The spectacular effect of the stage, in a novel, at the theater, in front of a painting, transcends genres, is immediate. It's what we retain best from a reading, a performance or a visit to a museum, even better than the meandering narrative, however breathless, which can't compete with the synthetic force that characterizes the stage, with the flash images it elicits and knows how to imprint durably on the memory.

What is a scene from a novel? The pedagogical stakes are obvious: the explanation of a text is often the explanation of a scene. To define the novel scene is therefore to provide the theoretical tools to carry out this kind of explanation.

I. Modeling the scene: some analytical tools

The scene as a failure of discursive logic

The scene is first and foremost the moment in the novel that escapes narration: an out-of-the-ordinary moment, an exceptional space where the novelistic machine comes to a halt, or at least changes regime. From narrative efficiency, we move on to scenic efficiency.

The consequences for those seeking to analyze the text before them are radical. Structural analysis, based on the search for the articulations of a narrative, on its grammar, on its discursive organization, ceases to be operative in a scene. The scene is neither a story that is told, nor a discourse that develops arguments. When the scene begins, the story stops, and in this moment of great dramatic intensity, it is not or no longer time to string together the logical and rational arguments of a constructed discourse.

The scene, then, does not obey a discursive logic1. There's more: knowingly, with genuine perverse glee, she often sets out to transgress, to subvert the order of discourse. A discourse is held during the scene, words are exchanged, but they are reduced to the insignificance of babble, they miss the point, they go the wrong way. The stage is the moment when discourse fails.

This is where iconic logic comes into play. Text then functions as a visual space, in the manner of painting, engraving or even photography. Writing leaves its own means to mimic the effects of the image. Text deploys itself outside its material nature, even against it, to take the place of what it is not, an image, a tableau: writing becomes a tableau. The stage is the moment of this reversal of narrative into tableau, a moment a priori impossible, improbable, but the spectacular effect lies precisely in this constantly re-experienced improbability.

The stage as performance transgression

The stage therefore unfolds only on the ruins of the discourse it deconstructs. To ruin discourse, it exacerbates it: the very theatricality of discourse in the scene deconstructs it.

The scene is often constructed as the transgression of a performance. A certain ritual is announced to the reader, sometimes very solemn (oath, vows in church, public presentation of an award), sometimes more anodyne or familiar (a certain consecrated course of the family meal, a way of grooming, receiving guests). But things don't go as planned. The scene describes the failure of the ritual, it thwarts the expectation that the announced performance has aroused: revolt or scandal, unexpected event or insidious slide towards the non-event, the narrative is diverted; the failure of the performance makes a scene, or the scene is constructed as anti-performance, as parody, detour, transgression of the known ritual.

What form does this transgression take, and how can we recognize it? Whereas speech is inscribed in the linearity of passing time, in the succession of events reported, of arguments invoked, in the scene time stops, things happen simultaneously, the effect is global. That's why space is so important in a scene. The scene is set in a space, and this space makes sense globally, is given all at once. But how can we give the illusion of space and simultaneity in a novel, which remains a work of writing, materially trapped within the structures of discourse?

Method

The book does not intend merely to analyze the notion of scene, or even to describe different kinds of scene. It would like to propose a method for explaining them. We have insisted from the outset on the visual dimension of the scene, marked in the text by the defeat of discursive logic and the installation of an iconic logic. It's no coincidence that illustrators generally choose to depict scenes on engravings, which are sometimes inserted into the text of books. At a deeper level, the notion of scene is not only borrowed from theater, which is an art of speech: the scene constitutes the fundamental semiological framework of classical painting. We propose starting from this visual dimension of the text to analyze it, as the writer probably imagined his scene before, or at the moment of, writing it. A scene can be outlined. Rendering the outline is already a way of ensuring that we understand exactly what's going on, and pinpointing any grey areas. It superimposes the material layout of the characters and slieux onto the symbolic relationships between the characters, and the rituals and prohibitions that separate or link them. />pclass='normal'>The analysis of the text is geared towards this objective: to identify the scene's layout, and to see how the visual effects, which are extremely concrete, and the symbolic stakes, which are often hidden, are superimposed.

