To quote this text

Stéphane Lojkine, "L'aveu... La Princesse de Clèves ou l'écran classique", La Scène de roman, Armand Colin, collection U, 2002, p. 78-98.

Full text

Mme de Lafayette didn't write novels in the modern sense. It is in the tradition of the short story initiated in Italy by The Decameron of Boccaccio (1350-1353), illustrated in France by L'Heptaméron of Marguerite de Navarre (1559) that we should rather inscribe the most famous of her works, La Princesse de Clèves : this short novel written in 1678 is itself organized according to a complex system of embedded narratives which, taken in isolation, constitute so many short stories.

The short story develops in the context of the decomposition of the epic : from the general shift from performance to narrative, noticeable in the great allegorical novels, it withdraws the requirement for a narrative structure. But from the sequential structure of the epic, it retains the brief form, the requirement to center the narrative around one " adventure ". The short story rarely stands alone : the collection of short stories, more or less loosely linked together by a common enunciation device, replaces the collection of sequences constituted by the chanson de geste, or the first medieval novel (XIIe-XIIIe centuries).

The novelty of La Princesse de Clèves lies in the extreme rigor of the narrative sequence that hierarchizes and links all the stories in the novel around the tragedy of Mme de Clèves.

But this narrative tightening is counterbalanced by an opening up of the " adventure " to the stage. The word scene does not belong to Mme de Lafayette's vocabulary. Speaking of the scene at the jeweller's, at the beginning of the novel, she refers to " l'aventure qui avait arrivé à M. de Clèves " (p. 251). But this adventure is summed up in a vision : " L'aventure qui avait arrivé à M. de Clèves, d'avoir vu le premier Mlle de Chartres ".

The medieval adventure thus discreetly tips over into the device of the classical stage. This shift is only made possible by a profound transformation of the general system of representation, which is no longer centered on the medieval marvel, but also has very little to do with the realist requirement that, from the nineteenth century onwards, is placed at the heart of representation.

The medieval adventure is thus discreetly shifted into the device of the classical stage.

We'll begin by recalling the theoretical principles of classical representation, based on three sometimes contradictory requirements the story must be plausible the character is constructed as a character it must respect decorum.

In a second step, we'll show how the stage develops within classical representation, both as its principle and as its deconstruction, its subversion.

Finally we will analyze, in the confession scene and the portrait scene, the device of the classical scene and the screen that regulates its operation.

I. The classic novelistic standard : verisimilitude versus realism, propriety versus psychology

The realist model of novel writing

For us, a novel tells a story within a documented social and historical framework. Even if the story isn't true, it could have happened the way we read it, and in any case, even if false, or romanticized, this story gives us a realistic picture, an instructive picture of the reality to which it refers. Balzac describes real Restoration society, even if the characters in the Comédie humaine are invented. Zola describes the France of the Industrial Revolution, even if the Rougon-Macquart genealogy is pure fiction. As for Monsieur Madeleine /// alias Jean Valjean, to Gavroche, Fantine and Cosette, if Victor Hugo made them mythical figures, these figures evolve against a backdrop of Misérables that refers to a historical and social reality that has its own objective and documentary value. Historians have no hesitation in using the text of Flaubert's L'Education sentimentale as a document of the 1848 revolution, even if the hero of this novel, Frédéric Moreau, and the characters around him are invented.

It's no coincidence that we've taken all our examples from nineteenth-century literature. Beyond the stylistic and ideological oppositions, the schools and currents that divided the writers of this century (the realism of a Balzac, the naturalism of a Zola...) a model of novelistic writing was constituted here and has become for us the classic reference[1].

Classical verisimilitude[2]

The literature that precedes the nineteenth century in no way operates on this model. One might even say that its relationship to reality is a priori nil. This statement seems paradoxical and outrageous. We'll have to qualify it. Let's start by noting that the words " réel ", " réalité ", " réalisme " are not words of the classical era.

.In fact, in both the novel and critical literature of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it's never a question of fiction's documentary relationship with reality, but of the reader's or spectator's adherence to the fiction. The story must seem " true ", it must be " plausible ", we must be able to believe in its " verisimilitude ".

To read quickly, it might seem that they're the same thing : isn't a plausible story one that could happen in reality ? Isn't it realistic ?

You only have to look at what was concretely considered plausible or implausible in the novels or theater of the classical era to understand that it has nothing to do with realism. It was implausible, in Corneille's Le Cid, for Chimène to forgive Rodrigue his father's death and marry him. Let's recall the plot Rodrigue's father slapped by Chimène's father orders his son to avenge him in a duel. Rodrigue, despite his love for Chimène, to obey his father and out of loyalty to his honor, challenges Chimène's father to a duel and kills him[3]. Chimène then demands revenge. The king arranges a judicial duel : Rodrigue wins the duel and the king orders Chimène and Rodrigue to marry. Chimène's forgiveness is, if you like, realistic : not so much because the judicial duel and the king's order are undeniable historical facts, but because in such circumstances Chimène, driven by events, was in the necessity and interest of forgiving. But Chimène's forgiveness is not vraisemblable verisimilitude is a matter of principle. Chimène, a tragic heroine in the same way as Rodrigue, acts by her forgiveness in contradiction with her principles, with her loyalty to her father and to her honor. This break-up has every possible justification in the play. But it contradicts Chimène's own values. If Chimène belongs to the aristocratic world, she cannot break her fidelity, since the rules of aristocratic honor must always take precedence over the demands of love. So there's a mechanical contradiction here: the values of the world to which Chimène belongs presuppose, dictate a type of conduct Chimène's forgiveness does not obey this code. It is therefore implausible. In this system of representation, there's no question of changing character along the way. The reversals of /// psychological interiority are an invention of the nineteenth century.

Conclude. Realism establishes a relationship between fiction and reality, that is, in semiological terms, between the sign (literature is a world of signs) and the referent (reality is what signs refer to). Verisimilitude establishes a relationship between fiction and the reader's belief, acceptance and horizon of expectation, i.e., in semiological terms, a relationship within the sign between the signifier (the story as told) and the signified (the reader's deciphering of the story according to implicit codes that will give it meaning). Realism refers to a documentary exteriority of the text (Balzac and the Restoration, Zola and the Industrial Revolution, Flaubert and the 1848 Revolution). Plausibility is a question of the internal economy of the novel or play, of conformity between the story and the implicit codes that make this story function symbolically (Rodrigue has heart, i.e. birth and courage in other words, he obeys the aristocratic code : therefore he will avenge his father and win all duels Chimène has heart : therefore it is not likely that she will forgive Rodrigue for the murder of his father). These codes have no external existence. There is no manual, no dictionary of codes to guarantee the verisimilitude of the story. Fiction produces its own codes, and it's the story's conformity with the code that produces the reader's adherence, the story's verisimilitude.

The code of decorum

What exactly is this code that fiction produces, whose respect guarantees the verisimilitude of the story ? This code, though implicit and unwritten, is not arbitrary. It defines the symbolic order of the world, that is, the system of values, the moral and social rules that govern the world in which the characters evolve.

Or we must never forget that this world is not the real world, but a beautiful world that never existed. At the antipodes of a reality deemed trivial and disappointing, this idealized world appears governed, structured by rules whose perfect mechanics proceed from the regularity of the automaton and not from the sensitive irregularity of the living. The aristocratic code to which Corneille's heroes submit is a theatrical code that bears little relation to the historical reality of social relations between feudal lords, or even between seventeenth-century aristocrats. To borrow a phrase from Thomas Pavel, the art of classical fiction is an art of distance from reality[4].

These rules, this code define what in the seventeenth century was called bienéances. Bienéant is what suits well, i.e. what is appropriate, what it is fitting to do, what the public, society, readers expect us to do. An action that does not conform to propriety is an implausible action.

