Cartouche for the façade of the Jesuit church in Antwerp - Rubens

We saw in previous lessons how the device of the Voltairean tale was organized in three planes, which could be summarized as the 3 F : the façade, the fadaise and the background.

Facade is first and foremost, in a visual sense, the view offered by the surface of the narrative, the beautiful appearance, the shiny lure, the varnish that covers reality. We studied one of the most famous façades, the one that opens chapter III of Candide : " Nothing was so beautiful, so lithe, so brilliant, so well-ordered... ". This is the front line of soldiers advancing for battle as if on parade. And we have seen that the logic of the parade orders the whole beginning of this chapter. But the façade is also, in the Freudian sense, the façade of the witticism: its brilliance, its fleeting effect of meaning in nonsense, produces a façade that protects the speaker and behind which he takes shelter. The facade can be seen in the point that closes a chapter. For example, at the end of " Nez ", Zadig's formula produces the façade of the witticism : " the project of cutting off my nose is worth that of diverting a stream ". By incongruously correlating two vivid, concrete and seemingly unrelated images, Zadig forces the reader to disengage from the sinuous narrative sequence that actually links the two events they depict, and to stop at the comicality of the pairing. He laughs at the nose with the creek: the bon mot undoubtedly contains a moral, but doesn't dwell on it, leading us to pass on, to link up. The truth undoubtedly lies elsewhere.

Fadaise is the muddle of infinite discourse that leads our attention astray and disconnects us from any form of reality1. This discourse is represented in Candide by Pangloss and his metaphysical-theological-nigology. But more profoundly, any discursive sequence that turns empty is fadaise : Astarté recounting the infinite twists and turns of the Babylonian wars, in the chapter of " Basilic ", spouts a tale of fadaise. There is narrative nonsense as well as philosophical nonsense. What's at stake in fadaise is the derangement of causality in the event. Causality goes round in circles, constitutes a rhetorical-logical system disconnected from reality.

Useless books (Brant, Das Narrenschiff, Basel, 1494, F4v)

Finally, the background must be understood both concretely and spatially, as what's at the back, in the wings and behind the scenes ideologically, as what constitutes the bottom of things, the raw and incomprehensible horror of reality, irreducible to any form of discourse economically, as money, the sinews of war, the principle of interest underlying fine speeches. The bottom line is what the text is aiming at : chapter 19 of L'Ingénu is organized around Mlle de Saint-Yves's phrase, addressed to M. de Saint-Pouange's messenger and surprised by L'Ingénu, " you give me death ". This cry from Mlle de Saint-Yves's heart awakens " in the depths of her heart [...] a secret feeling ". The word connects two bottoms; it carries death, and this death is the mark of reality. The word is not pronounced /// in the common space of the joyous table celebrating the Ingénu's release from prison and the lovers' reunion: the beautiful Saint-Yves has been pulled aside (p.124). This gap marks the distance from the banquet façade to the background of the word of death. Similarly, in heroic butchery, a gap is marked from the brilliance of battle (despite the impressive, but abstract, sum of its dead) to the horror of carnage outside the limelight, in neighboring villages where no laws of war regulate the slaughter.

These three shots are struck by the double denial of the tale, which I've summed up with the formula it is not true that this is not a tale. This is how the façade is not given to be seen as not being the façade, how the fadaise is not told as not being a fadaise, how the background does not appear to us as not being at the bottom. This is what makes the tale so difficult, but also so charming and effective: the double negation prevents it from being locked into an interpretation. There is no moral, no message in the tale, which would be conveyed by an image, a discourse, the testimony of a reality, or more exactly there is one only through the double denial.

.The game of double denial organizes, from the three planes of the tale's device, the relationship to reality, according to a polarization between the word and the event. Both the word and the event are composite formations: the event in the tale is never a purely real event, there is always something of the façade and something of the background; the word, which structures and marks out the narrative, is at once a piece of nonsense, whose absurdity it can concentrate, and a witticism, which tears through the façade to reveal, in a burst of light, the background.

I. Facticity of the storytelling event

The event as a device for hosting the event

Griffon on the cart of infamy (Roland furieux, Brunet 1776, ch17) - Moreau

In Zadig in particular, Voltaire delights in derealizing the event to the point of absurdity, to the point of making it an element of comedy. In the chapter " Les Généreux ", he imagines a great public ceremony in Babylon, where the most generous action is rewarded. The first satrap reports to the king, seated on a throne amidst representatives of the nobility (the Great Ones), the clergy (the Magi) and the provinces (the deputies of all the nations), the most generous actions, between which it is a question of choosing the one to be awarded.

The competition imagined here seems to take as its model the medieval-inspired tournaments that populate marvelous tales, and whose prize is usually the love of a queen or the hand of a princess. Voltaire stages such a tournament in chapter XVI "Les combats ", which is itself a rewriting of the Damascus tournament where Griffon is deceived by Martan, in Canto XVII of Ariosto's Roland furieux. The quest for love is a common thread running through the plot of Zadig : Semire has left Zadig for Orcan, Zadig has repudiated Azora, the queen testifies to her " complaisance " for the king's new favorite ; on the model of Lancelot or Tristan, Zadig enters the triangle of courtly love service, where the contest puts him to the test before the eyes but unbeknownst to the king, to prove himself to the queen.

But is the Tournament of Love really what Voltaire wants to tell us here ? In truth, Voltaire only realized this expectation of fiction at a late stage. In the first version of the tale (Memnon, 1747), the last two sentences of the /// previous chapter, which evoke Astarté's budding feelings for Zadig, did not exist. From these feelings, Zadig, unaware of the danger, concludes that happiness is possible : with this 1748 addition, Voltaire establishes a leitmotif of the pursuit of happiness that did not exist in the original version :

" qu'il est difficile d'être heureux dans cette vie ! " (end of chapter " Le chien et le cheval ", p. 34, this ending constitutes a hapax in 1747)

" Zadig began to believe that it is not difficult to be happy " (end of " L'envieux ", p. 38, addition of 1748)

" Zadig said : So I'm happy at last ! But he was wrong " (end of " Généreux ", p. 40, addition of 1748)

The chapter " Les généreux " is now framed by this assertion of Zadig's happiness, or rather first his double denial (" il n'est pas difficile d'être heureux ") and then his immediately denied assertion (" Je suis donc enfin heureux ! But he was wrong "). The event of the chapter becomes the event of the assumption of this happiness, but an assumption marked by the seal of doubt and precariousness.

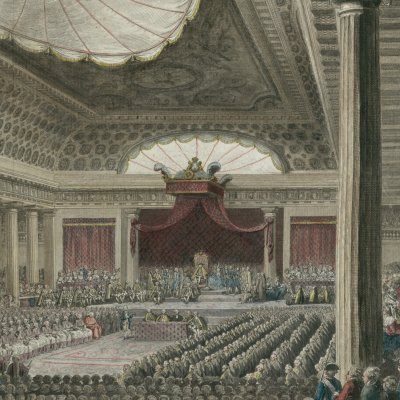

Opening of the Estates General in Versailles on May 5, 1789 - Helman > Ch. Monnet

This late narrative superstructure is grafted, as it were, onto a more original and fundamental event device. First and foremost, the chapter installs a public space of representation, which in the eighteenth century was a utopian space and would only materialize with the convening of the Estates-General. The Enlightenment dreamed of such a space, where the assembled community could exercise its judgment : impossible to implement in the political sphere, such a space for judgment was experimented with in the arts (with the exhibitions of the Royal Academy of Painting at the Salon carré in the Louvre, for example) but also in the moral sphere, with the fêtes des rosières, where particularly virtuous young girls were rewarded and even sometimes endowed2. And indeed, virtue is what we're talking about here : Voltaire speaks of " those games where glory was acquired, not by the lightness of the horses, not by the strength of the body, but by virtue " (p. 39).

The competition is the event of the chapter (" Ce jour mémorable venu... ", p. 39), but the competition device itself comes to host, at a second level of representation, a series of events. In this way, a game of façade and background is set up, a layering of realities: in front of us, the beautiful prize-giving ceremony is an opportunity to report, as constituting its background, a series of generous actions, which themselves have repaired an injustice, a suffering, a loss, thus revealing behind them a background of reality. Finally, we understand in the next chapter that this whole contest will have served as a litmus test for Zadig, before his appointment as prime minister3.