Ten hours under the lime tree: a Stendhalian example

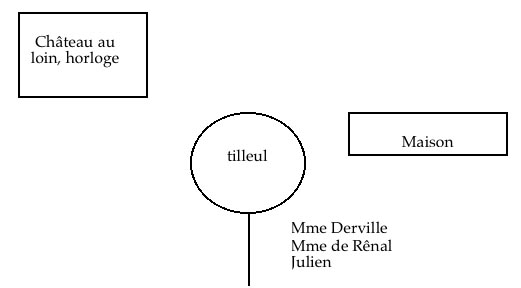

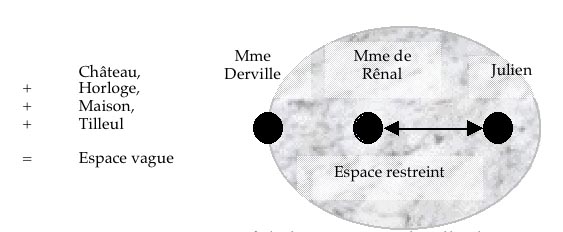

Let's take the scene under the linden tree in Le Rouge et le noir as an example: Julien Sorel has promised himself that he will dare to take Mme de Rênal's hand when ten o'clock strikes on the castle clock. His anguish at this terrible challenge leaves him speechless. It's impossible for the characters to string ideas together. Time itself stands still: the novelist can't string together the events of his story, which remains suspended as the fateful ten o'clock approaches. The failure of discursive logic paves the way for the scene. Julien is seated outside under the linden tree, next to Mme de Rênal, who is herself near her friend Mme Derville. The scene thus consists of a first space, restricted to the two protagonists, and, beyond that, a vague space opening out from Mme Derville and including the château clock. The interplay of these two spaces, the vague space outside and the restricted space of the stage proper, constitutes the geometrical dimension of the device.

Night has fallen. Posed symbolically over Mme de Rênal and Julien, yet unable to see anything because of the darkness, Mme Derville's gaze at once signifies and forbids what is being accomplished. Because Mme Derville sees nothing, understands nothing of what is happening, she makes the reader aware of the intimate nature of what he is witnessing. What he sees cannot be seen. Our view of the scene is forbidden: Mme Derville signifies this prohibition; she thereby constitutes the screen of the scene.

When Julien extends his hand and takes Mme de Rênal's, she withdraws it; Julien grasps it again and this time keeps it. Mme de Rênal's first gesture and Julien's second gesture carry, without words, the meaning of the scene: in their very symmetry, which makes sense, they implement an iconic logic. They turn the situation around twice, establishing a convulsive communication between the two lovers that goes beyond the symbolic sign of their sealed union ("he held her with convulsive strength"). Finally, at the moment of revolt, Stendhal notes a detail, "the icy coldness of the hand". Details are rare, and all the more significant in this perfectly tuned text. This coldness fleetingly suggests that Mme de Rênal, whose interiority remains veiled since the scene is told from Julien's point of view, is experiencing the same torments as he is. But this is only hinted at, like a vague but persistent impression, whose interpretation is left open. This coldness constitutes the "something" of the scene.

II. History of the scene

Before the stage, the forbidden gaze

The essence of the scene therefore remains veiled, and the gaze that is cast upon it is one of breaking and entering. The last thing Julien wants is Mme Derville to overhear his gesture. We see what she sees, what the audience must not see; but we are the audience. The stage, in its very set-up, carries both the memory of a very old cultural prohibition and the principle of transgressing that prohibition.

The history of the novel stage is deeply linked to the history of the image, which is marked in the Middle Ages by the biblical ban on representation. The Old Testament founded monotheism on the prohibition of idol worship. For this reason, more generally and more radically, it forbids all figurative representation2. However, at the very moment when this prohibition is formulated, the biblical text makes a deviation, opening up an exception: it prescribes in minute detail the form and appearance that the tabernacle must take, i.e. the tent that contains the ark in which the Ten Commandments are enclosed, including the prohibition on representation. />pcas'normal'>Or the tabernacle, and later the Temple of Jerusalem built on its model, is decorated with figurative representations3. In Western medieval biblical exegesis, this tabernacle served as a matrix device to legitimize the Christian practice of the image: the Christian image is a tabernacle whose sensitive surface refers to an intelligible truth in the manner of the tabernacle, divided into two parts by a veil. The first part is accessible to the faithful; the second, which contains the tables of the law in the ark, can only be crossed since the coming of Christ: at his death, did not the veil tear? The icon should therefore be seen as the sensitive veil behind which the faithful gain access to the clear vision of God. This movement of the gaze is referred to as translatio ad prototypum.

