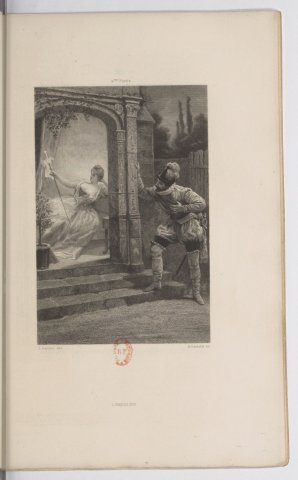

La canne des Indes. Engraving by Jules-Arsène Garnier after Alphonse Lamotte. La Princesse de Clèves, Paris, Conquet, 1889

The text to explain

Mme de Clèves is surprised at night in her pavilion in Coulommiers.

We'll study the text from :

" M. de Clèves did not doubt the subject of this journey ; but he resolved to clarify his wife's conduct and not remain in a cruel uncertainty. " (P. 142.)

until :

" It was a long time before she could bring herself to leave a place from which she thought this prince might be so near, and it was almost daylight when she returned to the castle. " (P. 145.)

Situation of the text

Mme de Clèves intends to remain faithful to her husband and fight the passion she feels for the Duc de Nemours. To this end, she has retreated to the countryside, to her château in Coulommiers, to avoid any encounter with M. de Nemours. However, de Nemours learns from Mme de Martigues, who has just returned from Coulommiers, that Mme de Clèves likes to walk alone at night in the hunting lodge she owns on the edge of the château grounds and the forest. Nemours knows this pavilion: it's where he overheard the Princesse de Cleves confess to her husband. Madly in love, he decides to travel secretly to Coulommiers " he thought it was not impossible that he could see Mme de Clèves there without being seen by anyone but her " (p. 142). But M. de Clèves, who is present at Madame de Martigues' interview, guesses at the thoughts of M. de Nemours, whom he suspects of being his wife's lover.

.

Text reading

Text outline

This is the second time M. de Nemours has visited Coulommiers. As on the occasion of Mme de Clèves' confession, the scene that crowns this trip is carefully prepared by the narrative, so that the parts of the text constitute the stages of this preparation of the scene, and then the scene itself.

In the first stage, Mme de La Fayette describes the journeys of the characters converging on the hunting lodge at Coulommiers. Here the geometrical dimension of the scene is prepared. This first part runs from " M. de Clèves did not doubt the subject of this journey " to " he easily recognized M. de Nemours ".

Once the characters are in position, the narrative sets up the system of glances and the picture given to be seen. Here the scopic dimension of the scene is prepared : the gentleman watches M. de Nemours look at Mme de Clèves alone in the pavilion. This second part goes from " He saw him go round the garden " to " what has never been tasted nor imagined by any other lover ".

Then M. de Nemours moves on to the action : this is the scene proper. The narrative dilates to the extreme, while time tightens (" the moments... were precious "). The representation of the l'instant prégnant, that moment which condenses preparatory reflection, the visual test of face-to-face and escape, constitutes the third part, which runs from " Ce prince était aussi tellement hors de lui-même " to " il était quasi jour quand elle revint au château ".

Movement and problematics

The /// The text opens with M. de Clèves (" M. de Clèves did not doubt the subject of this journey ") and closes with Mme de Clèves (" it was almost daylight when she returned to the château "). M. de Clèves formulates a request (is my wife faithful ?) to which his wife responds (by rejecting any contact, even visual, with M. de Nemours). On the strict discursive level of the narrative, things are simple.

.

However, communication between the characters is going to be blurred by another, visual logic, which parasitizes the discourse. M. de Clèves doesn't question, can't question Mme de Clèves directly. He lets M. de Nemours go and sends a spy after him: the indirection, i.e. the detour taken by the communication, is therefore twofold. The gentleman, Nemours and the princess do not exchange the slightest word with each other all information is conveyed through the eyes. . Even when the gentleman returns to M. de Clèves (p. 149), the exchange is purely visual :

" As soon as he saw him, he judged, by his face and his silence, that he had only unfortunate things to tell him. He remained for some time seized with affliction, his head bowed without being able to speak at last he beckoned to him with his hand to withdraw " (p. 149).

But do looks only convey information ? The result in any case is a catastrophe : M. de Clèves can only draw the opposite conclusion from this adventure from what, discursively, the narrative has demonstrated to the reader. Visually, the scene condemns Mme de Clèves, while discursively, the narrative has exonerated her. The problematic of the text lies in this paradox.

The gentleman, visual clutch of the scene

Besides this overall contradiction of the two logics of representation (discursive and visual), we witness a gradual shift from one to the other. We begin in reasoning and speech; we end in vision and the haunting of vision. The logic of the discourse is based on linearity as a result, a kind of equivalence is established between the journey, the itinerary of the characters and the development of their reflection and discourse.

.

More precisely, the fiction translates the development of discourse into the characters' journey : M. de Clèves first meditates (" M. de Clèves ne douta point " " il résolut de s'éclaircir " " il eut envie de " " craignant que " " il résolut de se fier "). The meditation leads to a speech (" il lui conta " ; " il lui dit " ; " et lui ordonné "), and the speech to a command. It's all about travel. Symptomatically, the command to travel leads to a negative formulation:

He said " " and commanded ".

" He told her what Mme de Clèves' virtue had been up to then, and ordered her to set off in the footsteps of M. de Nemours, to observe him exactly, to see if he would not go to Coulommiers and enter the garden at night. " (Pp. 142-143.)

" S'il n'irait point ", " s'il n'entrerait point " translates M. de Clèves' fear through the negation of the feared actions. The negation is thus initially justified, punctually, by the expression of the speaker's apprehension. But structurally, it indicates something else it's a matter of observing M. de Nemours, of seeing : we thus switch from the discursive to the visual, from which everything is reversed he would go becomes if he would not go he would enter becomes if he would not enter. This is already announcing that seeing expresses the negation of saying, that Mme de Clèves will emerge disfigured.