Properties are therefore not an absolute and universal code of conduct, for which we could reconstitute a kind of general manual that would constitute the symbolic framework of all classical literature. Propriety establishes an articulation between a character and his or her story, or more precisely, in seventeenth-century terms, between a character and his or her actions: propriety is the ethics of character. Seventeenth-century characters are not built around a psychological interiority of conscience that would see them evolve and transform over the course of the story, either through learning about the world, or through corruption in it. The character is stylized within a character. But within the same world, within the same system of decorum, characters are differentiated by a trait, a passion, a requirement we saw how loyalty to aristocratic honor defined the /// Mme de Clèves' marital fidelity defines, in a different context, the system of decorum that guides all her actions. Character introduces a flaw, a lack, a principle of contradiction into this fidelity: passion is stronger than honor, in Chimène virtue is more powerful than simple conjugal fidelity in Mme de Clèves. In comedy, the character's unseemly behavior exacerbates this constitutive character flaw to the point of parodying the entire system of propriety one need only think of Molière's avarice in Harpagon, Dom Juan's libertinism, Alceste's misanthropy, Argan's hypochondria.

.To sum up, there is a strong relationship in classical literature between the character of the character, the propriety that drives his actions (insofar at least as they do not contradict the character's constitutive trait) and the verisimilitude of the story that tells them. The story is judged plausible not for its documentary realism, but for its conformity to the reader's expectations, i.e. for the propriety of the actions it features : when we admire La Princesse de Clèvesbecause it imitates the Court well[5], it's the ritual of the Court we're thinking of, its decorum, its etiquette, not the documented description of places and costumes, the authenticity of anecdotes, the historical accuracy of descriptions. In fact, description is almost non-existent in the novel, and indications of setting or acting are practically non-existent in the theater of Corneille, Racine, or even Molière verisimilitude doesn't describe it tells us the values, rituals and codes of the world it represents. Imitation has nothing to do with the visual, geometrical or technical reproduction of reality to imitate is to free the symbolic framework of the world, to project one's ideology onto an ideal support. Imitation perfects, simplifies and amplifies the world by making fixed characters evolve in an uncluttered, perfect space.

.II. The stage as a spectacle of transgressed propriety

Classical verisimilitude is an ideal requirement weighing on seventeenth-century representation, not an absolute reality of that representation. The staging of characters, necessary for any representation, necessarily triggers infringements, contradictions, implausibilities. Incessantly, we cry scandal and enjoy the subversive pleasure of seeing this verisimilitude spectacularly thwarted. We've seen how Chimène's pardon contravened all the rules; at the same time, it produced a sensational effect and ensured the play's public success. Since character is constituted by a trait of passion, a unique but permanent departure from the system of decorum, the representation of character is the representation of this departure, this transgression Chimène's pardon contravenes decorum and thus produces an effect of implausibility for the spectator but it represents Chimène's passion, i.e. her character. The transgression of classical verisimilitude constitutes the scene, in its spectacular, visual, theatrical dimension, of scandal and enjoyment in scandal. The stage is the implausibility of the story, i.e. both the moment when we step outside the norm and, through this stepping outside the norm, it provides the means to indirectly designate, to show from the outside this invisible norm, this implicit code, this mute discourse of propriety that would otherwise be impossible to represent.

Paradox of classical representation

Paradoxically, even as classical fiction seeks to define itself as an exercise in verisimilitude, i.e. as the realization of a performance expected by the audience, as the actualization of a code, a ritual socially and culturally shared by the community of recipients of the performance, only the transgression of this /// This transgression of verisimilitude produces the spectacular effect and aesthetic pleasure we're looking for. What's more, it's only this transgression that makes it possible to designate by its reverse, to enunciate, as it were, negatively, indirectly, a code, a symbolic framework, a system of performance that constitute the unrepresentable signified of representation. The stage both destroys and founds the system of classical representation. It ruins verisimilitude, but it also negatively designates its founding ambiguity: verisimilitude proclaims itself to be a true imitation of the world; but this true imitation of the world refers not to the world as referent (reality), but to the world as signified (propriety, the social institution). Through implausibility, the stage shifts the representation of theatrical performance, closed in on itself, towards a deconstructive openness to the real.

.Why is this shift absolutely necessary ? We've seen that the function of the stage is to denounce, to designate in transgression a code of propriety that, in a direct way, always escapes representation. But the scene has more than just a symbolic function. It unlocks the narrative.

Classical verisimilitude blocks narrative. Centered on the performance that tells the symbolic structure of the world, classical representation freezes, immobilizes itself in the closed field of characters corseted in their immutable rules, their incommunicable worlds, their contradictory and muzzling demands. Everything that drives the dynamics of romance is implausible: falling in love, getting rid of enemies, fleeing, betraying, meeting and making love are all contraventions of propriety. Roland Barthes has shown how the space of the stage, in Racinian tragedy, imprisons the actors in a no-man's land where all action is impossible outside the motionless expectation of a death that, even it, can only come from outside[6]. This neutralized space of the tragic stage, eternal antechamber of the neither-outside-nor-inside, aptly sums up the paralysis into which classical verisimilitude plunges representation.

Contradiction of classical narrative

You've got to get out, you've got to move, you've got to move forward. Unlike the oral epic, indefinitely extensible, susceptible to all manner of additions and retrenchments, the written, composed narrative tends rhetorically, necessarily towards an end, not just an epilogue, but a goal. It cannot therefore be satisfied with the performative immobility to which verisimilitude confines it.

Narration therefore consists in weaving with propriety to reach - as close as possible to verisimilitude - the end, the ends of the narrative, to fulfill the requirement of the end. This requirement is rhetorical: the performance must follow a course, unfold its lineaments. But it is also a requirement of pleasure : the end of the narrative is the object of the spectator's desire, an object ceaselessly stolen, diverted, forbidden by verisimilitude, ceaselessly designated to his novelistic appetite, as the visible object of a subversive satisfaction towards which he locks himself up and rushes.

The tension between the novelistic aim and the obstacle of verisimilitude sometimes eases in the detour, in narrative indirection[7], sometimes exacerbates and crystallizes in the implausible transgression of propriety : then, moment of crisis, rebellious relaxation, the scene erupts.

The confession scene : preliminary slip-ups

The story of La Princesse de Clèves is simple. The young Mlle de Chartres marries M. de Clèves, a handsome gentleman passionately in love with her, by reason, without compulsion but without passion. Immediately after the wedding, she and the handsome young Duc de Nemours fall madly in love. But out of marital fidelity, Mme de Clèves never yields to the Duke's advances, even after his death. /// husband. The most famous scene in the novel is the one in which Mme de Clèves confesses her guilty passion to her husband, while assuring him of her fidelity[8]. The Duc de Nemours observes this confession on the sly.

The narration that prepares this surprised confession must lead the Duc de Nemours to the scene's location, the Château de Coulommiers, where the princess has withdrawn from the court to escape the torture of seeing the man she loves there every day without letting anything of her love show. The duke, who doesn't know he's loved, can't come to Coulommiers : a young man doesn't pay a gallant visit to a married woman without being invited.

.M. de Nemours had been very sorry not to have seen Mme de Clèves since that after-dinner he had spent with her so pleasantly and which had increased his hopes. He had an impatience to see her again that gave him no rest, so when the king returned to Paris, he resolved to go and stay with his sister, the Duchess de Mercœur, who was in the country quite near Coulommiers. He proposed to the vidame to go there with him, who readily accepted this proposal ; and M. de Nemours made it in the hope of seeing Mme de Clèves and going to her house with the vidame. " (P. 331.)

The narration is completely inhabited by the Duc de Nemours' desire and reveals his end from the outset: to see Mme de Clèves again (" the pain of not having seen Mme de Clèves ", " an impatience to see her that gave him no rest ", " in the hope of seeing Mme de Clèves ").