The winner will be declared " he of the citizens who had done the most generous deed ", and the king will reward him with a cup and a wish : " may the Gods give me many subjects who resemble you ". The contest is a citizens' contest, but the king rewards a subject. The contest implements a democratic (almost4) judgment evaluating qualities. /// The judges elect a citizen, but the king finally rewards the exceptional merit of a loyal subject. From one to the other, the vocabulary shift symptomizes a hiatus in values, which will order the narrative : the judges elect a citizen, but the king will ultimately reward in Zadig his best courtier.

The first satrap first presents three candidates : " he presented " the first, " he produced " the second, " he made appear " the third. This is the vocabulary of the show. Nothing says that the floor is given to any of the candidates : while they show themselves, three boniments are recited by the satrap before the judges' rostrum, as would a slave seller at an auction.

.Buying nobility : generosity and courtier strategy

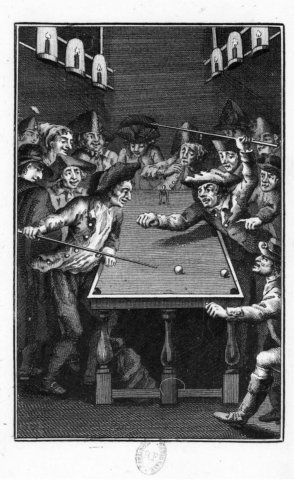

Voltaire didn't invent the three stories : the model for the first is theatrical, it's La Gouvernante de Nivelle de La Chaussée5, whose plot is probably inspired by an anecdote from the beginning of Saint-Simon's Mémoires. The memoirist portrays a certain Chamillart : the man excels at billiards, a passion shared by the king. Louis XIV befriended him, despite his commoner status. Chamillart played regularly with the king, but continued to work as a councillor in the parliament, i.e. as a judge. What had to happen happened: he didn't read the case documents carefully, and delivered an unjust judgment.

" I cannot leave Chamillart without recounting an action of his which, for not being here in its place and having had to be recounted earlier, deserves not to be forgotten. It took place when he was a member of parliament, and he played billiards with the king three times a week without sleeping at Versailles. This broke up his days and hours without distracting him, as I said, from his assiduity at the palace. He reported6 in those days a lawsuit. The man who lost the case came to him, begging for mercy. Chamillart let it out with the gift of tranquility and patience he had. In the complainant's speech, he7 insisted strongly on a piece that made the gain of his trial, and with which he did not yet understand that he had lost it. He rebated8 this piece so much that Chamillart remembered he hadn't seen it, and told him he hadn't produced it. The other to shout louder and that it was9. Chamillart insisted and so did the other, so he took the bags10 that were there, because the stop was just being signed ; they visited them, and the piece was produced there. Here was the man in despair, and yet Chamillart reading the piece and begging him to give him a little patience. When he had read and reread it, Chamillart said to him: "You're right, it was unknown to me, and I don't understand how it escaped me: it decides in your favor. You asked for twenty thousand livres, you've been turned down because of me, it's up to me to pay it to you.

Come back the day after tomorrow. " The man was so surprised that he had to repeat what he had just heard ; he came back the day after tomorrow. Chamillart, however, had made change for everything he had11, and borrowed the rest. He counted out the twenty thousand pounds, asked for the secret and dismissed him; but he understood from this adventure that examinations and trial reports could not compare with this thrice-weekly billiard. He was no less assiduous at the palace, nor attentive to good judgment, but he no longer wished to be /// rapporteur of any case, and handed over those he was in charge of to the clerk's office, and asked the president to commit him to them. This is called a fine, prompt and great action in a judge, and even more so in a judge as closely involved in his cases as he was then12. "

Le vice au billard (Rétif, Nuits de Paris, 1788, t. V) - Sergent

Saint-Simon tells this story on the occasion of Chamillart's elevation to the position of Controller General of Finances in 1689. Saint-Simon is extremely complimentary of Chamillart, and he tells this story in a tone of edification. But the fact remains: it's the story of a parvenu. Chamillart rose to the highest positions in the kingdom because he was a good billiard player, and he neglected his work to share in the king's pleasures. With his consummate talent for persiflage, Saint-Simon feigns the generous action of a judge of irreproachable probity, but at the same time suggests an entirely different background. Chamillart couldn't do his job as a judicial investigator in Paris and spend his time playing billiards in Versailles at the same time. By making amends, he bought himself nobility and found an excuse to stop investigating: he did ask the plaintiff to keep quiet about his action, but it had to be known, and Saint-Simon knew it well. Chamillart was able to turn a blatant malpractice in his favor13.

Chamillart is a judge just as Zadig is appointed supreme judge in the first version of the tale. At the moment when Zadig is about to be distinguished by the king, the story that comes to Voltaire is that of a clever courtier who uses it with the king exactly as Zadig did : generosity is the shrewdest strategy to achieve, to distinguish oneself from other courtiers, who calculate their actions down to the last detail. In chapter " Le chien et le cheval ", Zadig willingly pays the Desterham the fine, then the court costs, then the second fine imposed on him (p. 32, 33, 34) better still, in the following chapter, he returns all his possessions to the envious man who had him condemned to death (p. 38). In a way, this generosity outbids Chamillart's, but proceeds from the same movement: it buys Zadig a nobility he has not inherited. Zadig was in fact " born with a beautiful nature fortified by education " (p. 25) : in other words, he had no name. Memnon was of the same name, in other words, everyone's name. Zadig was rich, but not " nephew of a minister " like his first rival Orcan (p. 26).

Background wedding and frontage wedding

The second story also comes from a comedy, L'Époux par supercherie by Louis de Boissy14, whose subject is taken from Boccaccio : it's the story of Titus and Gisippe15. Titus, the son of a wealthy Roman noble family, leaves to study in Athens. There he befriends Gisippus, another student. Gisippe's family are preparing his marriage to a beautiful young girl, Sophronia, with whom Titus falls madly in love. Caught between the duties of friendship and the heat of the /// passion, Titus withers away. Gisippe finally confesses his secret and promises him the girl. Preparations for the wedding are too far advanced to break it off without scandal: Gisippe formally marries Sophronie, but at night it is Titus who, under the cover of darkness, shares the bed of the new bride. The death of Titus' father calls him back to Rome, and he doesn't want to leave without his wife: he reveals the subterfuge to the family, who, faced with a fait accompli, are forced to acknowledge the marriage. Boccaccio's story has a second part: a few years later, a ruined Gisippus arrives in Rome. He finds his way to Titus, who doesn't recognize him in the crowd. In despair, Gisippus accuses himself of a crime he didn't commit, and is condemned to be crucified. Titus learns of this and accuses himself in his place. The real criminal then appears before the court to exonerate the two friends. Augustus is moved by their generosity and pardons the three of them. Titus then shares his fortune with Gisippus and gives him his sister in marriage.

This story can be compared to chapter II, " Le nez ", where Zadig gives his wife Azora to Cador, not out of generosity, but on the contrary to lose her : here again, the generous action, the reported event, somehow repeats in distorted form an episode from the main narrative. But there's more. In Boccaccio's version, Titus is the nobler and wealthier of the two friends: he comes from a noble Roman family, whereas Gisippus, an Athenian, belongs to a defeated city, is less wealthy than he is and can't boast of having statues of his ancestors in the city streets. Titus insists heavily on this point in the speech he makes to his wife's family to get them to recognize his marriage in place of Gisippe's16. Gisippus' generosity, like Chamillart's, precedes his social elevation: by giving him his sister as a wife, Titus finally elevates him to the rank of Roman citizen and, by sharing his fortune, equalizes their respective wealth. As in Chamillart's story, Gisippe's generosity is neither calculated nor self-interested, but has a higher purpose, illustrating, redoubling and reinforcing Zadig's courting strategy, which, although it presents itself as non-strategy, as a refusal or disdain for any form of strategy, in a way objectifies itself as strategy through the serialization of events17.

