe, 2012.

MORTIER, Roland/TROUSSON, Raymond, dir., Dictionnaire de Diderot, art. « Angleterre », Paris, Honoré Champion, 1999, p. 28-35.

MUSCHG, Walter, dir., Heinrich Füssli Briefe, Basel, Schwabe 1942.

POSTLE, Martin, « Sir Joshua and his Gang: Blake, Reynolds and the Royal Academy », Interfaces. Image-Texte-Langage 30, 2010. Blake Intempestif / Unruly Blake, p. 111-123.

REIFERT, Eva, « Johann Heinrich Füssli- Grosse Literatur, sublime Gemälde », Füssli – Drama und Theater, Reifert, Eva/Blank, Claudia Blank, dir., Kunstmuseum Basel, München, Prestel, 2018, p. 19-35.

SCHABERT, Ina, dir., Shakespeare Handbuch, Stuttgart, Alfred Kröner Verlag, 2009.

SOLKIN, David H., « Zeichnen in einer Epoche des Luxus: Füsslis Frauen in ihrer Zeit », David H. Solkin, dir., Füssli : Mode-Fetisch-Fantasie, David H. Solkin, dir., Zürich, Scheidegger & Spiess, 2023, p. 15-45.

SUMMERS, David, « Maniera and Movement: The Figura Serpentinata », The Art Quarterly, vol. xxxv, 3, 1972, p. 269-301.

VOLTAIRE, « Dix-huitième lettre », Lettres philosophiques, Paris, Gallimard, 1986 1733.

WOLF, Werner, « Das Problem der Narrativität in Literatur, bildender Kunst und Musik: ein Beitrag zu einer intermedialen Erzähltheorie », Erzähltheorie transgenerisch, intermedial, interdisziplinär, V. Nünning/A. Nünning, dir., Trier, Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, 2002, p. 23-104.

WORNUM, Ralph N., dir., Lectures on Painting by the Royal Academicians, London, G. Bohn, 1848.

Notes

Füssli learned English, French, Italian, Latin, Greek and became pastor in 1761. He translated Winckelmann and J.-J. Rousseau among others, wrote poems in the style of Horace and Klopstock. The transposition of literature into painting became one of Füssli’s compositional strategies as it is explained by Eva Reifert (ed.), ‘Johann Heinrich Füssli- Grosse Literatur, sublime Gemälde’, in: Füssli – Drama und Theater, (ed.) Eva Reifert, München, Prestel, 2018, p. 22; and Lord Derwent, ‘Johann Heinrich Füssli: peintre anglo-suisse’, in: Neue Schweizer Rundschau, N°9, 1942, p. 547.

Beate Hochholdinger-Reitener, ‘Shakespeare’s Maler Johann Heinrich Füssli und das Londoner Theater’, in: Füssli- Drama und Theater, p. 61. The two authors published an essay intitled Die Discourse der Mahlern (1721-1723) inspired by John Addison’s journal The Spectator. See also Derwent, op. cit., p. 548: ‘[…] par l’impulsion que pendant toute cette période donnait la groupe des pontifes littéraires zurichois, Bodmer, Breitinger, Sulzer, Haller et Winckelmann contre le rococo français et le Franzosentum’.

Online : https://www.e-periodica.ch/cntmng?pid=alp-004%3A1941%3A9%3A%3A896.

Alexander Honold, ‘Handlung, Szene und Momentum–Johann Heinrich Füssli und die Literatur’, in: Füssli– Drama und Theater, p. 41: ‘In retrospect, the rehabilitation of imaginative power as explained in the writings of Bodmer and Breitinger proves to be a decisive condition for the beginnings of Füssli's crossings between literature and the visual arts’. All translations from German are by the author of this paper.

Hochholdinger-Reitener, op. cit., p. 61: ‘Especially Bodmer made a name for himself by translating Milton, Homer, medieval texts and by founding a publishing firm’.

Ibid., p. 62: ‘The troupe gave 21 performances in Zurich, always in front of sold-out audiences, according to the receipts’.

Letter from Füssli to Bodmer (in German), 7 February 1766, in: Heinrich Füssli Briefe, Basel, Schwabe, 1942, p. 123.

Hochholdinger-Reitener, op. cit., p. 63.

