Fragonard's bedroom

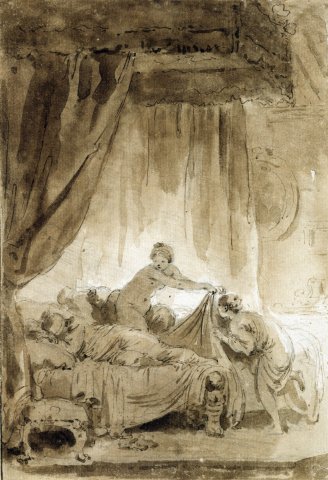

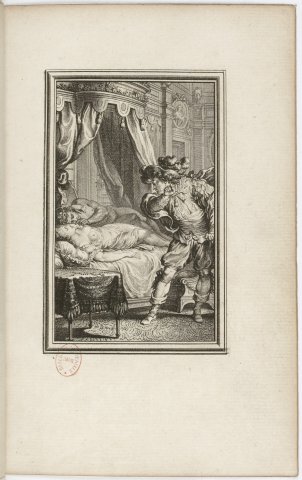

The bedroom is bathed in a soft yellow-ochre half-light, enveloped as if in a jewel case by the high brown bed canopy and its drawn curtain. In the bed, Astolphe, King of the Lombards, and Joconde, his companion from Rome, can barely be made out as they lie deeply asleep, sharing the innkeeper's daughter, Fiammette. Lying on the bed, careful not to wake them, Fiammette stands out against the lightest part of the wash, stretched between two opposing movements. On one side, to the right, she lifts the sheet: between the feet of the two men who think they're sharing her, she makes the agreed opening for a third man, "a young lad", says La Fontaine (v. 382), "Le Grec" specified Ariosto (XXVIII, 57), who is about to dive in to join her1.

Strange rendezvous, captured in a fragile, uneasy silence, arranged with the naive delicacy of a child's game where the young girl unthinkingly reveals her still-chubby nudity, where the young man, captured in the bird-like lightness of a furtive dive, appears a young girl. Yet there's nothing solitary about this silent intimacy: it's not just about Astolphe and Mona Lisa, the two sleeping masters. Behind the bed curtain at the far end, the oval of a vague portrait beckons as the virtuality of a spectator witnessing what is unfolding in the foreground. On the other side of the room, in the lower left, the footrest at the bedside, with its arched feet, also manifests, from the intimacy of things, a scrutinizing presence. Finally, between the two, emerges the fantastic silhouette of a carved footboard, feline paw, sphinx breast and dog's head.

Closed at the back, where it concentrates the dim light and offers the stage a surface to lean against, the bed curtain is open in front, and crumples carelessly over the footboard. Open like a theatrical curtain, it delimits the bed as the scenic space bordered by the inanimate eyes of the room: the picture, the carved footboard, the footrest. To this should be added, under the picture, a barely sketched still life with a pitcher, and, against the bed, a pair of slippers wisely aligned. Things border the scene, organizing, towards it, an a-subjective ocular convergence, a convergence of things that look, the vague "ça regarde"2 that, pointing from the semi-outside of what isn't in the scene, but stands nonetheless in the image, allows the most intimate heart of the room (not the room, but the bed in the room ; not the bed, but, in the middle of the bed, the place of fraud that escapes its sleeping edges) to be represented.

A whole device, then, allows us access to this intimacy arranged in history to remain unwitnessed. The scopic pressure of the vague space on the restricted space, the theatrical cutting of the curtain, the tension of the two protagonists' stymied gestures, symmetrically frozen between the back of fear and the front of consumption, turn the closed space of the bedroom into the open space of the stage, shift the private game of reaching (the Greek must reach Fiammette, the sheet is the medium of this reaching, an invisible affair of touching) and the public game of spectacle, with its codified arrangements, pyramidal composition, theatrical gestures, exemplary aim.

