To quote this text

Stéphane Lojkine, "Une sémiologie du décalage : Loth à la scène", introduction to La Scène. Littérature et arts visuels, L'Harmattan, March 2001, texts compiled by Marie-Thérèse Mathet

Full text

The line of history, the point of encounter

It seemed that in the beginning there was this road, the road on which Jacques and his master travel, the road that unwinds, at the successive chance of events, the thread of the narrative. For us, this must have been the basis, the fundamental framework of representation: novels tell stories and, at least in classical aesthetics, great painting is history painting.

Or of this road not only do we know almost nothing, but there is nothing to know; Diderot immediately warns us that the essential things lie elsewhere:

"Where did they come from? From the nearest place. Where were they going? Do we know where we're going? What were they saying? The master said nothing."

The narrative route is without origin or destination; there is no master discourse: the magisterium of discursive linearity is a pure illusion. The essential is held by the valet and is not of the order of discourse; speech, yes, but indirect ("Jacques disait que son capitaine disait..."), babbling, digressive.

"Jacques began the story of his loves. It was the afternoon; the weather was heavy; his master fell asleep. Night overtook them in the middle of the fields; there they went astray."

This word puts one to sleep and loses one; it makes one lose the thread, it leads one astray. From the narrative, we topple "into the middle of the fields": only this break, only this gap in a word that is neither narrative nor mastery, but constructs a space where it comes to be diluted, allow access to the stakes of representation, to that something metaphorized by Jacques' depucelage. Of course, this depuculation, which all representation seeks to define and circumscribe, is not the stuff of discourse.

"You see, reader, that I'm well on my way, and that it would be up to me to make you wait a year, two years, three years, for the tale of Jacques' love affairs..."

The metaphor of the path resists and persists, but as a repellent, as the narrator's temptation towards the inessential: "How easy it is to make tales!" The beau chemin narratologique is what needs to be broken, to be cut short in order to get as close as possible to that very material and very mysterious thing, properly incomprehensible, around which representation gravitates and weaves itself.

This something has to do, subversively, with a certain relationship: the relationship of James and his master, the relationship to what presents itself outlawed at the bend in the road, the establishment of a conjunctural link in a moving space that, by eclipses, suddenly makes sense, alongside, in all discontinuity.

The representation is thus situated at the chance of the encounter, in this detour of the itinerary marked by the contradiction of what necessarily happens, in the straight and narrow, "en beau chemin", and of what arises without necessity, in the pure randomness of the world's material immediacy, when the structure having come undone, appears, like a malefic illumination, the incomprehensible irregularity of reality.

"How had they met? By chance, like everyone else."

The basis of representation, the novel's geometric pedestal, is not the road, but the chance encounter, an original and veiled point or knot, an insignificant yet real, anchored departure.

Dialectics of scene and narrative

This means that the novel is only superficially structured by its narrative unfolding. Instead, we'll place the basis of representation in the subversion of this unfolding, in the encounter, in the establishment of the place, in the setting in space of a misguided word, in everything that, away from the "beautiful path", attempts to identify a certain defective but principial relationship to reality, a relationship of which this hazardous encounter, this point constitute the recurring image, the repeated symptom.

This subversion, this connection, this spatialization, materialize in a very familiar, very common, yet a priori elusive phenomenon: it's what we today call a scene. Scene from everyday life (a scandal in a supermarket, two friends reuniting on a station platform), scene from a novel (the first meeting, the ball, the confession), pictorial scene (the sacrifice of Isaac, the Annunciation, the abduction of Europa, the washerwomen at the river), all these scenes belong to different media : Taken on the spot in real life by the indiscreet gaze of the photographer, translated into writing and integrated into the novelistic narrative, recomposed for the space of the canvas and frozen in the immobility of painting, the scenes only reach us after a transposition that distorts them. But they themselves, within the medium in which they have been captured (photography, literature, painting, cinema), deconstruct the apparent structure of representation. Here we touch on a fundamental logical circle, which this book would like to illuminate, if not break:

Representation is undone in the scene, which subverts it; but the scene founds representation, whose rhetorical structures have the essential mission of covering up this original and incomprehensible stain. The scene is thus both subversive and foundational, caught in the crossfire between a blinding, incomprehensible origin and a petrifying structural covering.

.II. The Stage

Loth and his daughters

At the Musée du Louvre, a painting attributed to Lucas de Leyde1 and dating from the first half of the sixteenth century, strikingly represents this fundamental structural ambivalence of the scene, from which the modern system of representation is built. It depicts the flight of Lot and his daughters from burning Sodom.

Attributed to Lucas of Leiden, Loth and his daughters, oil on canvas, 34x48 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre

On the right, the populous city surrounded by the Dead Sea collapses and sinks under the action of celestial fire. At the top left, an empty mineral fortress overlooks the sea: this is Soar, Segor in the Vulgate2. Loth, fearing that he wouldn't have enough time to reach the mountain, as the angels had commanded, obtained that halfway up, Soar, "the little town", would be spared from divine destruction:

" est civitas haec iuxta ad quam possum fugere et salvabor in ea

numquid non modica est et vivet anima mea"

The town here is near enough, where I can flee and be saved.

Is it not a small thing? and my soul shall live (Vulgate, Genesis, XIX, 20.)