Eva Reifert, ‘Johann Heinrich Füssli- Grosse Literatur, sublime Gemälde,’ in: Füssli- Drama und Theater, p. 22.

Lord Derwant, op. cit., observes: ‘Quant à l'Angleterre, Füssli, déjà, à l'école, fit une traduction de Macbeth, en allemand, et Shakespeare le hanta une vie entière.’ p. 548.

I refrained from using the term of aesthetic ‘trauma’, although the fruitfulness of psychanalytic concepts applied to Füssli’s drawings is illustrated in the fresh off the press article from Mechthild Fend, ‘Zeichnen und Ondulieren. Fetischismus, Künstlichkeit und die Freuden der Zurschaustellung,’ in David H. Solkin (ed.), Füssli : Mode-Fetisch-Fantasie, Zürich, Scheidegger & Spiess, 2023, 47-65.

In the Discourse der Mahlern (Discourses of painters), for instance Bodmer and Breitinger regularly relate poetry and painting, see Bodmer und Breitinger, Schriften zur Literatur, Stuttgart, Reclam, 1980, p. 3: ‘I diligently use the metaphora that I borrow from the painters […] that every writer and speaker should trace the natural. A rule, which he has in common with the painters.’ And p. 101-102: ‘Nature has revealed all its treasures, even the most hidden ones, to the poet's and painter's arts before the outward senses.’ See also, Honold, op. cit., p. 43.

Ina Schabert (ed.), Shakespeare Handbuch, Stuttgart, Alfred Kröner Verlag, 2009, p. 610: ‘Shakespeare stands for the powerful independence of the English, for their resistance to political and literary absolutism’.

Hochholdinger-Reitener, op. cit., p. 63: Interpretations of Shakespeare became a counterpoint to the dominant French ideal of classicism. See also Derwent, op. cit., p. 551: ‘Comme l'Allemagne, comme la Suisse, on réagit contre un art, une littérature de cour, artificiels, jolis et guindés; on redécouvrit Shakespeare, Homère et Pindare’. See also Schabert, op. cit., p. 612: ‘In contrast to French classicism and absolutism, the image of a British Shakespeare characterized by an original striving for freedom, emerged around 1750’.

Letter from Lavater to Herder, 4 November 1773, in: Heinrich Füssli Briefe, Walter Muschg (ed.), Basel, Schwabe 1942, p. 168: ‘He is extreme in everything he does–always original; Shakespeare’s painter – nothing but an Englishmen and from Zurich, poet and painter’.

Eudo C. Mason, ‘Einleitung,’ in: Johann Heinrich Füssli Aphorismen über die Kunst, Basel, Schwabe, 2012, p. 23-24: ‘Indeed, both the form and the content of the aphorisms show strong conventional-classicist traits […] at every turn, one encounters echoes of representatives of the generation before Winckelmann like Joshua Reynolds (born 1723) and Mengs (born 1728); he primarily moves along the old lines and works with their concepts and thoughts.’

Ibid., p. 24: ‘The antiquated impression that Füssli's aphorisms initially make is due in no small part to the fact that he uses almost exclusively the aesthetic terminology of the Enlightenment’.

Ibid., p. 13: ‘The fact that he still did not publish the aphorisms during his lifetime was by no means due to indifference, but because they had become his favourite writings […]’.

Ibid., p. 25: ‘Whereas Weimarer Klassik, which emerged towards the end of the eighteenth-century as a reaction to the Sturm und Drang, largely used the newer, more dynamic aesthetic terminology, Füssli completely subscribed to the old classicism’.

I have not been able to examine the earliest editions of Füssli’s aphorisms. I quote from the 1831 reprint published online by The Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/38591/38591-h/38591-h.htm.

Henry Fuseli, ‘Aphorism 110,’ in: The Life and Writings of Henry Fuseli, John Knowles (ed.), London, Colburn/Bentley, 1831 1818, p. 104.

‘Aphorism 151,’ p. 117.

‘Aphorism 130,’ p. 110.

‘Aphorism 147,’ p. 116.

‘Aphorism 239,’ p. 149.

For more information on pictorial narrativity see Werner Wolf, ‘Das Problem der Narrativität in Literatur, bildender Kunst und Musik: ein Beitrag zu einer intermedialen Erzähltheorie,’ in: Erzähltheorie transgenerisch, intermedial, interdisziplinär, V. Nünning/A. Nünning (ed.), Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag 2002, p. 23-104.