Yet this action, which seems so simple, doesn't happen, or more exactly takes a detour. The fiery duke proceeds by leaps and bounds. With the king, he first returns north from Compiègne to Paris, close enough to Coulommiers[9] to go back and forth without appearing to the court to have been absent. But that's not all: " he resolved to go and stay with his sister, the Duchesse de Mercœur, who was in the country quite near Coulommiers ". Mme de Lafayette doesn't explicitly tell us why M. de Nemours doesn't go directly to Mme de Clèves. The prohibition of propriety remains implicit. M. de Nemours' sister is a literary indirection she is a means for the Duke to approach in all propriety " close enough to Coulommiers ", as close as possible to the scene. By announcing and, at the same time, delaying Nemours' scene in Coulommiers, Mme de Lafayette designates this scene as an object of future enjoyment for the reader. The narrative tends towards this object, with the Duke's desire here superimposed on the reader's desire.

But how does one go from sister to princess ? The vidame de Chartres, Mme de Clèves' uncle, is at the same time the friend of the duc de Nemours, and closes the loop of the narrative detour : it would be in keeping with propriety for the duc de Nemours to accompany his friend the vidame de Chartres to the latter's niece.

.

We see that the narrative is by no means written arbitrarily everything here is motivated by the dual, contradictory requirements of the duke's desire and his respect for propriety, of the goal of enjoyment towards which the narrative tends and the verisimilitude that blocks the narrative. By the end of the paragraph, the elements of the Meccano are in place and the narrative tension is resolved.

However, things won't go according to the announced and planned scenario. Something goes wrong and short-circuits the narrative loop:

.

Mme de Mercœur received them with great joy and thought of nothing but entertaining them and giving them all the pleasures of the countryside. As they were hunting for deer, M. de Nemours strayed into the forest. When he asked which way he should go to return, he knew he was close to Coulommiers. At the word "Coulommiers", without making /// Without a second thought, and without knowing what his purpose was, he sped off in the direction he was shown. He arrived in the forest and allowed himself to be led at random along carefully made roads, which he judged to lead to the castle. (Continued from previous.)

The ideal world of classical verisimilitude assumes a lavish reception on the part of Mme de Mercœur. The first aristocratic pleasure of the countryside is the pleasure of the hunt. So far, the proposals follow one another with absolute necessity. But Nemours on the hunt goes astray: the circumstantial and the contingent intrude on this regulated mechanism. Wandering through the forest at random in a space without roads, without direction, marks the entry of reality into the world of fiction[10].

The chance of a stray path through the forest thwarts Nemours' cleverly scaffolded plans. This interference of chance, this intrusion of reality, is very fleeting (" M. de Nemours s'égara dans la forêt "). But they are clues to the passage to the scene[11]. Coulommiers magnetically attracts Nemours (" without making any reflection and without knowing what his purpose was ") in contrast to all the actions of the previous paragraph, skilfully decided and reflected upon (" he resolved to ", " in the hope of "). The place imposes itself on his desire, the materiality of the path leads Nemours from indecision and the well-behaved detour to decision and transgression.

.Note here that if the confession scene was deemed implausible by Mme de Lafayette's contemporary critics, it was not at all because of M. de Nemours' actions, but because of the nature of Mme de Clèves' confession, whose symbolic stakes are unquestionably far more important. What we want to show here is that the question of verisimilitude does not only, exceptionally, engage the two or three coups d'éclat of the narrative, but informs and conditions the slightest elements of its weave. Implausibility is not just a matter of morality and content. It is the technical ingredient needed to set the scene.

III. Device and screen

Setting up the device

Arrival in the setting is marked by a gradual return to the ideal perfection of the fictional world. From wandering in the forest, we've moved on to the " roads made with care " that must lead to the place where idealization is perfected and fulfilled, the château.

The narrative then undergoes a new detour, encountering a new obstacle before the end of the road, which is at the same time the end of the narrative[12] : Nemours is stopped at the entrance to the park by a hunting lodge. The location of the scene is defined from the outset as an " en deçà ", as close as possible to the thing, but somehow shielding it.

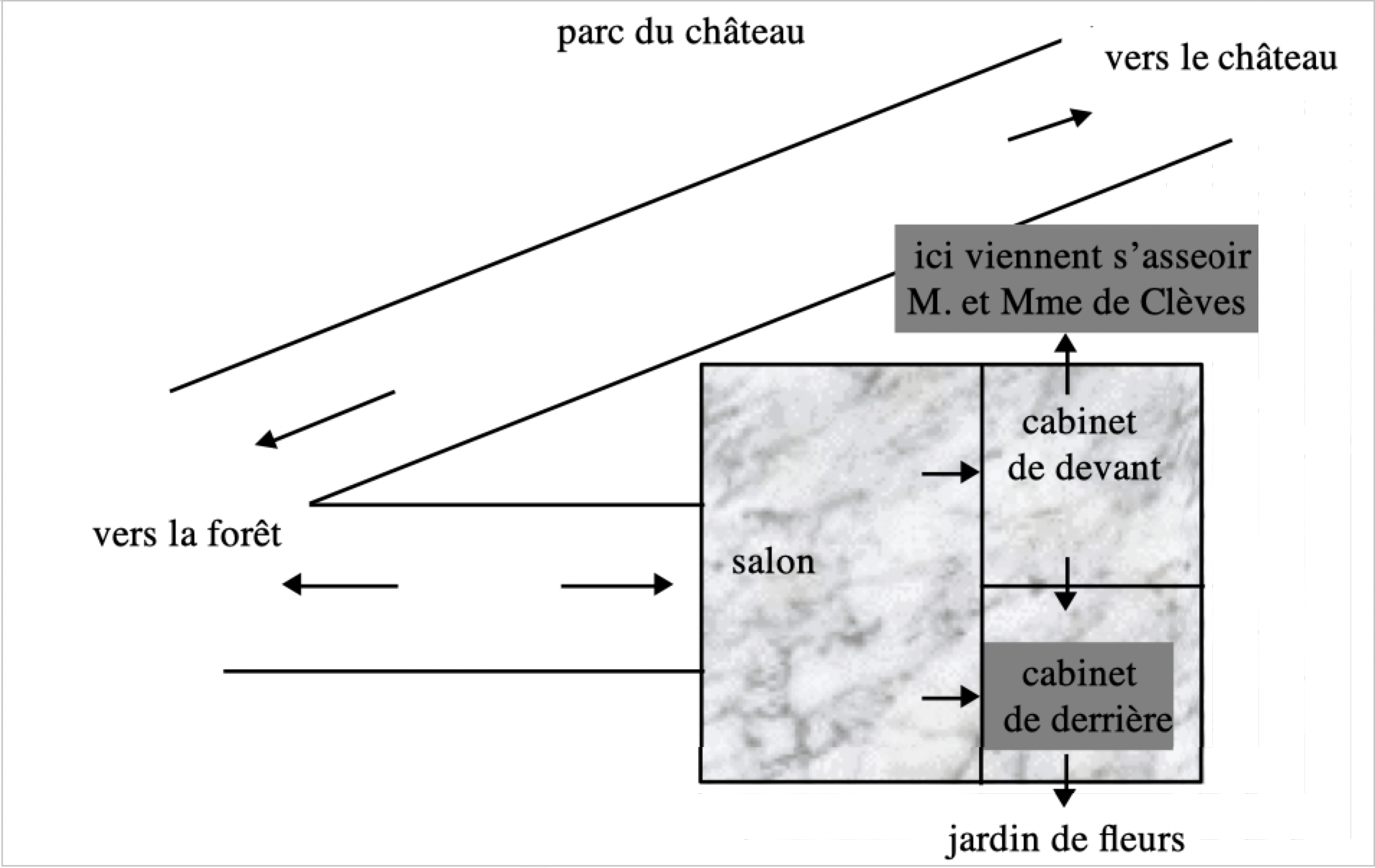

At the end of these roads he found a pavilion, the underside of which was a large salon accompanied by two cabinets, one of which was open onto a flower garden, which was separated from the forest only by palisades, and the second overlooked a large driveway in the park. He entered the pavilion, and would have paused to gaze at its beauty, had he not seen M. and Mme de Clèves, accompanied by a large number of servants, coming down this park alley. As he had not expected to find M. de Clèves de Clèves, whom he had left with the king, his first instinct was to hide: he entered the study overlooking the flower garden, with the intention of exiting through a door opening onto the forest; but, seeing that Mme de Clèves and her husband were seated under the pavilion, that their servants were in the park, and that they could not come to him without passing through the place where M. and Mme de Clèves were, he couldn't refuse to enter. /// pleasure of seeing this princess, nor resist the curiosity of listening to her conversation with a husband who gave her more jealousy than any of her rivals. " (Continued from previous.)