The first paragraph, centered on M. de Clèves, is answered by the second paragraph, centered on the gentleman ; to the expression of the master's speech, the execution of the character's journey. This journey takes place without a hitch. In La Princesse de Clèves, the space is not /// The obstacles are not contingent, but symbolic and logical. The effect of truth produced by M. de Clèves' reflections has led to a system of indirection : he will not go himself, " fearing that his departure would appear extraordinary ", i.e. implausible, but will send a gentleman. Indirect is the hallmark of verisimilitude.

In real life, on the other hand, the gentleman's mission encounters no obstacles. It is carried out perfectly, i.e. logically (he " carried it out with all imaginable exactitude "), without any of the little oversights, bad moods, vexations, jealousies, all those human irregularities that, in the real world, seize up or distort, however slightly, any strategic machine. The gentleman doesn't even need to follow Nemours exactly, whose route is also like clockwork. He can anticipate this route without worry, and immediately go and stand in the forest of Coulommiers " at the place where he judged that M. de Nemours could pass " : this could is a should, for a necessary route, ordered by the logic of discourse alone.

From the forest, the gentleman watches the Duc de Nemours enter the garden at Coulommiers. The garden scene, bordered by the vague space of the forest, is thus indicated to us by his gaze, which transports M. de Clèves' gaze there and constitutes the visual clutch of the scene. The gentleman remains outside the scene, but still belongs to the fiction in representation, he designates the off-stage from which the gaze points towards the scene and misrecognizes it, misunderstands its content. This gaze, which fails to see the show, will be opposed by the eye of M. de Nemours, which will not miss a crumb !

The gentleman doesn't actually see M. de Nemours arrive. Rather, we witness a sudden appearance. At the edge of the forest, from the shadows and below the visible, Nemours takes on consistency as a figure :

" As soon as night had come, he heard walking, and although it was dark, he easily recognized M. de Nemours. " (P. 143.)

The palisade and the window, screens of representation

The Duc de Nemours then climbs the palisades, two rows of which he must cross to enter the garden proper :

" The palisades were very high, and there were still some behind, to prevent one from entering ; so that it was rather difficult to make a passage. " (Ibid.)

Everything suggests that the gentleman stays behind. On the second night, which will result in a repeat of this scene, Mme de La Fayette makes it clear that he doesn't go beyond :

" M. de Clèves' gentleman, who had disguised himself in order to be less noticed, followed him to the place where he had followed him the evening before and saw him enter the same garden. " (P. 147.)

" up to the place ", that is, he doesn't follow Nemours further, doesn't climb the palisades. The palisades are high. How then can we claim that " M. de Clèves' gentleman had always observed " (p. 149) ? Precisely because the gentleman sees nothing of what actually happened in the garden, he can only testify to what Nemours entered, not to Mme de Clèves' virtuous defense and innocence. The palisades screen the knowledge of the scene, which the gentleman looks at, but does not see.

We see the stage set up, in which these palisades play an essential role. If this first screen obscures the view, a second, very different screen immediately appears behind it, as the narrative is now taken over by the point of view of the Duc de Nemours (and no longer of the gentleman) these are the French windows of the cabinet where Mme de /// Cleves, in the hunting lodge.

" He saw many lights in the cabinet ; all the windows were open and, creeping along the palisades, he approached it with a disturbance and emotion that it is easy to imagine.He ranged himself behind one of the windows, which served as a door, to see what Mme de Clèves was doing. " (Ibid.)

M. de Nemours is the eye of the scene : he feeds on and enjoys its light, its brilliance, the object of his desire it contains. Nemours behind the window sees without being seen, taking advantage of a remarkable property of glass the window faithfully lets you see what's in the light from the shadows, but becomes almost opaque from the light when you look towards the shadows. At night, the one-way transparency of the window is reversed: Nemours sees everything from the outside, while Mme de Clèves can't see him from a few meters away. The object of the scene, the Lady of the Pavilion, is blind.

La Dame du pavillon

Nemours thus surprises Mme de Clèves alone in her study and away from her husband. Mme de La Fayette here exploits a topos that goes back to medieval literature. At the start of Chrétien de Troyes' Perceval , Perceval, who has just left his mother to embark on a career as a knight, was already encountering a damsel asleep in her tent in the clearing of a forest in the twelfth century.All the narrative elements of our scene were already present in Chrétien's tale, and first of all the journey through the forest night and Perceval's emergence into the light of the event :

.

" Ainz l'emporte a grande aleüre

Parmi la grant forest oscure

Et chevauche des lo matin

Tant que li jorz vint a declin.

En la foret cele nuit jut

Tant que li clerz jorz aparut1. " (Vv. 593-598.)

Opposite Perceval stands, in the locus amoenus of a clearing and its spring, a marvelous tent in which a sleeping damsel rests. Chrétien emphasizes the brilliance of the tent, whose golden braids and gilded eagle project their luminous rays over the whole clearing :

" Et reluisoient tuit li pré

De l'anluminement dou tré2. " (611-612.)

Madame de Clèves' garden and the profusion of light spilling from her brilliantly lit cabinet reproduce, artificially and in the night, the medieval brilliance of the wonder Perceval is confronted with.

Perceval, like Nemours, first enjoys the tableau formed by the damsel asleep in his tent, unknowingly delivered to his voyeuristic eye :

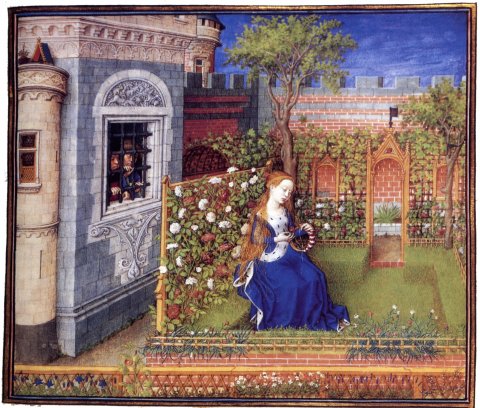

Perceval snatches his ring from the damsel in the tent. Manuscript of Perceval, folio 5v°, Montpellier, Bibliothèque de la Faculté de Médecine, late 13th century.