Finally, the story of this double marriage is remarkable for the façade game it sets up in Boccaccio : a first marriage, that of Gisippe, serves as a façade for the real but hidden marriage, relegated to the mystery of the alcove, which is that of Titus. Sophronia herself is supposed to be the dupe of both her husbands. But this provision, which met with the device of the Voltairian tale, is all but erased in the summary given by the first satrap of the second action. Above all, the reciprocity in generosity, reflected in Titus's outbidding of the gesture, disappears here, or more precisely is diluted in the contest, which converts it into a new system of retribution.

Slide into the absurd

For the third action, Voltaire evokes the Hyrcanian War, which in Tacitus refers to the revolt of an eastern province of the Parthian kingdom under Vologesis, at the time of Nero and Corbulon's Roman conquest of Armenia18. Hyrcania had entered the Latin vocabulary through Dido's imprecations in Canto IV of the Aeneid19 and from there to Seneca's tragedies20. Lucan also mentions Hyrcania, which he always associates with barbarian atrocity21. Lucan, Seneca and Tacitus are contemporaries, it's the same world : the imaginary of Hyrcania is then transposed into the Senecan tragedy of the Renaissance22 and the Baroque age23. From there, he wins the novel24.

Le dictionnaire de Trévoux cites in the article Hircanie two verses from the Pharsale in Brébeuf's translation25 :

He puts under his flags, with Scythia,

The savages of Bactria and those of Hircania

Astarté will recount another Hyrcanian war, at the end of which " Moabdar died pierced with blows " (p. 77).

Montesquieu wrote, at the same time as Voltaire his Zadig, an " oriental history ", Arsace and Isménie, which he set during a Hircanian war : Arsace is a soldier and his mistress, Isménie, dies, or rather feigns death, while he is fighting. But Montesquieu's novel, if written before Zadig, could not have influenced it, as it was not published, by Montesquieu's son, until 1783 in his Œuvres posthumes26. The name Astarté may, however, have been borrowed from Montesquieu, who features a Guebre Astarté, i.e. a Zoroastrian like the Hyrcanians, in one of the Lettres persanes27.

War in Hyrcania seems to mean essentially civil war, where all atrocities are permitted. And indeed, the soldier's generous action is not set against the backdrop of war in the heroic sense, as might be expected in the context, but a massacre in which soldiers and civilians are mixed together, and women first and foremost targeted. In the midst of the massacre, the soldier must choose between defending his mistress and his mother. He abandons his mistress for his mother, then wants to kill himself, but renounces suicide at the prayer of his mother, who has only him to provide for her.

.It's a bedtime story, in the style of Arsace et Isménie and more generally the rococo novel that Voltaire parodies here : by dint of overdoing generosity, the height of heroism falls back into the flattest triviality. The soldier sets out to save his mistress from her kidnappers, but he gives up to save his mother, but he gives up to commit suicide, but he gives up because " she had only him to help " : in other words, she'll need him on a daily basis, to do the shopping, lend an arm and a bit of conversation... The sublime of generosity is overtaken by the reality principle, the economic background that underpins it : you have to live, eat, be protected.

The story is abracadabra because it concentrates too many adventures, too many levels in the sacrifice : the sinuosity of the narrative turns to twaddle. In the Dictionnaire philosophique, Voltaire characterized this overkill with a scathing line : " On nous berne de martyrs à faire pouffer de rire28. " Paradoxically, the series of disengagements from verisimilitude is brutally brought down to the simplest reality laughing at the tale of a martyrdom a little too extravagant looking after the old mother after having played out the epic of the Hyrcanian wars and the tragedy of suicide for love one after the other.

The word versus the event

There's a gradation in these generous actions, a one-upmanship : the first gives all his good, the second gives /// his mistress and again pays the dowry, the third sacrifices his mistress, saves his mother and again makes the gift of his death, renounces heroic suicide. Each new action takes up a motif from the previous one : the first gives away all his property and likewise the second pays the dowry ; the second's friend was close to expiring from love and likewise the third renounces killing himself for love. The surfeit of generous actions, whose motives intertwine, leads to a brutal catch-up with reality, to comic effect " he had the courage to suffer life ".

On the level of action, the logic of one-upmanship leads the judges to opt for the third candidate, whose generosity consisted in not being heroic, letting his mistress be kidnapped and raped by Hyrcanian barbarians, then forgoing the sublime death of the tragic scene. Generous action is not heroic action generosity defeats the event : the judge's judgment was a bad judgment, which had to be plastered over the friend's marriage was not the right marriage, which had to be cobbled together the lover's suicide, which was the tragic and noble event, didn't happen. Generosity is bourgeois, it undoes the event and organizes comfortable lives. It's a whole negative dialectic at work in the text, methodically deconstructing the very device of the contest it purported to install.

.King Moabdar's refusal to follow the judges is therefore not, strictly speaking, a surprise, but rather delivers the final blow to the device that has come undone. Precisely, it's not an action, producing an event, that the king intends to reward, but a word, i.e. a priori a non-event. Let's take the terms from the beginning of the chapter : it was about rewarding " the one of the citizens who had done the most generous action " ; the first Satrape " exhibited the most beautiful actions " ; he doesn't mention Zadig's generosity towards the Envious, which was told to us in the previous chapter, because " it was not an action worthy of competing for the prize " ; when the Satrap has finished speaking and the judges have decided on the third candidate, the king acknowledges that " his action and that of the others are beautiful ". The action must make an event, constitute an exemplum virtutis and enter the series of typical examples : " I have seen, in our histories, examples that... " The event is not a manifestation of reality, it's a symbolic construction, a facade for theater. And this event is less and less event, these actions less and less actions.

What has Zadig done that better deserves the reward ? " Il osa dire du bien " de Coreb ; il a " parlé avantageusement d'un ministre disgracié " ; il a " contredit [la] passion " du roi. Zadig's generosity is a heroism of the word that breaks with the sublime nobility of virtuous action. Zadig did nothing, gave nothing, fought nothing, but he had the courage to say. Above all, whereas all his actions were behind-the-scenes, generosity not intended for publication, Zadig's word is a public and, as it were, political statement. Zadig publicly took the side of a minister dismissed by the king : he defended this minister's action, his decisions, his policy.

Zadig's choice thus goes in the same direction as the contest device, which it nevertheless seems to contradict by reaffirming the absolute precedence of the king : it repoliticizes the space of fiction, substituting novelistic brilliance for the event and staging the political courage to assert a singular position, in other words, a difference in a public space. In this sense, Zadig's word is an action that surpasses all others: while virtuous generosity is a moral matter, the /// The courtier's generosity (and here we must understand the courtier in the noble sense of Baldassare Castiglione) restores a political word. The event is moral when the word is political. The depreciation of the event is precipitated and at the same time made up for by the word, which performatively transforms the depreciated space in which it comes to be inscribed into a political one.

Politics of the event

Does this mean that Voltaire, as narrator, fully endorses Moabdar's decision and the chapter's conclusion ? It's doubtful. The distance is clearly marked by this sentence, which foreshadows the catastrophes to come : " The king acquired the reputation of a good prince, which he did not keep for long. " (p. 40) He did not show himself to be a good prince, but acquired, temporarily, the reputation of a good prince : in other words, the king performed an excellent political communication operation, which has nothing to do with either a morally just decision, or an act of good government.

The operation is twofold facing Zadig, who had challenged Coreb's disgrace, Moabdar by making an assault of generosity regains the advantage facing the judges of the contest, whose assembly potentially constitutes a rival power, the king vividly reaffirms his sovereign power. But this comes at a cost: Zadig can now only become a minister, and the judgment of the assembled states must still be recognized. Voltaire makes a clear distinction between the rewards of the three popular candidates and those of Zadig. To the former - twenty thousand gold coins each and entry in the livre des généreux, i.e. what is legally recorded in the deeds of the kingdom, the substantive benefit; to Zadig - the cup and only the cup, i.e. the spectacle of the event, the full glare of the limelight, the front benefit. That this is only a facade is pointed out by the 1748 addition that closes the chapter : " Zadig said : "Je suis donc enfin heureux !" But he was wrong. "

The " Generous " chapter thus reveals many surprises : it is indeed organized according to a polarity of word and event, opposing Zadig's word, and Moabdar's word on that word, to the event of generous actions, and to the event of welcoming those actions into the contest. The word contradicts the event, reversing its course, deconstructing its spring of judgment. But in this interplay of word and event, the positions taken are not those we might have expected: the event does not occupy the position of the real; it unfolds a series of theatrical or novelistic scenes, articulated in an increasingly complicated rococo narrative that de-realizes its effect. Conversely, the word does not occupy the position of vain discourse, of nonsense it installs a political word that challenges the very device of the contest and what the chapter aims through it. The word then becomes the event, it makes a political event and introduces the real through the disturbance of the contest.