Between the two cities, the damned below, the spared above, a tree divides the space of representation, marks the border of the "circuit3" doomed to destruction. From Sodom to Soar, across the canvas, a road winds on stilts along the shores of the salt sea, then rises tortuously up the mountainside. On this road, in small figures, we distinguish, from right to left, Lot's wife, turned back towards her city and, by this gesture, changed into a statue of salt4, then, moving further along, a donkey loaded with luggage, a woman carrying a chest on her head, a second woman, and a man, Lot.

Loth and his daughters are shown a second time in the foreground, away from the road. An encampment has been set up. We can make out three tents, two turret-shaped from behind, and a third, wider and more massive at the front, stretched with red canvas. On the left, in the very foreground, the youngest daughter pours the water she has drawn from her round wineskin at the stream flowing at her father's feet, into the wine of a slender-necked silver hanap. In the center, intoxicated Lot embraces his eldest daughter, seated on the right and still holding against her chest a cup of the wine that served his purposes5. The young woman freezes in anticipation of the incest she deems it her duty to provoke in order to perpetuate the race, i.e. the father's male descendants. Behind Lot and his daughter, the half-open red tent suggests the necessary abomination that must be perpetrated. The tent is illuminated by a torch hanging from its corner, whose fire, on the left, seems to parallel the celestial fire, above right.

The scene as medium and bargain

The scene depicted by Lucas de Leyde opens, then, at a distance from the road, a distance fraught with meaning. After obtaining a shortening of his flight from the angels, Loth fears that Soar will eventually be swallowed up along with the other cities, and continues on his way to the mountain6. The scene is therefore not part of the road that leads from Sodom to Soar, from sin to salvation, according to God's word, but beyond or away from the road, a beyond and a away that recall Abraham and Lot's bargaining and distrust of God.

Sexual transgression, even to perpetuate the race, to make up for the dead mother, has nothing to do with obedience to God's commandments, whose way the road materializes. It is a new bargain with the law, the search for a new mediation between reality and the ethical requirement, in the same way as Abraham's request (that God spare Sodom if he can present him with fifty righteous, or even ten righteous7) or Lot's request (not to flee to the mountains, but only to Soar).

Bargaining, mediation, establishing a link, an in-between space, do not enter into the structure of the story, which progresses from a sinful origin to a redemptive end. The scene is outlawed, or more precisely, out of step with the law, juxta morem universae terrae, in the words of the eldest daughter (31). It touches on an archaic, intimate requirement, on that agreement of self with self that is both impulsive and sublime, which unites, at the principle of the law, below its institution, the origin of the refinement of culture and the unacceptable violence of barbarism.

Scopic denial, prohibition of the gaze

See here the unacceptable, this transient young girl, her face frozen in the inexpressivity of resignation, her arms clasped against her stiff torso, resisting in the unspeakable offering of her body anything that might solicit the desire of the father she has nevertheless provoked with wine. She gives but does not lend; encircled by the hideous beard, the arm that clasps her neck, the hand that knows and caresses her hand placed like a final defense between her knees, she is the sacrificial virgin that the call of the race pushes to the horror of this consumption. She's not looking at her father; she's turned towards the viewer, whose concupiscent gaze she sternly challenges. See here, then, what no one must see, the violence and transgression of incest, which God everywhere else reproves and punishes, but which is perpetrated with impunity by this scene off the road, in the interstice of the law.

Opposed to this chaste figure offered up for rape is the other sister, in the left foreground. As much as one is frozen, stiffened, corseted, the other, in the graceful wiggle of the wine she is mixing, represents seductive femininity and, through the double crevé of her elegant sleeves, through the drape of her red tunic that uncovers a bare foot, embodies the refinement of culture and the delicacy of aesthetically mediated pleasure. Loth caught between his two daughters, the wise virgin in the blue cape and the foolish virgin in the red tunic, embodies the dialectical couple of barbarism and culture, at the symbolic principle of the law, a principle set at the inaccessible distance of the road of representation, which only the break-in of the gaze can, as if inadvertently, thwarting all prohibitions, seize by stealth.

.For the entire scene is placed under the sign of the forbidden gaze. The three women, in the three planes of the performance, echo each other to reflect this interdict:

.

First, in the background on the right, is Lot's wife, frozen in the killing spectacle of Sodom in flames. To turn towards Sodom is to participate in its infamy: she will therefore be turned into a statue of salt. Yet it is with impunity that the viewer of the canvas can revel in the forbidden spectacle of the city in flames: aesthetic mediation not only authorizes participation in the unspeakable, but consists in this participation. Representation precipitates the subject into the scopic abyss, neantizing it in the scene. But at the same time, the shift of the stage preserves the subject, who finds himself precipitated to the side, as it were, for nothing: the scenic abyss is merely an illusion in which the death of the self is reflected.

Then, in the center, the eldest daughter seated and draped in her blue cape, by looking at us, transgresses the principle of representation's autonomy. Like her mother's, her gaze is a return to a forbidden beyond. We meet her blank stare with an accusation that's hard to sustain. Embarrassed, we slip, only to return again and again to this disturbing underlining: our gaze, here again, will participate in the unspeakable, will endorse incest and even wash its eye of it.

Finally, on the left, the youngest daughter preparing the wine is the woman removed from view; she hypocritically turns away from the infamous scene she has incited. In contrast to her mother, she is the one who does not look, so that the central couple appears caught between two upturned women, as if enclosed in an invisible circle that strikes them as forbidden.