" Lors vint au tref, so trove overt,

A mi lo tref un lit covert

D'une coute de paille, et voit :

El lit une dame gissoit,

Qui estoit iqui andormie3. " (629-633.)

It is indeed grosso modo the same tableau, but Chrétien doesn't dwell on it : there is no scene, strictly speaking, in the medieval novel.Perceval enters the tent and awakens the damsel, just as Nemours enters the cabinet and surprises Mme de Clèves. As Mme de Clèves flees, the damsel pushes away /// Perceval as she can, and for the same reasons : Mme de Clèves depends on a husband, the demoiselle on a friend, who, even if absent, symbolically interpose themselves between the chevalier (Perceval, Nemours) and the Dame.

" Fui que mes amis ne te truise,

Que s'il te troeve, tu ies morz4. " (662-663.)

But the damage is done, despite the Lady's virtue : Perceval by stealing her ring (683), Nemours by making himself seen by the gentleman, give, against the unprovable reality of the facts, the visible evidence of the wives' adultery. The proofs are of the same paradoxical nature: located in the visual order, they are not, however, strictly speaking visible, as the ring is missing from the damsel (760) and the gentleman, behind the palisades, has seen nothing.

Why does the icon of the damsel in the tent condense all desires ? Why must a woman's desire be embodied, represented, so to speak, necessarily in this icon ? Perceval, in his false naïveté as a rough-hewn Welshman, as played out by Chrétien de Troyes, provides us with an element of the answer :

.

" Li vallez vers lo tref ala

Et dit ainz qu'il parvenist la :

"Dex, or voi je vostre maison !

Or feroie je desraison

Se aorer ne vos aloie.

Voir dit ma mere tote voie,

Qui me dist que ja ne trovasse

Moutier ou aorer n'alasse

Lo Criator an cui je croi5." " (617-625)

Perceval mixes up (or pretends to mix up) his mother's prescriptions and, throughout this episode, turns her sound advice into disasters. But the absurdity of Perceval's conduct, which misuses chivalric decorum in good (or bad) faith, makes sense itself.

Perceval mistakes the damsel's tent for God's house, and confuses the sacred worship of God's image in a church with the rape of the damsel in her tent. The amorous adventure parodies prayer in the church : but this parody does not constitute a discourse against the symbolic institution it merges with it and turns it inside out to constitute the novelistic fiction.

Through this reversal of the symbolic foundation of the fictional device, the damsel in her tent is unveiled as the Virgin of the tabernacle, the ultimate object of all adoration : it was precisely in the twelfth century that the cult of the Virgin took off in full swing. The Lady of the Pavilion is the icon above all others projected by amorous desire, because she confers on desire that essential symbolic foundation, which we saw, in connection with Paolo and Francesca, that Ingres made the most of.

.

The tabernacle is the ancestor of the scene6. The tabernacle tent delimits the sacred space, which contrasts with the profane space outside. The interplay of sacred and profane becomes, in the secularized stage set-up, an interplay of restricted space and vague space. The interior of the Jewish tabernacle is divided by a curtain that separates the Holy, accessible to the faithful, from the Holy of Holies, reserved for priests only. In its Christian translation, where the tabernacle no longer contains the Ark of the Covenant, but the image of the Virgin, this interior separation is replaced by a damask hanging stretched behind the Virgin, placed in a Holy of Holies now visible and accessible.

.

Perceval can access the Lady, but must not go beyond the grip of the ring. Even when open and exposed, the fictional tabernacle has a virginal reserve : the tabernacle's curtain, the integrity of the Lady's body are the ancestors of the representation's screen.

The Baroque grotto

It would be quite bold, however, to make the cane scene in La Princesse de Clèves the /// rewriting the episode of the stolen ring in Perceval. Mme de La Fayette probably never heard of Chrétien de Troyes, who was forgotten at least until the nineteenth century. However, a continuous novelistic tradition, from the great Gothic prose romances to the Renaissance epics, then to the Pastoral and Baroque romances, conveyed the fictional material to her. The first novel scenes were fabricated from these materials, sometimes forgetting their origins until they became unrecognizable.

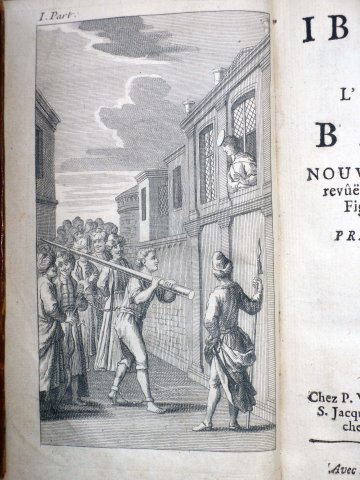

Justinian pardoned by Asteria, engraving for Ibrahim, ou l'illustre Bassa, Paris, Witte, 1723, vol. 1

The wild and wonderful place of the amorous encounter, for example, appears vividly in Ibrahim, ou l'illustre Bassa, a novel published from 1641 to 1644, under the name of Georges de Scudéry, but sometimes attributed to his sister Madeleine. The hero, Justinian, lord of Genoa, was captured at sea by the Turks and, under the name of Ibrahim, became in Constantinople the grand vizier of Sultan Soliman. Although pampered by the Sultan, who treats him as a friend, Ibrahim remains madly in love with Isabelle, whom he left behind in Italy. He tells Soliman about his encounter with Isabelle:

Ibrahim's love affair with Isabelle is over.