The word enters the courtier game and thereby participates in the façade of his servile sycophancy. Voltaire maliciously indulges in it. When the king grants him the cup for his word, Zadig outbids him with a courtly compliment: " it is Your Majesty alone who deserves the cup, it is she who has done the most unheard-of deed, since, being you, you did not get angry with your slave, when he contradicted your passion " (p. 40). Basically, the most generous action, the only one worthy of the cup, is... the action of awarding the cup !

But precisely because it brutally illuminates with its brilliance the facade of fiction where it originates, the word tends towards its reverse. There is a tendency for the word not to speak the truth (the game of facade forbids this), but to point to the real. Zadig's word highlighted the king's passion (" when he contradicted your passion "), /// in other words, a decision motivated by facade rather than political reason, an epidermal reaction rather than an act of government. The word returns to reality through the political game it introduces. The word establishes a politics of the event.

II. Word and metalepsis

This distribution of the word, which arises from the façade of the tale to point to its background and revitalize a logic of the event, reveals a very profound mutation in the status of classical fiction : its economy of plausible coherence vacillates, exhausting itself in fadaise, in favor of a play of background and façade operated by the word. The word distributes itself between façade and background, while at the same time deploying itself as fadaise. Through this distribution, it organizes fiction according to the figure of metalepsis.

Gérard Genette has proposed extending the rhetorical notion of metalepsis to what he calls fictional metalepsis, which he believes would define the very workings of fiction :

" A fiction is, in short, merely a figure taken literally and treated as an actual event, as when Gargantua sharpens his teeth from a hoof or combs himself from a goblet29, or when Mme Verdurin unhinges her jaw for laughing too hard at a joke30, or when [...] Harpo Marx [...] is asked if he's holding the wall he's leaning against, and he steps away from the wall, which immediately collapses31 : holding the wall is a common figure, which this gag, by literalizing it, converts into what we call fiction32. "

The basis of metalepsis is to superimpose, to amalgamate the level of reality and the level of representation. Genette dwells at length, drawing on Fontanier, on examples of writers unfolding their fiction as if it were playing out under their window (the beginning of Noé, by Giono), or pretending to command, to trigger the events they imagine or report (Virgil making Dido die, Voltaire ordering the actors of Fontenoi to begin the battle). What's at stake here is the transition from figure to fiction, i.e. from the punctual play on the signifier, frozen in an expression or a word, to the organization of a narrative as a whole, where the frozen expression comes to life, unfolding as an event. In this shift from the form of a word to the organization of an entire narrative lies the secret from which fiction is ordered. There are doubts about the permanence and universality of such a formal mechanism. But it is certain that the Voltairean word plays on it, precisely to organize the installation of reality in fiction, whereas fiction was not at all intended to accommodate it.

.Trovander : word distribution and narrative program

In L'Ingénu, at the first supper at Kerkabon priory, l'Ingénu is asked about his language :

" Then it was who would ask the Ingénu how one said tobacco in Huron, and he replied taya ; how one said to eat, and he replied essenten. Mademoiselle de Kerkabon absolutely wanted to know how one said to make love he answered trovander and maintained, not without appearance of reason, that these words were well worth all the French and English words that corresponded to them. Trovander seemed very pretty to all the guests. " (p. 46-47)

Voltaire adds to this passage a note : " All these words are indeed Huron. " He draws the reader's attention to the reality of the signifiers, which the conventions of fiction here quite permitted him to invent33. /// He insists on this reality by giving his sources M. de Kerkabon fetches from his library " the Huron grammar which the Reverend Father Sagar Théodat, récollet, famous missionary, had given him ". This book actually exists, and Voltaire owned it : it is the Grand voyage du pays des Hurons, situé en Amérique vers la mer douce, es derniers confins de la nouvelle France, dite Canada, [...] with a dictionary of the Huron language for the convenience of those who have to travel in the country, & n'ont l'intelligence d'icelle langue, par F[rère] Gabriel Sagard Théodat, récollet de Saint François, de la province de S[aint] Denys en France, publié à Paris, chez Denys Moreau, en 163234.

Voltaire here superimposes his search for Huron names in Sagard's dictionary, which he carried out to write the episode, onto Kerkabon's verification of these names, which necessarily comes into the fiction after they've been said. This is a first metalepsis. But, as Richard Francis points out, this scene is totally implausible: Sagard's dictionary is organized more like a conversation manual than a dictionary. It doesn't present itself as a list of words, but as a list of subjects or themes, for which Sagard provides complete sentences. Thus, in the article Pétuner, an old French word for smoking tobacco, we read, " Donne-moy à petuner, Etaya " ; in the article Manger, " Donne-moi à manger, Taetsentĕ, Sattaésenten " ; in the article Mariage, " Vas-tu point faire l'amour ? Techtrouandet ". The words that Voltaire extracted and, in his mind, polished, are indeed found, with a few deformations, but it would have been impossible for the prior to find these words quickly and easily in the dictionary.

Of the three words the Ingénu gives, it's the third that causes a sensation in the small society of lower Brittany. Mademoiselle de Kerkabon asked for " faire l'amour ", which in the classical language has no sexual meaning :

" Faire l'amour, c'est tâcher de plaire à quelque Dame & de s'en faire aimer. More ordinarily, faire l'amour to a girl or woman is to seek her in marriage. Faire amitiez is to caress someone to engage them to love us. Faire les doux yeux, c'est regarder amoureusement une femme. " (Dictionnaire de Trévoux, art. Faire, p. 644)

Of course, we have to understand the old lady's falsely naive request as an indirect proposal to L'Ingénu to court her, as an awkwardly gallant invitation. But Sagard's dictionary invites us to clarify the meaning Voltaire had in mind, who looked here for the article Mariage, and came across " Vas-tu point faire l'amour ? ", i.e. vas-tu point me demander en mariage. Voltaire arbitrarily cut a tech for " vas-tu point ", and reinstated an infinitive -er, which gives him trovander. The word trovander contains both the gallant proposal and the formal marriage proposal, Mlle de Kerkabon asks the Ingénu to seek to please, to be loved ; she asks him to seek to marry her. She asks him to desire, to seek, and he responds trovander, which, jokingly, makes a different sense in French : qui me cherche me trouve, to the prompt l'Ingénu has something to answer.

The word here contains, as it were, from the outset the program of the fiction : it will indeed be a question for the Ingénu of making love, but in the non-coincidence of seeking and finding : not Mlle de Kerkabon, but Mlle de Saint-Yves, not by throwing himself on her bed (chap. 6) but by deserving her through war (chap. 7) ; and for Mlle de Saint-Yves not by seducing l'Ingénu, but by giving herself to M. de Saint-Pouange (chap. 17). The word trovander programs the event /// of chapter 6, and from there the series of events in the tale.

Thanks to the Saint-Pétersbourg sketch found by René Pomeau, we know that in the original draft l'Ingénu married :

" Histoire de l'ingénu, élevé chez les sauvages puis chez les anglais, instruit dans le rellig en basse bretagne tonsuré, confessé, se battre avec son confesseur Son voyage a versailles chez frere letellier35 son parent | volontaire deux campagnes sa force incroiable son courage veut etre cap de cav etonné du refus. Gets married, doesn't want the m to be a sacremt, finds it very good that his wife is unfaithful because he was her. Dies defending his country, an English captain lassiste ala mort with a Jesuit and a Jansenist, he instructs them as he dies36. "

L'Ingénu marries, but doesn't want marriage to be a sacrament and finds it very good that his wife is unfaithful because he has been. L'Ingénu's marriage is, in his mind, a Huron marriage, that is, according to Voltaire, a marriage according to natural law but L'Ingénu, in this sketch, marries in Versailles, that is, in the quintessential place of French civilization, according to the civil and religious laws and institutions of a French marriage. To the request made to l'Ingénu, to " faire l'amour " (the request formulated by Mlle de Kerkabon), l'Ingénu responds, as requested, with a trovander huron, a techtrovandet, a voulez-tu me faire l'amour huron.