The geometrical space is signifying; the material device is symbolic

The stage is that floating space of the visible that is surrounded and threatened by the forbidden, the violence, the ignominy of that which, in the real, in a transgressive way, has to do with the law. The floating, shifting nature of the scenic space is materialized here by the tents of the camp. It's in the half-open tent, whose slit reveals the ready layer, that the horror of what's shown to us up front is consummated. But this tent is not only the convenient place, the practical resolution for the act. Its shape is reminiscent of the rock of Soar, which itself replicates, symmetrically on the other side of the Dead Sea, the contours of proud Sodom. The pictorial space is thus constructed by translation of the same outline, the same habitacle, the damned city turning into the preserved city, to project itself synthetically into this unspeakable scene at the threshold of the tent, neither pure nor impure, at once all good and all evil.

At the foot of the tent rises the tree that divides the canvas in two, that divides good and evil. But this tree, which takes root from behind Lot's eldest daughter, symbolizes at the same time the descent of Abraham's nephew: Lot's eldest son will be Moab; Ruth the Moabitess, through her union with Boaz, will be David's foremother: Moab thus enters the Jesse tree. Yet neither the Moabites nor the Ammonites, the descendants of Lot's youngest daughter, belong to the tribes of Israel. At the end of the Exodus, the Moabites refused the Hebrews entry to the land of Canaan and tried to have them cursed through Balaam. The Ammonites are defeated by Jephthah, Saul and David. Psalms and prophets resound with curses against these millennia-old enemies.

The space of the stage is thus both materially and symbolically circumscribed:

Materially, it is given to view at the front of the tent. The young virgin's blue cloak envelops the incestuous couple in the manner already of a tent. The geometrical nature of the space is underlined by this perspective of the cloak, the tent, the citadel and, by reversion, Sodom.

Materially, the incestuous couple are shown in front of the tent.

Symbolically, something is at stake here, a disturbing encounter that works and informs the whole scene, building it on the scandalous indifferentiation of barbarism and culture, violence and law, salvation and curse. A space of defection from the biblical word, of symbolic recession, of regression to the principial horror of an unspeakable representation of origin, between the shadow of night and the blaze of divine wrath, the scene is the reversal of outside into inside, of the exteriority of flight and encampment into the intimate consummation of incest, incest itself substituting for the stranger of desire the familiar, identical figure of the consanguine. The passage from the road to the tent is the same passage as that from the Other to the Same: the space of the stage is this Moebius ring that involutes without a break the barbarity of the world into the unquestioning intimacy of the female womb.

This space, at once material (a place surrounded and offset, at the edge of the road, at the very edge of what's at stake) and symbolic (a place beyond the Law, an involution of the world), we'll call a device.

Tabernacular involution, symbolic principle of the scene

The tent is the device of the scene. It represents the translation of Sodom into Soar, the principal moment of its reversal. Its sexual significance is doubly marked: not only does it half-open to let the incestuous couple enter, but just above it the road that passes under the rock represents penetration. The tent is thus the principal vacillation of the law and the cleft of the female sex.

The Vulgate speaks not of a tent, but of a cave:

"et mansit in spelunca ipse et duae filiae eius." (Genesis, XIX, 30.)

The painter here has not painted the passage actually described in the Bible, but its allegorical interpretation. The tent can only evoke the biblical tabernaculum, both the Tent where the Ark of the Covenant rests and, by metaphor, Mary's womb, receptacle of the incarnate God. We saw that the tree prefigured the Jesse tree, because Lot's son, Moab, would be the ancestor of Ruth, grandmother of David, himself an ancestor of Christ. The blue cloak of Lot's eldest daughter, traditionally and symbolically, is Mary's cloak.

The transgressive reversal peculiar to the scenic device is thus vividly manifested: this moment of incest, this unspeakable abjection, is at the same time the founding moment of Christ's genealogy, and, by the same token, the moment of the law's recapture. Through and in the scene, the law is undone and remade, the symbolic institution is stripped down to its unspeakable principle and rebuilt.

.The vector of this refoundation has to do with the flesh, with the womb, with feminine jouissance. The reversal of the situation that often triggers the scene's dramatic spring proceeds from the involution tabernacular: the raw exteriority of reality, the conjunct materiality of the world, the vague space outside, is introjected into the restricted space of the stage, corporatized in its device: the space of the city in flames becomes the cloak of the virgin to be raped, whose jouissance will establish what takes the place of a Jesse tree; its branches then join the celestial fire, as in an inverted annunciation. The scenic ignition is at once the destruction of the old world (Sodom in flames), the outburst, the horrific explosion of the pregnant instant (the enjoyment of the forbidden virgin) and the announcement of the refounding illumination, of the genealogy of Christ.

The punctum of the stump

Another detail on the canvas supports our hypothesis of a symbolic refoundation through the feminine. In the right foreground, an old hollow tree stump appears, illuminated by the light of the torch hanging from the corner of the tent. The stump is perforated on the left, creating a strange silhouette on the surface of what remains of the trunk - the very silhouette of Lot's wife, petrified at the gates of her city. Indeed, Lucas de Leyde depicted this woman at a bend in the log walkway that serves as a road, turned around in front of one of the pilings: the piling forms a dark spot on her left hand, the same yellow-grey color as the silhouette into which it virtually merges. We find the same shape in black on the stump, the woman wrapped in her cloak and the pilotis in front of her to her left8.