The pavilion in front of which the confession scene takes place is meticulously described. This description is quite exceptional in a story stripped of all unnecessary notation. Ordinarily, places are not qualified and are only valuable in terms of their relationship to court ritual : public or private space, open or intimate, space intended for rest, conversation, play, ball, the setting of the narrative has no depth and is defined not as the arrangement of a space, but as an index of the ritual of sociability that applies there.

Here, although far from the colorful luxury of Flaubertian descriptions, the openings and room layouts are noted elliptically, yet precisely. The description takes the form of an architect's plan. The pavilion has two floors. The first floor has three rooms. From the forest road, one enters a salon, from which one can pass into two cabinets, one, at the front, overlooking the château, the other, at the back, overlooking a garden that leads back to the forest. M. de Nemours crosses the salon and passes into the front cabinet, which " overlooked a large avenue in the park ". But here, he sees M. and Mme de Clèves coming down the park alley and at first turns back, not towards the salon from where he would be seen exiting onto that same alley, but towards the back cabinet, from where he could reach the forest unseen.

The pavilion[13] thus functions as an airlock between the forest and the castle. It's the setting for the scene, but a shifted one, since everything will take place " under the pavilion ", i.e. in front of it. Here we find the slight gap constitutive of the scene : in Canto xvi of the Jérusalem délivrée, Armide's garden is quasi centro al giro, almost in the center of the enclosure.

The pavilion allows the Duc de Nemours to witness, as a spectator-viewer, Mme de Clèves' absolutely private, intimate confession to her husband. It, too, therefore, falls within the scope of novelistic indirection, but this indirection does not take the form of a detour, a narrative loop on the contrary, it circumscribes a space of the scene.

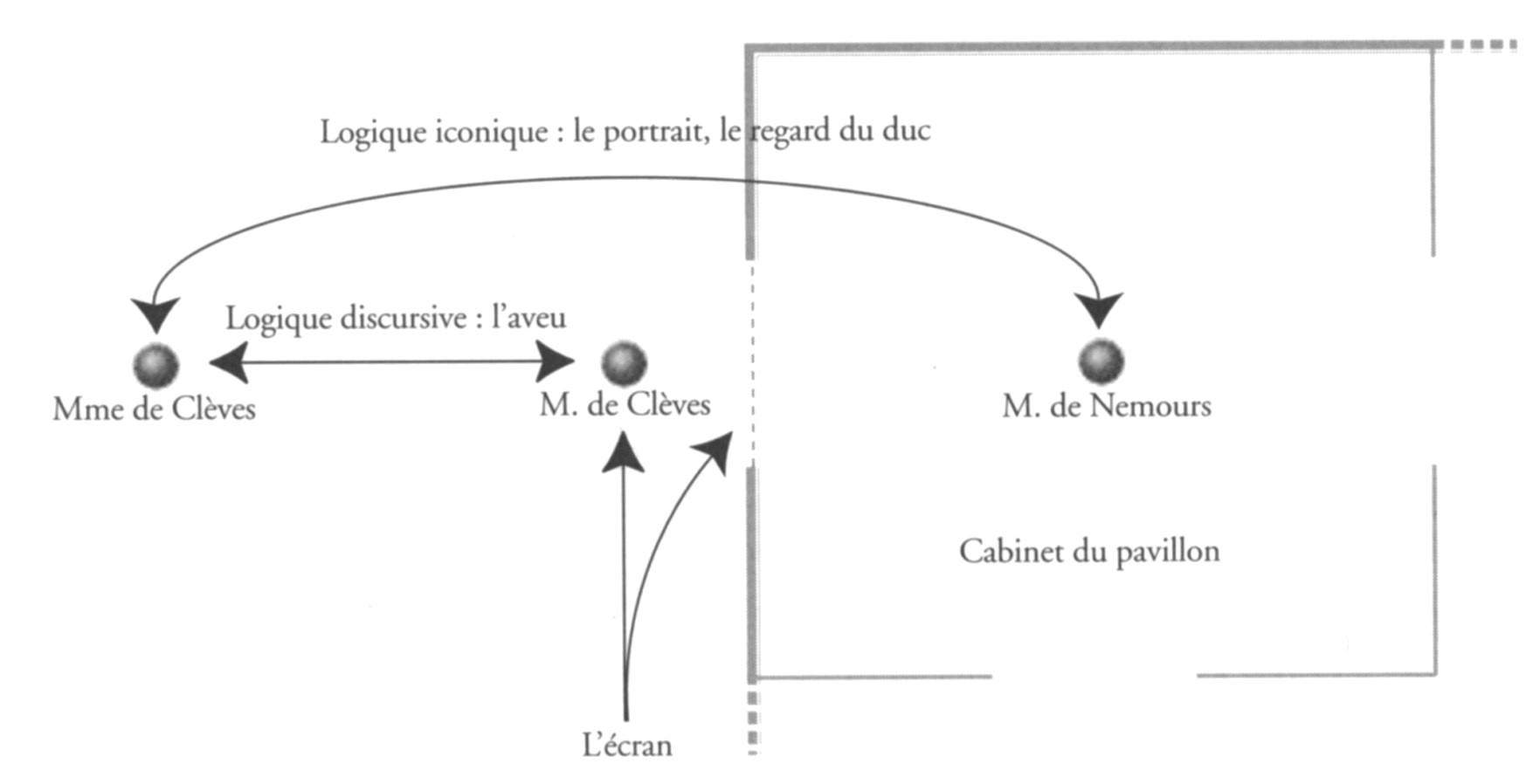

The screen of the stage : gap and cut

The confession is made " under the pavilion "[14]. The whole play of the scene consists in this gap between the place where theatrical discourse takes place, where Mme de Clèves' pathetic tirade is declaimed, and the blind spot from which M. de Nemours' desiring but absent, invisible gaze departs. The pavilion establishes a material, geometrical screen between the two lovers, a screen symbolically redoubled by the presence of the husband: the pavilion renders Nemours invisible; M. de Clèves forbids Nemours, symbolically denying him access to Mme de Clèves. The scene is thus traversed by a screen whose function is not simply to cut the scene, but to introduce a double shift, firstly in relation to the road (the park path) and the discursive logic it metaphorizes, and secondly in relation to the Duc de Nemours who, reduced to an invisible eye, nevertheless constitutes the essential stakes of the scene, the focal point of this . /// jouissance which is here both envisaged by the confession and in the same movement forbidden by it.

The gap between the theatrical site of the confession and the pavilion from which it is seen orders the geometrical dimension of the screen device and enables the passage from discursive line to stage space the cut defines the symbolic function of the screen : it separates the site of the signifier, where the words of the confession are spoken, and the site of the signified, the pavilion cabinet where these words are received, interpreted and understood. The screen materializes the semiotic cut[15], which divides the sign into signifier and signified. The screen also sanctions, with all the brutality and intensity of the dramatic moment, the symbolic castration that forbids Nemours the function of the phallus and, on the basis of this prohibition, founds the symbolic institution, or in other words what the text and context designate as propriety.

The dynamics of the scene lie in the articulation between, on the one hand, the vague, on the one hand, the vague, indirect, periphrastic formulation of a desire around which Mme de Clèves' speech revolves, and whose erotic thrill is nevertheless conveyed by the Duc de Nemours' furtive glance, and, on the other, the system of decorum that forbids the formulation of this desire. The prohibition is expressed for her by her speech, for him by the walls of the pavilion that keep him at a distance.