The word is thus distributed into a facade, " faire l'amour ", where it originates, a first background, trovander, where it reverberates as a response, and a background, techtrovandet, where Voltaire tells us he went looking. This distribution is not only one of meaning, between the French marriage and the Huron marriage, between the convention of gallant play and the crude proposition, it is also one of person : the old damsel's request, translated by the Ingénu, becomes the Huron's request it passes to the other side of the interlocution, and inverts the subject and object of desire.

Syllepsis, metalepsis and metastasis : chapter 6 of L'Ingénu

Chapter 6 implements the word program from this distribution, which is a layering of meaning. By metalepsis, it literalizes, and thereby fictionalizes, the " faire l'amour " ingenuously launched by Mlle de Kerkabon in chapter I : for the word is ingenuous, at the very principle of the tale's creation, at the principle of L'Ingénu. In the sketch, L'Ingénu was really getting married, and in Versailles in the finished tale, the marriage fails, and fails in lower Brittany. But in the misfire we read of remains the brilliance of the performance, which is the signature of the first intention.

Chapter 6 opens like a crashing entrance: Voltaire writes it as a dramatist. In Mlle de Saint-Yves's bedroom, he recounts the Ingénu's irruption and the clarion glare of a first exchange of words :

" No sooner had the Ingénu arrived, than, having asked an old servant where his mistress's room was, he had pushed the poorly-closed door hard, and dashed to the bed. Mlle de Saint-Yves, awakening with a start, cried out: " What ! it's you ! ah ! it's you ! stop, what are you doing ? " He had replied : " I'm marrying you ", and indeed he was marrying her, if she hadn't fought back with all the honesty of an educated person. " (p. 69)

The first sentence is captured from the Ingénu's point of view, while the second adopts that of Mlle de Saint-Yves. The first sentence describes a journey, an obstacle course that the Ingénu crosses to Mlle de Saint-Yves's bed, and sets up a fast, spirited pace, /// joyeux : the verbs "arrivé" (arrived), "poussé" (pushed) and "élancé" (dashed) mark a progression in movement, embracing the rise of desire, while slowness, sinuosity and impediments are relegated to the embedding of subordinates (" ayant demandé à une vieille servante où était la chambre de sa maîtresse " ( having asked an old maid where her mistress's room was ", a participial to which an indirect interrogative is grafted). The adverb " fortement ", which carries the movement, clashes with the object complement, " la porte mal fermée ", which resists it poorly. The whole mimics a thrust that prepares the reversal of point of view, from the inside, from the bedroom, from Mlle de Saint-Yves in bed. The reversal of point of view precedes the dialogue, setting the scene for interlocution. The Ingénu's journey is answered by Mlle de Saint-Yves's cry, and a first gunshot is answered by a second.

His cry breaks down into four interjections, in which we hear above all the " vous " that accuses the presence of the other, in four different tones. First it's the what of surprise, then the ah of pleasure, then the gallant stop, finally the what are you doing of alarm. There is thus a journey in Mlle de Saint-Yves's speech, which follows the progression of the " faire l'amour " whose program the chapter implements. This discursive, symbolic path responds to the geometrical path of l'Ingénu : it comments on it, it relays it, it pursues it.

It's a path of speech, but it's at the same time a word, it's the word " vous ", which functions here as a metastasis of the word-program that orders the chapter. In Chapter I, we noted that this word, trovander, had already appeared in an interlocution. Mlle de Kerkabon asked l'Ingénu (de lui) " faire l'amour ", and he replied what the guests hear and the narrator transcribes as trovander, for Techtrouandet, " vas-tu bien faire l'amour ", which reverses the point of view and flips the origin of the request and desire. The reversal of point of view at the beginning of chapter 6 merely echoes this initial reversal: it literalizes it by syllepsis, and transfers the original flaw, which is at the root of the word's distributive power, to Mlle de Saint-Yves's cry, which distributes the " vous " : it's she who cries out, but she cries out vous, it's a vous of surprise, which comes from outside, and it's a vous of pleasure, which she has desired and asked for it's a vous of banter, which she is ready to entertain, and it's a vous of fright, which worries her and which she repels. Vous becomes the starting point of a new word, by metastasis, i.e. by detachment of a first proliferating power of the signifier (trovander) into another signifier that will in turn colonize the fictional program.

" Vous " is fundamentally sylleptic : it changes meaning when it changes interlocutor : " que faites-vous ? " designates the Ingénu, to which responds the Ingénu's " Je vous épouse " where " vous " designates Mlle de Saint-Yves. The " Vous " condenses the two desires, unifying as a single sign of love the two opposing, confronting positions of l'Ingénu and Mlle de Saint-Yves. Syllepsis prepares for metalepsis, installing in the signifier the metastatic power of the word.

" Je vous épouse " is the new word : " Je vous épouse et en effet il l'épousait " in effect distributes meaning between the plane of the facade, the gallant " faire l'amour " whose speech is not meant to have any effect, and the plane of the background, which is nothing less than an attempted rape. As narratological formalization would tend to reduce it, metalepsis plays not between a conventional reality (the place of the narrator's utterance) and a fictional convention (the place of the utterance), but between facade and background, between the discursive brilliance of the stage and its theatrical apparatus and the /// the brutality of the real, the outpouring of the real outside of all convention.

A night in Casablanca, Harpo Holding Up The Building Gag, Marx Brothers, 1935. Click on the video to start it

It's impossible to combine in a performance a shot of reality, which by its very nature is defined as outside representation, with a shot of facade, which exacerbates to the point of caricature the artifices of representation. Metalepsis is an impossible figure it therefore always operates at the limit of the figurable for this reason, it plays with the absurd, and constitutes an ideal terrain for the deployment of meaning in the nonsense of the mind. Gérard Genette cites a particularly spectacular example: in the souk of Casablanca, Harpo Marx is leaning against the wall of a stall, doing nothing but loitering. A policeman calls out to him, asking "What are you doing there doing nothing ? My word, are you holding up the wall? Harpo, still mute, nods and laughs. The gendarme pulls Harpo towards him, and the wall collapses.

The wall is a facade. It only holds as long as the façade of the witticism lasts. The wall is there, visible, consistent, only because of the expression " tenir le mur ", to do nothing. The word consists in reversing the expression, in pointing it out as a pure façade, in bringing down the wall. At the end of the word, the facade comes down, revealing the other side of the coin: that there's nothing to be done, that Harpo, the white clown, has nothing to do there, that this wall, like the whole of the society it denotes, is nothing but a facade. The absurd is not a purely gratuitous game that can be dismantled like a rhetorical device: the absurd shows us the reality that representation should never show us. That's why it can only show it fleetingly, indirectly in the Marx Brothers sketch, there seems to be nothing behind the wall, no inhabitants or merchants behind the stall and storefront, while the souk street teems with people the three Marcocans who emerge from the left at the end of the sketch to witness the collapse, emerge from nowhere, and certainly not from within. What's holding Harpo together? France's fragile protectorate in Morocco and the colonial economy that keeps it going as a facade after Abdelkrim's revolt? Or, metaphorically, Roosevelt's New Deal, held together by the hand of an unemployed Jew amidst busy Arabs? The gag isn't purely a gratuitous game of ornamental metalepsis; it tells of the idle, migrating presence of a " holding the wall " that threatens an economic and political order close to collapse : however much attenuated, relegated to the background of the joke's nonsense, this background constitutes the word's tendency and feeds the metalepsis's reality.

Voltaire gives himself to be read in this same sharing of the gratuity, the lightness of the word, and the background, the tendency that feeds the word. Voltaire does not have the means of the image, which shows the collapse of the wall, and thus visually operates the metalepse. The word thus distributes itself from the facticity of discourse (the fadaise), which it perforates. To do this, the narrator inverts the respective positions of discourse and reality. L'Ingénu seizes the discourse, supposedly deploying the gallant game of " faire l'amour ", while Mlle de Saint-Yves is cornered in reality to struggle " with all the honesty of a person who has education ". Of course, this honesty is comical, when it involves a frail young girl grabbing, pulling and pushing back a colossus, a force of nature, a Hercules ! One doesn't struggle with honesty, the manner complement can't complete this verb : to struggle is the real thing, and the real thing doesn't have the manners of the facade.