From the twelfth century onwards, the image-tabernacle essentially becomes the image of the Virgin, whose body, where the Father came to become incarnate, is identified with the tabernacle, which contains the ark and the Tables, i.e. the Word4. At the same time, in the great medieval romance cycles that developed from the thirteenth century onwards, the place of quest tended to become both a metaphor for the Lady's body and a receptacle for mystical revelation. A diffuse opposition tends to be established between what belongs to the image - the flesh and the place, the feminine and the sensible - and what belongs to the text - The Father, the invisible.

In the Renaissance, the image became secularized and the device of representation became above all technical. Yet the invention of linear perspective, which turns the painting into a window and constructs the depth of space by interposing between the draftsman and his object the squared veil of the intersect5, insidiously perpetuates the tabernacle device whose discourse the humanist revolution had dethroned.

The image then abymes and thematizes the device that constitutes it: it represents, at the margin of the painted scene, the "forbidden" gaze of the viewer, who must cross an obstacle to reach the scene proper. It is this obstacle, heir to the tabernacle veil, that we designate as the screen.

Subjects that place the prohibition of the gaze at the center of representation are flourishing in painting: Loth's flight6, Susanna and the old men, Diana surprised by Actaeon and, from there, simply Diana at the Bath. This new iconic device is itself imported into texts via theater and opera and ballet sets.

The Ut pictura poesis, birth act of the stage

A parallelism of the arts is emerging, theoretically abolishing all boundaries and even hierarchies between poetry and painting, text and image. This is the doctrine of ut pictura poesis, "poetry as painting": Horace's line is often turned7. Painting must function like poetry, like text.

Or the means of expression of text and image do not sit well together: we're going to have to find a medium that makes discursive logic and iconic logic converge, inscription in time provided by the story and immediate visual effectiveness delivered by the image. This medium is the stage, towards which all the arts, not only literature and painting, but architecture and opera, will converge. />pcas'oml>The word stage comes from the Latin scæna, which designates not so much the scenic space in which the actors move as, technically at least, the stage wall, i.e. the backdrop that both evokes and bars perspective8. The stage opens up a space and divides it. As for the Latin scæna, it refers to the Greek skènè, which certainly designates the trestles of the theater, but also more generally a tent and, in Biblical Greek... the tabernacle.

This is to say that, like all Renaissance inventions, this novelty constituted by the stage is ambiguous: in the stage device, the screen (the stage wall, the tabernacle veil) constitutes an archaism, a heritage weakened by the secularizing movement of culture and the progressive distancing of the biblical prohibition of representation.

The stage as a supplement to the agon

The stage is the response to a general crisis of representation, reflected in the decadence and dissolution of a culture of myth and epic. Epic and myth do not represent reality, but values. It's a culture of the signified: the work of art figures another world, a mythical and magical world, of values, of ideals.

The stage, on the other hand, escapes the culture of the signified, rebelling against it: it tells of the deconstruction, then the transgression of the values and ideals carried by this old culture. It is no longer based on the interplay of signifier and signified, but on the conflict of signs in reality. The stage exhibits the dysfunction of signs. The stage device is the spatial, iconic organization of this conflict that precipitates it from representation to reality.

For the stage alone does not constitute another culture in the face of the old culture of the signified. Rather, it reveals the limits of this old culture and, in a way, saves it from a slide into insignificance by creating a jolt, by establishing in extremis the anchoring in the real that was lacking in the old cultural representations. The stage is not a counter-culture, it does not establish a new culture; the stage is a matter of replastering, bricolage, scaffolding: the stage is the supplement to a culture in crisis.

This is how the stage device enabled the passage from epic to novel, from history painting to genre painting. The epic did not provide the reader with scenes, but with a agon, that is, in Greek, a combat: face to face between two heroes on a battlefield, a dialogue between two mythical figures in the measured space of the tragic theater, the confrontation is not between two value systems, but, within a single system, it dialecticizes the advent of a single meaning, even if the signifiers that lead to it never stop unfolding and branching out: The Greeks and Trojans of the Iliad have the same gods, the same language, the same weapons and pursue the same ends; Sophocles' Antigone and Creon confront the same fundamental contradiction of justice and law on which our entire symbolic system still rests: there is not one good and one bad, not even two points of view, but a single contradiction that the two figures dialectize until Antigone's inescapable death.