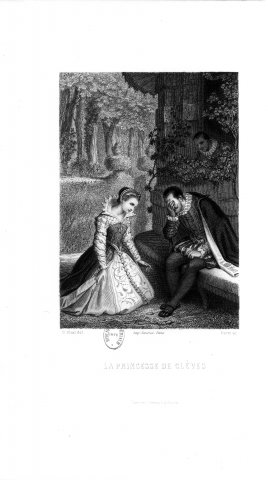

Figure 3 : L'aveu, steel engraving by Moret after the drawing by G. Staal, from Œuvres de Mme de Lafayette, La Bibliothèque amusante, Paris, Garnier frères, 1863, in-8°, after p. 321. Cote Bnf Imprimés Z42515. M. de Clèves covers his eyes in despair, echoing Agamemnon's gesture in Timante's sacrifice of Iphigénie (chap. IV, fig. 2).

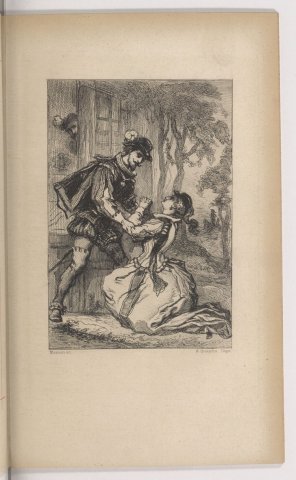

Figure 4 : L'aveu, engraving by Masson from Mme de Lafayette, La Princesse de Clèves, Quantin, 1878, in-8°, after p. 188, Bnf Imprimés 8°Z567(3). Spanish costume refers to the seventeenth century. M. de clèves standing as a screen between Nemours and Mme de Clèves.

Or paradoxically, propriety is not opposed to the raw demand of jouissance, but quite the contrary proceeds from it : Mme de Clèves' speech does not deny, but confesses the drive the pavilion wall does not hide, but on the contrary reveals the confession. The symbolic institution doesn't build itself against the temptations of the flesh it represents this temptation through the stage, on which it seeks to hold an acceptable discourse. The dynamic of jouissance is thus mobilized to circumvent propriety: but this circumvention is the means by which it is represented. jouissance thus emerges as the symbolic principle of the scene, which both covers and reveals /// the screen.

Discursive logic

To fully understand the interplay of the real and the symbolic, of vague space and restricted space in this double movement of occultation and revelation operated by the screen, we must not confine ourselves to the arrangement of characters and places, but return to the very text of the confession and its dramaturgical effect :

Well, sir, she replied, throwing herself on his knees, I'm going to make you a confession that one has never made to one's husband ; but the innocence of my conduct and my intentions gives me the strength to do so. It's true that I have reasons for distancing myself from the court, and that I want to avoid the perils that people of my age sometimes find themselves in. I have never shown any sign of weakness, and I would not be afraid of showing it if you gave me the freedom to withdraw from court, or if I still had Mme de Chartres to help guide me. However dangerous the course I am taking, I take it gladly to keep myself worthy of being yours. I beg a thousand pardons, if my feelings displease you, at least I will never displease you by my actions. Consider that to do what I do, one must have more friendship and more esteem for a husband than one has ever had ; lead me, have pity on me, and love me still, if you can. " (Pp. 333-334.)

The most extraordinary thing about this confession is that it says absolutely nothing. The princess's speech refers to no event, and above all reveals no identity. There's more: by its very theatricality, the speech evacuates any possibility of content and, in the dialogue that follows it, Mme de Clèves stubbornly refuses to give the slightest detail.

The key word of the confession is " conduct " : Mme de Clèves first insists on " the innocence of my conduct " she then regrets that Mme de Chartres her mother, who died shortly after her marriage, is no longer there " to help lead me ", i.e. to guide her with her advice. Finally, she proposes that M. de Clèves take on this role: " Lead me, have pity on me, and love me ". Conduct refers directly to propriety according to the principle we set out above, the transgression of propriety constituted by the confession (a woman must not confess to her husband that she loves another man) has the essential function of stating these propriety, which would otherwise always remain implicit. It is these proprieties that lead Mme de Clèves to flee the Court to escape the " perils in which people of my age sometimes find themselves ".

But what periphrases ! This confession, which caused such a scandal among readers, what does it say ? It says nothing. What are these perils ? What are these " reasons for distancing myself from the court " ? It's not even a question of who, but simply what.

Once again, we touch on the fundamental unrealism of classic literature. The confession confesses not reality, but truth, which is not a matter of events, but of propriety. Mme de Clèves reminds us of this: " I have the strength to keep silent about what I believe I should not say. The confession I made to you was not out of weakness, and it takes more courage to confess this truth than to undertake to hide it. " (P. 335.)

However, this grandiloquent speech, which delivers no information, is so clear that it has the effect of a bomb. What does it mean? Not by the events, actions or people it refers to, but by the very fact of its existence as discourse and, in the theatricality of the gesture of the young woman who falls at her husband's knee like a tragic supplicant, by the performance it implements. Here, discursive logic is defeated (discourse says nothing) in favor of a logic of performance in which the visual dimension plays a major role.

M. de Clèves était demeuré, /// during all this speech, his head leaning on his hands, out of himself, and he hadn't thought of getting his wife up. (P. 334.)

Here, the discourse becomes a tableau : to write " ce discours " is to distance oneself from what has just been said, to signify that it is no longer a question of entering into the detail of Mme de Clèves' sequence of sentences, but of stepping back, of seeing all the meaning carried by the position of the two spouses. A transition takes place, from an economy of text, where it is the discourse that signifies, to an economy of image, where the set-up of the scene makes sense. Not only does Mme de Clèves perform and signify a confession by throwing herself on her knees, a confession which, despite the abundance of words, is never verbalized, but M. de Clèves' position, with his head in the air, is also a sign that the scene has been transformed. It was by veiling Agamemnon's face that Timantius, one of the most famous painters of antiquity, depicted the father's grief at his daughter's sacrifice[16]. The veiled face is a screen archetype, even before the Albertian spatialization of the device. Reclaimed by classical culture, it no longer expresses the paroxysmal power of a pain that becomes impossible to represent, but rather the semiotic cut that here literally bars M. de Clèves " hors de lui-même ", the passionate husband is dispossessed of his own body. His hands barring his eyes say that he could not see this scene of which he was the screen. They corporalize the forbidden gaze.

At the level of discourse, M; de Clèves is thus annihilated by the content of el'aveu. At the level of image, his gaze is barred by the gesture of his hands held up to his eyes. The text insists on this failure of the body, which is not supported by any speech, but which the visual suspense of the painting underlines when M. de Clèves raises his eyes. Silence then falls on the sublime vision of Mme de Clèves' face :

When she had ceased speaking, when he cast his eyes upon her, when he saw her on his knees with her face covered in tears and so admirably beautiful, he thought he would die of pain " (continued from previous).

The climax of the scene is this moment of exchange of glances[17], when the sight of the other's face produces a veritable deflagration of meaning. This moment out of step with the discourse, this pregnant instant that follows the confession and prepares M. de Clèves for death, combines the perspectives of jouissance (in the face of " admirable beauty ") and death (" to die of pain ") : the scene swings from discursive logic, from textual norm, to an iconic logic carrying transgression.

Iconic logic

But the play of glances towards which the scene swings immediately brings us back to the Duc de Nemours, a pure gaze symbolically forbidden to speak insofar as speech is there only to represent propriety. Nemours reduced to the scopic drive receives the speech of confession with the same frustration as M. de Clèves, for he cannot guess that he is the man the princess is fleeing :

M. de Nemours didn't lose a word of this conversation ; and what Mme de Clèves had just said gave him scarcely less jealousy than it did her husband. He was so madly in love with her that he thought everyone had the same feelings. (P. 113.)