Loth's wife gave no male offspring: his tree is a dead stump. But from the dead stump, a few steps away, in the slight shift of the scene, springs the living tree that somehow unites the damned woman with the principle of celestial fire. Incest safeguards and perpetuates the mother's body, making it a participant in divinity. The shadow of the stump is the conjunctural detail at which the gaze stumbles on the margins of the scene: it is that original, veiled point that meets by chance and where the principial neantization of the spectator is metaphorized, since what is given to see by the painter is forbidden to look at by God and the law.

.III. Genealogy of the scene

The medieval image

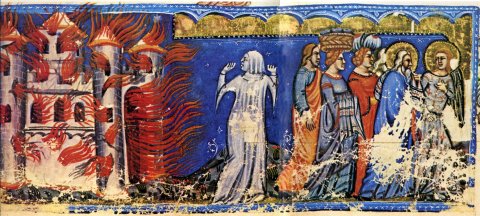

The Burning of Sodom, illumination from the Naples Bible, 14th century, Vienna, Austrian National Library

Of course, the scene painted by Lucas of Leyden is not emblematic of every scene: it would be futile to deny the arbitrary element that makes us choose it here to open our investigation. And yet, although it does not by any means model everything that follows, this scene does appear to be an inaugural one. The iconography of the biblical episode is abundant and, above all, spans several centuries.

Take this illumination from the Naples Bible9: incest is not depicted. Medieval iconography favors the flight from Sodom.

On the left, the city is a fortress in flames; on the right the two angels, recognizable by their halos, guide Lot's two daughters, who carry their luggage on their heads. In the center, Lot's wife, turned inside out and transformed into a white statue of salt, clearly articulates the allegorical message of what is depicted. From left to right, we slide from the damned to the elect: the unfolding of meaning is linear; narration and exegesis follow the same discursive thread. The performance space is not a device, and has no geometric depth. Behind the characters, a blue band is stretched. They unfurl on this band. The iconographic origin of the motif is therefore the road, and the road alone: in the beginning, there is no scene.

From the false road to the scene: Dürer and Veronese

A. Dürer, Loth and his daughters fleeing burning Sodom, 1497, oil on wood, 50x32.5 cm, Washington, National Gallery of Art

This type of linear representation continued to develop during and even after the Renaissance. Dürer depicts Lot's flight on the back of the Madonna Haller10 ; Veronese foregrounds the graceful walk of two young girls and an angel11 ; Rubens even returns to the bandeau composition, depicting the processional exit of Lot and his two daughters accompanied by the two angels12. Yet while the road remains the formal framework of representation, competing structuring systems are emerging. In Dürer's work, as in the Leyden painting, the sinuosity of the road allows Lot's flight in the foreground and the burning of Sodom in the background to be superimposed, rather than linked, introducing for the eye that fundamental gap between road and ignition, between the linearity of discourse and the focal point of the scene. In Veronese's work, the two daughters of Lot framing the angel in the foreground, in the manner of the damsels in Botticelli's Spring, constitute the basic device of the representation, a device that is reduplicated in the second and third planes: the angel's arm extended to the left in the foreground is taken up by the same extended arm of the second angel who, in the background, is dragging Lot along, and, in an inverted fashion, by the silhouette of the salt statue in the background on the right.

Veronese, Loth and his daughters, c. 1580-1585, oil on canvas, 128x262 cm, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum

The springtime stroll, small wicker basket under arm, in the laughing setting of a Pastoral grove, turns into a petrified vision of the woman seized with horror at Sodom in flames, isolated, detached in the spectacle of abjection. From Sodom to the maidens with the angel, the journey, the allegorical and moral unfolding of the road, has been transformed into an itinerary for the foundation of the scopic, an itinerary based on a reversal, a revolt of the senses, a subversive displacement of the symbolic: from the principial horror of the unrepresentable to the joyful pacification represented by this sheepfold parade, the meaning of the biblical scene has been hijacked. The Epicurean invitation to enter the out-of-the-way places of a locus amœnus singularly subverts the moral significance of the punishment of Sodom, and transforms the tragic scene of incest against a backdrop of fire into the ironic, light-hearted perspective of a pleasant game of pleasure. The performance is the staging of this transformation13.

Crispijn de Passe I, Abraham looks at the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, Lot and his daughters, 1580, copperplate engraving, Leiden, Hoogheemraadschap van Rijnland, University of Leiden

The shift from the linear structuring characteristic of medieval representation to a structuring based on a scopic reversal device is particularly noticeable in an engraving by Cripijn de Passe I, which arranges the double event of Sodom's destruction and Lot's drunkenness under the judgmental gaze of Abraham14. The road crosses the drawing. In the lower right, the angels are pursuing a path on which Lot and his daughters have stopped, from which they have turned aside. As for the two episodes, the fire and the incest; they are both linearly juxtaposed at Abraham's eye level and embraced by him in a single field of representation.

