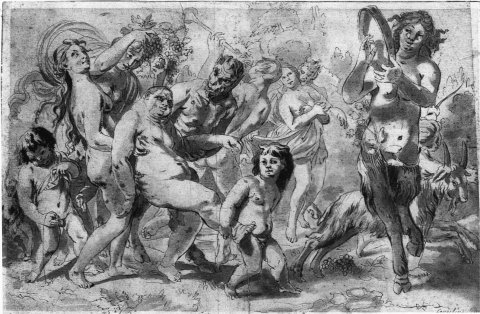

Rubens, Silenus, Aegle and other figures, 1612-1615, private collection of Elizabeth II of England

The pictorial representation of bacchanalian scenes in the Classical period knows two opposing models1. The first is Italian. Inherited from the idealizing neo-Platonism of the Renaissance, it features the utopian, blissful world of gods and men in celebration, enjoying the pleasures of the otium amid music, dance and wine. This " laughter of the gods " where laughter is substantive has as its archetype a ekphrasis by Philostratus, the description of a 3rd-century painting depicting the Andrians2. The inhabitants of the island of Andros in the northern Cyclades celebrate the cult of Bacchus around the river of wine that used to flow through their island. Based on the ekphrasis of this lost painting, the Latin translation of Philostratus by Blaise de Vigenère proposed, in the 1614 edition, an engraving and Titian painted his famous Bacchanale des Andriens, now in the Prado Museum : the painting was subsequently copied by Rubens and by Poussin.

The second model is Flemish : in the parodic and burlesque vein it stages the degeneration of the gods through wine, the fall or slouch of Bacchus drunk and aging, or Silenus molested, debased in drunkenness and exhaling his song. Here, " laughter of the gods " is understood as a verb and an act, and no longer as a noun and an object. From the anacreontic beauty of the Andrian mysteries, we have moved on to the repulsive ugliness of a decried, parodied and fallen world. Rubens is not the only, but the most famous craftsman of this second vein popularized by engraving.

Figure 1: Pieter C. Soutman, Drunken Silene, 44.3x48.5 cm, Plantin-Moretus Museum, Antwerp. Engraving after Rubens (see Figure 13: Bachanale, 1615, Pushkin Museum, Moscow)

The archetype again is textual it's Virgil's sixth eglogue, which tells how Silenus, caught drunk and asleep by two shepherds and the nymph Aegle, was bound and smeared with blackberry juice :

" Sanguineis frontem moris et tempora pingit3 "

Églé painted her forehead and temples with bloody blackberries.

The idea was to force him to sing. This one willingly complies. His carmen turns out to be a cosmogony, starting from the principles of all things (semina terrarumque, animaeque, marisque [....] and liquidi simul ignis, the seeds of earth, breath, sea, and all at once liquid fire) to evoke some great myths (Prometheus' flight, the disappearance of Hylas, the loves of Pasiphae, the apotheosis of Gallus, the two Scylla, Philomela and Tereus), until the coming of evening interrupts the song.

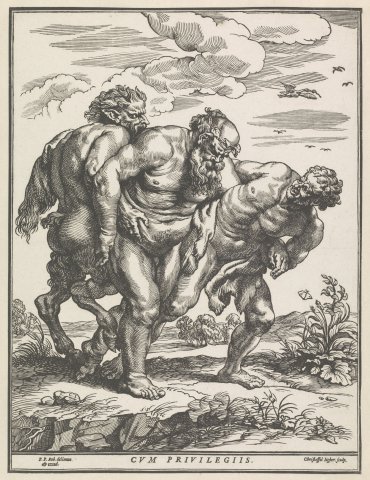

Figure 2: Christoffel Jegher and Pieter P. Rubens, Drunken Silene, 46.3x34.9 cm, Plantin Moretus Museum, Antwerp. Moralized" engraving after La Marche de Silène (see Figure 16: Rubens, La Marche de Silène, 1618, Munich, Pinakothek)

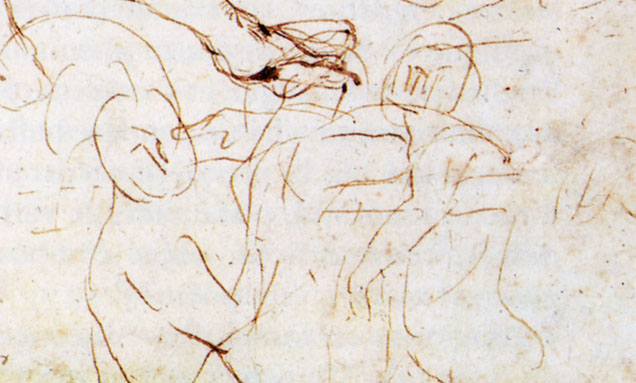

The Flemish painter accused the violence of the line in a staging that in Virgil seemed bound to remain within the innocent bounds of light farce and mutually consensual play. In the Antwerp drawing, which may represent Rubens' first staging of this story, Silenus slumps over a wine barrel and a reclining tiger, dropping his head onto his folded left forearm, where ties can be made out.

The Flemish painter accused the line of violence in a staging that Virgil seemed bound to keep within the bounds of light-hearted farce and mutually consensual play.

Above him, on the left, a stern-faced woman holds his right arm while encouraging a third figure, probably a satyr, either (if we're going by Virgil) to squeeze the blackberry juice between his hands, or (if we're taking into account the stripes in the drawing) to strike Silenus with a bundle of rods. Completely to the right, hidden behind the barrel, a child observes the scene.

Figure 3: Rubens, Silene and Aegle, 14x12.5 cm, pen and ink with wash and white highlights, Antwerp, Stedelijk Prentenkabinett

The scenic device we observe in this drawing will have no immediate sequel it's another version of the same scene that Rubens has chosen to proliferate, as if to screen the primitive violence of what is here depicted. This other drawing, now in the private collection of the Crown of England, is more difficult to decipher, as the story of Silenus and Aegle remains in the sketch stage. But it served as a matrix for a good dozen Rubenian paintings.

Our investigation will therefore have three aims. Firstly, based on a study of the drawing in the Royal Collection of England, we will look at the personal significance that the Bacchic myth took on for Rubens, and at the advantage he drew from this archetypal ambivalence.

The second objective is to examine how the Bacchic myth was used by Rubens in his paintings.

Or the drawing didn't lead to the expected painting the representation branched off into a screen scene which it made a fortune. We will ask how, through this screen scene, Rubens articulated the imaginary core provided by Silene and Eglé to a device of symbolic reversal likely to make work.

Finally, we will attempt to identify, through the pictorial device that is constituted and transformed in the work, the modalities of the Rubenian relationship to the symbolic and, beyond that, that dialectic of flesh and law specific to classical culture.

The face-to-face encounter between Silenus and Aegle : sketching a horrifying scene

In a recent book, Svetlana Alpers has put forward the hypothesis, in connection with Rubens' Silenes books, that the painter represented himself in this figure of a staggering old man and staged, through Virgil interposed, the very process of his artistic creation, the pingit of the verse from the VIth eglogue then taking on a whole new meaning. For Svetlana Alpers, what is at stake in the Rubenian bacchanal is neither the celebration of wine (Rubens was, moreover, relatively sober), nor its condemnation : Rubens would, as it were, have symbolically located the locus of his creativity not in his studio, nor in the company of books or models, but in the materiality of flesh and naturalness /// familiar from his exhibition. The crux of the demonstration rests on this drawing from Elizabeth II's private collection depicting, we are told, Silene, Eglé and d'other figures. This drawing is difficult to date at first sight : if it was made after Rubens' trip to Italy, it may have been in 1608, as well as 1620. We will put forward a more precise date later.

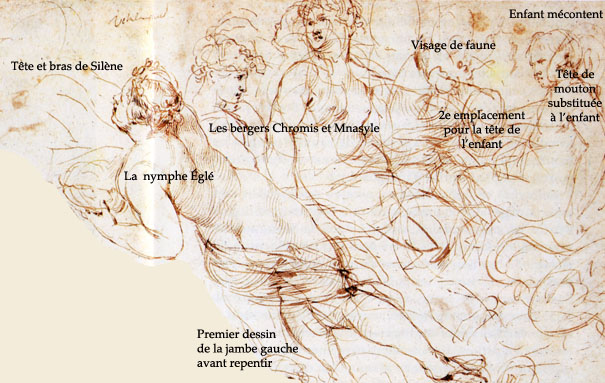

Figure 4: Rubens, Silene, Aegle & other figures, Private Collection of Elizabeth II of England

The impression of an anarchic proliferation of figures fades as soon as we grasp the drawing in the process of artistic creation and not as a completed whole making overall sense. The same scene is in fact depicted two or even three times, while at its margins an alternative representation is sketched out, the one that, in the painting, will finally be chosen.