Discursive logic therefore also fails at this second level. It is then that M. de Clèves remembers " de l'embarras où vous fûtes le jour que votre portrait se perdit ". Mme de Clèves is then forced to confess that the man she loves is the one who stole her portrait. This information, which does not enlighten M. de Clèves, has a completely different effect on M. de Nemours " What Mme de Clèves had said of /// his portrait had given her back her life by letting her know that it was him she didn't hate..." (P. 115.) Through the detail of the portrait, the information bypasses the screen to reach the real and unexpected recipient of the confession, the Duc de Nemours : against all decorum, the scene here turns out to be one of declaration of love, a scene whose initiative belongs not only to a woman, but to an adulterous woman at heart.

.The communication this time is not through speech, but through reference to the portrait of the beloved woman's face. It's the iconic dimension of a play of glances superimposing two effractions (first Mme de Clèves seeing the portrait taken, then M. de Nemours seeing the confession) that short-circuits the prohibitions of verisimilitude : it's in complete honesty and impunity that Mme de Clèves thus keeps silent in front of her husband and communicates with her lover.

The scene thus appears as a scene with a double background behind the confession of a woman to her husband, Mme de Lafayette represents the declaration of love of a woman to her lover.

The confession is a matter of discursive logic but says nothing it initiates a deconstructive dynamic which, from the climactic moment when Mme de Clèves' beauty bursts forth, will lead M. de Clèves to his death.

The declaration of love, on the other hand, is a matter of iconic logic. It is a portrait, itself integrated into a complex network of exchanges of glances, that conveys meaning. The declaration of love symbolically refounds the scene by giving it its positive structure, a structure that is not of the order of text, but of device.

IV. When wonder resists the screen : the portrait scene

The confession scene is prepared by another scene, during which M. de Nemours has stolen the portrait through which iconic communication may precisely take place, Mme de Clèves' indirect declaration of love to M. de Nemours in front of the Coulommier hunting lodge.

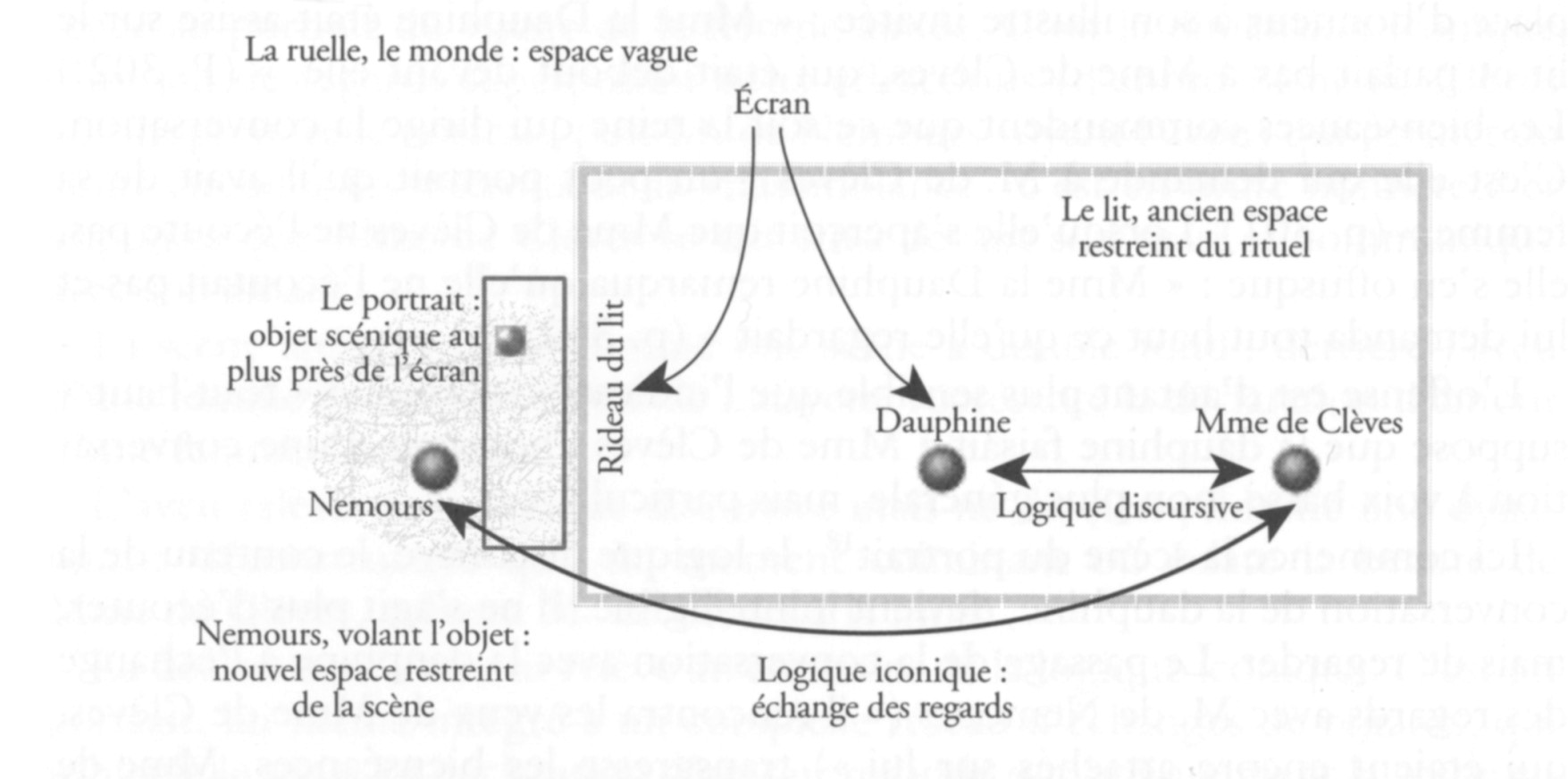

The Queen Dauphine has commissioned a painter to paint " small portraits of all the beautiful people of the Court to send to the Queen her mother " in England. From the outset, the portrait is presented as an object of communication. The painter went from princely residence to royal apartment to paint the ladies in their own homes. On the day the portrait of Mme de Clèves is to be completed at her home in the Hôtel de Clèves, the Queen Dauphine comes to spend the afternoon with him, presumably to take delivery of the object when it is finished.

.Without further explanation, Mme de Lafayette adds that " M. de Nemours did not fail to be there ". The Queen Dauphine's visit is therefore part of the public social visits that a court lady like Mme de Clèves is obliged to receive every afternoon in her alley, i.e. beside her bed. M. de Nemours cannot be forbidden entry in this social context, which assumes that Mme de Clèves' room is full of people. Further on, Mme de Lafayette mentions in passing : " tout le monde dit son sentiment... " It is precisely to escape this dangerous ritual of worldly visits that Mme de Clèves will retire to Coulommiers.

The hierarchy that places the queen dauphine above Mme de Clèves obliges the latter, who must ordinarily receive seated on her bed, to cede this place of honor to her illustrious guest : " Mme la Dauphine was seated on the bed and spoke low to Mme de Clèves, who was standing before her. " (P. 302.) Propriety commands that it be the queen who directs the conversation. It is she who asks M. de Clèves for " a small portrait he had of his wife " (p. 301). When she realizes that Mme de Clèves is not listening to her, she takes offense : " Mme la Dauphine noticed that she was not listening to her and asked her aloud what she was looking at " (p. 302).

The offense is all the greater /// sensitive that the stage indication " tout haut " implies that the dauphine was doing Mme de Clèves the honor of a low-voiced conversation, no longer general, but particular.

.Here begins the portrait scene[18] : the discursive logic, the content of the dauphine's conversation, becomes unintelligible. It's no longer a question of listening, but of looking. The transition from the conversation with the dauphine to the exchange of glances with M. de Nemours (" he met Mme de Clèves' eyes, which were still fixed on him ") transgresses propriety. Mme de Clèves tumbles into the forbidden and, in so doing, makes a scene.