Abraham's presence, however, remains exceptional in this type of representation. More often than not, the scopic reversal is assumed by the otherwise more striking figure of Lot's wife detached from behind facing the fire: a tiny point in both Dürer and Veronese, she seems pushed to the margins of the scene and at the same time constitutes its crystallizing point, through which it makes sense. Through this upturned figure, through this shadow or white outline that painting situates at the limit of the representable, the genre scene - in Dürer a man and two women hurrying along a road, in Veronese strollers enjoying themselves in a wood - is brought back to history painting, and recovered in extremis as a biblical scene.

Loth's wife, the turning point of the device: Rubens

P. P. Rubens, Loth's family leaving Sodom, 1625, oil on canvas, 74x118 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. 1760

The scopic dimension of the scene brings into play this fundamental gap, this latency of the symbolic frame : to go back and forth from the genre scene to the biblical scene, from what is scattered on the road to what is framed in the device, something of the order of the conjunctural, a point that has to do with an encounter, must operate this reversal, this divesting and reseizing constitutive of the scene, in its dimension at once geometrical (road/dispositive), scopic (principial horror/ pacified spectacle) and symbolic (moral meaning/subversion). This something is assumed here by Lot's wife, seized by the horror of the visible and thereby divested of herself, a figure turned inside out and thereby a figure of reversal, a marginal and tiny sign, almost no sign, crystallized and disseminated.

.Rubens also operates this détournement, which enables the advent of the scopic in representation, and thereby historically inaugurates the advent of the stage. Rubens' detour is both more insidious and, in its semiological consequences, more radical. On the surface, the unfolding of the blindfold episode obeys the strictest iconographic orthodoxy as established in medieval models. Unlike Dürer or Veronese, Rubens did not play with different planes. The representation is frontal, with virtually no perspective effects. On the left, the towers and gate of Sodom see Lot, his wife, his two daughters and the two angels exit in procession, exactly as in the Naples Bible illumination.

.Yet, on close inspection, the figures don't come out in the expected order. The last to emerge should be Lot's wife, who can't tear herself away from the cursed city. It is she who should appear on the left, half-turned or even already petrified and bleached. At first glance, the woman in white carrying a basket on her head should be Lot's wife; her enigmatic gaze seems to represent the imminence of the reversal. Yet this bare-haired girl, like the buxom young woman in red who immediately precedes her with her arched gait, can only be Lot's daughters advancing behind their mother, whose status as matron is represented by the white headdress covering her head, the severe dark-blue dress and the sagging features of an already faded face. Lot's wife, urged on by the angel, hands clasped in the manner of a brave penitent, is thus the central figure of the representation, which is ordered from her into two symmetrical groups: on the right, Lot led by an angel and resisting him; on the left, the young girls leading the donkey and the little dog.

The dog's solemn gait parodies that of the donkey's weightless one, and undoes the biblical message: it's carrying all the pleasures of the most futile luxury, that Lot's family undertakes the journey. The smiles of the two angels contrast with the frowning faces of the parents and the ambiguous tranquility of the daughters. For this disastrous departure, this hurried journey that disrupts the bourgeois serenity of a wealthy Flemish family is above all a genre scene.

.Divine retribution is not forgotten, however. First of all, above the little troupe, there's this terrible group of exterminating angels, similar to the furies or discords of mythological scenes. While symbolically the punishment is aimed primarily at the city, the geometrical structure of Rubens' painting gives these angels another, shifted purpose: intended to frame the scene, they overlook not the city, but the small group of those who must escape the punishment, even if Lot's wife is involved. Here, then, the shift from the stage to the road is not manifested geometrically by the drawing of a road and, at its margin, by the opening of a stage space. This principial shift is fully integrated, internalized by the semiotic structure of Ruben's representation: the scene is the road, at once unrolled as a strip and framed by the exterminating angels; at once deported to the right by the movement of flight and fixed, centered on the couple formed by Lot's wife turning towards the laughing angel. It is around this central couple that the two daughters on the left, and Lot and the second laughing angel on the right, are distributed.

On either side of the upturned mother, but turned offset not towards the city that will kill her, but towards the angel who temporarily suspends her petrification, the two groups diverge in a V-shaped structure characteristic of Rubenian composition15 : the arch of the eldest daughter, the roundness of the younger daughter's raised arm pulls them back, to the left, while the laughing angel at the head of the little troop, forcing Lot's arm, pushes them forward, to the right. The V is at once the principle of divergence and convergence, the narrative of the road and the iconicity of the scenic device.

.Rubens here contradictorily captures Lot's family in its dramatically ultimate union and tragically programmed disunion: it's not just the mother's death that is outlined with her reversal, but the daughters' incestuous union with the father, with whom the mother, through the play of folds and colors of fabrics, pictorially establishes the link: blue and red in the eldest daughter (blue for faith, red for sexual consumption), blue in the mother complemented by the red of her angel, red and blue in the father's angel. This central yet mute position of the mother, displaced and sacrificed, may find personal resonance in Rubens' family history: here it is once again the molested father's rush to the other forbidden woman (Anne of Saxony) that is represented and legitimized, as the triumph of flesh over law, as the refoundation of law16.

The mother interposes and effaces herself; she embodies herself in a reversal that is not so much scopic as carnal; she is the reversal of flesh proper to jouissance taken as intimate revolt, as the conjunction of law and its subversion, of drawing and color, of discourse and image, of road and stage. Here we are preparing for what will constitute the classical structure of the stage: the screen device.