Here, then, is Mlle de Saint-Yves in the savagery of the real, and l'Ingénu in the delicacy of the real. /// speech:

" L'Ingénu didn't hear mockery ; he found all these ways extremely impertinent. This was not the way Miss Abacaba, my first mistress you have no probity you promised me marriage, and you don't want to marry this is breaking the first laws of honor I'll teach you to keep your word, and I'll put you back on the path of virtue. " (p. 69)

L'Ingénu speaks and Mlle de Saint-Yves struggles l'Ingénu reminds Mlle de Saint-Yves of her duties, of her virtue, and Mlle de Saint-Yves tries not to be violated. The comedy of the situation lies in this absurd reversal between the discourse of the text we're reading, and the situation set up in the previous paragraph. The metalepsis superimposes the real beginning of a rape on its paradoxical representation as a discourse intimating virtue: it's no longer just " I marry you " that makes metalepsis, but " you promised me marriage ", " make marriage " to make love, and above all " I'll put you back on the path of virtue ", where the path becomes literalized in the most scabrous way.

The Ingénu's speech is, in a way, pure fadaise that allows the metastatic deployment of the word. Fadaise distributes the word into a facade of virtue and a gravelly background, in a duplicity that libertine literature has abundantly exploited. But the originality here lies in the fact that the author of the word is ingenuous, and that this factitious honor, this factitious virtue that he claims at the moment of committing a rape are at the same time the authentic honor and the authentic virtue of a good savage who, really, speaks in good faith.

This is the tour de force of the metalepse : it doesn't simply accuse discourse as factitious, misleading or vain through the play of the mind, it introjects the real into discourse, and in so doing brings speech back to a discourse of truth. Fadaise contains the principle of its reversal. It is not a pure façade: it is born from the façade to point towards the real. L'Ingénu " did not hear mockery " : he does not hold the discourse of virtue as a libertine would hold it, by bravado, by antiphrase. He means what he says, and yet there is antiphrasis. L'Ingénu says the phrase and realizes the antiphrase, he literalizes what he says through his attempted rape while he gives real, sincere and authentically remotivated meaning to the speech he holds.

From his point of view, Mlle de Saint-Yves's ways are " impertinent ", that is, literally, unsuited to the context : she doesn't have to struggle because it was she who in chapter 4, the baptism chapter, asked the Ingénu " Will you do nothing for me ? " (p. 63), which the Ingénu has interpreted as Techtrouandet, " vas-tu bien faire l'amour ", in other words promise of marriage, which he again interprets literally, as a promise to consummate it. It is impertinent, unseemly for Mlle de Saint-Yves not to accept what the Ingénu considers, by double literalization, that she has asked for.

So there's a front and a back to the façade : the situation, the event, make l'Ingénu seem impertinent, but l'Ingénu's discourse on the contrary designates Mlle de Saint-Yves as the impertinent one, from the point of view of nature, natural law, Huron common sense. Impertinence is the crack in the facade, which can be seen from either side of the wall of incomprehension. Fadaise unfolds on this fault line.

Honor, the respect for one's word that underpins it, the path of virtue that this code of honor outlines, are the authentic values of the Huron, who in no way cheats by claiming them. The root of the disagreement lies in the very word that has been given, in the meaning of the word, which is distributed by metalepsis between the gallant invitation and the crude request.

The third paragraph closes the sequence with a new reversal of point of view, symmetrical to the one that had opened the chapter :

" L'Ingénu possessed a male and intrepid virtue, worthy of his patron Hercules, whose name he had been given at his baptism ; he was about to exercise it to the full, when at the shrill cries of the more discreetly virtuous damsel rushed the wise abbé de Saint-Yves, with his governess, a devout old servant, and a parish priest. The sight moderated the assailant's courage. My dear neighbor," said the abbé, "what are you doing here? - My duty," replied the young man "I'm fulfilling my promises, which are sacred. "

First, we're in the middle of the bed, and it's from this bed that we must imagine the Ingénu turning as he sees the abbé arriving with his servants. " This sight " is the picture the new arrivals form for the Ingénu, who had his back to them a moment earlier. L'Ingénu is surprised, taken by surprise, just as Mlle de Saint-Yves was surprised in the first paragraph. The reversal revives the metalepsis: against the fadaise, which was deployed as rape, the entry of the new protagonists produces a new effect of reality, giving the Ingénu a glimpse of his " impertinence " on the bemused faces of the arrivals.

.The metastasis of the word then leads Voltaire to a veritable verbal fireworks : the Ingénu's virtue is undoubtedly his excellent character as a good savage whom civilization has not perverted, but it is above all very concretely his erect sex37 ! The Ingénu's baptismal name, Hercule, is not simply his name, but the program of his character, and here again a sexual program. As for the exercise of virtue, it designates the very thing that virtue is supposed to avoid.

We wonder then how to understand " the more discreetly virtuous demoiselle ", and what exactly this discretion implies. How can Mlle de Saint-Yves be discreet when she's shouting? How could she struggle honestly ? Voltaire mischievously describes in her the struggle between desire and propriety, that is, no longer the struggle with the Ingénu, but the struggle with herself. She struggles, but she doesn't struggle so much; she cries out, but she suddenly cries less loudly perhaps it's no longer to call for help, but for pleasure. And how are we to understand that the Ingénu was going to exercise his virtue " to the full " ?

Voltaire tells and doesn't tell, always remaining on the verge of telling a penetration, metaphorized, in space, by the irruption of the abbé de Saint-Yves and his people.

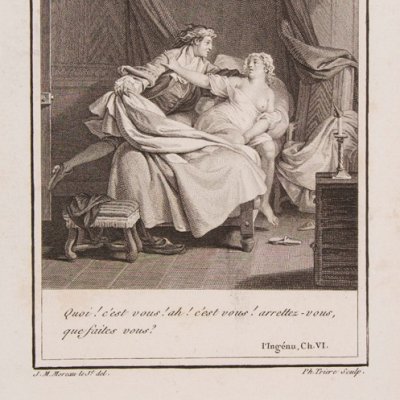

Engraving device

L'Ingénu dans la chambre de Mlle de Saint-Yves - Moreau le Jeune

The penetration is the event. The word says it half-heartedly, the play of trajectories in the text constitutes it as an organizing principle, and the engraving by Moreau le jeune transposes it and stages it. This engraving was apparently not part of the first set of illustrations supplied by Moreau le jeune for the Kehl edition of 1785, which included for L'Ingénu the baptism and the rendezvous at Saint-Pouange's. Was it initially censored as libertine ? If the drawing is indeed dated 1803, it is more likely to be an addition by Moreau for the second edition in which he participated, the Renouard edition (1819-1825). It was perhaps inspired by a spicier engraving by Binet for Rétif de la Bretonne's Le Paysan perverti, depicting the /// rape of Mrs. Parangon by Edmond38.

To the left we can make out the half-open door, the Ingénu is still running, but he's already in bed. His trailing left leg imitates the movement of the race, and maliciously repeats, for the connoisseur, Madame Parangon's spread legs. L'Ingénu opens the sheets with his right hand, while he grabs Mlle de Saint-Yves by the neck with his left. The invention of the open sheet allows Moreau to draw in the fold of the sheets the extra movement of L'Ingénu's 2th leg, which in reality is hard to render. The leg backwards and the fold of the sheets forwards create a straddling of the bed, while Mlle de Saint-Yves' bare leg, protruding from the bed on the right, ready to put her foot down next to her slippers to escape, completes the impression of a whirlwind passage from the left to the right of the image, a complete crossing, a... penetration. The bed's curtains are as if carried away by this fury of transport, lifted and moved to the right.

Miss de Saint-Yves's ambivalence is reflected in her clothing and posture : she has her back to the Ingénu, but she turns, or lets herself turn towards him she tightens her shirt between her legs to prevent access, but she exposes her breast and thigh she pushes her hand away from his shoulder, but by this gesture uncovers her throat and offers her face.

Finally, this is an alcove scene, an intimate romp supposedly without witnesses. But everything is open, the door, the bed curtains. The stool on the left, the chest of drawers with its candlestick on the right, positioned as visual clutches in the foreground, take the place of the spectator, and relay into the image the gaze that, by trespassing, we bring to it.