Description : three versions of the same scene

The first version of the scene is barely sketched. At the very top, through the two androgynous figures facing each other, a woman's body lies on her stomach. She raises her head and seems to extend an arm, barely suggested by the outline of two hesitant strokes, more like a movement, a direction she is pointing, than an outline or an indication of volume. This is the first sketch of the nymph Églé, the features of a face in profile, the extended gesture of her right arm and the shape of her elongated body, a shape of flesh without contours. Above Églé's hips, an oval of a face marks the empty spot of a spectator.

Let's formulate the hypothesis that Rubens went from the top to the bottom of the sheet, refining, specifying more and more what at first was only the nodal vision of a gesture, Aegle's outstretched arm and the voyeuristic gaze focused on this ambivalent gesture of the nymph crushing the blackberries on Silenus' face, a gesture of soiling and love.

The first version of the scene, barely sketched at the top edge of the paper, is repeated at its center, with Églé clearly placed at the heart of the representation. This second version, already much more finished, widens the field. Églé, still lying on her stomach, leaning on her left arm, holds a basket and stretches a still barely sketched right arm towards a form that is reduced to a few strokes, but which, in anticipation of the third version, we can deduce to be the form of Silène.

Above Églé sit the two figures that bite on the first version : the figure on the left turns completely away from Églé and with a gesture of the left hand seems to be protecting himself or adjusting a garment the figure on the right turns his head to see, despite his position. These two young, elegant figures are androgynous, so to speak, as evidenced by the chest of the one on the left, neither quite flat, nor blooming in the Flemish roundness to which Rubens is accustomed.

.

A third spectator figure is drawn completely to the right, frowning reprovingly. Smaller, almost /// Fluid, with no marked musculature, it must be a child. This third figure was the subject of a series of repentances. Rubens, who initially placed it far back on the stage, sought to fill the gap between the child and the three large figures. He sketches a faun's face ; but he also marks with an oval the possible location, much closer to the scene, of the child's head and replaces the one originally drawn with a sheep's head.

.

The third version of the scene, finally, is the most accomplished, not only in the line work, but in the coherence of the composition. At the bottom left of the page, Églé is this time positioned between Silène's thighs (in the second version, a repentance on her left leg prepared the way for this arrangement). She smears the god's forehead with her right hand, her left hand holding the cup or basket containing the fruit or juice. Behind Aegle, the figure on the left, contaminated by the faun sketch, has become a laughing satyr with a pampers-crowned forehead the figure on the right is clearly feminine this time, her left arm covering her chest in the ancient manner of a Venus pudica. The two figures have been shifted to the left to tighten the scene. On the right, the child spectator is smaller, his two-armed gesture angrier. His right fist, about to strike the pudica's knees, makes him part of the scene. Another child has been added to the lower left corner, who appears to be holding Silenus' right hand captive.

But Silene is the great novelty of this third version. He, who holds the central place in Virgil's Eglogue, comes last, as if rejected to the periphery of the representation, where the scene, heightened with brown wash, is at once the darkest, the most expressive, the most finished.

The three versions of the scene thus cross the paper diagonally, leaving the upper left and lower right corners free, which Rubens uses to work on the hitherto neglected figure of Silenus.

A head can be seen at the top, its closed eyes contrasting with the aggressive gaze of the Silene below. Further left, a staggering figure with unclear contours is reduced to the pure movement of a collapsing body. Finally, in the lower right, a figure, as if held upright by a bar passed under his armpits (barrier, branch, arm ?), appears flanked by two acolytes. This horizontal bar, more visible at the bottom, is found at the top under the shoulders of Silenus sketched in four strokes facing the central Églé (in the second version, then), as if here opened up the alternative between the scene represented here, Églé smearing Silenus with blackberry juice, and the scene we'll find in the later Münich painting (see Figure 16), Silenus staggering supported by his drinking companions.

If we go back to Virgil's sixth eglogue, it appears that Silenus has been discovered by two shepherds, Chromis and Mnasyle4. It seems that Rubens first depicted the two pueri Dionysiacs with effeminate features, then, /// departing from the book source, differentiated them in the lower scene into a laughing faun and a chubby, prudish young woman, as if to mark and contrast sexual identities.

Interpretation : from identification to the primitive scene

This discrepancy could be the first clue to the shift that takes place here from the bucolic Virgilian universe to the world of Rubens, where virility is clear-cut, flesh - feminine and round, where the " given to see " of the scene is lively and greedy. Another character raises questions: what is the meaning of the wrathful child who, in the scene, is the counterpart of the outraged Silenus? Moreover, why does Rubens fork the scene, finally abandoning Aegle for the Drunken Silene of Münich, which is sketched as a repentance at the unoccupied margins of the primitive diagonal ? Finally, what is the meaning of the enigmatic inscription above the central figure of Églé that stands out in a void left by the drawing ?

Let's start with the inscription. S. Alpers, taking up an interpretation by E. Mc Grath, suggests reading vitula - gaud[ium], by reference to verse 85 of the third eglogue, which Rubens would have arrived at through the play of cross-references and the index of the commentator Pontanus. Why refer to the third eglogue, when it comes to representing the sixth ? What does vitula, the heifer, have to do with a scene devoid of animals, at most a vague sketch of a sheep in the upper right of the drawing ?

We propose a reading that may be more hazardous to decipher, but whose meaning seems more satisfactory : " vincla-gaud[ium] ". If the second word was left unfinished, it's perhaps not absurd to consider that, in the first, the c wasn't perfectly formed. Yet vincla, a common contraction for vincula, could well reveal what's at stake in the performance. Verse 23 of the sixth eglogue :

" Ille dolum ridens : Quo vincula nectitis, inquit ;

Solvite me, pueri ; satis est potuisse videri. "

" Silenus laughing at their cunning said to them : why do you form bonds ; untie me, children ; it is enough that I may have been seen. "

From the constraint of bonds will come Silenus' song and the enjoyment it brings, not laetitia, the expansive jubilation of the bacchanal, but gaudium, inner enjoyment. This is a far cry from the conventional discourse on Rubenian flesh, interpreted as the engine of pure expansive pleasure in colorful creation. It's Silenus' fettered, masculine flesh that arouses jouissance. Svetlana Alpers notes this shift from the feminine to the masculine and suggests that, for Rubens and perhaps beyond, it represents a fundamental sexual ambivalence in the creative act. But apart from the fact that this explanation does not link the question of the flesh to the motif of the bond, central in the sixth eglogue whatever the deciphering of the words scribbled by the painter, it contradicts the creative movement that is outlined here in the three versions of the same scene, a movement not of turning the masculine into the feminine (the painter's flesh becoming that of the women he paints, according to S. Alpers), but of differentiating and even accentuating sexual differences.

.

Here we touch on the heart of the analysis proposed by S. Alpers and what, in our view, points to its essential theoretical weakness. The perspective of his chapter II entitled " Creativity incarnate " is psychological : the representation would fundamentally represent the creator creating, and Rubens would have personalized this archetype in the form of the singing Silenus from Virgil's sixth eglogue, with whom he would maintain /// special affinities.

Is this identification, assuming it is indeed the aim and stake of representation in general, and painting in particular, conscious or unconscious ? If it is conscious, it has not only a meaning (which S. Alpers seductively analyzes), but also an intention. What is this intention? How is it marked? Not a single clue, resemblance or attribute points to Silenus as a figure by Rubens, or by the painter in general, in a painting otherwise well-versed in all the devices and tricks of allegory. There's even more: there's nothing to indicate that Silène is singing; he, the latest arrival on the scene, contorts and remains silent.

.

The identification would therefore be unconscious. The representation is no longer deciphered as an allegory, but as a dream, with its processes of condensation and displacement. And the dream refers only incidentally to what the subject does ; Freud showed how the essential material of the dream, awakened conjuncturally by this or that recent circumstance, was made up of the psychic accidents of early childhood, not what does, but what is the subject in its relationship with the primary objects of identification and desire, the father, the mother, and with intruders, brothers, sisters, or any other newcomers interfering with these privileged relationships.

The dream, then, very often awakens the primitive scene, or at least screens it, a scene where the child, purely a spectator, pierces the mystery of what is going on between his parents, of this act by which he was created and which comes to his gaze like a wound. At the root of the dream, at the nodal point of what makes sense within it, the subject is thus absent, since what is represented is what makes him before he is, or more precisely, outside him, beside him: a heart-rending, horrible subjective wound, yet constitutive of all knowledge.

.