The agonistic ritual is therefore sometimes hand-to-hand, sometimes exchange of words, military or verbal confrontation. The agon speaks of the values of the city; the conflict reveals the ideological community to which the epic's recipients adhere. The agon constitutes culture as a representation of this ideological community. In this sense, the agon is the form, the mode of being of the culture of the signified.

This form comes into crisis in the Italian epic of the Renaissance. The two most famous epics are, on the one hand, Ariosto's Roland furieux, which is presented as a sequel to la Chanson de Roland and, in a way, a parodic sequel, on the other hand, Tasso's Jerusalem Delivered, which, initially at least, transposes the great epic confrontations of the Iliad and Eneid to the world of the Crusades.

The deconstruction of the agon in these Italian epics prepares the substitutive advent of the stage, whose grandiloquent theatricality makes up for the deficiencies of the ancient ritual: the agon first multiplies infinitely in Ariosto, who precipitates flees, pursuits and encounters in a universalized space. The agon aborts, telescoping with the chance encounters provided by unbridled chance. Permanent flight avoids the dialectization of the signified. Armide's gardens, which hold Renaud prisoner to his desire, block this desperate flight, but also block it in the scenic representation of Renaud's virile impotence. The stage is the icon of the agon aborted: the failure of the fight, the hero's defection, make a tableau in a space that then constitutes a scenic device.

The stage is invented here to make up for an agon threatened by contingency, chance and the encounters of reality. Later, in the novel, the failure of discursive logic by the device of the stage will preserve the memory of this suppletive origin. The stage is always re-enacting its own birth: each time again, it comes to the rescue of the agon, i.e. of discourse that has become ineffective. The spectacular effect of the scene compensates for the loss of epic ritual. The novel manufactures scenes to make us forget the lost epic, to rediscover, with new means, the prestiges of the epic.

The deconstruction of the classical screen: dissemination, communication

The eighteenth century saw a profound mutation of the screen: it became multiplied, scattered across the stage; never have there been so many; never have they been so ineffective. From Crébillon9 to Boucher, the screen becomes decorative and aestheticized in the libertine fantasies of roccoco. Then the screen becomes sensitive: it communicates sensation instead of intercepting the gaze. It moves from one scene to another within the same sequence.

This semiological mutation is fundamental: the gaze, reduced to its scopic dimension, now ceases to be the central vector of the scene's device, which is no longer necessarily ordered according to a play between the vague space of reality (from which the spectator looks by breaking in) and the restricted space of the scene itself.

Figure 4: Boucher, Dame attaching her garter, and her maid, 1742. Lugano, Thyssen-Bornemisza collection. A fireplace screen can be seen on the left, and in the background, top right, a Chinese screen, behind which a portrait seems to be peering at the scene. The glass door to the right of the mantelpiece is ajar: a shadow looms in the gap, a person or simple hanging garment, suggesting, behind the scene, a vague space.

Contact, touch, envelopment, the sensitive continuum become the new vectors of sensory communication. The scene still functions as a game between several spaces, but these spaces tend to constitute so many scenes between which the textual sequence, like the painted canvas, organizes a journey. The new device that emerges contrasts the scene in front, punctuated by initially incomprehensible clues, with a scene behind, an off-stage that is not given, that we have to reconstitute.

.The scene and the other scene

This other scene tends, from the end of the nineteenth century onwards, to become the fundamental and unique core from which the novel, indeed the entire work, is built. In a way, the scene emerges from representation, which settles on its margins.

But at the same time, literature is engaged in an intense recapitulation: all the old devices re-emerge. However, the geometrical dimension of scenic devices is weakening: the challenge is no longer essentially to bring together depth of perspective and social rituals, the theatricality of the gesture that underlines the discourse and the inscription of this gesture in a pictorial space.

It's not just a question of theatricality of the gesture that underlines the discourse and the inscription of this gesture in a pictorial space.