By the very fact of its existence, Moreau le jeune's engraving designates what it represents as an event. Its caption39 emphasizes the word : " Quoi ! c'est vous ! ah ! c'est vous ! arrettez-vous, que faites-vous ? " The you in the text is a word, or a hit, in the image as a scenic event. The word's equivalent in the image is the thing, in this case Mlle de Saint-Yves' slipper, into which she is about to slip her foot. In the circumstances, this slipper is absurd: do you get out of bed to meticulously put on your slipper just as your lover is standing in front of you, pressing you against him, and you are struggling weakly, just enough, between his arms ? Either you go out without a slipper, or you don't go out at all. The slipper makes no sense in this scene.

But visually it fulfills its function wonderfully from the door handle to l'Ingénu, from l'Ingénu to Mlle de Saint-Yves, from her outstretched arm to her dangling bare leg, an arc is drawn of which the slipper is the culmination. The Ingénu's leg entering the bed, which is suggested without being shown, is duplicated by this foot preparing to slip on the slipper. It's a penetration that redoubles itself, and transposes that which is at stake and cannot be shown.

Conclusion

To conclude, I'd like to return to what's at stake in an analysis of Voltaire's tales in terms of word and event. The device of the Voltairean tale establishes separate plans, the division of these plans is a fundamental organizing principle that is repeated from chapter to chapter : we saw in " Les généreux ", how the public space of the contest opposed the secrecy and intimacy of generous actions, generous precisely because renouncing heroic brilliance. In chapter VI of L'Ingénu, it's the discourse of virtue that stands in vivid and simultaneously comic opposition to real action, to the Ingénu's sexual assault. To these two planes is added a third term, or effect, which is the extenuation of the discourse, or narrative, to the point of /// the absurd : generous actions end up being so complicated that there is no more action ; and virtuous discourse, from misappropriation to misappropriation of the meaning of the terms it manipulates, ends up meaningless.

The word is what holds these three irreconcilable planes together. It glides along the discourse and distributes itself by metalepsis from the façade, where it originates, to the background, where a reverse side of the scenery and, sometimes, the brilliance of reality are revealed. The word is metastatic : the trovander of chapter I commands chapter VI, where Mlle de Saint-Yves's " vous ", which is both the vous of the gallant discourse and the vous of the frightened face-to-face, relaunches the metalepsis, which Voltaire reformulates with " je vous épouse ".

Zadig's " mot ", as evoked in " Les généreux ", is not a bon mot, a witticism. The exact wording is not given. Simply, after Coreb's disgrace, Zadig said his piece, he felt he had a word to say. This word is rewarded as a generous action, and even as the height of generosity, i.e., the word of speech is converted into action, the plane of representation, of courtier speech, of facade and etiquette, is brought down to the plane of action, of political courage and commitment in the real world. While there is no word in the rhetorical sense of the term, the effect is one of metalepsis, which distributes Zadig's word from the façade to the background, to the point of exhausting it in fadaise: Zadig doesn't just say his word, he outbids the reward with a compliment of low sycophancy. This is the price he has to pay to get to the crux of the matter.

Notes

The same term fadaise refers to the absurdities of theological discourse, or apologetics, which feeds religious fanaticism. Thus, at the end of chapter X of Examen important de Milord Bolingbroke, written we are told by Voltaire about the end of 1736 but published in 1767, we read :" Ainsi s'établissent les opinions, les croyances, les sectes. But how did these détestables fadaises become accredited ? How did they overthrow the other fadias of the Greeks and Romans, and finally the empire itself ? How did they cause so many evils, so many civil wars, light so many pyres, and spill so much blood ? "

, Paris, Prault, 1744. Titus becomes " Le Marquis d'Orville, secret mari d'Emilie ", while Gisippe takes the name " Milord Belfort, cru Mari d'Emilie ".

, " tu suças le lait des tigresses d'Hyrcanie " (Énéide, IV, 365).

Or : " Nourriçon d'Hyrcanie, infame sans pitié, | De tes hostes bourreau sous ombre d'amitié " (La Troade, 1579, act IV)

In La Mort d'Achille (1607), Pâris before Priam, pointing to the traitor Déiphobe proclaims : " We will go and inhabit the deserts of Hyrcanie, | Found a dwelling in the Caspian antres, | Before we fall captive in his bonds. " (IV, 1)

In Gésippe ou Les Deux Amis (1622), Gésippe implores thieves : " Desistez-vous, enfans, d'une horrible manie | Que n'exercent contr eux les tygres d'Hyrcanie. " (IV, 4. On this tragedy see note 15)

In Georges de Scudéry's La Mort de César (1636), César exclaims : " But when I ruled tigers of Hyrcanie, | Withques the gentleness with which I treated them, | I would disarm them from so much cruelty. " (III, 1)

And in his Cassandre : " I judged that we would go more surely by Hyrcanie, & by the païs of the Messagetes... ". The narrator passes himself off as " Arsace, Bactrian who by his good fortune, had merited the affection of the King of the Scythians " (IVe partie, livre 2, éd. 1666, p. 209).

But doesn't he borrow his narrative from La Calprenède, whose narrator in La Cassandre impersonates Arsace Bactrien. See note 24 above.

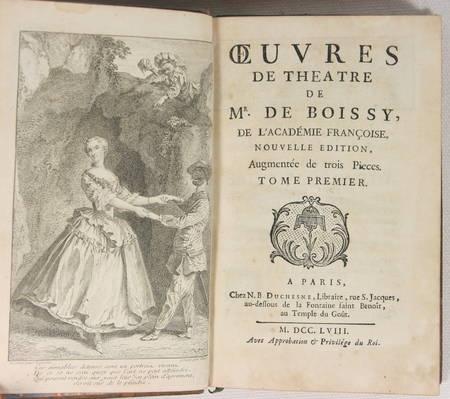

///Voltaire repeatedly uses this term fadaise to refer to his own writings. Regarding the Voyage du baron de Gangan, a lost manuscript said to be the first version of Micromégas, he wrote from Brussels to Frederick II in May 1739 : " I take the liberty of addressing to your royal highness a little relation, not of my voyage, but of that of M. le baron de Gangan. It is a philosophical fadaise which should only be read as one relieves oneself from serious work with Harlequin's antics. " (May or June 15 ?) And in a letter to Laus de Boissy, editor of the Secrétaire du Parnasse who had attributed to him an " Epître à mademoiselle Ch... ", he denies as usual being the author, finally conceding : " Messieurs Cramer [= his Genevan publishers] have done me a very bad service by publishing les fadaises dans ce goût qui sont souvent échappées moi. " (December 7, 1770)

See Favart's opera-ballet, La Rosière de Salency, first performed in Fontainebleau on October 25, 1769. While these fêtes des rosières date back to the Middle Ages, the fashion for them developed at this time, from the late 1760s, i.e. well after Zadig.

In the first version, Zadig was not appointed (first) minister, but supreme judge : the fundamental device is one of judgment. Zadig was judged in the previous chapter, and here he takes part in the judgment, becoming a judge afterwards. By making him a minister, Voltaire lifts the barrier of political prohibition and turns the contest into a directly political issue : it's the head of the government who is to be elected...

" People came from the ends of the earth " for this contest, and the king was there " envied by the deputies of all nations ", but only " the Great Ones and the Magi were the judges ". The principle is that of election " On allait aux voix ", but it is the king alone who makes the decision : " le roi prononçait le jugement " (p. 38-39). In fact, the king's judgment will not correspond to the election of judges.

Haydn T. Mason, in his edition of Zadig for the Voltaire Foundation, cites the review of La Gouvernante in the Mercure de France of February 1747, where we find the very structure of Voltaire's sentence : " This magistrate has caused twelve years ago a just trial to be lost which has ruined an illustrious family, by the negligence he has had to allow himself to be deceived by his secretary the crime of this traitor being known, he wishes to repair it by restoring the value of the loss he has caused. " (Voltaire, Œuvres de 1746-1748 (II), Les Œuvres completes de Voltaire, t. 30b, Oxford, Voltaire Foundation, 2004, p. 138-139.) See in La Gouvernante, Act IV, Scene 5, where the President reveals to his son Sainville that he has sold their land to make up for an error in one of his judgments, and offers him a rich marriage as reparation... which is not at all to his taste !