If, as we believe, the drawing of Silene and Eglé figures and at the same time obscures for Rubens the primitive scene, if fundamentally it constitutes the screen from which all Rubenian creation unfolds, the painter represented himself in it only incidentally : he is the indignant spectator of an unbearable scene, this child who first recoils, then advances and revolts, striking with his fist the one who, Venus pudica, must be his mother. As for Silenus, whom Rubens identifies in other representations with Bacchus, he is the Liber pater, both Italic god of wine and that promiscuous father of Peter Paul whose affair with Anne of Saxony cost the Rubens family so dearly. How can we fail to recognize here the father caught in the bonds of adulterous love, then in those of the prison where William the Silent, the deceived husband, precipitated him, condemned him to death and only pardoned him after the obstinate representations and interview obtained from Maria Pypelinckx, the devoted wife who was to become Peter Paul's mother? The father struggles in his bonds; his contortions are reminiscent of those of the marble Laocoon, whose monstrous snake's rings are dragging him and his sons to the sea. Rubens had drawn the famous sculpture of the Pergamon schoolgirl during his stay in Rome.

.

Between her legs, Aegle brings her hand against him, offering enjoyment and pain from the bonds, vincla and gaudium. She is the father's other wife, the never-seen intruder arousing the child's fascination and revolt.

The first sketch depicted only Églé's back and the outline of a spectator's face : such is the core of the primitive scene for Rubens, the son surprising the father's secret, Jan's vinclagaud subjugated by Anne de Saxe an impossible scene let's remember, since the events took place before the painter was born, and Anne de Saxe divorced from her husband and /// imprisoned by him, never sees her lover again. The father's body only appears after differentiation, when the son dissociates himself from the father, slipping from the fascination marked by the oval suspended above Églé's back (in the first version of the scene) to the revolt of this erect right arm, which curiously, in the third scene, somehow repeats the gesture, the aggression of the naiad.

Something, then, in this scene revolts and turns, something that has to do both with the decay of the father (what Lacan calls the " castrated master " 5) and with the revelation of a knowledge, either a knowledge taking the place of jouissance (this is Silenus' sung cosmogony), or the knowledge of jouissance itself, of which the scene offers the tableau. The father's fall from grace, the knowledge he communicates in the son's revolt, the identification with the father that here unravels, giving rise to sexual differentiation - this is both the material of the primitive Rubenian scene and the mainspring of the "laughter of the gods" whose ambivalence proves to encompass the dialectical pairing of jouissance and knowledge: the gods, the father and his wives, enjoy ; but to discover their enjoyment is to turn it inside out, both to turn gaudium into vincla and to turn the phallic power of the father into derision of the phallus, which is knowledge about the phallus.

Exhibitionist reversal and bacchanal-screen : Silenus between two women

The screen-scene of Silene and Eglé sketched in the Antwerp drawing and completed by the one in the Royal Collection of England will never lead directly to a painting, as if the face-to-face encounter between the devouring wife and the bound father could not be sustained. Rubens replaced it with a Bacchanal more innocuous in appearance, where the phantasmatic knot is veiled and off-center, drowned in a multitude of characters. The painter must have been particularly fond of this little Bacchanal from the Pushkin Museum, which earned him a certain notoriety and which he reproduced in the foreground of the Allegy of the view, a picture painted in collaboration with Jan Brueghel de Velours.

Figure 11: Jean Brueghel de Velours and Pierre-Paul Rubens, Allegory of the View, Madrid, Prado Museum. In the foreground is Rubens' Bacchanale

In this Bacchanal, Silenus is no longer attacked, nor bound. The terrible gaze, in the drawing of Silene and Eglé, has here closed, dozed : the head develops what Rubens had sketched in the upper left-hand corner of the drawing. The rebellious child has disappeared. But is it Silenus or Bacchus? In any case, it's Bacchus' procession that's featured here, as evidenced by the presence of a black woman and a tiger in the center of the painting. Legend has it that Bacchus, on his journeys to the East, won the Ethiopians over to his cult and tamed the tigers. The black woman and the tiger would return almost systematically in later Bacchic scenes, functioning as veritable attributes of Silenus-Bacchus in the same way as Jupiter's eagle, or Juno's peacock.

Nigra sed formosa

Apparently, then, the mythological screen here has finished distorting and obliterating the primitive scene. Yet in this scene of laughter and light derision, the primitive aggression persists latently; erased from the obvie meaning, it remains disposed as aggression. It's no longer a scene of aggression, since in place of Silenus and Aegle's face-to-face, Rubens has substituted a pretty young girl behind Silenus' back. The confrontation is over, and the scene is subjectively cheerful, warmly colored, dancing with its circular structure and interplay of legs. The aggression is in place, but makes no sense. It is the geometric substratum of the representation, outside the scopic effects of color and at odds with the allegorical decoding of the scene.

Figure 13: Bachanale, 1615, Pushkin Museum, Moscow

The arrangement here is organized around a central patch of shadow, produced by the black woman's body. The colored texture of the representation is here perforated, precipitated into an agonizing void around which the characters' crowns draw a ring of animal flesh. The woman, taken a tergo by a hideous goat-foot even more animal than the others, is enjoying herself. This is the image of the woman's jouissance as the black object of forbidden knowledge, both the heart and stake of the painting and the point of defection of its color. Yet this black, bestial and forced jouissance could well, symbolically, refer to its sublime reverse, the high, spiritualized jouissance represented by the mystical bride of the Song of Songs, nigra sed formosa : like Anne of Saxony for Jan Rubens, the Queen of Sheba for Solomon was this lofty object of desire opposed by the repulsive, low and sordid flesh of motherhood, the bestial orality of pleasure which is displayed here, in this Bacchanal from Moscow, bottom right, under the figure of a vile satyress disgorging the milk from her distended breasts into the voracious mouths of two repulsive satyrs. The motif of the suckling satyress can already be found in the painting by Piero di Cosimo6 which, in the Tales of Silenus cycle, represents La discovery du miel. But Rubens substitutes two children for the only child on Piero's canvas. The detail is not accidental: there were already two children in the third version of the drawing in the Royal Collection of England; there will be two more, or at least two, in the Münich, London and Berlin paintings, which we will analyze later. It's as if Pierre-Paul could only represent himself with his brother Philippe, born like him after the Siegen episode, and with whom he would remain linked for the rest of his life, to the point of making him his executor after his death.

.

Figure 14: Piero di Cosimo, The Discovery of Honey, Worcester, Massachusetts, The Worcester Art Museum

On the other hand, Piero di Cosimo's satyress breastfeeds while looking at her satyr companion. The moment of discovery of the honey brings together all forms of enjoyment: maternal and conjugal, oral and sexual, erotic and gustatory. In Rubens' work, on the other hand, the representational device establishes a differential system that radically opposes the circular jouissance, closed in on itself, to the sexual jouissance. /// herself, of the filthy mother with her children, and the sexual enjoyment from behind of the molested Silenus.

While Silenus-Bacchus, caressed a tergo by a pretty, creamy-skinned fawn, staggers up left, the milk-drunk satyress sprawls down right with her offspring. On either side of the black hole of the enigma, where the image of jouissance designates the presence of forbidden knowledge, Rubens differentiates and separates the father's two wives, the one for pleasure and the one for motherhood, Anne de Saxe as a white young woman and Maria Pypelinckx as a slumped, lactating pink satyress. The primitive aggression and bonding motif seemed to have been concealed, but the primitive scene manages to express itself differently, organized as an antithetical couple. In the top right-hand corner, the voyeur's place is not forgotten: Rubens has portrayed himself not as a child, but as a satyr. His exteriority is integrated this time he's almost part of the party : to laugh at the gods is to become a god oneself.

Figure 16: Rubens, The March of Silenus, 1618, Munich, Pinakothek

But the play of antitheses doesn't just work between the two female figures. Anal pleasure is itself represented twice as the father's pleasure: on the right, Silenus and her white satyr; in the center, the black woman and the goat-foot redouble the same device and invert it at the same time, as if the initial configuration, that of the molested father, tended to turn inside out. Here the doubling of the father figure, both a black figure of virile superpower and a castrated master, comes to the representation.

If we date the drawing of Silene and Eglé from the period immediately following Rubens' Italian sojourn (1608-1615) and if we consider that the Bacchanale in the Pushkin Museum (1615-1617)7 realizes the painting sketched in the drawing as an exit, or more precisely as a displacement of the primitive scene too brutally expressed by it, La Marche de Silène which is in the Pinacothek Münich (1618) constitutes the third stage in the process that, from the terrifying face-off imagined between Silenus and Aegle would gradually lead Rubens to the quintessential, modified and appeased representation of his personal myth, of which the Stockholm diptych, executed after Titian, is the culmination. La Marche de Silène takes up the elements of Moscow's Bacchanale, displacing and, above all, condensing them. It connects what had hitherto been disjointed on either side of the representation's horrifying central hole, the staggering procession of Silenus on the one hand, the lactating, scabby satyr on the other, or in other words, jouissance and maternity, Anne's side and Mary's side. Silenus supported by a faun on the left and a black man who grabs him from behind on the right, pinching his thigh, stumbles over the heaped-up, sated flesh of the dazed satyress who with her left hand caresses the sex of one of her sleeping children.