All Fragonard's charm lies in this tipping point that he never completes, that he subtly maintains at the silent edge of furtive play and theatrical action, between fraud and event. This shift, this edge, is only possible because Fragonard has two competing spaces, two possible logics of representation: on the one hand, the bedroom, with its secrets, its mysteries, its brutalities without witnesses; on the other hand, the stage, with its apparatus, its theatricality, the publicity of its speeches.

.Opening the room: storytelling solutions

The story of Mona Lisa, whose verse version given by La Fontaine is illustrated here by Fragonard, is borrowed from Ariosto, who most likely conceived it from the prologue to the Thousand and One Nights, either that he had direct access to this story, or more likely that one or more intermediate versions exist between the 13th-century Arabic manuscript that Galland would translate and the story in Canto XXVIII of Roland furieux.

At the beginning of the Thousand and One Nights, Shahzamane, king of Samarkand, is invited by his brother Shahryiâr, sultan of India and China, and sets off to join him. However, after setting up camp outside the city, he returns home to bid farewell to his wife, enters her room in the middle of the night, and finds her asleep next to one of the valets in her kitchen:

.At this sight, Chahzamane was stunned for a moment, so much so that objects lost their color to his eyes and everything seemed black around him3.

Furious, Chahzamane kills the two lovers and leaves without telling anyone. He is welcomed by Chahryiâr, who "owned a garden on the outskirts of which he had built two splendid palaces". The sultan and his wife stay in one, while the other, reserved for guests, is the home of Chahzamane, who, consumed by his secret, withers away, until the day when, while his brother is away hunting, he witnesses a singular merry-go-round in the garden adjoining the two palaces.

.Chahryiâr's wife breaks in through a secret door with twenty servants, half of whom turn out to be black slaves. The queen then calls Massoud, another black slave, who jumps from the top of a tree where he was hidden:

He put the lady's legs in the air, slipped between her thighs and entered her. So the ten fell on top of the ten while Mas'oud, for his part, fell on top of the lady. And they continued to have sex until the middle of the night. [...] All this took place before the eyes of Shahzamane, who never stopped watching the scene." (trans. Khawam, p. 39-404)

Chahzamane then compares his fate to that of his brother, reassures himself, regains his appetite and taste for life. On his return, Chahryiâr notices this change, forces him to reveal his double secret, and to be sure, asks to witness the scene that Chahzamane has surprised. He pretends to go hunting again, sits down with his brother at the same window, discovers the same spectacle and nearly loses his mind.

The two brothers then set off on an incognito journey, in search of someone whose misfortune would surpass their own. They find him in the person of an ifrite, a giant demon who wears a glass chest on his head, where he keeps his young wife locked up. The ifrite takes the young girl out to fall asleep on his lap. But no sooner has she fallen asleep than she calls the two travelers who have been hiding in a tree and beseeches them to sleep with her, or she will wake her husband to kill them. She then demands that they each give her a ring. After this ordeal, the two brothers return home and Chahryiâr begins beheading his wives.

This introductory narrative is organized around three decisive sequences in which we recognize the three key moments in Mona Lisa's story: like Chahzamane, Mona Lisa after leaving at Astolphe's invitation returns home and surprises his wife with a valet. But he doesn't kill her. Like Chahzamane, Joconde catches the queen mating with not a black slave, but a dwarf. Finally, the obligation for the two brothers to sleep with the ifrite's wife and give up their ring becomes the story of Fiammette, whom Joconde and Astolphe share after giving her a ring. The need to fornicate quietly so as not to wake the ifrite becomes the Greek's stratagem, fornicating between Astolphe and Joconde.

At first glance, these three sequences could be defined as three scenes: a woman and her lover "interact" under the gaze of a third party5; it's the gaze of Chahzamane or Joconde, then, in the third sequence, the sleeping presence of the ifrite, or Astolphe and Jodonde in bed, who could at any moment open their eyes. But once we resort to this kind of formalist reduction, the historical, Western emergence of the theatrical device of the stage, and the shift it makes from intimate matter to public space, becomes elusive. A certain scenic and impulsive efficiency of representation is at stake, which comes from the tale but breaks out of its narrative logic, which takes root in the most immemorial sources of narrativity, and at the same time breaks radically with them: this efficiency is at work in Fragonard's drawing, but foreign to the narrative of the Thousand and One Nights.