" It happened that one of my dearest friends asked me to go and hear a concert of lutes & de voix qui se faisoit le lendemain à une maison qu'il avoit en ce séjour delicieux7 ; & as music has always touched me appreciably, I did not fail to go. It is certain, however, that I went with a secret melancholy, which no doubt warned me of the misfortune that was to befall me there : but I was unable to make the most of this involuntary movement, the cause of which was unknown to me. Nevertheless, I let myself be charmed by the sweetness of the harmony: it seemed to me that it had dissipated my sorrow and awakened my joy. This pleasant transport was the last moment before my loss ; for, Lord8, as the sun [was] already low enough to be no longer inconvenient, neither by its raions, nor by its heat, the master of the house told me that before going down to the garden he wanted me to hear a wonderful echo, which he had found a few days ago & that one of his neighbors had given him without thinking about it, by having a cave built opposite the windows of his study & dug into the mountain in the shape of half a moon ; which collected & reflected the voice so admirably that the seventh repetition that this echo made was perfectly distinguishable. As soon as this speech was over, I entered the cabinet alone, ahead of the company, determined to try the echo first. But, Lord, I had not so soon opened the window that, far from forcing the echo to answer me, I myself lost the use of my voice by the rapture with which I was seized when I saw the most beautiful person nature had ever made. She was leaning on a balustrade of jasper & porphyry, which formed a quarter in the middle of which we saw a gushing fountain, where four nimphs of white marble seemed to be playing while bathing : for by a marvelous artifice there leaves from their hands an abundance of water which wets them, & which makes it seem as if they were throwing it at each other ; which causes a very-pleasant noise. Moreover, if I had seen elsewhere some fountain approaching this one, I would not have been careful to describe it ; for, Lord, I was so surprised by the charms of this beautiful stranger, that I had eyes only for her. I changed /// color twenty times in one moment, & hiding myself a little for fear of being apperçu, I considered her with all the attention that could have a man, who from admiration had already passed to love.

As I was in this state all the company arrived, & testified to me that she had regretted that I had left her so soon, because it had been made a dispute. As I was in this state, the whole company arrived, and told me they were sorry I had left them so soon, because there had been a dispute about the nature of the echo, which would have given me great pleasure. After listening to this discourse without answering, I asked if someone could not teach me the name of this beautiful one who dreams at the edge of the fountain I saw in the middle of this garden ? Saying this I gently opened the window I had half-closed, & begging them not to make any noise I showed them this prodigy of beauty. I had not so soon finished speaking, that by a [68] hidden connoissance which anticipated their response, I felt something inside me which told me that it was Isabelle9. No sooner had this thought stirred up trouble in my soul, than one of my friends spoke up and confirmed this truth, asking me if it was possible that I didn't know my enemy? What," I said, interrupting him, "the one I see is Rodolphe's daughter! I said this so loudly, that I made her turn her head to face the direction we were facing: so that, having seen us, she lowered her veil and started walking to join two women strolling down an alley. It wasn't long before I forgot all about propriety and left a place that had been so fatal to me, making me see in one person the object of my hatred and love. But finally, the spite of being seen with so much weakness, made me resolve to try and hide it. So I told the man who had spoken to me that I was delighted to have such a beautiful enemy, and that although she had weapons that would easily make her victorious over all those she wished to subjugate, I was nevertheless generous enough not to refuse to fight someone who could be [69] defeated without shame. After that, they amused themselves by looking for all the beauties of the echo; those of the company whose voice was the worst and the hoarsest, did not fail to force this echo to answer them and reproach them for their fault by imitating them. For me, who didn't find it unpleasant in those days, it was impossible to sing, and whatever violence I did to myself, I could never remember an aria, although I knew quite a few10. "

Although entirely artificial, the grotto in which Isabelle appears to Justinian reproduces the locus amœnus of the tent in Perceval's clearing. Justinian accesses this grotto after a journey : he travels from Genoa to Arena, where he has been invited to a concert, and then from the concert to his friend's study, from which he discovers the marvelous grotto. The beautiful dreamer appears framed by the grotto, producing the seizure of the scopic effect (" the rapture I was seized with when I saw the most beautiful person nature had ever made " ; " I was so surprised11 at the charms of this beautiful stranger "). She makes tableau as what Justinian himself designates, in front of his friends who have joined him, as " cette belle qui révoit au bord de la fontaine que je voyois au milieu de ce jardin " : discourse here identifies the topos ; but Justinian's gaze orders place and object into a scenic device. The fountain and grotto delimit, in the vague space of the garden, the restricted area of the stage proper, while the window of Justinian's study, sometimes almost closed, sometimes open (" j'ouvris doucement la fenêtre que j'avais à moitié fermée "), assumes the function of the screen, manifesting the constitutive dissymmetry of /// visual exchange (looking without seeing / seeing without being seen), itself linked to what psychoanalysis designates as the schize of the eye and the gaze.

With the overkill of Baroque music and architecture (" a balustrade of jasper & porphire ", statues " of white marble " in the fountain endowed with " artifice merveilleux "), Scudéry here sets up the device of the classical stage, cobbled together from the medieval topos, which he denaturalizes and theatricalizes. Indeed, Justinian's vision of Isabelle follows an instrumental concert and precedes a parody of a vocal concert by Justinian's friends, trying out the marvellous echo returned by the cave : " After that they amused themselves by seeking out all the beauties of the echo those of the company whose voice was the worst & the hoarsest, did not let themselves be forced by this echo to answer them & to reproach them for their deficiency by imitating them. " Between the beautiful theatrical ritual and its discordant parody, the stage is the moment of reversal. If there's an echo, it's because the grotto itself has been " carved out of the mountain in the shape of a half moon " : it's the inverted form of a theater, of which Isabelle would be the spectator and Justinian and his cacophonist friends the actors.

The music that frames the scene finally contrasts the sound dimension of the show with its visual dimension, the seizure at the sight of Isabelle. This opposition prefigures the classic one between discursive logic, which prepares the scene, and visual logic, which turns it upside down and deconstructs it. While Justinian's friends try their best to sing discordant songs, Justinian remains mute, paralyzed by the scopic effect of the vision that surprised him. The scene stuns, and its suspended, condensed time blocks speech.