From the body of the /// father, woman's gender

The homosexual violence of the scene shouldn't fool us here it's about something other than a fantasy of anal penetration, which blurs what is repeated and obscured at the same time. The Ethiopian of Sodom comes to representation through the displacement and inversion of the black woman in the Pushkin Museum.

The Ethiopian of Sodom comes to representation through the displacement and inversion of the black woman in the Pushkin Museum.

Figure 18: Julius Romain and workshop, Le Banquet noble, circa 1526-1528, Mantua, Palazzo del Te, Hall of Love and Psyche

Rubens may also have been indirectly influenced by the Bacchanalian model offered to him in Mantua by Julius Romano's fresco of The Noble Banquet in the Salle d'Amour et de Psyché in the Palazzo del Te. Here, Silenus is shown seated on a stool, a goat between his legs and holding his donkey by the bit, while behind him a negro holds a white dromedary by the bridle. Silenus embraces a young satyr with his left arm. To the left, a young man with long blond hair crowned with pampers and dressed in animal skin probably represents Bacchus. At his feet, a pair of tigers are lying down, annoyed by a satyr. All the elements of Ruben's allegorical Bacchanalian material are present in this fresco. Between the Negro and the cute goat-foot, Rubens was able to condense the homosexual allusion, perceived as part of the god's attributes.

Figure 19: Detail of Silene and the Negro

Rubens' Ethiopian is both the flip side of the castrated master, an ominous shadow of the father's virile power, and the flip side of the princess hetaera of the primitive scene. Turning back to a pretty, chubby, pink Flemish girl, he enjoys vicariously and pairs up with her, a two-headed figure of the niger and the formosa.

The outraged Silene lowering his eyes, falling, expresses the denial of jouissance, the same central black hole around which the Bacchanale in the Pushkin Museum was articulated. He is the god we laugh at, that is, both the mystery and the negation of what, above him, the laughers in the procession share : the connivance of a certain built knowledge, leaning on the castrated master. But the fallen god doesn't fall into nothingness. From sex, he moves on to the white flesh that lies in a heap on his path his fall brings him back to the mother. For the first time, Silenus is at the center of the representation, articulating in his fall the two symbolic instances, behind him the phallic instance of jouissance, and before him a new instance, from which the Rubenian creation will be built, an instance made of flesh and whiteness that will gradually detach itself from the abject horror of maternity. For there is much more here than an imaginary regression to archaic femininity behind the satyr stands Maria, and with her, returning, sublimating primitive abjection, the celebration of conjugal virtues (Rubens painting himself with his wife, the family garden and children), the Catholic faith and the fight for peace, which constitute the three great discourses of Rubenian painting.

.

The point of articulation of the two /// symbolic instances is Silenus' sex, or rather its absence beneath the thin leaves of the pompom that conceals it, this shadowy zone structurally playing the same role as the black flesh of the black woman's body in the Pushkin Museum's Bacchanal. This is the point of scopic neantization that the child on the right, redoubling the viewer's curiosity, rises to distinguish. Phallus-less Silenus seized a tergo embodies through his negativity of fallen god, castrated and sodomized master, the sex of woman, while, through a displacement and inversion identical to that which articulates Silenus to the Ethiopian, the satyr on the left with his horns, bawdy laughter and hairy legs, conceals beneath his abundant clusters of ripe, gorged grapes the phallus here absent.

The upper figures, arranged in a homogeneous horizontal band, symbolically alternate masculinity and femininity: from left to right, the muscular flute-player, the horned satyr and the negro represent virile power; alternating with them, the old woman, Silene and the pretty bacchante represent femininity. This interweaving is matched by the skilful intertwining of the legs, so that the composition of the painting could be defined not as a frieze, but as a braid.

.

It may seem contradictory to identify the Negro sometimes with the black woman of Moscow's Bacchanal, i.e. with the very mystery of feminine jouissance, and sometimes with the virile power that blossoms with joyful aggression in the bestiality of the Dionysian rut. Similarly, it's somewhat disconcerting to see Silenus successively depicting the derision of the father and the gaping animality of the female sex. But condensation and displacement do not, as in the allegorical fixation of meaning by a stable system of figures and attributes, produce univocal and irreversible representations, which we would have to consider from one painting to the next as if the invested device of the primitive scene and its screens did not continue to work within the work itself, in networks, multiple paths where semantic bifurcations are possible. The figures only make sense in the network in which they are caught: first, as in the drawing of Silène and Églé, there is the descending diagonal that, from the right to the left of the painting, runs from the negro and the bacchante to Silène, then from Silène to the satyresse, to signify the father's position between the two experiences of female otherness. Then there's the upper horizontal braid of heads, where the alternation of the sexes is immediately signified by the interplay of light and shadow : the dark nape of the flautist's neck turned away, then the old woman's white scarf, then the old faun's dark, coppery face, then the white shimmer of Silène's advancing shoulder, then the Ethiopian's retreating into the shadows, then the luminous Bacchante's advancing movement, whose satiny shoulder is enhanced by the white kerchief of a second old woman. Here, it's another network, a second device that makes sense in a different way, recovering figures already in use to invest them in a new configuration. With this joyful braid, we're already out of the horrifying scene that obliquely barred the picture. The woman's sex is represented in the father's body, framed by the two phallic figures of the Ethiopian and the satyr. Rubenian femininity thus appears as a secondary elaboration, as the sublimation of what, from the horrifying vincla in which the father of the primitive scene is caught, emerges as the black hole of jouissance, as the knowledge of the castrated master, which will come to both tell and veil the white flesh of the nymphs.

Parallel to this process that constitutes the flesh of /// Rubens as a symbolic texture of knowledge, what is woven into the March of Silene is both the strong affirmation of sexual difference and the construction of a social bond uniting young and old, fauns and men, slaves and free men in the feast : we find here the very old motif of Dionysian social (con)fusion. But what's important is not so much that Rubens returns to the essential mythological stakes of the Bacchic cult it's that, through painting, he turns the primitive horror of the scene of the fallen father into the braid of the social bond. The transition to the symbolic order does not take place through castration, but, faced with the spectacle of the castrated father (the father, not the son), through the reversal of maternal abjection. The mother is the obstacle where the fall stumbles, the flesh and spring of the reversal, of the revolt. Her arms, her breasts entangled with the bodies of the satyrs prepare the braiding device below, which is organized above, while the small penis she caresses recovers and relaunches the function of the phallus.

Figure 22 : Rubens, Bacchanale, catalog of works presumed destroyed in May 1945 in Berlin, n°776B

After this March of Silene, the abject mother disappears from Rubenian painting, or at least manifests herself only indirectly, mediated by allegory or myth. Rubenian painting turns, revolts this raw material, this heaped-up maternal flesh, to create these luminous, desirable female bodies, these plump, divine beauties that would earn him fame from the 1620s onwards. A ban is lifted, a disjunction is undone, as if the function of the father, this instance of separation, of the splitting of the feminine, were temporarily inhibited.

A second version of the Marche de Silène was once preserved in Berlin, but has disappeared, probably destroyed during the Second World War. Max Rooses, who believes it to be partly in Van Dyck's hand, dates it approximately to 1620. The satyr has disappeared and the composition has split into two scenes: on the left, we find the old Silenus pinched a tergo by a negro, while on the right appears a young satyr embracing two women. One of them is a beautiful blonde bacchante playing the tambourine; for the other, who is brunette, Rubens had his wife Isabella Brant pose. This second scene reverses and sublimates the primitive scene : Rubens appropriates it ; painting his wife as a bacchante, he takes the place of the father as he makes the maternal figure disappear.

A division then emerges between, on the one hand, the young satyr with the two women, who recovers and idealizes the primitive scene, and, on the other, the old Silenus molested by a negro and a satyr, who parodies and detaches this same scene through derision : either laugh at the gods and thereby get rid of them, or be the laughter of the gods, be : such seems to be the alternative Rubens proposes to himself.

Figure 24: Rubens, Bacchanale, London, National Gallery

It is possible to follow the process of /// sublimation, which is then triggered by a third version of the March of Silene, now in London's National Gallery and attributed to Rubens' workshop, for reasons that are probably more moral than aesthetic, as pleasure is displayed with insolent exhibitionism8. The different framing of the scene, which makes the characters' feet disappear, once again obscures the breast-feeding satyr in the foreground. As if to reunite the scene, the young blonde bacchante from Berlin reappears on the left, holding a bunch of grapes in her upraised right hand, in front of Silenus' averted face, which shrinks from view. We are reminded of the gesture of Aegle smearing juice over Silene's drunken face, in the drawing in the Royal Collection of England. Here again, Silenus is caught in the crossfire.

But the aggression has turned into the pacifying, almost ethereal movement of the dance to his left while the protagonist of the coïtus a tergo, to his right, substitutes the disquieting, mysterious figure of the black man with a mouth open to the jubilant cry of a bearded man, perhaps a satyr, whose eyes lost in vagueness express the moment of orgasm.