In the Thousand and One Nights, the first two sequences are clearly opposed: at the end of the first, the objects for Shahzamane "lost their color and everything seemed black around him". In the chamber, vision is impossible, for it is indissolubly linked to injury: to see is to be wounded, and ultimately, to see is to kill. The chamber deploys uncontrolled proximity; it encloses and unleashes brutality.

In the second sequence, on the other hand, the spectacle is made technically possible by the layout of the locations - a garden between the two palaces - and the arrangement of a vantage point: the window of the guest palace allows Shahzamane to see without being seen. But there's no voyeurism involved: the layout of the space accommodates a reasonable distance for the eye, to which corresponds a symbolic distancing; the queen is not the viewer's wife, and above all, by offering a choreographed amplification of what Shahzamane experienced in the hell of his own room in Samarkand, she objectifies and universalizes the intimate violation he underwent. The second sequence turns the attack, the abject, into an object; from a wound, it constitutes, from a distance, a representation:

.Giving himself over entirely to these reflections, he came to forget his worries and soon found consolation in his own misadventure. (Khawam 416)

The process described here by the tale could be identified with that of catharsis: unlike the first sequence, which is unique, this one repeats itself; this will be one of the characteristics of the classical Western stage, which will identify this repetitive mechanism with that of theatrical representation.

In the third sequence, the ifrite's wife surprises the two travelers:

She raised her head to the branches of the tree, regarded them with a watchful eye and spotted King Chahryiâr and his brother Chahzamane. She gently lifted the ifrite's head [which was resting on her lap], laid it back on the ground, stood up and, approaching the trunk, beckoned the two brothers noiselessly down to join her. (Khawam 507)

Here, the spectacle is short-circuited by the young girl's ruse, which pits her gaze against that of the ambushed traveler-seers. As we can see, the three sequences organize the progressive complexification of the scopic game: first, in Samarkand, no gaze; then, in the garden of Chahryiâr, the distanced accommodation of a spectator's gaze; finally, under the tree where the ifrite has fallen asleep, two gazes, towards and from the place of narrative focus, this time make it possible to fully exploit all the scopic potentialities of the tale's test-chamber.

Because this isn't just a scene: it's as an ordeal that the characters successively qualify each of these encounters. Chahzamane speaks first of outrage ("it's in this situation that I suffer such outrages", "at the mere memory of the outrage his wife had caused him"), then of "misfortune", and finally exclaims: "How is it that this ordeal, this extreme misfortune has befallen me, Chahzamane, despite the dignity of my rank8? " The same words, "outrages" (p. 41), "infortune" (p. 43, 45), "malheur" (pp. 44-45), "catastrophe" (p. 47) designate the second sequence. "Misfortune" characterizes the third (p. 52)9.

The three trials of the tale (the bedroom, the garden, the ifrite) arrange their representation from the space of the bedroom, which they decompartmentalize according to a principle of gradation and one-upmanship: Chahzamane surprises his wife in a bedroom; the garden, where he sees the queen mating with Mas'oud, is a sort of open-air bedroom, wedged between the two palaces; finally, the episode with the ifrite takes place outside any architecture, when the young girl is symbolically taken out of her glass cage. The fiction thus establishes, at the geometrical level, the junction of the nomadic space of the djinns and travels with the courtier space of the palaces and their rooms, which it superimposes, at the symbolic level, on the junction between the traveler's silence and the courtier's speech.

As we can see, the polarity of public and intimate is not operative here. Yet in Ariosto's appropriation of the Arab tale, this polarity becomes essential. And its emergence depends on the invention of a scenic device capable not only of implementing it, but, in a visual and immediately intuitive way, of figuring it: the invention of the modern public space and the invention of the stage are one and the same invention.