Another newly printed article confirms the interest of an intermedial approach to Füssli’s oeuvre. See Katja Fries, ‘Maniera Moderna: intermedial aesthetics in the theory and work of Henry Fuseli (1741-1825)’, in: xviii.ch Swiss Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, Basel, Schwabe, 2023, p. 5-29.

‘Aphorism 96,’ p. 94: ‘The middle moment, the moment of suspense, the crisis, is the moment of importance, big with the past and pregnant with the future.’

Honold, ‘Handlung, Szene, Momentum,’ p. 54.

Gérard Genette calls it a prolepse.

For examples of intermedial micro-readings of Füssli’s paintings, see Honold, ‘Handlung, Szene, Momentum,’ p. 52-56.

Bodmer and Breitinger, ‘Einfluss und Gebrauch der Einbildungskraft,’ p. 35: ‘When the imagination is so richly filled, it must necessarily have a marvellous influence on a piece of writing, enlivening it with vivid images and paintings.’

Füssli, ‘Lecture III: Invention,’ in: Lectures on Painting, Ralph N. Wornum (ed.), London, G. Bohn, 1848, p. 409. The italics are in the original.

Voltaire, ‘Dix-huitième lettre,’ in: Lettres philosophiques, Paris, Gallimard, p. 128: ‘Les monstres de Shakespeare plaisent mille fois plus que la sagesse moderne’. In spite of his early admiration for Shakespeare, Voltaire turns out to be very anti-Shakespearean later in his literary career. See also Dictionnaire de Diderot, Roland Mortier and Raymond Trousson (ed.), art. ‘Angleterre,’ Paris, Honoré Champion, 1999, p. 28-35.

On the serpentine line, see David Summers, ‘Maniera and Movement: The Figura Serpentinata,’ The Art Quarterly, vol. xxxv, no 3, 1972, p. 269-301; Walter Friedlaender, ‘Die Entstehung des antiklassischen Stiles in der italienischen Malerei um 1520,’ Repertorium für Kunstwissenschaft, 46, 1925, p. 4.

Martin Postle, ‘Sir Joshua and his Gang:’ Blake, Reynolds and the Royal Academy. In: Interfaces. Image-Texte-Langage 30, 2010. Blake Intempestif / Unruly Blake, p. 111-123, p. 114.

Ibid., p. 115.

Ibid., p. 114: ‘Significantly, it was not until Reynolds had himself ceased to paint that he confessed the depth of his admiration for Michelangelo, casting himself, not as one of his “imitators” (despite “borrowing” the attitudes of his various figures over the years) but as one of his ‘admirers.’

Ibid., p. 115.

Laurent Bury, ‘L’homme qui aimait les spectres,’ Sillages critiques, 8, 2006, p. 85-99. According to Bury, Füssli was in this period of the late 1760s influenced by the neo-classic virus which coexisted in his artistic production with the gothic style he elaborated during his stay in England in 1763.

Ibid., p. 86.

David H. Solkin, ‘Zeichnen in einer Epoche des Luxus: Füsslis Frauen in ihrer Zeit,’ in David H. Solkin (ed.), Füssli: Mode-Fetisch-Fantasie, Zürich, Scheidegger & Spiess, 2023, p. 16.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Shakespeare, ´if that an eye may profit by a tongue’

2|2024 - sous la direction de Jean-Louis Claret

Shakespeare, ´if that an eye may profit by a tongue’

Du texte de théâtre à l'image

Quelques pièces et leur/s image/s

L’âne et la fée : la métamorphose de Nick Bottom dans le Songe d’une nuit d’été

‘This is a strange thing as e’er I look’d on’

‘We speak of Lady Macbeth while in reality we are thinking of Mrs. S.’

Le regard de Fuseli

Fuseli’s Macbeth: bringing « the unclear » to light

The Shakespearean painter Johann Heinrich Füssli defying French classicism in theory and practice

En passant par le cinéma

Champ de blé aux corbeaux: The Tragedy of Macbeth (2021) by Joel Coen

The unsettling mise-en-scène: Shakespeare’s Macbeth as seen through Kurosawa’s and Welles’s lenses