On the right, a satyr embraces an old woman with a lascivious lingual kiss. Silenus catches the grapes handed to him by the two children, as if all the sons' work consisted in restoring, or at least supplementing through artistic production, the phallic power compromised by the father. And so, in a reversal of the primitive scene, the jubilant power of the sexual act is externalized and liberated, at the very moment when flesh is lightened and Rubenian flesh invented. The young Bacchante picking the grapes squeezes the juice like the Aegle in the London drawing. Yet the arm stretched out towards the father is no longer one of aggression, but of dance, as if the bacchic ritual, with its apparent disorder, were intended to regulate and calm the relationship with the feminine. Silène no longer falls forward, no longer bumps into the mother he lets himself slide backwards, he slumps voluptuously.

From phallic father to devouring father : symbolics of the flesh

From Hercules to Silenus, the deconstructed Oedipus

Figure 26: The March of Silenus, Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Schloß Wilhelmshöhe

Figure 27: Drunken Hercules supported by a faun and a fawn, (1601-1608?), Gemäldegalerie, Dresden

This slouching position behind London's Silene, between man and woman, echoes the device of an early painting by the painter depicting Hercules drinking supported. by a fauna and by afauna. This painting, now in the Dresden Museum, was commissioned by Duke Vincent de Gonzague during the young man's stay in Mantua (from 1601). /// Hercules appears staggering, supported by a faun and a faunette and allegorically figures the hero succumbing to his evil passions, intemperance and voluptuousness. Yet the Hercules drunk was painted with a counterpart, also preserved in Dresden, depicting the Vertu triumphant. Here, the demigod victoriously crushes drunken Silenus, while a winged Victory, on the left, crowns him. On the right, Venus sullenly contemplates the triumph of her rival, seated from behind. Leaning against her, Cupid plays the role of disgruntled child. Above them both, Envy, modeled on Giotto's, swallows a snake. Did the two Hercules painted for the Duke of Mantua already designate, behind the two father figures, the two modalities of the feminine and the two symbolic instances ?

Figure 28: Rubens, Virtue Triumphant, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden

It is above all in the Vertu triumphant that we are tempted to read, once again, the father between his two wives ; in Cupid, the rebellious son ; in Envy, the son's doubling, his suffering as a child swallowing the snakes of paternal adultery. But Hercules seems to function as a figure of identification, trampling underfoot the paternal : the clear configuration of the primitive scene has not yet settled. The emphasis is placed, banally, on the Oedipal revolt and the establishment of the moral law through the murder of the father.

Figure 29: Rubens, A hero crowned with victory, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum

In Berlin's March of Silen, the two scenes of the Mantuan diptych are integrated into a single composition, whose moral articulation is completely reversed : the scene of triumph is the scene where the prerogatives of jouissance are displayed, while the scene of derision indexes, not vice directly, but the father and his law. By replacing the triumphant Hercules by the drunken Silenus, and in the Munich version the crushed Silenus by the breast-feeding satyress, Rubens relegates the theme of castration to the background to highlight the ambivalence of the father and the double articulation he embodies between the two feminine principles of the symbolic, seduction and maternity.

Silenus, the father, is the father and the father's law.

Parallel to this transformation of the phantasmatic core, Rubens produced several paintings depicting Diana asleep, surprised by satyrs9 : the gender relationship in the primitive scene, marked by the father's rape, is reversed in the very moment when the son takes the father's place. The faun no longer surprises the molested father, but the virginal white beauty of Diana and her nymphs. In Le Repos de Diane de Münich, the representation of the female body becomes idealized, the flesh beneath the lifted veil almost vaporous, contrasting with the remains of the hunt brutally exposed at the front of the stage. The transfusion of the dark, dead flesh painted by Jean Brughel de Velours into the satiny, delicately sleeping flesh of the four resting women is clearly articulated here.

The return to the Italian model

The path we have sketched from the Antwerp drawing to Berlin's Silène leads us to propose, entirely conjecturally of course, the following dates for the works we have so far considered :

| Title and current location of paintings | Summary analysis | Dating? |

| Hercules ivre and La Vertu triumphant, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden. | Commissioned by the Duke of Mantua, Italian period, Oedipal configuration. Diptych : the scene is not yet unified. | 1601-1608 |

Drawing of Silene & Eglé, Antwerp, Stedelijk Prentenkabinett.

| Highly drawn contours, masculine woman, characteristic of the Italian period and immediately after ; stage set-up, but there's still only one woman. | 1608-1610

|

Drawing of Silene & Eglé, private collection of the Crown of England.

| Crystallization of the primitive scene, the father between his two wives, the configuration is no longer Oedipal. | 1610-1615

|

Bacchanal, Pushkin Museum, Moscow.

| Functionalization of the father's two wives ; the enigma of female jouissance is placed at the center. | Before 1617, (Allegy of the view) 1615 ? |

La Marche de Silene, Munich, Pinacothèque.

| Scene unification, father stumbles over mother. Accentuation of the staging of the father as master cheater. | 1618

|

Bacchanal, destroyed in Berlin in 1945.

| Displacement of the two bacchantes around a young satyr who is not drunken Silenus. Scene doubling. The son assumes the father's two wives. Appearance of Isabella Brant as a bacchante. | 1620s, probably before 1626, date of I. Brant's death. |

Bacchanale, London, National Gallery.

| Disappearance of the figure of abject maternity. The Bacchante who holds out her hand is no longer a horrifying Aegle, but a seductive young woman. Externalization of the sodomite's pleasure. | 1627 (Max Rooses dating)

|

Evidently, the date of 1627 for the Bacchanale in London is not indifferent, since it comes after the death of Isabella Brant and before Rubens' second married life, which his marriage to Hélène Fourment opened in December 1630. Rubens thus legitimately fulfilled his father's desire in time. He too will have loved two women, but without adultery.

It is as if the possibility offered to the painter by circumstances to take on, actualize and legitimize his father's double desire through a second marriage triggers a process of sublimation, the premises of which we have identified in the Bacchanale in London, but which is fully realized. /// in a return to the Italian model of the bacchanal, provided by Bellini and Titian. Jeffrey M. Müller has shown that the two copies after Titian of the Triumph of Venus and theBacchanale of Andrians currently housed in Stockholm's Nationalmuseum, could only have been painted after 162610 : they are therefore very much part of the movement initiated by London's Bacchanale.

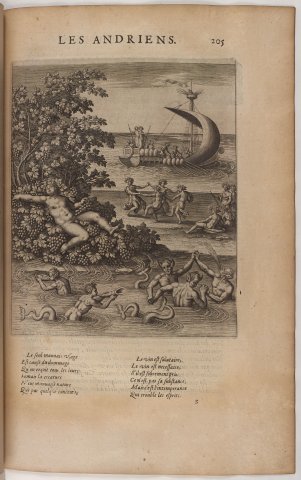

Figure 30: Les Andriens, engraving from the Images ou tableaux de platte peinture des deux Philostrates, mis en françois par Blaise de Vigenère, Paris, 1614

A detailed study of Titian's paintings as they were arranged in Alfonso d'Este's cabinet between 1518 and 1519 as a counterpart to Bellini's painting, itself probably retouched by Titian in the 1520s, would take us away from our object. Suffice it to note the shift from the textual model provided by Philostratus, from the depiction of drunken Bacchus sipping his wine slumped in the bunches of grapes to the representation, in the foreground, of the dazzlingly white body of a beautiful sleeping nymph. This shift is striking if we compare the engraving of the Andrians that appears in the 1614 edition of the Images or tableaux de platte peinture with the enigmatic representation offered by Titian. This comparison, which makes little sense for Titian because of the anachronism, is on the other hand revealing for Rubens, who may very well have made it.

Figure 31: Titian, Bacchanal of the Andrians, Madrid, Prado Museum

Titian seems to have painted his Andrians as a counterpart to Bellini's The Feast of the Gods in Alfonso d'Este's cabinet. Her bacchante responds to the sleeping goddess already featured in the lower right of this painting. In fact, a group-by-group comparison of all the elements in the two paintings would almost be possible, right down to the upturned satyr on the left of the Bellini, which is answered by the Silenus drinking from the front on the left of the Titian.

Figure 32: Bellini, The Feast of the Gods, 1518, National Gallery of Art, Washington

The logic that presides over the composition of Titian's canvas is therefore not a purely textual logic : it's not just a matter of putting Philostratus' ekphrasis into image, but of responding to the device offered by Bellini, of integrating a heterogeneous discourse into a pre-existing iconic device.

This double constraint of text and iconic device probably explains the relegation of /// Drunken Bacchus in the background of Titian's canvas, on the right like the Bacchante, reclining in the opposite direction as if to better respond to her. Yet, although it passes almost unnoticed in Titian's overall composition, this detail of the canvas constitutes its essential tipping point it is the punctum by which textual logic is turned on its head here and subverted into iconic logic.