.The libertine partition: towards the stage

All three sequences in Mona Lisa's story, and not just the first, take place in a room: it's Mona Lisa's room for the first, the secret room where the queen receives the dwarf for the second, the inn room for the third.

The first is delivered to us without mediation. It is not even named in Ariosto:

He goes down to his house, goes to bed, and his wife

.

He finds her there sound asleep10.

Chez La Fontaine,

He goes up to his room, and sees near the lady

A clumsy valet on her outstretched bosom11.

The second chamber is only opened up to the viewer's gaze by means of a disjunction in the partition:

At the back of the room, where it's darkest,

(because it's not customary to open windows),

he sees that the partition doesn't fit the wall properly,

and leaves

and lets the ray escape with a clearer look.

He puts his eye to it, and sees...12

From Chahzamane's window, we move here to a more elaborate device of technical accommodation of the gaze, which clearly establishes the difference of a private chamber ("the most secret and beautiful of the queen's chambers", la piú secreta stanza e la piú bella) and the public gallery from which the melancholy Mona Lisa has gradually wandered ("It is there that he retires alone, all pleasure, all society being odious to him", perché ogni diletto | perch'ogni compagnia prova nimica).

La Fontaine further accentuates the partition device. First, it is through a watertight partition that Mona Lisa hears the Queen's speech to the dwarf without seeing:

For one day being alone in a gallery

A solitary place, and kept very secret,

He heard in a certain cabinet,

Whose partition was only of joinery (v. 151-4, p. 562)

It's only later that sight is added to hearing:

The Roman [= Mona Lisa], without much trouble,

Saw them as he brought his eyes

closer.

From the cracks the wood left in various places. (v. 178-180, p. 563)

The third sequence, finally, is the one in which mediation is most complex: the direct entry into the room, then what is caught through a partition, is succeeded by Fiammette's stratagem, who sleeps with her Greek while Mona Lisa and Astolphe, lying on either side of the bed, each imagine the other is at work.

When there is no mediation (first sequence), the room delivers no words; no narrative is possible: Joconde, like Chahzamane, withers, becomes ugly; he de-figures; the process of figuration constitutive of the narrative is reached, annihilated, the narrative and its characters are threatened with death13. When there is mediation (second and third sequences), the narrative opts between the visual solution of the scene (this is the voyeuristic play of the partition, second sequence) and the solution of the cunning narrative (this is Fiammette's ruse, third sequence), which maintains the room in its closed status as a room.

The scene publishes the chamber, while the rouerie maintains the chamber in its status as a space of invisibility:

He lengthens his steps, and always on the one behind

.

He stops and stands, and the other foot looks like he's moving it

.

Like he's afraid of stepping on glass,

and doesn't have a floor to stand on.

And had not a floor to tread on, but eggs.

And he stretches out his hand in front of him in the same way,

He goes groping until he finds the bed14. (St. 63.)

There is no space in the room: the glass, the eggs define it as a partition that we touch, that threatens to break, without depth or optical distance. In La Fontaine, the Greek's blind journey through Ariosto's room is matched by the impossibility of saying what happened:

.and God knows how he placed himself;

And how finally everything happened:

And of this, nor of that,

Didn't suspect a thing,

Nor the Lombard king, nor Mona Lisa. (v. 420-424, p. 569.)

There is no possible representation of the event: for want of a known disposition ("God knows how he placed himself "), no stage, no theatricalization. All that remains is the vacillation of language ("Et de ceci, ni de cela"), reduced to the mere sliding of the signifier, to noise; to the crumpling of what is done: this, that, ssss...