Finally, Justinian guesses in the belle he surprises abandoned to her reverie the heiress of the Grimaldi12, the rival family to his own in Genoa. Isabelle is a priori forbidden to him. The pleasure and effect of Isabelle's spectacle stems from the ban on her, just as Perceval is forbidden to see the maiden in the tent, and Nemours is forbidden to see Mme de Clèves in her cabinet.

In addition to the material barrier of the screen (the cabinet window), which geometrically bars the viewer's gaze, there is this symbolic ban, a distant memory of the sacred ban of the tabernacle which, inside, protected access to the Holy of Holies with a curtain.

The scenic reversal

Mme de La Fayette recovers all this material, prunes, condenses, simplifies : the fountain and its marble nymphs, the jasper and porphyry balustrade, the sublime concert under the lemon trees of a wealthy Genoese resort, all disappear. The complex face-to-face setting of the cabinet and grotto is replaced by Mme de Clèves' cabinet alone, with her own window acting as screen. This simplification is characteristic of the classical aesthetic, which is generally contrasted with the Baroque of the previous generation (a good thirty years separate Ibrahim, ou l'illustre Bassa from La Princesse de Clèves).

But we mustn't reduce these transformations to a passing effect of style and fashion. A profound mutation of representation is at work. In Ibrahim, ou l'illustre Bassa, the device remains somewhat vacant it allows us to introduce the heroine, Isabelle, to place the two lovers face to face we might even consider that it marks, very linearly, the beginning of their love. But it has no complex repercussions in terms of the plot, it doesn't trigger the narrative short-circuit characteristic of the scene : the witnesses to the face-to-face, Justinian's friends, will play no part in the rest of the story the grotto does reappear in the rest of the narrative, but the properties of the place, this extraordinary echo, are never exploited.

.

At Madame de La /// Fayette, the principle of economy of means forbids such gratuitous expenditure. Not only has Mme de Clèves' cabinet already been used for the novel's most important scene, the confession, but the scene with the cane from the Indies, spied on by M. de Clèves' gentleman, is destined to have spectacular repercussions on the plot, and precisely this short-circuit putting Mme de Clèves on trial in front of her husband, it nullifies the effect of the confession, disqualifies its sincerity and thus in a way turns the narrative against itself. The scene's visual effect doesn't simply embellish the narrative it seriously disrupts its unfolding it produces in it a reversal, a retour effect.

Tristan and Yseut at the fountain spied on by King Mark. Ivory case panel, 6 cm high, 1340-1350, Musée du Louvre

Here we touch on the scandalous dimension of the scene. If the controversy that followed the publication of La Princesse de Clèves, with the little pamphlet of Lettres à la Marquise *** sur La Princesse de Clèves by Valincour (1678) and, in response, the Conversations sur la critique de La Princesse de Clèves by Charnes (1679), were essentially aimed at confession, it is in fact all the scenes in the novel that, constitutively, derive their effectiveness from the scandal they produce. To make a scene is to make a scandal, and it's in this sense, moreover, that the word first appears in novels13.

But scandal is only one dimension (social, symbolic, narrative) of the scene's constitutive reversal. In the very layout of its locations, the scene constitutes a reversed space. In the confession scene, the Duc de Nemours, the lover, overheard Mme de Clèves' intimate dialogue with her husband, reversing a well-known romantic situation - that of the husband overhearing the lovers' conversation. It's King Marc spying on Tristan and Yseut hidden in a tree in the Morois forest, the opening sequence of Béroul's Tristan, repeated in Tristan en prose. It's also Nero spying on the dialogue between Britannicus and Junia hidden behind a curtain, in Racine's tragedy (1669). The scene solicits the topos romanesque, but diverts it, reverses it, parodies it.

In the scene we're concerned with here, we witness the same reversal. Nemours is here in the garden and, from outside, spies Mme de Clèves installed in her hunting lodge. Mme de La Fayette herself reverses the positions of the confession scene, set in the same locations, but where the characters no longer occupy the same positions : the object of the scene, given to be seen, moves from outside to inside, while the looking subject, the voyeur spectator, slides from inside to outside. The novelistic topos, of which we have given some examples with Perceval and with Ibrahim, consists in receiving the vision of the Lady installed in the setting of her tent, her grotto, in a garden that evokes the garden of the Virgins of the Annunciation, the hortus conclusus of mystical visions. In Boccaccio's Théséide (circa 1340), Palemon and Arcitas, when they surprise the beautiful Emilia, follower of the Queen of the Amazons, braiding a wreath of flowers and singing in Theseus' garden, are locked up squarely in a prison.

Al suon di quella voce graziosa

Arcita si levò, ch'era in prigione

allato allato al giardino amoroso,

sanza niente dire a Palemone,

e una finestretta disiosa

aprì per meglio udir quella canzone,

e per vedere ancor chi la cantasse,

tra' ferri il capo fuori alquanto trasse14.

Émilie in her garden, spied on by Palémon and Arcitas. Illumination by Barthélémy d'Eyck for La Théséide by Boccaccio, beginning of Book III. Circa 1460-1465, Vienna, Austrian National Library, codex M. S. 2617, fol. 53. Here, quite exceptionally, all the elements of the scenic device are already brought together, right down to the double screen of the prison bars and the rose trellis.

The lover is paralyzed by the beatific vision of his Lady in the garden. Without going as far as blatant parody, as Chrétien de Troyes does in Perceval, Mme de La Fayette reverses the situation : on the geometrical level (i.e. if we look at the layout of the characters in the locations), it's Mme de Clèves who is trapped, cornered in the hunting lodge's cabinet, offered as prey to the Duc de Nemours. Yet from a scopic point of view (i.e., if we consider the system of glances and the resulting emotional situation of the characters), Mme de La Fayette is very much in the tradition of romance: M. de Nemours is subjugated, paralyzed by the sublime tableau before him. The scene feeds on this contradiction between his geometrical position of mastery and his scopic subjection.