The scene is established by a shift in restricted space, from the conventional place of worldly conversation, the bed, to the transgressive place of theft, the table where M. de Nemours steals the portrait. The confined space of the scene is depicted from Mme de Clèves' point of view. The princess breaks in to watch the theft of the portrait: materially, her gaze is obstructed by the bed's curtains; symbolically, it is forbidden by the obligation she is under to listen deferentially to what the queen dauphine is saying to her:

.Mme de Clèves saw through one of the curtains, which was only half closed, M. de Nemours, his back against the table, which was at the foot of the bed, and she saw that, without turning her head, he was deftly taking something from that table. " (P. 302.)

M. de Nemours doesn't look at what he's taking. To better conceal his larceny, he turns his back on what he takes. Nor can Mme de Clèves see beyond the bed to the portrait on the table. The object that crystallizes the attention, desire and fear of both protagonists remains invisible, vaguely indeterminate. We find here one of the essential characteristics of the scenic object, which in the pre-scenic economy of the medieval tale, designated the vague of the marvel, before its decomposition into the vague space of the stage. The scenic object remains vague because it is not part of the screen device that constitutes the gaze that cuts across the stage. Placed as close as possible to the screen, i.e. to the bar that materializes the constitutive failure of the gaze, the scenic object escapes the geometrical order of the stage and opens up its scopic dimension : it is not looked at, but desired it is not visible, but visual it escapes, but fascinates.

The Duke of Nemours seizing the portrait performs in a very old tradition, in the manner of Perceval taking his ring from the damsel in the tent. But this performance is not simply parodied in flight. The portrait has a flaw: it's about mending " something " to Mme de Clèves' hairstyle. To do this, the painter removes the portrait from its box and then, having repaired this flaw, fails to put the miniature back in its case.

.The image is literally dislocated : the whole scene, even before the theft, says that the portrait is not to s aplace. The painter's action prefigures Nemours' theft, and the image's flaw already indicates that something else in this story is mismatched. The scene is certainly a transgression, but to a certain extent, to use the term /// In the words of Hamlet, she " rejoins " what was " déjointé "[19] ; in other words, it accomplishes the conjunction that, in the medieval tale, makes work, turns the failure of the marvel into the closure of the device[20].

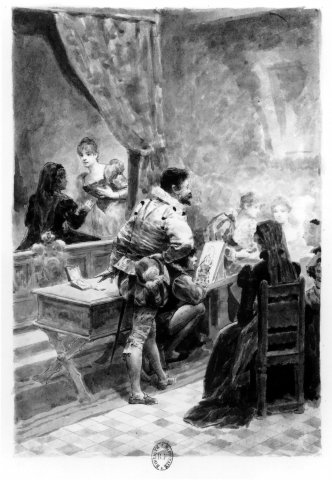

Figure 6 : Lamothe's preparatory drawing for an engraving for La Princesse de Clèves. The drawing is on page 34 of the preparatory album, Bnf Rés. Z Audéoud 64. Mme de Clèves in conversation with the dauphine glimpses Nemours from the background stealing the portrait laid in a case on the table, while he pretends to watch the painter at work. The screen is marked by the curtain, by the wooden panel of the bed and by the dauphine, whose silhouette, her back in shadow, makes a stain.

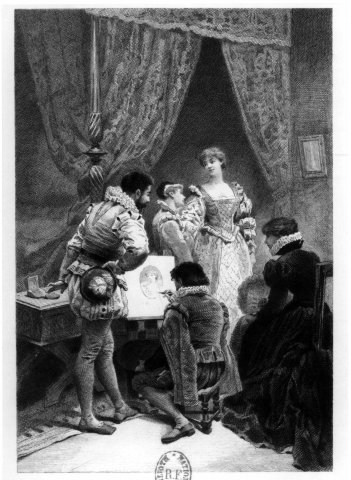

Figure 7 : Engraving after Lamothe's drawing for La Princesse de Clèves, Conquet, 1889 (in the same Audéoud album, p. 42). The arrangement of the figures has been altered so that the painter paints Mme de Clèves and not another lady. She then appears in the triangle of the open bed curtain, in the manner of the Virgins of the Tabernacle. (Compare also fig. 2 in chapter II.) Lamothe may moreover have been inspired by or instinctively rediscovered the device of Saint Luke painting the Virgin.

The characters encounter, through the scenic device, the enjoyment that is forbidden to them : Mme de Clèves " was quite at ease to grant him a favor that she could do to him without him even knowing that she was doing it to him " M. de Nemours could not " sustain in public the joy of having a portrait of Mme de Clèves. He felt all that passion can make one feel most pleasant. "

The scenic object is struck by the defect, the dislocation, because it is that by which a more essential defect is staged : through the portrait, the stage defaults propriety and operates the detour necessary for the fulfillment of jouissance. Like M; de Clèves barred by her hands during the confession, the portrait, with its connection to the hairstyle and the loss of its box, constitutes a barred image and, hence, the semiotic bar constitutive of the image.

.Finally, the climactic moment of the scene is that of the meeting of glances. At the beginning of the scene, the Duc de Nemours turns his back to Mme de Clèves. Communication through the gaze is accomplished by the duke's turning.

Turning around, he is surprised, and this surprise precipitates the two protagonists into transgression : Nemours declares by his gesture a passion that Mme de Clèves by her silence accepts. Reversal is here the dynamic principle of the scene: reversal of the characters; reversal of the situation, which places Nemours, present in Mme de Clèves' home as it were by hook or by crook, at the center of the scene; reversal of decorum. We have seen that this reversal, as early as Brunelleschi's experience, was constitutive of scenic devices based on the spatialization of performance.

But until then, it had only been a secondary feature of the stage. In Richardson and Diderot, it was to be exacerbated to the point of placing the principle of revolt at the heart of the scenic device.

Conclusion

The effectiveness of the stage /// lies in the fact that the double constraint imposed by history (the demands of desire, and the face-to-face confrontation with the forbidden) is reflected in the layout of the premises. The classic system of decorum dictates that the jouissance at stake here - the jouissance that M. de Clèves did not provide for his wife - must be concealed. The Duc de Nemours represents the unspoken jouissance that is missing: like her, he is there behind the scenes, but invisible and condemned to absence. Nemours is not an alternative to desire; he is an irreparable flaw. The screen of the scene is the cut that replaces the "thing" of the fairy tale, still present in the portrait scene, but definitively absent in the confession scene: from now on, there will be nothing left to obtain, other than a brutal confrontation with the truth of jouissance, irremediably emancipated as lack, absence, defect. The screen, at the very moment when it forcefully reaffirms the demands of the law and the foundations of the symbolic institution (the bienéances), indicates the dimension of the real as an unrepresentable limit. Jouissance thus manifests itself both as a (symbolic) prohibition and as a (real) defect: the real is the unnameable reverse side of the classical screen; it is the work in the real of the silence of the signified, the silence that ultimately threatens the classical device of the stage with radical deconstruction.

.

[1] Note that here the word classical does not refer to the classical era, the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but to what is taught in the classroom. In school, the novel is explained on the basis of this nineteenth-century model, which therefore constitutes the classical model.

[2] Here we take up G. Genette's analyses in " Vraisemblance et motivation ", Figures II, pp. 71-99.

[3] This contradiction of performance and code could already be found in Chrétien de Troyes, in the episode of Méliant de Lis. See chap. I, p. 51.

[4] Thomas Pavel, L'Art de l'éloignement. Essai sur l'imagination classique, Gallimard, Folio essais, 1996.

[5] " And above all what I find in it is a perfect imitation of the world and the Court, and the way we live in it. There is nothing romantic and guised " (Mme de Lafayette to Lescheraine, secretary to the Duchess of Savoy, April 23, 1678).

[6] Roland Barthes, Sur Racine, " La chambre ", Club Français du Livre, 1960, Points-Seuil, pp. 9-14.

[7] On literature as the practice of the indirect, see R. Barthes, Essais critiques, 1963 Preface, Points-Seuil.