La cloison pornographique

Ariosto and La Fontaine's partition will have a bright future in eighteenth-century pornographic literature. In Le Portier des Chartreux, it's through her that Saturnin gets his education:

as I gently searched with my hand whether I might not find some hole in the partition, I felt one that was covered by a large picture. I pierced it, and emerged. What a sight! Toinette as naked as a hand, stretched out on her bed, and Father Polycarpe, the convent's procurator, who had been at home for some time, naked as Toinette, doing what? What our first parents were doing, when God ordered them to populate the earth15.

The partition accommodates the gaze: it indicates the ban that strikes the room, but at the same time it allows for the possibility of a representation of this ban. When the bedroom kills, the stage, publishing the intimate, eroticizing the horror of primitive brutality (Freud's urszene), makes it possible to say through the eye, without fraud, what can never be looked at up close: the woman's jouissance, as the matrix to which the narrative device refers us.

Notes

.La Fontaine, "Joconde. Nouvelle tirée de l'Arioste", in Œuvres complètes, J.-P. Collinet ed., t. I, Fables, Contes et Nouvelles, , Paris, Gallimard, Pléiade, 1991, p. 568; L'Arioste, Roland furieux, André Rochon ed., t. III, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2000, p. 198.

Lacan, Le Séminaire, Book XI, Les quatre concepts fondamentaux de la psychanalyse, "La schize de l'œil et du regard", Seuil, Points, pp. 84, 95, 110; Merleau-Ponty, Le Visible et l'invisible, "L'entrelacs - le chiasme", Gallimard, Tel, p. 173sq.

Les Mille et une Nuits, Phébus, 1986, I, 35, translation by René R. Khawam based on the mid-thirteenth-century Bnf Arabic manuscript 3609 used by Galland. In the translation by Jamel Eddine Bencheikh and André Miquel: "He returned to his palace to find his wife lying on the royal bed, embraced by a black kitchen slave. This spectacle plunged him into darkness." (Les Mille et Une Nuits, t. I, Gallimard, Pléiade, 2005, p. 6) In Antoine Galland's translation: "But what was his surprise when, in the light of the torches, which are never extinguished at night in the apartments of princes and princesses, he saw a man in his arms! He remained motionless for a few moments, unsure whether to believe what he was seeing." (Les Mille et une nuits, t. I, GF Flammarion, 2004, p. 24-25)

"He put her legs up, slid between her thighs and possessed her. At this signal, each slave joined forces with one of the girls. They never stopped kissing, embracing, holding and taking each other until nightfall." (trans. Bencheikh and Miquel, p. 7-8); "Modesty does not allow us to recount everything that happened between these women and these blacks, and it's a detail we don't need to go into. Suffice it to say that Schahzenan saw enough to judge that his brother was no less to be pitied than he." (trans. Galand, p. 27)

See Philippe Ortel, "Le triangle scénique", in "Valences dans la scène", La Scène. Littérature et arts visuels, M.-Th. Mathet ed, Paris, L'Harmattan, 2001, p. 306.

"When he saw all this, the young king said to himself..." (Bencheikh & Miquel 8); "As all these things had happened before the eyes of the king of Great Tartary, they gave him cause to make an infinite number of reflections." (Galland 27)

"The girl looked up at the foliage and saw the two kings there. She lifted the demon's head, laid it back on the ground and stood up. She beckoned the two men to come down without fear." (Bencheikh & Miquel 10); "The lady then raised her sight by chance, and, catching sight of the princes at the top of the tree, she beckoned them with her hand to come down without making a sound." (Galland 32)

Khawam 37; "the heart burned by a deep pain", "Shâh Zamân remembered his wife's betrayal", "never had greater affliction struck a human being", "I suffer from a deep wound" (Bencheikh & Miquel 7)

References are to Khawam. In the same translation, the second sequence is characterized once as a scene: "All this had taken place before the eyes of Shahzamane, who had not stopped watching the scene from his window." (Khawam 40); similarly in Galland: "he had not wanted to have supper until he had seen the whole scene that had just been played out under his windows" (Galland 28). But the translation here takes liberties with the Arabic text. The word scene was not introduced into Arabic until the 20th century, to reflect a European cultural category that has no equivalent.