The heart of the scene is now the psychological interiority of the characters: it's a question of penetrating this interiority, of tearing away the veil, the screen-envelope that conceals from us the enigma of their depth. The scene comes to die in this abyss of the "self" where all history, all action come to dissolve into affect.

In the meantime, another history of the stage has taken shape, reintroducing the gaze into the heart of the device: the cinema stage takes over from this cultural heritage, at the cost of a semiological revolution as important as the one that, in the Renaissance, had passed the baton from the veil of the tabernacle to the veil of the intersect.

Notes

All the key notions that are implemented in this book are summarized in the index.

"Thou shalt not make for thyself any sculpture, or any image of anything that is in heaven above, or on the earth beneath, or in the waters under the earth. You shall not bow down to them, nor serve them." (Ex. XX, 4-5; Dt. V, 8-9.) This is the second commandment, coming just after the monotheistic affirmation, "Thou shalt have no other gods before me."

"two cherubim of embossed gold" (Ex. XXV, 18) face each other on the mercy seat; the curtain is "embroidered with cherubim" (Ex, xxv, 31). When Solomon built the temple, he reproduced the cherubim, and added the bronze sea that "rested on twelve oxen" (I Kings VII, 25). See the commentary by Bede the Venerable, De templo liber II, Corpus christianorum, Series latina, Brepols, 1969, p. 212, l. 809-832.

BERNARD DE CLAIRVAUX, Sermon 52 of the Sermons on the Virgin; Jean ALGRIN, In Canticum canticorum; ALBERT LE GRAND, Mariale.

See further, chap. II, part 2 and figures 3 and 4.

See S. LOJKINE, "Une sémiologie du décalage, Loth à la scène", introduction to La Scène, littérature et arts visuels (full references in the Bibliography at the end of the volume).

HORACE, Art poétique, v. 361 and Rensselaer W. LEE, Ut pictura poesis, Humanisme et théorie de la peinture, XVe-XVIIIe siècles.

" The term "scene" falsely translates the Latin scæna. By stage, we understand a dais, whereas the Romans meant the stage wall that stands vertically facing the spectators. Pierced by three doors, the stage wall is the empty façade of an unreal world from which the characters will emerge to play their roles. The scæna is in fact what defines theater as a place of fiction, of appearances without content, of illusions without models." (Florence DUPONT, Le Théâtre latin, Cursus, A. Colin, 1988, p. 17.)

Le Sopha by Crébillon (1739) infinitely multiplies the screen device of the classical stage: changed into a sopha, the narrator unknowingly witnesses the confidences and frolics of the visitors to the boudoir where he finds himself. But the sopha no longer establishes the distance of a gaze from the restricted space of the stage. The whole point of the story lies in the contact, the parodically sensitive communication that is established between the narrator and the protagonists of the scene.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, Introduction à La Scène de roman, Armand Colin, collection U, 2002, p. 4-13.

Fiction, illustration, peinture

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Fiction, illustration, peinture

La scène de roman

La scène de roman : introduction

Renaud dans le jardin d’Armide

Rastignac chez Mme de Restaud

Gilberte derrière les aubépines

La poignée de porte de tante Berthe

La double aporie du topos

Illustrer la fiction

Molière, une parole débordée

Marillier, l’appel du mièvre

On n'y voit rien

Illustrations de l'utopie au XVIIIe siècle

Le temps des images

Du conte au roman graphique

Déconstruire l’illustration

Régimes de la représentation dans la gravure d’illustration classique

Penser la fiction depuis la peinture

Une sémiologie du décalage : Loth à la scène

Introduction à la scène comme dispositif : Paolo et Francesca

La main tendue, le regard démasqué

De Silène molesté à la chair blanche des nymphes

Chambres de la représentation

L'intimité de Gertrude

Brutalités invisibles

Parodie et pastiche de Poe et de Conan Doyle dans Le Mystère de la chambre jaune de Gaston Leroux

Le dispositif de la chambre double dans Les Démons de Dostoïevski

Scène pour voir et chambre des brutalités

La Princesse de Clèves

L’invention de la scène dans le roman français

La canne des Indes

L'aveu

La princesse, la religieuse et l'idiot

Richardson

Entre scandale et leurre

Introduction aux Lettres angloises, ou histoire de miss Clarisse Harlove, par Samuel Richardson