The classic scene: Lot's drunkenness

Orazio Gentileschi, Loth and his daughters, oil on canvas, 226x282 cm, Bilbao, Museo de Bellas Artes

The seventeenth century favored another depiction of Lot, no longer his escape from Sodom, but his drunkenness and incest with his daughters in the mountains: the road disappears and the scene invades the space of the canvas. The space is now completely framed. The allegorical meaning loses its obviousness. Vouet17 or Gentileschi18 depict an excited or sated old man between two young girls. The composition becomes a libertine pretext, like so many paintings that announce unconvincingly on the frame label, display or wall, a Suzanne et les vieillards or a Charité romaine.

The characters lean on a totally artificial stone factory in this scene, which should be set in the middle of a mountain. The factory reinforces the scene's geometric foundation.

The scenic device is organized, within the rectangular frame formed by the jug, the horizontal branch, the lightning-stricken trunk and the pond, into a dynamic circle rotating the father's bust and the daughters' arms around a central, blind point, located in the center of the canvas. This squaring of the circle, this spinning, which precipitates the gesture of pouring and drinking wine in a vertigo prefiguring drunkenness, constitutes the scene's properly scopic dimension: drunkenness, and the incest it prepares, are not merely signified by attributes, coded objects - the jug, the cup, the wine. The eye, caught in this circle that precipitates it towards an emptiness, experiences this intoxication sensitively; through this historically new scopic dimension, the canvas functions as a trap for the gaze, a trap set in abyme by the subject of the representation, the trap set for Lot by his daughters. The viewer is caught in the same trap as Loth, is drawn into the same circular vertigo.

Simon Vouet, Loth and his daughters, 1633, oil on canvas, 160x130 cm, Strasbourg, Musée des beaux-arts

Rembrandt adopted the same type of device at the same period. His lost painting is known only through Jan Van Vliet's engraving19, naturally reversed from the original. Loth leaning against the knees of one of his daughters establishes the geometrical foundation of the scene, while the chiaroscuro produced by his inverted cup brandished in front of the torch traps the viewer's gaze, fascinated by this shiny black circle, which both concentrates meaning (the empty cup signifies Loth's drunkenness, which signifies incest) and neantizes it: look at this cup; inside, there's nothing. A screen device opens up here.

However, at this stage of representation, the device remains unaccomplished: scopic neantization does not lead to symbolic crystallization. In Le Guerchin's work, the eye, rushing to the center of the canvas, encounters nothing, where it should experience nothing, where it should stumble at the point of neantization that turns nothing into the signification of a "something", the something at stake in the scene. In Rembrandt's more subtle work, nothingness is designated by the cup. As a material object and empty ocelli, it opens onto the scopic dynamic of "something", between neantization and refoundation. But the cup is a counterpart to Lot's wife and Sodom in flames, without being superimposed on them. The screen remains partial; the allegorical play of references is not yet condensed into a pure scenic device.

Guerchin, Loth and his daughters, 1617, oil on canvas, 175x190 cm, Monastery of San Lorenzo, Escorial

The aim, then, was both to unify the representation and to fill the central, principial void of the scene; to fill it not only with something that signified this nothingness, but with a proscenium that placed the horrifying marginality of symbolic transgression at the center of the representation : This is why, in the 1650 Dresden version, Le Guerchin shifts Lot's wife, petrified at the forbidden spectacle, back to Sodom, to the center of the performance: the front stage then becomes what obscures, or rather frames, the back stage. The ban on incest circumvents the scopic ban. The scene functions both as a screen for another scene and as a lifting of this screen, as a representation of the forbidden and as a transgression of this forbidden: we see with impunity Sodom, which Lot's wife cannot see without being petrified; similarly, Lot's daughters prepare and perpetrate with impunity the incest that the law forbids:

."No man of you shall approach the flesh of his body to discover its nakedness: I am Yahweh!

The nakedness of your father and the nakedness of your mother you shall not uncover; this is your mother, you shall not uncover her nakedness." (Leviticus, XVIII, 6-7.)

Jan Joris van Vliet after Rembrandt, Loth and his daughters, etching and burin, Amsterdam, museum het Rembrandthuis

The essential word is nudity20, i.e., even before consumption, the simple vision of the parents' body, understood as an extension of one's own body. Incest is the impossible vision of one's own flesh as a desirable exteriority. To see nudity, to discover the father's or mother's body, is to see oneself as a sexual object, confusing what belongs to the Same with what belongs to the Other. The prohibition of sodomy, moreover, immediately follows the prohibition of incest, as the same crime of confusion between identity and otherness: Sodom in flames and Lot seduced represent the transgression of the same prohibition.

Discovering Lot's nudity is what's at stake in the scene. Le Guerchin, in the 1650 version, has placed Loth face-on and almost naked, a simple cloth covering his knees. To Loth's subtracted nudity, this missing phallus corresponds the petrification of Loth's wife, arranged like an erect phallus. From one to the other, the turpitudo is uncovered and covered; the eye experiences a slight shift in relation to the center of the scene, the very shift that always articulates the geometrical device of the scene to a scopic vertigo. This time, neantization is represented as the neantization of the paternal phallus through the petrification of Lot's wife.