"Smonta in casa, va al letto, e la consorte | Quivi ritrova addormentata forte." (Orlando furioso, 1532, XXVIII, 20, p. 188; I translate; Ariosto's text is quoted, here and in the following notes, from Ludovico Ariosto, Orlando furioso, Lanfranco Caretti ed., Turin, Einaudi, 1966, 1992.)

Vv. 95-96, op. cit. p. 561.

"In capo de la sala, ove è piu scuro

(che non vi s'usa le finestre aprire),

vede che 'l palco mal si giunge al muro,

e fa d'aria piú chiara un raggio uscire

pon l'occhio quindi, e vede quel che duro

a creder..." (XXVIII, 33, p. 192)

Translating. Palco has been variously understood: either the ceiling (A. Rochon), but how would Mona Lisa put her eye there, or rather the wooden partition wall (F. Reynard), which here joins at right angles the stone wall outside the house. Palco also refers to scaffolding, a theater stage.

In The Thousand and One Nights, speech is constantly identified with life. The one who tells lives, while the one whose speech is prevented, or blocked, dies. This is true not only of the frame story, where Scheherazade tells to avoid being beheaded, but also of the various tales. For example, in the Story of the Three Calenders, the guests of the three mysterious ladies of Baghdad avoid beheading only on condition that they each tell their own story. In European storytelling aesthetics, this symbolic equivalence is perpetuated, in attenuated form, around the figure/defiguration polarity, which itself comes into contact with other imaginary logics or configurations.

" Fa lunghi i passi, e sempre in quel di dietro

tutto si ferma, e l'altro par che muova

a guisa che di dar tema nel vetro,

non che 'l terreno abbia a calcar, ma l'uova ;

e tien la mano inanzi simil metro

va brancolando in fin che 'l letto trova" (XXVIII, 63, p. 199, I translate). ') Ref biblio: See note 11. Nothing to add here

Jean-Charles Gervaise de Latouche, Histoire de Dom B***, portier des Chartreux, 1740, in Romanciers libertins du XVIIIe siècle, P. Wald Lasowski éd., coll. J. P. Dubost, Gallimard, Pléiade, I, p. 337.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Scène pour voir et chambre des brutalités : la cloison de l'intime, des Mille et Une Nuits à Joconde », Topique(s) du public et du privé dans la littérature romanesque d'Ancien Régime, dir. Marta Teixeira Anacleto, Peeters, Louvain-Paris-Walpole, MA, 2014, p. 135-148.

Fiction, illustration, peinture

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Fiction, illustration, peinture

La scène de roman

La scène de roman : introduction

Renaud dans le jardin d’Armide

Rastignac chez Mme de Restaud

Gilberte derrière les aubépines

La poignée de porte de tante Berthe

La double aporie du topos

Illustrer la fiction

Molière, une parole débordée

Marillier, l’appel du mièvre

On n'y voit rien

Illustrations de l'utopie au XVIIIe siècle

Le temps des images

Du conte au roman graphique

Déconstruire l’illustration

Régimes de la représentation dans la gravure d’illustration classique

Penser la fiction depuis la peinture

Une sémiologie du décalage : Loth à la scène

Introduction à la scène comme dispositif : Paolo et Francesca

La main tendue, le regard démasqué

De Silène molesté à la chair blanche des nymphes

Chambres de la représentation

L'intimité de Gertrude

Brutalités invisibles

Parodie et pastiche de Poe et de Conan Doyle dans Le Mystère de la chambre jaune de Gaston Leroux

Le dispositif de la chambre double dans Les Démons de Dostoïevski

Scène pour voir et chambre des brutalités

La Princesse de Clèves

L’invention de la scène dans le roman français

La canne des Indes

L'aveu

La princesse, la religieuse et l'idiot

Richardson

Entre scandale et leurre

Introduction aux Lettres angloises, ou histoire de miss Clarisse Harlove, par Samuel Richardson