Mme de Clèves holding the Cane of India: a syncretic tableau

" It was hot, and she had nothing on her head and throat but her confusingly reattached hair. She was on a daybed, with a table in front of her, where there were several baskets full of ribbons she chose a few, and M. de Nemours noticed that they were the same colors he had worn at the tournament. He saw that she was making bows with them to a cane of the Indies, very extraordinary, which he had worn for some time and which he had given to his sister, from whom Mme de Clèves had taken it without pretending to recognize it as having been M. de Nemours' " (P. 143.)

The painting that subdues M. de Nemours is not a portrait of Mme de Clèves, one of those amorous coats of arms favored by Baroque poetry and romance, where the lilies, roses and coral of the parts of the face are enumerated. Rather than traits, Mme de La Fayette describes, or more accurately condenses topical situations.

The Lady is first seen, so to speak, naked, clothed only in her hair, lying down, as a sleeping woman would be. This is the Sleeping Beauty, whom painters sometimes depict simply as Sleeping Venus, more often as a nymph being spied on by a satyr, or as Jupiter and Antiope. La Belle endormie calls, suggests the presence of the voyeur spectator : the painting seen by Nemours programs his figuration as a satyr.

Jean François de Troy, Dame attaching a ribbon to a horseman's sword, 1734, oil on canvas, 81x64 cm, private collection

But Madame de Clèves is not asleep. This /// The first image, crossed out by " a table in front of her, where there were several baskets full of ribbons ", leads to a second, where ribbons are the pretext for a genre scene : the purchase, sorting and selection of ribbons constitute a new topical scene, totally unrelated to the previous one, but quite familiar at a time when, in the absence of zippers, ribbons constituted, much more than an accessory, a fundamental part of clothing. The eroticism of the ribbon is obvious it is used to tie garters it is offered by the Lady to the cavalier of her thoughts she then ties it herself to her sword, as can be seen in this painting by Jean-François de Troy :

Here again, then, the solitary painting of Mme de Clèves tying knots calls, program the presence of the Duc de Nemours. The ribbons are yellow and black, the colors worn by the duke at the tournament :

" M. de Nemours had yellow and black ; we searched in vain for the reason. Mme de Clèves had no trouble guessing it she remembered having said in front of him that she liked yellow, and that she was angry to be blonde, because she couldn't wear it. This prince thought he could appear with this color, without indiscretion, since, since Mme de Clèves didn't wear any, no one could suspect it was hers. " (P. 132)

If the baroque blazon of the Dame has been avoided, it's because Mme de La Fayette prefers it to the medieval blazon of the knight at the tournament. Yellow designates Mme de Clèves' color by default, in absentia, but nothing is said about black. Yet the black knight15 is Lancelot, who, in the famous tournament episode where he fought for Guinevere, appeared in black and faceless, also manifesting his identity by default. Discreetly, Mme de La Fayette identifies Nemours with Lancelot.

Mme de Clèves stole the Duc de Nemours' cane, just as Nemours had stolen her portrait ; she took it " without pretending to recognize it ", that is, without showing that she recognized it. The Indian cane, " quite extraordinary " is the scenic object on which all eyes focus. Tamed, manipulated and appropriated by the lover, it nonetheless refers to and designates the lover. After the Sleeping Beauty satyr and the black ribbon mixed with the yellow ribbon, the cane is a hollow representation of the voyeur placed at its edge, at the heart of the scene: grasping the woman he loves with his desiring eye, Nemours thus figures, through the succession, or superimposition, of these tableaux, himself in her. The painting gives and doesn't give to see it delivers the presence of the Other or, on the contrary, marks the absence of the Self. Faced with this painting, Nemours oscillates between eye and gaze, between enjoyment and disappointment, between vision and blindness.

This oscillation, this ambivalence of representation is finally confirmed when Mme de Clèves rises :

" After she had finished her work with a grace and gentleness that spread over her face the feelings she had in her heart, she took a torch and went away, close to a large table, opposite the seat of Metz, where the portrait of M. de Nemours ; she sat down and began to look at this portrait with an attention and reverie that passion alone can give. "

The brief evocation of this painting of the Siège de Metz was brought about from afar. From the very first pages of the novel, Mme de La Fayette, praising the military qualities of King Henri II, had mentioned it among his successes :

" He had won in person the battle of Renty Piedmont had been conquered the English had been driven out of France, and the Emperor Charles-Quint had seen his good fortune end before the city of Metz, which he had uselessly besieged with all the forces of the Empire and Spain. " /// (Pp. 25-26.)

Although the city had just been reconquered by France, the siege of Metz by Imperial troops from October 1552 to January 1553 was a resounding failure for Charles V. Bertrand de Salignac, the future French ambassador to Elizabeth I of England (1568-1575), wrote the diary, which Mme de La Fayette has certainly read16. From the very first pages, we learn that the Duc de Guise, entrusted with the defense of Metz by the king, found a welcoming committee there that is very familiar to us :

" De quoy estant advertiz M. le duc de Nemours, les seigneurs de Gounor, vidame de Chartres, de Martigues et autres seigneurs et capitaines qui estoyent dans la ville, sortirent au devant avec les compagnies de gens de cheval et de gens de pied, pour le recueillir en la sorte que sa grandeur et le lieu qu'il venoit tenir le requeroyent. " (B. de Salignac, Siège de Metz, 1553.)

In Salignac's account, the Duc de Nemours appears as a comrade-in-arms of the vidame de Chartres, whose several brilliant actions are reported. M. de Martigues is also mentioned: Mme de Martigues will play an important role in our novel. As for the painting of the Siège de Metz, it is no invention. At least a drawing17 by Antoine Caron, a master of the Fontainebleau school, the great French painting school of the mid-sixteenth century, still exists. It's impossible to know whether Mme de La Fayette ever saw this drawing, whose whereabouts in the 17th century are unknown. What is certain is that the novelist strongly suggests, at the time of Mme de Clèves' departure for Coulommiers, that the painting in fiction is a copy of a real commission :

" She went to Coulommiers ; and, on her way there, she took care to have large paintings carried there that she had had copied from originals that Mme de Valentinois had had made for her beautiful house at Anet18. All the remarkable events of the king's reign were depicted in these paintings. Among them was the siege of Metz, and all those who had distinguished themselves there were painted in strong likeness. M. de Nemours was one of them, and it was perhaps this that made Mme de Clèves want to have these paintings.