Guerchin, Loth and his daughters, 1650, oil on canvas, 176x225 cm, Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

The drunken scene thus screens the reversal of Lot's wife, which constitutes the fright of the primitive scene, always already there, but in the background of what is almost not represented. Drunkenness fascinates, unsettles the eyes, distracts the gaze from the father's forbidden nudity, that nudity we cannot discover without discovering ourselves as other, or rather, in reverse, without damaging the world's otherness in the repetition of self. The stage is threatened by this involution of the world into the self: the burning of Sodom, the ignition that precipitates the fascinated gaze towards this incestuous confusion, constitutes the dangerous jouissance of the stage, which is cut off, diverted, regulated, by the pacifying screen, the legislator of the device.

Le Guerchin, Loth and his daughters, 1651, oil on canvas, 172x222 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv.75

In the 1651 version, this device reaches its perfection: with the arms and legs of Loth and his eldest daughter dressed in red, the painter restores the spinning that already precipitated the scopic vertigo in 1617, but had disappeared when the screen was introduced in 1650.

Loth's wife and Sodom in flames come within this circle: the city's glow corresponds to the young girl's red tunic; it's even concupiscence. A double shift cleverly unbalances the device: the circle is shifted to the right; within the circle, the fire is shifted to the left, bringing it almost back to the center of the canvas. On the left-hand side of the canvas, the youngest daughter turns away to peer at the scene from behind Lot's back. She metaphorizes the voyeuristic position of the viewer, who feasts on what the painting has to offer. Opposed to this gaze, which he ignores, Loth now shields the viewer with his upturned body; the eldest daughter turns to pour the wine, and with this gesture indecently offers her rump to be desired. In this way, all the characters are characterized by reversal, a reversal that signifies both law and disobedience to law, enjoyment and punishment.

Conclusion

The stage device, when it reaches maturity and unfolds in its scopic dimension, appears regulated by a screen. Lot's incest screens the burning of Sodom, which God forbids us to contemplate. The screen-scene conceals the primordial violence of what burns beyond representation. The screen organizes and attenuates the fundamentally subversive dimension of the scene, which is first and foremost a deviation from the road, a geometrical and symbolic shift, a digression and a transgression. To this initial shift, he superimposes a counter-shift that refocuses the "something" at stake: in the Louvre painting by Guerchin, the scene shifted to the right is superimposed on the fire, itself, in relation to it, shifted to the left. The screen formed by Lot's body, which prevents his youngest daughter from seeing the scene, rebalances to the left what, in the swirling drunkenness and red incandescence of the tunic and the city, had shifted the double transgression to the right. The intrusion, the voyeurism, all the half-open doors and open windows that ensure the visibility of what's at stake, shift the unfolding of the scene in relation to the device. But this shift, which is not the primary shift inherent in the scene, always unfolding away from the road, at once digressive and transgressive, turns out to function much more as a recentering: the screen resemiotizes in extremis what escaped the line of the road and the narrative; the gaze that enshrines and disposes of the scene brings it back in the last instance to something that is of the order of the narrative.

Until this gaze itself is undone...

There has been no attempt, in these introductory pages, to weigh down the demonstration with a conceptual apparatus that the body of the book will endeavor, progressively, to perfect. The scene is first and foremost something we see, and we wanted, from the outset, to show it. We therefore preferred to talk about routes, rather than discursive logic and rhetoric. We described one and then of devices, without immediately defining the device as a dialectic of θέατρον and σκήνη. There has been vague talk of the advent of a certain scopic dimension to the stage, without defining this dimension as the interplay of the visible and the visual.

Let's get back to the road. Initially, the scene will be considered from a rhetorical perspective, a perspective whose referential and shifted character we suggested at the outset. The scene is constructed in relation to a discourse (and in this sense constitutes its amplification) and is constructed alongside, or even against, this discourse. It places before the eyes (through hypotyposis), but since what it places is not of the textual order of the τύπος, the mark, the character, the type, it steals it away, so to speak, in the very movement of exposing it.

In a second step, the scene will be considered in its problematic dimension of theatricality, which makes it float from the materiality of the visible to that "visual" beyond which it both brings into play and absents. In the painting by the Leyden school, we saw how the tent, a metaphor for the tabernacle, constituted the major device of the scene. This tent, in Greek σκήνη, delimits the scenic space as both theatrical (profane) and processional, i.e. a space where the ritual of presentification of the divine is played out: where the half-open, visible interior of the tent is the visual but forbidden interiority of Mary's body. Yet this ritualized celebration of the "event" only takes center stage on the "occasion" of a scandalous transgression, in the brilliance of an encounter that radically desacralizes it. A gap then emerges between the sublime object targeted by the hypotyposis and the visual, material, unintelligible "something", pointed at, stripped bare by the scene.

This problematic gap manifests itself in the indeterminacy of the "something" that in the scene is at stake, and whose study will occupy the final part of this book. The "something" catches up with the gap, resynchronizing what this problematic theatricality, this work of the gaze on the stage, had brought into play. Something crystallizes and dazzles, blinding the eye. The brilliance of the scandal, the fulgurance of the recollection, the poignant immediacy of the pain that understands everything can constitute this catching-up of the scene by the structure, this "ignition" that symbolically recovers the scenic slip. The beyond that is fleetingly discovered and turned upside down in this moment of ignition is the fire of Sodom, whose dread petrifies, this fire that brings us back to moral law and obedience, from which the incestuous proscenium had, for a moment, jubilantly distracted us.