Figure 34: Attributed to Bertoja, Bacchanale des Andriens, cliché Matthiesen Fine Art Limited, London

Bertoja makes no mistake, taking up after Titian the theme of the Andrians, who arranges Bacchus on a second plane parallel to the bacchante of the first : the space of the scene, circumscribed around the drunken god by the path in front and the rock behind, is the space of the signifier, to which respond, on either side, in the foreground and background, the floating and dancing of the signified.

Rubens does not enter into this semiological logic that isolates and cuts off the scenic signifier.

Very boldly, even as he seems to have scrupulously reproduced Titian's arrangement of figures in the foreground, he makes the drunken Bacchus in the background disappear, for which he substitutes a flute-playing shepherd, seated with his dog in the shade of a grove, among his sheep.

In the same movement of allegorical deconstruction, Titian's character who, at the end of the ephebe cupbearer's arm, changes water into wine or mixes wine and water under the curious gaze of his dog becomes, in Rubens, a simple angler.

As for the boat with its white sails inflated by the wind, which in Titian's work signifies Bacchus' arrival by sea, in Rubens' work it is replaced by two boats tiering the planes, opening up the depth of field and indicating the vanishing line. Narrative has become landscape, history painting has slipped into pastoral11. But the rubenian shepherd's comparison with the Silenus of Virgil's sixth eglogue seems more significant. What is represented here is the moment when drunkenness is transmuted into bucolic song, the eviction of lower pleasures, the passage from pure wine to pure music. Rubens continues to play on the correspondence established by Titian between the bacchante in the foreground and the background. But it's no longer a question of articulating Bellini's device to Philostratus's ekphrasis.

The Song of Silenus-Bacchus12 is here identified with the white, wispy flesh of this ecstatic Bacchante (her bug-eyed face and frothing mouth differ radically from the delicately asleep pose imagined by Titian), which is superimposed on him. The Bacchante takes the place of the drunken Silenus, and the Rubenian flesh is constituted by the incorporation of the molested father, just as Pierre-Paul is about to play out, in his own life, the moralized version of the horrifying fantasy. Flesh is the pacified screen of the primitive scene.

Figure 39: Rubens, The Andrians, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum

Rubens' transformations of the Triumph of Venus are less spectacular. The scene imagined by Titian is also taken from a ekphrasis by Philostratus, and the presence of the statue of Venus and the bacchante with the outstretched mirror on the right of the painting indirectly recalls, once again, the device instituted by Bellini. The female figures on the right contrast with the messy scene of assembled putti, just as the reclining bacchante contrasted with the Andrians' wine-filled revelry. Titian had played on the symbolism of fruit, decorating Les Andriens with grapes, symbol of Bacchus, while Le Triomphe de Vénus was strewn with apples, emblems of the goddess of love.

Figure 40: Titian, The Offering to Venus, Madrid, Prado Museum

Figure 41: Rubens, The Feast of Venus, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum

Rubens, once again, blurs the allegorical decoding by mixing grapes and apples in the foreground fruit basket. Bacchic and venereal pleasures merge.

In the sky, he adds Apollo's chariot pulled by swans, and behind the statue of Venus, a Triton, recalling her marine birth. Moreover, the background is no longer a plain, but a bay bathed in calm waters: as in his version of the Andrians, where the river in the foreground allows him to exploit a whole play of reflections absent from Titian, the liquid element wins out here too. Between the airy Apollo, who here seems to endorse the worship of Venus, and the group of women below, the same echo is established as between the sleeping Bacchante and the figure in the background, a musician shepherd or drunken Bacchus. Apollo's chariot is pulled by two swans the statue of Venus is surrounded by two women : it's trio against trio.

So, the device /// The outstretched arm of the woman at the mirror13 becomes even longer in Rubens, as if to recall Aegle's aggression, which here becomes a feminine call of desire. In both Rubens and Titian, the red dress of the disheveled woman contrasts with the blue dress of her upturned companion, who holds a small object, probably a book (Venus inspires poets). But in Rubens' work, the woman in red is not looking at Venus or the mirror she's holding up: Apollo is in her sights. With his two swans in the sky, he represents the father between his two wives, whose divergent relationship to desire, in the foreground, is indicated by the divergence of their gazes. Between the god on his chariot at the top and the two women below, the statue of Venus forms a screen, supported by an undulating fish which, with its exorbitant gaze, offers an exact counterpart to the outstretched mirror, as if to redouble the figuration of the female sex. Between the master and his two wives, the enigma of feminine pleasure forms a screen not as an obstacle, but as a game of seesaw and metaphor. The mirror reflects a dark color which, given its position, can only be the color of the blue dress: to love one and enjoy the other? The master's knowledge opens the door to an ideal, molten, nimbed jouissance. Thus displaced, divinized and distanced, the father ensures the fusion of the two women his fault opens to the legitimacy of double jouissance he is the covered substratum to which female flesh screens.

Figure 44: Rubens, The Feast of Venus, oil on canvas, 217x350 cm, Kunsthistorishes Museum, Vienna

It's as if the painter always tended to bring his subjects, his scenes, his devices, back to the matrix bacchanal, to the stage-screen from which his art crystallized. The second version of the Triumph of Venus, probably painted in 1637, is characteristic of this inflection. While Venus is refocused and more explicitly placed in the maternal position of the Venus pudica, Rubens adds a bacchic dance in the lower left foreground. The motif of the envelopment of the female body becomes the general motif of the composition : wrapping the statue of Venus in a long veil, a tergo embrace of the satyr and Bacchante on tambourine on the left, farandole of putti surrounding the statue, farandole of satyrs and bacchantes in the background on the right, each body tending to cover the other ; not even the arrangement of a canopied curtain in the tree, the temple dome on the left, the ruined bridge beneath which the waterfall spills, underline the motif of envelopment.

It's not just here, on a very general level, the dynamics of representation, its feminine beyond, the interposition of the screen and the work of unveiling that are at stake. The outstretched arm that envelops is the arm of primitive aggression, transmuted into a dancing gesture; the embrace from behind inflicted on the raped father is sublimated here into the drapery of night laid over Venus's marmoreal flesh.

Behind the flesh, the other father

So, the female body, in Rubens, is not a primary datum of his painting it is not the brutal giv-à-voir of the colorist imaginary that would oppose the symbolic devices of drawing. Ruben's flesh is the idealized product of a reversal of the primitive scene around which he built his work on his return from Italy. It opens painting up to a new type of allegory, whose coding system and ideological aim are neither those of the rhetorical-moral game of phallic semiotics. Something else /// is at stake.

Figure 45: Rubens, The Feast of Tereus, Madrid, Prado Museum

It's as if the relationship with the father, visibly central to the Rubenian imagination, was translated on canvas by the painting of female flesh, as if Silenus molested produced the white flesh of the nymphs. Here, it's not the son's castration or Oedipus' gouged-out eyes that trigger the semiotic break and symbolization. In the process of creation, the son's impossible gaze, his revolt and the materiality of carnal texture coincide. This relationship of flesh to the primitive scene awakens several other myths in the Rubenian imaginary.

First, there's the story of Philomela and Procne, evoked in Virgil's sixth eglogue and depicted by Rubens on one of the canvases commissioned by Philip V for the Torre de la Parada, in 1636.

Tereus had raped his sister-in-law Philomela, biting out her tongue to silence her. Philomèle nevertheless instructed her sister Procnea, Tereus' wife. In revolt, Procne killed her own son, Itys, and fed him to her husband. In Ovid, the gods, tired of these continual cruelties, changed all the protagonists into birds, Tereus into a sparrowhawk, Philomela into a nightingale, Procnea into a swallow.

But it's not the moment of metamorphosis that Rubens has focused on. At the end of the terrible meal in which he ate his son Itys, the king of Thrace is depicted on the left, seated on a banquet bed under a canopy. Overwhelmed by the horror of what lies before him, he tips over the round table, the crockery and the reliefs of the feast. Before him, in the center, Procne dressed as a bacchante - a tiger skin can be seen around her waist - presents the horrified king with the child's livid, dripping head on her outstretched hands. Behind her, holding back her sister's ardor with her right hand resting on her shoulder, Philomèle, whose open black mouth reveals her missing tongue, has also donned the bacchante garb: in her right hand, behind her as if to conceal it, she holds the bacchic thyrse. The background depicts palace architecture. Between Tereus and Procne, i.e. between the two legitimate spouses, a door is open and a young man observes the scene surreptitiously.

This referentless intrusion into the myth can be technically justified it's common practice in classical painting to place a voyeur spectator behind the scene, to give it depth and at the same time to metaphorize and integrate the off-screen gaze of the real spectator facing the painting. The process is commented on by Diderot in the Salon de 1767 in connection with Lagrenée's Suzanne et les vieillards, and makes /// the subject of a lengthy analysis in Michael Fried's La Place du spectator.