Chamillart was the rapporteur for a case : it was he who heard it.

He : the latter, the complainer.

Il rebattit tant cette pièce : he rebattit lui tellement les oreilles de cette pièce. Similarly, in La Gouvernante, the President misled by an artificious lawyer failed to take into account a " titre " of property, and thus wronged the plaintiff. Nivelle de La Chaussée puts the blame on this lawyer and mitigates the judge's fault.

that it was : that it was produced, that it was among the exhibits in the file.

The exhibits for each case were placed in a bag at the end of the trial, and the bags were then transferred to the archives. But in this case, the judge's decision has just been made, and he still has the bag in his office.

Chamillart had sold everything he had to raise the necessary sum.

Mémoires duc de Saint-Simon, ed. Adolphe Chéruel, Hachette, 1856, t. II, p. 315.

In La Gouvernante, the victim, or the victim's unfortunate heiress, is the governess, herself the mother of Angélique, with whom Sainville, the President's son, is in love. Not only does the governess refuse the reparation offered by the President, but Sainville's marriage to his daughter, richly endowed by Baronne who protects her, consolidates and even increases the fortune of the offending judge's family. The President's generosity costs him nothing in the end, and even pays off.

Boccaccio, Decameron, Dixième journée, Huitième nouvelle, ed. Pierre Laurens and Giovanni Clerico, Gallimard, folio, 2006, p. 841sq. This short story by Boccaccio had already given rise to a tragicomedy by Alexandre Hardy, Gésippe ou les deux amis, 1622. Unlike Boissy, Hardy faithfully follows Boccaccio.

Boccaccio, op. cit., p. 850sq.

It is not true that this is not a strategy : it is always the double denial that is at work.

Tacitus, Annals, XIII, 36.

sive Hyrcani celant saltus (" be that the hedgerows of Hyrcania shelter them ", Hippolytus, I, 1) ; an sub æterna nive | Hyrcana tellus (" is it, under eternal snow, the land of Hyrcania ? ", Thyeste, IV, 1).

" Like the tigers, when on the footsteps of their mothers they drank in the forests of Hyrcania the blood /// of slaughtered flocks, never shed their ferocity, so Pompey... " (I, 327-328) ; " The wandering hordes of Scythia dip their arrows in poison, as do the inhabitants of icy Bactria and the immense forests of Hyrcania " (III, 267-268) ; " dragging the captive kings of the Hyrcanian forests " (VIII, 342-3).

" Ainçois plus inhumains que les Ours d'Hyrcanie, | Que les Tygres felons qu'enfante l'Arménie " (Robert Garnier, Porcie, 1568, beginning of Act II)

In Arsacome ou l'amitié des Scythes (1609), Princess Masée, daughter of the King of Bosphorus, confronted by Arsacome, Scythian ambassador, whom she loves, exclaims : " O sweet humility ! What hoste d'Hyrcanie | A ton charme entendu ne perdroit sa manie. " (V, 2)

In La Calprenède's Cléopâtre: " un tigre des plus grands & des plus furieux qui fût jamais sorty d'Hyrcanie " (XIe partie, livre 3, éd. 1658, p. 210).

Brébeuf paraphrases and recomposes rather than translates. This is the reference to Book III, approximately vv. 267-268, quoted above in a more literal translation. Georges de Brébeuf's translation of the Pharsale, published in Paris by Antoine de Sommaville in 1657, was a literary event it remained the reference translation until Marmontel's in 1766.

Catherine Volpihac-Auger, notice Arsace et Isménie du Dictionnaire Montesquieu : http://dictionnaire-montesquieu.ens-lyon.fr/fr/article/1376399109/fr/. Montesquieu derives his knowledge of Zoroaster and Hyrcania from Thomas Hyde's Historia religionis veterum Persarum, Oxford, e Theatro Sheldoniano, 1700. Hyde explains where this term Hyrcania comes from: Ea, inquam, dicta fuit Yrâc, unde Nomen Hyrcania q. d. Yracania, quae etiam hodie vocatur Mazenderân atque Tabaristân q. d. Securium Regio (propter caeduas Sylvas in quibus multus usus Securium), " Et on a nommé [le pays des Parthes] Yrâc, d'où vient le nom Hyrcanie, qui veut dire Yracania, qu'on appelle encore aujourd'hui Mazendéran et Tabaristan, qui veut dire Pays des Haches, à cause de leurs futaies, où on fait grand usage de la /// hache. " (2ndth ed. of 1760, chap. 35, note on p. 426).

Montesquieu, Lettres persanes, 1721, éd.P. Vernière et C. Volpihac-Auger, Livre de Poche, 2006, letter LXVII, p.186sq.

Voltaire, Dictionnaire philosophique, article Martyre (1765), ed. R. Naves and O. Ferret, Garnier, 2008, p.280. Voltaire adds : " Fleury, abbé du Loc-Dieu has disgraced his Histoire ecclésiastique by tales that an old woman of good sense would not tell to little children. " That's exactly the kind of tale we're told here...

Genette had already mentioned in Figures V these examples of " figures literalized in act " borrowed from chapter XI of Gargantua.

" ... Mme Verdurin especially, to whom - so accustomed was she to take literally the figurative expressions of the emotions she felt - Doctor Cottard (a young novice in those days) had one day to set her jaw, which she had unhooked for having laughed too much. " (À la recherche du temps perdu, " Du côté de chez Swann ", II, ed. J. Y. Tadié, Gallimard, Pléiade, 1987, t. I, p. 186)

A night in Casablanca, Harpo Holding Up The Building Gag, Marx Brothers, 1935.

Gérard Genette, Métalepse, Seuil, 2004, " De la figure à la fiction ", p. 20.

These conventions are so strong that several editions of L'Ingénu claim that the Huron names mentioned by Voltaire were forged by him.

See on Gallica the Bnf copy RES 8-LK12-730. Gabriel Sagard had taken the monk's name Brother Théodat. His middle name, Théodat, is therefore not strictly speaking part of his author's name. In later editions, the book is signed Gabriel Sagard, comma, Théodat.

Le Tellier was La Chaise's successor as confessor to Louis XIV, which places the story in the 1st decade of the 18th century, later than in the final version.

René Pomeau, " Une esquisse inédite de L'Ingénu ", Revue d'histoire littéraire de la France, n°61, 1961, p. 58-60. The text can be found in vol. IV of Voltaire's Saint Petersburg manuscripts, folio 11.

In the same vein, Diderot evoking President de Brosse in the company of light-hearted girls skeptical of his abilities in bed, writes : " le petit président, qui n'est guère plus grand qu'un Liliputien, dévoila à leurs yeux un mérite si étonnant, si prodigieux, si inattendu que toutes en jetèrent un cri d'admiration " (Salon de 1767, in Diderot, Œuvres, ed. Versini, t. 4, Laffont, Bouquins, 1996, p. 714) The merit of President de Brosse is well worth the male and intrepid virtue of l'Ingénu.

See Utpictura18, notices A0033 and A0016. There are in fact two versions of this engraving, which was censored. In the version authorized by the censor, Madame Parangon's legs in the air have been removed. On this subject, see Benoît Tane's analysis in Avec figures, PUR, 2014.

The engraving reproduced in the GF edition is virtually an engraving avant la lettre, i.e. not the first proof, as the signatures are affixed, but probably the second proof, in which the space for the caption is still left blank. The caption, which at the time generally consisted of a quotation from the text of the scene, was engraved last on the plate. On the Harvard copy (Utpictura18, B7191), the engraving includes the legend, but is undated.

Voltaire

Archive mise à jour depuis 2008

Voltaire

L'esprit des contes

Voltaire, l'esprit des contes

Le conte et le roman

L'héroïsme de l'esprit

Le mot et l'événement

Différence et globalisation

Le Dictionnaire philosophique

Introduction au Dictionnaire philosophique

Voltaire et les Juifs

L'anecdote voltairienne

L'ironie voltairienne

Dialogue et dialogisme dans le Dictionnaire philosophique

Les choses contre les mots

Le cannibalisme idéologique de Voltaire dans le Dictionnaire philosophique

La violence et la loi