The painting of the siege of Metz thus plays an essential role in the overall economy of fiction in La Princesse de Clèves : destined to figure at the heart of a decisive scene in the novel, as the supreme degree of fictional elaboration (a painting seen by the heroine, herself looked at by the hero, himself spied on by a gentleman, himself commissioned by M. de Clèves...), Le Siège de Metz brings us back not only to the reality of History (a historical siege, a real painting), but to the place of the suture between reality and fiction, since it is in B. de Salignac's diary that we find the original nucleus of the characters staged by Mme de La Fayette.

Le Siège de Metz not only abymes the representation of the Canne des Indes scene by showing M. de Nemours looking at the theater of military operations, as in the scene in the novel Nemours looks at that other theater of operations which is the cabinet where Mme de Cèves dreams ; Le Siège de Metz at the same time cancels out the levels of mise en abyme and triggers the metalepse effect19. In this way, the self-reflexivity constitutive of the novel scene both underscores and abolishes the mimetic gap. By showing a picture within a picture, the scene reveals the machinery of representation; but by choosing the picture of the siege of Metz, which contains the secret of the novel's fictional fabrication and its articulation with the /// historical reality, Mme de La Fayette deconstructs this machinery.

Caught in a scarf: the moment of the scene

Until this point in the text where M. de Nemours surprises Mme de Clèves looking at her own portrait in the painting of the siege of Metz, however, we can consider that the scene proper has not yet taken place. The stage has been set, but the moment has not been set. Indeed, we can only truly and fully speak of a scene from the moment when the temporal condensation and, conversely, the narrative dilation that constitute the significant moment take place. Time then becomes sensitive, and the narrative becomes aware of its own temporality:

.

" One cannot express what M. de Nemours felt in this moment. To see in the middle of the night, in the most beautiful place in the world, a person he adored, to see her without her knowing he was seeing her, and to see her all occupied with things that had to do with him and the passion she was hiding from him, is what has never been tasted or imagined by any other lover.

This prince was also so out of himself that he remained motionless watching Mme de Clèves, without thinking that the moments were precious to him. "

During the entire second part of our text, the narrator's point of view was perfectly identified with the Duc de Nemours' point of view. Here, the two points of view are disassociated: Mme de La Fayette shows us Nemours as a voyeur, and the voyeuristic pleasure he experiences. She also gives us a sense of the passage of time, which on the other hand completely eludes Nemours absorbed in his contemplation.

This split is the consequence of the return effect characteristic of the scene : just as, geometrically, from the background of the painting, entirely inhabited by Mme de Clèves, Nemours, seized as a portrait, as an object of representation returns to Nemours subject looking, so, symbolically, Nemours' absorption, to the point of self-forgetfulness, precipitates the latter towards reflection and return on oneself. Nemours' recapture then triggers the event of the scene, which involves the destruction of the painting : Nemours enters the hunting lodge cabinet.

All the impossibilities of the situation immediately arise : propriety absolutely forbids Nemours to show himself to Mme de Clèves the seeing without being seen constitutive of the device cannot lead to an encounter and constitutes a narrative impasse :

" He found that there had been madness, not in coming to see Mme de Clèves without being seen, but in thinking of being seen "

Nemours is symbolically stuck : never will Mme de Clèves, who nevertheless looks at him in the painting of the siege of Mtez, agree to see him in the flesh he has put himself in the position of remaining invisible. If Mme de Clèves makes a tableau for the Duc de Nemours, brilliantly lit in the cabinet and framed by the glass of the French window, M. de Nemours makes a screen for Mme de Clèves, with whom all the rules of morality, society, religion forbid her to be face to face, alone and in the night.

.

The obstacle first manifests itself on the scopic plane, right from the start of the sequence we're studying here : the interplay of light and shadow means that Mme de Clèves can't see M. de Nemours, and immediately divides Nemours's seeing on one side, Mme de Clèves's looking on the other. But Nemours steps forward, enters the light in his turn, transgresses the invisible boundary that separates him from the object of his desire. Then, the scopic obstacle is superimposed by a symbolic obstacle : propriety forbids Mme de Clèves to see M. de Nemours. Finally, the material obstacle intervenes, confirming, on the geometrical plane, this prohibition :

" Driven nonetheless by the desire to talk to him, and reassured /// by the hopes that everything he had seen gave him, he took a few steps forward, but with so much trouble that a scarf he had caught in the window, so that he made a noise. Mme de Clèves turned her head, and, whether her mind was full of this prince, or whether he was in a place where the light was bright enough for her to distinguish him, she thought she recognized him, and without balancing or turning to the side where he was, she entered the place where her wives were. " (Pp. 144-145.)

The scarf in the seventeenth century was not worn around the neck but, like the scarf of our elected Republicans, slung over the shoulder and tied below the hip. When Nemours steps around the open French window to enter the study, his scarf gets caught in the French window's espagnolette. The obstacle, both physical and sonic, geometrically represents symbolic prohibition and scopic asymmetry. The screen of representation is made up of these three dimensions, geometrical, scopic and symbolic, here perfectly superimposed.

It is this superposition that produces, in the text, the effect of temporal concentration, the dramatic suspense characteristic of the pregnant moment. Stopped in his tracks, transfixed by the sound of the French window slamming shut behind him, dragged along by his scarf, Nemours appears motionless, suspended between the outside and the inside, the invisible and the visible, the voyeur before and the forbidden after. During this improbable suspension, this balance of Nemours arrested in flight, fixed as a figure, " Mme de Clèves turned her head " : time stops for him, but continues to unfold for her.