But the Bacchic transvestism of the Ovidian scene, the depiction of the horrified father between his two wives, the superimposition in the pictorial device of the spectator-viewer and the decapitated son allow us to advance the hypothesis that here again the primitive scene of the molested father constituted the structuring imaginary core of the composition as a whole, especially if we pay attention to an architectural detail in the background which in our opinion serves here as the signature of the link : the cherub above the door is placed in the very position of the Silenus of the screen-scene, his left leg raised forward as if to take Aegle's place, to evacuate her, to effect the movement her presence blocked.

Rubens, at the same time, painted a similar putto in Vienna's Fête de Vénus : we're struck by her constrained face, this gesture of the left hand to escape her companion's grip, and the movement of the left leg, incomprehensible in the stone angel of the Festin de Térée, takes on its full meaning here : the putto refuses to be tackled to the ground, seeks to recover. The light-hearted mode of children's play, the amiable horseplay on a party lawn could once again cover the evocation of the father's rape. Through painting, the resisting limbs take their revenge, the child takes the place of the master while the intruding woman is covered over, definitively substituted by the revolting leg.

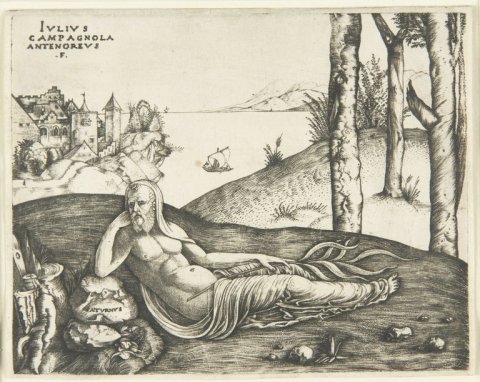

Figure 50: Giulio Campagnola, Saturn, 15th century

However, under the figure of Tereus, the father here reveals a new, less advantageous face. By devouring his son's body, he has reduced him to the pure voyure of a mortified, impossible gaze : the son's gaze on his own head, once his trunk has been ingested.

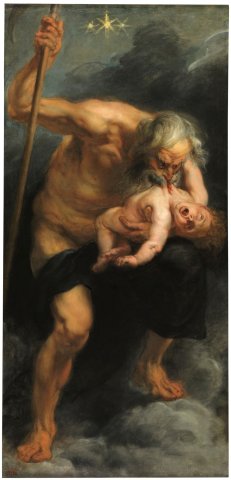

The molested father thus covers another father, no longer horrified, but horrifying, no longer Silenus molested, but Saturn devouring his children. Indeed, E. Panowski has shown, in Saturn and the melancholy, how the figure of the old man reclining, leaning, the very one that represents Silenus in the drawing of Silenus and Eglé, had been used to represent Saturn, the god of time, identified with the Greek Cronos who devoured his children.

Figure 51: Piero di Cosimo, Les Mésaventures de Silène, c. 1505, Cambridge, Fogg Art Museum, Massachusets. Detail at bottom left of painting: Silenus stung by bees is treated with mud compresses

Just compare Giulio Campagnola's Saturn14 with Rubens' Silen, itself perhaps inspired by Piero di Cosimo's Mésaventures de. /// Silene the same gestures are used on the hairless face of this androgynous body with oily flesh, right down to the detail of the two children playing at her feet. But what in Piero di Cosimo was intended as a soothing gesture, a mud plaster delicately applied to a face swollen by bee stings, becomes in Rubens aggression and derision.

.

Figure 52: Rubens, The Four Continents, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, 1615-1616 ?

Piero di Cosimo's Silenus, chubby, round and smooth like a woman's body, here interferes with the angular, disquieting figure of Saturn, or rather of the Greek Cronos, whom Hesiod calls P { margin-bottom: 0.21cm; }ἀγκυλομήτης15, the god of the curved half-breed, the mind adept at twisted tricks. Campagnola had imitated, for his leaning old man, an ancient river divinity carved on the triumphal arch at Benevento.

Figure 53: Rubens, Saturn Devouring His Children, Madrid, Prado Museum, 1636

This figure is also to be found in Rubens' depiction of the four continents, now in the Kunsthistorishes museum. This time, the old man in the foreground is from behind, but he's holding a black woman in his arms, and in the foreground, without solid allegorical justification, is a tigress nursing her two cubs, a synthesis of the lactating satyr and the bacchic tiger. The Four continents take up all the elements of the primitive scene, but here the figure of the molested father slips into the fourfold representation of the melancholy Saturn. Beyond the more or less serious allegory of the continents, this is one of the innumerable combinations Rubens attempted, in the years 1615-1617, to represent the same primitive scene.

Figure 54: Ganymede and the Eagle, c. 1611-1612, oil on canvas, 203x203 cm, Schwartzenberg Palace, Vienna

Around the same time and in the same vein, Rubens painted an enigmatic Enlèvement de Ganymede, where the smiling young man, lifted into the air by the Jupiterian eagle enveloping him, reaches out to Hebe to take the cup of cupbearer, while in the background we can make out the banquet of the gods and its intertwined couples. Commentators have been puzzled by the significance of this painting: Ganymede does not resist his captor, unlike the Ganymede that Rubens would paint in 1636 for the Torre de la Parada ; there is not one but two women to figure Hebe finally, if young Ganymede's graceful wiggle was meant to suggest a benevolent allegory of pederasty, why are the divine couples, in the background, all heterosexual ?

Like the sodomite of the Bacchanales, the eagle here represents something other than the desire of the Same : it is the dark mystery of the jouissance that envelops the father whose outstretched hand returns, or takes up in reverse the outstretched arm of the primitive Aegle. Hebe is duplicated to match the scene with the archetypal device of the father and his two wives. Here again, Ganymede represents, through the unexpected staging of the father - eagle and ephebe, husband and lover, seducer and seduced - the mystery of the jouissance accomplished, at bottom, by the divine banquet, whose god in the foreground constitutes another Silenus, another river god, another Saturn.

Saturn's melancholy, as E. Panowski, is linked to a late avatar of the myth, in which Jupiter cuts off his father's testicles. The punishment inflicted by Cronos on his father Ouranos at his mother's instigation and described in the Theogony, was confused with the punishment inflicted by Zeus on Cronos. This confusion allowed the myth to be refocused on the Saturn-Cronos character, as evidenced, for example, by this presentation by Barthélémy l'Anglais :

" His name is Saturn of saturo, satiate. His wife is called Ops from opulentia, the abundance she bestowed on mortals, according to Isidore and Martianus. On the subject of Saturn, legend has it that he is depicted so sadly because it is imagined that he was castrated by his own son and that his manly parts thrown into the sea gave birth to Venus16. "

Hesiod describes the birth of Aphrodite on the sea off the island of Cythera from the foam of Ouranos' purses. Devouring Saturn thus becomes castrated Saturn, god of the Italic rivers and of the abundance of the Virgilian Saturnia regna, terrible and melancholy, furious and humiliated, barbaric and debonair.

The castrated master is also the devouring father, whom Rubens featured not only in Le Festin de Térée, but in a Saturn devouring hischildren. The flesh of the nymphs restores the flesh consumed by the father, a continuum is established from what the father absorbs to what the son deploys, from having been absorbed. Imaginary absorption couples with pictorial theatricality, not as a simple thematic or even structural pairing, but as a device of symbolic revolt, primitive introjection reversing itself into luscious exhibition, the horror of one's own devoured body becoming a pacified display of white flesh.

In contrast to Goya's Saturn, who devours his son's head, Rubens' Saturn, who nevertheless served as his model, devours his upper chest, heart and liver. Head and penis are preserved, sex is not directly at stake, but the very inner matter of the body, the vital substance of the entrails, the son's insides becoming the father's insides, as in a freely consented offering.

For this devouring scene, which belatedly superimposes itself on the primitive scene of the molested father, does not reveal the underlying truth of all pictorial screens. On the contrary, it reverses the primitive scene, providing it with the ultimate reparation. To the molested father, the painter son comes to bring the sacrifice of his very flesh, transmuted into the white flesh of the nymphs, as if all his painting, all this never-satisfied overproduction of producing, brought the humiliated, castrated father the supplement of his lost dignity.

It seems that the horrifying depiction of the father constitutes the latest avatar of the scene-scene that runs through Rubens' entire painted oeuvre. We've seen him in the form of Tereus and Saturn. He also appears as the war-mongering Mars, or, according to a similar device /// rigorously identical, in Pluto abducting Persephone, caught between his two wives, tearing himself away from one to disembowel or rape the other. The sublimation of female flesh has displaced horror towards the father figure, turned primitive aggression on its head.