[8] The confession scene is often evoked in the rest of the novel, but never designated as a scene. We speak of " this adventure " (p. 338), of " a story " (p. 345) ; " judge if this adventure is not his " (p. 346) ; " the adventure of one of my friends " ; " mingle with this adventure " " this adventure cannot be true " (p. 347) ; " this adventure is known " (p. 348). Finally, Mme de Clèves speaks of procédé : " un procédé aussi extraordinaire que le mien " (p. 362).

[9] /// " Coulommiers, which was a beautiful house a day's drive from Paris " (above, p. 109).

[10] The motif of the lover falsely lost in the forest to find his Lady is inherited from medieval literature, where it constitutes one of the possible declensions of the " adventure ". For example, in Heinrich of Freiberg's Second Continuation of Gottfried of Strasbourg's Tristan and Isolde (13th century), Gawan (Gauvain) devises a stratagem to bring Tristan to King Marke's wife Isolde, despite the latter's prohibition. He proposes to his king Artus (Arthur) that Tristan participate in a deer hunt in the forest that separates Artus' kingdom from Marke's. The master hunters are given the task of hunting Tristan. The master vintners are charged with leading King Artus' party astray near Tintajol (Tintagel), Marke's castle, so that at nightfall, too far from his own castle, Artus is forced to ask Marke for hospitality. Gawan obtains safe-conduct from Marke for Artus's entire party: " if anyone accompanies him from whom you have withdrawn your favor, you must also grant him your protection. " (Tristan and Yseut, translation of this text by Danielle Buschinger and Wolfgang Spiewok, Gallimard, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, p. 723.) In the medieval story, where the narrative thread plays a fundamental role, chance is entirely controlled by Gawan's cunning. The banquet that follows the hunters' arrival in Tintajol brings Tristan face to face with Isolde. An intense interplay of glances is established: " the queen's gaze was double : there was the gaze of the heart and the gaze of the eyes ! " (P. 724.) The real gaze is the gaze of the heart stealthily worn by Isolde on Tristan, while the gazes on Marke were hypocritical. Admittedly, the opposition of the two gazes sets up the screen device but nothing in the representation of space relays it the truth of this episode is invisible. Marke responds to Gawan's stratagem to bring Tristan to Isolde with the stratagem of bloody scythes. See chap. I, p. 47.

[11] Mme de Lafayette had already used this device at the beginning of La Princesse de Montpensier (1662). The inaugural scene, which brings the two lovers together, occurs only because the Duc d'Anjou and the Duc de Guise, out hunting, have strayed into the forest not far from Champigny, the equivalent of Coulommiers in La Princesse de Clèves. They then see the marvelous barque where Mlle de Montpensier makes her dazzling appearance pass them on the river. Crossing the river will constitute the transgression : in the medieval tale, it's a matter of crossing the ford here, the river is no longer a performance to be accomplished, but a picture to be looked at.

In La Princesse de Montpensier, Mme de Lafayette underlines the artifice of the device by calling the adventure a novel : " cette aventure [...] leur parut une chose de roman " (p. 10) ; " ce commancement de roman ne serait pas sans suite " (p. 12). The characters suspect a ruse on the part of the Duc de Guise, in the manner of Gauvain's ruse (see previous note) : " some said to the Duc de Guise that he had led them astray on purpose to make them see this beautiful person ". The story of rouerie is a pre-stage device, taken over by the narrative. The objectification of rouerie as a spatial device shifts the text into the stage, where discursive logic is challenged. Mme de Lafayette doesn't go quite that far in La Princesse de Montpensier.

[12] The road goes to the château, the duke's desire goes to the château's inhabitant. The road designates the duke's desire, which remains unexpressed (" without making any reflection and without /// to know what his purpose was "). The geometrical ending (the castle at the end of the road) and the symbolic ending (Mme de Clèves object of desire) of the story overlap and metaphorize each other.

.[13] The word pavilion is not insignificant here. In Old French, it refers to the tent, i.e. the skènè. See chap.I, fig. 10 and chap. II, fig. 2.

[14] The motif of the amorous balcony is not new. In the Roland furieux, Ariosto uses it for the episode of Renaud and Guinevere. Renaud, sent by Charlemagne to England to ask for reinforcements, learns that Guinevere, daughter of the King of Scotland, is condemned to death for having been seen, at midnight, luring her lover to her on a balcony (trarr'un suo amante a sé sopra un verrone, IV, 58). But Dalinde, Guinevere's maid, reveals the trap: Guinevere loved Ariodant, but was loved by Polinesse. Out of jealousy, Polinesse seduced Dalinde, whom he used to join by a rope ladder on this balcony. He asks her to meet him on the balcony one evening, dressed and coiffed as Guinevere (V, 26). At the same time, he insinuates to Ariodant that he is Guinevere's lover. To prove it, he advises him to come and watch what's going on on the balcony in the evening. Ariodant hides in the empty house opposite the secret balcony (V, 46) and sees Polinesse in the arms of the false Guinevere (Dalinde, in reality). In despair, he tries to commit suicide and disappears. Finally, thanks to Dalinde's revelations, the perfidious man is unmasked and Ariodant marries Guinevere.

What Italo Calvino calls " the balcony scene " (Roland furieux, GF, p. 62, p. 71) is, like the episode of the rigged hunt in the Continuation of Freiberg's Tristan, a tale of cunning rather than a scene it's the narration that sets up the device and it's Dalinde's word that reveals the truth meaning is deceived by the image and the mise en espace produces only illusion. Here, Mme de Lafayette radically reverses the motif: the spectator is still the jealous lover, but he is on the balcony, while the couple, also a false couple, is below. This geometrical reversal is accompanied by a symbolic reversal it is the truth of the scene, not the illusion of trickery, that Nemours' gaze receives.

[15] See chap. II, 1ère partie.

[16] See chap. I, note 18 and chap. IV, fig. 2.

[17] The moment of exchange of glances is the moment of superimposition of the two scopic cones, the cone of the gaze and the cone of the painting.

[18] In fact, the establishment of an iconic logic in the text has been long prepared : in the previous episode, the queen dauphine told the story of Anne Boulen, a heroic and exemplary story, the quintessence of discourse. Here, she makes small portraits, i.e. images, and miniature images, unrelated to the grand genre of historical scenes. We move from the public space, where the history of England unfolds, to an almost private space, where the bonds, the affinities between people are forged.

[19] " The time is out of joint. O cursed spite, / That ever I was born to set it right ! ", Time is out of joint. O cursed spite, / That ever I was born to set it right ! (Hamlet, I, 5, Hamlet's words after his father's specter appears to him /// ordered to swear vengeance; trans. Y. Bonnefoy). See also J. Derrida's commentary in Spectres de Marx, Galilée, 1993, chap. I.

[20] See chap. I, note 19.

///Fiction, illustration, peinture

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Fiction, illustration, peinture

La scène de roman

La scène de roman : introduction

Renaud dans le jardin d’Armide

Rastignac chez Mme de Restaud

Gilberte derrière les aubépines

La poignée de porte de tante Berthe

La double aporie du topos

Illustrer la fiction

Molière, une parole débordée

Marillier, l’appel du mièvre

On n'y voit rien

Illustrations de l'utopie au XVIIIe siècle

Le temps des images

Du conte au roman graphique

Déconstruire l’illustration

Régimes de la représentation dans la gravure d’illustration classique

Penser la fiction depuis la peinture

Une sémiologie du décalage : Loth à la scène

Introduction à la scène comme dispositif : Paolo et Francesca

La main tendue, le regard démasqué

De Silène molesté à la chair blanche des nymphes

Chambres de la représentation

L'intimité de Gertrude

Brutalités invisibles

Parodie et pastiche de Poe et de Conan Doyle dans Le Mystère de la chambre jaune de Gaston Leroux

Le dispositif de la chambre double dans Les Démons de Dostoïevski

Scène pour voir et chambre des brutalités

La Princesse de Clèves

L’invention de la scène dans le roman français

La canne des Indes

L'aveu

La princesse, la religieuse et l'idiot

Richardson

Entre scandale et leurre

Introduction aux Lettres angloises, ou histoire de miss Clarisse Harlove, par Samuel Richardson