.Notes

And the eldest said to the youngest: our father is old and there is no man left on this earth who can come upon us according to the custom of all the earth. Come, let's get him drunk and sleep with him, so we can perpetuate our father's race. So they gave their father wine to drink that night, and the eldest slept with her father.

Lucas de Leyden (c. 1494-1533), Loth and his daughters, c. 1520, oil on canvas, 48x34 cm.

We quote the biblical text systematically in the Latin of the Vulgate, which was overwhelmingly the text read in the first half of the sixteenth century.

"nec stes in omni circa regione", 17 ; "et subvertit civitates has et omnem circa regionem", 25; "cum enim subverteret Deus civitates regionis illius", 29.

"Respiciensque uxor eius post se versa est in statuam salis", 26.

" Dixitque maior ad minorem pater noster senex est et nullus virorum mansit in terra qui possit ingredi ad nos iuxta morem universae terrae. Veni inbriemus eum vino dormiamusque cum eo ut servare possimus ex patre nostro semen. Dederunt itaque patri suo bibere vinum nocte illa et ingressa est maior dormivitque cum patre"(31-32).

"Ascenditque Loth de Segor et mansit in monte, duae quoque filiae eius cum eo ; timuerat enim manere in Segor et mansit in spelunca ipse et duae filiae eius" (30), Loth ascended from Soar and stayed in the mountain, and his two daughters with him; indeed, he feared to stay in Soar and stayed in a cave, he and his two daughters.

Genesis, XVIII, 23-32.

Can we see here a figure of the one who holds the phallus and, through the stump, in haunting and conjuring, comes to inhabit the scene haphazardly?

The Naples Bible, 14th century manuscript, National Library of Austria.

Albrecht Dürer, Loth and His Daughters Fleeing Sodom in Flames, circa 1497, oil on wood, 50x32.5 cm, National Gallery of Arts (Samuel H. Kress Collection), Washington D.C., panel painted on reverse of Haller Madonna.

Paolo Caliari, known as Veronese, Old and New Testament Cycle (Duke of Buckingham series), Loth and His Daughters (c. 1585), canvas, 138x262 cm, Vienna, Kunsthistorishes Museum.

Peter-Paul Rubens, Loth's Family Leaving Sodom, oil on wood, 74x118 cm, 1625, dated and signed PE. PA. RUBENS. FE AO 1625, Paris, Musée du Louvre.

Veronese is no stranger to this kind of detour. Just look at his Enlèvement d'Europe, also constructed in three shots representing three successive times in the narrative, where the young girl terrified by the bull's violence has turned into a coquettish courtesan adjusting her hairdo one last time in the final preparations for a pleasant cruise (S. Lojkine, Image and Subversion, "Balthsar's Coat or the Screen of Representation", pp. 47-51.)

Crispijn de Passe I (c. 1565-1637), made after 1580, Abraham watches the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, Lot and his daughters (University of Leiden).

See our analysis of the Ixion deceived by Juno from the Musée du Louvre (Image and subversion, "Ixion king").

See S. Lojkine, "De Silène molesté à la chair blanche des nymphes: bacchanale et rire des dieux chez Rubens".

Simon Vouet, Loth and his daughters, 160x130 cm, signed and dated 1633, Strasbourg, Musée des Beaux-Arts.

Orazio Gentileschi, Loth and his daughters, oil on canvas, 226x282.5 cm, 1st half of the seventeenth century, Bilbao Museum of Fine Arts.

Jan Van Vlier, after a now-lost painting by Rembrandt, Loth and his daughters, engraving and burin, state II, Museum het Rembrandthuis. (Reproduced above.)

turpitudo, in the Vulgate: the ugly and shameful body. It will be noted that Leviticus cares little for the violence a father might exert on his children, which is the modern, social approach to incest.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Une sémiologie du décalage : Loth à la scène », introduction à La Scène. Littérature et arts visuels, L’Harmattan, mars 2001, textes réunis par Marie-Thérèse Mathet

Fiction, illustration, peinture

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Fiction, illustration, peinture

La scène de roman

La scène de roman : introduction

Renaud dans le jardin d’Armide

Rastignac chez Mme de Restaud

Gilberte derrière les aubépines

La poignée de porte de tante Berthe

La double aporie du topos

Illustrer la fiction

Molière, une parole débordée

Marillier, l’appel du mièvre

On n'y voit rien

Illustrations de l'utopie au XVIIIe siècle

Le temps des images

Du conte au roman graphique

Déconstruire l’illustration

Régimes de la représentation dans la gravure d’illustration classique

Penser la fiction depuis la peinture

Une sémiologie du décalage : Loth à la scène

Introduction à la scène comme dispositif : Paolo et Francesca

La main tendue, le regard démasqué

De Silène molesté à la chair blanche des nymphes

Chambres de la représentation

L'intimité de Gertrude

Brutalités invisibles

Parodie et pastiche de Poe et de Conan Doyle dans Le Mystère de la chambre jaune de Gaston Leroux

Le dispositif de la chambre double dans Les Démons de Dostoïevski

Scène pour voir et chambre des brutalités

La Princesse de Clèves

L’invention de la scène dans le roman français

La canne des Indes

L'aveu

La princesse, la religieuse et l'idiot

Richardson

Entre scandale et leurre

Introduction aux Lettres angloises, ou histoire de miss Clarisse Harlove, par Samuel Richardson