Figure 56: Rubens, The Horrors of War, 204x345 cm, 1637, Palazzo Pitti, Florence (Max Rooses no. 827)

For the painting of the Horrors of the war, we have a description by Rubens himself, valuable for the hierarchy it introduces between the figures :

" The main figure is Mars who, coming out of the open temple of Janus (which in times of peace, according to Roman custom, was closed), walks with his shield and bloody sword and threatens the people with some great misfortune. He cares little for Venus, his beloved, who, accompanied by loves, strives with her caresses and kisses to hold him back. On the other side, Mars is pulled forward by the furious Alecto, who holds a torch in her hand. Monsters stand beside them, signifying Plague and Famine, inseparable companions of war. [...] This mourning woman dressed in black, with her veil torn, stripped of all her joys and ornaments, is the unfortunate Europe that has already, for so many long years, suffered the rapines, outrages and miseries that are harmful to everyone beyond expression. " (Extract from a letter to the painting's commissioner, Josse Suttermans, an Antwerp painter established in Florence for the Count of the Duke of Tuscany, March 12, 1638, quoted by Max Rooses)

In the multitude of characters, the description isolates the primitive triad, Mars caught between Venus and Alectô. The woman in black on the left merely doubles Venus.

Figure 57: Rubens, The Abduction of Proserpine, 180x290 cm, Prado Museum, Madrid

The allegory is directly linked to Bacchanalian scenes, as evidenced by the first version of the painting, offered by the painter to Charles II of England during his mission as ambassador for peace with Spain, in 1629-1630. Mars is already caught between Alecto and Minerva, who becomes Venus in the Uffizi version, returning to Minerva in the Abduction of Proserpine. But the foreground still retains the circular layout of Moscow's Bacchanal. The tiger playing with the pampers recalls that of La Marche de Silène from Munich and Berlin and above all prefigures that of the Bacchus ivre at the Hermitage17. As for the bacchante with tambourine, on the left, it repeats a motif already seen in the Berlin painting.

Figure 58: Rubens, Allegy of Peace and War, also called Minerve Protecting Peace from War (Max Rooses, no. 825), oil on wood, 203.5x298cm. London, National Gallery

But the blissful idealization of the /// female figures, characteristic of the period immediately following Isabella Brant's death (one only has to compare it with the Stockholm paintings after Titian), gives way in the last period to much more tormented representations.

In Les Horreurs de la guerre, Europe figures alongside Venus as the longing, suffering mother. Europe, isn't this a way of representing the earth, this Gaia mother of Cronos-Saturn who hatch the castrating punishment against her husband ?

εἶσε δέ μιν κρύψασα λόχῳ- ἐνέθηκε δὲ χερσὶν

ἅρπην καρχαρόδοντα, δόλον δ' ὑπεθήκατο πάντα.

῎Ηλθε δὲ νύκτ' ἐπάγων μέγας Οὐρανός, ἀμφὶ δὲ Γαίῃ

ἱμείρων φιλότητος ἐπέσχετο καί ῥ' ἐτανύσθη

πάντη- ὅ δ' ἐκ λοχεοῖο πάις ὠρέξατο χειρὶ

σκαιῇ, δεξιτερῇ δὲ πελώριον ἔλλαβεν ἅρπην

μακρὴν καρχαρόδοντα, φίλου δ' ἀπὸ μήδεα πατρὸς

ἐσσυμένως ἤμησε, πάλιν δ' ἐρριψε φέρεσθαι

ἐξοπίσω- τὰ μὲν οὔ τι ἐτώσια ἔκφυγε χειρός-

" And she set it up, after hiding it, in ambush. Then she placed a sharp-toothed scythe in his hands and subjected him to the whole ruse. The great Ouranos came, bringing night upon him, and around Gaia, eager for love, he spread. She was surrounded on all sides. Then, to get out of his ambush, the son raised his left hand and with his right seized the huge, long, sharp-toothed scythe and his father's purses, slicing them off in one stroke, to throw them haphazardly behind him. But it was not in vain that they fell from his hand. " (Hesiod, Theogony, 174-182.)

Feminine flesh covers the scene-screen of the molested father insofar as the castrated master's knowledge of jouissance has to do with this mysterious envelopment : envelopment of the scene in the night, envelopment of the father around the mother, envelopment of the seed by the bursae. The father is the envelopment, which Rubens depicts in the circular composition of the Bacchanal of Moscow or the l'Allegory. of the peace and of the war, by the sodomy of Silenus, by the eagle of the Ganymede with outstretched wings, by the women who stick to warrior Mars or kidnapper Pluto, as if to become the father's skin. The father is the mother's hymen. From this position of envelopment, castration doesn't establish a cut, but tears the envelope, liberating jouissance and confusing the outside with the inside. It is revolt, that is to say, the turning inside out of the envelope, the opening up of the purse's hidden contents. The father's castration is the hidden, liberating formula of jouissance; it allows us to take his place in fulfilling our desire. Like Jupiter dethroning Saturn, Rubens liberates the father's fecundity by depicting him as a molested father. To paint flesh is to make the cut bursa of the devouring father whiten with foam, to make Venus spring forth from the scene-screen of the molested father.

The Last Bacchus

Rubens returned one last time to the depiction of Bacchus ivre in a painting now at the Hermitage. Bacchus seated on his barrel and treading on a reclining tiger is reminiscent of the /// Silene and Eglé from Antwerp18, while the urinating child to his left evokes the child of the Andrians.

Figure 60: Rubens, Bacchus drunk, c. 1635, St. Petersburg, Hermitage

In a way, this painting synthesizes the previous bacchanals and only makes sense in the differential relationship it has with them. The sodomite supporting Silenus has turned to drink, and the satyr on the left, instead of suckling his mother, gorges himself on wine. The Bacchante no longer faces Silene to offer her hand : leaning on her fat shoulders, she stands by his side, like a thoughtful young wife at the side of a sullen, aging husband. (She does not, however, have the features of Hélène Fourment, and Bacchus was painted on the model of the emperor Vitellius, not Rubens.)

Rubens has thus retained the essential elements of the device : in the center the figure of the father is surrounded at the top by his two acolytes for enjoyment, the bacchante in red on the left, the satyr turned upside down on the right. Below, the two children represent the inside and outside of ingurgitation-devouring, as one drinks, the other pees.

.

The latter adopts a position tipped backwards, unlike the Andrian model, leaning forward. Careful observation of the Andrians from Stockholm also reveals that Rubens has already slightly straightened the child there, whom Titian had painted with legs bent, stomach puckered. In the Bacchus at the Hermitage, he has returned squarely to the position of the drunken Silenes in Moscow and London : the son exhibits himself alongside the father.

For it is indeed in this series that we must read The Urinating Child. With or without wings, the putti are generally naked. Here, the raised or untucked shirt is part of the Rubenian dialectic of tearing and envelopment. Bacchus's fat, flaccid body does not refer, as S. Alpers imagined, to the sexual ambivalence of the flesh. He is the melancholy body of the castrated master, whose castration, like that of Ouranos-Saturn, turns into childbirth: the absence of the father's penis is made up for by the exhibition of the son's. He is the product of the tearing apart of the body, of the tearing apart of the body. The son's penis is the product of tearing, signified by the indentation in his shirt. Sitting on his barrel, the master sadly wraps his flesh around the secret of his pleasure, which is poured out by the child, as well as by the satyr above him, or the bacchante on the left. Urine and wine both metaphorize the secret of the barrel's contents, which is neither one nor the other, but the very seed of Saturn's purses.

This means that castration doesn't open up access to language, but to time, of which Saturn is the god ; or more exactly it marks the passage from indefinite time to cyclical, regulated time. The Bacchus ivre at the Hermitage, even more clearly than all the other bacchanals, which nevertheless generically fulfill this semantic function, signifies the harvest season, autumn, i.e. the return of the year, the closing of the seasons. Castrated Bacchus conjures Bacchic derangement, not by the castrating establishment of a Jupiterian law, but by the crystallization of the son's creative energy.

The Bacchus ivre can therefore be read as a /// recognition of filiation. Through him, ultimately, Pierre-Paul accepts and recognizes his father as the source of his inspiration, and identifies the figure of the creative power with that of the castrated master.

Conclusion

Analysis of a drawing from the Royal Collection of England depicting Silene, Églé and d'others figures has enabled us to identify the Virgilian scene of Églé assaulting Silène drunk and bound as the founding screen-scene of the Rubenian pictorial universe. Behind this screen-scene, we have uncovered the primitive scene that haunts the painter, the confrontation between his father and his two wives, his wife Maria Pypelinckx, and his mistress, Anne of Saxony, which almost led to his death.

Figure 62: Cornelis Schut, Drunken Silenus with Fauns and Bacchae, collaged drawing, brown pen and brush, with light wash highlights, 202x311.5 mm, Stedelijk Prentenkabinet, Antwerp

Rubens constantly revisited and reworked this screen scene over the course of his career. We have followed the avatars of the device thus constituted, both in representations of Bacchanalia directly linked to the theme of the primitive drawing, and in mythological paintings seemingly unrelated to the core of the primitive myth.

Rubens constantly took up and reworked this scene-screen over the course of his career.