She turns toward him, but not completely, not until she meets his gaze. She doesn't go so far as to see him she senses him, anticipates him and, immediately, turns away, escapes the encounter. There is a scene here, and a scene in the full sense of the word, because of this irregular exercise of narrative temporality. Mme de La Fayette doesn't tell us about the Duc de Nemours' journey to Coulommiers. The équipée is merely the narrative means she uses to place her characters in a highly significant, regulated space; then, within that space, she triggers a micro-event (a scarf caught in a doorway) to which she gives extraordinary importance. A fleeting event in the real world, this micro-event expands extraordinarily in the narrative, bringing all its constituent elements into resonance. It's not the narration, it's the scene that constitutes the real stakes of the story.

Notes

///

[His horse] carried him at full speed / through the great dark forest. / He rode from morning / until daylight faded. / At night, he slept in the forest, / until daylight appeared. (Trad. Charles Méla.)

The whole meadow lit up / with the tent's reflections of light.

He approached the tent and found it open : / in the middle, a bed covered / with a silk blanket and, on the bed, / he saw a damsel asleep / who was there, all alone, lying.

Go away, lest my friend find you ! / If he finds you here, you're a dead man !

The young man headed for the tent / and said to himself even before he got there : / My God, it's your dwelling I see there ! / I'd be out of my mind / if I didn't go there to worship you. / My mother, I confess, was right, / when she told me to enter / every church I came across to worship / the Creator in whom I believe.

Tabernacle, in the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Bible, is said skènè, scene.

This is the village of Arene, a heavenly resort away from the city of Genoa.

Ibrahim addresses Soliman.

Isabelle Grimaldi, Rodolphe's only daughter. Justinian, the narrator's great-great-grandfather, had "always found himself opposed to an Astolphe Grimaldi, the one having always followed the party of the Fregozes and the other that of the Adornes [the two factions vying for power in the republic of Genoa] this hatred passed down to my father", so that "Ludovic Justinian (as the man who gave birth to me was called) never had any dealings with Rodolphe Grimaldi, head of this other family" (p.58).

Quoted in the Paris edition, P. Witte, 1723, 4 vols. in-12.

Surprise here refers very precisely to the " surprise of love ", or in Italian the inamoramento, i.e. what we call in modern French coup de foudre.

Isabelle will retire, in the rest of the novel, to Monaco : Scudéry's Grimaldis are the distant romanticized ancestors of today's Grimaldis of Monaco.

We'll see this, for example, with La Vie de Marianne.

At the sound of this graceful voice Arcitas rises. He who in prison had gone, he went to the garden of Love, without saying anything to Palémon, and he opened a small window to better hear this song, and also to see who was singing it, through the bars he passed his head outside.

See lesson #1, note 3.

See also the Comments des dernières guerres en la Gaule Belgique, entre Henry second du nom et Charles cinquième, by François de Rabutin. They open with an " Epistre au magnanime prince Messire François de Cleves, duc de Nivernois ", dated March 1554. François de Clèves is the father of our M. de Clèves. The siege of Metz is recounted in Book IV.

Brown wash, black and brown inks, black stone, pen on cream paper ; 40.8x55.6 cm, Paris, musée du Louvre, département des arts graphiques, RF29714.

Slight anachronism if this is A. Caron's painting. Le Siège de Metz is part of a series of 27 painting cartoons, by his hand, constituting the series of L'Histoire françoise de nostre temps, and illustrating the sonnets of apothecary Nicolas Houel, which were in fact executed during the reign of Charles IX, between 1560 and 1574, for widowed Catherine de Médicis. Reunited since 1948, they are now all housed in the Department of Graphic Arts at the Musée du Louvre. Mme de La Fayette's confusion, whether intentional or unintentional, may have been motivated by the existence of a drawing by the same Antoine Caron, of roughly the same size, depicting the Château d'Anet. Were these drawings preparatory sketches for tapestry cartoons ? The drawing for the Fête au château d'Anet in the Louvre is in /// In all cases quite different from the tapestry of the same name that can be seen at the Uffizi Museum in Florence, and which is part of the Valois tapestry series (eight pieces). See Jean Ehrmann, Antoine Caron, peintre des fêtes et des massacres, Flammarion, 1986.

Metalepsis is the cancellation of levels of representation : through it, the representation of representation becomes direct representation. See G. Genette, Métalepse.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Analyse d’une scène de roman : la canne des Indes », La scène de roman, genèse et histoire, cours donné à l'université de Provence, Aix-en-Provence, décembre 2008.

Fiction, illustration, peinture

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Fiction, illustration, peinture

La scène de roman

La scène de roman : introduction

Renaud dans le jardin d’Armide

Rastignac chez Mme de Restaud

Gilberte derrière les aubépines

La poignée de porte de tante Berthe

La double aporie du topos

Illustrer la fiction

Molière, une parole débordée

Marillier, l’appel du mièvre

On n'y voit rien

Illustrations de l'utopie au XVIIIe siècle

Le temps des images

Du conte au roman graphique

Déconstruire l’illustration

Régimes de la représentation dans la gravure d’illustration classique

Penser la fiction depuis la peinture

Une sémiologie du décalage : Loth à la scène

Introduction à la scène comme dispositif : Paolo et Francesca

La main tendue, le regard démasqué

De Silène molesté à la chair blanche des nymphes

Chambres de la représentation

L'intimité de Gertrude

Brutalités invisibles

Parodie et pastiche de Poe et de Conan Doyle dans Le Mystère de la chambre jaune de Gaston Leroux

Le dispositif de la chambre double dans Les Démons de Dostoïevski

Scène pour voir et chambre des brutalités

La Princesse de Clèves

L’invention de la scène dans le roman français

La canne des Indes

L'aveu

La princesse, la religieuse et l'idiot

Richardson

Entre scandale et leurre

Introduction aux Lettres angloises, ou histoire de miss Clarisse Harlove, par Samuel Richardson